Looks like no one added any tags here yet for you.

What do humans use for fuel/energy to move?

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

Where does ATP come from?

macronutrients in the diet and is broken down into Carbohydrates (CHO), Fats and Proteins (PRO)

what does CHO and PRO as fuel yield?

4kcal per gram

Fats as fuel yield?

9kcal per gram

Fuel Choices for Energy Production - Carbohydrates

absorbed as glucose primarily, also fructose and galactose

Fuel Choices for Energy Production - Fats

absorbed as fatty acids, triglycerides and cholesterol

Fuel Choices for Energy Production - Proteins

absorbed as amino acids plus some small peptides

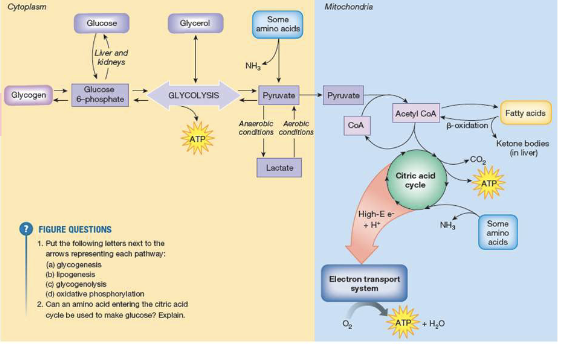

Carbohydrates - Anaerobically

CHO in the form of glucose goes through Glycolysis = 2 ATP and Pyruvic Acid. If initial fuel is glycogen = 3ATP.

Not much energy but very fast

Carbohydrates - Aerobically

Pyruvic acid from anaerobic metabolism enters Kreb’s cycle = 2ATP with leftover Hydrogen ions (H+). H+ enters Electron Transport Chain = 30-32 ATP

Fats - aerobically

Stored energy that is released/produced Aerobically.

Produce greater amount of energy that CHO or Proteins, however it takes longer

Fat breakdown can only continue in the presence of oxoacetic acid that comes from CHO metabolism

Proteins

Vital building ingredient for many cells in our body

Important fuel for Endurance activities (greater than 90)minutes

Proteins go through deamination (removal of an amine group from the amino acid) and transamination (removal of nitrogen) processes

and leave carbon skeletons

Gluconeogenesis is glucose synthesis from these skeletons – your body can now use the protein for energy

Summary for Energy Production

Overview of Muscle Metabolism

Exercise begins with muscle contraction – this requires ATP for energy

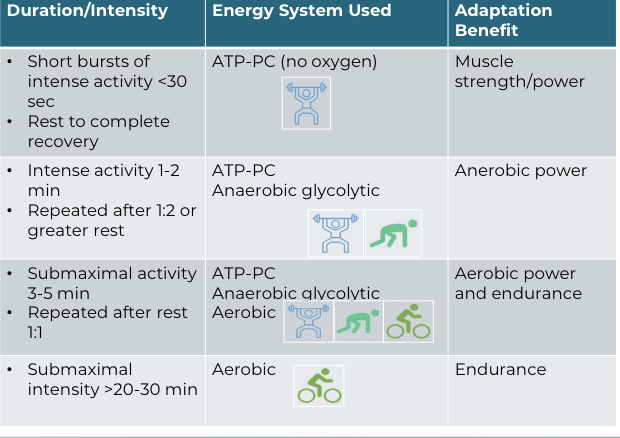

Metabolic Pathways - Phosphagen, or ATP-PC

Short, quick bursts

Fist 30 seconds of intense exercise

Metabolic Pathways - Anaerobic Glycolytic

Moderate intensity or short duration

30-90 sec of exercise

Metabolic Pathways - Aerobic

Predominates after 2 min of exercise

Metabolic Pathways - overview

Aerobic vs Anaerobic Metabolism

Anaerobic metabolism

fast, not efficient

yields only 2 ATP

Aerobic metabolism

slower, more efficient

yields 30-32 ATP

requires adequate O2

Aerobic metabolism

Carbohydrates are converted to ATP through glycolysis/citric acid cycle/ETS pathways (provides 30-32 ATP per glucose)

Fatty acids are processed through a pathway called beta oxidation – the number of ATP produced are determined by the length of the fatty acid

Anaerobic Metabolism

When there is insufficient oxygen, glucose is converted to lactate (referred to as glycolytic metabolism/glycolysis) (provides 2 ATP per

glucose).

