psyc 290

1/766

Earn XP

Description and Tags

245-349 are for psyc 289 sorry

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

767 Terms

motivation

Defined as the process behind goal-directed behavior.

Illustrated through Chantal Petitclerc, a decorated Canadian Paralympic wheelchair racer, who emphasizes limitless potential as her driving force.

Motivation applies to various areas, from elite athletes to basic needs like hunger and achievement in academics.

emotion

Our lives are filled with emotional experiences, some of which have clear causes (e.g., being excluded from social plans).

However, emotions can sometimes be influenced in unexpected ways, as seen in studies like the Capilano Suspension Bridge experiment, where fear was misinterpreted as attraction.

Theories and research explore how emotions arise and what factors shape them.

psych and elite athletes

Psychologists, like Dr. Kimberly Amirault, help Olympic and professional athletes enhance performance through psychological preparation.

motives

needs, wants, interests, and desires that propel people in certain directions, propel us to achieve important goals.

so motivation involves goal directed behaviour

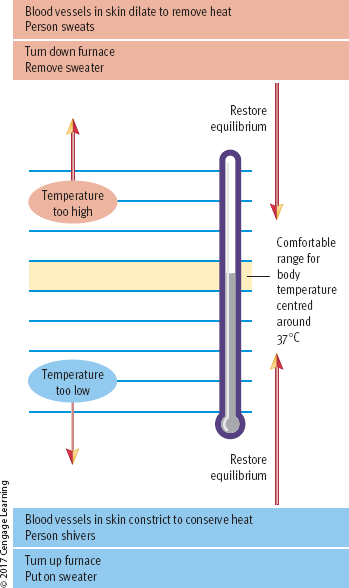

drive theories

explain motivation using the concept of homeostasis, where the body seeks physiological balance.

drive = internal state of tension that motivates behavior to reduce discomfort and restore equilibrium.

Key Points:

Clark Hull (1940s-1950s) developed drive theory, influenced by Freud (1915) and Hull (1943).

Example: Hunger acts as a drive—when you feel discomfort from not eating, you are motivated to find food, reducing the drive.

Homeostasis: The body automatically regulates temperature (e.g., sweating or shivering) to maintain balance, but sometimes external actions (e.g., adjusting a thermostat) are needed.

Limitations: Drive theories cannot explain all behaviors, such as eating when not hungry or seeking knowledge, which do not involve physiological imbalance.

incentive theories

external stimuli regulate motivation by pulling individuals toward goals (e.g., rewards, recognition, or achievements).

contrasts with drive theories, which focus on internal states pushing individuals toward action.

Key Points:

Incentives: External goals (e.g., food, money, grades) that motivate behavior, even if they don’t reduce physiological drives.

Push vs. Pull: Drive theories emphasize internal tension (push), while incentive theories focus on external rewards (pull).

Expectancy-Value Models (Atkinson & Birch, 1978): Motivation depends on:

Expectancy – The likelihood of achieving the incentive.

Value – How desirable the incentive is.

evolutionary theories

human motives are shaped by natural selection to maximize reproductive success.

Motives like dominance, affiliation, achievement, and aggression evolved because they provided survival and reproductive advantages.

Key Points:

Motivation & Evolution: Behaviors that enhanced survival and reproduction in hunter-gatherer societies were naturally selected.

Dominance in Males: Evolutionary benefits include:

Increased attraction from females.

Ability to take mates from rivals.

Intimidation of competitors.

Greater resource acquisition leading to more mating opportunities.

Affiliation & Belongingness: Strengthened survival by facilitating:

Cooperation in hunting and gathering.

Mutual defense.

Support for raising offspring.

Increased chances of reproduction.

Diversity of Motives: Humans have biological motives (e.g., hunger, thirst, sex) and social motives (e.g., achievement, power, intimacy).

hunger motivation

hunger is complex motivational system

but struggle w understanding factors regulating eating behaviour

Biological Factors in the Regulation of Hunger

regulated by brain, digestive system, and hormones

Early theories linked hunger to stomach contractions, but later research disproved this, leading to a focus on brain mechanisms, neural circuits, and hormonal regulation.

Key factors:

Brain Regulation (Hypothalamus & Neural Circuits)

Digestive System & Hunger Signals

Hormonal Regulation

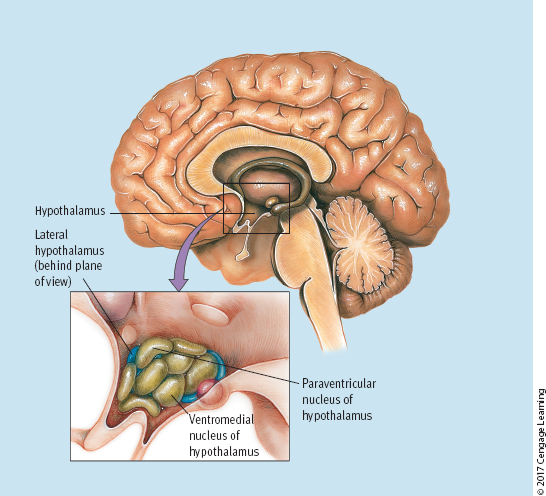

Brain Regulation of Hunger (Hypothalamus & Neural Circuits)

hypothalamus important

Early theories suggested the lateral hypothalamus (LH) stimulated hunger, while the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) suppressed it.

Current research points to the arcuate nucleus and paraventricular nucleus as central to hunger modulation.

Hunger regulation is controlled by complex neural circuits rather than simple on–off switches.

Digestive System & Hunger Signals

The stomach sends signals to the brain to indicate fullness via the vagus nerve.

Nutrient content in food also influences satiety signals.

