Cancer Genetics

1/51

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

52 Terms

Cancer

a group of diseases characterized by ______ (controllable/uncontrollable) growth and spread of ______ (normal/abnormal) cells

______ multiplication/_______ leads to the formation of a lump of tissue or tumor

tumor cells invade the __________ tissues and may travel to a distant site to form new tumors

the process by which tumor cells spread to distant sites is called ______

uncontrollable, abnormal

uncontrolled, proliferation

surrounding

metastasis

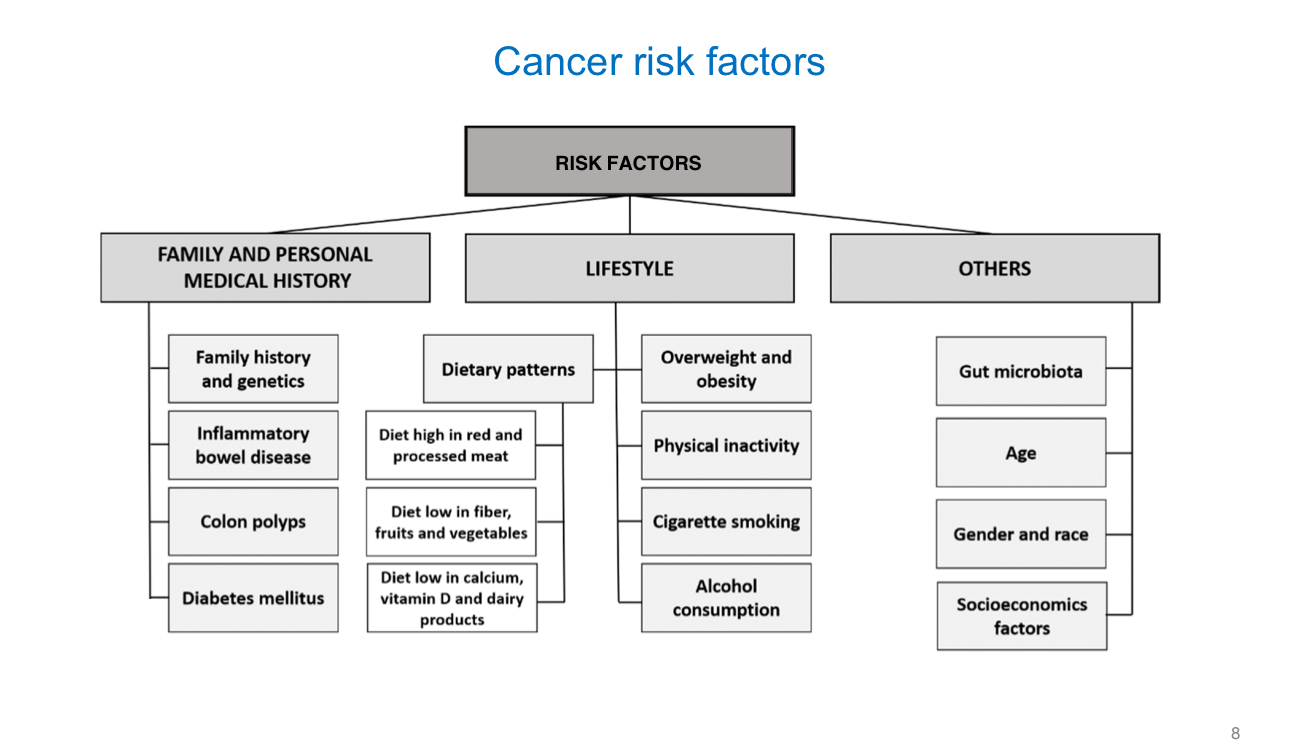

Cancer Risk Factors

Carcinogens —> substances capable of causing cancer

Lifestyle Factors —> ______, ______, ______ light, ______ fat diet

Environmental Factors —> ______ radiation + ______ radiation

Chemical Agents —> ______ drugs, certain ______ agents, ______ ______

Infectious Agents —> (4)

smoking, alcohol, UV, high

UV, ionizing

immunosuppressive, antineoplastic, coal tar

hepatitis B/C, HIV, HPV, H. pylori

Etiology of Cancer

not fully ______

carcinogenesis is a ______ process regulated by ______ —> ______ steps

initiation: exposure to ______ that causes DNA damage —> ______ mutation

promotion: growth of ______ cells —> pre-neoplastic lesion —> ______ (reversible/irreversible)