When metabolic byproducts accumulate in the muscle, it inhibits glycogen breakdown and has a negative effect on muscle contraction

Substrate Use During Exercise

Lower levels of exercise (< 70% oxygen consumption)

uses 60% fats for energy

uses 40% glucose for energy

Higher levels of exercise (> 70% oxygen consumption)

uses carbohydrates –glucose

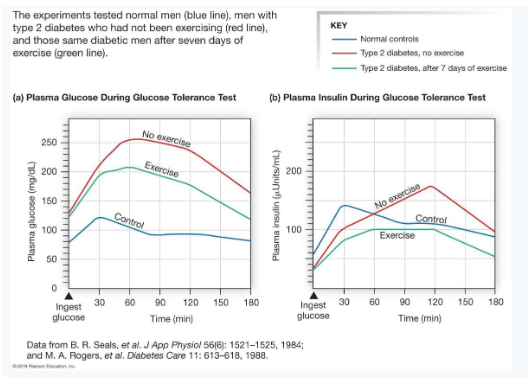

Hormones regulate metabolism during exercise

Insulin secretion is suppressed during exercise.

Muscle does not use insulin for glucose uptake

Muscles use GLUT4 transporters for glucose uptake

Fuel Choices for Energy Systems

What you are doing determines which energy system is being used

The availability of oxygen determines how ATP will be used

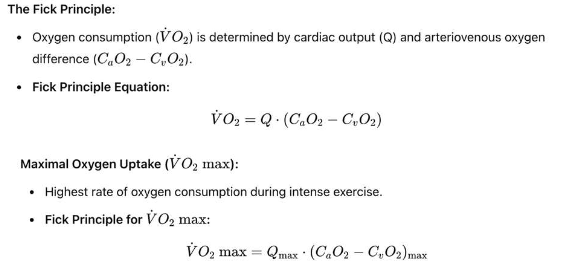

VO2 max is the maximum volume of O2 able to be taken in, transported and utilized

Oxygen Consumption

Oxygen consumption is the rate of oxygen used by the body and is used to quantify exercise intensity.

Resting oxygen consumption is approximately 3.5 ml/kg/min.

Maximal oxygen consumption is the amount of oxygen consumed by an individual at maximal exercise, and is used as a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness

VO2max is the product of?

maximal cardiac output and a-vO2 difference

Maximum Oxygen Consumption (VO2 max)

Measure of body’s capacity to use oxygen

Maximum rate of oxygen consumption attainable during physical exertion

Expressed relative to bodyweight

mL/kg per minute

Maximal rate of oxygen consumption equations:

VO2 METs

VO2 can be measured in ml/kg/min (adjusted for differences in body weight), L/min, or METS.

One MET (metabolic equivalent) is the oxygen consumption at rest.

2 METs means that a person is consuming oxygen at twice the resting rate (7 ml/kg/min).

3 METs means that a person is consuming oxygen at three times the resting rate (10.5 ml/kg/min

VO2max is measured using?

open circuit spirometry. The individual performs a graded exercise test to exhaustion with ventilation and expired O2 and CO2 measured.

Estimating V˙O2\dot{V}O_2V˙O2 max using field tests is a practical approach for assessing aerobic fitness without specialized equipment. Some common field tests include:

Cooper Walk/Run Test

Run or walk as far as possible in 12 minutes.

1.5 Mile Run Test

Run 1.5 miles as quickly as possible.

Step Test

Step up and down on a platform for 3 minutes.

Rockport Walk Test

Walk one mile as quickly as possible

Components of Physical Function Related to Human Movement: Definition of Key Terms

• Balance

• Cardiopulmonary endurance

• Coordination

• Flexibility

• Mobility

• Muscle Performance

• Neuromuscular Control

• Postural control, postural stability, and equilibrium

• Stability

What is therapeutic exercise?

The systematic performance or execution of planned physical movements of activities intended to enable the patient or client to:

1. Remediate or prevent impairments of body structures or functions

2. Enhance activities or participation

3. Prevent or reduce health-related risk factors

4. Optimize overall health status, fitness or sense of well-being

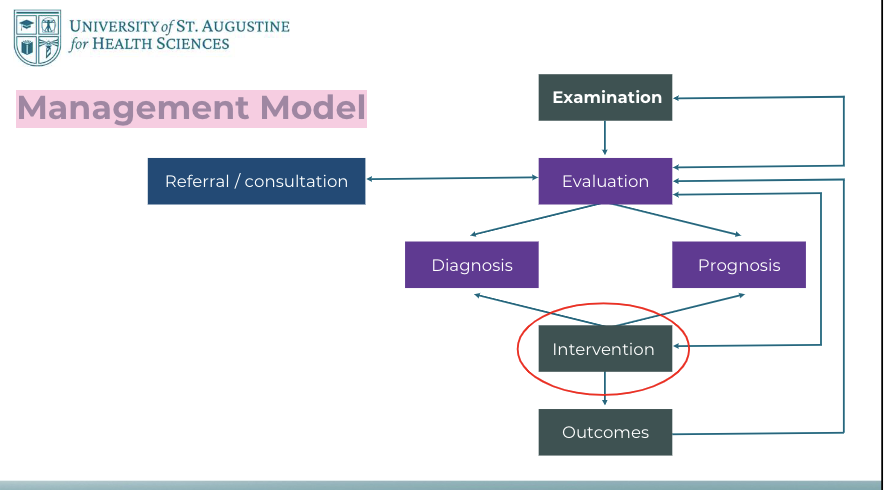

Management Model

Therapeutic Exercise Interventions

• Aerobic capacity/endurance conditioning or reconditioning

• Flexibility exercises

• Strength, power, and endurance training

• Balance training

• Neuromotor development training

• Gait and locomotion training

• Relaxation

• Posture training

• Graded motor imagery

Role of Physical Therapists

Simply addressing impairments does not guarantee improvements in performance or quality of life

Importance of Task-Specific Exercises

To enhance a patient’s performance in activities and participation in life roles, as well as to improve health-related quality of life, interventions should include exercises that are specific to the tasks the patient aims to perform

How do we prescribe therapeutic exercise?

ICF Framework FITT-VP Considering contextual factors

Using principles of science (physiology and biomechanics)

Using best evidence from research

ICF framework

1. Patient’s goals → participation restrictions

2. Activity limitations

3. Body structure/function impairments

4. Contextual factors → Environmental and Personal, Barriers and Facilitators

ICF Definitions

Health Condition- the disorder or disease state

Participation Restrictions - the inability of the individual to engage in expected life situations (e.g. work, social role, play, chores, recreation)

Activity Limitations - the inability to perform certain tasks, functions that lead to participation restrictions (e.g., cannot sit at a desk; cannot hold a tennis racket; cannot ascend a flight of stairs at home)

Body Structures and Functions - anatomic and physiologic (including psychological) impairments that limit function

Contextual Factors - Environmental and Personal Factors (e.g., physical, social, and attitudinal) influencing a person’s life

Activity Limitation and Participation Restriction

Correlation Between Body Function and Activity Limitations:

Decreased isometric strength in lower extremities correlates with difficulties in stooping and kneeling.

Reduced peak power in lower extremities is linked to slower walking speeds and challenges moving from sitting to standing.

Variability in Impact of Impairments:

Not all impairments consistently lead to activity limitations.

Increased joint space narrowing in osteoarthritis patients did not consistently correlate with increased activity limitations in a 2-year study.

Critical Threshold of Impairments:

Severity and complexity of impairments must reach a critical, person-specific level to significantly impact functioning.

ICF Construct Relevance:

Findings support the ICF framework, highlighting that environmental and personal factors interact with all aspects of functioning and disability

Individual responses to health conditions are unique and influenced by various factors

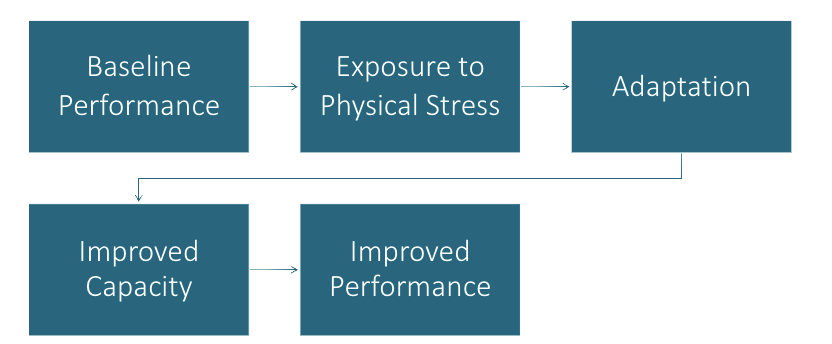

Purpose of Exercise Training

The purpose of performing regular exercise is to achieve a positive adaptation in physical function. Each exercise we prescribe is linked to a specific goal

