Cardio PES

1/70

Earn XP

Description and Tags

incomplete

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

71 Terms

Diaphoresis

profuse sweating

(unrelated to temperature or activity)

may indicate MI or shock

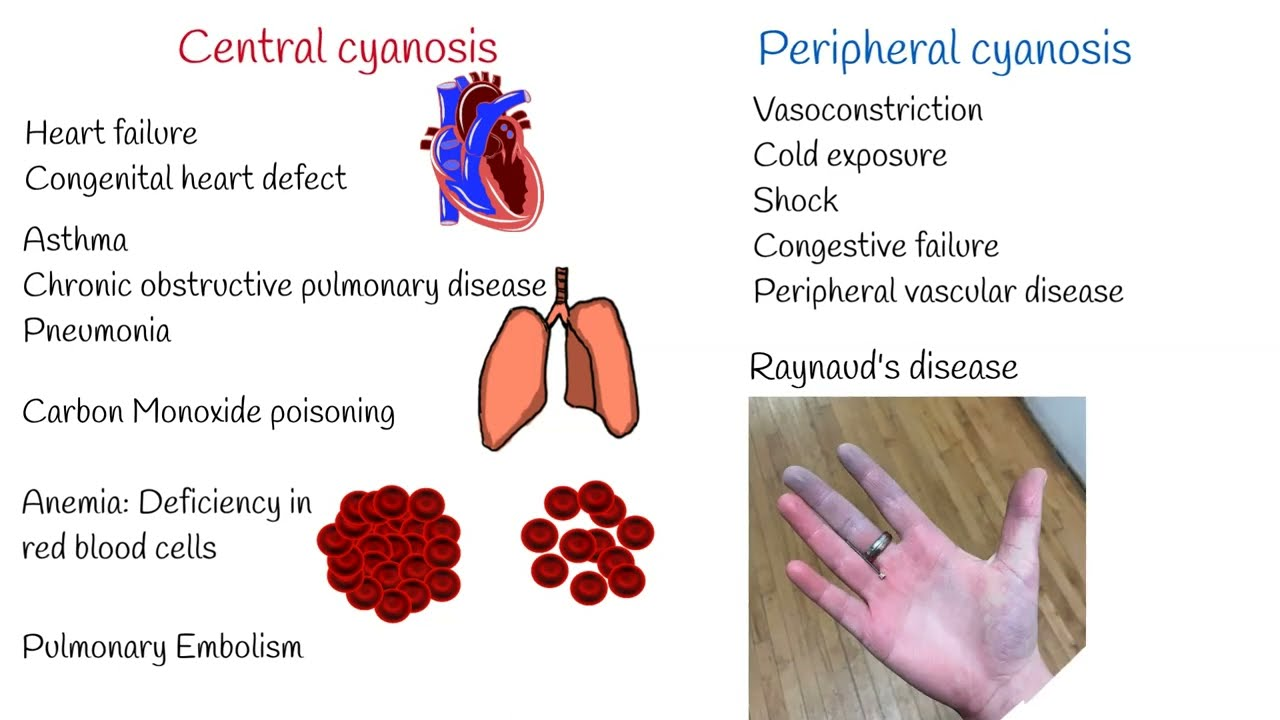

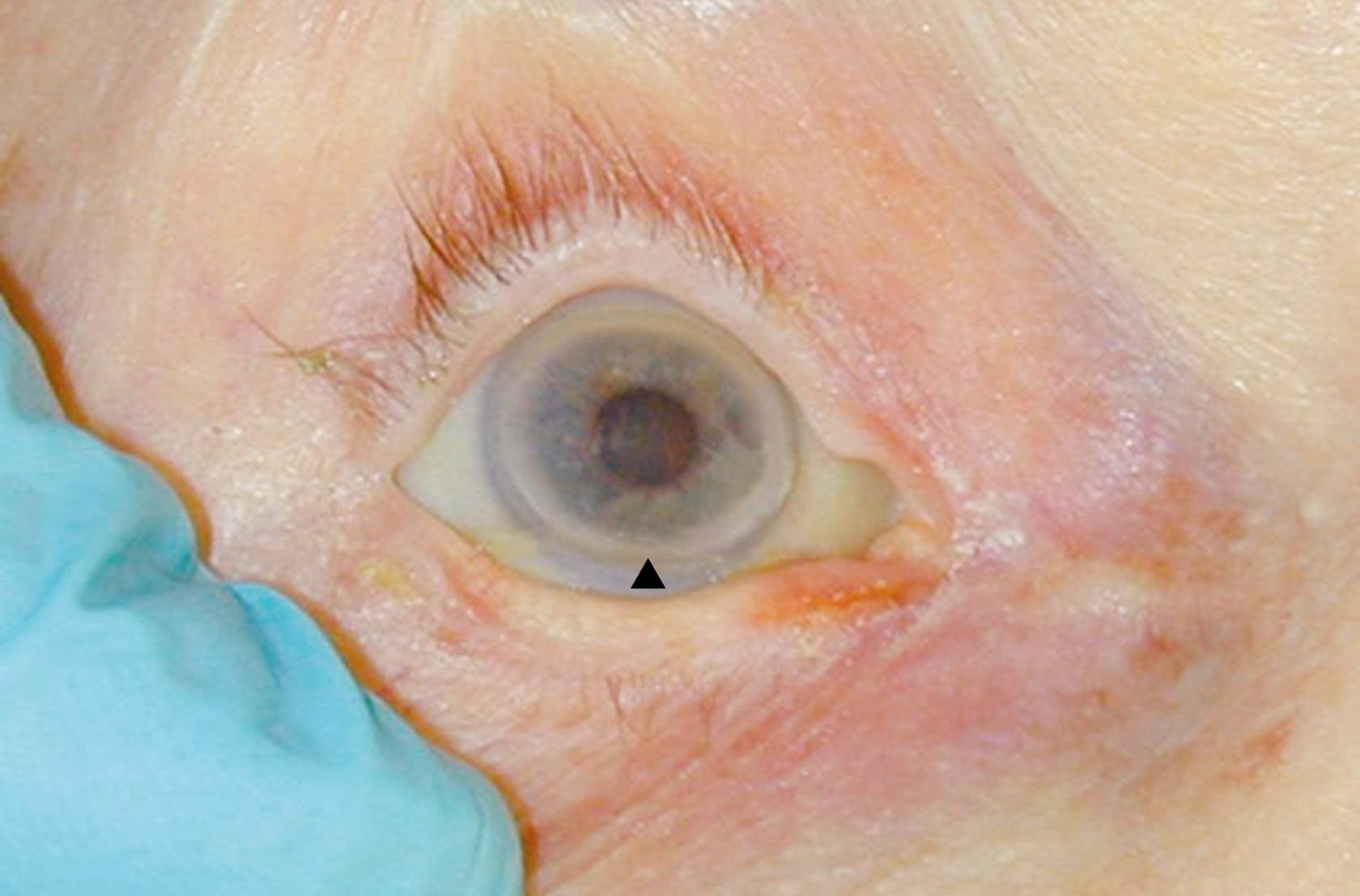

Cyanosis signs

either peripheral or central:

Central cyanosis:

bluish lips, tongue (especially the underside), and oral mucous membranes (use a light)

causes:

cyanotic congenital heart disease with right-to-left shunt

respiratory disease e.g. COPD and pulmonary embolism

high altitude + resultant decreased inspired oxygen concentration

polycythaemia (increased hematocrit and/or hemoglobin concentration)

haemoglobin abnormalities

Peripheral cyanosis

bluish discoloration of the hands, nail beds and feet

causes:

All causes of central cyanosis cause peripheral cyanosis

exposure to the cold

reduced cardiac output

arterial or venous obstruction

can reflect poor oxygenation, reduced perfusion, or anaemia

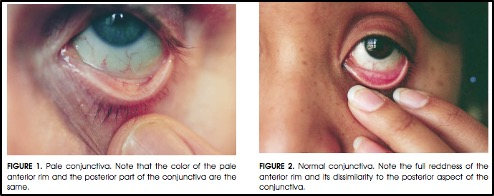

Pallor

pale conjunctiva, nail beds, and palmar creases

can reflect poor oxygenation, reduced perfusion, or anaemia

male risk factor

Earlier Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) risk

obesity risk factor

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) risk

ethnic background risk factor

South Asian, Indigenous Australians, Pacific Islanders have higher Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) risk

GTN spray

Common nitrate used in angina

Suggests known ischaemic heart disease

down syndrome cardiac relation

50% of patients will have a cardiac defect

most often an atrioventricular septal defect

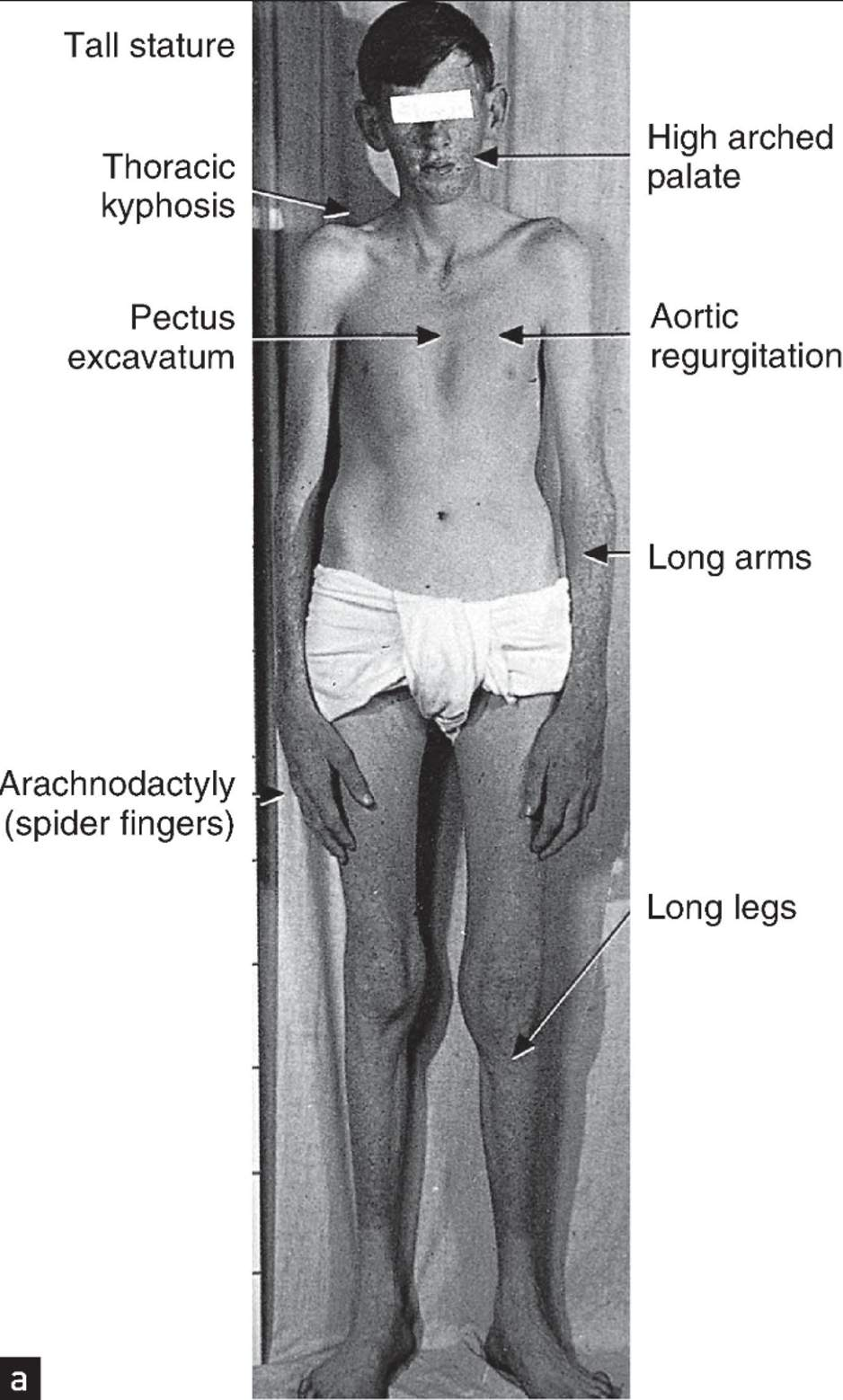

marfan syndrome cardiac relation

Check for:

