Week 8 - Emotion and Accent Perception

1/38

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

39 Terms

How did Plato define emotion?

Emotions are to be distrusted as they arise from the lower part of the mind.

Emotions prevent rational thought

How did Darwin define emotion?

Emotions can be recognised in other species.

Have evolved to serve important function = survival and social bonding.

What are the basic components that define emotion?

Cognitive appraisal of arousing event

Physiological changes (e.g. HR, breathing)

Increased readiness to act

Subjective “sense of feeling”

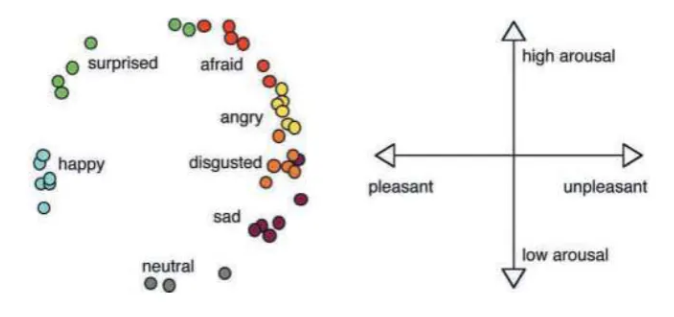

What is the Circumplex Model (Russel, 1980)?

Proposes that all emotional states arise from just two core dimensions: valence (pleasantness vs. unpleasantness) and arousal (intensity/energy).

Emotions are mapped onto a circular (circumplex) space, where valence is the horizontal axis and arousal is the vertical axis, allowing any emotion to be described as a combination of these fundamental sensations, rather than discrete, separate emotions.

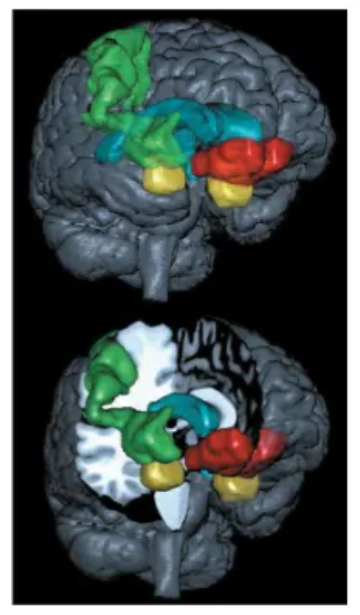

What are the main brain structures involved in emotion?

Amygdala (yellow)

Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (red)

Somatosensory Cortex (green)

Ventricles for orientation (blue)

V1 and FFA / OFA

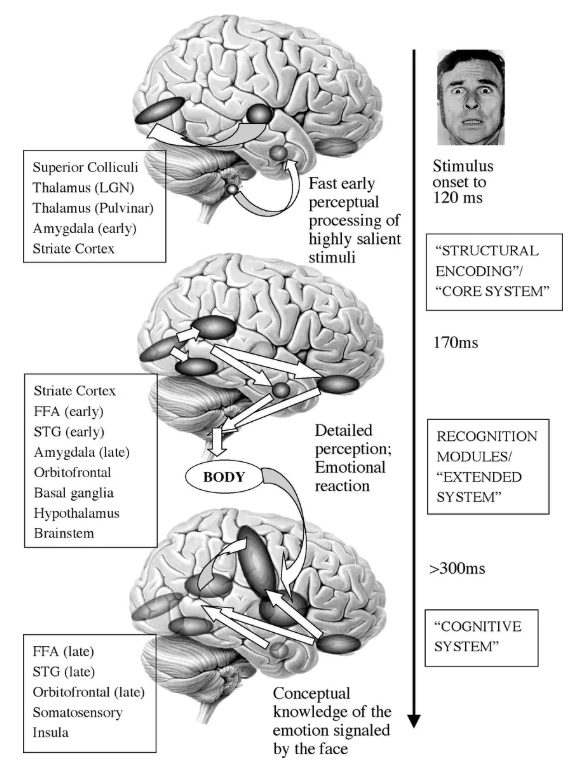

What is the course of emotion processing?

