Caps lecture notes- Midterm 2

1/208

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

209 Terms

composition of blood (L17)

Most of the blood is made of plasma (mostly water), then RBCs and then only a little WBCs and platelets

functions of blood (L17)

Transport and protection:

Supply oxygen to tissues (haemoglobin)

Removal of waste (e.g. carbon dioxide)

Immunological functions (e.g. WBCs)

Coagulation (stop bleeding)

Messenger functions (e.g. hormone transport)

Maintains body temp. & acid-base balance

determination of hematocrit (L17)

Hematocritt is the % of RBCs in blood

Blood volume is made up of:

Plasma 55-60% → water, proteins, nutrients, hormones etc.

Hematocrit (RBCs) 40-45%

Buffy coat (WBCs and platelets) <1%

Blood volume = plasma volume + hematocrit

~5.5L = 3L plasma (55%) + 2.5L hematocrit (45%)

functions of blood proteins (L17)

Albumin: maintenance of oncotic pressure and transport

Lipoproteins: lipid transport

Glycoproteins:

Transferrin → Fe3+ binding

Coagulation factors: hemostasis

Immunoglobulins: immunity

Complement: immunity

structure and function of red blood cells (RBCs) (L17)

Function only in peripheral blood stream

Bind O2 for delivery to tissues

In exchanged, bind CO2 for removal from tissues

They have a unique discoid shape

Maximizes SA: ~140µm2

Important for gas exchange → the shape means hemoglobin (Hb) close to more areas of the membrane

Donut appearance under light microscope

RBCs have a lifespan of ~120 days since they get damaged when going through tight spaces like capillaries

Structure

Have a cell membrane and cell cytoplasm

The RBCs are malleable (squishy) so that multiple can flow through a venule and single RBCs can flow through capillaries

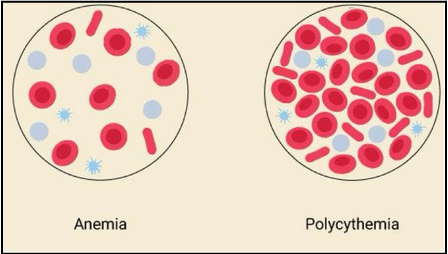

anemia and polycythemia (L17)

Anemia: reduced capacity to carry oxygen

Not always due to reduced number of RBCs

Can be caused by iron deficiency (cannot bind oxygen to heme), pernicious (B12 deficiency) or hemorrhagic

Polycythemia: too many circulating RBCs

Too viscous and can lead to blood clots and eventually strokes

how to identify the causes of anemia and polycythemia (L17)

Medical history

Physical exam

Blood tests - commonly CBC

Peripheral blood smear

Oxygen saturation

JAK2 mutation (polycythemia)

what is heme? (L17)

Heme is an iron-containing molecule

Critical component of proteins like hemoglobin

Responsible for transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide

why do we care about iron in RBCs? (L17)

Key component of hemoglobin (carries oxygen from lungs to tissues)

Iron binds to heme

Essential for bone marrow to produce new RBCs

Iron-deficiency anemia= fatigue, weakness

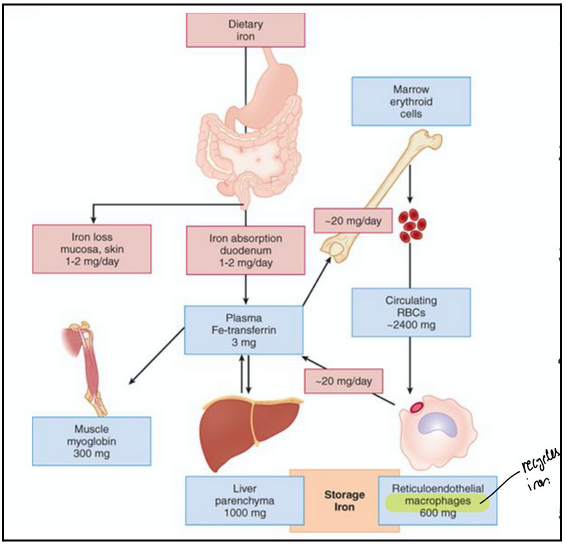

iron metabolism (L17)

Absorption: Fe2+ absorbed through intestinal mucosa (duodenum)

Oxidation: ceruplasmin (oxidative enzyme) oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+ (ferric)

Transport: Fe3+ binds to and is transported through blood by transferrin

Incorporation: in erythroblasts Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+ and incorporated into heme, which is then incorporated into Hb

Storage: ferritin binds and stores excess iron (bone marrow and liver)

High transferrin levels are likely bad since the body will keep pumping transferrin if no binding occurs

hemoglobin (Hb) synthesis (L17)

Hb synthesis occurs in bone marrow, specifically, in erythoblasts and reticulocytes

Adult Hb requires two parts:

Heme (iron-containing compound; non protein part of Hb)

Globins (proteins)

Heme synthesis starts in the mitochondria → continues in the cytosol

Globins (part of adult Hb) synthesis occurs on polyribosomes in cytosol

Hb synthesis in reticulocytes (L17)

The reticulocyte is the stage of the RBC that still has some RNA (mostly ribosomal RNA) but has extruded its nucleus. So, hemoglobin synthesis continues into the reticulocyte stage, even though the nucleus is gone.

Reticulocytes still contain residual ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

This residual rRNA allows a small amount of protein synthesis (mostly hemoglobin) to continue after the cell has left the bone marrow.

Once the reticulocyte enters the bloodstream, it gradually loses all RNA.

At this point, it becomes a fully mature RBC, which cannot synthesize any new proteins because it has no nucleus and no RNA.

