Chapter 2 - Theories and Issues in Child Development

1/42

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

43 Terms

theory of development

a scheme or system of ideas that is based on evidence and attempts to explain, describe and predict behaviour and development.

In every area of development there are at least two kinds of theory:

minor: deal only with very specific, narrow areas of development;

major: explain large areas of development:

motor development;

cognitive development;

social-cognitive development;

evolution and ethology;

psychoanalytic theories;

humanistic theory;

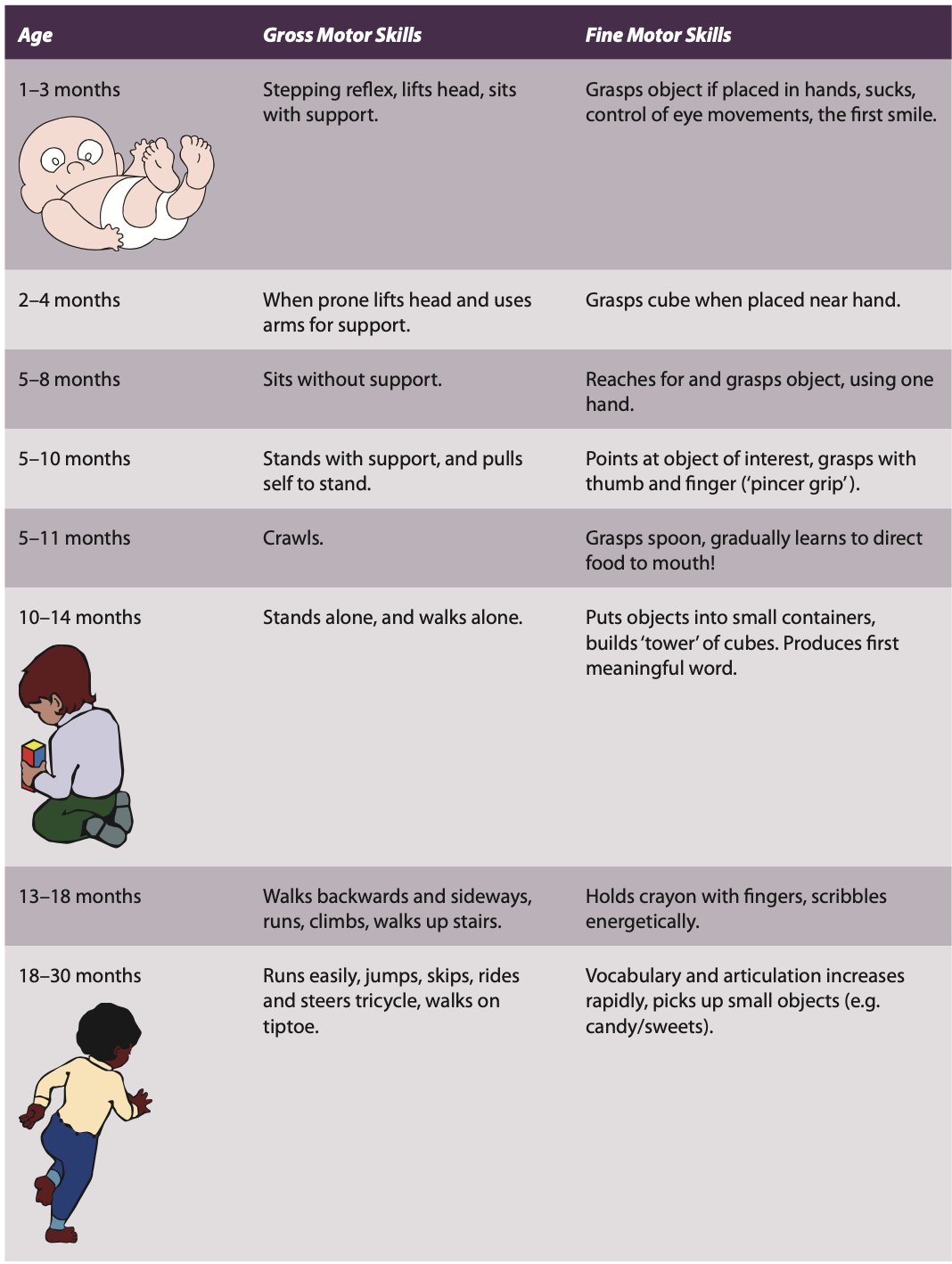

motor milestones

the basic motor skills acquired in infancy and early childhood, such as sitting unaided, standing, crawling, walking.

