3-5 Soil solid phase

1/52

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

53 Terms

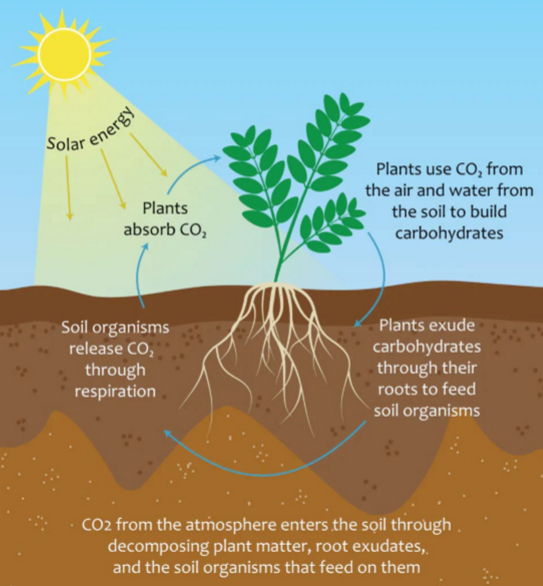

Organic matter in soil: C cycle

Soil one of the most important C reserve on earth

Nitrogen important for soil, organism in the soil can catch it in the atmosphere and break it for the soil → fertilizer are Nitrogen already broken for the soil

OM → Source of C and energy

Organic matter composition

Composition of the OM: C (50%), H, O, N, S, P and metal cations

Changes from soil to soil, from season to season…

Content of OM in the topsoil:

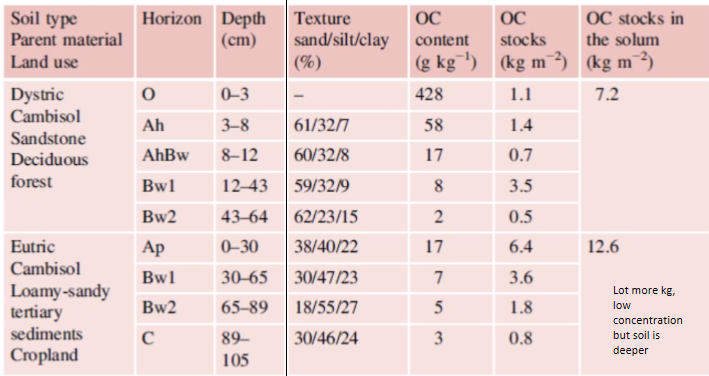

Concentration vs Stock of organic C

Concentration → Indica quanto carbonio c’è nel suolo in proporzione alla massa del suolo. → in % o g C / kg di suolo

Stock → Indica quanto carbonio totale è contenuto in un certo volume o area di suolo. → kg C / m²

Content*(density or area) → stock

Concentration is important but stock also

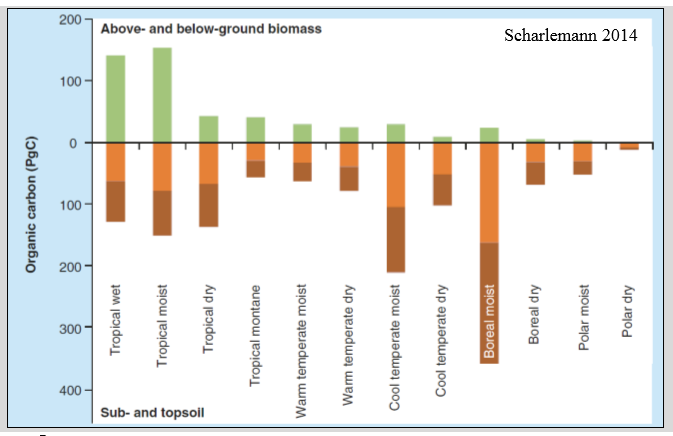

Global stock C distribution

More in the soil than in plants, more in colder places cause there are less organism

Soil OM: global fluxes and stocks

OM in soil definitions

Organic matter = humus in the broad sense: all dead plant and dead animal substances in and on the mineral soil and their organic transformation products

Edaphon (soil biota): living organisms and roots → not part of the soil organic matter

Mineralization: complete microbial degradation to inorganic substances

Humification: formation of humus = protection of OM from further decomposition

Decomposition: breakdown of organic matter → transformation of organic residues by heterotrophic organisms leads to differentiation of the organic matter:

Plant remains

Microbial remains

Mineral-bound organic substance

Charcoal

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC)

C/N Ratio

Indicator for the ease of decomposition of OM but also for biological activity

Mineralisation = release of CO2 while N is incorporated into microbial biomass → C/N becomes smaller → C/N ratio goes lower when you lose carbon, because Nitrogen doesn't get lost

Degradability of organic matter: the smaller the more degradable → spruce woods really degradable

