BIS 101 Final HW Answers

1/48

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

49 Terms

Define these three gene expression phenotypes: inducible, constitutive, uninducible. Use the lac operon as an example.

Gene expression is said to be inducible when it is expressed only when it is needed (when a specific metabolite acting as an inducer is present), and otherwise it is not expressed.

In the case of the lac operon, this is the wild-type phenotype (when glucose is absent), where structural genes are transcribed when lactose is present, but not when lactose is absent.

A constitutive gene expression phenotype is when the gene is expressed continually regardless of growth conditions.

In the case of the lac operon, this is a mutant phenotype, where structural genes are transcribed whether or not lactose is present.

An uninducible gene expression phenotype is a mutant phenotype of an inducible gene, where the gene is not expressed under any conditions (whether the inducer is there or not).

In the case of the lac operon, this is a mutant phenotype, where there is no expression of structural genes, whether or not lactose is present.

In the lactose operon of E. coli, what is the function of each of the following genes or sites: (a) regulator, (b) operator, (c) promoter, (d) structural gene Z, and (e) structural gene Y?

regulator

encodes the repressor

operator

binding site of repressor

promoter complex

binding site of RNA polymerase and CAP-cAMP

structural gene Z

encodes B-galactosidase

structural gene Y

encodes permease

What would be the result of inactivation by mutation of the following genes or sites in the E. coli lactose operon: (a) regulator, (b) operator, (c) promoter, (d) structural gene Z, and (e) structural gene Y?

regulator

constitutive

operator

constitutive

promoter

uninducible

structural gene Z

no B-galactosidase activity

structural gene Y

no permease activity

Groups of alleles associated with the lactose operon are as follows (in order of dominance for each allelic series): repressor, I s (superrepressor), I + (inducible), and I c (constitutive); operator, Oc (constitutive, cis-dominant) and O+ (inducible, cis-dominant); structural, Z+ and Y+ .

(a) Which of the following genotypes will produce b-galactosidase and permease if lactose is present: (1) I+O+Z+Y+, (2) I−OcZ+Y+, (3) IsOcZ+Y+, (4) IsO+Z+Y+, and (5) I−O+Z+Y+ ?

(b) Which of the above genotypes will produce b-galactosidase and permease if lactose is absent? Why?

(a) 1, 2, 3, and 5

Genotype 1 is wild type and inducible, whereas genotypes 2, 3, and 5 are constitutive; all except 4 will produce b-galactosidase and b-galactoside permease in the presence of lactose. However, genotype 4 has a superrepressor mutation (I s ) and is uninducible.

(b) 2, 3, and 5

In genotypes, 2 and 3, the repressor cannot bind to Oc and in genotype 5, no repressor is made; both situations render the operon constituitve.

Assume that you have discovered a new strain of E. coli that has a mutation in the lac operator region that causes the wild-type repressor protein to bind irreversibly to the operator. You have named this operator mutant Osb for “superbinding” operator.

(a) What phenotype would a partial diploid of genotype I + OsbZ− Y+ /I+ O+ Z+ Y− have with respect to the synthesis of the enzymes b-galactosidase and b-galactoside permease?

(b) Does your new Osb mutation exhibit cis or trans dominance in its effects on the regulation of the lac operon?

(a) b-Galactosidase will be produced only when lactose is present. Permease will not be produced at all.

(b) cis dominance.

For each of the following partial diploids indicate whether enzyme synthesis is constitutive or inducible (see Problem 18.5 for dominance relationships):

(a) I+O+Z+Y+/I+O+Z+Y+

(b) I+O+Z+Y+/I+OcZ+Y+

(c) I+OcZ+Y+/I+OcZ+Y+

(d) I+O+Z+Y+/I−O+Z+Y+

(e) I−O+Z+Y+/I−O+Z+Y+

(a) Inducible, this is the wild-type genotype and phenotype.

(b) Constitutive, the Oc mutation produces an operator that is not recognized by the lac repressor.

(c) Constitutive, same as for (b).

(d) Inducible, I + is dominant to I - .

(e) Constitutive, no active repressor is synthesized in this bacterium.

Write the partial diploid genotype for a strain that will (a) produce bgalactosidase constitutively and permease inducibly and (b) produce b-galactosidase constitutively but not permease either constitutively or inducibly, even though a Y+ gene is known to be present.

(a) I + Oc Z+ Y- /I + O+ Z+ Y+

(b) I + Oc Z+ Y- /I s O+ Z+ Y+

As a genetics historian, you are repeating some of the classic experiments conducted by Jacob and Monod with the lactose operon in E. coli. You use an F plasmid to construct several E. coli strains that are partially diploid for the lac operon. You construct strains with the following genotypes:

(1) I+OcZ+Y−/I+O+Z−Y+, (2) I+OcZ−Y+/ I+O+Z+Y−, (3) I−O+Z+Y+/I+O+Z−Y−, (4) IsO+Z−Y−/ I+O+Z+Y+, and (5) I+OcZ+Y+/IsO+Z−Y+.

(a) Which of these strains will produce functional b-galactosidase in both the presence and absence of lactose?

(b) Which of these strains will exhibit constitutive synthesis of functional b-galactoside permease?

(c) Which of these strains will express both gene Z and gene Y constitutively and will produce functional products (b-galactosidase and bgalactoside permease) of both genes?

(d) Which of these strains will show cis dominance of lac operon regulatory elements?