The ability to act on the world affects all other aspects of development, and each new accomplishment brings with it an increasing degree of independence (when infants begin to crawl they become independently mobile).

The different motor milestones emerge in a regular sequence – sitting with support, sitting unaided, crawling, standing, walking and climbing appear almost always in this order.

There is a considerable age range in which individual infants achieve each skill – for example, some infants crawl at 5 months while others are as late as 11 months.

motor development in infancy

At birth the infant has a number of well-developed motor skills, which include sucking, looking, grasping, breathing, crying – skills that are vital for survival.

However, the general impression of the newborn is one of uncoordinated inability and general weakness.

Movements of the limbs appear jerky and uncoordinated;

It takes a few weeks before infants can lift their head from a prone position.

The muscles are clearly unable to support the baby’s weight in order to allow such basic activities as sitting, rolling over or standing.

By the end of infancy, around 18 months, all this has changed. The toddler can walk, run, climb, communicate in speech and gesture, and use the two hands in complex coordinated actions.

maturational theories

Arnold Gesell concluded that motor development proceeded from the global to the specific in two directions:

cephalocaudal trend: from head to foot along the length of the body;

proximodistal trend: from the centre outwards to more peripheral segments.

→ these two invariant sequences of development + the regular sequence of the motor milestones led Gesell to the view that maturation alone shapes motor development:

Development is controlled by a maturational timetable linked particularly to the central nervous system and also to muscular development.

Each animal species has its own sequence and experience has little effect on motor development.

—

Myrtle McGraw tested pairs of twins where one member of each pair received enriched motor training (in reaching, climbing stairs etc.) and found that in the trained twin motor development was considerably accelerated when compared to the untrained twin.

The fact that motor skills develop in a regular sequence does not prove a genetic cause.

A maturational theory does not account for the considerable differences in the acquisition of various motor skills.

dynamic systems theory

= a theoretical approach applied to many areas of development which views the individual as interacting dynamically in a complex system in which all parts are intact.

The motor milestones are not set in stone: there are some infants who simply do not like to crawl and these will often stand and walk before they crawl. Those infants who do crawl will acquire it in their own individual ways.

Microgenetic studies of motor development: experimenters observe individual infants or children from the time they first attempt a new skill, such as walking or crawling, until it is performed effortlessly.

Infants’ acquisition of a new motor skill is much the same as that of adults learning a new motor skill – the beginnings are usually fumbling and poor, there is trial and error learning and great concentration, all gradually leading to the accomplished skilful activity, which then is usually used in the development of yet new motor skills

According to the dynamic systems theory all new motor development is the result of a dynamic and continual interaction of three major factors:

nervous system development;

the capabilities and biomechanics of the body;

environmental constraints and support.

Motor skills are learned, both during infancy and throughout life. The apparently invariant ordering of the motor milestones is partly dictated by logical necessity (you can’t run before you can walk!) and is not necessarily invariant (you can walk before you can crawl!).

→ emerging view of infants as active participants in their own motor-skill acquisition, in which developmental change is empowered through infants’ everyday problem-solving activities

dynamic systems theory: infant kicking

Esther Thelen (1999) tested 24 three-month-olds on a foot-kicking task: each infant was placed in a crib in a supine position and an ankle cuff was attached to one leg, and also attached by a cord to an overhead brightly coloured mobile. By kicking the leg the babies could make the mobile dance around and they quickly learned to make this exciting event happen. In this condition the other leg – the one that was not connected to the mobile movements – either moved independently or alternately with the attached leg.

Then Thelen changed the arrangement by yoking the legs together. She did this by putting ankle cuffs on both legs, and joining the two together with a strip of Velcro. What happened then was that the infants initially tried to kick the legs separately – because moving the legs alternately is the more natural action – but gradually learned to kick both together to get the mobile to move.

This study shows that the infants were able to change their pattern of interlimb coordination to solve a novel, experimentally imposed task.

dynamic systems theory: infant reaching

Thelen and Spencer (1998) followed the same four infants from 3 weeks to 1 year (a longitudinal study) in order to explore the development of successful reaching.

Infants acquired stable control over the head several weeks before the onset of reaching, then there was a reorganisation of muscle patterns so that the infants could stabilise the head and shoulder.

These developments gave the infants a stable base from which to reach, and successful reaching followed.