Composition of OM: Plant remains

Parenchyma (basic tissue)

Found in living green tissues (leaves, needles, fine roots)

Cell walls mainly contain cellulose and hemicellulose

Rich in proteins

Low C/N ratio (< 50)

Easily degradable

Lignified tissue

Includes wood (xylem) and supporting tissue (sclerenchyma)

Cell walls contain cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin

High C/N ratio (> 100)

Structurally strong and resistant to decomposition

Cellulose

Main structural component of plant cell walls

Long chains of glucose forming strong microfibrils

Mostly crystalline, partly amorphous

Provides mechanical strength

Usually associated with hemicellulose and lignin

Hemicellulose

Cell wall polysaccharides made of different sugars

Shorter and more branched than cellulose

Amorphous and easily degradable

Links cellulose microfibrils together

Lignin

Very complex and highly cross-linked polymer

Common in vascular and woody plant tissues

Provides rigidity, protection, and resistance to microbes

Very resistant to degradation (not easily broken down)

Composition of OM: Plant wax and fats

Lipids

Mostly unbranched hydrocarbon chains

Chemically diverse group (fatty acids, phospholipids, glycolipids)

Key components of biological membranes

Important for energy storage and waterproofing

Generally more resistant to degradation than carbohydrates

Cutin

Structural polymer forming the plant cuticle (wax layer)

Found on the surface of leaves and stems

Built from hydroxy fatty acids

Provides protection against water loss and pathogens

Contributes to plant resistance and durability

Suberin

Cell wall component in outer tissues of woody plants

Especially abundant in bark and roots

Similar to cutin but made of longer-chain components

Acts as a strong barrier to water, gases, and microbes

Very resistant to biological degradation

Composition of OM: cellular constituent

Proteins

Long chains of amino acids (polypeptides)

Present in plant and microbial tissues

Readily degradable by many microorganisms

Important nutrient source (especially nitrogen)

Less stable than structural compounds like lignin

Tannins

Polyphenolic compounds

Bind to proteins and reduce their availability

Can slow down microbial decomposition

Common in leaves, bark, and woody tissues

Other Cellular Compounds

Pigments: e.g. chlorophyll

Starch: energy storage compound in plants

Nitrogen, sulphur and phosphorus in OM

Nitrogen → Almost exclusively binding to OM in soil (95%) → First in microbial biomass, then stabilized in OM → Mostly in peptides

Sulfur: → up to 90% S in organic form, 30 - 75% as organo sulphates, rest as amino acids

Phosphorus → > 50% bound in the form of orthophosphate

Mineralization and humification

Mineralization

Microbial breakdown of organic matter into inorganic nutrients

Produces carbon dioxide, water, and plant-available nutrients

Fast for easily degradable compounds (carbohydrates, proteins)

Leads to nutrient release into soil solution

Humification

Transformation of organic residues into stable humic substances

Favored by resistant compounds (lignin, fats, waxes, tannins)

Slower process than mineralization

Contributes to long-term carbon storage in soils

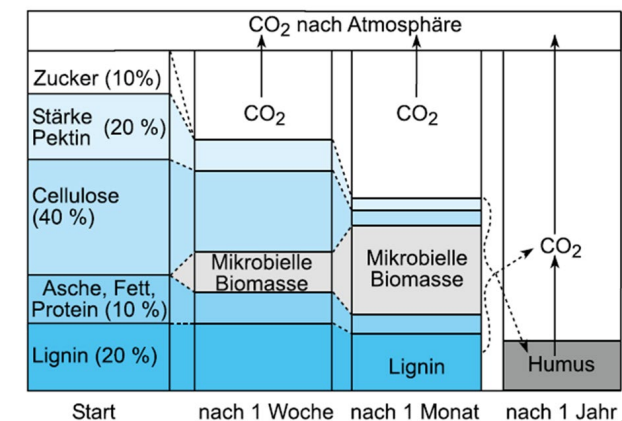

Decomposition of litter

Plant litter is decomposed by microorganisms and soil fauna

Early phase: biochemical breakdown of simple compounds

Initial phase: leaching and rapid microbial growth

Crushing phase: mechanical fragmentation by soil fauna

Final phase: enzymatic degradation, nutrient release, accumulation of resistant compounds

Key idea: Litter decomposition drives nutrient cycling and soil organic matter formation.

