Antitrust Policy Quiz 3

1/43

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

44 Terms

Vertical Control

Downstream firms are the customers of the upstream firms.

Types of vertical control

-choice of price is endogenous

-price discrimination (both up and downstream)

-mergers

-entry

Why don’t manufacturers engage in direct marketing

-increasing returns to distribution due to shopping needs/travel costs

-choice of variety

-demand for service

-integration of complementary products

-different geographical markets

Responsibilities of the downstream firm

determination of final price

promotional effort

placement of product on store shelves

promotion and placement of competing products

technological inputs

Downstream firms’ actions can effect the upstream firm

vertically integrated profit

meximum industry or aggregate profit

Types of Vertical Restraints

Exclusive territory-dealer/ distributor/ retailer is

assigned a (usually geographic) territory by the

manufacturer/ upstream firm and given monopoly rights to

sell in that area

Exclusive dealing-a dealer/ distributor/ retailer is not

allowed to carry the brands of a competing upstream firm.

Full-line forcing-a dealer is committed to sell all the

varieties of the manufacturer’s products rather than a

limited selection. (i.e., the upstream firm ties all its

products to sell to the downstream firm).

Resale Price Maintenance-dealer commits to a retail

price or a range of retail prices for the product. This can

take the form of either minimum resale price maintenance

or maximum resale price maintenance. Equivalently, firms

can engage in quantity forcing or quantity rationing.

Contractual arrangements-pstream and downstream

firms write contracts to provide greater flexibility in the

transfer of the product. Profit sharing and revenue sharing

are the most common, which we’ll see soon. Also,

franchising arrangements.

Typical outline of vertical control

1) Basic Framework

2) Externalitites between downstream and upstream firms (max resale price maintenance, quantity forcing, contractual arrangements, full-line forcing)

3) Downstream Moral Hazard or Externalities from INtraband competition (exclusive territorities, minimum rpm, quantity rationing)

Interbrand comp (exclusive dealing or possibly full-line forcing)

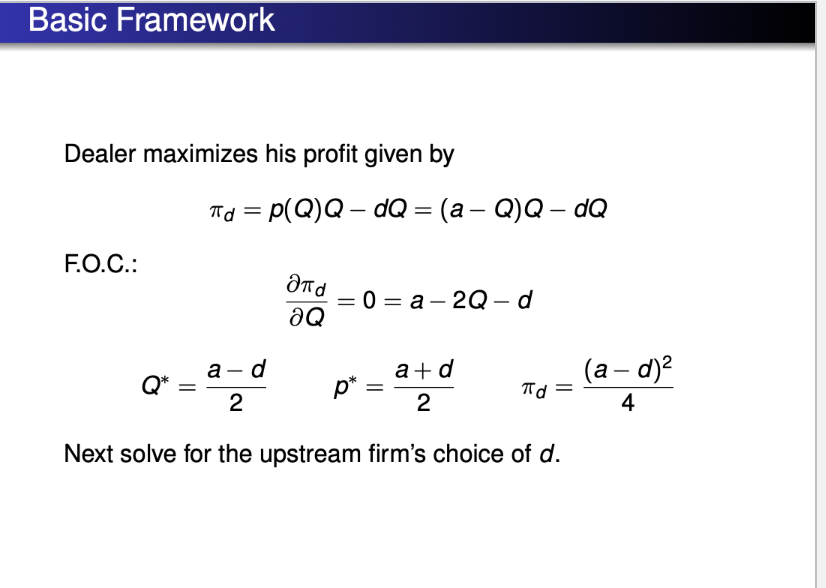

Basic framework

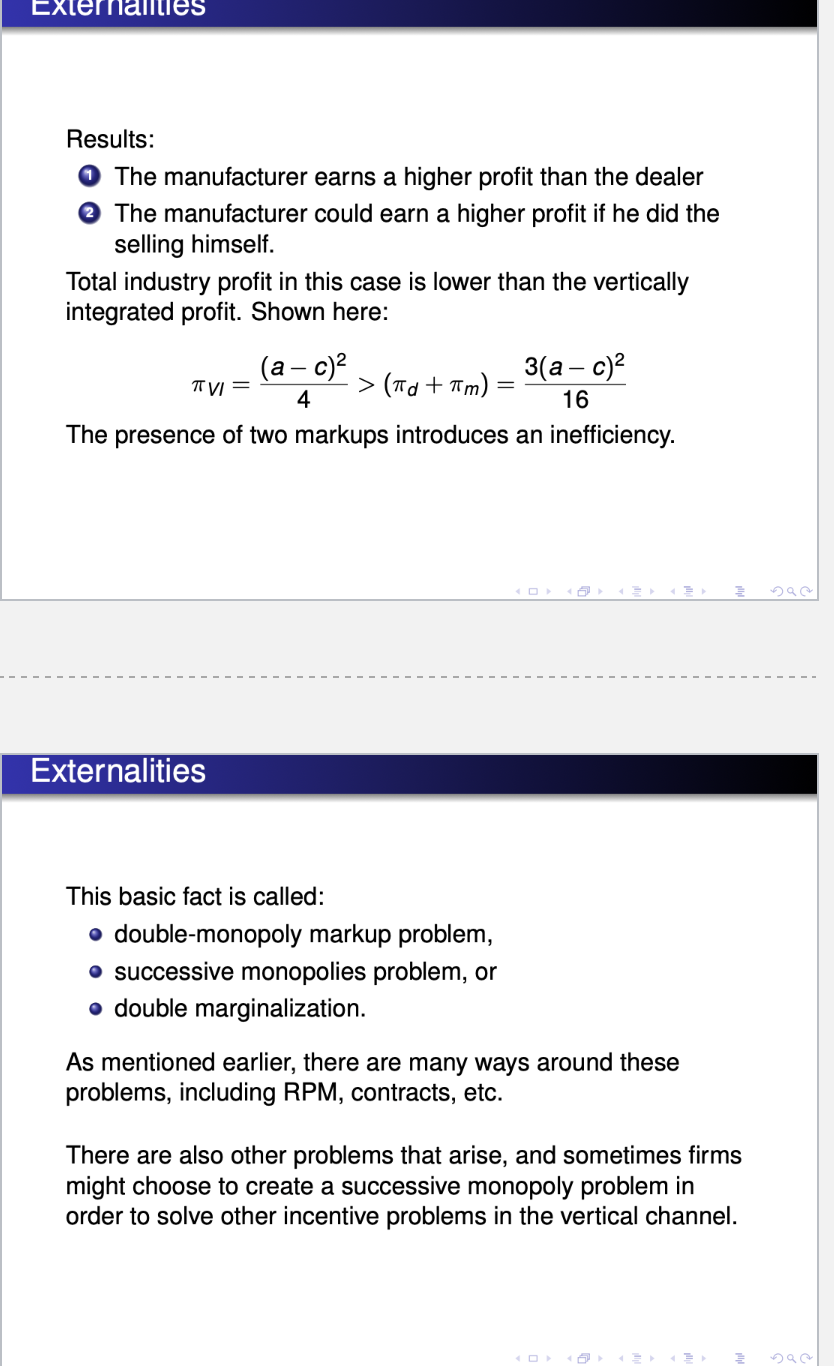

Externalities

double marginalization

doubke markup

can avoid with rpm contracts and other techniques

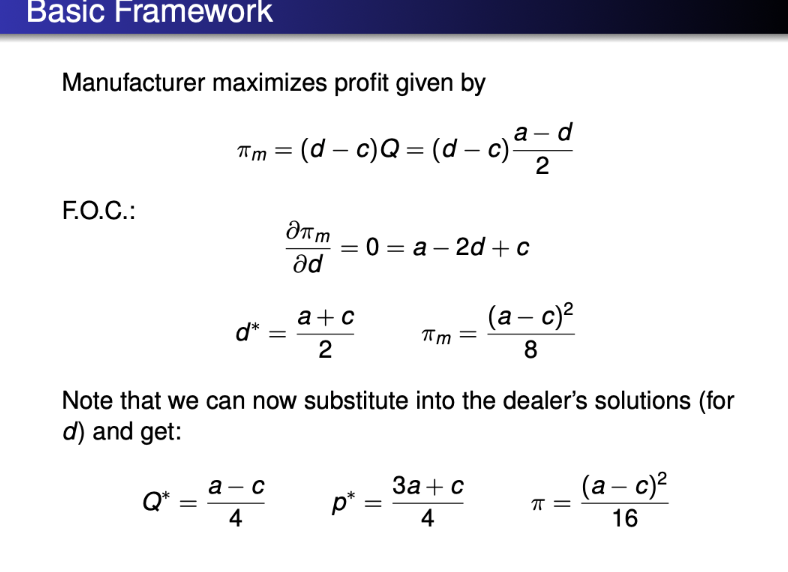

Maximum Resale Price Maintenance/Quantity Forcing

Contractual Arrangements

lots of things, lease the good to downstream firm, pergaps use profit sharing contracts

Profit-sharing or revenue-sharing contracts

like a two-part tariff. Instead of charging linear prices, the manufacturer requires a lump-sum transfer as well as a per-unit charge