Emotional stimuli (like faces) follow a rapid, parallel pathway involving subcortical (amygdala, superior colliculus) and early cortical (striate cortex, fusiform face area) areas for quick threat detection, alongside slower pathways to prefrontal cortex (PFC) and somatosensory cortex for deeper, conscious evaluation and regulation, highlighting the amygdala's crucial role in fast emotional salience detection and the PFC's role in context and control, with distinct timing for different emotions like fear versus happiness.

What are two things that contribute to the ‘sound of emotion’?

Speech prosody

Vocal expression

Vocal modulations due to emotional arousal are easily and quickly picked up by listeners.

Hard to fake.

Important in understanding meaning in speech

Vocal emotional cues reflect communicative intentions.

Also a powerful “tool” in modifying meaning

Imagine this sentence said in a fearful, happy, sad tone:

“I will leave the room now but I’ll be back later”

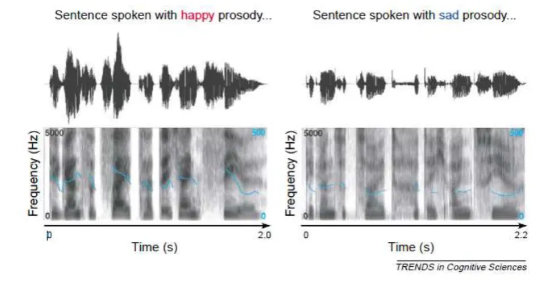

What is prosody?

Prosody → rhythm, stress and intonation of speech

Conveyed as modulations in amplitude (loudness), timing (speech rate), fundamental frequency (pitch) and “voice quality” (smoothness).

Some emotions are believed to have a unique physiological imprint they are proposed to be expressed in a unique manner, e.g. happy (high F0 etc) vs sad (low F0 etc).

Changes in voice production are result of arousal mediated changes in heart rate, blood flow and muscle tension which all affect the shape, functionality and sound of the voice production system.

Babies can differentiate between voices before they can understand speech.

Children can produce the melody or intonation of speech before they can produce two-word combinations (also remember “hover the talking seal”).

We can understand cartoon characters even though they do not speak.

We can tell the emotional “status” of a speaker from their voice.

Hugely important for social interaction.

Understanding a vocal emotional message requires analysis and integration of various acoustic cues (e.g. pitch and rhythm).

What has neuropsychology found about the right hemisphere and prosody perception?

The right hemisphere plays a critical and dominant role in the perception of emotional (affective) prosody.

Damage to specific areas in the right hemisphere often results in a condition called receptive aprosodia, where patients struggle to comprehend the emotional tone of speech, even if they understand the literal words.

Long-established and persistent notion: RH deals with emotional tone in speech.

Damage to RH is more detrimental to ability to recognise vocal emotional expressions than damage to LH.

Nice double dissociation with speech: Damage to RH can lead to “aprosodia” while damage to LH can lead to “aphasia”.

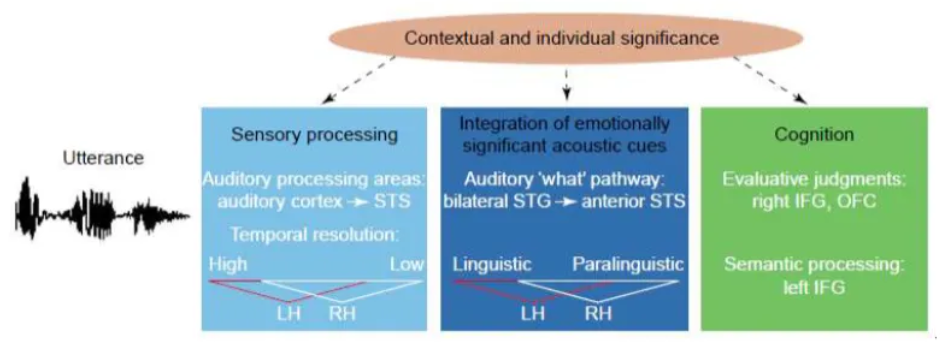

What is multi-step prosody perception?

A theoretical framework in cognitive neuroscience that describes how the human brain processes the non-linguistic elements of speech (prosody, e.g., tone, pitch, rhythm, stress) through a series of hierarchical processing stages to understand a speaker's emotions or intentions.

The process typically involves several stages, moving from basic auditory analysis to complex social cognition and decision-making, primarily involving brain networks in the right hemisphere.

Low-Level Acoustic Analysis (Early Stage): The initial step involves rapidly extracting basic acoustic cues from the speech input, such as fundamental frequency (pitch), amplitude (loudness), and duration. This occurs in bilateral auditory cortices.

Emotional Salience Detection & Representation (Intermediate Stage): These low-level cues are then integrated to determine the emotional significance or salience of the sound, building a preliminary emotional representation of the speaker's state. This process is thought to involve areas like the superior temporal sulcus and gyrus.

Higher-Level Cognitive Appraisal & Decision Making (Late Stage): The final stages involve deeper processing to derive the full emotional or intentional meaning of the input (e.g., distinguishing a statement from a question, or detecting sarcasm). This information is then used to evaluate social consequences and prepare a response. These processes are associated with higher-level brain regions, particularly the inferior frontal and orbito-frontal cortices.

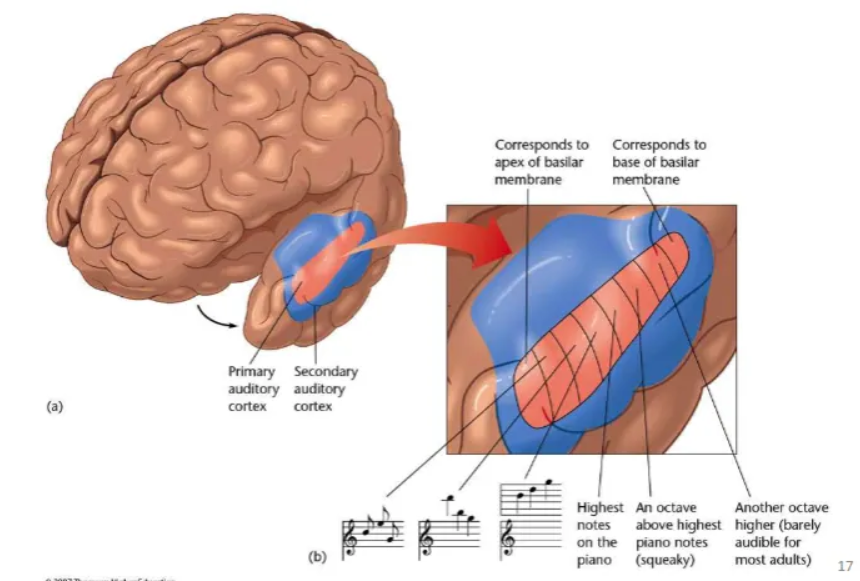

How does the brain process acoustic cues?

Follows a hierarchical organization through three main levels in the auditory cortex: the core (primary auditory cortex), the surrounding belt, and the more lateral parabelt regions.

Core Auditory Cortex (Primary Auditory Cortex, A1): This is the first cortical stage to receive direct input from the thalamus. Neurons here are organized tonotopically (based on sound frequency) and are highly responsive to simple stimuli like pure tones. This area decodes basic acoustic properties such as frequency, amplitude, and duration, which are the building blocks of prosody.

Auditory Belt Regions: These areas surround the core and receive inputs from it. Neurons in the belt are less precisely tonotopic and are more responsive to complex sound stimuli and patterns, such as pitch, melody, rhythm, and timbre. The belt acts as an obligatory second stage of processing, integrating the basic acoustic features from the core over a slightly longer time scale.