(e) Which of these strains will exhibit trans dominance of lac operon regulatory elements?

(a) 1, 5.

(b) 2, 5.

(c) 5.

(d) 1, 2, 5.

(e) 3, 4

Is the CAP–cAMP effect on the transcription of the lac operon an example of positive or negative regulation? Why?

Positive regulation

the CAP-cAMP complex has a positive effect on the expression of the lac operon. It functions in turning on the transcription of the structural genes in the operon.

Would it be possible to isolate E. coli mutants in which the transcription of the lac operon is not sensitive to catabolite repression? If so, in what genes might the mutations be located?

Yes

in the gene encoding CAP. Some mutations in this gene might result in a CAP that binds to the promoter in the absence of cAMP. Also, mutations in the gene (or genes) coding for the protein (or proteins) that regulate the cAMP level as a function of glucose concentration.

How can cis and trans-acting regulatory elements be distinguished?

They can be distinguished by constructing partial diploids in which the regulatory elements are positioned (1) cis to the regulated genes and (2) trans to the regulated genes. A cis-acting element will only influence the expression of the genes present in the cis configuration (on the same chromosome), whereas a trans-acting element will exert its effect in either the cis or trans configuration (will have an effect on both chromosomes in a diploid or partial diploid).

How would you distinguish between an enhancer and a promoter?

enhancer

can be located upstream, downstream, or within a gene and it functions independently of its orientation

promoter

is almost always immediately upstream of a gene and it functions only in one direction with respect to the gene

Tropomyosins are proteins that mediate the interaction of actin and troponin, two proteins involved in muscle contractions. In higher animals, tropomyosins exist as a family of closely related proteins that share some amino acid sequences but differ in others. Explain how these proteins could be created from the transcript of a single gene.

By alternate splicing of the transcript.

A particular transcription factor binds to enhancers in 40 different genes. Predict the phenotype of individuals homozygous for a frameshift mutation in the coding sequence of the gene that specifies this transcription factor.

The mutation is likely to be lethal in homozygous condition because the transcription factor controls so many different genes and a frameshift mutation in the coding sequence will almost certainly destroy the transcription factor’s function.

The RNA from the Drosophila Sex-lethal (Sxl) gene is alternately spliced. In males, the sequence of the mRNA derived from the primary transcript contains all eight exons of the Sxl gene. In females, the mRNA contains only seven of the exons because during splicing exon 3 is removed from the primary transcript along with its flanking introns. The coding region in the female’s mRNA is therefore shorter than it is in the male’s mRNA. However, the protein encoded by the female’s mRNA is longer than the one encoded by the male’s mRNA. How might you explain this paradox?

Exon 3 contains an in-frame stop codon. Thus, the protein translated from the Sxl mRNA in males will be shorter than the protein translated from the shorter Sxl mRNA in females.

What is the effect of chromatin state on gene expression? What effect does

a) chromatin remodeling,

b) histone modification (will go over in lecture- your book doesn’t call it this, but this is what it is referring to when it discusses modifications of amino acids on histones by HATs and Kinases, first full paragraph of p.547 in 6th ed., p.500 in 7th ed.), and

c) DNA methylation have on transcription?

Generally, more open chromatin is associated with higher rates of transcription, whereas more closed or condensed chromatin is associated with lower or no transcription. Chromatin is made up of nucleosomes, and nucleosomes are made up of DNA wrapped around histone proteins (8 histone proteins, 2 each of H2a, H2b, H3, and H4). All of these mechanisms affecting chromatin state (or whatever DNA methylation is doing—we don’t entirely understand yet!) described below are epigenetic, they affect transcription without changing the DNA sequence.

a) Chromatin remodeling

slide or move nucleosomes (DNA wound around complex of histone proteins) out of the way

replace stable histones with unstable histones

b) Histone modifications

change the histone tail to alter chromatin state by adding chemical groups

opening = increasing transcription

closing = repressing transcription

c) Chemical modification

Methyl groups can be added to cytosines found next to guanines (on the same strand, see your book for the structure).

added to histones only

Methylated DNA is associated with transcriptional repression

What factors affect RNA stability? What effect is the stability of mRNA likely to have on protein levels?

RNA stability affects the number of mRNA molecules available for translation at any one time. The stability of an RNA molecule can be affected by the Poly(A) tail, destabilizing sequence elements often found in the region upstream of the Poly(A)tail (in the 3’ untranslated region [3’ UTR]), chemical factors such as hormones, and the presence of targeted miRNAs or siRNAs. mRNA transcripts can be translated as long as they are intact, so longer-lived mRNAs have the potential to produce more proteins.

Summarize the RNAi pathway, as pictured in lecture (or Figure 19.8 in the book). What goes into this pathway (what is the starting material), and what is the result? How does RNAi ultimately affect phenotypes?

