Chapter 10

1/51

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

52 Terms

Why Do People Help?

prosocial behaviour

Sometimes people act in a prosocial manner out of self-interest hoping to get something in return.

prosocial behaviour motivated by altruism

Prosocial Behaviour

any act performed with the goal of benefiting another person

Altruism

the desire to help another person or group of people, even if it involves a cost to the helper

Evolutionary Psychology: Instincts and Genes

Contrary to the idea of kin selection, the degree of genetic relatedness did not predict willingness to help.

Instead, the critical variable was the degree of closeness:

Participants were most likely to help the family members to whom they had the closest emotional ties, rather than those to whom they were most closely related.

Evolution may actually have created the tendency to help those who are close to us, rather than the tendency to help those who are related to us.

According to Charles Darwin's (1859) theory of evolution, natural selection:

Favours genes that promote the survival of the individual.

Any gene that furthers our survival and increases the probability that we will produce offspring is likely to be passed on from generation to generation.

Genes that lower our chances of survival, such as those that cause life-threatening diseases, reduce the chances that we will produce offspring and thus are less likely to be passed on

Evolutionary psychologists attempt to explain social behaviour in terms of genetic factors that evolved over time according to the principles of natural selection

Darwin realized early on that a potential problem exists with evolutionary theory which was

How can it explain altruism?

If people's overriding goal is to ensure their own survival, why would they ever help others at a cost to themselves?

It would seem that over the centuries, altruistic behaviour would disappear because people who acted that way would, by putting themselves at risk, produce fewer offspring than would people who acted selfishly.

One way that evolutionary psychologists attempt to resolve this dilemma is with the notion of kin selection

To explain altruism, evolutionary psychologists also point to the norm of reciprocity

Kin Selection

The idea that behaviours that help a genetic relative are favoured by natural selection

People can increase the chances that their genes will be passed along not only by having their own children but also by ensuring that their genetic relatives have children.

Because a person's blood relatives share some of their genes, the more that person ensures their survival, the greater the chance that that person's genes will flourish in future generations.

natural selection should favour altruistic acts directed toward genetic relatives.

genetic relatedness was a strong predictor of estate allocations. In other words, the closer the genetic link, the greater the designated inheritance

People also report that they would be more likely to help genetic relatives than non-relatives in life-and-death situations, such as a house fire, but not when the situation is non- life threatening.

all participants follow this rule of kin selection in life-threatening situations

when people became aware there was a fire, they were much more likely to search for family members before exiting the building than they were to search for friends.

According to evolutionary theory, however, the genes of people who follow this "biological importance" rule are more likely to survive than the genes of people who do not.

they argue that over the millennia, kin selection became ingrained in human behaviour

The Reciprocity Norm

the expectation that helping others will increase the likelihood that they will help us in the future.

The idea is that as human beings were evolving, a group of completely selfish individuals, each living in their own cave, would have found it more difficult to survive than a group composed of members who had learned to cooperate with one another.

Those who were most likely to survive, the argument goes, were people who developed an understanding with their neighbours about reciprocity: "I will help you now, with the agreement that when I need help, you will return the favour."

Because of its survival value, such a norm of reciprocity may have become genetically based

reciprocity can already be detected in infancy

even infants reciprocate good deeds.

What is even more amazing is that they can pick up on whether someone intends to help them and reciprocate accordingly

Learning Social Norms

one more link between evolution and altruism.

it is highly adaptive for individuals to learn social norms from other members of a society

Over centuries, a culture learns such things as which foods are poisonous and how members of the culture should cooperate with one another; the person who learns these rules is more likely to survive than the person who does not.

through natural selection, the ability to learn social norms has become part of our genetic makeup.

One norm that people learn is the value of helping others; this is considered to be a valuable norm in virtually all societies.

people are genetically programmed to learn social norms, and one of these norms is altruism

has argued that it is to our evolutionary advantage to engage in prosocial behaviours toward others because those who cooperate are more likely to survive.

evolutionary psychologists believe that people help others because of factors that have become ingrained in our genes.

Social Exchange: The Costs and Rewards of Helping

Although some social psychologists disagree with evolutionary approaches to prosocial behaviour, they do agree that altruistic behaviour can be based on self-interest.

The difference from evolutionary approaches is that social exchange doesn't trace this desire back to our evolutionary past, nor does it assume that the desire to help is genetically based.

