Lecture 4: CHALLENGES IN TREATMENTS AND INTERVENTIONS

1/16

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

17 Terms

Historically parasitic diseases like malaria and schistosomiasis have had much broader global ranges.

Malaria was once endemic to the eastern US and schistosomiasis in Japan. In both regions, the diseases have been eradicated in the sense that they are locally extinct.

On a global scale, few diseases have been eradicated, notably smallpox

Protection of the individual and herd immunity via mass vaccination worked because the viruses were sufficiently conserved that vaccination programmes could break the transmission cycle.

For malaria and schistosomiasis, vector control via improved water, drainage and hygiene were critical infrastructure measures, but mosquito control tipped the balance for malaria in the US

Recently, programmes to reduce malaria burden in sub-saharan Africa have made substantial progress due to mass roll-out of chemotherapies and vector control measures.

Whether eradication, elimination or control is the most realistic target for tackling a parasitic disease depends on the existence of…

1) a way to disrupt transmission

2) good diagnostics

3) a single vertebrate host (i.e. no reservoirs).

Factors such as infrastructure, political instability, resources and funding also contribute

Why are vaccines against parasites so elusive?

-Parasites are complex, long-lived organisms that require time to complete their complex life-cycles. They have developed sophisticated ways to manipulate and evade the host immune response.

-They transition through many developmental stages, adopting different morphologies and relying on stage-specific biological parameters for their survival.

-They occupy different niches across their life-cycles, both internal and external to their hosts.

-Many parasites are not lab-adaptable. We cannot grow them and study them in detail.

Vaccines are being developed to protect against malaria, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis and hookworm with varying degrees of success.

The malaria vaccines are the most advanced.

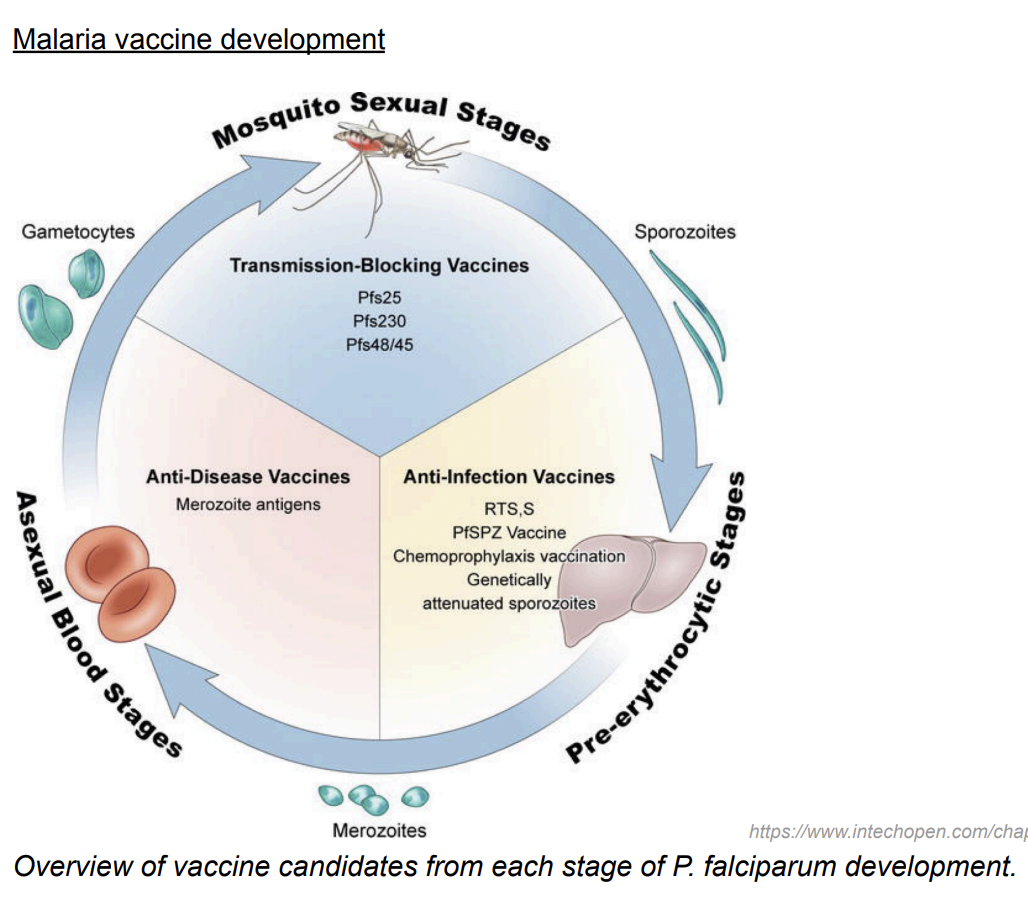

Malaria vaccine development targets 3 stages:

the sporozoite that gets injected into the host by an infected mosquito

the merozoite that bursts out of erythrocytes during the blood stage of infection

the mosquito stages (gametocytes, gametes, ookinetes) that develop in the mosquito midgut following uptake of gametocytes in a blood meal.