Externalities

Downstream Moral Hazard

See notes for this one

Interbrand Competition

Legal Issues

Vertical restrains

Intrabrand Restraints

Imposed by a manufacturer on its own output

-limits on who can sell it, where, at what price

-does not restrain anyone’s ability to carry other suppliers’ output

Interbrand restraint

affects trading partners’ ability/incentive to carry other brands

-exclusivity, tying

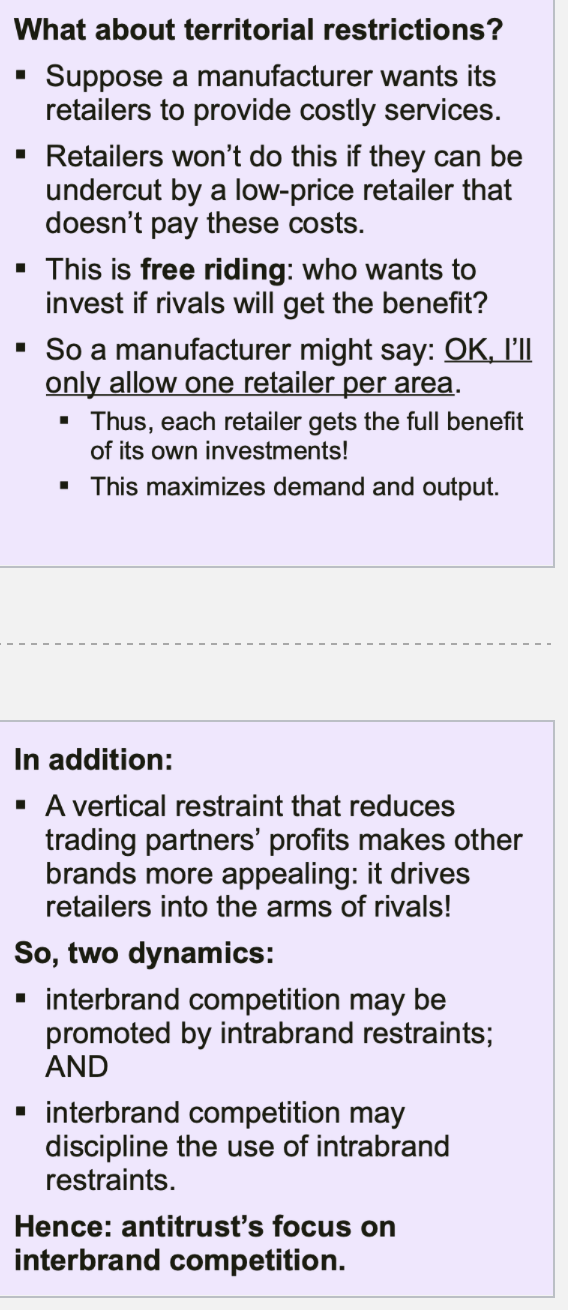

GTE Sylvania

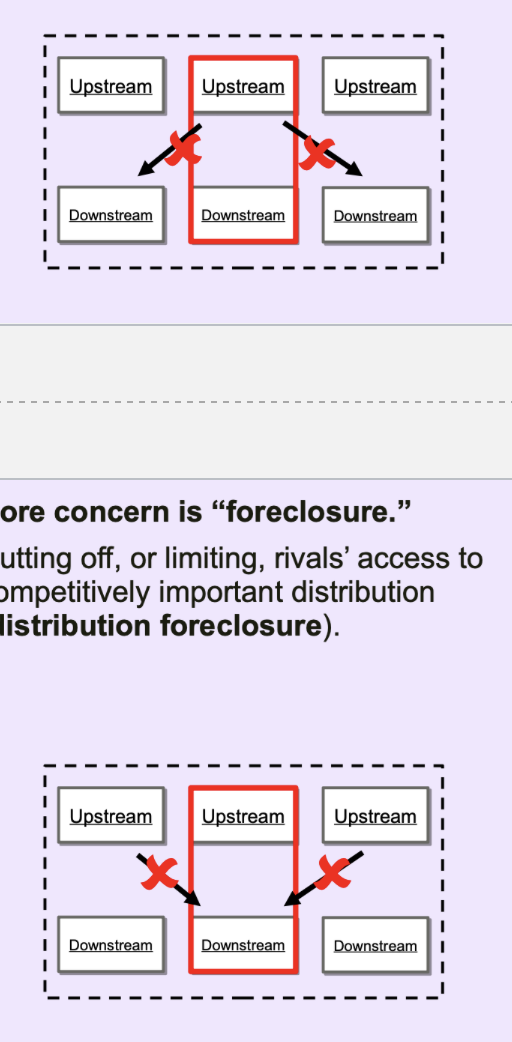

Intrabrand and Interbrand interaction

Territorial restrictions

US v Schwinn

-nonprice restraints

-schwinn made bikes and was losing share so changed distribution plan

1) Smaller set of distributors

2) Each had an exclusive territory

3) Required to give at least equal prominence to Schwinn bikes as to competitors

4) Some sales trhough consignment others through resale

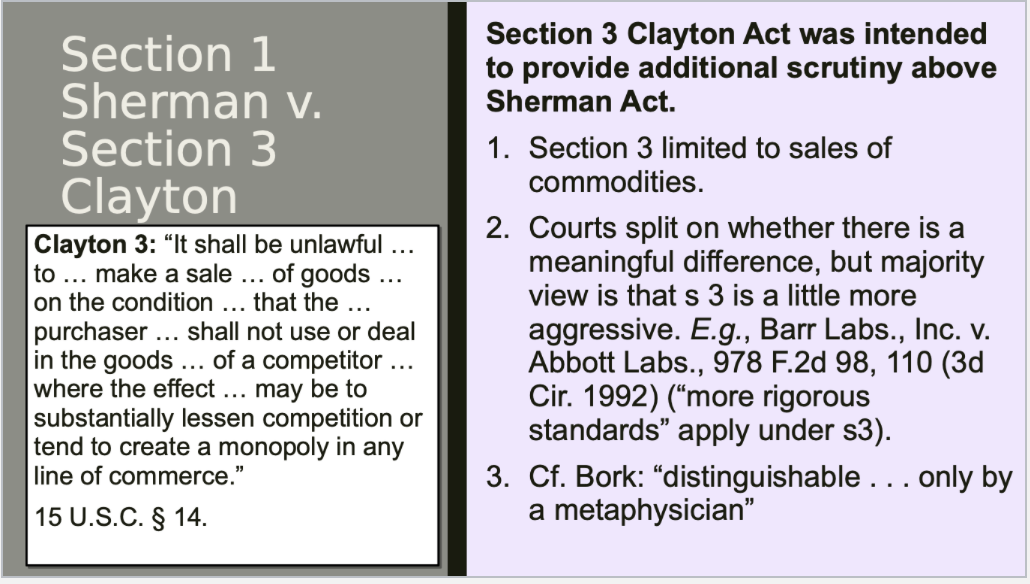

Continental TV v GTE Sylvania

1. GTE Sylvania made TVs: national

share 1-2%.

2. It phased out its wholesalers and

started selling to a limited

number of retailers in each area.

3. “An acknowledged purpose of the

change was to decrease the

number of competing Sylvania

retailers in the hope of attracting

the more aggressive and

competent retailers thought

necessary to the improvement of

the company’s market position.”

4. A terminated franchisee sued.

At trial:

Sylvania asked for rule of reason

jury instruction; didn’t get it; lost.

Supreme Ct:

“Interbrand competition is . . . among

the manufacturers of . . . television

sets in this case and is the primary

concern of antitrust law.”

“Vertical restrictions promote

interbrand competition by allowing

the manufacturer to achieve certain

efficiencies in . . . distribution[.]”

R of R for all nonprice vertical

restraints.

SCHWINN OVERRULED

![<p>1. GTE Sylvania made TVs: national<br>share 1-2%.<br>2. It phased out its wholesalers and<br>started selling to a limited<br>number of retailers in each area.<br>3. “An acknowledged purpose of the<br>change was to decrease the<br>number of competing Sylvania<br>retailers in the hope of attracting<br>the more aggressive and<br>competent retailers thought<br>necessary to the improvement of<br>the company’s market position.”<br>4. A terminated franchisee sued.</p><p><br>At trial:<br> Sylvania asked for rule of reason<br>jury instruction; didn’t get it; lost.<br>Supreme Ct:<br> “Interbrand competition is . . . among<br>the manufacturers of . . . television<br>sets in this case and is the primary<br>concern of antitrust law.”<br> “Vertical restrictions promote<br>interbrand competition by allowing<br>the manufacturer to achieve certain<br>efficiencies in . . . distribution[.]”<br> R of R for all nonprice vertical<br>restraints.<br>SCHWINN OVERRULED</p><p><br></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/1ff77d98-b0c4-4dbd-bc06-8ae933ee1e53.jpeg)