Hormonal Regulation

Ghrelin: Released when the stomach is empty, promoting hunger.

CCK (Cholecystokinin): Released after eating, signaling fullness.

Leptin: Secreted by fat cells; high levels reduce hunger, while low levels increase it.

Insulin: Regulates blood sugar and influences hunger, responding to fat storage.

All these hormonal signals converge in the hypothalamus, particularly the arcuate and paraventricular nuclei.

environmental factors influencing hunger

Hunger is a biological need, but eating is influenced by social and environmental factors. Key factors include:

Food Availability and Related Cues

Learned Preferences and Habits

Food Availability and Related Cues

Palatability: People and animals eat more when food tastes better.

Quantity Available: Larger portions lead to greater consumption (bin model).

Variety: More food choices encourage eating (sensory-specific satiety).

Presence of Others: Eating increases (44% more) in groups but may decrease in certain social settings (e.g., women eating less with unknown men).

Stress: 40–50% of people eat more under stress, often opting for unhealthy foods.

Environmental Cues: Ads, images, and food-related stimuli increase hunger and eating.

Learned Preferences and Habits

Cultural Influence: Different regions favor different foods.

Innate Preferences: Humans prefer sweet tastes from birth and may have genetic preferences for high-fat and salty foods.

Conditioning: Positive or negative experiences shape food preferences.

Exposure: Repeated exposure increases food acceptance, but forcing food can have negative effects.

the roots of obesity

Obesity = body mass index (BMI) over 30

growing concern in North America, with 20.2% of Canadians classified as obese and even higher rates of overweight individuals.

20.2% of Canadians were classified as obese, while 40% of men and 27.5% of women were overweight, as reported by Statistics Canada (2015).

8.2 million men and 6.1 million women were at increased health risks due to weight.

This issue is not limited to adults—childhood obesity rates have tripled, leading experts to label it an epidemic. has spread from rich to poor nations

causes of obesity

evolutionary factors

genetic predisposition

Excessive Eating & Inadequate Exercise

Set Point Theory

Dietary Restraint & Overeating

Evolutionary causes of obesity

Historically, humans overate when food was available to prepare for future shortages.

In modern societies with abundant, high-calorie food, this tendency contributes to chronic overeating.

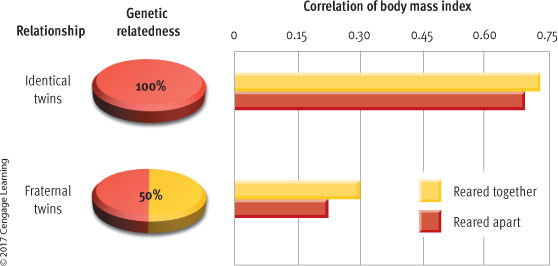

genetic predisposition for obesity

Twin studies show strong genetic influence on body weight.

identical twins reared apart were more similar in BMI than fraternal twins reared together, highlighting a strong genetic component.

Heritability estimates suggest genetics account for 61–73% of weight variation. (allison et al 1994)

61% of weight variation in men and 73% in women.

Excessive Eating & Inadequate Exercise

Highly processed, high-fat, high-sugar foods are widely available and heavily marketed.

Physical inactivity has increased due to sedentary lifestyles (desk jobs, cars, TV, video games).

Most Canadian children fail to meet physical activity guidelines.

girls aged 12–17 are especially vulnerable to inactivity (Statistics Canada, 2015).

affected by environment

North Americans spend nearly half their food dollars in restaurants where portion sizes are larger.

Unhealthy foods are heavily advertised and some theorists even argue that highly processed, high-fat, high-sugar foods may be addictive (Ahmed, 2012; Gearhardt & Corbin, 2012).

set point theory

The body resists weight loss through metabolic and hormonal adaptations.

Leptin levels drop, increasing hunger and reducing satiety.

The body defends against weight loss more effectively than weight gain.

because in ancestral environments, defending against starvation was more critical for survival.

Dietary Restraint & Overeating

Chronic dieters (restrained eaters) often feel guilt and binge eat when they believe they’ve broken their diet.

Restrained eaters swing between extreme dieting and overeating, often due to cognitive control breakdowns (e.g., alcohol, emotional distress).

The “I’ve already blown it” effect leads to binge eating. — “ive already blown it (my diet) so i might as well have as much as i want”

Anticipation of dieting can trigger overeating before a diet even begins.

Restrained eaters are influenced by media portrayals of thinness.

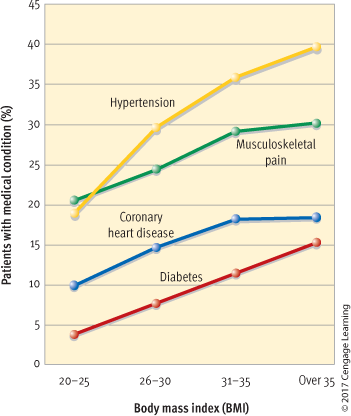

health risks of obesity

Increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, sleep apnea, arthritis, and some cancers.

Potential link to Alzheimer’s disease due to metabolic and inflammatory changes.

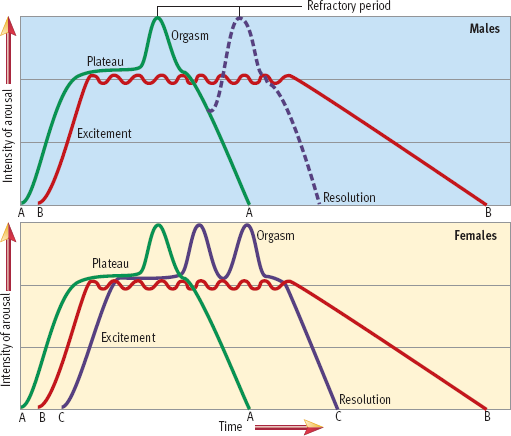

Four Phases of the Human Sexual Response (Masters & Johnson, 1966, 1970)

excitement phase

plateau phase

orgasm phase

resolution phase

excitement phase

Rapid increase in physical arousal (muscle tension, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure).