Process

double stranded piece of RNA is cut by an enzyme to be short

loaded onto a protein complex called RISC

one of the two strands is cut away to leave RISC with a small single stranded piece of RNA

RISC goes around with its small single stranded piece of RNA and looks for mRNA to bind to through complementary base pairing

when it finds mRNA to bind to, it destroys that mRNA (or makes it so it can’t be translated)

input

double-stranded RNAs that are complementary to sequences within target mRNAs

result

less or no mRNA for particular gene = less/no protein can be made from that gene

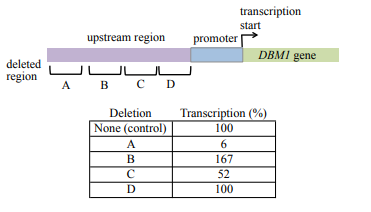

The consequences of four deletions from the region upstream of the yeast gene DBM1 are studied to determine the effect on transcription. The normal rate of transcription, determined from study of transcription of genes that do not have upstream deletions, is defined as 100%. The location of each deletion and the effects of deletions on DBM1 transcription are shown below:

a) Which mutation(s) affect an enhancer sequence? Explain your reasoning.

b) Which mutations(s) affect a silencer sequence? Explain your reasoning.

c) Which mutation(s) have no effect on gene expression? Explain your reasoning.

(a) Enhancers are sequences located at a distance from the promoter, and they increase transcription of a gene above its basal level.

Mutation of an enhancer will reduce transcription levels.

Mutants A and C both reduce expression levels; therefore they are both likely to be enhancer sequences

(b) Silencers are sequences located at a distance from the promoter, and they decrease transcription of a gene.

Deletion of a silencer will increase transcription over that observed in wild type.

Mutant B has the only mutation that increases expression over wild-type levels.

Mutant B affects a silencer sequence. This deletion results in a substantial increase in the level of transcription.

(c) Mutation D does not have an effect on expression levels, as the level of transcription remains 100% with this mutation.

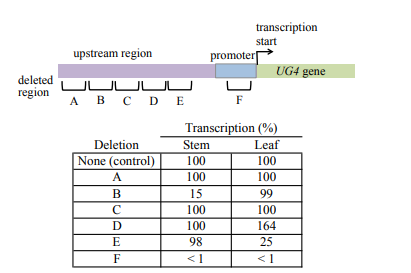

The UG4 gene is expressed in stem tissue and leaf tissue in Arabidopsis thaliana. To study mechanism regulating UG4 expression, six small deletions of DNA sequence upstream of the transcription start site are made. The locations of the deletions and their effect on UG4 expression are shown below:

a) Why does deletion B lower expression of UG4 in stem tissue but not leaf tissue?

b) Why does deletion D raise UG4 expression in leaf tissue but not in stem tissue?

c) What can you deduce about the sequence contained in F?

(a) Mutation B eliminates a region relatively far away from the transcription start site and severely reduces expression in stems but has no effect in leaves.

Mutations in regions at a distance from the transcription start site that prevent expression typically affect an enhancer; therefore, mutation B deletes a required enhancer sequence for UG4 transcription in stem tissue but not in leaf tissue.

(b) Mutation D results in greater than wild-type level expression in leaves but not stems.

Mutations that increase expression typically remove silencers; therefore, mutant D lacks a silencer sequence that regulates the level of transcription of UG4 in leaf tissue but not in stem.

(c) Mutation F, located in the promoter, next to the transcription start site, results in virtually no transcription in either stem or leaf.

The promoter sequences deleted by mutation F are required for transcription in both leaf and stem.

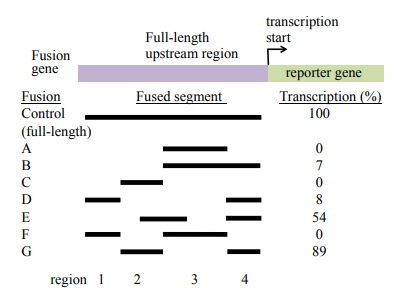

A gene expressed in the long muscle of the mouse is identified, and the regulatory region upstream of the gene is isolated. Various segments of the upstream sequence are fused to a reporter gene, and each fusion is assayed to determine how efficiently it transcribes the gene. In the following diagram, the dark bars indicate the upstream segments that are present in each of 8 fusion genes. The transcriptional efficiency of each fusion is measured compared to the control, which is the full-length upstream region fused to the reporter gene.

a) Identify the upstream region (region 1, 2, 3, 4 indicated along the bottom of the diagram) that contains the promoter

b) Identify the upstream region that contains the enhance

c) Speculate about the reasons for the different transcription rates detected in fusions E and G.

(a) All fusions that contain region 4 have some expression, and this region is closest to the transcription start, so this region is a likely candidate to contain the promoter. However, this region is not sufficient for high levels of transcription. In fusions B and D, region 4 is included, but the additional inclusions of regions 3 (fusion B) or region 1 (fusion D) are not sufficient for very high levels of transcription.

(b) For the enhancer, we are looking for another region that is necessary for high levels of transcription. We observe higher levels of expression in the fusions that also contain part of region 2 in addition to region 4 (which we have determined contains the promoter), so it is likely that region 2 contains the enhancer.

(c) Fusion E contains most but not all of region 2 in addition to region 4, whereas fusion G contains all of region 2 and region 4. It is likely that the part of region 2 that fusion E does not have is responsible for some of the function of the enhancer located in this region. The other alternative is that the position of the enhancer sequences in region 2 might be better located in fusion G relative to the promoter, though we can’t really tell that from this drawing.

Like dorsal, bicoid is a strict maternal-effect gene in Drosophila; that is, it has no zygotic expression. Recessive mutations in bicoid (bcd) cause embryonic death by preventing the formation of anterior structures. Predict the phenotypes of

(a) bcd/bcd animals produced by mating heterozygous males and females;

(b) bcd/bcd animals produced by mating bcd/bcd females with bcd/+ males;

(c) bcd/+ animals produced by mating bcd/bcd females with bcd/+ males;

(d) bcd/bcd animals produced by mating bcd/+ females with bcd/bcd males;

(e) bcd/+ animals produced by mating bcd/+ females with bcd/bcd males.