Biochemistry of degradation processes

Biochemistry of Degradation Processes

Easily degradable polymers are enzymatically hydrolyzed early

Proteins, starch, nucleic acids, simple lipids

Complex and resistant compounds require prior physical breakdown

Cellulose: degraded by specialized enzyme systems

Lignin: broken down via oxidative reactions

End result: small molecules that serve as microbial food

Speed of litter degradation

Litter factors (degradability):

N content of the substance (C/N ratio)

Lignin content (lignin/N ratio)

Tannin content (polyphenol/N ratio)

External factors, environmental factors:

Heat/temperature

Availability of H2O and O2

pH

Inhibitors (bactericides, fungicides)

Stabilisation of OM

Stabilisation (Humification)

Processes that slow down organic matter decomposition

Leads to accumulation of humus in soil

Stabilized organic matter is older and more persistent

Stabilisation by Recalcitrance

Delayed degradation due to molecular structure

Primary recalcitrance: plant-derived compounds with resistant structures (litter, roots)

Secondary recalcitrance: microbial and animal products forming resistant macromolecules

Includes pyrogenic (black) carbon, highly resistant

Key Idea → Chemical complexity increases resistance to microbial breakdown

Old and new concept of stabilisation

Old Concept

Soil organic matter forms large, stable humic macromolecules

Stabilisation driven mainly by chemical condensation reactions

Humic substances (humic acids, fulvic acids, humin) seen as real soil entities

Molecular complexity = long-term stability

New Concept

Soil organic matter is mostly made of small, simple biomolecules

Stability depends on environmental protection, not molecular size

Key mechanisms: mineral association, physical protection, limited microbial access

Carbon persistence is dynamic and can change with conditions

Key Idea → Soil carbon is stabilized by its environment, not by intrinsic “humic” polymers

Stabilization through sorption and aggregation

Stabilisation through Sorption

Organic matter binds to mineral surfaces (clays, metal oxides)

Sorption reduces accessibility for microbes and enzymes

Strong organo-mineral associations increase persistence

Particularly important for small organic molecules

Stabilisation through Aggregation (Physical Disconnection)

Organic matter is physically protected inside soil aggregates

Limited access of microorganisms, oxygen, and enzymes

Larger aggregates store carbon short- to medium-term

Mineral-associated organic matter enables long-term storage

Key Idea → Soil carbon stability is controlled by physical protection and mineral interactions, not by molecular complexity alone

Importance of organic matter for soil

Major nutrient source for plants (especially nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur)

Improves nutrient retention and gradual release

Enhances soil aggregation and structural stability

Reduces erosion through clay–organic matter complexes

Increases water-holding capacity

Influences soil temperature via light absorption

Supports decomposition of organic pollutants

Key reservoir for carbon storage (e.g. peatlands, permafrost, biochar)

Key Idea: Soil organic matter is essential for soil fertility, structure, and climate regulation.

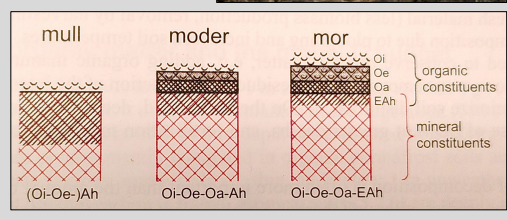

Humus forms

Mull

Most favorable humus form

Nutrient-rich soils

Neutral to slightly acidic

High microbial and soil fauna activity

Fast litter decomposition

No distinct organic (Oa) layer

Typical of deciduous forests and species-rich grasslands

Moder

Intermediate between Mull and Mor

Neutral to slightly acidic

Moist conditions

Moderate biological activity

Oi, Oe, and Oa horizons present with gradual boundaries

Common in coniferous, mixed, and deciduous forests

Mor

Least favorable humus form

Nutrient-poor soils

Acidic, often very wet or very dry

Low microbial and animal activity

Fungi-dominated decomposition

Thick litter layer, slow decomposition

Sharp boundaries between Oi, Oe, and Oa

Typical of coniferous forests and harsh environments

Key Idea:

Humus forms reflect decomposition intensity, biological activity, and nutrient availability.

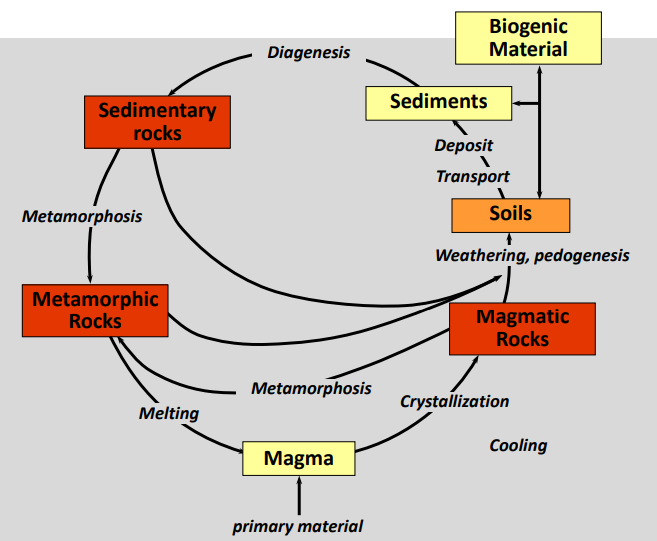

Parent material → Rocks

Soils are made of organic matter and rocks from the bedrock, also called parent material.

