Chemistry The Central Science Chapter 6

1/23

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

24 Terms

A spectrum is produced when radiation from such sources is separated into its component wavelengths

The resulting spectrum consists of a continuous range of colors—violet merges into indigo, indigo into blue, and so forth, with no blank spots. This rainbow of colors, containing light of all wavelengths, is called a continuous spectrum. The most familiar example of a continuous spectrum is the rainbow produced when raindrops or mist acts as a prism for sunlight

Each colored line in such spectra represents light of one wavelength.

A spectrum containing radiation of only specific wavelengths is called a line spectrum.

Bohr's Model

Bohr assumed that electrons in hydrogen

atoms move in circular orbits around the nucleus, but this assumption posed a problem.

According to classical physics, a charged particle (such as an electron) moving in a circular path should continuously lose energy. As an electron loses energy, therefore, it should

spiral into the positively charged nucleus. This behavior, however, does not happen—

hydrogen atoms are stable. So how can we explain this apparent violation of the laws of

physics? Bohr approached this problem in much the same way that Planck had approached the problem of the nature of the radiation emitted by hot objects: He assumed

that the prevailing laws of physics were inadequate to describe all aspects of atoms. Furthermore, he adopted Planck's idea that energies are quantized.

Bohr based his model on three postulates:

1. Only orbits of certain radii, corresponding to certain specific energies, are

permitted for the electron in a hydrogen atom.

2. An electron in a permitted orbit is in an "allowed"energy state.An electron in an allowed

energy state does not radiate energy and, therefore, does not spiral into the nucleus.

3. Energy is emitted or absorbed by the electron only as the electron changes from one

allowed energy state to another. This energy is emitted or absorbed as a photon that

has energy .

In 1900 a German physicist named Max Planck (1858-1947) solved the problem by assuming that energy can be either released or absorbed by atoms only in discrete "chunks" of some minimum size. Planck gave the name quantum (meaning "fixed amount") to the smallest quantity of energy that can be emitted or absorbed as electromagnetic radiation. He proposed that the energy, E, of a single quantum equals a constant times the frequency of the radiation:

The energy E of a single quantum is E = hv, where h is Planck's constant and v is the frequency of the radiation.

The constant h is called Planck's constant and has a value of joulesecond (J-s).

6.626 x 10^-34

Einstein assumed that the radiant energy striking the metal surface behaves like a stream of tiny energy packets. Each packet, which is like a "particle" of energy, is called a photon

Extending Planck's quantum theory, Einstein deduced that each photon must have an energy equal to Planck's constant times the frequency of the light: Energy of photon = E = hv

Thus, radiant energy itself is quantized. Under the right conditions, photons striking a metal surface can transfer their energy to electrons in the metal. A certain amount of energy—called the work function —is required for the electrons to overcome the attractive forces holding them in the metal. If the photons striking the metal have less energy than the work function, the electrons do not acquire sufficient energy to escape from the metal, even if the light beam is intense. If the photons have energy greater than the work function of the particular metal, however, electrons are emitted. The intensity (brightness) of the light is related to the number of photons striking the surface per unit time but not to the energy of each photon.

To better understand what a photon is, imagine you have a light source that produces radiation of a single wavelength. Further suppose that you could switch the light on and off faster and faster to provide ever-smaller bursts of energy. Einstein's photon theory tells us that you would eventually come to the smallest energy burst, given by E = hv. This smallest burst consists of a single photon of light

The idea that the energy of light depends on its frequency helps us understand the diverse effects of different kinds of electromagnetic radiation. For example, because of the high frequency (short wavelength) of X-rays (Figure 6.4), X-ray photons cause tissue damage and even cancer.

Thus, signs are normally posted around X-ray equipment warning us of high-energy radiation. Although Einstein's theory of light as a stream of photons rather than a wave explains the photoelectric effect and a great many other observations, it also poses a dilemma. Is light a wave, or is it particle-like? The only way to resolve this dilemma is to adopt what might seem to be a bizarre position: We must consider that light possesses both wave-like and particle-like characteristics and, depending on the situation, will behave more like waves or more like particles. We will soon see that this dual nature of light is also a characteristic trait of matter

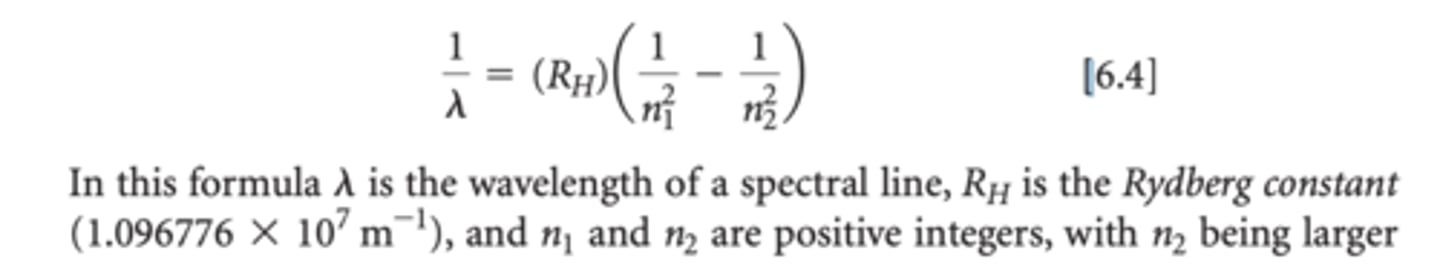

. In 1885, a Swiss schoolteacher named Johann Balmer showed that the wavelengths of these four lines fit an intriguingly simple formula that relates the wavelengths to integers. Later, additional lines were found in the ultraviolet and infrared regions of hydrogen's line spectrum. Soon Balmer's equation was extended to a more general one, called the Rydberg equation, which allows us to calculate the wavelengths of all the spectral lines of hydrogen:

...

