Bio 219 Exam 3 WVU

1/102

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

103 Terms

C-paradox

The fact that genome size has no correlation to genome complexity

Genome size is also not correlated with the number of genes in an organism

Complexity of a genome

A measure of how many repetitive DNA regions there are

An experiment can be done to determine a genome's complexity. DNA sequences are cut apart via melting. When the DNA cools down, more complexity genomes will take longer to reanneal while noncomplex genomes will come together more quickly

This is because noncomplex genomes have more repeats and can therefore find a match quicker

Tandem repeats

A DNA sequence that repeats over and over again

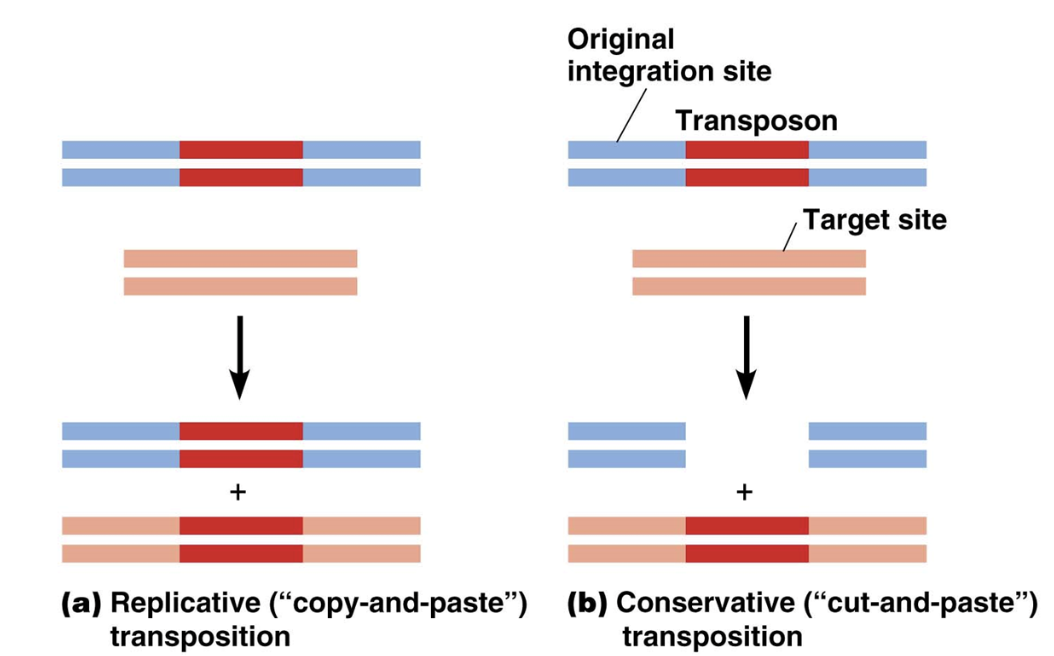

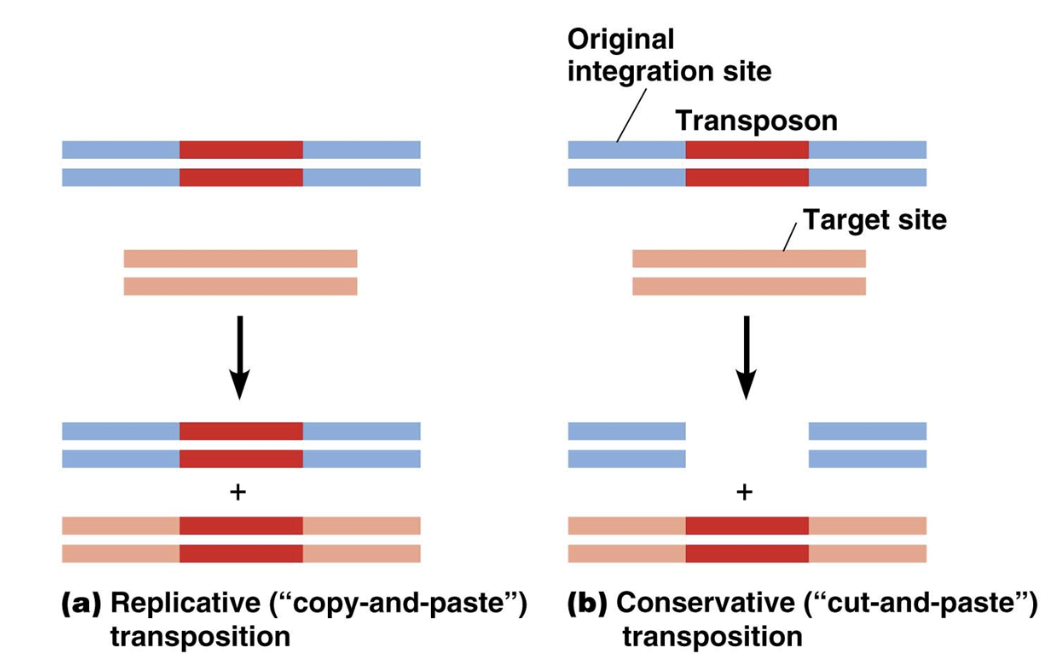

Interspersed repeats/transposons

A DNA sequence that cuts and paste OR copy and pastes itself into different parts of the genome

Also called jumping genes

Satellite

A type of tandem repeat

Simple repeats. 3-10 base pairs repeated 107 times

An example is telomeres. They extend the end sequence on a chromosome in order to protect it

Mini satellite

A type of tandem repeat

10-60 base pairs repeated 105 times

Used in forensic DNA fingerprinting

Microsatellite

A type of tandem repeat

1-5 base pairs repeated to make 100 base pairs total.

Often a consequence of RNA polymerase doing its job poorly and accidentally repeating the same region of DNA several times in a row

Often expand coding regions and can lead to diseases like Huntingtons Disease

Replicative transposition

A mechanism transposons use to move locations in the genome

A specific DNA region gets copied via transcription and pasted somewhere else

Turns RNA into DNA using reverse transcription

DNA region gets pasted by ligase and cut by enzymes

Conservative transposition

A mechanism transposons use to move locations in the genome

A specific DNA region gets cut and pasted somewhere else

DNA region gets pasted by a ligase and cut by enzymes

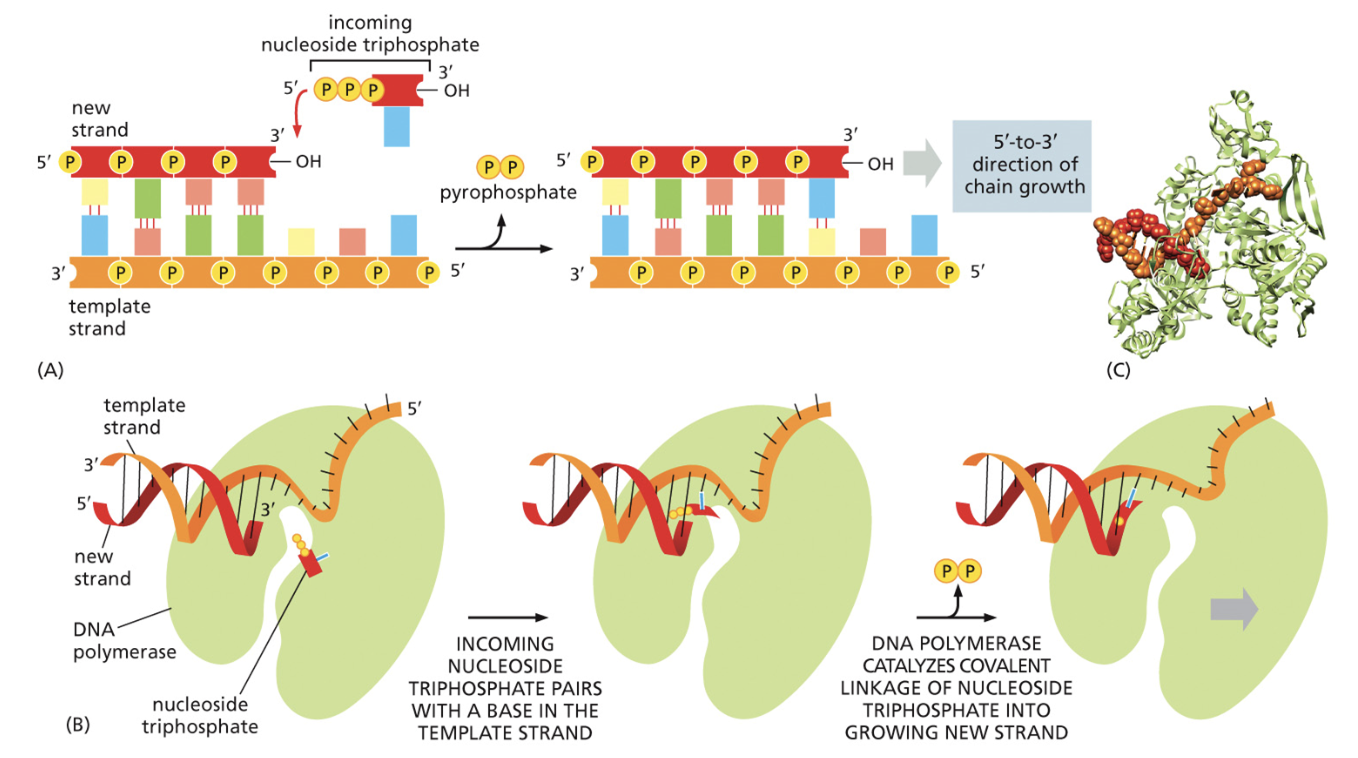

DNA is always BUILT from the _______ and the template strand is always READ from the ______

3’ —> 5’ end

5’ —> 3’ end

Helicase

A molecule needed for DNA replication

Unzips the hydrogen bonds between DNA strands

Single stranded binding protein (SSB)

A molecule needed for DNA replication

Holds DNA strands open and prevents DNA strands from reannealing

Topoisomerase

A molecule needed for DNA replication

Relieves tension caused by unwinding DNA strands

It creates a double strand break and pastes strands back together using ligase

Primase

A molecule needed for DNA replication

Adds an RNA primer that is used by DNA polymerase

Ligase

A molecule needed for DNA replication

Pastes DNA fragments together like glue

Meselson-Stahl experiments

Displayed that DNA replication was semi-conservative

DNA was grown in a heavy nitrogen environment for many generations, then they were put into a normal nitrogen solution

They then put the DNA in a gradient. How far DNA went down depended on the density of it.

They found that after the 1st round of replication, DNA was half heavy nitrogen and half normal nitrogen. This was the expected result from a semi-conservative model of replication

Okazaki experiments

Displayed the DNA replication was discontinuous

DNA strands were labelled very shortly after replication began.

After 20 seconds of replication, they found that there were some medium sized portions of DNA, and some very short fragments of DNA

After 60 seconds, the very short fragments of DNA were gone. Their theory was that small DNA fragments got put together.

They tested their hypothesis by doing the same process, but with DNA fragments not containing ligase. They found that whether they looked at the DNA after 20 seconds or 60 seconds, there were always many short fragments

DNA polymerase III

Puts DNA together

Has a crab claw shape

Nucleotides come in. A guess and check mechanism is used to see if hydrogen bonds can be made with the parents strand of DNA.

If it's a match, a condensation reaction occurs, and the nucleotides join together. But if not, the nucleotides flow right back out of the polymerase.

When nucleotides are added together, two phosphate groups of the new nucleotide are cleaved off. That nucleotide hydrolysis provides the energy needed to continue growing the chain of DNA

How is DNA put together?

Nucleotides come in. A guess and check mechanism is used to see if hydrogen bonds can be made with the parents strand of DNA.

If it's a match, a condensation reaction occurs, and the nucleotides join together. But if not, the nucleotides flow right back out of the polymerase.

When nucleotides are added together, two phosphate groups of the new nucleotide are cleaved off. That nucleotide hydrolysis provides the energy needed to continue growing the chain of DNA

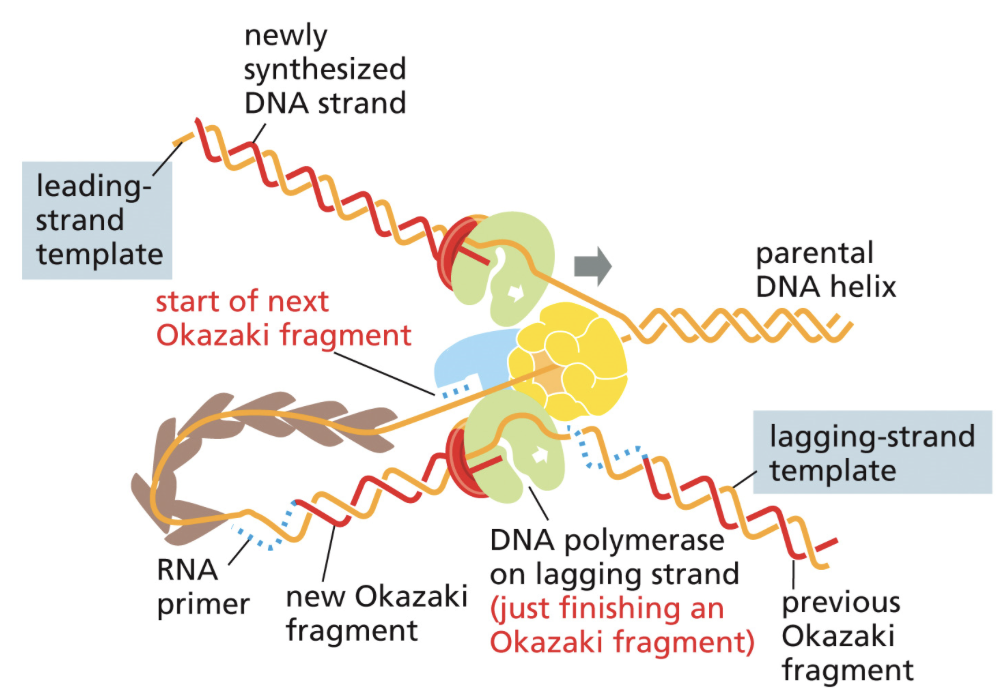

How is the lagging strand of DNA put together?