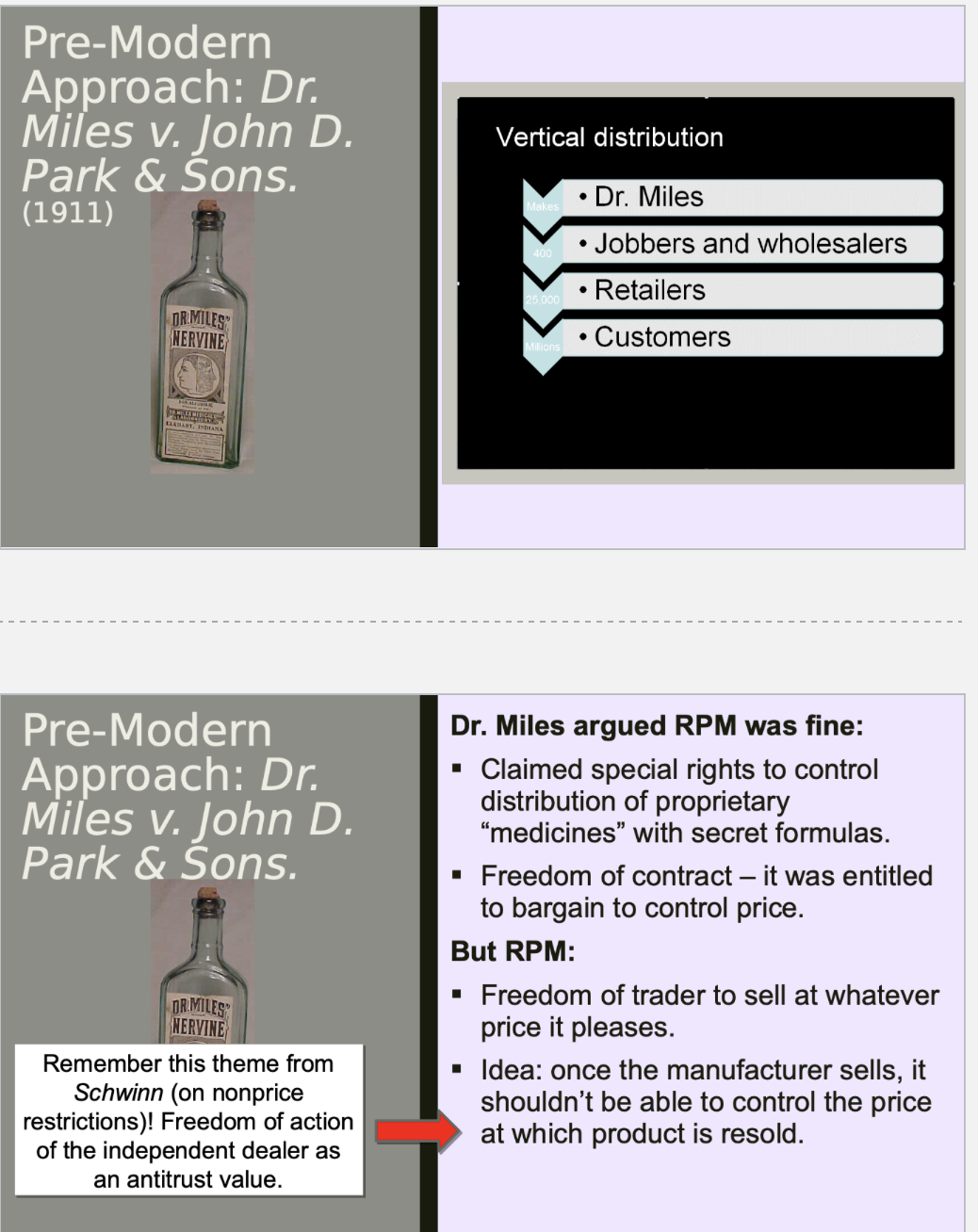

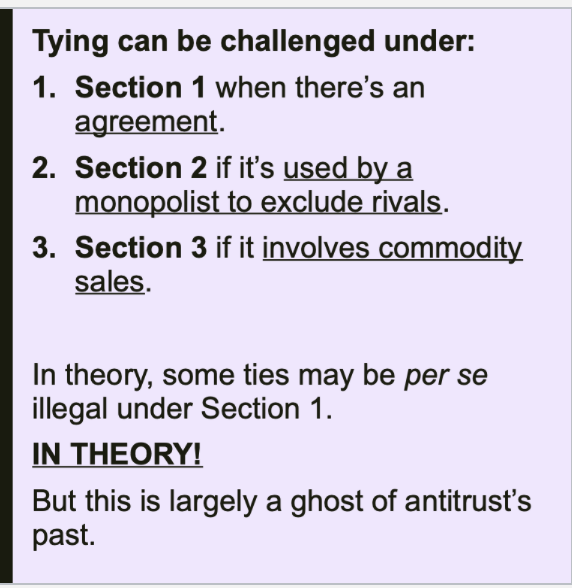

Intrabrand Price restraints: Resale Price Maintenance

Court held:

1. Dealer freedom is an important

value in antitrust analysis.

“If there be an advantage to the

manufacturer in the maintenance of

fixed retail prices, the question

remains whether it is one which he is

entitled to secure by agreements

restricting the freedom of trade on

the part of dealers who own what

they sell.”

Court held:

2. Manufacturer RPM and a dealer

price-fixing cartel are equivalent

– and so must be treated alike.

“Dr. Miles can fare no better with its

plan of identical contracts than could

the dealers themselves if they

formed a combination and

endeavored to establish the same

restrictions.”

3. And a dealer price-fixing cartel

would be super illegal.

“[A]greements or combinations

between dealers, having for their sole

purpose the destruction of competition

and the fixing of prices, are injurious to

the public interest and void.”

= therefore RPM must be per se

illegal.

How can this be per se illegal?

1. Dr Miles could do this lawfully if

its retailers were agents.

“[B]y a slight change in the form of the

contract the plaintiff can accomplish

the result in a way that would be

beyond successful attack. If it should

make the retail dealers [agents of Dr.

Miles], and retain the title until the goods

left their hands, I cannot conceive that

even the present enthusiasm for

regulating the prices to be charged by

other people would deny that the owner

was acting within his rights.”

2. Presumption against interfering

with business operations.

“I think that at least it is safe to say

that the most enlightened judicial

policy is to let people manage their

own business in their own way,

unless the ground for interference is

very clear.”

3. Shouldn’t interfere: intrabrand

competition isn’t important.

“[W]e greatly exaggerate the

value . . . of competition in

production or distribution . . . as

fixing a fair price. . . . As soon as the

price of something that we want goes

above the point at which we are willing

to give up other things to have that, we

cease to buy it and buy something else.

. . . The Dr. Miles Medical Company

knows better than we do what will

enable it to do the best business.”

4. And why protect dealers’ rights to

violate contracts and undermine

sales of Dr Miles’s own product?

“I cannot believe that in the long run the

public will profit by this court permitting

knaves to cut reasonable prices for

some ulterior purpose of their own,

and thus to impair, if not to destroy, the

production and sale of articles which it

is assumed to be desirable that the

public should be able to get.

![<p>Court held:<br>1. Dealer freedom is an important<br>value in antitrust analysis.<br>“If there be an advantage to the<br>manufacturer in the maintenance of<br>fixed retail prices, the question<br>remains whether it is one which he is<br>entitled to secure by agreements<br>restricting the freedom of trade on<br>the part of dealers who own what<br>they sell.”</p><p>Court held:<br>2. Manufacturer RPM and a dealer<br>price-fixing cartel are equivalent<br>– and so must be treated alike.<br>“Dr. Miles can fare no better with its<br>plan of identical contracts than could<br>the dealers themselves if they<br>formed a combination and<br>endeavored to establish the same<br>restrictions.”</p><p>3. And a dealer price-fixing cartel<br>would be super illegal.<br>“[A]greements or combinations<br>between dealers, having for their sole<br>purpose the destruction of competition<br>and the fixing of prices, are injurious to<br>the public interest and void.”<br>= therefore RPM must be per se<br>illegal.</p><p></p><p>How can this be per se illegal?<br>1. Dr Miles could do this lawfully if<br>its retailers were agents.<br>“[B]y a slight change in the form of the<br>contract the plaintiff can accomplish<br>the result in a way that would be<br>beyond successful attack. If it should<br>make the retail dealers [agents of Dr.<br>Miles], and retain the title until the goods<br>left their hands, I cannot conceive that<br>even the present enthusiasm for<br>regulating the prices to be charged by<br>other people would deny that the owner<br>was acting within his rights.”</p><p>2. Presumption against interfering<br>with business operations.<br>“I think that at least it is safe to say<br>that the most enlightened judicial<br>policy is to let people manage their<br>own business in their own way,<br>unless the ground for interference is<br>very clear.”</p><p>3. Shouldn’t interfere: intrabrand<br>competition isn’t important.<br>“[W]e greatly exaggerate the<br>value . . . of competition in<br>production or distribution . . . as<br>fixing a fair price. . . . As soon as the<br>price of something that we want goes<br>above the point at which we are willing<br>to give up other things to have that, we<br>cease to buy it and buy something else.<br>. . . The Dr. Miles Medical Company<br>knows better than we do what will<br>enable it to do the best business.”</p><p>4. And why protect dealers’ rights to<br>violate contracts and undermine<br>sales of Dr Miles’s own product?<br>“I cannot believe that in the long run the<br>public will profit by this court permitting<br>knaves to cut reasonable prices for<br>some ulterior purpose of their own,<br>and thus to impair, if not to destroy, the<br>production and sale of articles which it<br>is assumed to be desirable that the<br>public should be able to get.</p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/f9ce1efc-4cb2-4b36-8850-8280a8b3160d.jpeg)

Dr Miles Medical Co v John D Park and Sons (1911)

Albrecht

What happened in Albrecht?