The parent rock of a soil largely determines the soil development and the mineral content.

Rocks are classified according to their history of origin: Magmatic, metamorphic and sedimentary

Magmatic rock soil properties:

Basalt / Gabbro → base-rich, nutrient-rich

Andesite / Diorite → intermediate

Rhyolite / Granite → silica-rich, nutrient-poor

Extrusive: fine-grained, chemical weathering dominant

Intrusive: coarse-grained, physical weathering dominant

Key idea: More silica → fewer bases → lower soil fertility.

Sedimentary rocks:

Clastic: formed from mechanical weathering (e.g. sandstone, shale)

Chemical: formed by precipitation from solution (e.g. rock salt, some limestones)

Organic: formed from accumulated biological material (e.g. coal, some limestones)

Key idea:

Sedimentary rocks form from weathering, precipitation, or biological accumulation.

Lithosphere cycle

Most common minerals in earth crust and soil

Most commons elements in earths crust → O and Si → SiO2 most common mineral

This is also true for Soils

Primary minerals → comes from the rock → broken down rock goes into the soil

Secondary minerals → chemical composition changes

Minerals: silicates

Origin

Main source of secondary (pedogenic) minerals

Formation depends on temperature, pressure, cooling rate, and chemistry

Crystallize in sequence from high to low temperature

Early: olivine, pyroxene

Late: feldspars, quartz

Silicate Structures

Isolated tetrahedra → olivine

Single chains → pyroxenes

Double chains → amphiboles

Sheets (layers) → micas, clay minerals

Framework → feldspars, quartz

Properties

Structures linked by oxygen bridges

Negative charge attracts metal cations

Isomorphic substitution creates chemical diversity

Structure controls stability and weatherability

Key Idea → More complex silicate structures are more stable and weather more slowly

Micas (sheet)

Types

Muscovite: light-colored mica

Biotite: dark-colored mica

Structure

Sheet (layer) silicates with a 2:1 structure

Layers held together by potassium ions

Importance for Soils

Important source of potassium

Easily weathered minerals

Biotite weathers faster than muscovite

Occurrence

Magmatic rocks: mainly biotite

Sedimentary and metamorphic rocks: mainly muscovite

Key Idea → Micas are nutrient-bearing, easily weatherable minerals important for soil fertility

Tectosilicate (3D) → Quartz and Feldspar

Quartz

Pure framework silicate

Very resistant to weathering

Common as sand and silt in soils and sediments

Does not supply nutrients

Hard, irregular fracture surfaces

Feldspars

Framework silicates with aluminum substitution

Charge balanced by potassium, sodium, or calcium

Most abundant minerals in magmatic rocks

Easily weathered compared to quartz

Smooth cleavage surfaces

Relevance for soil

Feldspars release nutrients during weathering

Weathering forms secondary (clay) minerals

Quartz accumulates due to high resistance

Key Idea → Quartz persists; feldspars transform and feed soils

Weathering

Weathering alters rocks and primary minerals

Occurs at the interface with atmosphere, biosphere, and hydrosphere

Transforms primary minerals into secondary minerals

Produces clay minerals, oxides, and hydroxides

Key process linking lithosphere to soil formation

Key idea:

Weathering is the bridge between rocks and soils.

Physicall weathering

Mechanical breakdown of rocks without chemical change

Reduces grain size and increases surface area

Main Processes

Pressure release: cracking after erosion of overlying rock

Gravity: impact and crushing

Temperature changes: differential expansion of minerals

Frost weathering: ice expansion widens cracks

Salt weathering: crystal growth in pores and fractures

Biological pressure: root growth

Transport & Abrasion

Water: rolling, abrasion, scouring

Wind: saltation and suspension of fine particles

Ice: transport and abrasion at glacier base

Key Idea:

Physical weathering fragments rocks and prepares material for chemical weathering and soil formation.

Chemical weathering

Chemical transformation or dissolution of minerals

Driven by water, acids, and biological activity

Continuous process because products are removed by water

Main Processes

Hydration

Water molecules enter mineral structures

Weakens crystal bonds and promotes dissolution

Especially important for highly soluble minerals (e.g. salts)

Hydrolysis / Protolysis

Reaction of minerals with acidic water

Carbonic acid from CO₂-rich water plays a key role

Very important for carbonate dissolution and silicate alteration

Complexation

Organic acids released during decomposition bind metal ions

Increases mobility of metals such as iron and aluminum

Enhances mineral dissolution and element transport

Oxidation

Reaction with O₂

Fe²⁺ → Fe³⁺, S²⁻ → SO₄²⁻

Produces H⁺, lowers pH

Forms Fe oxides/hydroxides (goethite, hematite)