A different procedure for replication must be done for DNA replication on the lagging strand of DNA due to DNAs antiparallel structure

DNA polymerase, helicase, and primase all join together in one big complex. The lagging strand must loop around it to go in the same physical direction as the parent strand

The lagging strand can only be copied one loop at a time for it to be in the proper direction. Okazaki fragments are the length of one of these loops

Once the Okazaki fragments have been synthesized, two things need to happen:

Primase must be removed and replaced by DNA. Done by DNA polymerase I

Okazaki fragments must be pasted together by ligase. Ligase forms phosphodiester bonds between fragments

Okazaki fragments

Short segments of DNA that is synthesized discontinuously on the lagging strand

Made because DNA can only be synthesized from the 5’ —> 3’ direction

DNA polymerase I

Removes primers and replaces them with DNA

Needed during the replication of DNA coming from the lagging strand to make Okazaki fragments

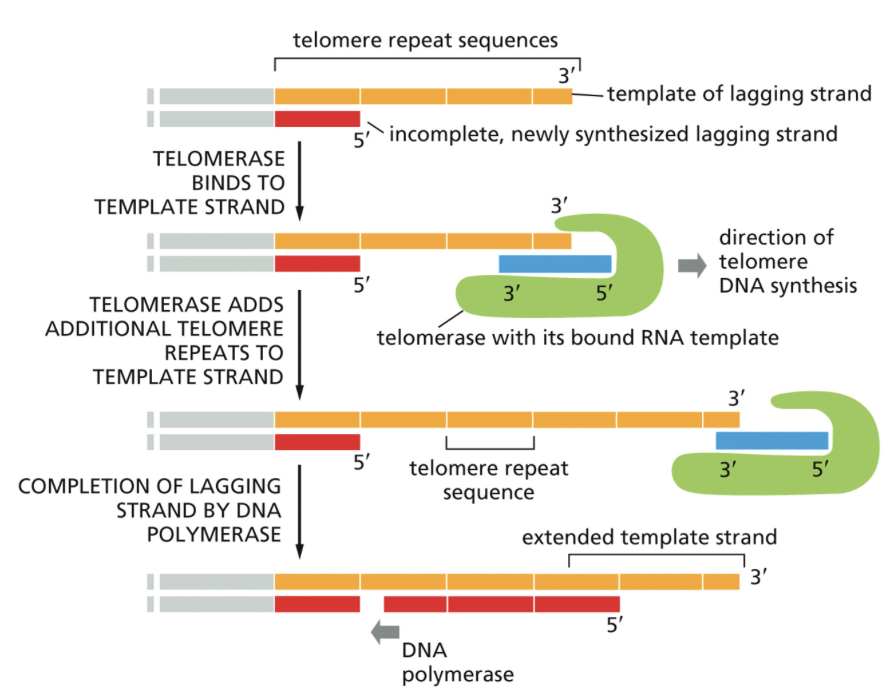

Telomerase

Copies the ends of chromosomes

Because replication begins from a primer, the ends of chromosomes cannot be replicated in the typical way

Telomerase extends template strands of DNA and allows new primers to be added. Has its own RNA template in order to expand template DNA

What can result from DNA damage?

Damage to a regulatory region can lead to too much or too little of a product being made

Damage to a coding region can lead to the incorrect protein being made. This can lead to improper protein folding and a change to allosteric interactions. Changes in allosteric interactions means a change to protein functions

How does DNA get damaged?

A nitrogenous base being deleted altogether. This makes the template strand wrong when DNA is copied. The structure is not initially affected.

The phosphate of one nucleotide and the sugar from another nucleotide breaking. If one strand breaks, ligase easily puts it back together. If both break, ligase doesn’t know what’s what. This can lead to a part of one chromosome being connected to a completely different chromosome

Bases becoming covalently bound together. This affects the strand's ability to properly pair with another strand and contorts the DNA’s structure.

Why are deletions or translocations worse than other types of DNA damage?

The cell can only fix damage that affects the protein's structure. It cannot easily detect things like deletions or translocations where the DNA is still in tact.

What are the steps taken to repair damaged DNA, in general?

Remove the damaged section through the breaking of phosphodiester bonds via nuclease

Repair the damage through DNA polymerase

Seal the gaps using ligase

DNA Polymerase Proofreading

Fixes mismatches

Occurs during S phase of the cell cycle

A repairing exonuclease that reads from the 3’ → 5’ end detects mismatches through incorrect bond angles and fixes the DNA by trimming.

The damaged region flips out of the RNA polymerase site and into the exonuclease site. It flips it back up once it’s done cleaving

Mismatch repair

Fixes mismatches

Occurs after replication but before cell division, when DNA is still differentially methylated

Detects mismatches through bond angles and DNA methylation

Cuts out the damaged DNA opposite of the methylation, put in the proper nucleotide, then paste the DNA back together with ligase

Only daughter strands are changed and fixed, not the parent strand.

Base Excision Repair

Fixes mismatches

Fixes damage during interphase, G1, and G2. Usually occurs during one of the checkpoints of cell division

Detects damage through bond angles

Bases themselves are removed, not the entire nucleotide, by cutting phosphodiester bonds of the backbone atoms, repairing the cut with polymerase, and ligating the nucleotides back together.

Nucleotide Excision Repair

Fixes pyrimidine dimers that mistakenly got bound together

Fixes in interphase G1, and G2

Detects through scanning during transcription

Occurs when there’s two thymines on the same strand of DNA

In this case, it is not enough to cut out just one nucleotide. Instead, both cross linked nucleotides must be removed.

A whole major groove DNA ends up being removed, about 10 nucleotides. DNA polymerase then repairs the strand again, using the undamaged strand as a template. Ligase pastes the pieces together

Non-homologous End Joining

Fixes double strand breaks when there is no template for recombination.

Fixes during interphase and G1

Detects through proteins that recognize free ends

Enzymes recognize the broken phosphodiester bonds on the strands and proceeds to trim off even more nucleotides. Ligase then pastes the pieces together again

2 parts from completely different chromosomes may end up being joined together via non-homologous end joining. The cell doesn’t know where the broken piece belongs. Called translocation

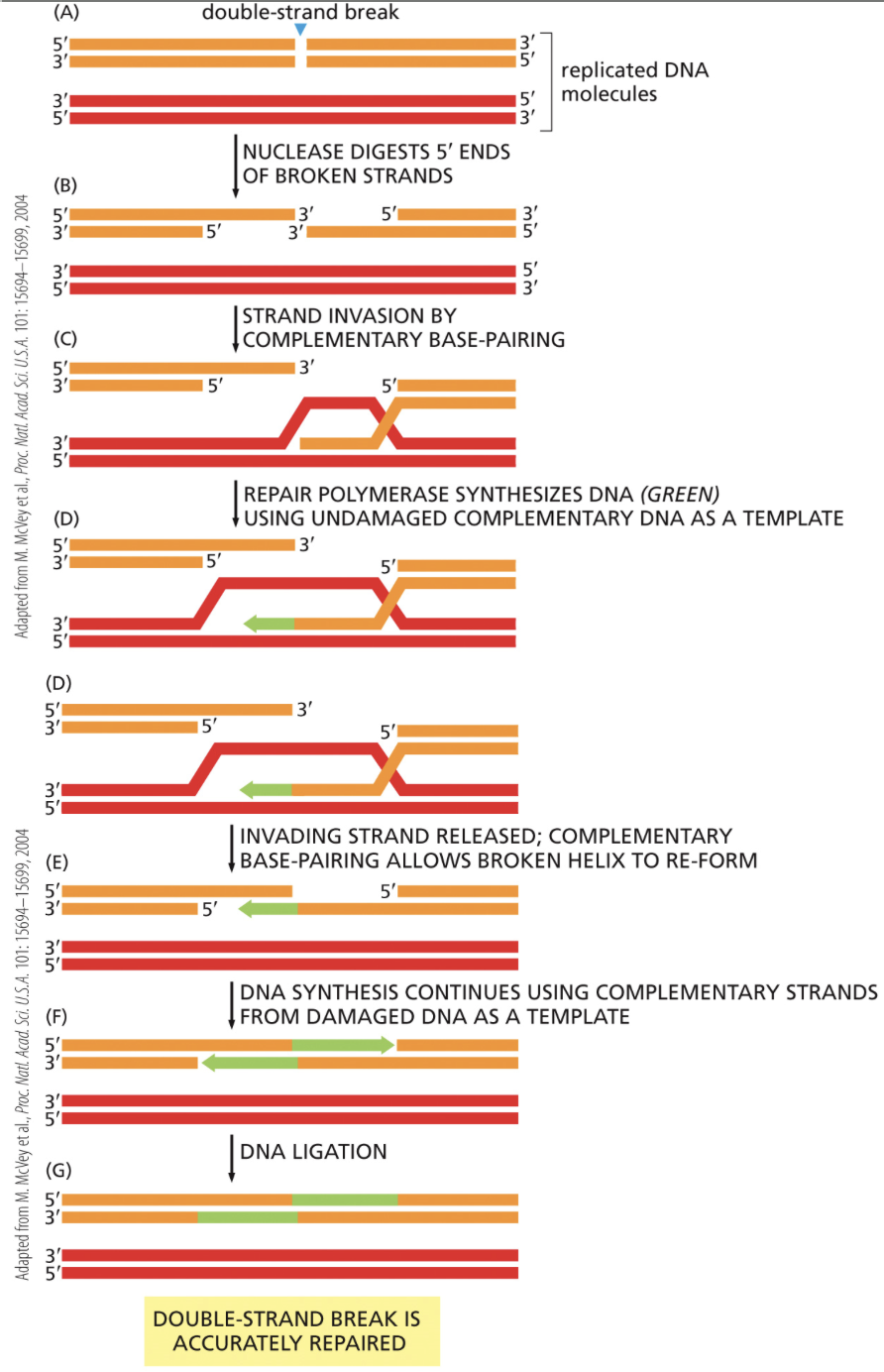

What’s a double strand break?

When both phosphodiester bonds on two strands of DNA break

Homologous End Joining

Fixes double strand breaks and mismatches when there is a template

Fixes after S phase, but before mitosis and meiosis

Newly synthesized strands of DNA from S phase become the template for replication in homologous recombination. Results in a strand identical to the one before the double strand break

What are the steps of repairing double strand breaks via homologous end joining?

Identify the damage

Trim back ends so the strand is complementary to the template strand made in S phase

Strand that needs to be repaired invades into the template strand

3’ of an undamaged strand end extends using the template strand

Pieces are ligated together

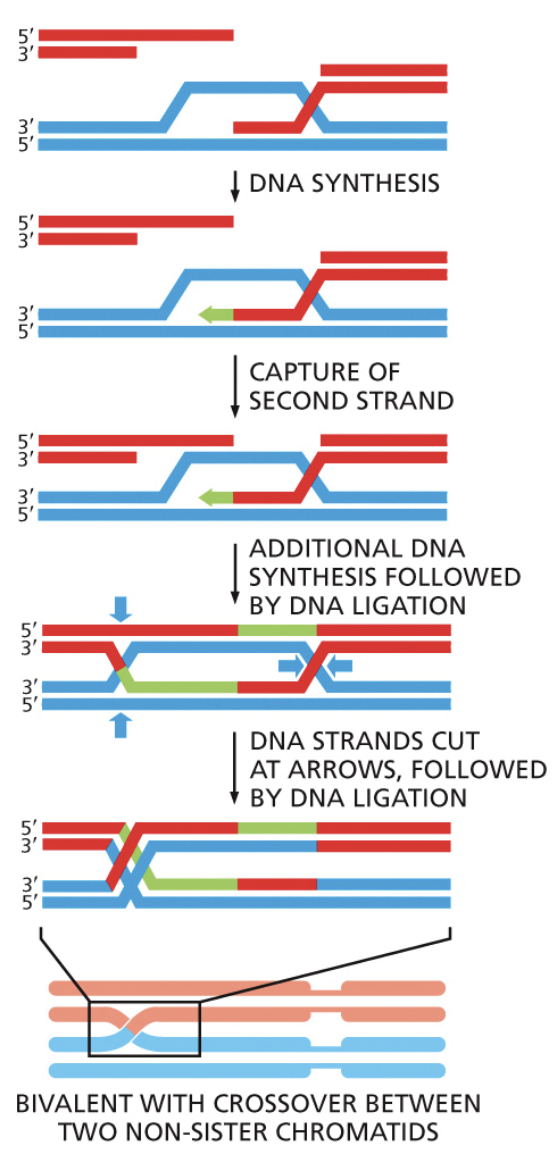

How is homologous end joining for DNA repair different from homologous end joining that occurs during Metaphase I of meiosis?

DNA repair via homologous end joining makes DNA identical to the way it was before the double strand break.

Homologous end joining in meiosis does not make identical DNA. It allows for new genotypes to arise.

In meiosis, homologous chromosomes pairs align, rather than individual chromosomes.

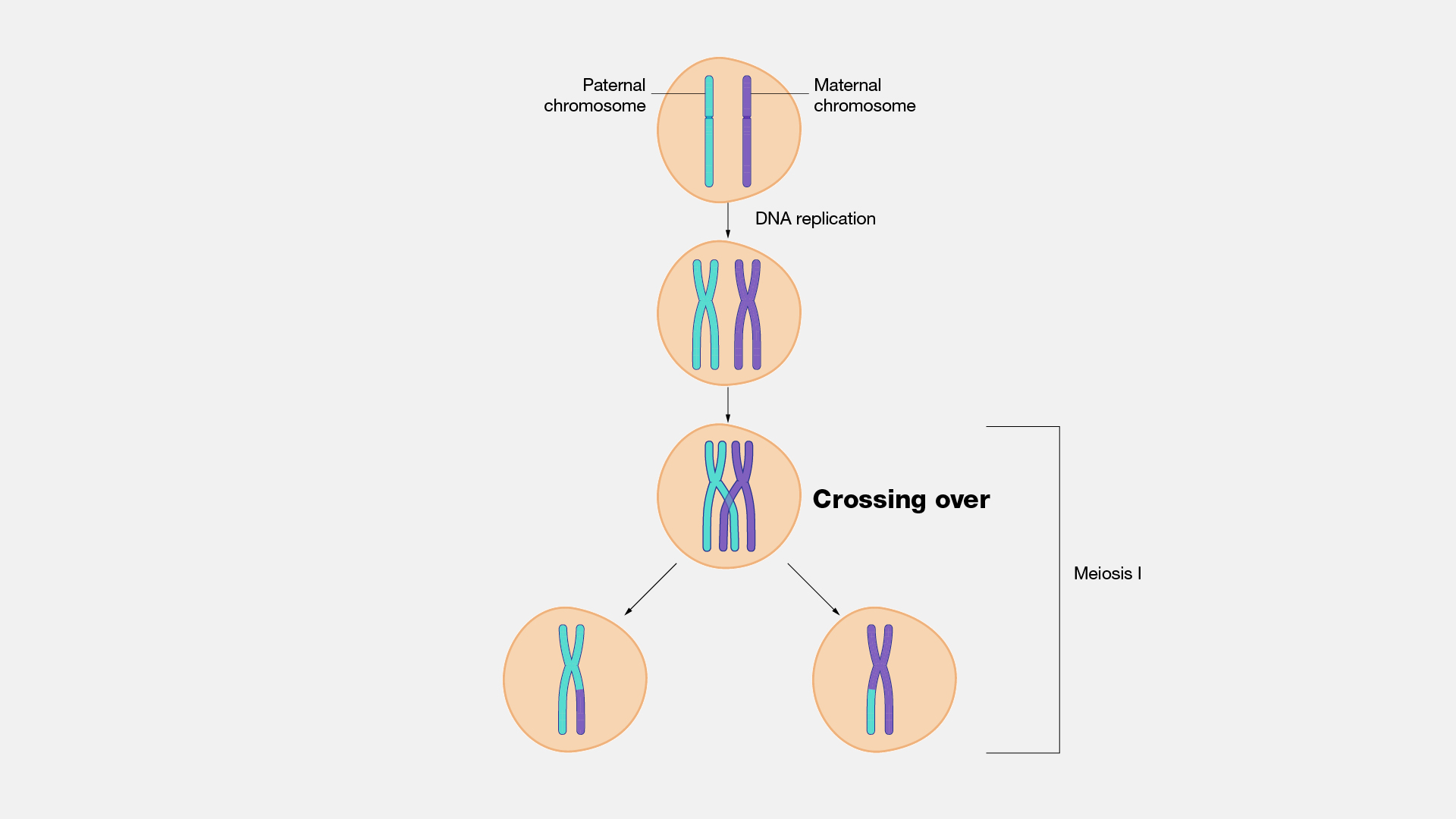

Crossing over

The name for homologous recombination that occurs during Metaphase I of meiosis. Gives rise to genetic variation

When homologous chromosome pairs line up on the metaphase plate, a double strand break is intentionally made by recombination proteins

A nuclease digests the 5’ end of both strands of the DNA that were just broken

Strand invasion occurs with the broken chromosome from one parent and an unharmed strand from another parent

DNA is synthesized with polymerase using the other parents chromosome as a template

A ligation event pastes these two chromosomes together in what is called holiday junctions.