The collection of orbitals with the same value of n is called an electron shell.

orbitals that have the same n and l values is called a subshell. Each subshell is designated by a number (the value of n) and a letter (s, p, d, or f, corresponding to the value of l ). For example, the orbitals that have and are called 3d orbitals and are in the 3d subshel

Principal Quantum Number (n):

What it describes: The main energy level or shell of the electron.

• Possible values: \(n = 1, 2, 3, \dots\)

• Equation: No specific equation, but higher n values correspond to higher energy levels.

Azimuthal Quantum Number (l):

What it describes: The shape of the orbital (subshell) where the electron is located.

• Possible values: l = 0 to n-1

• Equation: l = 0 (s-orbital), l = 1 (p-orbital), l = 2 (d-orbital), l = 3 (f-orbital)

Magnetic Quantum Number (m_l):

What it describes: The orientation of the orbital in space.

• Possible values: m_l = -l to +l

• Equation: If l = 1, m_l can be -1, 0, or +1, corresponding to the three orientations of a p-orbital.

The shell with principal quantum number n consists of exactly n subshells. Each subshell corresponds to a different allowed value of l from 0 to . Thus, the first shell consists of only one subshell, the ; the second shell consists of two subshells, the and ; the third shell consists of three subshells, 3s, 3p, and 3d, and so forth. 2. Each subshell consists of a specific number of orbitals. Each orbital corresponds to a different allowed value of . For a given value of l, there are allowed values of , ranging from to . Thus, each subshell consists of one orbital; each subshell consists of three orbitals; each subshell consists of five orbitals, and so forth. 3. The total number of orbitals in a shell is , where n is the principal quantum number of the shell.

his relationship further in Section 6.9. FIGURE 6.17 shows the relative energies of the hydrogen atom orbitals through . Each box represents an orbital, and orbitals of the same subshell, such as the three 2p orbitals, are grouped together. When the electron occupies the lowest-energy orbital (1s ), the hydrogen atom is said to be in its ground state. When the electron occupies any other orbital, the atom is in an excited state. (The electron can be excited to a higher-energy orbital by absorption of a photon of appropriate energy.) At ordinary temperatures, essentially all hydrogen atoms are in the ground state

One way to address this question is to look at the radial probability function, also called the radial probability density, which is defined as the probability that we will find the electron at a specific distance from the nucleus. FIGURE 6.18 shows

shows the radial probability density for the 1s, 2s, and 3s orbitals of hydrogen as a function of r, the distance from the nucleus. Three features of these graphs are noteworthy: the number of peaks, the number of points at which the probability function goes to zero (called nodes), and how spread out the distribution is, which gives a sense of the size of the orbital.

Comparing the radial probability distributions for the 1s, 2s, and 3s orbitals reveals three trends:

1. The number of peaks increases with increasing n, with the outermost peak being larger than inner ones. 2. The number of nodes increases with increasing n. 3. The electron density becomes more spread out with increasing n

One widely used method of representing orbital shape is to draw a boundary surface that encloses some substantial portion, say , of the electron density for the orbital.

This type of drawing is called a contour representation, and the contour representations for the s orbitals are spheres ( FIGURE 6.19). All the orbitals have the same shape, but they differ in size, becoming larger as n increases, reflecting the fact that the electron density becomes more spread out as n increases. Although the details of how electron density varies within a given contour representation are lost in these representations, this is not a serious disadvantage. For qualitative discussions, the most important features of orbitals are shape and relative size, which are adequately displayed by contour representations.

The radial probability functions in Figure 6.18 provide us with the more useful information because they tell us the probability of finding the electron at all

points a distance r from the nucleus, not just one particular point.

Orbitals with the same energy are said to be

degenerate

The Pauli exclusion principle

The Pauli exclusion principle states that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers n, l, ml , and ms. For a given orbital, the values of n, l, and are fixed.

Armed with knowledge of the relative energies of orbitals and the Pauli exclusion principle, we are in a position to consider the arrangements of electrons in atoms. The way electrons are distributed among the various orbitals of an atom is called the electron configuration of the atom

. The Pauli exclusion principle tells us, however, that there can be at most two electrons in any single orbital. Thus, the orbitals are filled in order of increasing energy, with no more than two electrons per orbital. For example, consider the lithium atom, which has three electrons. (Recall that the number of electrons in a neutral atom equals its atomic number.) The ls orbital can accommodate two of the electrons. The third one goes into the next lowest energy orbital, the 2s.

Hund's rule, which states that for degenerate orbitals, the lowest energy is attained when the number of electrons having the same spin is maximized.

This means that electrons occupy orbitals singly to the maximum extent possible and that these single electrons in a given subshell all have the same spin magnetic quantum number. Electrons arranged in this way are said to have parallel spins. For a carbon atom to achieve its lowest energy, therefore, the two 2p electrons must have the same spin. For this to happen, the electrons must be in different 2p orbitals, as shown in Table 6.3. Thus, a carbon atom in its ground state has two unpaired electrons.

The actinide elements are radioactive, and most of them are not found in nature.

Thus, it takes 14 electrons to fill the 4f orbitals completely. The 14 elements corresponding to the filling of the 4f orbitals are known as either the lanthanide elements or the rare earth elements.

On the right is a block of six pink columns that comprises the p block, where the valence p orbitals are being filled. The s block and the p block elements together are the representative elements, sometimes called the main-group elements.

The elements in the two tan rows containing 14 columns are the ones in which the valence f orbitals are being filled and make up the f block. Consequently, these elements are often referred to as the f-block metals. In most tables, the f block is positioned below the periodic table to save space: