Intro to Physical Geography Exam 4/Final

1/261

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

262 Terms

Carbon Cycle

the system of processes through which carbon moves between the atmosphere, living organisms, the oceans, soils, and Earth's crust. It is one of Earth's most important biogeochemical cycles because it regulates atmospheric CO2, which directly controls climate.

It has two different branches

1. The Organic Carbon Cycle (fast cycle)

-terrestrial organic carbon cycle

-marine organic carbon cycle

-short term (days to decades) vs. long term (centuries to thousands of years)

2. The Inorganic Carbon Cycle (Geologic, slow cycle)

Why is the global carbon cycle so important?

1. Necessary for life

2. Regulates Earth's temperature

3. Maintains ocean acidity balance

4. Maintains an oxygenated atmosphere

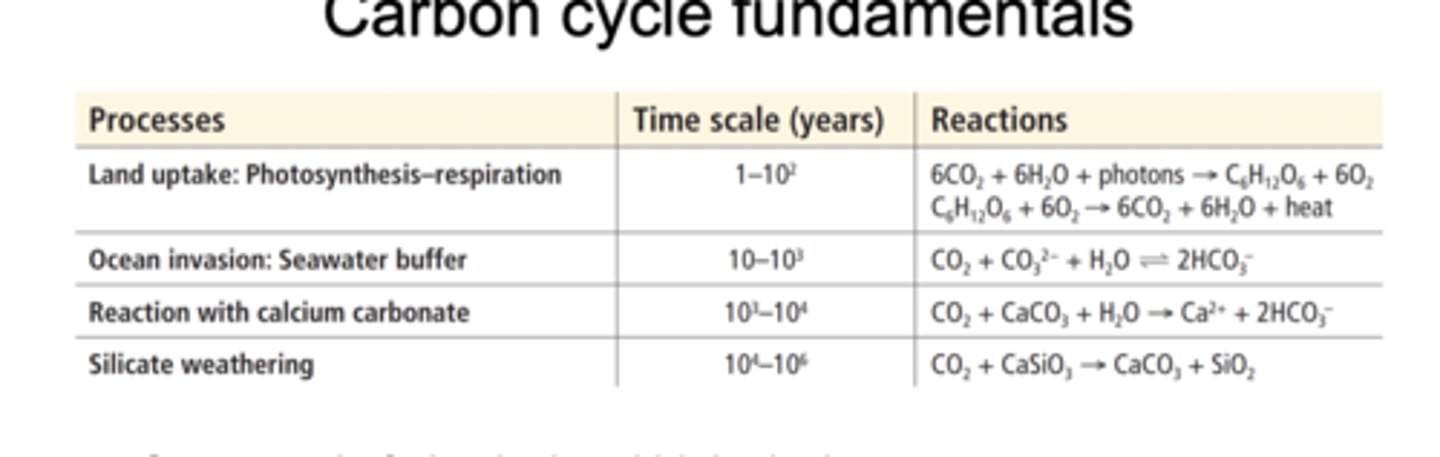

Carbon cycle fundamentals

The carbon cycle consists of both biological and physical process that move carbon through the atmosphere, land, oceans, and Earth's crust over timescales ranging from years to millions of years.

Biological processes like land uptake (photosynthesis and respiration) are fast, ranging from years to decades

Physical and chemical processes like ocean CO2 invasion, reaction with calcium carbonate, and silicate weathering are slow, ranging from centuries to millions of years

Organic Carbon Cycle

The circulation of carbon between the atmosphere, plants, animals, soils, and the ocean's living organisms. It is driven by life- especially photosynthesis and respiration- and it regulates atmospheric CO2 on short timescales.

How Carbohydrate CH20 is produced in the organic carbon cycle

Organic carbon is added to the carbon cycle through photosynthesis where inorganic carbon (CO2) is converted into (CH20) when plants on land and phytoplankton in the ocean take in CO2 and light energy and make organic matter through primary production

Once CH20 is created it moves through organisms by decomposition, consumption, and respiration

Respiration occurs so organisms can break down CH20 to release energy, returning CO2 to the atmosphere or ocean

When organisms die, microbes break down heir organic matter, releasing CO2 and returning nutrients to soil and waters

Organic carbon moves on two different timescales

-short term (10^2= decades-centuries) through photosynthesis, respiration, decomposition, ocean atmosphere gas exchange

-long term (10^6 millions of years) through burial of organic matter in sediments and transformation into fossil fuels

Short term organic carbon cycle components

1. Marine and terrestrial plants and animals

2. Soil carbon

3. Atmospheric CO2

Photosynthesis

CO2+2H20=CH20+O2+H20

Uses energy from the Sun to create organic carbon from inorganic carbon

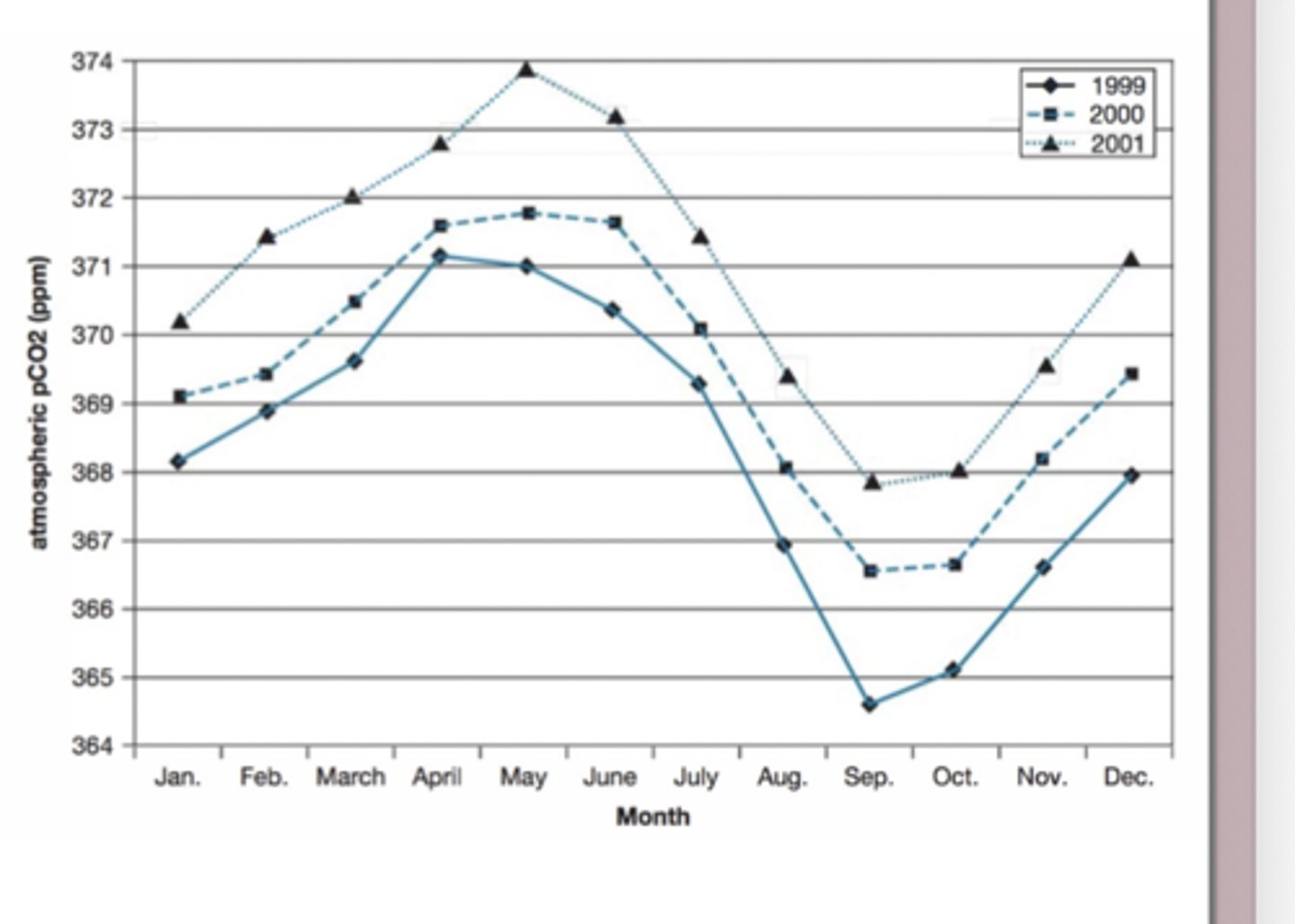

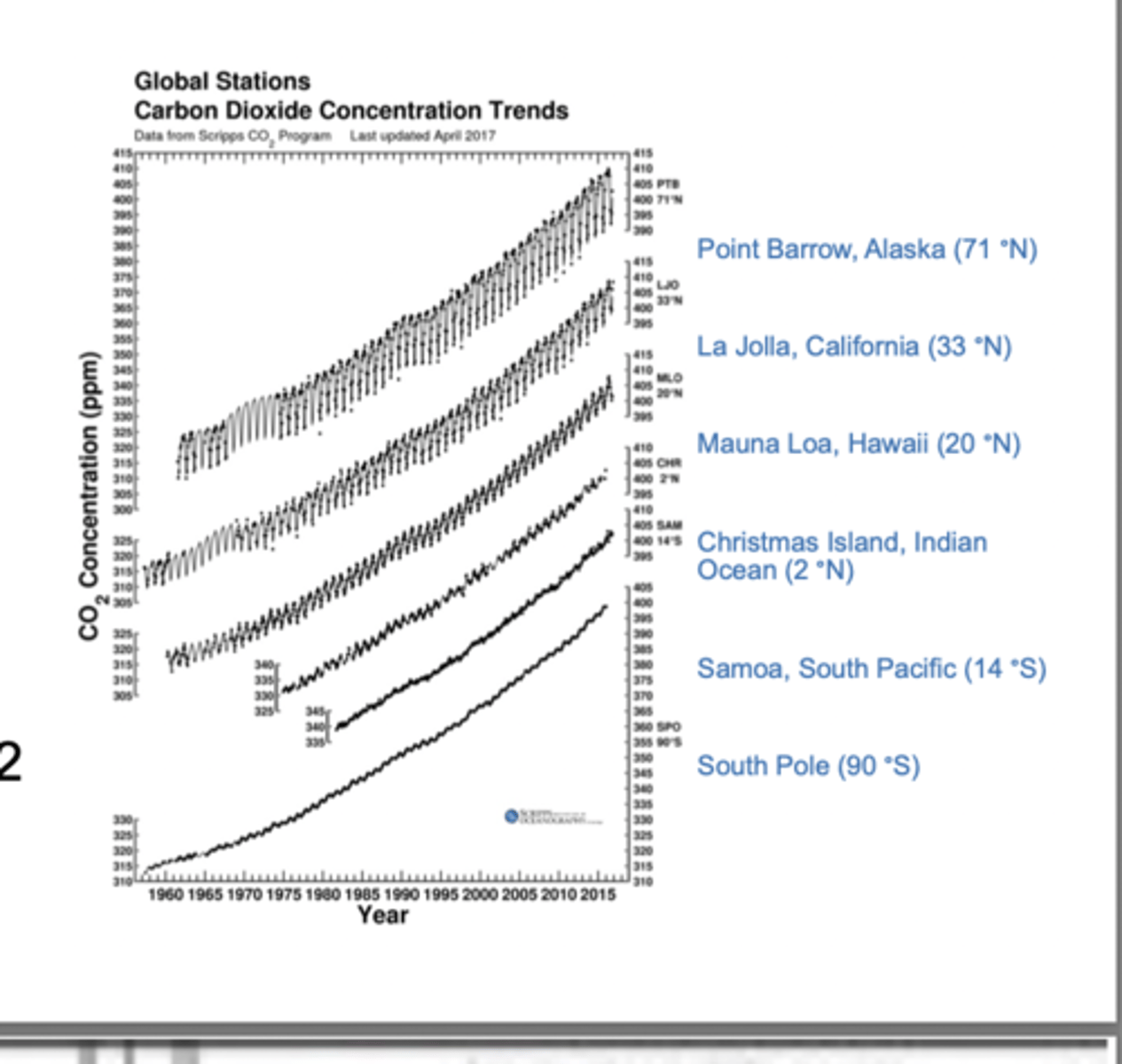

Seasonal patterns in photosynthesis

Because plants absorb CO2 when they photosynthesize, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere drops when photosynthesis is high and rises when photosynthesis is low

CO2 rises during winter

CO2 falls during summer

Seasonal photosynthesis in the Northern Hemisphere vs. the Southern Hemisphere

the NH has larger continents, while the SH is mostly ocean

Because land supports forests and vegetation, the Northern Hemisphere has more trees, more forests, and more seasonal vegetation

This means that seasonal photosynthesis in the NH has a much bigger effect on global CO2 than the SH does

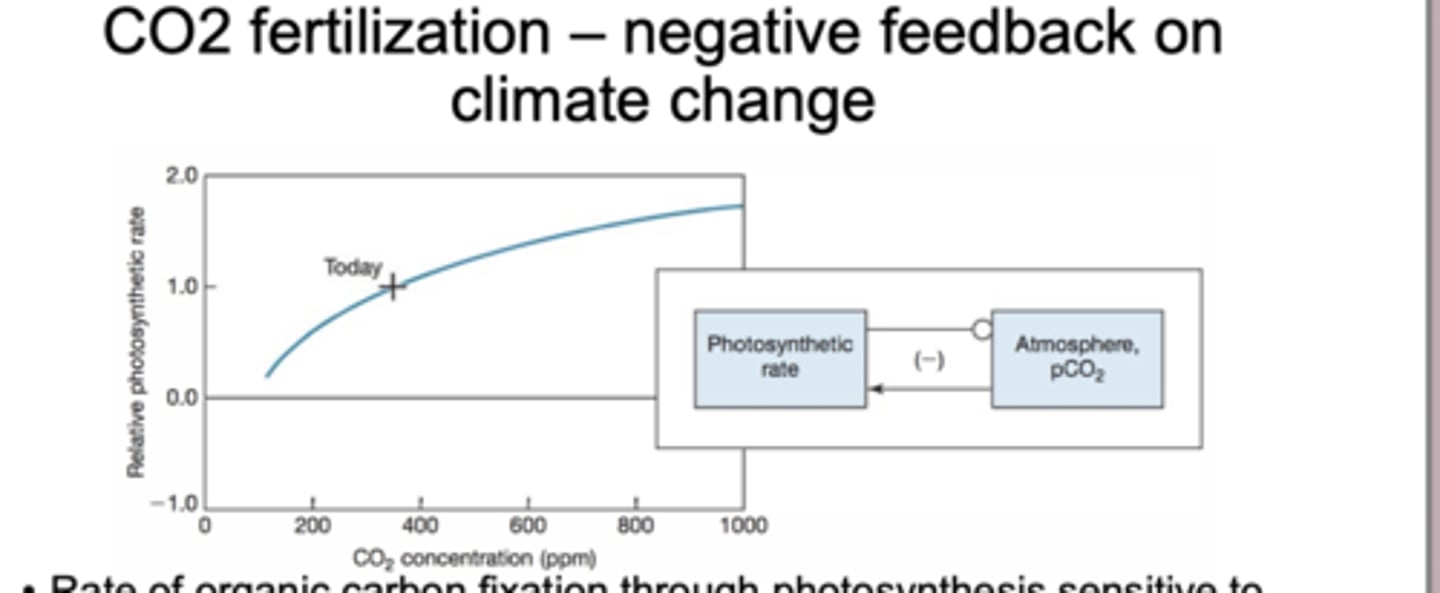

CO2 Fertilization-negative feedback on climate change

CO₂ fertilization is the idea that higher atmospheric CO₂ increases the rate of photosynthesis, which pulls more CO₂ out of the atmosphere. This acts as a negative feedback on climate change because it partially offsets rising CO₂.

Respiration

CH2O+O2=CO2

Respiration is the process by which plants, animals, and microbes break down organic carbon (CH2O) and release CO2 back into the atmosphere

There are two types

1. Aerobic respiration

2. Anaerobic respiration

Aerobic respiration

The type of respiration that humans use, most animals use, most plants at night use, and most microbes use

when oxygen is available

Aerobic respiration is the major source of CO2 return to the atmosphere

Anaerobic respiration

2CH20=CO2+CH4

Respiration that does not require oxygen

Occurs in low oxygen places like wetlands, swamps, deep sediments, landfills, and the guts of cows and termites, often producing methane, a strong greenhouse gas

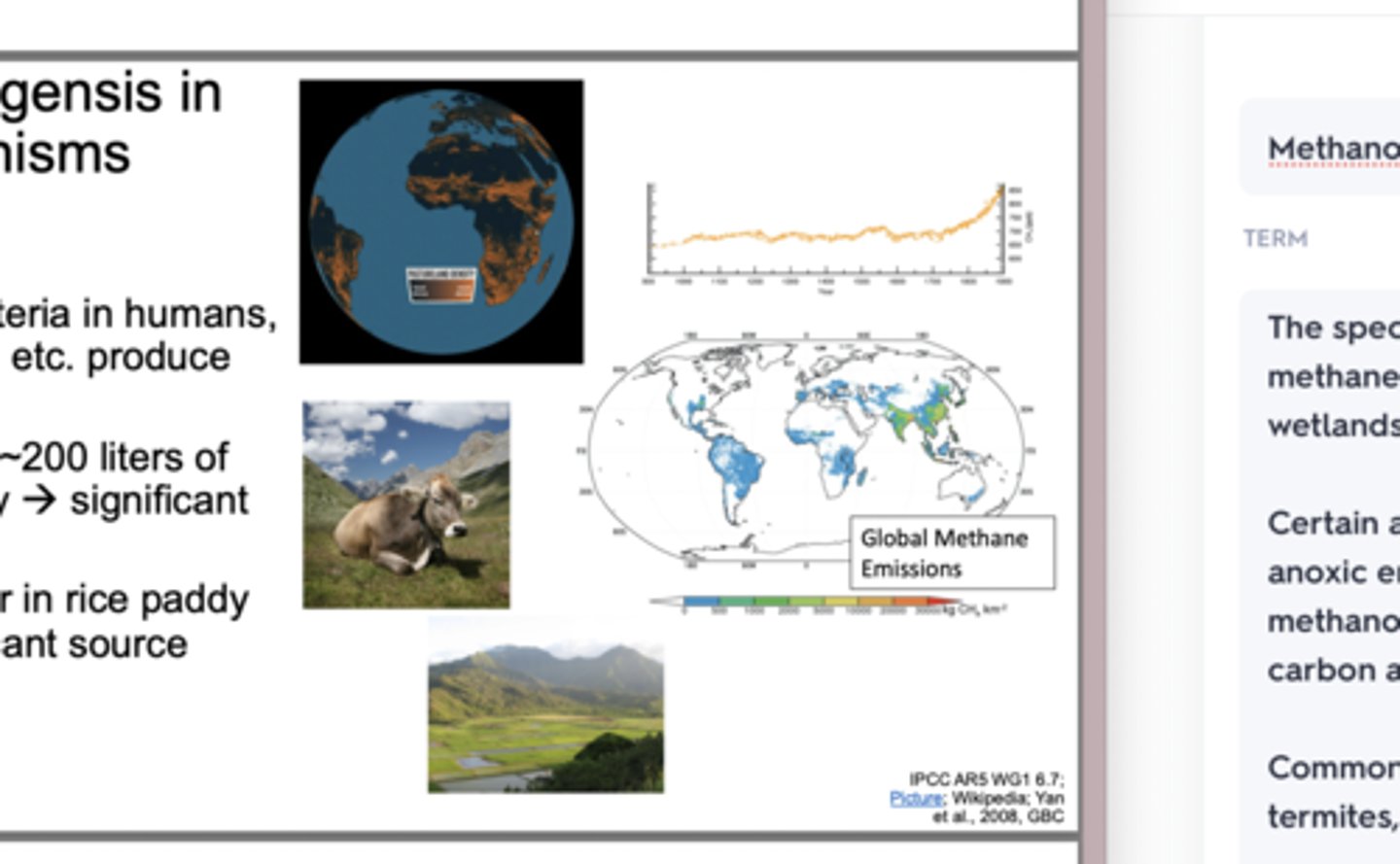

Methanogenesis

The specific anaerobic process that produces methane, is carried out by archaea, and is common in wetlands(rice paddies), sediments, and cow stomachs

Certain animals have digestive systems that critic anoxic environments- inside them are symbiotic methanogenic archaea, which break down organic carbon and release CH4

