Regulation of the Cardiovascular System

1/87

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

88 Terms

regulation of the cardiovascular system

Describe the roles of the medullary cardiovascular centers, hypothalamus, and cortex in the autonomic regulation of cardiac and vascular function.

Describe the origin and distribution of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves to the heart and circulation.

Know the location and function of alpha- and beta-adrenoceptors and muscarinic receptors in the heart and blood vessels.

Describe the effects of sympathetic and parasympathetic stimulation on the heart and circulation.

List the anatomical components of the baroreceptor reflex.

Describe how carotid sinus baroreceptors respond to changes in arterial pressure (mean pressure and pulse pressure), and explain how changes in baroreceptor activity affect sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow to the heart and circulation.

Explain the sequence of events mediated by cardiopulmonary (volume) receptors that occur after an acute increase or decrease in arterial blood pressure.

Describe (a) the location of peripheral and central chemoreceptors; (b) the way they respond to hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidosis, and 9c) the effects of their stimulation in autonomic control of the heart and circulation.

List the factors that stimulate the release of catecholamines, renin, atrial natriuretic peptide, and vasopressin.

Describe how the sympathetic nerves, circulating catecholamines, angiotensin II, aldosterone, atrial natriuretic peptide, and vasopressin interact to regulate arterial blood pressure.

Describe the autonomic and hormonal compensatory mechanisms that are activated to restore arterial pressure following hemorrhage.

List the mechanisms and causes of hypotension.

Describe the causes of hypertension and its relationship with the Renin-Angiotensin Aldosterone System.

List the drugs used in the treatment of hypertension and their targets.

Describe the mechanism of neurohumoral activation in heart failure.

Describe the cardiovascular responses to exercise and acute stress (fight-or-flight response and vasovagal syncope).

Define autoregulation of blood flow, reactive hyperemia and active (functional) hyperemia.

Describe the blood flow regulation mechanisms in major vascular beds of the body such as: renal, cerebral, and coronary circulations.

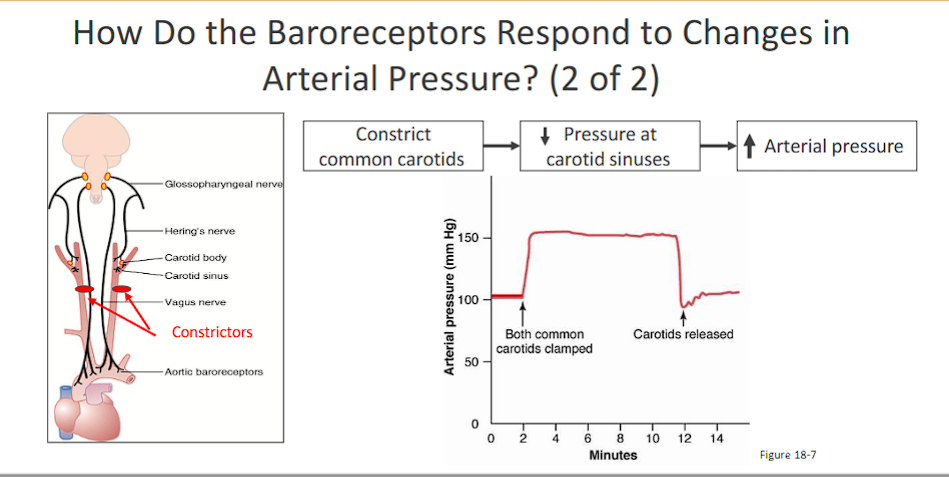

constriction for baroreceptors leads means a decrease in pressure because there is less stretching.

however, VASOconstriction increases pressure.

Constrict Carotids (constriction= less pressure= less stretcing)→ ↓ Pressure in Carotid Sinus → ↓ Baroreceptor Firing → Medulla (NTS/VMC) → ↑ Sympathetic Outflow & ↓ Parasympathetic Outflow → ↑ Heart Rate & ↑ Vasoconstriction → ↑ Arterial Pressure

what is the cardiovascular system?

The cardiovascular system is a closed network composed of the heart, blood, and blood vessels. Its primary function is to deliver essential substances to cells and remove metabolic waste products.

Describe the roles of the medullary cardiovascular centers, hypothalamus, and cortex in the autonomic regulation of cardiac and vascular function. (learning objective)

medullary cardiovascular centers

hypothalamus

cortex

The autonomic regulation of cardiac and vascular function is a hierarchical system, with each level—Medullary Cardiovascular Centers, Hypothalamus, and Cortex—playing a distinct and integrated role.

Here is a description of their roles, from the most reflexive to the most complex.

1. Medullary Cardiovascular Centers: The Central Processing Unit (Both sympathetic and parasympathetic)

“medullary”: located in the medulla oblangata

Located in the medulla oblongata of the brainstem, this is the primary and most fundamental center for cardiovascular control. It integrates sensory input and sends coordinated autonomic output to the heart and blood vessels. The medullary cardiovascular center consists of two main components:

Cardio-inhibitory Center (or Nucleus Ambiguus):

“cardio-inhibitory center”= parasympethetic

Function: Primarily responsible for parasympathetic (vagal) output.

Action: Sends signals via the vagus nerve (CN X) to the heart, specifically the SA and AV nodes.

Effect: Decreases heart rate (negative chronotropy) and reduces the force of contraction (slightly) because it’s parasympathetic. This is the "brake" on the heart, promoting "rest-and-digest" functions.

Cardio-acceleratory Center & Vasomotor Center:

cardio-acceleratory center: sympathetic

Function: Primarily responsible for sympathetic output.

Action:

Cardiac: Sends signals to the spinal cord, which then relays them via sympathetic nerves to the heart, increasing heart rate (positive chronotropy) and contractility (positive inotropy).

Vascular: The Vasomotor Center specifically controls the tone (degree of constriction) of arterioles.

The Vasomotor Center sends a constant low level of sympathetic signal (vasomotor tone). Increasing the sympathetic signal causes vasoconstriction (for faster blood flow); decreasing the sympathetic system causes vasodilation.

Effect: The Cardio-acceleratory Center & Vasomotor Center is the The "accelerator," preparing the body for "fight-or-flight" by increasing cardiac output and blood pressure.

Key Input to the Medullary Centers: The Baroreceptor Reflex

The medulla is the central processor for this critical short-term BP regulation.

Sensors: Baroreceptors in the carotid sinuses and aortic arch detect changes in blood pressure.

Process: A drop in BP reduces baroreceptor firing.

Medullary Response: The cardio-inhibitory center is suppressed (less vagal activity), and the vasomotor center is activated (more sympathetic activity).

Result: Heart rate and contractility increase, and widespread vasoconstriction occurs, rapidly restoring blood pressure.

sympathetic= vasoconstriction to increase blood pressure

parasympathetic= vasodilation to decrease blood pressure

reduction in baroreceptor firing causes activation of sympathetic nervous system= vasoconstriction.

In summary, the Medullary Centers provide minute-to-minute, reflexive control of heart rate, contractility, and vascular tone.

2. Hypothalamus: The Integrative and Command Center

The hypothalamus sits above the brainstem (above the pituitary gland, NOT above the medulla oblongata) and the hypothalamus integrates 1. autonomic, 2. endocrine, and 3. behavioral responses. It does not replace the medullary centers but the hypothalamus commands and modulates them to serve broader physiological and emotional goals.

Autonomic Integration: The hypothalamus has direct neural connections to the medullary cardiovascular centers. the hypothalamus can override local reflexes to coordinate cardiovascular function with:

Temperature Regulation: In response to heat (too hot), the hypothalamus inhibits the vasomotor center, leading to cutaneous vasodilation to dissipate heat. In response to cold (too hot), it stimulates vasoconstriction to conserve heat.

Stress & "Fight-or-Flight" Response: During perceived threat or stress, the hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system via the medullary centers and the spinal cord. This causes a massive increase in heart rate, contractility, and vasoconstriction in non-essential beds (e.g., gut), shunting blood to muscles.

vasoconstriction to NON-ESSENTIAL beds so more blood flows to muscles.

Defense Reaction: Specific hypothalamic areas, when stimulated, can evoke a pattern of cardiovascular changes (like increased BP and heart rate) associated with anger or fear.

Circadian Rhythm: The hypothalamus helps set the daily (circadian) rhythm of blood pressure, which is typically higher during the day and lower at night.

Endocrine Coordination: The hypothalamus regulates the pituitary gland, which in turn controls hormones that affect cardiovascular function (e.g., Vasopressin/ADH, which causes vasoconstriction and water retention).

vasopressin/ADH causes vasoCONSTRICTION and WATER RETENTION.

In summary, the Hypothalamus provides a higher level of control, linking cardiovascular function to temperature, emotion, stress, and overall homeostasis.

3. Cortex: The Executive Decision-Maker

The cerebral cortex, particularly the limbic system (emotion) and prefrontal cortex (planning, decision-making), provides the highest level of influence. It is responsible for psychosomatic and volitional influences on the cardiovascular system.

Emotional Influence (Limbic System):

Feelings of anxiety, excitement, or fear can trigger a cortical response that projects to the hypothalamus, leading to a rapid increase in heart rate and blood pressure (e.g., feeling your heart pound before a public speech).

Conversely, feelings of calm or meditation can activate parasympathetic pathways, lowering heart rate and blood pressure.

Volitional (Conscious) and Anticipatory Control:

The mere anticipation of exercise (the "get-ready" phase) can cause a cortical-mediated increase in heart rate and cardiac output via the hypothalamus and medullary centers.

Conditioned responses (e.g., a phobia of something that causes a cardiovascular reaction) are processed by the cortex and amygdala.

Cognitive Appraisal of Stress: How the cortex interprets a situation determines the magnitude of the cardiovascular response.

In summary, the Cortex links conscious thought, emotion, and learned behavior to cardiovascular function, allowing for anticipatory and psychologically-driven changes in heart rate and blood pressure.

Summary Table: Hierarchical Regulation

Level | Primary Role | Example of Action |

|---|---|---|

Cortex | Executive/Volitional | Heart rate rises due to anxiety before an exam; anticipatory rise before exercise. |

Hypothalamus | Integrative/Command | Redirects blood flow for thermoregulation; coordinates "fight-or-flight" response. |

Medullary Centers | Reflexive/Homeostatic | Baroreceptor reflex instantly increases heart rate when you stand up to prevent fainting. |

This hierarchical system ensures that the cardiovascular system can respond with precise reflexes for immediate survival (medulla), be integrated into broader physiological programs (hypothalamus), and be influenced by our thoughts, emotions, and environment (cortex).

1. Medullary Cardiovascular Centers: The Central Processing Unit (Both sympathetic and parasympathetic)

Cardio-acceleratory Center & Vasomotor Center (sympathetic)

Cardio-inhibitory Center (or Nucleus Ambiguus) (parasympathetic)

1. Medullary Cardiovascular Centers: The Central Processing Unit (Both sympathetic and parasympathetic)

“medullary”: located in the medulla oblangata

Located in the medulla oblongata of the brainstem, this is the primary and most fundamental center for cardiovascular control. It integrates sensory input and sends coordinated autonomic output to the heart and blood vessels. The medullary cardiovascular center consists of two main components:

Cardio-inhibitory Center (or Nucleus Ambiguus):

“cardio-inhibitory center”= parasympethetic

Function: Primarily responsible for parasympathetic (vagal) output.

Action: Sends signals via the vagus nerve (CN X) to the heart, specifically the SA and AV nodes.

Effect: Decreases heart rate (negative chronotropy) and reduces the force of contraction (slightly) because it’s parasympathetic. This is the "brake" on the heart, promoting "rest-and-digest" functions.

Cardio-acceleratory Center & Vasomotor Center:

cardio-acceleratory center: sympathetic

Function: Primarily responsible for sympathetic output.

Action:

Cardiac: Sends signals to the spinal cord, which then relays them via sympathetic nerves to the heart, increasing heart rate (positive chronotropy) and contractility (positive inotropy).

Vascular: The Vasomotor Center specifically controls the tone (degree of constriction) of arterioles.

The Vasomotor Center sends a constant low level of sympathetic signal (vasomotor tone). Increasing the sympathetic signal causes vasoconstriction (for faster blood flow); decreasing the sympathetic system causes vasodilation.

Effect: The Cardio-acceleratory Center & Vasomotor Center is the The "accelerator," preparing the body for "fight-or-flight" by increasing cardiac output and blood pressure.

Key Input to the Medullary Centers: The Baroreceptor Reflex

The medulla is the central processor for this critical short-term BP regulation.

Sensors: Baroreceptors in the carotid sinuses and aortic arch detect changes in blood pressure.

Process: A drop in BP reduces baroreceptor firing.

Medullary Response: The cardio-inhibitory center is suppressed (less vagal activity), and the vasomotor center is activated (more sympathetic activity).

Result: Heart rate and contractility increase, and widespread vasoconstriction occurs, rapidly restoring blood pressure.

sympathetic= vasoconstriction to increase blood pressure

parasympathetic= vasodilation to decrease blood pressure

reduction in baroreceptor firing causes activation of sympathetic nervous system= vasoconstriction.

In summary, the Medullary Centers provide minute-to-minute, reflexive control of heart rate, contractility, and vascular tone.

2. Hypothalamus: The Integrative and Command Center

relationship between hypothalamus and medullary centers

temperature regulation

stress and “fight or flight”

defense reaction

circadian rhythm

circadian rhythm

endocrine coordination

2. Hypothalamus: The Integrative and Command Center

The hypothalamus sits above the brainstem (above the pituitary gland, NOT above the medulla oblongata) and the hypothalamus integrates 1. autonomic, 2. endocrine, and 3. behavioral responses. It does not replace the medullary centers but the hypothalamus commands and modulates them to serve broader physiological and emotional goals.

Autonomic Integration: The hypothalamus has direct neural connections to the medullary cardiovascular centers. the hypothalamus can override local reflexes to coordinate cardiovascular function with:

Temperature Regulation: In response to heat (too hot), the hypothalamus inhibits the vasomotor center, leading to cutaneous vasodilation to dissipate heat. In response to cold (too hot), it stimulates vasoconstriction to conserve heat.

Stress & "Fight-or-Flight" Response: During perceived threat or stress, the hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system via the medullary centers and the spinal cord. This causes a massive increase in heart rate, contractility, and vasoconstriction in non-essential beds (e.g., gut), shunting blood to muscles.

vasoconstriction to NON-ESSENTIAL beds so more blood flows to muscles.

