physl cardiovascular

1/51

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

52 Terms

Hemodynamics

The study of blood flow and relates Ohm’s law to fluid flow, looking at the relationship between blood flow, blood pressure, and resistance to blood flow

F = ∆P/R. F = flow, ∆P = pressure difference between two fixed points (P1 and P2), R = resistance to flow.

Blood flow is related to the pressure difference between the two fixed points

and inversely proportional to the resistanceResistance is defined as the friction that impedes flow, or how difficult it is for

blood to move between 2 points at any given pressureBlood always flows from a region of higher pressure to a region of lower pressure.

The pressure difference between 2 points provides the driving force NOT absolute pressure.There must be a differece or flow is 0ml/min

To have flow, the pressure difference must overcome resistance to flow (∆P > R)

Our bodies can change factors that affect blood flow: by changing resistance (of blood vessels, in particular arterioles) blood flow can be altered

Hydrostatic pressure → blood hydrostatic pressure is the pressure that the volume of blood within our circulatory system exerts on the walls of the blood vessels that contain it

What determines resistance to blood flow?

Resistance can be calculated numerically from the formula F=delta P/R, but it cannot be measured as it is determined by several factors

Factors that determine resistance to blood flow: viscosity of the blood, length of

the blood vessel, and diameter of the blood vesselViscosity: the friction between molecules of a flowing fluid

- Blood contains many molecules and the formed elements in blood (red blood

cells, white blood cells, and platelets). Interaction between different components in blood produces friction which contributes to resistance to blood flow.

- Hematocrit (the number of red blood cells in the blood) affects viscosityBlood vessel length and diameter affect the amount of vessel wall that the blood is in contact with

- Friction develops between the moving blood and the stationary vessel walls

- The greater the contact, the greater the friction produced and the greater the resistance to flow

- A vessel with a longer length will produce more friction than a shorter vessel

- Vessel diameter can change by constriction or dilation of the vessel

Blood flows through vessels in concentric layers

In smaller diameter vessels, more blood is in contact with the vessel wall, as there are less concentric layers of blood flowing through the smaller vessel; this generates more friction as the blood moves through the vessel

In larger diameter vessels, some blood will be in contact with the vessel walls, but many of the layers will move through the vessel without contacting the vessel wall; friction in the larger diameter vessel will be less than that produced in the smaller diameter vesselPoiseuille’s equation: R = 8Lη/ π r^4

- R = the resistance to blood flow, η =the blood viscosity, L = the vessel

length and r= the inside radius of the vessel

- The factor with the greatest effect on resistance is the diameter or the radius of the vessel as r is raised to the 4th power

- Very small changes in vessel diameter therefore lead to large changes in resistance; our bodies are able to alter vessel diameter by constricting and relaxing vascular smooth muscle in the wall of the blood vessels and change the resistance to blood flow in our bodies

Functions & components of cardiovascular

To deliver oxygen and nutrients and remove waste products of metabolism

Fast chemical signaling to cells by circulating hormones or neurotransmitters

Thermoregulation

Mediation of inflammatory and host defense responses against invading microorganisms

Heart, blood vessels and blood

Vessels: arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules and veins

Arterioles: small branching vessels with high resistance

Capillaries: transport of blood between small arteries and veins; exchange of materials between blood and cells in the body

All arteries carry blood away from the heart. All veins carry blood back to the heart

Closed circulatory system allows for greater pressures to be generated when the heart contract

Anatomy of the heart

Heart has 4 chambers: 2 atria and 2 ventricles

Atria: Thin-walled, low pressure chambers. Receive blood returning back to the heart

Ventricles: Thick-walled chambers (thicker than atria). Responsible for the forward propulsion of blood when they contract

Apex of heart is the lowest superficial surface of the heart

Base of heart is the upper surface of the heart where the blood vessels attach

Septa: divides left and right sides of the heart. Muscular walls

- Interatrial septum → separates left and right atria

- Interventricular septum → separates left and right ventricles

- Allows heart to function as a dual pump; Left side pumps highly oxygenated blood to systemic circuit (body). Right side pumps poorly oxygenated blood to pulmonary circuit (lungs).

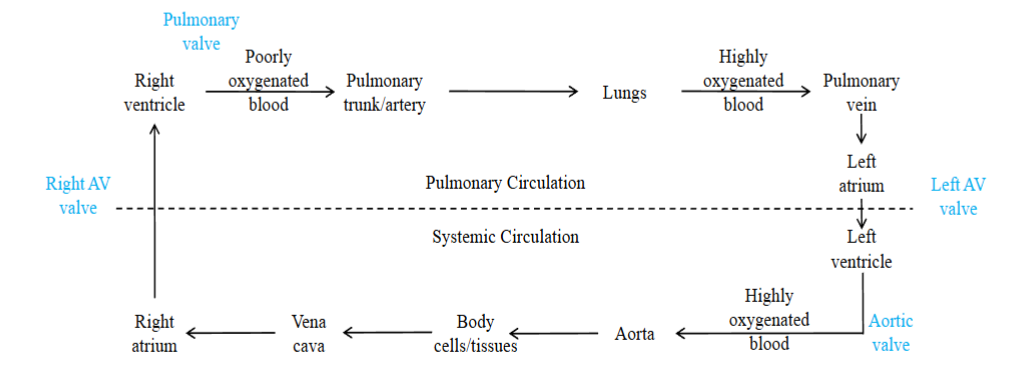

Path of blood flow

The circulatory system can be divided into two serial (in sequence) circuits: the pulmonary circulation and the systemic circulation

Pulmonary circuit: carries blood to and from the gas exchange surfaces of the lungs; blood entering the lungs is poorly oxygenated; once blood enters the lungs, oxygen diffuses from the lung tissues to the blood; blood leaving the lungs is highly oxygenated

Systemic circuit: transports blood to and from the rest of the body; blood

entering the body tissues is highly oxygenated; oxygen diffuses from the blood

to the interstitial fluid surrounding the tissue cells; blood leaving the tissues is poorly oxygenatedThe left side of the heart receives blood from the pulmonary circulation and pumps it to the systemic circulation. The right side of the heart receives blood from the systemic circulation and pumps it to the pulmonary.

Blood moves from the pulmonary circuit to the heart and then to the systemic circuit before returning back to the heart: it moves in series

Arteries → carry blood away from heart; most carry highly oxygenated blood except pulmonary trunk and pulmonary arteries which carry poorly oxygenated blood to lungs

Veins → carry blood to the heart; most carry poorly oxygenated blood back to the heart except pulmonary venules and pulmonary veins which carry highly oxygenated blood back to the left atrium from the lung

Parallel flow to most organs; this means that each organ is supplied by a different artery and therefore its blood flow can be independently regulated

- An exception is the liver; it receives blood flow in parallel and in seriesCardiovascular system can not only increase the rate of blood flow, but it can also alter the distribution of our blood flow, depending on the needs of your body, increasing blood flow to areas that need more blood and decreasing blood flow to areas that do not need as much blood at that time

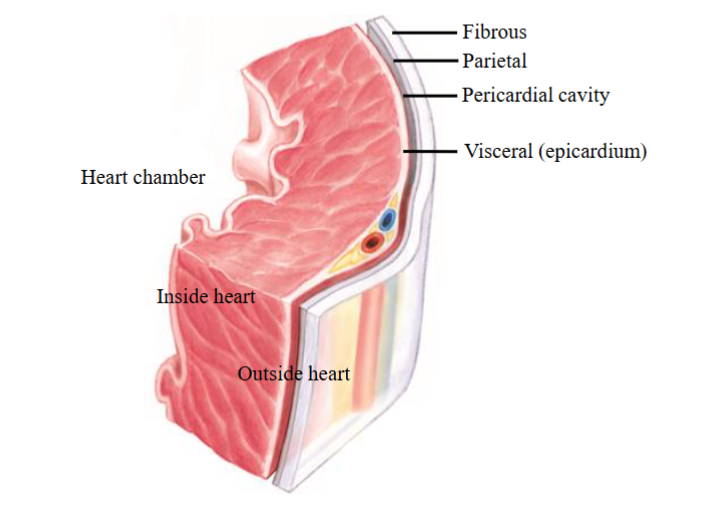

Functions & structure of pericardium

Pericardium → a fibrous sac surrounding the heart and the roots of the great blood vessels leading into and out of the heart

Functions:

- Stabilizes the heart in the thoracic cavity

- Provides protection to the heart by physically surrounding it

- Reduces friction as the heart beats by secreting the pericardial fluid

- Limits overfilling of the heart chambers3 layered sac: fibrous pericardium, parietal pericardium and visceral pericardium

Fibrous pericardium: outer layer of the pericardial sac; provides protection for

the heart and stabilizes the heart in the thoracic cavity by attaching to structures in the chest; holds the heart in place; limited distensibility which prevents the sudden, rapid overfilling of the heartParietal pericardium: part of the serous pericardium; lies underneath the

fibrous pericardium and is attached to itVisceral pericardium: part of the serous pericardium; innermost layer of the

pericardial sac, and is also called the epicardium when it comes into contact

with the heart musclePericardial cavity → separates the parietal pericardium from the visceral

pericardium; both parietal and visceral pericardium secrete fluid which

decreases friction between pericardial membranes as heart beatsSerous layer → a layer composed of cells that secrete a fluid

Pericarditis: an inflammation of the pericardium caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, trauma or malignancy; leads to fluid accumulation in the pericardial cavity