Social exchange theorists assume that in our interactions with others, we try to maximize our social rewards and costs.

people help only when the benefits outweigh the costs. True altruism, in which people help even when doing so is costly, does not exist, according to this theory.

What might be the rewards of helping?

First, as we saw with the norm of reciprocity, helping someone is an investment in the future-it can increase the likelihood that we will be helped in return.

Helping can also relieve the distress of the bystander.

people are aroused and disturbed when they see another person suffer, so they help at least in part to relieve their own distress

By helping others, we can also gain such rewards as social approval from others and increased feelings of self-worth.

helping can be costly

Therefore, helping decreases when the costs are high, as when it would put us in physical danger, result in pain or embarrassment, or take too much time

Is true altruism, motivated only by the desire to help someone else, really such a mythical act?

a social exchange theorist might reply that there are many ways in which people can obtain gratification, and we should be thankful that one way is by helping others.

Still, many people are dissatisfied with the argument that all helping stems from self-interest.

According to some social psychologists, people do have hearts of gold and sometimes help only for the sake of helping

Empathy and Altruism: The Pure Motive for Helping

Daniel Batson (1991) is the strongest proponent of the idea that people help purely out of the goodness of their hearts.

He acknowledges that people sometimes help others for selfish reasons, but argues that people's motives are also sometimes purely altruistic, in that their only goal is to help the other person, even if doing so involves some cost.

Pure altruism is likely to come into play, he maintains, when we feel empathy for the person in need of help.

A person’s decision of whether to help or not depends first on whether they feel empathy for them, and if they do, they will help regardless of what they have to gain

Your goal will be to relieve the person's distress, not to gain something for yourself.

This is the crux of Batson's empathy-altruism hypothesis

it can be difficult to isolate the exact causes of complex social behaviours.

If you saw someone help the person pick up their things, how could you tell whether that helper was acting out of empathic concern or to get some kind of social reward?

an act that seems truly altruistic is sometimes motivated by self-interest

participants in the high-empathy condition reported feeling more empathy with Carol than did those in the low-empathy condition.

According to the empathy-altruism hypothesis, if empathy were high, people should have been motivated by genuine altruistic concern and should have helped regardless of the costs.

In the high-empathy condition, about as many people agreed to help when they thought they would see Carol in class as when they thought they would not see her in class.

people had Carol's interests in mind, not their own.

In the low-empathy condition, however, many more people agreed to help when they thought they would see Carol in class than when they thought they would not see her in class

when empathy was low, social exchange came into play, in that people based their decision to help on the costs and benefits to themselves. They helped when it was in their interests to do so but not otherwise

The important role of empathy also has been demonstrated in studies conducted with children.

those who were able to put themselves in another person's shoes were more likely to behave in prosocial ways toward them (e.g., helping an experimenter who dropped a box of paper clips, letting a friend have a turn at an enjoyable game).

empathy was related to helping among children as young as five years old

There is no doubt that empathy plays an important role in promoting prosocial behaviour.

empathy takes effort, and, therefore, people might actively want to avoid it

if given a choice between an empathy task (viewing photos of child refugees and writing about the child's feelings) and a detached task (viewing the same photos, but being asked to remain objective and describe the child's age and gender), people were significantly more likely to choose the detached task.

The empathy task was perceived by participants as more effortful, mentally demanding, and unpleasant than the detached task. They also tended to feel they weren't particularly good at it.

Those who were led to believe they were good at empathy subsequently were more likely to choose the empathy task than the detached task and found it less effortful and demanding.

the longer participants engaged in the empathy task, the more effortful and unpleasant they found it. However, these participants were likely to donate more money to a children's charity than those who spent less time being empathic

people will sometimes help out of a concern for others even when there is no tangible benefit to themselves.

But it is hard to prove there is nothing in it for them.

some theorists have argued that what ultimately motivates us to help others, even when there are costs to doing so, is the good feeling that results.

when people help others, the same parts of their brain are activated as when they receive rewards such as food, water, and sex

Empathy

The ability to put oneself in the shoes of another person, experiencing events and emotions the way that person experiences them

Empathy-altruism hypothesis

When we feel empathy for another person we will attempt to help that person purely for altruistic reasons, regardless of what we have to gain

What if you do not feel empathy? If, for whatever reason, you do not share the other person's distress

Then Batson says social exchange comes into play

What's in it for you?

If there is something to be gained, such as obtaining approval from the person or from onlookers, you will help the person pick up their things.