conversion: mutated cell becomes ______ occurs __________ years after prior stages —> ______ (reversible/irreversible)

progession: further ______ changes, tumor ______ into local tissues, distant ______ —> ______ (reversible/irreversible)

understood

multistep, genes, four

carcinogen, irreversible

mutated, reversible

cancerous, 5-20, irreversible

genetic, invasion, metastases, irreversible

Tumor Origin and Classification

tumors arise from any _____ type and may be named based on tissue type:

epithelial —> ______

connective (muscle, bone, cartilage) —> ______

lymphoid/blood/bone marrow —> ______, ______, ______

tumors may also be classified as:

______ site —> lung, colon, etc.

degree of ______ (poorly differentiated vs. well differentiated)

______ (insulinoma)

______ or ______

tumors that end in “-oma” —> ______

tumors that end in “-carcinoma” —> ______

a tumor is treated according to the site of ______

tissure

cacinoma

sarcoma

lymphoma, leukemia, myeloma

anatomic

differentiation

function

benign, malignant

benign

malignant

origination

Benign vs. Malignant Tumors

Benign

grow ______

______ capsule

______ (non-invasive/invasive)

______ (well/poorly) differentiated

______ (high/low) mitotic index

______ (does/does not) metastasize

Malignant

grow ______

______ encapsulated

______ (non-invasive/invasive)

______ (well/poorly) differentiated

______ (high/low) mitotic index

______ (does/does not) metastasize

slowly

well-defined

non-invasive

well

low

does not

rapidly

non

invasive

poorly

high

does

Benign Tumor Complications

Benign tumors can still cause complications such as:

__________

Brain tumors → __________ effects

Secretion of __________ (e.g., thyroid adenoma → thyroid hormone; pituitary adenoma → growth hormone)

Leiomyoma → __________ and __________ symptoms

pain

CNS

hormones

heavy menstrual bleeding, urinary

Cancer Diagnosis

requires a ______ (tissue sample) for pathological diagnosis

Types include:

______/______ biopsy

______ biopsy

______ cytology

biopsy

incisional/excisional

needle

exfoliative

Cancer Staging (TNM System)

staging is based on tumor ______, ______ ______ involvement, and ______

T (tumor):

Tx = tumor cannot be __________

Tis = carcinoma __________

T0 = no __________ of tumor

T1–T4 = size or extent of __________ tumor

N (node):

Nx = node cannot be __________

N0–N3 = degree of __________ to regional lymph nodes

M (metastasis):

M0 = ______ distant metastasis

M1 = __________ of distant metastasis

Stage I: ______ prognosis

Stage IV: ______ prognosis

size, lymph node, metastasis

evaluated

in situ

signs

primary

evaulated

spread

no

presence

best

worst

Cell Division and Cell Cycle

Interphase consists of three phases:

G₁ phase – gap between __________ and __________ phase

S phase – where __________ occurs

G₂ phase – gap between __________ and __________ phase

G₁ and G₂ allow __________.

M (mitotic), S (synthesis)

DNA replication

S, M

cell growth

How does cancer develop?

cancer is a ______ disease and ______ process that takes time to develop —> often years

it arises through a series of ______ alterations in DNA

a ______ mutation does not necessarily lead to cancer —> _____ mutations must also occur

usually, about ______ mutations are required for development of most cancers

at each step, mutated cells gain a __________ advantage, leading to __________ of those cells

the most important genetic alterations occur in __________ and __________

genetic, multi-step

somatic

germline, somatic

three

growth, expansion

tumor suppressor genes, proto-oncogenes

Germline vs. Somatic

Germline:

______ (inherited/acquired)

found in ______ and ______ cells and EVERY cell in the body

Somatic:

______ during a person’s lifetime

______ to specific cells/tissues

inherited

egg, sperm

acquired

limited

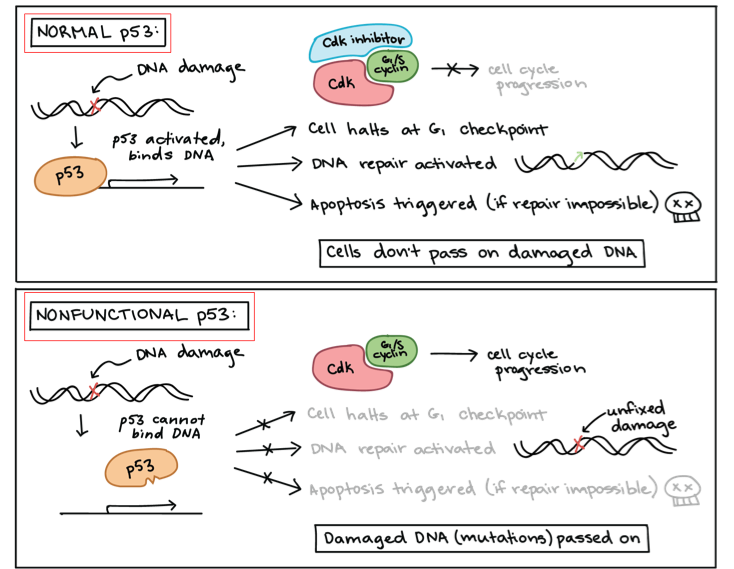

Tumor Suppressor Genes in Cancer Development

normally suppresses ______ ______, repair ______ mistakes or induce ______

inactivation of tumor suppressor genes can lead to ______ development

Mechanisms of Inactivation:

______ mutations

______/______

gene ______ —> epigenetic change

cell division, DNA, apoptosis

Tumor Suppressor Genes —> Examples

______

BRCA 1/2 → drug class: __________ inhibitors → example: __________

Retinoblastoma (Rb) → drug class: __________ inhibitors → example: __________

p53

PARP, olaparib

CDK4/6, palbociclib

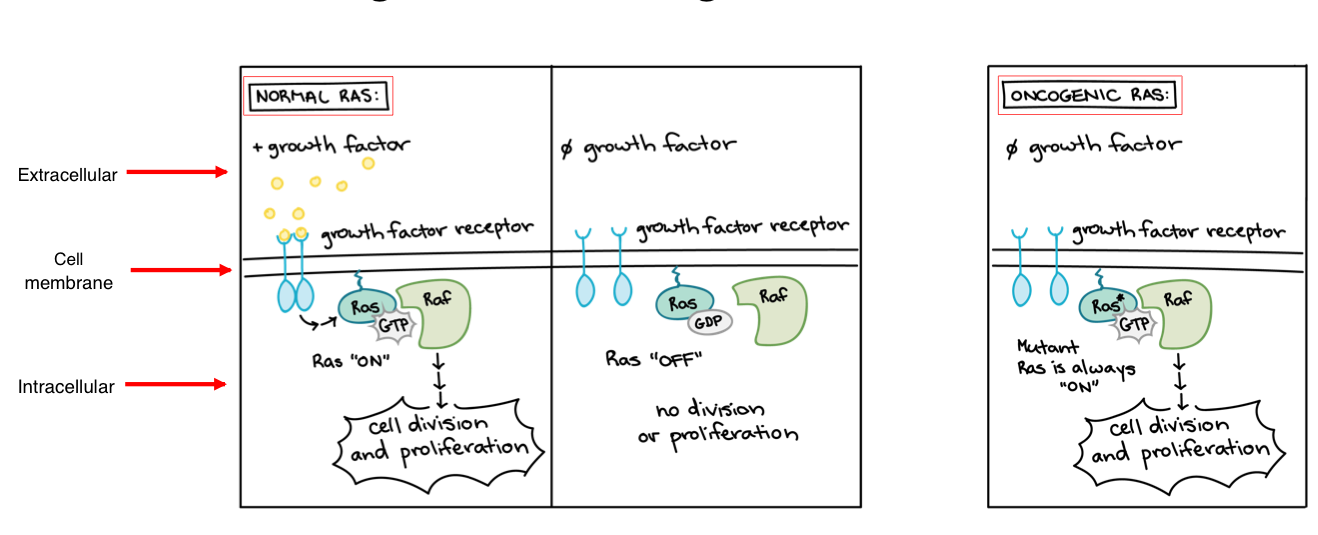

Porto-Oncogene in Cancer Development

promote ______ ______ or reduce occurrence of ______

when proto-oncogene mutates, they become ______ due to the over-activation of the gene

over-activation = ______ development

mechanisms of oncogene activation:

______ mutation —> RAS

DNA ______ —> HER2

chromosomal ______ —> BCR-ABL

cell division, apoptosis

oncogene

cancer

point

amplification

rearrangement

Oncogene Examples

RAS → inhibitor: __________

EGFR → inhibitor: __________

HER2 → inhibitor: __________

VEGF → inhibitor: __________

BCR-ABL → inhibitor: __________

sotorasib

osimertinib

trastuzumab

bevacizumab

imatinib

Retinoblastoma (Rb): Tumor Suppressor Genes

>70% of human tumors have a mutation that leads to the ______ or ______ of Rb

normally, Rb inhibits the ______ ______ by inhibiting transcription factors such as ______

CDK 2, 4, and 6 inactivate Rb via ______, releasing transcription factors that allow progression from ______ to ______ phase

relevant drug class —> ______ inhibitors —> ______ (Ibrance)

these drugs inhibit Rb ______/______, restoring Rb’s ability to suppress the cell cycle

used in the treatment of ______ cancer

loss, inactivation

cell cycle, E2F1-3

phosphorylation, G1, S

CDK 4/6, palbociclib

phosphorylation/inactivation

breast

BCRA1/BCRA2: Tumor Suppressor Genes

involved in the ______ ______ (HRR) repair pathway, which repairs ______ DNA (dsDNA) breaks

cells with BRCA1/2 mutations are deficient in their ability to repair dsDNA breaks and must rely on ______ repair mechanisms such as ______ ______ repair (BER)

BER is mediated by ______

relevant drug class: ______ inhibitors —> ______ (Lynparza)

PARP inhibitors block the alternative repair pathway used by ______ cells, leading to cell death through ______ ______

used in the treatment of ______, ______, ______ cancers

homologous recombination, double-stranded

alternative, base excision

PARP1

PARP, olaparib

BRCA-deficient, synthetic lethality

prostate, breast, ovarian

BCR-ABL: Oncogene

present in cells with translocation of chromosomes ______ and ______

the gene product (BCR-ABL fusion protein) has constitutive ______ ______ activity, which activates signaling pathways via ______ of substrates

relevant disease state: ______ ______ ______ (CML)

relevant drug class: ______ inhibitors —> ______ (Gleevec)

BCR-ABL inhibitors bind to the ______ domain and block the ______ of the substrate

, 22

tyrosine kinase, phosphorylation

chronic myelogenous leukemia

BCR-ABL, Imatinib

kinase, phosphorylation

what is the first drug to inhibit a gene product that is only found in cancers?

Imatinib (Gleevec)

Growth Factors: Oncogenes

Several mechanisms in oncogenesis:

______ of growth factors

______ ______ of growth factor receptors

______ of growth factor receptors

Example: ______ ______ growth factor (VEGF)

relevant drug class: ______ inhibitors —> ______ (Avastin and biosimilars)

MOAs:

bind the growth factor (VEGF A/B) —> ______

bind the VEGF receptor to block binding of VEGF —> ______

inhibit VEGF receptor’s intracellular kinase —>

VEGF targeting agents inhibit ______

overproduction

activating mutations

overexpression

vascular endothelial

VEGF, bevacizumab

bevacizumab

ramucirumab

sunitinib

angiogenesis

Relevant Mechanisms of Drug Resistance

Changes in target

Acquisition of ______ mutation in gene

Upregulation of ______

Change in the affected pathway

Use of ______/______ or enhanced DNA repair pathways

Develop new ______/______ to bypass effects of the drug

Epigenetic changes

Turn genes __________ that affect treatment response

Development/enhancement of ______ ______ mechanism

new

expression

alternative/enhanced

pathways/signals

on/off

drug efflux

Cancer is a heterogeneous disease

Tumors have unique genomic and phenotypic features that vary at multiple levels.

Genetic heterogeneity:

Cells within a single tumor are not genetically identical.

Mutations accumulate over time during tumor growth.

Many mutations are passenger mutations (not clinically significant).

Driver mutations promote tumor growth/progression and are often actionable/druggable.

Levels of Cancer Heterogeneity

Cancer heterogeneity occurs across three major levels:

Intratumor heterogeneity

Differences among cells within one tumor mass.

Multiple subclones exist inside a single tumor.

Intertumor heterogeneity

Differences between a patient’s primary tumor and their metastatic tumors.

Interpatient heterogeneity

Differences between tumors found in different patients.

Why is tumor heterogeneity important?

