States of Matter S1

1/98

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

99 Terms

perfect gas

V = 0

no interaction between gas particles

hence kinetic theory of gases

perfect solid

K = 0

behave as if T = 0K

hence all energy is stored as potential energy in bonds between atoms, which behave as springs.

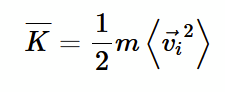

average kinetic energy for a group of atoms

average velocity of an atom

0

ideal gas conditions

particle size << particle separation

interparticle forces are negligible

energy is exchanged ONLY through elastic collisions

distribution of speed/energy is constant in time (i.e. in equilibrium)

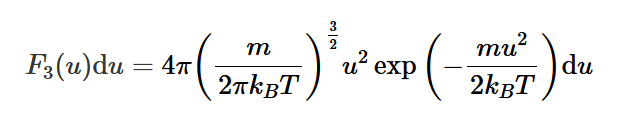

Maxwell-Boltzman speed distribution

3 - 3 dimensional

u - speed of gas atom

m - mean mass of 1 atom

du - inifinitesimal spread of speeds

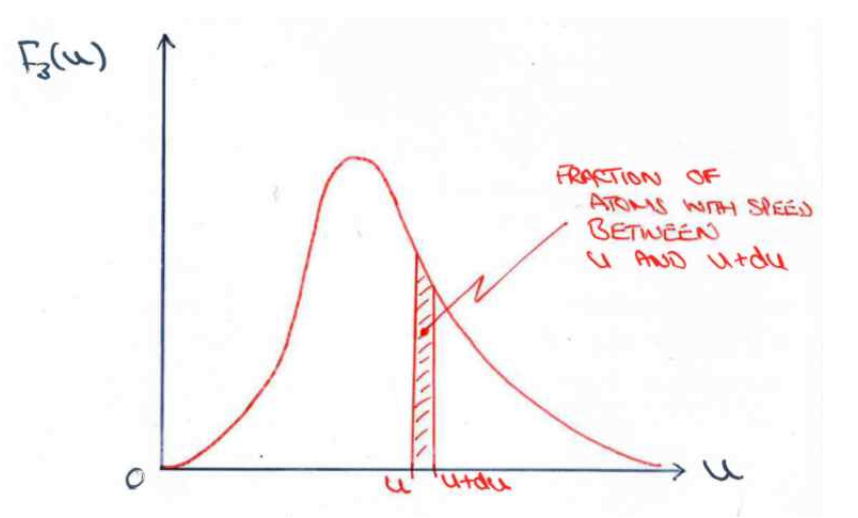

explanation: integral between u and u + du is the probability of a random atom having a speed in that range. assumes F3(u) is constant over this range

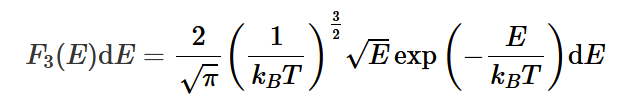

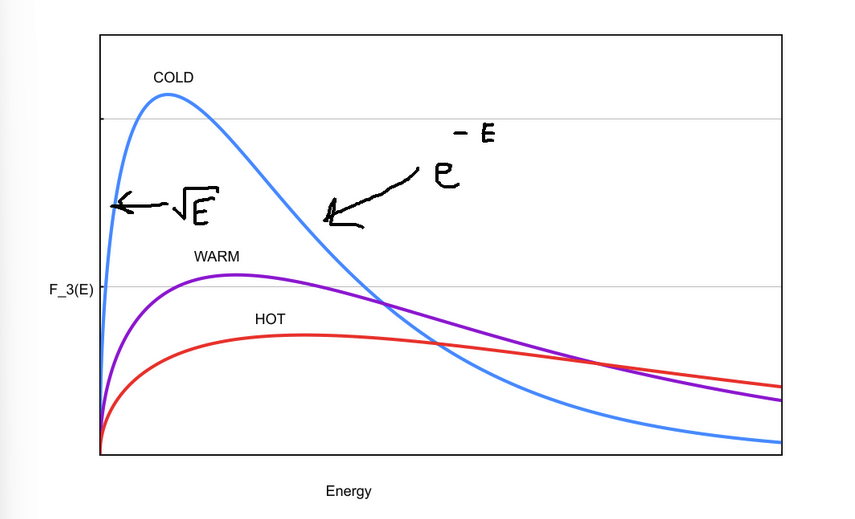

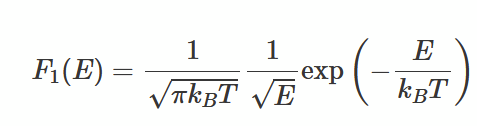

Maxwell-Boltzmann Energy distribution

integral between E and E + dE ( = F3(E)dE ) is the probability of a gas atom having kinetic energy lying in that range. This is temperature dependent, with higher temperatures leading to shallower “hills”.

Value for the infinite integrals of F3(E)dE and F3(u)du.

1

Normalisation of the distributions

adding constants so that integrals, and therefore total probability each, = 1.

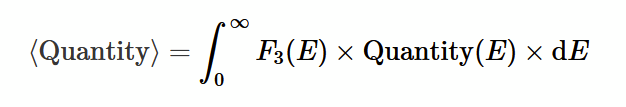

mean value of a some quantity as a function of energy: Q(E)

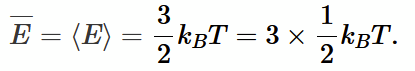

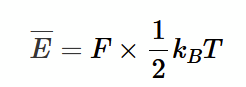

mean kinetic energy (from normalised distribution method) <E>

(shows that temperature is related to mean KE)

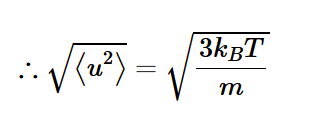

mean speed / root-mean-square speed from mean kinetic energy <E> = 0.5m<u²>

1/6 model of a gas

at some instant in time, 1/6 of the total number of atoms (N) in volume (V) are moving in one of the 6 coordinate directions (±x, ±y, ±z)

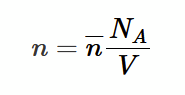

gas atoms per unit volume

n = N/V

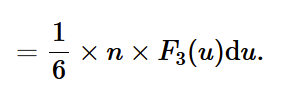

number of atoms moving in one of the 6 directions with speed between u and u+du

pressure of an ideal gas

pressure is force per unit area, force is rate of change of momentum. So, pressure can be worked out if we know how many atoms bounce against surface per unit time per unit area.