Vasocongestion (blood vessel engorgement):

Men: Erection of the penis, swelling of the testes.

Women: Swelling and hardening of the clitoris, expansion of vaginal lips, vaginal lubrication.

Plateau Phase

Arousal continues to build but at a slower pace.

Foreplay affects arousal fluctuations in both genders.

orgasm phase

Peak arousal is released in rhythmic muscular contractions in the pelvic area.

Gender differences:

Men: Typically have one orgasm followed by a refractory period.

Women: Can experience multiple orgasms in a short time.

Some women engage in intercourse without orgasming (Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2014).

resolution phase

Physiological changes from arousal gradually return to baseline.

If orgasm occurs, resolution is quicker; otherwise, sexual tension decreases more slowly.

Refractory period (in men):

A recovery phase where men are unresponsive to further stimulation.

Duration varies from minutes to hours and increases with age.

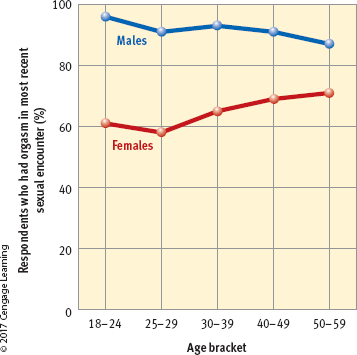

gender differences in orgasm consistency

Study (Laumann et al., 1994):

When asked if they “always” orgasm with a partner: 78% of men said yes. 28% of women said yes.

Study (Herbenick et al., 2010):

When asked about their most recent sexual encounter:

Men still reported orgasming more often than women, but the gap was smaller.

The gender gap in orgasm consistency decreases in older age groups.

Possible explanations:

Biological (Evolutionary):

Male orgasm consistency may enhance reproductive fitness.

Social and Psychological:

Gender differences in attitudes toward sex (e.g., guilt, cultural expectations).

Sexual scripts and practices that may not prioritize female pleasure.

Sexual Motivation & Cultural Influence

Sex is a major societal focus reflected in:

Media (movies, TV shows, novels).

Advertising (sex used to sell various products).

Social interactions (jokes, gossip, conversations).

Sexual activity trends in Canada (Canadian Community Health Survey, 2009/2010):

Teens (ages 15–17): 30% have engaged in sexual intercourse.

Young adults (ages 18–19): Nearly 70% have had intercourse.

These rates have remained stable since the mid-1990s (Roterman, 2012).s

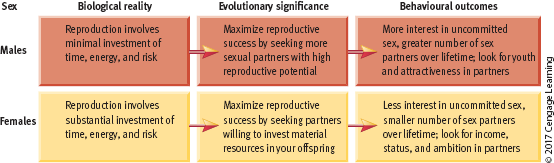

Parental Investment Theory (Trivers, 1972)

Core Idea: Mating patterns depend on the investment each sex makes in offspring (time, energy, survival risk).

Males: Minimal investment beyond copulation, leading them to maximize reproductive potential by mating with many females.

Females: Significant investment (pregnancy, breastfeeding), limiting their reproductive capacity. Therefore, they are more selective in choosing mates.

Implication: Males compete for mating opportunities; females choose mates based on qualities that ensure offspring survival.

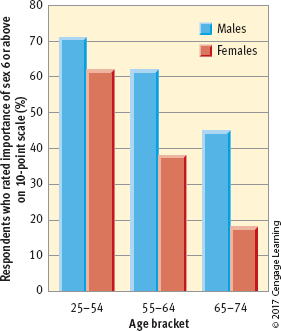

Gender Differences in Sexual Behavior

Men vs. Women:

Men: Show greater interest in sex, think about sex more often, initiate it more, and have more sexual fantasies. They also engage in more casual sex and view pornography more.

Women: Are more selective and less motivated by casual sex.

Middle Age Findings: The gender gap in sexual interest widens, with more men (62%) than women (38%) maintaining high interest in sex at ages 55-64.

Sexual Variety:

Men: Desire more sexual partners throughout their lives (18 partners on average).

Women: Prefer fewer sexual partners (5 on average).

Casual Sex:

Study (Clark & Hatfield, 1989): Men were more willing than women to engage in casual sex when approached by a stranger (75% of men vs. 0% of women).

Follow-up Study (Hald & Høgh-Olesen, 2010): Even in relationships, men were more likely than women to agree to casual sex (59% of men vs. 0% of women when not in a relationship).

Gender Differences in Mate Preferences

Men's Preferences:

Focus on youthfulness and attractiveness, correlating with fertility and health.

Women's Preferences:

Focus on intelligence, ambition, education, income, and social status, correlating with the ability to provide resources for offspring.

Global Study (Buss, 1989):

Women: Value status and financial prospects more than men across cultures.

Men: Value youthfulness and physical attractiveness more than women across cultures.

Criticism and Alternative Explanations for gender preferences for sex

Cultural and Economic Factors:

Material Resources Preference: Some argue women value economic clout due to cultural and economic limitations rather than biological imperatives.

Female Sexual Motivation: Gender disparity may be due to cultural suppression of female sexuality, rather than biological causes.

Gender Equality Impact:

Study (Zentner & Mitura, 2012): Smaller gender gaps in mating preferences were observed in countries with greater gender equality, suggesting cultural influences on sexual behavior.

sexual orientation

Refers to a person’s preference for emotional and sexual relationships with individuals of the same sex (homosexual), opposite sex (heterosexual), or both sexes (bisexual).

