Week ten: constructivism

1/40

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

41 Terms

Why is constructivism so different to the other theories?

Constructivism is the newest but most dynamic of main IR theories.

While liberalism and realism have taken bearings from developments in economic and political theory, constructivism is rooted in insights from social theory.

Constructivists do not predict outcomes or offer definitive advice on how states should act, but instead, constructivism is best understood as a set of wagers about the way social life is put together, revolving around the fundamental importance of meaning to social action:

What does Wendt say about constructivism?

“People act toward objects, including each other on the basis of the meanings those objects have for them” (Wendt).

What is the core concern of constructivism?

Identity

What do constructivists argue about the goals held by states and actors?

They argue the goals held by a state or other actor emerge from the actor’s identity, and much constructivist research deals with an understanding of themselves and the roles and purposes they serve in the world.

This translates into goals and interests in foreign policy. Meaning-making and identity-shaping intervene between material factors and strategic decisions.

What do constructivists mean when they say identity is ‘inter-subjective’?

It doesn’t exist physically, and it doesn’t exist in our minds, but rather ‘between us’—in social interactions that people have with each other. Interactions are on the basis of category distinctions.

An implication of this is that identity comes before and forms the basis of interests because we hold certain values and ideals and belong to certain communities—engaging in some courses and not others.

For a constructivist, social life is about claims: politics, whether ‘domestic’ or ‘international’, is primarily about power struggles between people making different and competing kinds of identity claims.

What do constructivists say about who identity includes?

Identity is not just about ‘selves’ but also about ‘not-self’—people who are outside, beyond boundaries, beyond borders of a state.

Consider the way we categorise religions; people could be ‘heretics,’ ‘terrorists’ or ‘primitives’—the self-other relationship has configured certain kinds of implication for action.

What are the roles of norms and rules according to constructivists?

For constructivists, rules and norms are constitutive in that they specify not only what an actor can do, but what kind of actor they actually are.

Thus, sovereignty is a constitutive rule of the contemporary global political system that defines who are the legitimate players on the international stage.

Realists and liberals also acknowledge the existence and importance of rules and norms, but treat them differently.

How do constructivists conceptualise ‘self-other’s?

Some self-other relationships are durable because they are codified into rules and norms governing interactions between entities in world politics.

Where do constructivists agree with realists and liberals in terms of the contemporary international system?

When it comes to the contemporary international system, constructivists agree with realists and liberals that the present order of things is largely, though not exclusively, dominated by sovereign states interacting under conditions of anarchy.

But anarchy is conceived as a different type of anarchy—because in the social space between states you have international law, state identities and many other self-other relationships, a very complex, busy space.

What do constructivists mean when they say anarchy is thick?

there are rules and norms states must internalise.

Some of these rules and norms are so established they’re called ‘international institutions’—used in similar application to ‘marriage institution’, in that it’s a set of socially established expectations for how a particular friendship ought to work.

What do constructivists believe about institutions and the way they work?

Constructivists claim institutions can also be seen working at the level of international society—the institution of the balance of power: a management strategy by which great powers manage the international system as it changes over time.

It is something for which states and their representatives consciously and deliberately strive, rather than an inevitable outcome of security competition, as in realism.

According to constructivists, what is the balance of power?

if one state does something infringing on another state’s power, the compromised state requires compensation.

How would constructivists analyse colonisation?

It relied largely on ‘self/other’ narratives of superiority and inferiority that supported imperial identities of great powers.

The institution of the balance of power is closely linked to the identity of being a ‘great power’, and hence for constructivism, the identity ‘great power’ comes with certain rights and privileges, including consultation and compensation—essentially making them managers of the international system.

How do constructivists analyse war?

War for constructivists is a social institution that compromises these rules, laws, etc.

We have practices, protocols of the persecution of war, and binding sets of expectations.

What is the relevance of international law to constructivists?

For constructivists, international law does have a backbone because it establishes a certain set of expectations and standards.

So when people do violate these laws, they risk prosecution—one of the things people can do with law.

They provide standards and expectations, not guarantees of specific rule-governed behaviour.

Economic sanctions are a key example of this being upheld (Russo-Ukraine conflict).

How do constructivists understand change?

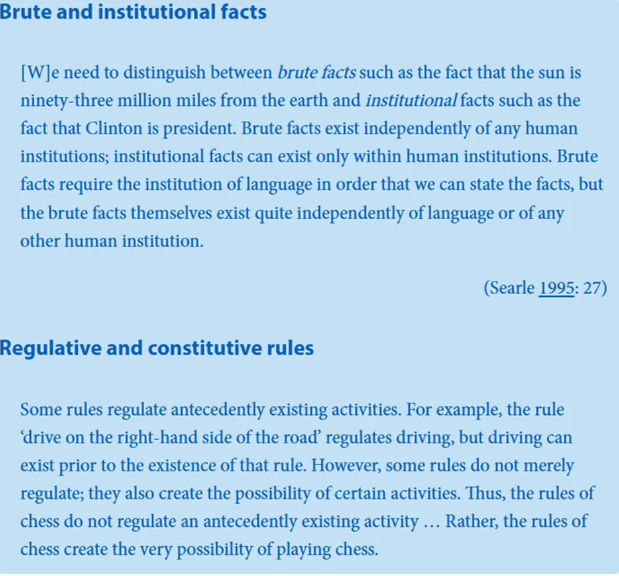

Brute facts vs Institutional facts

According to constructivists, how is political stability created?