Eventually the holiday junctions break and the result is two chromosomes with a few new alleles from the opposite parent

Holliday junction

A four way DNA structure that’s created when two homologous DNA molecules cross over

Can slide back and forth

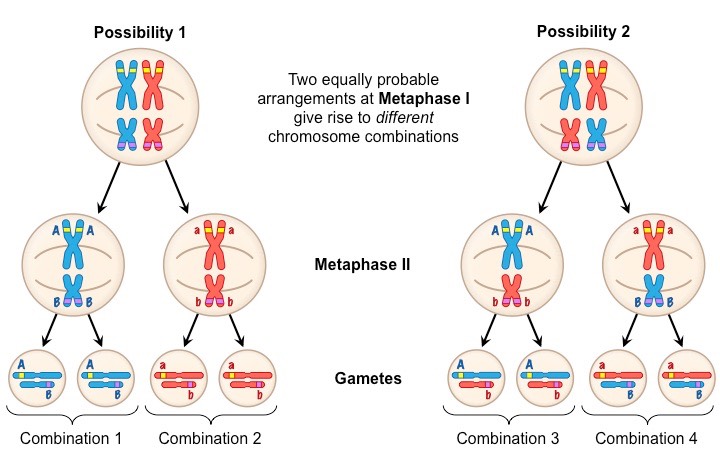

Independent assortment

The principle made by Mendel that concludes individual alleles of different genes assort into gametes independently. Allows for further genetic variation among a species

All possible combinations of alleles could occur depending on how homologous chromosomes happen to line up on the metaphase plate

Allele A and allele B will NOT assort together

What are the 5 ways genetic variation can occur?

Mutations through DNA polymerase messing up

Naturally occuring tautomers; DNA reacts and moves electrons around

Environmental changes

Recombination/crossing over

Independent assortment

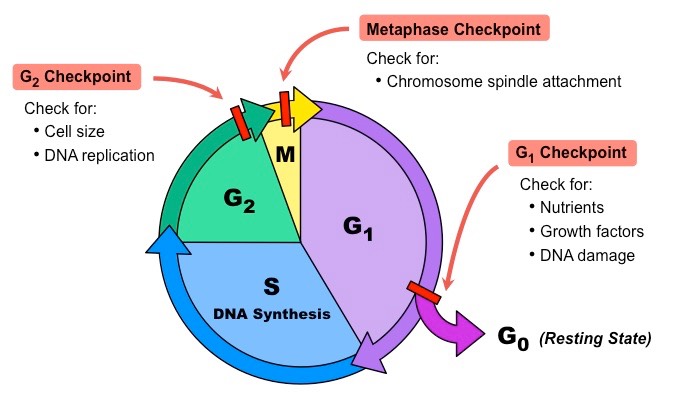

What are the 4 stages of the cell cycle?

Growth 1 (G1)- Cell grows and carries out its normal functions. Before S phase, the cell evaluates if it’s environment is favorable for replication. This is checkpoint 1.

Synthesis (S)- DNA replication occurs

Growth 2 (G2)- Cell grows more and does its normal functions. Before the cell enters mitosis, it evaluates if all it’s DNA has been copied and if there’s any damaged DNA. This is checkpoint 2

Mitosis (M)- Cell divides and goes through either mitosis or meiosis. During M phase, there’s another checkpoint that evaluates if all chromosomes have been attached to mitotic spindles

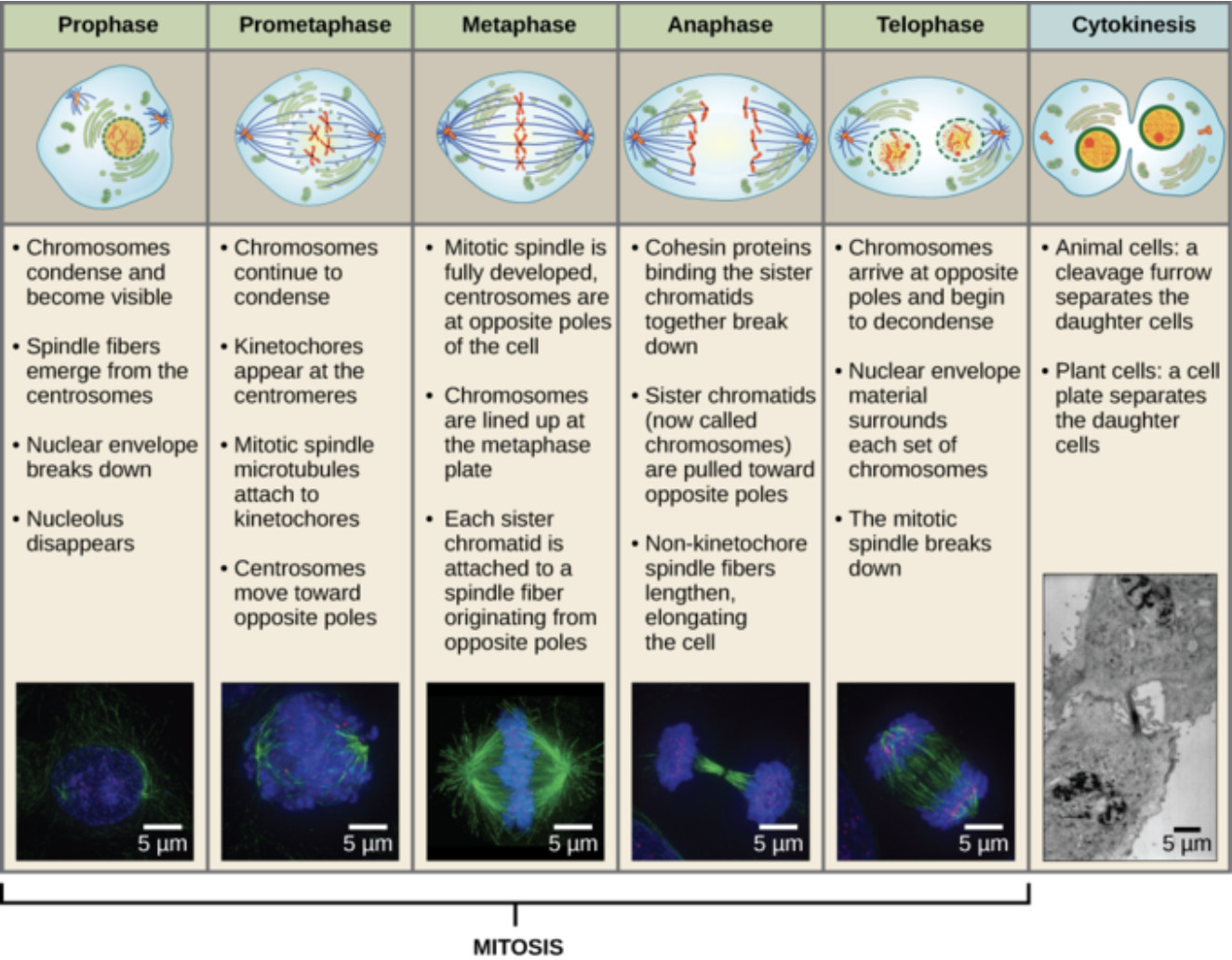

What are the 7 stages of mitosis?

Interphase- Where the cell spends most of it’s time. The cell is in interphase during G1 and G2. The cell increases in size and centrosomes are duplicated

Prophase- Nuclear lamins are phosphorylated, which breaks down its membrane. Microtubules emerge from centrosomes. Chromosomes are condensed by condensin

Pro-metaphase- The nuclear membrane fully breaks down. Spindles begin to attach to chromosomes

Metaphase- Sister chromatids line up on the metaphase plate, in the middle of the cell, attached to microtubules. Cell goes through the checkpoint

Anaphase- Sister chromatids are pulled apart. They’re pulled towards opposite poles via kinesins and dyneins

Telophase- Nuclear lamin is dephosphorylated and membrane reforms. Two new nuclei are created

Cytokinesis- The actin cytoskeleton arranges around the contractile ring. Actin gets shorter and shorter via contraction until there are finally two cells

What does phosphorylation of the nuclear lamin do in Prophase of mitosis?

It breaks up the intermediate filaments that make up the lamin

The phosphorylation of the filaments adds a negative charge to it which disrupts the interaction between lamins and the nuclear membrane

How do microtubules grow/shrink in order to line chromosomes up on the metaphase plate?

They add GTP bound dimers at the + end or the removal of GTP bound dimers at the - end

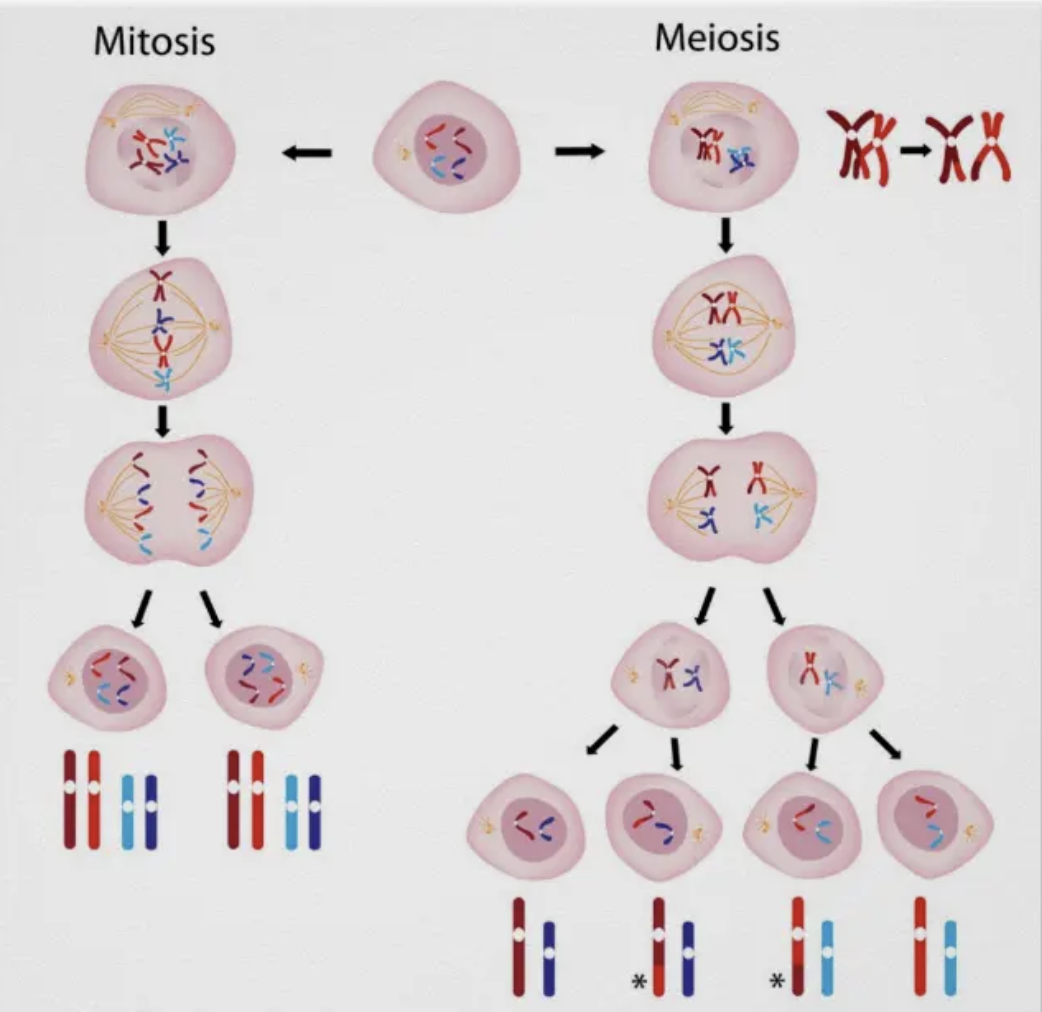

What are the differences between mitosis and meiosis?

The difference between meiosis and mitosis is in Anaphase I of meiosis:

In meiosis, cells undergo one replication event and two cell divisions. In mitosis, there is only one replication event and one cell division.

In mitosis, each of the 4 chromosomes has its own place on the metaphase plate. Each chromosome is represented one time. In meiosis, each chromosome PAIR gets its own place on the metaphase plate.

