2004: DNA Organization, Chromosome Segregation, Mutations and Repair

1/83

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

84 Terms

What are the 2 important reasons for DNA organization?

Accessibility: It allows access to genes in a controlled manner.

Efficiency: It enables the vast lengths of DNA to fit within the confines of a cell.

What are viruses versus bacteriophages?

Virus: a non-cellular infectious particle containing a small nucleic acid genome with a limited number of genes

Bacteriophage: a virus that infects (“eats”) bacteria

In viral DNA packaging, what is a capsid and how do enveloped versus non-enveloped viruses related to this?

Capsid: The viral genetic material is enclosed within a protein coat called a capsid.

Non-enveloped viruses have only this protein shell (capsid).

Enveloped viruses have an additional lipid envelope derived from the host cell membrane surrounding the capsid.

Bacterial chromosomes (ploidy, # of strands and chromosomes)

Bacterial chromosomes are typically single, double-stranded DNA molecules that are highly organized.

Haploid Genomes: Most bacteria have a single chromosome, meaning they have one copy of their genome. Some bacteria, however, possess multiple chromosomes.

How are bacterial chromosomes packaged, and what are the 2 compaction mechanisms?

Nucleoid: Bacterial chromosomes are densely packed into a region called the nucleoid.

Compaction Mechanisms:

Proteins: Small nucleoid-associated proteins help organize the DNA into loops, contributing to its folding and condensation into a nucleoid. Structural Maintenance of Chromosome (SMC) proteins are key players, holding DNA in coiled or V-shaped structures.

Supercoiling: The circular DNA molecule undergoes twisting upon itself, a process called supercoiling. This occurs due to over- or under-rotation of the helical twisting, leading to further compaction. A relaxed circle is the least twisted form.

Eukaryotic chromosomes consist of mainly which elements?

Each chromosome is approximately half DNA and half protein

• About half of the proteins are histone proteins, small basic proteins that tightly bind DNA

What are the types of histone proteins?

There are five main types of histones involved in chromatin structure: H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. These proteins are highly conserved across eukaryotes, highlighting their fundamental importance.

The remaining proteins in chromatin are non-histone proteins, which are diverse and perform various nuclear functions.

Describe the histones in terms of their ratio of amino acid (AA), weight, # of AA, and location

Histone Protein | Ratio of Basic/Acidic Amino Acids | Approximate Molecular Weight (D) | Approx. Amino Acids | Primary Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

H1 | 5.4 | 23,000 | 224 | Linker DNA |

H2A | 1.4 | 13,960 | 129 | Nucleosome |

H2B | 1.7 | 13,774 | 125 | Nucleosome |

H3 | 1.8 | 15,273 | 135 | Nucleosome |

H4 | 2.5 | 11,236 | 102 | Nucleosome |

How are nucleosomes (the basic unit of DNA packaging) formed?

DNA associates with histone proteins to form nucleosomes:

Histone Octamer: A core of eight histone proteins, two each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4—forms the histone octamer.

Core DNA: Approximately 146 base pairs of DNA are wrapped around this histone octamer about 1.65 times.

Linker DNA: In humans, there's a span of about 50 base pairs of DNA between adjacent nucleosomes. This is known as linker DNA.

The wrapping of the DNA during nucleosome formation introduces what?

supercoils into the molecule

How do all histones compact about the sevenfold (gets 7 times smaller) around the octamer in the first level of DNA condensation?

Histones H2A and H2B assemble into dimers.

Histones H3 and H4 also form dimers.

Two (H3-H4) dimers then form a tetramer.

Subsequently, two (H2A-H2B) dimers associate with this tetramer to form the octamer.

How do nucleosomes act as more than just packaging?

The ends (or tails) of the histone proteins extend outwards from the nucleosome core.

These histone tails can undergo various chemical modifications, such as methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation.

These modifications are strongly associated with the regulation of gene expression, influencing whether genes are turned "on" or "off."

Chromatin Structure: 10-nm fiber ("beads-on-a-string")

10-nm fiber ("beads-on-a-string"): Electron micrographs of chromatin in its least condensed state show a "beads-on-a-string" morphology. The "beads" are the nucleosomes, and the "string" between them is the linker DNA. This model of chromatin was proposed by Kornberg in 1974.

Chromatin Structure: How do we go from Nucleosomes to Chromatosomes? How is this more condensed?

Histone H1 and Chromatosomes: The histone protein H1 associates with the linker DNA (between nucleosomes), this is known as a chromatosome.

Condensation: When H1 binds to a nucleosome, it covers an additional ∼20 bp of DNA (bringing the total to ∼166 bp wrapped around the histones, now approximately two full turns).

Chromatin structure: Solenoid/30-nm formation and how it’s stabilized

The 10-nm fiber is typically not found under normal cellular conditions. Instead, a more condensed structure, the 30-nm fiber, is commonly observed.

The 30-nm fiber is formed when the 10-nm fiber coils into a solenoid structure. This solenoid consists of six to eight nucleosomes per turn and is stabilized by the histone H1. This compacts the DNA about six times further than the 10-nm fiber.

Higher-Order Chromatin Organization: what is the 300-nm fiber, how is it formed, and in which state does it usually exist?

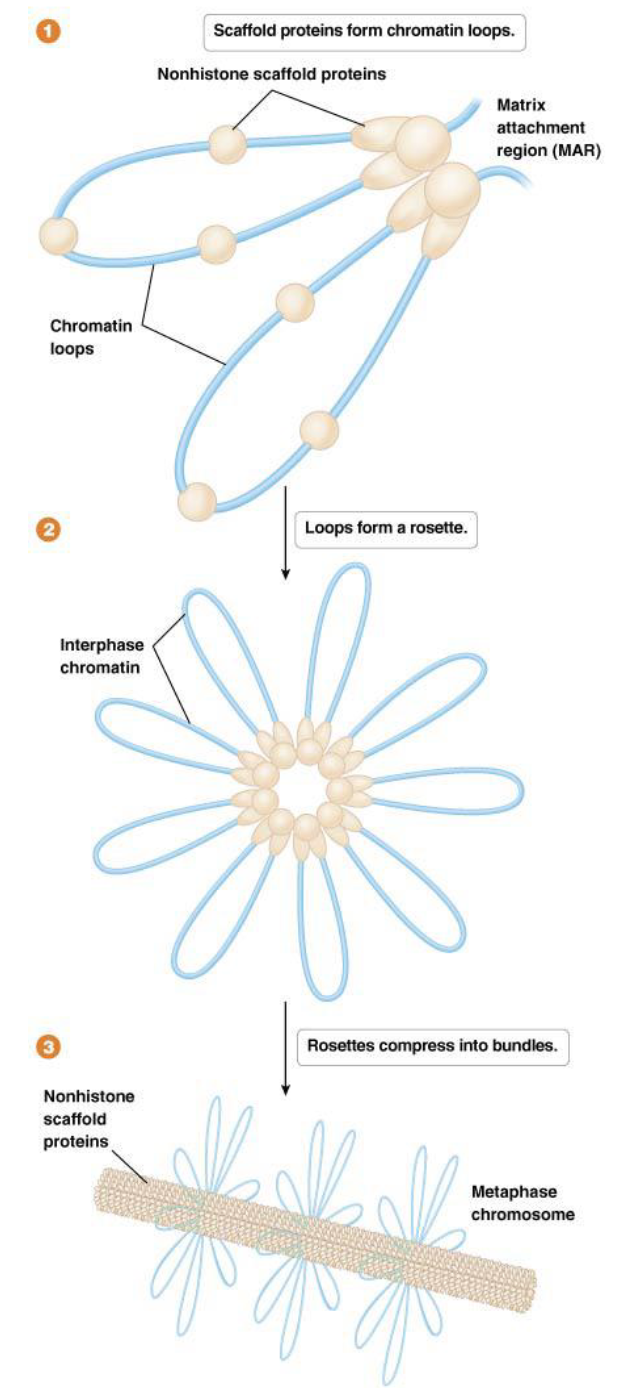

Definition: The solenoidal chromatin is organized into loops. These loops are periodically attached to a central scaffold composed of nonhistone proteins.

Formation: The loops on this scaffold form the 300-nm fiber. This is the state in which chromatin generally exists in a functioning cell during interphase (when the cell is not dividing).