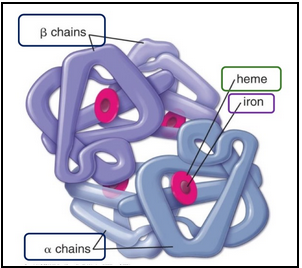

adult hemoglobin structure (L17)

It’s made of four globin chains, each bound to a heme group that contains Fe²⁺ (iron)

Most commonly 2𝛽and 2𝜶 chains → HbA

They are proteins that surround and protect heme

In adults, there are four globin types: α, β, δ, γ.

There are further A subtypes

Example: HbA1c of clinical significance

Glycosylated Hb

Meaning glucose from plasma attaches non-enzymatically to hemoglobin.

The fraction of hemoglobin that is glycated reflects the average plasma glucose over the past 2–3 months (lifespan of RBCs).

A1c < 7% is generally considered good glucose control in diabetes.

Not always an accurate measurement of diabetes

heme structure (L17)

Non-protein part (porphyrin ring)

Iron (Fe2+) inside

Iron reversibly binds O2

Transports from lungs to tissues and picks up CO2 on way back

Covalently bound to globins

In globins: iron-containing heme groups

Veins are blood due to the absorbance of light

Good to know:

CO2 doesn’t compete for Fe2+ it bidns the Hb protein chains (globins) but CO competes fiercely (binds 250x better for Fe)

Will win and cause rapid O2 starvation which is why carbon monoxide poisoning is so rapidly fatal

blood types (L17)

RBCs have different surface antigens

A+ blood is type A blood that also has Rh** surface antigen

A- blood is type A blood that does not have Rh** surface antigen

O- blood is type O blood that does not have Rh** surface antigen

Universal donor

AB+ blood is a universal acceptor

**Rh: protein on surface of RBCs → determines if a person is Rh+ or Rh-

Critical factor in blood transfusions

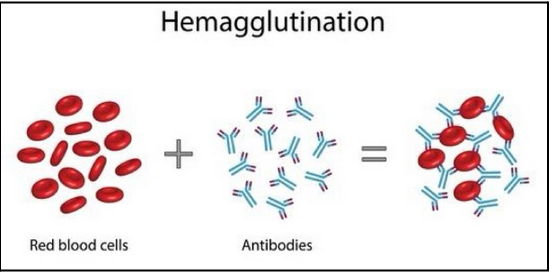

What would happen if type B- blood was given to a person with type A blood? (L17)

The recipient's anti-B antibodies will recognize the B antigens on the donor RBCs. This will cause aggutination (clumping) of the donor RBCs.

Note that the donor antibodies have little effect unless it’s a large transfusion because the antibodies get diluted.

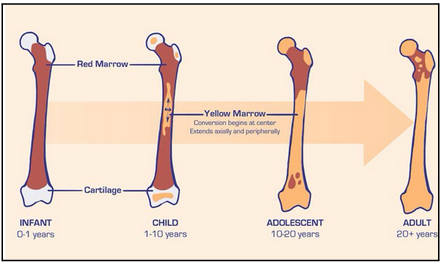

what is bone marrow? (L18)

Spongy tissue in medullary cavities of bone

Location of new blood formation

Very active tissue and has two types

red and yellow marrow

red marrow (L18)

Packed with dividing stem cells and precursors of mature blood cells

yellow marrow (L18)

Inactive bone marrow; dominated by fat cells

May be reactivated (i.e. extreme blood loss)

normal changes in location of bone marrow (L18)

In adults, only in heads of femur and humerus (long bones) and sternum, ribs, cranium, pelvis, vertebrate (flat bones)

Important to know red:yellow marrow ratio as it is and indicator of health

Typically 50:50 ratio where both exist

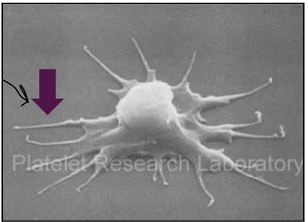

megakaryocytes and platelets (L18)

Megakaryocytes live in bone marrow

They are multi-nucleated (endomitosis without cytokinesis; up to seven duplications without cell division) and 30-150µm

Platelets are cytoplasmic fragments that break off and enter the peripheral blood stream. They function in blood clotting.

There are 1000-5000 platelets per megakayocyte

characteristics of platelets (L18)

Lifespan of around 10 days

Disc shaped with a diameter of 2-3µm

Pseudopodia allow for shape alteration and movement

No nucleus but have mitochondria, ribosomes

Granules are found in platelets:

Alpha granules: coagulation factors, adhesion molecules

Dense granules: ADP, ATP, Ca2+

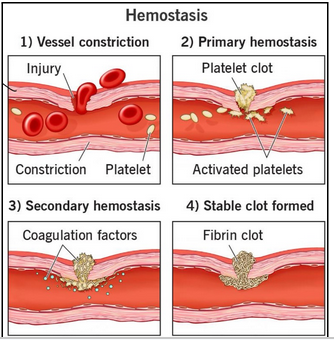

hemostasis overview (L18)

Normal hemostatic response acts to arrest bleeding following injury to vascular tissue

Four stages:

Blood vessel constricts (smooth muscle) - helps reduce immediate blood loss

Platelet clot - circulating platelets stick to damaged vessel and form a temporary platelet clot

Coagulation cascade - coagulation factors amplify clotting effects to stabilize plug

Fibrin clot - fibrin joins the party to form a solid, stable clot (during further healing, tissue replaces this)

platelet plug formation (primary wound healing) (L18)

In response to vessel wall injury, platelets adhere to the site of injury:

Von Willebrand Factor (vWF) = exposed collagen fibres in vascular wall

Activated platelets undergo conformational change (pseudopodia formation) and release alpha and dense granules → ADP and fibrinogen initiate platelet aggregation

ADP causes the release of thromboxane A2 from activated platelets → it is a potent vasoconstrictor and potentiates platelet aggregation

Results in the formation of an unstable platelet plug

Plug may be sufficient in small injuries

Plug is localized due to ADP-induced prostacyclin (released by endothelial cells; inhibits platelet activation) and NO release (inhibits adhesion, aggregation of platelets)

platelet plug formation (L18)

The overall aim of the coagulation cascade is to create a stable fibrin clot to complete the seal.

