SOC&HEALTH: what is social psychology

1/28

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

29 Terms

how did Allport (1954) define social psychology?

“the scientific investigation of how the thoughts, feelings and behaviours of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined or implied presence of others.” (Allport, 1954, p. 5).

actual presence: direct interaction (eg: your behavior might change depending on whether you are alone in a room or if there is an audience present when you are talking).

imagined presence: anticipating others’ reactions (eg: preparing to do a speech which you will deliver next week in front of many people, and anticipating their reaction).

implied presence: internalised social norms, conventions, language (eg: you refrain from littering, even if no one is around to see you, because you have internalized the social norm against littering).

what do social psychologists study, and what is their focus compared to other disciplines?

study human behaviour (not animals, except when exploring evolutionary origins— Hinde, 1982; Neuberg, Kenrick, & Schaller, 2010; Schaller, Simpson, & Kenrick, 2006).

behaviour includes overt actions (running, kissing), subtle signals (smiles, raised eyebrows), language, and writing.

behaviour is observable and measurable, but meaning depends on motives, goals, perspective, and culture.

also study unobservable processes (feelings, beliefs, goals) inferred from behaviour or that which influences behaviour.

what is the relationship between behaviour and internal processes in social psychology?

observable behaviour: this is what we can see and measure directly. it includes:

motor actions (running, kissing, driving),

subtle cues (a raised eyebrow, how someone dresses),

communication (spoken/written words).

unobservable processes: things like beliefs, attitudes, feelings, intentions, and goals. these can’t be observed directly, but can be inferred through behaviour.

link between the two:

social psychologists often study how inner states predict behaviour (eg: whether attitudes toward recycling predict actually recycling → attitude–behaviour correspondence).

they also study when behaviour reveals hidden attitudes (eg: subtle prejudice that appears in hiring decisions).

bigger picture: these unobservable processes are tied to cognitive systems (memory, categorisation) and sometimes even neural mechanisms (lieberman, 2010; todorov, fiske, & prentice, 2011).

eg:

if someone avoids sitting next to a stranger on the bus, the observable behaviour is moving away.

the unobservable process could be anxiety, prejudice, or desire for personal space. social psychology studies how those internal states map onto the outward action.

why is social psychology considered a science?

uses scientific method: build/test theories using verifiable data.

theories (sets of interrelated concepts) explain phenomena.

validity depends on correspondence with facts, not logic alone.

data are collected via empirical research.

examples of social psych concepts: dissonance, attitudes, categorisation, identity.

how does social psychology differ from individual psychology?

both are subdisciplines of psychology.

individual psychology: explains behaviour via processes in the individual mind (eg: perception of coin size).

social psychology: explains behaviour as socially influenced (eg: coin has value because others agree → influences size perception).

social psychology emphasises face-to-face interaction, group influence, implied presence.

how did freud contribute to social psychology?

through social psychology and the analysis of the ego (1921), Freud’s psychodynamic theory can be applied to social interactions.

psychodynamic ideas influenced explanations of a variety of social behaviours— eg: the unconscious mind, defense mechanisms, and the impact of childhood experiences on adult behavior.

this provided a framework for understanding how hidden motivations and conflicts shape social interactions. freud’s work introduced the idea that social and personal behaviors are not always rational but can be influenced by the id, ego, and superego, creating internal conflicts that play out in social settings.

how has cognitive psychology influenced social psychology?

since 1970s → social cognition became dominant approach.

uses methods (reaction times) and concepts (memory, categorisation).

explains a wide range of social behaviours.

key works: fiske & taylor (2013); moskowitz (2005); ross, lepper, & ward (2010); devine, hamilton, & ostrom (1994).

what role has neuroscience played in social psychology?

integrates brain biochemistry with social processes.

explains how neural activity underpins attitudes, stereotypes, social judgments.

key works: gazzaniga, ivry, & mangun (2013); lieberman (2010); todorov, fiske, & prentice (2011).

what is the relationship between social psychology and sociology?

sociology: explains organisation, structure, and change of societies.

social anthropology: similar, but historically studied tribal/non-industrial societies.

both explain at group level, whereas social psychology explains at individual-in-group level.

overlap: symbolic interactionism (mead, 1934; blumer, 1969), sociological psychology (delamater & ward, 2013).

social psychology also draws on marxist theories (billig, 1976).

