Paper 1 Section B- crime

1/170

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

171 Terms

Criminal law

Actus Reus + Mens Rea = offence

Actus Reus: conduct and consequence crimes; voluntary acts and omissions; involuntariness; causation

Mens Rea: fault, intention and subjective recklessness, negligence and strict liability, transferred malice; coincidence of Actus Reus and Mens Rea

Actus Reus

Actus Reus= “guilty act”. It is the conduct element (doing part) of the crime, which usually involves a positive voluntary act. Can also be an omission or state of affairs

AR element must be proved first. Only create criminal liability if it is accompanied by Mens Rea

Statutory crimes

these definitions are found in the words of the act of parliament

Common law offences

found in the decisions of the court

Conduct must be voluntary

As a general rule, if the D is to be found guilty of a crime, his/her behaviour in committing the Actus Reus must be voluntary. This is because if D did not will his act, we can hardly say he did it

Behaviour will usually only be considered involuntary where the accused was not in control of his/her own body

OR when there is extremely strong pressure from someone else e.g. a threat

Crimes

Conduct crimes (doing)- what matters is what D does e.g. drink-driving or perjury

Consequence crimes (result)- AR must result in consequence e.g. Assault occasioning actual bodily harm

State of affair crimes (circumstance)- what matters is being there in the prohibited circumstances e.g. being in possession of a controlled drug

Omissions

Omission= a failure to act (this can be the AR)

The general rule in criminal law is that a person is not liable for an omission (a failure to act) unless under a duty to act

Duties created by parliament= stautory duties

Duties created by judges= common law duties

Statutory duties

Examples:

Failing to wear a seatbelt or give a breath specimen under the road traffic Act 1988

Failing to muzzle a dangerous dog in public under the dangerous dogs Act 1991

Neglecting a child, domestic violence, crime and victims Act 2004

Common law duties

Contractual duties: Arise through contracts of employment. Pitwood (1902), a railway crossing keeper had a duty to close the gates, this omission formed the AR of manslaughter

Official position: usually related to public offence. Dytham (1979), police officer stood by while V was beaten up. D was guilty for failing to perform his duty while in a public position

Special relationship: Gibbins and Proctor (1918)- father starved his 7 yr old daughter to death. He had a duty to feed her and the omission formed the AR of murder

Duty undertaken voluntarily: Based on reliance. Stone and Dobinson (1977), where D took in an elderly relative and failed to look after her. D was liable for her death

Creating a dangerous situation: Miller (1983), D failed to take reasonable steps to deal with the fire he had started. He had created a dangerous situation and owed a duty to call the fire brigade. He was also therefore liable when he failed to do so.

Causation

Causation is an essential element to establish the Actus Reus in consequence crimes. There needs to be evidence to show that the defendant caused the consequence.

Factual causation + legal causation= AR consequence of the crime

“But for” test

it must be proved that the unlawful consequence would not have happened “but for” D’s actions

Minimal cause

D’s conduct must be more than minimal cause of the consequence and there must be NO intervening acts which broke the chain

Factual causation

It must be proved that the unlawful consequence would not have happened “but for” D’s conduct

Factual causation is not enough for criminal liability by itself, must have legal causation

White (1910): D was acquitted because although he tried to poison his mother, she actually died because of a heart attack- so he wasn’t a factual cause. Guilty of attempted murder.

Pagett (1983): D was the factual cause of death when he used his girlfriend as a shield and fired at police. She wouldn’t have died “but for” his actions. D was liable for mansalughter,

Legal causation

May be more than one act contributing to the consequence

Some of these acts may be made by people other than D

KEY RULE: D’s conduct does not need to be the only cause of the consequence. D’s contribution must be more than minimal

Key case: Kimsey (1996)

Thin skull rule

If the victim had a special characteristic or vulnerability which makes an injury more serious, then D is liable for the more serious injury even if D was unaware of that possibility

“thin skull rule”- means that D must take V as he or she finds him

The rule applies to mental conditions and beliefs, as well as physical characteristics

KEY CASE: Blaue (1975)

Intervening Acts

Intervening acts may break the chain of causation to break and prevent D from being liable for the ultimate result, even if D’s conduct was factual and more than minimal cause

Chain of causation can be broken by:

An unforeseeable act of nature e.g. being struck by lightning

The unforeseeable act of a 3rd party e.g. doctors

Victims own subsequent conduct

Victims own conduct

If D causes victim to act in a foreseeable way, then V’s own act will not break the chain of causation

The key question is whether V’s conduct was within a range of responses that could be regarded as reasonable in the circumstances