1. Herald Co. published the “Globe-

Democrat,” a newspaper with a

weird name.

2. It gave its delivery carriers

exclusive territories, but it was

worried about retailer overcharging,

so it set maximum resale prices.

3. Albrecht overcharged so Herald

hired another carrier to sell at the

lower price.

4. Albrecht sued - and won! Court

held: maximum RPM is per se

illegal!

Why is this “illegal price fixing”?

1. “Maximum prices may be fixed too

low for the dealer to furnish

[valuable] services[.]

2. “Maximum price fixing may channel

distribution through a few large or

specifically advantaged dealers.”

3. “[I]f the actual price charged under a

maximum price scheme is nearly

always the fixed maximum price . . .

the scheme [resembles minimum

RPM].”

Harlan dissent

1. Not everything is per se illegal!

“It has long been recognized that one of

the objectives of the Sherman Act was

to preserve, for social rather than

economic reasons, a high degree of

independence, multiplicity, and variety

in the economic system.”

“Recognition of this objective does not,

however, require this Court to hold

that every commercial act that

fetters the freedom of some trader is

a proper subject for a per se rule in

the sense that it has no adequate

provable justification.”

2. This is Herald Co’s unilateral

distribution policy, not an

agreement with the other carriers.

“A firm is not ‘combining’ to fix its own

prices or territory simply because it

hires outside accountants, market

analysts, advertisers by telephone or

otherwise, or delivery boys.

3. And it’s not been shown to be

harmful here!

“The question in this case is not

whether dictation of maximum prices is

ever illegal, but whether it is always

illegal. . . . The best the Court can do is

to list certain unfortunate

consequences that maximum price

dictation might have in other cases but

was not shown to have here.

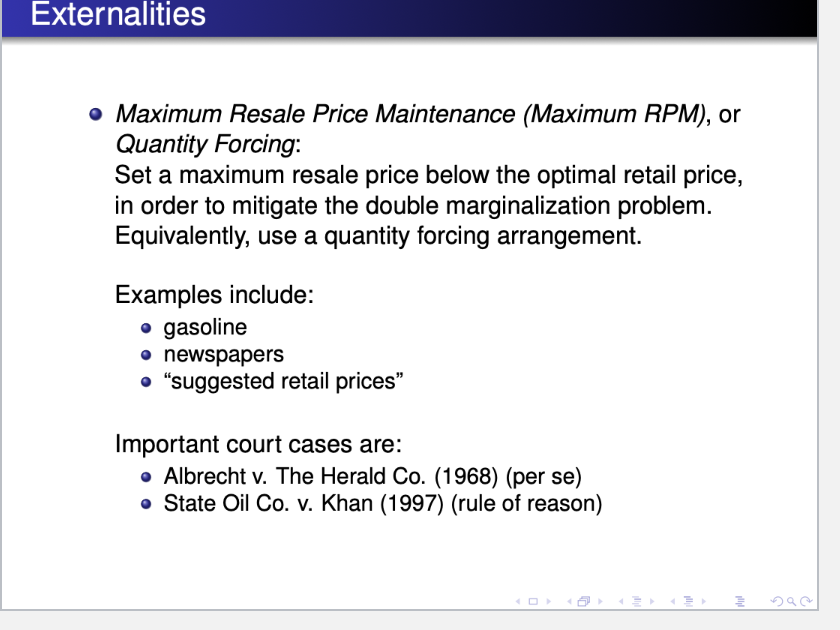

State Oil Co v Khan

Although the rule of Albrecht has been

in effect for some time, the inquiry we

must undertake requires considering

the effect of the antitrust laws upon

vertical distributional restraints in the

American economy today. . . . [T]here

has not been another case since

Albrecht in which this Court has

confronted an unadulterated vertical,

maximum-price-fixing arrangement.

Now that we confront Albrecht directly,

we find its conceptual foundations

gravely weakened.”

ALBRECHT OVERRULED

Leegin Creative Leather Prods v PSKS (2007)

Leegin made Brighton belts and

suggested resale prices. Kay’s Kloset

discounted them and was terminated.

Bottom line, per Justice Kennedy:

“The Court has abandoned the rule of

per se illegality for other vertical

restraints a manufacturer imposes on its

distributors. Respected economic

analysts, furthermore, conclude that

vertical price restraints can have

procompetitive effects. We now hold that

Dr. Miles should be overruled and that

vertical price restraints are to be

judged by the rule of reason.”

RPM can be procompetitive

“[E]conomics literature is replete with

procompetitive justifications for

[RPM]”

RPM “encourages retailers to invest in

. . . services or promotional efforts

that aid the manufacturer’s position as

against rival manufacturers”

RPM can be anticompetitive

It can facilitate cartels by dealers or

manufacturers

It can be abused by manufacturers or

retailers with market power

Because its competitive effect is not

predictable, and often good, the rule

of reason should govern.

“Vertical agreements establishing

minimum resale prices can have either

procompetitive or anticompetitive

effects, depending upon the

circumstances in which they are formed.

And although the empirical evidence on

the topic is limited, it does not suggest

efficient uses of the agreements are

infrequent or hypothetical.”

DR. MILES OVERRULED

Overruled Dr Miles

This will be too complicated for

courts: the result will be

underenforcement.

“One cannot fairly expect judges and

juries in such cases to apply complex

economic criteria without making a

considerable number of mistakes,

which themselves may impose

serious costs.”

Better to stick with the per se rule

(maybe w modification for RPM in

connection with new entry).

Role of economics in antitrust:

“[E]conomics can, and should, inform

antitrust law. But antitrust law cannot,

and should not, precisely replicate

economists’ (sometimes conflicting)

views. That is because law, unlike

economics, is an administrative

system the effects of which

depend upon the content of rules

and precedents only as they are

applied by judges and juries in

courts and by lawyers advising their

clients.”

Exclusivity

Exclusivity might be the paradigm

vertical interbrand restraint: extracting

an agreement not to deal with

competitors from trading partners.

This can suppress or eliminate

competition under certain

circumstances.

NOTE: softer variations are possible:

agreements that encourage exclusivity

without mandating it (e.g., price

differentials).

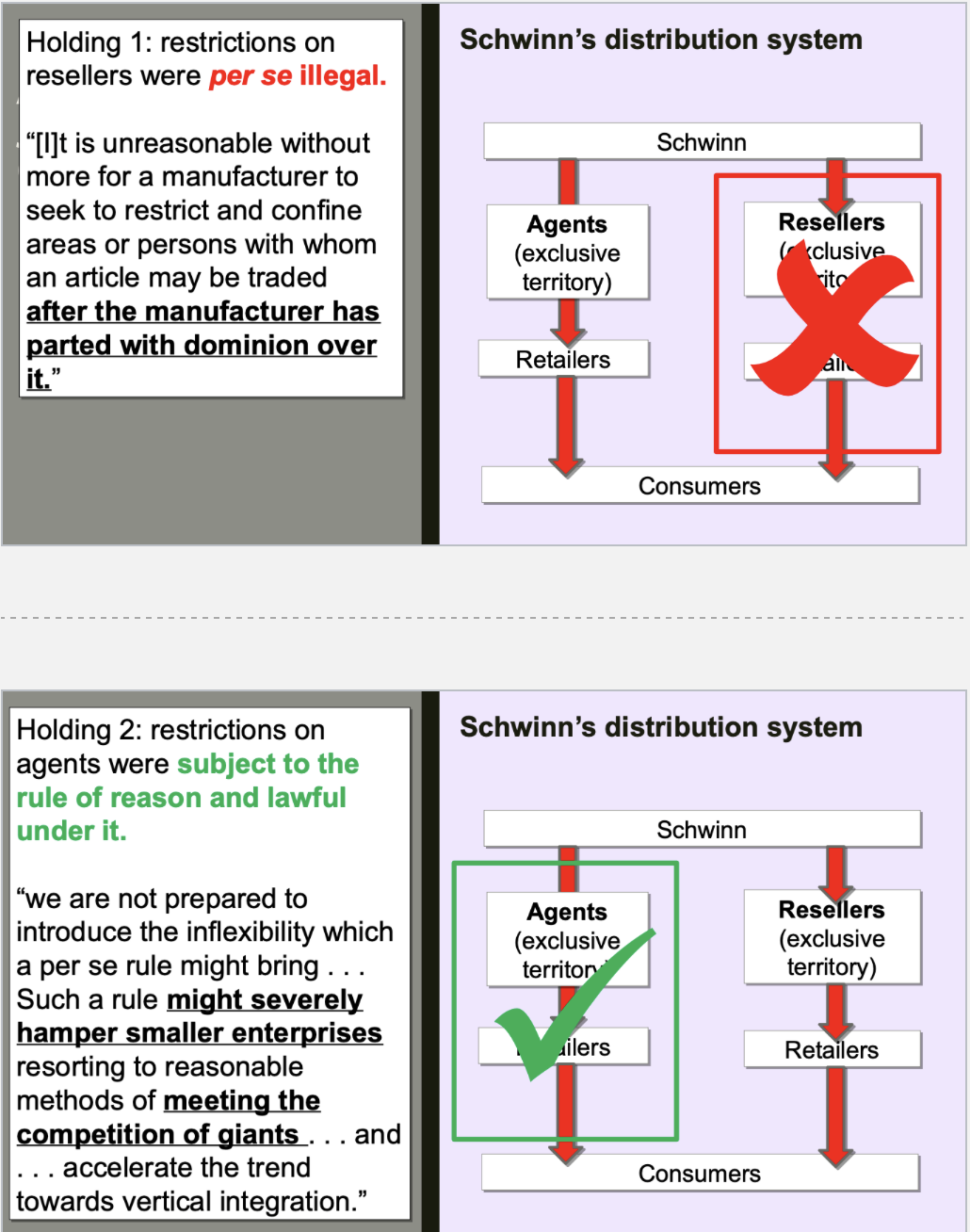

Core concern is “foreclosure.”