(a) Wild-type; (b) embryonic lethal; (c) embryonic lethal; (d) wild-type; (e) wild-type.

In Drosophila, recessive mutations in the dorsal-ventral axis gene dorsal (dl) cause a dorsalized phenotype in embryos produced by dl/dl mothers; that is, no ventral structures develop. Predict the phenotype of embryos produced by females homozygous for a recessive mutation in the anterior-posterior axis gene nanos, which is critical to posterior development.

Some structures fail to develop in the posterior portion of the embryo

What events lead to a high concentration of hunchback protein in the anterior of Drosophila embryos?

The hunchback mRNA is translated into protein only in the anterior region of the developing embryo. This RNA is supplied to the egg by the mother during oogenesis and it is also synthesized after fertilization by transcription of the hunchback gene by the zygote. This zygotic transcription is stimulated by a transcription factor encoded by maternally supplied bicoid mRNA, which is located in the anterior of the egg. Thus, hunchback mRNA is concentrated in the anterior of the embryo. In addition, the hunchback mRNA that is located in the posterior of the embryo is bound by nanos protein, and then degraded. The nanos protein is concentrated in the posterior of the embryo because maternally supplied nanos mRNA is preferentially localized there.

What is a morphogen? How does Bicoid (also discussed in the book) fit the definition of a morphogen?

A morphogen is a substance that can control developmental fates in a concentration-dependent manner (i.e. different concentrations determine different fates). For this reason, morphogens are usually distributed in gradients. Bicoid is a critical determinant of anterior (head) structures in embryogenesis. In oogenesis, bicoid mRNA is deposited at the anterior end of the oocyte. As embryonic development begins, bicoid mRNA diffuses from the anterior end outward, and it is translated into a gradient of Bicoid protein as this diffusion occurs, with high concentrations at the anterior of the embryo, and lower concentrations toward the posterior. Bicoid acts as a transcription factor to control gene expression of later expressed genes, such as gap or pair-rule genes, and it does so in a concentration dependent manner. In areas where Bicoid concentration is high, in the anterior of the embryo, it will be able to act strongly to regulate transcription of later genes. Bicoid activates different downstream genes in parts of the embryo where Bicoid concentrations differ.

Given that maternal Bicoid activates the expression of hunchback, what would be the phenotypic consequence of adding extra copies of the bicoid gene to the mother, thus creating a female fly with three or four copies of the bicoid gene (compared to two in the wild-type)? Hint: this was covered in lecture. How would hunchback expression be altered? What about the expression of later gap and pair-rule genes?

Increased dosage of the bicoid gene will result in an increase in the amount of bicoid mRNA and therefore Bicoid protein. This increase would alter the gradient of Bicoid protein in the egg and, in turn, alter the expression of genes downstream of Bicoid function. For example, hunchback is activated by Bicoid, so hunchback expression also increases and the zone of expression is pushed further posterior in a fly with a higher Bicoid gene dosage. The entire body plan of the mutant flies would likely be altered, resulting in more anteriorlike segment fates being adopted by what would normally be more posterior-like segments (i.e. a larger head!).

Describe the mutant phenotypes of maternal gene, gap gene, pair-rule gene, and segment-polarity gene mutants.

Mutations in the gap genes cause multiple body segments next to one another to be missing, this causes large “gaps” in the segment anatomy. Mutations in pair-rule genes produce larvae with every other segment missing, resulting mutants to have half the number of segments they should have. Mutations in segment-polarity genes result in defects in each of the 14 segments.

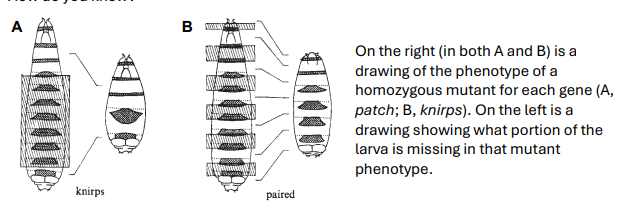

Below are two schematic drawings of mutant phenotypes from the 1980 paper by Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus (Nature, Vol. 287), where they characterized gap, pairrule, and segment polarity genes. Which of these genes acts earlier in development? Hint: look to your answer of the previous question, as well as the structure of the gene network. How do you know?

The gene on the left, knirps, acts earlier in development. From the mutant phenotypes, knirps is a gap gene, and paired is a pair-rule gene, and gap genes act earlier in development than do the pair-rule genes. The mutant phenotype of knirps affects a large number of contiguous segments (segments next to one another), so it must act before all of the individual segments are specified. The other mutant phenotype, from the paired mutant, affects every other segment, so it must act later, at the stage when the segments are being specified.

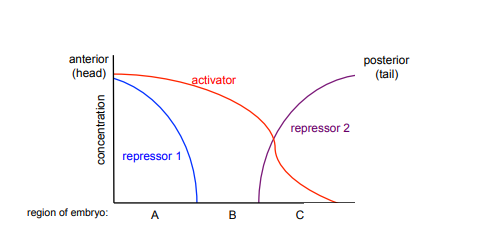

The figure below represents the concentrations of activator and repressor transcription factors along the anterior-posterior (head to tail) axis in an embryo.

A) In which region of the embryo, A, B, or C, will the gene regulated by these transcription factors be expressed? Why?

B) In which regions of the embryo would the gene regulated by this transcription factor be expressed in a repressor 1 mutant (with no repressor 1 function)? Why?

A) The gene regulated by these transcription factors would be expressed only in Region B of the embryo. It would not be expressed in region A or region C because there are high concentrations of repressors present in these regions. Region B has an activator present and no repressors present.

B) In a repressor 1 mutant, the gene regulated by these transcription factors could be expressed in either region A or region B, where there would be activator present but no repressor. The gene would still not be expressed in region C due to the presence of a repressor in this region.

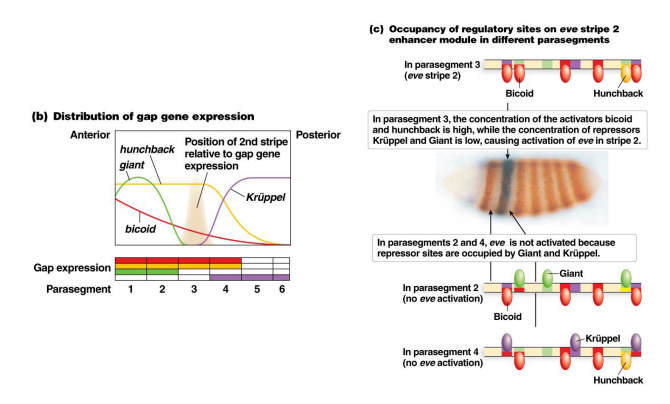

Using the figure below, showing how the expression of the pair-rule gene eve stripe 2 is established by the coordinated activities of maternal and gap genes, answer the following questions. NOTE: Remember in lecture when it was mentioned that sometimes the same sequence can work both as an enhancer (to promote gene expression) and a silencer (to repress gene expression)? This is one of those cases. This cis-regulatory region is called an “enhancer module” here, but it can bind both activator and repressor transcription factors. Bicoid and Hunchback are activators of eve stripe 2, Giant and Kruppel are repressors. Parasegment is a term used to describe the 14 segments or zones of the embryo laid down in the segmentation process.

Note: You can do this problem only looking at part b of this figure. Part c is there to remind you what is actually happening here, that the concentrations of maternal/gap genes in a particular parasegment determine what can bind the enhancer in that region.

a) Is the DNA sequence of the enhancer module different between parasegments? Do the activators and repressors present at each parasegment vary? Why does the gene expression of eve stripe 2 produced by this enhancer module differ between parasegments?

b) Consider the binding sites for gap proteins and Bicoid in the stripe 2 enhancer module. What sites are occupied in parasegments 2, 3, and 4, and how does this result in expression or no expression?

c) Explain what you would expect to see happen to the expression pattern of eve stripe 2 in the parasegments if it is expressed in a Kruppel mutant background. What about a giant mutant background? What about a mutant background where both of the activators (hunchback and bicoid) are absent?

a) The DNA sequence is the same in all of the parasegments, with binding sites for the positive activators Hunchback and Bicoid and the negative regulators Giant and Krüppel. However, the activators and repressors present vary across the embryo, so there are different combinations of transcription factors present in different parasegments. The expression pattern produced by this enhancer differs depending on which combination of activators and repressors bind to the enhancer in each parasegment.

b) Giant, Hunchback, and Bicoid are bound to their sites in parasegement 2 (part C of the figure fails to show the Hunchback binding, this is an error, it clearly is present in parasegment 2 in part B of the figure); only Hunchback and Bicoid are bound to their sites in parasegment 3; and Krüppel, Hunchback, and Bicoid are all bound to their sites in parasegment 4. The binding of either Giant or Krüppel is sufficient to repress transcription; therefore, eve is transcribed only in parasegment 3.

c) In a Krüppel mutant, Hunchback and Bicoid are bound in parasegment 4 but Krüppel is not, resulting in expression of eve in both parasegments 3 and 4 (as there is now activator but no repressor in both parasegments 3 and 4 in a Krüppel mutant). In a giant mutant background, Hunchback and Bicoid are bound to their sites in parasegments 1, 2, and 3 but Giant would not be, resulting in eve expression in both parasegments 1, 2 and 3 (as there is activator present now but no repressor in Giant mutants in these parasegments). In mutants lacking both of the activators, Bicoid and Hunchback, eve expression would be reduced or abolished in parasegment 3. In this mutant, there would be no repressive factors bound at this locus, but without activators bound, expression would likely be reduced or abolished.

What is the function of homeotic genes (Hox genes are the homeotic genes we discussed in class)? What phenotypes do mutant homeotic genes produce?

Homeotic genes determine segmental identities, the anatomical features to be developed in each segment. For example, the second thoracic segment in flies has a pair of wings, while the third thoracic segment has a pair of halteres, small balancing structures that help the fly to fly. Hox genes are a category of homeotic genes we talked about in lecture, that contain homeobox DNA binding domains. Hox genes encode transcription factors, and the combinations of Hox genes expressed in each segment control developmental programs of gene expression resulting in the formation of the anatomical features of each segment. Hox genes are co-linear, that is they are expressed along the anterior-posterior axis in the same order as they are found on the chromosome. Homeotic genes are named for their mutant phenotypes. Homeotic mutants have one body part replaced by another body part, by transforming the identity of one segment into that of another segment. For examples, see the Antennapedia or Ubx mutant phenotypes (or the mouse Hox mutant) as described in lecture.