How does the Radial Loop-Scaffold Model help describe how the 300-nm fiber is further compacted to the metaphase chromosome?

This model suggests that the chromatin loops, typically 20 to 100 kb in size, are anchored to the chromosome scaffold at specific sites called MARs (matrix attachment regions) by non-histone proteins. These loops then gather into structures called "rosettes" and are further compressed by non-histone proteins.

Metaphase chromatin formation: compacted 250- fold compared to the 300-nm fiber

What is euchromatin, and is it accessible for gene expression?

These are regions that contain actively expressed genes and are less condensed during interphase.

has an "open structure," making the DNA accessible to enzymes required for processes like transcription.

Expressed genes are primarily found in euchromatin, which often exists in the solenoidal form of chromatin.

What is heterochromatin, is it accessible for gene expression, and where is it usually found?

These are regions that remain condensed throughout interphase and contain fewer expressed genes (often none).

highly compact and transcriptionally inactive.

It is commonly found at the centromeres and telomeres of chromosomes and is frequently associated with the methylation of histones.

Facultative versus Constitutive heterochromatin

Facultative heterochromatin

not always heterochromatin. e.g. the sex chromosomes

exhibits variable levels of condensation, related to levels of transcription of resident genes

Constitutive heterochromatin

permanently condensed,

found prominently in centromeres and telomeres

composed primarily of repetitive DNA sequences

The level of chromatin compaction plays a crucial role in what?

regulating access to DNA by proteins involved in replication, transcription, recombination, or repair.

How does centromeres replicate during the S phase of DNA replication if they are made out of constitutive heterochromatin (always condensed)?

During the S phase of the cell cycle, when chromosomes are replicated, this heterochromatin must temporarily decondense (dissipate) to allow replication.

Nucleosome core particles dissociate from the DNA ahead of the replication fork and then re-form centromeric heterochromatin after the fork has passed. The boundaries for reestablishing centromeres can be variable but usually do not affect gene expression.

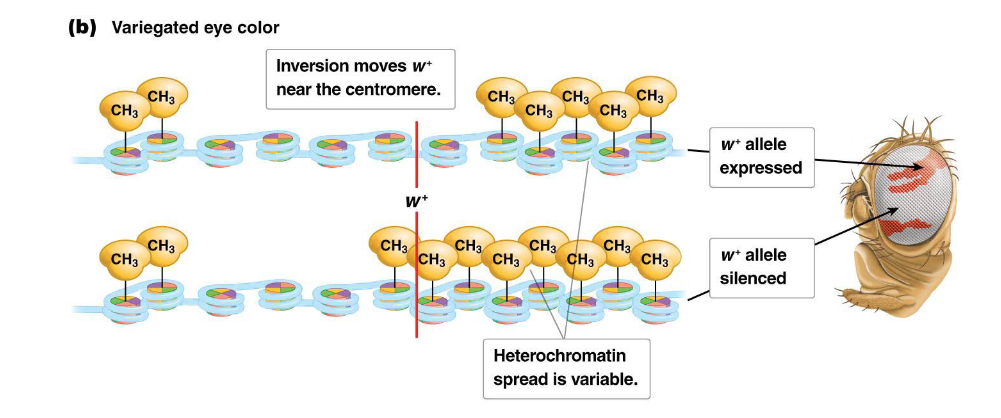

Describe how gene expression or silencing can be dictated by chromatin structure using Drosophila eye color example

Normally, the fruit fly Drosophila has red eyes due to the expression of the w locus, which is typically located in a region of euchromatin near the telomere of the X chromosome.

However, if a chromosomal inversion occurs (e.g., induced by X-rays, as studied by Hermann Müller), the w locus can be moved near the centromere.

In this new location, the spread of heterochromatin from the centromere can extend into the w locus. In some cells, the gene becomes silenced, leading to white patches, while in other cells, it remains expressed, resulting in red patches. This phenomenon gives the fly's eyes a variegated (patchy red and white) appearance, demonstrating how dynamic chromatin structure dictates gene expression.

Germline Cells vs. Somatic Cells

Germline cells (germ cells): These are reproductive cells (sperm and ovum/egg). In humans, germline cells are haploid (n), meaning they contain a single set of 23 chromosomes.

They are involved in sexual reproduction and can pass genetic information to the next generation.

Somatic cells: These are all other body cells (e.g., skeletal and muscle cells, blood cells, stem cells, organ and tissue cells, fat cells, neuron cells). In humans, somatic cells are diploid (2n), meaning they contain two sets of 23 chromosomes, totaling 46 chromosomes.

Somatic cells are responsible for growth, repair, and daily functions of the organism.

Describe the regions of a Chromosome (telomere, short arm, centromere, long arm, sister chromatids)

Telomere: The protective caps at the ends of the chromosome arms.

Short Arm (p-arm): The shorter segment of the chromosome extending from the centromere.

Centromere: A constricted region that holds sister chromatids together and serves as the attachment point for spindle fibers during cell division.

Long Arm (q-arm): The longer segment of the chromosome extending from the centromere.

Sister Chromatids: After DNA replication, a chromosome consists of two identical copies, called sister chromatids, joined at the centromere.

What is chromosome segregation? When does it occur?

a fundamental process in eukaryotes where replicated sister chromatids (or paired homologous chromosomes in meiosis) separate and move to opposite poles of the nucleus. This ensures that each daughter cell receives a complete set of chromosomes.

It occurs during both mitosis and meiosis.

What’s the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic chromosome segregation?

In prokaryotes, replication and segregation are not separated temporally; segregation happens progressively as replication proceeds.

In eukaryotes, replication occurs during interphase, while segregation occurs during mitosis/meiosis

The cell cycle: what is interphase and its stages?

This phase occurs between cell divisions. During interphase, the nucleus has a granular appearance, and crucially, DNA is replicated. Interphase is further divided into three sub-phases:

G1 (Gap 1): Cell grows and carries out normal metabolic functions.

S (Synthesis) phase: DNA replication occurs, where each chromosome duplicates to form two sister chromatids.

G2 (Gap 2): Cell continues to grow and synthesizes proteins necessary for cell division.

The cell cycle: what is the M phase and what does it include?

During this phase, chromosomes are segregated, and the cell divides to form two new daughter cells, which then re-enter interphase. The M phase includes both mitosis (nuclear division) and cytokinesis (cytoplasmic division).

What are homologous chromosomes?

Chromosomes in a homologous pair (homologous chromosomes) are very similar to one another and have the same size and shape.

Most importantly, they carry the same type of genetic information: that is, they have the same genes in the same locations.

Stages of mitosis: prophase

Chromosomes begin to condense, becoming visible under a microscope.

The nucleolus disappears.

Centrioles (within centrosomes) move to opposite poles of the cell.

The mitotic spindle (made of microtubules) begins to form between the centrosomes.

The nuclear membrane breaks down and fragments.

Stages of mitosis: Prometaphase (Late Prophase)

Chromosomes continue to condense.

The nuclear envelope has completely fragmented.

Kinetochore microtubules (a type of spindle fiber) attach to the kinetochores (protein complexes) located at the centromeres of each sister chromatid.

Chromosomes begin to move towards the center of the cell, agitated by the microtubules.

Stages of mitosis: Metaphase

The mitotic spindle formation is complete.

Chromosomes are precisely aligned at the equatorial plane of the cell, known as the metaphase plate. Each sister chromatid faces opposite poles.

Stages of mitosis: Anaphase

Anaphase begins abruptly when the sister chromatids separate.

The now-individual chromosomes (formerly sister chromatids) move towards opposite poles of the cell, pulled by the shortening kinetochore microtubules.

The cell begins to elongate.

A cleavage furrow (an indentation in the cell surface) starts to form, indicating the beginning of cytoplasmic division.

Stages of mitosis: Telophase

Telophase begins when the chromosomes reach the poles of the cell.

New nuclear membranes re-form around the separated sets of chromosomes at each pole.

Chromosomes begin to decondense (uncoil).

Nucleoli re-form.

The spindle fibers disappear.

The cleavage furrow continues to deepen.

What occurs during cytokinesis? Does it always follow mitosis?