If you will not profit from helping, you will go on your way without stopping.

Individual Differences: The Altruistic Personality

People with altruistic personalities tend to show empathy and sympathy for others and feel it is important to follow the norm of social responsibility.

These people help more people in a wider variety of situations, including providing help to co-workers, donating organs, and volunteering, and also have been found to help more quickly than do people who score lower on scales to measure this personality trait

The altruistic personality is in part heritable.

identical twins are more similar to each other in both their helping-related emotions (e.g, empathy) and their actual helping behaviour than are fraternal twins, who share only a portion of their genetic makeup

prosociality may have a genetic component

Altruistic personality

A personality trait characterized by qualities such as sympathy, empathy, and felt responsibility to help other across a wide variety of situations

Gender Differences in Prosocial Behaviour

In virtually all cultures, norms prescribe different traits and behaviours for males and females, learned as children grow up.

The recipients of the Medal of Bravery bestowed by Canada's governor general for "acts of bravery in hazardous circumstances" tend to be men.

Now consider the Governor General's Caring Canadian Award. This award was intended to honour Canadians who had given extraordinary help or care to others. More women have been the recipients of this award than men.

The winners of both of these awards were more likely than a comparison group of adults to have been helpers in early life, to be securely attached, and to show a pattern of nurturant compassion coupled with decisive action taking.

Recipients of caring awards were higher in nurturance, more optimistic, and generally tended to be more focused on close relationships than recipients of bravery awards

helping that involves nurturance and commitment is more likely to be performed by women than by men

women spent nearly twice as many hours per month providing emotional support than did men.

Women also provided more practical help to kin

This pattern was also found in a study of seven different cultures

Gender Differences in Prosocial Behaviour - In Western cultures

male sex role includes being chivalrous and heroic;

females are expected to be nurturing and caring and to value close, long-term relationships

Socioeconomic Status Differences in Prosocial Behaviour

people develop different self-concepts, depending on how wealthy they are

Lower-class people:

tend to develop more communal self-concepts, meaning that the self is defined in terms of social connection to others.

Upper-class people:

tend to develop more agentic self-concepts, whereby the self is defined in terms of an individual person's capacity for personal control.

Wealthy people also score higher on measures of narcissism and entitlement

wealthy people were more willing to donate, and actually donated more, when they received an agentic message.

agentic message that encouraged them, as individuals, to donate

Less wealthy people were more willing to donate after receiving a communal message.

communal message that emphasized the importance of working together

in order to encourage rich people to be more generous, it is important to frame requests using terms that match their self-concept.

Does being poor make you more helpful?

people who are of lower socioeconomic status (SES) gave more of the money they earned during an experiment to their partner in the experiment, were more likely to help their partner in an experiment complete his or her tasks, and, in another study, when asked what percentage of one's income should be donated to charity, gave a higher number than did participants with a higher SES

Priming compassion had the effect of making people with high SES just as generous as people with low SES typically are.

people who have a lower SES are more concerned with the needs of others than those who have a higher SES, and this concern leads them to act in prosocial ways.

Cultural Differences in Prosocial Behaviour

when it comes to helping, people favour their in-groups, and discriminate against out-groups

there is a long history of discrimination and prejudice toward out -group members, including those of different races, cultures, genders, and non-heterosexual identities.

people often help both in-group and out group members, but for different reasons.

People are more likely to feel empathy for in-group members who are in need, and this, in turn, leads to increased helping.

we tend to help people from out groups for a different reason.

we are likely to help only when there is something in it for us, such as making us feel good about ourselves or making a positive impression on others.

Cultural factors do come into play in determining how strongly people draw the line between in-groups and out-groups.

In many interdependent cultures, the needs of in-group members are considered more important than those of out-group members.

members of these cultures are more likely to help in-group members than are members of individualist cultures

However, because the line between "us" and "them" is more firmly drawn in interdependent cultures, people in these cultures are less likely to help members of out-groups

This may be why people in China, a collectivist culture, score lower on scales that assess the altruistic personality type than people in Canada, an individualist culture

the altruistic intentions of students in Canada and Japan,

Canadian students expressed greater altruism toward "a person one happens to see occasionally but with whom they have no relation."

Canadians and Japanese students did not differ when the person was described as someone with whom one has "personal and close relations."

cultural norms about taking credit for helping others may also contribute to the perception that people from Asian cultures are less altruistic overall than people from Western cultures.

in Asian cultures, children are taught to be modest and self-effacing_ and this includes not seeking recognition for helpful acts.

