MBF Final Unit 1 and 2

1/79

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

80 Terms

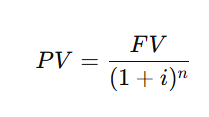

Present value formula- Simple

Where:

𝐹𝑉 = future value

𝑖 = interest rate

𝑛 = number of periods

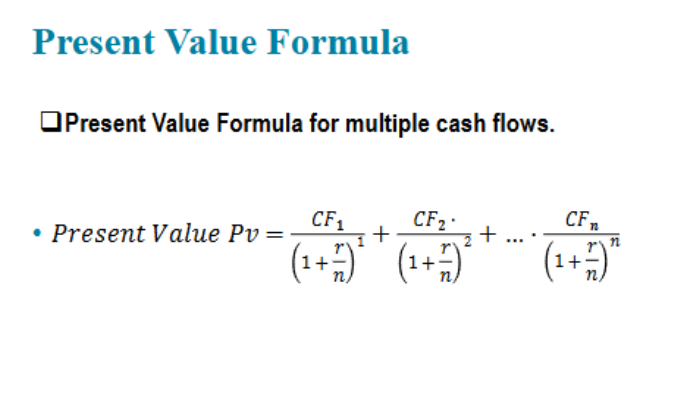

Present value for multiple cash flows

Where:

PV = present value (value today of all future cash flows)

CF of t= cash flow received in period t)

r = annual interest rate/ discount rate (interest rate per period)

t = time period when the cash flow is received

n = total number of periods

This includes any repeated cash flow stream

Present Value definition

Today’s value of a payment to be received in the future, when the interest rate is i.

Equation to find value today of future money

Key ideas:

Higher interest rate → lower present value

Longer time → lower present value

What happens to PV when the interest rate increases?

PV decreases- the higher the discount rate, the lower the present value

fixed-payment loan

A credit market instrument that provides the borrower with an amount of money that is repaid through fixed periodic (usually monthly) payments made over a set number of years

Discount bond

A credit market instrument that is bought at a price below its face value and whose face value is repaid at the maturity date; it does not make any interest payments. Also called a zero-coupon bond.

A discount bound is a bond that:

Short-term

Has no coupon payments

Is sold below par (below $1,000)

Pays one lump sum payment at maturity (the face value)

Difference between coupon and discount bond

Unlike a coupon bond, a discount bond does not make any interest payments; it just pays off the face value.

For example, a one-year discount bond with a face value of $1,000 might be bought for $900; in a years time, the owner would be repaid the face value of $1,000.

Coupon Bond

A credit market instrument that pays the owner a fixed interest payment every year until the maturity date, at which time a specified final amount is repaid.

Face value:

A specified final amount paid to the owner of a coupon bond at the maturity date. Also called par value.

A coupon bond is a bond that:

Pays annual (or semiannual) coupon payments

Returns the face value at maturity

Has price that depends on the market interest rate

Ex: most treasury notes, corporate bonds

Coupon rate

The dollar amount of the yearly coupon payment expressed as the percentage of the face value of a coupon bond.

Coupon rate never changes (Coupon Rate = Coupon Payment/ Face Value).

Yield to maturity

The interest rate that equates the present value of payments received from a credit market instrument with its value today.

Alt: The discount rate that makes the present value of all a bond’s future cash flows equate its current price; essentially the bond’s internal rate of return if held to maturity.

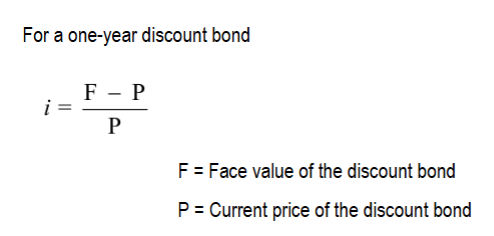

Yield to maturity on discount bond

The yield to maturity equals the increase in price over the year divided by the initial price.

As with a coupon bond, the yield to maturity is negatively related to the current bond price.

Simple Loan

Refers to a credit market instrument giving the borrower an amount of funds that must be repaid to the lender at the date of maturity along with an extra payment (interest)

Yield to maturity on a simple loan

To calculate yield to maturity on a simple loan, use present value equation, and solve for i.

Example: If Pete borrows $100 from his sister and next year she wants $110 back from him, what is the yield to maturity on this loan?