This requires thrombin production (dependent on three enzyme complexes)

Thrombin acts on fibrinogen (factor I) to promote clot formation

Important that clotting is localized which is done by a network of amplification and negative feedback loops

Extrinsic and intrinsic pathways

The intrinsic pathway is activated by factors in the blood, while the extrinsic pathway is activated by tissue factors

Both pathways cause an activation of factor X which leads to the common pathway and ends with converting fibrinogen into fibrin which forms a stable blood clot.

anticoagulation (L18)

We know clots aren’t permanent, but how do we get rid of them? → fibrinolysis

Driven by an enzyme called plasmin

Plasmin is formed from its inactive precursor plasminogen with plasminogen activators

Main two:

Tissue-tyope plasminogen activator (tPA)

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)

Once plasmin is activated it cleaves fibrin which breaks down the clot and it is cleared from the body.

disorders of hemostasis (L18)

Platelet abnormalities

Thrombocytopenia - too few platelets; bleeding, bruising, slow clotting

Thromobocytosis - too many platelets; increased blood clot risk

Hemophilia - inherited deficiency of specific clotting factors; injury can result in uncontrolled bleeding

Type A- deficiency of factor VIII

Type B - deficiency of factor IX

Von Willebrand disease

Inherited disorder of platelet adhesion (deficiencies in factor VIII and vWF)

Injury leads to increased bleeding

Latrogenic coagulopathy

Problems with bleeding or clotting caysed by medical interventions

Eg. use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet medications

what is granulopoiesis (leukopoiesis)? (L18)

Development of white blood cells in bone marrow

Neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils

Granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF)

Secreted by immune cells to stimulate production of more immune cells, especially granulocytes (and monocytes)

leukocytes (L18)

Leukocytes = white blood cells (WBCs)

Mobile units of immune system

Recognize and destroy or enutralize foreign materials

two types: granulocytes and agranulocytes

granulocytes (L18)

polymorphonuclear (PMNs) - specific granules in cytoplasm:

Neutrophils- phagocytose e.g. bacteria and fungi= first responders

Eosinophils- fight parasitic infections and mediate allergic reactions

Basophils- allergic responses (histamine), parasitic infections

agranulocytes (L18)

mononuclear- lack specific granules:

Monocytes- phagocytose viruses, bacteria, fungi → enter tissues and become macrophages (‘housekeepers’)

Lymphocytes- B and T cells= immune functions

complete blood count CBC (L18)

Leukocytes are least numerous blood cells in blood → ~ 1 WBC for every 700 RBCs

This is not because fewer WBCs are produced but because WBCs are only in transit while in the blood.

Never Let Monkeys Eat Bananas

Neutrophils

Lymphocytes

Monocytes

Eosinophils

Basophils

Neutrophils are the most abundant whereas the least is basophils in the blood

neutrophils (L18)

Granulocyte= contain granules

3-5 lobed nucleus (>5 is abnormal development)

Cytoplasm filled with pale-staining granules (hence ‘neut-’)

First defenders against bacterial infections (will be elevated on CDC if infection occurs)

Phagocytosis of bacteria, release web of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that contain bacteria killing chemicals

Thus, they can kill intracellularly (phagocytosis) and extracellularly (NETs)

Act as scavengers to clean up debris, e.g. old RBCs, damaged tissue

eosinophils (L18)

Granulocyte = contains granules

Bi-lobed nucleus

Cytoplasm filled with pink-staining granules (hence ‘eosino-’)

First defenders against parasites (e.g. worms)

basophils (L18)

Granulocyte = contain granules

Bi-lobed nucleus

Nucleus obscured by the density of overlying granules

Cyotplasm filled with blue-purplish-staining granules (hence ‘baso-’)

Lowest cell count in CBCs often read as zero

Involved in allergic responses (contain heparin and histamine) and bacteria, fungi and viruses

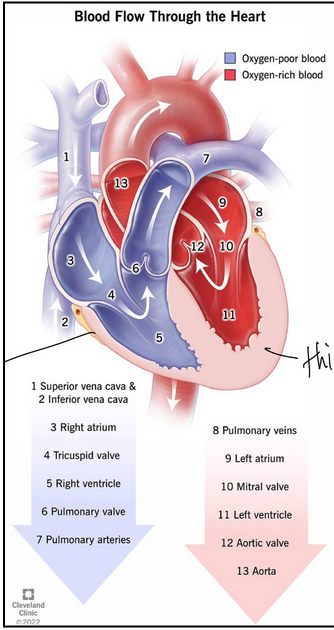

flow of blood through the heart (L19)

Deoxygenated blood returns from body via superior and inferior vena cavae

Enters the right atrium

The right atrium contracts and pushes blood through tricuspid valve

Enters the right ventricle

The right ventricle contracts pushes blood through pulmonary valve into lungs

In lungs blood picks up O2 and releases CO2

O2 rich blood returns through pulmonary veins

Enters the left atrium

The left atrium contracts and pushes blood through mitral valve

Enters the left ventricle

The left ventricle contracts pushes blood through aortic valve

Enters the aorta and can go back to the body

atrio-ventricular valves (L19)