In Canada, same-sex marriage became legal in 2005.

Same-sex couples increased by 30% between 2001-2006.

Despite progress, hate crimes based on sexual orientation still persist, although recent trends show a decrease. Victims of these crimes are more likely to suffer physical injury than victims of other types of hate crimes.

kinsey continuum

Kinsey proposed that sexual orientation exists on a spectrum rather than as distinct categories.

Many individuals report having some same-sex experiences or attractions but do not identify as gay or bisexual.

Some surveys found that 75% of people with same-sex experiences do not label themselves as gay or bisexual.

Bisexuality is more common than once thought but is often misunderstood, with bisexual people sometimes being viewed as people in denial about their homosexuality.

The term “bisexual” may be limiting since some bisexuals may feel more attracted to one gender than the other, suggesting a more “nonexclusive” sexuality.

prevalence of homosexuality

Statistics Canada (2015) reported 1.7% of Canadians aged 18–59 identify as gay, and 1.3% as bisexual.

Other surveys show 8.2% have had same-sex sexual activity, and 11% report same-sex attraction.

The prevalence of homosexuality and bisexuality may be underreported due to the differences between self-identification and actual behaviors.

In the U.S., 3.5% of people self-identify as gay or bisexual, but 8.2% have engaged in same-sex sexual activities, and 11% report same-sex attraction.

Biological Theories

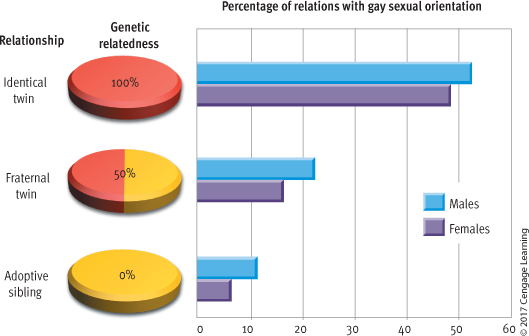

Genetics: Studies by Bailey and Pillard (1991) found that 52% of identical twins of gay men are also gay, suggesting a genetic influence. Similar findings were observed in lesbians.

Prenatal Hormones: Research suggests prenatal hormones might affect brain development, which could play a role in sexual orientation. Women exposed to higher levels of androgens during pregnancy were found to have higher rates of homosexuality.

Plasticity in Women's Sexuality: Women’s sexual preferences are more fluid than men’s, influenced by sociocultural factors. Lesbian and bisexual women often report changing their sexual orientation during adulthood, unlike men.

Environmental Factors: Environmental theories had limited success, but biological theories, including genetics and prenatal hormones, have gained more traction in recent years.

Affiliation Motivation

The need to connect with others and maintain social bonds, including companionship, friendship, and love.

Evolutionary Roots of affiliation motivation

Social bonds helped ancestors survive by sharing resources, protecting against predators, and increasing reproductive success.

Humans are inherently social animals, and isolation can lead to psychological and physical harm.

Being excluded (e.g., not invited to a party) can cause distress.

Threats to belonging trigger negative emotions like anxiety, jealousy, and depression.

belonging hypothesis (Baumeister & Leary, 1995)

Humans have a fundamental need for lasting, positive relationships.

Strong social connections enhance happiness and well-being.

Ostracism and the Fear of Rejection

Ostracism is being ignored or excluded in social settings. It causes emotional pain, can lead to extreme reactions, and is often linked to bullying.

Example: Amanda Todd, a B.C. teen, committed suicide after being cyberbullied and ostracized. She expressed her loneliness in a YouTube video.

Psychological & Neurological Impact of ostracism

Leads to pain, low self-esteem, and behaviors aimed at restoring belonging.

Activates brain regions linked to physical pain and unexpected outcomes.

how to mitigate ostracism

Research on mitigating ostracism is limited.

Featured Study (Rudert et al., 2017) examines how acknowledgment, even when excluded, can lessen its negative impact.

need for achievement

The need for achievement is the desire to master difficult challenges, surpass others, and meet high standards of excellence.

It plays a crucial role in economic growth, scientific progress, leadership, and creative arts (McClelland, 1985).

It is particularly evident in high-achieving individuals like Chantal Petitclerc (Paralympian), Steve Nash (NBA MVP), and historical figures like Marie Curie, Nelson Mandela, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Measuring Achievement Motivation

Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) (Smith, 1992; Spangler, 1992) is a projective test used to measure achievement motivation.

How it works:

Participants view ambiguous images (e.g., a man at a desk or a woman staring into space).

They create stories about the scenes.

The themes in their stories are analyzed to assess the strength of their achievement motivation.

People with high achievement motivation tend to focus on hard work, goal-setting, and success, while those with high affiliation motivation focus on social bonds and relationships.

Individual Differences in the Need for Achievement

The need for achievement is considered a stable personality trait that varies among individuals.

Characteristics of High Achievers:

Work harder and persist longer (Brown, 1974).

Handle negative feedback well (Fodor & Carver, 2000).

Future-oriented and willing to delay gratification for long-term goals (Mischel, 1961; Raynor & Entin, 1982).

Do High Achievers Take Big Risks?

Common Misconception: High-achievers are extreme risk-takers who choose the most challenging tasks.

Reality:

They avoid tasks that are too easy (little sense of accomplishment).

They also avoid tasks that are too hard (low probability of success).

Instead, they prefer moderately difficult tasks—ones that are challenging yet achievable (McClelland & Koestner, 1992).

Example:

Steve Nash, despite not being a top prospect, worked relentlessly to refine his skills and became NBA MVP. His high achievement motivation led him to strategically take on challenges within reach rather than impossible tasks.