KEY CASES: Roberts (1971) and Williams (1992)

Medical treatment

Medical treatment, even if negligent is unlikely to break the chain of causation unless it is independent of D’s conduct and “in itself so potent causing death” that D’s act are insignificant

Medical treatment will only break the chain of causation if it is exceptionally bad or makes D’s actions insignificant

KEY CASE: Jordan (1956)

Mens Rea

Mens Rea= the mental element or “guilty mind”

A person may have MR without any feeling of guilt at all, they may be acting with a perfectly clear conscience

The Mens Rea of a criminal offence is looking at D’s state of mind at the time of committing the offence

Every offence has its own MR, depends on the offence what state of mind is required

Intention

Intention= highest form of MR. Some offences like murder need intention

Motive and intention are not the same thing

Intention is judged subjectively e.g. based on what D in those circumstances thought, not what the reasonable person would think

TWO TYPES: direct intent and indirect intent

Direct intent

Direct intent= where the result is D’s aim or purpose

Defined in Mohan (1975) as a “decision to bring about the prohibited consequence” no matter whether D desired the consequence or not

KEY CASE: Mohan (1975)- D had driven his car straight at a police officer with the aim of injuring him

Indirect intent

Indirect intent= where the result isn’t D’s aim, yet he/she realises it is “virtually certain” to occur as a result of their actions

Woolin (1998):

A jury is not entitled to find indirect intention unless they feel sure that death or serious bodily harm was-

a virtual certainty as a result of D’s actions AND

that D’s appreciated that it was

Recklessness

recklessness= a lower level of Mr than intention, it only needs to be considered when D does not have intention

It must be shown that D is aware of a risk of the consequence happening, but deliberately goes ahead and takes it anyway

Recklessness is subjective (based on what was in D’s mind, if D didn’t appreciate the risk, he cannot be reckless)

KEY CASE: Cunningham (1957)

Negligence

Negligence= a person is negligent if he/she fails to meet the standard of the reasonable person. It is objective because D does not have to realise this

KEY CASE: Adomako (1994)

Transferred malice

Transferred malice= D can be guilty if he/she intended to commit a crime against A but actually committed the same crime against offence B

D’s Mr cannot be transferred if the eventual crime committed is different to the one intended

KEY CASE: Pembilton (1874)

Strict liability

Strict liability offences do not require mens rea

These offences are the exception to the general rule that both AR and MR is required for criminal liability

Most concern road traffic offences or breaches of health and safety legislation

Often called “no fault” offences

D can be convicted if his voluntary act caused a prohibited consequence even though D is blameless

CASE EXAMPLE: Callow v Tillstone (1900)

D will still be guilty even if he/she has taken reasonable precautions to avoid committing offence

CASE EXAMPLE: Cundy v Le Cocq

Which offences are strict liability?

Usually an act of parliament will make it clear if mens rea is needed e.g. use words like intention or reckless

If an act makes it clear that mens rea is not required, the offence will be one of strict liability e.g. driving without a license

If there is no act of parliament or the words of the statute do not make it clear, the judges presume that mens rea is required

Coincidence

Both AR and MR must be present at the same time

There are situations where this requirement of “coincidence” has caused problems

AR and MR may not always coincide

Judges have found a way around this- continuing acts and series of connected acts

Continuing act

Where the initial AR is established. Provided at some point while the AR is still going on, D forms the MR- then the AR and MR are said to coincide

KEY CASE: Fagan (1986)

Series of connected acts

This is where there is an initial MR. D then performs a series of acts which connected together form the AR. The AR and the MR are still said to coincide

KEY CASE: Thabo Meli (1954)

Fatal offences

Fatal offences= involve the death of another human being and are considered the most serious crime. They can range from an intentional killing to death being unintended consequence, caused by carelessness or another unlawful act

TWO MAJOR OFFENCES: Murder and manslaughter

Murder- most serious offence against another person

Manslaughter- ranged between intentional killing and accidental death

Voluntary manslaughter

D intended to kill or cause GBH but lost control or had a diminished responsibility (mental illness)

Involuntary manslaughter

D did not intend to kill or cause GBH but intended a criminal act or was grossly negligent

Murder

Murder is a common law offence with a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment

Lord Coke defined it in the 17th century as: “the unlawful killing of any reasomable creature in being under the king’s peace with malice aforethought, expressed or implied”

ACTUS REUS- unlawful killing of a human being under the king’s peace (within any country of the realm)

MENS REA- intention to either kill or intention to cause serious injury

Actus reus of murder

Unlawful killing: can be by an act or omission. must have legal and factual causation (Gibbins and proctor 1918)

