CHEM 20A Final

1/152

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

153 Terms

Extensive Property

a property that depends on the size of the substance

ex: volume, mass

Intensive Property

a property that is independent of the size of the substance

ex: temp, density

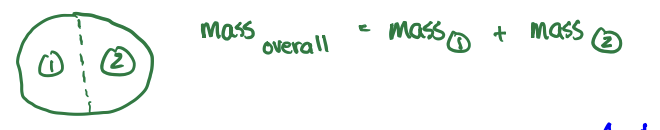

Law of Conservation of Mass (Lavoisier)

Experiment: decomposition of mercury oxide

Significance: not creating or destroying building blocks, but rearranging in chemical reactions; you combine them in different ways and it comes out with a different property

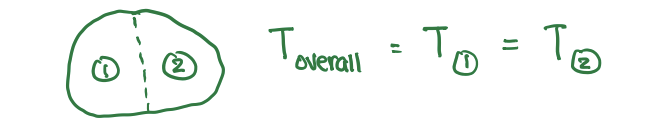

Law of Definite Proportion (Berthollet vs. Proust)

Experiment: Lavoisier’s experiment many times and measure [mass of gas/mass of mercury oxide]

Berthollet said % mass of gas is not fixed; it can vary over a range

Proust said, in a given chemical compound, the proportions by mass of elements that compose it are fixed; variations due to error or impurities

Significance: building blocks combine in specific ratios (ONE COMPOUND) to form different compounds

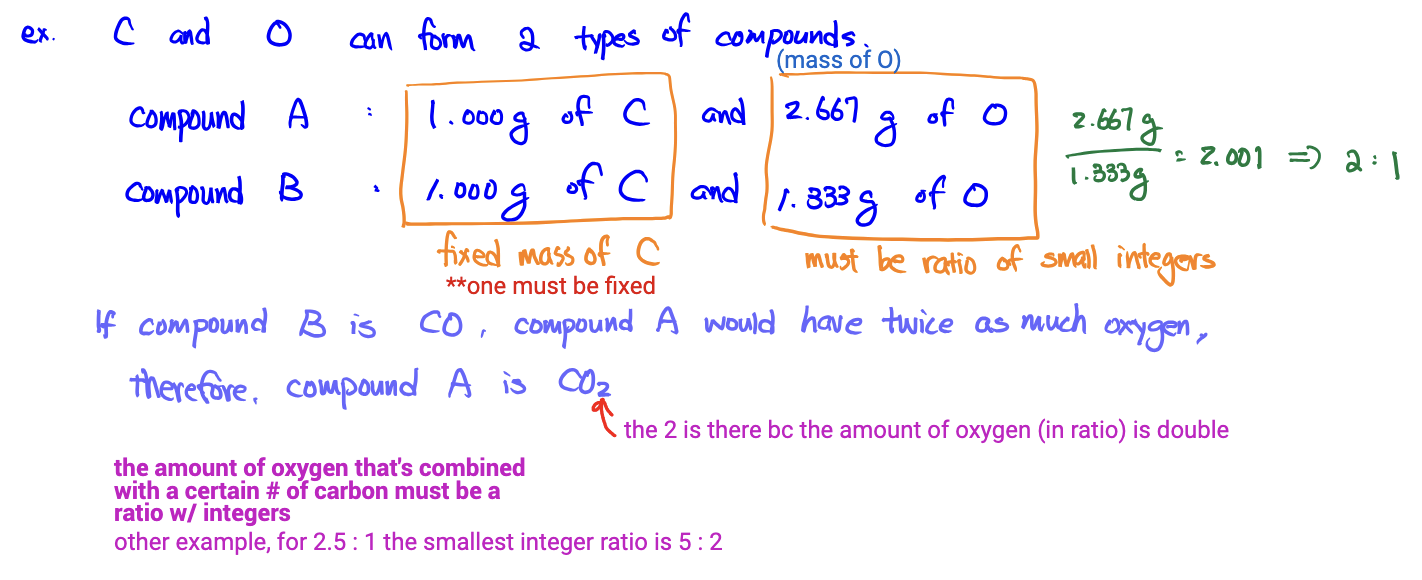

Law of Multiple Proportions

When two elements form a multiple compounds (DIFFERENT COMPOUNDS WITH SAME ELEMENTS), the masses of one element that combine with a fixed mass (1g) of the other element are in the ratio of small integers to each other.

*note: when solving, one element should be fixed

Dalton’s Atomic Theory of Matter (1808)

Significance: summarized the conservation of mass and definite proportion; coined “atom”

The two main things he got wrong:

He said that atoms are indestructible/indivisible

Can be further broken down to electrons, protons, and neutrons

He assumed the identity of the atom is determined by the mass

Not true because of isotopes

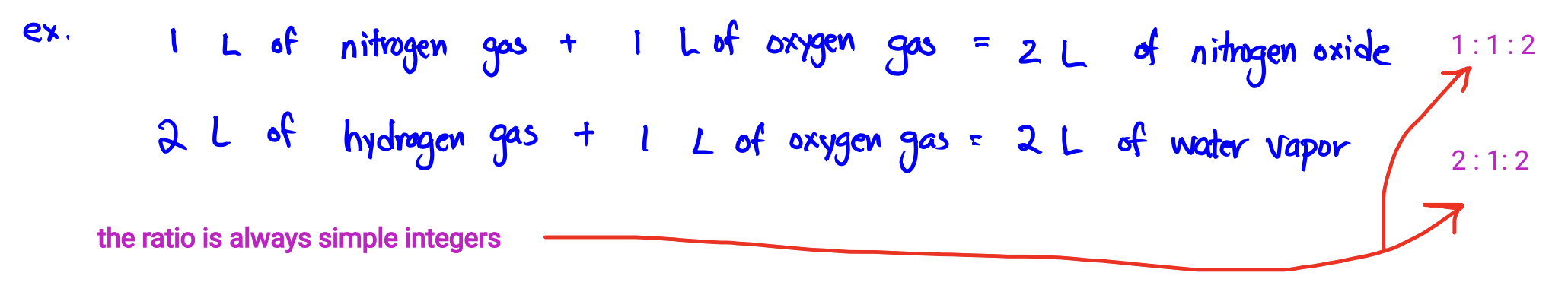

Law of Combining Volumes (Gay-Lussac)

The ratio of the volumes of any pair of gases in a gas phase chemical reaction (at the same temperature and pressure) is the ratio of simple integers.

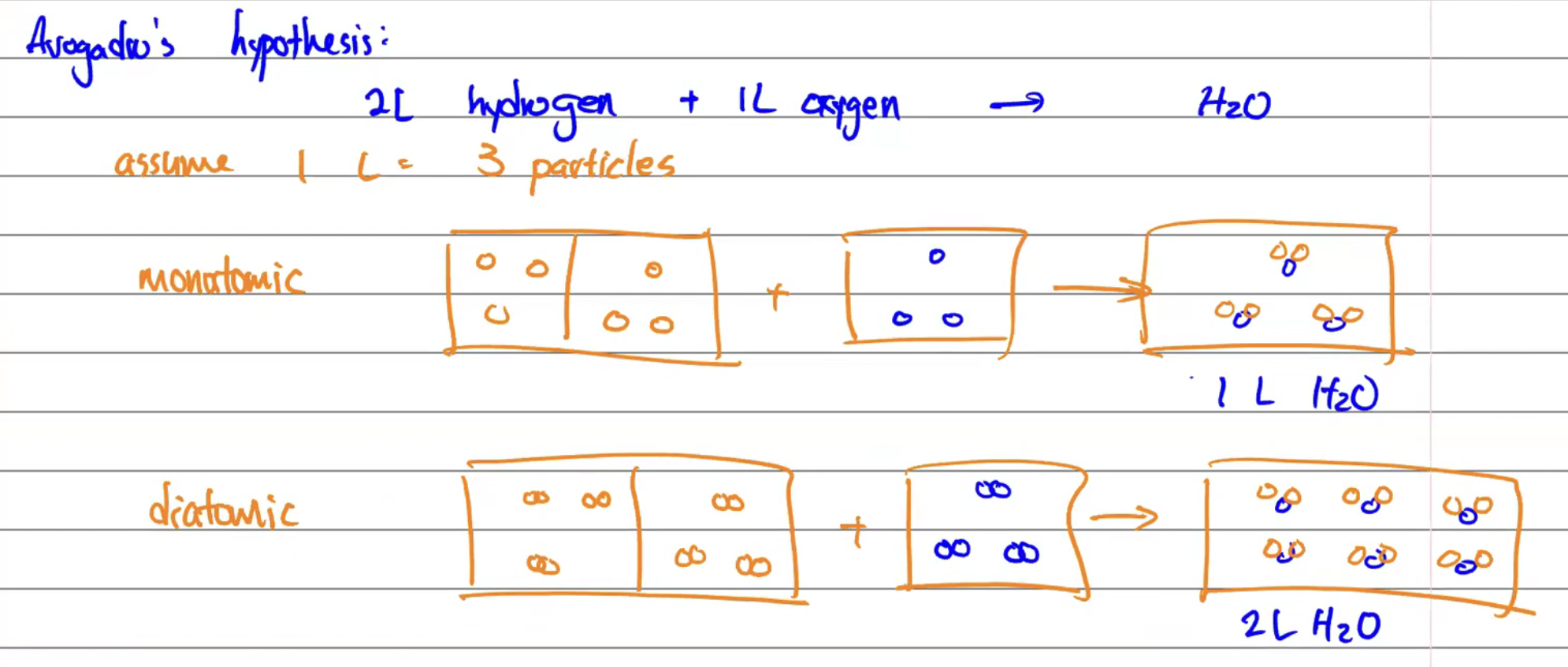

Avogadro’s Hypothesis

Equal volumes of different gases at the same temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of particles.

Experiment: 1 L of N + 1 L of O = 2 L of NO

The assumption would be that it would = 1 L NO, but since it’s 2 L NO, the hypothesis suggests N and O are diatomic molecules

Mole

Conceptualization: a unit for an amount of a substance, kinda like how a pair = 2 and a dozen = 12

Formula: 1 mol of atoms = 6.0221 × 10^23 atoms

Avogadro’s Number: 6.0221 × 10^23

If I divide mass (g) by the molar mass, I get mol of molecules

Avogadro’s Number

6.0221 × 10^23 atoms

Relationship between average atomic mass and mole

avg. atomic mass in amu = 1 mol of [element] atoms

![<p>avg. atomic mass in amu = 1 mol of [element] atoms</p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/812f5fbf-ebae-437c-9f2f-3f477bdfd2ba.png)

Molar Mass of an Element

molar mass of an element = mass of one mole of its atoms (atomic mass)

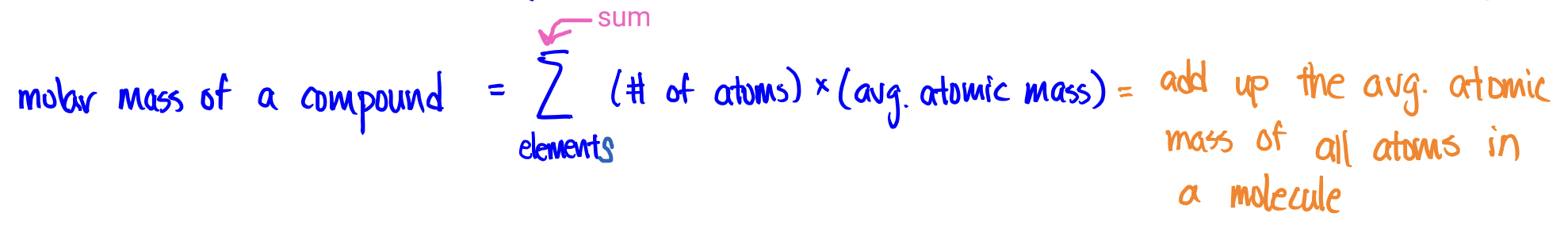

Molecular Weight (molar mass of a compound)

molar mass of a compound = mass of 1 mole of its molecules

To find the molar mass of a compound, add up the avg. atomic mass of all the atoms in a molecule

Molecular Formula

the actual number of atoms in a molecule

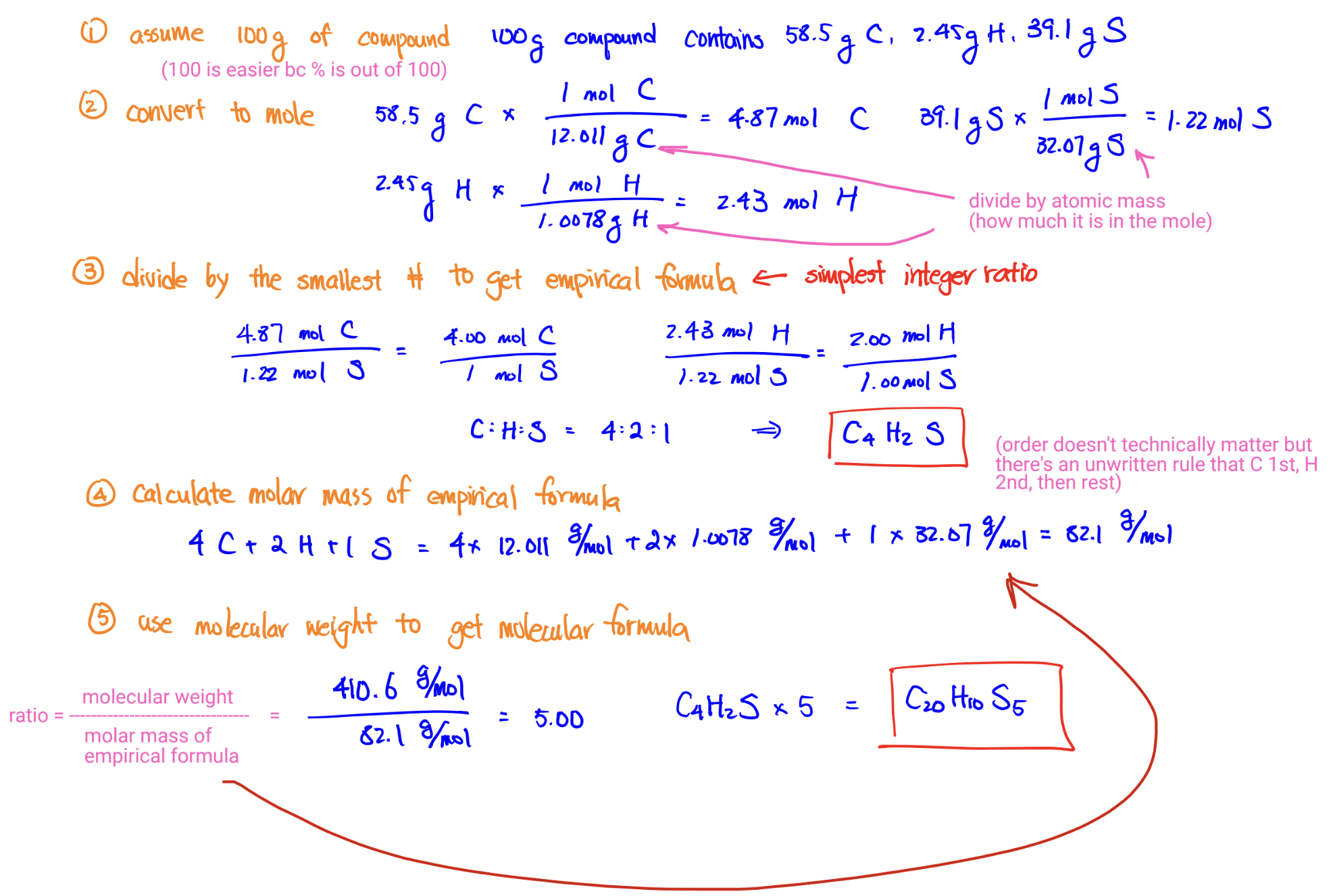

Empirical Formula

the simplest whole number ratio of atoms

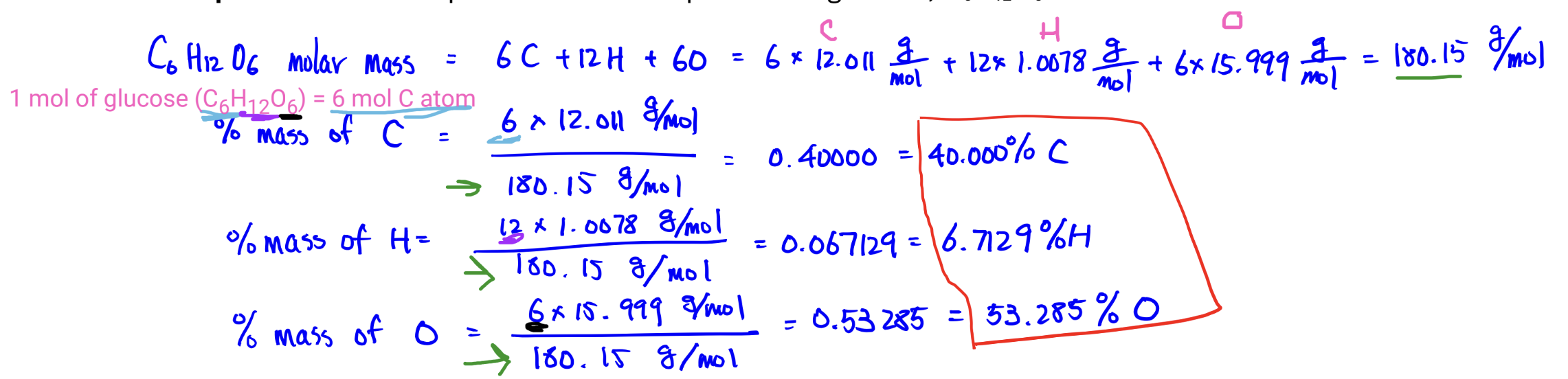

Percent Mass Composition

(mass of element in a compound)/(mass of a molecule)