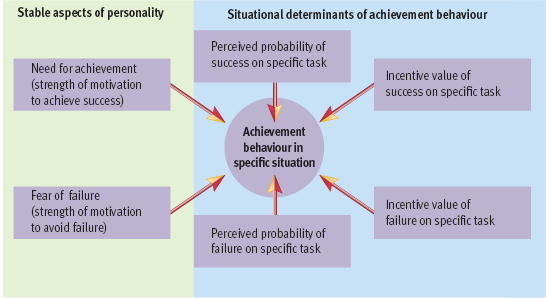

Situational Determinants of Achievement Behavior (Atkinson, 1974, 1981, 1992)

Achievement behavior is influenced by both personal traits and external factors:

Motivation to Achieve Success:

A stable aspect of personality that determines how much a person values success.

Probability of Success (Expectancy of Success):

People assess whether they are likely to succeed based on past experiences, task difficulty, and perceived skill level.

Incentive Value of Success:

The tangible (e.g., money, awards) and intangible (e.g., personal satisfaction, recognition) rewards for achieving a goal.

Higher rewards increase achievement motivation.

Example: Applying Atkinson’s Theory to Academic Success

A student’s effort in a calculus course depends on:

Personal motivation to succeed (long-term goals, ambition).

Probability of success (if the professor is known for giving difficult exams, the student may try less).

Incentive value (if the grade is crucial for their major, they will try harder).

Why High Achievers Prefer Moderate Challenges

Atkinson’s model explains why high achievers select tasks of intermediate difficulty:

Easy tasks → High probability of success, but little satisfaction.

Hard tasks → High satisfaction, but low probability of success.

Moderate tasks → Balance of challenge and likelihood of success, maximizing motivation and personal growth.

Fear of Failure & Achievement Motivation

Some people are motivated not just by success, but by a strong fear of failure (Atkinson & Birch, 1978).

Fear of failure influences:

Task selection: Avoiding difficult tasks to prevent embarrassment or disappointment.

Perceived value of failure: If failure is publicly humiliating or has severe consequences, it discourages risk-taking.

Connection Between Emotion & Motivation

Motivation and emotion interact closely in achievement behavior (Zurbriggen & Sturman, 2002).

Examples:

Motivation → Emotion: Striving to win a contest may cause anxiety during judging.

Emotion → Motivation: Anger at unfair treatment may push someone to work harder.

Components of Emotional Experience

Cognitive Component

Emotions involve subjective conscious experiences, meaning they are influenced by personal thoughts and interpretations

(e.g., feeling joy at a wedding or anger when treated rudely).

Physiological Component

Emotions trigger bodily arousal, such as increased heart rate or sweating, driven by the autonomic nervous system.

Behavioural Component

Emotions are expressed through observable behaviours, like facial expressions and body language.

Cognitive Component of Emotion

Emotions Are Subjective and Personal

Emotions are deeply personal and difficult to describe, despite being embedded in language.

People struggle to regulate emotions, as they often arise automatically and unconsciously.

Cognitive Appraisal Shapes Emotional Experience

How people interpret events influences their emotions (e.g., a speech may cause anxiety in one person but not in another).

Emotions are often evaluated as pleasant or unpleasant, but mixed emotions are common (e.g., excitement and anxiety over a promotion).

People Are Poor at Predicting Their Future Emotions (Affective Forecasting)

People misjudge how intensely and how long they will feel emotions after major life events (e.g., job loss, breakups, promotions).

This inaccuracy occurs because people overlook their ability to rationalize and adapt to setbacks.

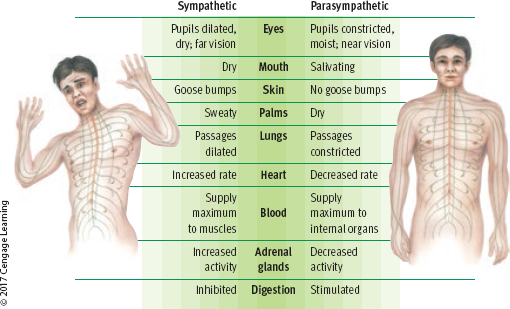

Physiological Component of Emotion

Emotional processes are linked to complex physiological mechanisms involving the brain, neurotransmitter systems, autonomic nervous system (ANS), and endocrine system.

The ANS regulates physiological responses, including the fight-or-flight reaction, controlled by adrenal hormones.

Autonomic Arousal and Emotion

Emotions trigger physiological changes (e.g., increased heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, and pupil dilation).

The galvanic skin response (GSR), which measures skin conductivity due to sweat, is often used to assess emotional arousal.

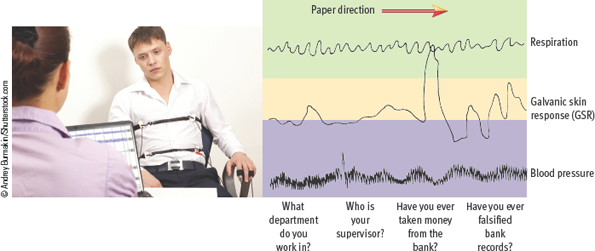

emotion and polygraph

This principle underlies polygraph (lie detector) tests, which track autonomic fluctuations to detect deception.

However, polygraphs are not reliable, as emotional arousal can occur even when someone is truthful.

There is no unique physiological marker for lying (Saxe, 1994).

Affective Neuroscience: The Brain and Emotion

The limbic system, particularly the amygdala, plays a key role in processing emotions.

