Developmental yr 2

1/130

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

131 Terms

define intersubjectivity

interactions between baby and mother - can be primary or secondary

Phonology

combining small units to create language

semantics

language conveying meaning

syntax

linguistic rules about how words go together

i.e.:

a bites the dog man

the dog bites a man

the man bites a dog

primary intersubjectivity

first few months of baby’s life

characterised by eye contact, attention to faces, vocalisations, imitating sounds and gestures

secondary intersubjectivity

older infants - 9 months

more sophisticated, intentional, interactions

pointing, turn taking, shared attention, social referencing

define dyadic interactions

interaction focussed on the baby and mother (as opposed to the environment)

primary intersubjectivity - dyadic mimicry study

Meltzoff and Moore 1997

newborns mimic facial expressions

3-4 month olds mimic sounds

show no understanding of others’ intentions

shows infants have a motivation to interact with others

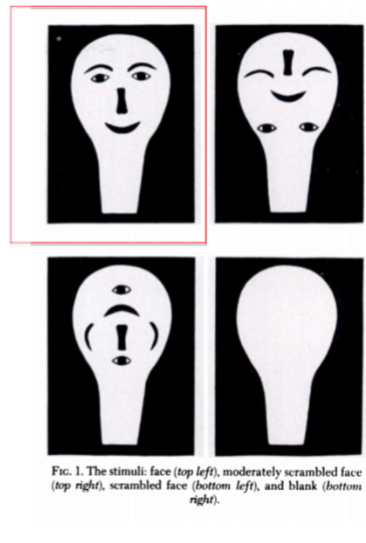

primary intersubjectivity - preference for faces study

Goren et al 1975

infants show a preference for face-like objects

spoon-like figures presented

primary intersubjectivity - attention to faces and eye gaze

newborns prefer to make direct eye contact

Senju and Csibra 2008:

infants will only follow someone’s gaze if they make direct eye contact first

define triadic interactions

interaction that involve mother, baby and now something in the environment i.e. a toy

secondary intersubjectivity - still face experiment

shows how infants coordinate their emotional responses with others, and what happens when that coordination breaks down:

parent freezes their responses to infant - indicating something is wrong

interaction breaks down

baby attempts to repair interaction through social engagement cues

secondary intersubjectivity - visual cliff experiment

shows how infants use social referencing

infants look to parents for emotional cues to see how to proceed

positive cues increase likelihood the child will walk over the cliff

demonstrates transfer of information and shared attention skills

secondary intersubjectivity - intentional communication begins

this is signified by:

eye contact and pointing

consistent vocalisations to indicate a specific goal

evidence of waiting for a response

persistence if not initially understood

what are the two key modes of communication important for language acquisition

Turn-taking

Joint attention

Sharing a focus of attention

Following attention

Directing attention

turn taking

3 months - infants begin to alternate vocalisations with caregiver

12 months - few overlaps between speakers

what is a proto-conversation

a type of early turn taking vocalisations that are similar to later conversation

joint attention

sharing a focus of attention

joint interactions are triadic

there is shared awareness of the shared attention (both know they are both attending to the object)

joint attention skills predict later language skills

discuss the importance of routines

routines create shared context - so children can know what will come next

routines create scaffolding for language learning

joint attention

following attention timeframes

9 months - can follow someone’s point

12 months - begins to check back with the pointer

14 months - can follow a point across a line of sight

gaze following

a form of joint attention, as we track where someone else is looking and join them in looking

9 months - infants will follow an adult’s gaze and share an object of attention - Scaife and Bruner

studies on gaze following

Brooks and Meltzoff:

found at 12 months, infants will follow a head turn even if the turner is blindfolded (indicating they aren’t following gaze specifically)

however, 12 month olds won’t follow a gaze if the eyes are visible but closed

14 months - only follow when the eyes are visible (suggesting they are now following gaze)

what did moll and tomasello discover about infants and gaze following

infants will follow a gaze behind barriers

joint attention

directing attention - imperative and declarative pointing

imperative pointing = to get an adult to do something - infant learns this gets them what they want

declarative pointing = to direct an adult’s attention to something - infant learns this gets them attention

