Projective Geometry

1/20

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

21 Terms

What is classical geometry and why is it problematic in algorithms?

In classical geometry, we represent points as (x, y) coordinates and lines using equations like slope-intercept form or two points.

The problem is that many geometric operations create special cases. For example, when checking line intersections, we must separately handle parallel lines, vertical lines, or division by zero.

This makes implementations technical, error-prone, and messy, especially in programming contests.

👉 Motivation: we want a geometry model with fewer special cases.

Why do we introduce projective geometry?

Projective geometry is introduced to simplify geometric reasoning.

It removes annoying special cases like:

parallel lines never intersecting,

points “at infinity” not being representable.

In projective geometry:

every two lines intersect,

every two points define a line.

This leads to cleaner formulas and simpler algorithms.

What is the difference between parallel and central projection?

Parallel projection simply drops the

zcoordinate:

(x, y, z) → (x, y, 0)

This looks unrealistic (objects don’t get smaller with distance).

Central projection divides by

z:

(x, y, z) → (x/z, y/z, 1)

This mimics how we see in real life: far objects look smaller.

Problem: what if z = 0?

This leads to the idea of points at infinity.

What is the projective plane RP²?

The projective plane RP² is defined as all non-zero vectors in R³, where vectors that differ only by scaling are considered the same point.

Formally:

(x, y, z) ∼ (λx, λy, λz), λ ≠ 0

So a projective point is not one coordinate, but an entire line through the origin in 3D space.

What are homogenization and dehomogenization?

Homogenization embeds 2D points into projective space:

(x, y) → (x, y, 1)

Dehomogenization goes back to 2D (only if

z ≠ 0):

(x, y, z) → (x/z, y/z)What is a point at infinity?

A point at infinity is a projective point where:

z = 0

Intuition:

Take a normal point

(x, y)Scale it more and more:

(λx, λy)In projective space this converges to

(x, y, 0)

So points at infinity represent directions, not locations.

How are lines represented in projective geometry?

A line in projective space is represented by a vector:

(a, b, c)

A point (x, y, z) lies on the line if:

ax + by + cz = 0

Important:

Scaling doesn’t matter:

(a, b, c) ∼ (λa, λb, λc)

👉 Points and lines are symmetric in projective geometry.

What is the line at infinity?

In projective geometry, there is one special line called the line at infinity.

It consists of all points with z = 0.

It is represented by:

(0, 0, 1)

A point (x, y, z) lies on this line iff z = 0, so:

all points at infinity lie on this line,

no normal 2D point lies on it.

👉 Intuition: the line at infinity collects all directions.

Why is the cross product important in projective geometry?

The cross product gives a vector that is perpendicular to two given vectors.

In projective geometry:

points and lines are both vectors,

“being perpendicular” corresponds to incidence (point lies on line).

👉 This is why one operation (×) can compute both:

line through two points,

intersection of two lines.

How do we compute intersections and connecting lines in RP²?

There are two golden rules:

1⃣ Intersection of two lines

If l1 and l2 are lines, then their intersection point is:

p = l1 × l2

2⃣ Line through two points

If p1 and p2 are points, then the line through them is:

l = p1 × p2

No special cases.

No “parallel vs non-parallel”.

It always works in projective geometry.

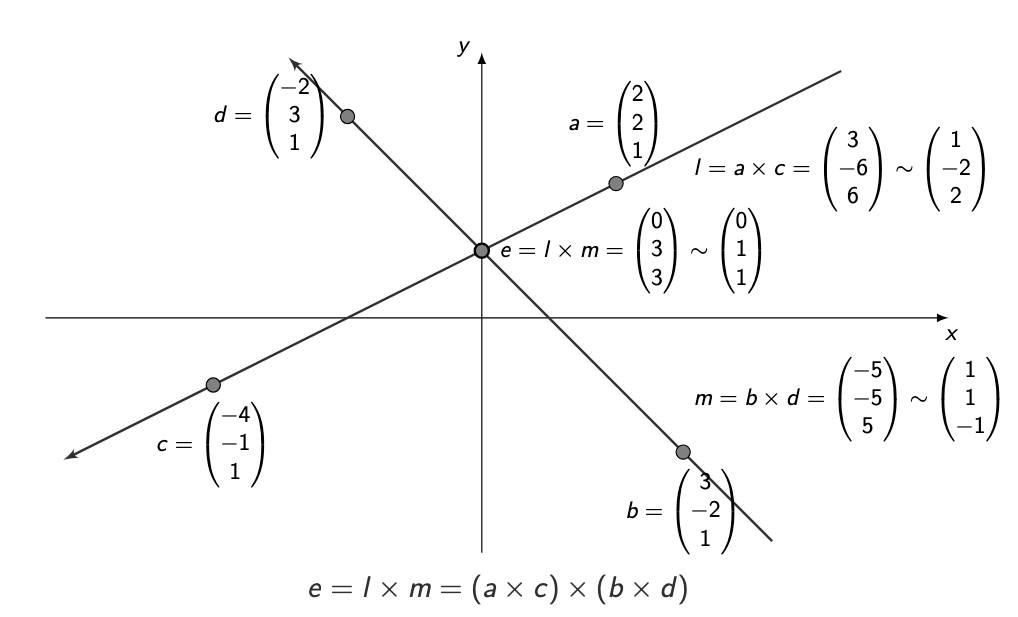

How does the intersection-of-diagonals example work?