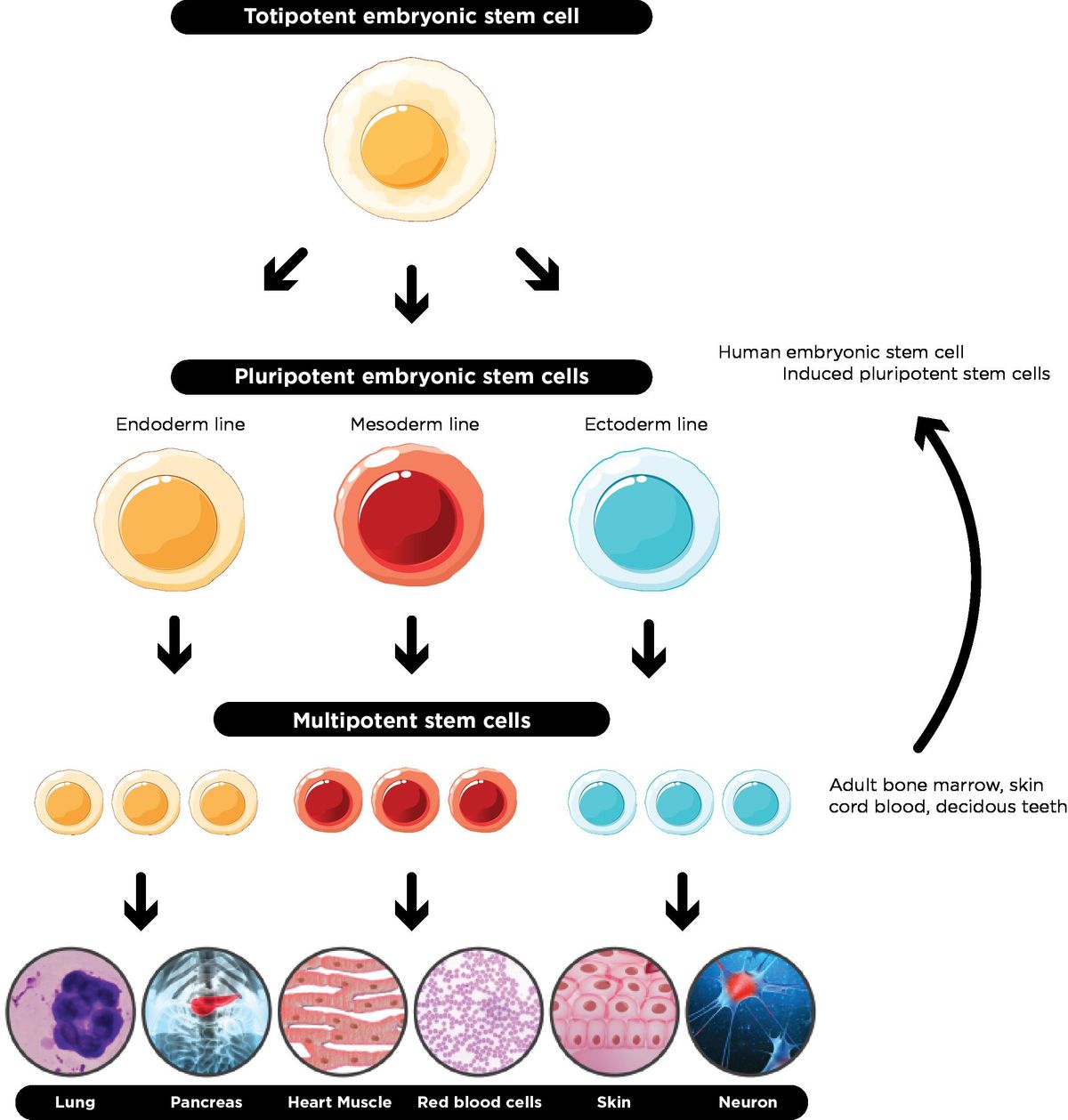

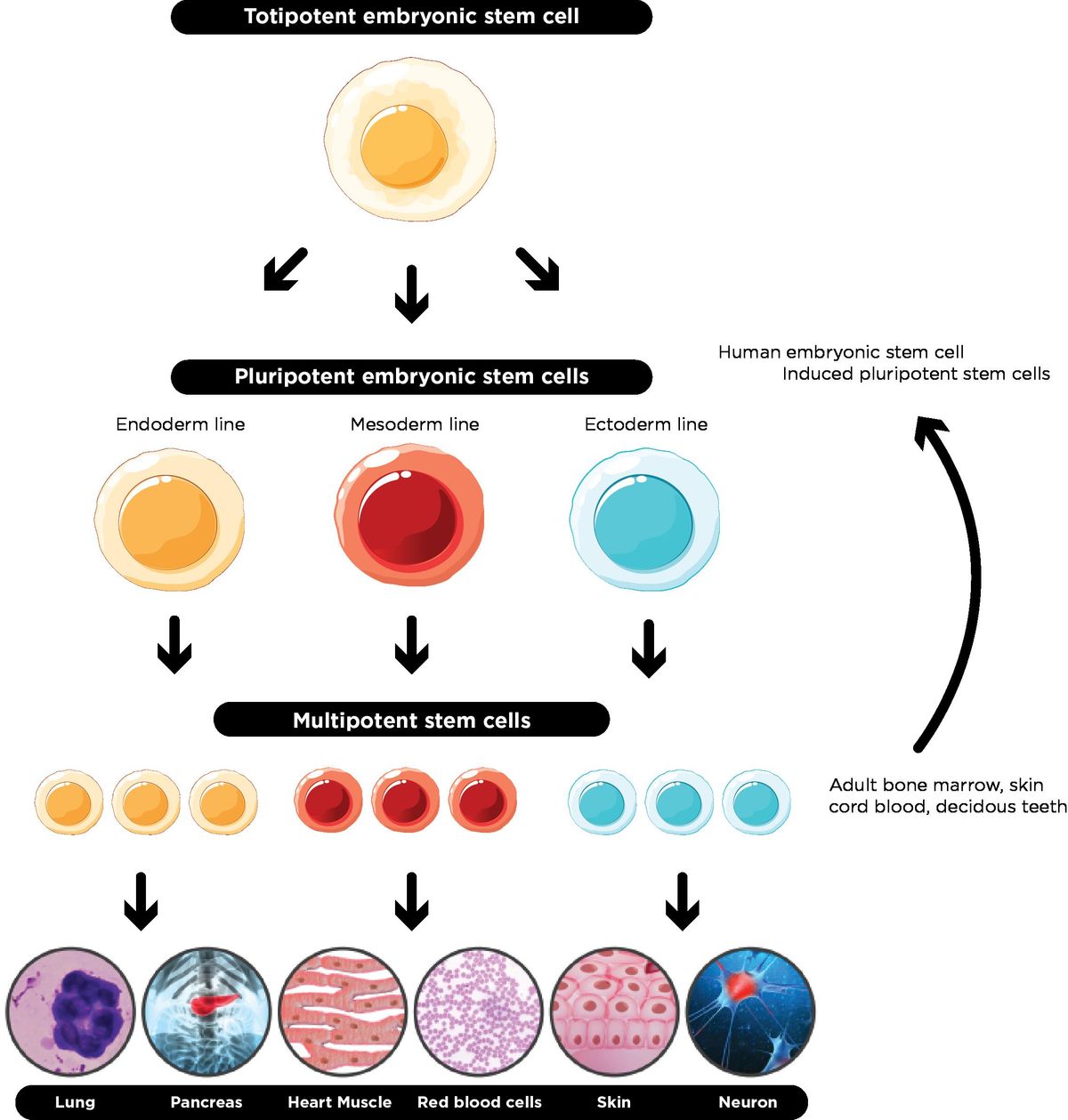

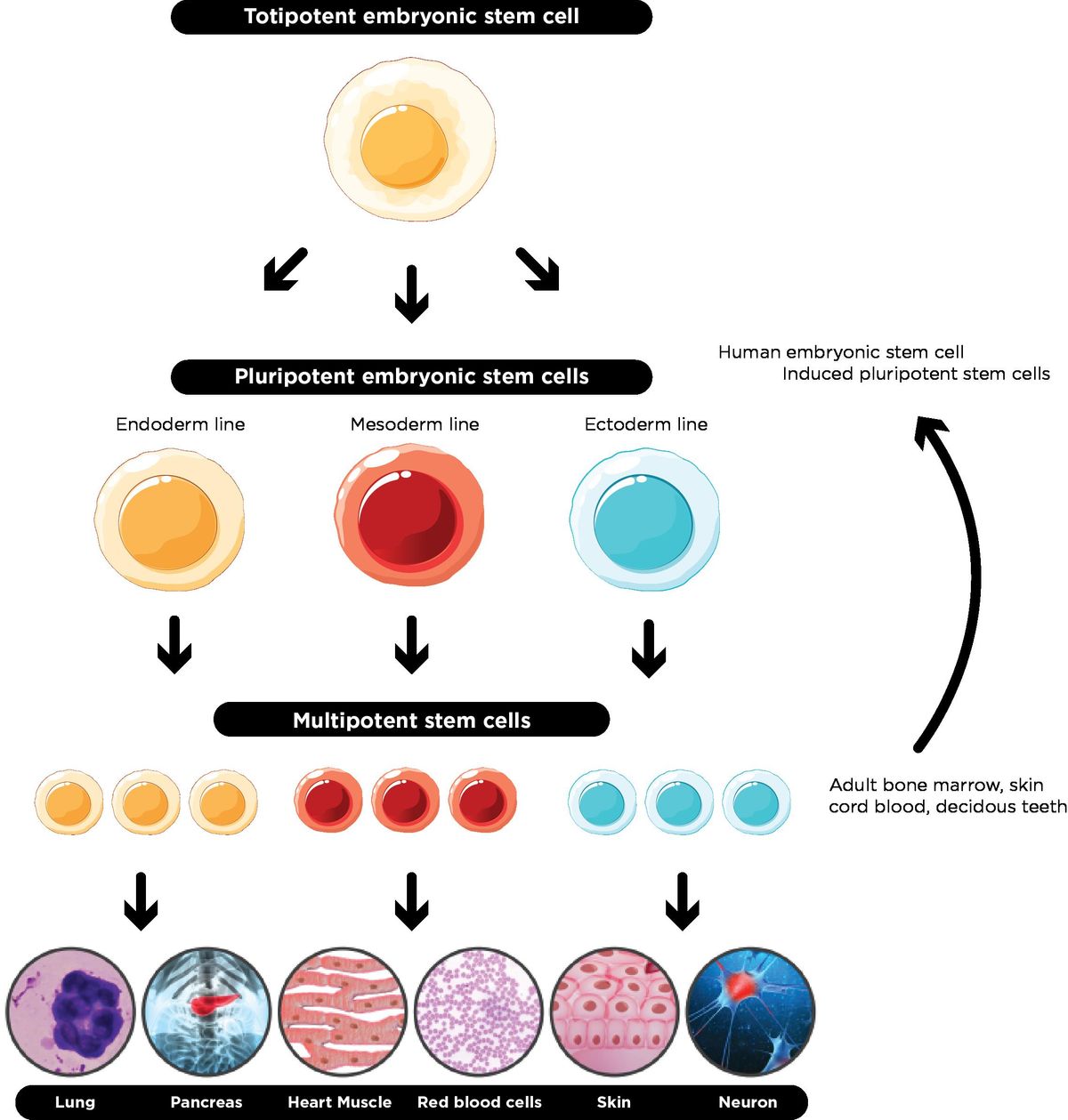

Totipotent

The potential a cell has as soon as it becomes fertilized. It has the MOST potential

It has the ability to become literally any cell type in the organism OR apart of the placenta of the parent in mammalian organisms

Pluripotent

The potential a cell has immediately after it makes one differentiation

Can make up any type of cell the new organism needs, but it now cannot make up the placenta of the parent

“Stem cells” usually refers to pluripotent cells

Multipotent

The cell knows which derm it's apart of (mesoderm, endoderm, or ectoderm), but not which organ it’s a part of.

The most differentiated a cell can be without being designated to a specific organ

Which 2 simultaneous processes must stem cells be able to undergo?

It must be able to make an identical copy of itself that is still a pluripotent stem cell AND a multipotent copy that is able to differentiate and become what the organism needs. The genomes of both cells are still identical, despite their different functions

The multipotent cells must be able to make different RNAs and proteins than the stem cell

How does a cell get its “identity”?

Identity is defined by functions and characteristics, NOT by it’s DNA. All cells in an organism (except gametes) contain the same DNA

A “cell type” is ultimately just a way of naming cells by the molecules (especially proteins and RNAs) that they contain

How can cells be redifferentiated?

Isolating a cell on a plate and “reprogramming” it with molecules from pluripotent cells

Wait a few weeks. Now the plate has induced pluripotent cells

Change the cell culture conditions again through its environment or the proteins in the dish that simulates the conditions of the desired cell type

Wait again, and boom. The stem cell is now the desired cell type

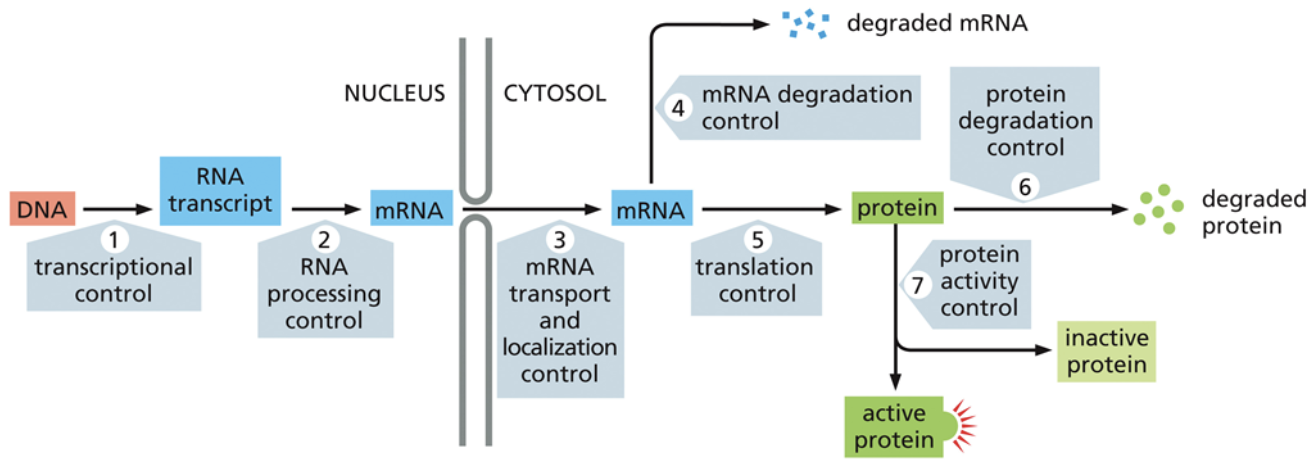

What does gene regulation do?

It determines when, where, and how much of a protein will be made. This is important because the types of proteins that a cell has determines what functions it can carry out

Constitutively expressed genes

Genes that are expressed all the time

An example is the genes that code for ATP synthase

Regulated genes

Genes that are expressed only when needed.

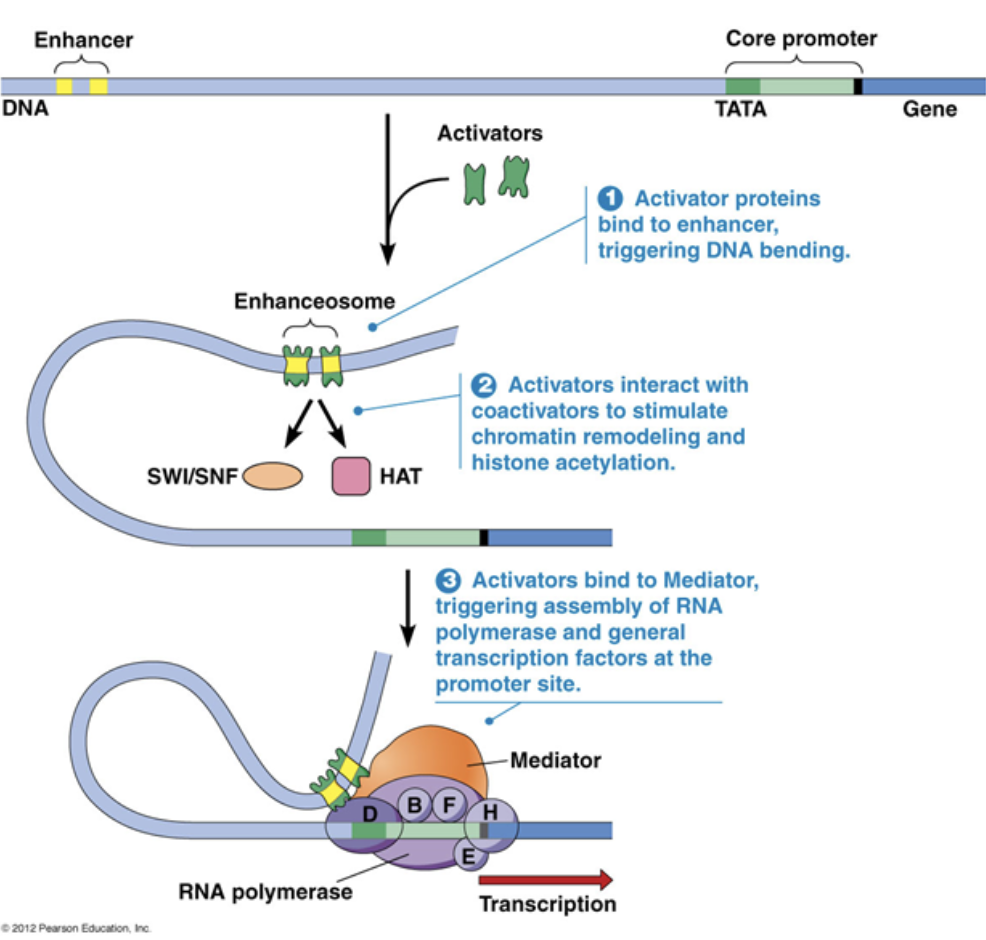

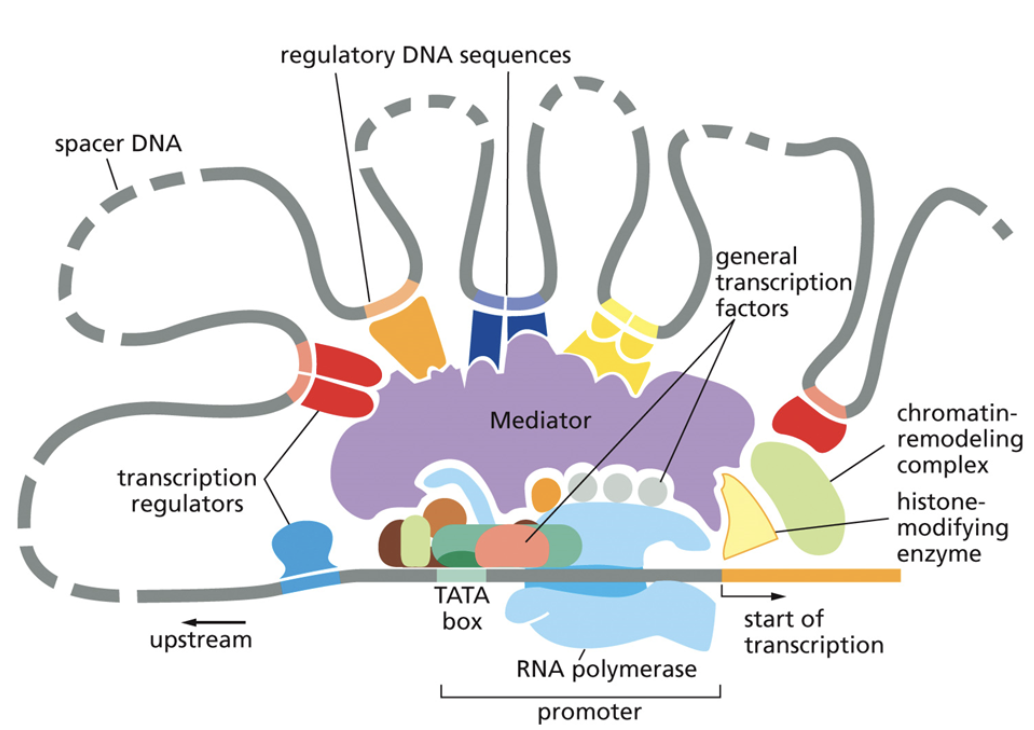

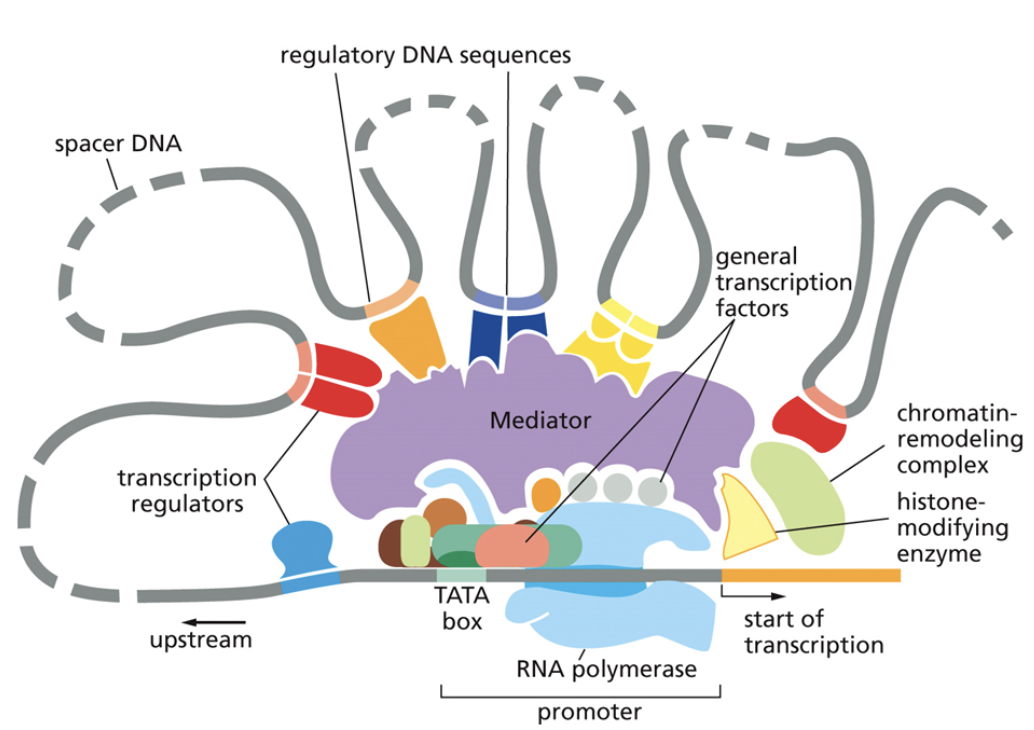

Cis factor

Tells RNA polymerase which genes to express

Exist on the same chromosome as the gene of interest

If many genes have the same cis factors, their expression can be coordinated together, whenever the right trans factors are available

Trans factor

Also called transcription factors

Tells RNA polymerase which genes to express

Do not exist on the same chromosome as the gene of interest. They are proteins that recruit RNA polymerase to the right place at the right time

Bind to cis factors with specificity

One trans factor can do multiple jobs in turning on many genes as long as they all have the same cis factors

How much of a gene is transcribed depends upon the combination of trans factors that are available and how many are binding at one time

Some transcription factors activate other transcription factors, leading to cell differentiation. As genes are turned off and on, different proteins are made, which contribute to a cells identity

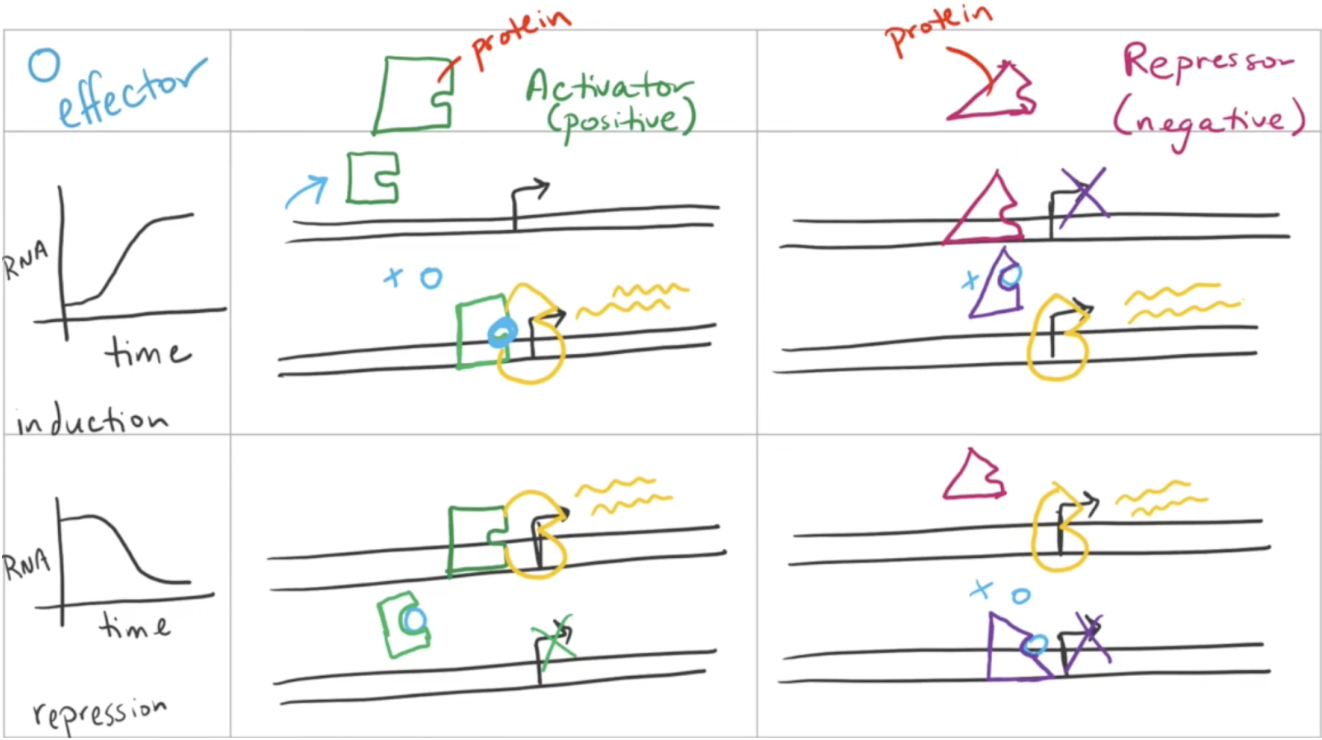

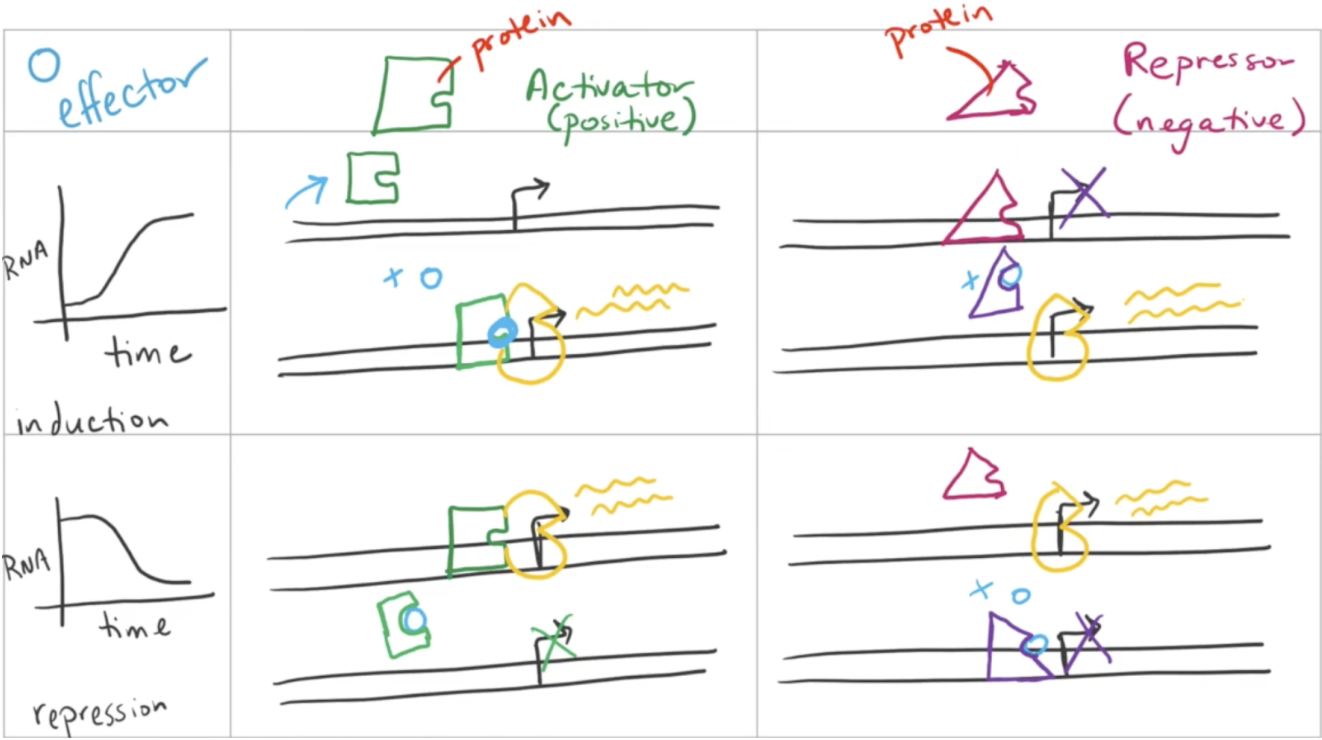

Positive regulation

The addition of a repressor/activator to induce/repress transcription

If the activator and repressor are bound at the same time, the repressor will win and transcription will not occur

Must be induced by an effector molecule that changes allostery

Negative regulation

The subtraction of a repressor/activator to induce/repress transcription

If a repressor is simply removed without the addition of an activator, transcription will occur very slowly

Must be induced by an effector molecule that changes allostery

Where are the 4 places genes can be regulated?

The cell can regulate transcription. It does so using cis and trans factors, as well as activators and repressors

The cell can modify gene expression through RNA processing. For example, if RNA has a short polyA tail, it will get degraded in the cytoplasm pretty quickly. Just because RNA is transcribed, doesn’t mean it will be used to make proteins.

The cell can regulate how much RNA is translated. It does this through Micro RNA (miRNA) and small interfering RNA (siRNA).

The cell can regulate which proteins are functional through post-translational modifications OR through regulating where proteins end up. A protein at the wrong cellular location will not be functional

What are the 4 features of epigenetic regulation?

No changes to DNA structure/code

Heritable through mitosis

Reversible, especially in meiosis. Traits are passed from cell to cell, but not from parent to offspring

Responsive to the environment. Cells can change gene expression quickly as needed

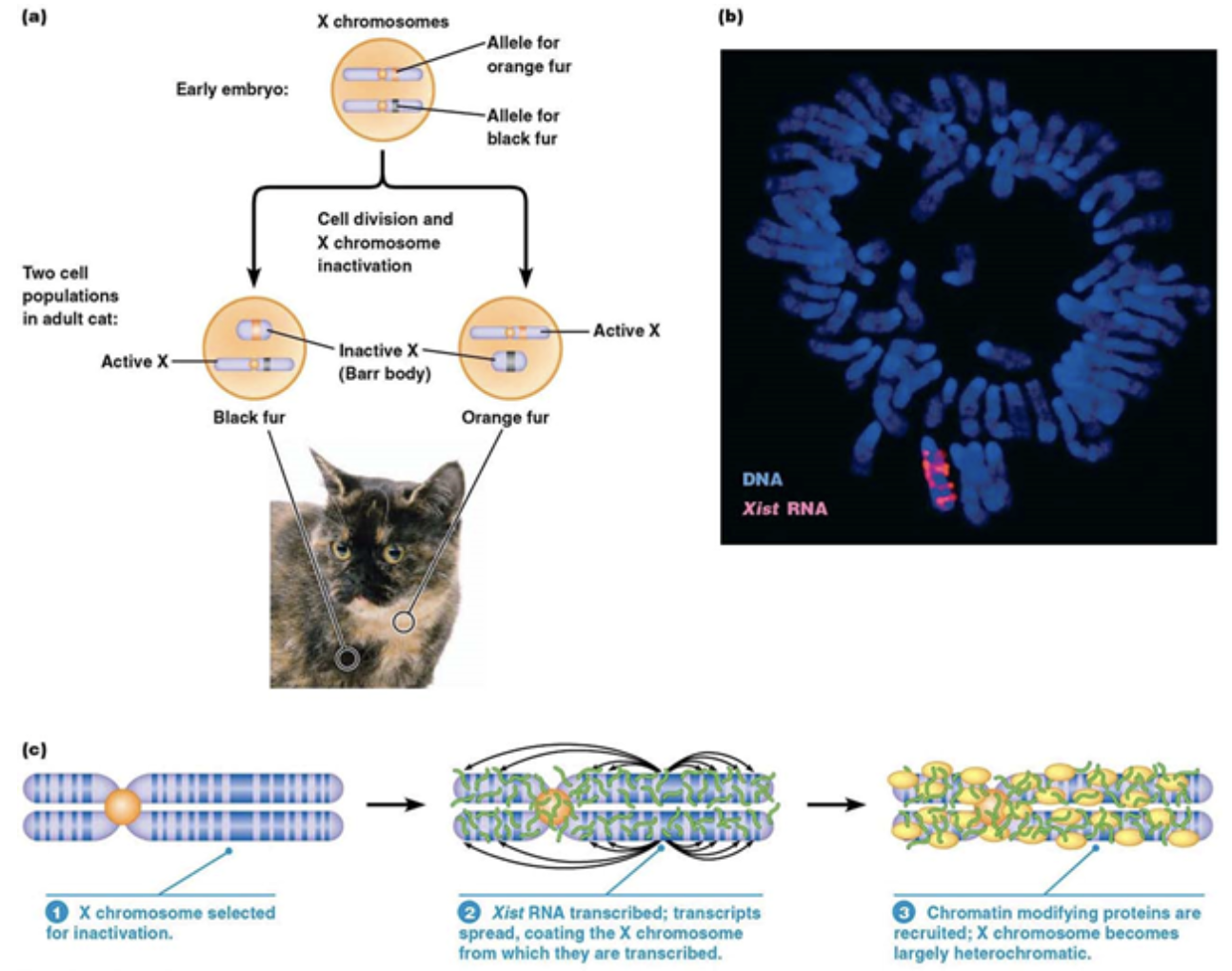

X inactivation

An epigenetic, structural change to the genome (but NOT DNA)

In mammals that have 2+ X chromosomes, it’s important that they don’t express too much of the RNA or proteins that are encoded in those chromosomes. Mammals “turn off” 1+ X chromosome(s) through X inactivation

Calico cats “turn off” one X chromosome early in their development, which are also linked to fur color, but not necessarily the same chromosome every time in every cell. The result is patches of cells that are black, those cells have the orange fur gene repressed, and patches of orange, those cells have the black fur gene repressed

This process occurs from a long RNA, called Xist, being transcribed and recruiting histones. The histones compact the genes on that chromosome even more until none of the genes on that chromosome are going to be expressed

How does changes to the nucleosomes position and structure change gene expression?

