Chapter 9: Entomology

9.1: Entomology

Forensic entomology — the application of the study of arthropods, including insects, arachnids (spiders and their kin), centipedes, millipedes, and crustaceans, to criminal or legal cases.

- Often, insects are the first to find a corpse, and they colonize it in a predictable pattern.

- Forensically important conclusions may be drawn by analyzing the phase of insect invasion of a corpse or by identifying the life stage of necrophagous insects found in, on, or around the body.

Knowledge of insect biology and habitats may provide information for accurate estimates of how much time a body has been exposed to insect activity.

- A knowledgeable entomologist will be able to tell if the insects are from the local area where the body was found; if they are not, this is a good indication that the body may have been moved.

Taphonomy – the study of an organism from the time it dies until the time it reaches the laboratory.

- The term was coined to describe the analysis of what happened to prehistoric animals, like dinosaurs, from the time they died until they became fossils sitting in a museum case.

9.2: Insects and their Biology

- Insects are the largest group of arthropods and are defined by having six legs and a three-segment body.

- Insects have an external skeleton, or exoskeleton, composed of a material called chitin and protein.

- This outer shell protects the animal’s internal organs, conserves fluids, and acts as the structure for muscle attachment.

==Insect bodies are divided into three segments, which are joined to each other by flexible joints.==

- The head contains the insect’s eyes, sensory organs (including specialized antennae), and mouthparts.

- The thorax is further divided into the prothorax, mesothorax, and metathorax; each of these subsegments has a pair of legs.

- In addition, the mesothorax and metathorax are sites of wing attachment, if the insect has them.

- The abdomen carries much of the insect’s internal organs and is segmented. Each of these segments bears a pair of holes, called spiracles, which the insect uses for breathing.

9.3: Life Cycle on Insects

Insects have developed three patterns of growth:

- Ametabolous

- Metamorphosis

- Holometabolous

- Ametabolous – insects that undergo slight or no metamorphosis.

- Metamorphosis – where the eggs yield immature forms that look like smaller forms of the adults.

- Paurometabolous

- The hatchlings emerge in a form called a nymph, which generally resembles a wingless version of the adult of the species.

- The nymphs and adults will occupy the same habitat and exploit the same food sources.

- Nymphs grow by molting (shedding their skin), and each successive molt produces a new instar or growth phase.

- As the nymph passes through each instar, it increasingly resembles the adult form and eventually develops wings.

- Holometabolous

- The adult lays an egg or deposits a larva onto a food source. The larvae start eating or hatch from the egg and then begin eating immediately and increase in size by molting through instars.

- The larval form is very different from the adult form, both in appearance and in its habitat. At the end of the instars, however, the larvae transition into an inactive phase called the pupal stage.

- The pupa is a hardened outer shell or skin that protects the larva while it undergoes its final growth stage to the adult form.

- Puparium – the hardened skin of the last larval instar and tends to be darker than the normal larval skin.

Necrophilous insects – are very sensitive to chemical changes in a dead body and can detect even the slightest hint of decomposition, sometimes within minutes of death.

- The chemicals are by-products of the decomposition process and signal to the insect that a new food source is available.

- As the body decays, the signals it sends out change and communicates “food” to the different species that inhabit the body at different times and conditions.

9.4: Collecting Insects at Crime Scene

The following is the suggested sequence of stages for a forensic science entomological investigation:

- Visually observing and taking notes of the scene

- Recording notes

- Approximating the number and kinds of insects

- Recording locations of major insect infestations

- Noting immature stages Identifying the precise location of the body

- Observing any other phenomena of note (trauma, coverings, etc.)

- Collecting climatological data from the scene

- Recording ambient air temperature

- Measuring ambient humidity

- Taking the ground surface temperature

- Taking body surface temperatures

- Taking below-body temperatures

- Taking maggot mass temperatures

- Taking post-body removal subsoil temperature

Collecting specimens from the body before its removal from the scene:

- The area surrounding the body (up to 20ft) before its removal

- Directly under the body after the body has been removed.

Necrophilous insects are attracted to dark, moist areas:

- On fresh bodies, this means the face (nostrils, mouth, eyes, etc.) or any open wounds.

- The genital or rectal areas, if exposed or traumatized, will sometimes provide shelter and moisture for ovipositing flies.

Flying insects can be trapped in a net by sweeping it back and forth repeatedly over the body. The end of the net, with the insects in it, can then be placed in a wide-mouth killing jar, a glass jar containing cotton balls soaked in ethyl acetate.

- Several minutes of exposure to the ethyl acetate will kill the insects; they should then be placed in a vial of 75% ethyl alcohol (ETOH) to preserve them.

Crawling insects on and around the body can be collected with forceps or fingers. The entomologist must be careful not to disturb any other potential evidence while collecting insects.

Once the body has been removed, the soil under the body should be sampled. An approximately 4″ × 4 × 4″ cube of soil should be taken from areas associated with the body, such as the head, torso, limbs, or wherever seems appropriate given the body’s position.

- Additional soil samples should be taken up to 6 ft from the body in each direction. Any plant materials associated with the body or its location should also be collected for possible botanical examination

Buried or enclosed remains present particular problems for the entomologist because insects’ access to a body is limited. Some flies are barred from a body by as little as one inch of soil.

- Burial also slows the process of decomposition due to lower and more constant temperatures, fewer bacteria, and limited access to the body.

A building can also prevent some types of insects from gaining access to a body or slow down their recognition of the chemical odors that signal decomposition.