Cytokinesis is the division of the cytoplasm, distinct from mitosis (nuclear division), but typically follows closely after it.

It involves the completion of the cleavage furrow, which eventually pinches the cell into two distinct daughter cells.

Cytokinesis doesn't always immediately follow mitosis (e.g., in Drosophila development, multiple nuclear divisions can occur before cytoplasmic division).

What is the difference between meiosis I and meiosis II?

Meiosis I (Reduction Division):

This is the first meiotic division.

Homologous chromosomes separate. This is the reductional step, meaning the chromosome number is halved.

It produces two haploid daughter cells (n), each containing chromosomes that still consist of two sister chromatids (double-stranded chromosomes).

Meiosis II (Equational Division):

This is the second meiotic division.

Sister chromatids separate. This division is equational, similar to mitosis, as the number of chromosomes (single chromatids) per cell remains the same as in the cells produced by Meiosis I.

It produces four haploid gametes (n), each containing single-stranded chromosomes (a single chromatid).

Stages of meiosis I: Prophase I - Leptotene

Chromosomes begin to condense and become visible.

Thickened regions called chromomeres appear along the chromosomes.

The nuclear envelope is intact, centrosomes move to poles, and asters form.

Stages of meiosis I: Prophase I - Zygotene

Chromosomes continue to condense.

Homologous chromosomes (bivalent) come into close contact and begin to pair in a process called synapsis. This initiates the formation of the synaptonemal complex, a protein bridge that tightly binds non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes together.

Stages of meiosis I: Prophase I - Pachytene

Chromosomes become fully aligned.

Within the central element of the synaptonemal complex, new structures called recombination nodules appear. These nodules play a pivotal role in crossing over (recombination) of genetic material between non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes.

Stages of meiosis I: Prophase I - Diplotene

Homologous chromosomes start to pull apart slightly, but they remain attached at points where crossing over has occurred.

These visible contact points are called chiasmata (singular: chiasma).

The paired homologous chromosomes, now visible as four chromatids, are called a tetrad.

Stages of meiosis I: Prophase I - Diakinesis

compaction is completed and the chromosomes are ready to be segregated

Stages of meiosis I: Metaphase I

Homologous pairs of chromosomes (bivalents or tetrads) align at the metaphase plate. Importantly, each homologous chromosome faces opposite poles.

Stages of meiosis I: Anaphase I

Homologous chromosomes separate and move towards opposite poles of the cell.

Sister chromatids remain attached at their centromeres. This is the key difference from anaphase of mitosis.

The cell begins to elongate.

Stages of meiosis I: Telophase I and Cytokinesis

Chromosomes reach the poles.

New nuclear membranes may re-form around the separated homologous chromosomes (though sometimes the cell proceeds directly to Meiosis II without full nuclear re-formation).

The cytoplasm divides (cytokinesis), resulting in two haploid cells. Each cell now contains a haploid set of chromosomes, but each chromosome still consists of two sister chromatids.

What are the stages of meiosis II?

Second division (Meiosis II) is a typical mitosis-like division

Prophase = chromosome condensation

Metaphase = chromosome alignment

Anaphase = sister chromatid separation/movement to ends

Telophase = reformation of nuclei

Cytokinesis divides the cytoplasm, resulting in a total of four haploid daughter cells. Each of these gametes contains a single set of unreplicated chromosomes (single chromatids).

Explain the importance of meiosis in terms of the production of haploid gametes + examples

This is critical for sexual reproduction, as it ensures that when two gametes fuse during fertilization, the resulting zygote has the correct diploid number of chromosomes.

Failure of proper chromosome segregation (called nondisjunction) can lead to gametes with an incorrect number of chromosomes, a condition known as aneuploidy. A classic example is Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), where an individual has three copies of chromosome 21 instead of two.

Explain the importance of meiosis in terms of the 2 ways to increase genetic diversity

Independent assortment of chromosomes during Meiosis I creates a vast number of possible combinations of chromosomes in the gametes. For humans with 23 pairs of chromosomes, there are 2^23 (over 8 million) possible combinations of chromosomes that can be found in a single gamete, just from independent assortment alone.

Recombination (crossing over) further increases diversity by reshuffling genetic information within chromosomes, exchanging segments between homologous non-sister chromatids.

What is DNA recombination? This exchange can occur between what?

DNA recombination is a molecular phenomenon involving the exchange of DNA fragments (genetic material). Tightly regulated process, but still stochastic (random) in certain aspects, which can lead to disease.

This exchange can occur between:

Multiple chromosomes (both homologous and non-homologous).

Different regions of the same chromosome.

Intraspecific vs Interspecific diversity

Intraspecific diversity: variability of genomic sequences between populations of a single species

Interspecific diversity: variability of genomic sequences between different species

What is crossing over in DNA recombination?

a specific type of DNA recombination that occurs during meiosis.

It involves the breakage and reunion of DNA fragments between non-sister chromatids of aligned homologous chromosomes, resulting in reciprocal exchange of genetic material.

This process is a vital component of accurate chromosome segregation in mammalian meiosis.

When and in what way does crossing over occur during the stages of meiosis?

During prophase I, particularly during this 3 phases:

Zygotene: Homologous chromosomes come into close contact and align in a process called synapsis. This initiates the formation of the synaptonemal complex, a trilayer protein structure that tightly binds non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes, maintaining synapsis.

Pachytene: Within the central element of the synaptonemal complex, recombination nodules appear. These nodules are crucial for the crossing over of genetic material between non-sister chromatids.

Diplotene: The synaptonemal complex begins to dissolve. Homologous chromosomes pull apart slightly, revealing points of contact called chiasmata. These chiasmata physically mark the locations where crossing over has occurred.

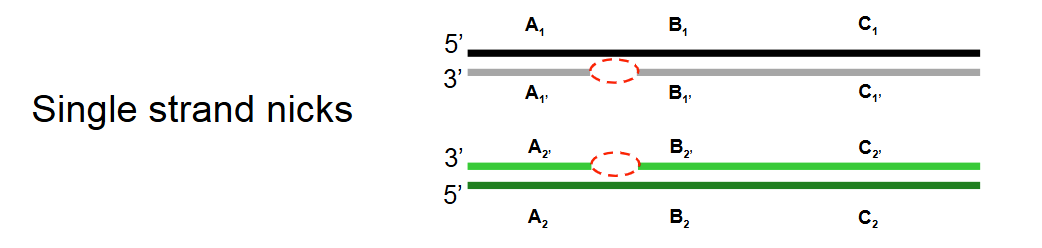

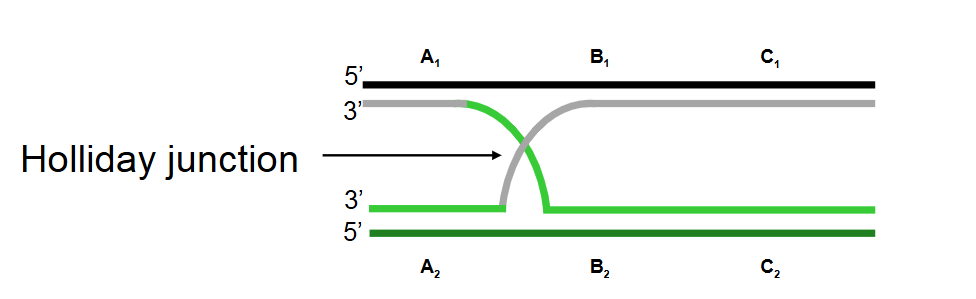

Describe step 1 of the Holliday model of DNA recombination

Single-strand nicks: Identical single-strand nicks (breaks) form on both homologous DNA duplexes.

Describe step 2 of the Holliday model of DNA recombination

Strand invasion: The nicked strands invade the opposite homologous duplexes. Base pairs form between the two recombining DNA duplexes.

Since the sequences are identical or nearly identical, each nicked strand can base pair with the uncleaved strand on the opposite duplex, forming a Holliday junction.