Defense Reaction: Specific hypothalamic areas, when stimulated, can evoke a pattern of cardiovascular changes (like increased BP and heart rate) associated with anger or fear.

Circadian Rhythm: The hypothalamus helps set the daily (circadian) rhythm of blood pressure, which is typically higher during the day and lower at night.

Endocrine Coordination: The hypothalamus regulates the pituitary gland, which in turn controls hormones that affect cardiovascular function (e.g., Vasopressin/ADH, which causes vasoconstriction and water retention).

vasopressin/ADH causes vasoCONSTRICTION and WATER RETENTION.

In summary, the Hypothalamus provides a higher level of control, linking cardiovascular function to temperature, emotion, stress, and overall homeostasis.

3. Cortex: The Executive Decision-Maker

emotional influence (limbic system)

anticipation

3. Cortex: The Executive Decision-Maker

The cerebral cortex, particularly the limbic system (emotion) and prefrontal cortex (planning, decision-making), provides the highest level of influence. It is responsible for psychosomatic and volitional influences on the cardiovascular system.

limbic system: a complex system of nerves and networks in the brain, involving several areas near the edge of the cortex concerned with instinct and mood. It controls the basic emotions (fear, pleasure, anger) and drives (hunger, sex, dominance, care of offspring).

Emotional Influence (Limbic System):

Feelings of anxiety, excitement, or fear can trigger a cortical response that projects to the hypothalamus, leading to a rapid increase in heart rate and blood pressure (e.g., feeling your heart pound before a public speech).

Conversely, feelings of calm or meditation can activate parasympathetic pathways, lowering heart rate and blood pressure.

Volitional (Conscious) and Anticipatory Control:

The mere anticipation of exercise (the "get-ready" phase) can cause a cortical-mediated increase in heart rate and cardiac output via the hypothalamus and medullary centers.

Conditioned responses (e.g., a phobia of something that causes a cardiovascular reaction) are processed by the cortex and amygdala.

Cognitive Appraisal of Stress: How the cortex interprets a situation determines the magnitude of the cardiovascular response.

In summary, the Cortex links conscious thought, emotion, and learned behavior to cardiovascular function, allowing for anticipatory and psychologically-driven changes in heart rate and blood pressure.

functions of the vasomotor center (Medullary Cardiovascular Centers)

vasomotor tone

lateral portion of vmc: sympathetic

medial portion of vmc: parasympathetic

1. Control of Blood Vessels: Vasomotor Tone

maintaining the vasomotor tone is the fundamental job of the VMC. The vasoconstrictor area (lateral part) sends a constant, low-frequency stream of signals through the sympathetic nerves to the smooth muscle in blood vessel walls.

This baseline level of stimulation, known as vasomotor tone, keeps the arteries and arterioles in a state of partial constriction.

Without it, the vessels would fully dilate, and blood pressure would plummet. Adjusting this tone up or down is the primary way the VMC raises or lowers blood pressure.

2. Control of the Heart: A Dual System (Sympathetic & Parasympathetic)

The VMC influences the heart through two opposing pathways:

A. The Sympathetic "Accelerator" (Cardioacceleratory Center)

The lateral portions of the VMC function as the CARDIO-acceleratory center. When activated, it sends signals down the spinal cord to sympathetic nerves, which release norepinephrine onto the heart.

Increases Heart Rate (positive chronotropy)

Increases Contractility (positive inotropy), leading to a stronger pump and higher stroke volume.

Overall Goal: To increase Cardiac Output (CO).

B. The Parasympathetic "Brake" (Cardioinhibitory Center)

The medial portions of the VMC (often overlapping with the nucleus ambiguus) function as the CARDIOinhibitory center. It sends signals directly through the vagus nerves (Parasympathetic Nervous System - PSNS), which release acetylcholine onto the heart's pacemaker.

Decreases Heart Rate (negative chronotropy). Parasympathetic nerves have a minimal direct effect on ventricular contractility.

Overall Goal: To decrease Cardiac Output (CO).

How It All Integrates: The Baroreceptor Reflex Example

The true power of the VMC is how it coordinates these three functions simultaneously:

Scenario: A sudden increase in Blood Pressure (e.g., from a stress response)

Baroreceptors in the carotid sinuses and aorta detect high pressure and

baroreceptors increase their firing to the Sensory Area (NTS) of the medulla.

VMC Processing: The NTS signals the VMC to correct the high pressure.

Coordinated Output:

To Vessels: The Vasoconstrictor Area is inhibited. This reduces sympathetic vasomotor tone, causing vasodilation and a decrease in SVR.

To Heart: The Cardioacceleratory Center (lateral) is inhibited, reducing sympathetic drive to the heart.

To Heart: The Cardioinhibitory Center (medial) is stimulated, increasing parasympathetic (vagal) tone.

Result: The combined effect of a slower heart rate, reduced contractility, and widespread vasodilation brings blood pressure back down to normal.

baroreceptor firing

increase in blood pressure= increase firing

decrease in blood pressure= decrease in firing.

positive and negative chronotropy

chronotropy: heart rate

positive chronotopy: fast heart rate

negative chronotropy: negative heart rate

inotropy

inotropy: contractility

positive inotropy: makes the heart contract more forcefully (sympathetic nervous system and other factors)

negative inotropy: makes the heart contract less forcefully (parasympathetic nervous system, beta blockers and calcium channel blockers)

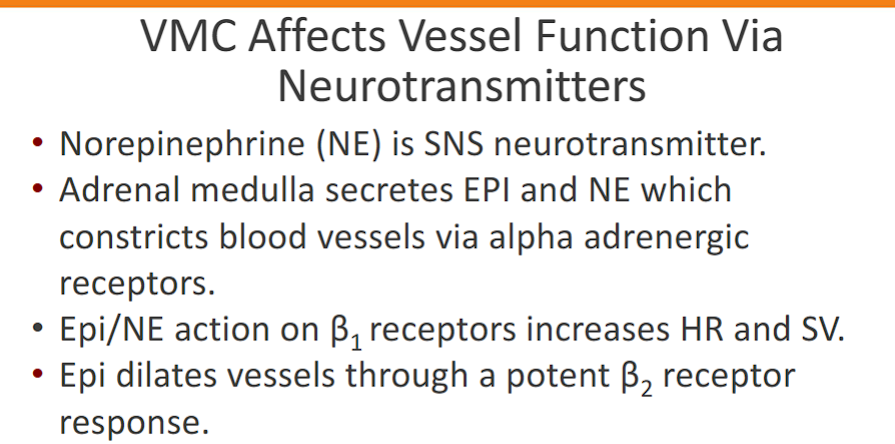

VMC Affects Vessel Function Via Neurotransmitters

which organ secretes EPI and NE?

what is the difference between b1 and b2 receptor?

Adrenal medulla secretes EPI and NE which constricts blood vessels via alpha adrenergic receptors

Epi/NE action on β1 receptors increases HR and SV

Epi dilates vessels through a potent β2 receptor response

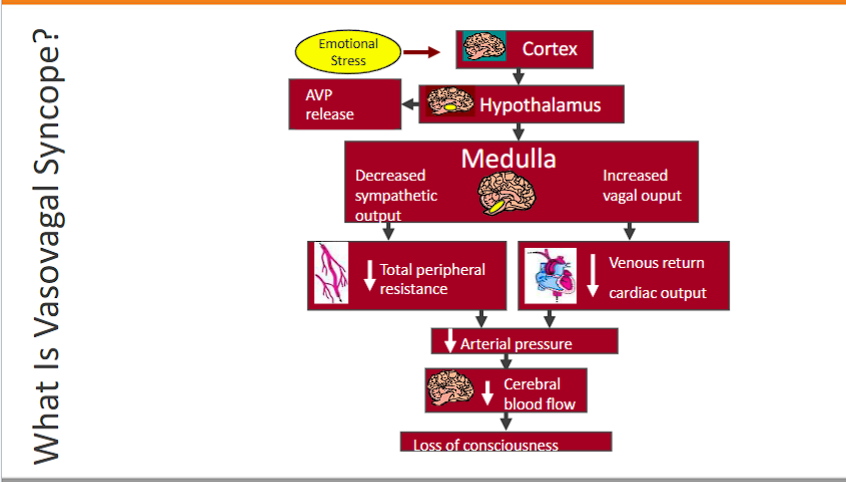

what is vasal syncope?

vasal syncope= faint

syncrope: “cutting off”

Vasovagal syncope is a sudden, reflex-mediated drop in heart rate and blood pressure, the drop in heart rate and blood pressure leads to a temporary reduction in cerebral blood flow and loss of consciousness. It is a neurologically triggered cardiovascular collapse.

1. The Trigger

Emotional Stress: Seeing blood, extreme fear, emotional distress.

Physical Stress: Standing for a long time, severe pain, dehydration, heat exposure.

2. Cortex The cortex interprets a stimulus as a threat and activates the emotional/stress centers that ultimately trigger the maladaptive reflex in the brainstem.

Hypothalamus (Sounds the Alarm & Activates Stress Pathways) AND releases AVP (vasopressin) to increase blood pressure, the release speed of AVP is slower than the drop in blood pressure, which is why the faint occurs.

Medulla: decrease sympathetic output and increases vagal tone, which leads to a decrease in TPR and decrease in venous return cardiac output, leading to a decrease in AP

decrease in arterial pressure leads to decrease in cerebral blood flow

decrease in cerebral blood flow leads to faint.

what is vasopressin?

water conservation (makes kidneys reabsorb water, triggered by high blood osmolarity)

vasoconstriction (raises blood pressure due to low blood volume)

Function | Mechanism | Primary Trigger |

|---|---|---|

Water Conservation (Anti-Diuresis) | Makes kidneys reabsorb water. | High Blood Osmolality ("Salty Blood") |

Vasoconstriction (Raises BP) | Squeezes blood vessels. | Low Blood Volume/Pressure (e.g., Bleeding) |

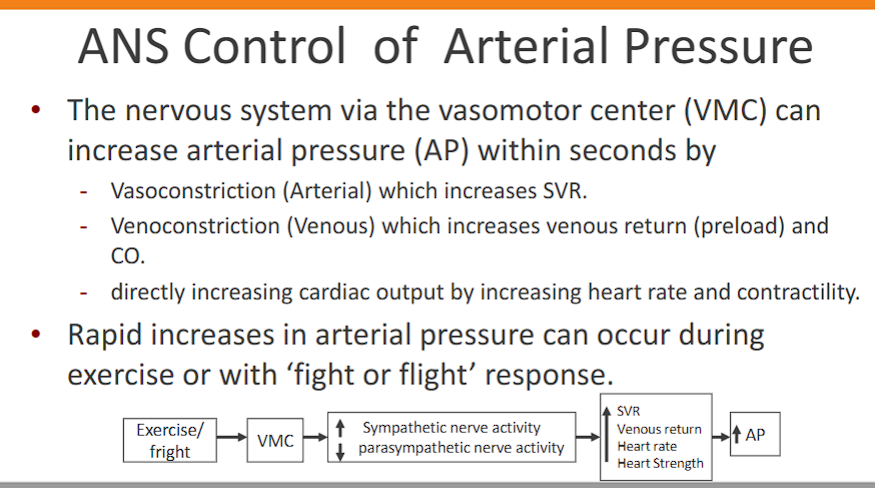

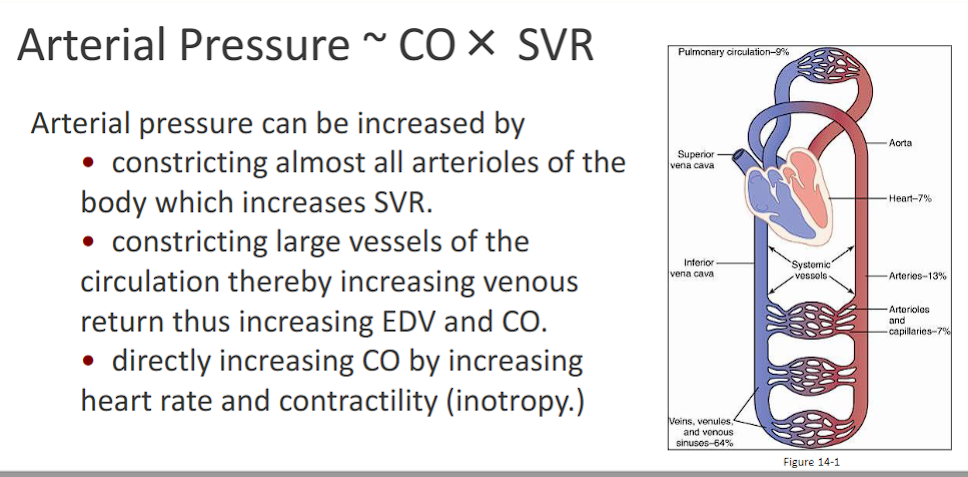

ANS control of arterial pressure (AP)?

the ANS uses the vasomotor center (VMC) is able to increase arterial pressure (AP) in seconds by:

Vasoconstriction (Arterial) which increases SVR

Venoconstriction (Venous) which increases venous return (preload) and CO

directly increasing cardiac output by increasing heart rate and contractility

Rapid increases in arterial pressure can occur during exercise or with ‘fight or flight’ response

what is the purpose of what you just learned about the ANS?

for the ANS to be able to control the arterial pressure (AP)

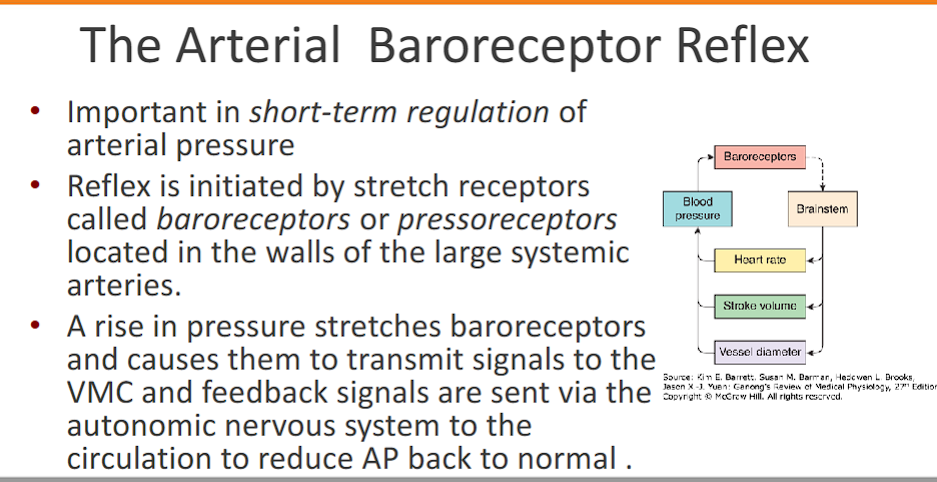

(the arterial baroreceptor reflex)

what is the relationship between baroreceptors and arterial pressure?

where are baroreceptors located?

how do baroreceptors control arterial pressure?