Protolyis (Hydrolysis) of Silicates

Reaction of silicates with H⁺ (water / carbonic acid)

Breaks Si–O–Al bonds

Releases K⁺, Na⁺, Ca²⁺

Forms clay minerals (e.g. kaolinite) + silica

Weathering of Silicates – Overview

Early stage: loss of interlayer cations (e.g. K⁺), structure partly preserved

Advanced stage: complete lattice breakdown → new secondary minerals

Products: clays, oxides, hydroxides

Weathering Products

Weathering residues (solid remains)

Weathering solutions (dissolved ions transported away)

Key Idea → Chemical weathering transforms primary minerals and releases elements, driving soil formation and nutrient cycling.

Weathering stability of minerals

Water solubility → Easily soluble salts < gypsum < calcite < dolomite

Structure of the silicates → Island < chains < leaf < framework (feldspars < quartz)

Fe(II) content (oxidizability) → Biotite < Muscovite

In general → Olivine < Pyroxene < Amphibole < Biotite < Plagioclase < Muscovite ≈ Orthoclase < Quartz

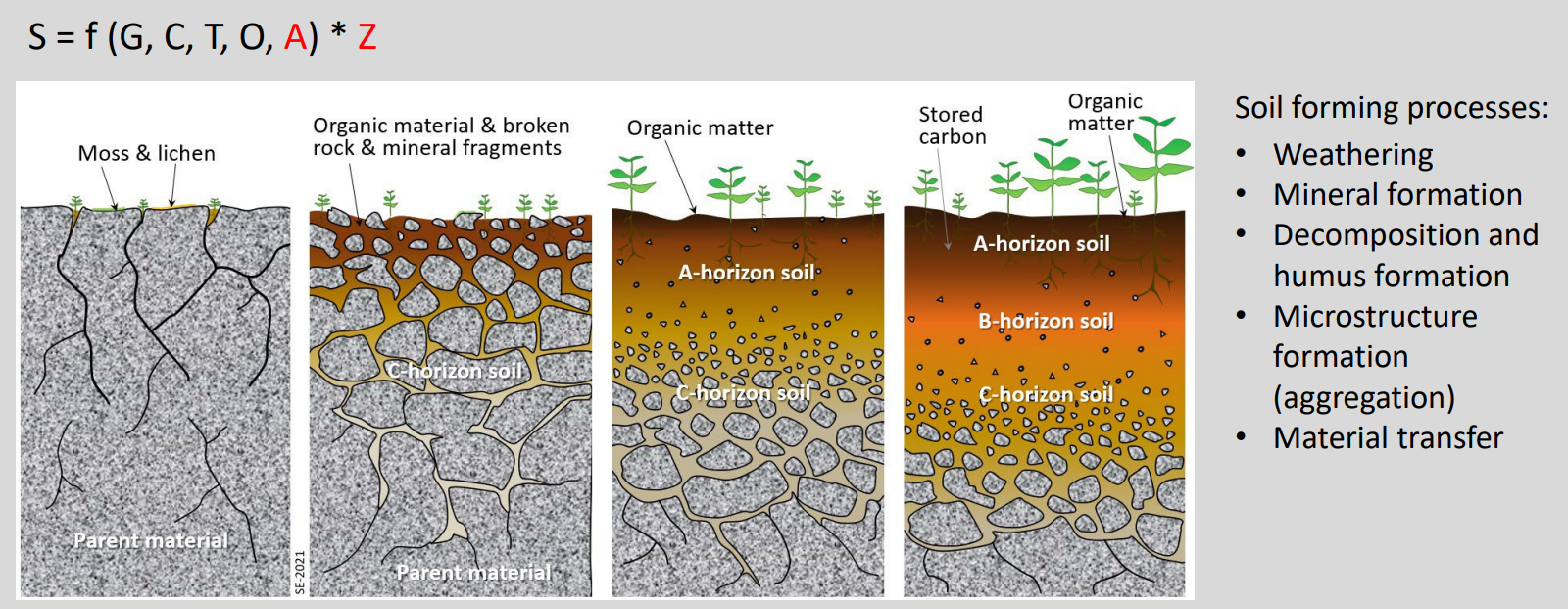

Pedogenesis image

Secondary minerals

Formed after partial or complete dissolution of primary minerals in the parent material

Main products:

Clay minerals (from layer silicates, e.g. micas)

Fe, Mn and Al oxides and hydroxides

Secondary carbonates and salts

These secondary minerals form in soils during pedogenesis.