Canadian children believed that Kelly should acknowledge this helpful act (thereby garnering the praise of the teacher); Chinese children believed that Kelly should not admit that she had done so because begging for praise would violate social norms of modesty

Same thing was found in adults

In-groups

the groups with which an individual identifies as a member

Out-groups

the groups with which an individual does not identify with

Why Being Rich Might Make You a Jerk

People who drove expensive cars were more likely to ignore the rules of the road. The worst offenders were drivers of black Mercedes!

12.4 percent of all drivers cut in front of cars who had the right of way.

But the drivers of the fanciest cars were four times as likely as those driving cheaper cars to cut in front of another driver

the more expensive the car, the less likely the driver was to stop for a pedestrian on a crosswalk

there's something about wealth and being at the top that you kind of feel like I'm above the law ... It makes us think of the perils of prestige.

rich people were, in fact, more likely to lie, cheat, make unethical decisions and believe it was beneficial and justifiable to be greedy.

participants who were primed with wealth and status took significantly more candy. for themselves, leaving less for the children next door, compared to those who were primed with low social status

"This tells us even the perception of wealth can generate this behavior.

It's not about character, it's not about who people are or some inborn characteristic of wealthy people that creates these patterns. It's that the situation of wealth drives a lot of behaviors."

wealth breeds greed and greed breeds unethical behaviour

Religion and Prosocial Behaviour

Most religions teach some version of the Golden Rule, urging us to do unto others as we would have others do unto us.

An important feature of religion is that it binds people together and creates strong social bonds.

religious people are more helpful than nonreligious people, with the important qualification that the person in need shares their religious beliefs

religious people engage in more charitable giving and volunteerism

"across the board", not just toward their own group.

people in Canada who attend religious services give more money to charity and engage in more volunteer work than people who do not attend religious services

Statistics Canada data show that people who attend religious services at least once a week are more inclined to donate to charities and, on average, they make larger donations.

65 percent of those who attend religious services on a weekly basis also engaged in volunteer work, compared to 44 percent of those who did not.

these people also dedicated about 40 percent more hours in volunteer work.

those who attended religious services once a week contributed many more of their volunteer hours to religious organizations compared to less frequent attendees (42 versus 4 percent), but the majority of their volunteer hours were donated to nonreligious organizations.

When it comes to helping strangers, though, for example, such as donating blood or tipping a server, research has shown that religious people are no

more helpful than nonreligious people

people who are primed with religion actually behave more prosocially (e.g., giving more money to other participants in a study; being more willing to help in various ways) than those who are not.

These effects are even more pronounced for people who hold strong religious beliefs.

religion is certainly not the only cause of prosocial behaviour but argue that there is clearly a link between religiosity and performing good deeds.

There also is a link between morality and prosocial behaviour.

Participants who were primed with God donated the most money to their partner in the experiment (regardless of whether the participant actually believed in God).

Those who were primed with morality were nearly as generous as those who were primed with God.

the primes served to increase self-awareness which, in turn, made people more likely to behave in line with their altruistic values.

The Effects of Mood on Prosocial Behaviour

Would you stop to help them? The answer might depend on the mood you happen to be in that day.

Effects of Positive Moods: Feel Good, Do Good

It turned out that finding the dime had a dramatic effect on helping. Only 4 percent of the people who did not find a dime helped the man pick up his papers, whereas a whopping 84 percent of the people who found a dime did.

when people are in a good mood, they are more helpful in many ways, including contributing money to charity, helping someone find a lost contact lens, tutoring another student, donating blood, and helping co-workers on the job

These effects are found in studies of adults and even very young children.

when people do good deeds, they experience more positive emotions.

especially true when the good deeds are motivated by the desire to help another person, rather than to promote one's own goals

Does "Do Good, Feel Good" Apply to Spending Money on Others?

people who spend money on others are happier than people who spend money on themselves

We are even happier if we are spending our money on someone to whom we are close compared to someone with whom we have a less close relationship

even among at-risk youth and ex-offenders (populations that are high on traits reflecting a lack of concern for others), happiness was greater when spending on another person rather than oneself

the relation between prosocial spending and happiness occurs regardless of whether one lives in an affluent country or a poor one.

a positive correlation between charitable giving and happiness in 120 out of 136 countries included in their research

the joy of giving appears to be universal.

not only does prosocial spending lead to happiness, but the happiness that is created leads to further prosociality

next time you have a little money to spend, rather than buying yourself a treat, try treating a friend or donating the money to charity. You might be surprised by how good you feel!

