Motivation

1/13

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

14 Terms

Motivation

Driving force

Physical need

Wanting, liking

Hypothalamus maintains homeostasis including emotions and behaviour e.g drinking and eating

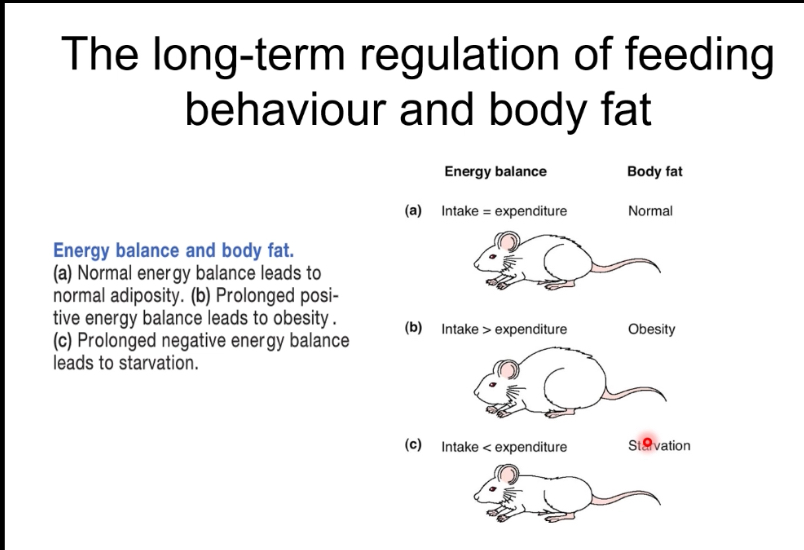

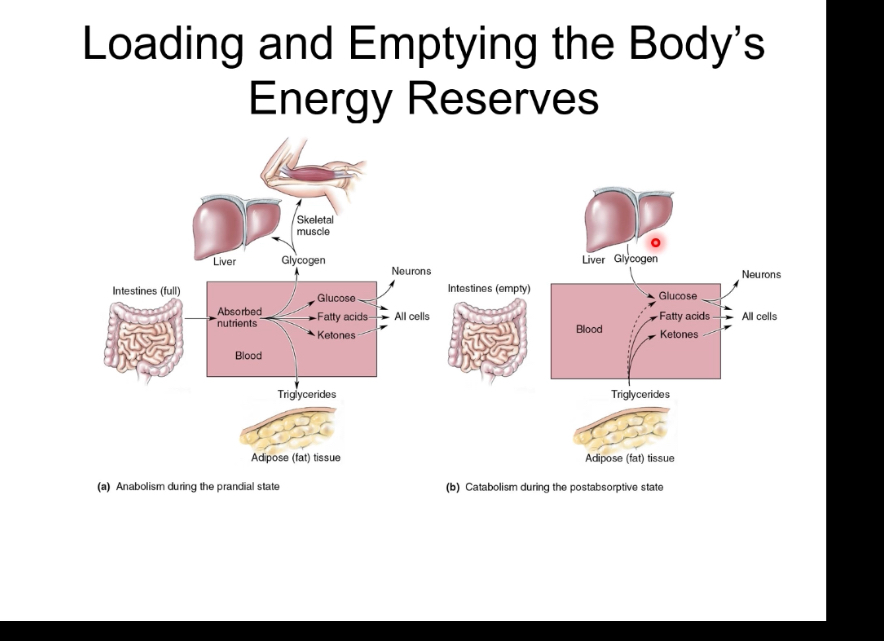

The body’s energy reserve

After eating, insulin is high, nutrients enter the blood, and energy is stored: glucose becomes glycogen in liver and muscle, and excess energy is stored as triglycerides in adipose tissue.

During fasting, insulin is low and glucagon is high, stored energy is released: liver glycogen is broken down, new glucose and ketones are made, and fatty acids from fat tissue supply energy.