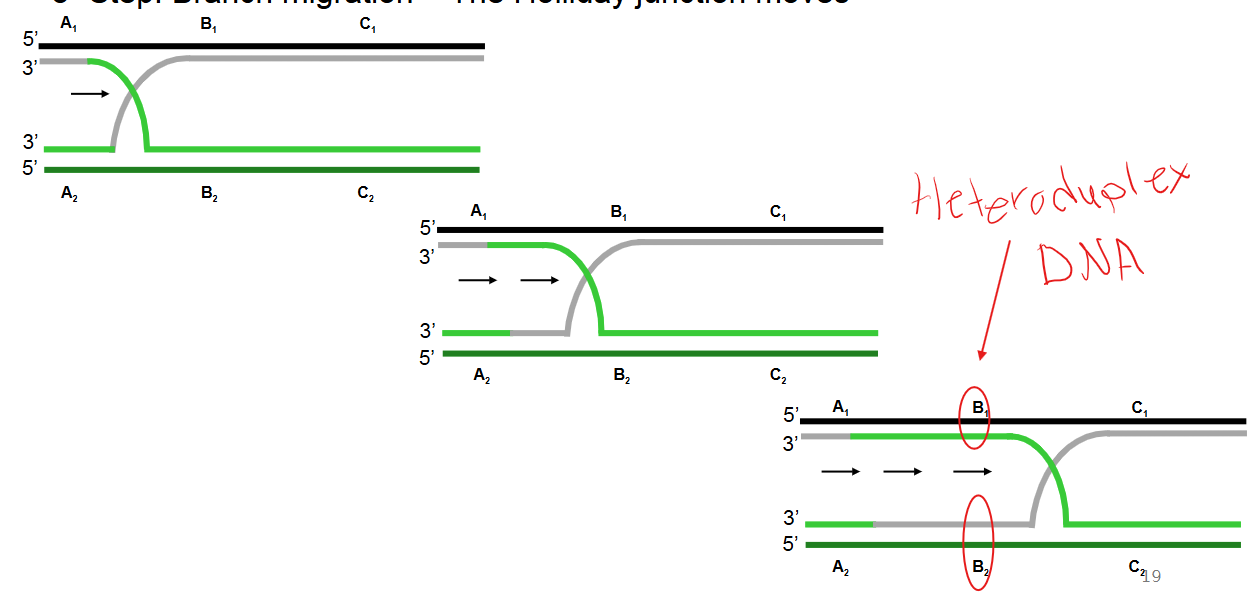

Describe step 3 of the Holliday model of DNA recombination

Branch migration: The Holliday junction moves along the DNA, extending the region of exchanged strands.

This process generates a heteroduplex DNA region (also known as a heteroduplex region), which is a duplex formed by combining complementary strands from non-sister chromatids. A mismatch within this region is called a heteroduplex mismatch.

Describe step 4 of the Holliday model of DNA recombination

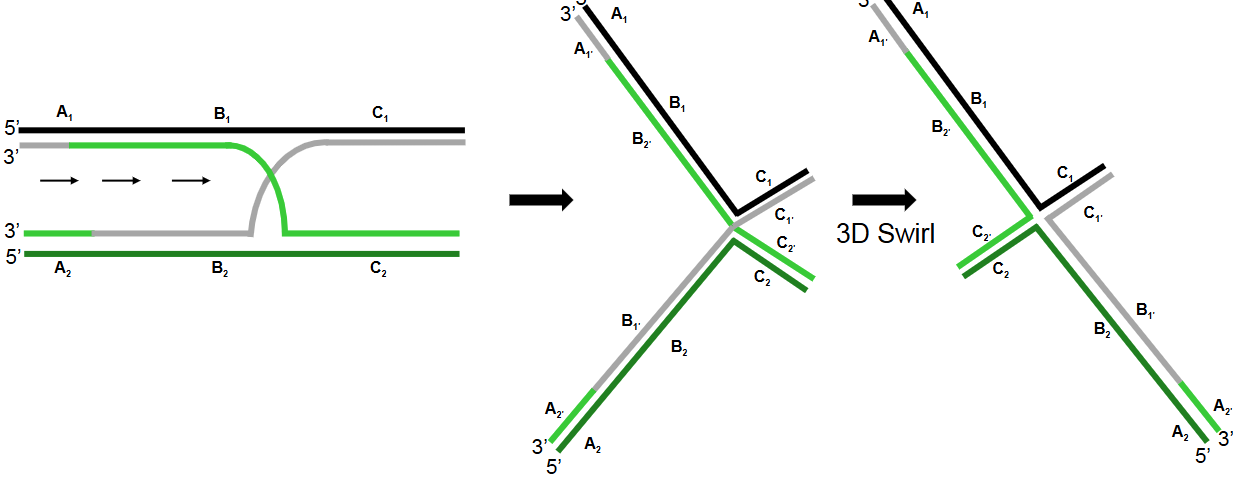

Cleavage of the Holliday junction: The Holliday junction is cleaved, regenerating two separate DNA duplexes. There are two possible orientations for cleavage.

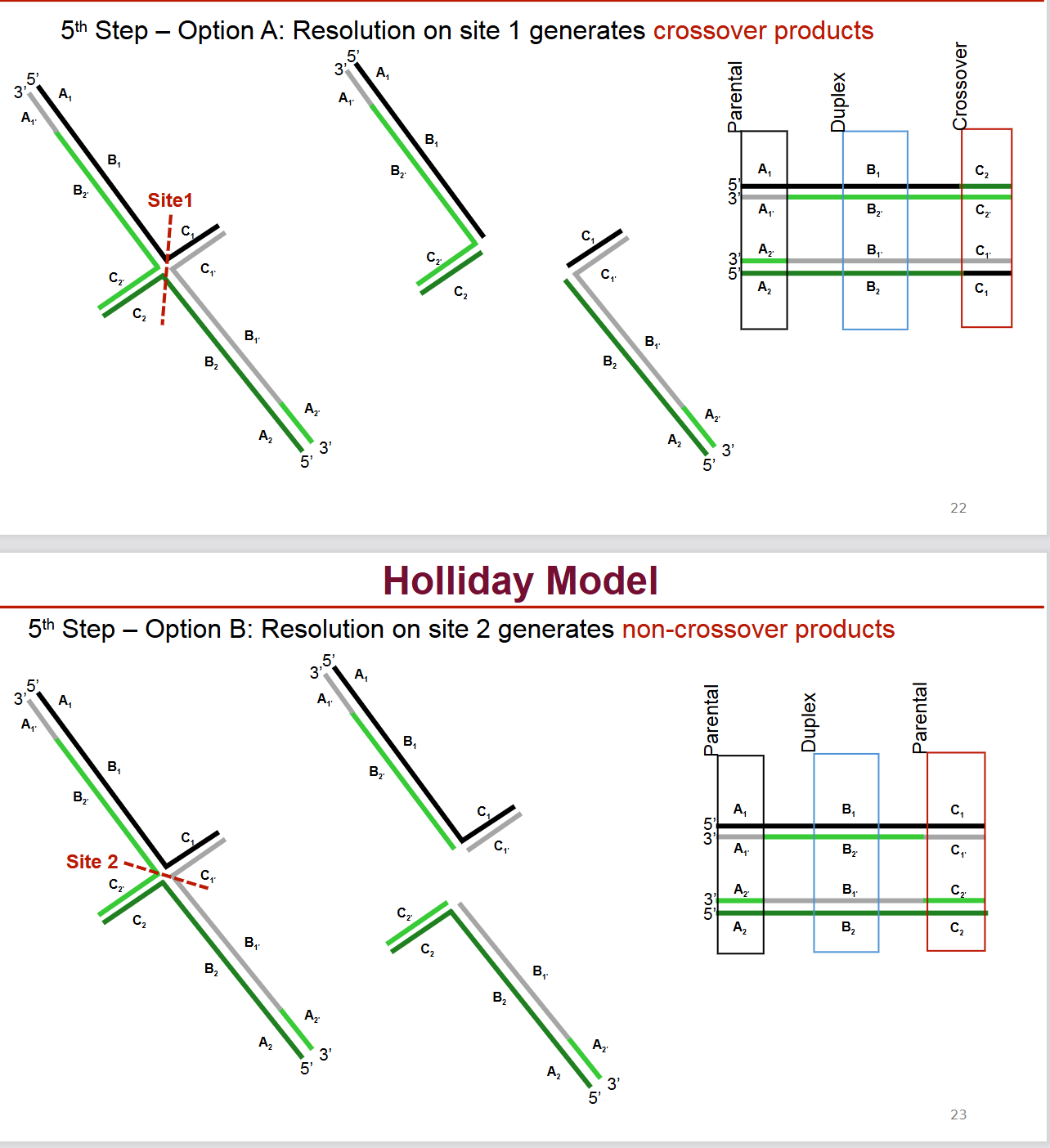

Describe step 5 of the Holliday model of DNA recombination

Resolution:

Option A (Resolution on site 1): Cleavage in one orientation followed by ligation generates crossover products, where the flanking regions of the DNA have been exchanged.

