genomics - dna binding proteins and motif analysis

1/33

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

34 Terms

jacob & monod

repressors encoded in lac operon regulate rate of protein synthesis

protein-dna interaction sequence specificity

-there is no universal code

-electrostatics, hydrogen bonds, water-mediated contacts, and hydrophobic packing

-sequence-specific DNA deformations (indirect readout)

-requires the determinaiton of binding preferences for many members of a family of TFs

Sequence motif

-subsequence with some specific function

-may be in DNA, RNA, protein

-function many be context dependent: ribosome binding site has to be transcribed

-may be gapped or ungapped

Consensus sequence pattern

-may include degenerate bases and allow for mismatches

-search space is over possible patterns

-difficult to obtain an optimal consensus for identifying novel sites

-relative frequency of bases at each positions lost

weight matrix

might go to higher order models

search space is over possible alignments

-more information than a consensus sequence

-many ways to determine the weights

-assumes positional independence

-requires significant data

pattern based algorithms

-can use motif length, num of mismatches, num of seqs,

-4^l patterns, search for most common or significant

N(b,j)

raw scores for a weight matrix model, ie number of times each base showed up in each position

b = base (A, C, T, G), row index

j = jth position in a sequence, column index

F(b,j)

weighted scores for weight matrix model

take raw scores in each position, and get decimal number for likelihood of each base in each position (total should equal 1 in each column)

S(b,j)

probability-normalized log score in weight matrix model

log2[F(b,j)/P(b)]

P(b) = background base distribution

Information content

Sum over columns j and rows b to distinguish divergence of the empirical distribution (f(b,j)) from the background base distribution (p(b))

aka relative entropy, kullback-leibler distance

pseudocounts

entries of 0 in the count matrix cause problems because log(0) is undefined

There’s not enough observations to observe all possibilities

Can add pseudocounts to the matrix to ensure there’s no 0s

protein binding microarrays

can be used for defining PWM

-custom arrays of 60-mer DNA sequences (~44,000 probes)

-contain all possible 10 bp sequences

-each probe contains 27 10-mers

-8-mers guaranteed to occur 16 times

ChIP-seq

-can be used for defining PWM

-cross link protein to DNA

-affinity purify protein-DNA complexes

-reverse cross-links

-identify sequence by hybridization to microarray or by high throughput sequencing

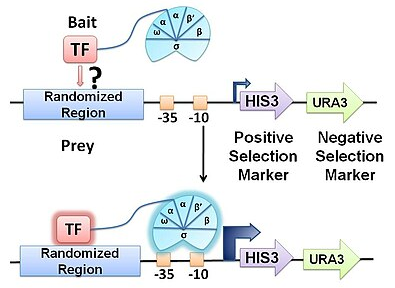

bacterial one-hybrid

method for defining PWM

genetic selection: survival is dependent on DNA-binding

TF of interest is fused to the alpha subunit of RNA pol

randomized library of binding sites created and screened for autoactivation

co transform w TF and selected

library complexity is limited by transformation efficiency

high-throughput SELEX

method for defining PWM

-incubate pure protein with high complexity DNA library

-pull down DNA-protein complexes

-amplify and sequence

JASPAR

open source repository for dna protein binding data

ChIP, PBM, SELEX

>50 different species spanning most clades

extract PWMs for downstream analysis

HOCOMOCO

homo sapiens comprehensive model

public repository of human-specific dna protein data

coverage of nearly all human dna binding domain classes

statistical definition of motif finding

given some sequences, find over-represented substrings (motif discovery)

biological definition of motif finding

given some co-regulated promoters, find transcription factor binding model

class I motif finding algorithms

planted motif problem: single species, multiple genes

-random background sequences

-proper description of a consensus motif gives better models

-randomly plant copies of the motif into sequences

-define an objective function, and use a search algorithm to find the copies that give a good score

exhaustive algorithm

not very tractable

construct every possible combination of alignments and keep the one with the highest information content

given a motif of width w, and k sequences of length l, there are L = (l-w+1) possible locations in each sequence, and L^k alignments to check

greedy algorithm (consensus)

-assume every sequence contains at least one true binding site

-using each l-mer find best match to generate 2-seq alignments

-using top K PWMs to search remaining sequences to include a new sequence

-repeat until all seqs contribute

MEME

Multiple Expectation Maximizations for motif elicitation

-intial “seed” PWM

use the current PWM to determine probability of all positions being sites

reestimate pwm based on the full set of those probabilities

continue until convergence - always convergences to a local maximum

EM is deterministic, meaning it is sensitive to initial seed and may not converge to the global maximum

for this reason, EM should be run multiple times with different seeds

Gibbs sampling

Similar to EM, but some differences:

-initial “seed” pwm

-use the current PWM to determine probability of all positions

-at each iteration, pick one site on each sequence, chosen by its probability to update the PWM, rather than updating using the full set of probabilities

-not guaranteed to converge, but tends to increase objective (IC) and plateau

-can escape local maxima, and therefore not sensitive to seed

gibbs sampling approach to motif discovery

-given “sites”, estimate pattern matrix

-given “matrix”, pick likely sites according to their probability

-iterate between those steps until “convergence”

important: using pseufocounts, and sample sites from estimated prob distribution

how gibbs sampling works

initialization: random assignment of motif locations a1-ak

pick “held-out” sequence

construct initial matrix S from alignment of matrix sequence

score all possible motif locations of held out sequence in A(i,j)

then select a new motif placement randomly based on probability distribution A(i,j)

hold out a new sequence, repeat until matrix converges on better motif window placements

however, sequence may have a placement with no real site, and sequences with more than one site might only have 1 placement

dna binding key take aways

-genome encodes much of its own regulation in protein binding sites

-a full description of the regulatory networks will require identifying these sites

-compact descriptions of the DNA-binding preferences of TFs is afforded by weight matrices

-the information content of an alignment is a measure of specificity

-weight matrix information for a TF is not enough to rule out false positives

-multiple experimental techniques exist for identifying sequences harboring binding sites

-a variety of algorithms can be used to identify motifs in unaligned data

-most predicted binding sites are false positives

class II motif finding algorithms

phylogenetic footprinting

single gene, multiple species

-orthologous background sequences

-sequences linked by a phylogenetic tree

-identify the “best conserved” motif that is under selective pressure

class III motif finding algorithms

multiple genes, multiple species

-combination of phylogenetic data and gene regulation

-use phylogenetic data to reduce search space

-use correlation of motif occurrences among orthologous genes to increase signal strength

CNNs

convolutional neural networks

-sequences are filtered through multiple convolutional layers (based on training sequences) and scored

-filtered sequence scores are pooled and max score retained

-many rounds of convolution → pooling can occur

-fully connected hidden layer used to score sequence

inputs:

-PBM/SELEX

-chromatin accessibility

-ChIP-seq or CUT&RUN/Tag

-principle is to represent sequences that are biologically meaningful in training set

large first filters

represent full motifs

small first filters

learn partial motifs

back propagation

determine the features being learned in early filter layers

-learn discrete sequence contributions to signal

saliency maps

can be used to identify real features that CNN deems important for prediction