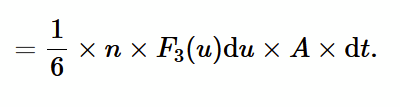

number of atoms striking pistons/cylinder surface with speed between u - u+du in time dt

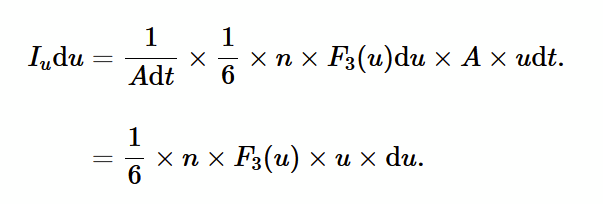

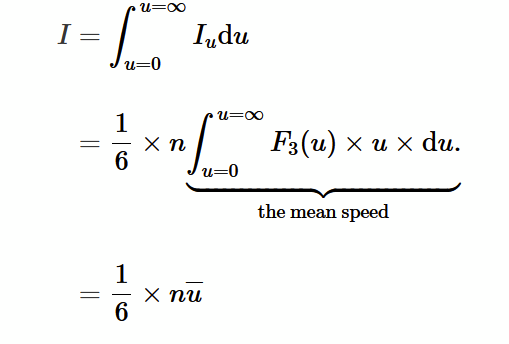

collision frequency - number of atoms striking per unit area per unit time.

total number of atoms striking per unit area per unit time over all values of u and u+du

to find this, we need to add up all the atoms from all the possible strips between u and u+du i.e. we integrate.

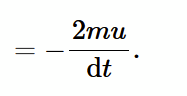

force exerted by piston on single atom (from rate dp/dt)

force exerted by atom on piston

equal and opposite to force exerted by piston atom

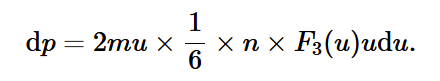

pressure infinitesimal for one speed

multiply force exerted by one atom by number of atoms at speed u striking the piston, then divide by area and cancel dt factor.

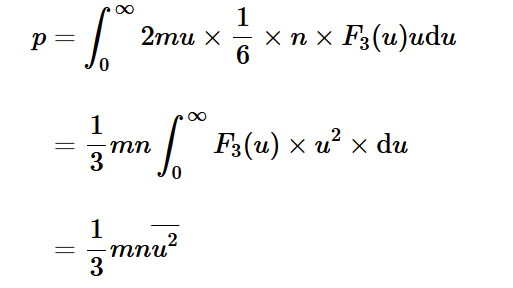

total pressure (1)

integrate over all atomic speeds

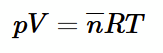

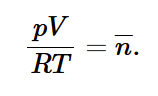

how to derive boyle’s ideal gas equation

n can be rearranged to e in terms of number of moles (n bar), volume (V) and avogadros constant (NA). Substitute this into the pressure equation and rearrange. equate the two expressions for mean kinetic energy and rearrange again.

Avogadro’s law

equal volumes of gases measured at the same temperature and pressure contain the same number of atoms/molecules.

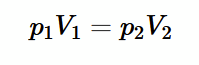

Boyle’s Law

If T1 = T2 and given Avogadro’s Law number of moles is constant, then product of pressure and volume is also constant.

Charles’ Law

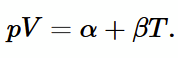

from empirical evidence (photo), then for an ideal gas pV = nmolesRT

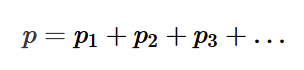

Dalton’s Law on partial pressures

for a gas mixture, the total pressure if the sum of the individual constituent pressures (consider gases as ideal gases, so they cannot interact with each other)

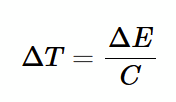

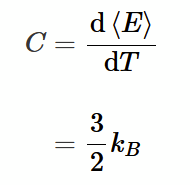

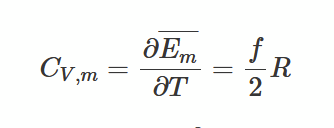

heat capacity

relates change in temperature to change in energy. C = d<E>/dT

heat capacity of an ideal gas

modes/degrees of freedom (F) of a gas molecule

translational kinetic energy (1 per dimension)

rotational kinetic energy

potential energy (stored in bonds which can be modeled using Hooke’s law)

vibrational kinetic energy (stored in bonds as kinetic energy)

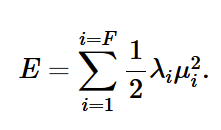

energy for F degrees of freedom (1)

the sum of mean energies for each degree of freedom (E = 0.5𝜆𝜇²)

Mean energy of a single degree of freedom using M-B distribution

equipartition of energy theorem

find dE in terms of 𝜆, 𝜇 and d𝜇, then substitute into mean energy equation for 1D

monatomic gas

F = 3 (3 translational, rotations blocked)

rigid diatomic gas

F = 5 (3 translation, 2 rotational, no vibration/lower inertia axis blocked)

diatomic gas

F = 7 (3 translational, 2 rotational, 2 vibrational bc bond has kinetic and potential energy as 1D oscillator)

Experimental data for diatomic gas

the number of degrees of freedom determines how much energy is needed to change a gas’ temperature. At low temps, only translation modes are excited. Heat up to excite the two rotations. Heat up even more to excite vibrational. You could go further to excite blocked rotation but you risk dissociating the molecule.

polyatomic gas

assume rigid. F = 6 (3 translational, 3 rotational)

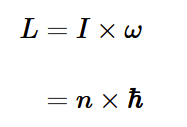

Moment of inertia (I)

how “difficult” it is to set a body spinning about a given axis. For a point mass I = Mr²

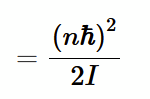

Bohr quantisation of angular momentum (L)

h bar = h/2π

n is an integer

Rotational kinetic energy

e.g. quantum of rotational energy E1 when n = 1

high inertia axis

using bond length r0 as an approximation for distance from axis, calculate the moment of inertia, and therefore E1 for the molecule. substitue into E = 0.5kBT to find the temperature required to excite this mode. For the low inertia axis, this if often way above room temp. So, it remains blockes and cannot contribute to heat capacity.

accounting for Kinetic Theory assumptions for a non-ideal gas

correct volume V as volume occupied by molecules isn’t negligible

attractive forces between molecules e.g. van der Waals exists, and depends on mean separation. correction dependent on V

hard sphere repulsion

treat atoms like solid balls with a definite volume va. let V → V - b,

where b = N x va. so, p(V - b) = nRT.