If we didn’t have the organisation that already exists, the format of world politics could be organised in a radically different way.

For constructivists, stability is not presumed—the international system requires effort to sustain, activity of multiple actors.

There is a lot at stake in this idea that social arrangements (including international systems) are produced by social action rather than being natural or brute facts.

Hence, if everyday practices constitute the rules and norms of the international system, they also create and maintain the actors within that system.

For constructivists, the modern state is an institution that shapes our capacity to affirm collective and particular identities, and the site of sovereignty.

Norms like territorial integrity, non-interference, and formal equality among states are closely related to sovereignty and statehood.

What are state interests according to constructivists?

Remember that for constructivists, state interests are not exogenous or objective, but informed by identities—in particular identity claims and contests, and the quest for ontological security—security of being rather than just physical state.

Both identity and everyday practices become a key for states to maintain biographical continuity and avoid existential anxiety, and some states are not naturally equipped with legal or ‘Westphalian’ sovereignty, but this kind of sovereignty is ‘imposed’ upon them.

According to constructivists, what is practice theory?

Consider practice theory—it observes that a practice entails ‘indeterminacy and undecidability’, while social network theorists define ‘structures as emergent properties of persistent patterns of relationships among agents that can define, enable and constrain those agents’.

States can also be socialised—taught to conform behaviour to certain norms:

Often seen throughout world politics, sometimes informally (i.e., joining the EU and having to uphold its legal policy).

State identity can also change internally, as different people have different visions of the state’s identity.

What do constructivists think about the socialisation of state identities and ideas of security community?

Constructivists hence believe that the socialisation of state identities can sometimes bring about greater peace and stability, such as a security community with positive identification with each other.

Constructivists are interested in the formation of security communities because they can dramatically change the context in which states interact—modify and ameliorate the condition of interstate anarchy.

How does security community change the context of interaction?

Being in a security community changes the context of interaction:

Disputes are more likely to be solved when they arise.

One necessary condition, however, is some sort of shared narrative of commonality—that they belong together and are willing to share a common future.

According to Wendt, what is the main argument of ‘anarchy is what states make of it?’

We should not necessarily treat interests and identity as given. Although Wendt agrees with a statist view, he argues that an important field of research should treat state interests and identity as the dependent variable.

Wendt concedes that there are those who study how first- and second-image factors affect state identity and interests.

He wants us to study how anarchy affects state identities and interests.

What does Wendt say a key flaw of realism, neoliberalism and constructivism is?

Realism's shortcoming is its failure to do this (although Wendt agrees that realist game theory is entirely appropriate in situations where we can assume that identities are constant, at least in the short term).

Neoliberalism's failure is that it has sought to explain cooperation by focusing on process, but it has not sufficiently accounted for systemic variables.

Constructivism's failure is that it gets too bogged down in epistemological debates without looking enough at how identities are formed in practice.

In short, we need a combination of neoliberalism and constructivism that will study how the system affects state identities and interests.

What does Wendt argue for in his constructivist approach to self help?

Wendt argues for a constructivist approach to the concept of self-help.

He argues that international institutions (here the institution is self-help) can change state identities and interests.

He argues that the concept of self-help as defined by realists (mainly Waltz) originates from the interaction of the units in the system, not from anarchy.

This conception conflicts with structural, deterministic arguments advanced by realists, where anarchy is the key explanatory variable that drives interactions.

Wendt says that states interact with each other and, based on the results of that interaction, can become characterized by self-help, but this result does not necessarily need to follow.

What does Wendt argue in terms of self-help identities?

He suggests one possible sufficient cause of self-help identities:

If a predatory state emerged, it would force other states to respond.

But even this depends on prior identity.

If the predatory state emerges into a system that already has a strong collective security identity, then it would be defeated without changing the dominant identity.

So, think NATO.

Realism would predict that, with the Soviet threat gone, the alliance will break up as states become suspicious of one another.

But Wendt would seem to suggest that a collective identity can continue.

What does Wendt say about sovereignty?

Sovereignty is a norm, and it has been self-enforcing so far.

(Look what happened to Hitler and Napoleon when they went against it.)

It has changed our interests, so that we think we need to defend territorial boundaries—even when letting a piece of territory go might be better for our security.

What does Wendt say about the evolution of cooperation and creation of norms?

Evolution of Cooperation

Europe’s long experience with cooperation during the Cold War may have fundamentally changed its identity.

This created a "European" identity that will persist despite the collapse of the Soviet threat and the renewed vigor of Germany.

What Does “Construction” Mean?