Option B (Resolution on site 2): Cleavage in the other orientation followed by ligation generates non-crossover products, where the flanking regions remain in their original configurations, but the central heteroduplex region still shows exchange.

What is the difference between the Holliday model and the updated current model of DNA recombination?

Holliday model was too simplistic.

Major updates in the current model include:

Meiotic recombination is initiated by double-stranded DNA breaks, not single-strand nicks.

It occurs in a programmed manner, facilitated by the activity of specialized enzymes.

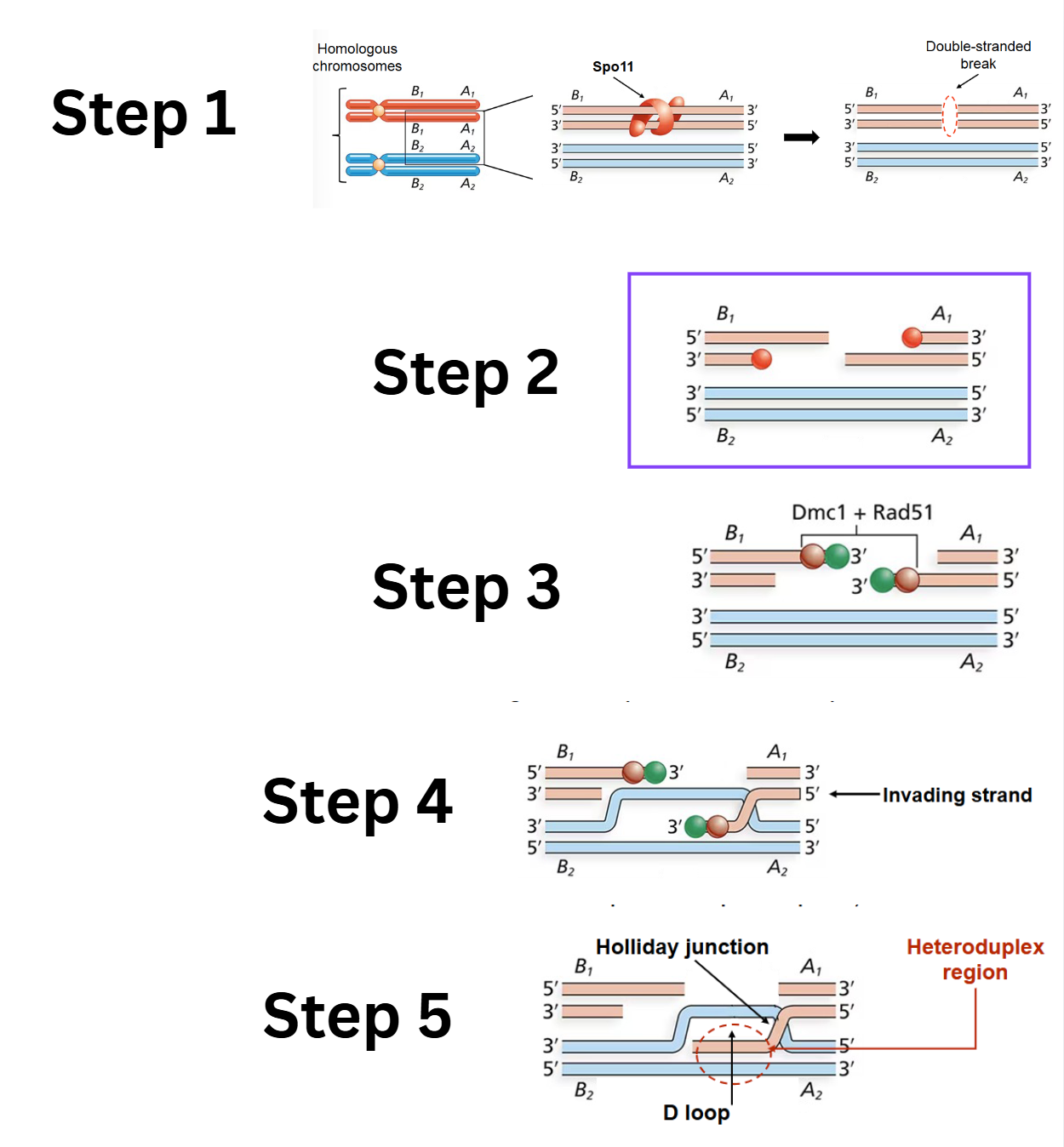

What are the first 5 steps of the Double-Stranded Break Model

Double-stranded break (DSB): An enzyme called Spo11 creates a double-stranded break in one of the DNA duplexes.

Digestion of cut strands: The Mrx complex and Exo1 enzyme associate with Spo11 and digest the 5' ends of the cut strands, creating 3' single-stranded overhangs.

Strand-exchange nucleoprotein filaments: Dmc1 and Rad51 proteins bind to the trimmed single-stranded regions and assemble into strand-exchange nucleoprotein filaments.

Strand invasion: The strand-exchange nucleoprotein filaments promote strand invasion

D-loop and first heteroduplex region: Strand invasion creates a D-loop (displacement loop) and the first heteroduplex region. (Rad52, Rad59, and other proteins participate in this step). This also forms the first Holliday junction.

What are steps 6-9 of the Double-Stranded Break Model

Strand extension and second heteroduplex region: DNA polymerase extends the invading strand, displacing the D-loop DNA. This D-loop DNA then pairs with the complementary single-stranded DNA from the broken chromosome to form the second heteroduplex region.

Gap filling and ligation: DNA polymerase extends the other 3' overhang (paired with the D-loop DNA), and ligation fills the single-stranded gaps.

Double Holliday junctions: After the nicks are sealed, two Holliday junctions are formed, resulting in a structure with offset heteroduplexes on both chromatids.

Resolution of double Holliday junctions:

Option A (Opposite-sense resolution): Cleavage and ligation of the two Holliday junctions in an "opposite-sense" manner results in only crossover products, where the flanking regions have been exchanged.

Option B (Same-sense resolution): Cleavage and ligation of the two Holliday junctions in a "same-sense" manner results in non-crossover products, where the flanking regions remain unchanged, but the central heteroduplex regions show gene conversion.

Errors in Recombination (Crossing Over): explain the unequal Crossing Over of Homologous Chromosomes and consequences

Unequal crossing over occurs when homologous chromosomes misalign during synapsis in meiosis I, and crossing over happens between these mispaired regions. This improper synaptic pairing leads to a skewed exchange of genetic material.

Consequences: It results in chromosome mutations where segments of chromosomes are either:

Duplicated (partial duplication): One chromosome gains an extra copy of certain genes.

Deleted (partial deletion): The homologous chromosome loses those genes.

Errors in Recombination (Crossing Over): explain the inversion of chromosomes and how it most commonly occurs

Chromosome inversions result from two breaks in a chromosome, followed by the reattachment of the free segment in the reverse orientation (flipped 180 degrees).

Most commonly, inversion affects only one member of a homologous pair of chromosomes, creating an inversion heterozygote.