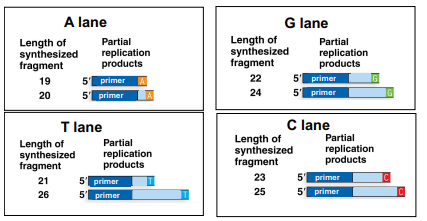

The following is an image of results from the different sequence reactions for Sanger sequencing, where only one ddNTP is added per lane (ddATP, ddTTP, ddCTP or ddGTP). This shows the different length fragments produced in each of the reactions:

(a) Use the results of these reactions (the fragment lengths and which lanes they are in) to determine the sequence of this region of the gene.

(b) Why did replication stop at 22 bases in the G lane?

(c) If the reaction stopped at 22 bases in the G lane, why is there also a fragment 24 bases long in the same lane?

a) 5’ AATGCGCT 3’

b) This lane has ddGTPs (the “special” G nucleotides), these nucleotides do not have a 3’ OH that the DNA polymerase can add more nucelotides on to. So when the ddGTP is added in replicating this fragment (based on a C being present in the template), then replication stops, leaving a fragment of a particular length. This tells you that there is a G at this position in your sequence.

c) Remember that there are many copies of the DNA being replicated in each reaction. In each reaction, there is one ddNTP, in this case ddGTP (the “special” nucleotide) along with all the “normal” nucleotides (dGTP, dCTP, dATP, dTTP). When replication occurs, some proportion of the time replication will add the “normal” G nucleotide (dGTP), in that case the reaction will not stop with that G, but will continue on until a “special” G nucleotide (ddGTP) is added. So in the case of the 24 base pair fragment in the G lane, the “normal” G was added at position 22, and the “special” G was added at position 24.

What is the role of DNA polymerases in Sanger sequencing and PCR?

Both Sanger sequencing and PCR make use of DNA polymerases to do replication.

Sanger sequencing

replication is used to determine the sequence of nucleotides in a segment of DNA you are sequencing. You supply the sequencing reaction with modified “special” nucleotides (ddNTPs) and “normal” nucleotides, when the “special” nucleotides are added to a growing DNA strand by DNA polymerase, then replication stops. This is because the “special” nucleotides (ddNTPs) lack a free 3’OH, so once they are added to a growing DNA strand, DNA polymerase is unable to add the next nucleotide to this strand. This produces fragments whose size you can determine, and based on which “special” nucleotide was added in a reaction (or the fluorescent label added to each “special” nucleotide), you can determine which nucleotide was in which position.

PCR

primers are supplied on either side of a region you wish to make lots of copies of, heat is used to separate the two DNA strands, and a heat-stable DNA polymerase replicates each strand. This is done over and over to make many copies of the piece of DNA.

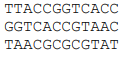

Assemble a sequence from the following sequencing reads:

TTACCGGTCACC

GGTCACCGTAAC

TAACGCGCGTAT

TTACCGGTCACCGTAACGCGCGTAT

Why does repetitive DNA pose problems for genome sequencing? There has been a major push to develop technologies that will sequence longer fragments. How could this help?

We sequence genomes by first breaking copies of the genome into many short fragments, and sequencing those fragments. It will be difficult to assemble our short fragments in repetitive regions of the genome, as our sequenced fragments may map to multiple locations in the genome. It can be difficult to determine how many copies of a repeated sequence are present. And it can be difficult to know the order of unique, nonrepetitive sequences relative to one another if they are flanked by repeats. Longer fragments can solve many of these problems. They are much less likely to map to multiple places, may span a significant proportion of the repeat region, and if long enough are more likely to contain unique non-repetitive sequences as well as repeats.

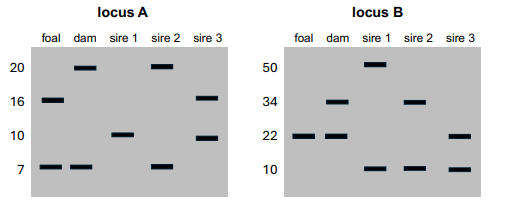

You are trying to determine the paternity of a foal (a baby horse). You genotype the foal, the dam (foal’s mom), and three potential sires (potential dads), using PCR at two different repetitive loci with variable repeat lengths. The results are as follows:

Could one or more of the potential sires be the sire of this foal? How do you know?

Sire 3. In both loci, we can figure out which allele must come from the sire. We can do this by ruling out the allele that comes from the dam. The band in common between the foal and the dam must come from the dam. For locus A, this is the allele with length 7. This means that the sire must have the foal’s other allele, the one with length 16. Sire 3 is the only potential sire with this allele. For locus B, the foal is homozygous for the allele at length 22, so the sire must have this allele as well. Again with this locus, sire 3 is the only potential sire with the allele at length 22.

Name 3 different approaches you could use to determine the genetic basis of a phenotype you are interested in

1. Make true breeding lines, do crosses, and look for Mendelian ratios. Like in monohybrid or dihybrid crosses from Mendelian genetics lecture

2. Perform a genetic screen: make/use mutant lines where every gene is knocked out, look for lines where your phenotype is affected, those genes likely contribute to your phenotype. Like the study where they identified genes involved in Drosophila segmentation (gap, pair-rule, segment polarity genes), see Developmental genetics lecture

3. Do a QTL (Quantitative Trait Locus) or GWAS (Genome wide association study), see Linkage and mapping/Complex traits lectures.