Principles of Exercise Training

Exercise Training Principles

Components of an exercise prescription

Examples of training adaptation

Exercise Training Principles

Overload

Specificity/ Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID)

Reversibility

Individual differences

Overload

the stress to the body during an exercise challenge must be greater that the stress encountered in daily activities; this applies to both aerobic and resistance exercise

SAID (Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands):

A framework of specificity is a necessary foundation on which exercise programs should be built.

the adaptive effects of training are specific to the mode of exercise used in training; if the client’s goal is to be able to climb stairs, then the training should involve ascending and descending stairs

Specificity of Training - adaptive effects of training are highly specific to the training method employed (strength v power v endurance)

Reversibility Principle; “Use it or lose it”

adaptive changes that occur in response to aerobic or resistance exercise training are lost if the individual stops performing the exercise program

If activities can be incorporated into routine functional activities, then the adaptations can be maintained

Individual differences responses differ between individuals because of

age, genetic differences, initial fitness level, etc

Components of an exercise prescription

Intensity: How hard a person is working

Volume: What is the total amount of exercise?

Frequency: Number of session per day or week

Time: Duration of a bout of exercise in a session

Can be described as sets and repetitions

Includes the rest interval between sets or between exercises

Type: what is the mode of exercise?

Progression: how is the exercise prescription advanced?

Duration: total time frame of the training program

Intensity

how hard a person is working

For example, an aerobic exercise prescription could be based on HR response, a resistance exercise prescription could be based on % of 1RM

Submaximal vs. maximal loading – what is the goal and why?

Time

How long is the individual working during a bout of exercise?

Can be a set of amount of time, i.e. run for 20 minutes

Time can also be measured in sets and repetitions

Repetitions – number of times a particular movement is repeated. The number of muscle contractions performed to move the limb through a motion against a specific load.

Sets – a predetermined number of repetitions grouped together. After each set, there is a brief interval of rest

Volume

a measure of the overall stress of the exercise prescription

Volume = Frequency x Sets x Reps x Intensity

Example: According to ACSM, all healthy adults aged 18 – 65 should participate in 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, five days a week

Volume = 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity aerobic exercise

Volume should also consider the other physical stress (other exercises and non-exercise

physical activity)

Progression

The component of PROGRESSION refers to increasing the dosage of exercise over time

As the individual adapts, one or more components of FITT-VP can be increased as tolerated

Any component of FITT can also be reduced at any time if exercise is not tolerated

PROGRESSION must follow assessment and re-evaluation!

How do we prescribe therapeutic exercise?

FITT-VP

The classic exercise prescription has four components, which can be abbreviated by the acronym FITT

ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription extends this with two additional components: FITT-VP

FITT-VP is a useful memory aid; however, it may be more effective to change order in the actual exercise Rx process to begin with Type

Biological Factors

Age, sex and race

Height/weight relationship

Congenital disorders (skeletal deformities, neuromuscular/cardiopulmonary disorders or anomalies)

Family History of disease; genetic predisposition

Behavioral/Psychological/Lifestyle Factors

• Sedentary lifestyle

• Poor nutrition

• Use of tobacco, alcohol or other drugs

• Low level of motivation

• Inadequate coping skills

• Difficulty dealing with change

• Negative affect

Physical Environment Characteristics

Architecture barriers in the home, community and workplace

Ergonomic characteristics of the home, work or school environments

Socioeconomic Factors

Economic status

Level of education

Access to healthcare

Family or social support

SODH

• Economic Stability

• Education Access and Quality

• Healthcare Access and Quality:

• Neighborhood and Built Environment

• Social and Community Context

Selecting and Advancing Interventions

Initial Exercise Prescription

Dosage: FITT-VP

Tolerance: ability of the patient to successfully manage a given input or load based on their current level of abilities, impairments, and overall health.