Common methane producing animals are cows, termites, humans

Cows release around 200 liters of methane a day

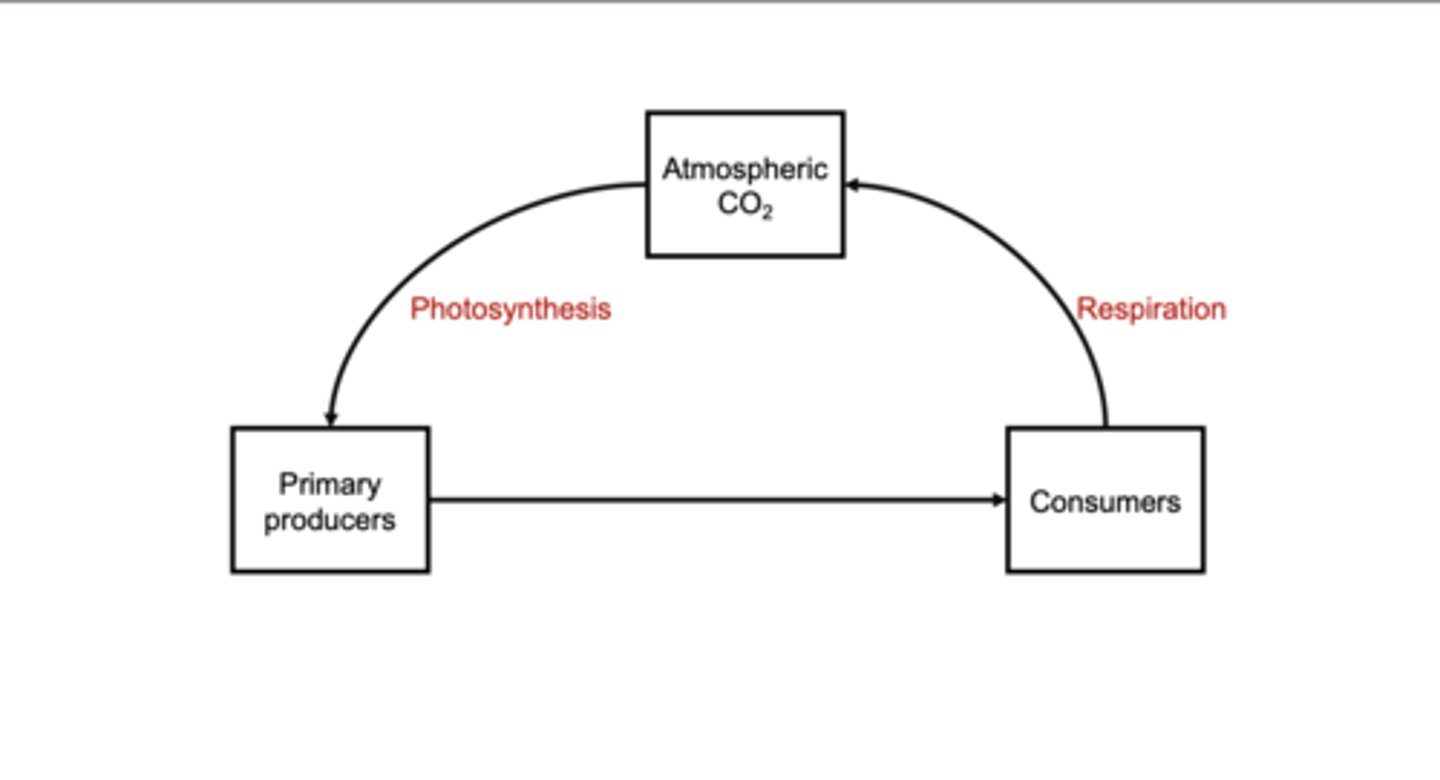

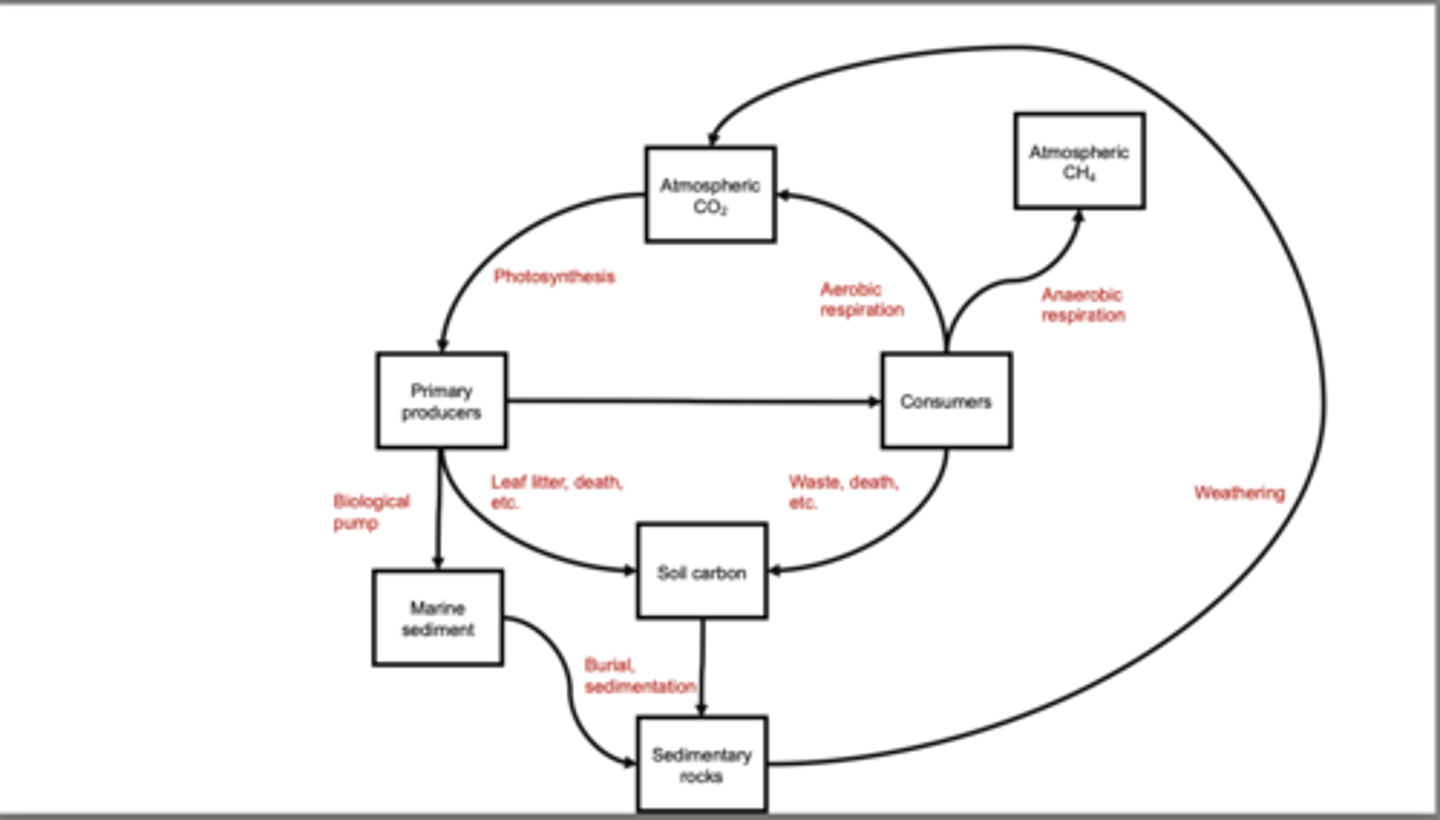

Biological Carbon Cycle

Atmospheric CO₂ is taken up by primary producers during photosynthesis.That organic carbon moves to consumers through feeding.Producers and consumers respire, sending CO₂ back to the atmosphere.

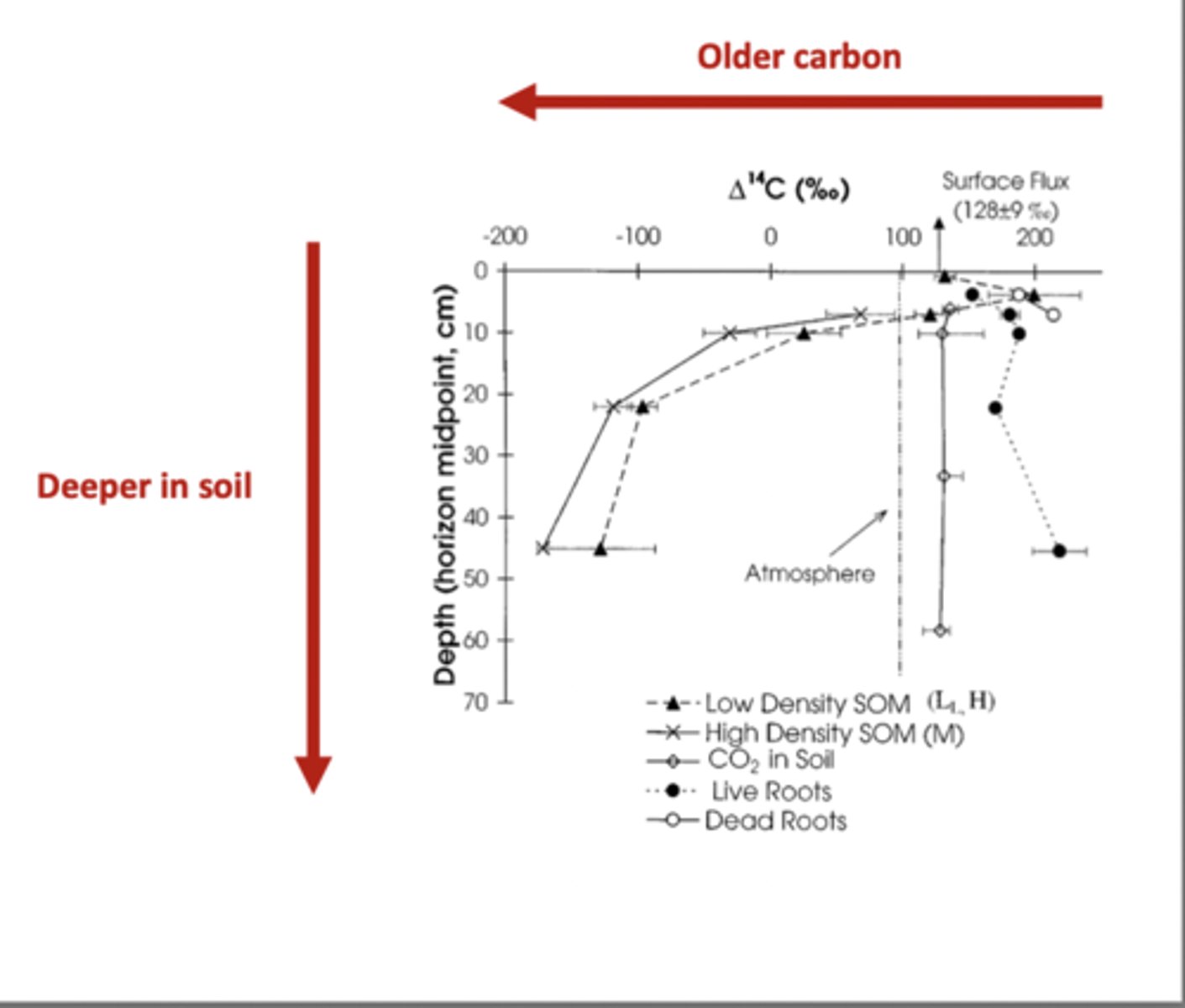

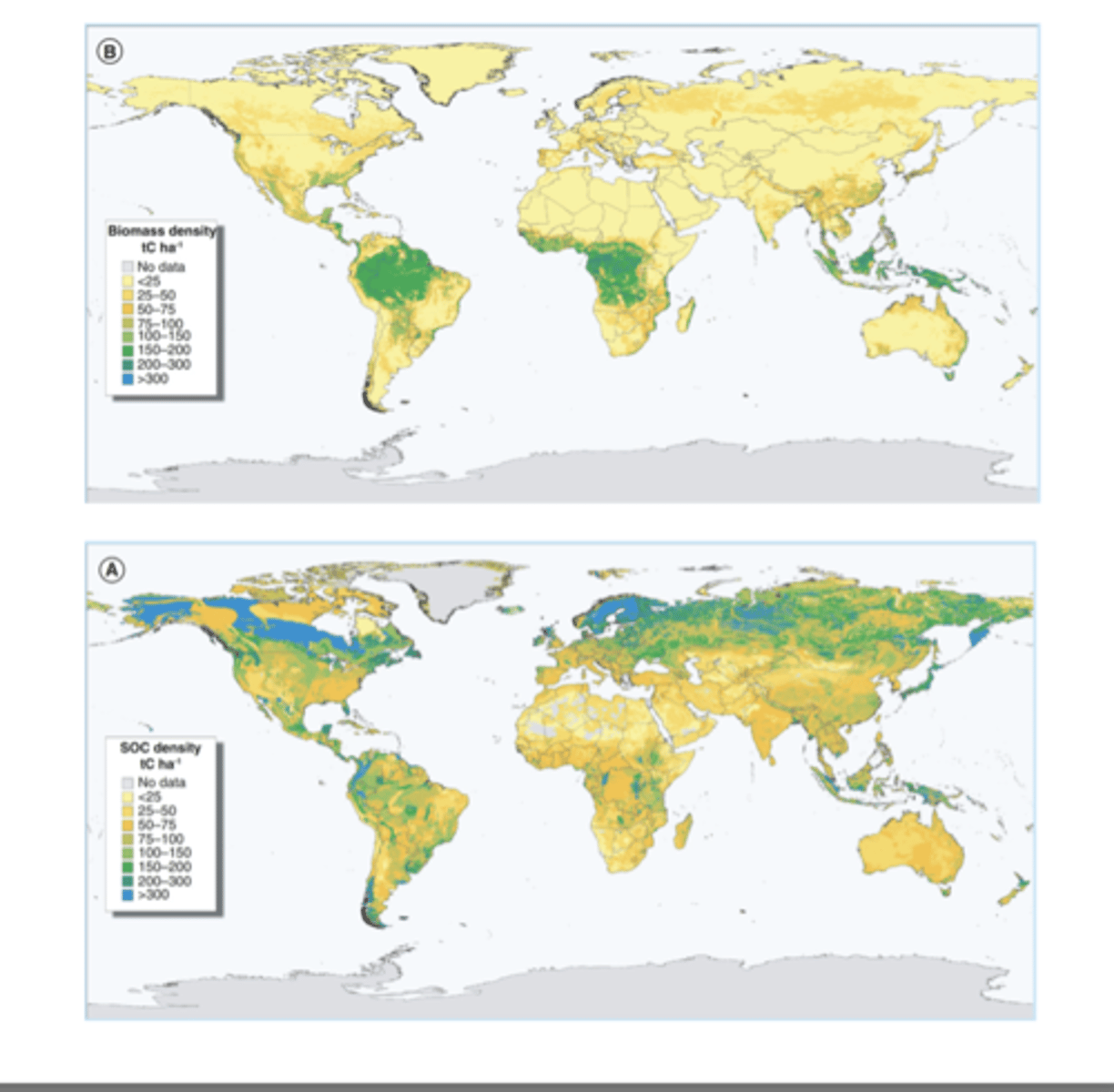

Soil Carbon Reservoir

Soils are on of the largest and most important short to medium term carbon reservoirs on Earth. They store organic carbon that comes from plants and organisms, and they release carbon back into the atmosphere through decomposition and respiration.

Soils store organic carbon from leaf litter, dead roots, decomposed organisms, etc.

Soil Carbon in the High Latitudes

Soil Carbon is highest in the high latitudes even though biomass is highest in the tropics because the tropics decompose matter very fast, while the high latitudes decompose extremely slowly

This is because in cold, high latitudes, soils are frozen and microbes are less active, so lead and dead roots do not break down quickly

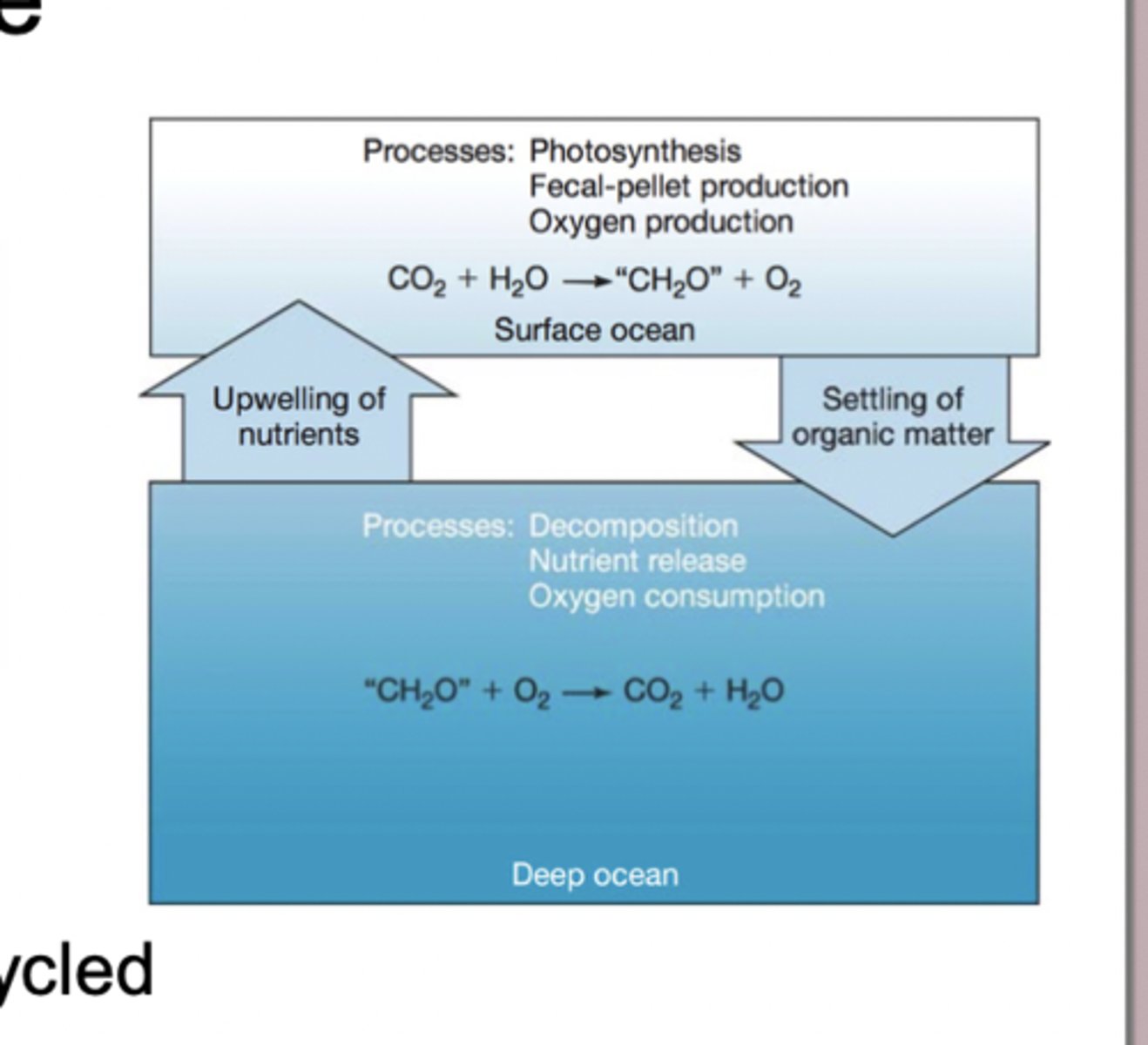

Organic carbon and the marine carbon cycle

In the ocean, the organic carbon cycle works similarly to land, but the organisms are microscopic and the vertical transport of carbon plays a major role

Diatoms, coccolithophorids, and other phytoplankton species in the upper sunlit layer of the ocean photosynthesize by taking up atmospheric and dissolved CO2 and converting it into organic carbon

Phytoplankton are eaten by zooplankton, small fish, and larger marine organisms, and this carbon moves up the marine food web

Waste and organisms fall to the ocean floor and become part of the marine sediment, removing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing carbon in a major long term carbon sink

Diatoms

photosynthetic phytoplankton with silica shells that take up CO₂ through photosynthesis, forming a major part of marine primary production. When they die, their heavy shells help them sink, carrying organic carbon to deeper waters. They are one of the most important drivers of the biological pump.

Coccolithiphorids

tiny phytoplankton covered in calcium carbonate plates and remove CO₂ through photosynthesis. Their carbonate shells sink after death and contribute to deep-sea sediment, storing carbon long-term. They play roles in both the organic and inorganic (carbonate) carbon cycles.