Important in short-term regulation of arterial pressure

baro: pressure

Reflex is initiated by stretch receptors called baroreceptors or pressoreceptors located in the walls of the large systemic arteries.

A rise in pressure stretches baroreceptors and causes them to send signals to the VMC

VMC sends feedback signals are sent via the autonomic nervous system (PSNS or SNS) to the circulation to reduce AP back to normal.

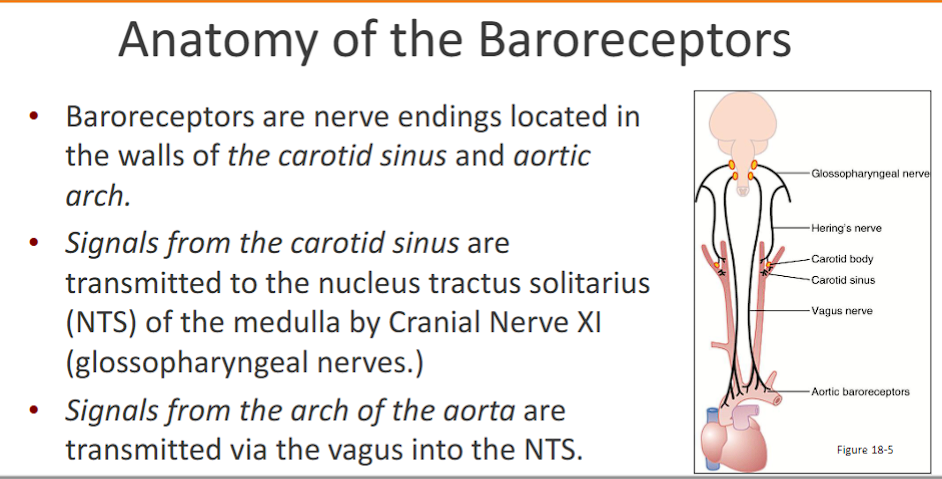

(anatomy of baroreceptors)

where are baroreceptors located?

where do the baroreceptors in the carotid sinus send signals? (where specifically in the medulla, because the medulla has the VMC)

where do the baroreceptors in the aortic arch send signals? (where specifically in the medulla, because the medulla has the VMC)

Baroreceptors are nerve endings located in the walls of the carotid sinus and aortic arch

Signals from the carotid sinus are transmitted to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) of the medulla by Cranial Nerve XI (glossopharyngeal nerves.) “tonge throat nerve”

Signals from the arch of the aorta are transmitted via the vagus into the NTS (Nucleus of the Tractus Solitarius)

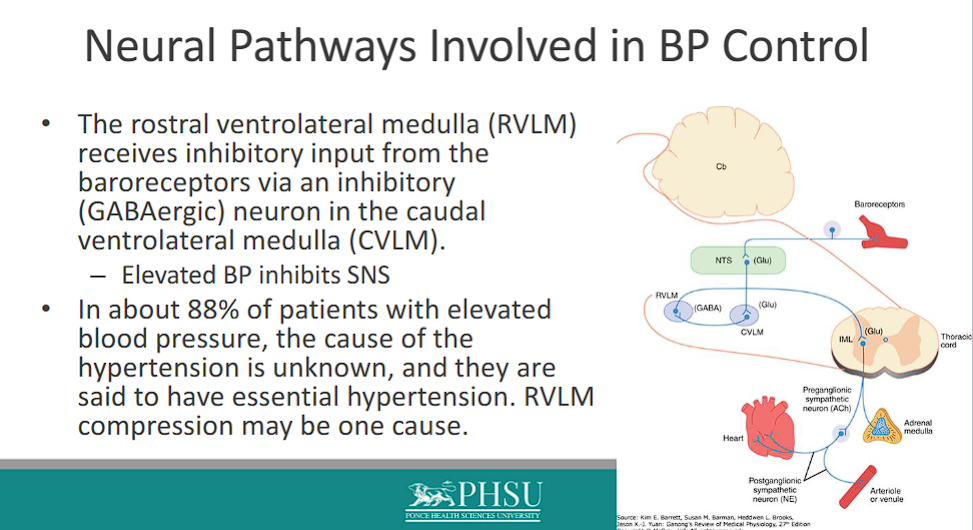

(Neural Pathways Involved in BP Control)

The rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) receives inhibitory input from the baroreceptors via an inhibitory (GABAergic) neuron in the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM)

High BP → Baroreceptors ↑ firing → NTS → Excites CVLM → CVLM Inhibits RVLM (via GABA) → ↓ Sympathetic Outflow → Vasodilation & ↓ Heart Rate → BP RETURNS TO NORMAL

RVLM (Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla): The "ON Switch" for blood pressure. It sends excitatory signals to the sympathetic nerves that constrict blood vessels and increase heart rate. If the RVLM is active, blood pressure goes up.

CVLM (Caudal Ventrolateral Medulla): The "OFF Switch" for the RVLM. Its job is to inhibit the RVLM.

NTS (Nucleus of the Tractus Solitarius): The "Sensory Hub." It receives all the sensory input about blood pressure from the baroreceptors.

– Elevated BP inhibits SNS

In about 88% of patients with elevated blood pressure, the cause of the hypertension is unknown, and they are said to have essential hypertension. RVLM compression may be one cause

what does an elevated blood pressure do the SNS?

– Elevated BP inhibits SNS

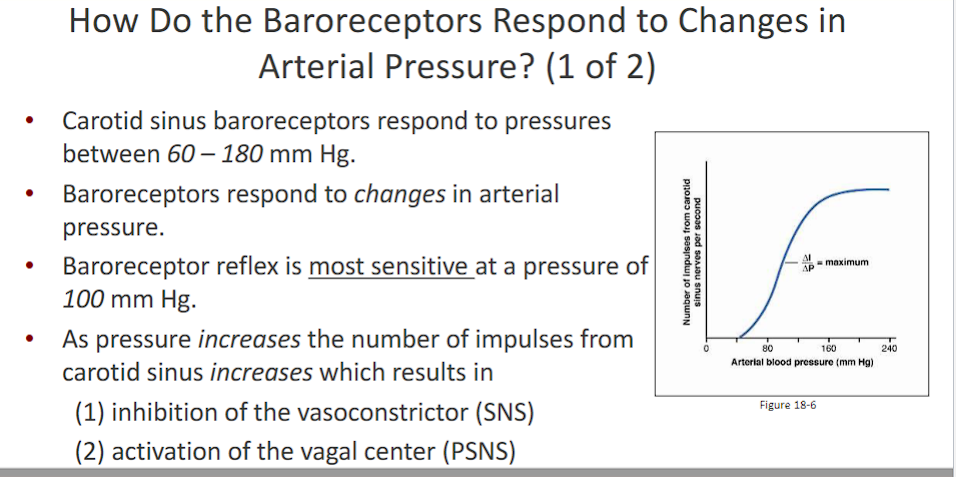

(How Do the Baroreceptors Respond to Changes in Arterial Pressure?)

what do baroreceptors do?

at what arterial pressure are baroreceptors most sensitive at?

Carotid sinus baroreceptors respond to pressures between 60 – 180 mm Hg.

• Baroreceptors respond to changes in arterial pressure.

• Baroreceptor reflex is most sensitive at a pressure of 100 mm Hg.

• As pressure increases the number of impulses from carotid sinus increases which results in

(1) inhibition of the vasoconstrictor (SNS)

(2) activation of the vagal center (PSNS)

Constrict Carotids (constriction= less pressure= less stretcing)→ ↓ Pressure in Carotid Sinus → ↓ Baroreceptor Firing → Medulla (NTS/VMC) → ↑ Sympathetic Outflow & ↓ Parasympathetic Outflow → ↑ Heart Rate & ↑ Vasoconstriction → ↑ Arterial Pressure

what does vagal center mean?

PSNS

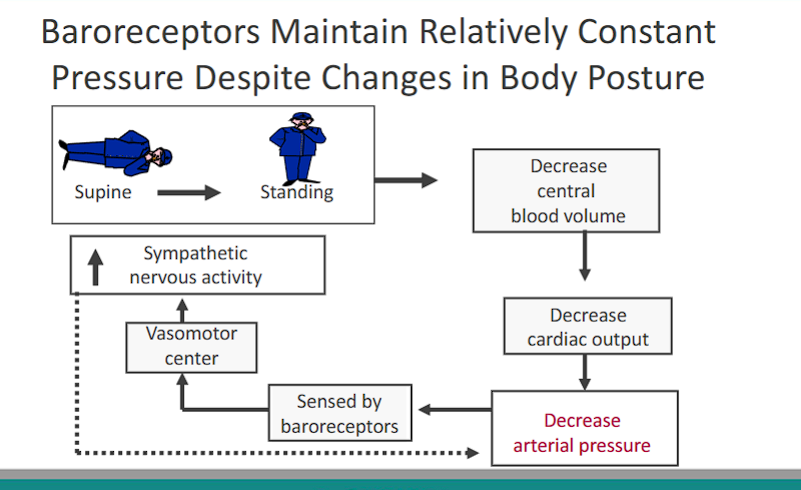

what is the relationship between baroreceptors and body posture

Baroreceptors Maintain Relatively Constant Pressure Despite Changes in Body Posture

Carotid and Aortic Chemoreceptors

what are the three things chemoreceptors detect?

where are chemoreceptors located?

what does activation of chemoreceptors cause?

when are chemoreceptors stimulated?

Chemo: chemistry

Chemoreceptors are chemosensitive cells sensitive to low oxygen, CO2 excess, or low pH.

Chemoreceptors are located in carotid bodies near the carotid bifurcation and on the arch of the aorta

Activation of chemosensitive receptors results in excitation of the vasomotor center = increased sympathetic nervous system.

Chemoreceptors are not stimulated until pressure falls below 80 mm Hg

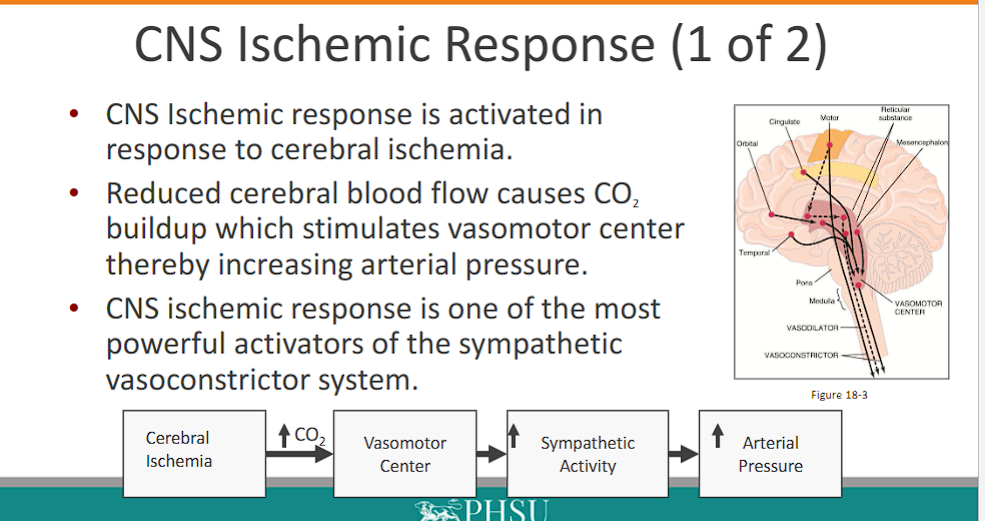

CNS Ischemic Response

Cerebral: From Latin cerebrum, meaning "brain."

Ischemia: From Greek isch- (ἴσχω, ischō), meaning "to restrict" or "to hold back," and -emia (αἷμα, haima), meaning "blood."

translation: "A restriction of blood to the brain."

CNS Ischemic response is activated in response to cerebral ischemia

the brain is a metabolic powerhouse that relies on blood for the export of metabolic byproduct of CO2. however, when blood flow is reduced (cerebral ischemia) but CO2 is still being produced, CO2 buildup occurs.

Reduced cerebral blood flow causes CO2 buildup which stimulates chemoreceptors, which stimulates vasomotor center thereby increasing arterial pressure (and hyperventilation)

CNS ischemic response is one of the most powerful activators of the sympathetic vasoconstrictor system.

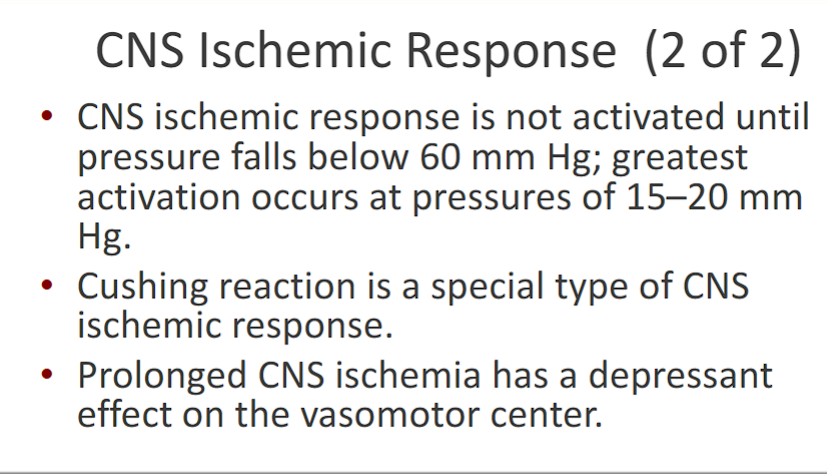

CNS Ischemic Response (2 of 2)

when is the CNS ischemic response activated?

when is the greatest CNS ischemic response?