Empirical Formula from Percent Mass Composition

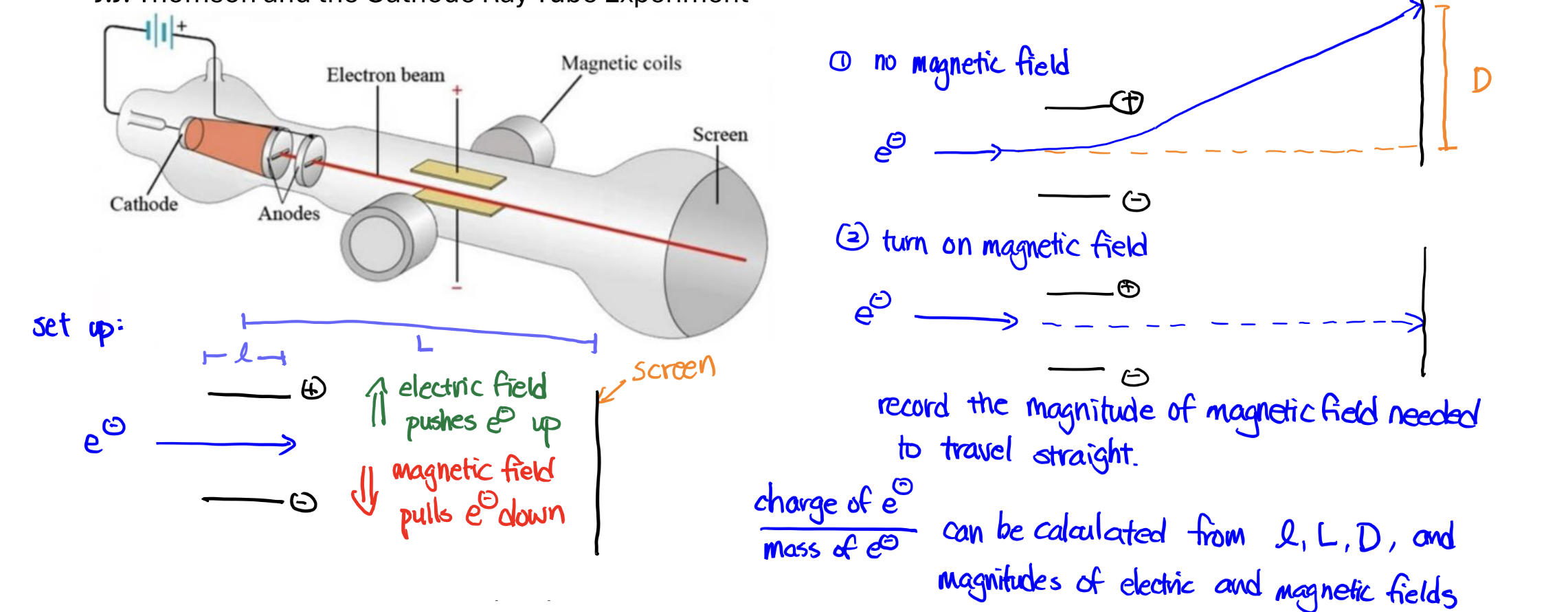

Cathode Ray Tube Experiment

Experiment: shoot a ray of electrons through a tube with an electric and magnetic field affecting the ray; electric directs the path, and changing the magnetic field can make it go straight (the light can curve without magnetic field, the distance = D)

Significance: charge-to-mass ratio

Oil Drop Experiment

Experiment: oil drop given a charge, and when it falls (gravity pulls it down), the negatively charged drop is suspended in air by changing the magnitude of the electric field

Significance: charge of e- (it’s 1.6 × 10^-19)

(charge can be calculated from the mass of the oil drop and the magnitude of the electric field needed to balance g-force)

If there are multiple e-s, the difference in charges has to be an integer multiple of the charge of the e-, and the smallest difference is the charge of the e-

Gold Foil Experiment

Before, the Plum-Pudding Model said an atom was made up of a positively charged “pudding” with e-s evenly spread out because they repel.

However, when a sheet of gold was shot with positively charged particles, there were some that were deflected/bounced back.

This suggested that atoms have a core (the nucleus) that’s dense and positively charged

Significance: discovery of a nucleus

Mass Spectrometry

A magnetic field bends the path of e-s in a beam, and it was seen that some atoms of the same element were bent differently. Lighter atoms bend more, and heavier atoms bend less.

Significance: atoms of the same element CAN have different masses; discovery of isotopes

Calculation of Average Atomic Mass

SUM of all isotopes’ [(mass x abundance)]

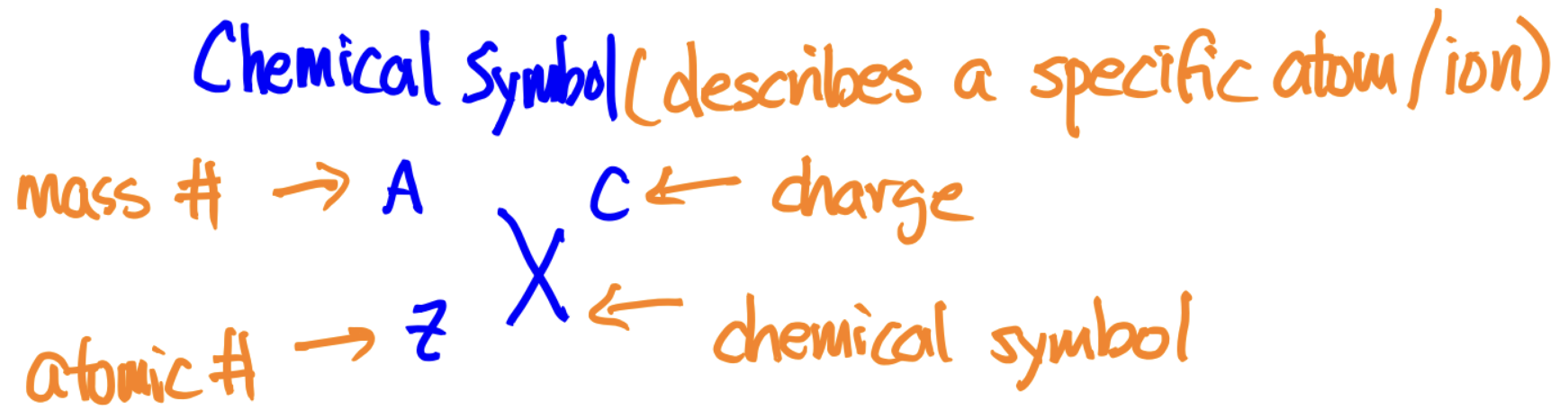

The mass of each is denoted by the superscript before the chemical symbol (the superscript after is the charge)

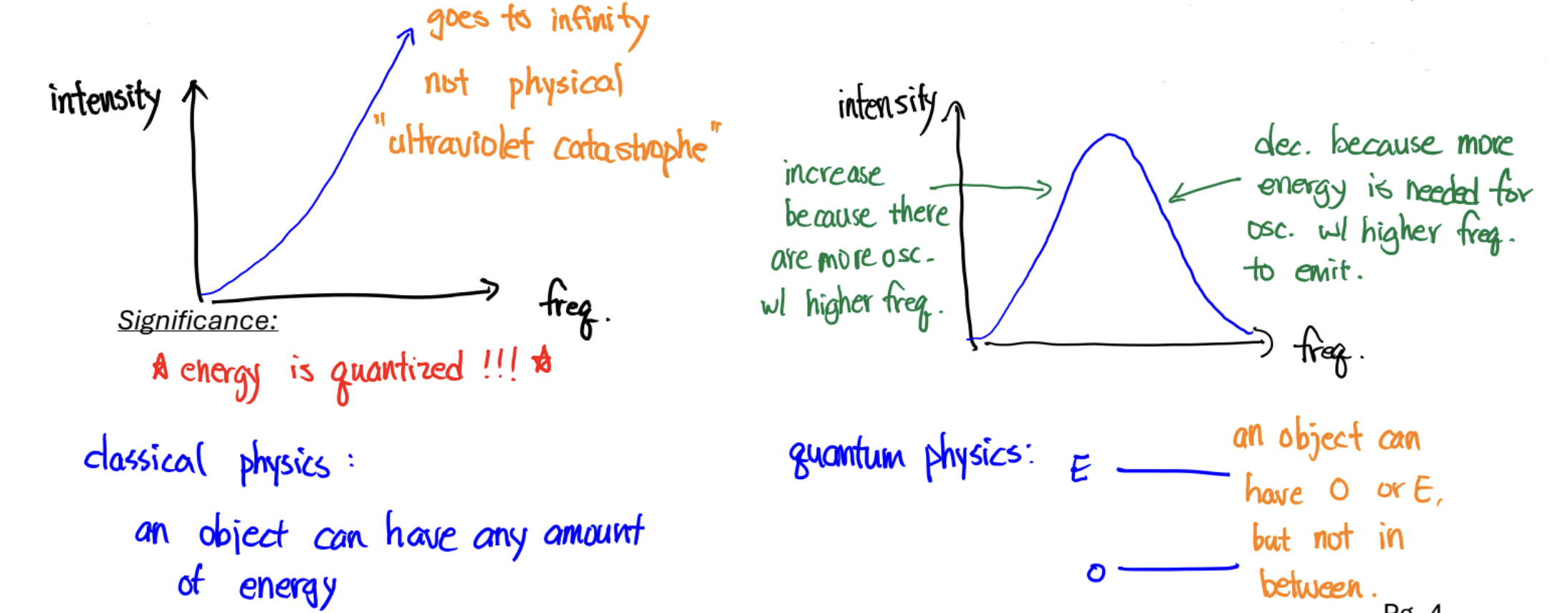

Blackbody Radiation

Significance: energy is quantized

For a blackbody (object), as temp increases, the frequency of its most intense color increases. This is because more energy is needed to turn on the light bulbs of higher frequency (energy to turn on/# of light bulbs is proportional to freq).There is more energy as temperature increases, so the higher frequency bulbs can be turned on. The “lighting up” of the higher frequency bulbs means the most intense color also shifts to a higher frequency.

Classical Physics vs. Planck (and quantum physics)

Classical Physics:

energy shared equally to all light bulbs

# of light bulbs proportional to its frequency

it can go up to infinity/objects can have any amount of energy

HOWEVER: not physical (doesn’t actually happen); “ultraviolet catastrophe“

LBs must have energy to give off electromagnetic radiation & # of LBs proportional to freq…

Planck:

energy is not distributed equally

energy given to each light bulb is proportional to the frequency

more energy needed to give energy to LB w/ high freq

fewer high freq LB can emit

ENERGY QUANTIZED!!!

quantum physics: object can have E or O but no b/w

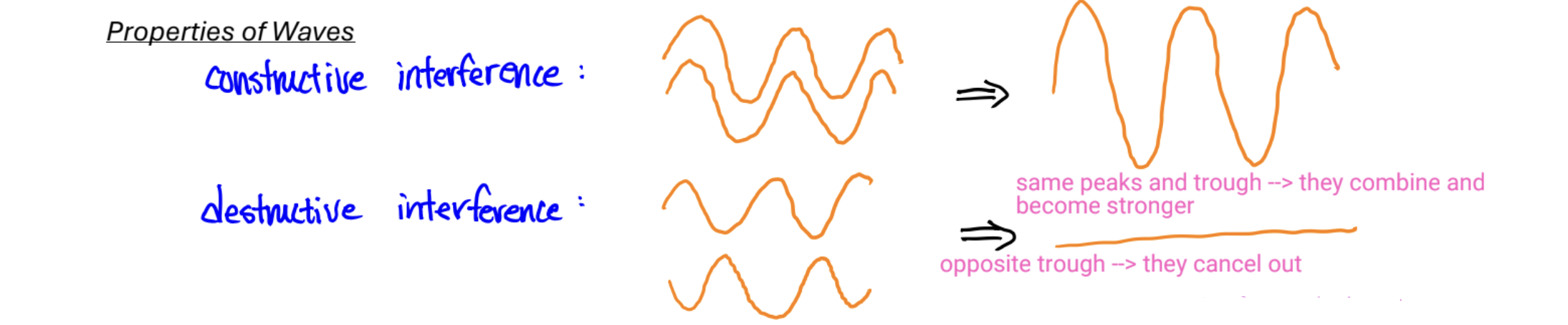

Properties of Waves

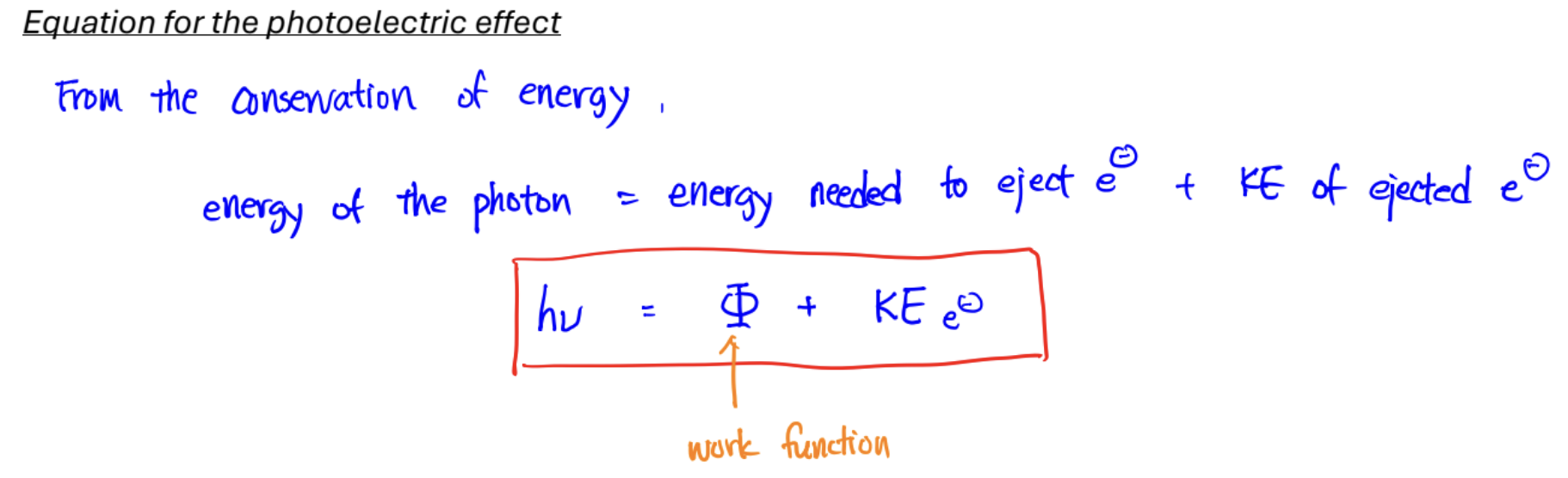

Photoelectric Effect

Experiment: shine light onto a metal plate; electrons bounce off

Einstein’s Explanation:

light exists as packets of energy, aka photons

the energy of a photon proportional to its freq: E = h*ν (ν is freq)

each photon can eject an e- if it has enough energy to break bond b/w metal and e-

leftover energy becomes KE of e- (@ threshold freq, it has just enough energy to break, KE = 0)

Significance: discovery of photons

Experimental observations:

higher intensity of light causes → more photons per sec → more e- ejected, but the KE of the ejected e- stays the same because energy of photon (E = h*freq) stays the same

There is a threshold frequency for different metals. Below the threshold frequency, photons don’t have enough energy to ejected e-

Increasing the frequency of the light → photons have more energy → increases KE of the ejected e-

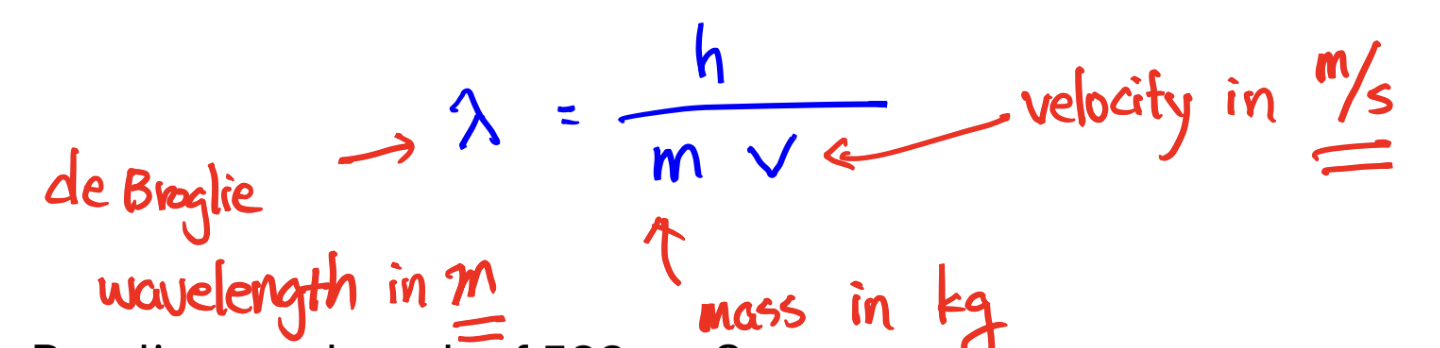

de Broglie wavelength (to find wavelength for PARTICLE, not photon)

Two-Slit Experiment

Experiment: light shone on a screen with two slits.

if e- behaves like particle, no interference and light goes straight through to create two solid lines corresponding to the slits

BUT multiple lines were created

This suggested that, instead of behaving like particles, e- behaves like waves and that resulted in the interference pattern (distance b/w bright spots related to wavelength)

bright spot: constructive interference

dark spot: destructive interference

Significance: e- has wave-like behavior

Composition of Atoms

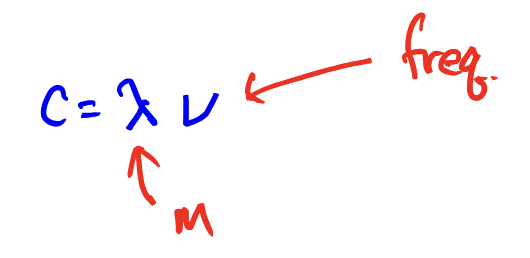

Electromagnetic Radiation: equation for calculating the wavelength of a PHOTON from its frequency

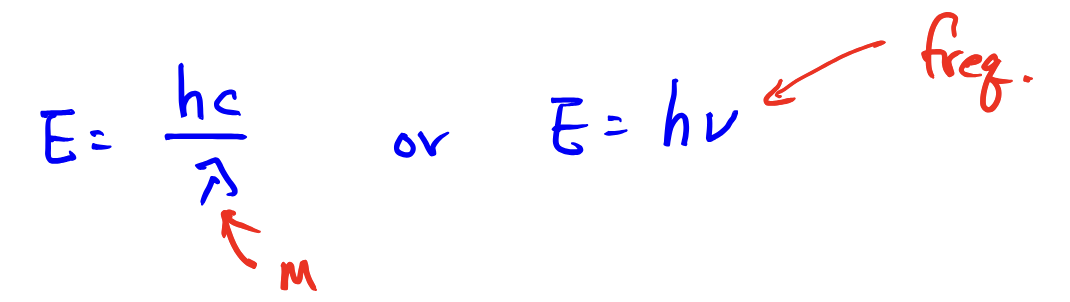

Electromagnetic Radiation: calculating the energy of a PHOTON from its frequency or wavelength