Cutting off, or limiting, rivals’ access to

competitively important inputs (input

foreclosure), or...

Core concern is “foreclosure.”

Cutting off, or limiting, rivals’ access to

competitively important distribution

(distribution foreclosure)

But not always bad or illegal.

1. Exclusivity is pretty common.

2. Trading partners often make

significant investments in each

other, and may not make

investments if competitors can

benefit from them.

3. And a party may highly value

security of supply from the

knowledge that the trading partner is

not also splitting its attention with

others.

But not always bad or illegal.

1. Examples:

a) A chipmaker might partner exclusively

with a device OEM to develop a new

chip that makes new features possible.

b) A fast food franchisee (always!) agrees

to carry only one brand of fast food.

c) A brand might pay for celebrity

endorsement only if that celebrity will

not also promote a competitor.

Tampa Electric v Nashville Coal (1961)

The Seminal

Case: Tampa

Electric

1. Tampa Electric operated power

plants. It agreed to buy all its

requirements of coal from Nashville

Coal Co.

2. Nashville was one of 700 coal

suppliers in the area, and the

contract represented ~1% of coal

production available for use in FL.

3. Tampa then spent millions of dollars

preparing to use Nashville’s coal.

4. Shortly before delivery date,

Nashville said: the contract’s an

antitrust violation, we’re not

performing, good luck with

everything, k thanks bye

The Court applied s 3 Clayton Act

(broadly equivalent to s 1 Sherman

Act), and set out what is now a

critical principle:

“In practical application, [exclusive

dealing] does not violate the section

unless the court believes it probable

that performance of the contract will

foreclose competition in a

substantial share of the line of

commerce affected.”= SUBSTANTIAL

FORECLOSURE TEST

= SUBSTANTIAL

FORECLOSURE TEST

PRELIMINARY STEP

“First, the line of commerce, i.e., the

type of goods, wares, or merchandise,

etc., involved must be determined,

where it is in controversy, on the basis

of the facts peculiar to the case. . .

[And] the area of effective competition

in the known line of commerce must be

charted by careful selection of the

market area in which the seller

operates, and to which the purchaser

can practicably turn for supplies”

= MARKET DEFINITION

SUBSTANTIAL FORECLOSURE

Exclusivity must foreclose “a substantial

share” of the market.

“[O]pportunities for other traders” must

be “significantly limited.”

Court must “weigh the probable effect of

the contract on the relevant area of

effective competition, taking into

account the relative strength of the

parties, the proportionate volume of

commerce involved in relation to the

total volume of commerce in the

relevant market area, and the probable

immediate and future effects which pre-

emption of that share of the market

might have on . . . competition[.]”

In other words: in light of all the

facts, is this really likely to harm

competitive conditions?

Note: The earlier Standard

Stations case (1949) had inferred

sufficient harm from exclusive deals

covering just 16% of distribution

capacity (in that case, service

stations for retailing gas). The

Standard Stations Court did not

undertake the kind of careful

analysis signaled in Tampa: so this

raised the bar for plaintiffs.

PPLICATION

“[I]t clearly appears that the

proportionate volume of the total

relevant coal product as to which the

challenged contract pre-empted

competition, less than 1%, is,

conservatively speaking, quite

insubstantial”

What are we really measuring here?

1. Key idea is that not ALL restrictions

of access to inputs or distribution

harm competition.

2. Restriction of access must usually

be such that it raises rivals’ costs

(e.g., insufficient amount, or

insufficient quality, of inputs /

distribution, or facilitating

coordination); AND

3. This impact must be capable of

affecting competitive conditions.

Microsoft (2001) suggested 40-50%

foreclosure share in a Section 1 case.

Roland Machinery v Dresser Industries

. Roland distributed machinery from Dresser.

2. Roland then agreed to distribute for Komatsu

too.

3. Dresser exercised its right to terminate

Roland without cause.

4. Roland sued under Section 3.

5. Issue: could Roland get a preliminary

injunction to prevent Dresser cutting it

off during the litigation?Q: What was the foreclosure

concern here?

A: Distribution foreclosure

of Komatsu: competitive

harm among manufacturers.

Q: What was the foreclosure

concern here?

A: Distribution foreclosure

of Komatsu: competitive

harm among manufacturers.

Court below held:

1. There was an implicit exclusive

agreement between Dresser and Roland.

2. Dresser accounted for 16-17% of

construction equipment in central Ilinois -- all

Dresser sales go through Roland.

3. Komatsu could only enter by persuading a

dealer to carry Komatsu as a second line.

4. Roland might go out of business if cut off.

Granted the injunction; Dresser appealed.

Writing for the Seventh Circuit, Judge Posner

was not happy. Held:

1. No suggestion of agreement.

2. Little reason to think it was anticompetitive.

Preliminary injunction should be

vacated.

The Poze Sez No

FIRST: No agreement, just unilateral action.

“The fact that Dresser was hostile to dealers

who would not live and die by its product . . .

and acted on its hostility by canceling a

dealer who did the thing to which it was hostile,

does not establish an agreement[.]”

“Assume that Dresser made clear to Roland

and its other dealers that it wanted only

exclusive dealers[.] . . . The mere

announcement of such a policy, and the

carrying out of it by canceling Roland or any

other noncomplying dealer, would not

establish an agreement.”

ECOND: Doesn’t seem unlawful.

Modern law does not judge exclusivity under

the “simple and strict” test of earlier cases.

• “Although the Supreme Court has not

decided an exclusive-dealing case in many

years, it now appears most unlikely that

such agreements, whether challenged

under section 3 of the Clayton Act or

section 1 of the Sherman Act, will be

judged by the simple and strict test

of Standard Stations.”

SECOND: Doesn’t seem unlawful.

“The exclusion of one or even several

competitors, for a short time or even a long

time, is not ipso facto unreasonable. . . . a

plaintiff must prove two things to show that an

exclusive-dealing agreement is unreasonable.

First, he must prove that it is likely to keep at

least one significant competitor of the

defendant from doing business in a relevant

market. If there is no exclusion of a significant

competitor, the agreement cannot possibly

harm competition. Second, he must prove

that the probable . . . effect of the exclusion

will be to raise prices above (and therefore

reduce output below) the competitive level,

or otherwise injure competition[

“Komatsu cannot be kept out of the central

Illinois market even if every manufacturer of

construction equipment prefers exclusive

dealers . . . . Komatsu is the second largest

manufacturer of construction equipment in

the world. . . . Since dealership agreements in

this industry are terminable by either party on

short notice, Komatsu, to obtain its own

exclusive dealer in some area, has only to

offer a better deal to some other

manufacturer's dealer in the area.”

= Komatsu can compete FOR exclusive

relationships

THIRD: Exclusivity has benefits!

May lead to better promotional efforts and

services.

• “If . . . exclusive dealing leads dealers to

promote each manufacturer’s brand more

vigorously . . . the quality-adjusted price to

the consumer . . . ma

May align incentives so dealers have skin in

the game of promoting the manufacturer’s

brand.

• “A dealer who expresses his willingness to

carry only one manufacturer’s brand of a

particular product . . . doesn’t have divided

loyalties. . . . [I]f Roland failed to promote

Dresser vigorously, it would have Komatsu

to fall back on—but Dresser might suffer a

drastic decline in the central Illinois

market[.]”

y be lower with

exclusive dealing

THIRD: Exclusivity has benefits!

May help protect against dealer free riding.

• “Exclusive dealing may also enable a

manufacturer to prevent dealers from taking

a free ride on his efforts (for example, efforts

in the form of national advertising) to

promote his brand. The dealer who carried

competing brands as well might switch

customers to a lower-priced substitute on

which he got a higher margin.”

than without[.]”