Marine (ocean dwelling) stickleback fish have pelvic spines, where their freshwater stickleback relatives lack pelvic spines. You do a QTL study on pelvic spines in these two populations, which identified the Pitx1 gene. To determine if Pitx1 is involved in pelvic spine development, you do the following experiments:

1. Knock out Pitx1 expression in the pelvic region of marine fish, and phenotype them for pelvic spines. You find that their pelvic spines are now absent

2. Express Pitx1 in the freshwater fish like it is expressed in the marine fish, by inserting the DNA region responsible for marine expression into the freshwater fish. When you do this, you see that it causes the freshwater fish to express the pelvic spine like the marine fish.

3. Visualize where Pitx1 is being expressed in the freshwater fish and the marine fish, find that it is only expressed in the region that will become the pelvic spine in the marine fish.

(a) Which of these experiments (1, 2, 3) is the find it experiment? Which is the lose it experiment? Which is the move it experiment?

(b) Are you convinced by the evidence provided by this experiment that expression of Pitx1 is responsible the difference in pelvic spines between marine and freshwater sticklebacks?

a) Experiment 3 is the find it experiment, experiment 1 is the lose it experiment, experiment 2 is the move it experiment. Experiment 3 shows you where and when your gene is expressed, so you can see if it’s expressed at the right time/place/conditions to be involved in your phenotype. Experiment 1 knocks out the protein, making it non-functional. Experiment 2 moves the expression of the gene from a population that has it at the right time and place to cause the phenotype, to another population where it is not normally present, to determine the effect of moving it.

b) I can’t answer for you if you are convinced, but this is a good opportunity to think about the kinds of evidence and what they show. The find it experiment establishes plausibility that this gene is involved in this phenotype. The lose it experiment shows this gene is necessary for producing this phenotype. And the move it experiment shows this gene is sufficient to produce this phenotype.

What do you need to do gene editing with CRISPR/Cas9, if you want to make a gene knockout or to insert a particular sequence? What happens once all those things are added to a cell? What is the role of DNA repair mechanisms in producing the desired gene editing outcome?

For CRISPR/Cas9, you need a guide RNA to direct the Cas9 enzyme where to cut, and the Cas9 enzyme to do the cutting. You need to design the guide RNA to be complimentary to (so it can bind to) your DNA sequence where you want it to cut. Depending on the system/version of the Cas protein, you may need to design your guide RNA to a region of the DNA where you want to cut where there is a PAM sequence (usually a GG). If you want to make a functional replacement (swap in a piece of DNA), you need to supply that sequence.

Once added to a cell, the guide RNA will bind to its target DNA sequence, and the Cas9 enzyme will produce a double strand cut in the DNA. If you want to make a knockout, you can let the cell repair the double-stranded break with NHEJ (non-homologous end joining), the high error mechanism for repairing double strand breaks. This is likely to produce enough mutations upon repair that the gene will be non-functional. If you want to make a functional replacement (add in a DNA sequence), you provide the cell with the desired sequence to be used as a template for homologous recombination repair. This means you design your repair template with regions of homology on the ends, and it can then be used by the cell to repair the double stranded break, which will copy your sequence into the genome at the site of the cut.

You sequence a 100kb region of the Bacillus anthracis genome (the bacteria that causes anthrax) and a 100kb region from the Gorilla gorilla genome. What differences or similarities might you expect to see in the annotation of the sequences, for example, in number of genes, gene structure, regulatory sequences, repetitive DNA?

The 100-kb Bacillus genome sequence will contain many more annotated genes than the 100-kb Gorilla sequence because prokaryotic genes are more compact, contain short regulatory sequences, do not have introns, and are packed tightly together; in contrast, eukaryotic genes are larger due to the presence of large introns, contain larger regulatory regions, and are separated by large intergenic DNA sequences. The Bacillus contain some operons and little repetitive DNA, whereas the Gorilla segment will lack operons and contain interspersed repetitive DNA.

General concepts: Bacterial genes are short and do not contain introns, some bacterial genes are organized in operons where multiple genes have shared regulatory sequences, the gene regulatory sequences are short, and the genes are closely packed together with little to no intergenic DNA. Bacterial genomes do not contain much repetitive DNA. Eukaryotic genes are large and consist often of short exons separated by large introns; there are no operons and the genes contain larger, complex regulatory regions. Eukaryotic genomes contain many interspersed, repetitive DNA elements.

Genome size does not correlate with organismal complexity. How does the existence of transposable elements and other sources of repetitive DNA help explain this observation?

Many eukaryotic organisms have genomes that are bloated with transposable elements (TEs), and other sources of repetitive DNA. The number of these repeats is the best prediction of genome size, large genomes are often due to large expansions of TEs.

Imagine that you sequence one organism with a 300 million basepair (Mb) genome and one with a 300 billion base pair (Gb) genome. If you generate one mutation at random in both of these genomes, in which species is it more likely to have functional consequences?

The small genome, as more of it is functional (less of it is TEs and other repetitive elements, see previous answers), and so mutations are likely to be deleterious.

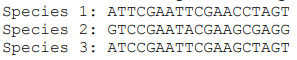

Below is a short region of homologous sequence from 3 species:

(a) How many changes have occurred between species 1 & 2?

(b) Which two species are likely to more closely related?