→ Infants need a stable posture before they can attain the goal of reaching successfully

→ New motor skills are learned through a process of modifying and developing their already existing abilities.

dynamic systems theory: infant walking

Newborn infants are extremely top heavy, with big heads and weak legs. Over the coming years their body weight is gradually redistributed and their centre of mass gradually moves downwards until it finishes slightly above the navel.

As infants grow, they constantly need to adjust and adapt their motor activities to accommodate the naturally occurring changes to their body dimensions.

Adolph and Avolio tested 14-month-olds by having them wear saddlebags slung over each shoulder. The saddle bags increased the infants’ chest circumference by the same amount in each of two conditions:

feather-weight – filled with pillow-stuffing, weighing 120 g

lead-weight – weighing 2.2 and 3.0 kg, which increased their body weight by 25 per cent and raised their centre of mass.

They found that the lead-weight infants were more cautious, and made prolonged exploratory movements – swaying, touching and leaning – before attempting to walk down a slope. That is, these infants were testing their new-found body dimensions and weight, and adjusted their judgements of what they could and could not do.

→ Infants do not have a fixed and rigid understanding of their own abilities, and have the dynamic flexibility to adjust their abilities as they approach each novel motor problem.

developmental psychology B.P. (before Piaget)

Developmental psychology was dominated by the influence of the two diametrically opposed theoretical views of behaviourism and psychoanalysis.

Despite the fact that they are strikingly opposed, they share one essential feature, which is that the child is seen as the passive recipient of their upbringing – development results from such things as the severity of toilet training, and of rewards and punishments.

American and British psychology was dominated by the theoretical school of thought known as behaviourism, which offered the mechanistic world view that the child is inherently passive until stimulated by the environment.

fundamental aspects of human development, according to Piaget

Children are active agents in shaping their own development, they are not simply blank slates who passively and unthinkingly respond to whatever the environment offers them. That is, children’s behaviour and development is motivated largely intrinsically (internally) rather than extrinsically.

For Piaget, children learn to adapt to their environments and as a result of their cognitive adaptations (children’s developing cognitive awareness of the world) they become better able to understand their world.

These more advanced understandings of the world reflect themselves in the appearance, during development, of new stages of development.

Piaget’s theory is therefore the best example of the organismic world view, which portrays children as inherently active, continually interacting with the environment, in such a way as to shape their own development.

Since children are active in developing or constructing their worlds Piaget’s theory is often referred to as a constructivist theory.

adaptation

In order to adapt to the world two important processes are necessary:

Assimilation is what happens when we treat new objects, people and events as if they were familiar – that is, we assimilate the new to our already-existing schemes of thought (we meet a new policeman and treat him as we habitually treat policemen).

Assimilation occurs from the earliest days – the infant is offered a new toy and puts it in their mouth to use the familiar activity of sucking.

Accommodation is where individuals have to modify or change their schemas, or ways of thinking, in order to adjust to a new situation (infants might be presented with a toy that is larger than those they have previously handled, and so will have to adjust their fingers and grasp to hold it).

It is worth stressing that assimilation and accommodation always occur together during infancy and the examples given above are both cases of assimilation and accommodation occurring together.

Throughout life the processes of assimilation and accommodation are always active as we constantly strive to adapt to the world we encounter. These processes are what can be called functional invariants in that they don’t change during development.

What do change are the cognitive structures (often called schemas) that allow the child to comprehend the world at progressively higher levels of understanding. According to Piaget’s view there are different levels of cognitive understanding.

schema

mental structures in the child’s thinking that provide representations and plans for enacting behaviours

Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development

Children move through four broad stages of development, each of which is characterised by qualitatively different ways of thinking.

the sensorimotor stage of infancy,

the preoperational stage of early childhood,

the concrete operations stage of middle childhood, and

the formal operations stage of adolescence and beyond.

sensorimotor stage

In Piaget’s theory, the first stage of cognitive development, whereby thought is based primarily on perception and action and internalised thinking is largely absent.

birth to 2 yo.

becoming a cognitive individual with a mind;

as a result of the infants’ actions on the objects and people in its’ environments;

the development of thought in action;

infants learn to solve problems, object permanence (objects continue to exist even though they cannot be seen or heard);

the infant (now a toddler whose language is developing rapidly) is able to reason through thought as well as through sensorimotor activities.

preoperational stage

the second stage of development described by Piaget in which children under the age of approximately 7 years are unable to coordinate aspects of problems in order to solve them.

2-7 yo.