Progression of Exercise

1. Continuous Assessment and Adaptation

2. Thoughtful Manipulation of Exercise Variables

Fatigue

Fatigue is defined as the inability to maintain force production for a given task

Muscle (local) fatigue – diminished response of muscle to repeated stimulus

Cardiorespiratory fatigue – systemic diminished response to prolonged physical activity related to the body’s ability to use oxygen efficiently

Factors that influence fatigue: health status, diet, lifestyle (sedentary/active)

Types of Fatigue

Motor Performance Fatigue

Quantifiable decrease in the maximal voluntary force production capacity of the neuromuscular system

Influenced by both neural and muscular factors

Perceived Motor Fatigue

The subjective experience of fatigue that emerges during a motor task, often described as a sensation of tiredness, weariness, lack of energy, or exhaustion

Mechanisms of Fatigue

• Overview of Central vs. Peripheral Fatigue

• Role of the Neuromuscular System

Peripheral Fatigue

Decline in muscle's ability to generate force

Causes:

Metabolic changes in muscle fibers

• Accumulation of byproducts (ROS, phosphates, calcium, lactate, ADP, magnesium)

Reduced glycogen

Effects:

Impaired muscle function

Slower muscle contraction

Key Byproducts:

Lactate, hydrogen ions, creatine, inorganic phosphate

H+ and Pi impair muscle function

Lactic acid not a cause of fatigue!

Central Fatigue

involves CNS influences on neuromuscular strength.

Influenced by physiological, psychological, and motivational factors

Stress and sleep deprivation can be factors

Affects cognitive functions and physical performance through higher brain structures.

Develops slowly in submaximal exercise

Other Fatigue Factors

Perception of Effort: Mental fatigue increases the perception of effort during exercise, making tasks feel more demanding and impairing endurance performance.

Stress and Sleep Deprivation: These factors significantly affect performance by altering neural activation patterns, slowing cognitive processes, and increasing subjective fatigue.

Motivation: Mental fatigue can decrease intrinsic motivation, which negatively affects performance, especially in tasks perceived as mentally demanding.

Cognitive Demands of Exercise: The cognitive load, including the need for sustained concentration and decision-making, is significantly impacted by mental fatigue, particularly in tasks that require both physical and cognitive effort.

Behavioral Changes: Mental fatigue leads to behavioral changes such as decreased self-selected pace and power output, which are influenced by changes in mental state rather than just physiological fatigue

Training can reduce fatigue

Physiologic Adaptation Through Specific Training:

Types of Training to Improve Mitochondrial Capacity:

Threshold Work -> increases buffering capacity.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) ->boosts mitochondrial efficiency and capacity, improving energy utilization and metabolite processing.

Long Duration Low-Intensity Training ->Increases mitochondrial density, enhancing overall endurance and fatigue resistance

Recovery Factors

1. Peripheral Fatigue

2. Central Fatigue

3. Tissue Damage

4. Cognitive Fatigue

5. Psychological Factors

Recovery

Central Fatigue Recovery:

Endurance Exercise: Recovers quickly within minutes.

Resistance Exercise: Recovers quickly but may take longer based on exercise extent and duration.

Peripheral Fatigue Recovery:

Endurance Exercise: Begins within 3-5 minutes; complete recovery takes longer but is generally faster

Resistance Exercise: Slower recovery due to muscle damage; can take days for full recovery.

Effect of Duration:

Short-Duration Exercise: Central fatigue resolves in minutes; peripheral fatigue begins recovery within minutes.

Long-Duration Exercise: Central fatigue takes longer due to prolonged neural involvement; peripheral fatigue recovery is delayed, taking hours or days for full recovery

Fitness- Fatigue Model

Implications for Training:

Short-Term Overreaching: High-intensity/volume phases followed by recovery can boost performance due to lasting fitness effects.

Overtraining Risks: Insufficient recovery leads to fatigue buildup, negating fitness benefits and risking overtraining syndrome.

Practical Application: Balance intensity, volume, and frequency to optimize gains while managing fatigue.

Plan workouts, recovery periods, and training cycles strategically to maximize performance.

Balance Between Overload and Recovery

Overreaching:

An accumulation of training and/or non-training stress.

Results in a short-term decrement in performance capacity.

May include physiological and psychological signs of maladaptation.

Recovery and restoration of performance capacity typically take several days to weeks.

Overtraining:

Also an accumulation of training and/or non-training stress.

Leads to a long-term decrement in performance capacity.

Might manifest with physiological and psychological symptoms of maladaptation.

Recovery process is more prolonged, taking several weeks to months

Overtraining Syndrome (OTS)

Physiological Symptoms

Persistent fatigue and tiredness

Increased susceptibility to infections

Changes in resting heart rate

Insomnia or changes in sleep patterns

Weight loss and appetite changes

Chronic muscle soreness or pain

Overuse injuries

Psychological Symptoms

Mood disturbances

Lack of motivation

Anxiety

Decreased concentration and focus

Performance Symptoms

Decreased performance

Inability to complete workouts

Prolonged recovery times

Altered heart rate response to exercise

Important Exercise Prescription Variables

Rest Interval

The time between sets or bouts of exercise.