Negative-State Relief: Feel Bad, Do Good

sadness can also lead to an increase in helping, because when people are sad, they are often motivated to engage in activities that make them feel better

if you are feeling down, you are more likely to engage in helpful actions such as donating money to a charity

The warm glow of helping lifts us out of the doldrums.

Another kind of negative mood also increases helping: feeling guilty

People often act on the idea that good deeds cancel out bad deeds.

When they have done something that makes them feel guilty, helping another person balances things out, thereby reducing their guilty feelings.

Thus, if you just realized you had forgotten your best friend's birthday, you would be more likely to help the person in the mall pick up their papers to repair your guilty feelings.

Environment: Rural versus Urban

people in small towns are more likely to assist when asked to help a lost child, give directions, or return a lost letter.

help is more likely to be offered in small towns than in large cities has been reported in several countries, including Canada, the United States, Israel, Australia, Turkey, Great Britain, and Sudan

people living in cities are constantly being bombarded with stimulation, and therefore might keep to themselves to avoid being overloaded by it.

if you put urban dwellers in a calmer, less stimulating environment, they would be as likely as anyone else to reach out to others, (urban-overload hypothesis)

Research supports the urban-overload hypothesis more than the idea that living in cities makes people less altruistic by nature

to predict whether people will help, it is more important to know whether they are currently in a rural or urban area than it is to know if they happened to grow up in a big city or a small town.

Why are people more likely to help in small towns?

One possibility is that people who grow up in a small town are more likely to internalize altruistic values.

If this were the case, people who grew up in small towns would be more likely to help, even if they were visiting a big city.

Alternatively, the immediate surroundings, and not people's internalized values, might be the key.

urban-overload hypothesis

if you put urban dwellers in a calmer, less stimulating environment, they would be as likely as anyone else to reach out to others

Residential Mobility

people who have lived in one place for a long time are more likely to engage in prosocial acts that help the community.

Residing in one place for a long time leads to greater attachment to the community, more interdependence with one's neighbours, and a greater concern for one's reputation in the community

people who have lived in one place for a while feel more of a stake in their community.

helpfulness can increase quite quickly. even in a one-time laboratory setting.

depends on how long you have been in the group with the struggling student.

another reason that people might be less helpful in big cities is that residential mobility is higher in cities than in rural areas.

People are more likely to have just moved to a city and thus less likely to feel part of a community.

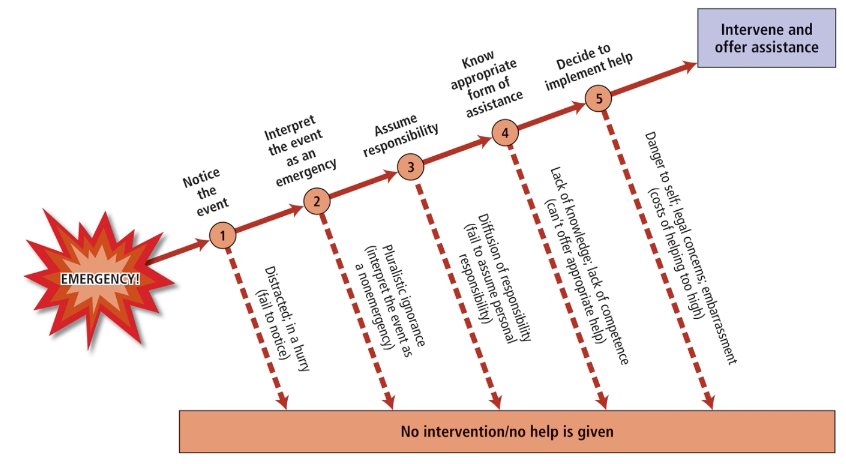

Bystander Intervention: The Latané and Darley Model

they thought, it might be that the greater the number of bystanders who observe an emergency, the less likely it is that any one of them will help.

"We came up with the insight that perhaps what made the Genovese case so fascinating was itself what made it happen namely, that not just one or two, but 38 people had watched and done nothing".

in terms of receiving help, there is no safety in numbers.

the answer depended on how many people the participant thought witnessed the emergency.