1. Interpatient heterogeneity

Different tumor types require different treatments (e.g., breast cancer vs prostate cancer).

Even tumors of the same type may need different treatments due to differences in each patient’s tumor genetics.

This concept forms the basis of precision medicine, where treatments are tailored to the specific molecular features of each patient’s cancer.

2. Intratumor and Intertumor heterogeneity

These types of heterogeneity can strongly influence drug response and resistance.

If all tumor cells shared the same genetic makeup, they would likely respond uniformly to therapy.

However, because tumors contain multiple genetically distinct subclones:

Some cells may respond to treatment.

Others may survive and lead to treatment failure or resistance.

This genetic diversity makes it less likely that a single therapy will eliminate all tumor cells.

Intratumor / Intertumor heterogeneity

The effectiveness of targeted therapy depends on whether the target mutation is present in all tumor cells.

Example: If a tumor has an EGFR mutation, an EGFR inhibitor can produce a complete response only if every tumor cell carries the mutation.

If some cells lack the mutation → they survive, leading to resistance and tumor regrowth.

Combining drugs with different mechanisms of action may help eliminate diverse tumor cell populations and reduce resistance.

Models of Tumor Heterogeneity

1. Clonal Evolution (CE) Model

All malignant cells start as biologically similar.

Over time, they accumulate genomic or epigenetic alterations in a stepwise manner.

Selective pressures cause certain clones to expand while others die out.

This creates genetically diverse subpopulations within the tumor.

2. Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) Model

Tumor contains a small subset of cancer stem cells (CSCs).

CSCs:

Have the ability to self-renew.

Generate the heterogeneous populations of cancer cells in the tumor.

Only CSCs drive tumor growth, progression, and recurrence.

3. Plasticity Model (unites both CE and CSC models)

Cancer cells can interconvert:

Differentiated cancer cells ↔ cancer stem–like cells.

This means tumors can shift between CE-like evolution and CSC-driven behavior.

Clinical Application of Tumor Heterogeneity Models

Clonal Evolution (CE) Model

If this model is correct:

Most cells in the tumor can proliferate, metastasize, and contribute to disease progression.

Therapeutic implication:

Treatments must aim to eliminate most or all tumor cells, since many cells have malignant potential.

Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) Model

If this model is correct:

Only a small subset of cancer stem cells (CSCs) drive tumor initiation, growth, and progression.

Therapeutic implication:

Therapies should specifically target CSCs, because eliminating them could prevent tumor recurrence and progression.

Therapeutic Options Are Driven by Tumor Heterogeneity

Treatment depends on both:

Tumor type

Presence of actionable genetic alterations

Examples:

Cancer Type | Common Treatment (no mutation identified) | Targeted Treatment (if mutation identified) |

|---|---|---|

Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Platinum + Taxane | - PD-L1 > 50%: PD-1 inhibitor - EGFR mutation: EGFR inhibitor - ALK rearrangement: ALK inhibitor |

Breast cancer | Anthracycline + Alkylating agent | - HER2+: trastuzumab, pertuzumab, docetaxel - Hormone receptor+: antiestrogen + CDK4/6 inhibitor |

Take-home points

Treatments differ based on tumor type and tumor genetics.

When cancer recurs, new mutations may appear, so re-testing is often needed to guide therapy.

Precision / Personalized Medicine

What is it?

A major clinical application of tumor heterogeneity.

Precision medicine = tailoring prevention and treatment strategies to the specific characteristics of the patient and their tumor.

Factors include genes, environment, and lifestyle.

In cancer therapeutics, this means:

Choosing treatment based on the tumor’s specific molecular alterations.

Key concept: Treatment is not one-size-fits-all.

How Precision Medicine Works in Cancer

Guided by genetic and biomarker testing

Tumors are tested for mutations or biomarkers that may determine which therapies will be effective.

Alterations can pinpoint whether targeted therapies (e.g., EGFR inhibitors, HER2 therapies, PD-1 inhibitors) should be used.

Somatic vs. Germline mutation testing

Somatic mutations

Occur in tumor cells only (not inherited).

Testing is usually done on a tumor biopsy sample.

Some assays use blood to detect circulating tumor DNA.

Germline mutations

Inherited mutations present in all cells.

Testing is done using:

Cheek swab

Saliva

Blood sample

Precision / Personalized Medicine: How it Works

Step-by-step process

Patient is diagnosed with cancer.