shared interest in intergroup relations (hogg & abrams, 1988).

which other disciplines connect closely to social psychology?

sociolinguistics & communication: language, interaction (gasiorek, giles, holtgraves, & robbins, 2012; holtgraves, 2010, 2014).

literary criticism: discourse analysis (potter, stringer, & wetherell, 1984).

economics: behavioural economics → economic behaviour is not fully rational, influenced by others (cartwright, 2014).

applied psychology: overlaps with sports, health, organisational psychology.

what is the debate about the nature of social psychology?

social psychology lies at the crossroads of many disciplines.

if focus is too much on individual cognition → risks being cognitive/individual psychology.

if focus is too much on language → risks being sociolinguistics.

if focus is too much on social structure → risks being sociology.

debate: what counts as “proper” social psychology? → ongoing metatheoretical discussion.

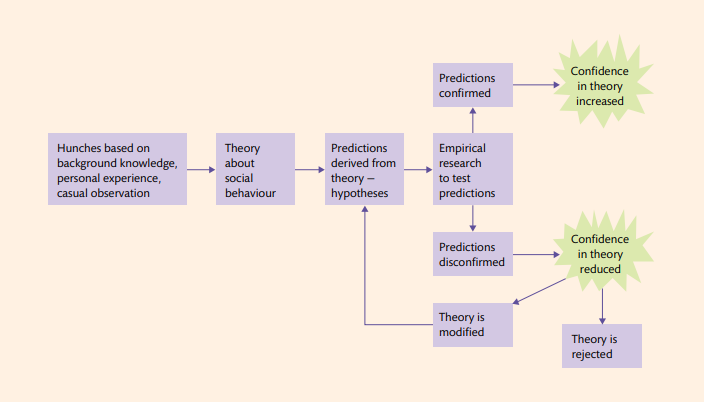

define hypotheses.

in science = hypotheses formed (predictions) on the basis of prior knowledge, speculation and observation.

hypotheses: formally stated predictions about what may cause something to occur (can be tested empirically to see if true).

eg: hypothesis = ballet dancers perform better in front of an audience than when dancing alone. hypothesis can be tested empirically by measuring + comparing their performance alone vs in front of audience.

BUT! while empirical tests can show that a hypothesis is false, they can't definitively prove it true. if evidence supports the hypothesis → can ONLY become more confident in it, but we MUST remain open to new evidence that might challenge it later.

hence— replicability/repeating experiments = important → helps ensure results aren't just due to chance/specific circumstances + prevent cheating/mistakes.

describe the scientific model used by social psychologists.

what are dogma and rationalism, and how do they differ from scientific methods?

instead of science, one simply believes it to be true, or because an authority. this is known as:

dogma/rationalism: believing something is true because of faith, authority, or personal belief, not because it has been tested.

eg: believing what a religious leader or ancient philosopher says without fact-checking it yourself.

even after the scientific revolution (championed by Copernicus & Galileo), many still rely on faith or authority for knowledge.

in social psychology, scientists use different methods to test ideas:

experimental methods: controlled tests, eg: experiments.

non-experimental methods: observations or surveys.

scientists choose methods based on what they are testing, resources, and ethics.

researchers try to avoid “confirmation bias,” where they only see what supports their ideas and ignore evidence that contradicts them.

describe what is meant by an ‘experiment.’

experiment: a hypothesis test in which something is done to see its effect on something else.

eg: i think my car uses too much petrol because the tyres are under-inflated → i test this by measuring petrol consumption over a week, then increasing tyre pressure and measuring again → if petrol use decreases after increasing the tyre pressure = my hypothesis is supported → vice versa.

systematic experiment (aka lab experiment) = most important research method → scientists establish a causal relationship and manipulate one or more independent variables and then observe/measure the effect on the dependent variables.

eg: changing tyre pressure (IV) to see how it impacts petrol consumption (DV).

independent variable: the variable that is manipulated or changed in the experiment (eg: tyre pressure).

dependent variable: the outcome that is measured (eg: petrol consumption).

what is a laboratory experiment.

definition: a laboratory experiment is conducted in a controlled environment (usually a room or lab space) where variables can be manipulated while minimising confounding factors.

purpose: to test the cause-and-effect relationship between an independent variable (iv) and a dependent variable (dv).

artificiality: labs deliberately create controlled, sometimes unrealistic conditions. this can isolate variables in ways real life cannot.