Solution:

100 = 110/ (1+i) = 10%

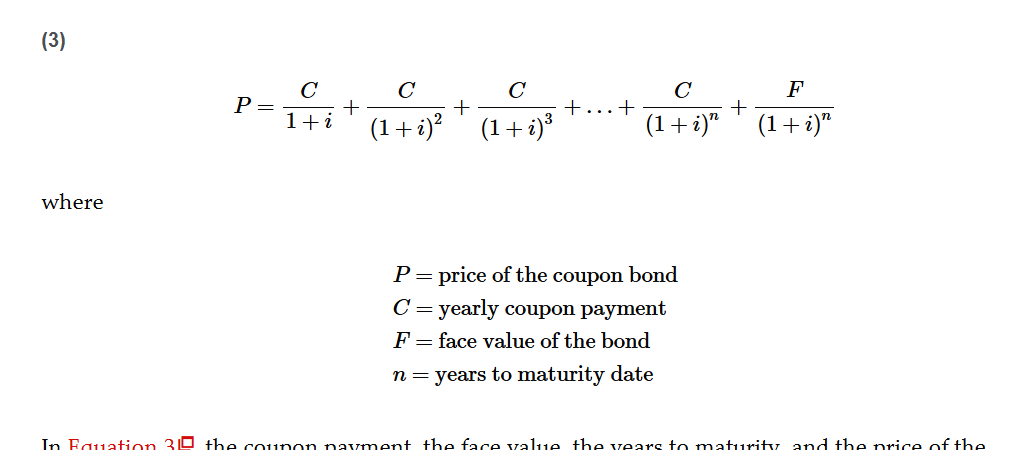

Coupon bond formula

Coupon Bond Important Facts

When the coupon bond is priced at its face value, the yield to maturity equals the coupon rate

The price of a coupon bond and the yield to maturity are negatively related

Bond Pricing

When price is above par (face) value

YTM or Current Yield < Coupon Rate

When price is equal to par (face) value

YTM or Current Yield = Coupon rate

When price is below par (face) value

YTM or Current Yield > Coupon Rate

Bond Price vs. Yield

Key Concept: There is an inverse relationship between bond prices and yields.

Price ↑ → Yield ↓

Price ↓ → Yield ↑

This is because:

If a bond pays a fixed amount in the future, paying more today reduces your return

Paying less today increases your return

Why does a discount bond always sell below par?

Because it pays no coupon; investors only get the face value at maturity

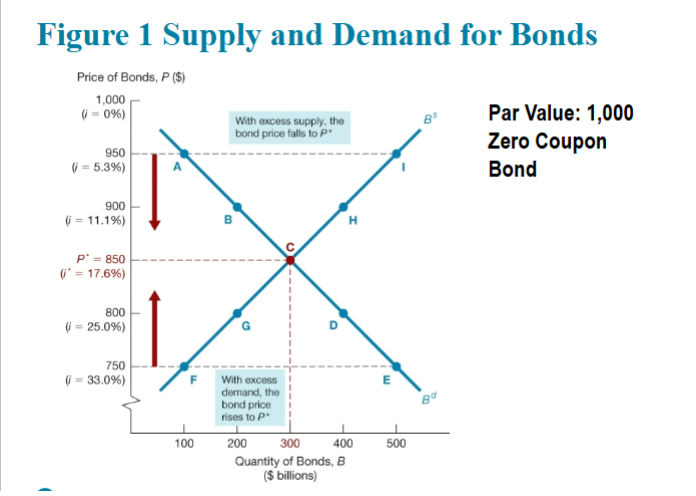

Figure 1 Supply and Demand for Bonds

Equilibrium in the bond market occurs at point C, the intersection of the demand curve Bd and the bond supply curve Bs. The equilibrium price is P* = $850, and the equilibrium interest rate is i* = 17.6%.

Theory of Portfolio choice

A theory that outlines how much of an asset people will want to hold in their portfolios, as determined by wealth, expected returns, risk, and liquidity.

The theory of portfolio choice provides a framework for deciding which factors will cause the demand curve for bonds to shift.

Theory of Portfolio Choice- What determines demand for an asset?

The quantity demanded of an asset is:

↑ Wealth → ↑ quantity demanded (positively related)

↑ Expected return (relative to alternatives) → ↑ quantity demanded (positively related)

↑ Risk (relative to alternatives) → ↓ quantity demanded (negatively related)

↑ Liquidity (relative to alternatives) → ↑ quantity demanded (positively related)

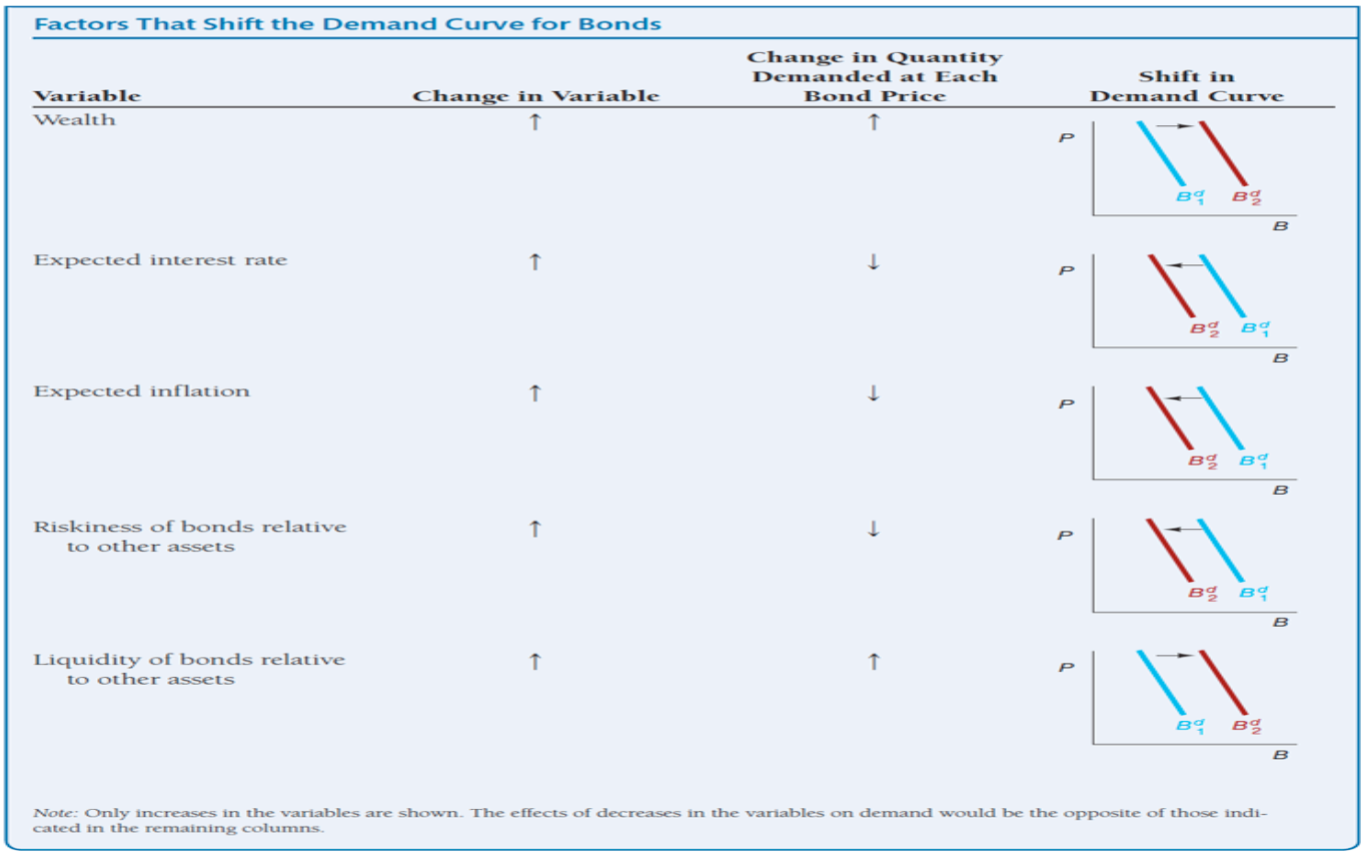

Shifts for the Demand of Bonds (Slide 15)

Interpretation:

Wealth ↑ → More funds available → Bond demand shifts right.

Expected interest rates ↑ → Future bonds become more attractive → Current bond demand shifts left.

Expected inflation ↑ → Bonds’ fixed future payments lose value → Demand shifts left.

Riskiness of bonds ↑ → Bonds become less attractive → Demand shifts left.

Liquidity of bonds ↑ → Bonds become easier to sell → Demand shifts right.