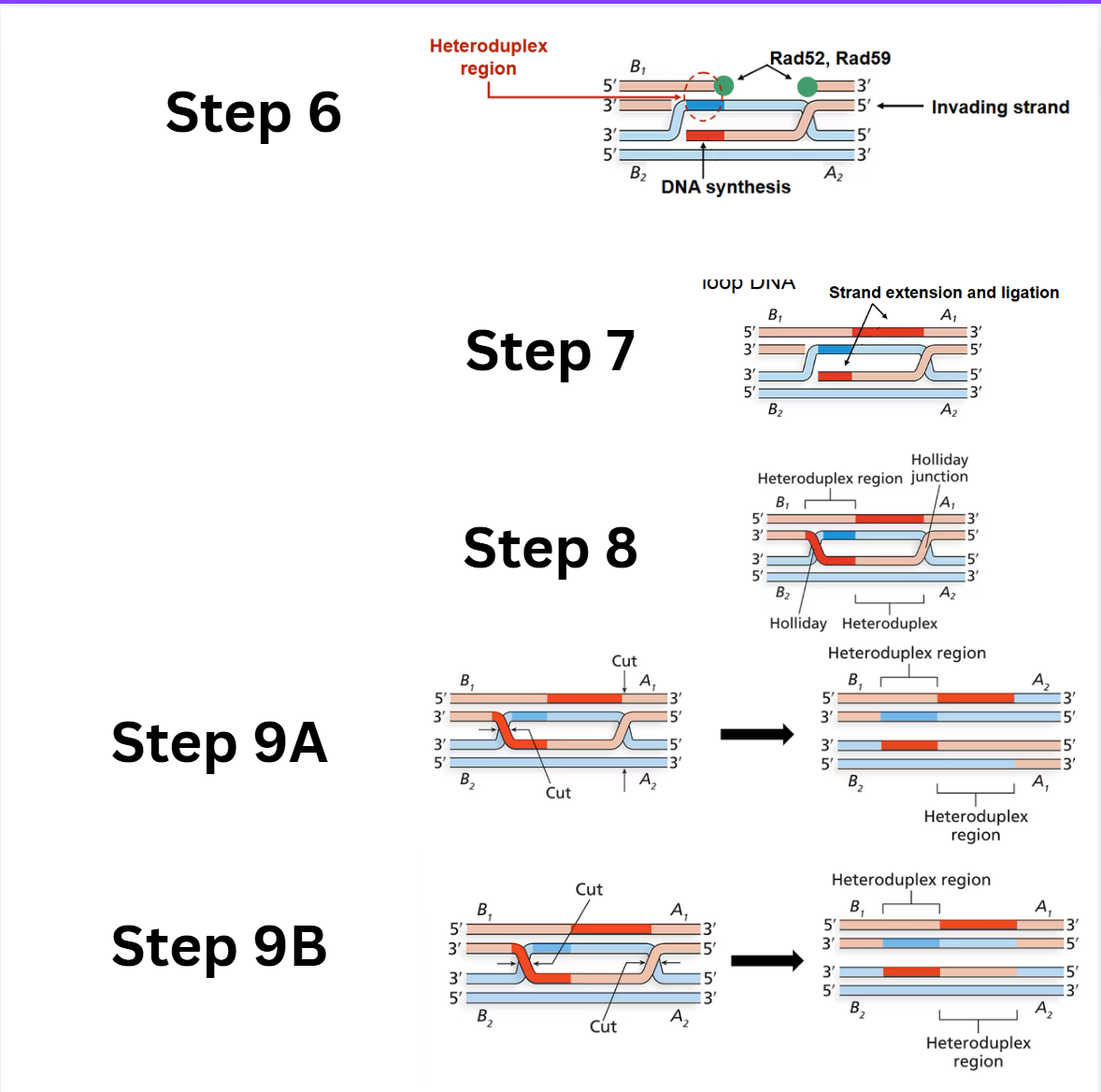

Paracentric inversion versus Pericentric inversion

Paracentric inversion: The inverted segment is located on a single arm of the chromosome and does not include the centromere.

Pericentric inversion: The inverted segment includes the centromere, meaning the breakpoints are on opposite arms of the chromosome. This reorients a segment that spans both arms.

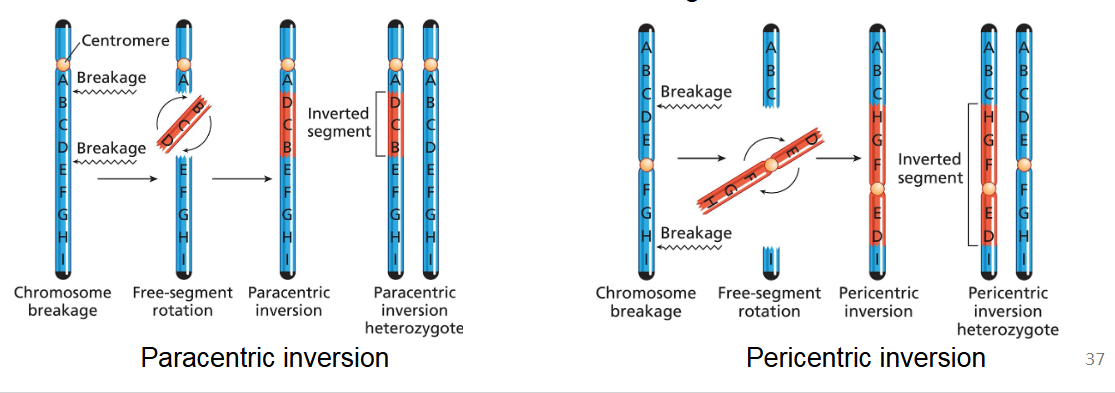

How does a pericentric inversion affect synapsis between chromosomes? What does this issue form in the chromosomes? Give a local example

In an inversion heterozygote, the difference in gene order due to the inversion requires a special structural adjustment for proper synaptic alignment during meiosis I.

This adjustment involves the formation of an inversion loop. Chromosomes are flexible enough to form these structures without breakage, allowing homologous regions to pair up.

Example: Allderdice Syndrome: This syndrome is associated with a pericentric inversion on chromosome 3, identified in Sandy Point, Newfoundland. The discovery was linked to Dr. Penny Allderdice.

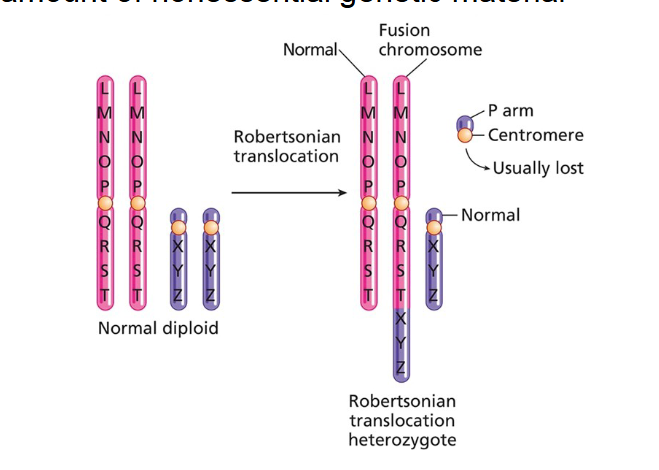

Errors in Recombination (Crossing Over): explain the 3 types of non-homologous crossing Over (Translocation)

Reciprocal balanced translocation: This involves an exchange of chromosome segments between two non-homologous chromosomes where no genetic material is lost or gained. The individual has all the correct genetic material, just rearranged.

Reciprocal unbalanced translocation: This occurs when genetic material is lost or gained during the exchange of chromosome segments between non-homologous chromosomes.

Robertsonian translocation (chromosome fusion): This is a specific type of translocation that involves the fusion of two non-homologous chromosomes. Often, a small amount of nonessential genetic material (from the short arms) is deleted during this fusion.

Example: Robertsonian translocations are known to cause genetic disorders like Patau syndrome (Trisomy 13).

What’s the key differences in diseases in unbalanced versus balanced translocation?

Balanced translocations usually do no cause disease (you have all the correct genetic material).

Balance translocation can cause problems with homologous chromosomes lining up on the metaphase palate- can cause fertility issues and miscarriages.

Inheriting an unbalanced translocation can cause disease, because you may have copy number variation of some genes ( 1 or 3 copies) instead of two

What are mutations and its 2 main characteristics? Why are they indespensible?

A mutation is a heritable change that alters the DNA sequence of a cell. Mutations possess two main characteristics:

Randomness: Mutations occur by chance; each base pair theoretically has an equal probability of mutating.

Rarity: The average mutation rates are very low.

Indispensable: They generate new hereditary variants. These new variants can influence the evolution of a species. They have several impacts on the fitness of an organisms

Classification 1 of mutations: explain the two types of mutations by cell type

Germ-Line mutations: These occur in germ-line cells (cells that give rise to sperm and egg). They are particularly significant because they can be passed from one generation to the next, affecting offspring.