A tumor sample is sent for mutation/biomarker analysis.

The analysis identifies actionable or druggable targets

Examples: mutations, fusion proteins, other biomarkers.

Therapy is selected based on the actionable targets found.

This ensures treatment is tailored to the tumor’s specific molecular profile.

Mutation / Biomarker Analysis in Precision Medicine

Companion Diagnostics (CDx)

Defined as:

A medical device, often an in vitro diagnostic test, that provides information essential for the safe and effective use of a corresponding drug or biologic.CDx tests determine which patients can benefit from certain targeted therapies.

They identify mutations or alterations that are required for treatment with specific drugs (e.g., EGFR inhibitors, HER2 therapies, PARP inhibitors).

Examples of CDx tests

FoundationOne (comprehensive genomic profiling)

BRACAnalysis (BRCA1/2 mutation testing)

Precision/Personalized Medicine: Mutation/Biomarker Analysis

Key Points

Some drugs are approved only for patients who have specific genetic alterations or mutations.

These drugs often must be paired with an FDA-cleared Companion Diagnostic (CDx).

Companion Diagnostics (CDx) identify whether a patient’s tumor contains the required mutation/alteration.

This determines whether the patient is eligible for the targeted therapy.

The FDA maintains a searchable list of all cleared or approved CDx devices (in vitro and imaging tools).

Case

A 67-year-old patient has relapsed acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The oncology fellow asks whether the patient is a candidate for enasidenib (Idhifa), a targeted therapy.

Key Question:

What information do we need to make a recommendation?

Answer

We need to know whether the patient’s AML cells have an IDH2 mutation.

Why?

Enasidenib is FDA-approved ONLY for AML patients with an IDH2 mutation, confirmed by an FDA-approved diagnostic test.

Without the mutation, the drug would not be effective and should not be used.

Precision / Personalized Medicine: Tumor/Tissue/Site-Agnostic Indications

Key Concept

Precision medicine has led to tumor-agnostic (or tissue-agnostic) drug approvals.

Tumor-agnostic indication =

The FDA approval does not specify a tumor type or location.

Instead, the drug is approved only based on the presence of a specific molecular alteration, regardless of where the cancer originated.

Important Features

Any tumor type can be treated if the required mutation or molecular feature is present.

Example: A drug may be used for colon cancer, lung cancer, or thyroid cancer as long as the tumor has the same actionable mutation.

Examples of Precision Medicine Approvals

Typical FDA-approved indications (tumor-specific)

These are approved for specific cancer types:

Tisotumab vedotin (Tivdak)

For cervical cancer that has progressed after ≥1 prior therapy.

Osimertinib (Tagrisso)

For non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with

EGFR exon 19 deletion or

EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation (mutation-positive).

Tumor/Tissue/Site-Agnostic FDA-approved indications

These drugs are approved based solely on a molecular alteration, not tumor type:

Larotrectinib (Vitrakvi)

For solid tumors with an NTRK gene fusion.

Dabrafenib (Tafinlar)

For solid tumors with a BRAF V600E mutation.

DNA Packaging: Chromatin and Chromosomes

DNA → Chromatin → Chromosome

DNA alone is a double-stranded molecule.

Chromatin = DNA + structural proteins (mainly histones).

This is the default form of DNA in the nucleus.

Chromosome = the fully condensed, organized structure of chromatin formed during cell division(mitosis/meiosis).

Chromatin vs. Chromosomes

Chromatin

Definition: DNA + histone proteins that package DNA in the nucleus.

Physical State: Loosely packed (variable).

When Present: Throughout the cell cycle, especially interphase.

Function:

Allows gene expression

Allows DNA replication and repair

Types:

Euchromatin: loosely packed, transcriptionally active

Heterochromatin: tightly packed, transcriptionally silent

Chromosome

Definition: Condensed, tightly organized form of chromatin seen during cell division.

Physical State: Tightly packed and coiled.

When Present: Visible during mitosis and meiosis (especially metaphase).

Function: Ensures accurate segregation of DNA to daughter cells.

Form: Discrete structures, each containing one DNA molecule plus associated proteins.

Organization of Eukaryotic Chromosomes

Nucleosomes

Fundamental repeating units of chromatin.

Made of:

Double-stranded DNA wrapped around

Histone proteins (forming “beads on a string”).