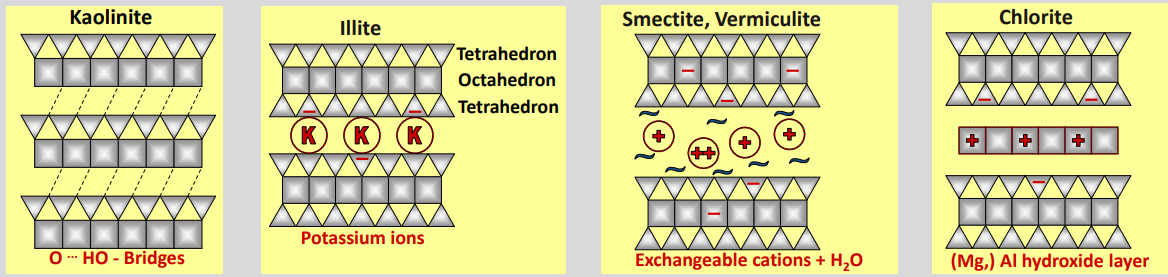

Clay Mineral

Origin

Formed from silicate weathering

Structure similar to mica (tetrahedral + octahedral layers)

Doesn’t change structure → Still tetrahedra/octahedra but with different minerals and charge

Particle size < 2 µm (clay fraction)

Identification

Formula unit: smallest repeating crystal unit

Basal spacing: distance between two consecutive layer units

Structural Types (classification)

Based on Si tetrahedra / Al octahedra stacking:

1:1 (e.g. kaolinite)

2:1 (e.g. smectite, illite)

2:1:1 (e.g. chlorite)

Special forms: tubes, spheres

Different interlayer compositions (K⁺, water, cations, OH layers)

Isomorphic Substitution

Tetrahedral: Si⁴⁺ → Al³⁺

Octahedral: Al³⁺ → Mg²⁺ or Fe²⁺

Creates permanent negative layer charge

Charge Compensation

Exchangeable cations in interlayers

Positively charged Al-hydroxide layers

Two layer clay mineral → Kaolinite

Structure: 1 tetrahedral + 1 octahedral layer (1:1)

→ layers linked by H-bonds, no interlayerBasal spacing: ~0.72 nm

Formula: Al₂(OH)₄Si₂O₅

Origin

Forms in Si-poor, strongly weathered (tropical) environments

End product of silicate weathering

Properties

White, non-expanding, no swelling/shrinking

Used for ceramics (porcelain)

Soil relevance

No nutrients in structure

Very low CEC (little isomorphic substitution)

Typical of low-fertility soils

Everything that could leach or so has happened, really ancient, not fertile, really deep

Three layer clay minerals (Illite, Smectite, Vermiculite)

Illite (2:1)

Derived from mica

Basal spacing ~1 nm

K⁺ fixed in interlayer → almost no swelling → K keeps layers together, not exchangeable

Important K source for soils

Smectite (2:1)

Often from basic igneous rocks

Expandable (1–2 nm)

Strong swelling/shrinking

Interlayer: hydrated, exchangeable cations

High CEC, high water retention

Hydrated cations in the middle

Available for plants, really fertile

Vermiculite (2:1)

Forms from biotite/muscovite

Expandable up to ~2 nm

Strong water retention

Interlayer cations partly fixed, partly exchangeable

Four layer clay mineral (Chlorite)

Chlorite (2:1:1 clay mineral)

Primary and secondary clay mineral

Structure: 2:1 layers + hydroxide interlayer (Mg-, Al-, or Fe-hydroxides)

Not expandable

Very low to no cation exchange capacity (CEC)

Layered clay minerals

Kaolinite (1:1)

No true interlayer; layers held by H-bonds (O–H···O) → non-expandable, very low CEC → no shrink or swellIllite (2:1)

K⁺ fixed in the interlayer → strong layer bonding, no swelling, moderate CEC → hold by KSmectite / Vermiculite (2:1)

Hydrated, exchangeable cations + H₂O in the interlayer → expandable, high CEC → lot’s of exchange, swelling and shrinkingChlorite (2:1:1)

Mg/Al hydroxide interlayer → rigid structure, non-expandable, very low CEC.

Further clay minerals

Mixed layers → transitions between layered forms, more reactive than pure minerals

Examples → Imogolite and Allophane

Clay mineral transformation

Phyllosilicates (layer silicates)—especially micas—are the main precursors of clay minerals.

Physical weathering opens layer edges and removes interlayer K⁺, which is replaced by larger Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺.

This drives the transformation sequence mica → illite → vermiculite / smectite, and with further alteration can lead to kaolinite or chlorite.

Short summary clay minerals

Important secondary new formations in the soil (see «Weathering» for details)

They are subject to constant change, but their stability is usually significantly higher than that of primary silicates

Importance for soil

Clay minerals are components of the finest fraction of the soil, < 2 µm, = clay fraction

Storage for nutrients whose leaching is prevented

Microstructure makers in soil: particles adhere to each other, bind to themselves and to other coarse particles, expand and shrink etc..