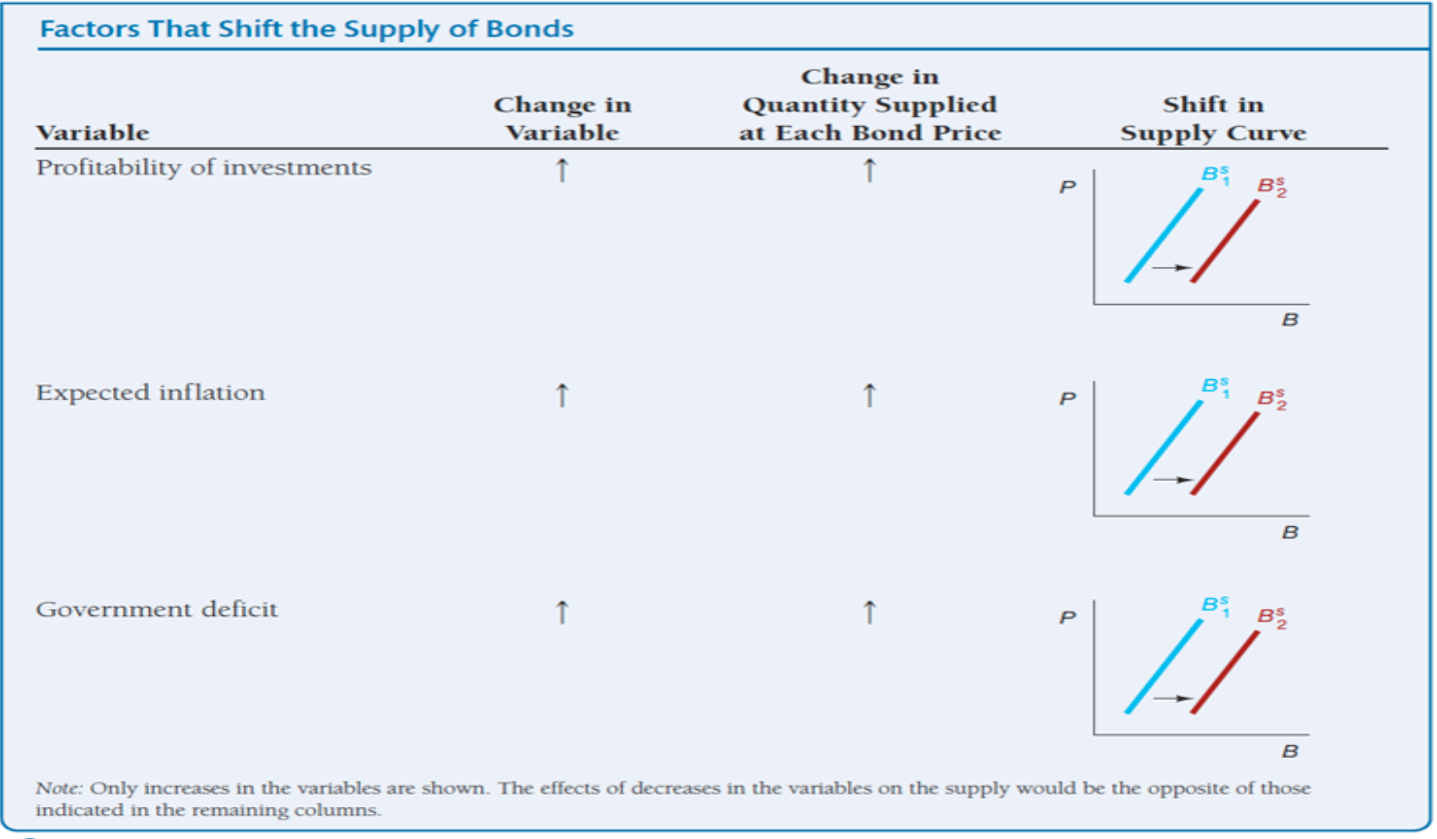

Shifts in the Supply for Bonds

Interpretation:

Profitability of investments ↑ → More borrowing to fund projects → Bond supply shifts right.

Expected inflation ↑ → Real cost of repaying loans falls → Incentive to borrow increases → Bond supply shifts right.

Government deficit ↑ → More government borrowing to cover the deficit → Bond supply shifts right.

YTM Recap

YTM is the rate of return that makes PV = Price

It’s just the discount rate that equalizes the bond price and the future payments

All YTM formulas come from the present value formula- nothing new to memorize

Why YTM Changes when Price Changes

Bond Price ↑ → YTM ↓

Bond Price ↓ → YTM ↑

Why? Because the future cash flows are fixed.