Overall, the body switches between energy storage (fed state) and energy mobilisation (fasting state) to maintain blood glucose and ATP.

What controls feeding behaviour

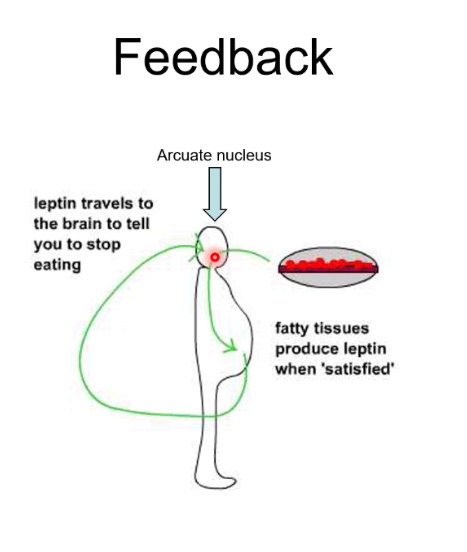

Leptin

Example:

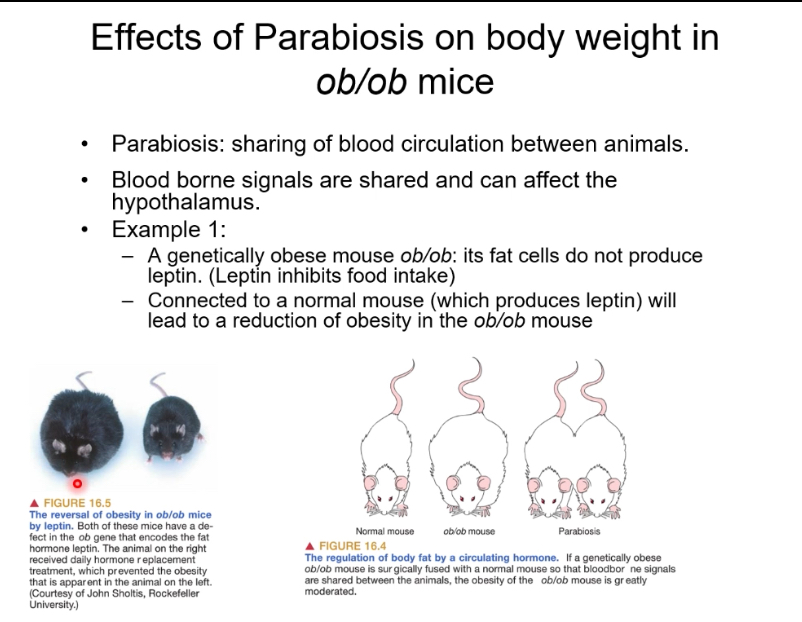

Parabiosis is the surgical joining of two animals so they share a blood supply.

• Blood-borne signals can act on the hypothalamus to regulate food intake and body weight.

• ob/ob mice are genetically obese because they do not produce leptin, a hormone that suppresses appetite.

• When an ob/ob mouse is connected to a normal mouse, leptin from the normal mouse circulates into the ob/ob mouse.

• This reduces food intake and body weight in the ob/ob mouse.

• Conclusion: body fat and appetite are regulated by a circulating hormone (leptin)

VMH and LH: effects on food intake

Food intake is controlled by opposing hypothalamic centres.

Damage to each centre shifts eating behaviour in opposite directions.

These centres are regulated by leptin signalling from adipose tissue.

Lateral hypothalamus (LH) – hunger centre

Normally promotes feeding behaviour and food-seeking.

Activated when energy stores are low.

Lesion of LH

Loss of hunger drive.

Reduced food intake.

Leads to anorexia and weight loss.

This state is called lateral hypothalamic syndrome.

Ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) – satiety centre

Normally inhibits feeding once enough energy is consumed.

Signals fullness and suppresses appetite.

Lesion of VMH

Loss of satiety signals.

Excessive eating (hyperphagia).

Leads to obesity.