This is a type of epigenetic regulation

The hyperlocal position of nucleosomes determines where proteins can access DNA, including proteins that are necessary for transcription

A regulatory region of DNA where protein might bind can be obscured by a nucleosome exactly on top of it

If another protein binds to a region close to said nucleosome, it can bring along enzyme activity that removes the histone away from the DNA and exposes the protein binding site underneath.

That binding site previously covered by a nucleosome can yield a protein that then activates other enzymes that remove other nucleosomes, eventually making a whole area accessible for transcriptional regulation

Post-translational regulation

Regulation that occurs after translation of histone proteins.

Usually involves the chemical modification of histone proteins which alters the interaction between those proteins and DNA

Post-translational modifications act as “post it notes” to remind the cell of which “recipes” it wants to read very often

Histone acetyl transference (HAF)

A type of post-translational regulator

Adds an acetyl group to Lysine tails of a histone. This neutralizes the positive amine group on the histone

DNA is negatively charged, so adding this acetyl group reduces the interactions between histones and DNA. This “loosens” DNA and makes it readily transcribable.

Histone deacetylase complex (HDAC)

A type of post-translational regulator

Returns the positive charge back to Lysine on a histone by removing an acetyl group (the opposite of HAF).

DNA is negatively charged, so removing an acetyl group makes DNA and histone interactions increase. This makes DNA less accessible for transcription.

Methylation of histones

A type of post-translational regulator

Adds a methyl group to histones. This doesn’t change the charge, instead it provides binding sites for other proteins, some of which are activating, and some of which are repressing

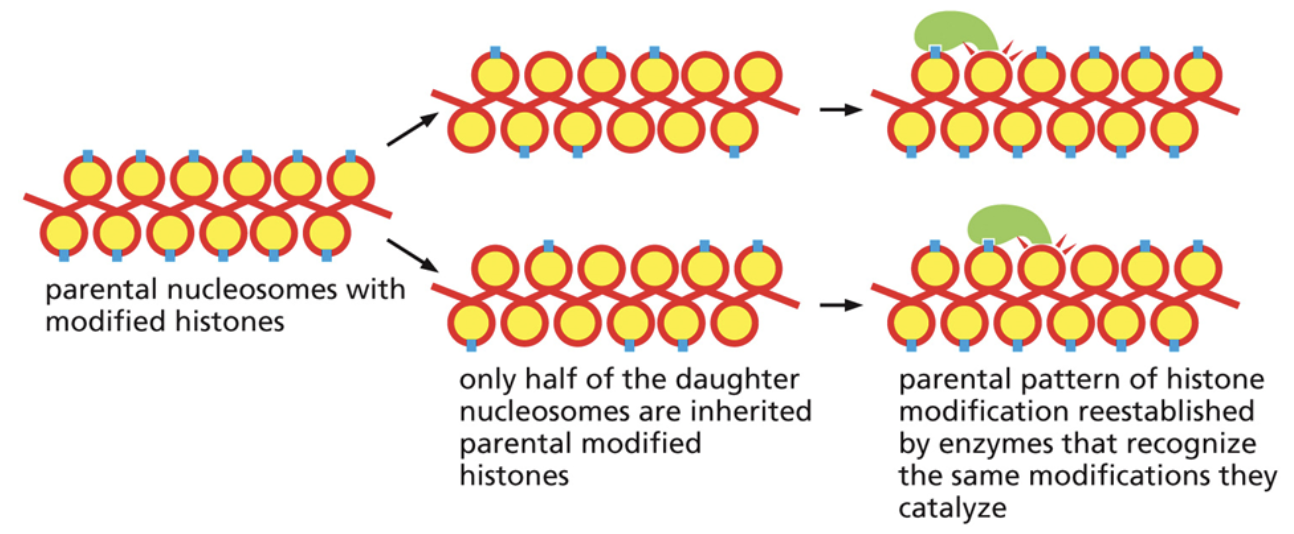

How are histone modifications/post-translational modifications replicated after cell division?

During cell replication, some of the histones will go to each of the two daughter strands. Only half of the daughter nucleosomes are inherited parental modified histones

There are proteins that can bind to modified histones, read the modifications that were there, and place the modifications on nearby histones

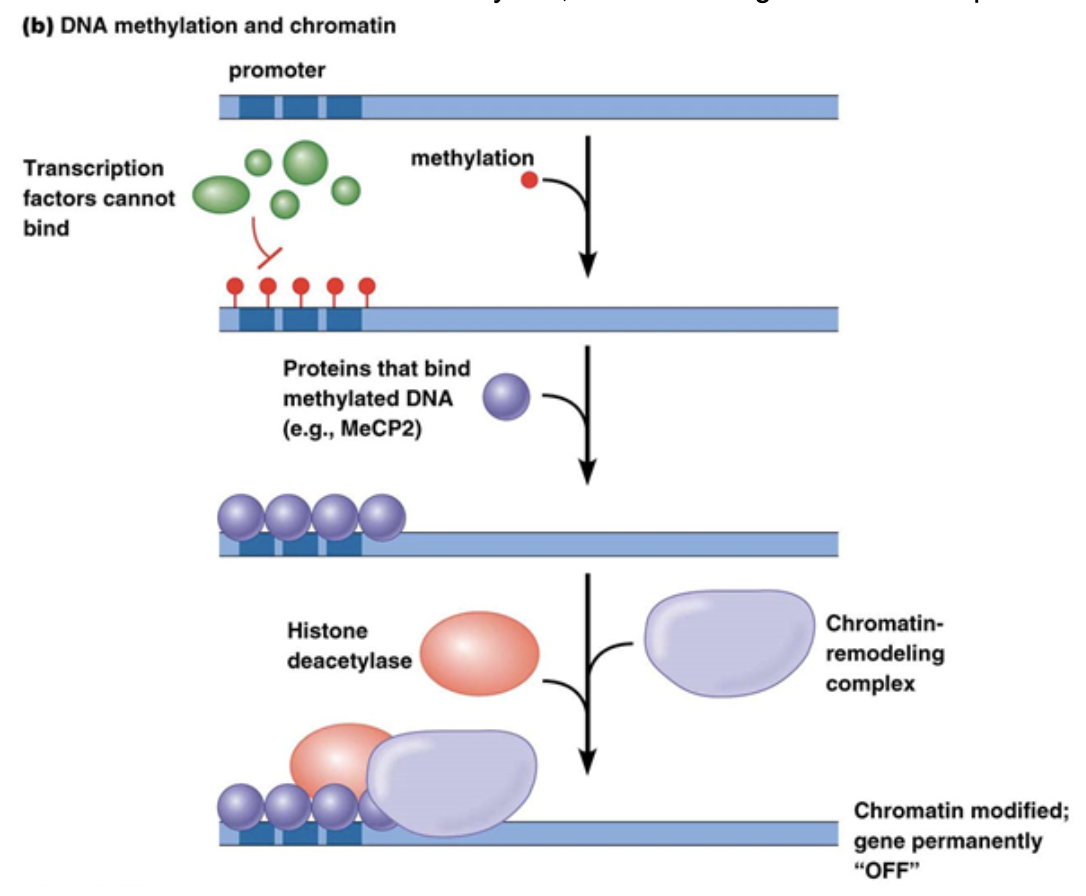

Methylation of DNA

This generally occurs in Eukaryotes on cytosine bases. It generally leads to gene repression

Commonly occurs on CpG regions of the genome. P stands for the phosphodiester bond between C and G

Methyl binding to C’s changes the binding potential for DNA-protein interactions. In many cases, it increases binding potential of repressor proteins, like histone deacetylase, which makes genes more compact.

Can be replicated after cell division. This is also because DNA replication is semi-conservative. Parent strands maintain their methylation even when bound to newly synthesized strands. Methylation is read and placed on the palendromic C’s of the newly synthesized strand so you end up with the same methylation on both strands after replication

Core promoter

A type of cis factor

Closest to the transcription start site

The TATAA box that begins transcription

Only general transcription factors bind to it

Cannot be moved because it would also move the binding site for general transcription factors, which will then change where RNA polymerase is recruited.

Proximal promoter

A type of cis factor

Immediately upstream of the core promoter

Regulatory transcription factors bind to it

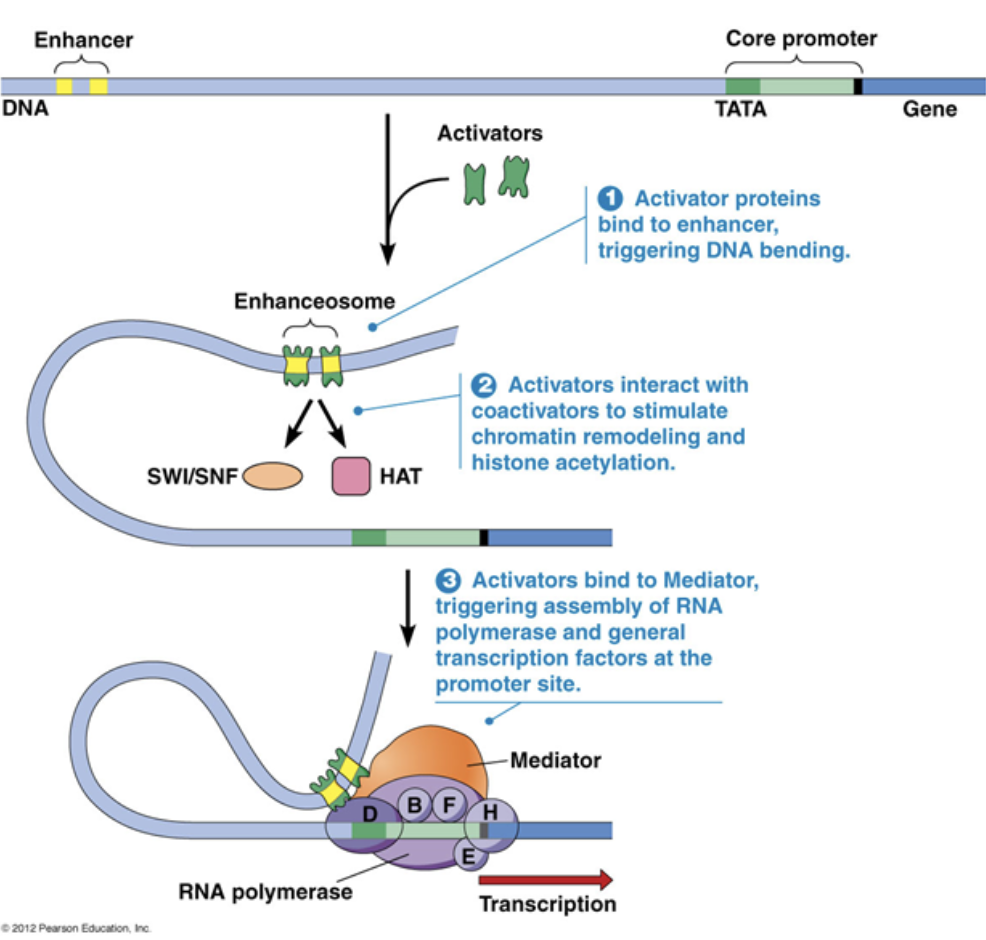

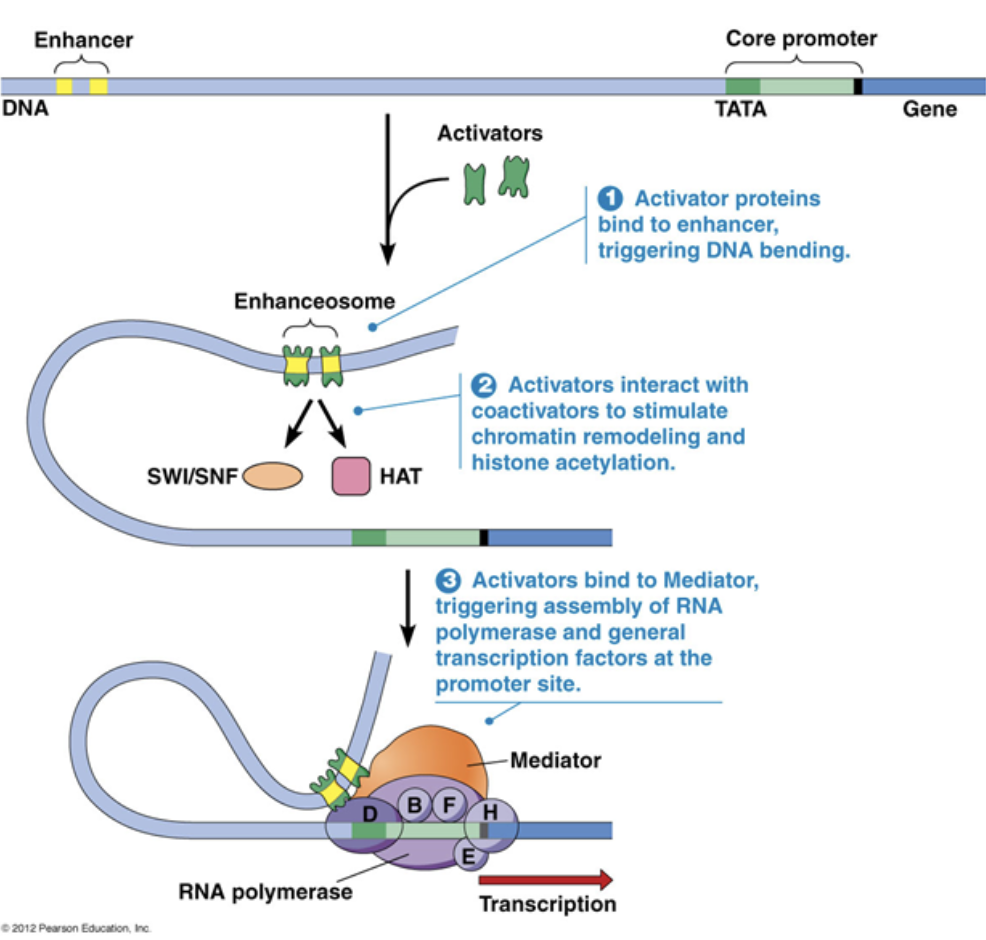

Distal promoter

A type of cis factor

Far upstream of the core promoter, 100s-1000s of base pairs away

Distal promoters can be very far away because DNA is flexible and can loop in 3D toward the core promoter