The tricupsid and mitral (bicuspid) valves

Located between the atria and ventricles

Tricuspid

Between right atrium and right ventricle

Three cusps (anterior, septal and posterior)

At the base of each cusp anchored (chordae tendineae) to fibrous ring that surrounds orifice

Mitral (bicuspid)

Between left atrium and left ventricle

Regulates the blood flow between them

Two leaflets: anterior (aortic) and posterior (mural)

They are supported by two structures → chordae tendinae and papillary muscles

semilunar valves (L19)

Pulmonary and aortic valves

Located between ventricles and their corresponding artery

Regulate blood flow of blood leaving the heart

Pulmonary valve

Between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery

Three leaflets (anterior, left and right)

Attached to a touch, fibrous ring called annulus

Main function: allow blood flow from right ventricles to pulmonary artery and prevent backflow into right ventricle

The leaflets overlap to ensure complete closure and prevent backflow of blood into the right ventricle

papillary muscles (L19)

Small, cone-shaped muscles in ventricle

Play crucial role in valve function: contract during systole (prevents AV valves from collapsing into atria, ensure one-way flow and prevent regurgitation)

chordae tendinae (L19)

Functions with papillary muscles to prevent blood backflow

Connect the papillary muscles to AV valve leaflets

Prevents valve leaflets from being pushed back into the atria

what is the cardiac cycle? (L19)

The cardiac cycle is the complete sequence of physiological events that occur in the heart, from one heartbeat to the next

Systole = phase of chamber contraction

Diastole = phase of chamber relaxation and filling

The atria contract

The ventricles contract (AV valve closes, semilunar valve opens, blood ejected into great vessels)

Atria relax

Ventricles relax (semilunar valve closes, AV valve opens)

Note: valve are one-way = when they open, blood flows out/ when they are closed, no blood leaks back

Note: we usually associate systole with ventricular systole - period of ventricular contraction which is time between AV valve closure and semilunar valve closure

“Lub Dub” heart sounds (L19)

This sound is caused by the closing of heart valves during each cardiac cycle

Lub= also known as S1 produced by closing of AV valves (mitral and tricuspid)

Dub= also known as S2 produced by closing aortic and pulmonary valves as blood ejected from ventricles

Abnormal heart sounds occur as a result of abnormal valve movements or abnormal cardiac movements. Can also occur in healthy people.

Physiological splitting of S2:

Normal separation of the second heart sound into two components

Aortic valve closure and pulmonary valve closure are not synchronized during inspiration

Aortic valve closes slightly before pulmonic and this splits S2 into two distinct components

heart murmurs (L19)

A sound heard as a result of turbulent flow in the heart

Aortic stenosis

Normal flow across a narrowed valve

Mitral regurgitation

Across a valve which doesn’t close properly (backflow)

Ventricular septal defect

Through a hole, from a high pressure chamber to low pressure chamber

three tunics of blood vessels (L20)

Tunica intima (innermost)

Endothelium, basement membrane, connective tissue

Tunica media (most variable layer- related to functions)

Smooth muscle, elastic fibres, connective tissue

Tunica adventitia

Loose connective tissue, blood vessels, nerves

Lumens of all vessels are lined by endothelial cells but capillaries are only composed of the endothelial layer and its basement membrane — they lack the media and adventitia. Why? (L20)

to allow for easier gas exchange

thickness of arteries and veins (L20)

There is a progressive thinning of vessel walls from artery → arteriole → capillary (where gas exchange occurs), then gradual thickening again from venule → vein as blood returns to the heart.

three arteries (L20)

Large (elastic) arteries

Aorta, pulmonary arteries

Convey blood from heart to systemic circulation

High pressure vessels

Med (muscular) arteries

Most arteries

Distributing vessels

Arterioles

Start of microcirculatory bed

Resistance vessels

Arterioles still have smooth muscle in their tunica media, unlike capillaries.

That smooth muscle lets arterioles constrict or dilate, controlling:

Blood flow into capillary beds

Blood pressure (they are called the “resistance vessels” of the circulation)

three veins (L20)

Large veins eg. vena cava, femoral

Med veins: most veins (contain 70% of blood); run with arteries

Venules: receive blood from capillaries

Travel with arterioles

Venule lumens less regular in shape

Capacitance vessels (volume storage)

capillaries (L20)

Wall is one endothelial cell thick

Designed for easy and rapid exchanges between blood and tissues

Pericytes wrap around endothelial cells:

Regulate blood flow

Phagocytes

Permeability of BBB

three types of capillaries (L20)

Continuous:

Endothelial cells form a continuous, unbroken lining (tight junctions between cells)

Small gaps only at intercellular clefts where small molecules can pass

Surrounded by a complete basement membrane

Allow limited exchange — mainly small molecules like water, ions, and gases (O₂, CO₂)

Prevent loss of plasma proteins and blood cells

Found in tissues that require a tight barrier: Muscle, skin, lungsand central nervous system (CNS) → forms part of the blood-brain barrier

Fenestrated:

Endothelial cells have fenestrations (pores) in their plasma membranes.

Pores may have thin diaphragms covering them.

The basement membrane is still continuous.

Allow more rapid exchange of water and small solutes (like glucose, hormones, ions).

Still retain large proteins and cells due to intact basement membrane.

Found in tissues with high exchange or filtration: Kidneys, small intestine (villi), endocrine glands and ciliary body of eye

Sinusoid

Have an incomplete basement membrane and intercellular gap

vascular endothelium (L20)

Simple squamous epithelial cells (called epithelial cells)

Crucial for vascular functions and homeostasis

Forms a thin, continuous inner lining of all blood vessels — arteries, veins, and capillaries (~60,000 miles total in the body!).