Also the time in between exercises within a session.

Recovery

Time between exercises session

How does the individual feel and perform on the next session?

Frequency

The number or days per week an exercise session is repeated.

Duration

The total number of weeks or months an exercise program is carried out.

Capacity

defined as what a person can do in a standardized controlled environment.

An individual’s ability to execute a task or an action.

Highest probable level of functioning of a person in each domain at a given moment.

An individual’s ability to execute a task under ideal and controlled conditions, without the influence of environmental variables that might affect performance in daily life.

Assessed in a standardized environment

What an individual can do in a standardized, controlled

environment

Performance

describes what an individual actually does in

their daily environment.

Captures the actual activities a person engages in within

their typical daily life.

Takes into account both the physical and social

environment and personal factors like motivation.

Can include use of assistive devices

What an individual does do in their daily environment

Performance should never exceed Capacity!

Stress

• Broad response to any demand disrupting homeostasis.

• Can include emotional, psychological, or physical triggers

Physical Stress

• Force applied to biological tissue.

• Can be external (e.g., GRF during running) or internal (e.g., muscle tension generated to produce movement).

• Can lead to positive or negative adaptations

Exercise

• Planned, structured, and repetitive physical activity.

• Aims to improve physical fitness and overall health

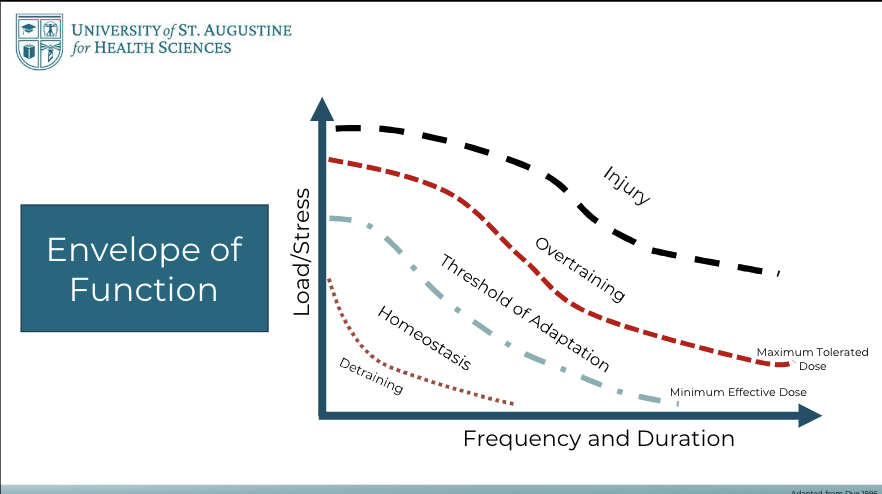

Physical Stress Theory

Physical stress levels that are lower than the maintenance range result in decreased tolerance of tissues to subsequent stresses (e.g., atrophy).

Physical stress levels that are in the maintenance range result in no apparent tissue change

Physical stress levels that exceed the maintenance range (i.e., overload) result in increased tolerance of tissues to subsequent stresses (e.g., hypertrophy).

Excessively high levels of physical stress result in tissue injury.

Extreme deviations from the maintenance stress range that exceed the adaptive capacity of tissues result in tissue death

Wolff's Law

Bones adapt to the loads they are subjected to; increased stress strengthens them, while reduced stress weakens them.

Bone Remodeling: Involves resorption of old bone and formation of new bone to adapt to mechanical stress.

Load-Specific Changes: Bone density and structure change according to the type and amount of stress applied

Davis’s Law

Soft tissues adapt to the demands placed on them, lengthening under tension and shortening in the absence of it.

Scar Tissue Formation: The law also plays a role in how scar tissues align along lines of stress, which is crucial for post-surgical or injury recovery.

Functional Adaptation: The adaptations are functional responses to the specific types and patterns of stress encountered, helping to improve efficiency and performance of the tissues under repeated stresses

Envelope of Function

Examples of Training Adaptations

Possible Physiological Adaptations to Exercise Training:

Aerobic Exercise:

Increased aerobic capacity, there is an increase in VO2max that occurs because of central adaptations (increase cardiac output) and peripheral adaptations (increased number and size of muscle mitochondria).