Chromatin Structure Hierarchy

DNA wraps around histones → nucleosomes

Nucleosomes coil → chromatin fiber

Chromatin fibers loop and condense further

Highly condensed chromatin folds → chromosome

This hierarchical packaging allows:

Large amounts of DNA to fit inside the nucleus

Controlled access for transcription, replication, and repair

Nucleosome Structure

Histones

There are 5 types of histone proteins:

H2A, H2B, H3, H4 (core histones)

H1 (linker histone)

Histones contain a high percentage of positively charged amino acids (e.g., lysine, arginine).

These “+” charges attract the “–” charges on DNA’s phosphate backbone, resulting in strong DNA–histone interaction.

DNA and histones are tightly associated, enabling efficient packaging.

Nucleosome Components

Histone Core (Octamer)

Formed by:

2 copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4

This octamer is the “spool” that DNA wraps around.

DNA Wrapping

~147 base pairs of DNA wrap around the histone octamer.

Histone tails extend out from the core and help maintain DNA binding.

Role of Histone H1

H1 binds DNA at the entry and exit points where DNA joins and leaves the nucleosome.

Acts like a clamp:

Locks DNA in place.

Helps stabilize higher-order chromatin structure.

Epigenetics

What is epigenetics?

The study of how cells control gene expression without changing the DNA sequence.

Epigenetic changes allow cells to regulate gene activity in a reversible, non-permanent way.

Key Features

Epigenetic modifications:

Can be maintained through cell divisions.

Can sometimes be inherited across generations.

They do not alter the underlying DNA sequence—only gene expression patterns.

Relevance to Cancer

Epigenetic changes can contribute to cancer development by:

Reducing transcription of tumor suppressor genes

→ leads to decreased protection against uncontrolled cell growth.Increasing transcription of oncogenes

→ promotes abnormal cell proliferation.

Because of this, epigenetic mechanisms are targets for anticancer therapies.

Modes of Epigenetic Modifications

Epigenetic changes regulate gene expression without altering the DNA nucleotide sequence.

These modifications are also targetable by drugs, making them important in cancer therapy.

Three major modes of epigenetic regulation:1) DNA Modification

Typically refers to DNA methylation (addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases).

Usually silences gene expression.

2) Histone Modification

Includes acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, etc.

Alters how tightly DNA is wound around histones.

Acetylation → loosens chromatin → increases transcription

Deacetylation → tightens chromatin → decreases transcription

3) Noncoding RNA

miRNAs, lncRNAs, and others regulate gene expression by:

Binding mRNA

Affecting translation

Influencing chromatin structure

DNA Modification

What is DNA methylation?

The most common type of epigenetic modification.

Involves the addition of a methyl group (CH₃) to DNA.

Methylation occurs without altering the DNA sequence itself.

Effects on Gene Expression

Hypermethylation (increased methylation):

Reduces transcription → gene is “turned off.”

Often occurs at gene promoters.

Hypomethylation can lead to inappropriate gene activation.

Relevance to Cancer

Abnormal methylation patterns can silence tumor suppressor genes.

These changes can contribute to cancer development and progression.

DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs)

What do DNMTs do?

DNMTs add methyl groups to DNA.

Three major types:

DNMT1

DNMT3A

DNMT3B

Mechanism

All three DNMTs transfer a methyl group to the C5 position of cytosine, forming:

5-methylcytosine

This modification is key for:

Gene regulation

Chromatin structure

Stable inheritance of epigenetic marks during cell division

DNA Methylation in Tumorigenesis

How abnormal methylation contributes to cancer

Cancer is associated with two major methylation abnormalities:

1. Genome-wide hypomethylation

Leads to:

Activation of proto-oncogenes

Genomic instability

This promotes tumor initiation and progression.

2. Promoter hypermethylation

Leads to:

Silencing of tumor suppressor genes

Example: Overactivity of DNMT1 causes excessive methylation → tumor suppressor genes are turned off → cancer progression.

Example

DNMT1 is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer, contributing to hypermethylation and gene silencing.

Targeting DNA Methylation to Treat Cancer

Decitabine (5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine)

Drug class

Hypomethylating agent (HMA)

DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitor

Clinical use

Treats:

Leukemia

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)

These conditions often involve hypermethylation and gene silencing.

Mechanism of Action

Decitabine is a cytosine analog.