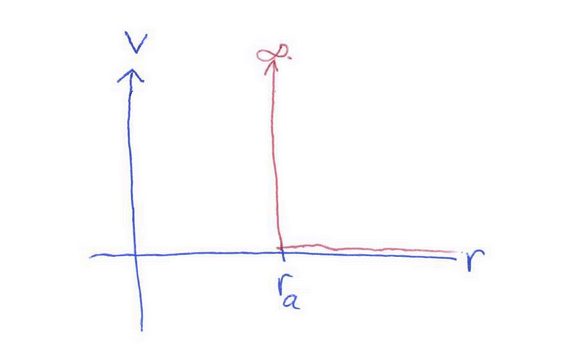

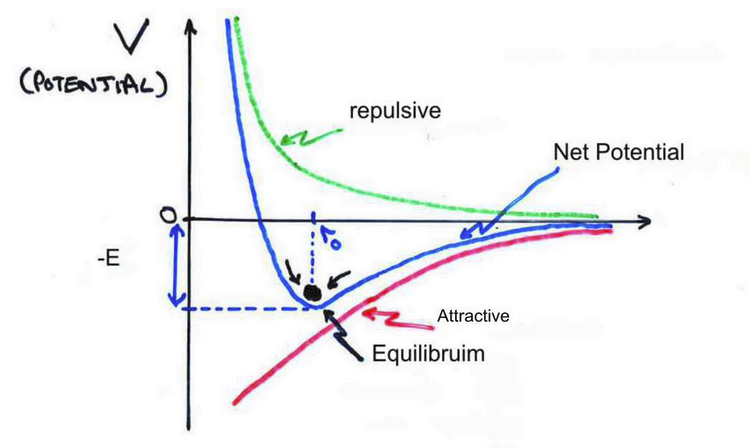

V in photo is potential energy

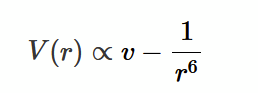

van der Waals interaction

V(r) ∝ -1/r6

a short range effect, effective only out to some radius D

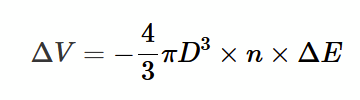

change in potential energy associated with central target gas

product of the volume of shell, the number density, and potential energy per ‘bond‘

pressure correction derivation

modify mean kinetic energy of an atom to account for potential energy term: 1/2 mu² →1/2 mu² − 4/3 πD3 × n × ΔE

substitute into expression for pressure p = 2/3 n (1/2 mu²)

express that n = NA / Vm where Vm is the volume occupied by 1 mole. substitute again. simplify and collect terms as you go.

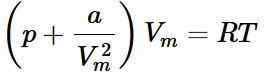

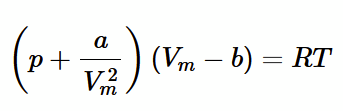

van der waals equation

combine the corrections for volume and the attractive potential, and simplify all the constant terms down to a and b.

at Large Vm : b and a corrections are neglible as volume and number density are both very low

at large T: a is negligible as thermal energy can easily rip apart van der Waals bonds

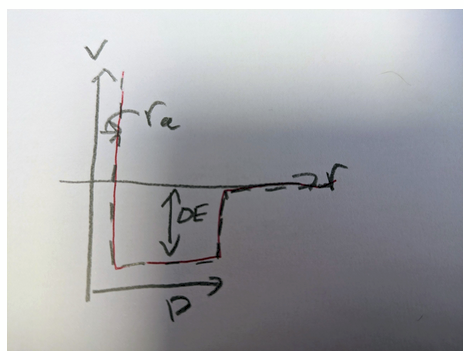

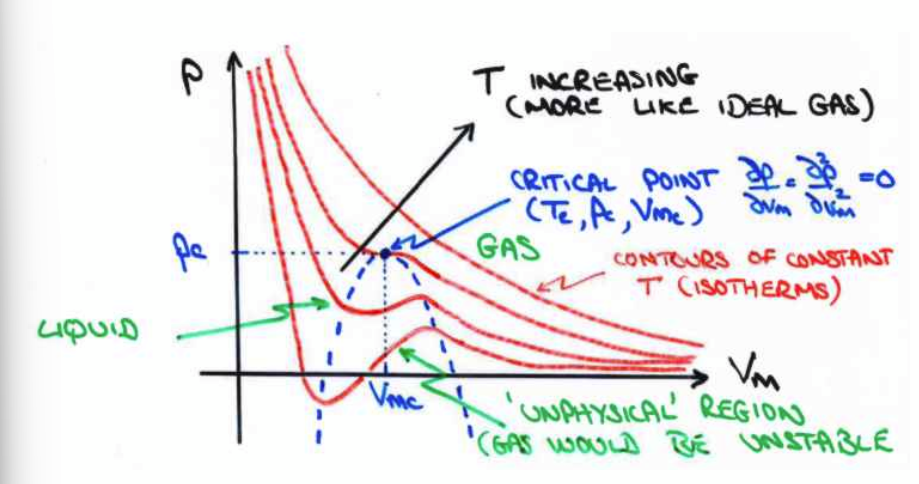

Phase diagrams

van der Waals equation can be plotted as a function of Vm at different isotherms. As temperature increases, behaviour resembles ideal gases.

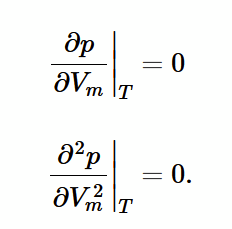

critical point on phase diagram

point of 0 gradient and 0 curvature.

critical temperature (Tc)

highest temperature at which liquid can be formed. can be derived from van der Waals equation at point (Vm,c , Pc)