Example: If FV = $1,000 and you pay:

$900 → you earn more than the bond’s coupon → YTM ↑

$1,100 → you earn less → YTM ↓

Default

A situation in which the party issuing a debt instrument is unable to make interest payments or pay off the amount owed when the interest matures

default-free bonds

Bonds with no default risk, such as U.S. government bonds

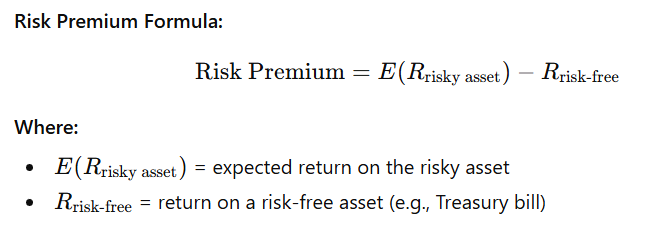

Risk premium

The spread between the interest rate on bonds with default risk and the interest rate on default-free bonds

The risk premium indicates how much additional interest people must earn to be willing to hold the risky bond.

A bond with default risk will always have a positive risk premium, and an increase in its default risk will raise the risk premium.

Risk Premium Formula

There are two determinants of the risk premium:

Default Risk

Higher default risk → higher risk premium

Liquidity

The less liquid a bond is, the higher the risk premium

Ex:

Bond A (Easily Traded)

Bond B (Hard to sell quickly)

→ Investors demand a premium for holding B

Expectations Theory

Core Idea: The interest rate on a long-term bond will equal an average of the expected future short-term interest rates.

“Long-term interest rates reflect the market’s expectations of future short-term interest rates”

What this theory assumes:

Bonds of different maturities are perfect substitutes (Investors don’t care about maturity- all that matters is expected return).

No maturity preference — only expected return matters

Why does Expectations theory matter?

It explains the shape of the yield curve (normal, flat, inverted).

If future short-term rates are expected to rise → yield curve slopes upward

If future short-term rates are expected to fall → yield curve slopes downward

If short-term rates are expected to stay constant → yield curve is flat

Segmented Markets Theory Formal Definition

Formal Definition: A theory of term-structure that sees the markets for different maturity bonds as completely separated and segmented, so that the interest rate on bonds of a given maturity is determined solely by supply of and demand for bonds of that maturity.

“Interest rates for bonds of different maturities are determined independently; bonds of different maturities are not substitutes.”

Segmented Markets Theory Core Idea

Core Idea:

Bonds of different maturities are not substitutes

Each maturity is its own isolated market

Why?

Investors have strong maturity preferences- usually:

Banks prefer short-term

Pension funds prefer long-term

Insurance Companies prefer long-term

Money market funds prefer very short-term

Segmented Markets Theory on Interest Rates and Yield Curve

What this theory says causes different interest rates:

Interest rates for each maturity depend on supply and demand in that specific segment, NOT on expectations of future rates.

What it implies about the yield curve:

Typically upward sloping, because investors prefer short-term bonds, so long-term bonds must pay higher rates to attract buyers

Preferred Habitat Theory Formal Definition

Formal Definition: A theory that holds that the interest rates on a long-term bond is equal to an average of the short-term interest rates expected to occur over the life of the long-term bond, plus a positive term premium.

This is basically a mix between Expectations Theory and Segmented Theory

“Investors prefer bonds of specific maturities (habitats) but will hold others if compensated with a term premium.”

Preferred Habitat Theory Core Idea

The Core Idea:

Investors prefer certain maturities (habitats) but they are willing to move to other maturities if they are paid a risk premium.

Long-term bonds typically must offers:

Higher yields

A term premium

Because investors prefer short-term bonds

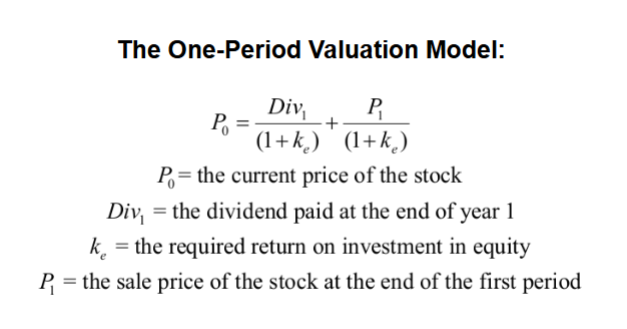

The One-Period Valuation Model

Idea: Price today = discounted value of what you get next period: the dividend you receive plus the price you can sell for next period.