High arched palate

tall stature

long limbs

long fingers

Associated with:

aortic dilatation with risk of dissection

mitral valve prolapse

aortic regurgitation

Turner syndrome cardiac relation

50% of patients will have a major cardiac defect e.g.

coarctation of the aorta

bicuspid aortic valve

Turner Syndrome signs

short stature

webbing of the neck

stocky build

shield-like chest

lack of breast development and cubitus valgus in female patients

hydration status

fluid overload:

can be a sign of cardiac failure

e.g. bilateral ankle swelling due to peripheral oedema

could also be renal failure or excessive IV drug use

dehydration:

sunken eyeballs

a ‘moribund’ appearance (i.e., look very unwell)

altered consciousness

heart rate

normal resting: 60-100 beats per minute

bradycardia: <60

tachycardia: >100

radio-radial delay

inequality in timing or volume of the pulse

can occur with:

coarctation of the aorta

aortic dissection

subclavian artery stenosis

radio-femoral delay

suggestive of coarctation of the aorta

heart rhythm categories

regular

regularly irregular

irregularly irregular

respiratory rate

12-20 breaths per minute

blood pressure ranges

Diastolic: 60-90mmHg

Systolic: 90-140mmHg

oxygen saturation

normal: 95-100% (room air)

Hypoxaemia: <92%

temperature range

36.1 - 37.9oC

fever could signify

infection (e.g. endocarditis, pericarditis, pneumonia)

peripheral perfusion of hands

well perfused: warm and pink, normal CRT

shut down: cold and pale, reduced CRT

capillary refill time (CRT)

apply pressure to the nail bed, pressing over the top of the fingernail until it turns white

Release the pressure and count the number of seconds it takes for the colour to return to the nail bed

Colour should return in less than 2 seconds

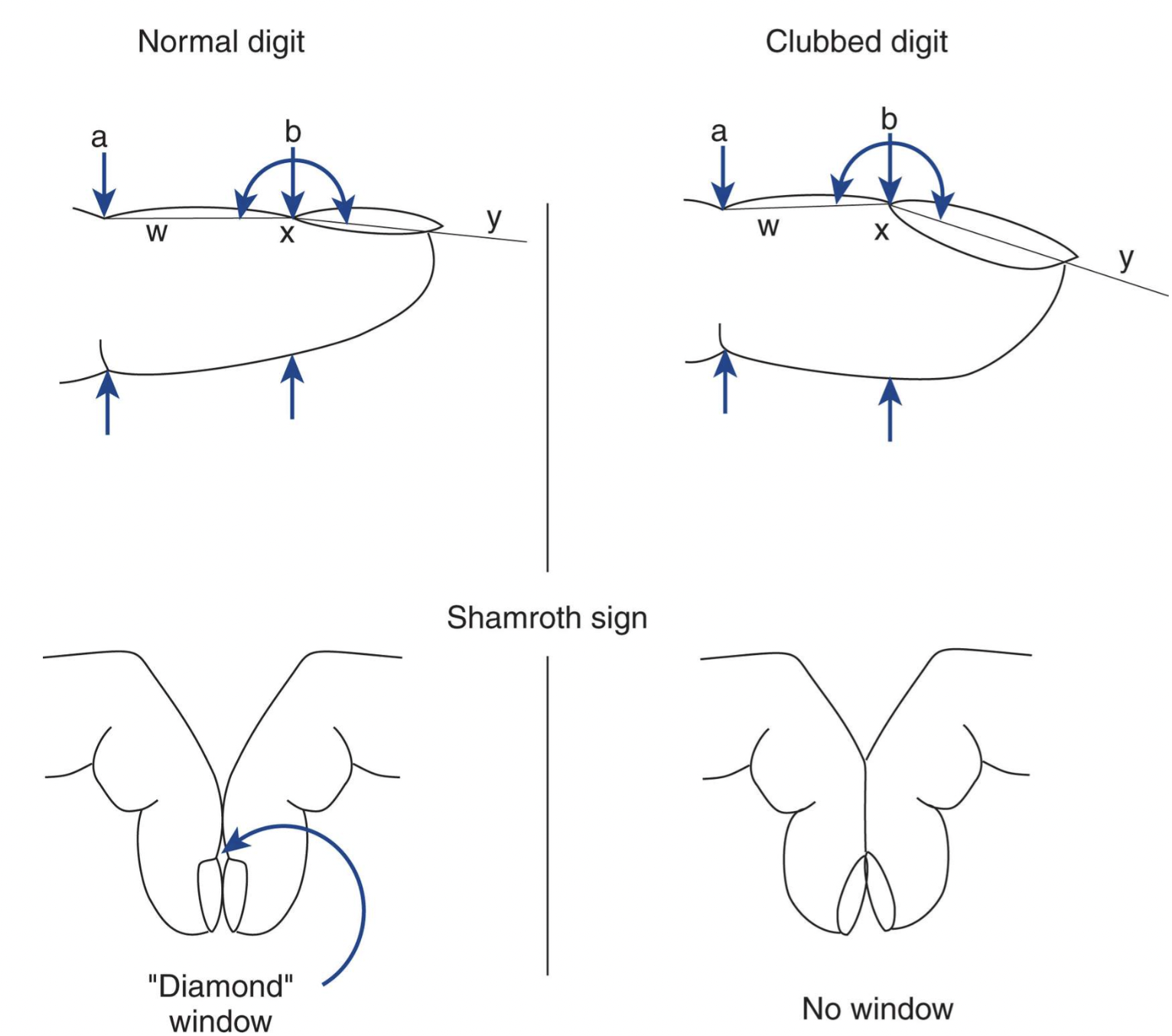

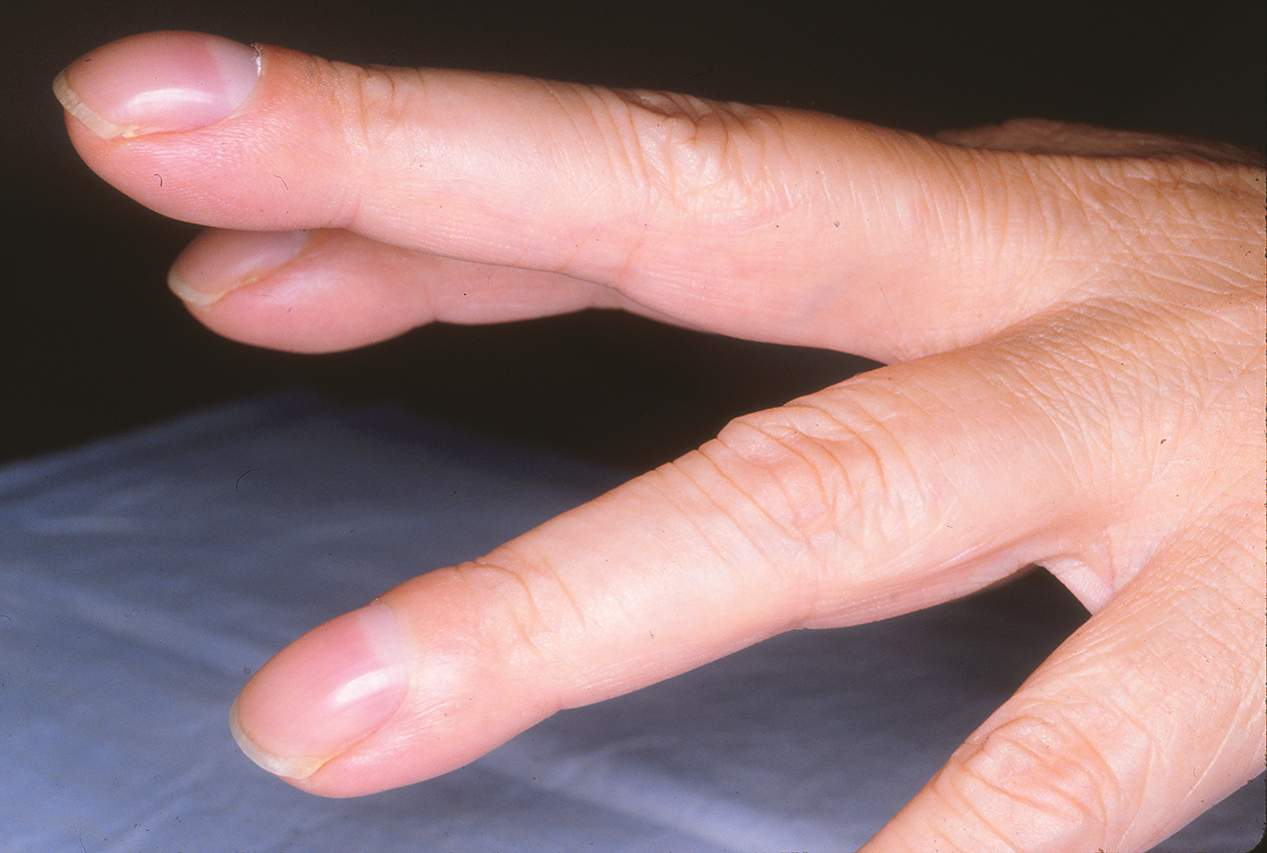

clubbing

loss of normal hyponychial angle:

the angle between the nail bed and the cuticle increases and rounds out

nails curve downwards

Schamroth’s sign:

Ask the patient to place the dorsal surfaces of the terminal phalanges of index back-to-back.

Normal: A small diamond-shaped window of light is visible between the nails.

Positive Schamroth’s Sign: No window — the space is obliterated due to the nails being more convex and the tissues swollen, indicating clubbing.

linked with cyanotic congenital heart disease

splinter hemorrhage

most commonly trauma related

can be a peripheral sign of infective endocarditis due to:

Microemboli (tiny clots or infected material from heart valves) traveling through circulation

or

Vasculitis (immune complex deposition) causing damage to capillaries

tobacco staining

sign of smoker

risk factor for ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease

xanthomata

lipid deposits under the skin suggests hyperlipidaemia → risk factor for ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease

typically seen over extensor tendons such as on the back of the hand (wrist) or the elbows