They can be enhancers, which are bound to activators. They can also be silencers, which are bound to repressors. Only regulatory transcription factors bind to it

A small amount of transcription can occur with just the core promoter, but transcription rates increase by A LOT with the presence of an enhancer

General transcription factor

A type of trans factor

Bind to the core promoter and recruit RNA polymerase to begin transcription

General transcription factors are necessary for ALL transcription that occurs

TFIID

A general transcription factor

Binds to the TATAA box and assists RNA polymerase II

TFIIH

A general transcription factor

The Helicase that opens up the DNA so it can be transcribed

Regulatory transcription factor

A type of trans factor

Influences the stability of RNA polymerase binding

Activators/repressors are regulatory transcription factors. Activators increase the binding affinity of RNA polymerase, while repressors decrease the binding affinity of RNA polymerase

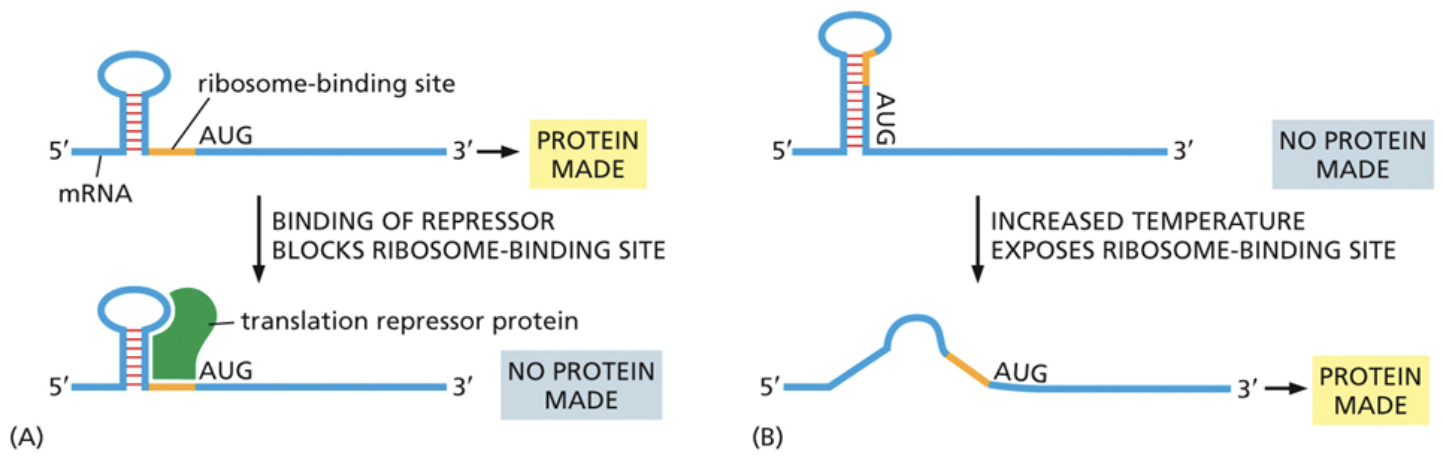

Which ways can ribosomal assembly be prevented as apart of translational gene regulation?

The ribosome binding site can be just downstream of a secondary stem loop structure. The stem loop structure can provide a binding site for translational repressors that prevent the ribosome from binding there

The ribosome binding site can also be tucked into the stem loop itself. In this confirmation, the ribosome is unable to bind. An increase in temperature can cause the stem loop to flatten and expose the binding site, allowing the ribosome to bind

How do miRNAs regulate gene expression during translation?

When double stranded miRNA is exported out of the nucleus, a protein called RISC chooses a miRNA strand to bring to mRNA

If the miRNA strand is fully complementary to the mRNA, it signals a nuclease to degrade the mRNA and prevent future translation

If the miRNA strand is only partially complementary to the mRNA, it prevents a ribosome from binding to that mRNA, rather than degrading it. This serves as a temporary inhibitor of translation

How do cells regulate how quickly mRNA is degraded?

By removing the 5’ cap so nucleases can recognize that end of the RNA and degrade it

By shortening the polyA tail so the nucleases have to cleave less of it off during RNA degradation

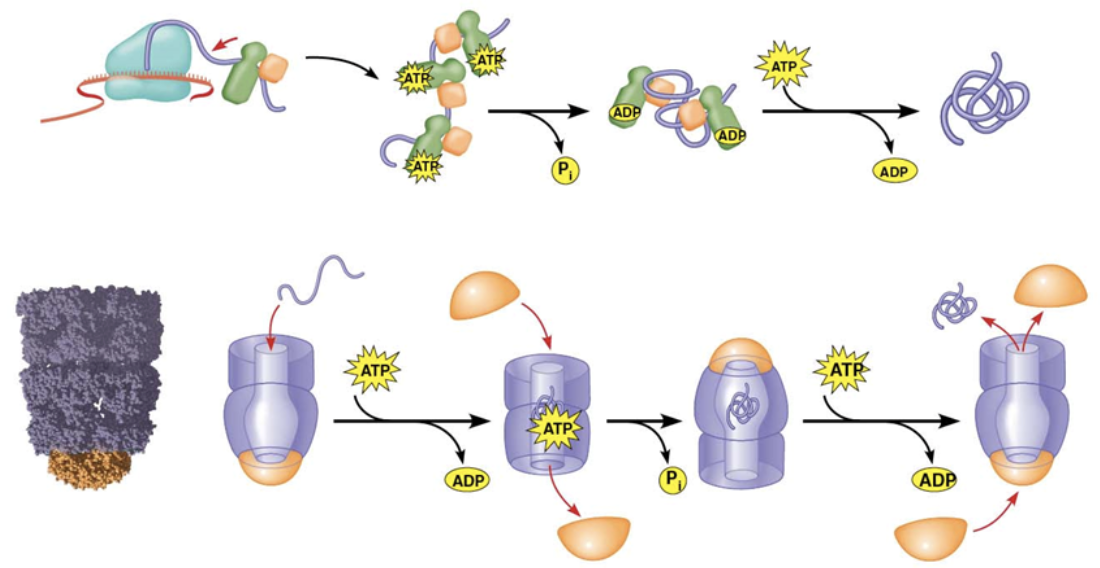

Chaperone

The protein that emerges from the ribosome may or may not be the most effective version of that protein. This is because portions of the protein that are translated first get folded before the rest of the protein gets translated.

Assist in protein folding, NOT by folding them, but instead by UNfolding them so improperly folded proteins can try again.

They use ATP to break chemical bonds

They can also form complexes that can allow the protein to fold in a closed environment

Glycosylation

A type of post-translational modification

The addition of sugars to a molecule

An example is O-linked glycosylation, which tells cargo where to go from the Golgi

Alkylation

A type of post-translational modification

The addition of a hydrophobic hydrocarbon group to a molecule

An example is the alkylation of a lipid anchor in transmembrane proteins so it can hold the protein in place by interacting with hydrophobic fatty acid chains

Polymerization

A type of post-translational modification

Quaternary structures coming together to form a fully functional protein

An example is nucleosomes forming, made up of histones and DNA

Phosphorylation

A type of post-translational modification

The addition of a negative charge to a molecule

An example is Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) activating each other through the addition of phosphate groups after a ligand binds to a receptor.

Acetylation

A type of post-translational modification

The neutralization of positive charges

An example is the post-translational modification of histones, which adds an acetyl group to nucleosomes, causing them to loosen

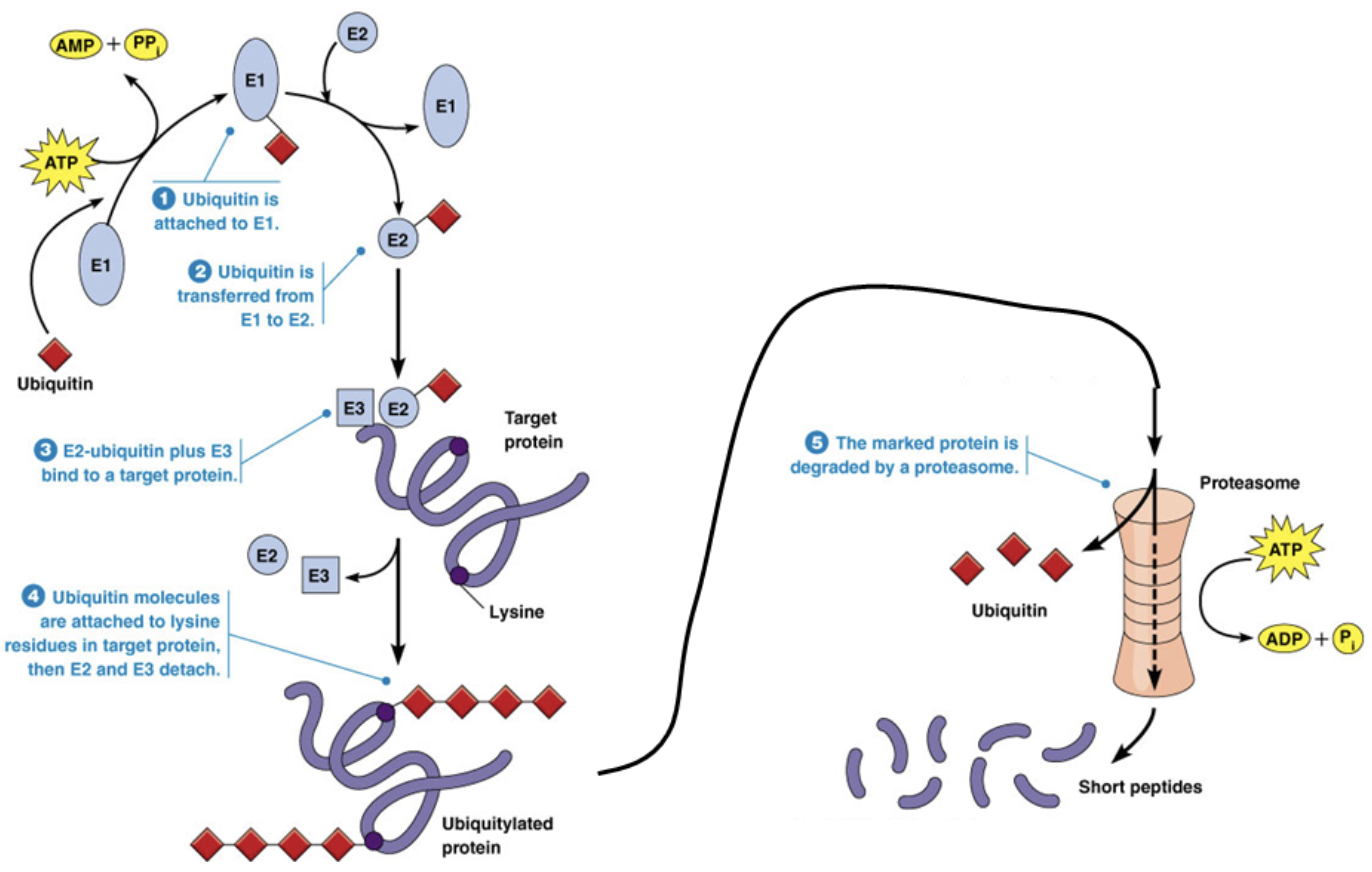

Ubiquitylation

A type of post-translational modification

The addition of small peptide groups to signal a protein for degradation

Proteasome

A molecule that degrades proteins after they’re marked by ubiquitin

A “blender” with proteases on the inside of it. Proteases cut proteins into short peptides that can be further degraded to amino acids for recycling or to be lost as waste

The proteasome breaks peptide bonds between amino acids using hydrolysis reactions. You can break proteins with the proteasome by adding water

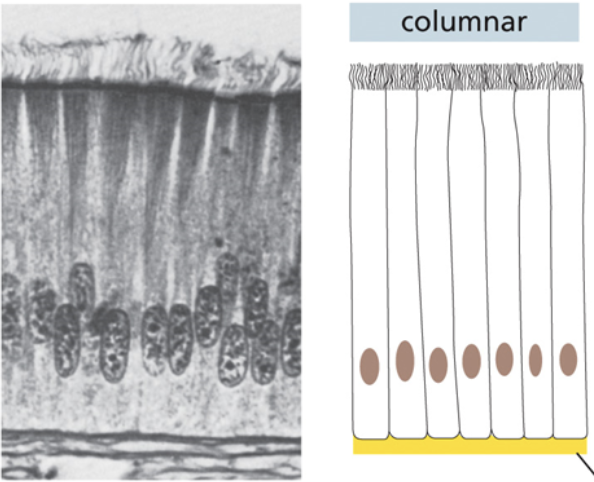

Columnar tissue

Cells are attached to each other along the vertical axis

Individual cells are long, vertical and skinny

Squamous tissue

Individual cells are thin and horizontal

Cells form a singular flat layer

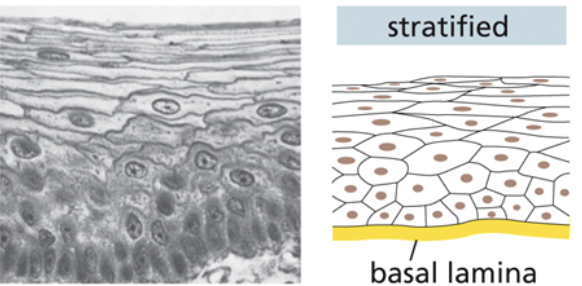

Stratified tissue

Individual cells are a random size and shape

Cells form flat, long, and thick layers that pile atop each other

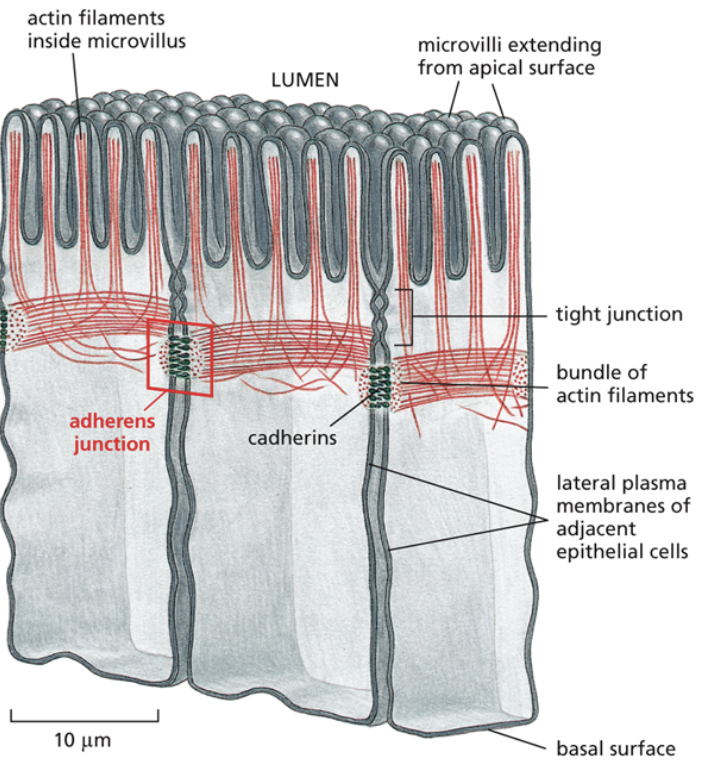

How and why do tissues form tubes and villi?

Cells can fold down and invaginate. Eventually those cells can roll up to form a tube that things can go into. Many organs function in this way, and are in themselves tubes, like intestines

Lumen shapes maximize surface area so that the cell has more access to nutrients that are in the extracellular matrix

OR cells could use that surface area to secrete molecules inside hollow spaces

How are tissues and junctions formed, in general?