Somatic mutations: These occur in any of the body's cells that are not in the germ line (somatic cells). Somatic mutations can be passed to subsequent generations of cells within a cell lineage through mitotic cell division. However, only the direct descendants of the original mutated cell will carry the mutation, and it is generally not inherited by offspring.

Explain point mutations and what their consequences depend on

A point mutation is a type of gene mutation where one or more DNA base pairs are substituted, added, or deleted at a specific location within a gene.

They are the most common type of gene mutation and have varied consequences depending on their location.

Classification 2 of mutations: explain the two types of mutations by location in the gene

Coding-sequence mutations: occur in the coding sequence of a gene and can lead to changes in the amino acid composition of the protein product of the gene

Regulatory mutation: occur in a regulatory sequence of a gene and can alter the amount of wild-type protein product produced by the gene

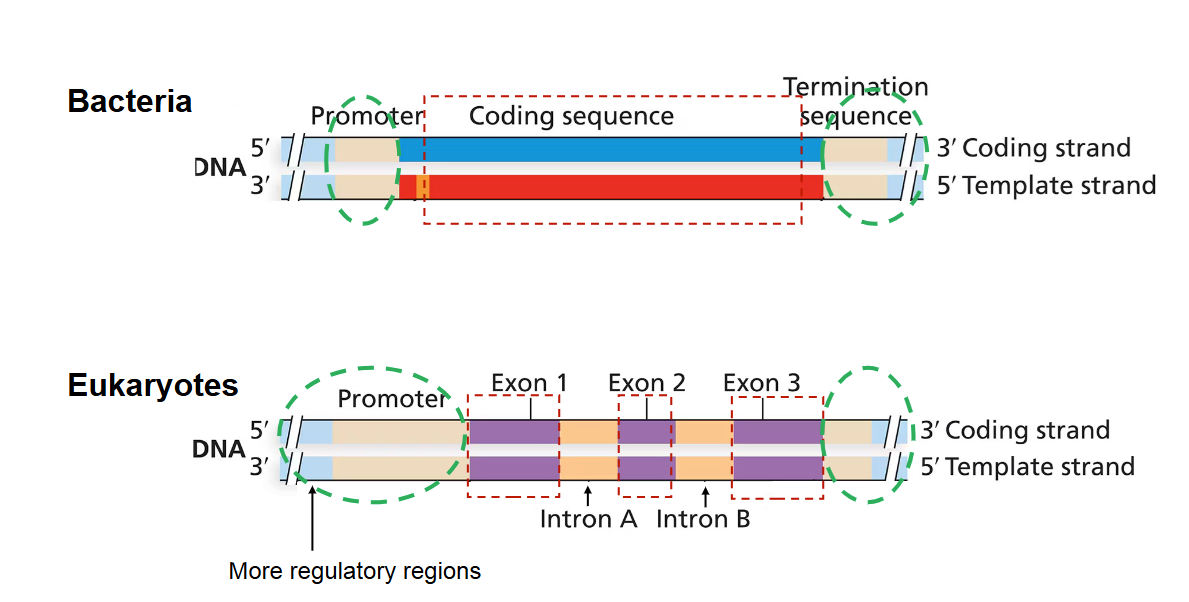

bacterial vs eukaryotic location of point mutations

In bacteria, the genome is relatively simple. Point mutations can only occur in their one coding sequence

In eukaryotes, there are more regulatory regions in the genome, meaning point mutations can occur in both coding and non-coding (regulatory) sequences.

Classification 3 of mutations: explain the two types of mutations by type of mutation (base-pair, indel)

Base-pair substitution mutation: The replacement of one nucleotide base pair by another.

Transition mutations: A purine is replaced by the other purine (A → G; G → A), or a pyrimidine is replaced by the other pyrimidine (C → T; T → C).

Transversion mutations: A purine is replaced by a pyrimidine (A → T; A → C; G → T; G → C), or a pyrimidine is replaced by a purine (T → A; T → G; C → A; C → G).

Indel mutations: The insertion or deletion of one or more base pairs.

Classification 4 of mutations: explain what is mutations by Effect (Impact on Protein)

These classifications describe how a mutation affects the protein's structure, function, or amount. The Central Dogma of molecular biology (DNA → RNA → Protein) illustrates where these effects occur.

Classification 4 of mutations: what are the 4 Coding-Sequence Mutations (Base-pair substitution or Indel):

Synonymous mutations (silent mutation): A base-pair substitution that produces an mRNA codon specifying the same amino acid as the wild-type mRNA (naturally occurring version of a gene). Because the genetic code is redundant, these mutations often have no effect on the protein sequence.

Missense mutations: A base-pair substitution that results in a change to a different amino acid in the protein.

Example: Sickle cell anemia is caused by a missense mutation where a single nucleotide change in the β-globin gene leads to the substitution of valine for glutamic acid.

Nonsense mutations: A base-pair substitution that creates a stop codon in place of a codon specifying an amino acid. This leads to premature termination of translation and a truncated protein.

Frameshift mutations: An insertion or deletion (indel) of base pairs (not in multiples of three) that alters the reading frame of the codon sequence.

This can drastically change the amino acid sequence from the point of mutation to the end of the polypeptide.

It can also generate premature stop codons, leading to truncated or degraded transcripts.

Classification 4 of mutations: what are the 4 Regulatory Mutations (Could be substitution or indel):

Promoter mutations: alter consensus sequence nucleotides and interfere with efficient transcription initiation

Splicing mutations: Mutations of nearby nucleotides in the consensus sequence within an intron can cause errors in the removal of intron sequences from pre-mRNA. Some mutations create cryptic splice sites that compete with or replace authentic splice sites.

Polyadenylation mutations: Mutations in the polyadenylation signal sequence (e.g., 5'-AATAAA-3') can block proper processing of mRNA, leading to abnormal mRNA and a severe reduction in functional protein.

Repeat expansion mutations: Caused by increases (or decreases) in the number of short DNA repeats. These expansions can disrupt gene function.

Example: In Huntington's disease, the HD gene normally has a variable number of CAG repeats. If the number of CAG repeats exceeds 34, it leads to an unstable huntingtin protein and the disease.

What are Missense “gain-of-function” Mutations and its 3 types?

Gain-of-function mutation: Results in a gene product with new or enhanced activity.

Hypermorphic mutation: Leads to more gene activity than normal.

Neomorphic mutation: Results in a new gene activity not associated with the normal gene.

Antimorphic mutation (dominant negative effect): The mutant gene product acts in opposition to normal gene activity, often by interfering with the function of the wild-type protein in a multimeric complex.

What are Missense “loss-of-function” Mutations and its 2 types?

Loss-of-function mutation: Results in a significant decrease or complete loss of the functional activity of a gene product.

Amorphic mutation (null mutation): Leads to a complete loss of gene function.

Hypomorphic mutation (leaky mutation): Results in a partial loss of gene function.

What are the two types of mutation causations?

Spontaneous mutations: naturally occurring mutations that arise through:

DNA replication errors

Spontaneous changes in the chemical structure of nucleotide bases

Caused by agents: produced by interactions between DNA and:

Chemical mutagens

Ionizing radiation

What are the 2 spontaneous causes of mutations from DNA replication errors?