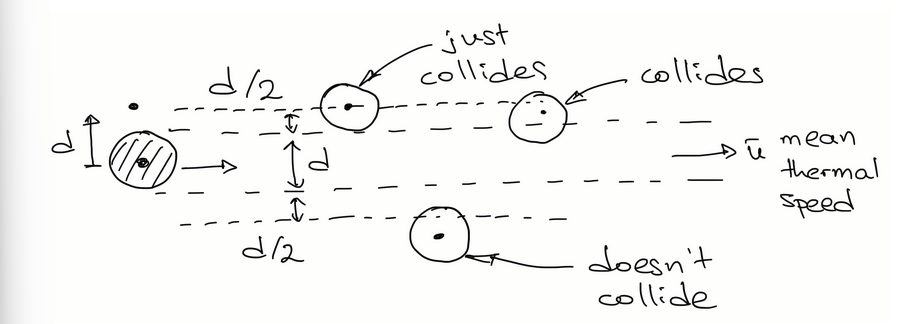

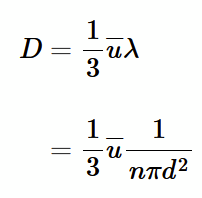

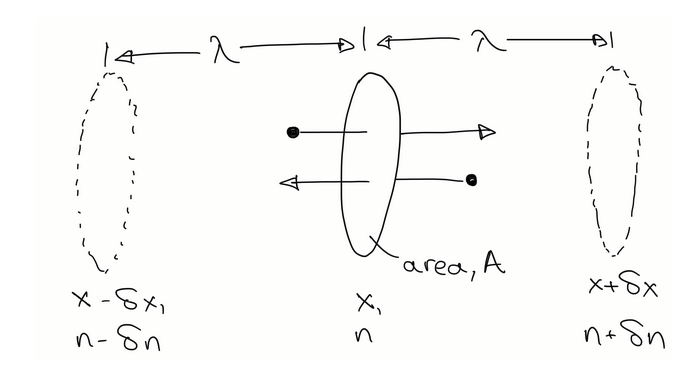

mean free path (λ)

λ = 1/nπd²

mean free path is the average distance travelled by gas atom between two collisions

mean free path derivation

In a 2D scenario, there are several stationary atoms, and 1 atom moving at mean thermal speed (u). This atom collides only with others that lie within a tube with its same diameter. In time t, the atom travels a distance/length of tube ut. λ = distance travelled in t / number of collisions in t. Number of collisions can be approximated by multiplying volume of the tube by the atom density n. substituting all this into the ratio leads to several terms cancelling out and to our final expression for λ.

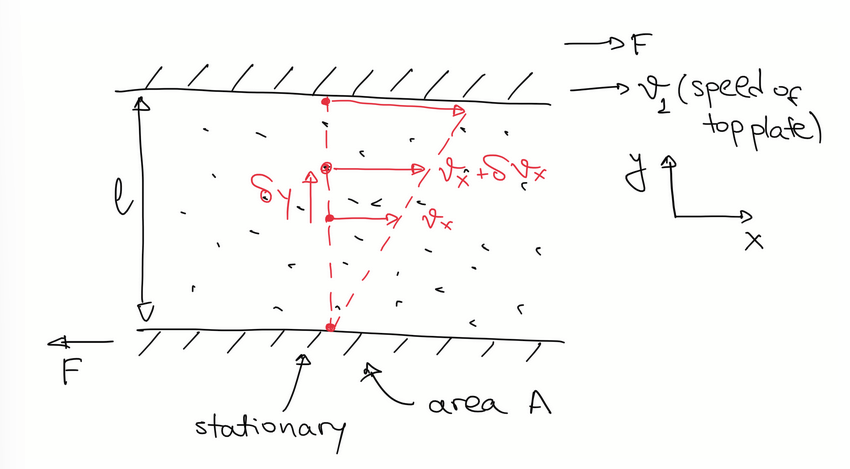

viscous flow in gases

retarding force F is related to dynamic viscosity of the gas η:

F / A = η dvx/dy

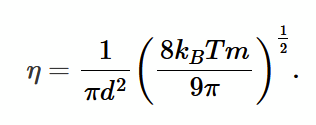

expression for η using mean free path model:

any atom that strikes the top (moving) plate will have been scattered, on average, a distance λ before arriving.

an atom sticks to a plate, so its velocty changes by Δv=v1−v′1, so change in momentum is: Δp = m(v1−v′1).

using 1/6 model we can see number of atoms colliding w plate in time Δt: N = 1/6 A Δt n u

so, total change in momentum is: Δptot = 1/6 A Δt n u m(v1−v′1).

since force is rate of change of momentum, F/A = Δptot / AΔt.

mean flow velocity next to the plate is 0.5(v1+v′1) and because velocity is v’ at distance λ away: ∂vx/∂y= (v−vλ) / λ = (v1−v′1) / 2λ

substitue into the F/A expression to get 1/3 n u m λ ∂vx/∂y.

compare coefficients with F / A = η dvx/dy to find η = 1/3 n u m λ.

use ideal gas expressions for u and λ to get final expression for η

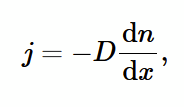

Fick’s law for diffusion in gases

j: particle flux (atoms per unit time per unit area)

D: diffusion coefficient

dn/dx: concentration gradient (negative because particles diffuse from high to low)

expression for D by studying j

particles going left-to-right through A in time t: 1/6 × (n−∂n) × utA

similarly right-to-left = 1/6 × (n−∂n) × utA

flux j is the difference between them divided by time and area:, which simplifies to: j = −1/3 uλ ∂n/λ

assume ∂x∼λ, and compare coefficents with expression j = -D dn/dx to get:

D = 1/3 u 1/nπd²

heat capacity for gases

for a gas that has f degrees of freedom, we use equipartition theorem to find its heat capacity (specifically by finding mean kinetic energy per degree of freedom). We calculate it at constant volume for 1 mole (Em = f/2 RT)

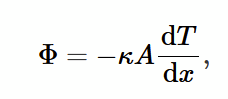

Fourier’s Law of heat conduction

κ: thermal conductivity

Φ: rate of heat flow

negative sign to show heat flow from hot to cold temp.

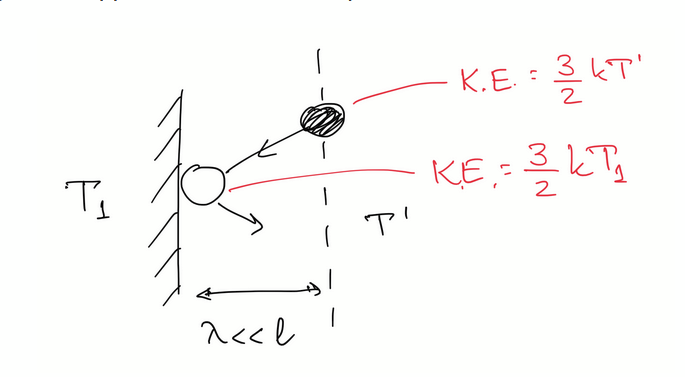

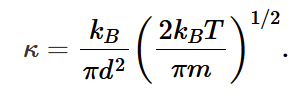

finding κ with atomistic approach

average energy transferred to each atom striking the plate: E = 3/2 kB(T1−T′)

using 1/6 model for number of atoms colliding on plate in time Δt to find energy transferred to gas per unit time: Φ = −1/6 n u A 3/2 kB(T1−T′)

find temperature gradient by approxiating temperature of gas atoms right next to the hotplate as the average of the T’ and T1 : δT/δx = (T’ - T1) / 2λ

rearrange and substitute into earlier expression: Φ = −1/2 n u λ kB A dT/dx.