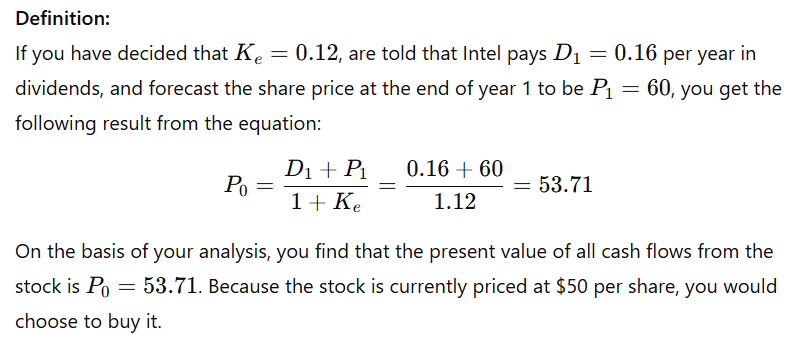

One-Period Valuation Model — Example

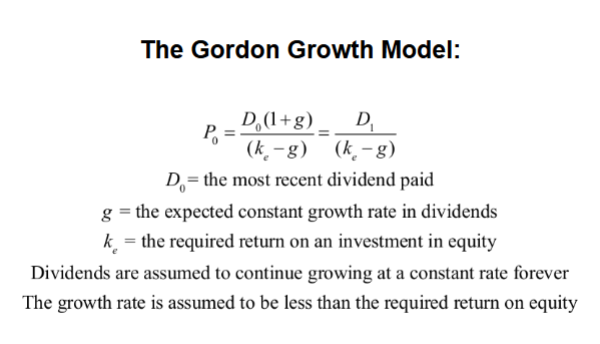

Gordon Growth Model

Idea: The firm pays dividends forever and those dividends grow at a constant rate g. Value = present value of infinite growing stream of dividends.

D1- Dividend next year (NOT this year, that’s D0)

The Gordon Growth Model Assumes:

Dividends grow at a constant rate forever

The growth rate is assumed to be less than the required return on equity, Ke

If g is bigger than Ke, the model breaks — so the model only works when: r > g

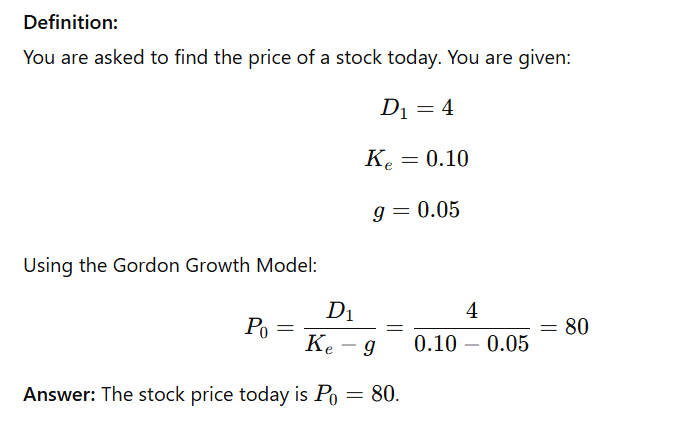

Gordon Growth Model — Example

Key Points about Financial Structure Throughout the World- Chapter 8, Slide 7

Stocks are not the main source of funding — most businesses in these economies rely on debt, not issuing equity.

Direct finance is rare — few firms issue marketable debt or equity; indirect finance dominates

Banks and financial intermediaries are crucial — they channel savings into business investment

Financial regulation is heavy — even in developing countries, the financial sector is highly controlled

Access is unequal — only large, well-established corporations can easily access securities markets

Collateral is very important — lenders require collateral to reduce risk

Debt contracts are complex — restrictive covenants are included to limit risky behavior by borrowers

Key Points about Financial Structure Throughout the World- Chapter 8, Slide 7

Why it matters:

In countries with weaker institutions, poor property rights, or weak legal enforcement:

Collateralized debt is more common because lenders need security

Intellectual property and enforcement contracts are less reliable, so direct investment is riskier

Indirect finance (banks) is more reliable than trying to sell stocks or bonds in an underdeveloped market.

Collateralized (Secured) Debt

A loan backed by collateral. If the borrower defaults, the lender has a legal claim to the asset used as collateral.

Lower risk for lender

Lower interest rate

Examples: mortgages, auto loans

Uncollateralized (Unsecured) Debt

A loan not backed by collateral. If the borrower defaults, the lender has no specific asset claim.

Higher risk for lender

Higher interest rate

Examples: credit cards, student loans

Asymmetric Information

A situation in which one party in a financial transaction has more or better information than the other.