What is today’s most he most advanced malaria vaccine?

RTS,S, a pre-erythrocytic stage vaccine consisting of:

- a virus-like particle (VLP) that displays hepatitis B surface antigen alone (S) and fused with a P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein fragment containing its central repeats and T cell epitopes (RTS).

RTS,S has shown an efficacy of 51.3% against clinical malaria in children over 12 months after three doses of the vaccine.

Although this represents important progress and reduced clinical disease, it has no effect on transmission and parasite control.

Transmission blocking vaccines

Utilise antigens expressed during mosquito parasite stages (gametocytes, gametes, zygotes and ookinetes) to induce functional antibodies that attack the parasite in the mosquito and impair its viability, inhibit its development, or impede its interaction with the mosquito midgut.

This will reduce the number of circulating infectious mosquitoes below a threshold that sustains transmission.

The benefit of this approach is the natural population bottleneck in the number of parasites (1-10 parasites) that make this transition as compared to the preceding blood stage where parasite numbers can reach 1x109 .

Chemotherapy

Ivermectin- a blockbuster drug, used widely in veterinary medicine to treat lung and stomach worms in cattle, scabies in pigs, and heartworm in dogs. Also used to treat Onchocerca volvulus in humans, the filarial worm that causes River Blindness.

Praziquantel- used to treat schistosomiasis.

Albendazole- used to treat intestinal parasites, given as part of annual deworming programs. Administered annually and have been very effective in reducing worm-related morbidity in children. Currently not given frequently enough nor widely enough to interrupt transmission and lead to elimination. There is also some evidence in farm animals that giving these drugs too frequently (every few weeks) can drive resistance.

Artemisinin- artemisinin and its derivatives are used as part of combination therapies to treat malaria.

Plasmodium falciparum parasites have developed resistance to most antimalarial drugs available.

The current ‘gold standard’ treatments for malaria — the drug family including artemisinin and its derivatives — are often administered alongside ‘partner’ drugs in what are called artemisinin-combination therapies (ACTs), because multiple drugs are more difficult for parasites to develop resistance against.

Nevertheless, resistance to these ACTs is prevalent in southeast Asia and has been identified on the African continent as well. Although ACTs are still effective, resistance is of great concert as there are currently no alternative treatments available.

Co-infections complicate treatment options.

Care must be taken when administering antiparasitic drugs, as treatment of one parasite can exacerbate pathology caused by another, sometimes fatally.

For example, ivermectin effectively treats Onchocerca volvulus but can cause severe inflammation and encephalopathy in individuals co-infected with Loa loa.

Although L. loa usually causes mild disease, high worm burdens and sensitivity to ivermectin lead to rapid parasite death which elicits a massive immune response, resulting in severe neurological complications.

Vector control

Vector control has proven to be critical to interrupting transmission.

The widespread use of the organic compound DDT has targeted mosquito populations and eradicated malaria from some parts of the world.

The use of pyrethroid-impregnated bednets, DDT indoor residual spraying, and ACTs has measurably reduced the incidence of P. falciparum malaria in sub-Saharan Africa.

Exploitation of parasites

Some parasites can beneficially modulate host immunity, reducing allergy and autoimmune pathology, reflecting their long co-evolution with vertebrate hosts and ability to manipulate host biology.

Therapeutic examples include:

-Trichuris suis in treatment of ulcerative colitis and protein delivery to the brain by Toxoplasma gondii. Ingested eggs of the pig whipworm, T. suis, hatch transiently in the human gut, where the parasite immunomodulates the local environment, leading to disease remission before being naturally expelled.

Similarly, the ability of Toxoplasma gondii to cross the blood–brain barrier is being exploited by engineering non-pathogenic strains to deliver therapeutic proteins to brain cells, with potential applications in neurological disorders.

Studying parasites therefore not only informs disease control but also reveals novel therapeutic opportunities and fundamental insights into vertebrate biology.