When people believed they were the only one listening to the student have the seizure, most of them (85 percent) helped within a minute. By 2.5 minutes, 100 percent of the people who thought they were the only bystander had offered assistance

when the research participants believed there was one other student listening, fewer people helped only 62 percent in the first minute.

helping occurred more slowly when there were two bystanders and never reached 100 percent, even after six minutes, at which point the experiment was terminated.

when the participants believed there were four other students listening in addition to themselves, the percentage of people who helped dropped even more dramatically. Only 31 percent helped in the first minute, and after six minutes only 62 percent had offered help.

Bystander Effect

effect-the greater the number of bystanders who witness an emergency, the less likely any one of them is to help the victim

Why is it that people are less likely to help when other bystanders are present?

Latané and Darley (1970) developed a five-step tree model to explain the process of deciding whether to intervene in an emergency

Part of this description, as we will see, is an explanation of how the number of bystanders can make a difference.

What determines whether people notice an emergency? - Noticing an Event

something as seemingly trivial as how much of a hurry people are in can make more of a difference than what kind of person they are.

If they were not in a hurry, most of them (63 percent) did.

However, only 10 percent of the people hurrying to keep their appointment stopped to help.

Many of the students who were in a hurry did not even notice the man.

the seminary students who were the most religious were no more likely to help than those who were the least religious.

One variable that made a difference: whether the students saw religion as a quest (an open-minded search for truth) versus a set of traditions.

Those who viewed religion as a quest were no more likely to stop, but those who did stop were more responsive to the man's needs than those who viewed religion as a set of traditions.

Interpreting the Event as an Emergency

whether the bystander interprets the event as an emergency that is, as a situation in which help is needed

Often, however, the situation is more ambiguous. Is the person on the park bench just sleeping, or are they unconscious?

If people assume that nothing is wrong when an emergency is taking place, obviously they will not help.

when other bystanders are present, people are more likely to assume that an emergency is actually not an emergency.

This type of social influence occurs when we use other people to help us define reality.

it's often a good strategy to use other people as a source of information when we are uncertain about what's going on.

The danger is that sometimes no one is sure what is happening.

an emergency is often a sudden and confusing event, bystanders tend to freeze, watching and listening with blank expressions as they try to figure out what's taking place.

Step 2 in this model, interpreting the event as an emergency, is actually a broader step that includes non-emergency kinds of helping as well.

Latané and Darley's model would suggest that if you decided that help was needed, you would be more likely to step in. If you decided that help wasn't needed the person seemed to have the situation under control--you would be much less likely to intervene.

children as young as 2.5 to 3 years are able to discern whether help is needed or not

if the child wasn't able to execute the help that was required (e.g., the experimenter wanted to put the books in a tall cabinet), 50 percent of them requested that their primary caregiver help the experimenter.

early on in human development, helping is more likely to be given when there is a perceived need for it

pluralistic ignorance

wherein people think that everyone else is interpreting a situation in a particular way when they are not.

When an emergency occurs, for example, bystanders often assume that nothing is wrong because no one else looks concerned even though everyone is worried and concerned.

Assuming Responsibility

even if we interpret an event as an emergency, we have to decide that it is our responsibility not someone else's to do something about it.

the number of bystanders is a crucial variable.

helping often entails costs; we can place ourselves in danger, and we can look foolish by overreacting or doing the wrong thing.

children as young as 5 years of age show diffusion of responsibility.

diffusion of responsibility also operates in the online world.

especially likely to occur when people cannot tell whether someone else has already intervened.

diffusion of responsibility

each bystander's sense of responsibility to help decreases as the number of witnesses to an emergency or crisis increases.

Because other people are present, no single bystander feels strong personal responsibility to take action.

Knowing How to Help

The person must decide what form of help is appropriate

If people don't know what form of assistance to give, obviously they will be unable to help.

Deciding to Implement Help

even if you know exactly what kind of help is appropriate, there are still reasons why you might decide not to intervene.

For one thing, you might not be qualified to deliver the right kind of help.

Or you might be afraid of making a fool of yourself.

It can be embarrassing to intervene, only to discover that a situation actually wasn't an emergency.

Even some forms of helping can be embarrassing.

costs of helping such as embarrassment can be barriers to providing help.

Another cost of helping is fear of doing the wrong thing and making matters worse, or even of placing yourself in danger by trying to help.

How Can Helping Be Increased?

We would all be better off, however, if prosocial behaviour were more common than it is.

people do not always want to be helped.

Receiving help can make us feel inadequate and dependent.