Oxide and hydroxide of Fe, Al, Mn

They are final products of weathering of silicate minerals.

Weathering releases Fe, Al and Mn ions into the soil solution.

These ions are oxidised and then precipitate.

This forms iron, aluminium and manganese oxides and hydroxides.

Aluminium hydroxides: gibbsite

An aluminium hydroxide mineral formed during strong weathering.

Colourless to white.

Built from Al-octahedra (layered structure).

Forms only when silicon is very low in soil water.

Typical of intense weathering, especially in tropical regions.

Iron oxides and hydroxides

Iron oxides & hydroxides (overview)

Form during weathering of silicates when Fe²⁺ is released and oxidized to Fe³⁺

Give soils yellow–brown–red colours

Stable in oxic (aerobic) conditions, dissolve under reducing (anaerobic) conditions

Very important for nutrient and trace-element binding

Main types

Hematite (α-Fe₂O₃)

Red colour

Forms in warm, dry, well-aerated conditions

Typical of tropical and subtropical soils

Goethite (α-FeOOH)

Yellow–brown colour

Forms at moderate temperatures

Very stable, common in temperate soils

Lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH)

Orange colour

Forms under reducing / waterlogged conditions

Metastable, often local and temporary

Ferrihydrite (poorly crystalline Fe oxide)

Brown

Very young, poorly ordered (“rust”)

Forms during rapid oxidation, very reactive

Schwertmannite

Yellow–brown

Forms in acidic, sulphate-rich waters

Typical product of pyrite (FeS₂) weathering

Mn oxides

Manganese (Mn) oxides

Form during weathering of silicates

Mn²⁺ is oxidized to Mn⁴⁺, precipitating as Mn oxides

Main form

MnO₂

Black colour

Forms black mottles/concretions in hydromorphic soils

Immobile under aerobic conditions

Redox behaviour

Under reducing and acidic conditions:

Mn oxides dissolve

Mn²⁺ becomes mobile and colourless

Acid soils and permanently waterlogged soils → low Mn content

Soil importance

Bind trace elements under aerobic conditions

Release trace elements under anaerobic conditions

Behaviour very similar to Fe oxides

Oxides: indicators of soil formation

Goethite (FeOOH)

Forms in humid, wet climates

Indicates moderate weathering

No hematite → conditions too wet

Hematite (Fe₂O₃)

Forms in hot, tropical climates

Indicates intense weathering

Often together with goethite

Fe and Mn translocation (shifting)

Occurs in acidic, wet soils (e.g. Podzols)

Fe and Mn are mobilized under reducing conditions

Bleaching = loss of Fe/Mn

Accumulation horizons = re-precipitation under oxic or pH change

Salts

Carbonates

Main types:

Calcite (CaCO₃): white, reacts with HCl → CO₂

Dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂): less soluble, Mg source

Origin:

Primary minerals (e.g. limestone)

Secondary carbonates from weathering

Soil importance:

Neutralize acids (CO₂, organic acids)

Buffer soil acidification

Increase soil pH

Sulphates & Phosphates

Sulphates (from sulphuric acid):

Anhydrite: CaSO₄

Gypsum: CaSO₄·2H₂O

Phosphates (from phosphoric acid):

Apatite: main primary P mineral

Vivianite, Strengite: secondary Fe–phosphates

Soil importance:

Phosphates = key P source for soils and biosphere

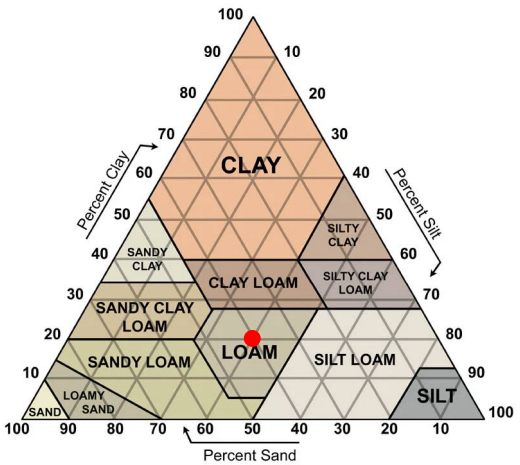

Grain size

Grain size = particle size of soil (also called texture).

It describes how soil particles are distributed by size.