Auditory Parabelt Regions: The parabelt is a third level of processing, lateral to the belt region, and receives inputs from the belt. These areas are crucial for more integrative and associative functions, such as pattern perception, auditory object recognition (e.g., identifying a voice or a specific type of sound), and speech perception. Processing in the parabelt occurs over longer time scales compared to the core and belt, which is necessary for integrating acoustic cues that unfold over the duration of syllables, words, and phrases (the essence of prosody). The parabelt connects to regions in the temporal, parietal, and frontal cortices for further specialized processing, including sound localization and memory.

Belt and parabelt analyse frequencies and intensities of sound waves (both hemispheres).

Auditory processing areas in LH and RH differ in their temporal resolution.

LH has a finer temporal scale and is therefore better equipped for the analysis of rapidly changing auditory information.

RH better at pitch processing.

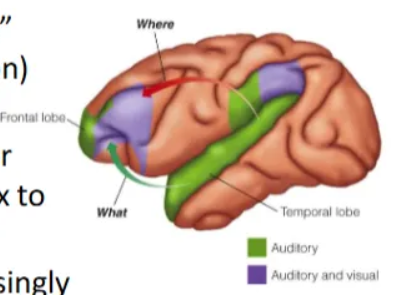

How does the brain integrate acoustic cues?

The brain integrates the acoustic cues of prosody (pitch, loudness, duration, and rhythm) through a dedicated network of bilateral frontotemporal brain areas that operate over a longer timescale than basic auditory processing.

This processing occurs in stages, from initial acoustic analysis to integration with linguistic and emotional context.

Emotional speech is a class of auditory object.

Auditory objects are processed in “what” (categorisation) and “where” (localisation) streams.

“What” stream particularly important for speech and reaches from auditory cortex to STS / STG.

Processing is believed to become increasingly complex and integrative as it progresses towards STS (from where it feeds to frontal lobes for higher order cognition).

Comparison between intelligible and spectrally rotated, unintelligible speech.

Similarly complex but no memory representation

Both activate left STG but only left anterior STG responds to intelligible speech

If you do the same comparison with non-linguistic vocal sounds you find right lateralisation

What is cognition (in relation to emotion)?

Interpretation of emotional input

E.g. “You idiot!” (can be harmless banter or an insult)

So in addition to understanding language content interpreting the tone of the utterance requires additional processing resources (particularly if tone contradicts verbal meaning).

Increased “effort” is reflected by increased activity in inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) for words spoken with incongruous vs congruous emotional prosody.

What is the three-stage working model of affective prosody?

Describes a cognitive architecture involving distinct stages of processing that are associated with specific brain regions.

The stages are:

Stage 1: Sensory Processing (Acoustic Analysis) The initial stage involves the bilateral analysis of the fundamental acoustic features of the incoming speech signal, such as pitch, intensity (loudness), duration, and rhythm. This processing primarily occurs in the auditory cortices.

Stage 2: Perceptual-Conceptual Integration (Access to ARACCE) In this stage, the extracted acoustic features are integrated and matched to a listener's stored expectations or "abstract representations of acoustic characteristics that convey emotion" (ARACCE). This process is thought to be lateralized to the right hemisphere, particularly involving projections from the superior temporal gyrus to the anterior superior temporal sulcus.

Stage 3: Cognitive Evaluation (Semantic Representation Access) The final stage involves the higher-order cognitive processing and explicit evaluation of the emotional meaning of the prosody. This includes assigning a semantic representation to the emotion (e.g., matching "happy" prosody with the word "cheerful") and integrating it with linguistic content. This stage is associated with activity in the right inferior frontal gyrus and orbitofrontal cortex, as well as interhemispheric processing involving the left inferior frontal gyrus for language integration.

What did Buchanan et al. find in relation to emotional prosody?

Using fMRI, they showed that the detection of emotional prosody is associated with increased activation in the right hemisphere (inferior frontal lobe and right anterior auditory cortex).