Interested in “identity and interest formation” (Wendt 1992, p.393, emphasis added)

Malleability of political reality

Does not deny reality

Does not imply voluntarism

Different constructivisms (“thin” to “thick” / “critical”)

Wendt (1992): Anarchy is What States Make of It

Wendt (1992): Anarchy is What States Make of It

Engages explicitly with Waltzian neorealism to argue that “self-help and power politics do not follow either logically or causally from anarchy and ... if today we find ourselves in a self-help world, this is due to process, not structure” (Wendt 1992, p.394)

Focuses on intersubjective meanings:

“A fundamental principle of constructivist social theory is that people act toward objects, including other actors, on the basis of the meanings that the objects have for them. States act differently toward enemies than they do toward friends because enemies are threatening and friends are not. Anarchy and the distribution of power are insufficient to tell us which is which.” (Wendt 1992, pp.3967)

The Three “I”s of Social Constructivism

INTERESTS

IDENTITIES

INSTITUTIONS

what are interests

Interests are varied and variable (not simply “defined in terms of power” or motivated by self-help)

“Actors do not have a ‘portfolio’ of interests that they carry around independent of social context; instead, they define their interests in the process of defining situations” (Wendt 1992, p.398)

what are identities

“If society ‘forgets’ what a university is, the powers and practices of professor and student cease to exist; if the United States and Soviet Union decide that they are no longer enemies, ‘the cold war is over’. It is collective meanings that constitute the structures which organize our actions. Actors acquire identities – relatively stable, role-specific understandings and expectations about the self – by participating in such collective meanings” (Wendt 1992, p.397)

what are institutions?

Wendt uses a very broad definition of institutions:

“An institution is a relatively stable set or ‘structures’ of identities and interests. Such structures are often codified in formal rules and norms, but these have motivational force only in virtue of actors' socialization to and participation in collective knowledge. Institutions are fundamentally cognitive entities that do not exist apart from actors' ideas about how the world works. This does not mean that institutions are not real or objective, that they are ‘nothing but’ beliefs. In this way, institutions come to confront individuals as more or less coercive social facts, but they are still a function of what actors collectively ‘know’” (Wendt 1992, p.399)

What is an example of national interest and policy intertwining?

Henry Kissinger: “When you're asking Americans to die, you have to be able to explain it in terms of the national interest” (quoted in Kelly, 1995: 12).

Because 'the national interest' in practice plays these vital roles in the making of foreign policy, and so in determining state actions, it clearly should occupy a prominent place in accounts of international politics. (Weldes 1996, p.276)

Weldes, Jutta (1996) Constructing National Interests, European Journal of International Relations, 2(3): 275-318.

What is a critique of Wendt?

“His analysis does not itself provide an adequate account of national interests for at least one important reason. Wendt's anthropomorphized understanding of the state continues to treat states, in typical realist fashion, as unitary actors with a single identity and a single set of interests (1992: 397, note 21). The state itself is treated as a 'black box', the internal workings of which are irrelevant to the construction of state identities and interests. In Wendt's argument, the meanings which objects and actions have for these unitary states, and the identities and interests of states themselves, are therefore understood to be formed through inter-state interaction (1992: 401). But the political and historical context in which national interests are fashioned, the intersubjective meanings which define state identities and interests, cannot arbitrarily be restricted to those meanings produced only in inter-state relations. After all, states are only analytically, but not in fact, unitary actors” (Weldes 1996, p.280)

What is ‘thick’/critical constructivism?

National interests emerge out of the representations – or, to use more customary terminology, out of situation descriptions and problem definitions – through which state officials and others make sense of the world around them” (Weldes 1996, p.280)

Is Australian strategic structure anglospheric?

Frightened Country (Renouf)

Great and Powerful Friends sought ANZUS (1952)

Fear of Abandonment (Gyngell)

“One of the things this nation must never do is to feel that it must choose between our history and our geography. The treasure of western civilization...is one of the great endowments of being Australian. And yet it is a treasure and an inheritance that does not always go unchallenged in modern Australian society.” (Howard)

AUKUS (2021)

What are the role of norms in international relations

The Role of Norms

Although often violated, norms do matter

Norms can be good or bad

Norm actors can be “entrepreneurs”, neutral, or “antipreneurs” (Bloomfield 2016)

How do norms spread in IR?

Norm “life cycle”: emergence, cascade, and internalisation (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998)

Spiral model of norm diffusion (Risse and Sikkink 1999)

Boomerang model of norm diffusion (Keck and Sikkink 1998)

“Tipping point” (between “emergence” and “cascade” in the “life cycle” model)

What are the politics of norms?

Makes more sense to speak of “norm politics” than straightforward “norm diffusion”

“Some [actors] may adopt norms just because they are Western, and others reject them for just that reason. Ignoring this all too frequent dynamic in our causal explanations is both politically and epistemologically suspect” (Zarakol 2012: 328; see also MacKenzie and Sesay 2012; Jabri 2012; Epstein 2012).

What is the concept of norm translation?

“‘Neither the global set of norms ..., nor the national apparatus that has made a commitment to implement them, nor the everyday life situations in which women’s rights are supposed to work are conceptually separate from each other or ever fixed in meaning.” (Zwingel 2012: 121)