timeframes for directing attention

9 months - child points to an object and checks the mother is watching

18 months - child check the mother is watching before pointing

directing attention - criticising evidence

at 12 months (so not 18 as other evidence suggests):

infants can indicate when adults find the wrong object - Liszkowski

infants respond negatively when adults attend to them and not the object - Boundy et al

the mapping problem - Quine

it is difficult to know which words link to which meanings because often there is lots of solutions the evidence could point towards

specific reference to pointing at things and naming them

under extension

using a term too narrowly i.e. only using dog for family pet, not all dogs

over extension

using a term too broadly i.e. calling all 4 leg animals a dog

error made until 2.5 yrs old

why do over extensions happen

category error - they have placed an item i.e. lion into the wrong category of dog

vocabulary limitations - they lack the word for lion so choose a close enough word they do know

give dates for language comprehension

comprehension comes before production

6 months - can comprehend nouns

10 months - can comprehend verbs

10-24 months - improvements on looking-while-listening tasks

18 months - don’t need the full word to know which object to look at

give dates for language production

12 months - first word

24-30 months - 500 words

what does it mean to say first words are often isolated

they lack articles like a and the

what is early noun bias

first words are often nouns

natural partitions hypothesis

children learn the words for objects (nouns) easier than verbs or prepositions because objects are physical and more visible

it is harder to give a label to a more abstract concept

name 3 mechanisms for word learning

innate constraints

structural cues in language

the social-pragmatic approach

innate constraints on early word learning

how children know what a word refers to

object constraint

whole-object constraints

principle of contrast

mutual exclusivity

object constraint

assumes a word relates to an object

whole-object constraints

assumes a word relates to a whole object, not its parts

principle of contrast

no two words can have the exact same meaning

explains how children overcome over extension

mutual exclusivity

no object has more than one name

helps overcome the whole-object constraint as they learn that new labels must mean new parts

issues with constraint theories

it just describes learning happens as opposed to explaining it

limited research on infants - so we don’t know if constraints are innate or learned

structural cues in language

structural cues for nouns are learned early and later for other words

structural cues for adjectives are learned at 18 months and beyond

syntactic bootstrapping hypothesis - structural cues

we rarely hear words in isolation

so we use this syntactic context to help give meanings to words

what did Waxman and Booth’s blicket study find regarding structural cues

children can extend nouns to category but not property.

children don’t extend adjectives to either category or property (showing they understand it isn’t a noun)

what did Gelman and Markman’s study show regarding structural cues

nouns refer to objects and categories, adjectives refer to properties (the differing ways they are used in sentences can indicate what kind of word it is)

how do structural cues relate to verbs

they are used to narrow down verb meanings

issues with using structural cues to narrow down word meanings

we know children are sensitive to word structure - but we don’t know exactly what aspects or at what age

we need some knowledge of words and their categories to understand structure, so how can structure teach us about word categories

experimental studies might just be showing us short term problem solving, not long term word learning

explain tomasello’s social-pragmatic approach

children use pragmatic clues from the environment to learn words

learning words is constrained in two ways:

the social world is structured - we have routines and patterned interactions

social-cognitive skills the infant has - whether they engage in joint attention, or intention reading

explain social cognitive skills further + brooks and meltzoff

word learning occurs when infants try to interpret the utterances from others

eye gaze and joint attention help with this process

gaze following at 10 months predicts language skills at 18 months - brooks and meltzoff

explain intention reading within the social-pragmatic approach

infants use the intentions of the speaker to work out the meaning of words

children can anticipate actions and then associate words with those actions

they can also differentiate between intentional and accidental actions

issues with the social pragmatic approach

it doesn’t account for how children learn more abstract words that don’t correlate to objects or actions

it is unclear when different aspects of this theory are used at which stages of development

what is syntax

the way different languages allow words to be combined into sentences

what are the characteristics of early word combinations

mainly content words

conveys most important parts of a sentence

present tense

observes adult word order i.e. truck gone not gone truck - suggesting there are some organising principles known at this stage