Foraminifera

single-celled organisms with calcium carbonate shells that eat smaller plankton and incorporate carbon into their shells. When they die, their shells sink to the seafloor and form carbonate-rich sediments. They are major contributors to long-term carbon burial in marine sediments.

Zooplankton

small animals that consume phytoplankton and move organic carbon up the food web. They produce carbon-rich fecal pellets that sink rapidly, transporting carbon to deeper waters. Their feeding and vertical migrations help drive the biological pump.

Biological Pump

process by which the surface ocean pulls CO₂ out of the atmosphere through photosynthesis and then moves some of that carbon into the deep ocean, where it can be stored for long periods of time. process by which the surface ocean pulls CO₂ out of the atmosphere through photosynthesis and then moves some of that carbon into the deep ocean, where it can be stored for long periods of time.

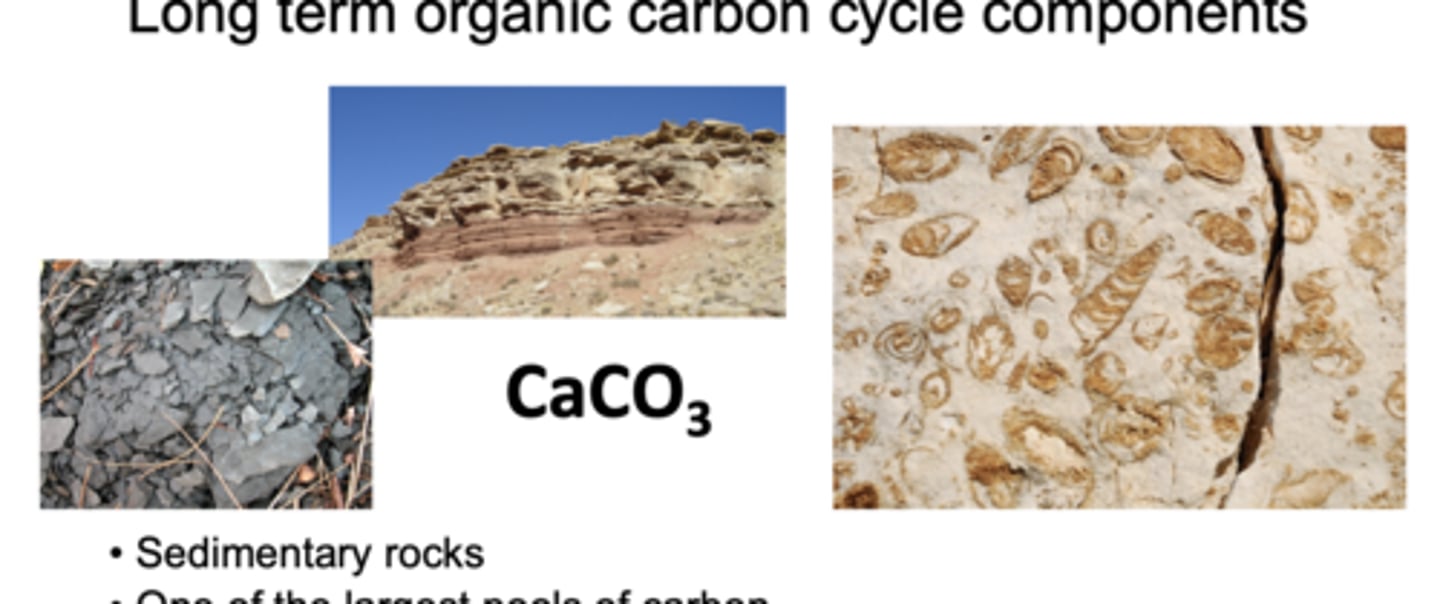

Long term organic carbon cycle components

Calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) is a major component of the long-term carbon cycle because it forms sedimentary rocks such as limestone and chalk when the shells and skeletal material of marine organisms accumulate on the seafloor and become buried over millions of years. This rock reservoir represents one of the largest pools of carbon on Earth, far exceeding the amount stored in the atmosphere, vegetation, or even the deep ocean.

As CaCO₃ slowly forms and dissolves through geological processes like sedimentation, weathering, and tectonic uplift, it regulates atmospheric CO₂ concentrations over extremely long time scales, acting as a stabilizing force in Earth's climate system. This process is slow and only important over geologic time, not short-term climate change.

Biological Pump

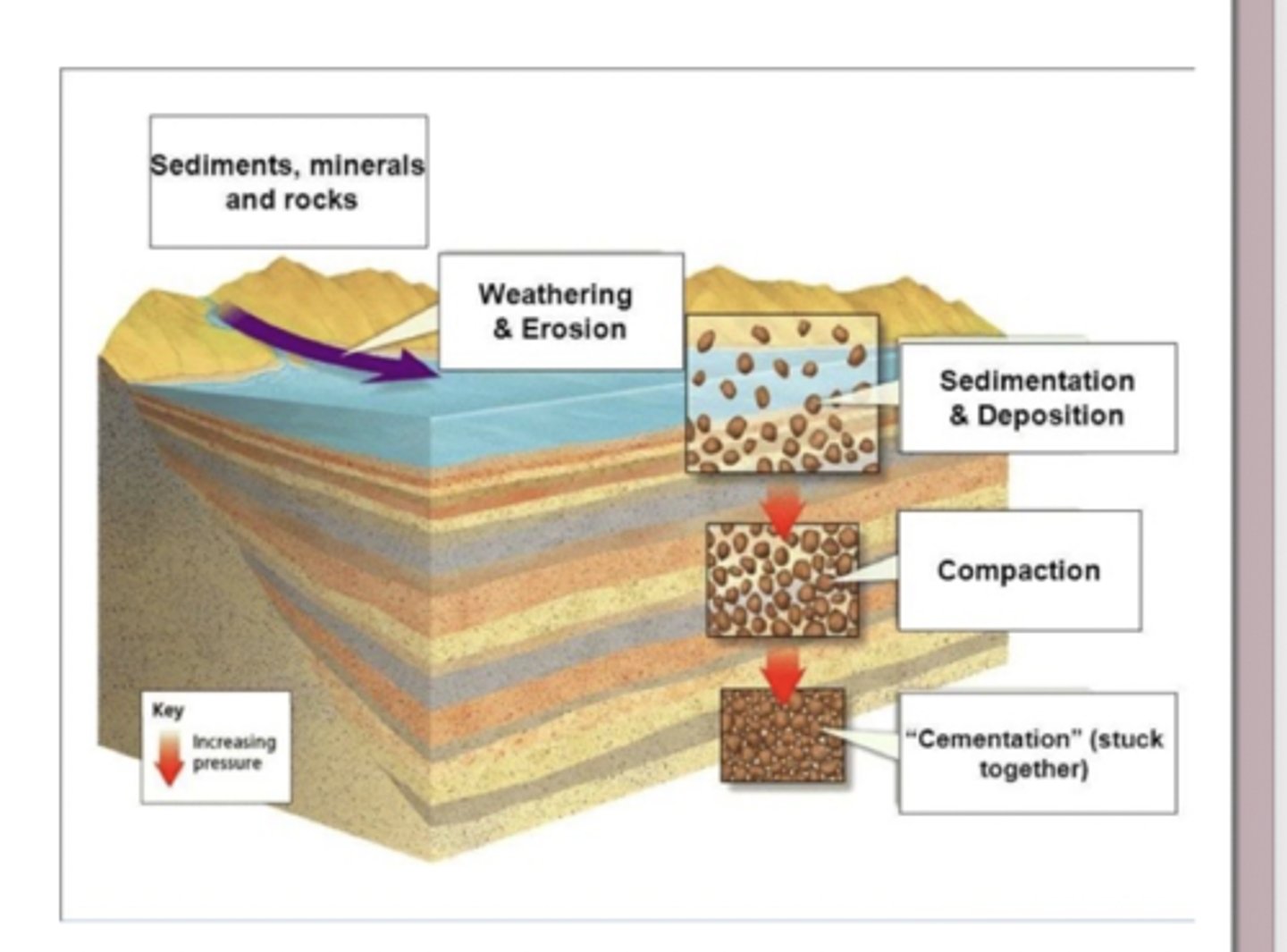

Over millions of years, the organic material and carbonate shells that sink to the ocean floor accumulate in thick layers of sediment. As more sediment builds up on top, pressure and chemical processes compact and cement these layers, eventually turning them into sedimentary rock—this is how the carbon that originated from living organisms becomes permanently locked into Earth's crust. This burial represents a slow "leak" from the short-term carbon cycle, where carbon moves quickly between the atmosphere, living things, and surface ocean, into the long-term geological carbon cycle that stores carbon for millions of years. When this carbon is buried, the oxygen originally released during photosynthesis stays in the atmosphere, which is one of the reasons Earth's atmosphere contains abundant O₂ even though much of the carbon from ancient photosynthesis is no longer cycling at the surface.

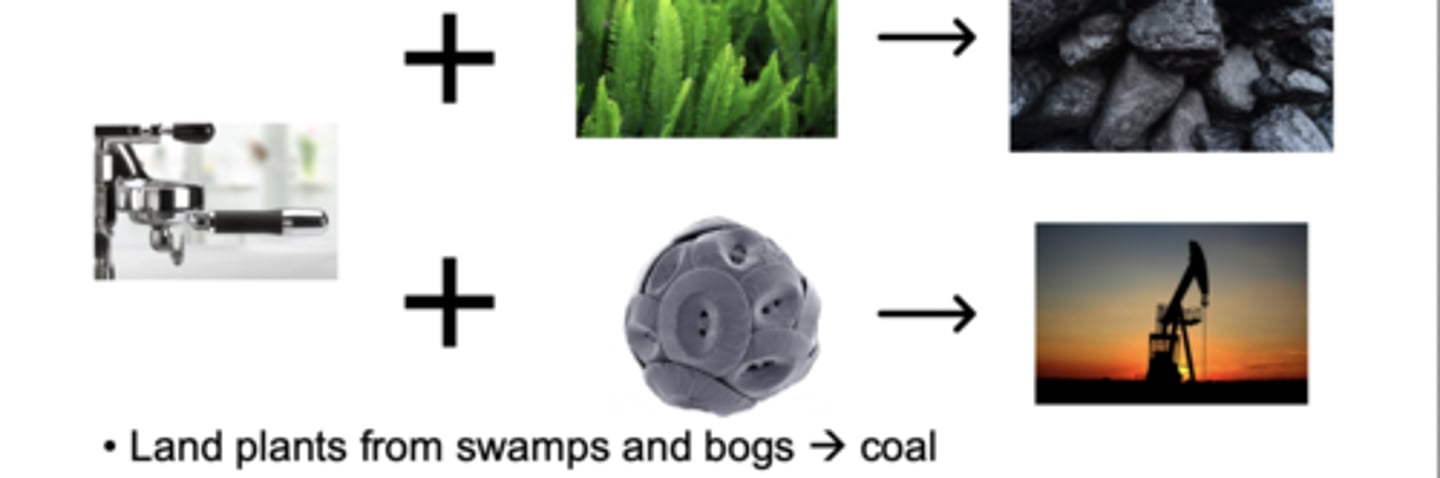

Creation of fossil fuels from sedimentary rocks

Fossil fuels form when organic carbon from long-dead organisms becomes buried, heated, and compressed inside sedimentary rocks over millions of years. Coal originates from land plants that accumulated in ancient swamps and bogs; when this thick, oxygen-poor plant material was buried and subjected to pressure and heat, it transformed into coal. In contrast, petroleum (oil) and natural gas come from marine organic matter—primarily microscopic plankton like coccolithophores and other algae. When these organisms died, they sank into ocean sediments, where low-oxygen conditions prevented full decomposition. Over geological timescales, burial, pressure, and heat chemically altered this marine organic carbon into oil and gas. In both cases, the key idea is that biological carbon “leaks” from the short-term cycle into deep burial, eventually becoming fossil fuels stored in sedimentary rocks.

Summary of the organic carbon cycle

1. Atmospheric CO₂ is taken up by primary producers through photosynthesis.

2. Primary producers are consumed by consumers, transferring organic carbon through the food web.

3. Consumers release CO₂ back to the atmosphere through aerobic respiration.

4. Some consumers release CH₄ through anaerobic respiration in oxygen-poor environments.

5. Dead organic matter from producers and consumers (leaf litter, waste, carcasses) enters the soil carbon pool.

6. Soil carbon may remain stored temporarily or begin to be buried.

7. Some soil carbon is transported to the ocean and becomes part of marine sediment.

8. Marine primary producers also sink after death, adding carbon to marine sediments via the biological pump.

9. Marine sediments become buried and compacted over millions of years, forming sedimentary rock.

10. Sedimentary rocks store carbon on long geological timescales.

11. Weathering of sedimentary rocks slowly releases CO₂ back to the atmosphere, closing the long-term cycle.

Components of the inorganic carbon cycle

1. Atmospheric CO2

2. Dissolved CO2 in ocean water

3. Carbonate rocks (have carbon atom) and silicates rocks(have silica atom)

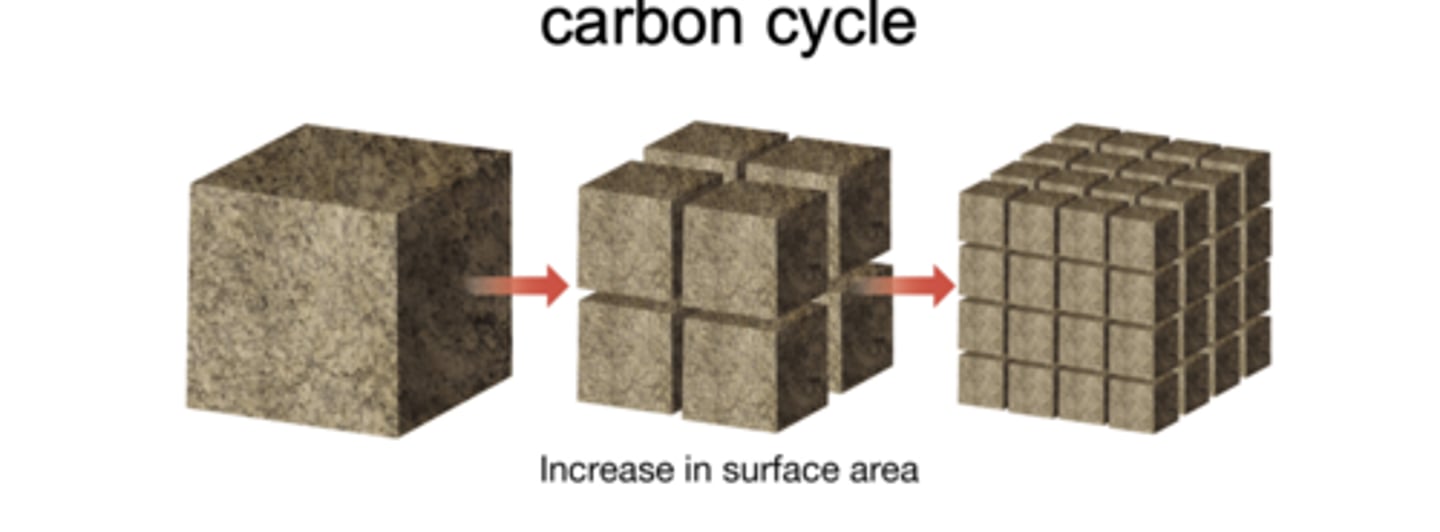

Weathering

The breakdown of rocks at Earth's surface into smaller particles or dissolved ions, which increase the rock's surface area and accelerates chemical reactions. It can occur through chemical, physical, or biological processes.

Weathering is essential to the inorganic carbon cycle because it removes CO₂ from the atmosphere: carbon dioxide reacts with water to form carbonic acid, which dissolves silicate and carbonate rocks. This dissolved material is transported to the ocean, where it ultimately becomes part of carbonate minerals and sedimentary rocks, storing carbon on million-year timescales.

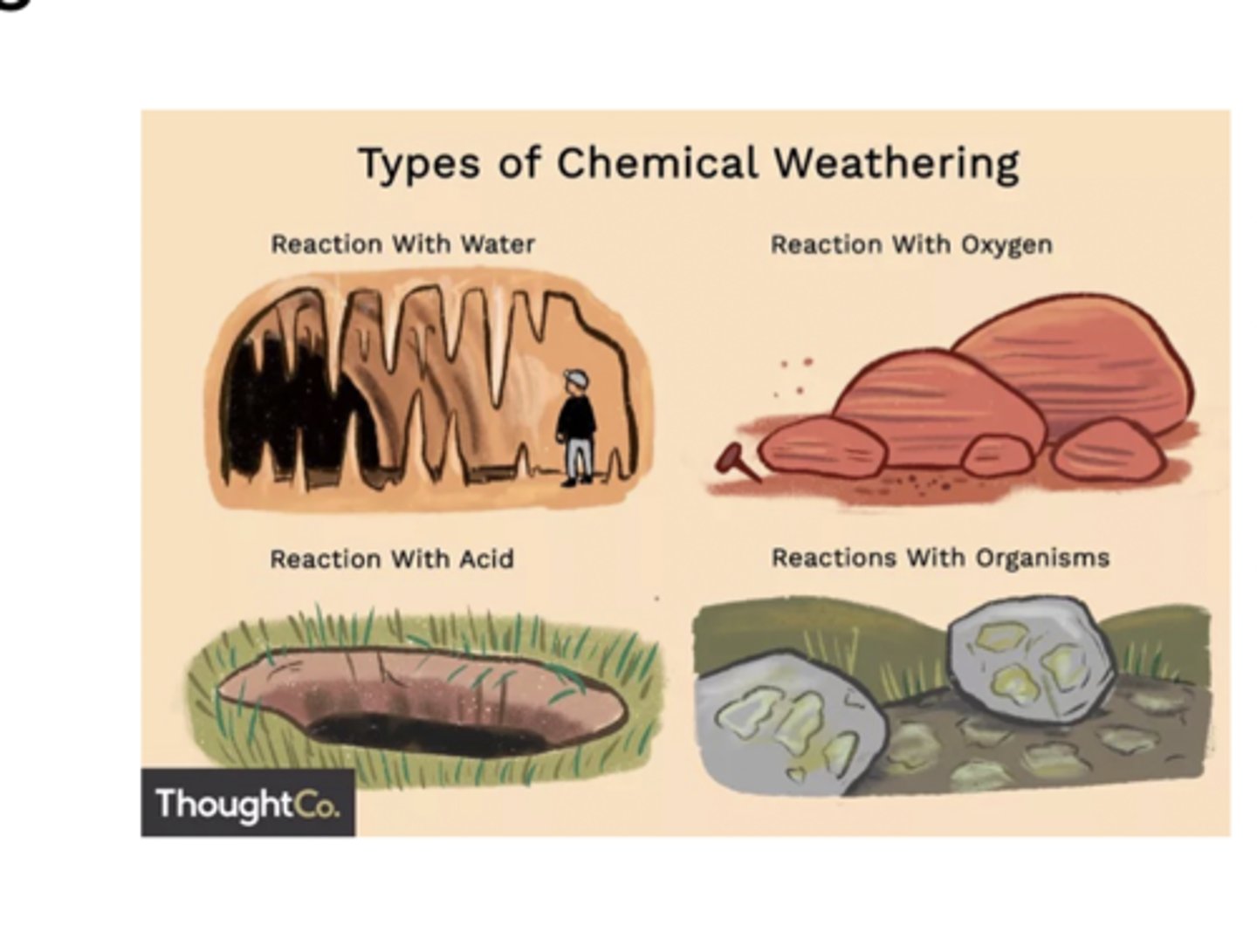

Chemical Weathering

The process that breaks down rock through chemical changes

This process is driven by several agents, including water, organic acids from plants and soil, acid rain, and oxygen. These chemicals react with minerals in the rock, weakening them, breaking them apart, or dissolving them into ions that can be carried away by water. Chemical weathering is a major component of the inorganic carbon cycle because reactions between CO₂, water, and rock help remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere over long timescales.

Calcium Silicate Weathering and Carbonate Precipitation

Calcium silicate weathering removes CO₂ from the atmosphere because rainwater combines with atmospheric CO₂ to form carbonic acid (H₂CO₃), which chemically weathers silicate rocks on land.

This weathering reaction consumes twoCO₂ molecules as it breaks down silicates and releases calcium ions (Ca²⁺) and bicarbonate ions (HCO₃⁻).

Rivers carry these ions to the ocean, where they undergo carbonate precipitation: Ca²⁺ + HCO₃⁻ → CaCO₃ (calcium carbonate).