This state is called ventromedial hypothalamic syndrome.

Role of leptin

Leptin is released from adipose tissue in proportion to fat stores.

Leptin acts on the hypothalamus to:

Inhibit LH-driven hunger.

Activate VMH-mediated satiety.

Disruption of leptin signalling mimics VMH damage → overeating and obesity

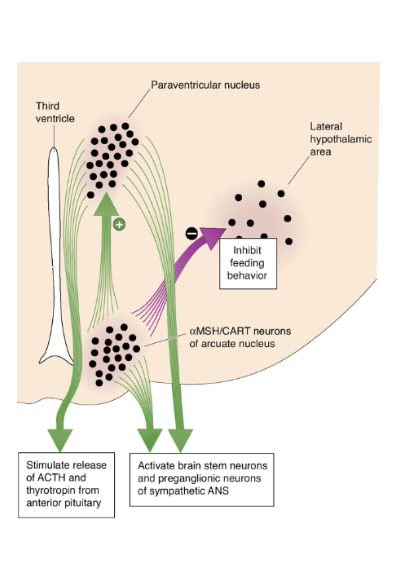

Arcuate nucleus

• The arcuate nucleus is the main hypothalamic centre that senses body fat levels.

• Leptin from adipose tissue acts on the arcuate nucleus.

• Leptin inhibits hunger-promoting NPY/AgRP neurons and activates satiety-promoting POMC/CART neurons.

• These neurons project to other hypothalamic areas (PVN and LH) to control feeding.

• High leptin reduces food intake; low leptin increases hunger.

Anorexic response

High leptin signals high energy stores.

• Leptin activates POMC/CART neurons and inhibits NPY/AgRP neurons in the arcuate nucleus.

• α-MSH acts on the paraventricular nucleus to suppress feeding.

• Lateral hypothalamic hunger drive is reduced.

• Net effect: decreased appetite and food intake (anorexic response).J

Orexigenic Response

An orexigenic response occurs when leptin levels are low.

Low leptin shifts arcuate nucleus output toward hunger-promoting pathways.

Detection of low leptin

Reduced fat stores → decreased leptin release from adipose tissue.

Low leptin is sensed by neurons in the arcuate nucleus.

Arcuate nucleus neuron activity

NPY / AgRP neurons

Activated when leptin is low.

Release neuropeptide Y (NPY) and AgRP.

POMC / CART neurons

Suppressed when leptin is low.

Reduced α-MSH release.

Downstream hypothalamic effects

Paraventricular nucleus (PVN)

Inhibited by NPY/AgRP neurons.

Reduced release of hypophysiotropic hormones (e.g. CRH, TRH → ↓ ACTH and TSH).

Lowers energy expenditure.

Lateral hypothalamic area (LH)

Activated by NPY/AgRP neurons.

Stimulates feeding behaviour.

Some LH neurons release MCH, which promotes eating.

Physiological outcome

Increased appetite.

Increased food intake.

Energy conservation during low fat / starvation states.

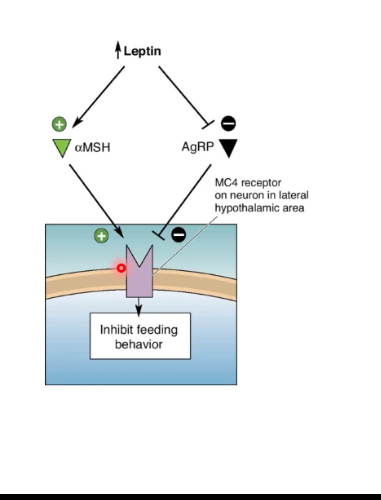

MC4 Receptor

Feeding behaviour is controlled by competition at the MC4 receptor.

• Anorexigenic and orexigenic signals converge on this single receptor.

MC4 receptor (MC4R)

• Located on hypothalamic neurons (especially in PVN/LH pathways).

• When activated → feeding is inhibited.