compare coefficients with fourier’s law to to find that: κ = ½ n u λ kB.

alternate expression for thermal conductivity

expressed using mean free path and mean thermal speed. This expression if temperature dependent and is only valid for l >> λ

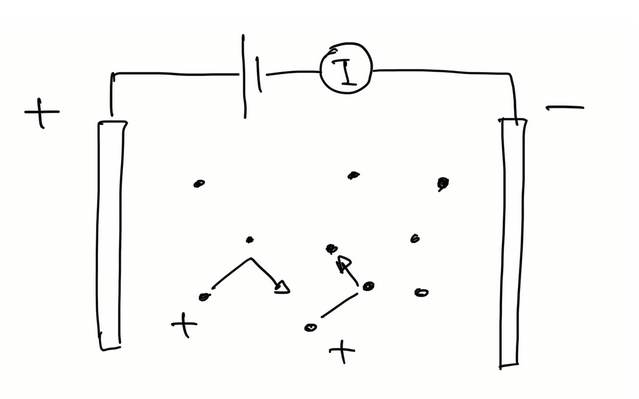

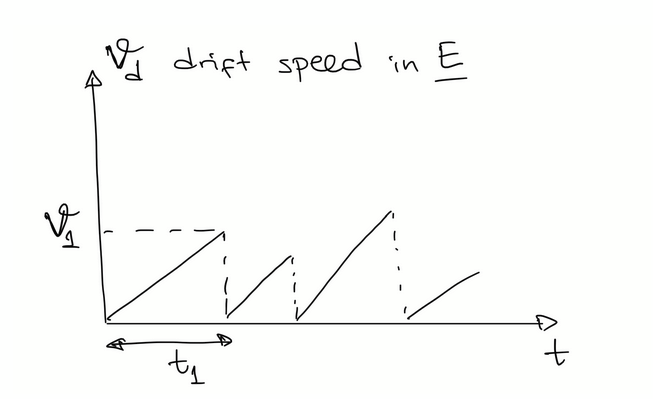

behaviour of charged particles in e field

in an electric field E, charged particle (q) experiences a force F = qE = ma

therefore a = qE / m and charged particles move in parabola

speed in e field after time t1

There is net movement in the direction of the E field, but atoms are constantly accelerating then colliding with each other. (This leads to drift speed)

v1 = a x t1 = q/m |E| t1

corresponding to a distance (from suvat):

x1 = 1/2 a t²1 =1/2 qE/m t²1.

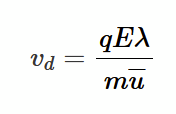

drift speed in an electric field

drift speed = net speed = (mean distance travelled between collisions (xd) / mean free time (τ))

vd = =⟨1/2 qE/m t²⟩ / τ

τ = λ / u and <t²> = 2τ²

so vd = qEλ / mu

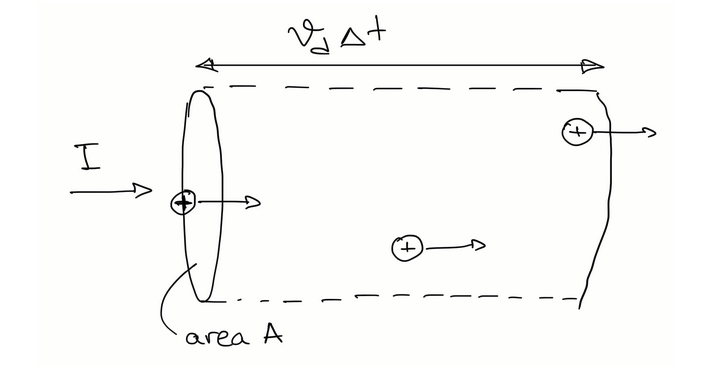

Electric current flow through A in time Δt

assume number of ions per unit volume (n+) << number of atoms per unit volume (n).