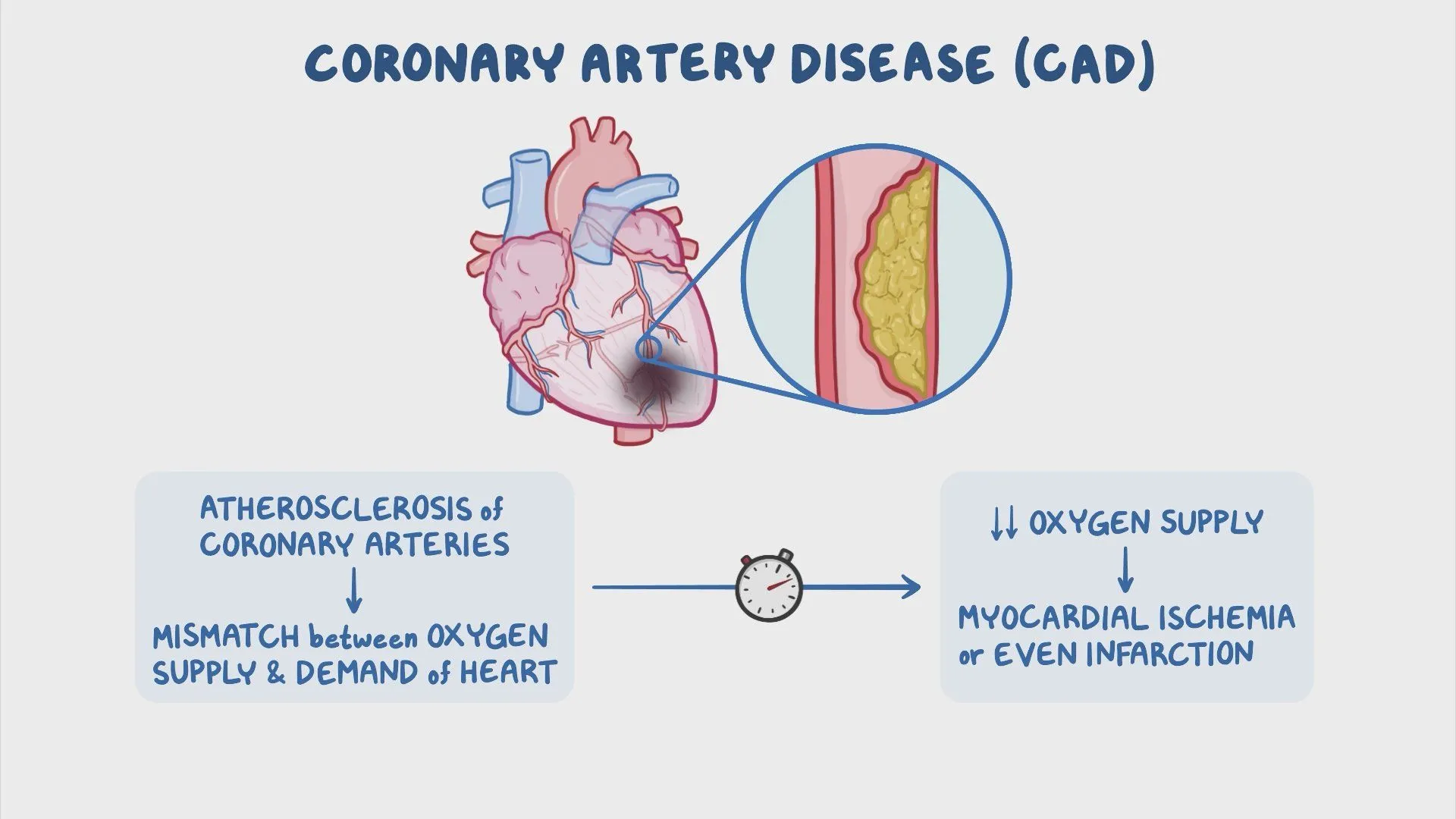

ischaemic heart disease

Also called Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

reduced blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium) occurs due to narrowing or blockage of coronary arteries

usually from atherosclerosis

Pathophysiology:

Atherosclerosis → Plaque buildup in coronary arteries

↓ Blood supply to myocardium → Myocardial ischaemia

Can be stable or acute

Clinical Presentations:

Stable Angina: Chest pain on exertion, relieved by rest

Unstable Angina: Chest pain at rest or minimal exertion

Myocardial Infarction (MI): Prolonged ischaemia → Heart muscle damage

Silent ischaemia (especially in diabetics)

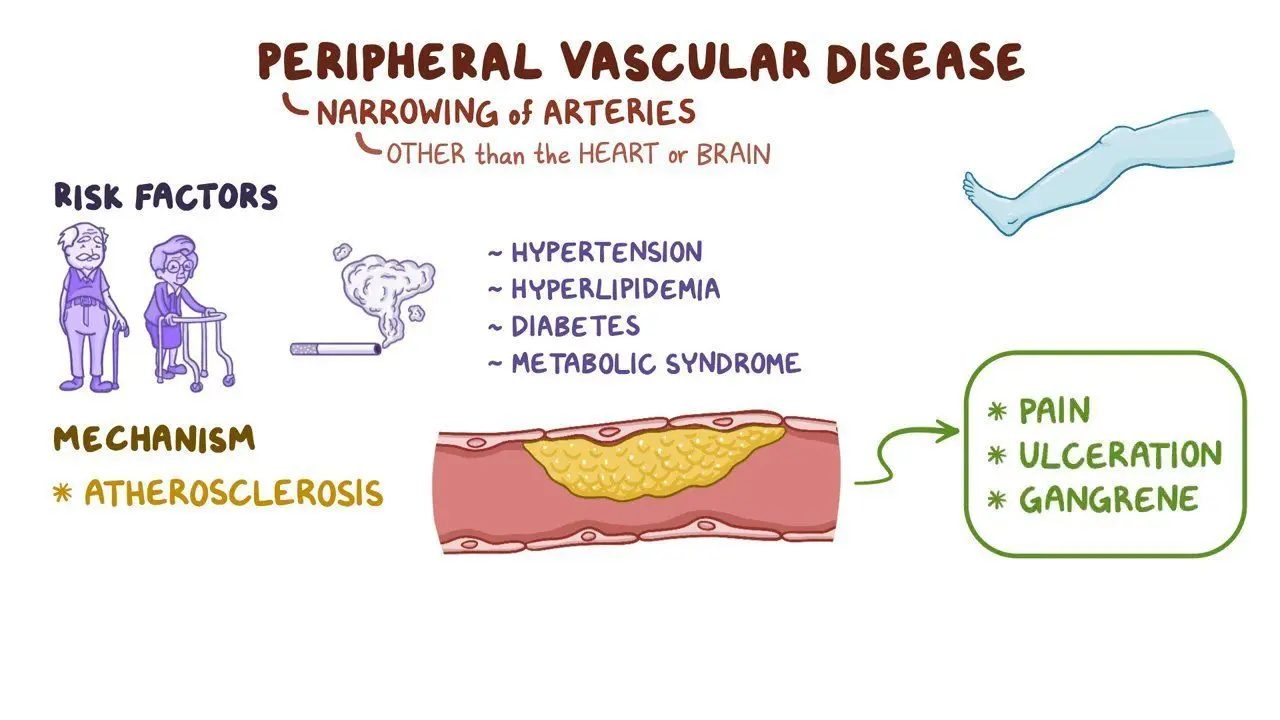

peripheral vascular disease

Also called Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD)

arteries supplying the limbs, especially the legs, become narrowed or blocked

due to atherosclerosis

results in poor circulation

Pathophysiology:

Atherosclerosis in peripheral arteries

↓ Blood flow to limbs, especially during exercise

→ Ischaemic muscle pain

Clinical Presentations:

Intermittent claudication:

Cramping leg pain during walking

relieved by rest

Critical limb ischaemia:

Pain at rest

non-healing ulcers

gangrene

Diminished pulses:

cool or pale skin

poor wound healing

angina

chest pain or discomfort caused by reduced blood flow to the heart muscle

symptom of CAD

Stable angina:

most common type

occurs predictably: usually during exertion or emotional stress

relieved by rest or medication.

Unstable angina:

more serious type

follows an irregular pattern

not relieved by rest or medication

can be a sign of a more severe heart problem and may precede a heart attack.

Variant angina (Prinzmetal's angina):

occurs at rest due to a spasm in the coronary arteries (myocardial vessel vasospasm), which can reduce blood flow to the heart

Symptoms of Angina:

Chest pain or discomfort that may feel like squeezing, tightness, or pressure.

Pain or discomfort that may radiate to the neck, jaw, arms, shoulders, or back.

Feeling of indigestion, heartburn, or nausea.

Shortness of breath, fatigue, or dizziness

Osler’s nodes

tender palpable nodules

rare, peripheral signs of infective endocarditis

noted on the finger pulps or thenar/hypothenar eminences

thought to be due to:

Septic Microemboli (tiny clots or infected material from heart valves) traveling through circulation

or

Vasculitis (immune complex deposition) causing damage to capillaries

Janeway lesions

non-tender, late peripheral sign of infective endocarditis

found on the palms or finger pulps and are thought to be septic emboli

rarely seen in western cultures due to advances in medical treatment

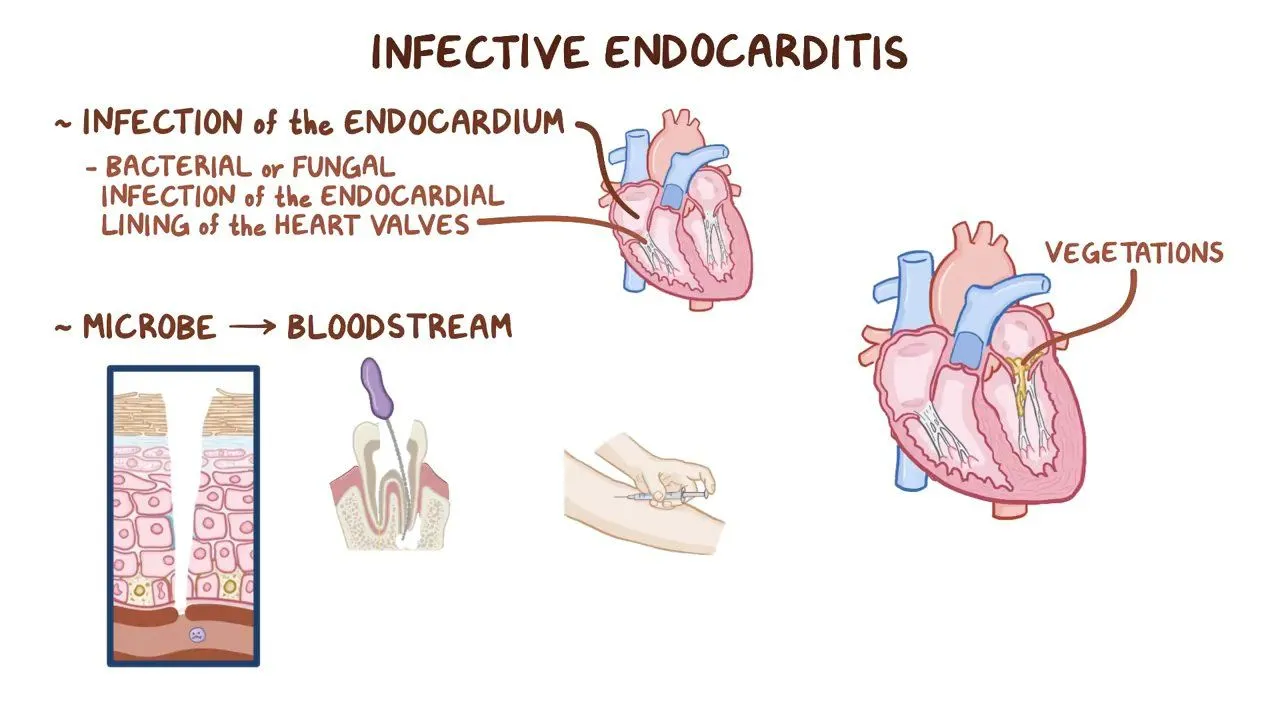

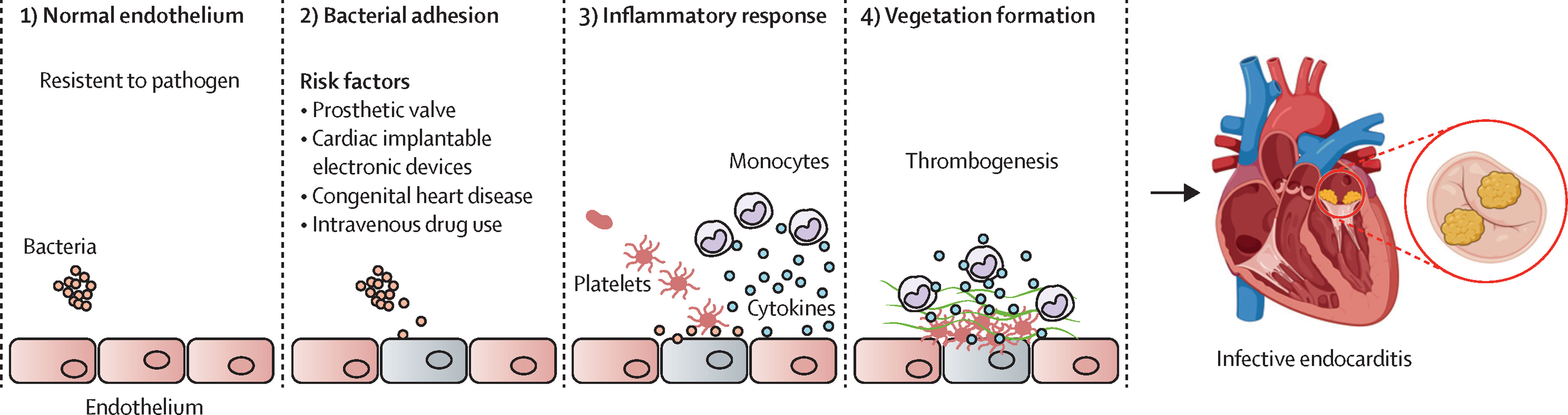

infective endocarditis pathogenesis

Endothelial Damage

Damaged endothelium exposes collagen and tissue factor, promoting platelet-fibrin thrombus formation