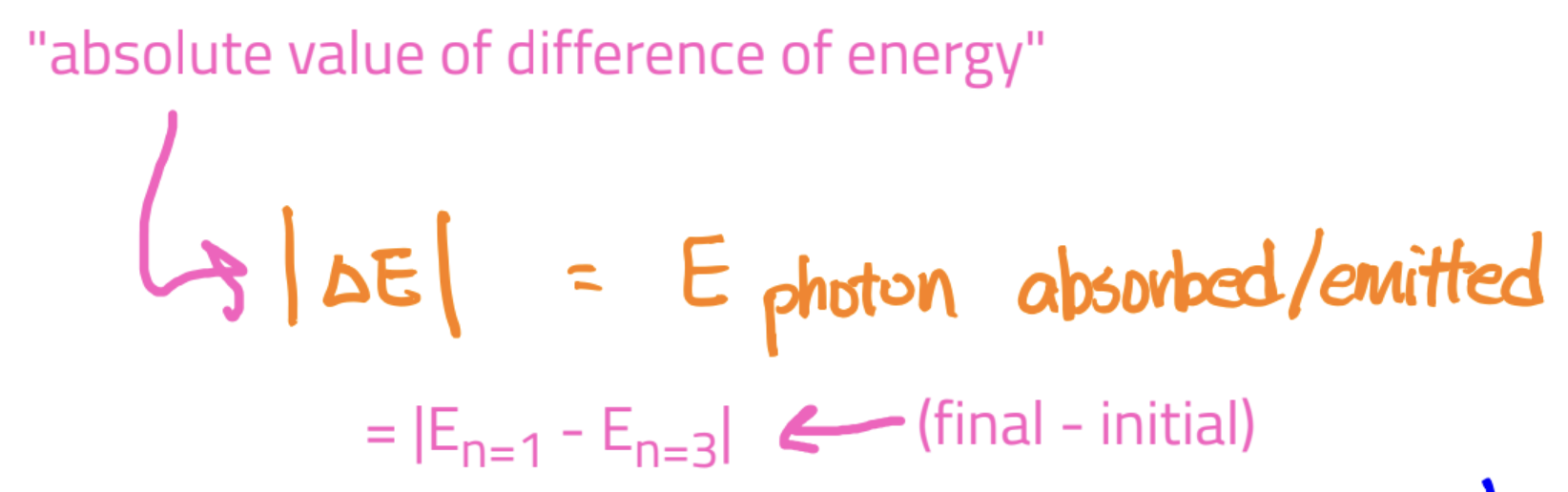

Absorption and Emission of Photons: definitions and equation

Absorption: when an e- absorbs a photon, it will jump to a higher level (only if the energy of the photon matches the energy difference)

Emission: when an e- drops to a lower level, it releases a photon whose energy is the differenc

Equation: for both,

E photon = |delta E| = |E of final - E of initial|

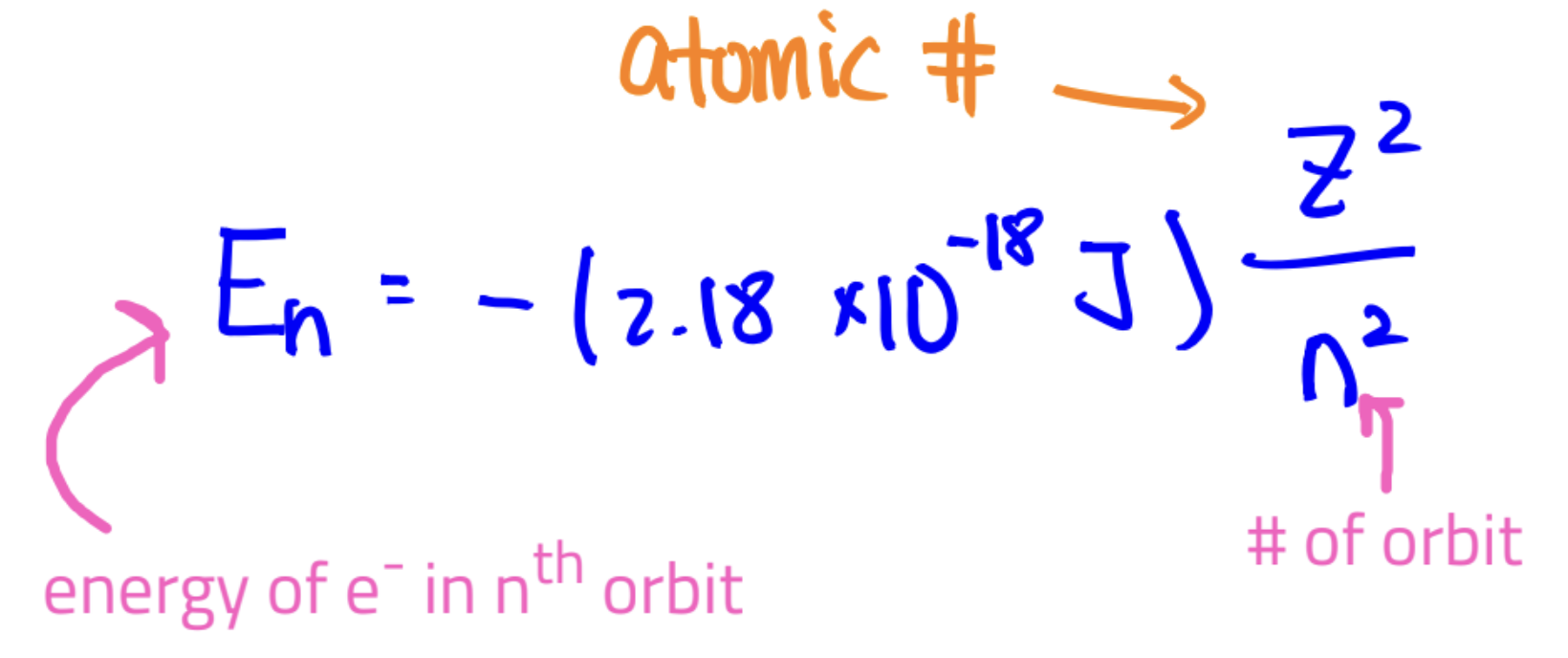

En for Bohr atom question

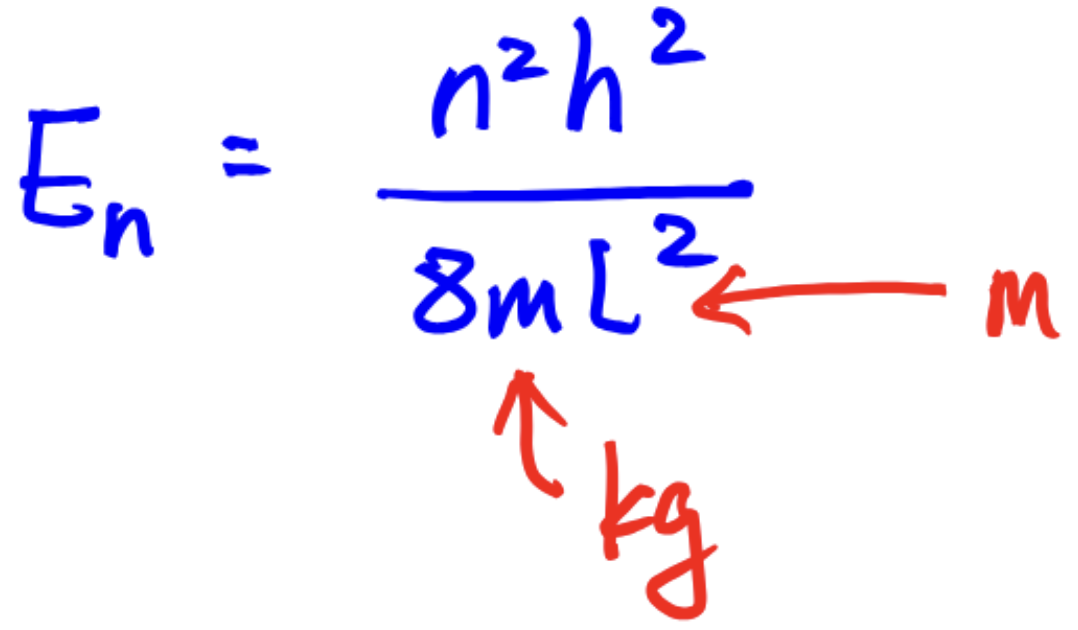

En for particle-in-a-box question

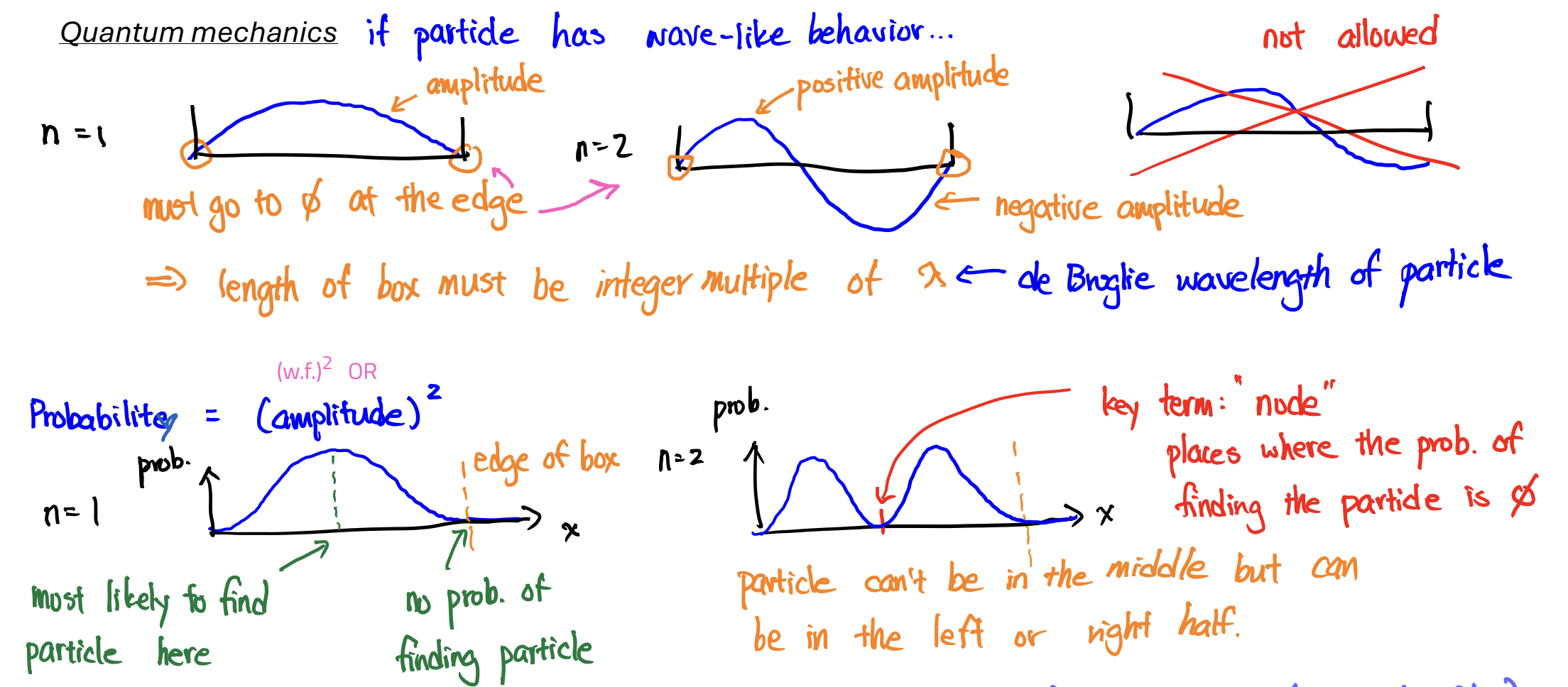

Wavefunction

a mathematical equation that describes the amplitude of a wave at different locations;

it has no physical meaning, but (wavefunction)² gives the probability of finding e-

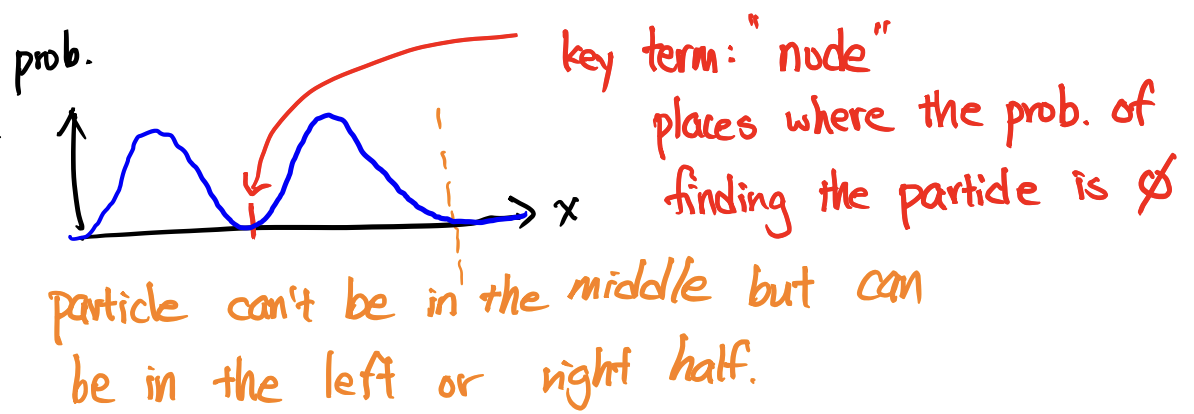

Node

probability of finding the particle is 0

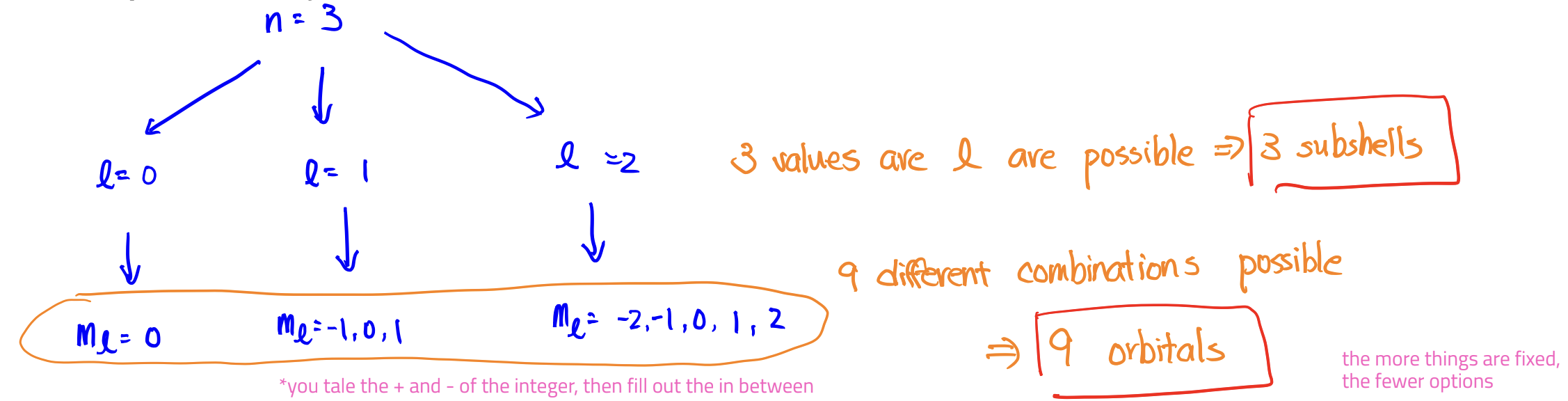

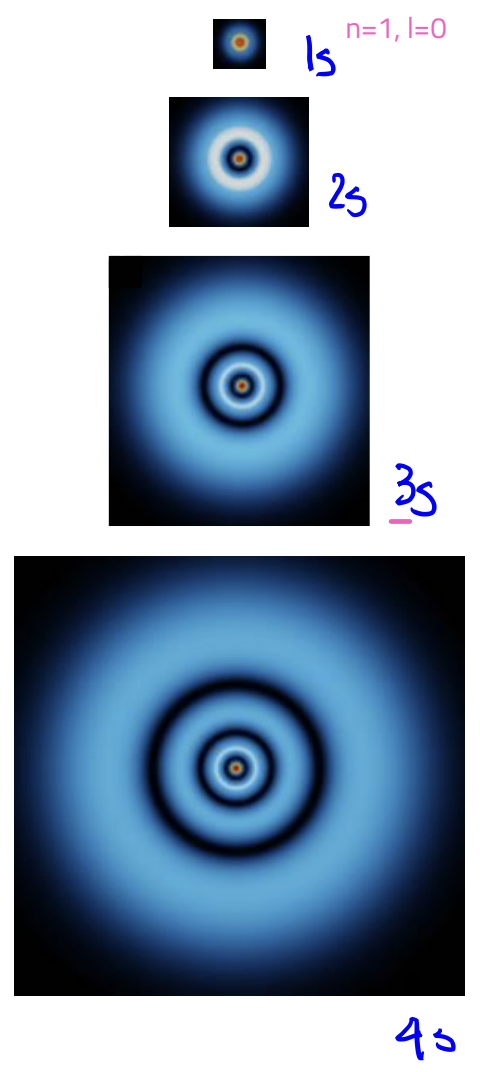

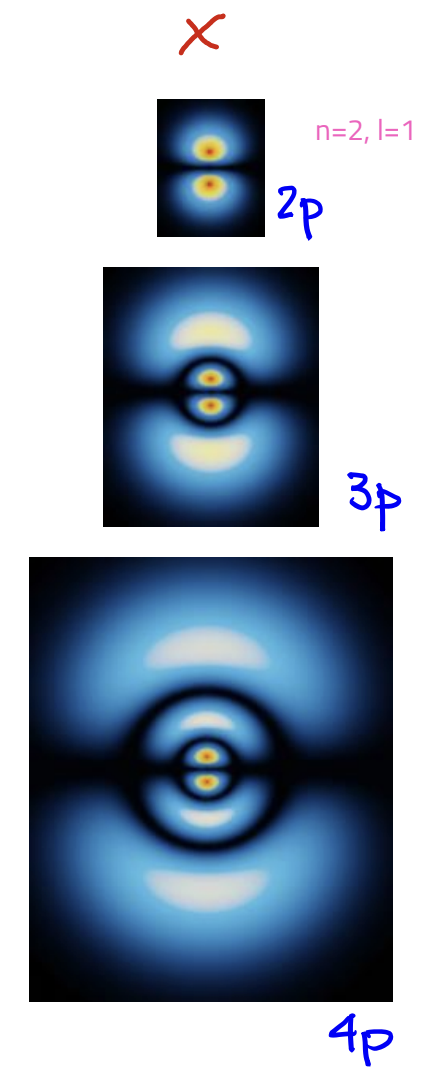

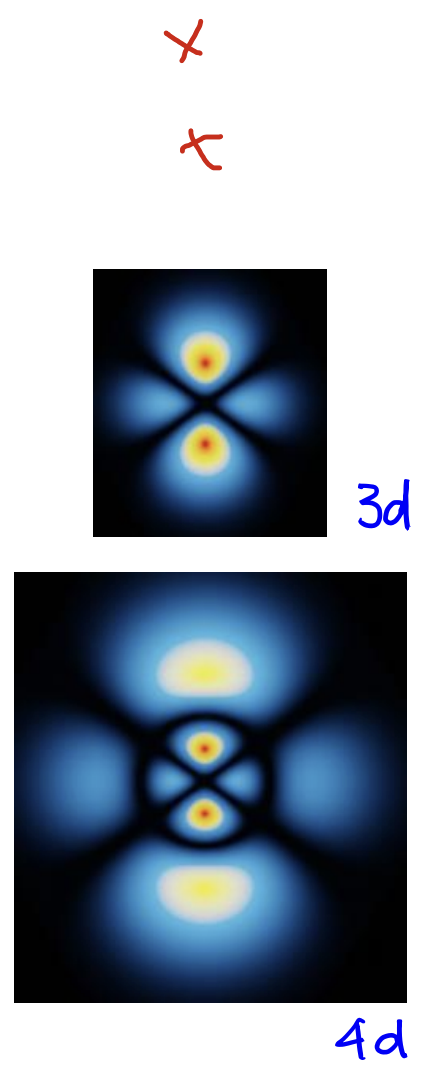

n (shell)

Name: Principal quantum number

Value: 1, 2, 3,…

Determines: size

Rules: smallest allowed value is 1

As 𝑛 increases, the probability of finding the electron farther away from the nucleus increases.