Cardiac tamponade: compression of heart chambers due to excessive accumulation of pericardial fluid; heart's movement is limited and heart chambers cannot fill with adequate amount of blood (ie. a decrease in ventricular filling)

Heart wall

Heart wall has 3 layers:

- Epicardium: also called visceral pericardium. Layer immediately outside the heart muscle and covers the outer surface of the heart; connective tissue attaches it to the myocardium; functions as a protective layer for the heart

- Myocardium: the muscular wall of the heart and lies underneath the

epicardium. Contains muscle cells or myocytes which contract and relax as the heart beats, nerves, and blood vessels

- Endocardium: innermost layer of the heart wall. Lines heart cavities and the heart valves; a thin layer of endothelium which is continuous with the endothelium of the attached blood vesselsThe entire circulatory system (heart chambers, heart valves and blood vessels) is lined by endothelium which forms an interface between the blood and the heart chamber or blood vessel wall, providing a smooth surface for blood to flow over

3 layers are found in both atria and both ventricles. Do show variation between the different chambers (the ventricles have a thicker myocardium than the atria; the left ventricle has a thicker myocardium than the right ventricle)

Cardiac muscle cells

Myocytes = cardiac muscle cells. Branched or Y shaped. Joined longitudinally or end to end to adjacent myocytes

- Allows for greater connectivity in the heart,

- Striated or stripped appearance (Actin and myosin)

- A single centrally located nucleus

- Rich in mitochondria (Provide ATP for the muscle cells to contract)Adjacent cells are held together by intercalated disk

- The membranes of 2 different myocytes are closely opposed and very intertwined at their region of attachment

- 2 types of specialized intercellular junctions at intercalated

disks: desmosomes and gap junctionsDesmosomes: Adhering junctions that hold cells together in tissues subject to considerable mechanical stress or stretching.

- Mechanically couple one heart cell to another

- Proteins involved: cadherins, plaques, intermediate filaments. Cadherins from one cell attach to cadherins from another cellGap Junctions: Communicating junctions

- Electrically couple heart cells, allowing ions to move between cells

- Important for spread of action potential

- Proteins involved: connexonsMuscle fibers are arranged spirally around the heart chambers. Important for emptying blood into arteries when ventricles contract.

4 valves of the heart

Atrioventricular (AV) valves: found between the atria and the ventricles on

both the left and right sides of the heart.

- AV valve located between the left atrium and left ventricle is the bicuspid or mitral valve

- AV valve located between the right atrium and the right ventricle is the tricuspid valve.Semilunar (arterial) valves: found between the ventricles and the arteries into

which the ventricles pump their blood

- Valve between the left ventricle and the aorta is the aortic valve

- Valve between the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk is the pulmonary valveValves: Made of fibrous tissue (collagen) covered by endothelium. Valve flaps are also called leaflets or cusps.

Valve rings: Made of cartilage. These are what the valves attach to

How valves function

Function of the heart valves? Ensure unidirectional flow of blood through the heart. Important so that blood flowing out of heart does not mix with new

blood coming into the heartThe valves open and close passively due to differences in pressure or pressure gradients

- Energy is not expended to open or close a valve, do not require muscles to open or close them.

- A forward pressure gradient opens a one way valve; a backwards pressure gradient closes

- Valves normally do not open in the opposite directionAtrioventricular (AV) Valves: Found between the atrium and the ventricle

- Prevent the backflow of blood into the atrium when the ventricle contracts

- When the pressure in the atrium exceeds the pressure in the ventricle, the AV valve will open, allowing blood to flow from the atrium into the ventricle so that the ventricle will fill with blood

- When the ventricle contracts and achieves a pressure greater than the pressure in the atrium, the valve will shut, preventing the backflow of blood from the ventricle into the atrium

- Tricuspid valve: AV valve located between the right atrium and the right ventricle; consists of three cusps or leaflets attached at the circumference to the valve rings

- Bicuspid or mitral valve: AV valve located between the left atrium and the left

ventricle; consists of two cusps or leaflets attached at the circumference to the valve rings

- Each AV valve is part of an AV valve apparatus, which consists of the cusps or leaflets of the valve, chordae tendineae and papillary musclesArterial (Semilunar) Valves: Found between the ventricle and the artery into which the ventricle ejects its blood

- 3 leaflets or cusps (left and right semilunar valves)

- Pulmonary valve: valve found between the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk

- Aortic valve: valve found between the left ventricle and the aorta

- Do not have chordae tendineae or papillary muscles (no valve apparatus associated with these valves)- The pressure pushing back against the valve from the artery is not high enough to force the valve to evert or open backwards into the ventricle, as the artery does not contract

- Open when the pressure in the ventricle is greater than that in the artery into

which the ventricle ejects its blood

- When the ventricle begins to relax, the pressure in the ventricle will decrease; when the pressure in the ventricle falls below the pressure in the artery, the

semilunar valve will close, preventing the backflow of blood from the artery into

the ventricle

- Semilunar valves open/close due to pressure differences across the valve; there are no muscles or energy expended to open/close these valves

Anatomy & function of AV valve apparatus

The edges of the AV valve leaflets are attached to tough, thin fibrous cords of

tendinous-type tissue called chordae tendineae

- The chordae tendineae extend from the edges of the leaflets and attach to

papillary musclesPapillary muscles: cone shaped muscles that protrude from the inner surface

of the ventricular walls

- Do contract, and when they contract they pull on the chordae tendineae to become tight (taut). This holds the valve in its closed position.

When the left ventricle is relaxed:

- AV or bicuspid valve is open and the semilunar or aortic valve is closed

- Papillary muscles are also relaxed and chordae tendineae are slack or have low tension

- When the bicuspid valve is open, blood can flow from the left atrium into the left ventricle; the ventricle fills with blood as the aortic valve is closed; blood

enters the ventricle but cannot leaveWhen left ventricle has begun to contract:

- The ventricle will squeeze its volume of blood as it contracts, increasing pressure inside the ventricle

- As the pressure in the ventricle rises above the pressure in the atrium, blood is

pushed back towards the bicuspid valve; but the increased pressure causes the

bicuspid valve to close as there is a greater pressure in front of this valve

- Closing of the bicuspid valve prevents the backflow of blood into the atrium as

the ventricle is continuing to contract

- The papillary muscles also contract when the ventricle contracts. This pulls the chordae tendineae downward or taut; chordae tendineae have tension

- Pulling of the chordae tendineae by the papillary muscles keeps the AV valve in a closed position in the face of a strong backward pressure gradient from the ventricle contracting

- The AV valve apparatus keeps the AV valves from opening backwards into the atrium

- If the AV valves did evert, blood would flow the wrong way from the ventricle to the atriumImportant: contraction of the papillary muscles does not open or close the valves; the valves open and close passively due to pressure differences across the valves

As the pressure in the ventricle continues to increase as the ventricle continues to contract, the pressure in the ventricle will eventually exceed the pressure in the aorta, opening the aortic valve, allowing blood to flow out of the ventricle; this is a forward pressure gradient

Cardiac skeleton

The fibrous skeleton of the heart

Made of dense connective tissue

Includes the heart valve rings and the dense connective tissue between the heart valves

Functions:

- Physically separates the atria from the ventricles

- Electrically inactive and blocks the direct spread of electrical impulses from the atria to the ventricles

- Provides support for the heart, providing a point of attachment for the valves leaflets and cardiac muscle

Coronary circulation

The heart, like other organs, receives its blood supply through arteries that branch from the aorta

Coronary circulation is part of the systemic circulatory system and supplies blood to and provides drainage from the tissues of the heart

Coronary arteries: arteries supplying the heart

- Aortic sinus is a dilation or out-pocketing of the ascending aorta; site where the left and right coronary arteriesCardiac veins: collect poorly oxygenated blood and empty into the coronary sinus, which returns blood to the right atrium

Coronary sinus: a collection of veins joined together to form a large vessel that collects blood from the myocardium of the heart and empties into the right atrium, returning the poorly oxygenated blood back to the right side of the heart

Systole: represents the time during which the left and right ventricles contract and eject blood into their respective artery

Diastole: represents the period of time when the ventricles are not contracting; relaxed

Myocardial blood flow is not steady; blood flow almost ceases while the heart is contracted (systole) and peaks while the heart is relaxed (diastole)

Coronary heart disease

Caused by atherosclerosis (a condition in which the arteries become hardened and narrowed because of an excessive accumulation of plaque in the vessel wall) of the coronary arteries supplying blood to the heart tissues

Atherosclerotic plaque: made of fat, cholesterol, calcium and other substances in the blood

When plaque builds up, the diameter of that artery is narrowed, providing resistance to blood flow, reducing flow through the arteries supplying the heart tissue

Angina: chest pain; when a plaque is present in a coronary artery, restricted blood flow to the heart muscle may result in discomfort or chest pain.