Why grain size matters

Controls porosity (pore size and distribution)

Regulates water and air movement

Affects transport and retention of substances (filter function)

Influences biological activity

Controls erosion risk

Important for soil structure (microstructure)

Basic soil fractions

Fine earth: particles < 2 mm

Soil skeleton (coarse fraction): particles > 2 mm

Typical characteristics

Coarse fraction: mostly rounded grains, mainly SiO₂ (quartz)

Fine fraction: mostly flat/leafy particles, rich in mica and clay minerals

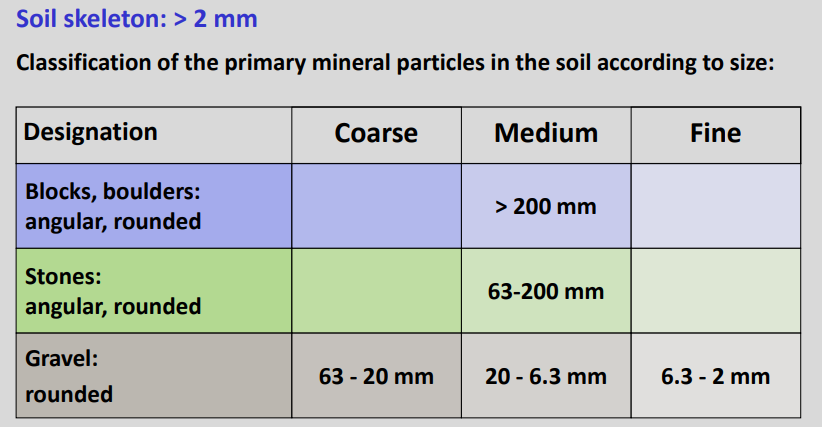

Soil skeleton

Fine earth fraction

It's used the logaritmic scale, and if you take 2 (the border between gravel and sand) then it's 63 the middle on the logaritmic scale

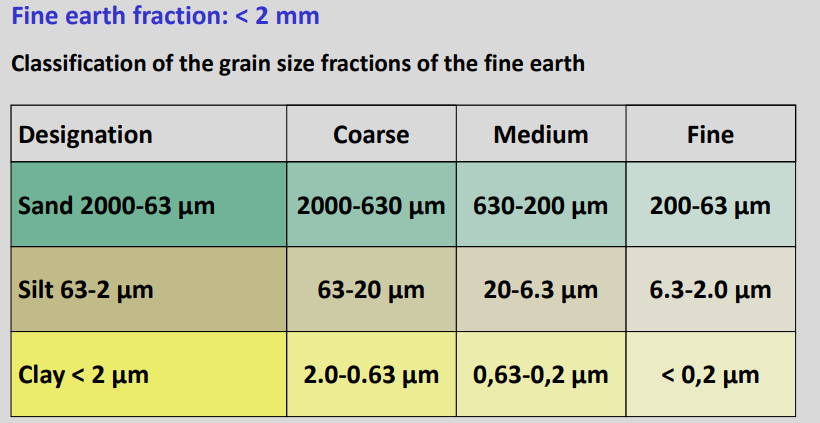

Mineral content in the grain fractions

Quartz: mainly sand (also silt)

Primary silicates (feldspars, pyroxenes, etc.): sand → silt

Micas: mainly silt (can weather to clay)

Clay minerals: clay (< 2 µm)

Fe/Al/Mn oxides & hydroxides: clay (very fine particles/coatings)

Rule of thumb:

Sand = quartz

silt = a bit of everything

clay = clay minerals and others

Grain size determination in the field

Finger test

Sand: gritty, loose, not sticky, no ribbon

Silt: smooth–floury, weak cohesion, no ribbon

Clay: sticky, plastic, shiny, forms long ribbon

Loam: intermediate; slightly plastic, short ribbon

Lab grain size determination

Sieve < 2 mm (fine soil only)

Remove binding material (salts & organic matter)

Measure with laser diffraction

Smaller particles → stronger laser scattering

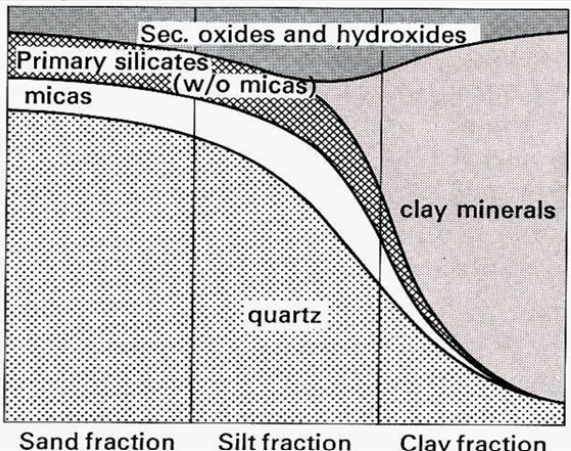

Grain size triangle

Grain size and soil functions

Physical effects

Sand: drains fast, low water storage

Silt: best water available to plants

Clay: slow drainage, high water storage (often stagnant)

Chemical effects

Sand: few nutrients, low buffering

Clay: many nutrients, high buffering

Pollutants

Finer grains (silt–clay) retain pollutants more than sand