Human being: this excludes a foetus or a person who is brain dead (A-G’s reference 1994)

King’s peace: This excludes killing an enemy in battle when the country is at war. (Blackman 2017)

Within any country of the realm: this includes killing a person anywhere in the UK

Mens rea of murder

Malice aforethought: expressed malice means an intention to kill, implied malice means intention to cause serious harm (Vickers 1957)

Intention: direct intent means it is the defendants aim, purpose or objective (Mohan 1976), indirect intent means the defendant realised the consequence and was virtually certain (Woolin 1998)

Voluntary Manslaughter

Murder is reduced to manslaughter due to one of two special defences: loss of control or diminished responsibility

Reflects the fact that in some way the defendant is less blameworthy

It means a judge has discretion in the sentence he/she imposes, thereby avoiding the mandatory life sentence for murder

Loss of control

Loss of control covers situations where D causes death but at the time of the killing lost self control and reacted as a “normal person” might have D’s situation

Law is set out in the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, which replaced the former defence of provocation

Loss of control + Qualifying trigger + Normal person test

Coroners and Justice Act 2009

S.54 Coroners and Justice Act 2009

(1) A person who kills may be convicted of manslaughter rather than murder where there exists…

(a)A loss of self control

(b) The loss of control had a “qualifying trigger”

(c ) A person of D’s sex and age, with a normal degree of tolerance and self restraint and in the circumstances of D, might have reacted the same way or similar to D

Loss of self control

This means a loss of ability to act in accordance with considered judgement or a loss of normal powers of reasoning

Loss of control is judged subjectively: Did D actually loose control at the time of the act or omission which caused V’s death?

The loss of control need not be sudden: S.54 (2), it may follow the cumulative impact of earlier events

S.54 (4) It excludes situations where D has acted in a “considered desire for revenge”

A time delay (whether the loss of control was continuing or D had time to cool off and the crime was an act of revenge) may indicate no current loss of self-control

KEY CASE: Ahluwalia (1992)

Qualifying trigger

The qualifying triggers are set out in S.55 of the Act. Either trigger is sufficient or it may be a combination of both that caused D to lose control and kill

The “fear” trigger: D fears serious violence from V against D or another identified person. This is subjective. S.53 (3).

KEY CASE: Ward (2012)

The “anger” trigger: things said or done (or both) which are of extremely grave character and caused D to have a justifiable sense of being seriously wronged. This is decided objectively.

KEY CASE: Zebedee (2012) and Hatter (2013)

Limitations on qualifying triggers

Sexual infidelity- the fact that a thing done or said constituted sexual infidelity is to be disregarded

KEY CASE: Clinton (2012)

Incitement- A person may not raise a qualifying trigger if they incited the thing done or said the violence

KEY CASE: Dawes (2013)

Revenge- S.55 (4) excludes situations where D has acted “in a considered desire for revenge”

Normal person test

S.54 1( c ), a person of the defendant sex and age, with a normal degree of tolerance and self restraint and in the circumstances of the D, might have reacted in a same or similar way

Degree of tolerance and self restraint

Circumstances of the defendant

Might have reacted in the same/similar way to D

Degree of tolerance and self restraint

Question for the jury to decide

It is an objective test as D is expected to show a normal degree of self control

Apart from the sex and age of D, the jury cannot consider any circumstances of D that might have made him/her have less self control

Circumstances of the defendant

Jury must look at all of D’s circumstances apart from those whose only relevance is to bear D’s general capacity for tolerance and self restraint

Short temper, racism and homophobia are not circumstances as they would only serve to lower D’s capacity to lower D’s capacity for tolerance

History of sexual abuse or mental illness may be a relevant circumstance

Voluntary intoxication is not a circumstance. However, if D had an alcohol or drug problem and was mercilessly taunted about (which could be constituted as a qualifying trigger) then this would a circumstance

KEY CASE: Rejmanski (2017)

KEY CASE: Asmelash (2013)

Might have reacted in the same or similar way to D

The defence will fail if the jury considers that the “normal person” might have lost control but not have reacted in the same way

KEY CASE: Christian (2018)

Diminished responsibility

Defined by S.2 Homicide Act 1957 and amended by S.52 Coroners and justice Act 2009

A person may be convicted of manslaughter rather than murder if he/she was suffering from an abnormality of mental functioning which:

(a) arose from a recognised medical condition

(b) Substantially impaired D’s ability to:

understand the nature of their conduct;

Foram a rational judgement;