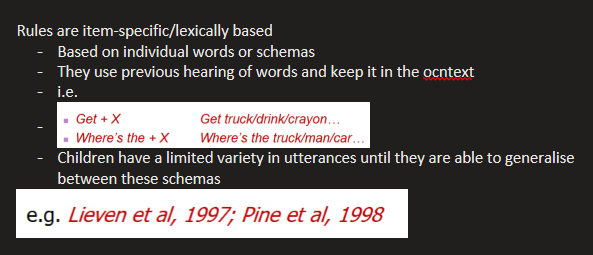

lexical (word based) rules

syntactic rules

grammatical rules

rules are innate

the constructivist/usage based approach

grammar is used for communication

infants are motivated to learn to communicate

grammar is learned using the following mechanisms:

intention reading

drawing analogies - similarities between groups of words and types of sentences and their functions

distributional learning - bits of language we always hear together

what role does routine play in learning language

it allows children to predict what happens next and deduct what the language they are hearing might refer to

evidence for the constructivist approach

high frequency items (heard the most) are learned easily - supporting routine

the verb island hypothesis:

children are generally unable to generalise between verbs with similar meanings or used in similar sentence types

NOT FULL INFO UNSURE

what 3 ways do children build up their lexically-based constructions to be more adult

structure combining

semantic analogy

distributional learning

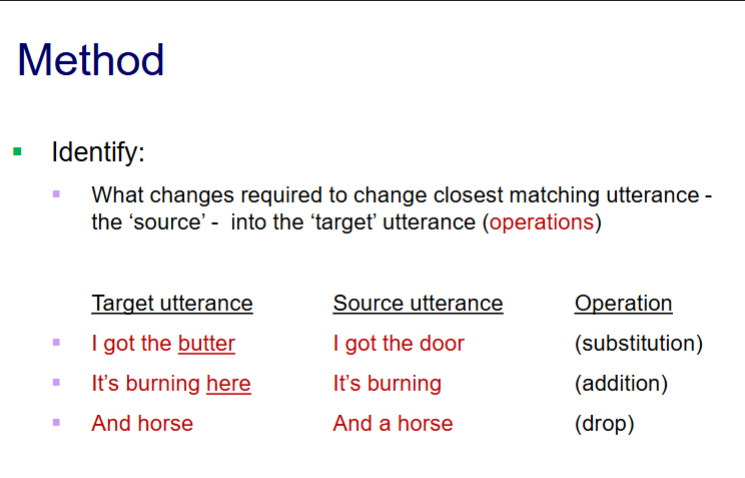

outline structure combining - Lieven et al

explains how children’s utterances build on what they have previously said

children identify what changes (operation) is required to go from the source (previous) utterance to the target (current) utterance

the study found many utterances are based on small changes and repetitions of previous utterances

common operations are substitutions, additions, or drops

outline semantic analogy

ALSO NOT SURE ARGHHHHH

outline distributional learning

noticing patterns between words that often appear together

i.e. verbs usually end in ‘ing’ or ‘ed’, nouns normally end in ‘s’

what is phonology

language is made of combined small units

what is semantics

language conveys meaning

what types of studies are used to asses infant language

preference studies - no training, what do they want to listen or look at

habituation studies - infants are trained, then we see what they prefer

change detection studies - infants are trained to respond to a change (measures whether they can tell a difference between two things)

prosody

patterns of stress and pitch in a language and how this can change the meaning of the same sentence

phonemes

smallest units of distinct sound in a language

evidence that infants have prosody

Mampe et al found that infants cry with an accent - they have different pitches at different points in the cry

Nazzi et al found infants can distinguish between languages with different prosody i.e. german and spanish but not languages with similar prosody i.e. english and dutch

what age can infants discriminate between all sounds and what age does this change