Resistance Exercise:

Skeletal muscle – increased mass (hypertrophy)

Neural system – increase in motor unit recruitment, rate of firing and synchronizing of firing of muscles

Metabolic system – increase in ATP storage and myoglobin storage

Body composition – increase in lean body mass, decrease in body fat

Connective tissue – increase in strength of tendons, ligaments and connective tissue in muscle, increase in bone mineral density

How does physical stress relate to capacity and performance?

Progressive Overload

For an exercise program to be effective, continual and gradual increase in training stress is required; As the individual adapts, performance increases

Becomes capable of producing greater force, power, or endurance

Training stress needs to adjust to match new level of performance

Not just about increasing Volume or Load!

Manipulate training variables to match stimulus to goals

Physical Activity

Any bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscles that results in a substantial increase over resting energy expenditure

Exercise

Planned and structured physical activity designed to improve or maintain physical fitness

Physiological Responses During Exercise

Ventilatory Responses

Cardiovascular Responses

Cardiac output

Muscle blood flow

Blood pressure

Metabolic Response

Exercise Induced Ventilation Responses

Muscle and joint mechanoreceptors and

proprioceptors send afferent sensory signals to

the motor cortex. The descending pathways

from the motor cortex to the respiratory

control center in the medulla increase

ventilations early in exercise. A Feed forward

mechanism.

Chemoreceptors in the aorta and carotid

arteries monitor PO2, PCO2 and pH and

influence ventilation rate

Blood Flow Distribution

This is a very important concept.

The shunting of blood to areas of need is how the body supplies blood to the exercising muscles.

Notice the 5x increase in cardiac output

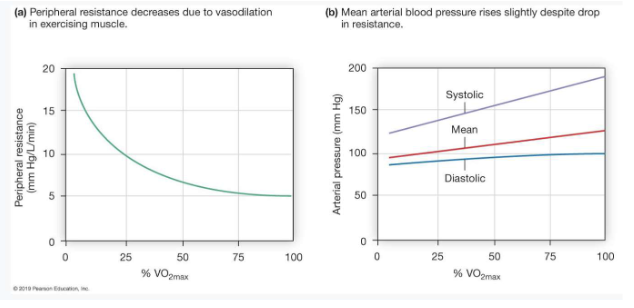

Blood Pressure Changes During Exercise

This is a very important concept.

Understanding the expected BP changes during exercise gives you insight into your patient’s tolerance and safety during exercise

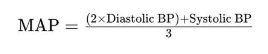

Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP)

Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) can be defined using the formula

During Exercise: The increase in cardiac output and changes in vascular resistance during exercise lead to an increase in MAP.

Diastolic BP (DBP): The pressure in the arteries when the heart is resting between beats. This phase is longer and thus has a

greater influence on the average pressure over the cardiac cycle.

Systolic BP (SBP): The pressure in the arteries when the heart beats and pumps blood

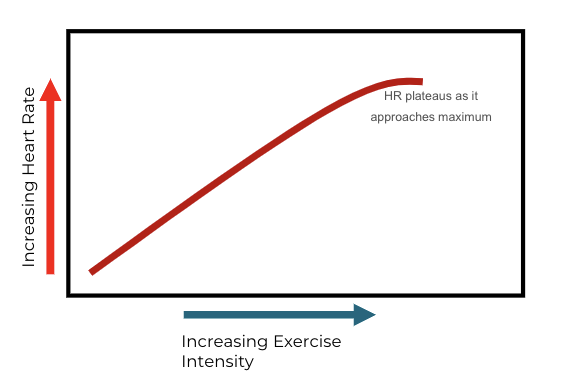

Heart Rate Changes During Exercise

HR should increase progressively and linearly with the intensity of exercise

This rise reflects the body's need to deliver more oxygen to working

muscles and to remove carbon dioxide and other metabolic byproducts

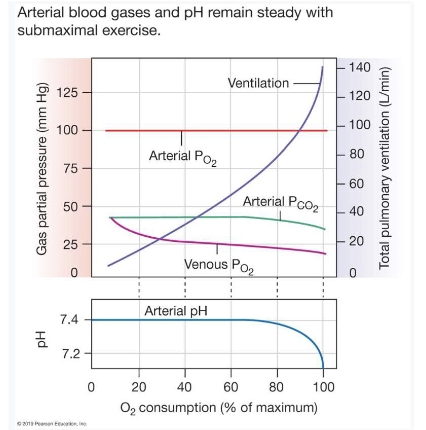

Blood Gases & Exercise

Note arterial PO2 remains steady during submaximal exercise. This is a normal exercise response If you are using a pulse oximeter on your .patient and observed decreasing oxygen levels – the exercise level is not being tolerated by your patient and should be stopped

Exercise Influences on Blood Glucose & Insulin Levels

Exercise has a positive effect on plasma glucose and insulin levels. It is important to educate your patients as to the role of exercise to improve and/or maintain appropriate plasma glucose levels especially with diabetic patients.