α-MSH (anorexigenic signal)

• Produced from POMC neurons in the arcuate nucleus.

• Release is promoted by high leptin.

• Binds and activates MC4R.

• Result:

• Suppresses appetite.

• Increases energy expenditure.

AgRP (orexigenic signal)

• Released from NPY/AgRP neurons in the arcuate nucleus.

• Promoted by low leptin.

• Antagonises / inhibits MC4R.

• Prevents α-MSH from activating the receptor.

• Result:

• Promotes feeding.

• Reduces energy expenditure.

Role of leptin

• High leptin

• ↑ α-MSH

• ↓ AgRP

• MC4R activated → feeding inhibited

• Low leptin

• ↓ α-MSH

• ↑ AgRP

• MC4R blocked → feeding stimulated

LH: MCH and Orexin

The lateral hypothalamus (LH) promotes feeding.

Two key peptides from LH neurons fine-tune when eating starts and how long it continues.

Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH)

Produced by a subset of LH neurons.

Has widespread projections throughout the brain.

Main effect

Prolongs food consumption once eating has started.

Functional role

Maintains feeding.

Supports sustained intake and positive energy balance.

Overactivity is associated with weight gain.

Orexin (hypocretin)

Produced by a different subset of LH neurons.

Also has widespread cortical and brainstem connections.

Main effect

Initiates feeding behaviour.

Functional role

Triggers meal onset.

Links feeding to arousal, wakefulness, and motivation.

How they differ

Orexin → starts the meal.

MCH → keeps the meal going.

Integration with leptin pathways

When leptin is low:

Arcuate NPY/AgRP neurons activate LH neurons.

Orexin and MCH activity increases.

Result: increased hunger, meal initiation, and prolonged eating.

Satiety

Satiety is short-term meal control.

• It suppresses eating after a meal using gut-derived signals that act on the brain.

What satiety is

• A feeling of fullness that suppresses hunger for a period after eating.

• Determines meal size and time to the next meal, not long-term body weight.

Where satiety signals come from

• Signals begin as soon as food is consumed and continue during digestion and absorption.

• Main sources:

• Stomach: stretch/distension.

• Intestine: nutrients entering the gut.

• Gut hormones (e.g. CCK, GLP-1, PYY).

• Signals travel via:

• Vagal afferents.

• Blood-borne hormones to the brainstem and hypothalamus.

How satiety stops a meal (short-term model)

• Eating starts → orexigenic drive is high.

• As food enters the gut:

• Satiety signals rise.

• These inhibit feeding circuits.

• When satiety signals peak:

• Food intake stops.

• Over time:

• Satiety signals fall.

• Orexigenic drive rises again → next meal begins.

Brain integration

• Brainstem (e.g. NTS) receives gut signals first.

• Hypothalamus integrates these with motivational circuits.

• Satiety pathways temporarily override hunger pathways.

The Satiety Cascade

Short-term regulation of feeding controls when a meal starts and when it ends.

• It is driven by a cascade of signals that begin before eating, rise during eating, and peak after food enters the gut.

• These signals produce satiation (meal termination) and satiety (suppression of hunger after the meal).

Phase 1: Cephalic phase (before eating)

• Triggered by sight, smell, taste, and anticipation of food.

• Ghrelin is released when the stomach is empty.

• Ghrelin:

• Activates NPY/AgRP neurons in the arcuate nucleus.

• Increases hunger and meal initiation.

• Cephalic insulin release prepares the body for incoming nutrients.

• This phase explains why hunger can occur before food is consumed.

Phase 2: Gastric phase (during eating)

• Begins once food enters the stomach.

• Gastric distension activates stretch receptors.

• Signals are sent to the brain via the vagus nerve.

• Produces satiation:

• Gradual reduction in eating rate.

• Contributes to ending the meal.

Phase 3: Intestinal / substrate phase (after eating)

• Triggered as nutrients enter the intestine and are absorbed.

• Gut hormones released:

• CCK (especially in response to fat).