L (subshell)

Name: Angular momentum quantum number

Value: n - 1

Determines: shape

Rules: smallest allowed value is 1; largest, n-1

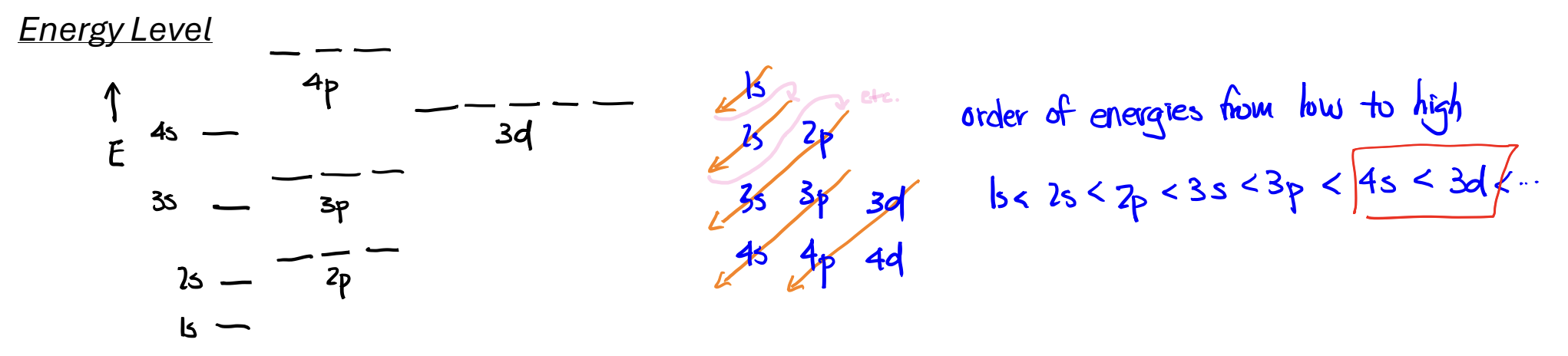

mL (orbital)

Name: Magnetic quantum number

Value: -L ≤ ml ≤ +L (the end points and what falls in the range)

Determines: orientation

Rules: allowed values depend on L

mS (spin)

Name: Spin quantum number

Value: +1/2, -1/2

Determines: spin of e-

How many subshells and orbitals are in the n = 3 shell?

(note: doesn’t specify L)

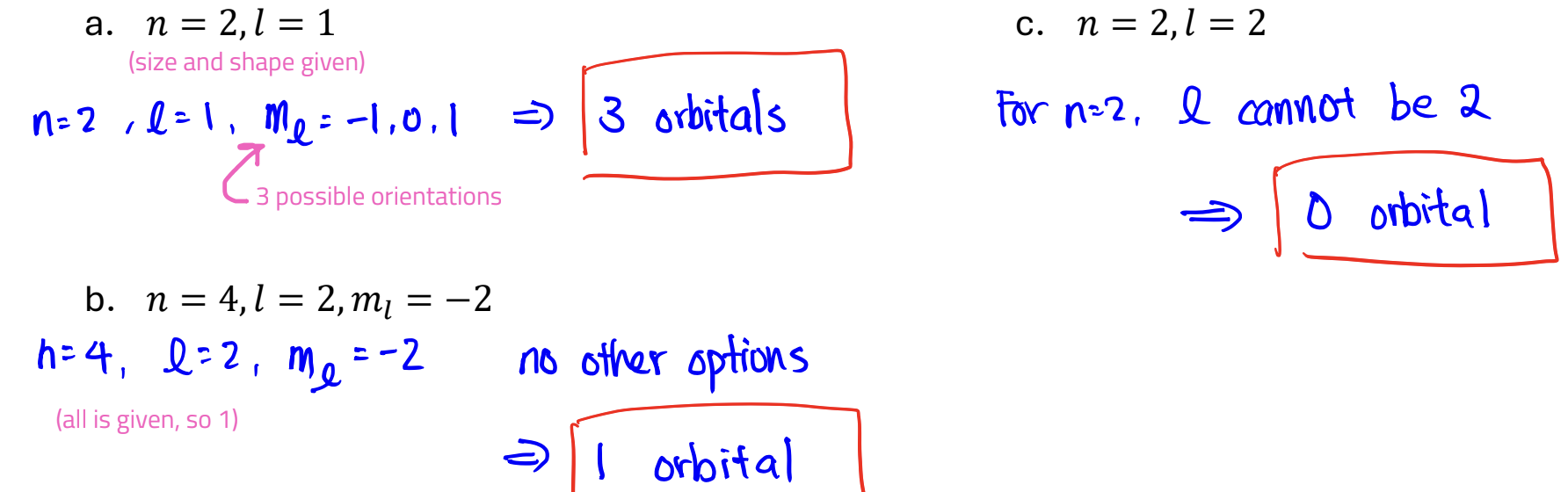

How many orbitals can have the following quantum numbers in an atom?

a. n = 2, l = 1

b. n = 4,l = 2, ml = −2

c. n = 2,l = 2

s-orbital

L = 0

angular nodes: 0

p-orbital

L = 1

angular nodes: 1

d-orbital

L = 2

angular nodes: 2

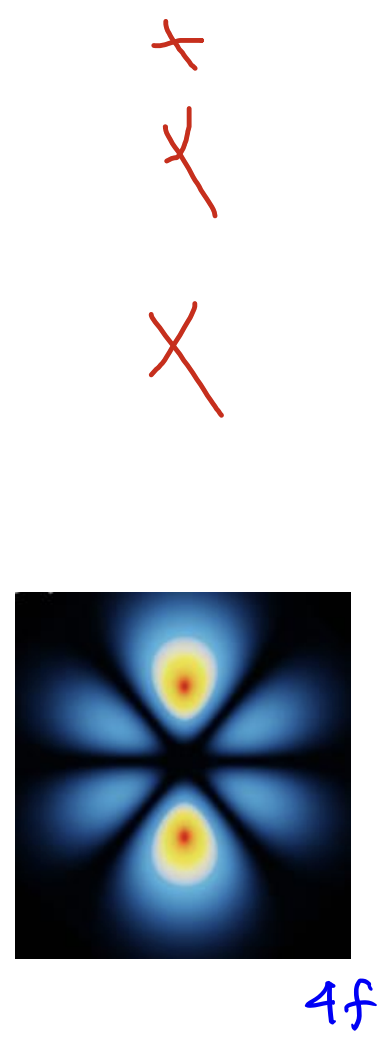

f-orbital

L = 3

angular nodes: 3

Effective Nuclear Charge

When there are multiple e-, e- found closer to the nucleus are less shielded

(if it’s closer, there are less other e- blocking; e-e repulsion is what causes the sheilding)

They will have a higher effective nuclear charge…

(it will feel more nuclear charge since it’s closer),

…making its energy lower (the stronger the attraction b/w the e- and nuc., the more stable and lower energy)

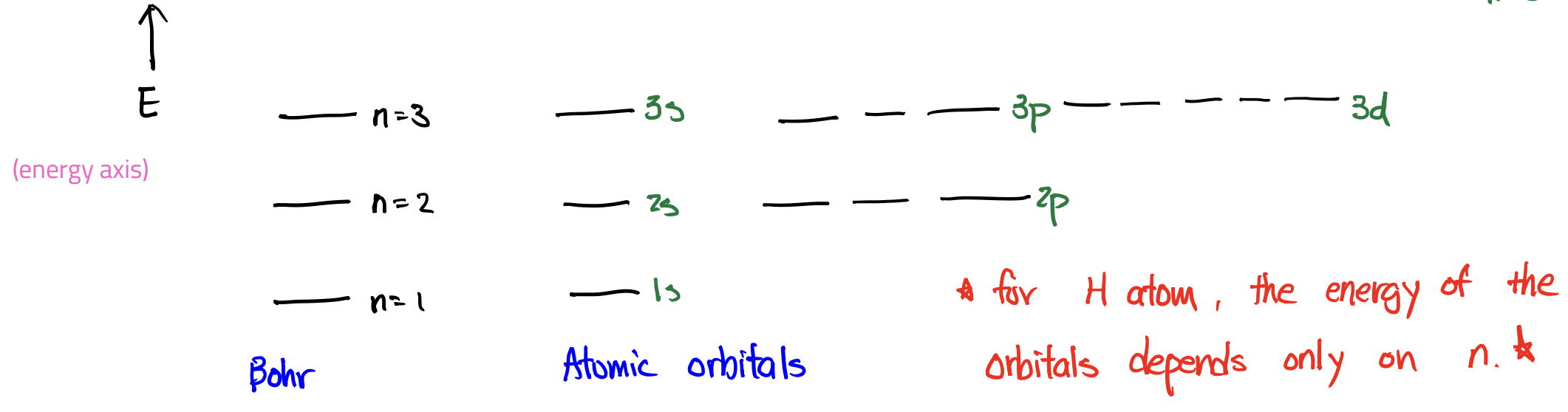

Energy Levels: Bohr vs Atomic Orbitals

Energy Levels: Atomic Orbitals

General Rules for Writing Electron Configuration

Aufbau Principle: add Z electrons, one after another, to the orbitals with the lowest energy,

Pauli’s Exclusion: no more than two electrons in any one orbital.

Hund’s Rule: If more than one orbital in a subshell is available, add electrons with parallel spins to different orbitals of the subshell rather than pairing two electrons in one of the orbitals (if all full w/ 1, then ok to add a 2nd)

General Rules for Writing Electron Configuration

Add Z electrons, one after another, to the orbitals with the lowest energy (Aufbau), but with no more than two electrons in any one orbital (Pauli’s Exclusion).

If more than one orbital in a subshell is available, add electrons with parallel spins to different orbitals of the subshell rather than pairing two electrons in one of the orbitals (Hund).

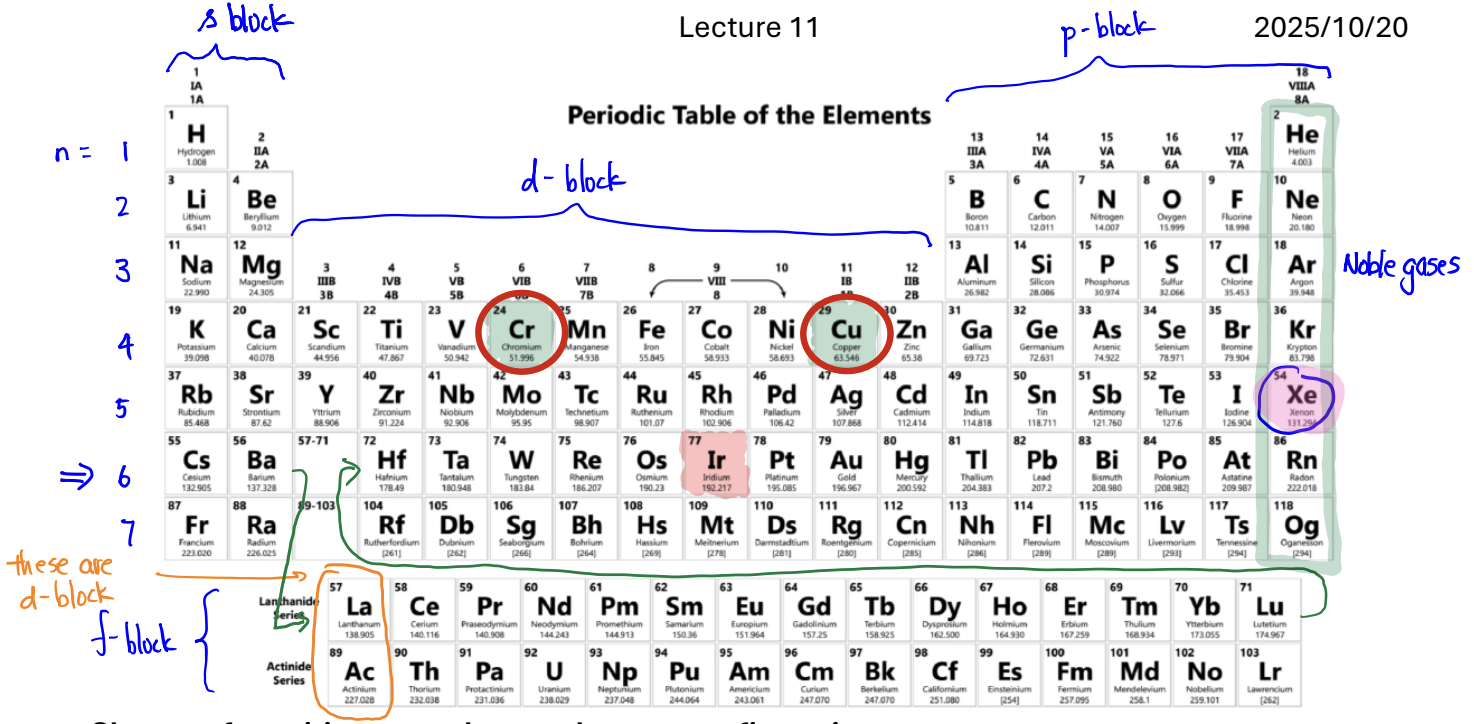

Shortcut for writing ground state electron configuration

Find the element on the period table.

Find the previous noble gas

Move toward the element of interest and fill as you go:

a. If you pass through s-block, fill ns orbital

b. If you pass through p-block, fill np orbital

c. If you pass through d-block, fill (n − 1)d orbital

d. If you pass through f-block, fill (n − 2)f orbital

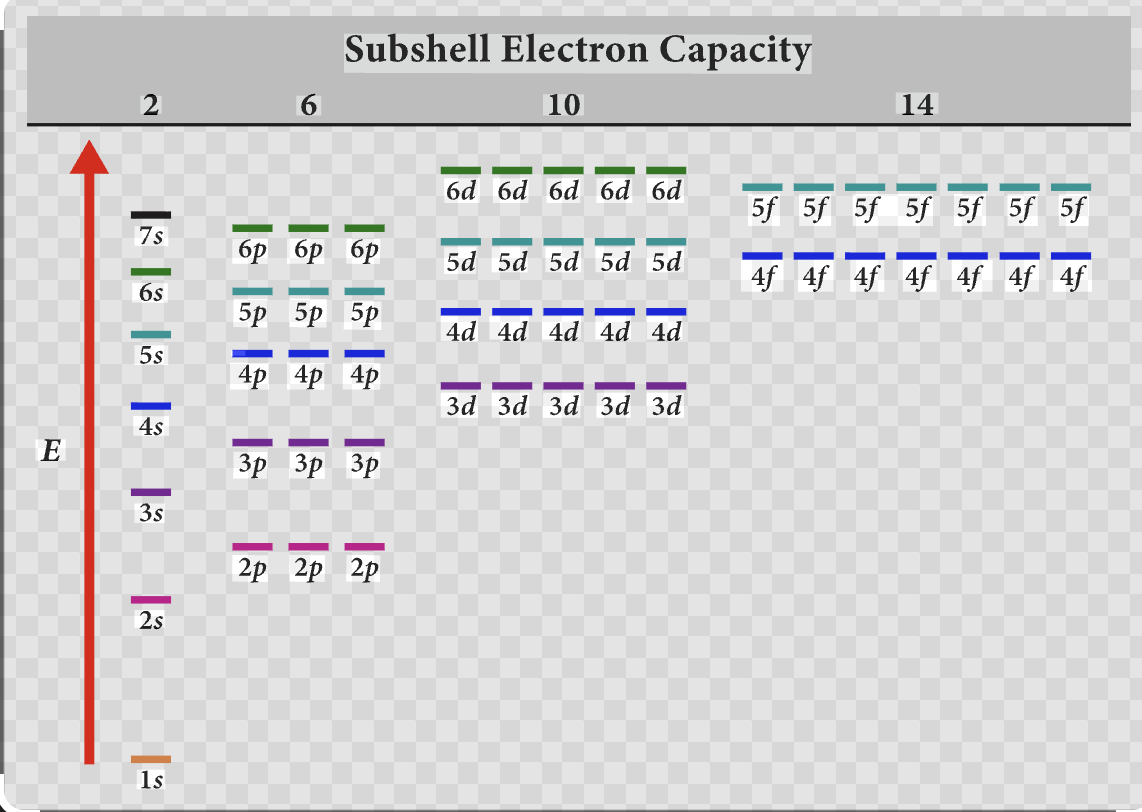

Subshell Electron Capacity

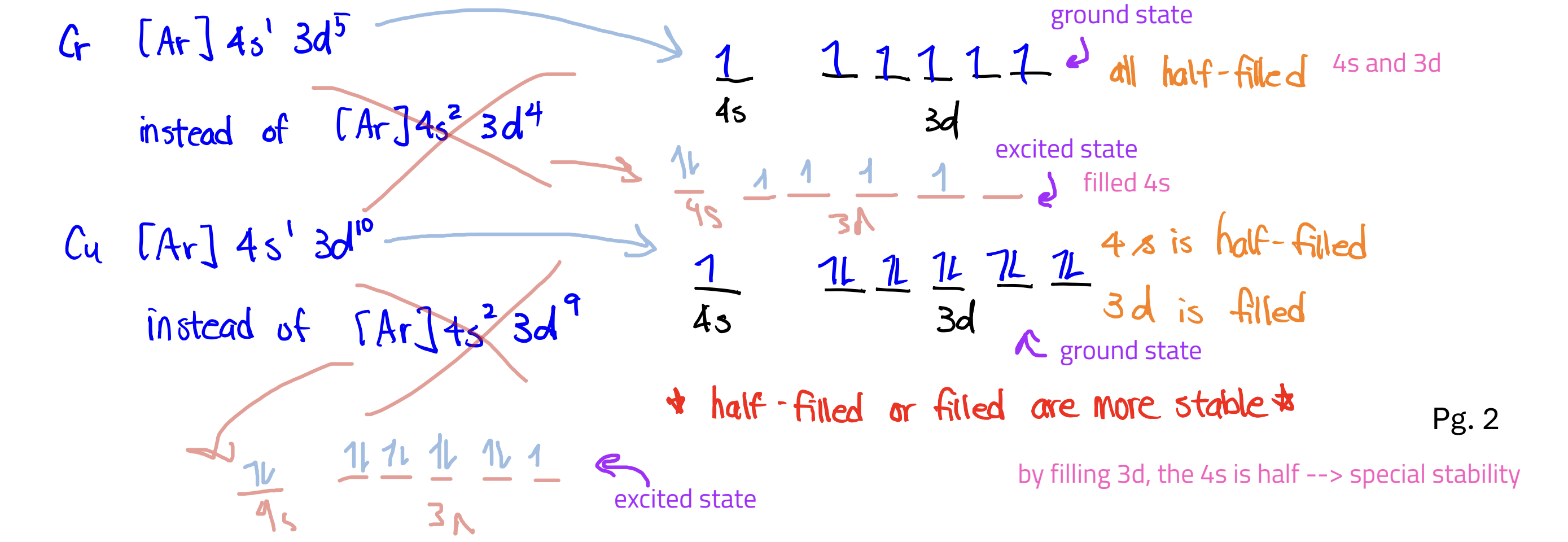

Two Exceptions of writing ground state e- configuration

Chromium (Cr) and Copper (Cu)

They’re written with one less e- in the s orbital—which is then added to the d orbital—because it would make them half filled; HALF-FILLED AND FILLED ARE MOST STABLE

Ground-state electron configuration

allowed and lowest energy; follows all rules

Excited-state electron configuration

allowed but at higher energy (more unstable); violates Hund’s rule (parallel and separate subshells before pairing) or Aufbau’s principle (lowest energy first)

Forbidden electron configuration

not allowed; violates Pauli’s exclusion (no more than two electrons in any one orbital) or have nonexistent orbitals

Trends in a column are mainly explained by changes in…

n (size of the orbital)

going down group → n inc. → e- farther from nucleus

Trends in a row are mainly explained by changes in…

effective nuclear charge

going right in period → nuclear charge inc. (add proton), but e- also added

HOWEVER e- in same shell not as good at shielding → effective nuclear charge (Zeff) inc. going right

Atomic Radius

the avg. distance of e- from the nucleus

inc. going down group (down column → n inc → size of orbital inc. → bigger atom)

dec. going right of period (go right → Zeff inc. → stronger nuc—e- attraction (e- pulled closer) → smaller atom)

Electron Affinity

energy released when an e- is added

larger EA = easier to add e- (wants)

smaller EA - harder to add e- (doesn’t want)

EA dec. going down group (down group → e- added to higher n → less favorable to add e-)

EA inc. going right of period, but lots of exceptions (right of period → Zeff inc. → stronger nuc.—e- attraction → more favorable to add e-)

Ionization Energy

energy required to remove e-

1st ionization energy = removing 1st e-; 2nd is removing second

larger IE = harder to remove

smaller IE = easier to remove

1st IE dec. going down group (down group → inc. n → e- farther than nucleus → easier to remove)

1st IE inc. going right of period (going right → Zeff inc. → stronger nuc.—e- attraction → harder to remove

Ionization Energy Exceptions

Exception #1: 1st ionization energy of B is lower than that of Be, and first ionization energy of Al is lower than that of Mg

for Al and B, removing from p orbital; for B and Mg, removing from s orbital

Exception #2: First ionization energy of O is lower than that of N, and first ionization energy of S is lower than that of P

half-filled subshells more stable → harder to remove

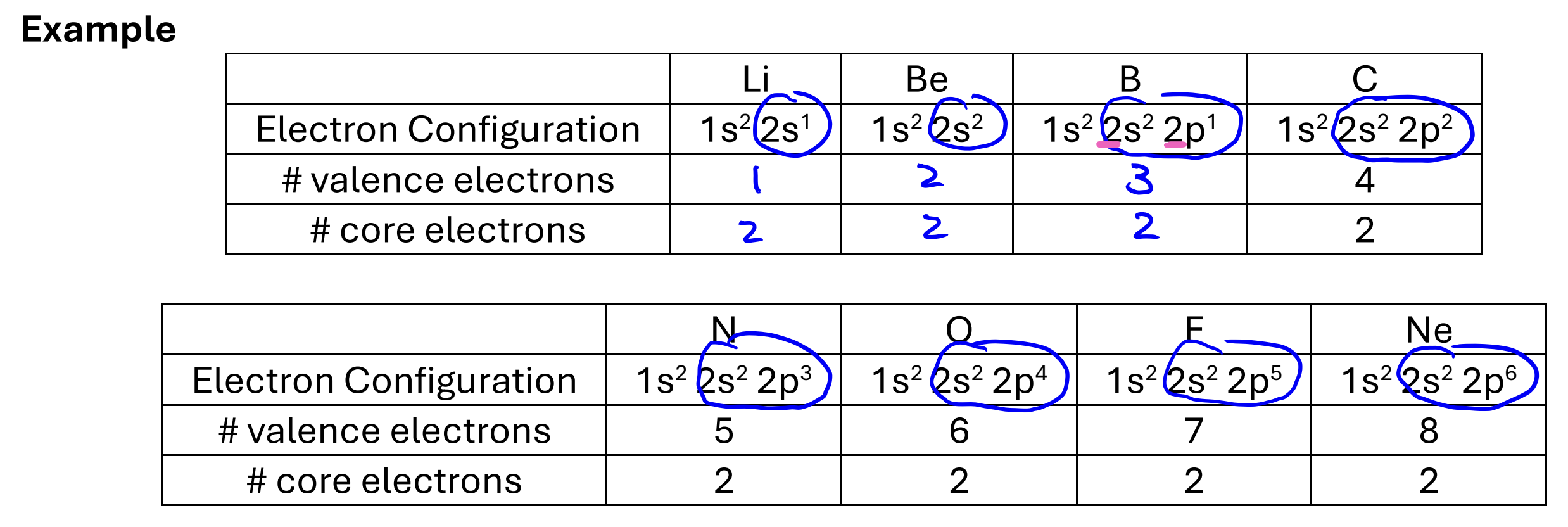

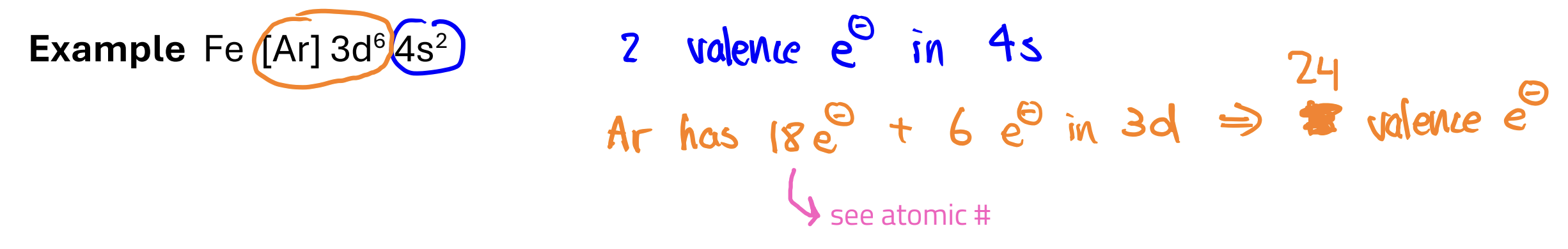

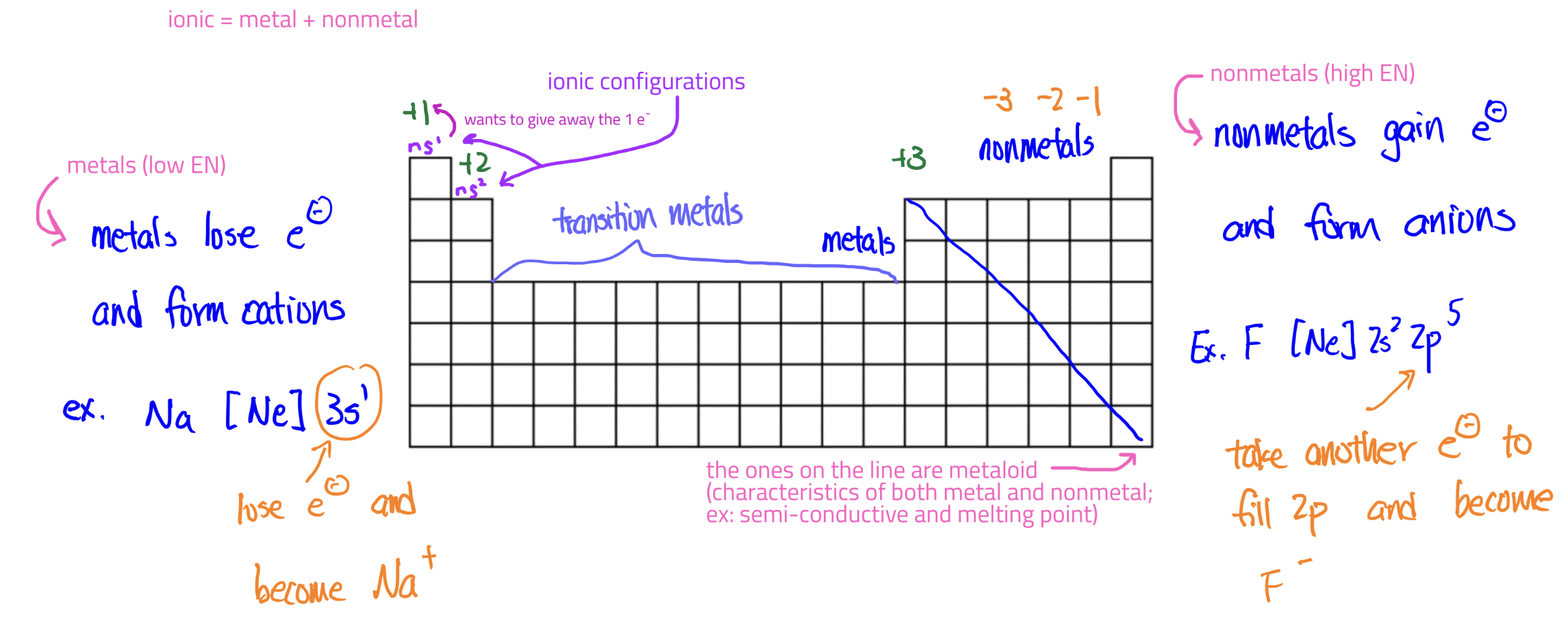

Valence Electons

electrons in the highest orbitals (highest n)

Core Electrons

all the other electrons not in the outermost orbital

Electronegativity

a scale indicating the electron-pulling power of an element (like a tug-of-war)

Larger differences in electronegativities means more unequal sharing of e-

dec. going down group

inc. going right period

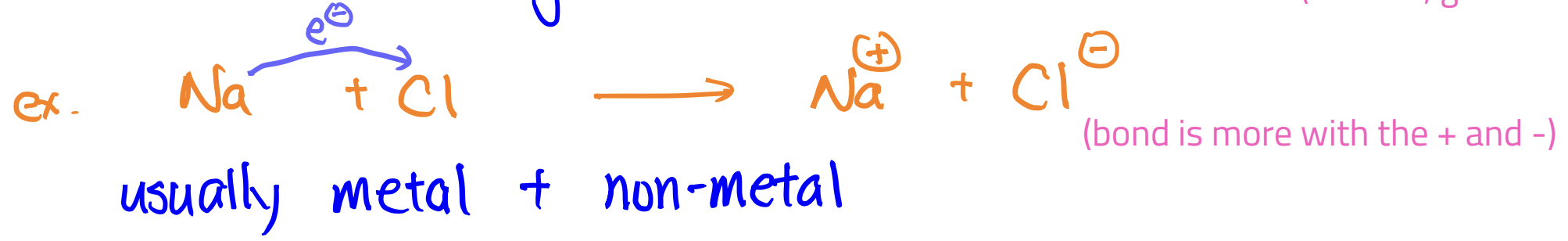

Ionic Compound

difference in EN is greater than 2.0 → e- is not shared (e- gets taken by one)

Covalent Compound

difference in EN is less than 2.0 → e- is shared

Nonmetals and Metals in Ionic Compounds

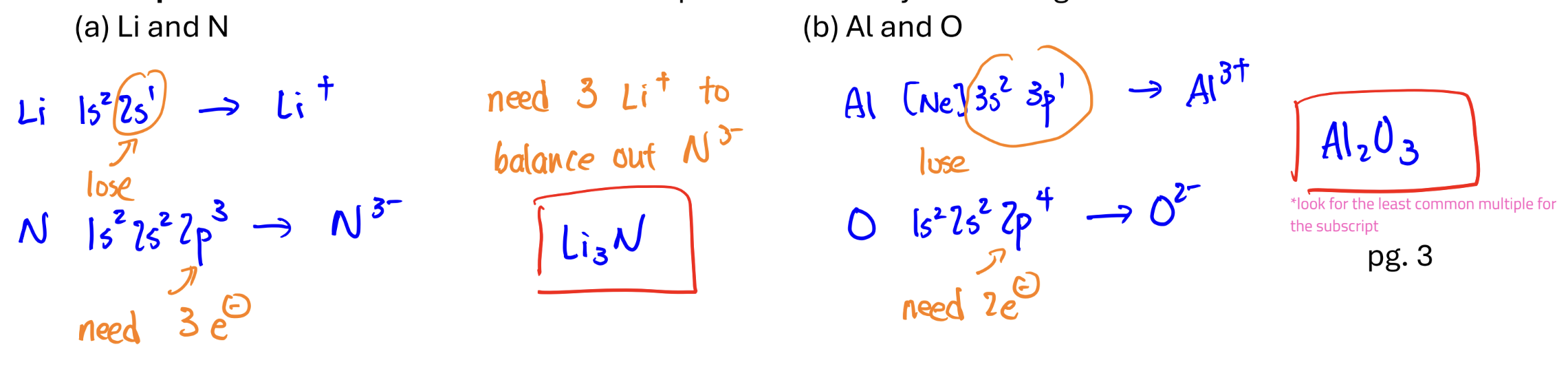

formula of an ionic compound

look at group number to see if it’ll take or get taken from; remember to balance out if necessary

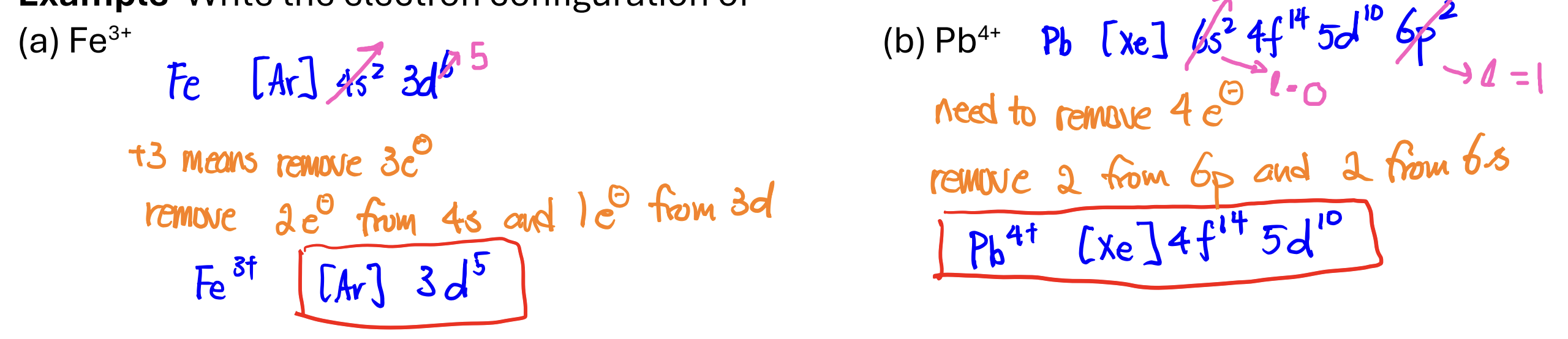

Electron Configuration of Transition Metal Cations

write the neutral electron configuration

remove e- from the highest n and highest L first; ex: remove from np, ns, (n-1)d

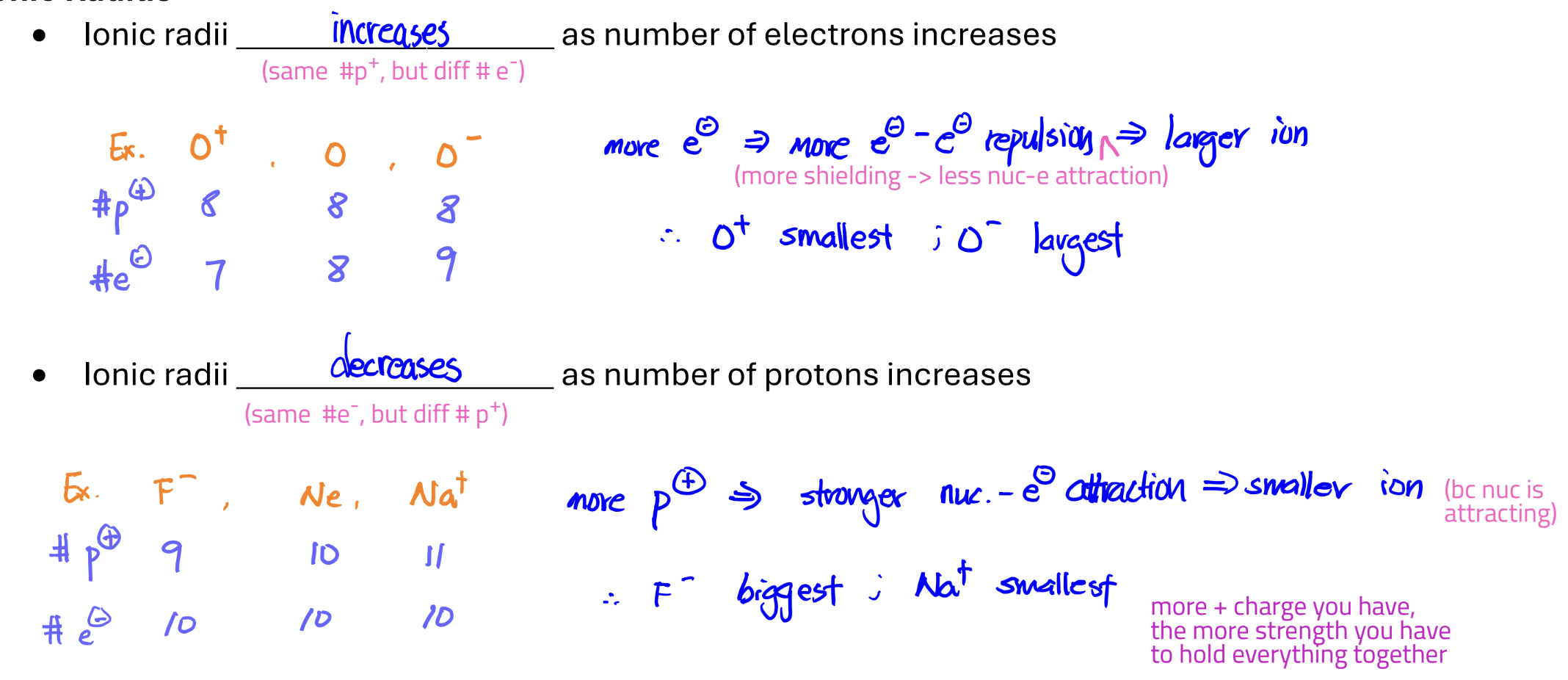

Ionic Radius inc./dec. when…

ionic radii inc. when # of e- inc.

ionic radii dec. when # of protons inc.

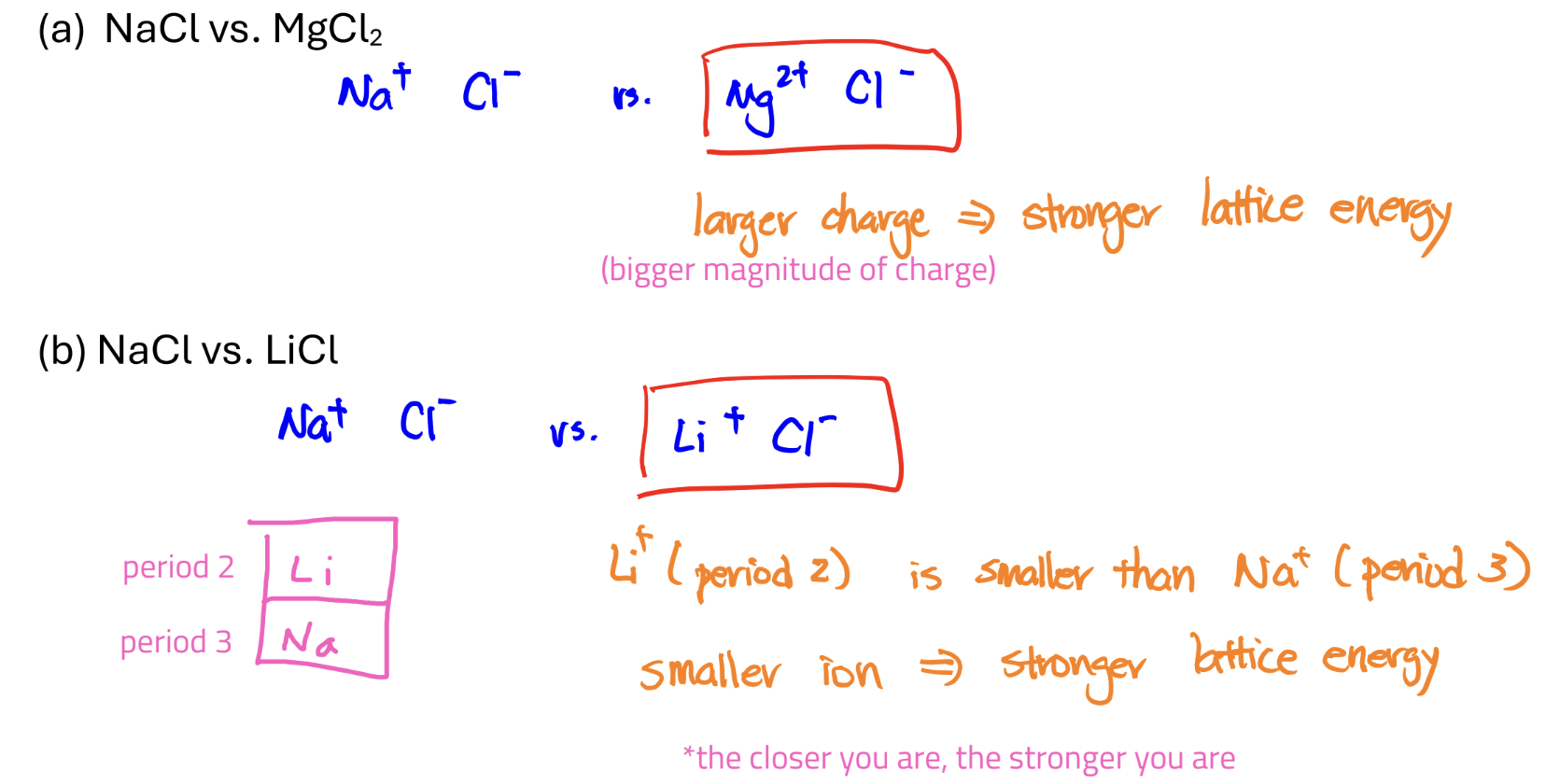

Lattice Energy

the attraction forces b/w cations and anions

can be thought of as the “bond strength” of ionic compound

stronger lattice energy → stronger attraction → more stable

bigger when charges are bigger or when ionic radii are smaller (when both charges and sizes are different, charge dominates)

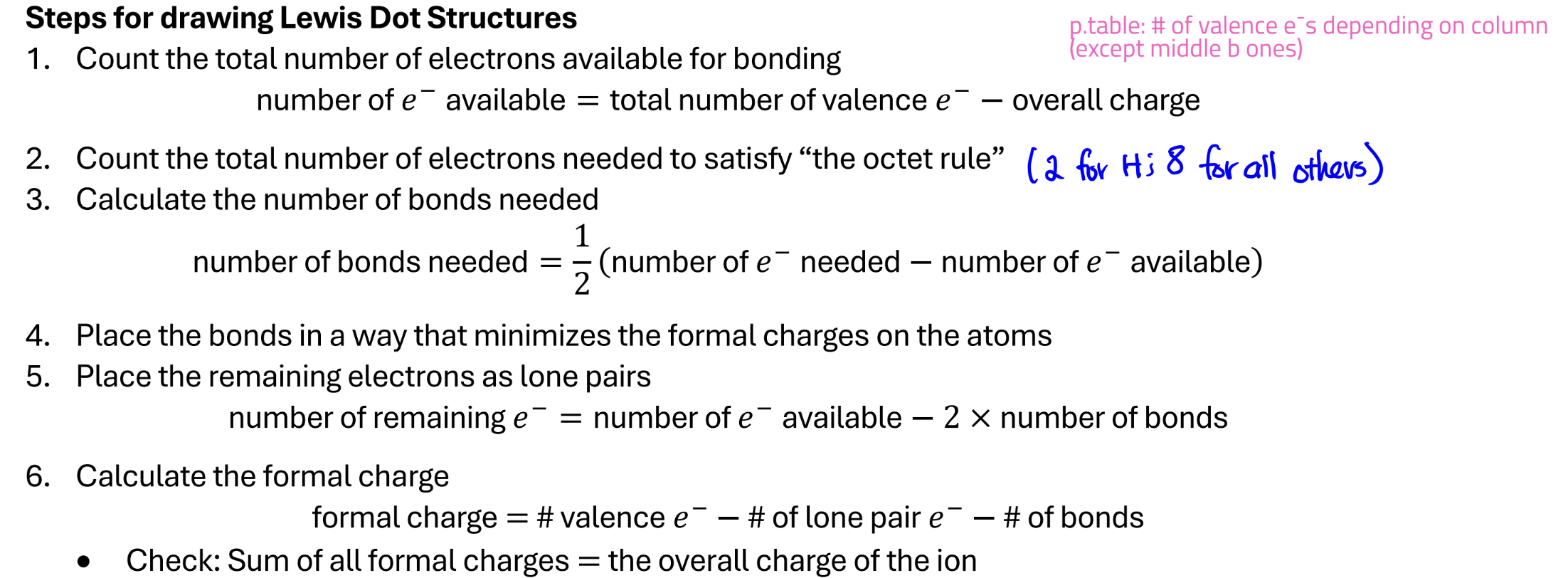

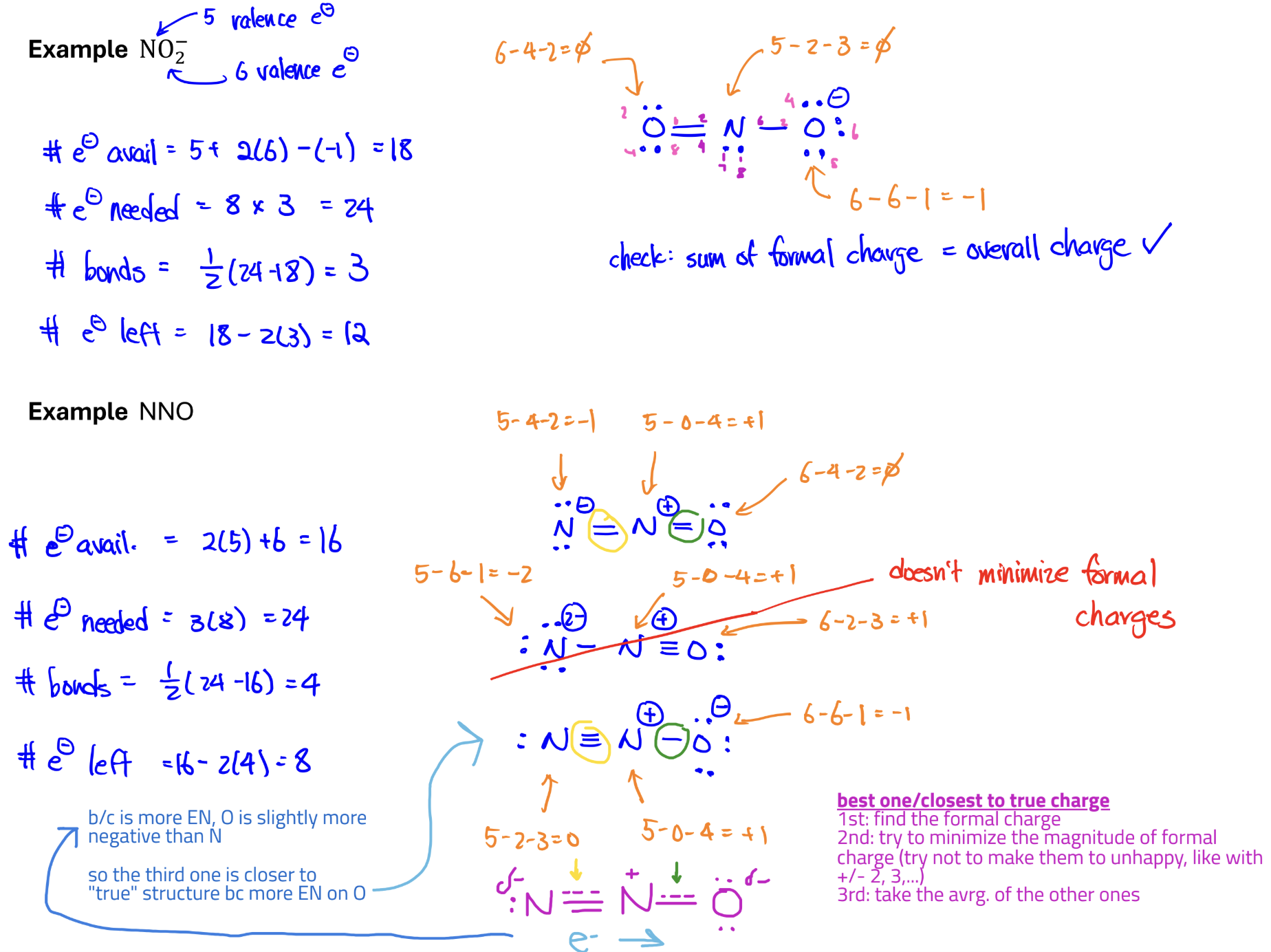

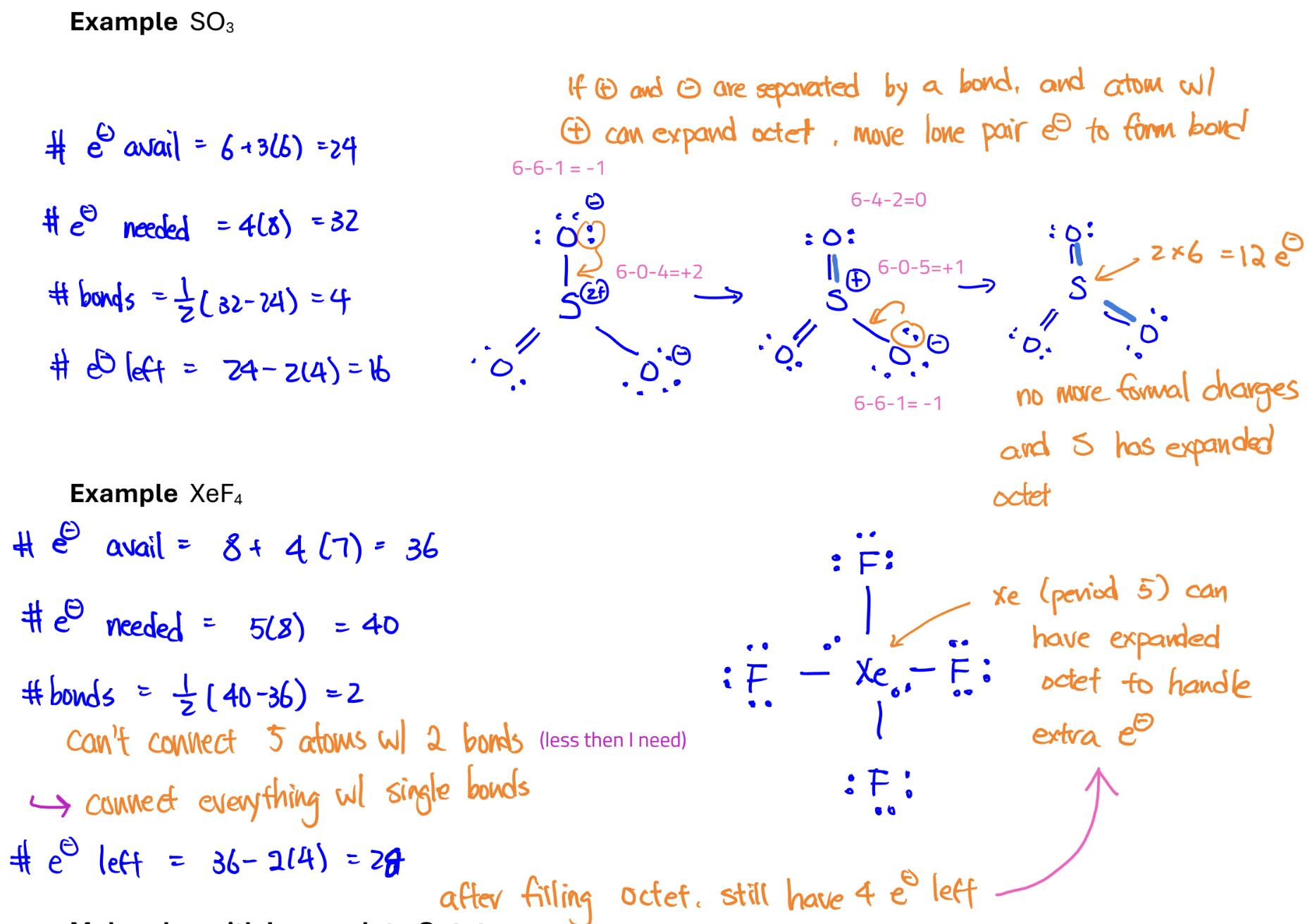

Lewis Dot Structure

helps us keep track of valence electrons

LDS of ionic compounds; try to satisfy octet rule

Steps for drawing Lewis Dot Structures

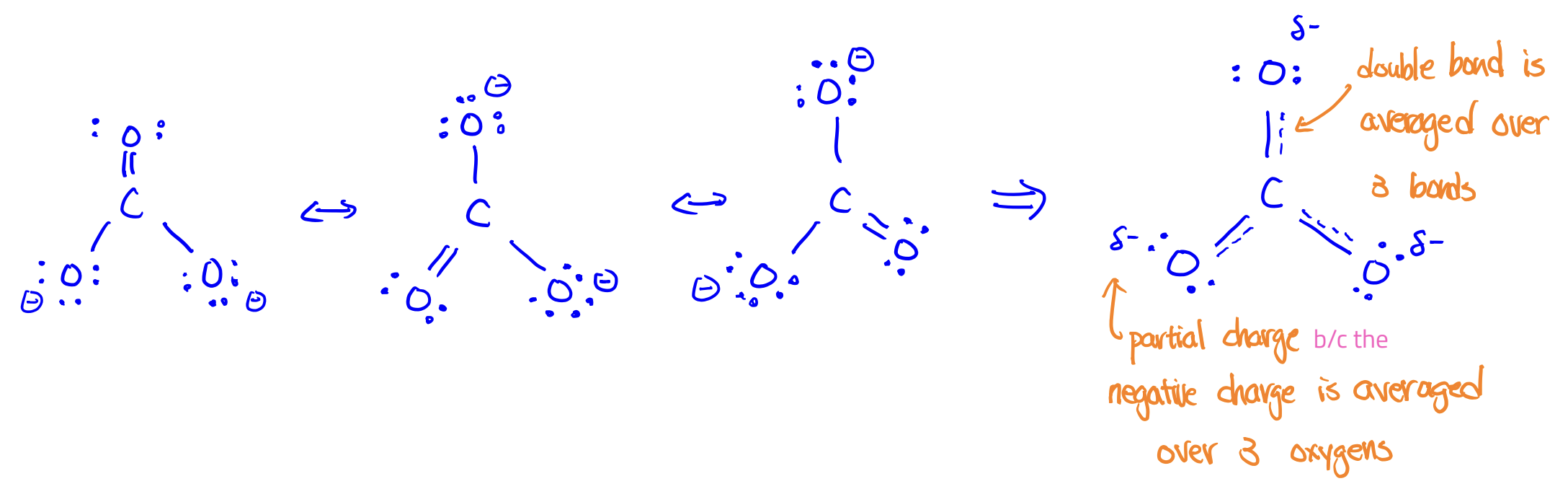

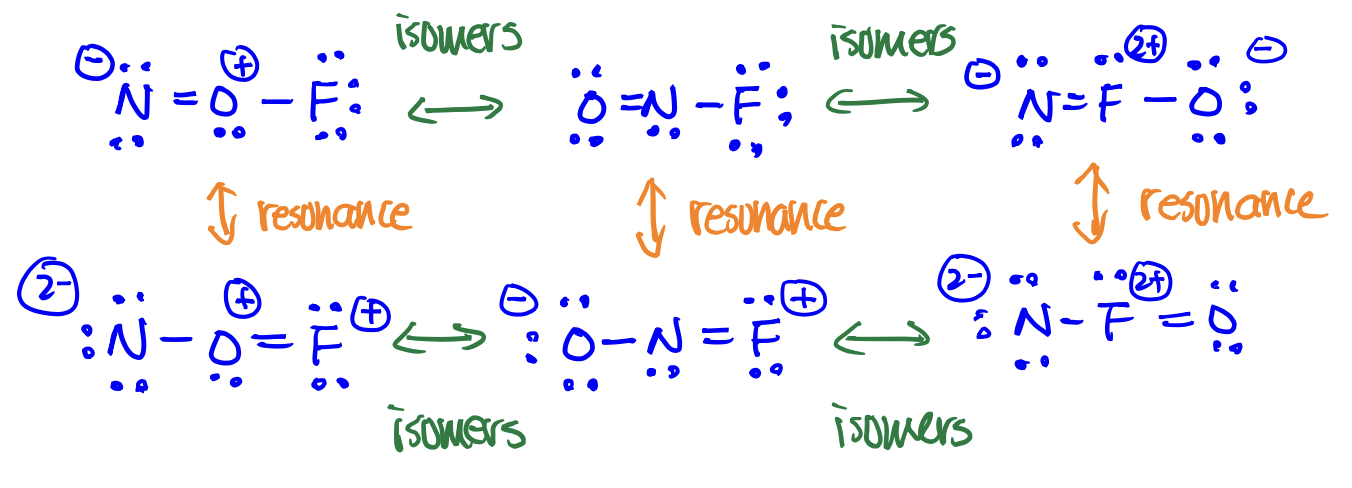

Resonance structures

structures with the same arrangement of atoms but with different arrangements of e-

Isomers

structures with different arrangement of atoms

*The true structure of a molecule is a blend of all the resonance structures

Lewis Dot Structure with Expanded Octet

For elements below period 2, you can expand octet to minimize formal charges.