This process releases one CO₂ molecule, but because weathering consumed two, the net effect is long-term CO₂ removal. The precipitated CaCO₃ becomes shells and eventually forms carbonate rocks, locking carbon away for millions of years and linking land-based silicate weathering to ocean carbonate formation.

Carbon Cycle Moderating Long Term Climate Change

If CO₂ is too high → weathering removes CO₂ faster → cools the planet.

If CO₂ is too low → weathering slows → volcanoes dominate → CO₂ rises → warms the planet.

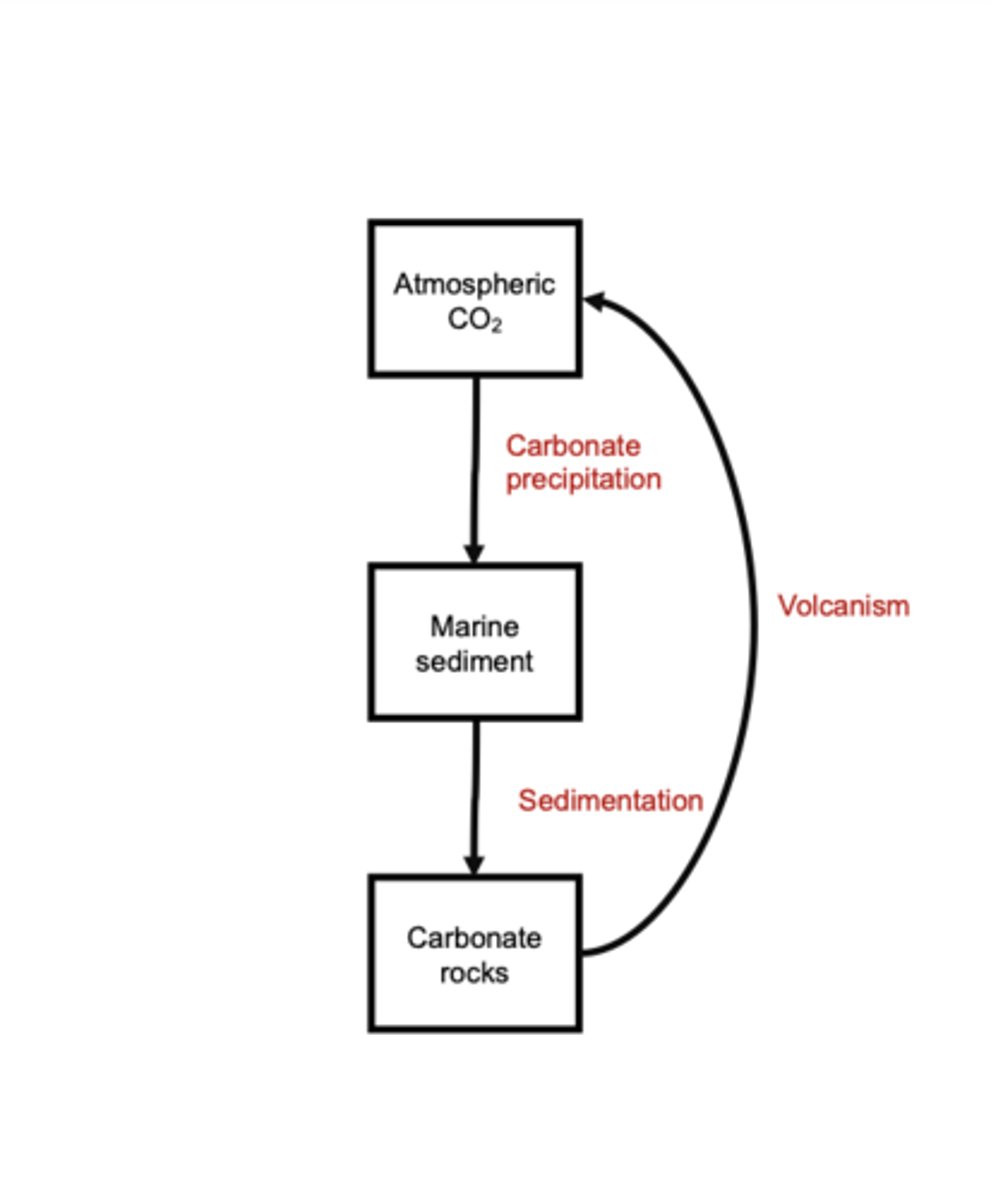

The Long Term Inorganic Carbon Cycle Summary

Atmospheric CO₂ dissolves into the ocean and is converted into carbonate minerals through carbonate precipitation. These carbonate-rich marine sediments are buried and compacted into carbonate rocks through sedimentation. Over millions of years, tectonic subduction and metamorphism return this stored carbon to the atmosphere as volcanic CO₂. This closed loop acts as a major long-term regulator of atmospheric CO₂ and climate.

Connecting the Organic and Inorganic Carbon Cycles

Earth's organic carbon cycle (photosynthesis, respiration, decomposition, soil carbon, and organic sediment burial) is linked to the inorganic carbon cycle (carbonate formation, rock weathering, sedimentation, and volcanic CO₂ release). Atmospheric CO₂ acts as the central connector between both cycles: it is taken up by primary producers through photosynthesis in the organic cycle and also participates in carbonate precipitation in the inorganic cycle. Biology accelerates silicate rock weathering by producing organic acids and increasing CO₂ in soils, which speeds up long-term removal of CO₂. The biological pump transfers organic carbon from the surface ocean to deep sediments, enhancing CO₂ burial. Together, these processes integrate fast biological carbon movement with the slow geologic carbon cycle, regulating Earth's atmosphere over short and long timescales.

Summary of the Carbon Cycle

The carbon cycle moves carbon through the atmosphere, biosphere, oceans, and solid Earth on multiple timescales. In the fast, short-term organic carbon cycle (days to years), CO₂ is taken up by plants and phytoplankton through photosynthesis, moved through food webs, and rapidly returned to the atmosphere by respiration. A slower component of the short-term cycle occurs over decades to centuries, as carbon is stored in soils, deep ocean waters, and dissolved inorganic carbon pools before being gradually released back to the atmosphere or transported to the deep ocean by the biological pump. The long-term geologic carbon cycle operates over 10⁴–10⁶+ years: weathering of silicate rocks removes CO₂ from the atmosphere and delivers ions to the ocean where marine organisms form CaCO₃ shells that become carbonate sediments and eventually carbonate rocks. Through plate tectonics and subduction, these rocks are buried, heated, and return CO₂ to the atmosphere via volcanism. Together, the fast and slow components of the short-term cycle and the very slow geologic cycle regulate atmospheric CO₂ and Earth’s climate over both immediate and geological timescales.

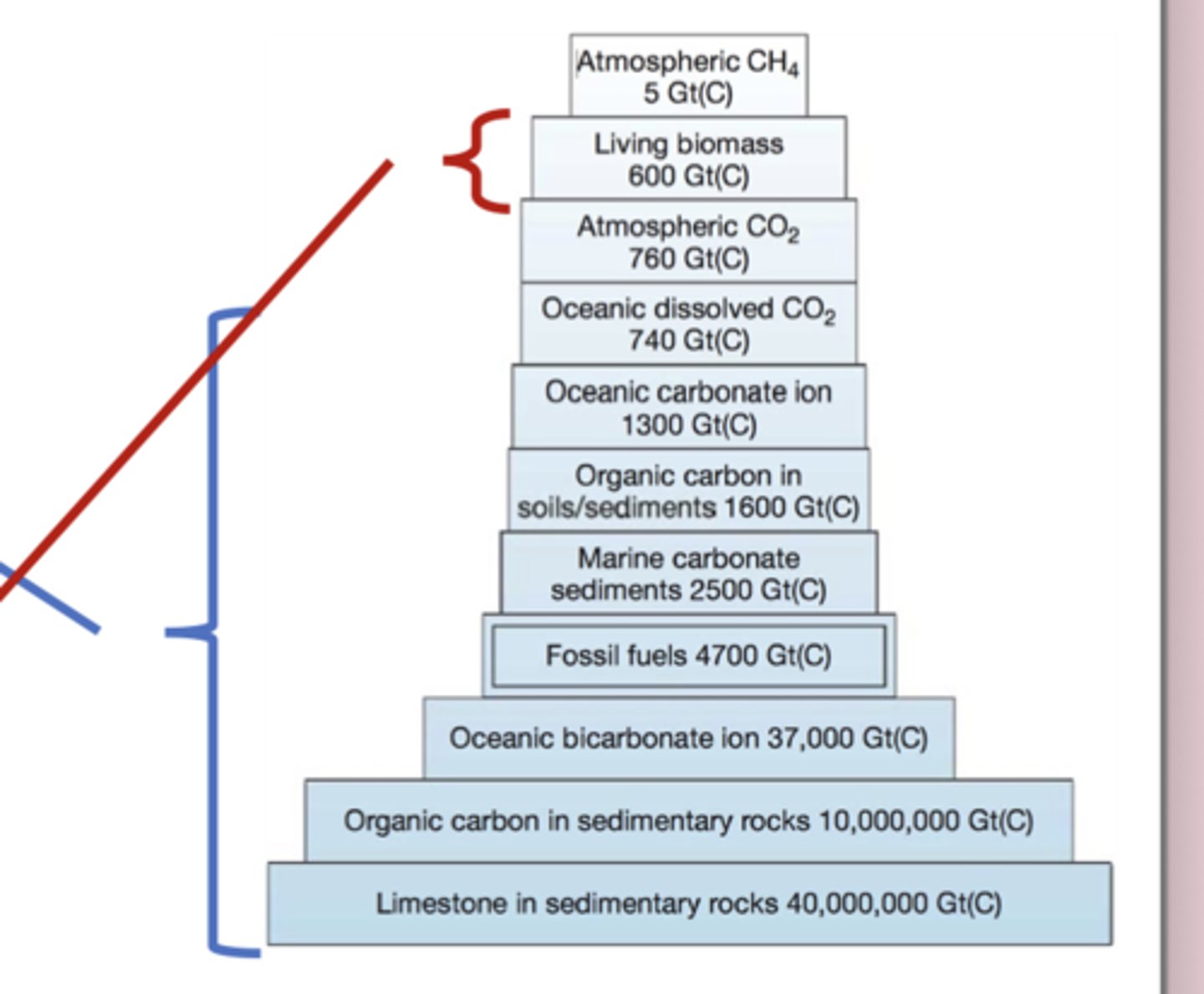

Reservoirs of Carbon

The physical Earth—meaning rocks, sediments, and the deep ocean—contains by far the largest carbon reservoirs, so carbon moves through these parts of the cycle extremely slowly (thousands to millions of years). In contrast, the biological reservoirs—living biomass, soil carbon, and atmospheric CO₂—are small but turn over very quickly, responding to changes in years to centuries. Because the biological component is so fast, it plays a major role in modern climate change, since human emissions immediately alter atmospheric CO₂, photosynthesis, respiration, and ocean–atmosphere exchange, long before the slow geological reservoirs can respond.

Human Alterations to the Global Carbon Cycle

Fossil fuel burning transfers carbon that was locked in sedimentary rocks and fossil fuels into the atmosphere as CO₂, dramatically increasing atmospheric concentrations.

Land-use change, including deforestation, agriculture, and forest fires, reduces the amount of carbon taken up by primary producers and releases stored carbon from vegetation and soils.

In addition, anthropogenic methane emissions from sources such as cows and rice paddies increase atmospheric CH₄, another potent greenhouse gas produced by anaerobic respiration.

Together, these human activities accelerate carbon release and disrupt the natural balance between photosynthesis, respiration, burial, and weathering, leading to rising atmospheric CO₂ and CH₄ levels and driving modern climate change.

Soil

A mixture of fragmented and weathered grains of minerals and rocks with variable proportions of air and water; the mixture has a fairly distinct layering; and its development is influenced by climate and living organisms

6 Functions of soil

1. Medium for plant growth

2. Regulates water resources

3. Recycles nutrients

4. Modifies the atmosphere

5. Habitat for organisms

6. engineering medium

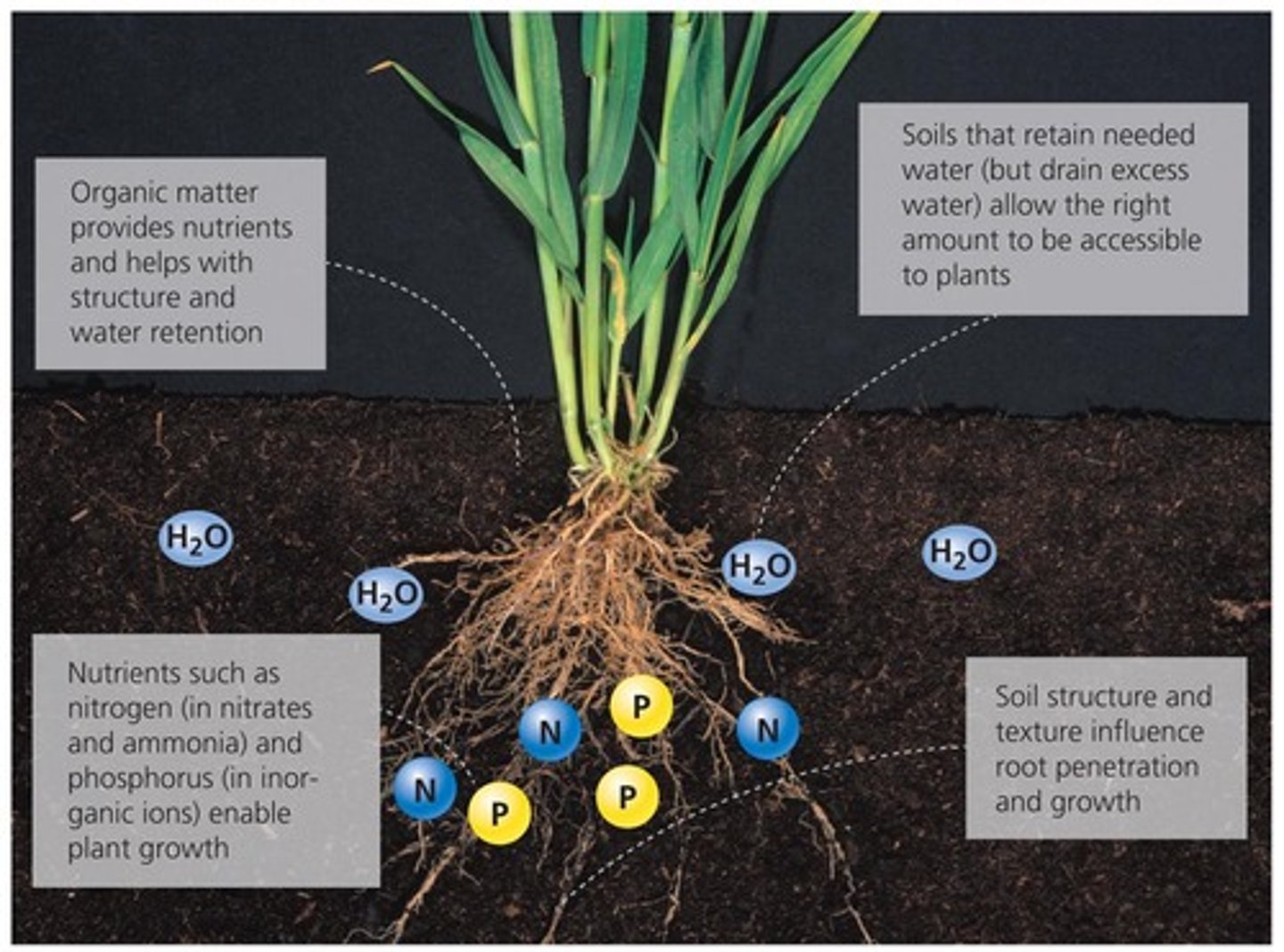

medium for plant growth

providing physical support, water, and nutrients to vegetation

regulates water resources

controlling infiltration, storage, and movement of water through the landscape

recycles nutrients

through decomposition and mineralization, making essential elements available for plants and microorganisms

modifies the atmosphere

by exchanging gases like CO₂, O₂, and CH₄ through respiration and microbial processes

habitat for organisms

including bacteria, fungi, insects, and burrowing animals

engineering medium

supporting the foundations of buildings, roads, and other infrastructure

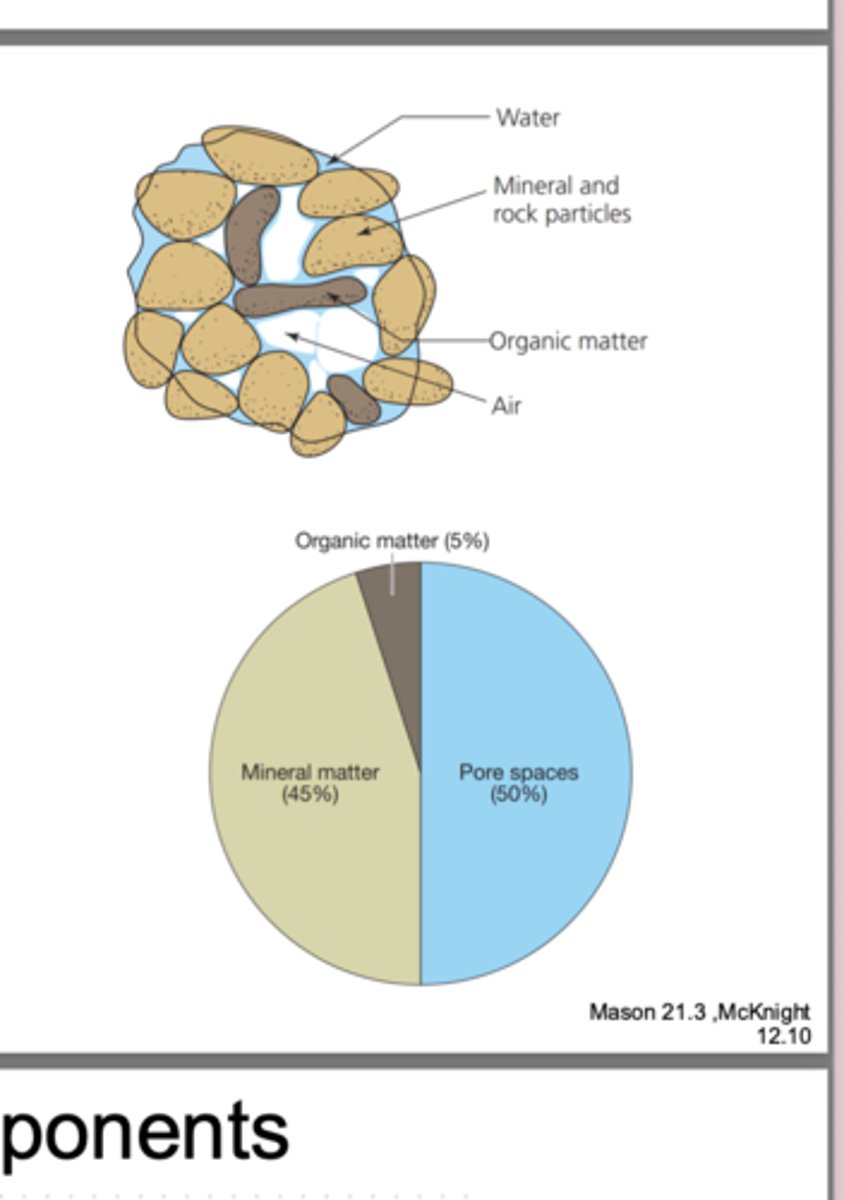

Soil is a mixture of

minerals(45%), organic matter(5%), water, air

half of soil is empty! (50%)