• GLP-1, somatostatin.

• Effects:

• Act via vagal afferents and circulation.

• Inhibit feeding circuits.

• Slow gastric emptying.

• Insulin released from pancreatic β-cells:

• Acts on the arcuate nucleus.

• Reinforces satiety signals.

• Oxidative metabolism of glucose, amino acids, and fat sustains satiety.

Satiation vs satiety

Satiation

• Develops during a meal.

• Causes meal termination.

Satiety

• Develops after a meal.

• Suppresses hunger until the next meal.

• Leptin modulates this system long-term but is not the main short-term signal.

Dopamine

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that changes how strongly neurons signal in circuits controlling motivation, reward, learning, and movement.

Its key effect is modulating neural activity, not simply “causing pleasure”.

It signals the importance or value of an outcome and helps reinforce behaviours that lead to it.

Dopamine in reward and motivation

Dopamine release increases when an outcome is better than expected.

This strengthens synaptic connections in reward circuits, making the brain more likely to repeat the behaviour.

It is central to reinforcement learning (learning from rewards and prediction errors).

Major dopamine pathway (reward circuit)

Dopamine neurons originate in the ventral tegmental area (VTA).

They project to the nucleus accumbens, part of the limbic system.

Activation of this pathway increases motivation, wanting, and goal-directed behaviour.

Addiction Cycle

Addiction is driven by a shift in brain motivation systems: behaviour moves from being reinforced by dopamine-mediated reward to being driven by avoidance of negative emotional states.

The key change is a progressive dysregulation of reward (dopamine) and stress systems, which locks behaviour into a repeating cycle.

Stage 1: Acute reinforcement / social drug-taking

Drug use initially increases dopamine release in reward pathways.

This produces positive reinforcement: the behaviour is repeated because it feels rewarding.

Use is typically voluntary, intermittent, and context-dependent.

Learning links the drug with environmental cues.

Stage 2: Escalation and compulsive use

Repeated exposure causes neuroadaptations in dopamine signalling.

Larger or more frequent doses are needed to achieve the same effect (tolerance).

Control over intake weakens and use becomes habitual and compulsive.

Stress and conditioned cues increasingly trigger use.

Stage 3: Dependence

The brain’s baseline state changes.

Normal dopamine signalling is reduced when the drug is absent.

Stress systems become overactive.

Drug use is no longer mainly about reward, but about maintaining a new “normal”.

Stage 4: Withdrawal

When the drug is removed, dopamine activity drops further.

Stress and anxiety systems dominate.

Symptoms include dysphoria, irritability, anxiety, and physical effects.

Drug-taking now produces negative reinforcement: it relieves unpleasant withdrawal states.

Stage 5: Protracted withdrawal

Even after acute withdrawal ends, reward and stress systems remain dysregulated.

Sensitivity to stress is high and mood remains low.

This state strongly increases vulnerability to relapse.

Relapse

Stress, environmental cues, or small re-exposures reactivate learned drug associations.

Craving emerges due to long-lasting changes in brain circuits.

The cycle restarts, often rapidly returning to compulsive use.

What shifts from non-dependent to dependent states

Non-dependent: behaviour driven mainly by dopamine-based positive reinforcement.

Dependent: behaviour driven mainly by relief from negative emotional and physical states.

Stress circuits increasingly dominate over reward circuits as dependence develops

D2 receptors

Both obesity and drug addiction show reduced dopamine D2 receptor availability in reward circuits (especially the striatum/nucleus accumbens).

Lower D2 signalling means rewards feel less effective, so behaviour escalates to compensate (more food or more drug).

Chronic overstimulation of dopamine causes down-regulation of D2 receptors, reinforcing compulsive use.

Reinforcement circuits (VTA → nucleus accumbens, with amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex input) become biased toward habitual, cue-driven behaviour.

Over time, behaviour shifts from reward-seeking to relief of a low-reward, high-stress baseline state, increasing relapse risk.