total charge in volume Δq = q n+ A vd Δt

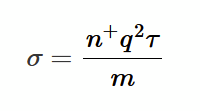

current density per unit area J = I / A = 1/A Δq/Δt

substitute expression from drift speed vd so that J = E (n+ q² τ) / m

given that J = σE, compare coefficients to find σ

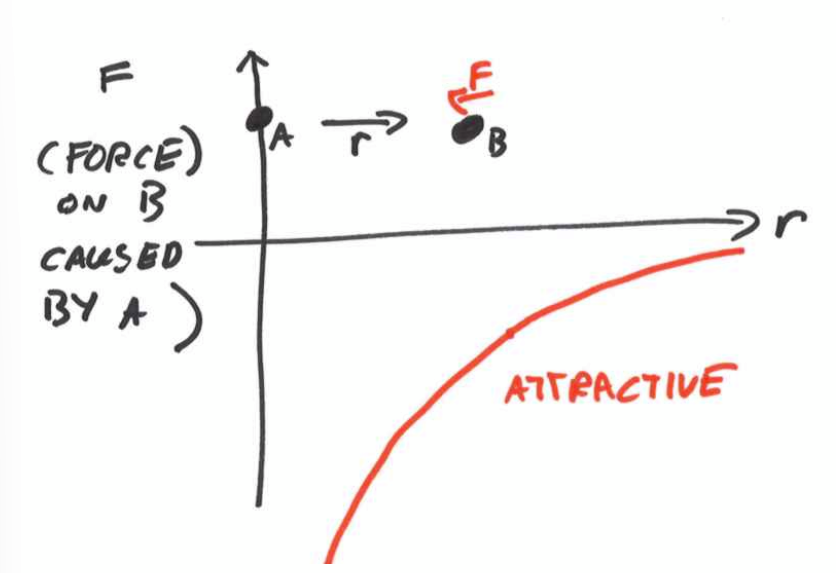

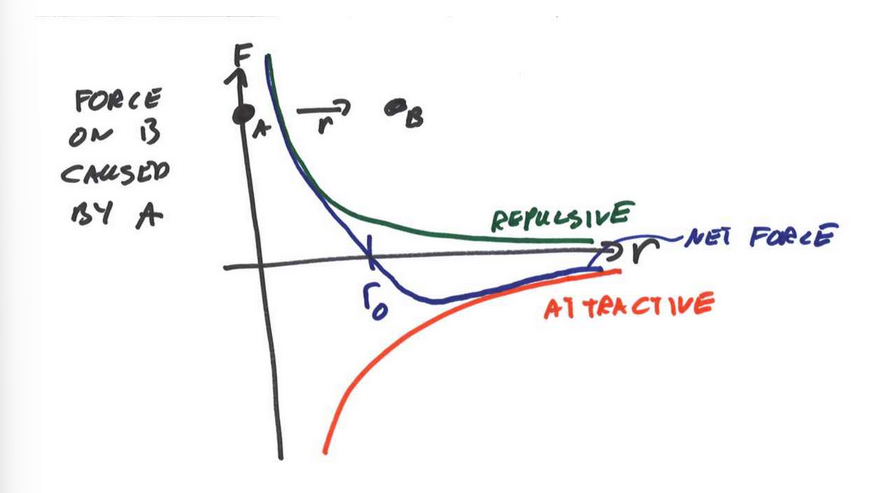

Interactions within a stable molecule

there must be some constant separation and therefore a repulsive and attractive component of the interaction

relationship between force and potential energy

negative sign shows direction of integration/differentiation along some direction r - e.g. rolling down a hill, the direction of potential in the direction of motion is negative.

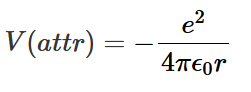

attractive forces

electrostatic (coulomb) force can be attractive at certain distances, and its precise form depends on chemistry of atoms involved.

ionic bond: F = runit x q1q1 / 4πϵ0r2 e.g. table salt

covalent bond e.g. Hydrogen molecules

metallic bond e.g. gold

van der Waals bond

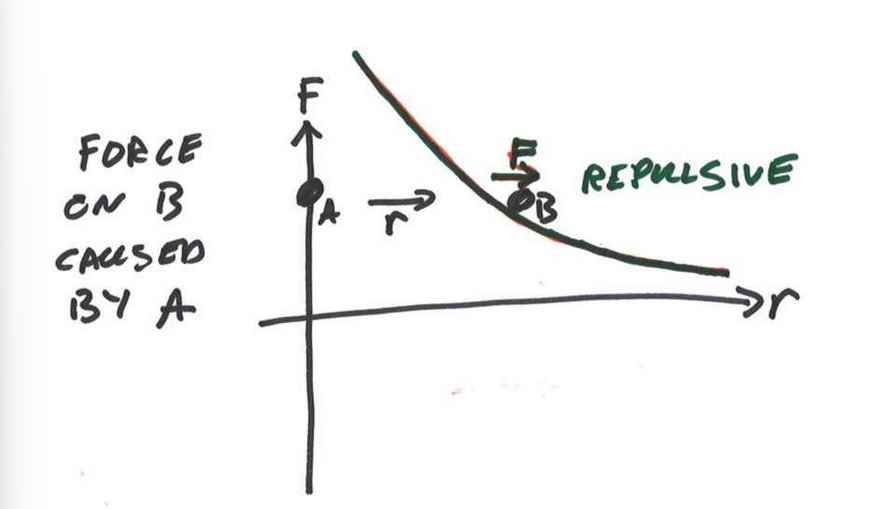

Repulsive forces

short range forces between two atoms due to overlapping electron ‘shells‘. Pauli exclusion forbids any two electrons occupying the same quantum space at the same point in space.

total force between two atoms

consider the sum/superposition of attractive and repulsive forces bc we are dealing with vector quantities.

F = 0 at long distances

at distance r0 there is no net force. this is the Equilibrium Atomic Spacing

Total potential energy between two atoms

stable minimum at r0 where dV/dr = 0 (F(r0) = 0). tends to 0 as r increases

pair dissociation energy

ϵ = V(r = ∞) − V(r = r0)

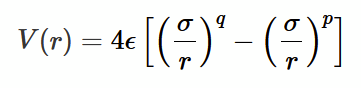

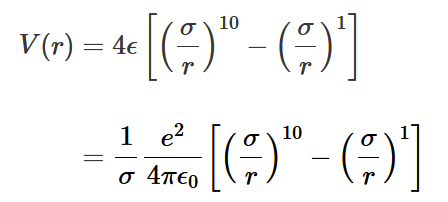

Lennard-Jones p-q potential

an inverse power law to mathematically describe different interatomic potentials. expressed as the sum of a repulsive and attractive terms.

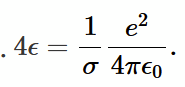

σ

by finding L-J potential at r0, you can find σ is a distance which can expressed in terms of r0 , the coefficient depending on p and q

why use 6-12 potential

pair dissociation energy = ϵ exactly.

for other potentials there may some other coefficient due to the values of p and q.

Pair Dissociation Energy (LJ)

-V(r0)

attractive potential using L-J

Ionic bond using L-J potentials

for repulsive term, assume q = 10, so we use 1-10 potential to desribe an ionic bond. Also use the L-J expression for attractive potential.

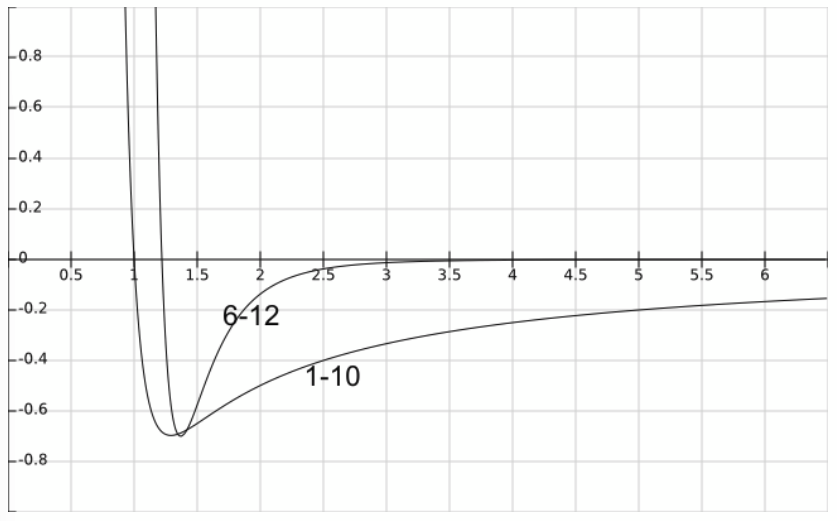

6-12 vs 1-10 potentials

The 6-10 describe a weak and highly localised interaction between two neutral components. The 1-10 describes the strong and long range Coulomb force.

van der Waals explanation

everything sticks to everything, including inert gas atoms like He. On average, electrons surrounding an atom are evenly distributed, but if you observe them at some instant they might be asymmetric (as they constantly fluctuate). This creates a dipole in the atom. Another atom at some distance r will feel this dipole E field and become polarised as well (in sympathy with the first atom). This leads to an attractive potential between the two dipoles described by the van der Waals power law.