minerals

compounds with a crystalline structure that make up 45% of soil

organic matter

compounds from living organisms that make up 5% of soil

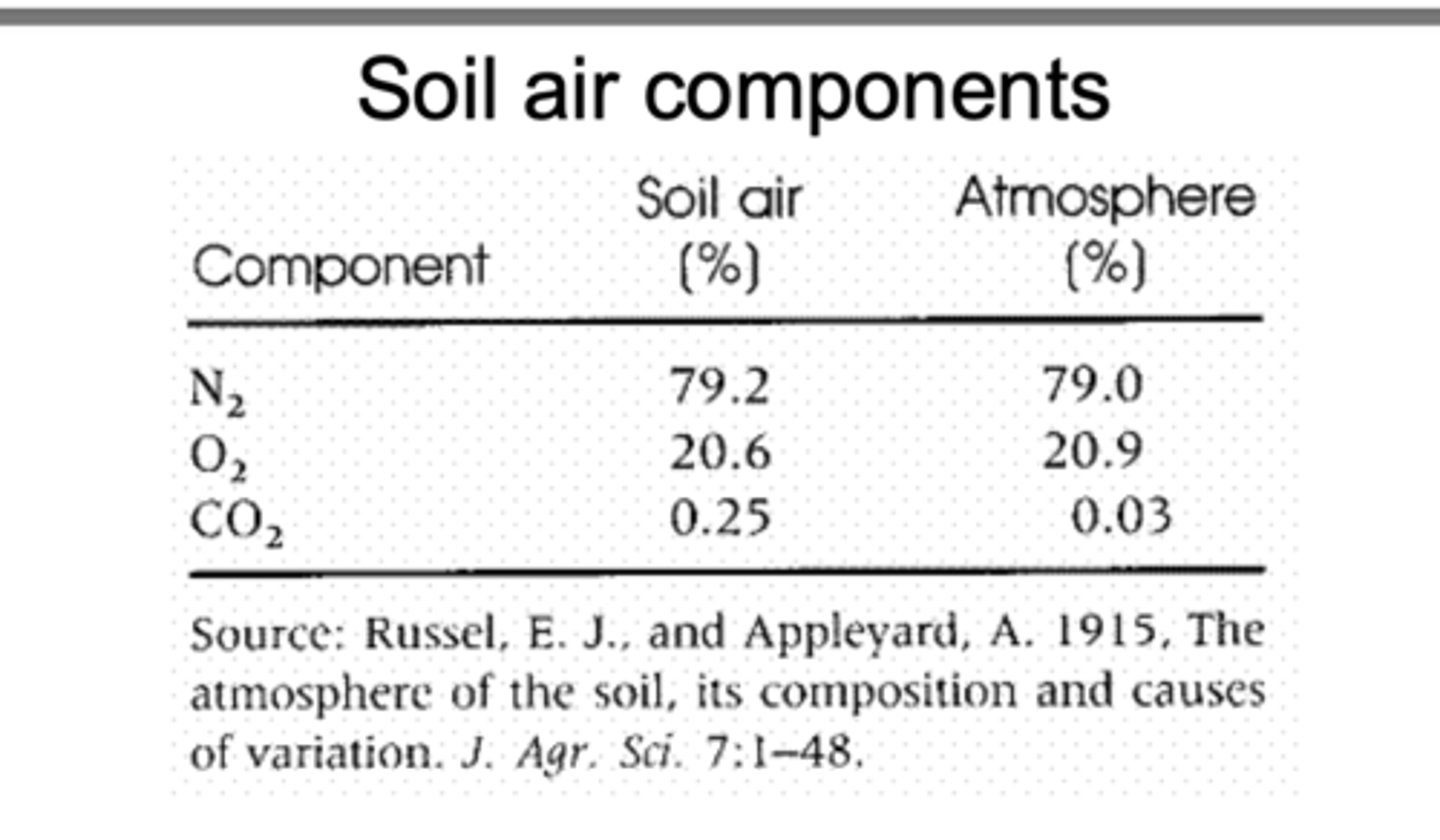

Soil Air Components

Soil contains its own “mini-atmosphere” in the pore spaces between soil particles, and that air is made up of nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide, but in different proportions than the outside atmosphere.

Soil Air

N2- 79.2%

O2- 20.6%

CO2- 0.25%

Atmosphere

N2- 79%

O2-21%

CO2-0.03%

Soil air has much higher CO₂ and lower O₂ than atmospheric air because plant roots and soil microbes continuously respire, consuming oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide. When soils become water-logged, water fills the pores and prevents oxygen from diffusing in. This creates anaerobic (low-oxygen) conditions, which can change biochemical processes in the soil, reduce decomposition rates, and increase methane production.

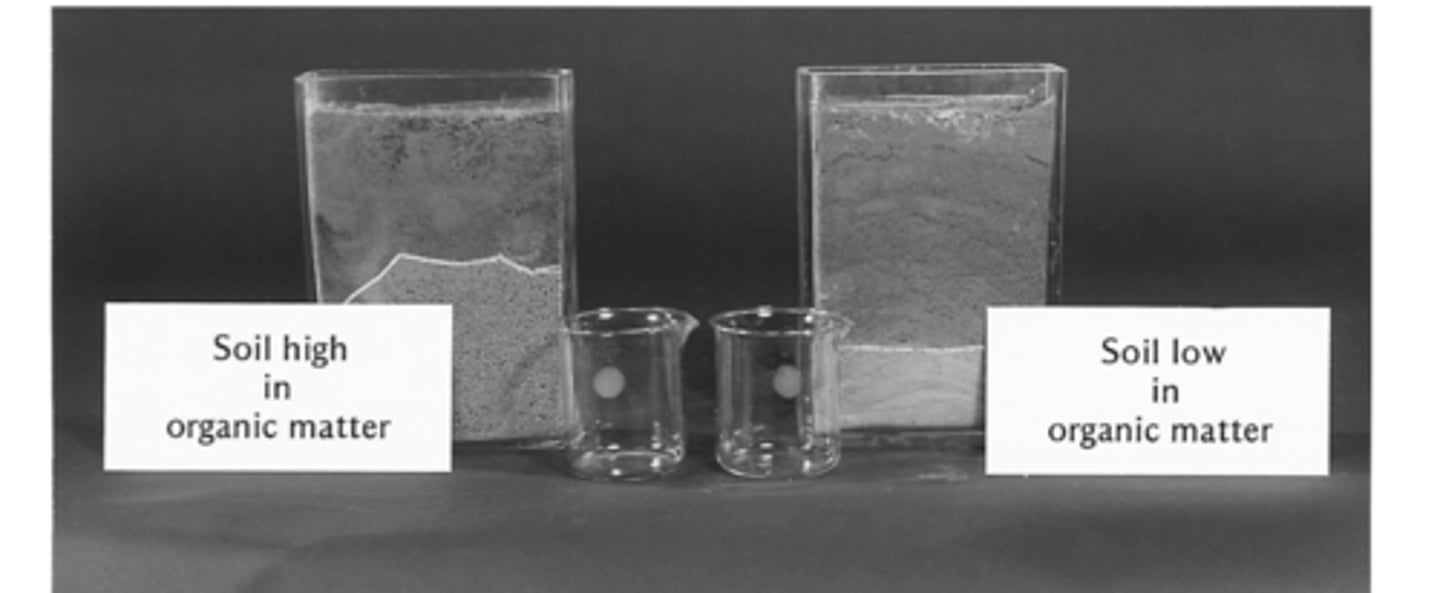

Organic matter in soil alters physical properties of soil

Soil with more organic matter has a greater water holding capacity, creating favorable conditions for plants and animals because its easier for roots to grow and for microbes to function

How is soil formed?

Soil forms by weathering, which is the breakdown of rocks and minerals by

Chemical processes (reactions with water, acids)

Aeolian processes (wind)

Fluvial processes (rivers & water movement)

Biological processes (roots, microbes, lichen)

The 5 Soil Forming Factos (CLORPT)

Climate

Organisms

Relief and Topography

Parent material

Time

Soil forming factors control...

the formation of soil type

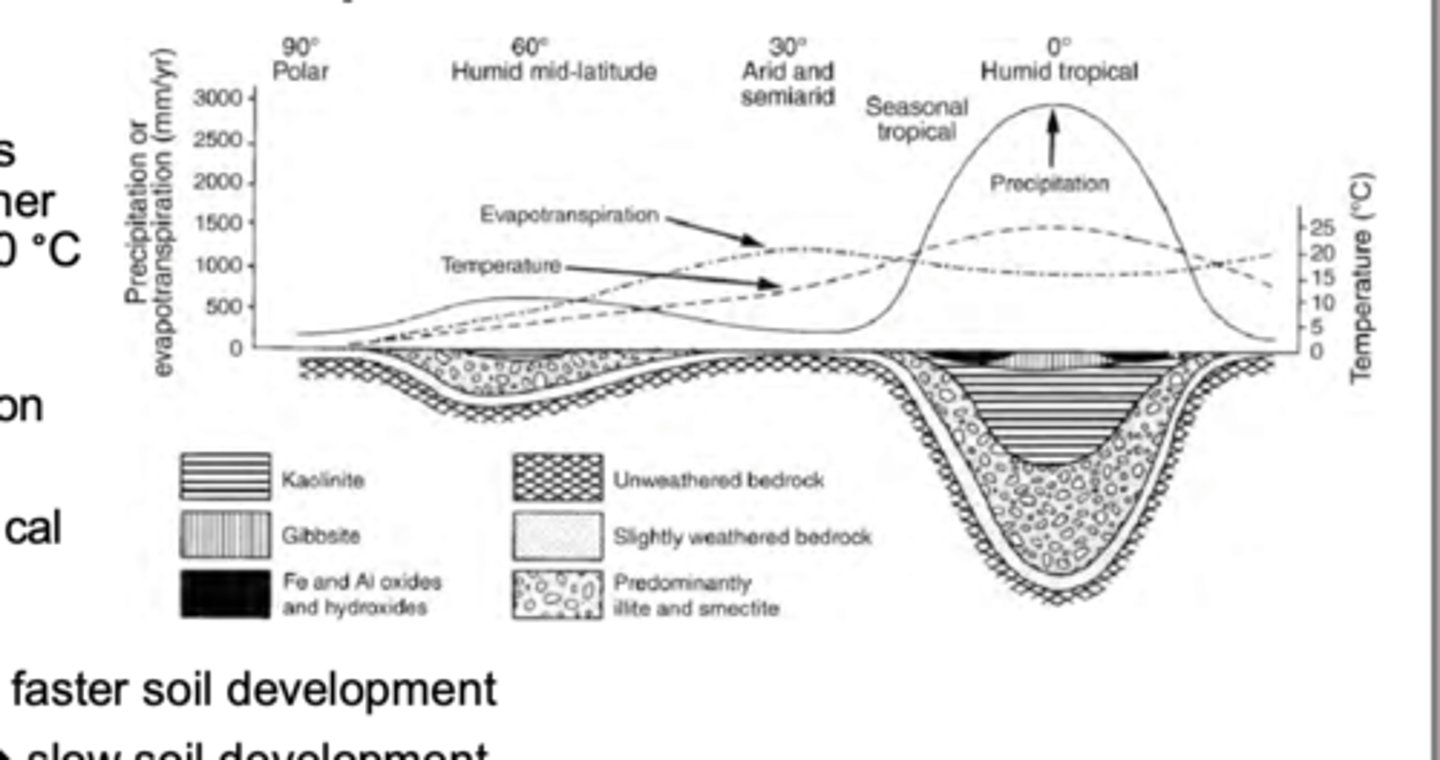

Climate

climate=temperature + precipitation

Chemical reactions occur faster in higher temperatures (a 10 degree C increase in temperature doubles the rate of of a biochemical reaction)

Chemical reactions occur faster in water

Therefore, hot/wet climates have faster soil development and cold/dry climates have slow soil development

Organisms

Soil organic matter mainly comes from dead plant roots and leaves, and burrowing organisms help mix this material into the soil; the acidity of the organic matter controls how fast it decomposes, and the end product of this decomposition is humus, a dark, nutrient-rich, stable material that greatly improves soil fertility.

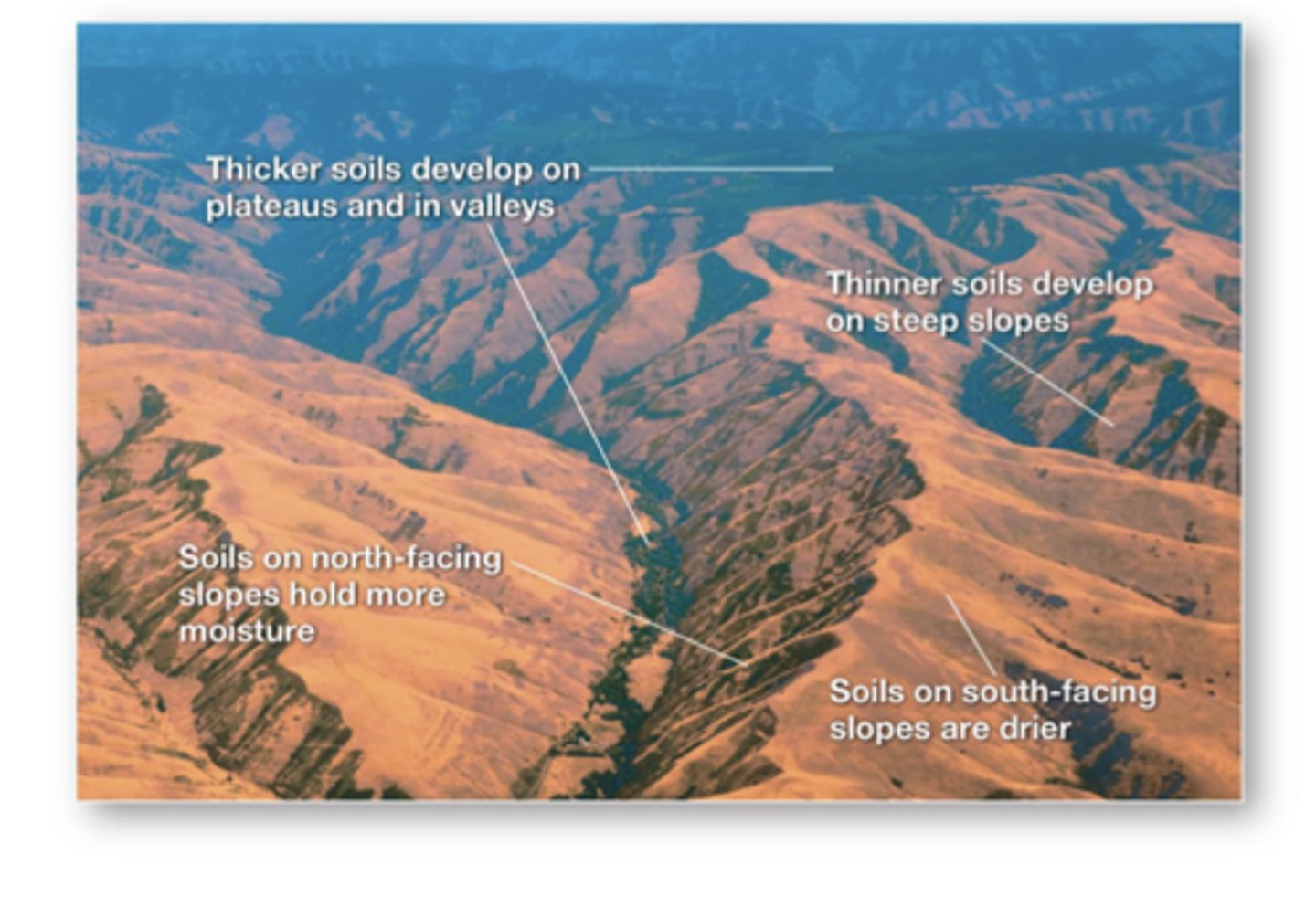

Relief and Topography

Elevation, slope, and aspect can slow or speed climate factors.

There is more erosion on slopes, so there is thinner soil. In contrast, in valleys, there is a collection of sediment, so there is thicker soil.

Soils on north facing slopes hold more moisture and soils on south facing slopes are drier.

Soil Catena

A soil catena is a sequence of different soil types along a hill formed by topography. All soil-forming factors are the same except slope position. Water moves downslope, creating dry, thin soils upslope, moderate soils mid-slope, and thick, organic-rich soils at the base.

Parent Material

Parent material refers to the original geologic or organic material from which a soil develops. These precursors can be organic (like plant debris or peat) or geologic (like basalt, limestone, quartz sand). The chemical composition of the parent material largely determines the chemical composition of the resulting soil, because weathering breaks down whatever minerals are present into soil minerals. Parent material can form in place from the weathering of the underlying bedrock, or it can be transported from somewhere else by wind, water, ice, or gravity. Different parent materials lead to very different soil types.r

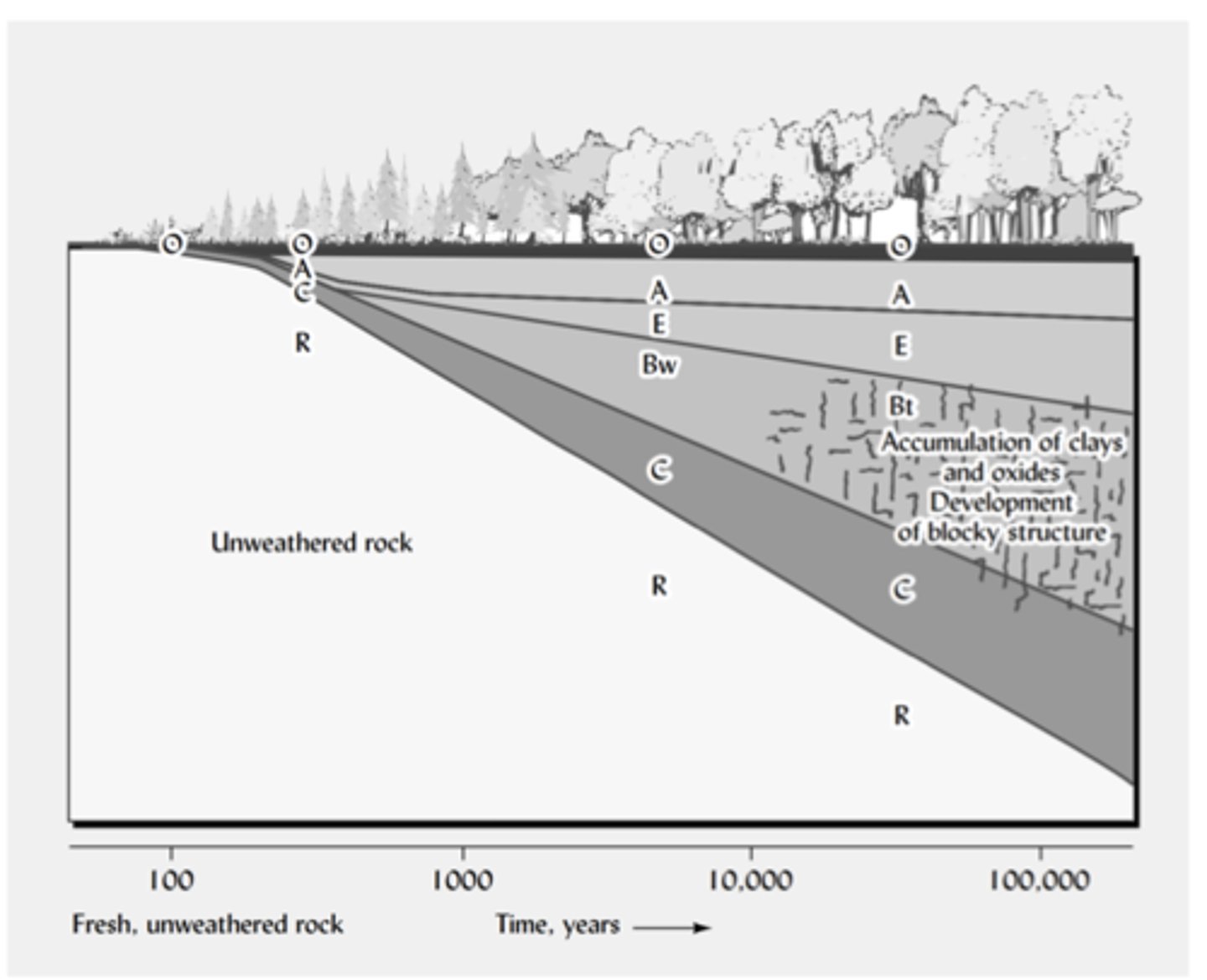

Time

Time refers to how long soil-forming processes have been operating. The longer a surface has been exposed, the more weathering, organic matter accumulation, and horizon development can occur. More time produces thicker, more developed soils with clearer layers. Time does not act alone—if the climate is warm and wet, soil develops faster; if it is cold or dry, development is slower—but overall, older soils are deeper and more mature than young soils.