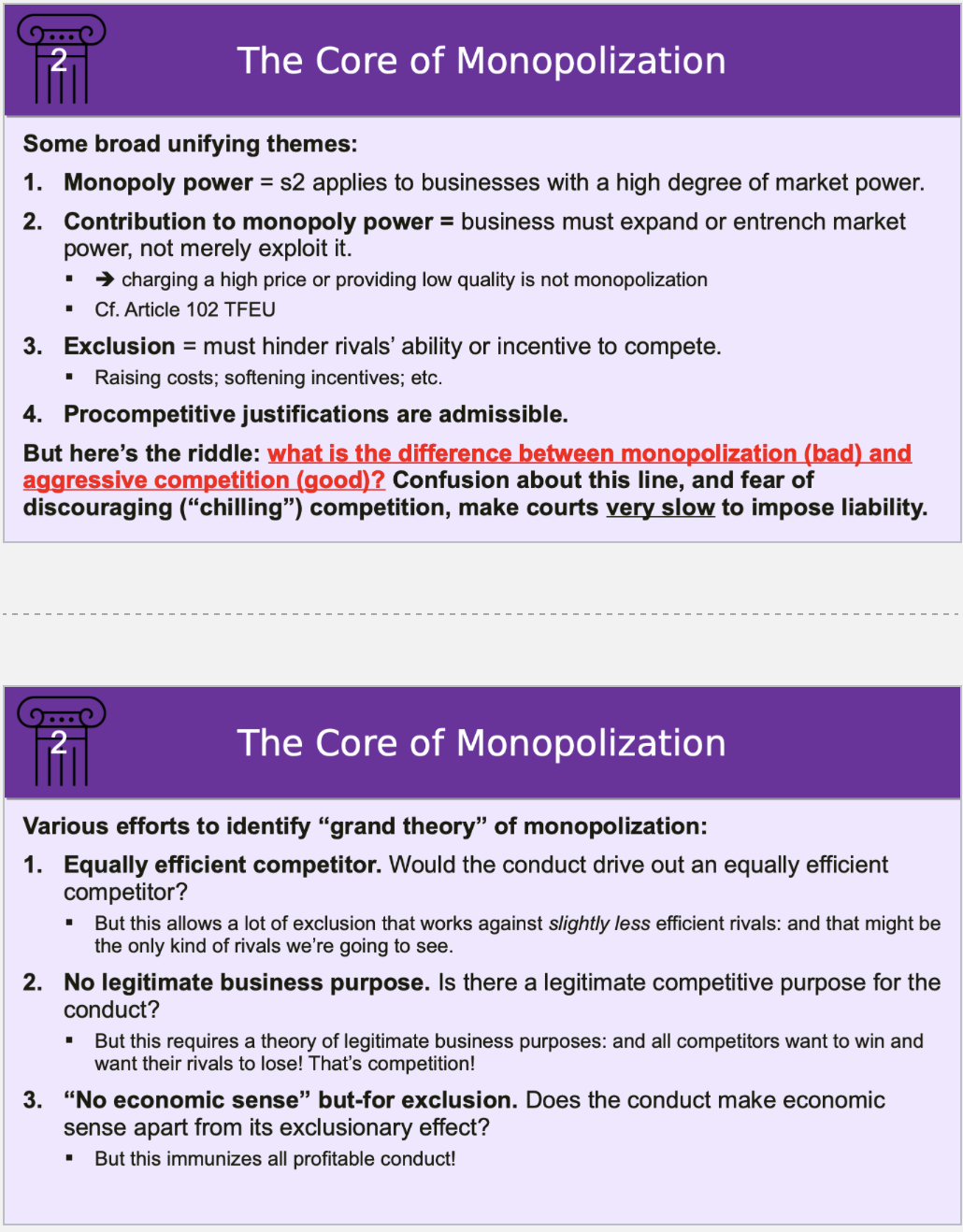

Section 1 Sherman vs Section 3 Clayton

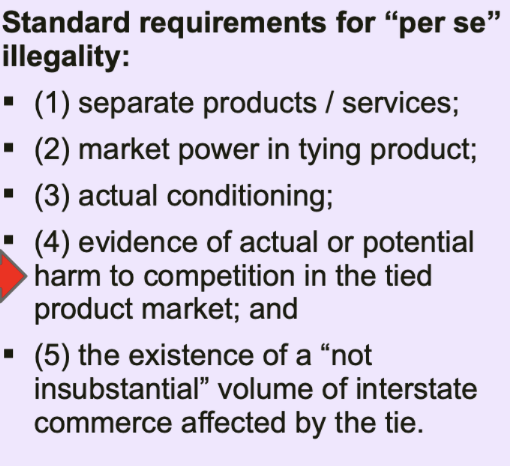

Tying

Tying is the practice of selling one

thing (the TYING product/service)

only condition that the purchaser

buy something else from you as well

(the TIED product/service)

Core competitive concern: use of

market power to generate customer

foreclosure in a second market.

1. A seller might use market power in

the tying product / service to make

customers purchase the tied product

/ service.

2. Doing so might deprive rivals of

scale efficiencies and make them

less able to compete in the tied

market.

3. The result may be more market

power in the tied market

But two important qualifications.

1. First: there are often very good

reasons to sell things together.

a. No-one sells infinitely subdivided

products. (Is it tying to sell a hot dog?)

b. And there are often huge efficiencies in

doing so.

2. Second: under some

circumstances you cannot create

market power with a tie. (The

“Single Monopoly Profit

Theorem.”)

Single Monopoly Profit

You normally cannot create

additional profit by tying to a strict

complement that is consumed in

fixed proportions. Implication: if you

are finding it profitable to do so, it’s

probably because of efficiencies.

1. Example: if demand is only for “1

cup + 1 saucer” pairs, and if I am

already a cup monopolist, I can

make no more money by tying cups

to saucers than I could make by

charging for my cups alone.

Pretty limited zone of application.

But the SMP does not apply:

1. If complements are used in

variable proportions. Shifting

margin to the one used more heavily

by inelastic customers is a form of

price discrimination: extracts more

profit from intensive users.

2. If complements are not strict. If

there is demand for one good

without the other, depriving rivals of

scale might augment market power.

3. If one market is a path to the

other. Requiring “two level entry” or

eliminating an entry path may

entrench tying market power.

Where can you challenge tying

Requirements for per se tying

Jefferson Parish Hospital District 2 (1984)

East Jefferson hospital: if we treat

you, you have to get anesthesia

services from Roux and Associates.

Challenged as a § 1 tie.

Justice Stevens for the Court:

It is far too late in the history of

our antitrust jurisprudence to

question the proposition that

certain tying arrangements pose

an unacceptable risk of stifling

competition and therefore are

unreasonable “per se.”

Not the clearest decision

Defended a limited per se rule.

Test:

1. Separate products (“demand for .

. . anesthesiological services

separate from hospital

services”).

2. Tying market power (“control

over the tying product”).

3. Actual conditioning (“forcing”).

4. Evidence of harm to competition

(“substantial potential for impact

on competition”).

5. Volume of interstate commerce

(“substantial volume”).

Jefferson Parish:

majority opinion

O’Connor C’mon, enough already! “The time

has come to abandon the ‘per se’

label and refocus . . . on the adverse

economic effects, and the potential

economic benefits, [of a tie].”

“First, the seller must have power in the

tying product market.”

“Second, there must be a substantial

threat that the tying seller will acquire

market power in the tied-product

market.”

“Third, there must be a coherent

economic basis for treating the tying

and tied products as distinct.”

Fourth, conIn this case, no separate products.

1. Demand is always for a hospital-

services-plus-anesthesia package,

never anesthesia alone.

2. The “tying . . . cannot increase the

seller’s already absolute power over

the volume of production of the tied

product.”

3. And procompetitive benefits!

a. More efficient logistics.

b. Better quality monitoring.

c. Allows hospital to ensure

compatibility w standards.

d. Exclusivity is common in

hospitals.How is this different from

Justice Stevens’

separateness test?

r “economic benefits.

Most favored nation

An MFN (“most favored nation”)

agreement entitles the beneficiary to

treatment at least as favorable as

others are getting.

1. Example: MFN pricing means I, a

beneficiary buyer, get the best price

at which you sell to anyone.

2. Sounds great, right? And it can be.

3. Can help push prices down in a

world of imperfect information:

makes it easier to figure out what

low prices a supplier can really

offer.

And can help buyers fight efforts at

price discrimination!

But the dark side of an MFN is that it is

also a promise not to offer other trading

partners a better deal.

A business with market power might

use an MFN to prevent a trading

partner giving deals to encourage

competitive entry.Entrant?

Entrant?Key Input

Key InputMonopolist

Monopolist

But the dark side of an MFN is that it is

also a promise not to offer other trading

partners a better deal.

Participants in a cartel or tacit

collusion might use an MFN to

commit not to discount.

How do MFNs penalize discounting?

But the dark side of an MFN is that it is

also a promise not to offer other trading

partners a better deal.

An MFN-plus is a promise to get

better treatment by some margin.

This is a surcharge on dealing with

rivals and VERY suspicious.

E.g., “You commit to give me a price

at least 10% better than any rival is

getting.”