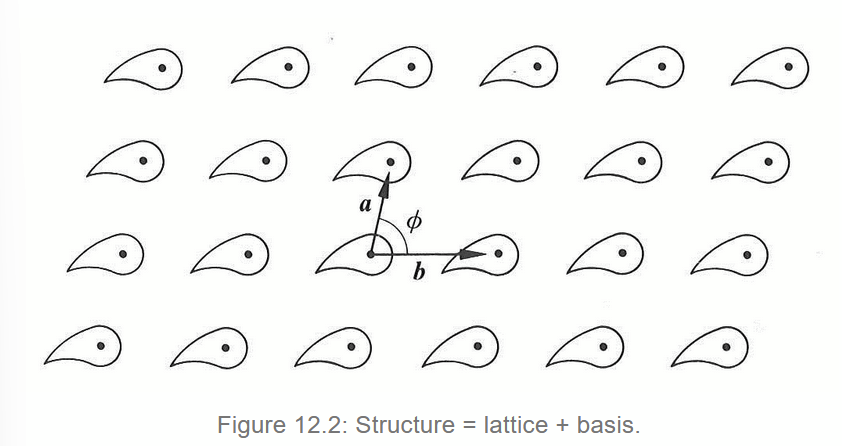

description of ideal solid

The arrangement of atoms on a periodic lattice with translational symmetry.

PE =/ 0

KE = 0 (i.e. T = 0)

translational symmetry

Space symmetry operators do not return to their original orientation and translations can go on almost forever. imagine a lattice - a set of infinite number of points in space (3D, plane in 2D) related by translation. These patterns describe translational symmetry.

periodic arrays of atoms

if we know how atoms are arranged in 1 ‘unit cell‘ o a solid, we can translate this cell to generate all the other atoms.

Lattice and Basis

A 2D lattice:

array of lattice points, who each have a basis group of atoms (represented by the fish shape)

lattice does not exist, but tells us where to put the basis

lattice can be desrcibed by the lattice vectors a and b; any point R can be expressed by the sum of integer multiples of a and b

primitive cell

lattice is normally specified by a primitive cell containing only 1 lattice point. This is is the smallest cell which can be repeated and reproduce the lattice

lattice types

by modifying the lengths of a and b, as well as changing the angle (Φ) between them, we can produce infinite lattices which are fundamentally the same

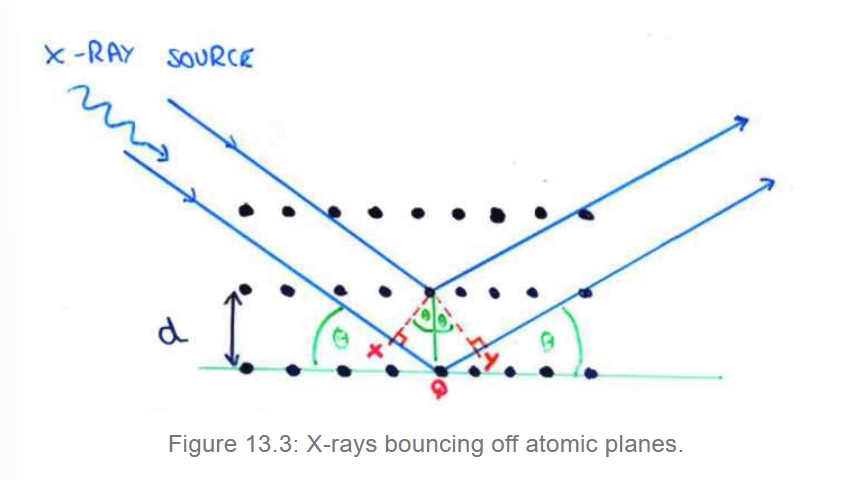

X-ray diffraction

most powerful way of elucidation of the crystal structure. Because solids form ordered crystals, they can coherently diffract x-rays and produced defined ‘spot‘ patterns.

Bragg’s Law

Consider different planes of atoms in a crystal, with x-rays bouncing off different layers. If the path difference is nλ, the twobeams will constructively interfere.

so 2dhkl sinθ = nλ

where dhkl is the perpendicular distance between a set of planes.

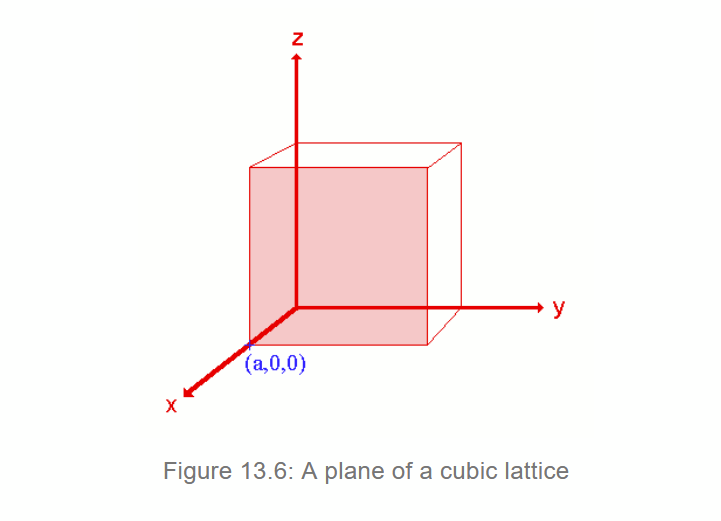

How to find Miller Indices (hkl)

1 - identify x, y and z intercepts (infinity if a plane is parallel to the axis) e.g. (a, ∞, ∞) is a plane of a cubic lattice intersecting x axis at x=a and never intersects the y and z axes

2 - find fractal intercepts by dividing the intercepts by respective cell dimension e.g. unit cell with dimension a x b x c and intercepts (x,y,z) has fractal intercepts (x/a, y/b, z/c). For our cubic lattice, divide everything by a: (1,∞, ∞)

3 - take the reciprocals of fractional intercepts. the reciprocal for ∞ is 0. so the final miller indices for our plane in a cubic cell (a, ∞, ∞) is (100)

distance between planes (cubic lattice)

miller indices (hkl) in cubic lattice of length a:

dhkl = a / sqrt(h² + k² + l²)

condition for constructive interference

λ ≤ 2dhkl

why x-rays?

spacing between atoms is ~0.2nm which corresponds to wavelength of x-rays.