Processes of soil formation vs soil forming factors

Soil forming factors describe what soils are likely to form where

Processes of soil formation describe how soils form in a place

Processes of soil formation 4 Steps

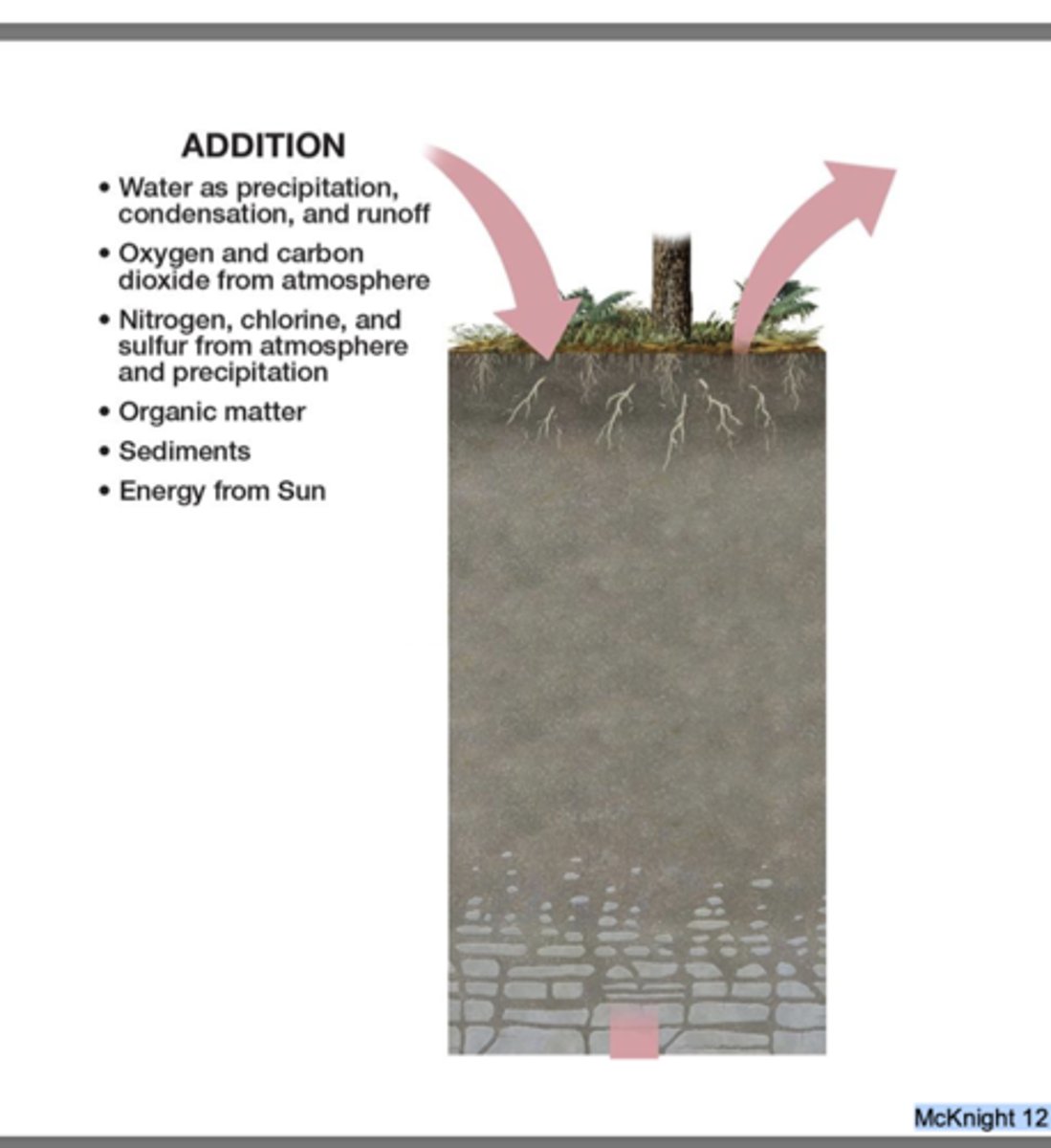

1. Additions

2. Losses (depletion)

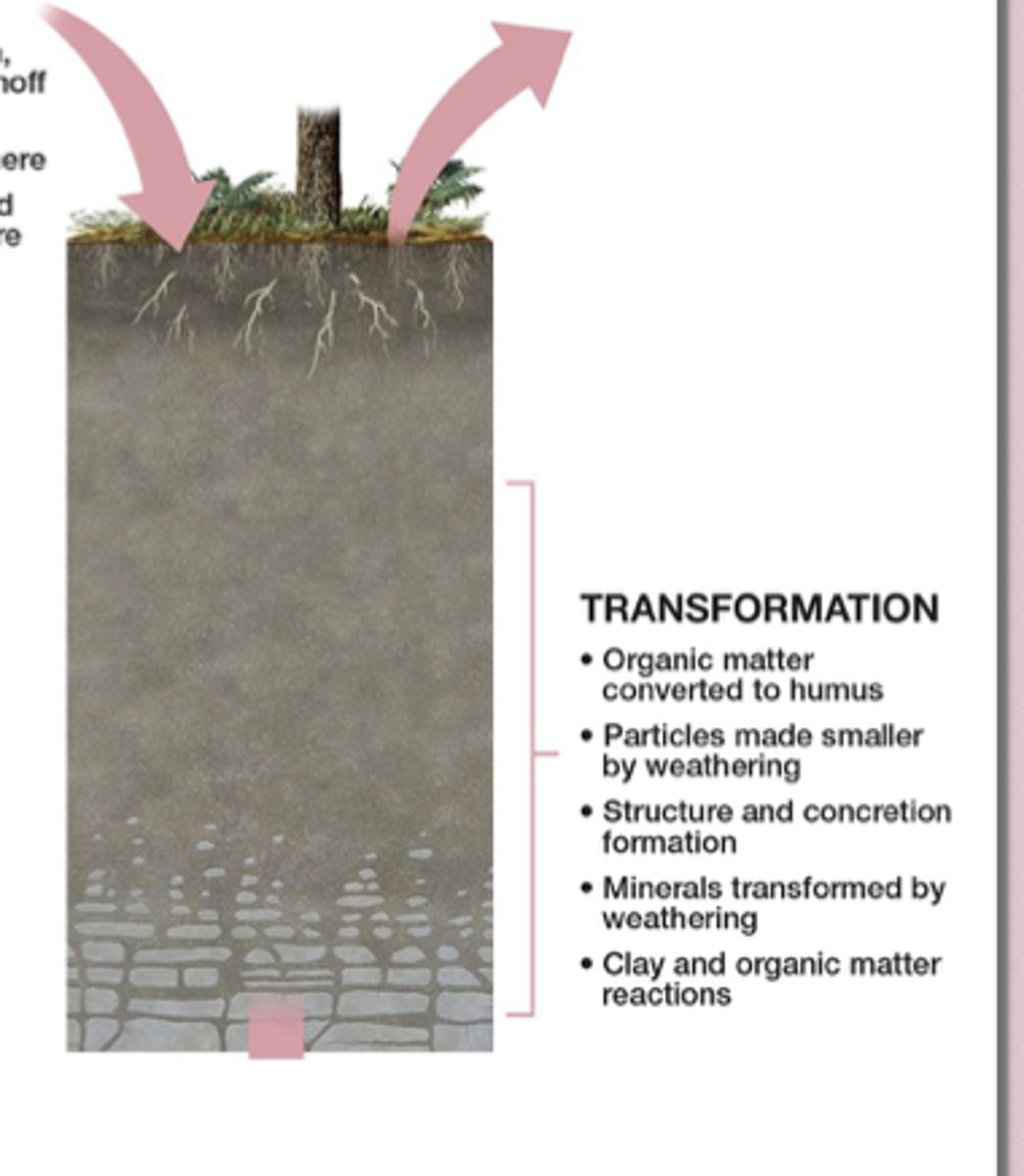

3. Transformation

4. Translocation

Addition

gains to the soil from organic or inorganic sources

Organic

leaf litter

dead organisms

roots dying and decomposition

Inorganic

windblown dust

sediment carried by water

anthropogenic pesticides

Transformation

Transformations are changes to the materials already in the soil—the minerals and organic matter are chemically or physically altered into new forms.

This includes oxidation of iron in well-drained soils, creating red/yellow colors, and reduction of iron or copper in saturated, oxygen-poor soils, creating gray/blue colors. These chemical changes modify the soil’s properties and contribute to soil horizon development.

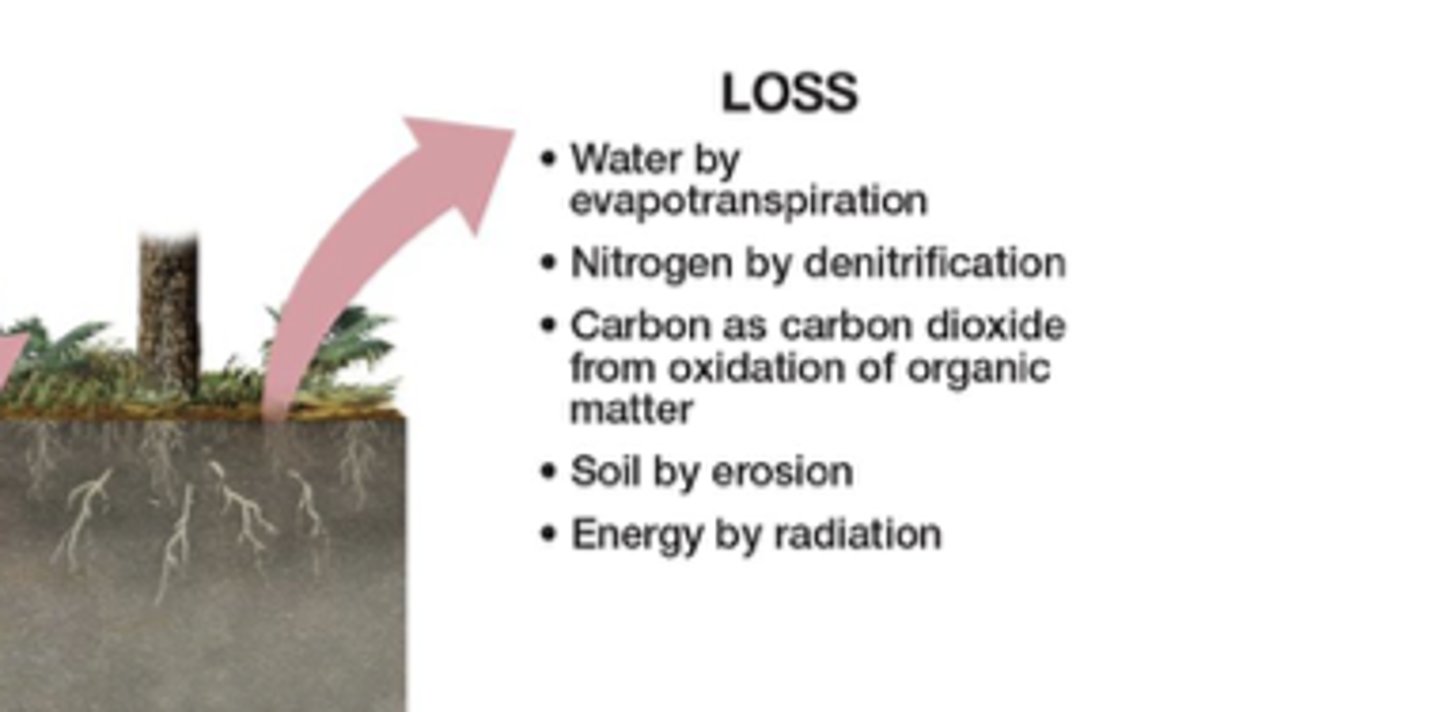

Losses (depletion)

Losses remove material from soil through nutrient leaching (like NO₃⁻ being washed out by water) and erosion (downslope removal of fine particles, leaving soil coarser and sandier).

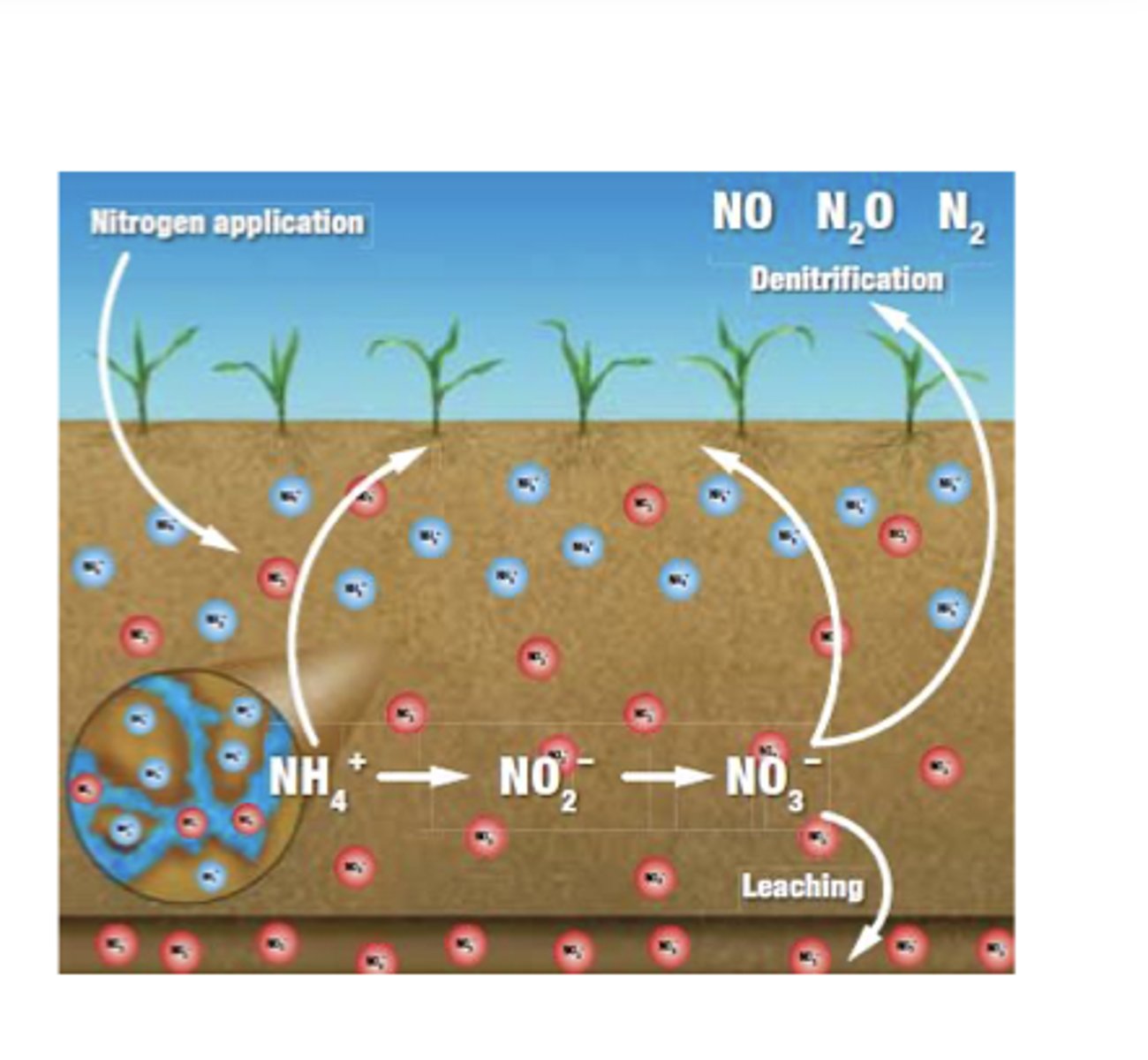

Leaching of soil Nutrients

Leaching is the process where water moving downward through soil dissolves and carries away nutrients.

Because nitrate (NO₃⁻) is negatively charged, it does not bind well to the negatively charged surfaces of soil particles, so it easily dissolves in water and is quickly washed out of the soil after rainfall.

In contrast, positively charged ions like ammonium (NH₄⁺) stick to soil particles and do not leach as easily.

Soils with coarse texture (sandy), high rainfall, or low organic matter promote stronger leaching because water moves through them faster and the soil has fewer charged particles to hold nutrients in place.

Leaching represents a loss from the soil system because nutrients are physically removed from the root zone and transported deeper into the soil or groundwater.

Translocation

Translocation is the movement of materials within the soil, either downward, upward, or sideways, as water or organisms physically carry particles and dissolved substances from one soil layer to another. Water is the main agent of translocation: rain can pull clay, nutrients, organic acids, and minerals downward through the soil profile, or move materials sideways along slopes. Burrowing organisms, including worms, insects, and small animals, also mix and move soil particles between horizons. As a result, translocation redistributes materials inside the soil and helps create distinct soil horizons.

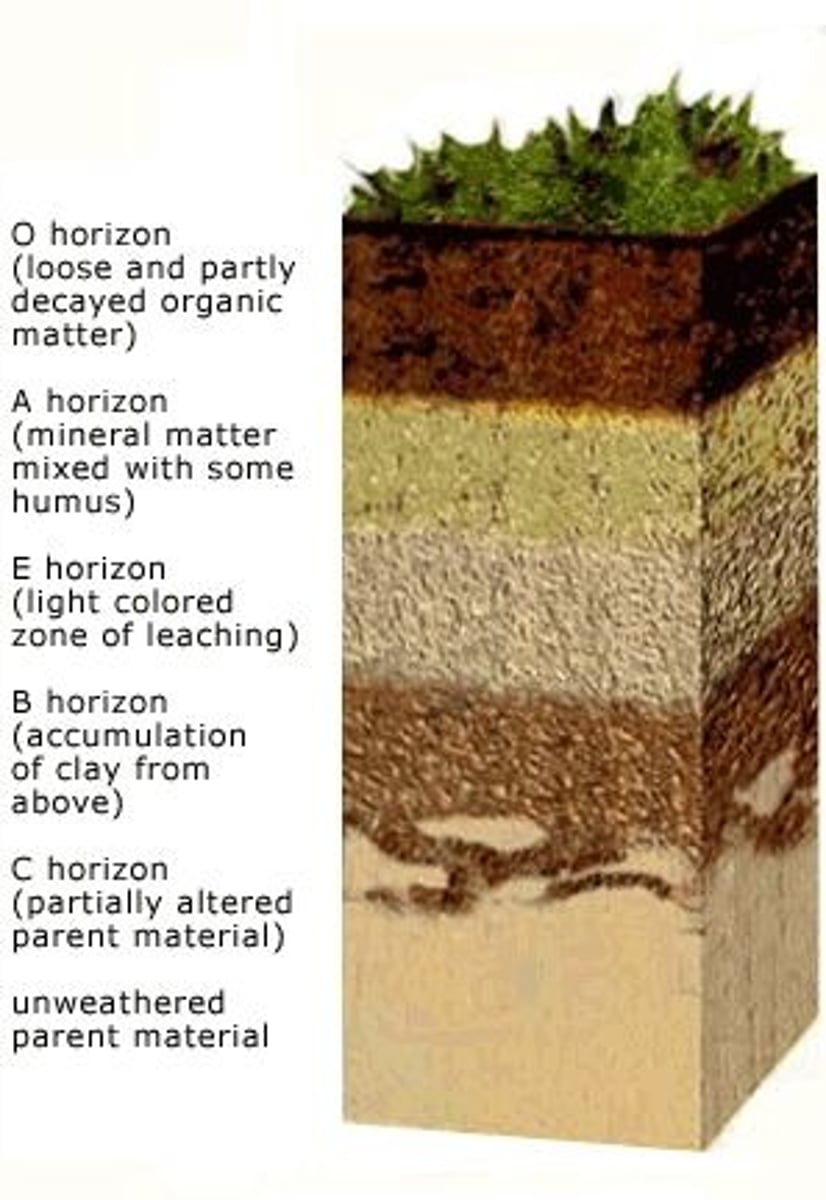

Eluviation vs. Illuviation

Eluviation is the process where water washes materials such as clay, organic matter, or minerals out of an upper soil layer (E horizon) and carries them downward.

Illuviation is the accumulation of those washed-down materials in a lower soil layer (B horizon) where they are deposited.