Or exercise self control

(c ) provides and explanation for D’s actions and omissions in killing

KEY ELEMENTS OF DR

abnormality of mental functioning

recognised medial condition

substantial impairment

explains the killing

Abnormality of mental functioning

“A state of mind so different from that of the ordinary human being that the reasonable man would term it abnormal” (Bryne 1960)

AMF must arise from a recognised medial condition

Recognised medical condition

This includes psychological and psychical conditions according to medial classification:

Psychotic condition (Golds 2016)

Post natal depression (Boots 2012)

Mental disorder (Brennan 2014)

Alcohol dependency syndrome (Wood 2008)

Depressive illness (Dietschmann 2003)

Asperger’s syndrome (Jama 2004)

Battered spouses syndrome (Hobson 1997)

Sever learning difficulties may also be included but not “normal immaturity” on the part of the child should not qualify. However, if D is over 18 and has a lower mental age, this would be considered a recognised medical condition

Substantial impairment

The abnormality of mental functioning must substantially impair D’s ability to do one of 3 things:

Understand the nature of his conduct S.52 1A ( a )

To form a rational judgement S.52 1A ( b )

To exercise self control S.52 1A ( c )

“Substantial” impairment is a matter of degree for the jury in each case: Golds (2012), the impairment must be beyond merely trivial, but D’s mental functioning need not be totally impaired

Explanation for D’s conduct

D has to prove that the abnormality of mental functioning provided an explanation for his acts or omissions S.52 ( 1 ) ( c )

There has to be casual connection between the AMF and the killing

The AMF need not be the only factor which caused D to do or be involved in the killing, however, it must be a significant factor (this is particularity important where D is intoxicated at the time of the killing)

Burden of proof is on the defence, D need only prove it on the balance of probabilities

Diminished responsibility and intoxication

D was drunk at the time of the killing and tried to claim DR:

Intoxication alone cannot support a defence of DR as the temporary effect of drink or drugs on the brain is not a recognised medical condition

Dowds (2012)

Voluntary intoxication cannot be used as the basis of a defence of DR

Diminished responsibility and intoxication

D is intoxicated due to addiction or dependency:

Alcohol dependency syndrome (ADS) is a recognised medical condition which means that a person cannot control their drinking. Does not automatically mean D can rely on DR, but it may be the cause of abnormality of mental functioning

Wood (2008)

If alcohol has caused damage to the brain or become a disease, then DR may be relevant. If D has ADS, then not every drink consumed has to be involuntary.

The jury would have to consider all the evidence on he extent of D’s dependency and his or her ability to control it

Diminished responsibility and intoxication

D was intoxicated and has pre-exsisting AMF:

If D is already suffering from AMF and has taken drugs or alcohol, the defence will be available if D can satisfy the jury that, despite the drink, his abnormality was a substantial impairment which explained the killing

Dietschmann (2003)

Involuntary manslaughter

An unlawful killing without the intention to kill or cause GBH. It is a common law offence with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment

Two main ways of committing involuntary manslaughter: unlawful act manslaughter and gross negligence manslaughter

Unlawful act manslaughter

Where D causes the death of V through an unlawful and dangerous act without malice aforethought for murder and with only the mens read for the unlawful act

KEY CASE: Newbury and Jones (1976)

Key elements:

D must do an unlawful act (a crime)

That act must be a dangerous on an objective test

That act must cause the death

D must have mens rea for the unlawful act

Unlawful act

There must be an act- an omission is insufficient (e.g. Lowe 1973). The “unlawful act” must be a criminal offence

KEY CASE: Lamb (1967)

Usually the unlawful act is a non-fatal offence but it can be any unlawful act against a person or property provided it is likely to cause injury e.g. criminal damage or burglary

Dangerous

Unlawful act must be “dangerous” on an objective test i.e. such as all sober and reasonable people would inevitably recognise must subject the other person to, at least, the risk of some harm, albeit not serious harm (Church 1965)

It does not matter that D did not realise that there was a risk of harm to others. Nor does the unlawful act need to be directed at V. (Good fellow 1986)

There must be a risk of some psychical harm, rather than emotional (Dawson 1985 and Watson 1989)

D’s knowledge of the circumstance can be attributed to the sober and reasonable person (Bistow, Dunn and Delay 2013)

Causation

The unlawful act must cause death in fact and law

Factual causation: “but for” test

Legal causation: more than minimal cause of the death and no intervening events to break the chain of causation

KEY CASE: Kennedy (2007)

Mens rea for unlawful act

D only requires the mens rea for the initial act; there is no need to prove that d realises the act is dangerous or unlawful, or even that D foresees a risk of harm

KEY CASE: Newbury and Jones (1976)