Preschool children can solve a number of practical, concrete problems by the intelligent use of means-end problem solving, the use of tools, requesting objects, asking for things to happen, and other means. They can communicate well and represent information and ideas by means of symbols – in drawing, symbolic play, gesture, drawing and particularly speech.

These abilities continue to develop considerably, but there are some limitations to children’s thinking:

Children tend to be egocentric: find it difficult to see things from another’s POV);

Children display animism in their thinking: attribute life and lifelike qualities to inanimate objects, particularly those that move/are active.

Thinking tends to be illogical, magical - lack of logical framework for thought.

centration - the focusing or centering of attention on one aspect of a situation to the exclusion of others; fail conservation tasks.

concrete operations stage

the third Piagetian stage of development in which reasoning is said to become more logical, systematic and rational in its application to concrete objects.

7-11 yo.

master conservation - succeed in conservation tasks (tasks that examine children’s ability to understand that physical attributes of objects, such as their mass and weight, do not vary when the object changes shape).

formal operations stage

the fourth Piagetian stage in which the individual acquires the capacity for abstract scientific thought. This includes the ability to theorise about impossible events and items.

over 11 yo.

The concrete operations child becomes able to solve many problems involving the physical world, but the major limitation in their thinking is to do with the realm of possibilities. When children enter the formal operations stage – this limitation is removed.

The adolescent now becomes able to reason in the way that scientists do – to manipulate variables to find out what causes things to happen – and is also introduced to the realm of possibilities and hypothetical thought.

information processing approaches

information processing = the view that cognitive processes are explained in terms of inputs and outputs and that the human mind is a system through which information flows.

The theories and research we have described are motivated by multiple notions of information: the information available in the stimulus, the uptake of that information, the processing of the information by the individual, and the individual’s response.

Information processing accounts of human cognition include current views of memory formation (with terms such as encoding, storage, retrieval, strategies - knowledge used to solve particular problems, metamemory).

Rooted in:

the rapid and continuing advances in computer technology;

the view that an organism’s behaviour cannot be understood without knowing the structure of the perceiver’s environment (the structure of light reflected from objects);

constructivism: a theory about how perception fills in information that cannot be seen/heard directly (e.g. inferring the parts of an object that are hidden from view via processes of inference).

Piaget’s theoretical view that infants are not born with knowledge about the world, but instead gradually construct knowledge and the ability to represent reality mentally.

opposed behaviourism, whose principal tenet was that our knowledge of an organism is limited exclusively to what we can observe, and a position that avoided discussions of what goes on inside the mind.

→ Information processing theories focus on the information available in the external environment, and the means by which the child receives and interprets this information.

The task of the developing child is to use their perceptual systems – vision, hearing, touch, and so forth – to explore the world and obtain information about its properties. The information must be attended to, encoded, stored, retrieved and acted upon to build knowledge of objects and their characteristics.

cognitive development in infancy

According to the information processing approach, cognitive development proceeds in bottom-up fashion beginning with the ‘input’ or uptake of information by the child, and building complex systems of knowledge from simpler origins.

(This is opposed to top-down fashion in which the state of the system is specified or presumed, and then working to discover its components and their development, a view more consistent with nativist theory.)

For young infants, sensory and perceptual skills are relatively immature, and this may impose limits on knowledge acquisition. An important part of a research agenda, therefore, is investigations of how infants assemble the building blocks of knowledge.

A prominent example of this approach comes from the work of Les Cohen and colleagues, who asked how infants come to perceive causality. Two parameters are especially important to perceive causality: temporal and physical proximity.

When an event is arranged so that the second ball moves after a brief delay (violating temporal proximity) or before being contacted by the first ball (violating physical proximity), 6-month-old infants did not seem to perceive the event as causal.

→ the younger infants processed the lower-order units involved in the event but not the higher-order relations, and this suggests that development of causal perception between 4 and 6 months consists in noticing the higher-order, complex relations among objects and their motions.

A second example of the information processing approach comes from the work of Scott Johnson and colleagues, who asked how infants perceive object unity, as when two parts of an object are visible but its centre is hidden by another object – do infants perceive the visible parts to be connected?

Younger infants perceive the components but not the wholes – in this case, they perceive the parts of a partly hidden object but do not see it as a single unit.

Unity perception depends on the extent to which infants actually look at the object parts, as opposed to other parts of the scene.

→ Development of object perception, in particular object unity, therefore, consists again in detecting the higher-order relations among lower-order components.

cognitive development in childhood

In childhood, the task of building knowledge often comes down to determining which of the many ‘strategies’ are available to solve particular problems.