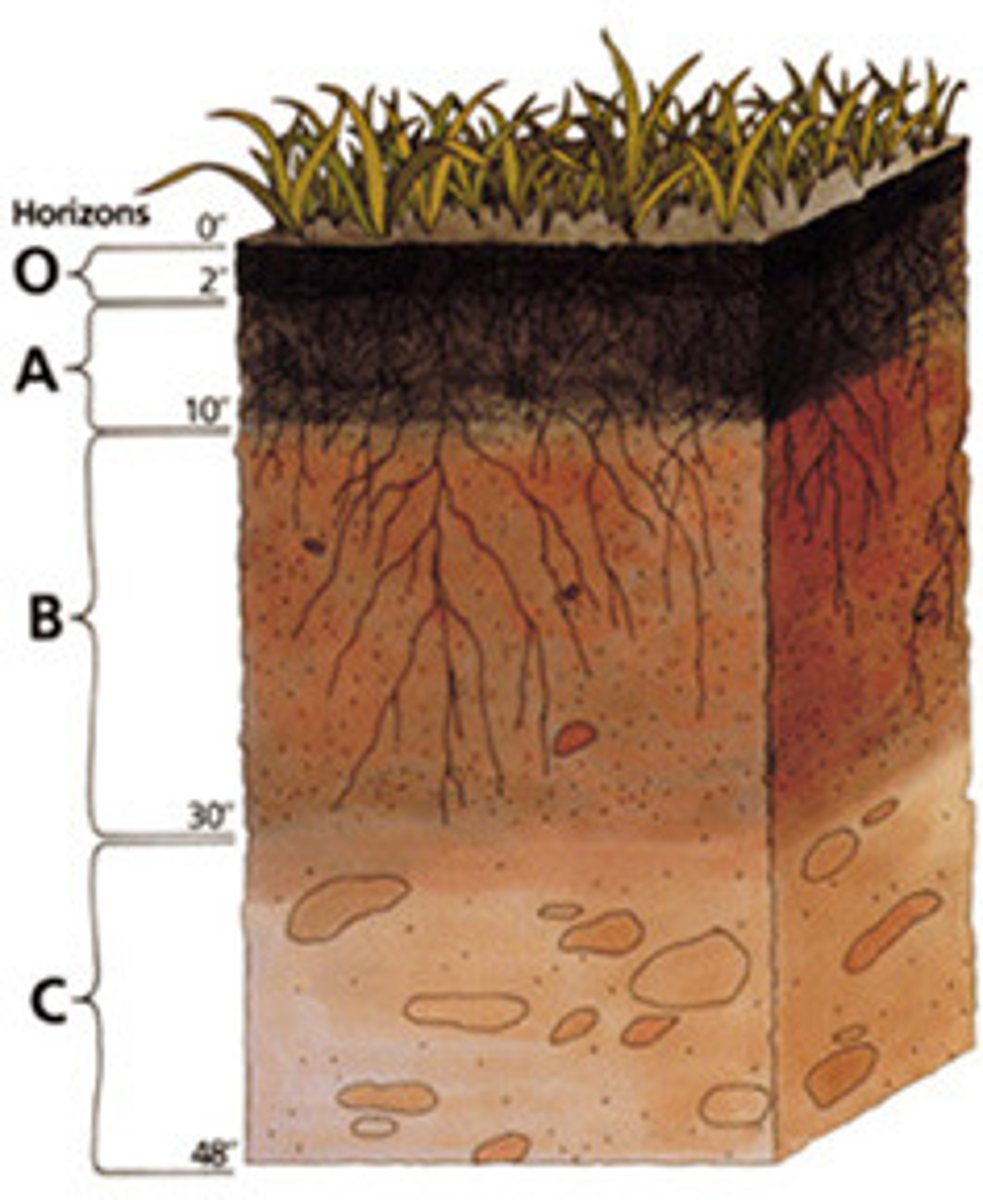

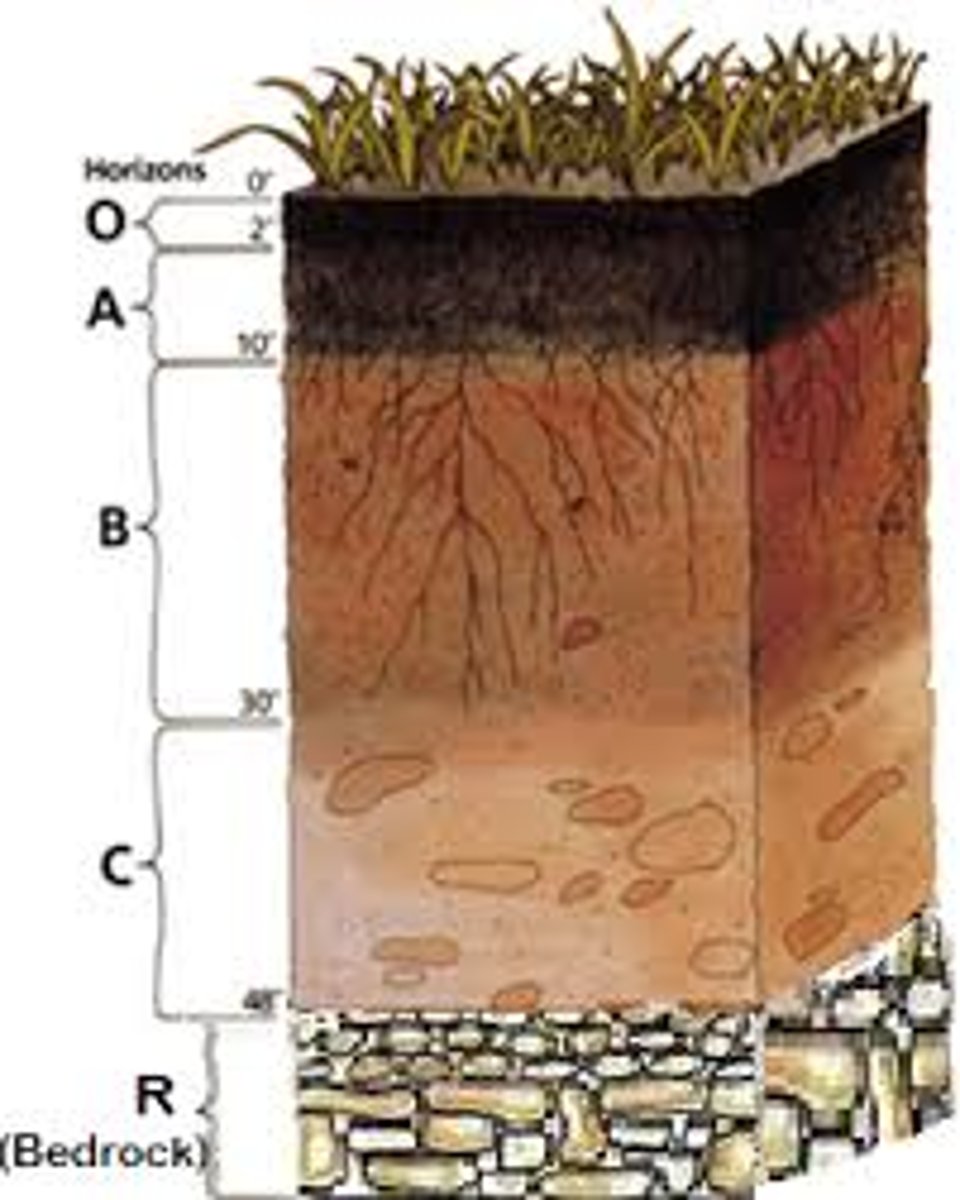

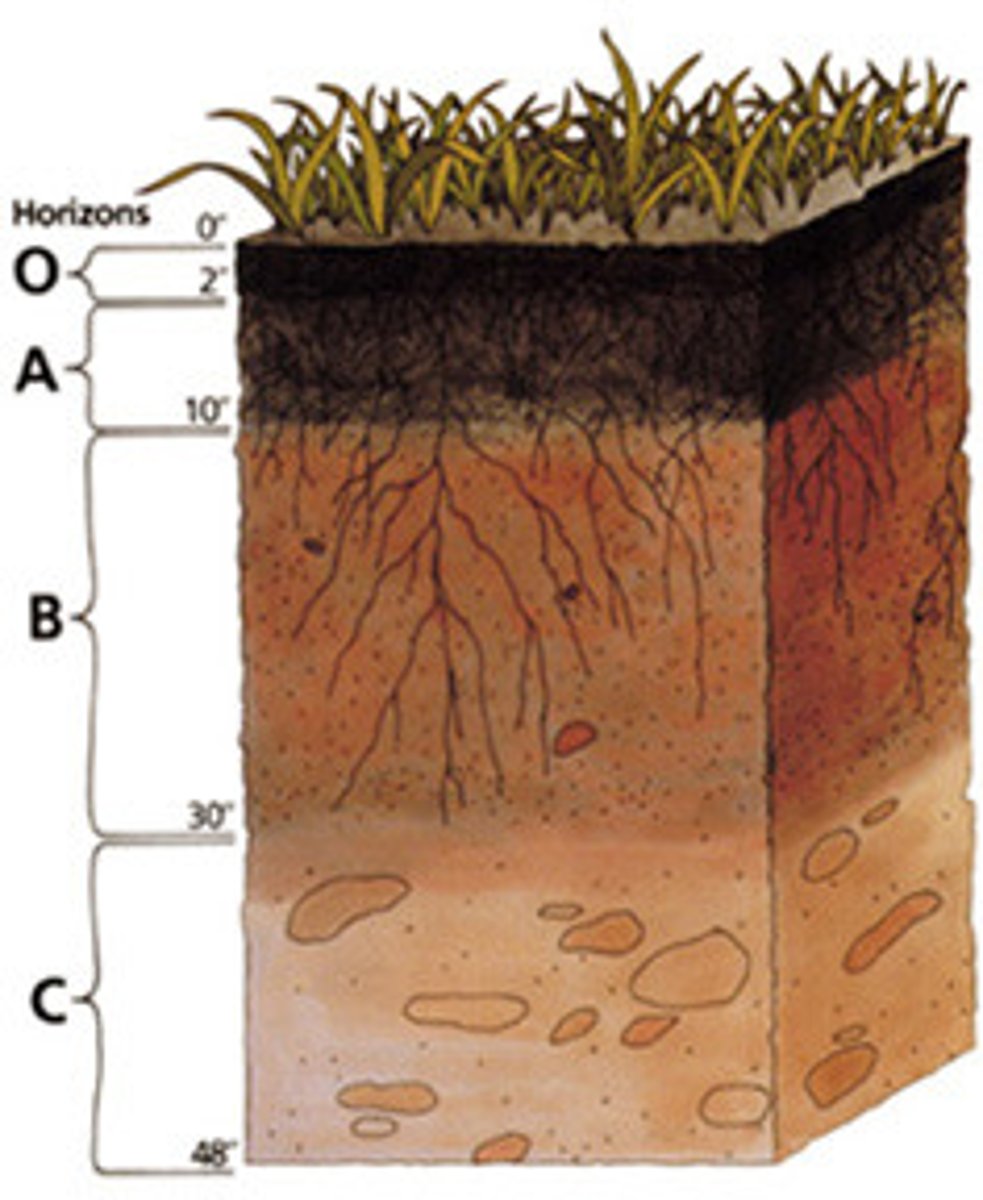

Soil Horizon Fundamentals

A soil horizon is a distinct horizontal layer within soil that share chemical and physical properties

There are six main horizons

1. O

2. A

3. E

4. B

5. C

6. R

O Horizon

The organic horizon at the surface of many soils, composed of organic detritus in various stages of decomposition

called the "forest floor"

Divided into decomposition level

1. Oi- organic, slightly decomposed

2. Oe- organic, moderately decomposed

3. Oa- organic, highly decomposed

A Horizon

first mineral soil layer beneath the organic litter (O horizon). It forms from weathered rock minerals mixed with decomposed organic matter (humus), giving it a darker color. Because it sits at the surface and receives rainwater, roots, and biological activity, it is the zone where minerals and fine particles are moved downward (translocation), leaving behind a coarser texture compared to deeper layers. This horizon is rich in nutrients, biologically active, and crucial for plant growth.

E Horizon

a soil layer where materials such as clay, iron, aluminum, and organic compounds are leached out and washed downward through a process called eluviation. Because these darker or heavier materials are removed, the E horizon is typically very light in color—often pale gray or ashy. It forms most commonly in forested landscapes, especially where there is enough rainfall and acidic leaf litter to enhance leaching. Essentially, the E horizon is the zone of maximum loss, where water percolates through and carries fine particles and nutrients into deeper horizons.

B horizon

the zone of illuviation, meaning it is where materials that were washed out of upper horizons (especially the E horizon) accumulate. As water moves downward through the soil, it carries fine clays, iron, aluminum, and dissolved minerals with it; these are then deposited and build up in the B horizon. Because this buildup only happens after soil has been developing for a long time, B horizons do not appear in very young soils. B horizons are often very thick in humid regions, where high precipitation increases downward water movement and therefore increases the amount of material transported into this layer.

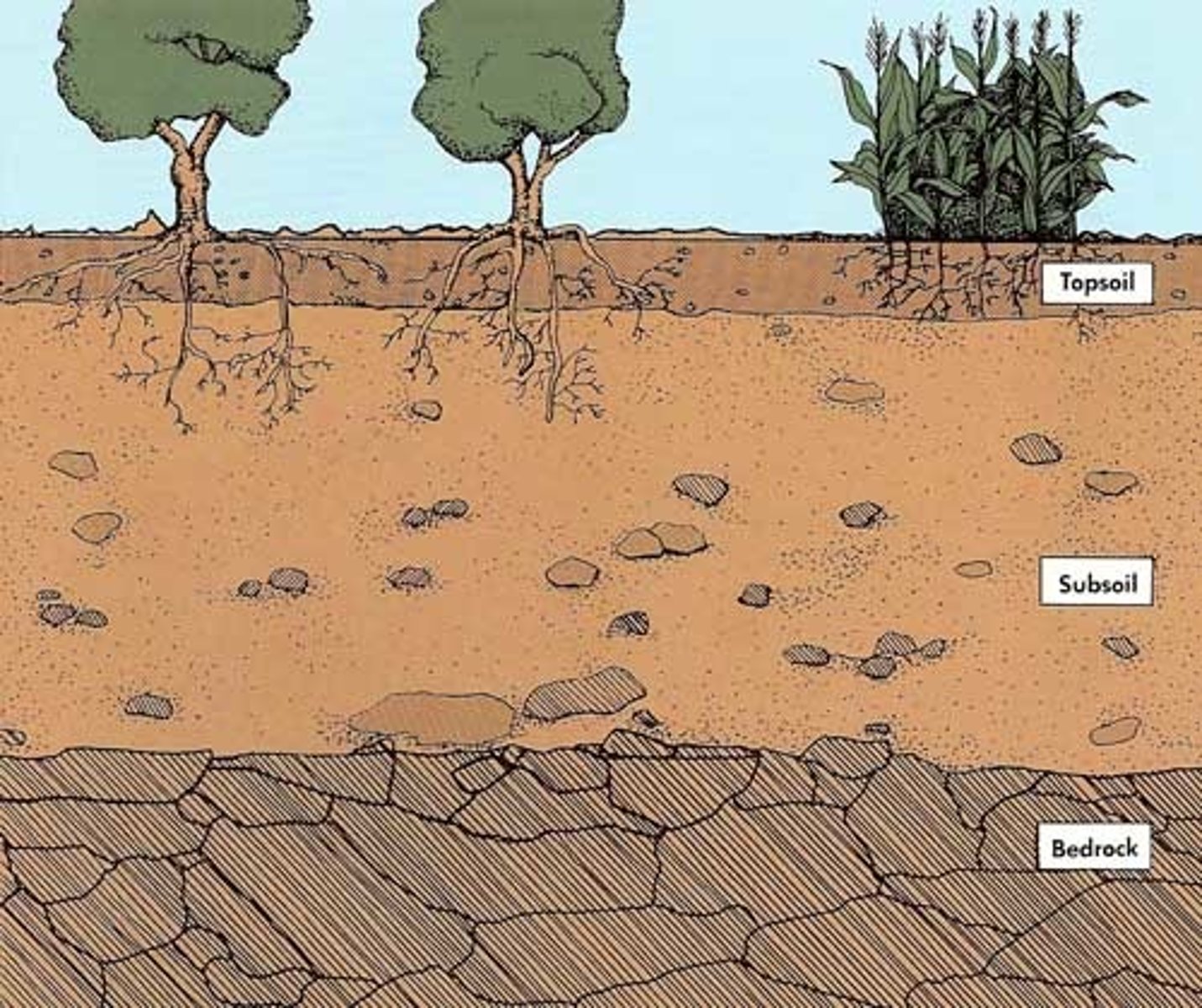

C horizon

layer of unconsolidated material beneath the developed soil horizons, consisting of loose rocks, gravel, and partially weathered sediment. It has undergone little to no soil formation, so it still contains recognizable features of the parent material from which the soil is forming. Because it is minimally altered by biological activity, chemical reactions, or translocation, the C horizon represents the transition zone between true soil and the underlying geological material.

R horizon

The R horizon is the deepest soil layer and is made of consolidated rock, meaning the rock is still hard, unbroken, and not yet weathered into loose material. Because it is solid bedrock, it cannot be dug with a shovel, and it has not undergone soil-forming processes like mixing, leaching, or biological activity. Sometimes this hard rock is the parent material that the upper soil layers will eventually weather from, but it doesn’t have to be—soil above it may have been transported from somewhere else. Essentially, the R horizon marks the transition from true soil to the underlying intact geological bedrock.

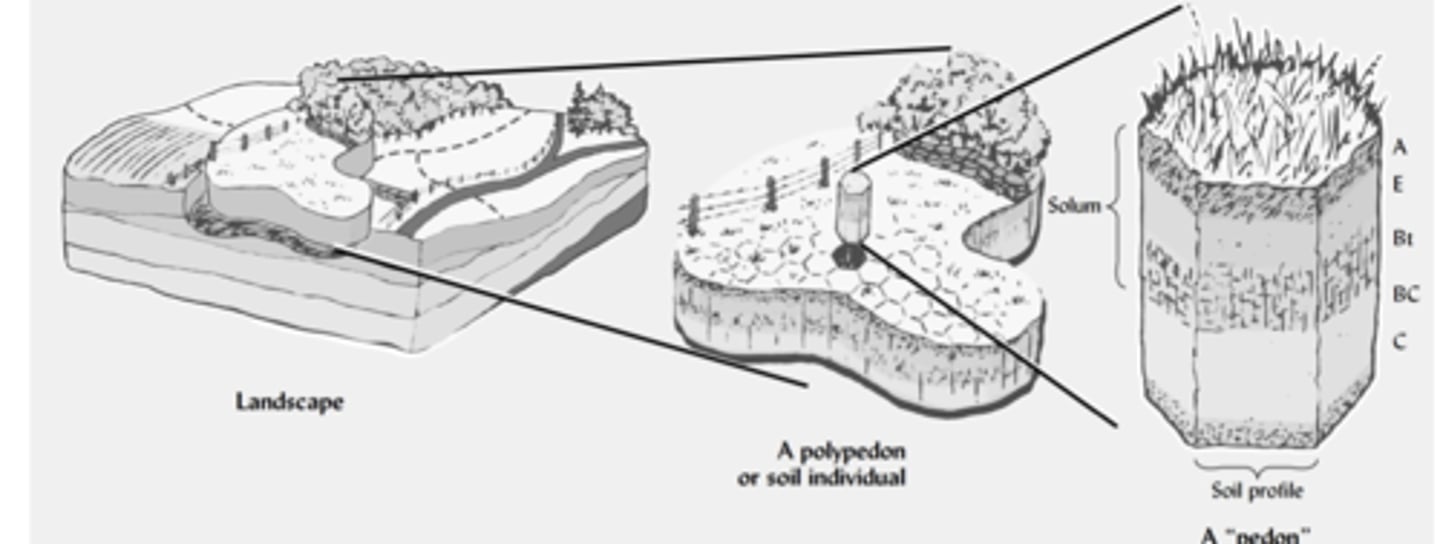

soil profile

the vertical cross-section of soil that shows all of its natural layers (called horizons) from the surface down to the unweathered rock

Pedon

A pedon is an imaginary three-dimensional unit of soil that represents the smallest volume in the landscape that still contains all the soil horizons and properties of that soil type.

It’s imaginary because soil scientists define it as a standard measurement unit, but in practice they dig or sample an area of about 1–10 m² to represent it.

Physical Characteristics of Soil

made up of soil texture and soil structure

soil texture

the proportion of sand, silt, and clay that affects the suitability of soil for most uses

you don't want to built on most clay rich soils and don't want to farm on most sandy soils

sand

the coarsest soil with particles 0.05 mm to 2.0 mm in diameter

silt

A mixture of rich soil and tiny rocks 0.002 to 0.05 mm in diameter

clay

the finest soil, made up of particles that are less than 0.002 mm in diameter.