(c) You sequence a fourth species in this genomic region and find that it is shorter as this species has a deletion in this region. The sequence you obtain for species 4 is: ATCTGAAGAAGGTAGT. What is the best alignment of this sequence to the others? Which species is it closest to?

(a) 6

(b) Species 1 and Species 3. There are 6 differences between Species 1 and Species 2, but only 2 between Species 1 and Species 3.

(c) Best alignment is below, this new species (Species 4) is closest to species 3. Disregarding the deletion in Species 4, there are 2 differences between Species 4 and Species 3, and 4 differences between Species 4 and Species 2, and all the positions where Species 1 and 3 differ from one another, Species 4 has the same base as Species 3.

Species 1: ATTCGAATTCGAACCTAGT

Species 2: GTCCGAATACGAAGCGAGG

Species 3: ATCCGAATTCGAAGCTAGT

Species 4: ATCTGAA---GAAGGTAGT

How can the degree of conservation or change in a genomic region be used to identify functionally important regions of the genome?

Sequences that are conserved in the genomes of two or more species are more likely to have an important conserved function than sequences that are not conserved. If a sequence is functional, mutations will be more likely to have functional consequences, and thus will be more likely to be removed by selection. This will result in higher sequence conservation of this region.

You are studying the coding region of a gene and have aligned the DNA encoding this gene from several different populations of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, and are examining which regions have higher rates of base pair substitutions. Offer a possible explanation for the following observations:

(a) The intron of the gene has a higher substitution rate than the surrounding exons

(b) Codons coding for Pro have a higher substitution rate than codons for Trp

(c) Exon 3 has a higher substitution rate than exon 4

(d) This gene that you are studying has a higher substitution rate than the gene next to it

(a) The higher substitution rate of the intron likely reflects less evolutionary constraint on this region. This may mean that the exact nucleotide sequence of this intron is not important to the function of the gene, therefore if mutations arise in the intron, they will not be selected against.

(b) There are four different codons that code for Pro, and only one that codes for Trp. If mutations arise in the third position of the Pro codon, they will be silent mutations, and will still code for Pro. For Trp, if any of the 3 nucleotides of the codon are changed, it will no longer code for Trp. So, we might expect that the mutations that change one Pro codon to another Pro codon will not be selected against, where any change to the Trp codon very well may be.

(c) If Exon 3 has a higher substitution rate than exon 4, it is likely that the existing nucleotide sequence of exon 4 is more important to the functioning of the protein, and any mutations that arise are strongly selected against so then may be rarely observed.

(d) If the gene you are studying has a higher substitution rate than the gene next to it, then the exact nucleotide sequence of the gene you are studying may be less important, and thus any mutations less likely to be selected against. This could be because the sequence is less important to the functioning of the protein, or that the protein itself is less critical to the fitness of the organism.

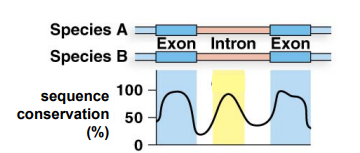

From the figure below, what can you infer about the sequence present in the intron between these two exons? Propose a possible function for this sequence.

The sequence in the intron is likely to be functional, as it has a high degree of sequence conservation between the two species. The level of conservation is as high as the exons of the gene. This sequence is likely to be important for gene expression, perhaps there is an enhancer sequence present in this region, since enhancers can be present in introns.

What types of evolved changes at the gene level can lead to new phenotypes? For each type of change, how could you determine if they had occurred?

At the gene level, new phenotypes could be the product of changing the coding region of the gene (and thus the protein that it codes for), the expression of the gene, or could result from a newly evolved gene. To determine which type of change has occurred, you need to be able to compare your organism with the new phenotype to a population or closely related species without the new phenotype. To find out if there is a change in the coding sequence of the gene, you can sequence the coding region of the gene in an organism with the novel trait and an organism without the trait, and see if there are any changes in the protein coding sequence that would cause changes in the amino acid sequence. To determine if there is a change in gene expression, you can measure or visualize where/when/under what conditions the gene is expressed in your organisms with the trait and without the trait, and see whether there are any differences in gene expression. To figure out if there is a new gene, since new genes are almost always a product of some form of gene duplication, you can look for whether there is more than one gene with a very similar sequence in your organisms with the trait as compared to the organisms without the traits.

You sequence two species, species A and species B. In species A you find two genes A1 & A2 which are homologous to a gene B1 in species B.

(a) Are A1 & A2 better described as paralogs or orthologs?

(b) Are A1 & B1 better described as paralogs or orthologs?

(c) A1 & B1, have introns, and are found at the same relative position in the genomes of species A and species B. But the gene A2 resides on a different chromosome and lacks introns. What is the most likely mechanism of duplication of the A2 gene?

A) paralogs, B) orthologs, C) retrotransposition

Paralogs are genes with similar sequence because they are a product of a duplication event, orthologs are genes with similar sequence across species because they came from a common ancestor.

What are three potential evolutionary fates of a newly duplicated gene? Briefly describe each one

1) Most newly duplicated genes will be non-functional, due to failure to also duplicate important regulatory regions, or the whole coding region of the gene. These duplicates will degrade (acquire mutations) over evolutionary time.

2) If a gene performs multiple functions, one possibility after duplication would be subfunctionalization, where the two copies evolve to divide the ancestral functions between them.

3) Another potential evolutionary outcome after duplication is that one copy can maintain the function of the original gene, whereas the other can evolve a novel function. This is referred to as neofunctionalization.