eg: markus (1978) studied social facilitation. participants did a well-learned task (dressing normally) and a poorly-learned task (dressing in unusual clothing), alone or in front of others.

results: performance improved for well-learned tasks in front of an audience but worsened for poorly-learned tasks.

importance: demonstrates how labs help identify subtle psychological processes that may be “hidden” in the complexity of everyday life.

describe the use of social neuroscience methods in labs.

integration: modern social psychology increasingly overlaps with biology and neuroscience.

hormonal methods: cortisol (stress hormone) levels in saliva measured after social interaction (townsend et al., 2011).

examined women's neuroendocrine stress responses associated with sexism. results: participants with higher chronic perceptions of sexism had higher cortisol, unless the situation contained cues that sexism was not possible.

brain imaging methods: fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) tracks blood-oxygen activity to identify which brain regions are active during social tasks (lieberman, 2010).

eg: eisenberger et al. (2003) found that social rejection activated the anterior cingulate cortex — the same region involved in physical pain. suggests that social pain is “real” in the brain.

importance: these techniques link social behaviour with physical and neurochemical processes, strengthening the biological basis of social psychology.

internal validity vs external validity.

internal validity:

the degree to which the results of a study can be trusted as showing a true cause-and-effect relationship. labs are strong here because they control extraneous variables.

external validity (mundane realism):

how well findings generalise to real-world situations. labs are weaker here because conditions are artificial.

experimental realism:

even if conditions are artificial, if participants find the task engaging and respond naturally, the results are still valuable (aronson et al., 1990).

eg: playing a computer game in a lab is not “real life,” but if it creates genuine competition or aggression, findings can still tell us something important about behaviour.

application: theories derived from lab studies (e.g. conformity, obedience, prejudice) can be generalised to real-world contexts, even if specific tasks are artificial.

define subject effects vs demand characteristics

subject effects: when participants’ behaviour is influenced by the fact they are being studied rather than by the manipulation itself.

eg: hawthorne studies (mayo, 1924–32)

workers at western electric’s hawthorne plant increased productivity whenever any change was introduced (lighting, rest breaks, etc).

productivity boost wasn’t because of the manipulations themselves but because participants knew they were being observed → subject effect.

demand characteristics: cues in the study that suggest to participants what is expected of them. they may consciously or unconsciously act to “help” the researcher.

eg: orme (1962) — coined the term SE.

demonstrated that participants try to “make sense” of the experiment and behave in ways they think confirm the researcher’s expectations— eg: in long, boring tasks (like memorising nonsense syllables for hours), participants didn’t drop out— instead, they assumed there must be a meaningful purpose, so they kept going.

difference:

subject effects: the umbrella term for unnatural participant behaviour caused by being in a study.

demand characteristics: a specific type of subject effects, when participants respond to perceived expectations of the study.

impact: threatens the validity of findings by producing artificial behaviour.

minimisation: use of deception, cover stories, or ensuring anonymity can reduce these effects.

define social desirability bias.

social desirability (rosenberg, 1969): participants want to appear in the best possible light, altering responses to avoid embarrassment or judgment.

eg: kinsey reports (1940s–50s, human sexuality research):

participants often underreported socially frowned-upon behaviors (eg: extramarital sex, homosexual experiences at the time) and overreported socially acceptable behaviors.

highlighted how sensitive topics are particularly vulnerable to social desirability bias.

impact: threatens the validity of findings by producing artificial behaviour.

minimisation: use of deception, cover stories, or ensuring anonymity can reduce these effects.

define evaluation apprehension.

evaluation apprehension: the fear or anxiety someone experiences when they believe they are being judged or evaluated by others, particularly in a social setting or when performing a task.

eg: cottrell et al. (1968) — audience and performance

participants performed a well-learned task (reading word lists) either alone, in front of a blindfolded audience, or in front of an attentive audience.

results: performance improved only in the attentive audience condition → people sped up because they feared evaluation.

shows that it’s not just the presence of others (as social facilitation theories claimed), but whether those others could evaluate you.

impact: threatens the validity of findings by producing artificial behaviour.

minimisation: use of deception, cover stories, or ensuring anonymity can reduce these effects.

define experimenter effects.

definition: biases introduced when the experimenter’s behaviour, tone, or expectations unintentionally influence participants.