CNS ischemic response is not activated until pressure falls below 60 mm Hg; greatest activation occurs at pressures of 15–20 mm Hg.

Cushing reaction is a special type of CNS ischemic response

Prolonged CNS ischemia has a depressant effect on the vasomotor center.

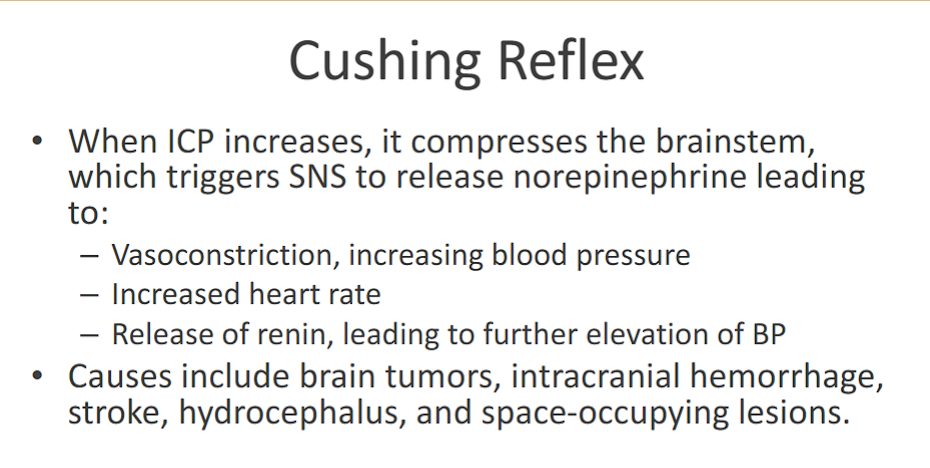

Cushing Reflex

"Cushing Reflex" does not describe the mechanism in its name. Instead, it honors the individual who first characterized the phenomenon.

Cushing reaction is a special type of CNS ischemic response.

The Cushing Reflex is a specific triad of clinical signs that occur when Intracranial Pressure (ICP) rises to a critical level, compressing the brain and its blood vessels. The classic triad is:

Hypertension (High Systemic Blood Pressure)

Bradycardia (Slow Heart Rate)

Irregular Respiration

When ICP increases, it compresses the brainstem, which triggers SNS to release norepinephrine leading

to:

– Vasoconstriction, increasing blood pressure

– decreased heart rate (due to baroreceptors detecting increase in blood pressure)

– Release of renin, leading to further elevation of BP

Causes include brain tumors, intracranial hemorrhage, stroke, hydrocephalus, and space-occupying lesion

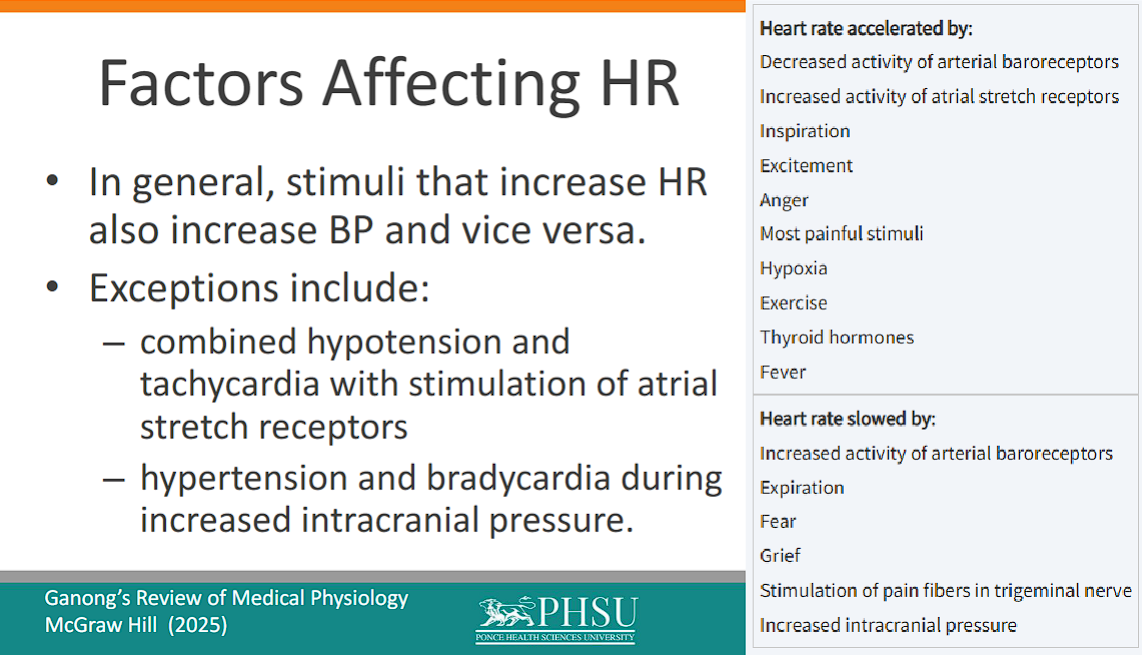

Factors affecting heart rate

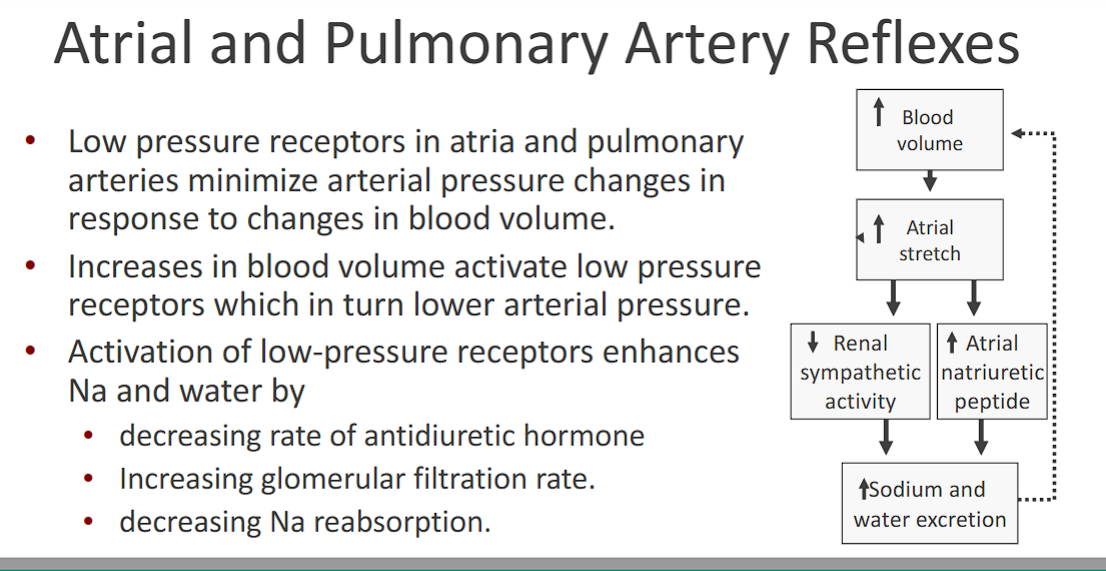

(Atrial and Pulmonary Artery Reflexes)

-Low pressure receptors in atria and pulmonary arteries minimize arterial pressure changes in response to changes in blood volume.

-Increases in blood volume activate low pressure receptors which in turn lower arterial pressure

low pressure receptors want to decrease AP.

-Activation of low-pressure receptors gets rid of Na and water by:

• decreasing rate of antidiuretic hormone

• Increasing glomerular filtration rate.

• decreasing Na reabsorption

blood volume increases

atrial stretch increases

low pressure receptors activate

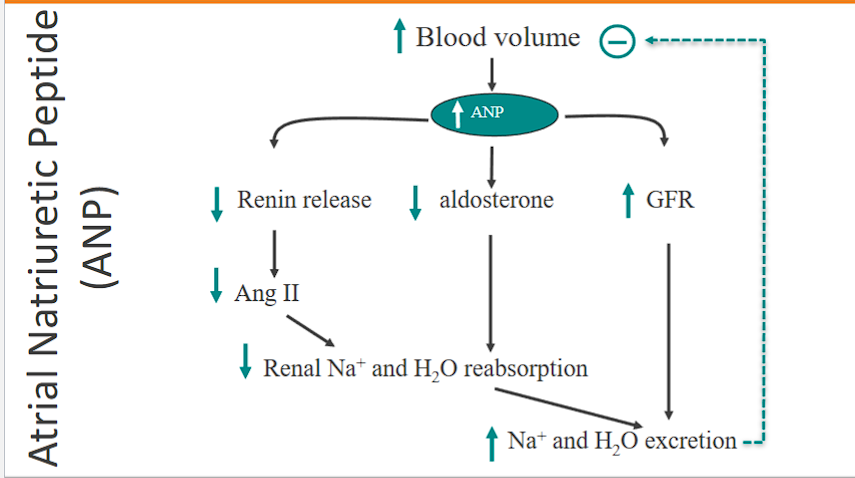

Renal sympathetic activity DECREASES and ANP INCREASES (anp is the OPPOSITE of vasopressin, ADP is the same as vasopressin)

decrease in blood volume achieved.

ANP, ADP, vasopressin

anp is the opposite of adh (vasopressin)

adh is antidieuretic, so it makes you retain water and sodium

anp (Atrial Natriuretic Peptide) is the opposite of adh, so it makes you lose water and sodium.

natriuretic= sodium passing through urine.

Bainbridge Reflex

bainbridge: the scientist

Prevents damming of blood in veins atria and pulmonary circulation, preventing congestion of blood.

The Bainbridge Reflex is a cardiovascular response that helps the heart manage a sudden increase in blood volume returning to the heart.

pressure increase (caused by sudden increase in blood volume due to blood transfusion, IV or exercise)

atrial stretch occurs

LOW PRESSURE BARORECEPTORS activated

stretch signals travel to vagal afferent nerves

VMC interprets signals

Efferent Response: The VMC responds by:

Withdrawing Parasympathetic (Vagal) Tone: This is the primary mechanism, leading to an increase in heart rate.

Increasing Sympathetic Outflow to the Heart: This can also contribute to increased heart rate and may enhance contractility

increase in contractility and heart rate to make the heart beat faster to move the extra blood.

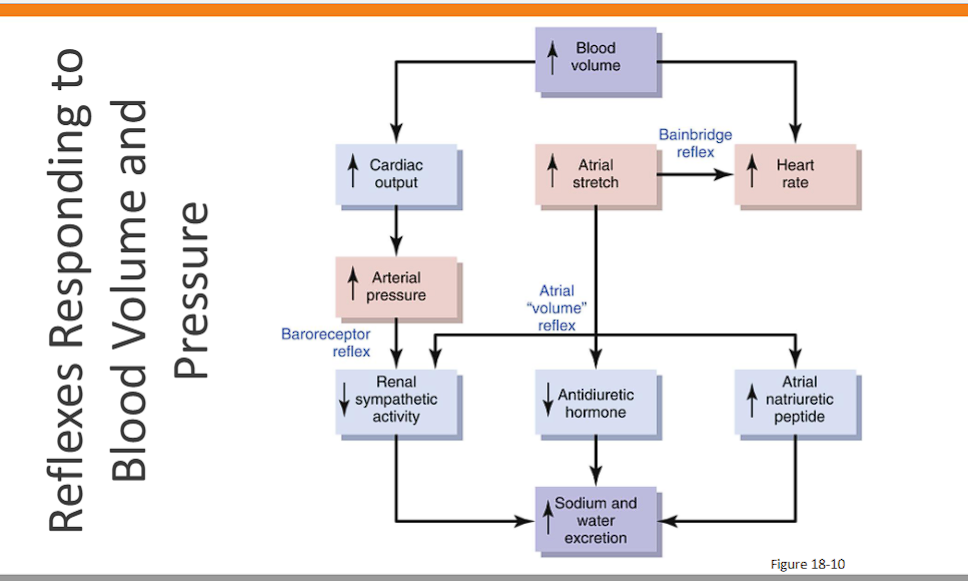

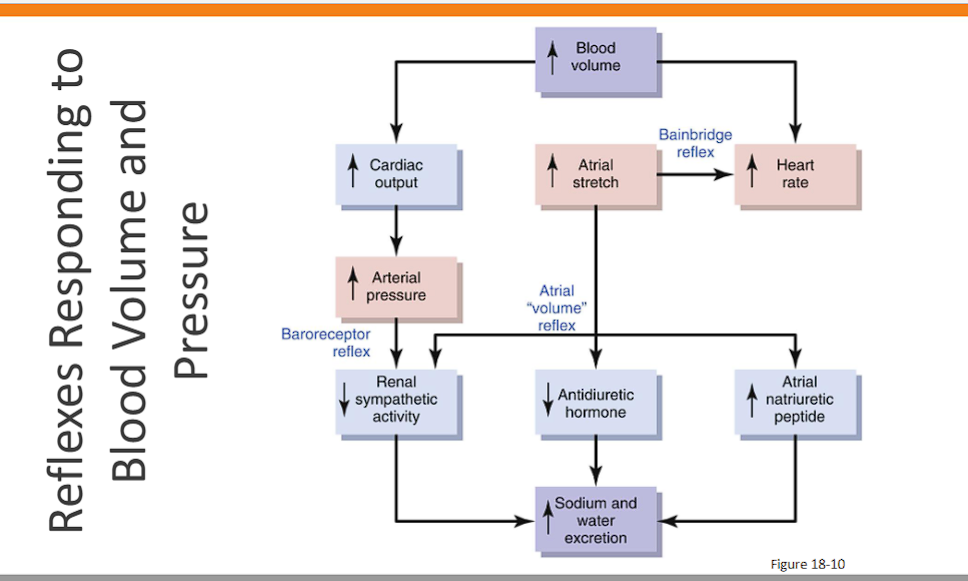

(Reflexes Responding to Blood Volume and Pressure)

baroreceptor reflex

baroreceptor reflex: increase in blood volume increases AP, more baroreceptors fire to lower the blood pressure, decreasing sympathetic renal activity to increase water and sodium excretion.

atrial volume reflex: The term "Atrial Volume Reflex" is essentially another name for the Bainbridge Reflex that you just described.

Renal Regulation of ECFV/BP

what is the relationship between ECFV and BP? (makes sense)

Plays a dominant role in long-term pressure control

direct relationship: As extracellular fluid volume increases arterial pressure increases.