Gross negligence manslaughter

D causes V’s death by breaching a duty of care towards V in a grossly negligent way. D’s acts or omission must fall so far below the required standard of care that it goes beyond mere compensation and amounts to a crime i.e. “gross” negligence

KEY ELEMENTS:

The existence of a duty of cared owed by D to V

A breach of that duty of care which causes death

Gross negligence which jury considers to be so bad to be criminal

Duty of care

There must be a duty of care owed by the D to V. This is a question of law and for the trial judge to decide

KEY CASE: Adomkao (1994)- A duty of care is owed to anyone if it is reasonably foreseeable that they ay be harmed by D’s negligent acts or omissions

KEY CASE: Evans (2009)- A duty of care can include situations that give rise to liability or omissions

KEY CASE: Wacker (2002)- In the civil law of negligence no duty of care is owed to someone involved in unlawful activity THIS DOES NOT APPLY IN CRIMINAL CASES

Breach of duty which causes death

If D falls below the standard of the reasonable person performing the duty in question, he/she will be in breach of the duty

Causation must be factual (“but for” test) and legal (more than minimal cause and no break in the chain of causation)

If the breach is caused by an omission, the prosecution would have to prove that V would have survived if D had fulfilled their duty to act

KEY CASE: Broughton (2010)

Risk of death

D’s conduct must involve a foreseeable risk of death at the time of the breach

Just because the breach of duty was a cause of death, it does not meant there was a foreseeable risk of death at the time of the breach

Test is objective

Would a reasonable person in the D’s position reasonably foresee a serious and obvious risk of death of the person to whom the defendant owed a duty?

Gross negligence

The negligence on the part of the defendant must be “so gross” in the eyes of the jury as to be criminal

Bateman (1952): “gross” was defined as negligence which went beyond mere matter of civil compensation between subjects and showed such disregard for the lie and safety of others as to amount to a crime against the state and deserving punishment

Sellu (2016): task of the jury is to identify the line that separates serious injury or even serious mistakes from conduct which is truly exceptionally bad and such a departure from that standard that it consequently amounted to being criminal

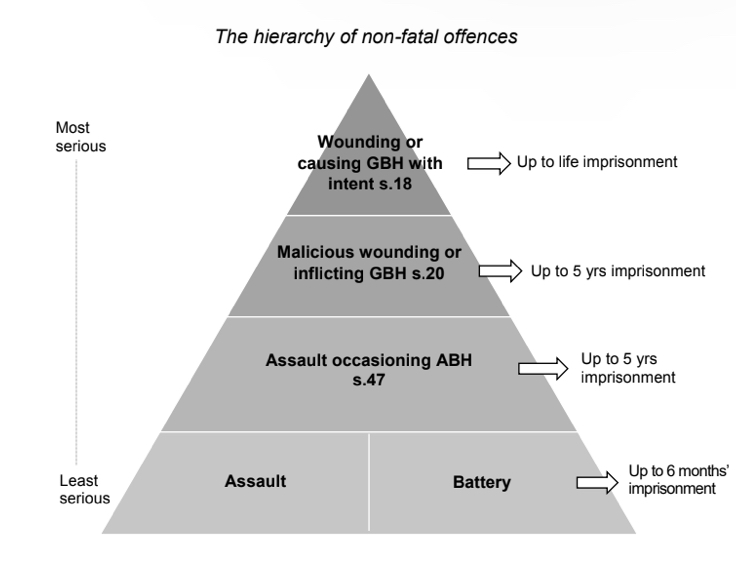

Non-fatal offences

There are 5 main fatal offences which are termed “non fatal” as they do not kill V

Assault and battery are common law offences, they are not defined by any act but the Criminal Justice Act (1988) states that the maximum sentenced for each and established that they are summary offences. Refereed to as “common assault”

Remaining three offences are well defined in the offences against the person Act (1861.

S.47 actual bodily harm

S.20 wounding or inflicting grievous bodily harm

S.18 wounding or causing grievous bodily harm with intent

Hierarchy of non fatal offences

Actus Reus of Assault

(Assault required no touching or injury but the victim must be in fear of force)

Actus Reus= actions or words which causes V to apprehend immediate unlawful force

Actions or words:

In Smith v Woking Police (1983) the act was looking at a woman in her night clothes through a window. Words alone could be enough and even silent phone class as in Ireland (1999)

Words can also prevent an assault by making it clear that violence is not going to be used e.g. Tuberville v Savage (1669)

Which causes D to apprehend immediate unlawful force:

Apprehend means V expects violence to take place. It is the effect on V that is important with assault