During DNA replication:

It becomes incorporated into DNA.

DNMT1 binds to decitabine and becomes covalently trapped and inactivated.

This causes depletion of active DNMT1.

Result

Reduced DNA methylation

Increased transcription of silenced genes, promoting:

Cell differentiation

Reduced proliferation

Apoptosis

This reverses the hypermethylated, gene-silencing environment that drives cancer.

Histone Modification

Histone modifications change how tightly DNA interacts with histone proteins.

These changes regulate chromatin structure, which in turn regulates gene expression.

Modifications occur mainly on histone tails.

Types of Histone Modifications

Acetylation*

Methylation*

Phosphorylation

Ubiquitination

These modifications can either:

Disrupt histone–DNA interactions → loosen chromatin → ↑ gene expression, or

Strengthen histone–DNA interactions → tighten chromatin → ↓ gene expression

Histone Acetylation

Acetylation

Adds a negative charge to lysine residues on histone tails.

Negative histone tails repel negatively charged DNA.

Leads to:

Chromatin relaxation (euchromatin)

Increased gene expression

Deacetylation

Removes the negative charge from lysines.

DNA binds more tightly to histones.

Leads to:

Condensed chromatin (heterochromatin)

Reduced gene expression

Regulation of Acetylation/Deacetylation

HATs — Histone Acetyltransferases

Add acetyl groups.

Promote open chromatin and gene activation.

HDACs — Histone Deacetylases

Remove acetyl groups.

Promote closed chromatin and gene repression.

Cancer Connection

Imbalance in acetylation can promote cancer progression.

HDAC is overexpressed in many cancers, contributing to tumor suppressor gene silencing.

Targeting HDAC to Treat Cancer

Vorinostat (Zolinza)

Drug Class

HDAC inhibitor

Indication

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

Mechanism

Inhibits HDAC → prevents removal of acetyl groups

Increases histone acetylation, restoring normal gene expression

Reactivates tumor suppressor genes

Promotes:

Cell cycle arrest

Differentiation

Anti-tumor effects

Histone Methylation

Key Concepts

Histone methylation can increase OR decrease gene expression depending on:

Which amino acid on the histone is methylated

How many methyl groups are added (mono-, di-, tri-methylation)

Enzymes involved

Histone methyltransferases (HMTs)

Add methyl groups → increase methylation

Histone demethylases (HDMs)

Remove methyl groups → decrease methylation

Cancer Connection

Imbalances in methylation enzymes can disrupt normal gene regulation.

This may lead to:

Abnormal gene silencing

Oncogene activation

Cancer development

Targeting Histone Methylation to Treat Cancer

Tazemetostat (Tazverik)

Drug Class

Histone methyltransferase (HMT) inhibitor

Target

Specifically inhibits EZH2 (a key HMT)

Indication

Relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma

Normal Function of EZH2

EZH2 adds methyl groups to histones (especially H3K27)

This increases methylation → gene silencing

Overactivity of EZH2 blocks differentiation and promotes cancer cell survival.

Mechanism of Tazemetostat

Inhibits EZH2 → decreases histone methylation

Allows previously silenced genes to be transcribed again, including:

Genes controlling the cell cycle

Genes promoting apoptosis

Effects in Cancer Cells

Restores normal gene expression

Leads to:

Cell cycle arrest

Differentiation

Apoptosis

Targeting Histone Methylation to Treat Cancer

Follicular Lymphoma (Untreated)

EZH2, part of the PRC2 complex, adds methyl groups to histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3).

This methylation leads to:

Gene repression → tumor suppressor genes (e.g., IRF4, PRMD1, CDKN1A, CDKN2A) are turned off.

As a result:

Cancer cells do not differentiate

Cancer cells continue proliferating

Bottom line:

Overactive EZH2 = too much histone methylation = silencing tumor suppressor genes → lymphoma growth.

Follicular Lymphoma Treated with Tazemetostat

Tazemetostat inhibits EZH2, preventing H3K27 methylation.

This reduces gene silencing and allows key genes to be activated, including:

IRF4

PRMD1

CDKN1A

CDKN2A

Consequences in cancer cells:

Gene activation restored

Cell cycle arrest

Apoptosis (programmed cell death)

Bottom line:

Inhibiting EZH2 reverses abnormal methylation → restores tumor suppressor gene expression → slows or kills cancer cells.