The increase in arterial pressure causes the kidneys to lose Na and water which returns extracellular fluid volume (ECFV) to normal.

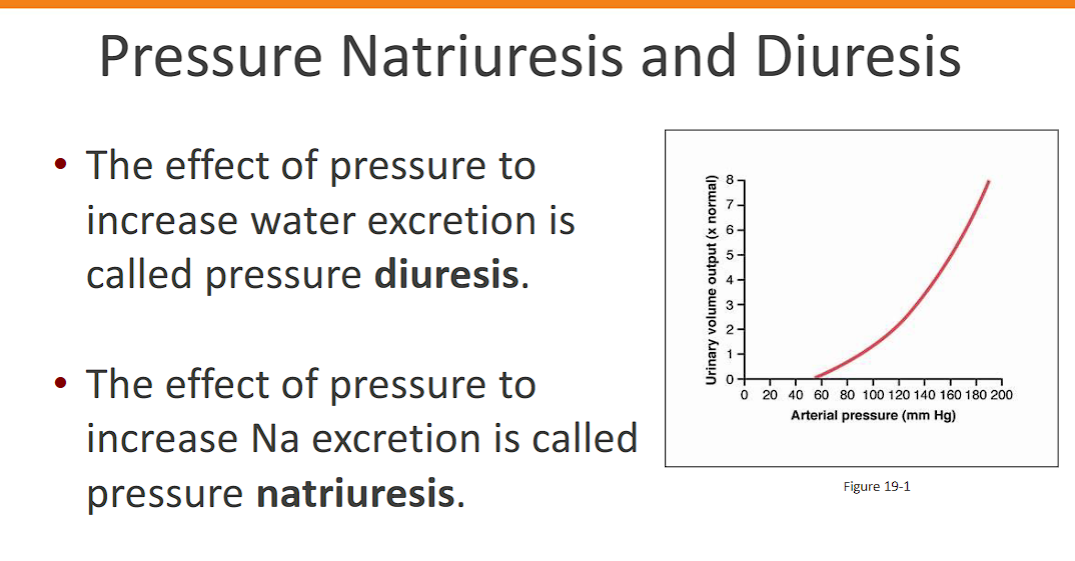

Pressure Natriuresis and Diuresis

The effect of pressure to increase water excretion is called pressure diuresis.

The effect of pressure to increase Na excretion is called pressure natriuresis.

if AP increases, these increase.

if AP decreases, these decrease

Together, they form the Pressure-Natriuresis-Diuresis Mechanism.

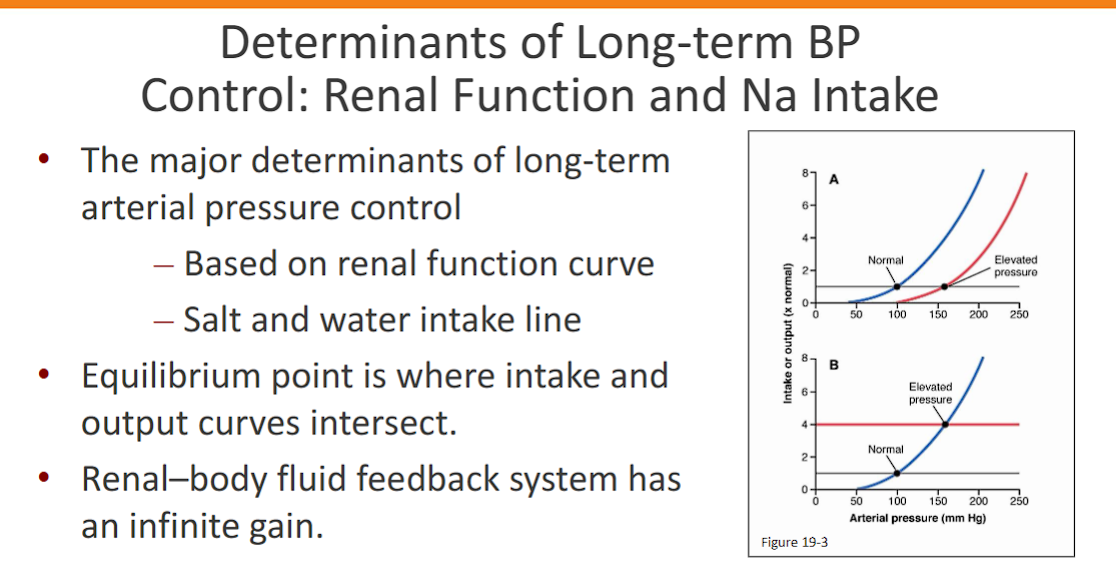

Determinants of Long-term BP Control: Renal Function and Na Intake

The major determinants of long-term

arterial pressure control

– Based on renal function curve

– Salt and water intake line

Equilibrium point is where intake and

output curves intersect.

• Renal–body fluid feedback system has

an infinite gain

What it is: This curve represents the kidney's response to pressure—the Pressure-Natriuresis-Diuresis mechanism we just discussed.

Shape: It is very steep. A small increase in arterial pressure causes a large increase in sodium and water excretion by the kidneys.

Meaning: The kidneys are exquisitely sensitive to pressure. If pressure rises even slightly, the kidneys will rapidly dump salt and water until the pressure is forced back down.

short term and long term blood pressure control.

baroreceptors and chemoreceptors are short term, renal function and na intake are long term blood pressure control

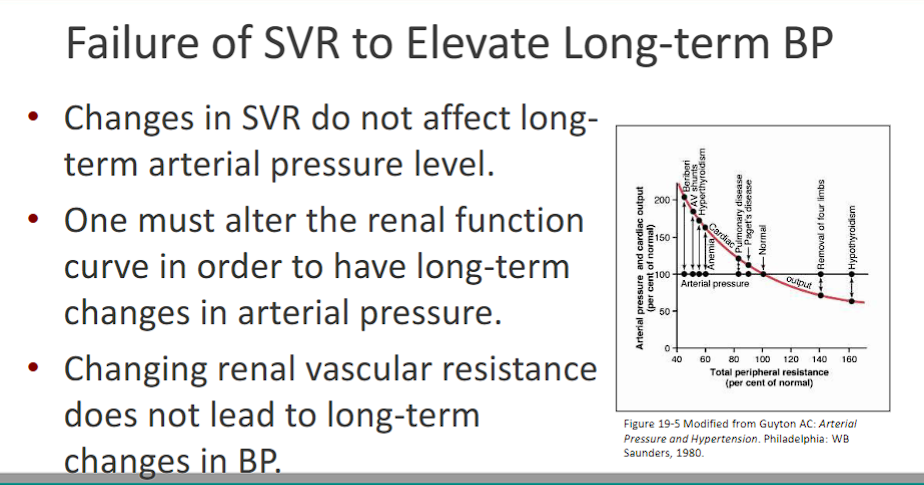

Failure of SVR to Elevate Long-term B

-Changes in SVR (vasoconstriction vasodilation) do not affect long- term arterial pressure level

-therefore, one must alter the renal function curve in order to have long-term changes in arterial pressure.

-Changing renal vascular resistance does not lead to long-term changes in BP.

MAKE SURE THE STATEMENT IS CORRECT

CHANGES IN RENAL VASCULAR RESISTANCE DOES NOT LEAD TO LONG TERM CHANGES IN BP.

RENAL NA AND WATER EXCRETION LEAD TO LONG TERM CHANGES IN BLOOD PRESSURE.

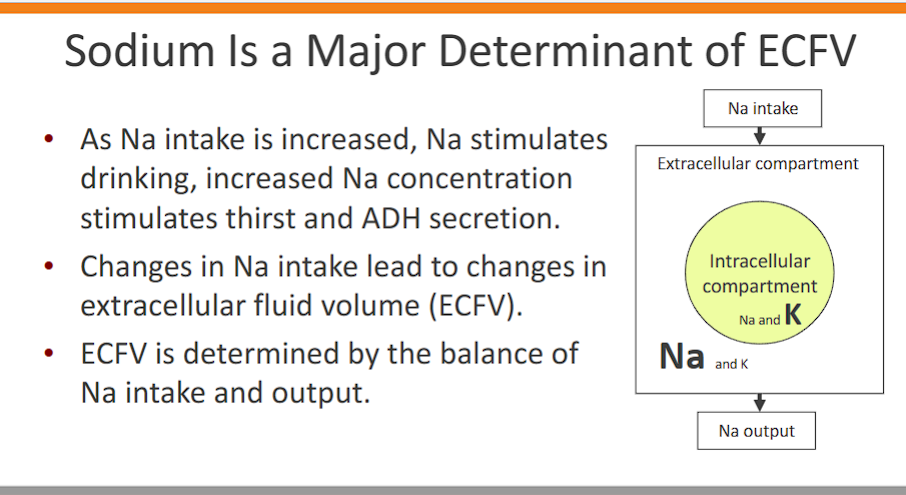

Sodium Is a Major Determinant of ECFV

-As Na intake is increased, Na stimulates drinking, increased Na concentration stimulates thirst and ADH secretion.

-Changes in Na intake lead to changes in extracellular fluid volume (ECFV).

-ECFV is determined by the balance of Na intake and output.

what does high blood osmolarity mean?

high salt

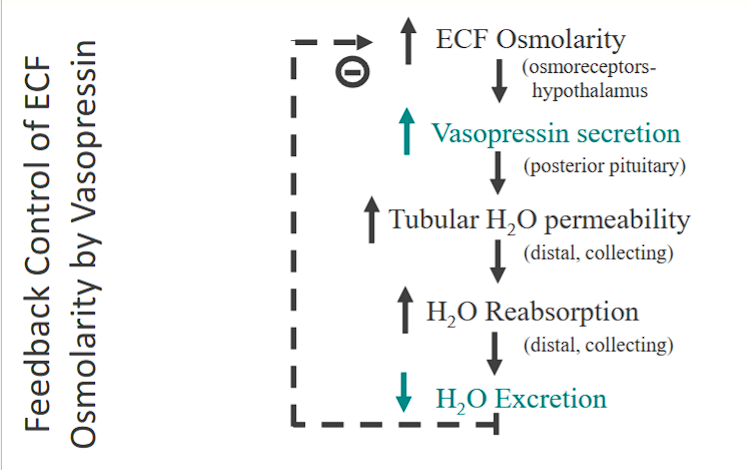

Feedback Control of ECF Osmolarity by Vasopressin

The Pathway (as you outlined):

Stimulus: ↑ ECF Osmolarity (high salt) (e.g., from dehydration or high salt intake).

Sensor: Osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus.

Control Center: Hypothalamus and Posterior Pituitary.

Effector/Hormone: ↑ Vasopressin (ADH) Secretion.

Action on Kidney: ↑ Tubular H₂O Permeability in the distal tubule and collecting duct.

Effect: ↑ H₂O Reabsorption, ↓ H₂O Excretion.

Final Result: ECF Osmolarity returns to normal.

ANP

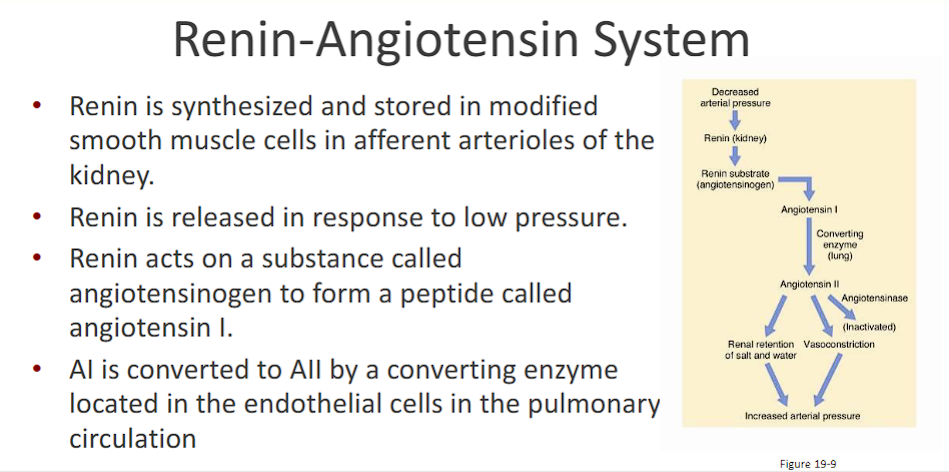

Renin-Angiotensin System

decreased arterial pressure

Renin release from the juxtaglomerular (JG) cells in the kidney is stimulated by three primary factors (low blood pressure in afferent, low sodium delivery, increase in sympathetic nervous system) in response to low blood pressure

Renin (from kidney) acts on Angiotensinogen (a protein made by the liver) to form Angiotensin I (a relatively inactive decapeptide).

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE), located predominantly on the surface of endothelial cells in the lungs, converts Angiotensin I into the highly active Angiotensin II (an octapeptide)

3. The Powerful Effects of Angiotensin II (AII)

Angiotensin II is the primary effector of the system and works through several mechanisms to raise blood pressure:Potent Vasoconstriction: Causes direct, powerful constriction of arterioles throughout the body, dramatically increasing Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR).

Stimulates Aldosterone Release: Acts on the adrenal cortex to release aldosterone. Aldosterone tells the kidneys to reabsorb more sodium (and consequently, water), which increases blood volume.

Stimulates ADH (Vasopressin) Release: Promotes water reabsorption by the kidneys to further increase blood volume.

Stimulates Thirst: In the brain, to promote fluid intake.

Increases Sympathetic Outflow: Amplifies the activity of the sympathetic nervous system

what are the three things angiotensin II does?

Potent Vasoconstriction to increase SVR

Stimulates Aldosterone Release to increase sodium retention to increase blood volume.

Stimulates ADH (Vasopressin) Release: increases water retention to increase blood volume.

Stimulates Thirst: In the brain, to promote fluid intake

Increases Sympathetic Outflow: Amplifies the activity of the sympathetic nervous system.

what is the GOAL of RAS?

The RAS is activated to correct low blood volume and low blood pressure. It does this by:

Constricting blood vessels (↑ SVR)

Conserving salt and water (↑ Blood Volume)

According to the equation Arterial Pressure = Cardiac Output × Systemic Vascular Resistance, the RAS powerfully increases both components on the right side of the equation to raise arterial pressure.