1-2 months - this includes foreign ones, which adult’s can’t even do

7-11 months this declines for other languages and increases for the target language

what can infants do regarding word syllables

they can track syllables that often co-occur and know that these syllables are likely to be part of the same word

i.e. hap - ppy, or pre - tty

what did saffran et al investigate

infants listening to syllables in a made up language of whole words and part words (where two syllables that aren’t usually together have been mashed)

infants listened longer to the part words indicating novelty

infant directed speech - christa 2013

higher pitched

slower speaking rate

important words are usually exaggerated and at the end

boundaries between phrases are exaggerated and so easier to separate

infants prefer people who use IDS

what is the use of having high frequency salient (important)/linguistic words

salient - mummy/your name

linguistic - he, she, the

it acts as an anchor - giving at least one boundary between words in a speech stream and helping them segment the speech

what age do infants use articles to segment nouns

8 months

specific article is ‘the’

explain how different infants learn their own language rules

at 8 months, infants are sensitive to the structures of sentences used in their language i.e. italian is frequent-first, and japanese is frequent-final

firugemu vs rugemufi

constructivist argument to child acquisition of language

children actively engage in their environment to construct their knowledge

nativist vs constructivist views on creative utterances

nativist = children’s utterances are creative because they have access to innate grammatical rules

constructivist = children’s utterances are creative because they use lexical frames from language they have already heard and insert new variables into the slots

nativist vs constructivist views on observing adult word order

nativist = children observe adult word order because they use their innate rules to put words into the same order as adults

constructivist = children observe adult word order because they pick up on frequently used terms and structures

nativist vs constructivist views on generalisations

nativist - generalisations provide evidence of their innate rules

constructivist - generalisations demonstrate that they learn language gradually from their environment

state and explain 3 nativist assumptions

grammar is like algebra - it is a computational system

grammatical categories and rules are present since birth (universal grammar)

learning particular aspects of grammar is all or nothing - once you know one rule you can apply it to everything

Radford’s general nativist predictions

children learn these innate aspects of grammar early on

children show consistent use of the same rules

universal grammar

all rules for language are innate and apply to all languages

when rules do differ between languages, they are highly constrained by parameters

children learn which parameters apply to the language they are learning at the time

english vs japanese language parameters

object comes after the verb:

i eat sashimi

vs japanese when the object comes before the verb:

i sashimi eat

theoretical advantages of universal grammar

avoids the issue of explaining how children acquire complex grammatical rules

explains unified acquisition of language across languages (while also explaining how they differ)

evidence to support universal grammar

some studies show children understand the rule of word order (verb-object vs object-word) from 2 yrs old - with preferential studies suggesting even earlier

preferential studies supporting universal grammar

children aged 1

they can identify the correct monkey and frog picture that represents the sentence ‘the monkey is gorping the frog’.

shows they understand word order parameters

theoretical issues for universal grammar

bilingualism - if children learn the correct parameters for the language they are learning, how can they apply different parameters for different languages

the concept of parameters is vague - we don’t know how many there are of what they are

studies against universal grammar parameters

chan et al

children show limited knowledge of subject - verb - object word order in production and act out tasks

what is the maturation model main theory

children’s language develops over time - so they don’t start out with innate universal grammar

explain Radford’s maturation model

at 20 months (lexical stage), children’s words consist of content words only (nouns, verbs, adjectives)

at 24 months (functional stage), their innate grammar matures and parts that control more complex grammar switch on

what complex grammatical components switch on

auxiliary verbs - mark certainty i.e. will, might

determiners - distinguish definites and indefinites i.e. a, the

inflections - mark tense and agreement i.e. watch/watched, i watch/he watches

lexical vs functional utterances

lexical = content heavy i.e. mummy doing? hands dirty

functional = adding in grammatical glue to content words

theoretical advantages of maturational models

explains why early utterances aren’t fully grammatical

fits more empirical data that suggests language develops over time

theoretical and empirical issues with maturational models

it is hard to identify exactly when in development maturation switches on

in early stages of development, children’s use of grammatical functions is inconsistent and varies across languages - not universal

what is the linking problem

how do children link their innate knowledge of grammatical categories with the words they hear (because we don’t label words as nouns/verbs etc when we say them)

semantic bootstrapping

a proposed solution for the linking problem

children have innate linking rules that they use to map the words they hear into the correct categories as and when they hear them

explain what agent and patient are

agent = the person carrying out the action, the subject of the sentence

patient = the person/thing affected by the action, the object of the sentence