eg: if an experimenter expects group a to perform better, they may give more encouragement or clearer instructions, unconsciously shaping the results.

rosenthal & jacobson’s (1968) “pygmalion effect” showed teacher expectations could influence student performance— illustrating how experimenter expectations can shape outcomes.

minimisation:

standardised instructions (eg: computer-delivered tasks).

double-blind procedure: neither participants nor experimenters know which condition participants are in. this reduces the possibility of subtle cues influencing results.

why do laboratory experiments often rely on psychology undergraduates?

opportunity sample: they are readily available in large numbers on campus.

universities often run subject pools, where students take part in research in exchange for course credit or to meet course requirements.

issues:

this creates WEIRD samples: participants are often Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic.

findings may be culturally biased or limited in generalisability— such samples may not represent the diversity of human behavior across cultures, socioeconomic backgrounds, or ages.

does this mean lab findings are invalid?

not necessarily. social psychologists argue:

theories (not single findings) are generalised.

replication across different populations helps address sampling bias.

methodological pluralism (using multiple methods and samples) strengthens validity.

eg: Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan (2010)— criticised psychology’s reliance on WEIRD participants, showing how findings from these groups may not generalise globally (eg: in studies of perception, fairness, or cooperation).

strengths and weaknesses of lab experiments.

strengths:

precise control of variables → strong internal validity.

ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

suitable for testing theoretical predictions.

weaknesses:

artificial settings → low external validity.

eg: milgram’s (1963) obedience study— criticised for artificial lab setup (shock machine unlikely in real life), but findings were powerful in showing human obedience under authority.

prone to subject effects (demand characteristics, social desirability).

experimenter effects if not carefully controlled.

reliance on WEIRD populations.

overall: lab experiments remain one of the most powerful tools in social psychology but must be balanced with field studies, naturalistic observations, and cross-cultural research for fuller understanding.

what are field experiments?

a field experiment is conducted in a real-world, naturalistic setting, rather than a controlled laboratory.

the researcher manipulates an independent variable (iv) and measures a dependent variable (dv), but participants are usually unaware they are in an experiment, which reduces artificiality.

eg: ellsworth, carlsmith & henson (1972) – researchers tested if prolonged eye contact created discomfort. at traffic lights, an experimenter either:

gazed directly (intensely) at a driver, or

looked away nonchalantly.

the dv was how fast drivers pulled away once the lights changed. results showed that direct, prolonged gaze sped up departure, suggesting that eye contact can trigger a mild “fight-or-flight” response.

what are the main advantages of field experiments?

high external validity: behaviours are studied in the real world, so findings can be generalised to everyday life more confidently.

low reactivity: participants usually don’t know they’re being studied, reducing demand characteristics and making behaviour more authentic.

spontaneous, natural behaviour: because the setting is familiar (e.g., driving, shopping, waiting at lights), participants behave as they normally would.

eg:

piliavin et al. (1969): the subway samaritan study – tested helping behaviour on a real subway train when a confederate collapsed, showing people were more likely to help if the victim appeared ill rather than drunk.

this study would not have had the same ecological validity if staged in a lab.

what are the main limitations of field experiments?

less control over extraneous variables: noise, weather, time of day, and uncontrollable social factors may interfere with results.

difficulty with random assignment: unlike in labs, it’s harder to assign participants systematically to conditions (eg: who happens to be at the traffic lights when the manipulation occurs).

measurement issues:

it’s difficult to assess internal states (eg: emotions, attitudes, motivations).

researchers often rely on observable behaviour only, such as how quickly someone drives away, whether someone helps, or if someone follows instructions.

ethical challenges: participants may be unaware they are being studied, raising issues of informed consent and deception.

how do field experiments differ from lab experiments?

field experiments:

conducted in natural settings → high external validity (results reflect real-life situations).

often non-reactive → fewer demand characteristics.

weaker control over extraneous variables → lower internal validity.

random assignment is often impractical.

lab experiments:

conducted in controlled settings → high internal validity (cause-and-effect conclusions more reliable).

high control over extraneous variables.

but risk artificiality, lowering external validity.

participants often aware they are in a study → increased risk of subject effects, demand characteristics, and experimenter bias.

example comparison:

lab: markus (1978) tested task performance speed with/without an audience in a controlled setting.

field: ellsworth et al. (1972) tested reactions to eye contact in traffic — a real-world setting with spontaneous responses.