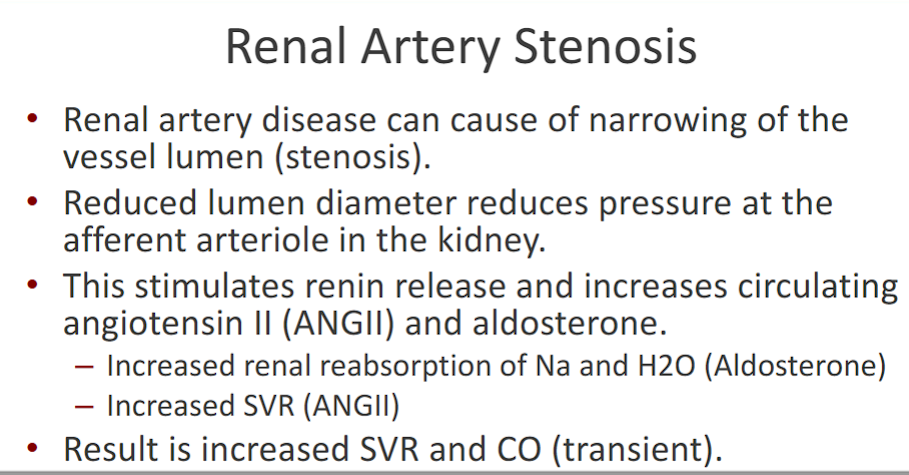

Renal Artery Stenosis

-narrowing of the AFFERENT renal artery

-Reduced lumen diameter reduces pressure at the afferent arteriole in the kidney

the reduced pressure due to the narrowing: stimulates renin release and increases circulating angiotensin II (ANGII) and aldosterone.

– Increased renal reabsorption of Na and H2O (Aldosterone)

– Increased SVR (ANGII)

• Result is increased SVR and CO (transient)

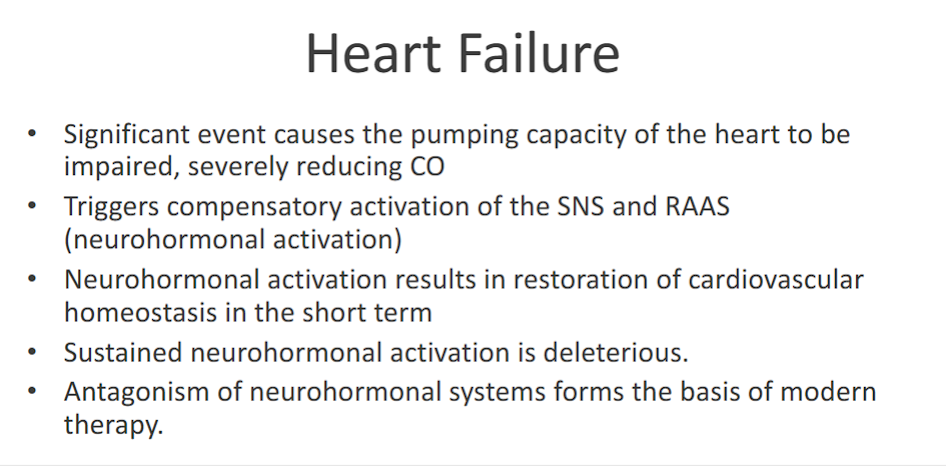

Heart Failure

1. The Initial Insult ("Significant Event")

Myocardial infarction (most common), hypertension, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, etc.

Effect: Damaged or overworked heart muscle leads to impaired pumping capacity and a severely reduced Cardiac Output (CO).

2. Compensatory Neurohormonal Activation

The body misinterprets the low CO as a sign of low blood volume/pressure and activates its classic "rescue" systems:

Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS): The first and fastest responder.

Goal: Increase CO and BP.

Effects: Tachycardia, increased contractility, and systemic vasoconstriction.

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): A slower but powerful hormonal response.

Goal: Increase blood volume and BP.

Effects: Angiotensin II causes potent vasoconstriction and thirst. Aldosterone causes sodium and water retention.

3. The Double-Edged Sword: Short-Term Gain vs. Long-Term Pain

Short-Term Restoration of Homeostasis: Initially, these responses are beneficial. They help maintain blood pressure and perfusion to vital organs by:

Supporting a failing heart rate and contractility.

Maintaining central blood volume.

Sustained Deleterious Effects: When these systems remain chronically active, they become toxic to the cardiovascular system:

Tachycardia & High Contractility: Increase myocardial oxygen demand, straining the failing heart and potentially leading to arrhythmias.

Vasoconstriction: Increases the afterload (the pressure the heart must pump against). This further reduces stroke volume and CO, worsening the heart's efficiency.

Sodium & Water Retention: Increases the preload (the volume of blood the heart must pump). In a stiff, failing heart, this leads to elevated filling pressures, causing pulmonary congestion (shortness of breath) and peripheral edema (swelling).

The Result: A vicious cycle where the very mechanisms meant to save the system end up accelerating its decline.

Heart Failure Treatment (going against the body’s mechanisms for treatment of the heart)

The Basis of Modern Therapy: Breaking the Cycle

As you correctly stated, antagonizing these neurohormonal systems is the cornerstone of heart failure management.

Beta-Blockers: Antagonize the SNS. They slow heart rate, reduce contractility (reducing oxygen demand), and have anti-arrhythmic effects.

ACE Inhibitors (or ARBs): Antagonize the RAAS. They prevent the formation/action of Angiotensin II, leading to vasodilation (↓ afterload), reduced aldosterone (↓ fluid retention), and prevention of harmful cardiac remodeling.

Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (e.g., Spironolactone): Directly block aldosterone, further promoting diuresis and preventing fibrosis.

Diuretics: While not direct neurohormonal blockers, they are used to counteract the fluid-retaining effects of the activated RAAS and SNS, relieving symptoms of congestion.

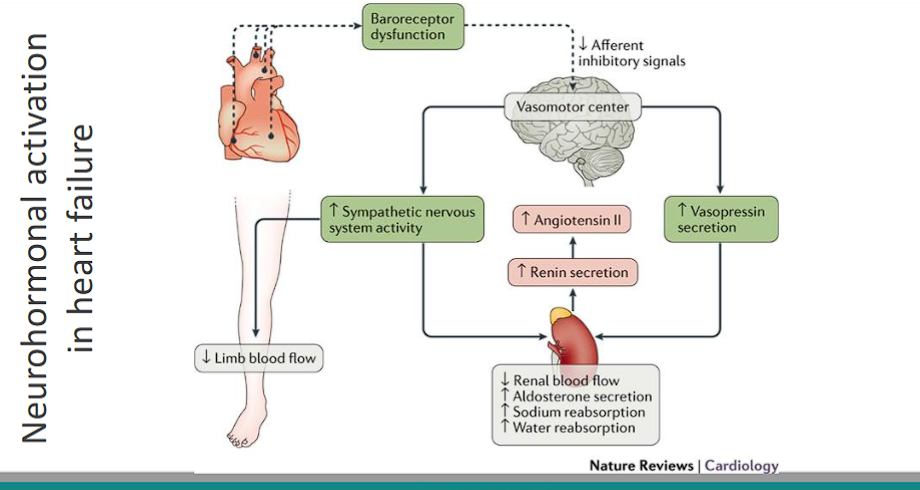

Neurohormonal activation in heart failure

-sympathetic nervous system norepinephrine (neurotransmitter)

-hormone (RAAS, vasopressin)

heart dysfunction

baroreceptor dysfunction

afferent inhibitory signals sent to VMC

VMC increases sympathetic output and increases vasopressin secretion

Kidney increases renin → angiotensin II

increased angiotensin II leads to DECREASED RENAL BLOOD FLOW, increased ALDOSTERONE, INCREASED SODIUM reabsorption and INCREASED water reabsorption.

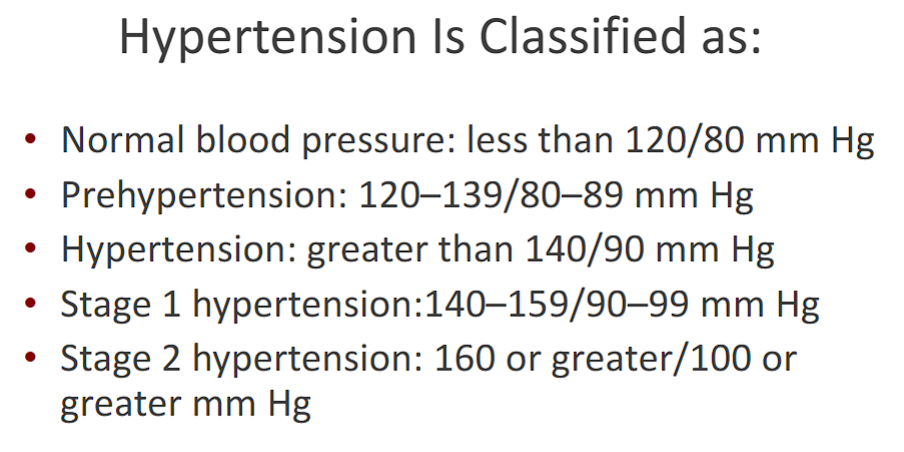

(Hypertension Is Classified as)

Prehypertension

Hypertension

Stage 1 hypertension

Stage 2 hypertension

Normal blood pressure: < 120/80 mm Hg

• Prehypertension: 120–139/80–89 mm Hg

• Hypertension: greater than 140/90 mm Hg

• Stage 1 hypertension:140–159/90–99 mm Hg

• Stage 2 hypertension: 160 or greater/100 or greater mm Hg

Primary or Essential Hypertension (weight gain)

90% of hypertensive patients

• Mild form of hypertension, slow progression

• Cause is unknown but most likely related to weight gain.

• 2/3 of essential hypertensives are overweight

Treating Hypertension (you already went over this)

Drugs used to treat hypertension include:

• Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

• Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

• Diuretics

• Beta-blockers

• Calcium channel blockers

Describe the origin and distribution of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves to the heart and circulation. (learning objective)

Here is a detailed description of the origin and distribution of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves to the heart and circulation.

Overview

The autonomic nervous system regulates cardiac and vascular function through two opposing branches: the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic systems. Their general effects are:

Sympathetic ("Fight-or-Flight"): Increases heart rate, contractility, and causes vasoconstriction in most vascular beds to elevate blood pressure and redirect blood flow.

Parasympathetic ("Rest-and-Digest"): Decreases heart rate and contractility (with a much stronger effect on rate). It has minimal direct innervation of blood vessels, with key exceptions.

Sympathetic Innervation

1. Origin: The Thoracolumbar Outflow

Sympathetic nerves to the heart and circulation originate from the intermediolateral (IML) cell column (the lateral horn) of the spinal cord.

For the Heart: Preganglionic neurons arise from spinal cord segments T1 to T4/T5.

For the Vasculature: Preganglionic neurons for blood vessels throughout the body arise from segments T1 to L2/L3. This is why it's called the thoracolumbar outflow.

2. Pathway and Distribution

The pathway involves a two-neuron chain: a preganglionic neuron and a postganglionic neuron.

A. To the Heart:

Preganglionic Fibers: The axons from T1-T4 neurons leave the spinal cord via the ventral roots and enter the sympathetic chain (a bundle of ganglia running parallel to the spine) via white rami communicantes.

Synapse: These fibers ascend within the chain and synapse with postganglionic neuronal cell bodies located in the cervical and upper thoracic ganglia (specifically the superior, middle, and stellate ganglia).

Postganglionic Fibers: From these ganglia, the postganglionic fibers form several cardiac nerves (superior, middle, and inferior cervical cardiac nerves, and thoracic cardiac nerves).

Innervation: These cardiac nerves proceed to the cardiac plexus (a network of nerves at the base of the heart) and then distribute widely to:

Sinoatrial (SA) Node: To increase heart rate.

Atrioventricular (AV) Node: To increase conduction velocity.

Atrial and Ventricular Myocardium: To increase the force of contraction.

B. To the Blood Vessels (Vascularure):

Preganglionic Fibers: The axons from T1-L2 neurons enter the sympathetic chain.

Synapse: They can synapse at the same level, ascend/descend to synapse at a different level, or pass through the chain without synapsing to form splanchnic nerves that synapse in prevertebral ganglia (e.g., celiac, superior mesenteric).

Postganglionic Fibers:

For limbs and body wall: From the chain ganglia, postganglionic fibers travel via gray rami communicantes to join spinal nerves, which then distribute to blood vessels (especially arterioles) in the skin, skeletal muscle, and other somatic tissues.

For viscera: From the prevertebral ganglia, postganglionic fibers follow arteries to reach the blood vessels of the abdominal and pelvic organs.

Effect: The primary effect is vasoconstriction via the release of norepinephrine. The only major exception is in skeletal muscle, where sympathetic cholinergic fibers can cause vasodilation during stress (the "get-ready" response).

Parasympathetic Innervation

1. Origin: The Craniosacral Outflow

Parasympathetic nerves originate from the brainstem and the sacral spinal cord. For the heart and thoracic vasculature, the source is exclusively cranial, specifically the Vagus Nerves (Cranial Nerve X).

Preganglionic neuronal cell bodies are located in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus in the medulla oblongata.

2. Pathway and Distribution

The pathway also uses a two-neuron chain, but the ganglia are located very close to or within the target organ.

A. To the Heart:

Preganglionic Fibers: The axons travel down within the vagus nerves (left and right) through the neck and thorax.

Synapse: These long preganglionic fibers do not synapse until they reach the cardiac plexus. Here, they synapse with postganglionic neuronal cell bodies located in small ganglia embedded in the plexus or within the walls of the atria themselves (e.g., the ganglia subdividing into the SA and AV nodes).

Postganglionic Fibers: These are very short and project directly to their target structures:

SA Node: To decrease heart rate (strong effect).

AV Node: To decrease conduction velocity (strong effect).

Atrial Myocardium: To decrease the force of contraction (moderate effect).

Ventricular Myocardium: Very sparse innervation; the parasympathetic system has a minimal direct effect on ventricular contractility.

B. To the Blood Vessels (Vascularure):

The parasympathetic system has very limited and specific distribution to blood vessels. It does not provide widespread innervation like the sympathetic system.

Regions Innervated: It primarily innervates blood vessels of certain exocrine glands (salivary, lacrimal, gastric) to promote vasodilation and secretion, and vessels of the external genitalia for erection (via pelvic splanchnic nerves, S2-S4).

