PSY 200 - Quiz 2

1/12

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

13 Terms

Thinking

Thinking is the active mental process of manipulating internal ideas, images, and concepts to understand, reason, solve problems, and create knowledge. It encompasses a wide range of cognitive activities such as paying attention, learning, remembering, forming concepts, making judgments, and forming plans to achieve goals.

“Going beyond the information given” (Bruner, 1957)

“A complex and high-level ‘skill’ that ‘fill(s) up gaps in the evidence’” (Bartlett, 1958, p. 20)

“A process of searching through a problem space” (Newell & Simon, 1972)

“ [What we do] when we are in doubt about how to act, what to believe, or what to desire” (Baron, 2000, p. 6)

“System 2” (Kahneman, 2011)

Problem Space

Problem space is a mental representation of all possible states, actions, and solutions relevant to a given problem, consisting of an initial state, operators (transformations), and a goal state.

Problem-solving involves searching through this mental space to find a path from the initial state to the goal state, often using heuristics or algorithms to navigate the space effectively.

The complexity and accuracy of a person's problem space can significantly influence their ability to solve problems, especially for complex or unfamiliar tasks.

Heuristics

Heuristics are mental shortcuts or "rules of thumb," that people use to make quick, efficient decisions, solve problems, and form judgments, especially under conditions of uncertainty or limited time. While these shortcuts reduce mental effort and cognitive load, leading to quick "good enough" outcomes, they can also result in systematic errors, biases, and sub-optimal decisions.

Rules of Thumb: These are generalized strategies derived from past experiences that provide serviceable results without extensive analysis.

The Dual-Process Model

System 1 & System 2

System 1 refers to fast, intuitive, and automatic thinking, while System 2 involves slow, deliberate, and analytical thought.

System 1 relies on heuristics, intuition, emotions, and pattern recognition to make quick judgments, often leading to fast but potentially flawed judgments.

System 2 engages in conscious, effortful, logical reasoning to handle complex problems and correct the errors of System 1. System 2 engages in conscious reasoning, careful consideration, and evaluation of information.

System 1 and System 2 don't operate in isolation; they work together and often influence each other. System 1 can provide a quick answer that System 2 then examines for accuracy. A key function of System 2 is to override or correct the potentially flawed intuitions generated by System 1, leading to more rational decisions.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman popularized this dual-process model of thinking in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Focused Thinking and Unfocused Thinking

Focused thinking is a concentrated, conscious state used for analytical problem-solving and absorbing/learning specific information. It helps with precision and existing knowledge. Focused thinking characteristics include intense concentration, step-by-step reasoning, and the ability to apply existing knowledge and skills, often used for tasks requiring precision, such as learning a new skill, following a procedure, or solving structured problems with clear solutions.

Unfocused thinking, also referred to as diffused thinking, is a relaxed, often subconscious mode that allows the mind to wander, make broad connections, and foster creativity and innovation. It enables new insights and connections. Unfocused thinking characteristics include a relaxed, broad, and often subconscious state that allows the mind to wander and make connections across different knowledge domains, often used for complex problems, generating creative ideas, finding new solutions, and developing a broader understanding.

Problem

Well-Defined Problem & Ill-Defined Problem

A problem is a goal-oriented situation where there is an initial state and a desired goal state, but no clear or immediately apparent way to get from the start to the finish. This definition includes three core components: the goal (what you want to achieve), the initial state (what you have), and operators (the tools or rules you can use to reach the goal).

Well-defined problems have clear initial states, goals, and operators (rules or methods), leading to a specific and often singular solution. There's a finite set of rules or actions that can be applied to transform the problem state, and the desired end state is specific and unambiguous. For example, solving a math equation or a chess game with defined rules.

Ill-defined problems are ambiguous, with unclear initial states and goals, indefinite operators, and multiple potential solutions, requiring creative and flexible thinking to navigate. The steps or methods to solve the problem are not obvious and may be numerous or nonexistent, and there is often no single "right" answer, and solutions can be open to interpretation. For example, deciding on a career, writing a short story, or dealing with complex personal relationships.

Well-defined problems are easier to study in lab scenarios; for that reason, it is generally assumed that solving ill-defined problems works in similar ways as well-defined problems.

Generate-And-Test

The generate-and-test method is a problem-solving strategy where a system generates potential solutions and then evaluates each one until an acceptable solution is found. This method, however, loses its effectiveness when there are many possibilities (e.g., trying all possible combinations in a lock).

Means-End Analysis

Means-end analysis (MEA) is a problem-solving strategy where a person breaks down a large problem into smaller, manageable sub-goals by comparing the current state to the desired end state, identifying the differences, and determining the steps (means) needed to achieve each sub-goal and ultimately the final goal.

This method involves repeatedly assessing the gap between the current situation and the ultimate goal, creating intermediate goals, and taking actions to reduce that gap, making it a systematic way to tackle complex challenges.

It starts with a goal, then analyzes the current starting point, and creating steps (the means) towards reaching the goal (desired end point); generating a plan to solve the problem.

Working Backward

Working backward is a problem-solving heuristic where one starts from the desired end goal and works backward through the necessary steps to reach the starting point.

This strategy involves visualizing the solved problem and then reversing the process to discover how to achieve it, often making complex problems more manageable and efficient to solve.

Working backwards does not usually involve making a move and seeing what happens. It is most effective when the backward path is unique.

Similar to means-end analysis, working backwards attempts to reduce the difference between the current state and the goal state, and often includes subgoals.

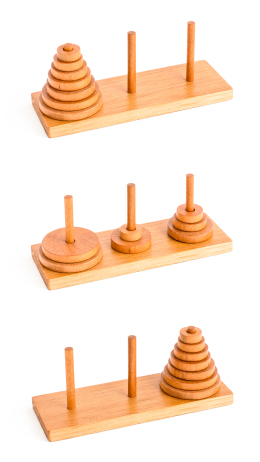

An example of working backward is the Towers of Hanoi problem.

The Towers of Hanoi Problem

The Towers of Hanoi problem is a classic puzzle used to assess and study executive functions, particularly problem-solving, planning, working memory, and self-monitoring.

The task involves moving a stack of disks of different sizes from one peg to another, one at a time, following specific rules (larger disks cannot be placed on smaller ones).

Backtracking

Backtracking is a problem-solving strategy that involves returning to a previous decision point and trying a different alternative path after encountering a dead end or an incorrect solution.

It's a systematic, trial-and-error method to build solutions incrementally by abandoning incorrect paths and exploring new ones until a valid solution is found.

This process relies on memory to remember past choices and uses it to make new ones, similar to navigating a maze.

One makes provisional assumptions about a problem’s solution. Then, keep track of when and which assumptions were made, in case one has to “undo” them (keeping track of “choice” points).

Provisional Assumptions

Provisional assumptions are temporary, often unconscious, beliefs or suppositions that the mind uses to quickly interpret and make sense of information. These cognitive shortcuts, or heuristics, allow for rapid decision-making and problem-solving without needing to fully analyze every detail of a situation.

Provisional assumptions are not based on complete evidence and are understood to be flexible and revisable as new information becomes available. They are the mental "best guesses" that the brain makes to navigate the world efficiently.

Reasoning By Analogy

Reasoning by analogy is a cognitive process/problem-solving technique of applying knowledge from a familiar situation (the source domain) to understand or solve a problem in a new situation (the target domain) by recognizing deep relational similarities (patterns) between the two.

It involves mapping corresponding elements and their relations from the source to the target, allowing for inferences and the formation of abstract categories based on shared structures, thereby simplifying complexity and fostering creative solutions.