Myocardial infarction: heart attack; atherosclerotic plaques can grow so large that they completely block arterial blood flow, causing a heart attack; heart muscle dies due to loss of blood supply

Cardiac syncytium

Myocytes joined by intercalated discs which contain gap junctions and desmosomes

Mechanically, chemically, and electrically connect myocytes to one another

The entire heart tissue resembles a single, enormous muscle cell and the cardiac muscle is called a syncytium (a set of cells that act together)

Gap junctions allow excitation, or APs, to spread quickly from one myocyte

to another by cell-to-cell contactCardiac muscle cells are so tightly connected that when one of the myocytes

becomes excited, the AP spreads to all of them through gap junctionsCardiac muscle has 2 syncytia: the left and right atria act as one functional syncytia and the left and right ventricles also act as another functional syncytia

- This gives the heart an all or none property- either all of the myocytes respond and are excited or none of the myocytes respondThe heart contracts in series: 1st the left and right atria contract together and then the left and right ventricles contract together

Action potentials lead to contraction of heart muscle cells and ejection of blood

Autorhythmicity (automaticity) → the heart contracts or beats rhythmically as a result of action potentials that it generates itself

- Action potentials in the heart are generated without nervous or hormonal stimulation

- The rhythmicity of the heart is myogenic (muscular) in origin2 types of specialized cardiac muscle cells or myocytes

1. Contractile cells:

- Perform the mechanical work of pumping or contracting to propel blood forward; generate pressure to move blood

- ~ 99 % of myocytes are contractile cells

- Do not normally initiate their own APs, but contract when stimulated by an action potential passed to them through gap junctions from an adjacent contractile cell that has been stimulated by an AP or an adjacent conducting cell.

2. Conducting cells:

- Autorhythmic cells which initiate and conduct APs which are responsible for contraction of the contractile cells

- Myocytes (muscle cells) which initiate and conduct APs without nervous or hormonal stimuli

- Have very few myofibrils (protein filaments needed for contraction) and do not contribute to the heart’s contraction and the movement of blood.

- ~ 1 % of myocytes are conducting cells

- Part of the conducting system of the heart. Are in electrical contact with each other and the cardiac contractile cells through the gap junctions

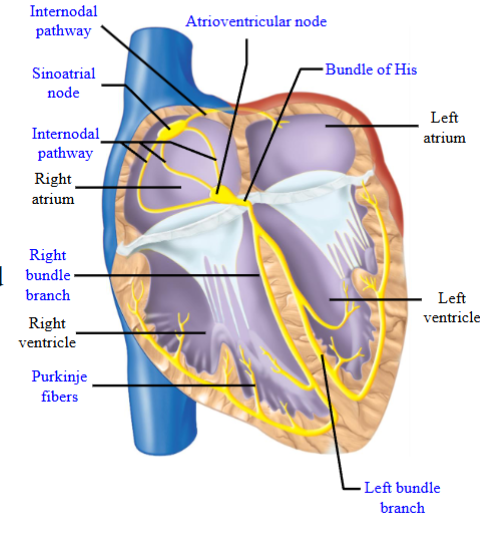

Components of heart’s conducting system

The spread of APs through the myocardium leads to the contraction of the heart muscle cells

The heart contracts in series: first both atria depolarize and contract as a unit before both ventricles depolarize and contract as a unit

The conducting myocytes are found in: sinoatrial node (SAN), internodal

pathways, atrioventricular node (AVN), the bundle of His (AV bundle), the left

and right bundle branches, Purkinje fibers

- SAN located in the wall of the right atrium; AVN located at the base of the right

atrium; internodal pathways extend from the SAN to the AVN and also cross the

interatrial septum to the left atrium; bundle of His passes through the cardiac

skeleton; left and right bundle branches travel along the interventricular

septum; left and right bundle branches make contact with Purkinje fibers, which

extend into the myocardium of the ventriclesCardiac skeleton: Non-conducting or it will not allow APs to travel across it

- Physically separates the atria from the ventricles: The only electrical connection between the atria and ventricles in a normal heart is the AVN and the Bundle of His

Sinoatrial (SA) and Atrioventricular (AV) nodes

All the cells in the conducting system are capable of initiating action potentials

The rate at which each region action potentials differs

Conducting myocytes in the SAN generate APs at the fastest rate; 60 to 100 APs/min

This stimulus is then passed on to the other regions of the conducting system through gap junctions, generating APs in these other regions before they have time to initiate their own APs

SAN generates action potentials that drive the rest the conducting system.

- Cardiac pacemaker: initiates action potentials that set the heart rateSAN generates action potentials → internodal pathways → contractile cells of both the left and the right atria → left and right atria contract at same time → stimulus is also passed by the internodal pathways to AVN → the wave of depolarization must pass through the AVN and the Bundle of His to excite the ventricles due to presence of cardiac skeleton

Stimulus passes to the AVN through the internodal pathways from the SAN

AV nodal delay: the propagation of action potentials through the AVN is relatively slow; takes ~ 100 ms for the stimulus to pass through the AVN to the Bundle of His

This delay ensures that the atria depolarize and contract before the ventricles depolarize and contract

The ventricular myocardium must be relaxed to fill with blood from the atria. Ensures ventricles are relaxed and have time to fill with blood before they contract

Sequence of excitation

AVN and Bundle of His are the only electrical connection between the atria and

ventricles in a normal heartLeft and right bundle branches travel along intraventricular septum and make contact with Purkinje fibers

Purkinje fibers:

- Large number, diffuse distribution (ie. all over the ventricles), fast conduction velocity

- Stimulus depolarized left and right ventricular myocytes and causes contractio nearly simultaneously due to Purkinje fibersWolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome: There is an extra connection in the heart called an accessory pathway

- An accessory pathway is an abnormal piece of muscle that connects directly between the atria and the ventricles

- Allows electrical signals to bypass the AVN and move from the atria to the ventricles faster than usual

- Electrical impulses may also be transmitted abnormally from the ventricles back to the atria

- Disrupts the coordinated movement of electrical signals through the heart, leading to an abnormally fast heartbeat, called tachycardia, and other arrhythmias

Two types of AP in heart

Fast and slow action potentials

Fast: found in contractile myocytes in the atrial myocardium, ventricular

myocardium, bundle of His, Bundle branches (left and right) and Purkinje fibersSlow: found in conducting myocytes in the sinoatrial node and atrioventricular node

The terms fast and slow describe how quickly the membrane potential changes during the depolarization phase of the action potential

Fast action potential:

- Rapid rate of depolarization in which the membrane potential rises very quickly from the threshold potential to the new transiently positive potentialSlow action potential:

- Slower rate of depolarization, in which the membrane potential takes

more time to reach the new potentialWhy do action potentials have different rates of depolarization? Depends on the

ions and ion channels involved in the depolarization phasePhases of the cardiac action potential are associated with changes in permeability of the cell membrane mainly to Na+, K+, Ca2+ ions. Opening and closing of ion channels alters permeability

- [K+]IN > [K+]OUT

- [Ca2+]OUT > [Ca2+]IN

- [Na+]OUT > [Na+]IN

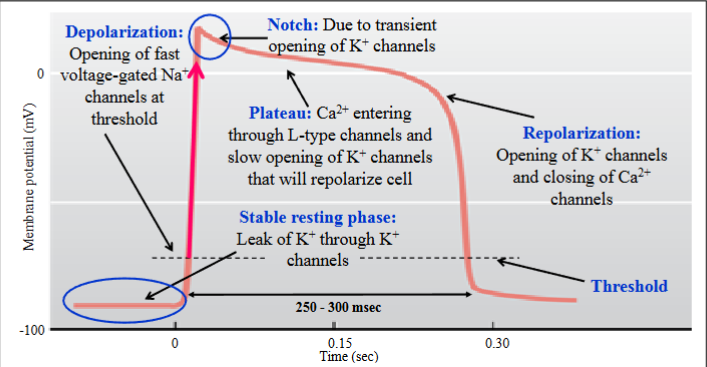

![<ul><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>Fast and slow action potentials</span></span></p></li><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>Fast: found in contractile myocytes in the atrial myocardium, ventricular</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>myocardium, bundle of His, Bundle branches (left and right) and Purkinje fibers</span></span></p></li><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>Slow: found in conducting myocytes in the sinoatrial node and atrioventricular node</span></span></p></li><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>The terms fast and slow describe how quickly the membrane potential changes during the depolarization phase of the action potential</span></span></p></li><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>Fast action potential:</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>- Rapid rate of depolarization in which the membrane potential rises very quickly from the threshold potential to the new transiently positive potential</span></span></p></li><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>Slow action potential:</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>- Slower rate of depolarization, in which the membrane potential takes</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>more time to reach the new potential</span></span></p></li><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>Why do action potentials have different rates of depolarization? Depends on the</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>ions and ion channels involved in the depolarization phase</span></span></p></li><li><p><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>Phases of the cardiac action potential are associated with changes in permeability of the cell membrane mainly to Na+, K+, Ca2+ ions. Opening and closing of ion channels alters permeability</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>- [K+]IN > [K+]OUT</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>- [Ca2+]OUT > [Ca2+]IN</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span>- [Na+]OUT > [Na+]IN</span></span><span style="color: rgb(0, 0, 0);"><br></span></p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/ee1ab146-0af7-44ec-80e8-46f299650484.png)

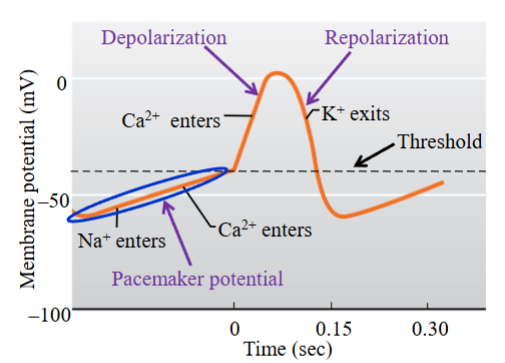

SA node action potential

Phases of the slow action potential: pacemaker potential, depolarization and repolarization

SAN cells:

- Pacemaker potential → it is not a steady or true resting potential but a slow

depolarization to threshold; gradual depolarization of the membrane potential

to threshold

- When threshold is reached, the depolarization phase of the action potential occursPacemaker potential allows the SAN cells (muscle cells) to generate regular spontaneous APs without any external influence from nerves or hormones

Stages of slow action potential and ion channels involved:

1. Pacemaker potential → 3 ionic conductances involved: 1) progressive reduction in K+ permeability (K+ channels that opened during the repolarization phase of the previous action potential gradually close due to the return of the membrane to negative potential), 2) F-type channels (depolarizing Na+ current; Na+ moves into cell), 3) T-type channels (Ca2+ channel; T= transient; opens only transiently (briefly), contributes an inward Ca2+ current, provides a final depolarization to bring the membrane to threshold)

2. Depolarizing phase → L-type channels (Ca2+ channel; L= long-lasting; channels open more slowly and remain open for a prolonged or long period)

3. The Ca2+ currents depolarize the membrane more slowly than voltage- gated Na+ channels so the rising phase of the AP occurs much more slowly than if Na+ was responsible for the rising phase; APs are therefore called ‘slow’ (remember voltage-gated Na+ channels are responsible for the depolarization phase of the nerve/muscle action potential)

4. The long opening of the L-type channels prolongs the nodal action potential- it is approximately 150 ms in duration (nerve/muscle action potentials ~ 2 ms)

5. Repolarization phase → opening of voltage-gated K+ channels; K+ leaves the cellSAN cells undergo repeated cycles of drifting pacemaker potential and firing of the AP, allowing these cells to generate action potentials in the absence of any

hormonal or nervous stimuliAVN → ‘slow type action potential’; slow pacemaker potential than SAN pacemaker potential

- As the SAN pacemaker potential reaches threshold first, it will pass its stimulus

to other cells in the heart, driving the heart rate at a rate of 60-100 beats/minute

- If SAN becomes damaged, the AVN may generate APs to drive the ventricles, but at a lower rate of ~ 40 - 60 beats/minute

Venticular muscle cell AP

K+ conductances involved in the resting phase, the notch and the repolarization phase have varying properties and involve different subsets of K+ channels; simply know that various K+ channels are involved

Duration of the action potential is ~ 250 to 300 ms, due to the long plateau phase

This affects the duration of the refractory period

This fast-type action potential is also found in the atrial contractile cells (atrial myocardium)

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

A recording of the electrical activity of the heart

A measure of the currents generated in the extracellular fluid by the changes occurring simultaneously in many cardiac cells

Can be measured by an array of 12 lead electrodes placed on the body surface.

Electrical activity can be seen from different angles

The electrical signal becomes weaker as it travels through the body tissues to the surface of the skin

Voltage changes in the heart’s ventricular muscle are ~100 millivolts in magnitude, but only 1 millivolt at the surface of the skin

Used to diagnose problems with the heart’s conducting system

ECG allows different angles for viewing heart’s electrical activity

- An established electrode pattern results in specific tracing pattern

- Look for differences in the established tracing patter if there are electrical problems in the heart

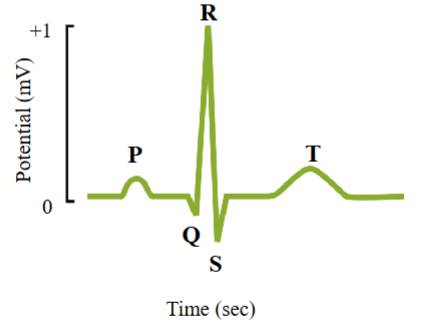

ECG recording

ECG represents changes occurring simultaneously in many cardiac cells, not recording changes from individual cardiac cells.

P wave:

- First wave on ECG

- Represents depolarization of the atria

- Upward deflection in the trace

- Approximately 25 ms after the P-wave, the atria will contractQRS complex:

- Wave consisting of 3 peaks, labelled Q, R and S

- Represents depolarization of the ventricles

- When the ventricles are depolarizing, the atria repolarizeAtrial repolarization is too small an electrical event to be recorded at the surface of the skin

T wave:

- Upward deflection

- Represents repolarization of the ventriclesCG → shows a 1 millivolt difference in the membrane potential recorded. Action potential → shows changes of approximately 110 millivolt

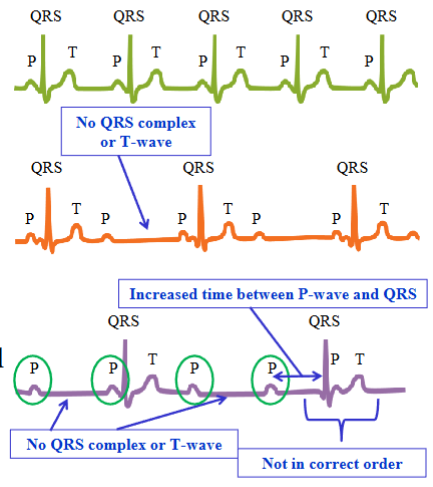

Change in ECG based on heart

Many myocardial defects alter normal action potential propagation, and as a result the shapes and timing of the waves on the ECG vary

AV node block: a type of heart block in which conduction between the atria and ventricles is impaired; partial or complete interruption of the impulse from the atria to the ventriclesPartial AV node block: the damaged AV node permits only

Partial AV node block: the damaged AV node permits only every other atrial impulse to be transmitted to the ventricles; every second P-wave is not followed by a QRS complex or a T-wave

Complete AV node block: electrical depolarizations of the atria are not transmitted to the ventricles; no synchrony between atrial and ventricular electrical activities

Any component of the heart’s conduction system is capable of initiating action

potentials to drive the heartDifferent regions generate action potentials at different rates

- SAN generates action potentials at fastest rate; in a normal healthy heart, the SAN generates APs which drive the rest of the hearts conducting system; heart’s pacemaker

Cardiac myocytes

Cardiac myocyte: muscle cell of the heart

Intercalated disk: where the membranes of two adjacent myocytes are extensively intertwined; both desmosomes and gap junctions

Sarcolemma: plasma or cell membrane of a cardiac

Sarcoplasmic reticulum: a special type of smooth endoplasmic reticulum which stores and pumps Ca2+

- Ca2+ is important for excitation-contraction couplingCardiac myocytes contain myofibrils

- Myofibrils are made up of sarcomeresSarcomeres → contractile unit of muscle; contain the protein filaments actin (thin filament) and myosin (thick filament)

- Orderly arrangement of actin and myosin in the myofibrils gives cardiac muscle its striated or striped appearanceT-tubules → invaginations of the sarcolemma; surround myofibrils; transmit

action potentials propagating along the surface membrane to the interior of the

muscle fiber; lie in close proximity to the sarcoplasmic reticulum and contain many L-type Ca2+ channels

Excitation-contraction coupling (ECC)

Excitation-contraction coupling: the process by which the arrival of an AP at the cell membrane leads to contraction of the muscle cell

Steps involved in ECC:

- Ca2+ levels control contraction of the cardiac muscle. Ca2+ is normally found in low concentrations in the cytoplasm of the cell, and high concentrations in the extracellular fluid1. During the plateau phase of the AP, extracellular Ca2+ enter the cytoplasm of the cardiac muscle cell through the L-type Ca2+ channels. This Ca2+ is not sufficient to cause contraction of the myocytes

2. Ca2+ that enters through the L-type calcium channels binds to ryanodine

receptors on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)

3. Ryanodine receptors bind Ca2+ and have an intrinsic Ca2+ channel; when Ca2+ binds to the ryanodine receptor, the channel in the ryanodine receptor opens, allowing the release of Ca2+ from the SR into the cytoplasm. SR has a high concentration of Ca2+ (source of ~ 95% of the Ca2+ in the cytoplasm)

4. Ca2+ causes its own release from the SR following binding to the ryanodine receptor = calcium-dependent calcium release or calcium-induced calcium releaseCa2+ is important for contraction of the cardiac muscle cells

Steps involved in contraction:

1. Excitation spreads along the sarcolemma, or plasma membrane, from ventricular myocyte to ventricular myocyte by gap junctions

2. Excitation spreads down to the interior of the myocyte by T-tubules, which also contain many L-type calcium channels

3. During the plateau phase of the fast AP, the permeability of the myocyte to Ca2+ increases as L-type Ca2+ channels in the sarcolemma and T-tubules open following a change in membrane potential

4. This Ca2+ entering the myocyte binds to ryanodine receptors on the SR

5. Following binding of Ca2+, the ryanodine receptors contain an intrinsic channel that opens to allow Ca2+ to exit the SR into the cytoplasm of the cell (calcium-induced calcium release)

6. Cytosolic Ca2+ binds to troponin, inducing a conformational change in the regulatory complex; binding sites on actin are now able to bind to the energized cross-bridge on the myosin head

7. Cross-bridge cycling and shortening of the sarcomere and contraction of the muscle

EEC relaxation

Relaxation of the ventricular myocardium is important as the ventricles only fill with blood when they are relaxed (diastole)

The interaction of myosin with actin causes cross-bridge cycling and muscle contraction; Ca2+ plays a role in cross bridge cycling by binding to troponin, allowing interaction between actin and myosin

To end a contraction Ca2+ must be removed from troponin. Ca2+ levels in the cytoplasm must be reduced to pre-release levels.