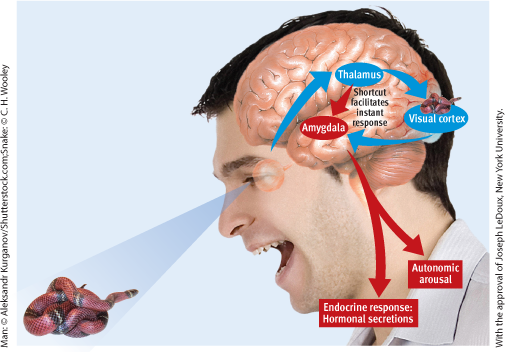

Joseph LeDoux’s model describes two pathways for processing emotional stimuli:

A fast pathway (thalamus → amygdala) for immediate reactions.

A slow pathway (thalamus → cortex → amygdala) that allows for cognitive processing.

The amygdala is crucial for fear responses and can trigger autonomic arousal before conscious awareness.

Research suggests that highly anxious children have an enlarged amygdala with increased neural connectivity.

Some theories propose that emotions arise from distributed neural networks rather than isolated brain structures.

Nonverbal Expressiveness

Emotions are expressed through body language like facial expressions, clenched fists, or slumped shoulders.

Facial Expressions: People can recognize six basic emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust) from facial expressions. Additional emotions like contempt or sympathy can be recognized but with less certainty.

These expressions are automatic and occur quickly (Tracy & Robins, 2008).

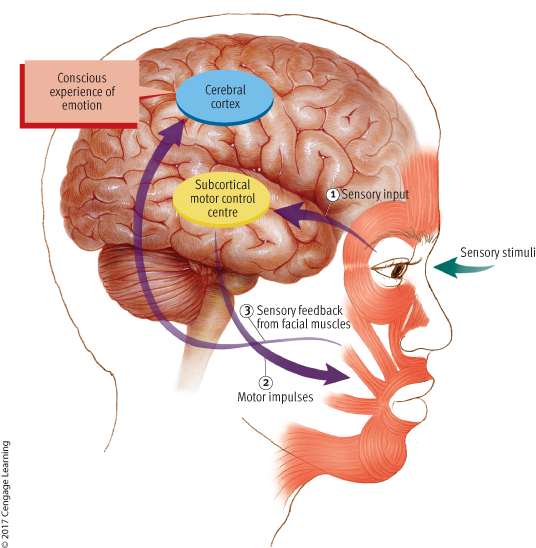

Facial-Feedback Hypothesis

Theory: The facial-feedback hypothesis suggests that facial muscles send feedback signals to the brain, which help us experience emotions.

Supporting Studies: Research shows mimicking facial expressions can lead people to feel those emotions (Dimberg & Soderkvist, 2011).

Botox Treatment for Depression: Botox, injected into the forehead to stop frowning, reduced depressive symptoms, supporting the hypothesis (Wollmer et al., 2012, 2014).

Innate Facial Expressions

Biologically Wired:

Facial expressions related to emotions appear to be innate.

Studies with blind individuals (who have never seen facial expressions) show they express emotions like sighted people (Galati et al., 1997).

Study on Athletes:

Blind and sighted athletes displayed identical facial expressions after winning or losing matches, supporting the idea that emotional expressions are hardwired (Matsumoto & Willingham, 2009).

Emotions: Universal or Culturally Variable?

Debate: Are emotions innate and universal, or are they socially learned and culture-dependent?

Both similarities and differences across cultures have been found in emotional experiences.

Cross-Cultural Similarities in Emotional Experience

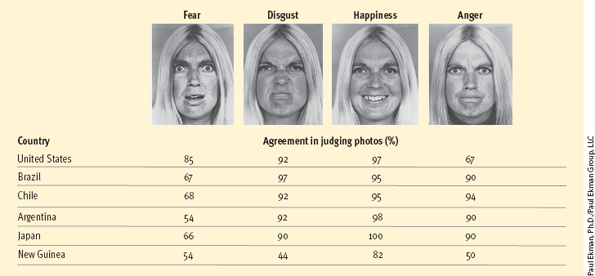

Facial Expressions:

Ekman and Friesen’s (1975) research showed that people in diverse cultures (e.g., Argentina, Japan, New Guinea) could identify six basic emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, disgust) from facial expressions.

The ability to recognize these emotions was consistent even in a remote preliterate culture (the Fore people), supporting the idea that facial expressions for basic emotions are universal.

Other Similarities:

Cognitive appraisals that lead to emotions and physiological arousal accompanying emotions show little cultural variance.

Criticisms:

Some researchers argue that Ekman’s findings may be influenced by using artificial, exaggerated facial expressions and small sample sizes, which may not capture the full range of emotional expressions.

Cross-Cultural Differences in Emotional Experience

Types of Emotions:

Japanese culture values socially engaging emotions (e.g., sympathy, guilt), and people in Japan report experiencing them more than North Americans.

North American culture encourages socially disengaging emotions (e.g., pride, anger), and people in North America report experiencing them more.

Categorization of Emotions:

Some non-Western cultures lack words for emotions like sadness, depression, or anxiety, suggesting cultural differences in emotional categorization.

Cultural Differences in Nonverbal Expression of Emotions

Display Rules:

Display rules regulate how and when emotions can be expressed, and these rules vary between cultures (e.g., Ekman, 1992).

Examples of Cultural Differences:

The Ifaluk of Micronesia restrict expressions of happiness due to cultural beliefs about duty.

Japanese culture encourages masking negative emotions (anger, sadness) with stoic expressions or polite smiles.

Joannie Rochette’s public display of grief over her mother’s death contrasts with the restrained grief of tsunami survivors in Japan, showcasing cultural differences in emotional expression.

theories of emotion

james-lange theory

cannon-bard theory

Schachter’s Two-Factor Theory

Evolutionary Theories of Emotion

James-Lange Theory of Emotion

Proposed by William James (1884) and Carl Lange (1885) independently.

asserts that the perception of autonomic (physiological) arousal leads to the conscious experience of emotion.