Molecules with Incomplete Octet

B and Al can form molecules with incomplete octet, usually of the form AX3

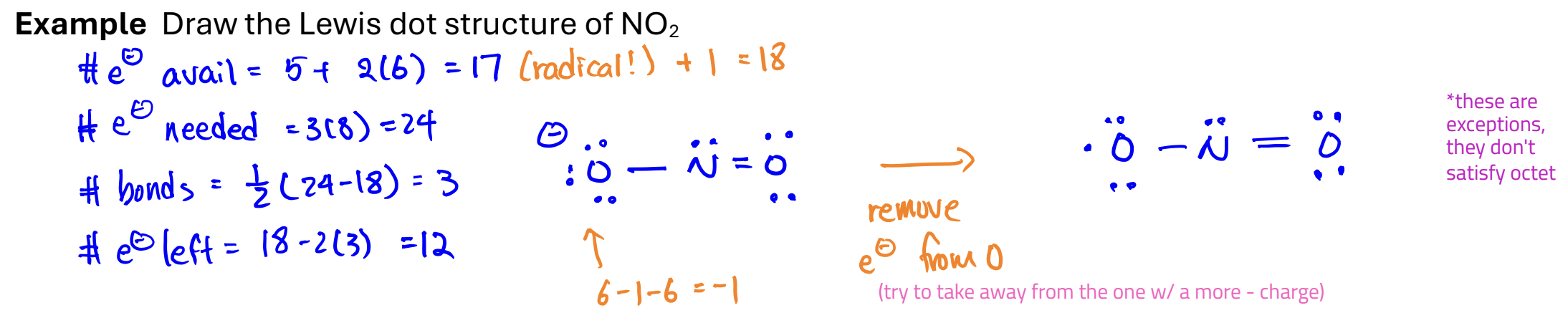

Radicals

molecules with unpaired e-

usually very reactive

Rules for drawing

Add an e- to the # of available electrons

Follow the typical rule for drawing a Lewis dot structure

Remove an e- from the atom with the most negative formal charge

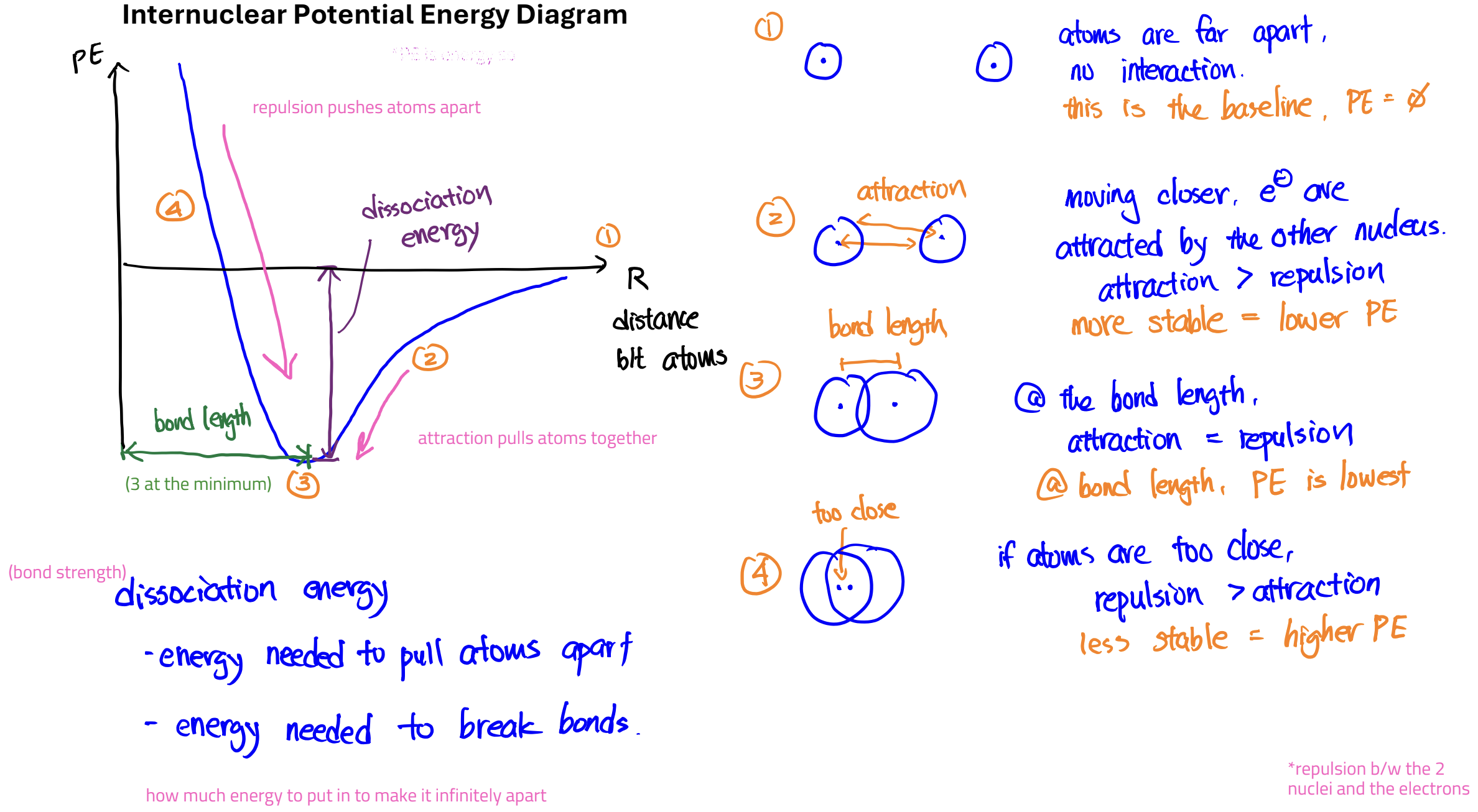

Internuclear Potential Energy Diagram

Larger bond dissociation energy (deeper well) means stronger bond (lower energy/more stable)

Relationship between Atomic Radii, Bond Length, and Bond Strength

Bigger atomic radius usually means longer bond length

Longer bond length usually means weaker bond

Multiple bonds: more bonds ➔ stronger bond ➔ shorter bond length

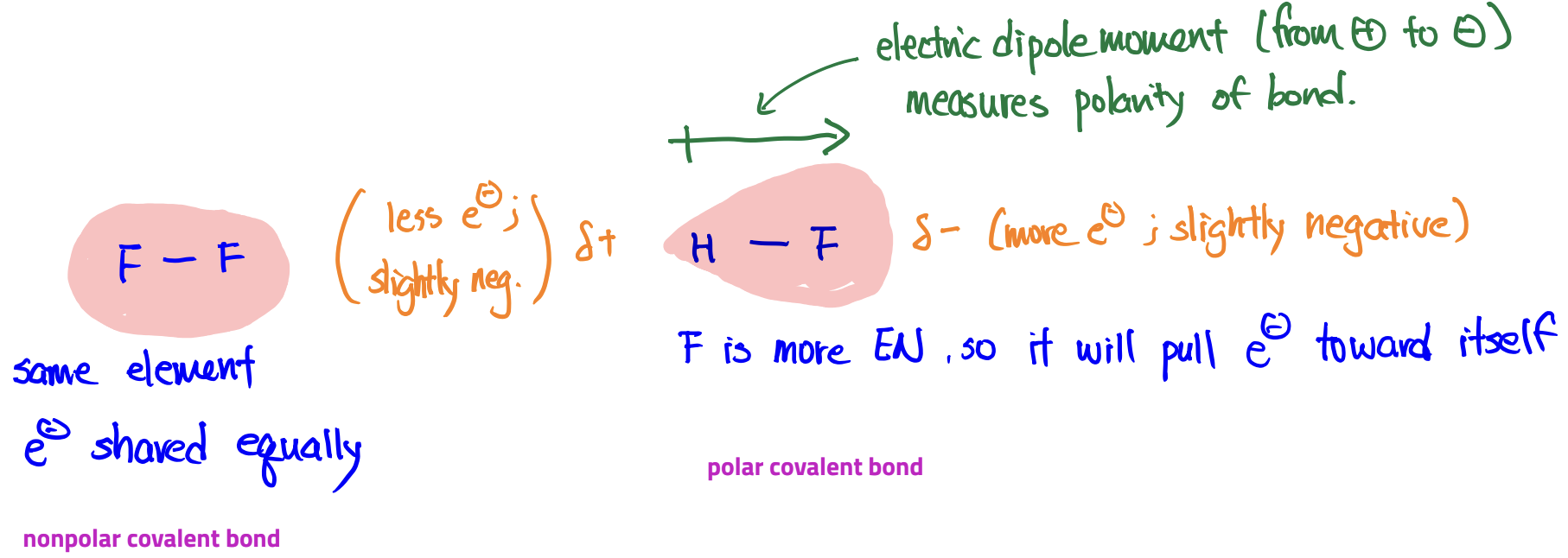

Polar covalent bond vs. nonpolar covalent bond

All covalent bonds between different elements are polar to some extent

polar due to difference in EN

Only covalent bonds between atoms of the same element are nonpolar (exceptions: C-H and Si-H)

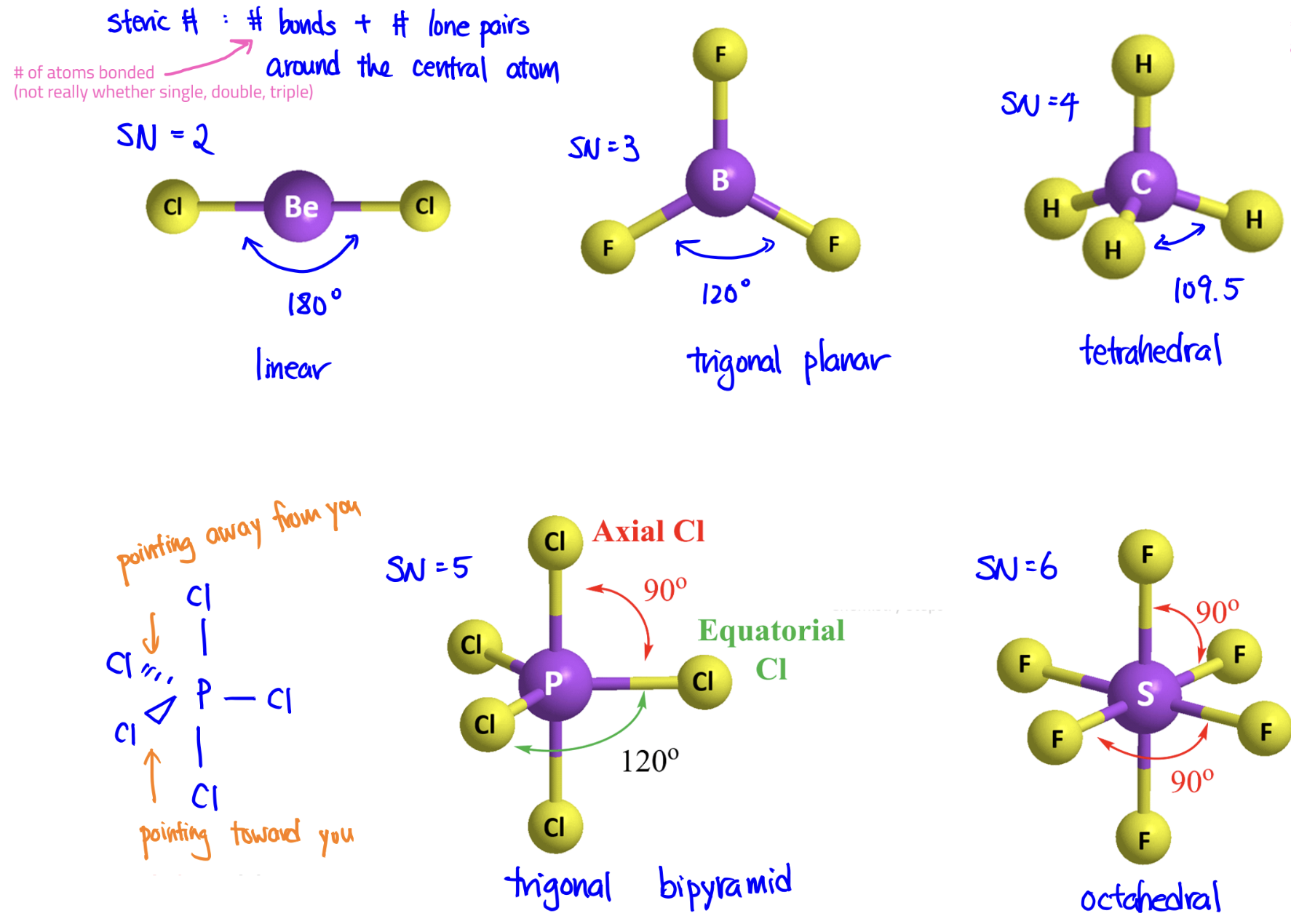

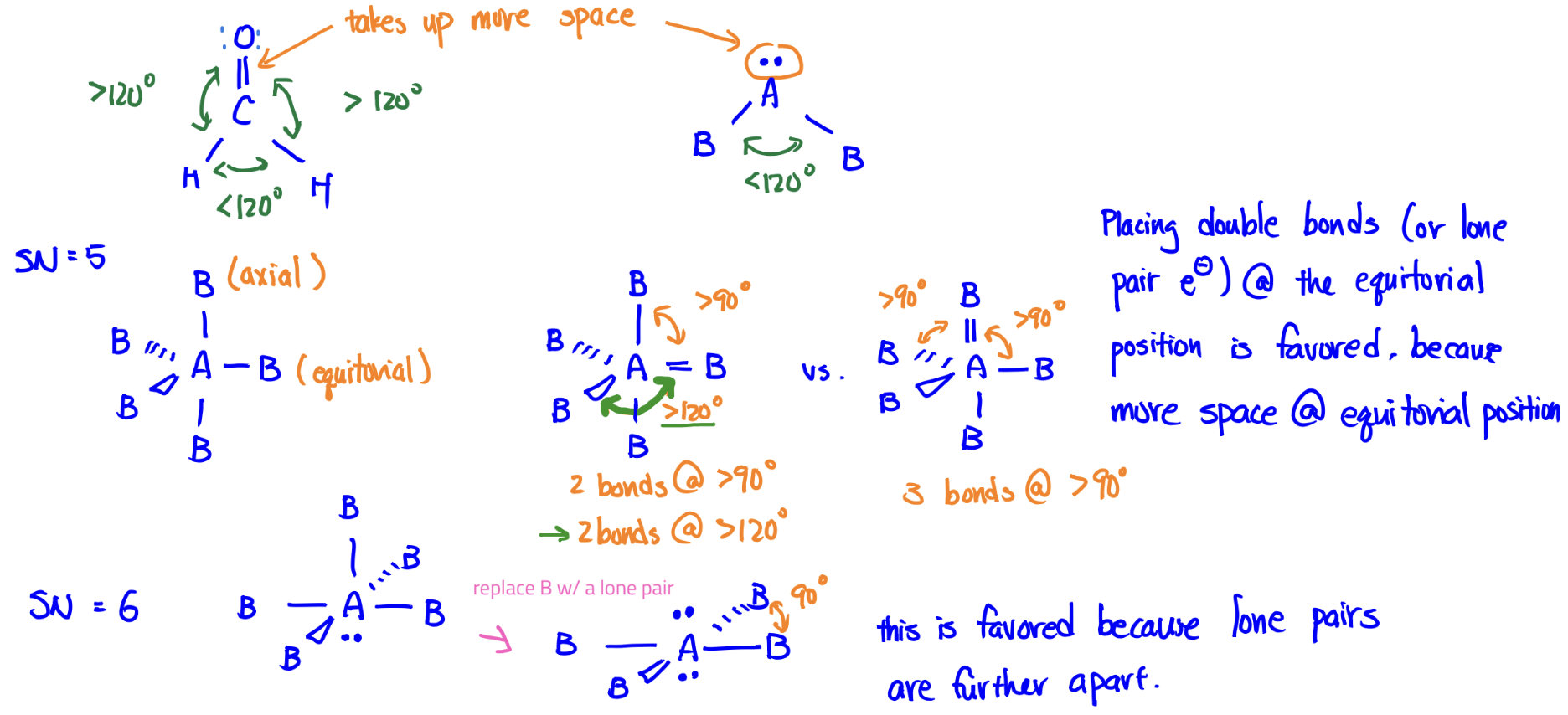

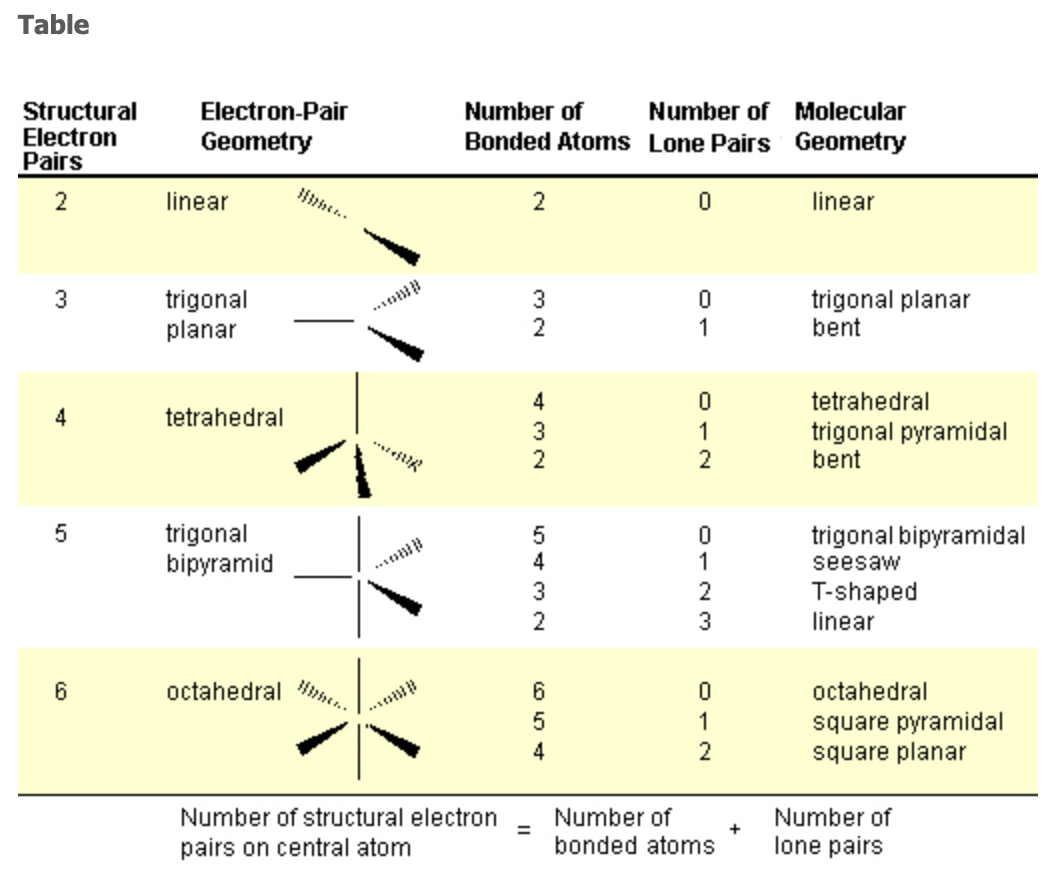

VSEPR Model

good at explaining shape; can help predict polarity

Bonds and lone pairs repel one another and, to minimize their repulsions, the bonds and lone pairs move as far apart as possible while maintaining the same distance from the central atom.