Given four points a, b, c, d:

Compute diagonal lines:

l = a × c

m = b × d

Compute their intersection:

e = l × m

This point e is the intersection of the diagonals, even if:

What geometric properties change in projective geometry?

In projective geometry, the following always holds:

Every two distinct points define a line

Every two distinct lines intersect

This is different from Euclidean geometry, where:

parallel lines never intersect.

Here, parallel lines intersect at a point at infinity.

What happens when we intersect two parallel lines?

ake two parallel lines l and m.

In Euclidean geometry, they don’t intersect.

In projective geometry:

p = l × m

The result is a point:

(x, y, 0)

So:

the intersection exists,

it is a point at infinity,

it represents the direction of the parallel lines.

Important:

All parallel lines with the same direction intersect at the same point at infinity.

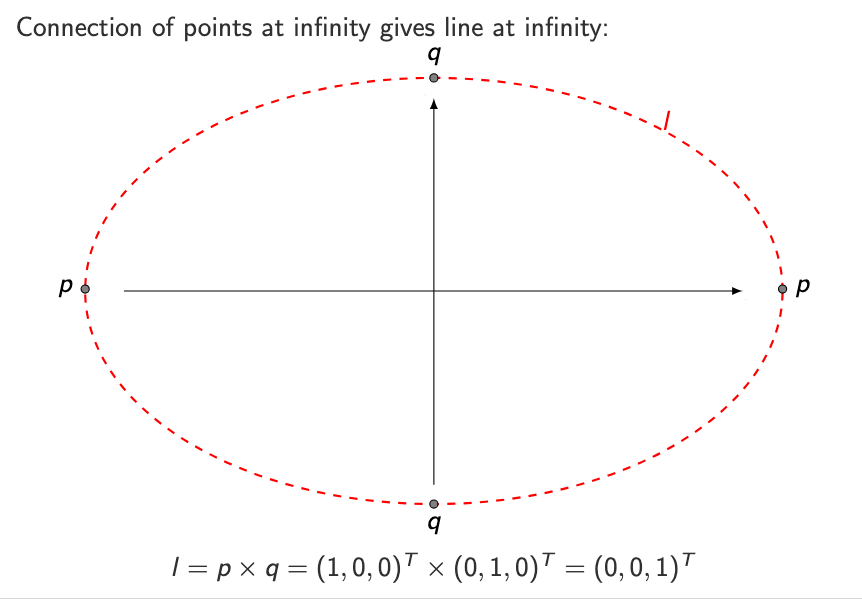

What happens if we connect two points at infinity?

If you take two different points at infinity and compute:

l = p × q

You get:

(0, 0, 1)

This is the line at infinity.

So:

points at infinity lie on the line at infinity,

the line at infinity connects all directions.

How do we construct a line parallel to a given line through a point?

Given:

a line

l,a point

p(not onl).

Steps:

Compute the point at infinity of

l:

q = l × (0, 0, 1)

Connect

pwith that point:

m = p × q

Result:

mis parallel toland passes through

p.

How do we construct a perpendicular line using projective geometry?

Steps:

Find direction of line

las a point at infinity:

q = l × (0, 0, 1) = (x, y, 0)

Compute the orthogonal direction:

q⊥ = (y, −x, 0)

Connect with point

p:

m = p × q⊥

Result:

mis perpendicular toland goes through

p.

How do we project a point onto a line?

To project point p onto line l:

Construct the perpendicular line

mthroughpCompute the intersection:

r = m × l

Point r is the projection of p onto l.

👉 Projection = perpendicular + intersection.

Why do we use projective transformations instead of Euclidean ones?

n Euclidean geometry, transformations like:

rotation,

translation,

are described by different formulas, and combining them is awkward.

In projective geometry, all transformations are matrix multiplications using homogeneous coordinates:

(x, y, 1) → M · (x, y, 1)

This allows:

easy concatenation,

a uniform representation,

and no special cases.

What are affine transformations in projective geometry?

Affine transformations are transformations that preserve parallel lines, such as:

translation,

scaling,

rotation,

mirroring,

shearing.

They are represented by matrices of the form:

| a b c |

| d e f |

| 0 0 1 |

Important:

det(M) ≠ 0

👉 All affine transformations are projective, but not all projective ones are affine

How are projective transformations characterized?

A key theorem:

Every transformation that preserves collinearity is projective.

Also:

A projective transformation is uniquely determined by four non-collinear points and their images.

This is crucial for computing transformations from data.

How do we compute a projective transformation matrix?

Given four points a, b, c, d and their images a′, b′, c′, d′:

We solve:

M · a = λa a′

M · b = λb b′

M · c = λc c′

M · d = λd d′

Unknowns: entries of

Mand theλsMis defined up to scale, so oneλcan be fixedresults in a linear system

👉 This is a standard linear algebra problem.