Contrary to Commonsense:

Commonsense suggests that emotions (e.g., fear) cause physiological responses (e.g., racing pulse).

James-Lange theory reverses this: emotions result from recognizing physiological reactions.

Physiological Determinants of Emotion:

different physical reactions (autonomic arousal) correspond to different emotions.

For example, specific patterns of bodily responses (e.g., increased heart rate, sweating) help distinguish emotions like fear, joy, and anger.

one of the first to suggest that our physiological responses directly contribute to emotional experiences

Cannon-Bard Theory of Emotion

Critique of James-Lange Theory:

Cannon pointed out that physiological arousal can occur without emotional experience (e.g., during vigorous exercise).

He argued that visceral changes (physiological responses) are too slow to precede emotions.

Cannon also noted that different emotions (fear, joy, anger) often produce similar autonomic arousal patterns.

Cannon-Bard Explanation:

Emotions occur when the thalamus sends signals simultaneously to:

The cortex (creating the conscious experience of emotion).

The autonomic nervous system (producing physiological arousal).

Modern Views:

Although the thalamus as the sole center for emotion is debated, many modern theorists agree that emotions originate in subcortical brain structures (such as the amygdala).

It is also agreed that emotions are not discerned through different patterns of autonomic activation.

This theory challenges the James-Lange model by proposing that emotion and physiological responses occur at the same time, rather than one leading to the other.

Schachter’s Two-Factor Theory of Emotion

Asserts that emotion depends on two factors:

Autonomic arousal (physical response).

Cognitive interpretation of that arousal (how you label it)

When experiencing physiological arousal, you search your environment for a reason to explain it. The situation determines how you label your emotion

Dutton and Aron (1974) Experiment

Studied the effects of autonomic arousal in a field experiment on two bridges:

A scary, swaying suspension bridge (high arousal).

A stable bridge (low arousal).

Men on the scary bridge were more likely to call a woman for a date, suggesting they misattributed their arousal (fear) as attraction due to the cognitive explanation of the situation.

Schachter’s Reconciliation

Agreed with the James-Lange theory (emotion comes from arousal) but also with the Cannon-Bard theory (different emotions have similar arousal patterns).

People differentiate emotions based on external cues, not internal arousal patterns, leading to cognitive labeling (e.g., "If I’m aroused and you're obnoxious, I must be angry").

Criticism & Limitations

While the theory is supported, it has limitations:

Situations cannot mold emotions in any way at any time.

People do not always limit their interpretation to the immediate situation (they might search for broader explanations).

Evolutionary Theories of Emotion

based on Darwin — emotions evolved for adaptive value (e.g., fear helping to avoid danger and promoting survival).

See emotions as innate reactions to specific stimuli, with minimal thought

Emotions thought to have developed before complex thought, driven by older (subcortical) brain areas.

Theories suggest that evolution has equipped humans with a small number of primary emotions that have adaptive value.

key concepts of evolutionary theories

immediately recognizable in response to stimuli, even in primitive animals that lack complex thought.

primary question for evolutionary theories: What are the fundamental emotions?

Leading theorists (e.g., S. S. Tomkins, Carroll Izard, Robert Plutchik) compiled lists, lots of overlap.

Common primary emotions identified: fear, anger, joy, disgust, surprise (appears on all three theorists' lists).

Example of adaptive value: Disgust is a disease-avoidance mechanism, helping humans avoid pathogens (e.g., sickness from dead animals).

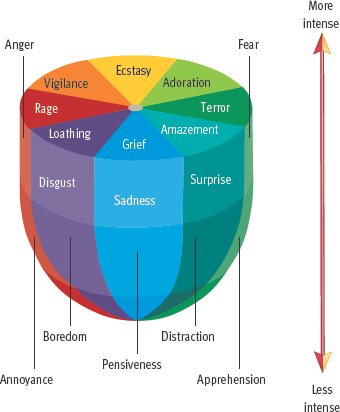

Variety of emotions in evolutionary theories

While there are many emotions, evolutionary theories explain them as:

Blends of primary emotions (e.g., fear + surprise = awe).

Variations in intensity (e.g., different levels of fear: apprehension, fear, terror).

Plutchik’s Model

Robert Plutchik proposed that primary emotions, such as fear and surprise, can blend into secondary emotions like awe.

His model also suggests that variations in emotional intensity create diverse emotional experiences.

Unifying Themes in Emotion and Motivation

Cultural Contexts: behaviors like eating preferences and emotional expression influenced both universally and culturally

Psychology and Society: psych theories/debates have significant social and political implications.

Theoretical Diversity: multiple theories of emotion, shows diversity in perspectives.

Heredity and Environment: Emotions and behaviors influenced by interplay of genetics and environmental factors.

Multiple Causes of Behavior: Psychological phenomena are typically the result of various interacting factors.

Factors That Do Not Predict Happiness

Money: Beyond a certain income threshold, additional wealth does not significantly increase happiness.

Age: Happiness remains stable over the lifespan, despite shifting life priorities.

Parenthood: People with or without children report similar levels of happiness.

Intelligence and Attractiveness: These factors are not strongly linked to overall happiness.

Moderate Predictors of Happiness

Health: Good health has a moderate impact on happiness; however, people adapt to health changes.

Social Activity: People with larger social networks or more active social lives report higher happiness.

Religion: Religious individuals tend to report higher happiness due to factors like purpose, community, and perspective on life.

Money Spent on Others: Research indicates that spending money on others leads to more happiness than spending it on oneself.