Effect: Can lead to inefficient outcomes, such as higher-risk taking or the wrong allocation of resources.

Example: Borrowers know more about their ability to repay a loan than the lender does.

Adverse Selection

Occurs before a financial transaction, when the party with more information (usually the borrower) is likely to engage in riskier behavior than the lender expects.

Example: High-risk borrowers are more likely to seek loans, but the lender cannot tell the difference upfront.

Tools to mitigate adverse selection:

Private production of information — credit checks, background reports, due diligence

Government regulation — disclosure requirements, reporting standards

Financial intermediation — banks can screen borrowers better than individual investors

Collateral and net worth- borrowers with more to lose (net worth or collateral) are less likely to default.

Moral hazard

Occurs after a financial transaction when the borrower might engage in riskier behavior because the lender bears part of the cost.

Example: A company borrows money and then invests in high-risk projects because the lenders loss is limited to the loan.

Mitigation: Monitoring, restrictive covenants, collateral, financial intermediated, regulatory oversight.

Principal-Agent Problem

A type of moral hazard that occurs in equity contracts.

Key Idea: The agent (e.g., company management) may act in their own interest rather than the principal’s (e.g., shareholders) interest.

Mitigation: Monitoring, incentives tied to performance, regulation, financial intermediation.

Total Reserves

The deposits that a bank has at the Federal Reserve Bank plus its cash on hand (cash in the vault)

Formula:

Total Reserves = Deposits at Federal Reserve + Cash on Hand

Required Reserves

The minimum amount of reserves a bank must hold.

Formula:

Required Reserves = Required Reserve Ratio X Checkable Deposits

Required Reserve Ratio

The percentage of its total deposits that a bank must keep as reserves at the Federal Reserve

Required Reserve Ratio = Required Reserves / Checkable Deposits

Excess Reserves

Reserves above what is legally required. Banks lend only from excess reserves.

Formula:

Excess Reserves = Total Reserves - Required Reserves

Gap Analysis

Purpose: Measures how bank profits change when interest rates change

Formula:

GAP = RSA - RSL

Δ Profit = (Rate Sensitive Assets - Rate Sensitive Liabilities) X Δ Interest Rates

Where:

RSA: Assets whose interest can change within the time period

RSL: Liabilities whose interest can change within the time period

Δ Interest Rates: Change in interest rates (expressed as a decimal)

Gap analysis interpretation

If GAP > 0 (RSA > RSL): Bank profits increase when interest rates rise

If GAP < 0 (RSA < RSL): Bank profits decrease when interest rates rise

Gap Analysis Example (Slide 38):

Suppose that you are the manager of a bank that has $15 million of fixed-rate assets, $30 million of rate-sensitive assets, $25 million of fixed-rate liabilities, and $20 million of rate-sensitive liabilities. Conduct a gap analysis...

For the bank and show what will happen to bank profits if interest rates rise by 5 percentage points.

Step 1: Calculate GAP

GAP = RSA - RSL

30 - 20 = + 10 million

Step 2: Apply Formula

Δ Profit = 10 m X 0.05 = .5 million

Final Answer:

GAP = +$10 million

Because GAP > 0, the bank benefits when interest rates rise

Profits increase by 500,000 when interest rates rise by 5%.

Duration Analysis

Goal: To measure how a bank’s net worth changes when interest rates change

Duration = how sensitive the value of an asset or liability is to interest rate changes

A longer duration = more interest rate risk

A shorter duration = less interest rate risk

Duration Analysis Formula

Formula:

%Δ in market value of the securities = (percentage point Δ in interest rates) X (duration in years)

Simplified Formula:

%Δ MV = Δ i X Duration

Where:

%Δ MV = Percentage change in market value of the asset or portfolio

Δ i = Change in interest rate (in percentage points)

Duration = duration of the asset or portfolio (in years)

Key note:

When interest rates rise, bond prices fall

When interest rates fall, bond prices rise

Duration Analysis

Example 1: Interest rates rise (negative effect on bond price)

Example 1: Interest rates rise (negative effect on bond price)

Bond value: $1,000

Duration: 5 years

Interest rate change: +2% (0.02)

%Δ Price = 5 X 0.02 = 0.10

Since rates rise, it is -10%

New bond price = $1,000 X (1 - 0.10) = $900

When interest rates rise, bond prices fall

Duration Analysis

Example 2: Interest rates fall (positive effect on bond price)

Example 2: Interest rates fall (positive effect on bond price)

Bond value: $1,000

Duration: 5 years

Interest rate change: -2% (-0.02)

%Δ Price = 5 X (-0.02) = -0.10

Since rates fall, it is 10%

New bond price = $1,000 X (1 + 0.10) = $1,100

When interest rates fall, bond prices rise

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

Government agency that insures bank deposits.