In the area of mathematics instruction: A typical approach involves examination of arithmetic strategies (learning to add by memorisation, counting on fingers) repeatedly in individual children as the school year progresses, and recording speed, accuracy and strategy use.

A number of strategic changes have been noted: incorporation of new strategies, identification of efficient strategies, more efficient execution of each strategy, and more adaptive choices among strategies.

There are stable individual differences in strategy choice, but children typically use multiple strategies at all points of assessment. Children hone their choices with experience and thus come to solve problems more quickly and accurately.

connectionism & brain development

connectionism = a modern theoretical approach that developed from information processing accounts in which computers are programmed to simulate the action of the brain and nerve cells (neurons).

Connectionist models are computer programs designed to emulate (model) some aspect of human cognition, including cognitive development.

The word ‘connectionist’ refers to the structure of the model, which consists of a number of processing units that are connected and that influence one another by a flow of activations.

This is analogous to the brain, which likewise consists of processing units (neurons) that are connected and activate one another (across synapses).

Connectionist models take in information and provide a response, coded in a way that a human can understand.

In between input and output are units, typically numbered in the dozens to the thousands, which process the information. The model learns by changing the activation strengths and connections among units.

It is provided with multiple opportunities to process the information, and often some sort of feedback on how it is doing between trials, as impetus to improve performance.

Initially the model has to guess at how it is to respond, but given enough training and feedback, it is capable of learning remarkably sophisticated kinds of information

There is no single model of cognitive development; modellers will choose a particular problem to emulate, design a model and a learning regimen, and probe the time course and nature of learning as it occurs.

Model of infant cognitive development that learned to discriminate the temporal and physical parameters that lead infants to perceive causality; appeared to represent truly causal events uniquely, as more than the sum of the parts.

Model of infants’ gaze patterns based on the idea of different brain systems that respond to specific visual features in an input image (luminance, motion, colour, orientation).

The model computed ‘salience’ based on competition among features, known to occur in real brains, and it directed its attention toward regions in the input of highest salience.

The question was how infants learn to direct their attention to a partly hidden object, as part of the more general question of perception of object unity.

The model learned to ‘find’ the object quickly and suggests that gaze control and salience, and the development of neural structures that support them, are a vital component of object perception in infancy.

information-processing vs. Piaget

in common:

Both attempt to specify children’s abilities and limitations as development proceeds;

Both try to explain how new levels of understanding develop from earlier, less advanced ones.

Both share a focus on ‘active’ participation by the child in their own development.

In both views, children learn by doing, by trying new strategies (and discarding many) and discovering the consequences, and learn by directing their attention appropriately.

differences:

Information processing approaches place great importance on the role of processing limitations in limiting children’s thinking and reasoning at any point in time, and also emphasise the development of stategies and procedures for helping to overcome these limitations.

Piaget’s theory does not discuss processing limitations, but rather discusses developmental changes in terms of the child gradually constructing logical frameworks for thought, such as concrete operations and formal operations.

Information processing accounts see development as unfolding in a continuous fashion, rather than in qualitatively different stages as Piaget suggested.

social-cognitive development: Vygotsky

Other researchers have been interested in the interaction between the child and their community – the social environment.

Vygotsky was one of the first to recognise the importance of knowledgeable adults in the child’s environment.

For him, the development of intellectual abilities is influenced by a didactic relationship (one based on instructive dialogue) with more advanced individuals.

Higher mental abilities are first encountered and used competently in social interactions, only later being internalised and possessed as individual thought processes (language).

There is a gap between what the child knows and what they can be taught.

At a given stage of development the child has a certain level of understanding, a temporary maximum. A little beyond this point lies the zone of proximal development (ZPD),

problems and ideas that are just a little too difficult for the child to understand on their own. It can, however, be explored and understood with the help of an adult.

Thus the adult can guide the child because they have a firmer grasp of the more complex thinking involved.

early behaviourism

Towards the end of the 19th century, psychology moved away from the subjective perspective of introspectionism (the analysis of self-reported perceptions) towards a more objective method.

This scientific approach to psychology had its roots in the work of Pavlov, who developed a grand theory of learning called classical conditioning. According to this theory, certain behaviours can be elicited by a neutral (normally unstimulating) stimulus simply because of its learned association with a more powerful stimulus.