- This alters the entomologist’s estimation of time since death because the “clock” of insect succession rate has been altered.

- The odors may escape, but the insects may not be able to gain access: Finding a cloud of flies hovering above a car trunk may indicate that a dead body has been in there for some time.

9.5: Post Mortem Interval

Being able to provide a time range for when the crime occurred is of great importance in limiting the number of suspects who may or may not have an alibi.

Calculating an estimated PMI sets a minimum and maximum time since death based on the insect evidence collected and developed.

- A minimal PMI is estimated by the age of developing immature insects and the time needed for them to grow to adulthood under the conditions surrounding the crime scene.

- A maximal PMI can be difficult to estimate because the uncertainty widens as time and decomposition continues.

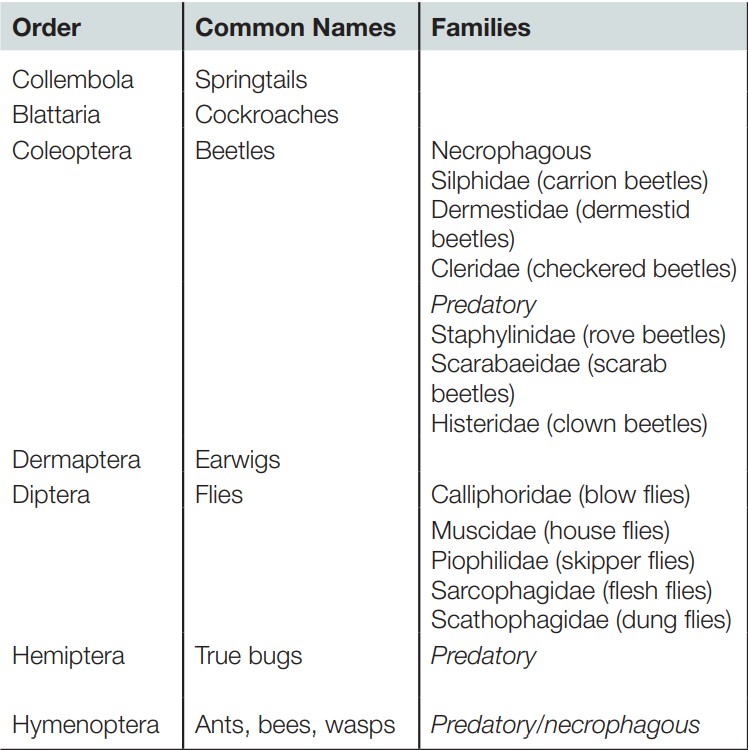

9.6: Classification of Insects

Taxonomy – the science of identifying and classifying organisms

Taxonomic Key – a method for classifying organisms where each trait identified separates otherwise similar groups of organisms.

9.7: Rearing Insects

- A significant step in identifying immature insects, especially flies, is the rearing of larvae into adult insects. This process is not as easy as it may initially sound. Because these immature insects are the reference materials for the forensic entomologist’s estimation of PMI, their growth environments must be closely controlled and monitored.

- A vent hood is a necessity: Because their food source is rotting meat (typically beef, pork, or liver), the smell can become unpleasant.

- It is important to remember that fly larvae grow into adult flies, and they must be kept from zipping across the laboratory. The laboratory must be designed so that it is easy to clean after the casework is completed.

9.8: DNA and Insects

- DNA analysis is used outside forensic science to identify insect species.

- Barcode of Life – the project to collect information on all known species.

- Another use of DNA with insects is to extract the gut contents of maggots in the hopes that nuclear or mitochondrial DNA from the deceased can be extracted, analyzed, and compared.

- Not only can this potentially assist in the identification of decedents, but this approach has relevance to identifying maggots that were actually on a particular corpse—if the maggot was not on that body, then its stage of development is not relevant to estimating how long the decedent had been dead

9.9: Calculating a PMI

A method for establishing a PMI is based on an ecological and faunal study of the cadaver.

- Data collection must be detailed and precise if the PMI is to be accurate.

- The basis of the method is to study which insects, or their young, inhabit a dead body and in what sequence they do so.

Four Ecological Categories exist in the cadaver community:

Necrophagous Species – which feed on the carrion itself, contributing directly to the estimation of PMI.

- Diptera, coleoptera, silphidae, and dermestidae.

Predatory and parasitic species – they prey on other insects, including the necrophagous ones, which inhabit the cadaver.

- Coleoptera, sulfide, and some Diptera.

Omnivorous Species – they may eat material from the body, other insects or whatever food source presents itself.

- They use the cadaver simply as an extension of their normal habitat.

- Wasps, ants, and some Coleoptera.

The faunal succession on carrion is linked to the natural changes that take place in a body following death.

- Their accuracy and utility diminish as time moves forward, however, and other information, namely ecological, must be used.

Another more complete and more complicated method of PMI estimation involves the study of the succession of insect species on and within a body.

If no data are available that take into account the parameters that the forensic entomologist faces, then experimentation is required.

- The experimental conditions should be as close to those at the crime scene as possible; this logically means that a forensic entomologist should be collecting data on decomposition in his or her ecological zone(s) year-round.

One of the most influential factors in estimating PMI is temperature. The temperature has a direct effect on the metabolism and development of insects.

- When a group of maggots is living, feeding, and moving all in approximately the same area, the temperature can soar by many degrees — the maggot mass effect.

- The temperature at the center of a maggot mass can be 100 °F while the ambient temperature is in the 30 °F range, and this could bias a forensic entomologist’s PMI estimation.

\n