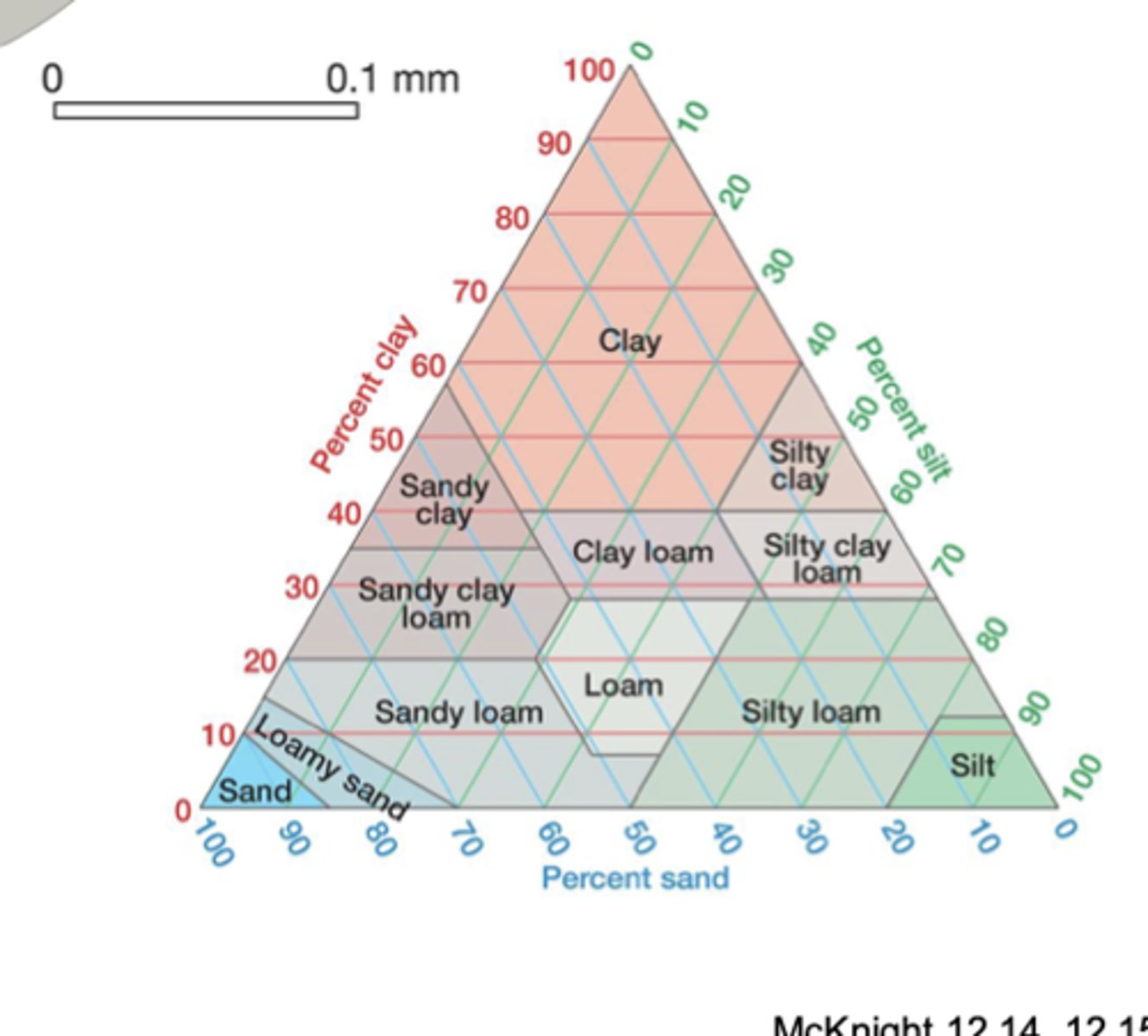

soil triangle

a graphic explanation of the proportions of sand, silt, and clay in soil

Clay = horizontal

Sand = diagonal ↗ left

Silt = diagonal ↘ left

soil structure

the shape of naturally occurring clumps of soil

porosity

The percentage of the total volume of a rock or sediment that consists of open spaces.

High porosity holds a lot of water

Low porosity holds little water

permeability

The ability of a rock or sediment to let fluids pass through its open spaces, or pores.

Clay soils have

high porosity and very low permeability

Sandy soils have

low porosity and very high permeability

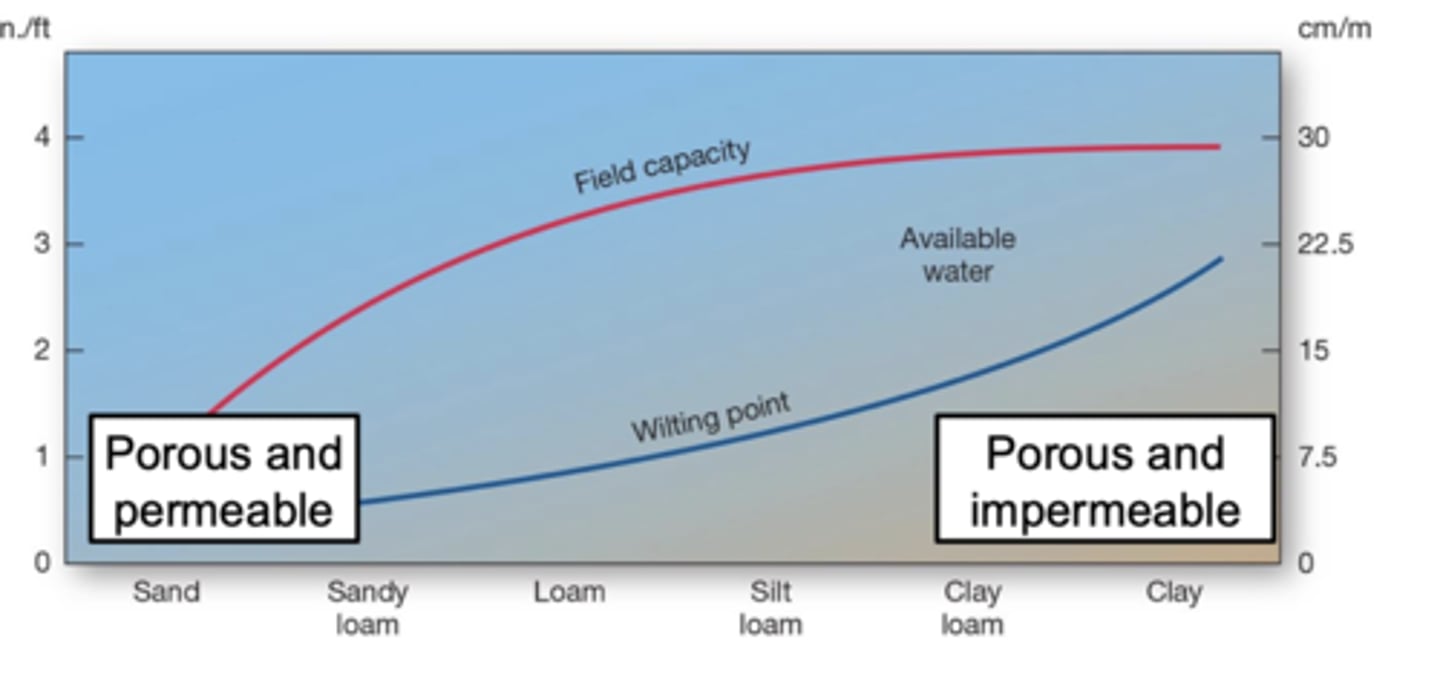

Wilting Point Graph

sand drains too fast to hold plant water, clay holds too much water too tightly for plants to use, and loam provides the BEST balance of water storage and drainage — giving plants the most available water.

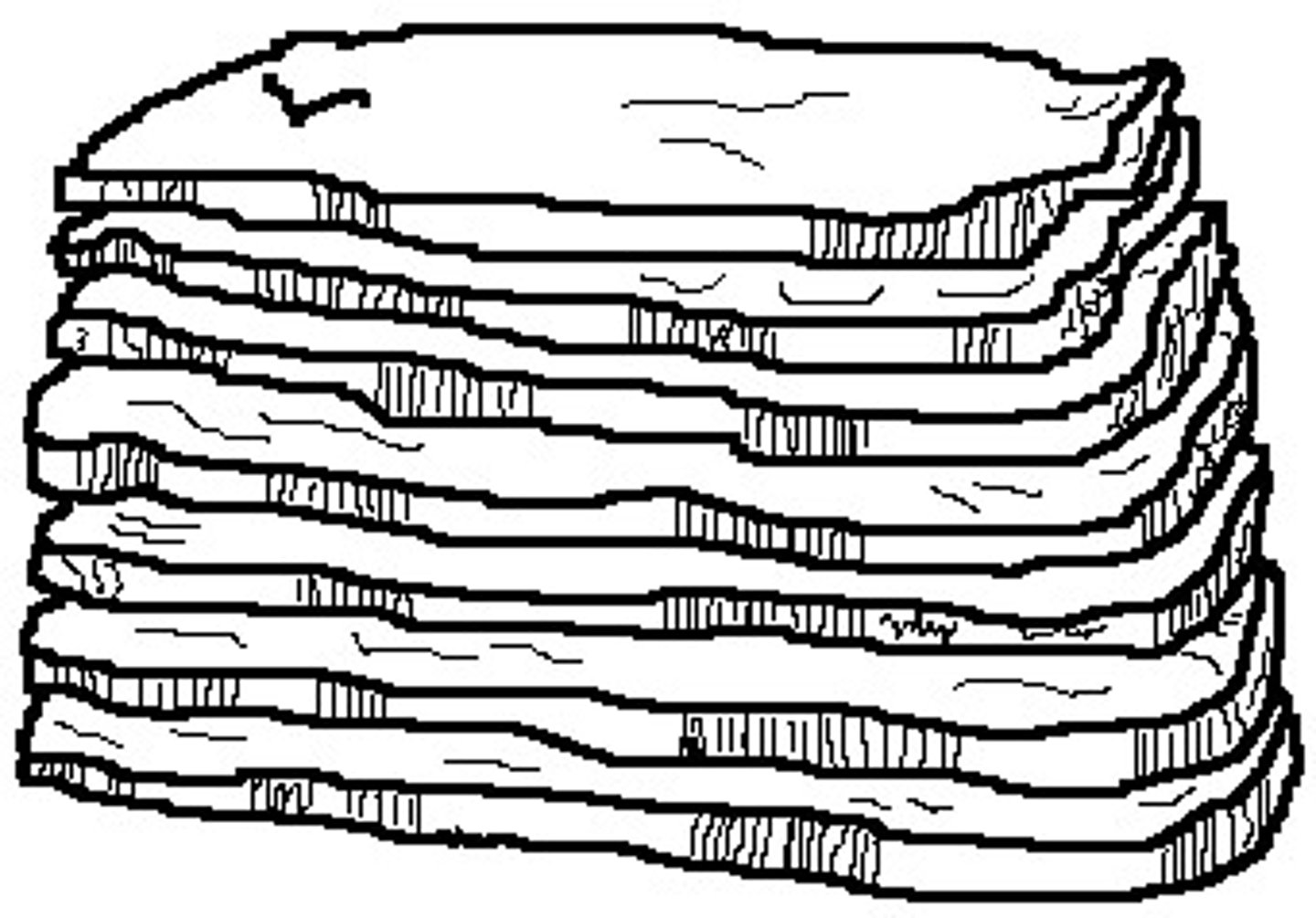

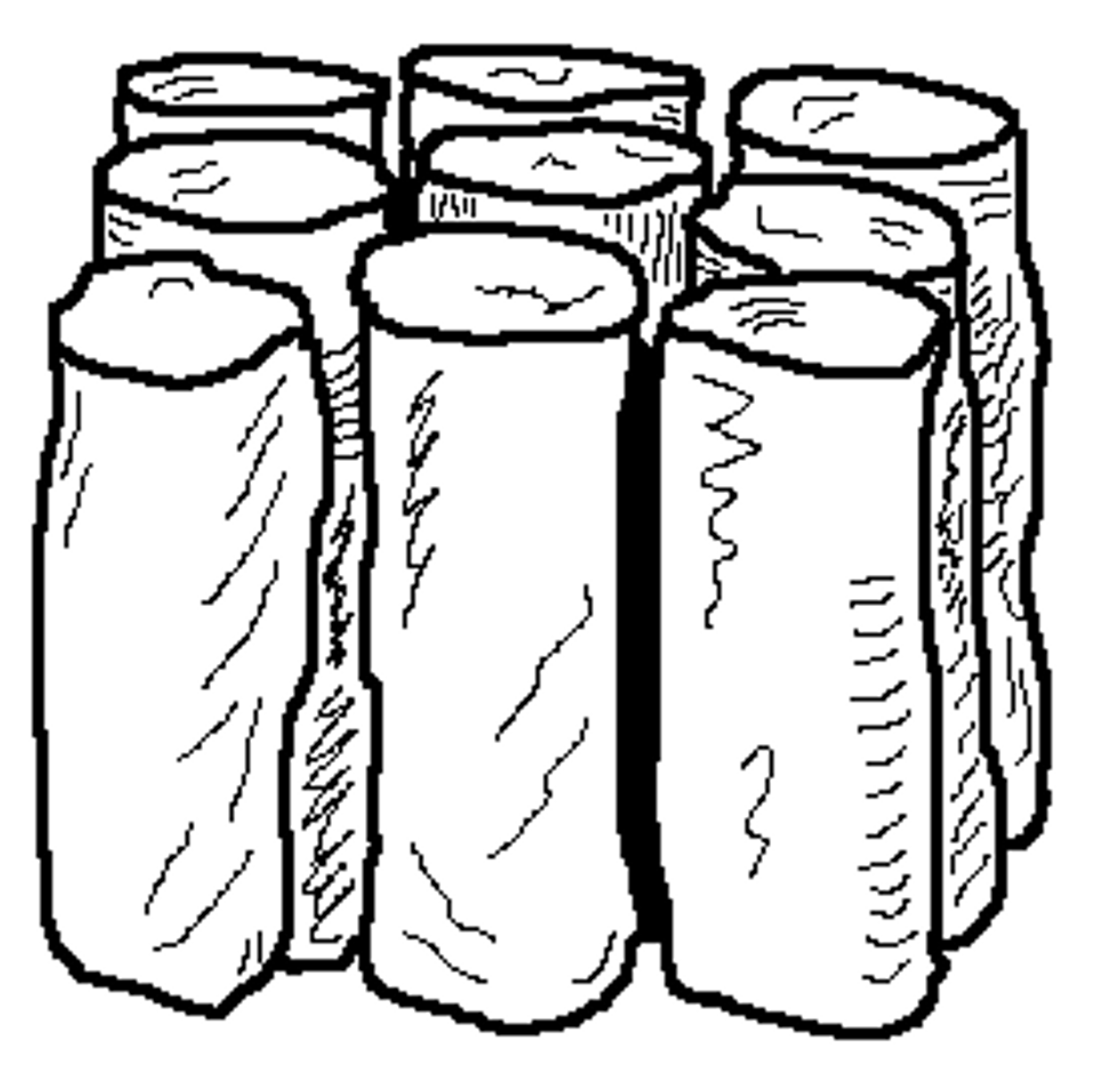

Soil Structure (the shape of naturally occurring clumps of soil) 4 Types

1. Platy

2. Prismatic

3. Blocky

4. Spheroidal

Platy

thin, flat, plate like aggregates stacked horizontally

Common in E horizons where materials are washed out, leaving dense, compacted, fine texture layers

Inherited from parent material or caused by compaction, freeze-thaw, or wetting and drying

Prismatic

Tall, vertical aggregate columns with flat tops

Common in the B Horizon where materials accumulated due to illuviation and where there is soils of arid and semi-arid conditions.

Caused by shrink-swell or illuviation.

Clay-rich soils swell when wet and shrink when dry.

This shrinking causes:

Vertical cracks

Separation of the soil into tall columns

Deep, straight fissures

When clay washes downward into the B horizon:

It fills pore spaces

Increases stickiness and density

Forms vertical coatings called clay skins

Encourages vertical cracking

This process solidifies and strengthens prisms.

Blocky

Cube like blocks formed by irregular aggregates that fit together

Common in B horizons in humid regions and sometimes occur in A horizons as organic matter clumps together

There are two types: angular (sharp edges) and sub angular (rounded edges)

Caused by shrink swell or biological activity

Spheroidal

Small, nearly round aggregates that look like cookie crumbs

Very common in A horizons because of the high organic matter and intense biological activity

There are two types: granular (porous) and crumb (very porous)

Caused by biological activity

Soil Color is determined by

the chemical and physical properties

measured using the Munsell color chart ($298)

Red soil

Red soils are colored by oxidized iron (Fe³⁺) and indicate well-drained, highly weathered soils that often contain clay and iron oxide coatings. The red color shows that the soil has had long-term exposure to oxygen.

Gray/blue soils

Gray or blue soils form under waterlogged, low-oxygen conditions, where iron becomes reduced (Fe²⁺). These colors signal poor drainage and are typical of wetlands or saturated horizons (gleying)

Dark Brown Soils

Dark brown or black soils get their color from high organic matter, which makes them fertile and biologically active. These colors typically form in productive A horizons, especially grassland soils.

Light gray/white soils

Light gray or white soils indicate the presence of calcium and magnesium carbonates, or strong leaching that removes organic matter and iron. These colors often appear in arid soils with salt/carbonate accumulation or in E horizons that have been heavily eluviated.

Yellow brown/orange soils

Yellow, brown, and orange soils get their color from iron compounds, especially hydrated iron oxides. These colors reflect moderate oxidation and well-drained conditions, but not as intense or prolonged as the conditions that create red soils.

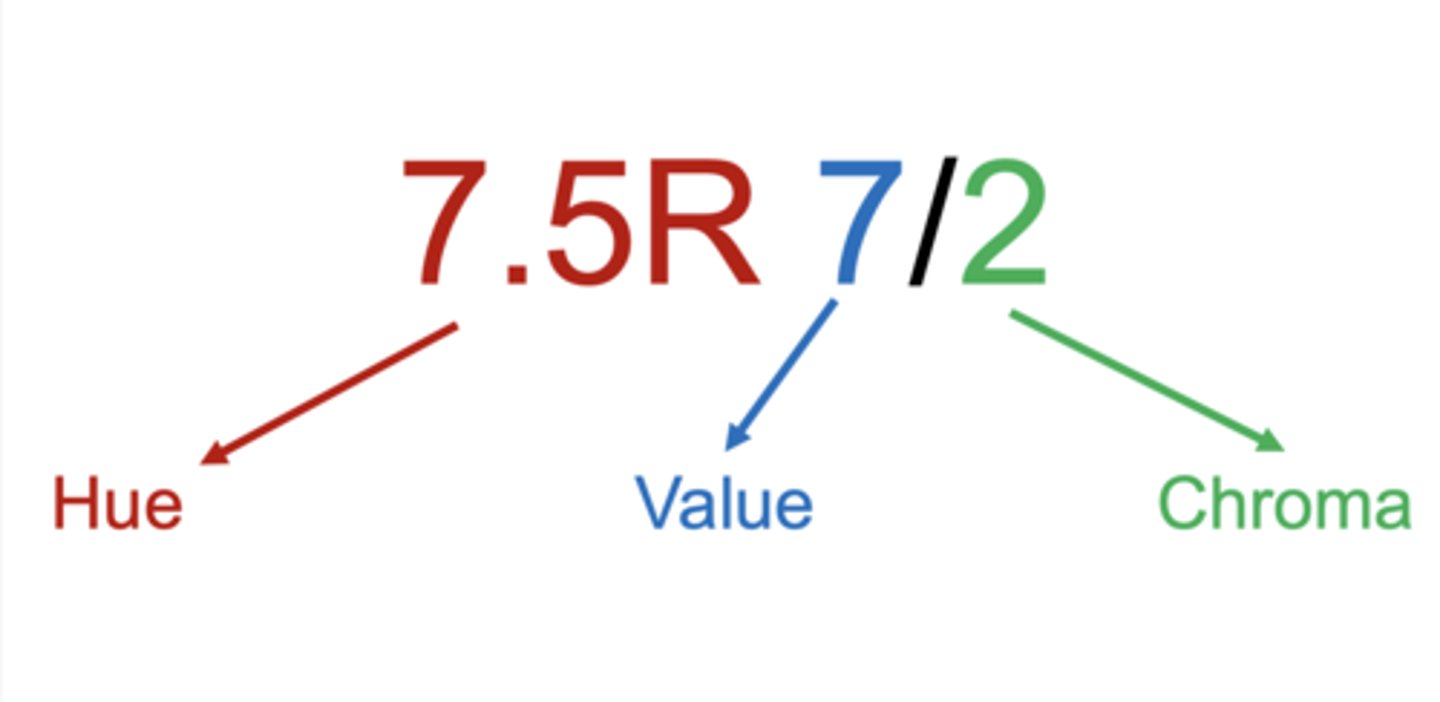

Munsell Soil Color Notation

7.5R 7/2 breaks down into hue, value, and chroma — the three components of color in the Munsell system.