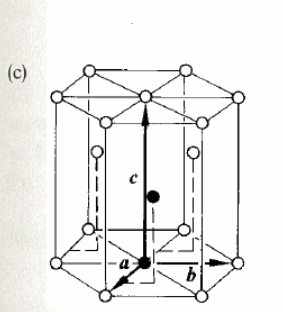

hexagonal close-paced (hcp)

hexagonal prism lattice

basis consists of 1 atom at 000 and one at 2/3 1/3 ½ (fractions of axial lengths a, b and c)

ABAB packing structure

25% of elements e.g. hydrogen, magnesium, zinc

face-centred cubic (fcc)

cubic lattice

basis is two atoms separated by ½ the body diagonal of the cell (when associated with each lattice point we achieve this structure)

ABCABC packing structure

20% of elements e.g. copper, silver, inert gases

body-centred cubic (bcc)

cubic lattice

associate a single atom with ecah point of the lattice

they touch only along a cube diagonal, and so cnnot be made by stacking closest packed plane of atoms

15% of remaining elements e.g. alkali metals, iron, tungsten

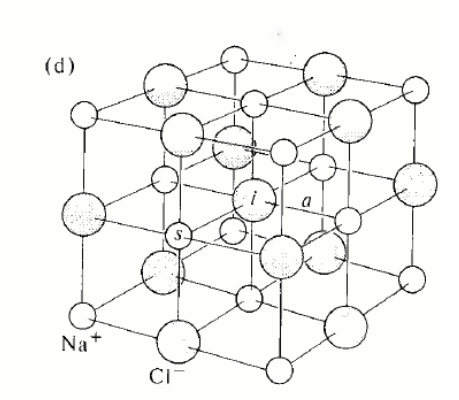

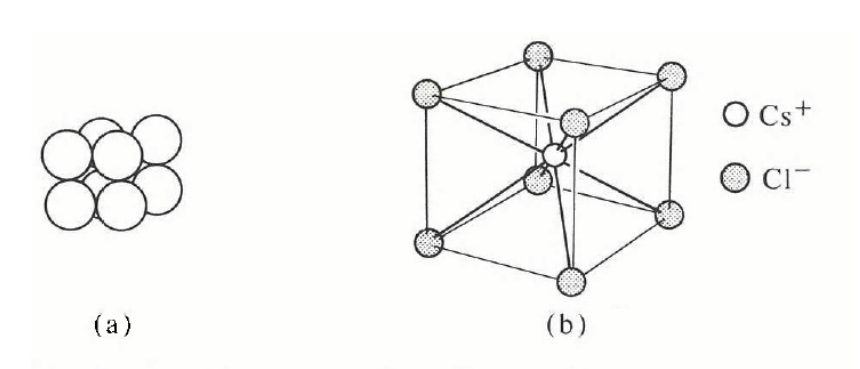

simple cubic structure

simple cubic lattice

associate a single atom at each point of the lattice

stacking planes directly on top each other

only one element (polonium) but very common in compounds e.g. caesium chloride: the basis consists of one Cl− ion at 000 and one Cs+ ion at ½ ½ ½ .

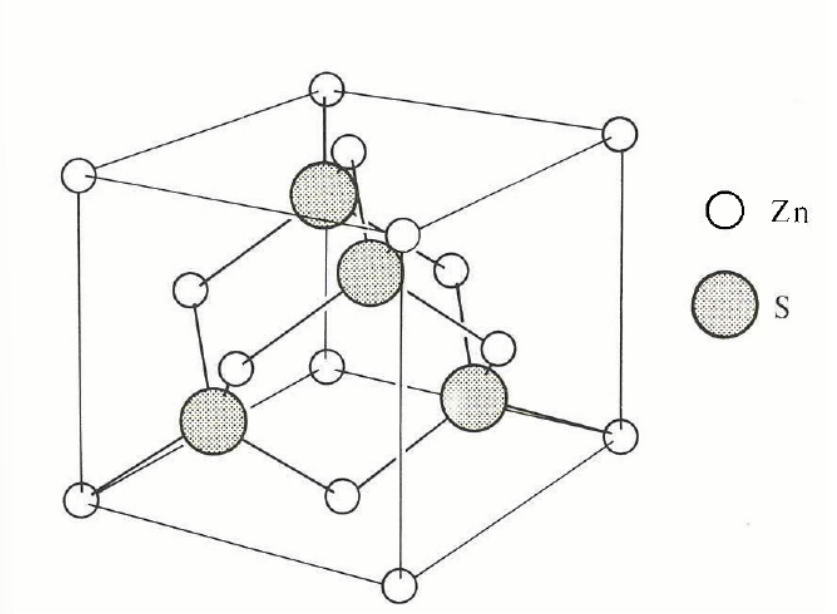

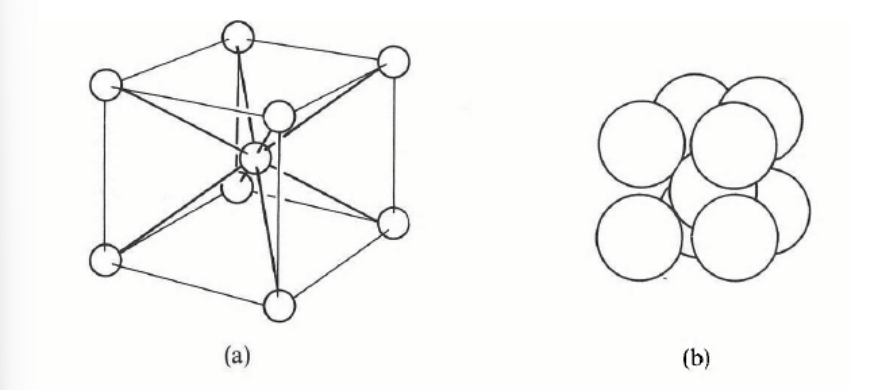

zincblende structure

start with non-primitve cell of fcc lattice

basis associated with ecah lattice point is a Zn atom at 000 and an S atom at ¼ ¼ ¼.

if both atoms are identical, we get diamond structure

e.g. diamond, silicon, gray tin