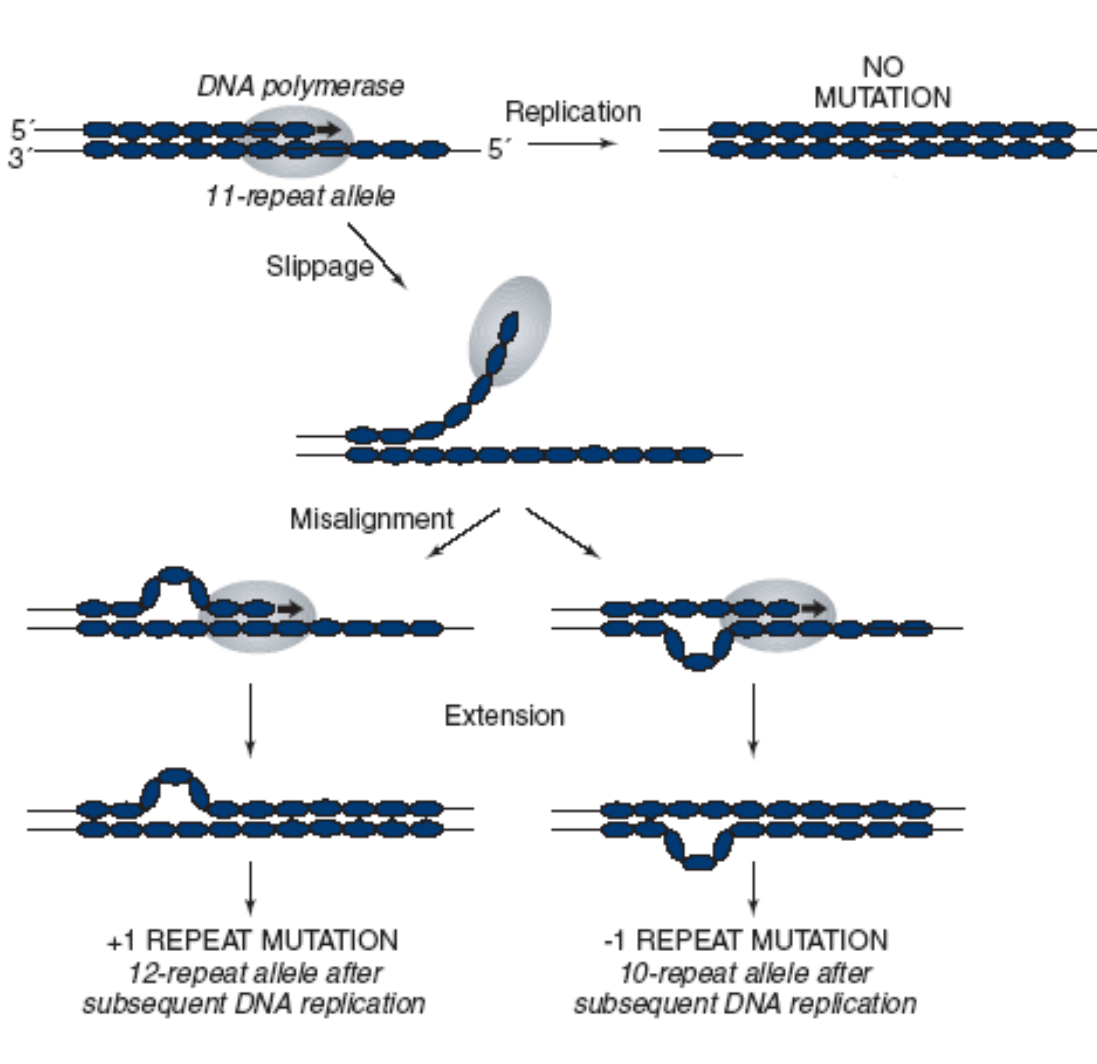

Insertion and deletion of nucleotide repeats by strand slippage: During DNA replication, either the template strand or the newly synthesized strand can "slip" at regions containing short tandem repeats. This slippage can lead to an increase or decrease in the number of repeats, causing an insertion or deletion mutation (e.g., trinucleotide repeat expansion mutations).

Mispaired Nucleotides: Non-complementary bases can pair during DNA replication due to unusual base conformations (e.g., non-Watson-and-Crick base pairing or "third-base wobble," where G pairs with T or C with A, typically with two hydrogen bonds).

If not corrected, this incorporated error leads to a mutation in the next replication round.

What are the 2 spontaneous causes of mutations from changes in the chemical structure of nucleotide bases?

Depurination: The loss of one of the purines (adenine or guanine) from a nucleotide due to the breakage of the covalent bond linking the sugar to the base.

This forms an apurinic (AP) site/DNA lesion. If unrepaired, DNA polymerase often inserts an adenine opposite the AP site during replication. If this insertion is incorrect, it leads to a base substitution mutation.

Deamination: The loss of an amino (NH2) group from a nucleotide base. Deamination of methylated cytosine is particularly prone to mutation, as it creates thymine. This results in a T-G base-pair mismatch. If mismatch repair does not correct it, the next round of replication will lead to a C-G to T-A base-pair substitution.

What are mutagens?

Mutagens are chemical compounds that induce mutations

Mutations caused by agents: Describe the mutagens Nucleotide base analogs and Deaminating agents with an example

Nucleotide base analogs: Chemicals with structures similar to normal DNA bases that can be incorporated into DNA during replication.

Example: 5-bromodeoxyuracil (BrdU) is an analog of thymine. It can mispair with guanine, leading to A-T to G-C or G-C to A-T transition mutations.

Deaminating agents: Agents that remove an amino group from a nucleotide base.

Example: Nitrous acid (HNO2), derived from sodium nitrate (a food preservative), can deaminate cytosine to uracil, leading to C-G to T-A transitions.

Mutations caused by agents: Describe the mutagens Alkylating agents, Hydroxylating agents, DNA Intercalating agents with an example

Alkylating agents: Agents that add bulky side groups (e.g., methyl (CH3) or ethyl (CH3-CH2) groups) to nucleotide bases.

Example: Ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) is an alkylating agent that can mutagenize guanine, leading to mispairing and G-C to A-T transitions.

Hydroxylating agents: Agents that add a hydroxyl (OH) group to nucleotide bases.

Example: Hydroxylamine (used in nylon synthesis) specifically hydroxylates cytosine, causing it to pair with adenine, leading to C-G to T-A transitions.

DNA Intercalating agents: Small molecular compounds that insert themselves between the base pairs of DNA. This insertion distorts the DNA structure and typically leads to INDEL mutations (insertions or deletions) during replication.

Example: Benzo[a]pyrene, a component of cigarette smoke, is a known intercalating agent.

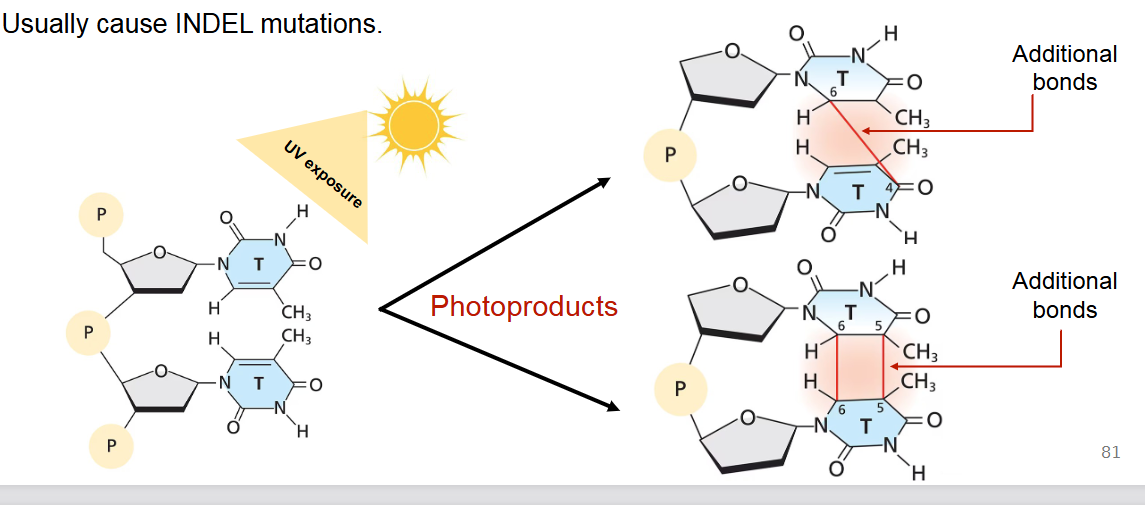

Mutations caused by agents: Describe Ionizing radiation and how it can cause mutations (primarily UV radiation)

Ionizing radiation is when all forms of energy above the visible spectrum (ultraviolet (UV) radiation, X-irradiation, gamma rays, and cosmic rays) are mutagenic.

UV radiation: A significant concern as it's a component of sunlight. UV exposure primarily causes the formation of photoproducts, such as thymine dimers (additional bonds between adjacent pyrimidines on the same DNA strand), leading to kinks in the DNA and errors during replication.

UV radiation usually causes INDEL mutations or base substitutions if not repaired.