Steric Number = # bonds + # lone pairs around central atom

Due to repulsions, lone pairs and double bonds take up more space than single bonds and distort the geometry of the molecules.

Molecular Geometry Table

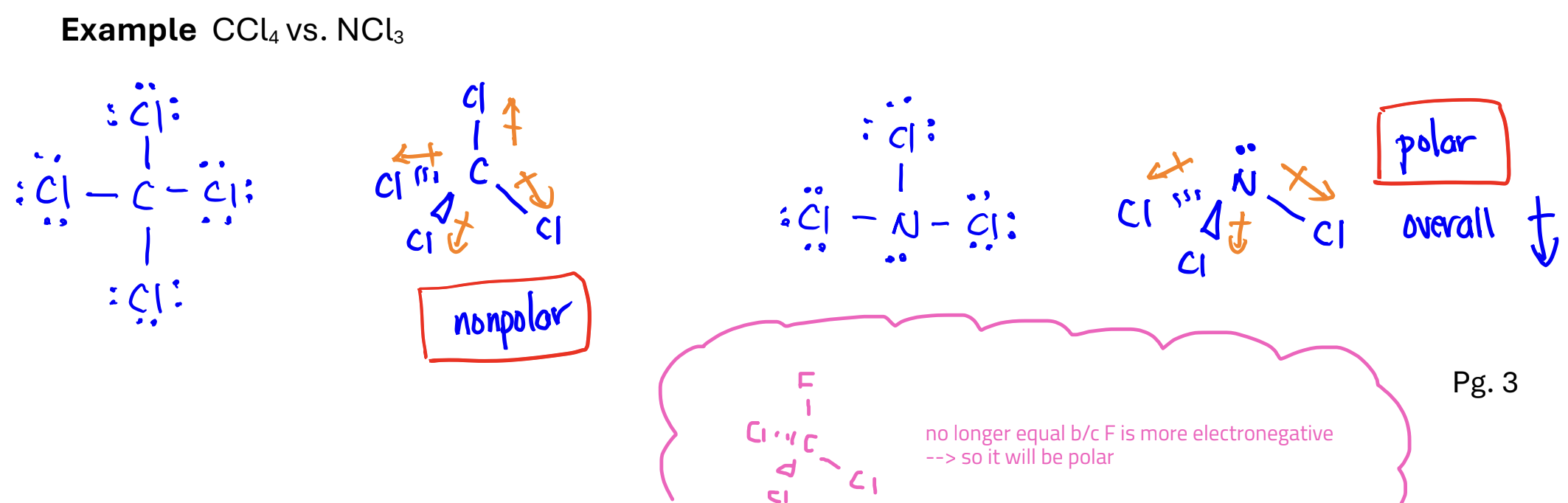

Polar covalent bond

a bond with a non-zero electric dipole moment

Polar Molecules

a molecule with a non-zero electric dipole moment

Nonpolar molecules

a molecule with zero electric dipole moment

A nonpolar molecule can have polar bonds

Steps for determining if a molecule is polar

Determine the shape of the molecule

Find all the polar bonds and draw the electric dipole moment

See if the polar bonds cancel each other out

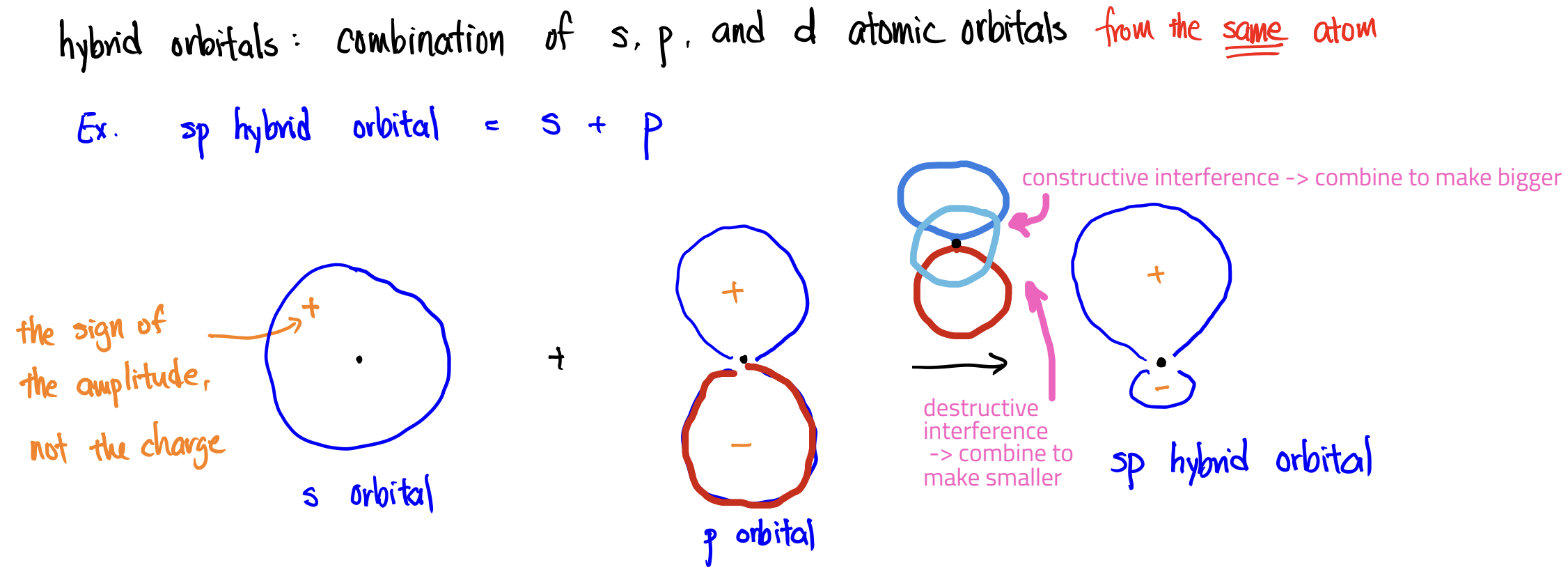

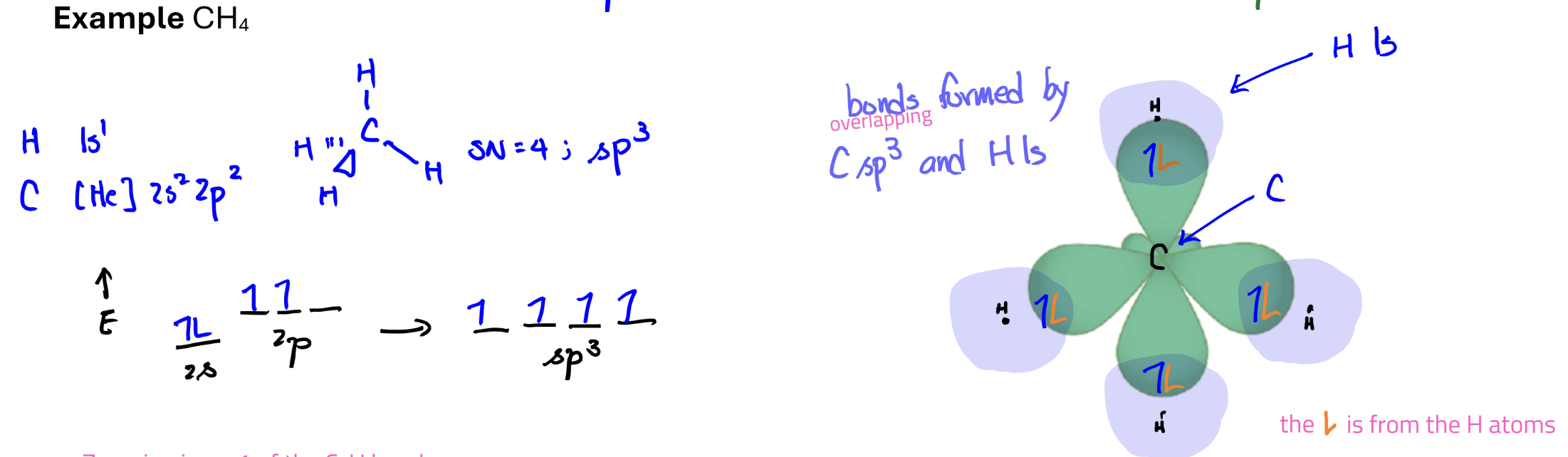

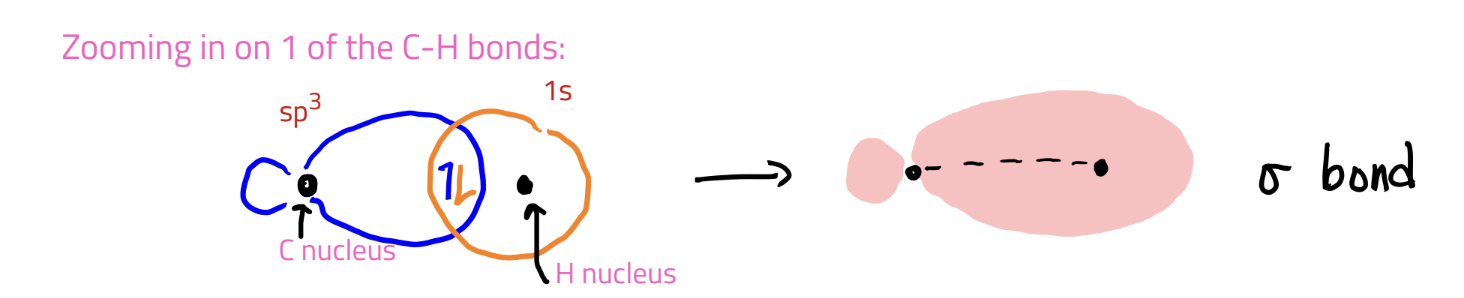

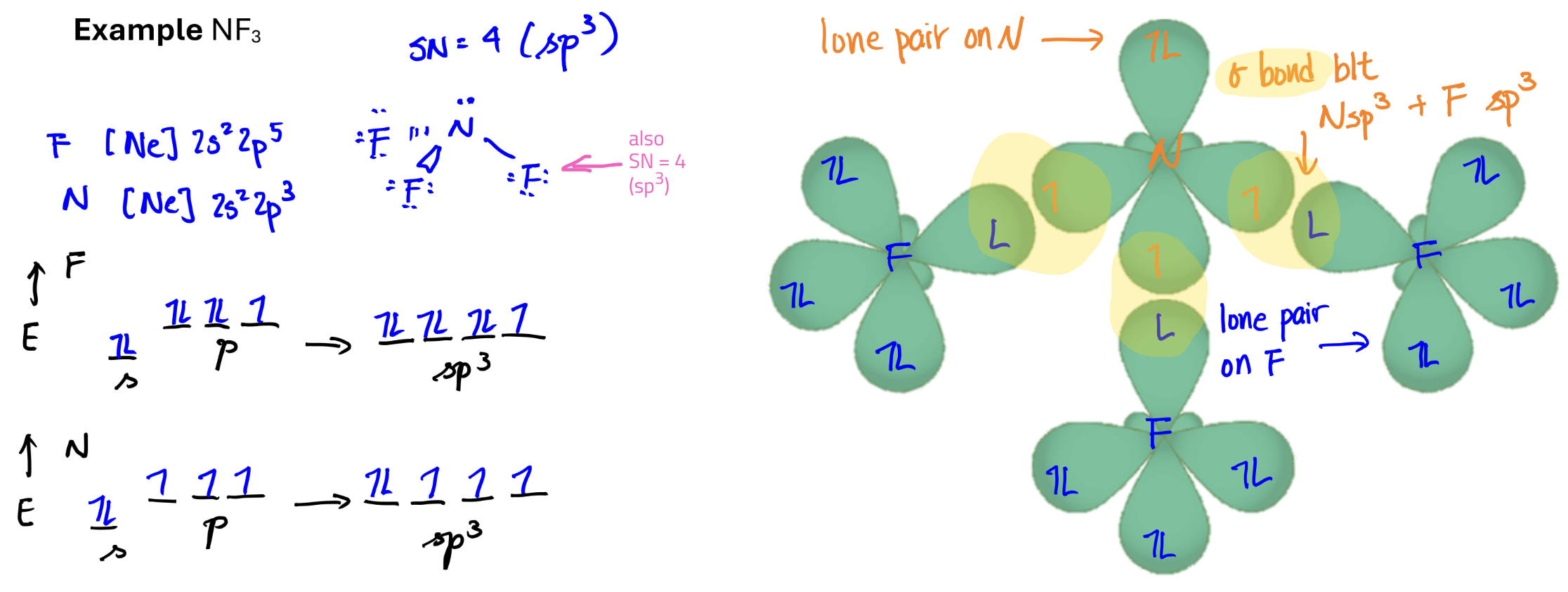

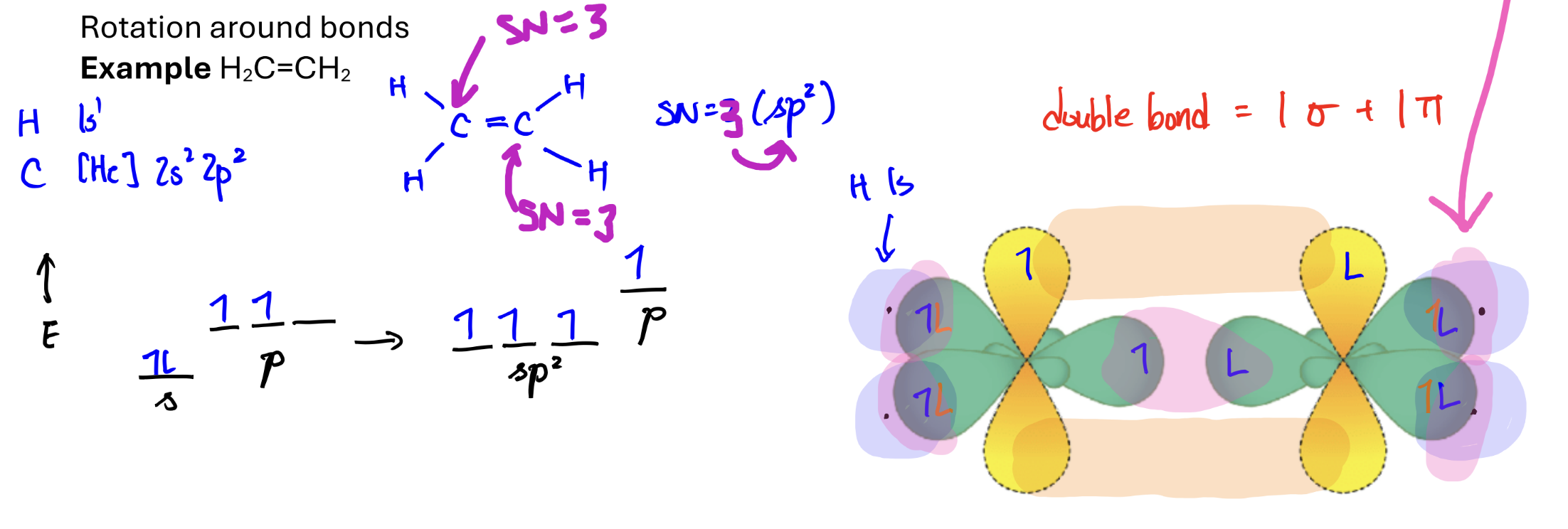

Valence Bond (VB) Theory

how we get bond angles & where are the e- in resonance structures

Hybrid Orbital

combination of s, p, and d orbitals from the same atom

SN = 2

SN = 3

SN = 4

SN = 5

SN = 6

Electron Configuration and Bonding with Hybrid Orbitals

General rule:

Hydrogen atoms do not hybridize and use the 1s orbital to form bonds

All other atoms hybridize to form bonds

the # of orbitals used to combine = the # of hybrid orbitals

σ-bonds

formed by hybrid+hybrid or hybrid+ H 1s

Orbitals overlap end-to-end and electrons are b/w the nuclei

*non-bonding lone pairs are placed in the hybrid orbitals

π-bonds

formed by p orbital + p orbital

Orbitals overlap side-by-side and electrons are above/below the nuclei.

Note: conjugated π system = alternating single and double bonds

σ- and π- bonds in double and triple bonds

double bonds: 1 σ + 1 π

triple bonds: 1 σ + 2 π