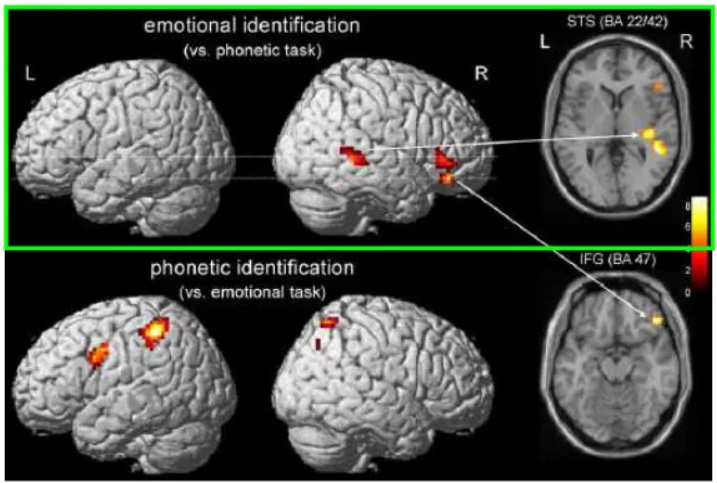

What was Wildgruber et al. (2005)’s fMRI experiment?

Designed to separate phonetic from affective prosodic components.

Emotionally neutral spoken sentences such as

“The guest reserved a room for Thursday” or

“Calls will be answered automatically”

Read with 5 different emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, fear and disgust).

Tested for recognition behaviourally prior to fMRI (all 90-95% accuracy except disgust (77%)).

2 tasks: classify the emotion; classify the vowel after the first ‘a’.

Found 2 areas associated with emotion identification: Right STS and right inferior frontal cortex. rIFC involved in emotion comprehension of both facial and prosodic cues.

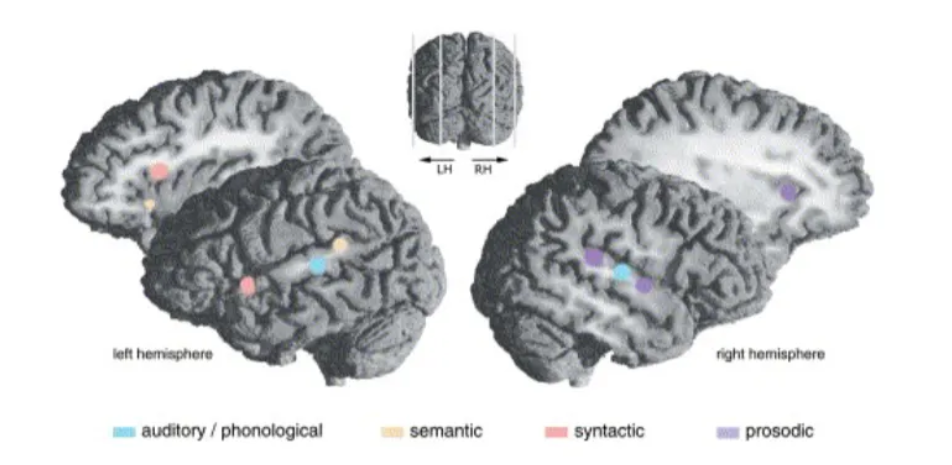

Give a summary of prosody research.

The recognition of emotion from prosody is not quite analogous to the recognition of emotion from facial expression.

Recognizing emotional prosody draws on multiple structures distributed between left and right hemispheres.

The roles of these structures are not all equal but may be most apparent in processing specific auditory features that provide cues for recognizing the emotion.

Despite the distributed nature of the processing, the right hemisphere appears most critical - in particular the right inferior frontal regions, working together with superior temporal region in the right hemisphere, the left frontal regions, and subcortical structures, all interconnected by white matter.