Bacteremia

Microorganisms (bacteria or fungi) enter the bloodstream via:

Dental procedures

Poor gingival health

IV drug use

Surgery

Infected devices (e.g., catheters, prosthetic valves)

Vegetation Formation

Bacteria adhere to the thrombus → form infected vegetations composed of fibrin, platelets, and microorganisms

These vegetations are protected from immune cells, allowing bacteria to multiply

Destructive and Embolic Effects

Vegetations can destroy valve tissue

→ regurgitation or heart failure

Septic Microemboli (tiny clots or infected material from heart valves) can break off

→ travel to skin, brain, kidneys, etc.

→ infarctions or abscesses

Immune complexes can deposit in tissues

→ vasculitis, glomerulonephritis

infective endocarditis clinical features

Splinter hemorrhages

Linear nailbed bleeding (septic microemboli or immune complexes (vasculitis))

Osler nodes

Tender, palpable nodules on finger pulps or thenar/hypothenar eminences (septic microemboli or immune complexes (vasculitis))

Janeway lesions

Non-tender lesions on palms or finger pulps (septic microemboli)

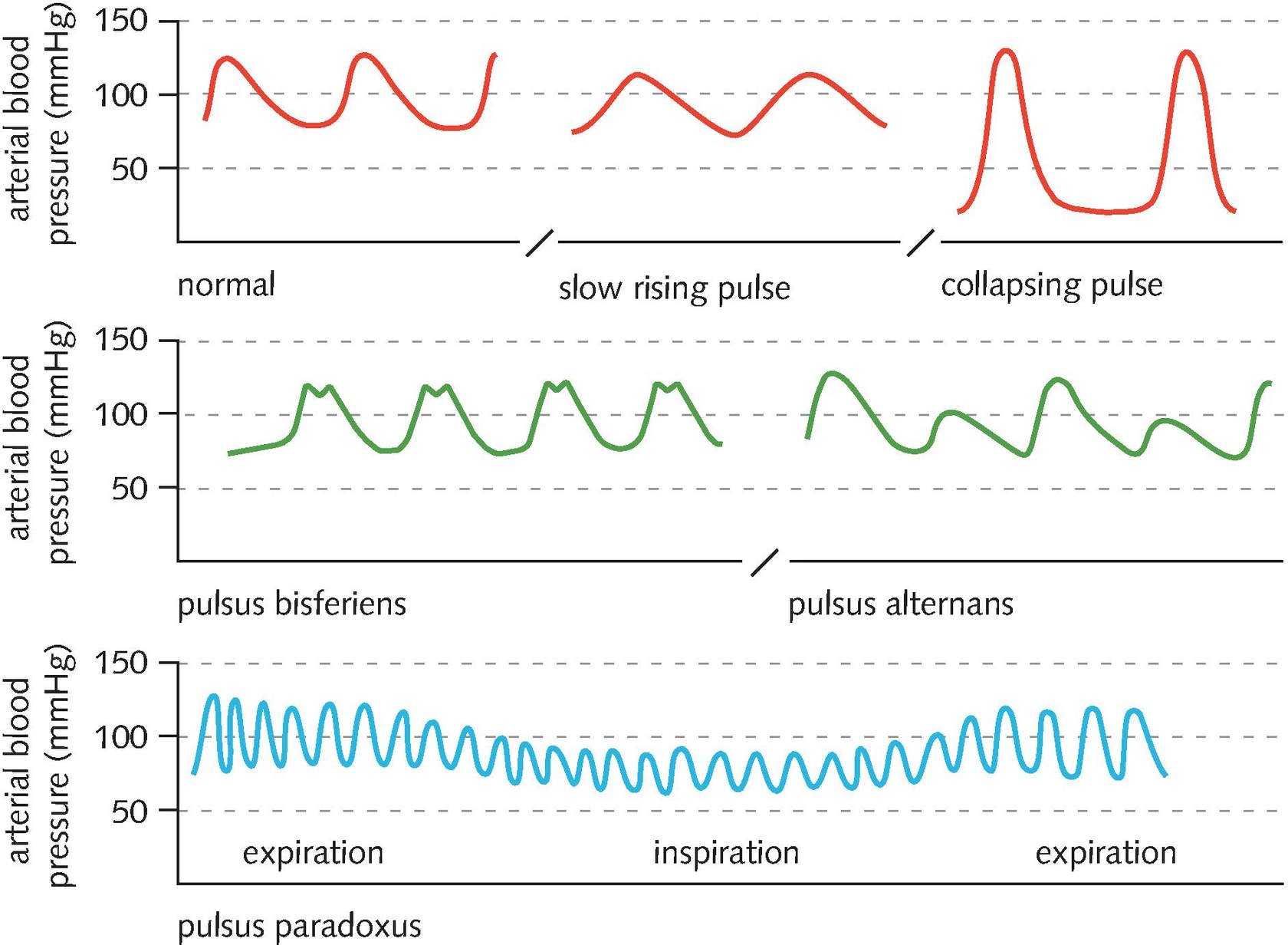

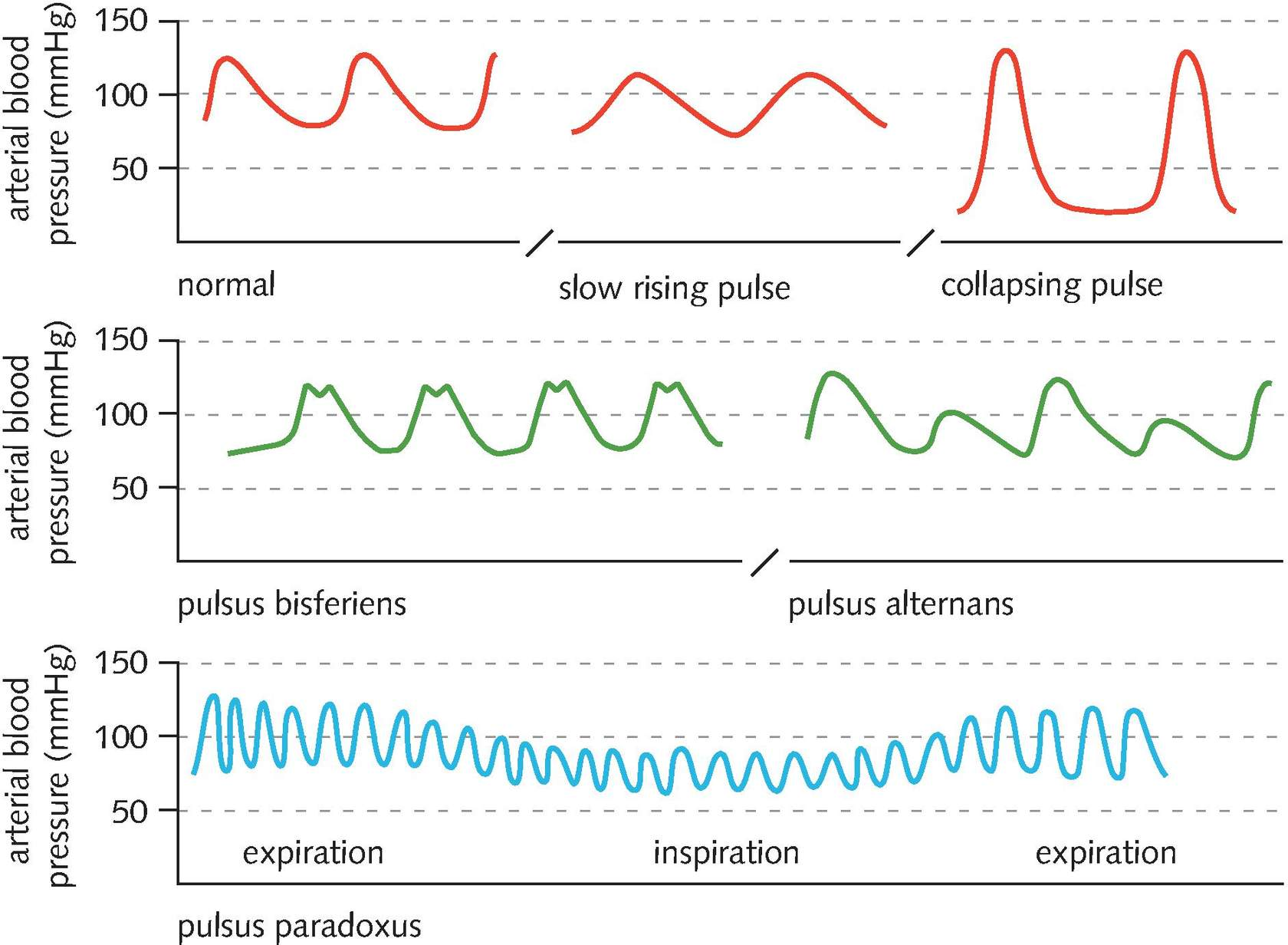

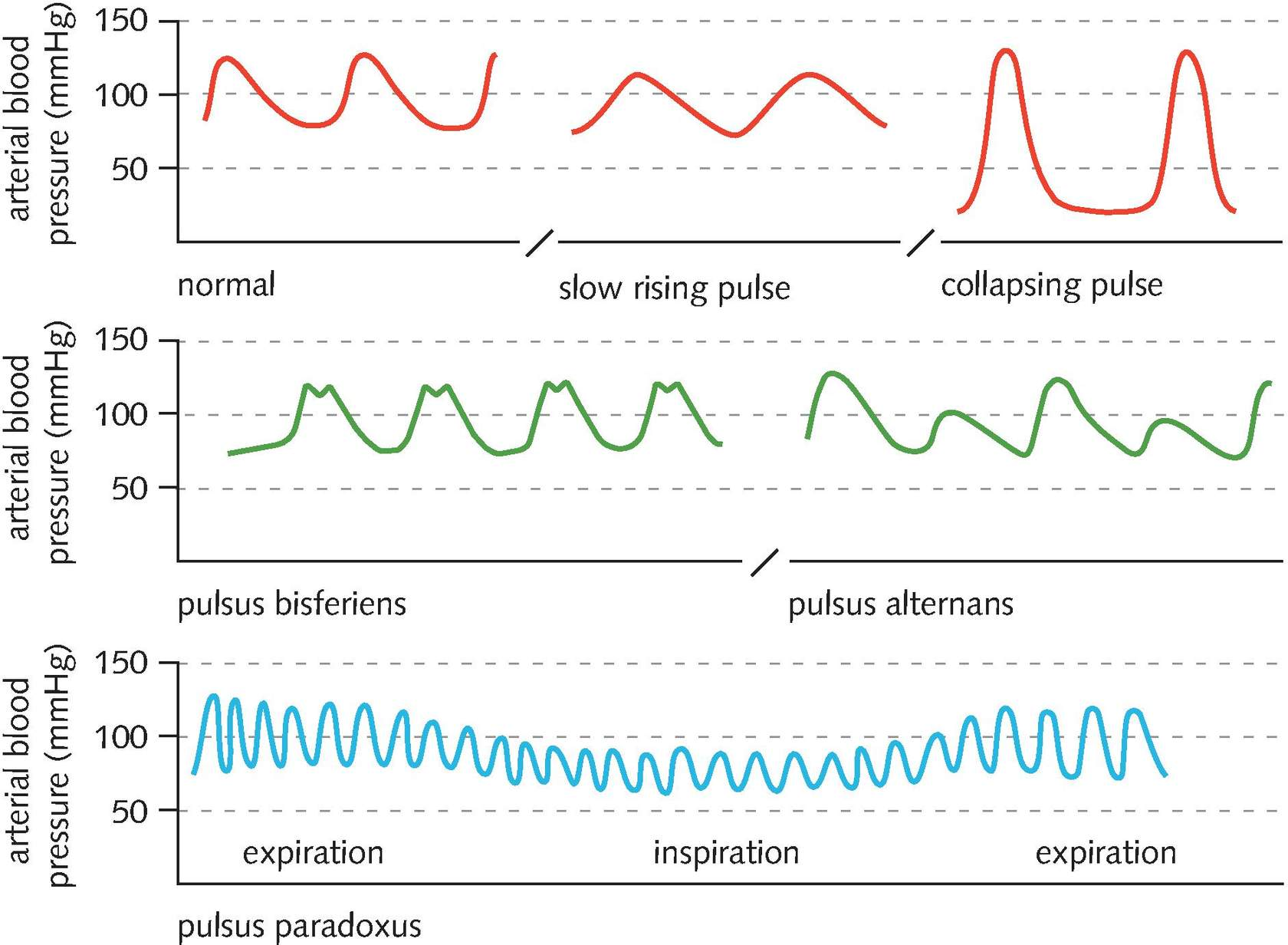

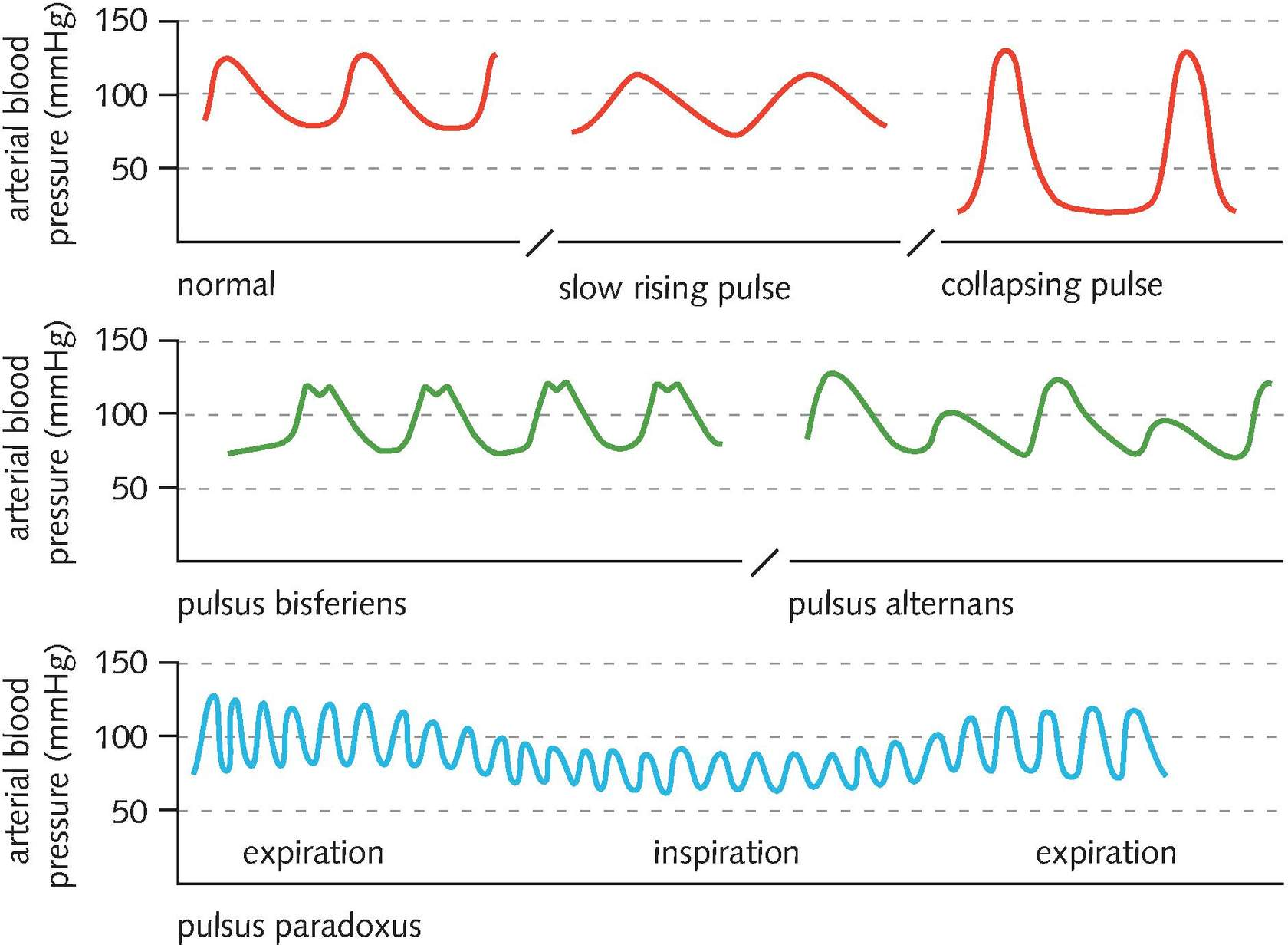

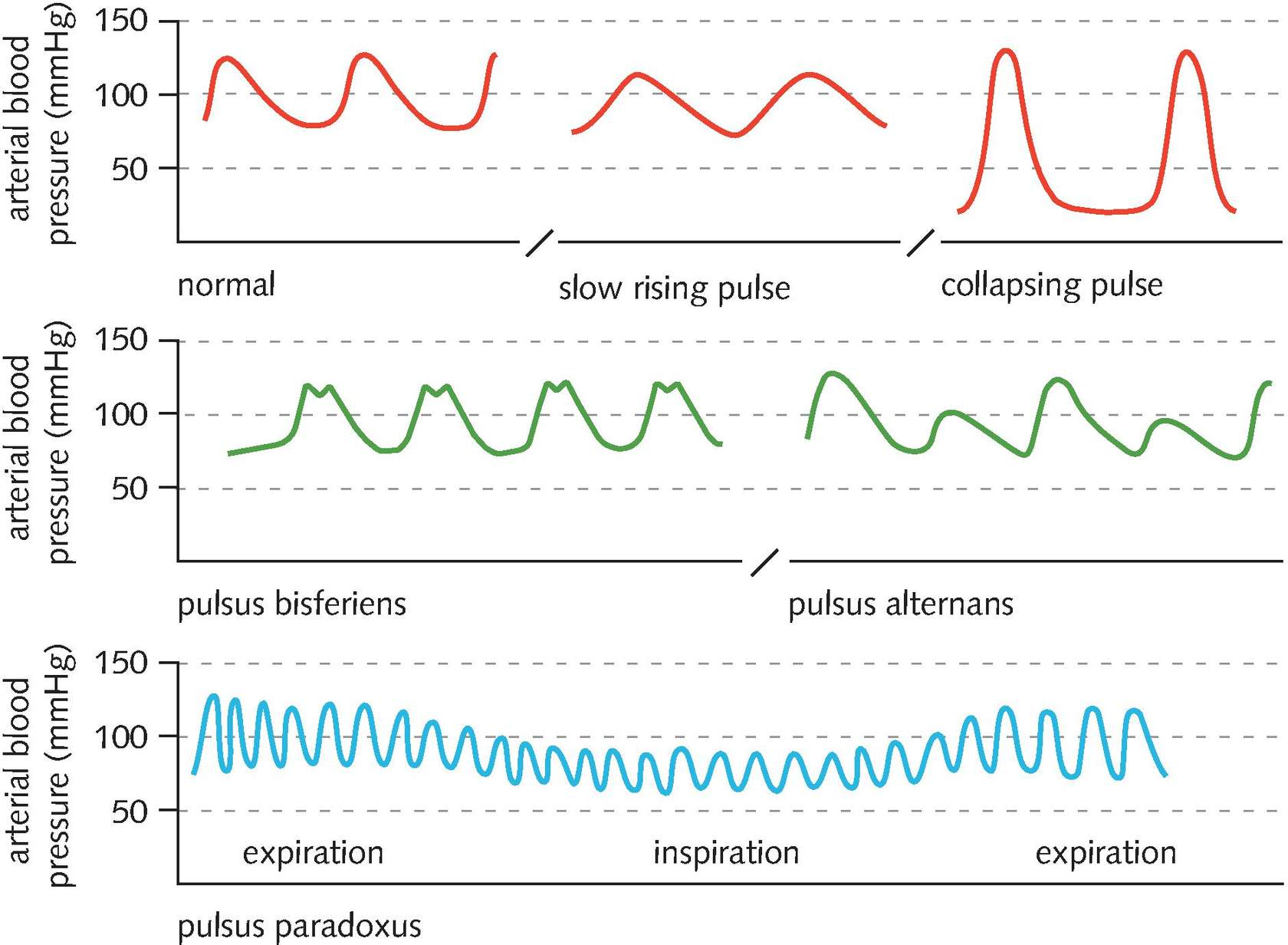

blood pressure

normally there is a small, non-palpable drop in systolic blood pressure on inspiration

If this drop is palpable, it is called pulsus paradoxus

>10mmHg drop in systolic pressure during inspiration may indicate pericardial tamponade or severe asthma

The pulse pressure is defined as the systolic pressure minus the diastolic pressure

A wide pulse pressure is a sign of aortic regurgitation (80-100mmHg)

A narrow pulse pressure is a sign of aortic stenosis (less than 25% of the systolic pressure)