Pathway: Preganglionic fibers in the vagus nerve synapse in ganglia near the specific organs (e.g., otic, pterygopalatine), and very short postganglionic fibers release Acetylcholine (ACh), which triggers vasodilation indirectly, often through the release of Nitric Oxide (NO).

General Systemic Circulation: Most arterioles and veins do not receive parasympathetic innervation. Systemic blood pressure is primarily regulated by the sympathetic nervous system.

Summary Table

Feature | Sympathetic Nerves | Parasympathetic Nerves |

|---|---|---|

Origin (Outflow) | Thoracolumbar (T1-L2) | Cranial (Vagus Nerve, CN X) & Sacral |

Preganglionic Neurotransmitter | Acetylcholine (ACh) | Acetylcholine (ACh) |

Postganglionic Neurotransmitter | Norepinephrine (NE) | Acetylcholine (ACh) |

Ganglion Location | Near Spine (Paravertebral/Prevertebral) | Near or within the Heart |

Innervation of Heart | SA Node, AV Node, Atria, Ventricles | SA Node, AV Node, Atria (ventricles sparse) |

Cardiac Effect | ↑ HR (Chronotropy), ↑ Contractility (Inotropy) | ↓ HR (Chronotropy), ↓ Atrial Contractility |

Innervation of Vasculature | Widespread: Skin, Gut, Skeletal Muscle, etc. | Limited & Specific: Glands, Genitalia |

Vascular Effect | Vasoconstriction (primarily); Vasodilation in skeletal muscle | Vasodilation (in specific beds) |

autonomic nervous system (overview)

effect of sympathetic nervous system on heart rate, contractility, vasoconstriction and vasodilation

effect of parasympathetic nervous system on heart rate, contractility, vasoconstriction and vasodilation

The autonomic nervous system regulates cardiac and vascular function through two opposing branches: the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic systems. Their general effects are:

Sympathetic ("Fight-or-Flight"): Increases heart rate, increases contractility, and causes vasoconstriction in most vascular beds to elevate blood pressure and redirect blood flow.

Parasympathetic ("Rest-and-Digest"): Decreases heart rate and decreases contractility (with a much stronger effect on rate). It has minimal direct innervation of blood vessels, with key exceptions.

Sympathetic Innervation

origin (intermediolateral cell column)

pathway

synapse

innervation

parasympathetic innervation

Sympathetic Innervation

1. Origin: The Thoracolumbar Outflow

Sympathetic nerves to the heart and circulation originate from the intermediolateral (IML) cell column (the lateral dshorn) of the spinal cord.

For the Heart: Preganglionic neurons arise from spinal cord segments T1 to T4/T5.

For the Vasculature: Preganglionic neurons for blood vessels throughout the body arise from segments T1 to L2/L3. This is why it's called the thoracolumbar outflow.

2. Pathway and Distribution

The pathway involves a two-neuron chain: a preganglionic neuron and a postganglionic neuron.

A. To the Heart:

Preganglionic Fibers: The axons from T1-T4 neurons leave the spinal cord via the ventral roots and enter the sympathetic chain (a bundle of ganglia running parallel to the spine) via white rami communicantes.

Synapse: These fibers ascend within the chain and synapse with postganglionic neuronal cell bodies located in the cervical and upper thoracic ganglia (specifically the superior, middle, and stellate ganglia).

Postganglionic Fibers: From these ganglia, the postganglionic fibers form several cardiac nerves (superior, middle, and inferior cervical cardiac nerves, and thoracic cardiac nerves).

Innervation: These cardiac nerves proceed to the cardiac plexus (a network of nerves at the base of the heart) and then distribute widely to:

Sinoatrial (SA) Node: To increase heart rate.

Atrioventricular (AV) Node: To increase conduction velocity.

Atrial and Ventricular Myocardium: To increase the force of contraction.

B. To the Blood Vessels (Vascularure):

Preganglionic Fibers: The axons from T1-L2 neurons enter the sympathetic chain.

Synapse: They can synapse at the same level, ascend/descend to synapse at a different level, or pass through the chain without synapsing to form splanchnic nerves that synapse in prevertebral ganglia (e.g., celiac, superior mesenteric).

Postganglionic Fibers:

For limbs and body wall: From the chain ganglia, postganglionic fibers travel via gray rami communicantes to join spinal nerves, which then distribute to blood vessels (especially arterioles) in the skin, skeletal muscle, and other somatic tissues.

For viscera: From the prevertebral ganglia, postganglionic fibers follow arteries to reach the blood vessels of the abdominal and pelvic organs.

Effect: The primary effect is vasoconstriction via the release of norepinephrine. The only major exception is in skeletal muscle, where sympathetic cholinergic fibers can cause vasodilation during stress (the "get-ready" response).

Parasympathetic innervation

origin

pathway and distribution to the heart

pathway and distribution to the blood vessels.

Parasympathetic Innervation

1. Origin: The Craniosacral Outflow

Parasympathetic nerves originate from the brainstem and the sacral spinal cord. For the heart and thoracic vasculature, the source is exclusively cranial, specifically the Vagus Nerves (Cranial Nerve X).

Preganglionic neuronal cell bodies are located in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus in the medulla oblongata.

2. Pathway and Distribution

The pathway also uses a two-neuron chain, but the ganglia are located very close to or within the target organ.

A. To the Heart:

Preganglionic Fibers: The axons travel down within the vagus nerves (left and right) through the neck and thorax.

Synapse: These long preganglionic fibers do not synapse until they reach the cardiac plexus. Here, they synapse with postganglionic neuronal cell bodies located in small ganglia embedded in the plexus or within the walls of the atria themselves (e.g., the ganglia subdividing into the SA and AV nodes).

Postganglionic Fibers: These are very short and project directly to their target structures:

SA Node: To decrease heart rate (strong effect).

AV Node: To decrease conduction velocity (strong effect).

Atrial Myocardium: To decrease the force of contraction (moderate effect).

Ventricular Myocardium: Very sparse innervation; the parasympathetic system has a minimal direct effect on ventricular contractility.

B. To the Blood Vessels (Vascularure):

The parasympathetic system has very limited and specific distribution to blood vessels. It does not provide widespread innervation like the sympathetic system.

Regions Innervated: It primarily innervates blood vessels of certain exocrine glands (salivary, lacrimal, gastric) to promote vasodilation and secretion, and vessels of the external genitalia for erection (via pelvic splanchnic nerves, S2-S4).

Pathway: Preganglionic fibers in the vagus nerve synapse in ganglia near the specific organs (e.g., otic, pterygopalatine), and very short postganglionic fibers release Acetylcholine (ACh), which triggers vasodilation indirectly, often through the release of Nitric Oxide (NO).

General Systemic Circulation: Most arterioles and veins do not receive parasympathetic innervation. Systemic blood pressure is primarily regulated by the sympathetic nervous system.

Know the location and function of alpha- and beta-adrenoceptors and muscarinic receptors in the heart and blood vessels.

Knowing the location and function of these receptors is fundamental to understanding cardiovascular physiology and pharmacology.

Here is a detailed breakdown of the location and function of alpha-adrenoceptors, beta-adrenoceptors, and muscarinic receptors in the heart and blood vessels.

Overview of Neurotransmitters

Sympathetic Nerves release Norepinephrine (and epinephrine from the adrenal medulla), which acts on alpha and beta-adrenoceptors.

Parasympathetic Nerves release Acetylcholine (ACh), which acts on muscarinic receptors.

1. Alpha-Adrenoceptors (α-receptors)

Alpha-receptors are primarily involved in vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels).

Location:

Blood Vessels: Predominantly located on vascular smooth muscle of most arterioles and veins.

α₁-receptors: Mainly post-synaptic, on the target organ (the blood vessel).

α₂-receptors: Primarily pre-synaptic (on the nerve terminal) where they act as auto-receptors to inhibit further norepinephrine release. Some are also post-synaptic on vascular smooth muscle.

Heart: Present in much lower density. Their role is less direct.

Function:

In Blood Vessels:

Vasoconstriction: When stimulated by norepinephrine, they cause the smooth muscle to contract. This:

Increases Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR) and therefore increases Arterial Blood Pressure.

Constricts veins, which increases venous return of blood to the heart.

In the Heart:

A minor role in potentiating the effects of beta-receptor stimulation, leading to a slight increase in contractility.

2. Beta-Adrenoceptors (β-receptors)

Beta-receptors have diverse effects, primarily increasing heart function and causing vasodilation in certain beds.

Location and Function by Subtype:

A. Beta-1 Receptors (β₁)

Location: Primarily in the heart.

SA Node

AV Node

Atrial and Ventricular Myocardium

Function:

SA Node: Increase Heart Rate (positive chronotropy).

AV Node: Increase Conduction Velocity (positive dromotropy).

Myocardium: Increase Force of Contraction (positive inotropy).

Overall Effect: To significantly increase Cardiac Output.

B. Beta-2 Receptors (β₂)

Location: Primarily on vascular smooth muscle of specific vascular beds.

Skeletal Muscle Arterioles

Coronary Arteries (heart's own blood supply)

Arteries to the Liver

Function:

Vasodilation: When stimulated by epinephrine (and to a lesser extent, norepinephrine), they cause smooth muscle relaxation. This:

Decreases Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR).

Redirects blood flow to skeletal muscle and the heart during "fight-or-flight."

Note: Beta-2 receptors are more sensitive to epinephrine (from the adrenal medulla) than to norepinephrine.

3. Muscarinic Receptors (M₂)

These are the primary receptors for parasympathetic (vagal) control of the heart. Parasympathetic innervation of most blood vessels is sparse, so the main cardiovascular effects are on the heart.

Location:

Heart: Primarily M₂ subtype.

SA Node

AV Node

Atrial Myocardium

(Ventricles have very few muscarinic receptors)

Blood Vessels:

Vascular Endothelium (inner lining): Muscarinic receptors (M₃) are present on the endothelial cells. They are not directly innervated by parasympathetic nerves but can be stimulated by circulating agonists.

Function:

In the Heart:

SA Node: Decreases Heart Rate (negative chronotropy) – the primary vagal effect.

AV Node: Decreases Conduction Velocity (negative dromotropy), which can slow or block transmission from atria to ventricles.

Atrial Myocardium: Decreases Force of Contraction (negative inotropy).

In Blood Vessels:

Indirect Vasodilation: When an agonist like ACh binds to M₃ receptors on the endothelium, it stimulates the production of Nitric Oxide (NO). NO diffuses to the underlying smooth muscle and causes relaxation and vasodilation.

Important Note: If the endothelium is damaged, ACh can bind to muscarinic receptors on the smooth muscle itself and cause weak vasoconstriction. This is a key difference in function based on location.

Summary Table for Quick Reference

Receptor Type | Primary Location | Effect when Stimulated | Mediator |

|---|---|---|---|

Alpha (α₁) | Vascular Smooth Muscle | Vasoconstriction (↑ BP) | Norepinephrine |

Beta-1 (β₁) | Heart (SA node, Myocardium) | ↑ HR, ↑ Contractility (↑ CO) | Norepinephrine |

Beta-2 (β₂) | Vascular Smooth Muscle (Skeletal, Coronary) | Vasodilation (↓ SVR) | Epinephrine |

Muscarinic (M₂) | Heart (SA node, AV node) | ↓ HR, ↓ Conduction Velocity | Acetylcholine (Vagus) |

Muscarinic (M₃) | Vascular Endothelium | Vasodilation (via NO) | Circulating Agonists |

Abbreviations: HR (Heart Rate), CO (Cardiac Output), BP (Blood Pressure), SVR (Systemic Vascular Resistance), NO (Nitric Oxide).

neurotransmitter and receptor for sympathetic nervous system

neurotransmitter and receptor for parasympathetic nervous system

Overview of Neurotransmitters

Sympathetic Nerves release Norepinephrine (and epinephrine from the adrenal medulla), which acts on alpha and beta-adrenoceptors.

Parasympathetic Nerves release Acetylcholine (ACh), which acts on muscarinic receptors.

summary table

Summary Table for Quick Reference

a2 is NOT IN THE CHART

Receptor Type | Primary Location | Effect when Stimulated | Mediator |

|---|---|---|---|

Alpha (α₁) (sympathetic) | Vascular Smooth Muscle | Vasoconstriction (↑ BP) | Norepinephrine |

Beta-1 (β₁) (sympathetic) | Heart (SA node, Myocardium) | ↑ HR, ↑ Contractility (↑ CO) | Norepinephrine |

Beta-2 (β₂) (sympathetic) | Vascular Smooth Muscle (Skeletal, Coronary) | Vasodilation (↓ SVR) | Epinephrine |

Muscarinic (M₂) (parasympathetic) | Heart (SA node, AV node) | ↓ HR, ↓ Conduction Velocity | Acetylcholine (Vagus) |

Muscarinic (M₃) (parasympathetic) | Vascular Endothelium | Vasodilation (via NO) | Circulating Agonists |

Abbreviations: HR (Heart Rate), CO (Cardiac Output), BP (Blood Pressure), SVR (Systemic Vascular Resistance), NO (Nitric Oxide).

a1 receptor (sympathetic nervous system)

a1 used to increase blood pressure

Alpha (α₁) | Vascular Smooth Muscle | Vasoconstriction (↑ BP) | Norepinephrine |

b1 receptor (sympathetic nervous system)

b1 used into increase cardiac ouput.

Beta-1 (β₁) | Heart (SA node, Myocardium) | ↑ HR, ↑ Contractility (↑ CO) | Norepinephrine |

b2 receptor (sympathetic nervous system)

b2 used to increase SVR

Beta-2 (β₂) | Vascular Smooth Muscle (Skeletal, Coronary) | Vasodilation (↓ SVR) | Epinephrine |

a1 and b2 are both located in vascular smooth muscle, but have opposing effects and different neurotransmitters.

what is the similarity and difference between a1 and b2 receptors?

a1 and b2 are both located in vascular smooth muscle, but have opposing effects and different neurotransmitters.

M2 receptor (parasympathetic nervous system)

Muscarinic (M₂) | Heart (SA node, AV node) | ↓ HR, ↓ Conduction Velocity | Acetylcholine (Vagus) |

M3 (parasympathetic nervous system)

Muscarinic (M₃) | Vascular Endothelium | Vasodilation (via NO) | Circulating Agonists |

what is the difference between m2 and m3 receptors?

location, m2 is heart, m3 is vascular endothelium

m2 decreases heart rate and conduction velocity through acetylcholine reception

m3 causes vasodilation via nitric oxide.