Combined with other notions such as Thorndike’s law of effect (the likelihood of an action being repeated is increased if it leads to reward and decreased if it leads to punishment), behaviourism was born.

Behaviourism denies the role of the mind as an object of study and reduces all behaviour to chains of stimuli and the resulting response, the behaviour.

The early behaviourists’ view of child development was that the infant is born with little more than the machinery of conditioning and are warped by the environment throughout infancy and childhood. The child is passive and receptive and can be shaped in any direction.

This has been termed a reductionist perspective.

reductionism = the claim that complex behaviours and skills such as language and problem-solving are formed from simpler processes, such as neural activity and conditioning, and can ultimately be understood in these simpler terms.

B.F. Skinner’s behaviourism

Whilst the early behaviourists emphasised the passive nature of the child, Skinner envisioned a more active role.

Operant conditioning differs from classical conditioning because children operate (emit behaviours) on their environments.

It is still the case that the child’s development is dominated by their environment, but Skinner’s viewpoint allowed for more flexible and generative patterns of behaviour.

According to Skinner’s view it is possible to shape the animal’s or child’s behaviour by manipulating the reinforcement received.

Our behaviour is guided by reward and punishment.

social learning theory

Albert Bandura did not focus only on observable behaviour, but posited processing that occurred within the mind → sociobehaviourism, then social learning theory

= the application of behaviourism to social and cognitive learning that emphasises the importance of observational learning (learning by observation then imitating the observed acts).

Bobo doll experiment - infants observe adult playing with Bobo doll (control) and adult aggressively playing with Bobo doll (experimental).

→ Children from experimental group behaved in a more aggressive way towards their own Bobo doll.

Without obvious reinforcement, a particular behaviour had been learned. Bandura termed this observational learning/vicarious conditioning.

the child had mentally assumed the role of the observed person and taken note of any reinforcement.

→ children imitate the actions of others based on perceived reinforcement.

Later, Bandura developed the social cognitive theory of human functioning: development of social learning theory which emphasises humans’ ability to exercise control over the nature and quality of their lives, and to be self-reflective.

the ethological approach

Evolutionary theories of child development that emphasise the genetic basis of many behaviours, and point to the adaptive and survival value of these behaviours, are known as ethological approaches.

Certain behaviours in the young of many species are genetic in origin because they (i) promote survival and (ii) are found in many species, including humans.

One such behaviour is imprinting, which refers to the tendency of the newborn or newly hatched of precocial species of animals (which includes ducks, geese, sheep, horses) to follow the first moving objects they see. This behaviour involves the formation of an attachment between the infant and the mother.

There are two implications of ethology’s conception of behaviours:

For the most part, they require an external stimulus or target (imprinting needs a target ‘parent’)

Time. Originally, ethologists envisioned a critical period, this being the length of time for the behaviour to grow to maturity in the presence of the right conditions (e.g. language developing in a rich linguistic environment). When this critical period expires, the behaviour cannot develop.

These days, the evidence points towards a sensitive rather than critical period; behaviours may take root beyond this sensitive time period, but their development may be difficult and ultimately r*tarded

attachment theory

The prevailing belief, stemming from behaviourism, was that the attachment of infants to their caregivers was a secondary drive, that is, because the mother (or primary caregiver) satisfies the baby’s primary drives (these include hunger, thirst and the need for warmth) she acquires secondary reinforcing properties.

However, Bowlby pointed out that the need for attachment was itself a primary drive.

monkey experiment

Bowlby argued that there is an innate, instinctual drive in humans to form attachments that is as strong as any other primary drive or need. He put forward the principle of monotropy, which is the claim that the infant has a need to form an attachment with one significant person (usually the mother).

This claim was later found to be overstated, because it was found that infants often form multiple attachments, and that in some cases their strongest attachment was to people other than the mother, who did not fulfill basic caregiving activities, but who did engage in satisfying interactions with them.