How:

- L-type Ca2+ channels close to reduce influx of Ca2+ into the cell

- SR will no longer be stimulated to release Ca2+ into the cytoplasm as Ca2+ is no longer entering the cell and binding to ryanodine receptors on the SR

- SR contains Ca2+-ATPases to pump Ca2+ in the cytosol back into the SR

- Ca2+ is also removed from the myocyte by a Na+/Ca2+ exchanger found in the sarcolemma

- The reduced binding of Ca2+ to troponin will block the sites of interaction between myosin and actin, allowing for relaxation of the myofibrilsRemoval of Ca2+ from the cytosol:

- Ca2+-ATPase on the SR → removes the majority of Ca from2+ the cytosol

- Na+/Ca2+ exchanger found in the sarcolemma (also closing of L-type Ca2+ channels)Refractory period: a period of time during and after an action potential in which an excitable membrane cannot be re-excited

- Due to the long plateau phase of the ventricular action potential, the refractory period lasts almost as long as the contraction

- Absolute refractory period ~ 250 ms. The membrane will not respond to another stimulus, regardless of how strong it is

- Membrane of the muscle cell is refractory due to the inactivation of the

fast voltage-gated sodium channels that open during the depolarization phase of the action potential

- After the voltage-dependent Na+ channels close, they enter a state of

inactivation and cannot be opened again until the membrane of the muscle cell has returned back to negative potentials, where the channels will begin to recover and are ready to be opened againThe long refractory period prevents tetanus

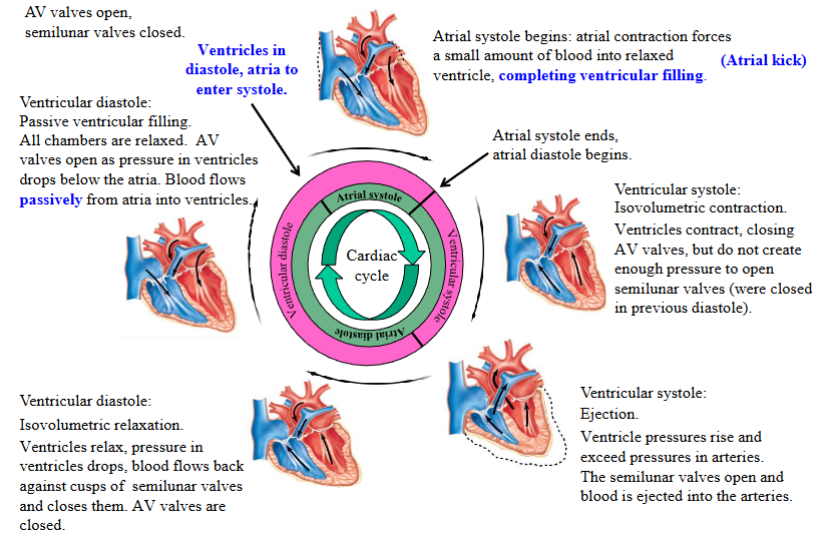

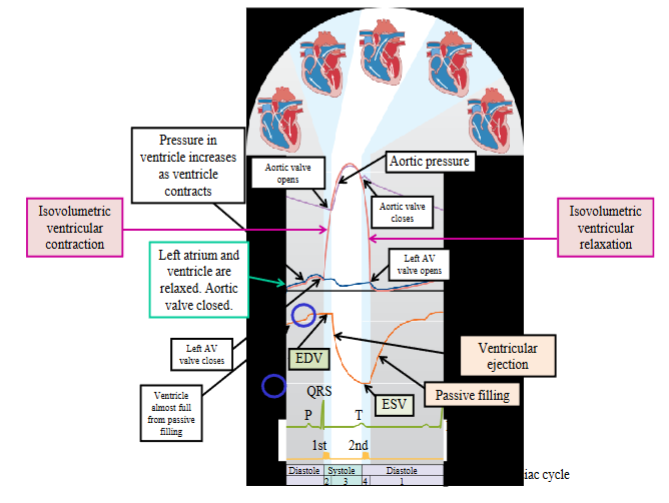

Systole

Ventricular systole can be divided into two phases: isovolumetric ventricular contraction and ventricular ejection

When the ventricles contract, they squeeze the volume of blood in their chambers, generating pressure; pressure creates blood flow

Isovolumetric = ‘iso’ + ‘volumetric’; same volume (constant/unchanging volume)

Isovolumetric ventricular contraction: ventricles contract, all heart

valves closed (AV and semilunar valves), blood volume in ventricles

remains constant, pressures rise; muscle develops tension but cannot shorten

- Blood cannot enter or exit the ventricles because the valves are closed

- During isovolumetric ventricular contraction, the ventricular walls do develop tension as they contract and squeeze the blood in the chamber, raising the ventricular blood pressure. The blood is incompressible and cannot flow anywhere as the valves are closed

- Ventricular myocardium is squeezing against the incompressible blood and the volume is not changing; the ventricular muscle fibers cannot shortenVentricular ejection phase: pressure generated by the ventricles

during contraction now exceeds the pressure in the artery into which

the ventricle ejects its blood

- This forward pressure gradient opens the semilunar valves, allowing the ventricular muscle fibers to shorten as the ventricles continue contracting and eject their volume of blood into the arteries

- AV valve is closed during ventricular ejection, being held in the closed position by the chordae tendineae and the papillary muscles

- Ventricular muscle fibers are shorten as the blood is ejected from the ventriclesStroke volume: the volume of blood ejected from each ventricle during systole, or during contraction

- The left and right ventricles eject the same volume of blood when they contract, but the left ventricle does this with more pressure than the right ventricle

- When contracting, the ventricles do not eject their entire volume of blood

Diastole

Ventricular diastole can be divided into two phases: isovolumetric ventricular relaxation and ventricular filling

The ventricles can only fill with blood while the ventricular myocardium, or the muscle layer of the ventricles, is relaxed

Isovolumetric ventricular relaxation: all heart valves closed, blood volume remains constant, pressures drop

- AV valve and semilunar valve are closed

- Ventricular volume is not changing and the pressure inside the ventricles is dropping as the myocardium is relaxingVentricular filling: AV valves open, blood flows into ventricles from atria; ventricles receive blood passively (atria are relaxed)

- When the atria are in diastole they receive blood returning back to the heart in the veins; once that the atria are full of blood (and the ventricles are relaxed), pressure in the atria rises above the pressure in the ventricles (the pressure in the atria is simply due to the volume of blood in the atria); this is a forward pressure gradient

- The forward pressure gradient will open the AV valves, allowing blood to flow from the relaxed atria to the relaxed ventricles2 phases of ventricular filling: passive ventricular filling and atrial contraction

- Passive ventricular filling → the ventricles receive approximately 70 per cent of their blood volume. Both the atria and the ventricles are relaxed; atria have a greater pressure than the ventricles because they are full of blood

- Atrial contraction or atrial kick → completes ventricular filling; remember ventricles are still relaxed

Phases of cardiac cycle

Pressure-volume curve

Also called Wiggers diagram

Pressure is the key to understanding blood flow patterns and the opening and closing of valves:

- Pressure is generated when the muscles of the heart chamber contract as well as when a chamber fills with blood

- Blood always flows from a region of higher pressure to a region of lower pressure

- Valves open and close in response to a pressure gradient; a forward pressure gradient opens a one-way valve while a backward pressure gradient shuts a

one-way valveEnd-diastolic volume (EDV): the amount or volume of blood in each ventricle at the end of ventricular diastole; measured in millilitres (mL)

End-systolic volume (ESV): the amount or volume of blood in each ventricle at the end of ventricular systole, or at the end of ventricular contraction and ejection; in mL

- When the ventricles contract they do not eject their entire volume of bloodStroke volume (SV) → the volume of blood pumped out of each ventricle during

systole

- Calculated as: SV = EDV - ESV

- Typical SV values for an adult at rest are ~ 70 - 75 mLThe right ventricle develops lower pressures than the left ventricle during systole (still undergoes the same series of events)

Heart sounds & murmurs

First heart sound → lub; caused by closure of the AV valves at the beginning of

isovolumetric ventricular contraction and signifies the onset of ventricular systoleSecond heart sound → dub; caused by closure of the semilunar valves and signifies the onset of ventricular diastole

The heart sounds reflect turbulence when the valves passively snap shut as the

pressures across the valves changeLub and dub signify closing of the valves on both sides of the heart; both the left and right AV valves close together and make the sound lub and both semilunar

valves close together and make the sound dubNormally blood flow through valves and vessels is laminar flow and makes no sound

Laminar flow is characterized by smooth concentric layers of blood moving in

parallel down the length of a blood vessel

- The highest velocity (Vmax) is found at the central axis, or the center, of the vessel and the lowest velocity (V=0) is found along the vessel wall- The flow profile is parabolic once laminar flow is fully developed

- This occurs in long, straight blood vessels, under steady flow conditions

- Under conditions of high flow, particularly in the ascending aorta, laminar flow can be disrupted and become turbulentTurbulent flow makes a sound and is called a murmur

- Stenotic valve: a valve in which the leaflets do not open completely; this can

occur when the valve leaflets become stiffer due to calcium deposits or scaring

of the valve; when blood flows through a stenotic valve, it becomes turbulent

and this is heard as a murmur

- Insufficient valve: does not close completely due to widening of the aorta or scaring of the valve; blood flows backwards through the leaky valve and produces turbulence which is heard as a murmur

Effect of ANS on heart

The heart is innervated by sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers

Sympathetic innervation through the thoracic spinal nerves

- Sympathetic postganglionic fibers innervate the entire heart, including the atria, ventricles, SA node and AV node

- Neurotransmitter released: norepinephrineParasympathetic innervation through the vagus nerve

- Parasympathetic postganglionic fibers innervate the atria, SA node and AV node

- Neurotransmitter released: acetylcholine

- Important: ventricles do not receive significant parasympathetic innervation and the ventricular myocardium is not affected by parasympathetic activityParasympathetic stimulation:

- Decrease heart rate by decreasing the rate of depolarization, or the rate of rise

to threshold, of the pacemaker potential;

- Decrease the conduction of the electrical impulses through the AVN, increasing

AV nodal delay; this means that it will take longer for the stimulus to pass through the AVN into the ventricles

- Decrease contractility of the atrial myocardium, decreasing the force of

contraction; remember the ventricular myocardium receives little or no

parasympathetic innervation, and as a result parasympathetic stimulation has

no effect on contractility of the ventricleSympathetic stimulation:

- Increase heart rate by increasing the rate of depolarization, or the rate of rise

of the pacemaker potential to threshold

- Increase conduction of the electrical impulses through the AVN, decreasing AV

nodal delay; this means it takes less time for the stimulus to pass through the

AVN to the ventricle

o Increase the contractility of the atrial and ventricular myocardium, increasing

the force of contraction

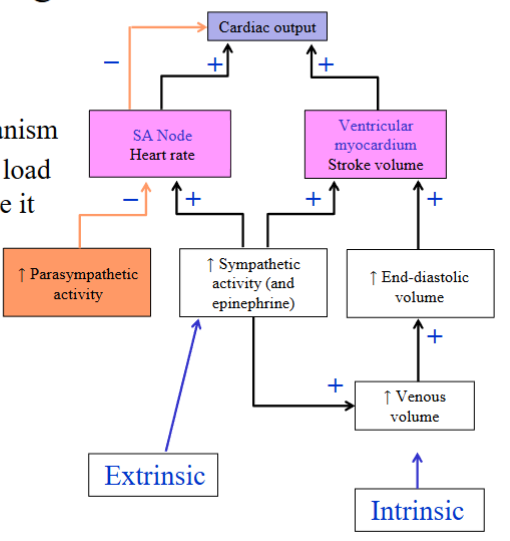

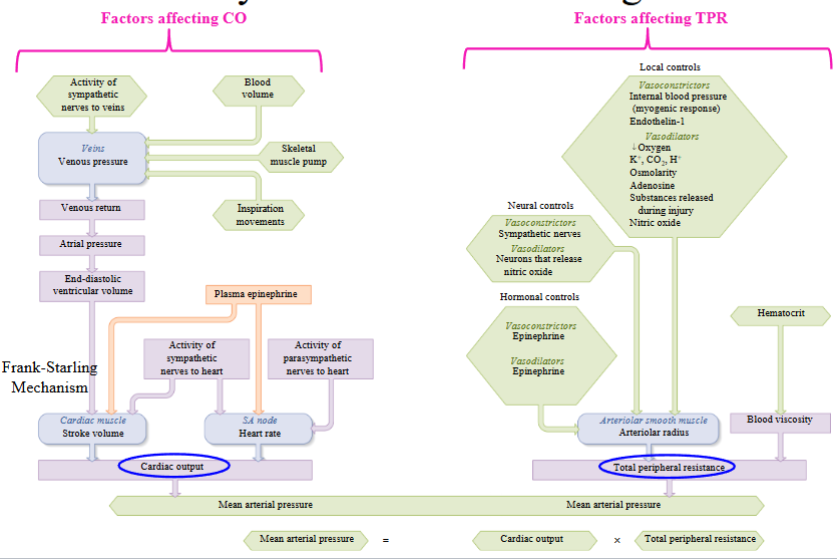

Cardiac output

Cardiac output (CO): the amount of blood pumped by each ventricle in one minute; CO = HR x SV. Differs from stroke volume in that it is measured per unit time

Stroke volume (SV) : the amount of blood pumped out of each ventricle during systole; typical stroke volumes are 70 - 75 mL

As CO = HR x SV by altering the either the heart rate (HR) or the stroke volume (SV), we can alter cardiac output (CO)

How do we alter heart rate (HR)?

- Heart rate may be altered by modifying the activity of the SAN (heart’s pacemaker)How do we alter stroke volume (SV)?

- Stroke volume can be altered by varying the strength of the contraction of the

ventricular myocardium

- When the ventricles contract, they do not empty their entire volume of blood; altering the strength of contraction of the ventricular myocardium will alter the SV, or the volume of blood pumped out

- An increased strength of contraction will increase SV; a decreased strength of contraction will decrease SV

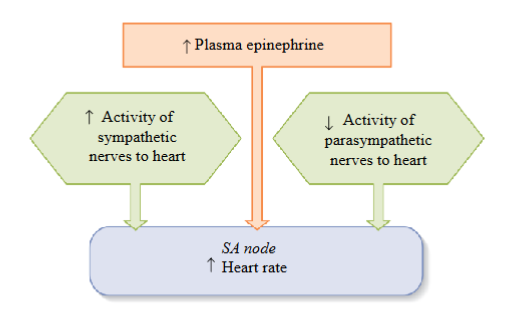

Factors affecting heart rate

The heart has resting autonomic tone; both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are active at a steady background level (called tone)

One division of the ANS will dominate when its rate of firing raises above a tonic level while the other’s falls below

Parasympathetic and sympathetic effects are antagonistic for heart rate

- To increase HR, sympathetic stimulation will increase while parasympathetic

stimulation will decrease; to decrease HR, the parasympathetic stimulation will

increase while sympathetic stimulation will decreaseUnder resting conditions, parasympathetic effects dominate for heart rate

To increase HR: must increase the activity of the sympathetic division

- Increased sympathetic activity and increased release of epinephrine from the

adrenal medulla will stimulate/increase the activity of the SAN, increasing HR and CO

- As the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are antagonistic, activity in

the parasympathetic system must be decreased when sympathetic activity is increasedTo decrease HR: must increase the activity of the parasympathetic division

- Increased parasympathetic activity will inhibit or decrease the activity of the

SAN, thereby decreasing HR and CO

- As the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are antagonistic, activity in

the sympathetic system must be decreasedSympathetic and parasympathetic effects on the heart are extrinsic factors or theyn originate outside the heart

Important: the conducting myocytes in the heart are responsible for initiating the heart rate; cells of the SA node are the heart’s pacemaker generating the APs that are responsible for the HR

Sympathetic stimulation of the SAN → increases the slope of the pacemaker potential causing a faster depolarization to threshold; faster rise to threshold increases heart rate

Sympathetic stimulation increases the slope of the pacemaker potential by

increasing the permeability of the F-type and T-type channels

- F-type channels allow Na+ to enter the cell, T-type channels allow Ca2+ to enter the cell. More positive charge enter into the cell, bringing them to threshold more rapidlyParasympathetic stimulation of the SAN → decreases the slope of the pacemaker potential causing a slower depolarization to threshold or takes more time; decreases heart rate

Parasympathetic stimulation decreases the slope of the pacemaker potential by:

- Decreasing F-type channel permeability, reducing the movement of Na+ into the cells

- Increasing K+ channel permeability, causing more K+ to leave the cell, making the cell more negative inside

- The pacemaker potential starts from a more negative value, closer to the equilibrium potential for K+, taking more time to reach threshold

Factor one affecting stroke volume (EDV)

EDV: the volume of blood in the ventricles at the end of ventricular diastole, or the volume of blood in the ventricles after the ventricles have completed filling

The heart has an intrinsic mechanism to alter stroke volume

- This intrinsic mechanism because the ventricles will contract more forcefully when they have been stretched prior to contractionHow are the ventricles stretched? Increased stretch is accomplished by filling the ventricles more fully with blood

- The relationship between the end-diastolic volume and stroke volume is defined by the Frank-Starling mechanismHow do we fill the ventricles more fully with blood? Increase the venous

return, or the amount of blood returning to the heart through the veins;

this will more fully fill the ventricles with blood, increasing the EDV,

increasing SV, which ultimately increases COPreload → the tension or load on the ventricular myocardium before it begins to

contract, or the amount of filling of the ventricles at the end of diastole, which is the EDVSympathetic stimulation of venous smooth muscle will act to increase the return of blood to the heart through venoconstriction, increasing filling of the ventricles

Sympathetic effect on venous smooth muscle is an extrinsic mechanism, which originates outside the heart.

Why does the parasympathetic system in the diagram not affect the venous

volume? Most of the blood vessels in our body receive only sympathetic

innervation to their smooth muscleFrank-Starling mechanism: Intrinsic mechanism. Occurs independent of neural or hormonal stimulation. The relationship between EDV and SV is defined by the Frank-Starling mechanism. As you increase EDV, you increase SV

Why does an increased EDV lead to an increased SV?