Rests on a basement membrane.

Serves as a selective barrier and an active regulator of blood flow, clotting, and vessel health — essential for maintaining vascular homeostasis

how do veins pump blood against gravity? (L20)

Through valves

Through surrounding skeletal muscles contraction

Through tons of smooth muscle (media and adeventitia)

neural control of arteriolar diameter (L20)

SNS:

Noradrenaline- vasoconstriction- through alpha-adrenergic receptor stimulation - increases vascular resistance

Adrenaline- vasoconstriction - how is not known

PNS: insignificant

hormonal control of arteriolar diameter (L20)

Hormones (released from endocrine glands) can cause vasoconstriction and vasodialation by interacting with receptors on smooth muscle cells lining arteriolar walls

Constrictors: angiotensin II, arginine vasopressin (AVP)

Dilator: atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP)

tissue metabolites of arteriolar diameter (L20)

Produced by active tissues (e.g. increased activity during exercise) - act as vasodilators

E.g. adenosine- potent vasodilator, CO2- vasodilation, lactate (by-product of anaerobic metabolism)- vasodilation, oxygen- affects release of vasoactive substances

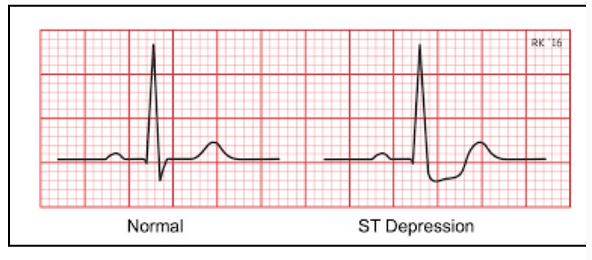

angina (chest pain) (L20)

Angina occurs when ischemia (decreased oxygen) in the heart activates afferent pain pathways, sending signals to the brain that are perceived as chest pain. If blood flow is not restored, this can progress to a heart attack (myocardial infarction).

ECG will show ST depression

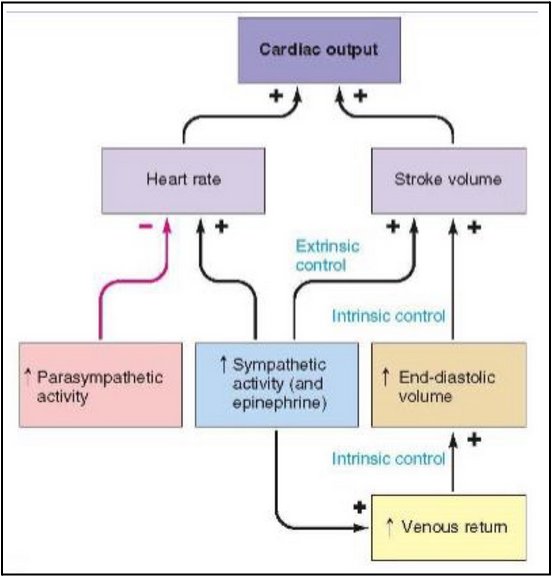

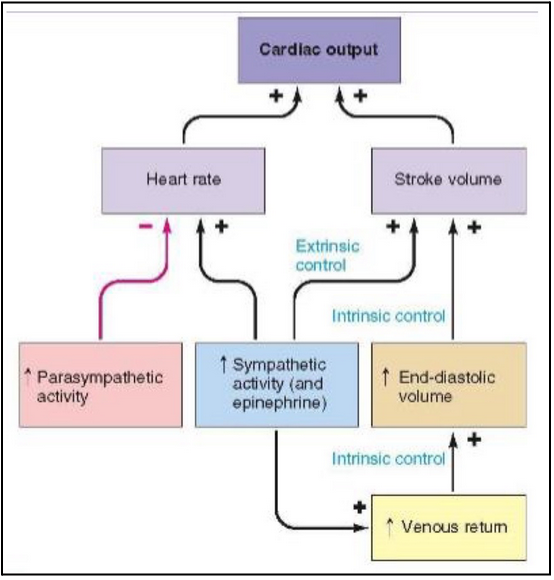

cardiac output (L21)

Cardiac output= the volume of blood ejected from the heart every minute (units: mL/min)

Heart rate= number of heart beats per minute

Stroke volume= volume of blood ejected from left ventricle with each sytosolic contraction

CO= heart rate (HR) x stroke volume (SV)

regulation of cardiac output (parasympathetic) (L21)

Increased parasympathetic activity

Negative feedback on heart rate and positive feedback on CO

HR decreases (slower heartbeat)

Filling time increases → more blood fills the ventricles between beats

Stroke volume (SV) can increase due to the Frank–Starling mechanism (the heart pumps what it receives — more filling = stronger contraction)

regulation of cardiac output (sympathetic) (L21)

Increased sympathetic activity

Epinephrine

Positive feedback on HR, SV, venous control

Increased end diastolic volume

Positive feedback on stroke volume

Positive feedback on CO

regulation of cardiac output (stroke volume) (L21)

Sympathetic nerves (releasing NE)

Acting on 𝛽1 receptors on cardiac muscle cells → increased intracellular calcium and increased stroke volume

In ventricle this means increased calcium entry into the myocytes from outside cell and calcium release from intracellular stores → promote contraction of ventricle

Frank Starling law of the heart (L21)

States that the strength of contraction is related to initial length of cardiac muscle fibres

The more stretched the muscle is initially, the stronger the contraction

So what? Why is this important for the heart?