As a result, we do not always react positively when someone offers us aid.

When we do not want to appear incompetent, we may suffer in silence even if doing so lowers our chances of successfully completing a task

Intervene

simply being aware of the barriers to helping can increase people's chances of helping.

This is exactly what most participants did if they had not heard the lecture about bystander intervention research; in this condition, only 25 percent of them stopped to help the student.

However, if participants had heard the lecture about bystander intervention, 43 percent stopped to help the student

several countries are now implementing bystander intervention programs.

these programs are aimed at training students to understand the barriers to intervention and giving them strategies for intervening in sexual harassment and sexual violence situations.

The program promoted by the Public Health Agency of Canada is known as "Bringing in the Bystander®"

When a similar program was implemented in high schools in the United States, reports of sexual violence decreased significantly in schools that received the intervention training

the students who received the intervention reported positive effects such as feeling more empowered to intervene in sexual assault situations, greater willingness to take responsibility, and so on.

these positive effects generally were maintained when these participants were contacted again four months later.

people can be trained to overcome barriers to prosocial behaviour and help their fellow human beings in need.

Can Playing Prosocial Video Games and Listening to Prosocial Music Lyrics Increase Helpfulness?

people act in prosocial ways after playing prosocial video games

people who have just played a prosocial video game are more likely to help in all of these situations than were people who had just played a neutral video game

playing prosocial video games has a positive effect on prosocial thoughts, feelings, and behaviours

It isn't just prosocial video games that can make people more helpful-listening to songs with prosocial lyrics works too.

people who listen to such songs, such as Michael Jackson's "Heal the World" or the Beatles' "Help," are more likely to help someone than people who listened to songs with neutral lyrics such as the Beatles'

"Octopus's Garden"

Why does playing a prosocial video game or listening to prosocial song lyrics make people more cooperative?

It works in at least two ways: by increasing people's empathy toward someone in need of help and increasing the accessibility of thoughts about helping others

Instilling Helpfulness with Rewards and Models

prosocial behaviour occurs early in life, children as young as 18 months frequently help others, such as assisting a parent with household tasks or trying to make a crying infant feel better

One powerful way to encourage prosocial behaviour is for parents and others to reward such acts with praise, smiles, and hugs.

these kinds of rewards increase prosocial behaviour in children

Rewards should not, however, be emphasized too much, cause that causes overjustification effect

The trick is to encourage children to act prosocially but not be too heavy-handed with rewards.

One way of accomplishing this is to tell children, after they have helped, that they did so because they are kind and helpful people.

Such comments encourage children to perceive themselves as altruistic people, so they will help in future situations even when no rewards are forthcoming

Same thing for adults; adults who volunteer for external reasons are less likely to volunteer in the future than those who have freely chosen to do so

nearly half of the Canadians who engage in volunteerism signed up on their own initiative (rather than for external reasons, such as another person asking them).

These intrinsically motivated volunteers donated an average of 142 volunteer hours in the past 12 months compared to 97 hours donated by those who were less self-motivated

Another way for parents to increase prosocial behaviour in their children is to behave prosocially themselves.

Children generally model behaviours they observe in others, including prosocial behaviours

Children who observe their parents helping others (e.g., volunteering to help the unhoused) learn that helping others is a valued act.

Interviews with people who have gone to great lengths to help others _ such as Christians who helped Jews escape from Nazi Germany during World War II indicate that their parents were also dedicated helpers

people whose parents had done volunteer work are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviours such as charitable giving and volunteerism

Canadian youths who spend time volunteering are likely to have parents who have instilled values of kindness and helping and who model those behaviours.

The lesson for parents and other adults is clear: If you want children to be altruistic, act in altruistic ways yourself.

One way to avoid a diffusion of responsibility is to point to one person and ask for their help.

That is, instead of shouting, "Will someone please help me?" single out one person - "Hey, you in the blue shirt and sunglasses -could you please call 911?"

911?" That makes one person feel responsible and also communicates to them how to help.

overjustification effect

rewarding people too strongly for performing a behaviour can lower their intrinsic interest in it because they come to believe they are doing it only to get the reward.

The Lost Letter Technique

people were more likely to mail letters addressed to organizations that they supported; for example, 72 percent of letters addressed to

"Medical Research Associates" were mailed, whereas only 25 percent of letters addressed to "Friends of the Nazi Party" were mailed.

people living in small towns were more likely to mail the letters