- The main determinant for sarcomere length is the degree or amount of

diastolic filling

- The initial length of the sarcomere will affect the tension generated during

contraction

- As the ventricles become more filled with blood, the cardiac fibers or the sarcomeres stretch out, putting more load on the sarcomeres; the ventricles will

contract more forcefully when they have been stretched, and SV will increase

- The Frank-Starling mechanism is a length-tension curveThe Frank-Starling mechanism matches the outputs of the two ventricles

- Ensures the two ventricles pump the same amount/volume of blood and blood

does not accumulate in one circuit compared to the othe

Factor two & three affecting stroke volume (contractility & afterload)

Remember: the ventricles do not completely empty when they contract

A change in the contractility of the ventricles (contractility = the strength of

contraction at any given EDV) will alter the volume of blood pumped by the

ventricles during systole, or the SV

- Increased sympathetic stimulation will increase the strength of contraction of

the ventricular myocardium, increasing SV and CO

- Altering parasympathetic activity will not affect contractility of the ventricles

and SV, as the ventricular myocardium receives little or no parasympathetic

innervationThe Frank-Starling mechanism still applies under sympathetic stimulation, but during sympathetic stimulation, the stroke volume is greater at any given EDV

- At the same EDV, there is an increase in SV under sympathetic stimulationUnder sympathetic stimulation, increased contractility will lead to a more complete ejection of the end-diastolic ventricular blood volume, increasing the ejection fraction (= SV/EDV).

Increased sympathetic activity also acts to increase the rate of contraction and relaxation

- Under sympathetic stimulation, the heart contracts and relaxes faster, giving

more time for the ventricles to fill, despite the increase in heart rateSympathetic regulation of myocardial contractility acts through a G protein coupled mechanism:

- A number of proteins involved in the excitation-contraction coupling process are phosphorylated by intracellular kinases, which enhances contractility

- These proteins include: L-type Ca2+ channels in the sarcolemma, the ryanodine receptor in the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane, thin filament proteins (troponin), thick filament proteins associated with the cross-bridges,

and proteins involved in pumping Ca2+ back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum

When the ventricles contract they must generate sufficient pressure to exceed the pressure in the arteries and open the semilunar valves to eject their blood into the arteries

Afterload: the tension against which the ventricle must eject its blood; it is closely related to the arterial pressure; often called the ‘load’

The greater the afterload, the longer the period of isovolumetric contraction during which time the heart generates sufficient pressure to open the valves and eject blood, and a smaller stroke volume

As afterload increases, SV decreases. Afterload is increased by any factor that restricts blood flow through the arterial system

Arteries

Walls of arteries contain: smooth muscle, elastic fibers and connective tissue

Muscular walls allow arteries to contract and change diameter

Elasticity permits passive changes in vessel diameter in response to changes in blood pressure

Vasoconstriction: contraction of arterial smooth muscle decreases the diameter of the artery

Vasodilation: relaxation of arterial smooth muscle increases the diameter of the artery

Elastic arteries: contain many elastic fibers and few smooth muscle cells; pulmonary trunk and aorta; can tolerate pressure changes during the cardiac cycle

Muscular arteries: contain many smooth muscle cells and few elastic fibers (most of the vessels in the arterial system); function to distribute blood throughout the body

Arterioles: smallest of the arteries; composed of 1 to 2 layers of smooth muscle cells; resistance vessels in the body; play a very important role in determining our mean arterial pressure, or our blood pressure

Arterioles

Small diameter vessels and their small diameter offers significant resistance to

flow, which is why there is a large decrease in mean arterial pressure as the blood flows through arteriolesThe pattern of blood-flow distribution depends upon the degree of arteriolar

smooth muscle contraction within each organ and tissueArterioles play an important role in determining our MAP, or our blood pressure, and by altering their diameter, the arterioles can alter blood flow to different organs and tissues

Arteriolar smooth muscle has intrinsic or basal tone:

- Tone; partial contraction in the absence of external factors such as neural or hormonal stimuli

- Other factors can then increase or decrease the intrinsic/basal tone

- These factors may be extrinsic or intrinsicExtrinsic factors: external to the organ or tissue and alter whole body needs, such as MAP, and include nerves and hormones

Intrinsic factors: local controls which include mechanisms independent of nerves or hormones by which organs and tissues alter their own arteriolar

resistances, thereby self-regulating their blood flow

Extrinsic controls; nerves and hormones

Extrinsic factors: are external to the organ or tissue and include nerves or

hormones to exert their effects on arteriolar smooth muscleSympathetic innervation to arteriolar smooth muscle but little, or no parasympathetic innervation

The sympathetic nerve fibers release norepinephrine to cause vasoconstriction

The sympathetic neurons are seldom completely inactive, but discharge at some basal level called sympathetic tone (Sympathetic neurons cause some degree of tonic constriction in addition to the vessels' intrinsic tone)

Sympathetic tone can be increased, causing further vasoconstriction, or decreased, causing vasodilation

Sympathetic innervation to the arteriolar smooth muscle is important for regulating MAP. Regulates MAP by influencing arteriolar resistance throughout the body

Noncholinergic, nonadrenergic neurons affect arteriolar smooth muscle. Release nitric oxide, a vasodilator

Hormone: epinephrine. Released from the adrenal medulla into the blood

- Acts on arteriolar smooth muscle to cause vasoconstriction or vasodilation, depending on receptor to which it binds

Local control; Hyperemia & flow autoregulation

Local controls: mechanisms independent of nerves or hormones; mechanisms by which the organ or tissue alters its own arteriolar resistance, thereby regulating its own blood flow

Active hyperemia: local control which acts to increase blood flow when the

metabolic activity of an organ or tissue increasesHyperemia: an excess of blood in the vessels supplying an organ or

tissueArteriolar smooth muscle is sensitive to local chemical changes in the

extracellular fluid surrounding the arterioles, such as oxygen or carbon

dioxide levels or pHLocal chemical changes are the result of changes in metabolic activity

These altered chemical changes act on smooth muscle in the arterioles

to cause vasodilation and increase blood flow. Does not involve any nerves or hormones.

Locally mediated changes in arteriolar resistance also occur when a

tissue or organ experiences a change in its blood supply resulting from a

change in blood pressureAn increase in arteriolar pressure will increase blood flow to an organ; and vice versa

Altered blood flow will change the concentration of local chemicals (oxygen, carbon dioxide and hydrogen ions)

The change in the level of local chemicals will alter the state of constriction of the arteriolar smooth muscle, altering blood flow to bring the concentration of local chemical substances back to normal

Occurs at a constant metabolic activity and is the result of a change in pressure in an organ and, as a result, blood flow

Can occur when the blood pressure to an organ increases or decreases

Flow autoregulation is not only mediated by changes in local chemical factors, but also by the myogenic response

Myogenic response: the direct response of arteriolar smooth muscle to stretch

- An increase in arterial pressure and blood flow causes arterial walls to stretch, in addition to changing levels of local chemical factors. Arteriolar smooth muscle responds to this stretch by contracting. This will reduce blood flow to the organ toward normal levels.

- At the same time there is an increased stretch in the arteriolar walls due to the increased blood flow, there is an increase in oxygen levels and a decrease in metabolites. These changes in these local chemicals will also act to constrict the arteriolar smooth muscle, to bring levels back to normal.Reactive Hyperemia: Form of flow autoregulation

- Occurs at constant metabolic rate due to changes in the concentrations of local chemicals

- Occlusion of blood flow → greatly decreases oxygen levels and increases

metabolites → arterioles dilate → blood flow greatly increases once occlusion

removed

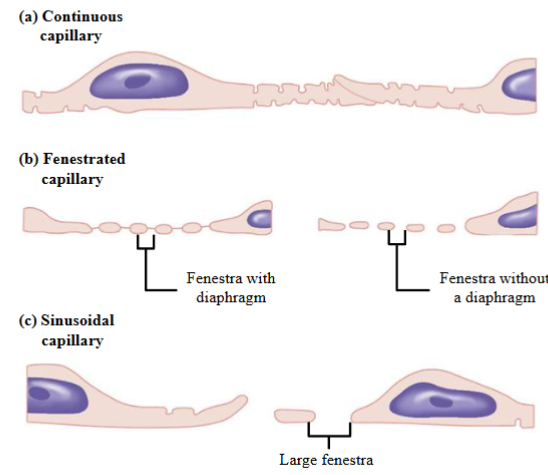

Capillaries

Thin walled vessels one endothelial cell thick. Supported by a basement membrane. Contain no smooth muscle or elastic fibers

Function in the rapid exchange of material between the blood and the interstitial fluid

Adjacent endothelial cells are joined laterally by tight junctions but leave gaps of

unjoined membrane called intercellular clefts (act as channels or water-filled spaces between endothelial cells through which small water-soluble substances can pass)May have fused-vesicle channels; Endothelial cells contain large numbers of endocytic and exocytic vesicles which fuse together to form continuous vesicular channels across the cell

3 types of capillaries: continuous capillary, fenestrated capillary, sinusoidal capillary

Continuous capillaries: Uninterrupted/complete endothelium and continuous basement membrane (basal lamina)

- Tight junctions between adjacent endothelial cells. Often incomplete in capillaries, leaving intercellular clefts that allow for the exchange of water and other very small molecules between the blood plasma and the interstitial fluid

- Have the lowest permeability of all capillary types allowing the exchange of

water, small solutes, and lipid-soluble material only

- Plasma proteins, other large molecules, platelets and blood cells cannot pass

through continuous capillaries

- Found in most tissues

- Pericytes: lie external to the endothelium; may help stabilize the walls of

blood vessels and help regulate blood flow through capillariesFenestrated capillaries: Endothelial cells have numerous fenestra or pores

- Fenestra → membrane-lined cylindrical conduits that run completely through the endothelial cell, from the capillary lumen to the interstitial space

- Surrounded by an intact or complete basement membrane

- Fenestra or pores allow for the rapid exchange of water and solutes, including

larger solutes such as small peptides

- Found in tissues where capillaries are highly permeable, such as endocrine organs, the choroid plexus, the GI tract and the kidneys