Why it was created:

To prevent bank panics and contagion effects — where the failure of one bank causes people to rush and withdraw from other banks.

Ensures stability in the banking system

Currently insures deposits up to $250,000 per depositor per bank.

Payoff Method

FDIC closes the bank and pays depositors directly up to the insurance limit.

Quick, but can be costly for depositors with uninsured deposits.

Purchase and Assumption Method

Another bank buys the bank’s assets and assumes its deposits.

Usually more costly for the FDIC but keeps the bank running and avoids panic.

Chartering

The process of approving a proposal to open a new bank.

Types:

State-chartered banks: regulated primarily by the state

Federal-chartered banks: regulated by Federal authorities (OCC)

Significance:

Prevents adverse selection — only financially sound institutions are allowed to operate

Banks are regularly examined to prevent moral hazard (taking on too much risk because they know they have government support).

Examination Process for Banks - CAMELS

Capital Adequacy — enough equity to cover risks

Asset Quality — how risky are loans/investments

Management — competent leadership

Earnings — profitability

Liquidity — ability to meet withdrawals

Sensitivity to market risk — e.g., interest rate change

Periodic “call reports” are submitted to monitor these factors.

Restricted Covenants

Clauses in bank contracts that restrict certain actions by the bank or borrowers to reduce risk.

Example: limiting the types of loans a bank can make or the size of investments.

Purpose: Reduce moral hazard by making sure the bank doesn’t take excessive risks.

Glass-Steagall Act

1933 law that separated commercial banking (taking deposits, making loans) from investment banking (underwriting, trading securities).

Repealed in 1999, which allowed universal banking. Restrictions on branching and competition were also lifted in 1994.

Purpose of act:

Reduce moral hazard and risk-taking by commercial banks.

Disadvantages of act:

Reduced competition can mean higher consumer charges and less efficiency

Financial Innovation

Definition:

Creation of new financial products or practices that bypass regulations or improve efficiency

Significance:

Can improve access to funds, increase liquidity, or spread risk.

But it can also increase systemic risk, as seen in the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

Examples: mortgage-backed securities, derivatives, credit default swaps.

End of Unit 1 and 2

Good Job

Permanent Life Insurance

Key Features:

Covers you for your entire life (as long as premiums are paid).

Has a savings/investment component called cash value.

Premiums are higher because you’re building savings + insurance

Types:

Whole life — fixed premiums, guaranteed cash value

Universal life — flexible premiums

Variable life — cash value invested in risky assets (stocks)

Why someone buys it: long-term protection + investment savings

Term Life Insurance

Key Features:

Covers you for a specified period only (ex: 10, 20, 30 years)

No savings or cash value

Much cheaper than permanent life insurance

Pays out only if you die during the term

Why someone buys it: inexpensive, straightforward protection

Property and Casualty Insurance

Covers cars, homes, businesses, liabilities, etc.

Must hold more liquid assets than life insurers.

Why? — People file claims frequently and unpredictably (car accidents, fires, etc.).

Reinsurance

Insurance for insurance companies

They buy this to protect themselves from large unexpected losses

Adverse Selection Problem in Insurance

People with the highest risk are the most likely to buy insurance

Examples:

Unhealthy people try harder to buy health insurance

Bad drivers want more auto coverage

Older or sick people want life insurance more

Insurance companies fight this by:

Medical exams

Driving record checks

Charging risk-based premiums

Deductibles

Exclusions (ex: no coverage for pre-existing damages)

Slide 14 Application:

Paul’s car slid off the road, causing $3,000 in damage to his car. He was also treated for minor injuries, costing $1,400. His car insurance has a $300 deductible, after which the full loss is paid. His health insurance has a $100 deductible and covers 75% of medical cost. What were Paul’s out of pocket costs for the accident?

Step 1: Deductible paid by Paul

$1,400 - $100 = $1,300 left

Step 2: Paul’s portion of the remaining 25%:

25% of $1,300 = $325

Out of pocket medical cost = $100 + $325 = $425

Total Out-of-Pocket

Car: $300

Medical: $425

Total Paul Pays: $725

Monoline Insurance

Insurance company that only sells one type of i