The initial length of the heart muscle before contraction is equivalent to how filled the heart is at the end of diastole, or the end of the diastolic volume

The strength of contraction is equivalent to the stroke volume during systole

Bottom line: if you increase ventricular end diastolic volume (or preload) you increase the stroke volume (within reason, the heart will pump what it receives)

pressure and resistance (L21)

CO= cardiac output

Blood pressure= CO x resistanceCO= volume in vessels

Resistance = diameter of vessels (systemic vascular resistance or SVR)

So, what determines SVR?

Resistance is determined by the radius of the blood vessels

Resistance = 1/r4

Inversely proportional to the fourth power of the vessel’s radius

This means a small change in radius has a significant impact on resistance, because it is raised to the fourth power

E.g. if a blood vessels constricts to half of its original radius, the resistance to flow will increase 16 times

what causes vasoconstriction (ie. increased SVR)? (L21)

Exposure to cold

Stress

Certain medications (e.g. decongestants, migraine medications, stimulants)

Raynaud’s phenomenon: spasms in response to cold, stress, emotional upset

Smoking, coffee, salty foods

what causes vasodilation (ie. decreased SVR)? (L21)

Exercise (muscles require more oxygen and nutrients, vasodilation increases blood flow)

Low oxygen levels (hypoxia)

Increased body temp. (helps release heat through skin, aiding in cooling)

Inflammation: deliver more oxygen and nutrients

vasoactive hormones (L21)

Constrictors:

Angiotensin II

Arginine vasopressin

Dilator:

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP)

afterload (L21)

The pressure the ventricle must generate in order to eject cardiac output

Primarily determined by resistance in arteries

Chronic high arterial BP is an example of high afterload

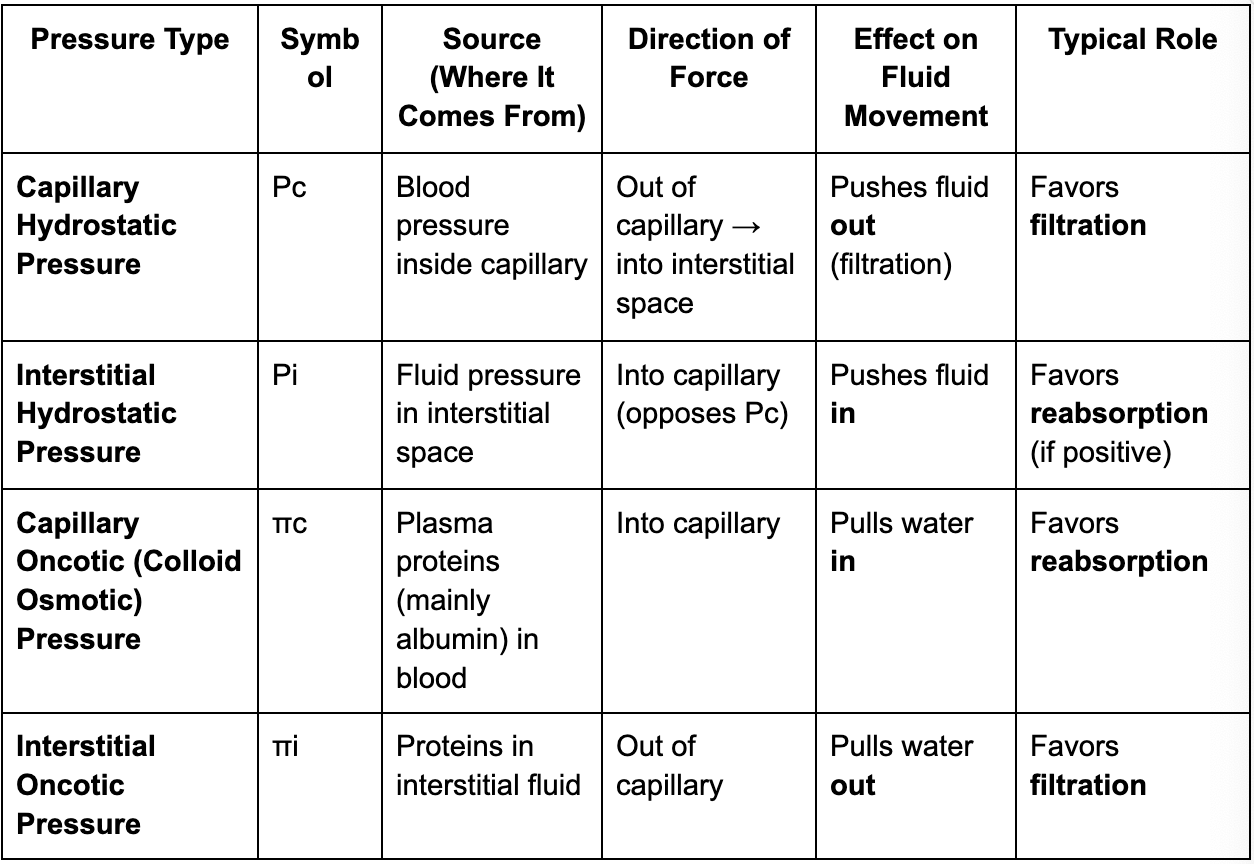

capillary hydrostatic pressure (L21)

pressure exerted by blood within a capillary, driving fluid out of the vessel and into surrounding tissues

capillary oncotic pressure (L21)

pressure exerted by proteins in the blood plasma that draws water from the interstitial space back into capillaries —> opposes hydrostatic pressure

no net movement (L21)

state where no overall movement of fluid, solutes across capillary wall, either in or out of the blood. Typically occurs when driving forces are balanced or opposed → equilibrium.

net filtration (L21)

process where fluid is pushed out of capillaries into surrounding tissues. Occurs due to differences between hydrostatic pressure (pressure of fluid w/in capillary) & osmotic pressure (pressure exerted by proteins in blood). Occurs when capillary hydrostatic pressure> blood colloid osmotic pressure. In most capillaries, more fluid is filtered out than is reabsorbed, leading to a net filtration

interstitial oncotic pressure (L21)

Interstitial oncotic pressure is the osmotic pressure created by proteins in the interstitial fluid (the fluid surrounding cells in tissues).

pulls water out of capillaries and into the interstitial fluid.

net reabsorption (L21)

overall movement of fluid from interstitial space back into capillaries. Driven by difference in osmotic and hydrostatic pressures, with osmostic pressure favouring the movement of fluid back into capillaries due to higher [protein] in blood.

table comparison of pressure types (L21)

Starling forces adjustment after hemorrhage (L21)

Overall goal: Restore intravascular (blood) volume after blood loss.