- Lipid-insoluble molecules may move through intercellular clefts as well as

through the fenestrae

- Fenestrae make this type of capillary much more permeable than continuous

capillariesSinusoids (sinusoidal capillaries): Large diameter, flattened and irregularly shaped. Called discontinuous capillaries

- Have very large fenestrae and large gaps between adjacent endothelial cells

- Basement membrane very thin or absent

- Allow the free exchange of water and solutes, including large substances such as red blood cells, cell debris, and plasma proteins

- Found only in liver, bone marrow and spleen

Microcirculation

Capillaries are part of the microcirculation, or the circulation of blood through the

smallest vessels in the bodyThese vessels includes arterioles, metarterioles, capillaries, venules and veins

A capillary bed can be supplied by more than one arteriole

- If one arteriole becomes blocked, blood can enter the capillary bed by another arteriole

- Blood flow to capillary beds is variablePrecapillary sphincters → ring of smooth muscle which guards the entrance to the capillary

- Contract and relax in response to local conditions to alter the flow of blood in the capillary beds

- Receive no innervationIn the microcirculation, capillaries branch from arterioles or metarterioles

Metarterioles: also called precapillary arterioles; small blood vessels arising from an arteriole, pass through a capillary network and empty into a venule; contain smooth muscle cells enabling them to regulate blood flow by changing diameter; are not ‘true’ capillaries as they have smooth muscle cells

Our body redirects our blood flow depending on our body’s needs by increasing and decreasing blood flow to different capillary beds

Capillary exchange

Materials are exchanged across the walls of capillaries by diffusion, vesicle transport or bulk flow

Blood flows very slowly through capillaries to maximize the time for the exchange of substances between the plasma and the interstitial fluid

Diffusion: net movement of substances from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration

- Diffusing substances have only a short distance to travel across capillaries, as

capillaries have a small diameter and have a thin capillary wall- Substances that are lipid-soluble can diffuse across the plasma membrane of endothelial cells

- Substances that are lipid-insoluble must move through a water-filled channel (intercellular cleft, fenestrae found in fenestrated capillaries and sinusoids, or

fused vesicle channels)Transcytosis: a process involving vesicles in which endothelial cells pick up material on one side of the plasma membrane by pinocytosis or receptor-mediated endocytosis, transport the vesicles across the cell, and discharge the material on the other side by exocytosis

- Vesicles may fuse together to form a water-filled channel, called a fused vesicle channel, from one side of the endothelial cell to the other through which

substances may move

- Substances move through the fused vesicle channel by diffusionBulk flow: the movement of protein-free plasma across the capillary wall

- Various constituents of the fluid cross the capillary wall in bulk, or as a unit

- During bulk flow, the quantity of solutes moving across capillary walls in the

plasma is extremely small compared to the much larger transfer of solutes that

occurs by diffusion

- The function of bulk flow is not the exchange of nutrients and metabolic

end products across capillary walls but rather the distribution of the extracellular fluid volume (ie. Bulk flow is important for distribution of extracellular fluid volume and less important for exchange of nutrients and metabolic end products)

- Extracellular fluid includes the plasma and the interstitial fluid. Normally, there is more interstitial fluid than plasmaFiltration → movement of protein-free plasma by bulk flow from the capillary plasma to the interstitial fluid through water-filled channels

Reabsorption → movement of protein-free plasma by bulk flow from the

interstitial fluid to the capillary plasmaThe concentration of solutes in the filtered fluid, with the exception of plasma proteins, is the same as in the plasma

Bulk flow; pressures

Bulk flow is driven by different pressures; it occurs because of differences in the

hydrostatic and colloid osmotic pressures between the capillary plasma and the

interstitial fluidHydrostatic pressure: the force of a fluid against a membrane

- Capillary hydrostatic pressure → the pressure exerted by the blood on the

inside of the capillary walls and forces protein-free plasma out of the capillaries into the interstitial fluid

- Interstitial fluid hydrostatic pressure → is the pressure exerted on the outside of the capillary wall by the interstitial fluid and forces fluid into the capillaries; this

pressure is very negligible and does not contribute significantly to bulk flowColloid osmotic pressure → the osmotic pressure due to the presence of impermeable proteins

- As a result the concentration of proteins will not be equal in the plasma and in the interstitial fluid

- The difference in protein concentration between the plasma and the interstitial fluid creates an osmotic force; the proteins draw fluid towards them, into the compartment that they occupy, as water moves from a region of high water concentration to a region of low water concentration

- Solutes such as sodium or potassium do not have this effect as they can move across capillary walls through pores or water-filled channels (have equal concentrations in the plasma and in the interstitial fluid)

- Blood colloid osmotic pressure → the osmotic pressure due to the presence of a large number of non-permeating plasma proteins, such as albumin, within the

blood; proteins pull water into the capillaries

- Interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure → is the result of the small amount of

proteins which do escape the capillaries into the interstitial fluid; favors fluid

movement out of the capillary, but it is very small and does not contribute

significantly to bulk flow

Bulk flow; net exchange pressures

Net exchange pressure = PC + πIF – PIF – πC

- P = hydrostatic pressure; pi = colloid osmotic pressure; C – capillary; IF -

interstitial fluid

- The net pressure is the sum of the outward pressures and the inward pressures

- Outward pressures = capillary hydrostatic pressure and the interstitial fluid osmotic pressure

- Inward pressures = the osmotic force due to the plasma protein concentration and the interstitial fluid hydrostatic pressureHydrostatic pressure will decrease as blood moves along the length of the capillary towards from arterial to venous end

Blood colloid osmotic pressure remains the same along the length of the

capillaryArterial end of the capillary:

- Capillary hydrostatic pressure (arterial end): Pushes fluid out of the capillary

- Blood colloid osmotic pressure (due to proteins in the blood): Draws fluid into the capillary

- Interstitial fluid hydrostatic pressure: ~ 0mmHg. Does not cause movement of fluid

- Interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure ~ 3mmHg. Causes fluid to move out of the capillary

- At the arterial end of the capillary: net pressure is a positive number and favors filtration of fluid from the capillary into the interstitial fluidVenous end of the capillary:

- Capillary hydrostatic pressure (venule end): Pushes fluid out of the capillary

- Blood colloid osmotic pressure (due to protein in the blood): Draws fluid into the capillary (as it did at the arterial end)

- Interstitial hydrostatic pressure: ~ 0 mmHg. Does not cause the movement of fluid (same as arterial)

- Interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure: ~ 3 mmHg. Causes fluid to move out of the capillary (same as arterial)

- At the venous end of the capillary: net pressure is a negative number and favors the absorption of fluid from the interstitial fluid into the capillaryThe four factors that determine the net filtration pressure are termed the Starling forces

The capillary hydrostatic pressure changes significantly along the length of the capillary due to friction between the flowing blood and the capillary wall

The transition between filtration and reabsorption occurs where the sum of the

outward pressures is equal to the sum of the inward pressures

- As the hydrostatic pressure at the arterial end is greater than at the venous end of the capillary, this transition does not occur in the exact middle between the arterial and venous ends of the capillary, but occurs closer to the venous end of the capillaryMore filtration than absorption occurs along the length of the capillary

The difference excess filtered fluid moves back into the lymphatic system to eventually return to the venous system (more fluid is filtered than absorbed; excess is returned to the lymphatic system)

Venous system

At rest, ~ 60% of the blood volume is found in the venous system (liver, bone marrow, and skin have a large volume of blood)

Veins:

- Expand and recoil passively with changes in pressure

- High capacitance vessels as can store large amounts of blood

- Highly distensible, expanding easily at low pressures and have little elastic recoil

- Reservoir for bloodVenous system is a low pressure system

Venous valves → composed of two leaflets or folds; prevent the backflow of blood into the capillaries

- Aid in returning blood to the heart and ensuring blood flows in one direction

- Compartmentalize the blood within the veins, so the weight of the blood is

distributed between the compartmentsVaricose veins: occur when the walls of the veins near the valves become weakened or stretched and the valves do not work properly; blood pools in the veins and vessels become distended

Smooth muscle in veins: Innervated by sympathetic neurons which cause contraction smooth muscle to increase pressure

Skeletal muscle pump: Compresses veins. Venous pressure increases, forcing more blood back to heart

Respiratory pump (will talk about more in respiration): Inspiration causes an increase in venous return

Relationship between venous return and the Frank-Starling law:

- Skeletal muscle pump, respiratory pump and increased sympathetic activity to

venous smooth muscle will increase venous return by increasing venous pressure

- Increased venous return to the heart will increase the end-diastolic volume

- Now we have the Frank Starling mechanism: increase EDV → increase

cardiac fiber length → increase force during contraction → increase SV

Lymphatic system

Lymphatic system: consists of a system of small organs, called lymph nodes, and tubes, called, lymphatic vessels, through which lymph flows

Lymphatic capillaries:

o Distinct from blood capillarieso Also made of only a single layer of endothelial cells resting on a basement membrane

o Have large water-filled channels that are permeable to all interstitial fluid

components, including proteins

o No vessels flow into them (ie they have a round ‘end’)

o Interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic capillaries through bulk flow

o Extend into the interstitial space surrounding tissue cells

o Thin walls to allow tissue fluid, or interstitial fluid, to enter the lymphatic

capillariesLymphatic capillaries empty into lymph vessels