Describe the effects of sympathetic and parasympathetic stimulation on the heart and circulation.

The sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) divisions of the autonomic nervous system have opposing and complementary effects on the cardiovascular system, allowing for precise control of cardiac output and blood pressure to meet the body's changing demands.

Here is a detailed description of their effects.

Executive Summary: Core Effects

Sympathetic Stimulation ("Fight-or-Flight"): Increases Cardiac Output and Redirects Blood Flow. It prepares the body for action.

Parasympathetic Stimulation ("Rest-and-Digest"): Decreases Cardiac Output and Promotes Digestion. It conserves energy and maintains basal bodily functions.

1. Effects of Sympathetic Stimulation

Sympathetic activation is a system-wide response, primarily mediated by the release of norepinephrine from nerve endings and epinephrine from the adrenal medulla, acting on alpha and beta-adrenoceptors.

On the Heart:

The goal is to dramatically increase Cardiac Output (CO = Heart Rate x Stroke Volume).

Heart Rate (Chronotropy):

Effect: Marked Increase.

Mechanism: Stimulation of Beta-1 (β₁) receptors on the Sinoatrial (SA) node increases its rate of spontaneous depolarization, accelerating the heart rate (tachycardia).

Contractility (Inotropy):

Effect: Marked Increase.

Mechanism: Stimulation of Beta-1 (β₁) receptors on the atrial and ventricular myocardium enhances the force of contraction. This results in a more powerful squeeze, ejecting more blood with each beat and increasing Stroke Volume.

Conduction Velocity (Dromotropy):

Effect: Increase.

Mechanism: Stimulation of Beta-1 (β₁) receptors on the Atrioventricular (AV) node increases the speed of electrical impulse conduction from the atria to the ventricles. This ensures the rapidly beating chambers remain synchronized.

Net Cardiac Effect: A large increase in Cardiac Output, providing more oxygenated blood to the body.

On the Circulation (Blood Vessels):

The goal is to increase Blood Pressure and redirect blood flow from non-essential organs to active skeletal muscle and the heart.

Systemic Vascular Resistance (Afterload):

Effect: Variable, but net increase.

Mechanism:

Vasoconstriction: Strong stimulation of Alpha-1 (α₁) receptors on vascular smooth muscle in most beds (e.g., skin, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys) causes pronounced vasoconstriction. This dramatically increases systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and arterial blood pressure.

Vasodilation: Stimulation of Beta-2 (β₂) receptors on vascular smooth muscle in skeletal muscle and the liver causes vasodilation. This shunts blood away from constricted areas and toward the muscles needed for action.

Venous Return (Preload):

Effect: Increase.

Mechanism: Constriction of veins (via α₁-receptors) reduces their capacity to hold blood. This "squeezes" more blood back to the heart, increasing venous return and preload, which further enhances stroke volume via the Frank-Starling mechanism.

Net Circulatory Effect: Elevated blood pressure and a redistribution of blood flow, prioritizing the brain, heart, and working muscles.

2. Effects of Parasympathetic (Vagal) Stimulation

Parasympathetic effects are more localized and discrete, mediated almost exclusively by the release of acetylcholine from the vagus nerve (CN X), acting on muscarinic receptors.

On the Heart:

The goal is to decrease Cardiac Output and conserve energy.

Heart Rate (Chronotropy):

Effect: Marked Decrease.

Mechanism: Stimulation of Muscarinic (M₂) receptors on the SA node hyperpolarizes the cells and decreases their rate of depolarization, significantly slowing the heart rate (bradycardia). This is the most powerful and pronounced effect of vagal stimulation.

Contractility (Inotropy):

Effect: Mild to Moderate Decrease (in atria).

Mechanism: Stimulation of M₂ receptors in the atrial myocardium reduces the force of contraction. The ventricles receive very little parasympathetic innervation, so the effect on overall contractility is limited.

Conduction Velocity (Dromotropy):

Effect: Decrease.

Mechanism: Stimulation of M₂ receptors on the AV node slows down impulse conduction, increasing the PR interval on an ECG. High vagal tone can even lead to a transient AV block.

Net Cardiac Effect: A pronounced decrease in Heart Rate, leading to a significant reduction in Cardiac Output.

On the Circulation (Blood Vessels):

Systemic Vascular Resistance:

Effect: Minimal Direct Effect.

Mechanism: Most blood vessels do not receive parasympathetic innervation. Therefore, vagal stimulation has little direct control over systemic vascular resistance. The primary control of vasodilation/vasoconstriction is sympathetic.

Exception: Parasympathetic nerves do cause vasodilation in specific, localized beds such as the salivary glands, glands of the GI tract, and external genitalia (erection) to support "rest-and-digest" functions. This is not a system-wide effect.

Summary Table: Opposing Effects

Target Organ | Sympathetic Effect | Parasympathetic Effect |

|---|---|---|

SA Node | ↑↑ Heart Rate (Tachycardia) | ↓↓ Heart Rate (Bradycardia) |

AV Node | ↑ Conduction Velocity | ↓ Conduction Velocity (AV Block) |

Atrial Muscle | ↑ Contractility | ↓ Contractility |

Ventricular Muscle | ↑↑ Contractility | Very Little Effect |

Arterioles | Constriction (most beds) / Dilation (skeletal muscle) | No Innervation (most beds) |

Veins | Constriction (↑ Venous Return) | No Innervation |

Overall Result | ↑ Cardiac Output, ↑ BP, Redirect Flow | ↓↓ Cardiac Output, Conserve Energy |

Physiological Integration

In a healthy person, there is a constant, dynamic interplay between these two systems—a phenomenon known as "autonomic tone."

At rest, parasympathetic (vagal) tone is dominant, which keeps the heart rate lower than the intrinsic rate of the SA node (e.g., 60-80 bpm instead of 100 bpm).

During exercise or stress, sympathetic tone increases and parasympathetic tone withdraws, allowing for a rapid and powerful increase in heart rate and contractility.

This precise balance allows for the fine-tuned, moment-to-moment regulation required to maintain cardiovascular homeostasis.

List the anatomical components of the baroreceptor reflex.

The baroreceptor reflex is the body's primary short-term mechanism for maintaining stable blood pressure. Its anatomical components form a classic negative feedback loop, comprising sensors, afferent pathways, an integration center, efferent pathways, and effector organs.

Here is a list of the key anatomical components.

Anatomical Components of the Baroreceptor Reflex1. Sensors (Baroreceptors / Pressoreceptors)

Location: Specialized stretch receptors located in the walls of specific arteries.

Carotid Sinus: A slight dilation at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, just before it branches into the internal and external carotid arteries. This is the most important site.

Aortic Arch: Located in the wall of the arch of the aorta.

Function: These receptors are sensitive to changes in arterial pressure. An increase in BP causes increased stretch of the arterial wall, leading to increased baroreceptor firing. A decrease in BP causes less stretch and decreased firing.

2. Afferent (Sensory) Pathways

Nerves: These carry the sensory information from the baroreceptors to the brain.

Glossopharyngeal Nerve (Cranial Nerve IX): Carries signals from the carotid sinus baroreceptors.

Vagus Nerve (Cranial Nerve X): Carries signals from the aortic arch baroreceptors.

3. Integration Center

Location: The Cardiovascular Center in the Medulla Oblongata of the brainstem.

Key Components:

Nucleus of the Solitary Tract (NTS): This is the primary site where the afferent nerves (CN IX and X) first synapse and relay the sensory input.

Other Medullary Centers: The NTS communicates with adjacent centers to coordinate the response:

Cardioinhibitory Center: Promotes parasympathetic (vagal) output.

Vasomotor Center: Controls sympathetic output to the heart and blood vessels.

4. Efferent (Motor) Pathways

Parasympathetic Pathway:

Nerve: The Vagus Nerve (Cranial Nerve X).

Target: The heart (SA node, AV node, atria).

Sympathetic Pathway:

Path: Preganglionic neurons from the vasomotor center descend the spinal cord and synapse in the intermediolateral (IML) cell column (T1-L2). Postganglionic neurons then exit the cord.

Nerves: Cardiac and Vasomotor Sympathetic Nerves.

Targets: The heart (SA node, AV node, myocardium) and vascular smooth muscle in arterioles and veins.

5. Effector Organs

The Heart:

SA Node: Changes heart rate.

AV Node: Changes conduction velocity.

Cardiac Muscle (Myocardium): Changes contractility (force of contraction).

Blood Vessels:

Arterioles (Resistance Vessels): Changes vascular tone, altering systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

Veins (Capacitance Vessels): Changes venous tone, altering venous return and preload.

Summary of the Reflex Arc in Action

Component | Anatomy Involved |

|---|---|

Sensor | Baroreceptors in Carotid Sinus & Aortic Arch |

Afferent Pathway | Glossopharyngeal Nerve (IX) & Vagus Nerve (X) |

Integration Center | Medulla Oblongata (NTS, Cardioinhibitory & Vasomotor Centers) |

Efferent Pathway | Vagus Nerve (X) & Sympathetic Nerves |

Effectors | Heart & Blood Vessels |

This elegant reflex allows for moment-to-moment adjustments, such as preventing a drop in blood pressure when you stand up (orthostatic hypotension) or moderating a spike in pressure during a stress response.

Describe how carotid sinus baroreceptors respond to changes in arterial pressure (mean pressure and pulse pressure), and explain how changes in baroreceptor activity affect sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow to the heart and circulation.

This is a core concept in cardiovascular physiology. Here is a detailed description of how carotid sinus baroreceptors function and how their signals are translated into autonomic responses.

1. How Baroreceptors Respond to Changes in Arterial Pressure

Carotid sinus baroreceptors are stretch-sensitive nerve endings embedded in the wall of the carotid sinus. They do not respond to pressure directly, but to the stretch of the arterial wall caused by that pressure.

Response to Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP)

MAP is the average pressure in the arteries throughout one cardiac cycle, representing the perfusion pressure driving blood to the tissues.

Relationship: Baroreceptor firing rate is directly proportional to MAP, but this relationship is not linear across all pressures. It follows a sigmoidal (S-shaped) curve.

Threshold: Below a MAP of ~50-60 mmHg, the vessel wall is under too little stretch, and baroreceptors are silent.

Sensitive Range: Between ~60-180 mmHg, the baroreceptors are exquisitely sensitive. Small changes in MAP produce large changes in firing rate. The normal operating point (around 100 mmHg) lies within this steep, sensitive region, allowing for precise control.

Saturation: Above ~180 mmHg, the vessel wall is maximally stretched, and baroreceptor firing reaches a plateau and cannot increase further.

Response to Pulse Pressure

Pulse Pressure is the difference between systolic and diastolic pressure (SBP - DBP). It is a reflection of stroke volume and arterial stiffness.

Relationship: At any given MAP, baroreceptors are more sensitive to a pulsatile pressure than to a steady pressure.

Mechanism: The rhythmic stretching and recoiling of the artery wall during each cardiac cycle cause a burst of baroreceptor action potentials with each pulse.

Effect: A higher pulse pressure (e.g., due to a larger stroke volume) results in a greater peak stretch during systole, leading to a higher overall average firing rate than a steady pressure at the same MAP would produce.

In summary: Baroreceptor firing encodes both the mean level of arterial pressure (over the sensitive range) and its pulsatile nature. Increased MAP or increased Pulse Pressure leads to increased baroreceptor firing.

2. How Baroreceptor Activity Affects Autonomic Outflow

The primary integration center for the baroreceptor reflex is the medulla oblongata, specifically the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract (NTS). The autonomic response is a classic negative feedback loop.

Scenario 1: Response to a RISE in Arterial Pressure (e.g., during stress)

Stimulus: ↑ Arterial Pressure → ↑ Stretch of Carotid Sinus.

Sensor: ↑ Firing rate of Carotid Sinus Baroreceptors.

Afferent Pathway: ↑ Firing in the Glossopharyngeal Nerve (CN IX).

Integration (Medulla):

The NTS is activated.

It stimulates the Cardioinhibitory Center (Parasympathetic).

It inhibits the Vasomotor Center (Sympathetic).

Efferent Outflow & Effector Response:

↑ Parasympathetic Outflow (Vagus Nerve):

Heart: Acts on the SA node to decrease Heart Rate (Bradycardia).

↓ Sympathetic Outflow:

Heart: Decreases heart rate and contractility.

Blood Vessels: Causes vasodilation in arterioles (decreasing Systemic Vascular Resistance) and veins (decreasing Venous Return).

Net Effect: ↓ Heart Rate, ↓ Contractility, ↓ Venous Return, ↓ Systemic Vascular Resistance → ↓ Cardiac Output & ↓ Arterial Pressure back toward normal.

Scenario 2: Response to a FALL in Arterial Pressure (e.g., upon standing)

Stimulus: ↓ Arterial Pressure → ↓ Stretch of Carotid Sinus.

Sensor: ↓ Firing rate of Carotid Sinus Baroreceptors.

Afferent Pathway: ↓ Firing in the Glossopharyngeal Nerve (CN IX).

Integration (Medulla):

The NTS is less activated.

It inhibits the Cardioinhibitory Center (Parasympathetic).

It stimulates the Vasomotor Center (Sympathetic).

Efferent Outflow & Effector Response:

↓ Parasympathetic Outflow (Vagus Nerve):

Heart: Withdraws the "brake" on the SA node, leading to increase Heart Rate (Tachycardia). This is often the fastest response.

↑ Sympathetic Outflow:

Heart: Increases heart rate and contractility (via β₁-receptors), boosting Stroke Volume and Cardiac Output.

Blood Vessels: Causes widespread vasoconstriction in arterioles (increasing Systemic Vascular Resistance) and veins (increasing Venous Return and Preload).

Net Effect: ↑ Heart Rate, ↑ Contractility, ↑ Venous Return, ↑ Systemic Vascular Resistance → ↑ Cardiac Output & ↑ Arterial Pressure back toward normal.

Summary Diagram of the Reflex Arc

Change in BP | Baroreceptor Firing | Parasympathetic Outflow | Sympathetic Outflow | Final Effect on BP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

↑ Pressure | Increases | Increases (↓ HR) | Decreases (Vasodilation, ↓ Contractility) | Decreases (Corrective) |