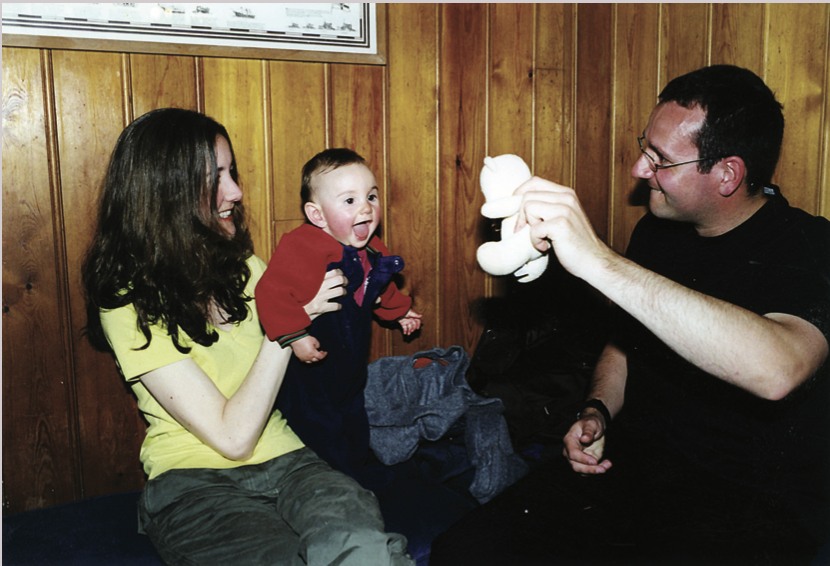

Bowlby believed that the attachment system between infant and caregiver became organised and consolidated in the second half of the infant’s first year from birth, and became particularly apparent when the infant began to crawl.

At this time, infants tend to use the mother as a ‘safe base’ from which to begin their explorations of the world, and it then becomes possible to measure how infants react to their mother’s departure and to her return.

Mary Ainsworth invented what is commonly called the strange situation, a measure of the level of attachment a child has with their parent. Using the strange situation Ainsworth discovered that there are several attachment ‘styles’ that differ in degree of security.

Their importance has been in demonstrating the importance of early secure attachments and showing that these attachments are as basic and important as any other human drive or motivation.

Freud

Freud claimed that much of our behaviour is determined by unconscious forces of which we are not directly aware. In presenting his psychoanalytic theory he suggested that there are three main structures to personality: the id, the ego and the superego.

The id is present in the newborn infant and consists of impulses, emotions and desires. It demands instant gratification of all its wishes and needs.

As this is impractical, the ego develops to act as a practical interface or mediator between reality and the desires of the id.

The final structure to develop is the superego, which is the sense of duty and responsibility – in many ways the conscience.

The ego and the superego develop as the individual progresses through the five psychosexual stages – oral, anal, phallic, latency and genital.

Freudian theory has been of immense importance in pointing out two possibilities:

One is that early childhood can be immensely important in affecting and determining later development

The other is that we can be driven by unconscious needs and desires of which we are not aware.

oral stage

birth to 1 yo.

The infant’s greatest satisfaction is derived from stimulation of the lips, tongue and mouth.

Sucking is the chief source of pleasure for the young infant.

anal stage

1-3 yo.

During this stage toilet or potty training takes place and the child gains the greatest psychosexual pleasure from exercising control over the anus and by retaining and eliminating faeces.

phallic stage

3 to 6 yo.

This is the time when children obtain their greatest pleasure from stimulating the genitals.

At this time boys experience the Oedipus complex: the young boy develops sexual feelings towards his mother but realises that his father is a major competitor for her (sexual) affections!

He then fears castration at the hands of his father (the castration complex) and in order to resolve this complex he adopts the ideals of his father and the superego (the conscience) develops.

In the Freudian account, for little girls the Electra complex is when they develop feelings towards their father and fear retribution at the hands of their mother. They resolve this by empathising with their mother, adopting the ideals she offers, and so the girl’s superego develops.

latency and genital stages

6 yo to adolescence.

From around 6 years the torments of infancy and early childhood subside and the child’s sexual awakening goes into a resting period (latency, from around 6 years to puberty and adolescence).

Then, at adolescence, sexual feelings become more apparent and urgent and the genital stage appears.

In the latter ‘true’ sexual feelings emerge and the adolescent strives to cope with awakening desires.

modern psychoanalysis

Anna Freud, the founder of child psychoanalysis: adolescence and puberty present a series of challenges, and during this period of ego struggle, the ego matures and is better able to defend itself through meeting these challenges.

Erik Erikson: personality formation was not largely complete by age 6 or 7 as Sigmund Freud suggested, but stages of psychological conflict occur throughout the lifespan; greater emphasis on the role of the broader social world (relatives, friends, society, culture) rather than parents and unconscious → psychosocial instead of psychosexual stages.

psychosocial stages: stages of development put forward by Erik Erikson. The child goes from the stage of ‘basic trust’ in early infancy to the final stage in adult life of maturity with a sense of integrity and self-worth.