Subjective Well-Being: People generally rate themselves as fairly happy, even those with fewer resources or disabilities. Happiness is linked to better social relationships, physical health, and longevity.

strong predictors of happiness

Relationship Satisfaction

Romantic relationships, esp marriage, are strongly linked to happiness.

Married people are generally happier than singles or divorced individuals.

Relationship satisfaction, not just marital status, is key.

Work Satisfaction

significant predictor of happiness.

Unemployment negatively affects well-being.

The relationship between job satisfaction and happiness may work both ways.

Genetics and Personality

Genetics account for about 50% of happiness.

Personality traits like extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, self-esteem, and optimism also contribute.

Some people are predisposed to happiness based on their temperament.

Key Insights from Research

Subjectivity: Happiness is more about how we feel about our circumstances (health, wealth, job) than the objective reality of those factors.

Relative Comparison: People assess their happiness in relation to others, affecting wealth's link to happiness.

Hedonic Adaptation: People adapt to improvements or setbacks in life, which can limit long-term happiness increases, such as from a salary raise or a major loss.

Biological and Environmental Interaction: Both genetics and life experiences shape behavior and happiness.

Critical Thinking Application

Analyzing Arguments: An argument is built on premises that support a conclusion. A fallacy occurs when premises are irrelevant or don't properly support the conclusion. Example: “Dieting is harmful because obesity is inherited”—this links unrelated concepts.

Argument Structure: Premises support conclusions like legs support a table. Weak or irrelevant premises can make an argument unsound.

Common Fallacies: Identifying fallacies in everyday arguments can improve critical thinking and analysis.

fallacies

Irrelevant Reasons

The premise must be relevant to the conclusion.

Circular Reasoning

The premise and conclusion are essentially the same.

Slippery Slope

Argues that allowing one event will lead to worse consequences, without evidence for this chain reaction.

Weak Analogies

Draws an analogy between two things that are only superficially similar.

False Dichotomy

Presents two extreme outcomes as the only options, ignoring other possibilities.

Evaluating the Strength of Arguments

What is the conclusion?

What premises are provided to support it? Are they valid?

Does the conclusion follow logically from the premises? Are there fallacies?

What assumptions are made? Are they valid?

What counterarguments exist, and do they weaken the argument?

Is anything omitted from the argument?

rudert study: Why Acknowledgment Matters Even When Being Excluded

Selma Rudert and colleagues examined how minimal acknowledgment can reduce the negative effects of ostracism.

Method:

Participants: 595 individuals (university students & Amazon Mechanical Turk workers).

Procedure:

Used the Cyberball game (social exclusion via not receiving the ball) and an apartment-hunting game (rejection from apartment applications).

After exclusion, participants either received minimal acknowledgment (a ball throw or a message—friendly, neutral, or hostile) or no acknowledgment.

Measured participants’ sense of belongingness immediately and later.

results and conclusion of rudert study

Results:

Minimal acknowledgment improved belongingness more than no acknowledgment.

Even hostile messages (e.g., implying the participant was an awful person) improved belongingness compared to being ignored.

Conclusion & Implications:

Any acknowledgment, even negative, reduces the pain of ostracism.

Practical applications: When rejecting someone (e.g., job applicants), offering some acknowledgment—preferably positive—can lessen feelings of exclusion.

leach study: “Intuitive” Lie Detection of Children’s Deception

Amy-May Leach and colleagues examined whether police officers, customs officers, and university students could accurately detect when children were lying.

Method:

Participants: 394 adults (police officers, customs officers, university students).

Procedure:

Children were secretly videotaped alone with a toy they were told not to peek at.

Later, they were asked if they peeked, with some children completing a moral reasoning task or promising to tell the truth beforehand.

Videos of children answering were shown to the adult “lie detectives”, who rated whether each child was lying on a 7-point scale.

results and conclusion of leach study

Results:

When children were directly interviewed, adults could not accurately detect lies.

When children had thought about morality (moral task or promise), lie detection improved.

Arousal was not a reliable indicator of lying.

Conclusion & Implications:

Adults, even trained professionals, struggle to detect children’s deception.

Having children promise to tell the truth may make lying more detectable, potentially improving truthfulness judgments in the justice system.

human development

Transition & Continuity: Human development involves transitions (changes over time) and continuity (connections to past experiences).

New Challenges: As we grow, we face challenges that are often difficult, but we often receive support and reassurance from parents or caregivers. This support affects attachment and development.

Cognitive & Social-Emotional Development

Children change dramatically in how they think about themselves and the world.

Even young children show deep insights, like a 4-year-old asking, “What makes life possible?”

A child described the creative process as: “I think, and then I draw a line round my think,” illustrating that children can grasp complex ideas quickly.

Infant Abilities

Newborns are active learners, not passive. They are on a journey of discovery, learning about the world around them early on (e.g., Gopnik, 2001, 2009, 2017).

Infants show early evidence of understanding, even if they might also show misunderstandings of simple logic.

Physical Development

Physical milestones like standing, crawling, and walking are a major part of child development.

Cultural and social factors also play a key role in development, affecting children in different ways than in the past.

Social & Cultural Influences

Social changes impact development, like the shift from the traditional idea of working until 65 to the more flexible retirement age in Canada.

Life Span Development

Development spans the entire life from prenatal to old age and includes both biological and behavioral changes. The lifespan is divided into:

Prenatal period: Conception to birth

Childhood

Adolescence

Adulthood

Prenatal Development

spans from conception to birth (about 9 months).

Development is rapid, with critical changes occurring in three stages: germinal, embryonic, and fetal.

While much of this growth follows a predetermined course, environmental factors can also impact development.

3 stages of prenatal development

germinal

embryonic

fetal