The threat must be of “immediate” violence. A threat to inflict harm in the future is not an assault. However, this requirement has been widely interrupted

Mens rea of assault

Intentionally causing V to apprehend immediate unlawful force OR Recklessly causing V to apprehend immediate unlawful force

Logdon (1976)- D pointed an imitation gun at V in jest. V did not realise it was a replica and was terrified. Although D did not intent to carry out the threat, he was reckless as to whether V would apprehend such violence

Actus Reus of Battery

(Battery requires touching but no injury)

Actus reus= applying unlawful force to another person

“Force” can be misleading. In Collins v Wilcock (1984), it was decided that “any touching of another person, however slight, may amount to battery”

Touching someone else’s clothes while they are wearing them is equivalent to touching the person e.g. Thomas (1985)

Battery can also be committed by an indirect act e.g. DPP V K (1990)

An omission can form a battery e.g. Santana Bermudez 2003

Mens Rea of battery

Intentionally applying unlawful force to V OR Recklessly applying unlawful force to V

The MR of battery was defined in Venna (1976), where D was judged t have committed battery recklessly when struggling with a police officer who was trying to arrest him

Indirect assault

When the D does not make an overt act but instead causes the victim to reasonably fear for their safety

Direct assault

Can be committed two ways. First by using force or intimidation, second by using force or by seriously resisting any persons in authority

Indirect battery

Person applying force does not have to contact with the victim e.g. when an object is thrown at the victim. The act must be voluntary, meaning the person applying the force must be in control of their actions

Direct battery

The defendant physically applies the force to the victims body e.g. D punching the victim

Assault occasioning ABH

Assault or battery causing some harm

Requires injury which can be psychiatric

Triable either way offences

Up to 5 years imprisonment

S.47 offences against the person Act 1861

Actus Reus of assault occasioning ABH

Assault or Battery which causes ABH

There must be the AR of either Assault or Battery

Miller (1954) ABH was defined as “any hurt or injury calculated to interfere with health or comfort” provided its more than trivial. Harm is not limited to injury to the skin, flesh and bones

DPP v Smith (2006) it was held that cutting off V’s ponytail amounted to ABH

T v DPP (2003), momentary loss of consciousness amounted to ABH

ABH can also amount to psychiatric injury, but does not cover mere emotions such as fear, distress or panic (Ireland 1999)

Mens rea of Assault occasioning ABH

Intentionally or recklessly causing V to apprehend immediate unlawful force (MR of assault)

OR

Intentionally or recklessly applying unlawful force to V (MR of battery)

There is no need to intend to be reckless as to whether ABH is caused

Maliciously wounding or inflicting GBH

5 years imprisonment

Triable either way offence

S.20 offences agains the Person Act 1861

Actus reus of maliciously wounding or inflicting GBH

Wounding or inflicting grievous bodily harm

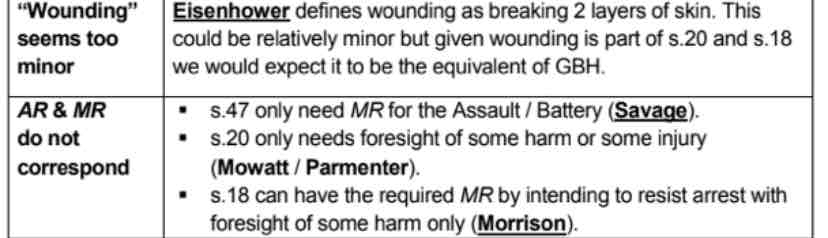

Wounding means breaking the skin, not internal bleeding as in Eisenhower (1983) in which a blood vessel was burst.

Any cut could be treated as a wound, provided it breaks two layers of the skin.

abrasion, bruise or burn would not amount to a wound because the skin is not broken

“Grievous Bodily Harm” (GBH) was defined in DPP v Smith (1961) as serious harm.

includes things like broken limbs, dislocations, permanent disability

Bollom (2004) it was said the severity of injuries should be assessed according to V’s age and health

Brown & Stratton (1997), several minor injuries amounted to GBH.

More recently the definition of GBH has been extended to cover serious psychiatric injury (Burstow 1997) and even biological disease (Dica 2004).

Mens rea of maliciously wounding or inflicting GBH

Intentionally causing some harm

OR

Recklessly causing some harm

It is not necessary to intend serious harm or even realise there is a risk of causing serious harm – only SOME harm In Parmenter (1991), D threw his baby into the air and caught him. D was not guilty of s.20 because he did not realise there was a risk of any injury.