An average pulse pressure is approximately 40mmHg

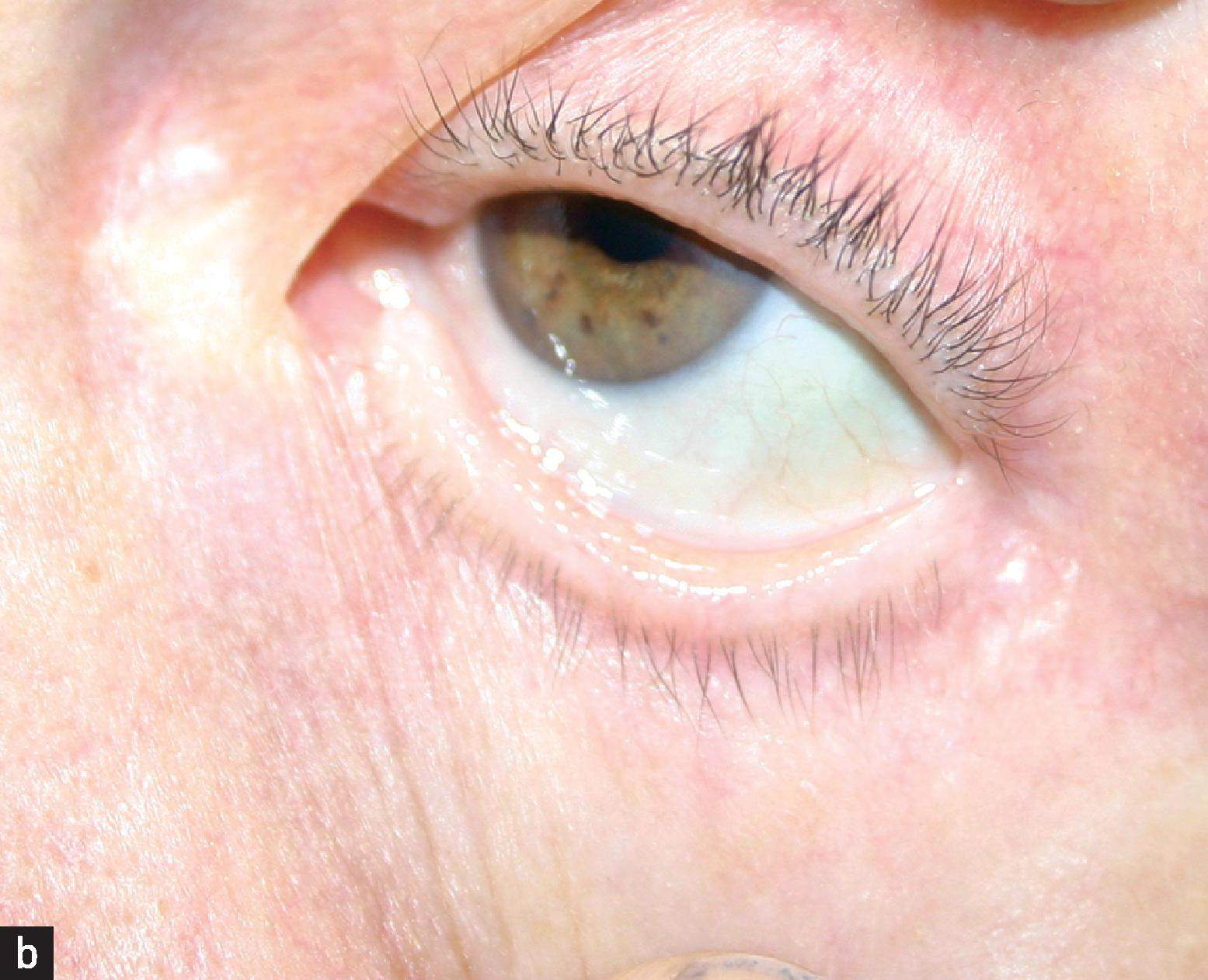

scleral jaundice

yellowing of the sclera (the white of the eye)

e.g. in cardiovascular disease can signify cardiac failure associated with hepatic congestion

signs of anemia

conjunctival pallor

tachycardia

systolic murmur

xanthelasma

seen near the upper inner eyelid

yellow-orange cholesterol deposits under the skin

sign of hyperlipidaemia in young patients (normal for old)

corneal arcus

grey/white ring around the iris

sign of hyperlipidaemia in young patients (normal for old)

Gingival health and dentition

check for signs of gum disease or infection

Poor gingival health = entry route for bacteria causing infection endocarditis

Angular stomatitis

inflammation at the edges of the mouth

may be present in iron and/or vitamin B deficiencies

mucosal petechiae

small red-purple haemorrhages on the oral mucosa, often seen on the palate

sign of infective endocarditis

collapsing pulse

Rapid upstroke, higher volume, fast downstroke (i.e. rises and falls quickly)

Occurs with:

physiological states:

fever

exercise

pregnancy

hyperdynamic circulation:

anaemia

thyrotoxicosis

large arteriovenous fistula

commonly associated with aortic regurgitation

bifid pulse

can feel two separate peaks (a double impulse) during systole

Occurs with:

co-existing aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation

hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM)

(pulsus bisferiens)

plateau pulse

Slow-rising or anacrotic (small volume, slow-rising)

Occurs in aortic stenosis

pulsus alternans

Alternating strong and weak beats

Can be caused by left ventricular failure

carotid pulse volume categories

strong

weak and 'thready'

normal

carotid pulse character categories

Collapsing pulse

Bifid pulse (pulsus bisferiens)

Plateau pulse

Pulsus alternans

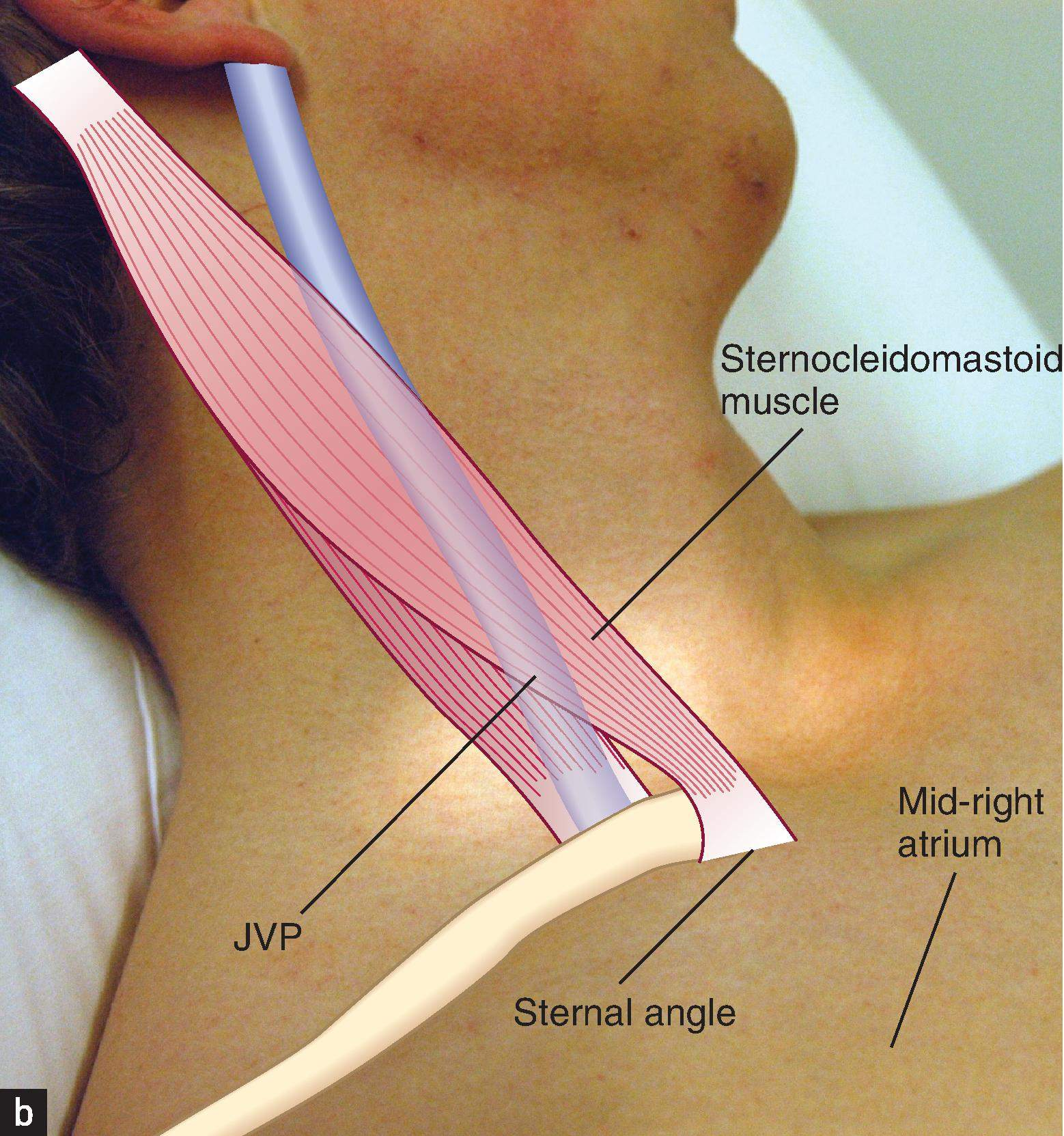

JVP

jugular venous pressure

reflects right atrial pressure

visible in around 50% of people

elevated JVP can indicate:

right heart failure

fluid overload

say: “I’m looking at the base of the neck between the two heads of the sternocleidomastoid”"

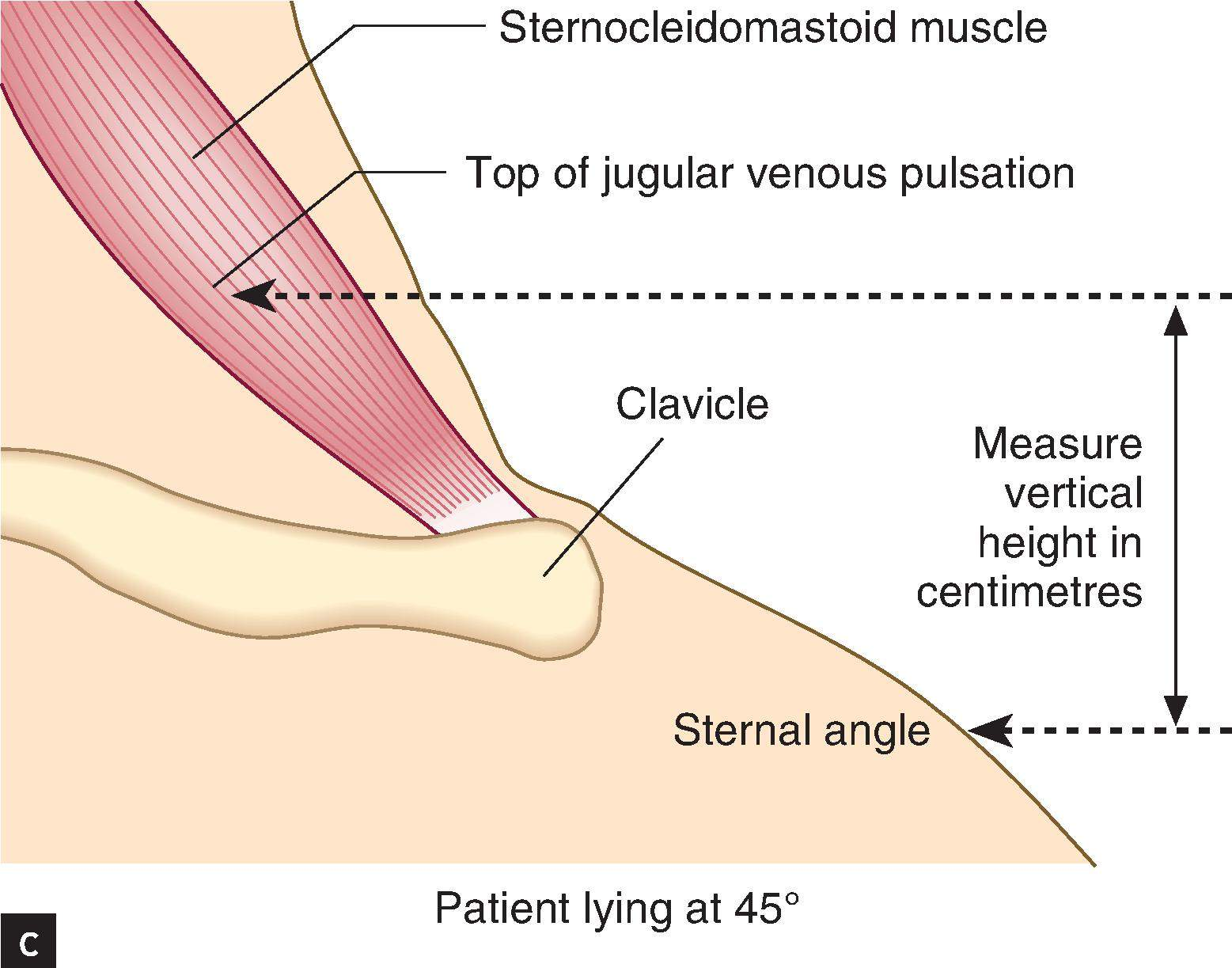

how to measure JVP

patient is positioned at a 45° angle with their head supported on a pillow

Ask the patient to turn their head away from you slightly

Look at the base of the neck for a double pulsation

say: “I’m looking at the base of the neck between the two heads of the sternocleidomastoid”

then:

Identify the highest point of the pulsation up the internal jugular vein and draw an imaginary horizontal line across to vertically above the sternal angle (Angle of Louis)

Measure or estimate the vertical distance between this point and the sternal angle

A normal JVP height is 3cm or less

then:

abdominojugular reflux test:

ask whether the patient has any abdominal pain

compress over the centre of the abdomen firmly, using the flat of your hand

hold for 10 seconds while watching the JVP

abdominal pressure increases venous return to the right atrium

it is normal for the JVP to rise transiently

should return to normal within a few seconds as the compliance of the right heart and vessels adapts to the increased volume

A positive (bad) test is when the JVP remains elevated at > 4 cm for the full 10 seconds that you maintain pressure

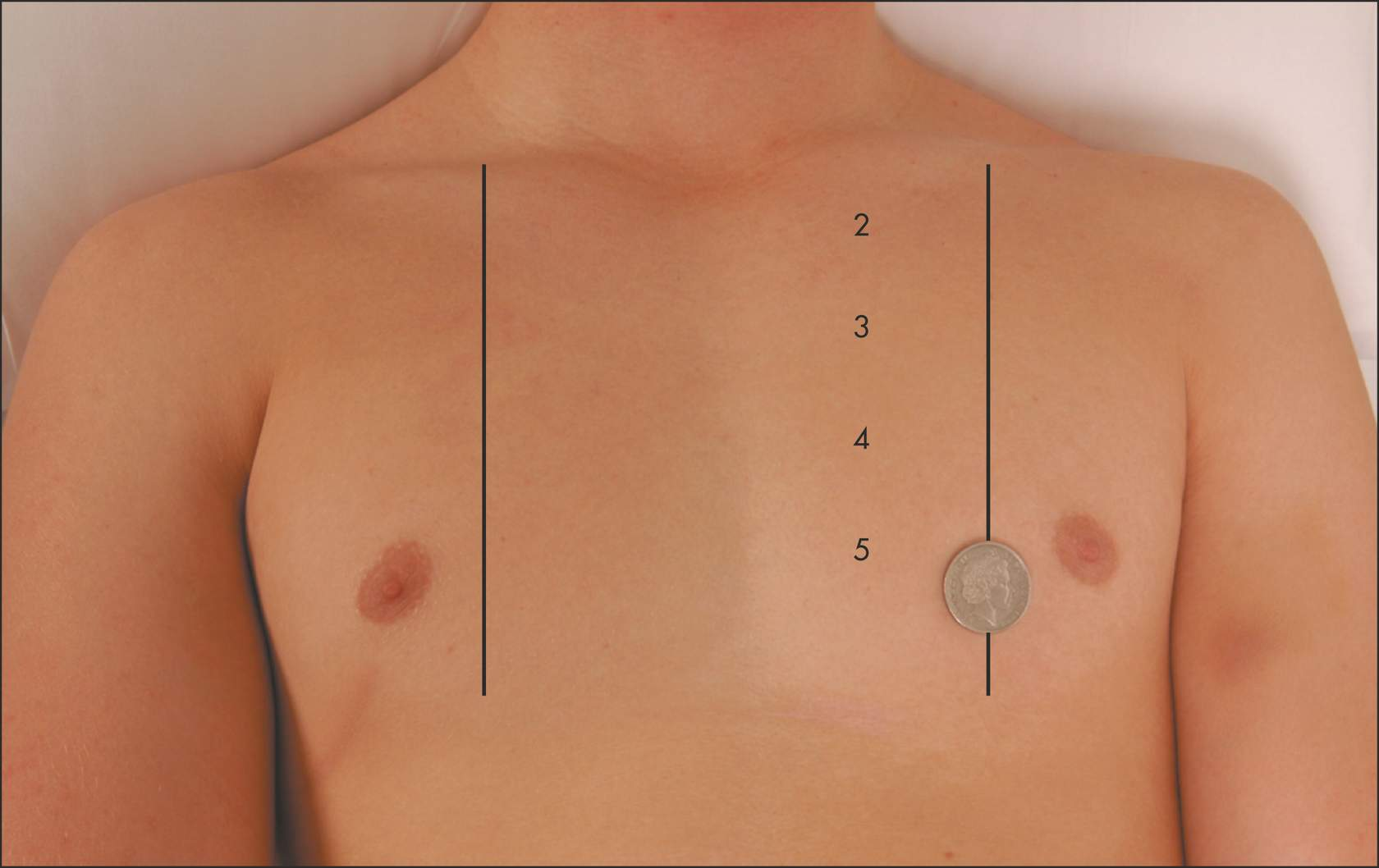

types of visible pulsatations

Apex of the heart (coin)

in a thin person

in cardiac conditions that cause a forceful apex beat

A right ventricular impulse may be seen in the 3rd, 4th or 5th intercostal spaces at the left sternal edge

in right ventricular hypertrophy

Over the pulmonary artery at the left 2nd intercostal space

if severe pulmonary hypertension is present

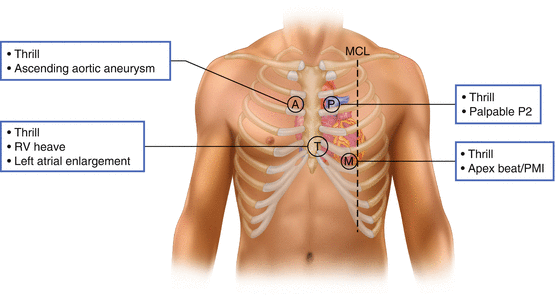

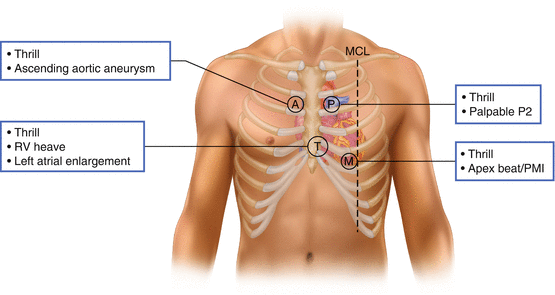

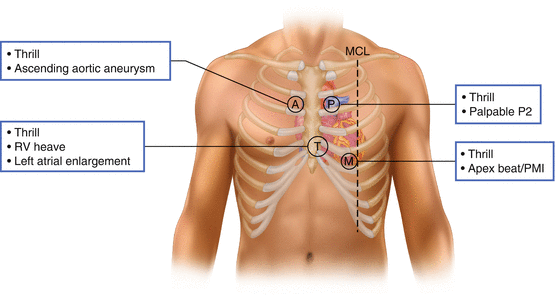

apex beat palpation

5th left intercostal space (demonstrate counting out the rib spaces)

the tips of all the fingers of the right hand flat on the chest (palpable in 50% patients)

roll the patient into the left lateral position

Identify:

whether or not it is palpable

normal position, or is it displaced left or right

e.g. left displacement in volume overload in mitral regurgitation

character:

A forceful or pressure-loaded 'heaving' apex beat

in left ventricular hypertrophy

Causes:

hypertension

aortic stenosis

A volume-loaded 'thrusting' apex beat (displaced laterally and inferiorly)

in left ventricular dilatation

Causes:

mitral regurgitation

dilated cardiomyopathy

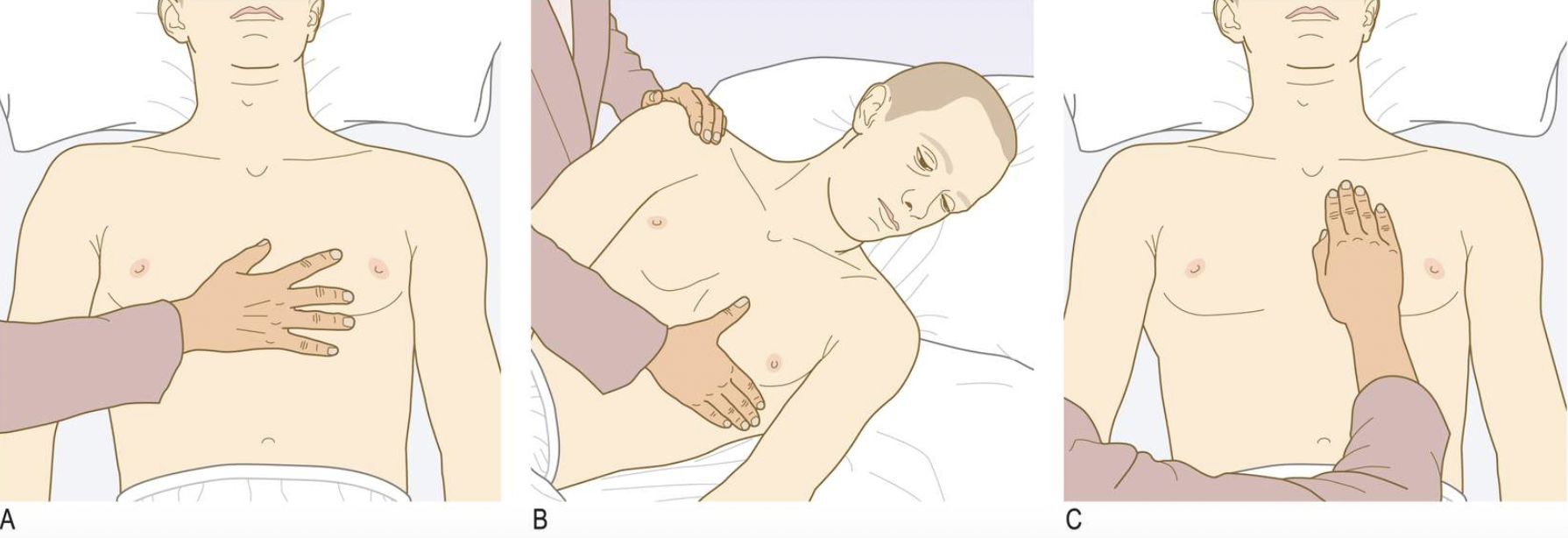

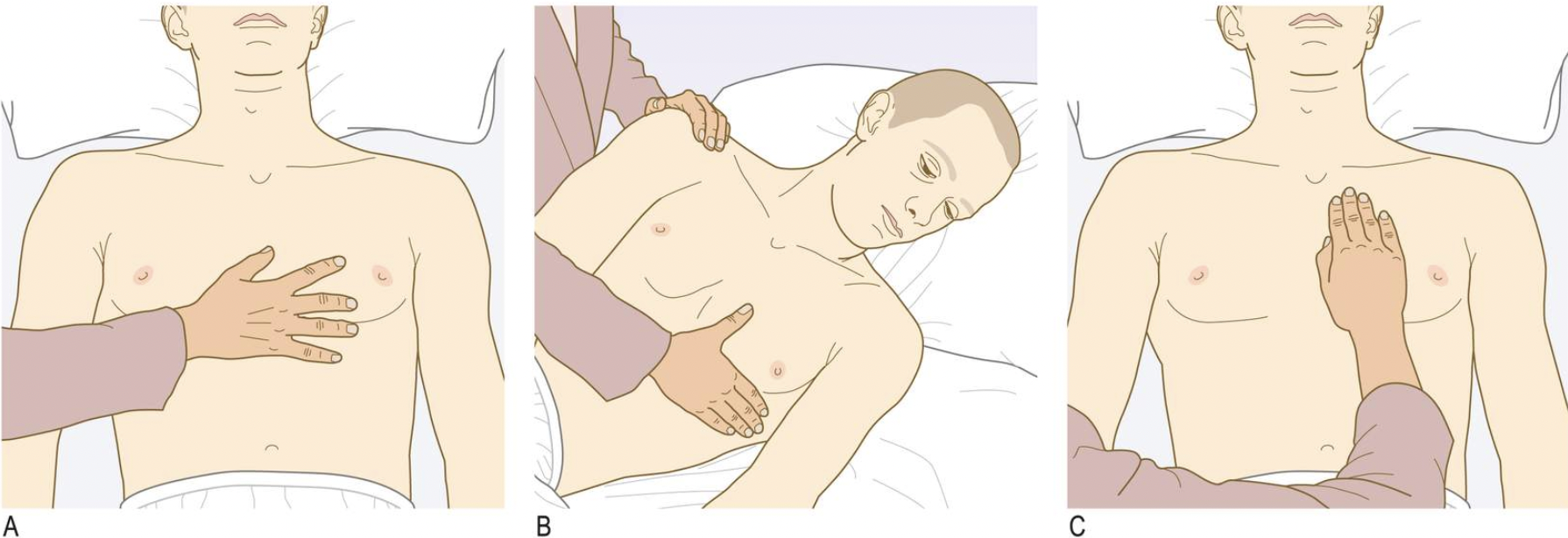

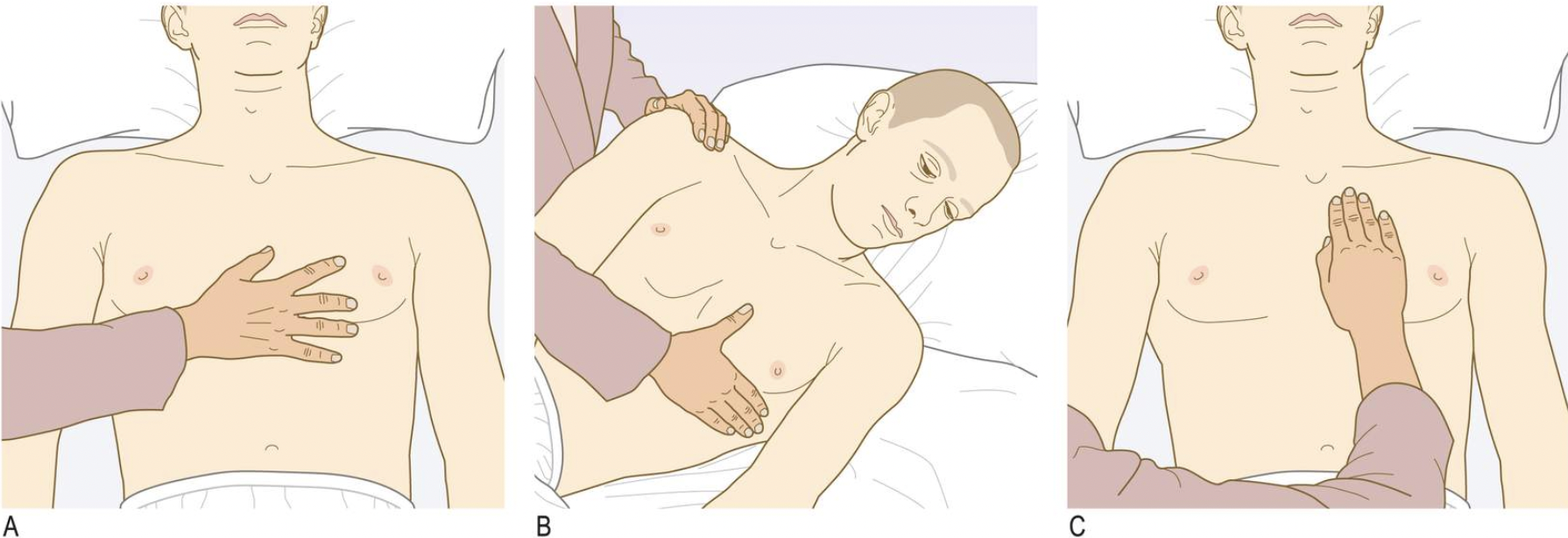

tricuspid palpation

Sit the patient forward

use the heel of the hand flat to palpate over the left sternal edge

Identify:

heaves (or ‘parasternal impulse’)

in right ventricular hypertrophy

pulmonary hypertension

chronic lung disease: chronic hypoxia leading to constriction of the pulmonary vasculature

left heart failure causing congestive cardiac failure

if the patient is thin

place your fingers flat on the chest (A)

identify:

thrills (palpable murmur that feels like a rapid vibration under your fingers)

suggests severe valve disease

useful for murmur grading

mitral palpation

after palpating for the apex beat, with patient rolled to their left side

feel with the flat of your hand (with fingers extended) (B)

identify:

thrills (palpable murmur that feels like a rapid vibration under your fingers)

suggests severe valve disease

useful for murmur grading

aortic and pulmonary palpation

with the patient sitting forward

feel with the flat of your hand (with fingers extended) over the aortic and pulmonary areas (base of the heart) (C)

identify:

thrills (palpable murmur that feels like a rapid vibration under your fingers)

suggests severe valve disease

useful for murmur grading

splitting

clearly heard gap in the second heart sound (S2, closure of aortic and pulmonary valves)

significant delay between aortic valve closure and pulmonary valve closure

normal: on deep inspiration

pathological: right bundle branch block (abnormal conduction)

third heart sound (S3)

unexpected heart sound heard shortly after S2 (during early diastole)

heard:

with the bell (low pitched)

over the apex (patient left lateral position/side) or the left sternal edge

can occur:

in healthy individuals (especially younger patients)

or

where there is high cardiac output

or

left ventricular failure and dilatation

fourth heart sound (S4)

unexpected heart sound heard shortly before S1 (late diastole)

heard:

with the bell (low pitched)

over the apex (patient left lateral position/side) or the left sternal edge

can occur in high pressure states such as:

aortic stenosis

hypertension

murmurs

additional heart sounds due to turbulent blood flow (stenosis or regurgitation (??))

if identified, describe:

Timing (during systole or diastole)

Location (over which area it is loudest)

Radiation (whether it can be heard anywhere else)

Effect of inspiration/expiration (right-sided are louder on inspiration, left-sided on expiration)

Effect of the Valsalva manoeuvre (murmurs of HOCM and mitral valve prolapse get louder on Valsalva, the rest get quieter)

Whether a thrill is present (represents more turbulence/louder murmur)

pericardial friction rub (probably not assessed)

inconsistent crunching sound which may occur in systole or diastole and may come and go

sometimes seen in pericarditis and is due to inflamed pericardial surfaces moving over each other

Auscultation steps

With the patient supine at 45°

Listen with the bell over the mitral area [for mitral stenosis, S3 or S4]

Palpate the carotid pulse simultaneously to identify S1 and S2

Ask the patient to roll to the left

mitral area [for mitral stenosis, S3 or S4]

Ask the patient to return to supine at 45°

Change to the diaphragm

mitral area [for mitral regurgitation]

in the axilla [for the radiation of mitral regurgitation]

tricuspid area [for any tricuspid murmurs]

Left sternal edge to the pulmonary area [for any aortic murmurs]

Pulmonary area [for any pulmonary murmurs]

Aortic area [for any aortic murmurs]

Change to the bell

Listen over both carotids [for radiation of aortic stenosis and for carotid bruit]

Ask the patient to hold their breath

Listen over both carotids [radiation of aortic stenosis (bilateral) or carotid bruit (unilateral or bilateral)]

Dynamic manoeuvres - Leaning Forward & Inspiration/Expiration

Dynamic manoeuvres - Valsalva manoeuvre

![<ul><li><p><span style="font-size: inherit; font-family: inherit"><strong>With the patient supine at 45°</strong></span></p><ul><li><p>Listen with the <strong>bell</strong> over the mitral area [for mitral stenosis, S3 or S4]</p></li><li><p>Palpate the carotid pulse simultaneously to identify S1 and S2</p></li></ul></li><li><p><span style="font-size: inherit; font-family: inherit"><strong>Ask the patient to roll to the left</strong></span></p><ul><li><p>mitral area [for mitral stenosis, S3 or S4]</p></li></ul></li><li><p><span style="font-size: inherit; font-family: inherit"><strong>Ask the patient to return to supine at 45°</strong></span></p><ul><li><p>Change to the <strong>diaphragm</strong></p></li><li><p>mitral area [<em>for mitral regurgitation</em>]</p></li><li><p>in the axilla [<em>for the radiation of mitral regurgitation</em>]</p></li><li><p>tricuspid area<strong> </strong>[<em>for any tricuspid murmurs</em>]</p></li><li><p>Left sternal edge to the pulmonary area<strong> </strong>[<em>for any aortic murmurs</em>]</p></li><li><p>Pulmonary area [<em>for any pulmonary murmurs</em>]</p></li><li><p>Aortic area [<em>for any aortic murmurs</em>]</p></li><li><p>Change to the <strong>bell</strong></p></li><li><p>Listen over both carotids [<em>for radiation of aortic stenosis and for carotid bruit</em>]</p></li></ul></li><li><p><span style="font-size: inherit; font-family: inherit"><strong>Ask the patient to hold their breath</strong></span></p><ul><li><p>Listen over both carotids [<em>radiation of aortic stenosis (bilateral) or carotid bruit (unilateral or bilateral)</em>]</p></li></ul></li><li><p><span style="font-size: inherit; font-family: inherit"><strong><em>Dynamic manoeuvres - Leaning Forward & Inspiration/Expiration</em></strong></span></p></li><li><p><span style="font-size: inherit; font-family: inherit"><strong><em>Dynamic manoeuvres - Valsalva manoeuvre</em></strong></span></p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/6462789f-e349-4f30-a66a-a1732492eb77.png)

leaning forward inspiration and expiration

Ask the patient to lean forwards and breathe all the way in and hold then all the way out and hold

[To help differentiate between right sided murmurs (louder on inspiration) and left sided murmurs (louder on expiration)]

Tip: Right Inspiration, Left Expiration (RILE)

Listen over the aortic area with the diaphragm [for any aortic murmurs]

Listen over the left sternal edge (Erb's Point) with the diaphragm [for radiation of aortic regurgitation]

Valsalva maneuver

Ask the patient to take a deep breath in, then pinch their nose and try to pop their ears like on a plane [to accentuate the murmur of HOCM, mitral valve prolapse]

Listen over the left sternal edge (Erb's Point) with the diaphragm [for mid-systolic murmur of HOCM which gets louder on Valsalva]

Listen over the mitral area with the diaphragm [for late-systolic murmur of mitral valve prolapse which gets louder on Valsalva]

![<p><span style="font-size: inherit; font-family: inherit"><strong>Ask the patient to take a deep breath in, then pinch their nose and try to pop their ears like on a plane [to accentuate the murmur of HOCM, mitral valve prolapse]</strong></span></p><ul><li><p>Listen over the left sternal edge (Erb's Point) with the <strong>diaphragm</strong> [<em>for mid-systolic murmur of HOCM which gets louder on Valsalva</em>]</p></li><li><p>Listen over the mitral area with the <strong>diaphragm</strong> [<em>for late-systolic murmur of mitral valve prolapse which gets louder on Valsalva</em>]</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/46149d95-278a-406a-bbdf-864c6bdd8ccd.png)

carotid bruit

swooshing sound over carotid artery

may indicate plaque buildup in the carotid artery

HOCM

hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

heart muscle thickens, particularly in the septum, causing a blockage of blood flow

posterior back examination

Inspect for any scars and any obvious deformities of the chest wall or spine

Palpate for sacral oedema:

press over the sacrum gently for 5-10 seconds

allows any fluid to be pushed out of the way

After releasing the pressure, look and feel for a pit in the area (pitting oedema)

fluid will accumulate at the sacrum in patients who spend a lot of time in bed

Pitting oedema: sign of cardiac failure or fluid overload