Section 2 of the Sherman Act

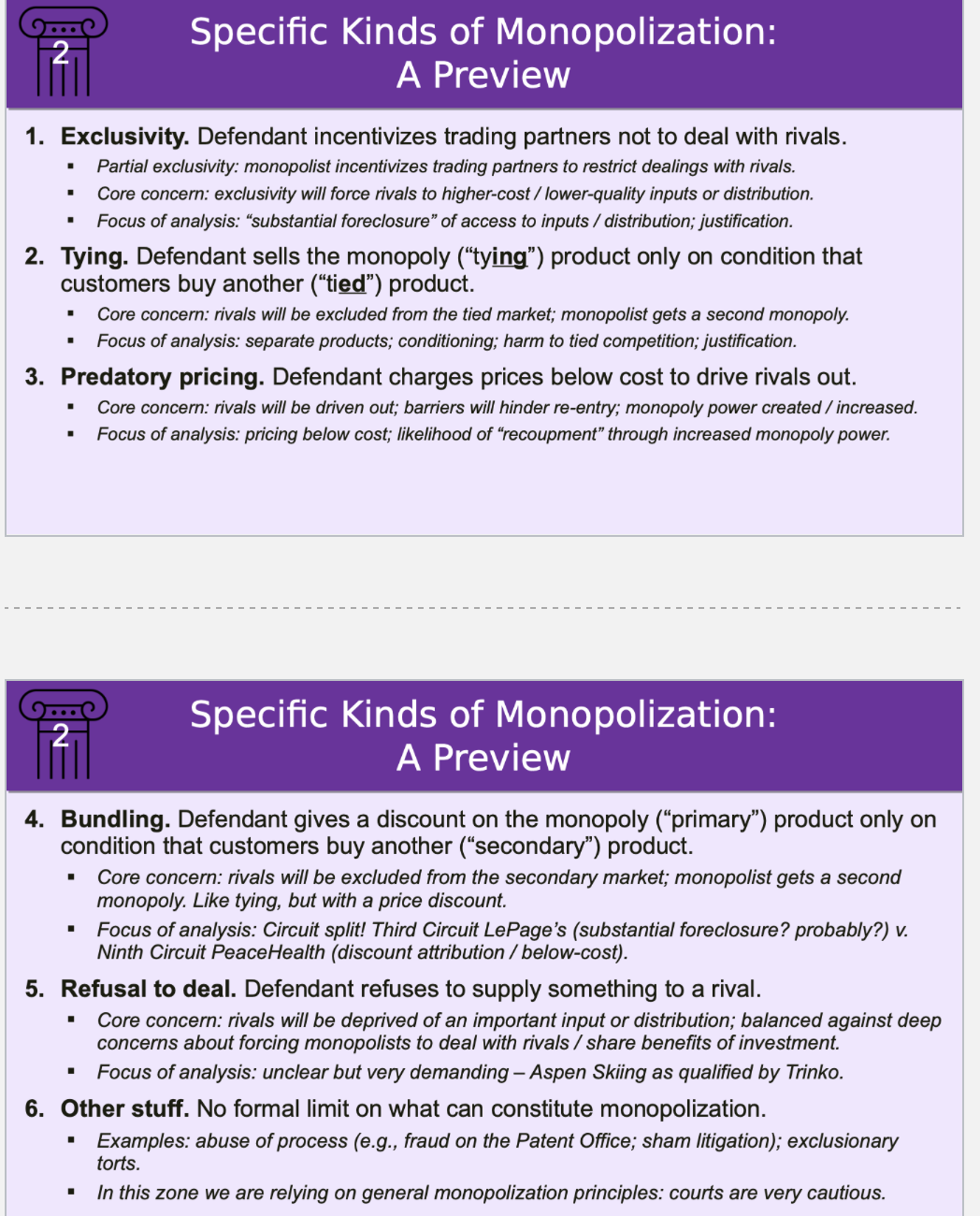

Specific kinds of Monopolization

Exclusivity

Tying

Predatory Pricing

Bundling

Refusal to deal

Others

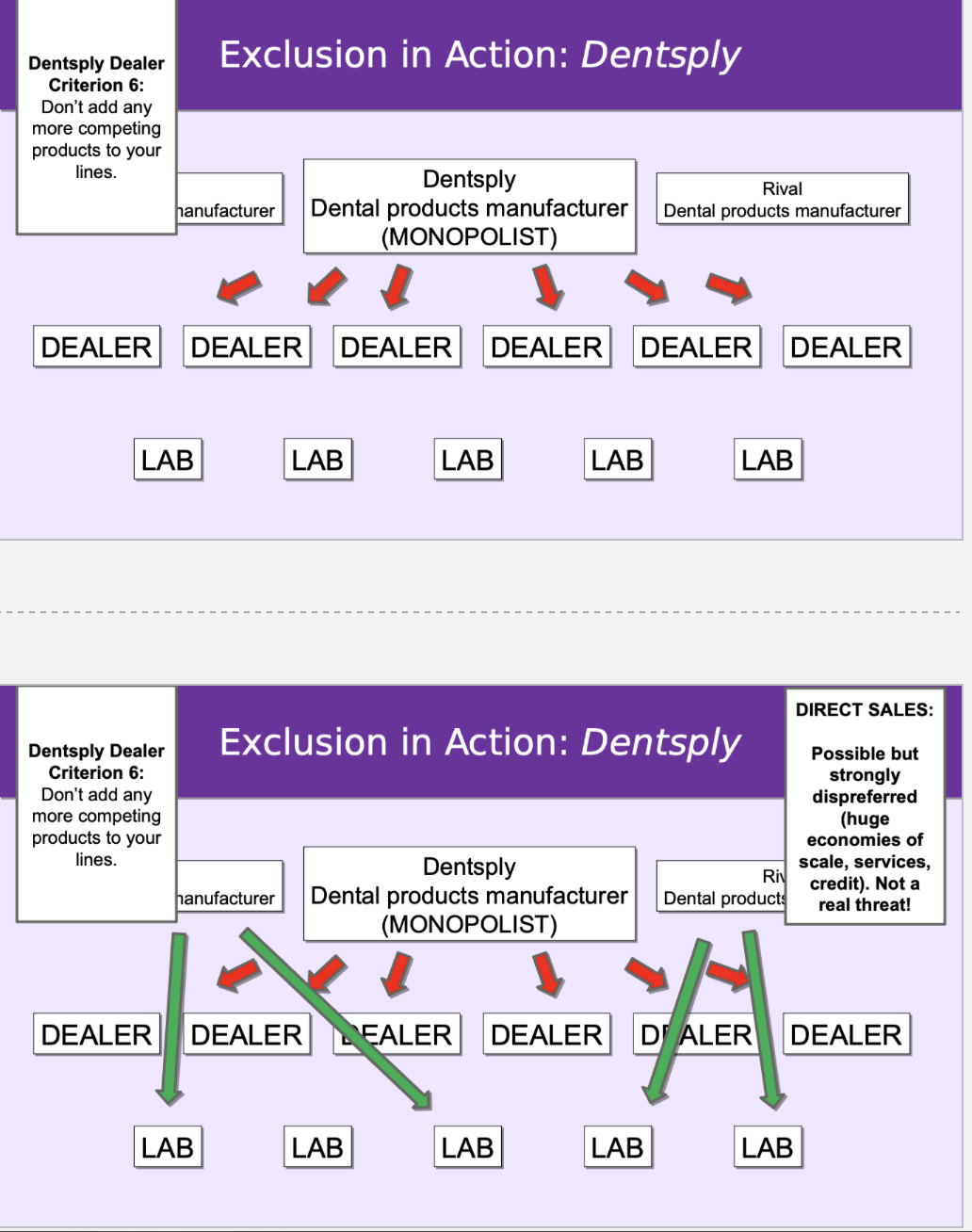

Dentsply

Exclusion

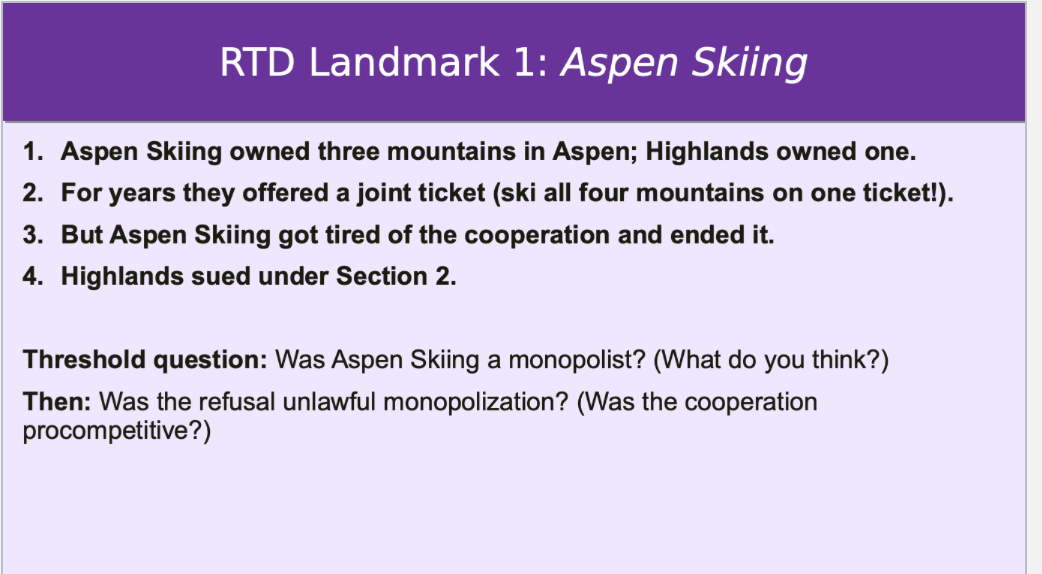

Aspen Skiing v Aspen Highlands

Refusal to deal

Tests: unnecessarily restrictive. Attempting to exclude rivals on some basis other than efficiency