Wounding or causing grievous bodily harm with intent

Most serious non fatal offence, because it has ‘intent’

Indictable offence

Max penalty is life imprisonment

S.18 Offences agains the Person Act 1861

Actus reus of wounding or causing grievous bodily harm with intent

Wounding or causes grievous bodily harm

“wounding” means breaking two layers of the skin (Eisenhower) and GBH means “serious harm” (DPP v Smith)

Judges have decided that “causing” GBH (s.18) and “inflicting” GBH (s.20) amount to the same thing.

Mens rea of wounding or causing grievous bodily harm with intent

Intention to cause GBH

OR

Intention to resist arrest (with foresight of some harm)

MR of s.18 usually occurs where D intends to cause serious injury.

Belfon (1976) confirms that being reckless as to causing serious injury is not enough

An intention to wound is not

enough (Taylor 2009)

Intention can be direct (D’s aim or purpose is to cause serious injury) or indirect (D realises serious injury is a virtual certainty).

Morrison (1989) provides an illustration of the alternative MR of s.18. In this case, D dived through a window to escape arrest, dragging the police officer through the broken glass. D was convicted of s.18. It was enough that D intended to resist arrest and was reckless as to whether this caused V some injury.

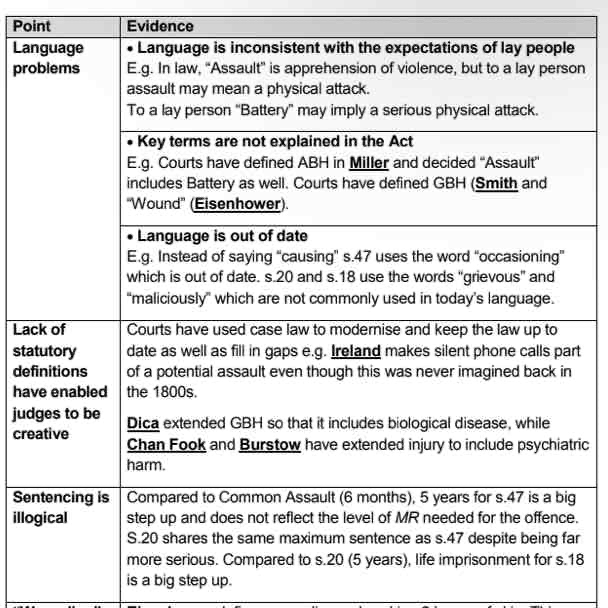

Evaluation: assault and battery

S.39 Criminal Justice Act 1988 does not make it clear that Assault and Battery are two distinct offences and then creates confusion by referring to both as “Common Assault”.

The terms “Assault” and “Battery” are not defined – we rely on Common Law for their meaning.

Judges’ decisions seem at odds with lay people’s assumptions. For example, most people would think “assault” meant a physical attack and not just a threat; while most people would think “battery” meant a severe beating and not just any sort of touching.

There should be a clear statutory definition for lawyers and lay people.

Evaluation: S.47 assault occasioning ABH

“Assault” is misleading as battery can also (and usually does) form the basis of a s.47 offence.

“Occasioning” is an old-fashioned word for “causing”.

“Actual bodily harm” is not defined in the OAP Act 1861 and the statute leaves the MR of s.47 unclear. Both have had to be defined by Judges through case law.

The AR and MR of s.47 do not correspond, i.e. there is no MR required in relation to the injury. This means that D is guilty for the outcome of his or her actions, rather than what they intend or foresee. Savage (1991) provides a useful illustration of this point.

This is unfair because it goes against the principle of criminal law that people should only be responsible for what they foresee.

However, constructive intent forces people to take responsibility for their conduct, ensuring that victims get justice.

The sentence jumps from 5 years even though D may not have intended or foreseen a risk of the injury caused.

Evaluation: S.20 maliciously wounding or inflicting GBH

The phrase “Grievous Bodily Harm” is an old fashioned term and the courts rely on case law for a definition.

The inclusion of “wound” theoretically includes minor injuries. Serious wounds could simply be treated as GBH.

S.20 just says “maliciously” without explaining what this means. “Maliciously” suggests evil intent but in common law it means intention or recklessness as to some harm.

There used to be some confusion over whether the verb “inflict” required application of physical force. It just means “cause”.

The AR and MR do not correspond – D need not foresee serious injury, just some harm. “Constructive intent” means D is guilty for the outcome of their actions, rather than what they intend or foresee.

The sentence is the same as s.47 even though D has caused a much more severe injury.

S.18 maliciously wounding or causing GBH with intent

There is some overlap with the criticisms of s.20 since they both have the same AR.