Fluid moves from interstitial space → into capillaries (net reabsorption).

After hemorrahage Starling forces shift to favour the movement of fluid from the interstitial space into the capillaries to restore blood volume

Initial and most significant change is a sharp drop in capillary hydrostatic pressure, which reduces the force of pushing fluid out of the capillaries

Hemorrhage → ↓ blood volume → ↓ capillary blood pressure.

This reduces the outward filtration force that normally pushes fluid out.

Result: Less filtration / more reabsorption into capillaries.

Followed by a slower, but critical process where proteins move from the interstitium back into the plasma, increasing capillary oncotic pressure and further promoting fluid reabsoprtion.

As plasma volume falls, plasma proteins become more concentrated.

Over time, proteins also move from interstitial fluid → plasma, further raising capillary oncotic pressure.

This increases the inward osmotic pull, enhancing reabsorption of interstitial fluid.

blood pressure (L22)

Blood pressure (BP)= pressure inside blood vessels or heart chambers relative to atmospheric pressureHow does your brain know what your BP is and what does it do about it?

How does your brain know what your BP is and what does it do about it? (L22)

Afferent nerves in medulla receive messages from baroreceptors (BP sensors) and send message back through efferent vessels to blood pressure controllers (baroreceptors)

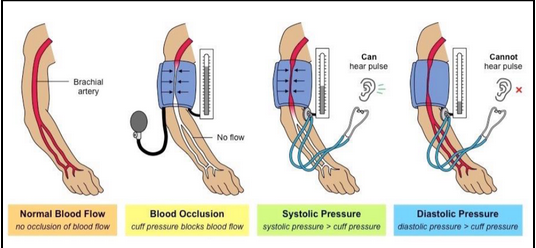

BP cuff (L22)

Inflate cuff around upper arm to stop blood flow, then slowly release air while listening for blood flow sounds through brachial artery

Systolic pressure recorded first when first sound heard, then diastolic pressure recorded when sound disappears

What and where are baroreceptors? (L22)

Stretch sensitive nerve endings that detect BP

Increased BP means increased nerve impulses from baroreceptors, which tells brain to lower BP by slowing heart rate and dilating blood vessels

carotid sinus and aortic arch (L22)

Carotid sinus: in common carotid artery

(afferent nerve= glossopharyngeal nerve)

Aortic arch: in arch of aorta

(afferent nerve= vagus nerve)

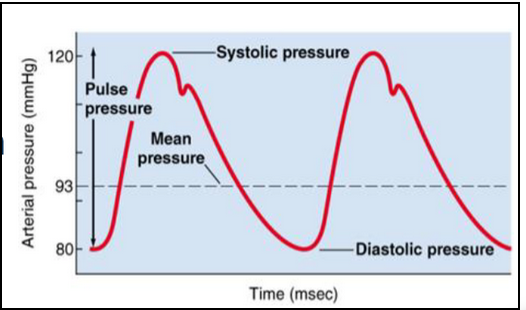

mean arterial pressure (MAP) (L22)

MAP related to systolic and diastolic pressures through a formula

MAP= DBP +⅓ (SBP-DBP)

Common way is to add diastolic to one-third of pulse pressure (= difference between diastolic and systolic)

Why care?

MAP represents average pressure in person’s arteries, indicating overall blood circulation and organ perfusion

High MAP: increased risk of cardiovascular disease

Low MAP: not enough oxygen to organs= shock, organ damage

Restoring BP after acute rise in arterial pressure (L22)

What can cause this? → stroke or hypertensive emergencies

BP≥180/120 → can lead to stroke, heart attack, kidney failure

Needs rapid interventions

IV anti-hypertensive medications that aim to reduce BP slowly (if not done slowly → headache, chest pain, shortness of breath, confusion)

Restoring BP after acute fall in arterial pressure (L22)

Can be caused by hemorrhage, heart failure, cardiac event

Treatment depends on cause:

If hemorrhage then stop bleeding and restore blood volume with fluid resuscitation and potentially blood transfusion

If heart failure or cardiac event, focus on optimizing cardiac output with medications like vasopressors to increase BP

why do we breathe? (L23)

Gas exchange

Route for water loss and heat elimination

Acid-base balance (altering amount of H+)

Speech, singing and smell

Defends against inhaled foreign matter (alveolar macrophages)

conducting structures (L23)

Nasal cavity

Nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx

Trachea

Bronchi

Bronchioles

These all function to warm and humidify air and to remove foreign particles

respiratory structures (L23)

Respiratory bronchioles

Pulmonary alveoli

Alveolar ducts

Alveolar sacs

Alveoli

These all function in gas exchange

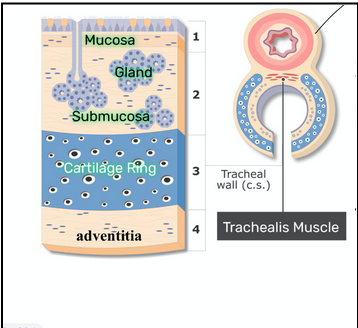

common micro-anatomical plan lungs (L23)