One cell with a transmembrane protein connects and dimerizes with a similar transmembrane protein coming from another cell

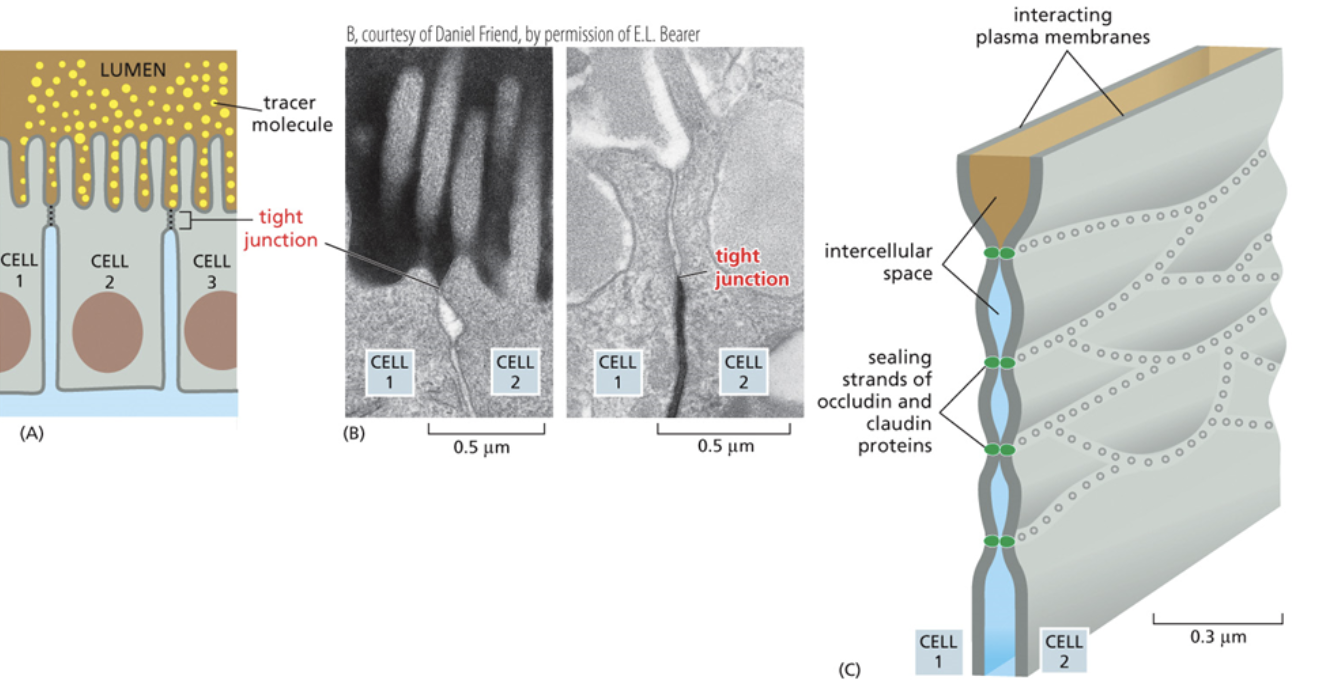

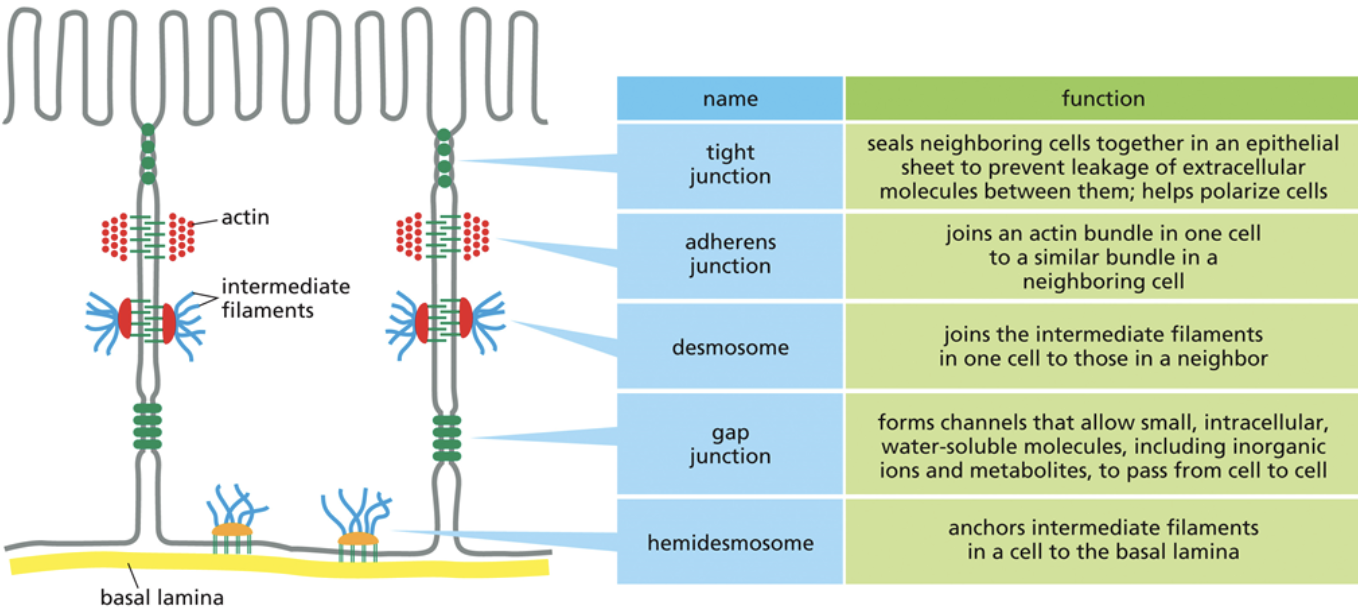

Tight junction

The smallest junction in that there is the least amount of space between two cells

Tight junctions are so small that transmembrane proteins from another cell can pierce through the cell membrane of adjacent cells

This barrier is so tight, even water that is flowing up into the space between cells cannot pass

Clodin

A protein that builds tight junctions

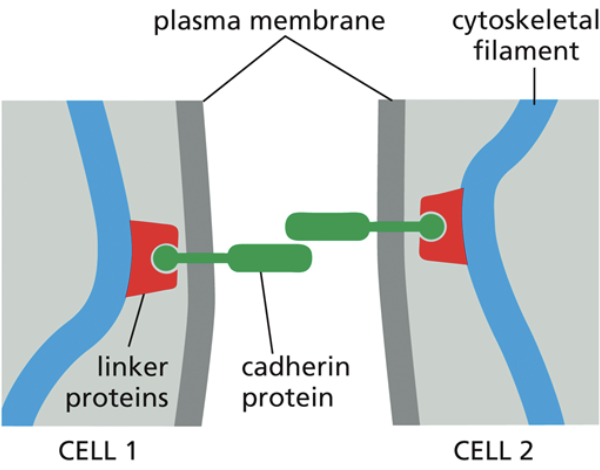

Adheren

A junction that link two cells together loosely, or link to other cell layers

The second smallest junction, in that there is more space between cells than in tight junctions.

Cadherin

A protein that makes up adheren junctions

Linker proteins connect actin to cadherin, which is a transmembrane protein interacting with the transmembrane protein of another cell. That makes it so if you were to pull on one cell, the other cell would have to come with it too

Cadherins have different varieties and are specific and only bind to cadherins of the same type when creating junctions between cells

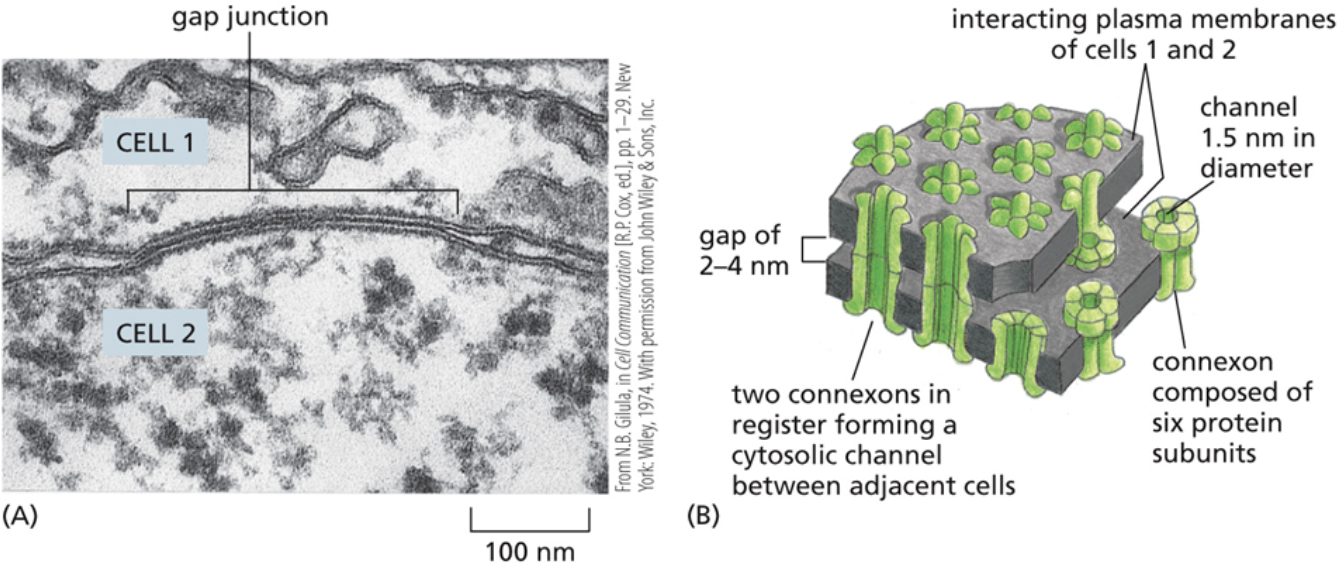

Gap junction

A junction that allows solutes and water to move directly between cells

The largest junction, there is the most space between two cells

They essentially make a tube that goes from one cell to another. Water and solutes that pass through gap junctions never come into contact with the other cells extracellular matrix

Connexin

A protein that makes up gap junctions

When they form a larger complex that makes up the tube, they’re called connexons

Why might a tissue have multiple kinds of junctions?

Each junction has its own unique function

Having varying junction types allows for one part of a tissue to have more water/solutes than another part of the tissue

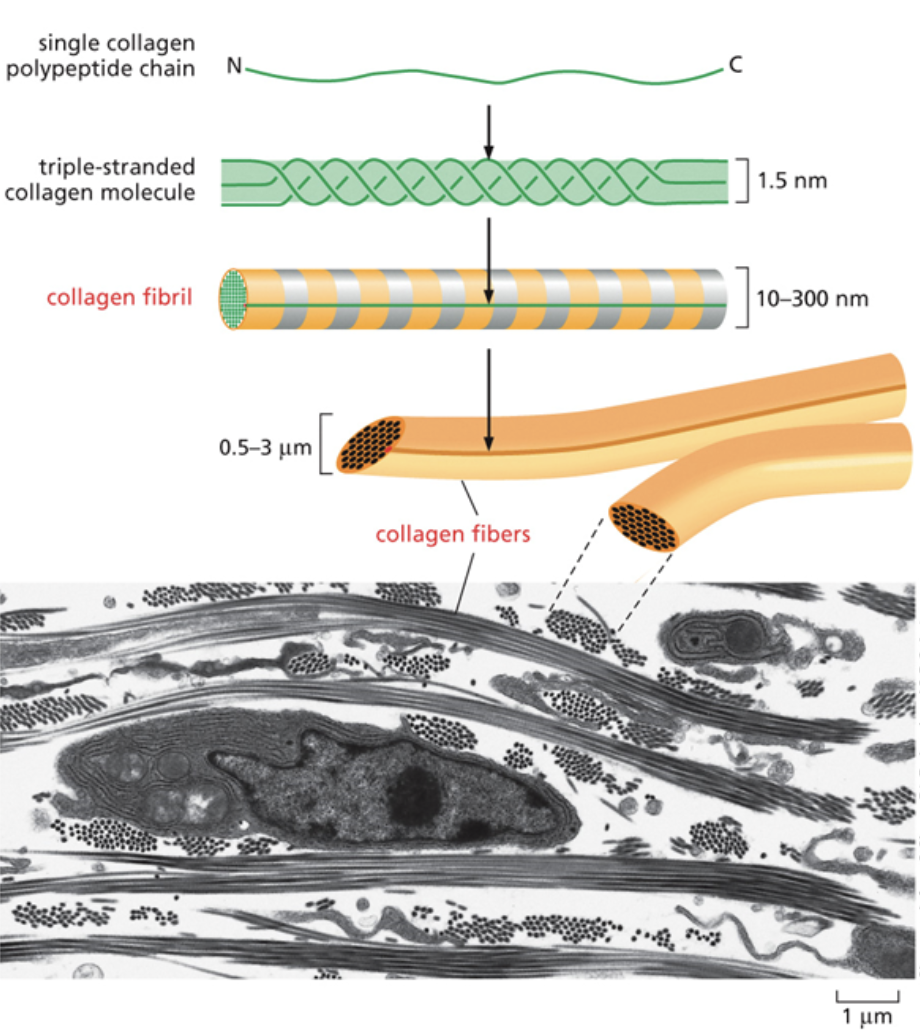

Collagen

One of the main molecules that make up the ECM

It’s the most abundant protein in the human body. It provides strength to the ECM.

Makes up bones and cartilage

Made up of a triple helix with three collagens wrapping around each other. Helices then stack together to form rods

Collagen exists as a long, tube like structure in the ECM

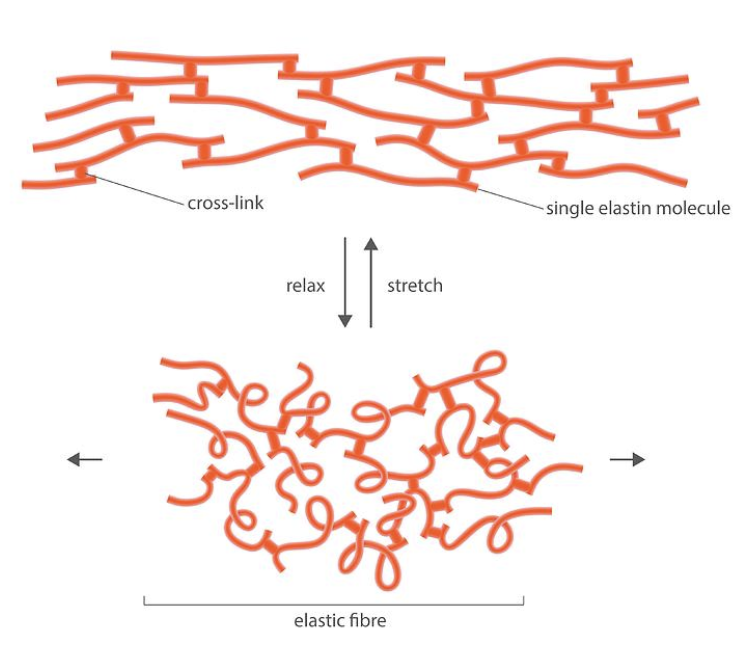

Elastin

One of the main molecules that make up the ECM

It provides stretch to the ECM

The covalent bonds between strands of elastin is called a covalent crosslink

When elastin is stretched, it forms a taut and weblike structure. As soon as elastin is relaxed again, covalent bonds pull it back into its curly and random conformation.

When you grab skin on your arm and pull it, it snaps back into its original conformation as soon as you let go. This is because your skin has a lot of elastin in it