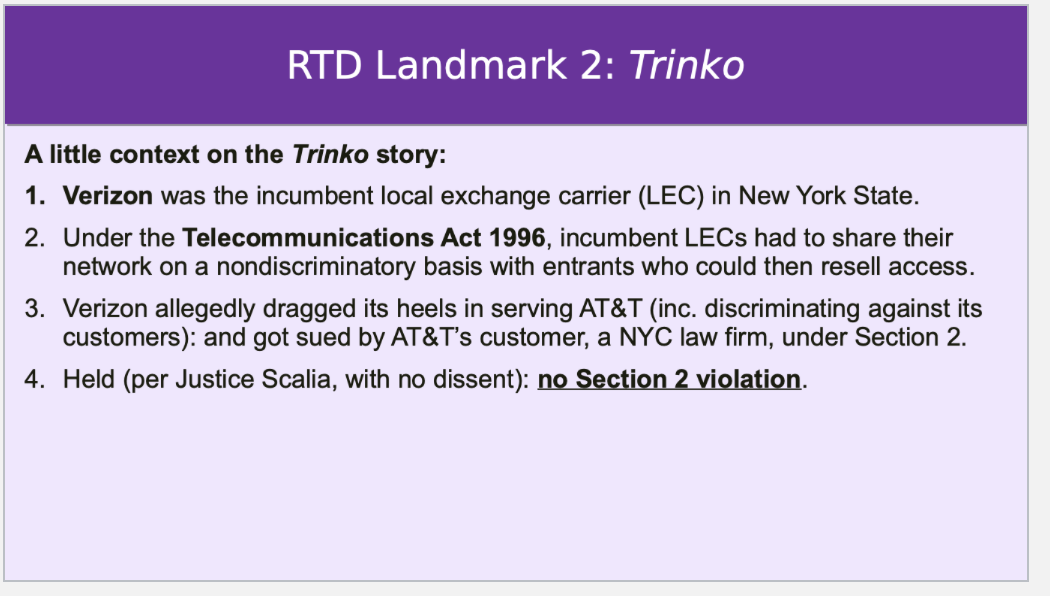

Trinko

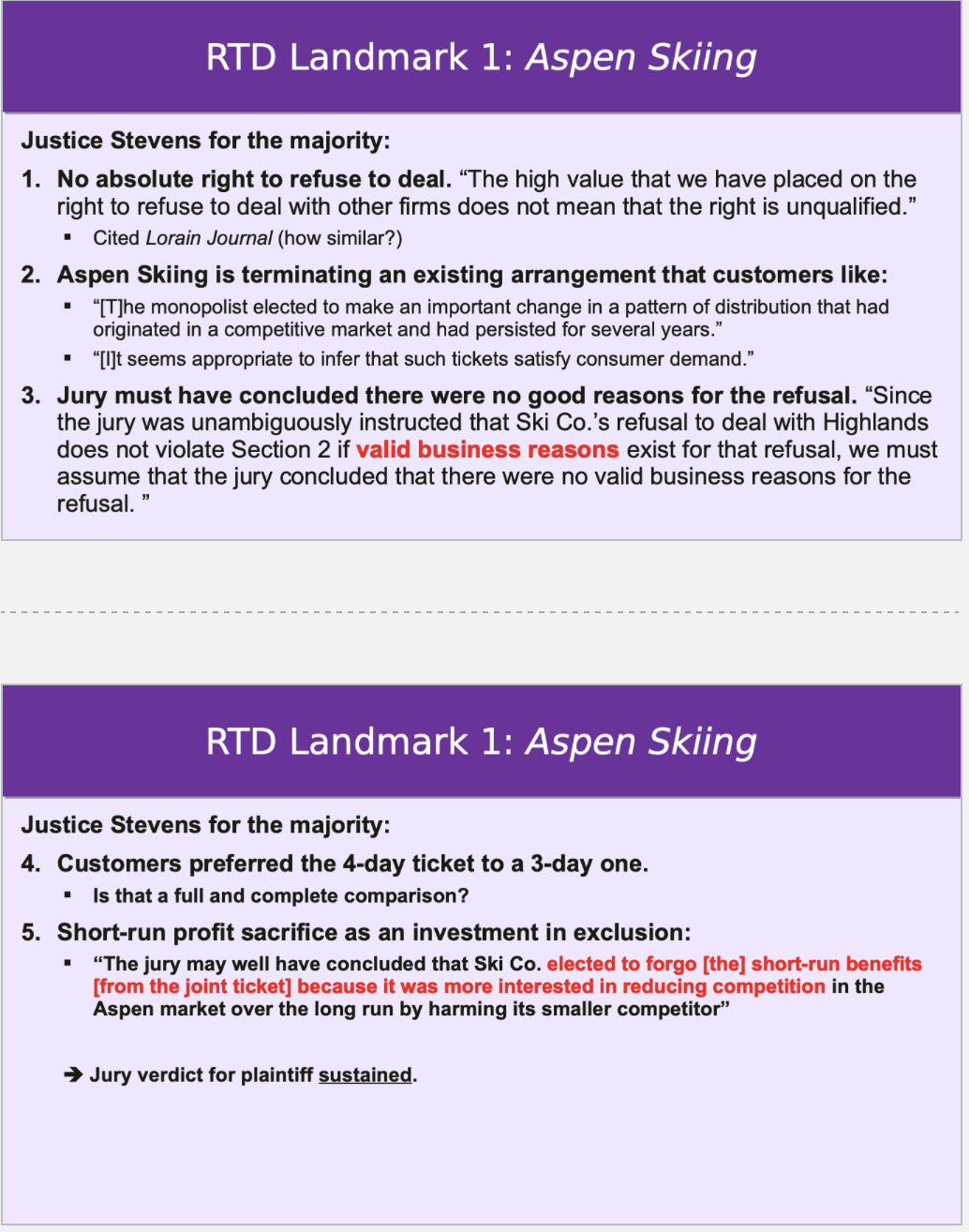

Held: Aspen Skiing is “at or near the outer boundary” of s2 & doesn’t apply here.

1. The Aspen case involved profit sacrifice through termination of a previous

profitable course of dealing. “The unilateral termination of a voluntary (and thus

presumably profitable) course of dealing suggested a willingness to forsake short-

term profits to achieve an anticompetitive end.”

2. Aspen refused to share even if paid retail price. “Similarly, the defendant’s

unwillingness to renew the ticket even if compensated at retail price revealed a

distinctly anticompetitive bent.”

3. Aspen was already supplying the product. Here, Verizon wouldn’t be supplying

unbundled access at all if it weren’t for the Telecommunication Act 1996.

4. Access is federally regulated here! Reduces benefits of antitrust intervention.

Trinko is an iconic and influential statement of caution in Section 2 law.

1. Error costs of wrongful liability. “Mistaken inferences and the resulting false

condemnations are especially costly, because they chill the very conduct the

antitrust laws are designed to protect. The cost of false positives counsels against

an undue expansion of § 2 liability.”

2. Every dispute could turn into antitrust litigation. Too much intervention would

“distort investment and lead to a new layer of interminable litigation, atop the

variety of litigation routes already available to and actively pursued by [rivals].”

3. Micromanaging prices and terms could be too much for a court. “No court

should impose a duty to deal that it cannot explain or adequately and reasonably

supervise. The problem should be deemed irremediable . . . [when it requires] the

court to assume the day-to-day controls characteristic of a regulatory agency

Bottom line:

1. Trinko symbolizes caution about Section 2 (esp. forced sharing).

2. Aspen Skiing now widely regarded as confined to its facts: termination of a

previous voluntary and profitable course of dealing, in something the

defendant voluntarily supplies, for purely anticompetitive purposes.

3. But:

a. Why punish termination of existing dealings more strictly than new refusals?

b. Is it “anticompetitive” not to want to subsidize your rival? Is it “exclusion” at all?

c. The Trinko Court at least considered whether to expand s2 beyond Aspen: was

the federal regulation the reason it didn’t do so?

d. Why is a “profit sacrifice” suspicious?

Some monopolization is short-run profitable; some profit sacrifice is procompetiti

Monopoly is not unlawful: in

fact it serves a useful function!

“The opportunity to charge

monopoly prices at least for a

short period is what attracts

‘business acumen’ in the first

place; it induces risk taking that

produces innovation and

growth.”