The verb “cause” (GBH) is used in s.18, while s.20 uses the verb “inflict”. There used to be debate over whether they meant different things or apply in different ways.

In s.18, D must intend GBH, but there is also the word “maliciously”, which adds nothing in most cases (unless D is intending to resist arrest).

Ds who wound or cause GBH while trying to resist arrest are charged with the same crime as those who set out to cause serious injury. Where D is trying to resist arrest, he or she need only foresee the risk of causing some harm (Morrison 1989). Arguably, the two MR are unbalanced.

The maximum sentence jumps to life even though the injury is the same as in s.20. This can be justified if D intended GBH but perhaps not if he or she only intended to resist arrest.

Idea for reform: non fatal offences

Update confusing language

“Assault” and “Battery” could be re-named as “Threatened Assault” and “Physical Assault” respectively.

The phrases “Actual Bodily Harm” and “Grievous Bodily Harm” could be dropped in favour of “injury” and “serious injury”.

The verb “causes” should be used consistently across all offences.

Provide a clearer hierarchy of offences

“Threatened Assault” and “Physical Assault” should still have a maximum sentence of 6 months, as is the case under the current Common Assault.

The Law Commission propose splitting s.47 into two new offences: aggravated assault (max sentence 1 year) and intentionally or recklessly causing injury (max sentence 5 years).

Recklessly causing serious injury should replace s.20 and have a maximum sentence of 7 years. Intentionally causing serious injury should remain as s.18 with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

Ensure offences conform to the “correspondence principle”

Each offence should provide a clear and accurate label for the conduct in question.

So the “new s.47” should require D to intend or foresee the risk of injury– a fairer way of assessing D’s blame.

Similarly, the “new s.20” should require D to be reckless as to serious injury. Foresight of some harm would no longer be enough.

The alternative MR of resisting arrest under s.18 should be removed.

2015 law commission proposals

2015 law commission proposals 2

Property offences

Theft under s.1 Theft Act 1968

Robbery under s.8 Theft Act 1968

Burglary under s.9(1)(a) and s.9(1)(b) Theft Act 1968

Theft

Section 1 of the Theft Act 1968

Maximum sentence of 7 yrs imprisonment

A person is guilty of theft if they dishonestly appropriate property belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it

Actus reus of theft

Appropriation (s.3)

Property (s.4)

Belonging to another (s.5)

Mens rea of theft

Dishonesty (s.2)

Intention to permanently deprive (s.6)

Appropriation

Includes physical taking, but is defined in section 3 as: “Any assumption by a person of the rights of an owner amounts to an appropriation”

Rights of ownership compromise a “bundle” of rights including not only the right to possess, but to sell, price, use, lend or destroy property.

KEY CASE: Pitham and Hehl (1997)

KEY CASE: Morris (1983)- D changed the price of an item in a supermarket to that of

a lower priced item, but did not get through the checkout. Assuming any one right of the owner is enough. Theft is complete at that moment if accompanied by dishonesty and intent to permanently deprive. There was no need for D to leave the shop.

Appropriation includes situations where “D has come by the property (innocently or not) without stealing it, and later assumes the right to it by keeping or dealing with it as owner” – s.3(1).

An appropriation can also take place even with the consent of the owner: Lawrence (1972) and Gomez (1993)

Hinks (2001): D befriended a rich man of low intelligence. She convinced him to withdraw £300 a day and put it in her account. The £60,000 that she had received from the victim was an appropriation regardless of it being a gift

All the elements of theft need to be established. Just because someone has appropriated something does not automatically mean that they are guilty of theft.

Property

S.4: “Property includes money and all other property real or personal including things in action and other intangible property.”

Money- coins and notes

Personal- possessions (including dead bodies, hair, urines, body parts)

Real- land or buildings

Things in action- rights enforceable by court action e.g. bank transfer. Things that are intangible that become tangible

Other intangible property- things you cant touch

Things which can’t be stole

Confidential information: Oxford v Moss (1979), D was a student who took an exam paper, read the questions and then returned it. D could not be charged with theft of the information on the paper. If he had kept the exam paper this would have been theft of the paper itself.

Fungus, flowers, fruit and foliage S.4(3): Provided they are growing wild and are not picked for reward or sale.

Wild creatures S.4(4): provided they are not tamed or in captivity

Belonging to another

S.5: “Property shall be regarded as belonging to any person having possession or control over it, or having any proprietary right or interest.”

Possession or control:

Usually the owner has possession and control, but the prosecution does not

have to prove who the owner is (Turner 1971)

It is possible to be in possession or control without knowing it (Woodman 1974)