Mucosa: respiratory epithelium, basement membrane

Submucosa: loose connective tissue containing seromucous glands

Adventitia: outer connective tissue layer, binds airways to adjacent structures (so lungs aren’t floating freely)

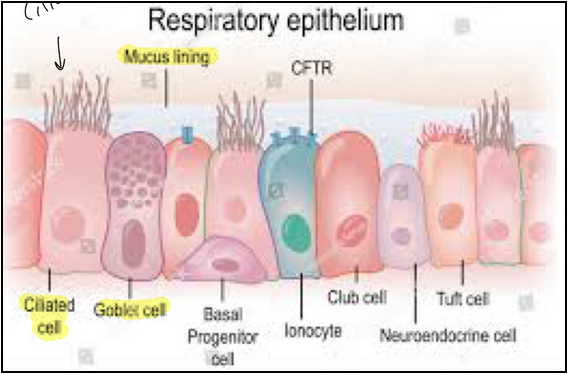

respiratory epithelium (L23)

Functions in protection (pathogens), mucociliary clearance, humidity and warming, gas exchange and immune defense

airway lining fluid (L23)

Composed of two layers

Mucus layer: gel-like substance, 97% water, 3% solid

Pericilliary layer: low viscous fluid

Catch foreign debris

Note: mucus is produced by both goblet cells and seromucous glands

Muco-ciliary escalator (L23)

Cilia provide coordinated sweeping motion that moves mucus and entrapped foreign materials to the larynx for expulsion

Tracheobronchial tree (L23)

Trachea splits into two bronchi

Airway further divides around 23 times finally reaching 150-250 million alveoli in each lung

Trachea (L23)

Contains

Mucosa: respiratory epithelium

Submucosa: seromucous glands

Cartilage: 16-20 rings, maintains patency of tube (prevents collapse)

Adventitia: loose connective tissue

Note: the cartilage is not continuous so that the trachealis muscle can stretch and allow for swallowing

main bronchi (L23)

Contains

Mucosa: respiratory epithelium

Submucosa: seromucous glands

Cartilage: 16-20 rings, maintains patency of tube (prevents collapse)

Adventitia: loose connective tissue

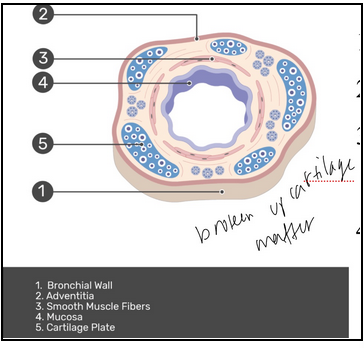

intrapulmonary bronchi (L23)

Lots of branching

As they become smaller:

Decreased cartilage

Epithelial height reduced (need only one cell layer for easy gas exchange)

Smooth muscle becomes prominent

bronchioles (L23)

Very small conducting airways

No cartilage

No submucosal glands

Epithelial lining transitions:

Respiratory → simple columnar → simple cuboidal

Goblet cells replaced by club cells

club cells (L23)

Dome-shaped

Make up 80% of cells lining bronchioles

Lung protective functions:

Surfactant (reduce surface tension)

Respiratory distress syndrome in babies born without because lungs not developed enough

Treated with surfactant replacement

Inflammation control

Enzymes to break down mucus

Antimicrobial lysozymes

respiratory bronchioles (L23)

Transition point in respiratory system

From air conduction to gas exchange

Initial segments are ciliated cuboidal

Club cells persist in initial segments and become dominant in distal segments

Epithelial height is reduced

turbinates (L23)

Also known as nasal conchae

Tiny structures in the nose (bony projections)

Help regulate airflow and roles in warming, humidifying and filtering air

pulmonary alveoli (L23)

These are the terminal air spaces

Primary site for gas exchange

Air brought into very close proximity to blood

Structure:

Septae

Network of capillaries

Alveolar macrophages

Type 1 pneumocytes:

Squamous cells

Large SA for gas exchange

Cover 95% of alveolar surface

Type 2 pneumocytes:

Cuboidal cells

More numerous but only cover 5% of SA

Secrete surfactant

blood air barrier (L23)

Minimal thickness

Type 1 pneumocytes: thin

Capillary endothelium: thin

Allows for rapid gas exchange

Diffusion of oxygen from alveoli to capillaries and diffusion of carbon dioxide out of capillaries to alveoli. Across the epithelium

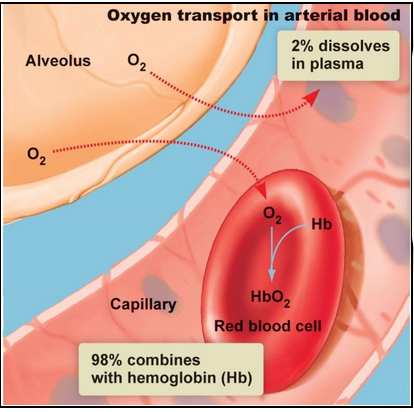

Oxygen transport in the blood (L23)

Hemoglobin (protein) contains iron which readily binds to oxygen

When this occurs it is called oxyhemoglobin

Hemoglobin allows for vast majority (98%) of oxygen to be transported (faster than if it was dissolved in plasma)

Hemoglobin facilitates oxygen transport

Hemoglobin binds with oxygen in lungs

Has 4 binding sites

Oxygen binds and becomes oxyhemoglobin

The partial pressure difference (higher in alveoli compared to blood) drives oxygen from the alveoli to blood