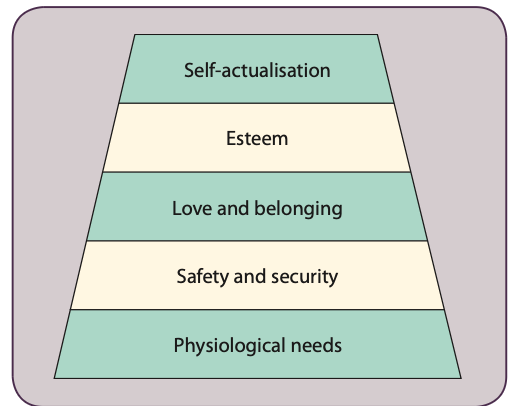

humanistic theory

Humanists argue that we are not driven by unconscious needs, neither are we driven by external environmental pulls such as reinforcement and rewards.

Rather, humans have free will and are motivated to fulfil their potential. The inner need or desire to fulfil one’s potential is known as self-actualisation.

The drive for self-actualisation is not restricted to childhood but is applicable across the life span, and a leading proponent of the humanistic view was Abraham Maslow

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs = stages of needs or desires in Abraham Maslow’s humanistic theory which go from the basic physiological needs for food and water to the ultimate desire for self-actualisation or the desire to fulfil one’s potential.

Maslow’s theory was not intended as a theory of children’s development – the hierarchy of needs is applicable at all ages from early childhood on, and children achieve goals and fulfil their potential as do adults.

gender development

Gender development concerns the important question of how it is that children grow up knowing that they are either a boy or a girl and that there are gender-appropriate behaviours associated with this difference.

gender development: cognitive explanation

According to Kohlberg’s account of gender development the child gradually comes to realise that she/he is a girl or a boy and that this is unchangeable – once a girl (or boy) always a girl (or boy), a realisation that is known as gender constancy.

Most children come to this realisation some time after 3 years, and almost all know it by age 7.

Kohlberg’s theory suggests that once children understand which gender they are they will develop appropriate gender-role behaviours. That is, knowing you are a girl or a boy helps the child to organise their behaviour to be gender-appropriate.

gender development: social learning explanation

The child is reinforced for what the parents and others perceive as being gender-appropriate behaviour (girls play with dolls, boys don’t cry).

Children imitate significant others and learn to observe same-gender models to see how to behave. In this way, through observation, imitation and reinforcement children’s gender roles are shaped.

gender development: psychoanalytic explanation

In the Freudian version of psychoanalytic theory a girl’s identification with her mother, and a boy’s with his father, develop from the resolution of the Electra and Oedipus complexes, as described above. As a result of this identification girls and boys form female and male identities (respectively!) and take on their same-gender parent’s views and behaviour as their own.

gender development: biological determinants

i ain’t reading allat

the nature-nurture issue

= ongoing debate on whether development is the result of an individual’s genes (nature) or the kinds of experiences they have throughout their life (nurture).

We are all of us a product of the interaction of the two broad factors of nature – inheritence or genetic factors – and nurture – environmental influences.

For example, it is argued that humans are genetically predisposed to acquire language, but which language we acquire is determined by the language(s) we hear and learn. It is important to note that without both factors no development could occur!

Nevertheless, people differ in their abilities, temperaments, personalities and a host of other characteristics, and psychologists and behaviour geneticists have attempted to estimate the relative contributions of nature and nurture to these individual variations between people.

stability versus change

It’s often claimed that early experiences influence current and later development. This view suggests that certain aspects of children’s development display stability, in the sense that they are consistent and predictable across time.

It turns out that development is characterised by both stability and change – for example, personality characteristics such as shyness, and the tendency to be aggressive tend to be stable, while others such as approach (the tendency to extreme friendliness and lack of caution with strangers) and sluggishness (reacting passively to changing circumstances) are unstable.

continuity versus discontinuity

Organismic theories, such as Piaget’s, emphasise that some of the most interesting changes in human development – such as those that accompany major changes in thinking, puberty and other life transitions such as first going to school, going to college, getting married, etc. – are characterised by discontinuity, by qualitatively different ways of thinking and behaving.

Mechanistic theories, as exemplified by behaviourist views, emphasise continuity – that development is reflected by a more continuous growth function, rather than occurring in qualitatively different stages.

What complicates things is that, as we have seen, it is often possible to think of the same aspect of development (such as intelligence) as being both continuous and discontinuous.