O2 Consumption & Exercise

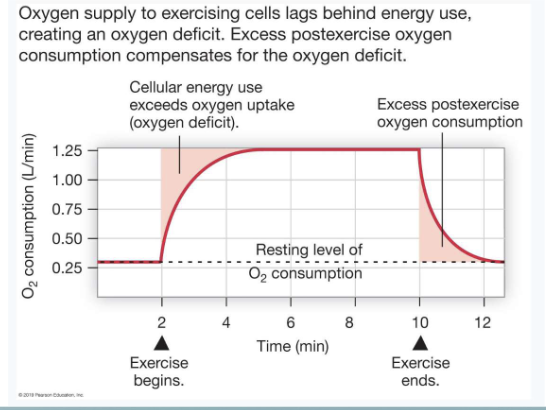

When exercise begins there is a need for energy that is greater that what the body can produce using oxygen. This creates an oxygen deficit which is made up with additional sources of energy that do not require oxygen (phosphocreatine, and anaerobic glycolysis)

Oxygen delivery increases and there is a leveling where energy and oxygen needs are matching, referred to as “steady state”.

At the conclusion of exercise, oxygen consumption does not immediately return to resting levels but stays elevated for a period of time

Autonomic Nervous System

Enhance Cardiorespiratory Function:

Increases cardiac output and blood pressure.

Regulates blood flow and volume.

Decreases airway resistance.

Vascular Control:

Vasoconstriction redirects blood to active muscles.

Releases hormones to maintain fluid balance.

Energy Mobilization:

Increases lipolysis and glycogenolysis.

Mobilizes fatty acids and glucose.

Thermal Regulation:

Controls blood flow and sweat glands for temperature regulation.

Promotes heat loss through skin vasodilation and sweat.

Hemostatic Responses:

Increases blood clotting ability during physical stress.

Balances clot formation and breakdown.

Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Activity:

SNS activation enhances exercise capacity.

PSNS withdrawal initially raises heart rate

Autonomic Nervous System During Exercise

Sympathetic Nervous System Activation:

Triggers "fight or flight" response during exercise.

Increases heart rate and cardiac output.

Redirects blood to active muscles.

Promotes glycogen and fat breakdown for energy.

Increases respiratory rate for better oxygen uptake.

Parasympathetic Nervous System Functions:

Dominates "rest and digest" activities.

Modulates heart rate at lower exercise intensities.

Facilitates quick post-exercise recovery.

Dynamic Balance Between Systems:

Sympathetic dominance increases with exercise intensity.

Parasympathetic activity aids in recovery post-exercise.

Adaptation and Efficiency:

Regular exercise improves autonomic response

Trained individuals have higher parasympathetic tone and a responsive sympathetic system for better performance and recovery

Changes in response to training stimulus over time

Neurological, physical, and biochemical changes

Improved Performance

Same amount of work can be done at a lower

physiological cost

Significant changes observed in 10-12 weeks

Adaptation depends on the organism's ability to change in response to a training stimulus

Training Stimulus Threshold

Individual with low fitness level has more potential to improve

Individual with higher initial fitness level will require greater intensity stimulus to improve

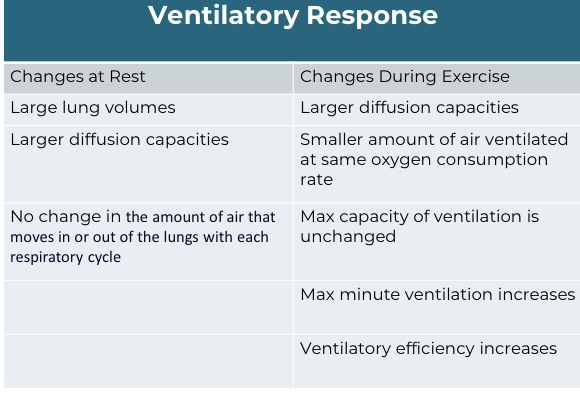

Physiological Adaptations to Exercise - ventilatory response