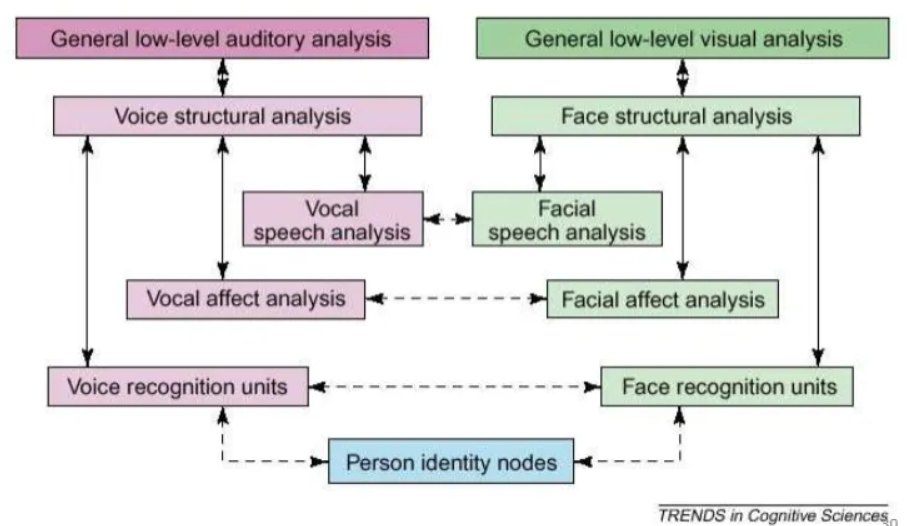

Explain how emotion in the voice is processed compared to the face.

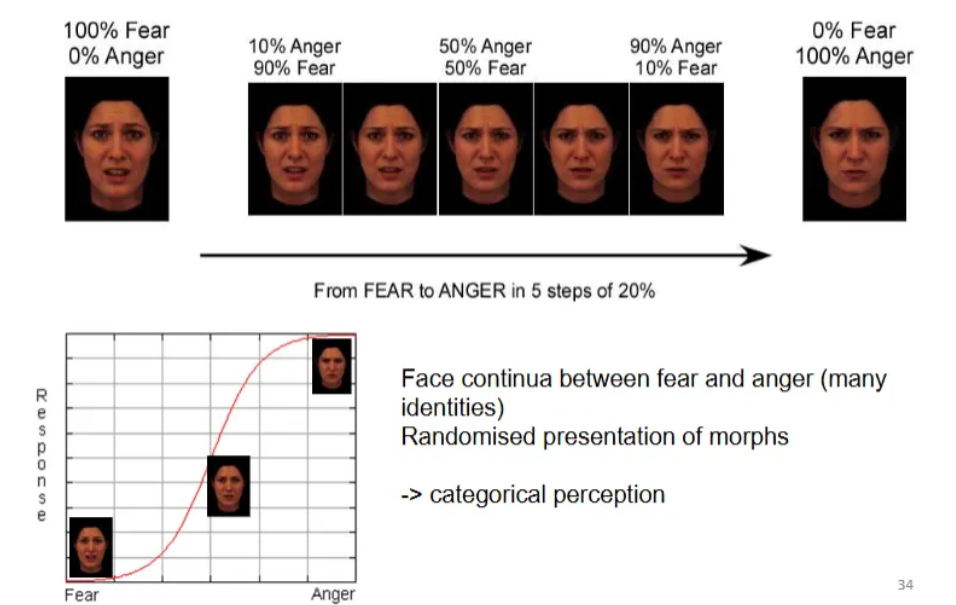

What is adaptation to facial expressions?

A perceptual phenomenon where prolonged exposure (adaptation) to one emotion (e.g., happy) biases the perception of subsequent, briefly shown faces, making them seem more like the opposite emotion (e.g., angry), revealing specialized neural populations for different emotions and how we adjust to emotional cues in social interactions.

It helps us detect novel emotional signals by fatiguing detectors for familiar cues, shifting our sensitivity to new information, and showing that emotion processing is fast and automatic.

What is adaptation to facial expressions using morphing?

Involves prolonged viewing of one expression (the adaptor) which then biases perception of subsequent ambiguous faces (morphs), shifting them away from the adaptor's emotion, creating a temporary "aftereffect".

For example, adapting to happiness makes faces seem sadder, showing the brain recalibrates its emotion detectors, suggesting opponent-process coding and distinct neural representations for different expressions, both identity-specific and general.

Morphing sequences, like happy-to-sad, are used as adaptors to reveal these shifts, demonstrating how our perception of emotional meaning changes after exposure to intense or dynamic emotional displays.

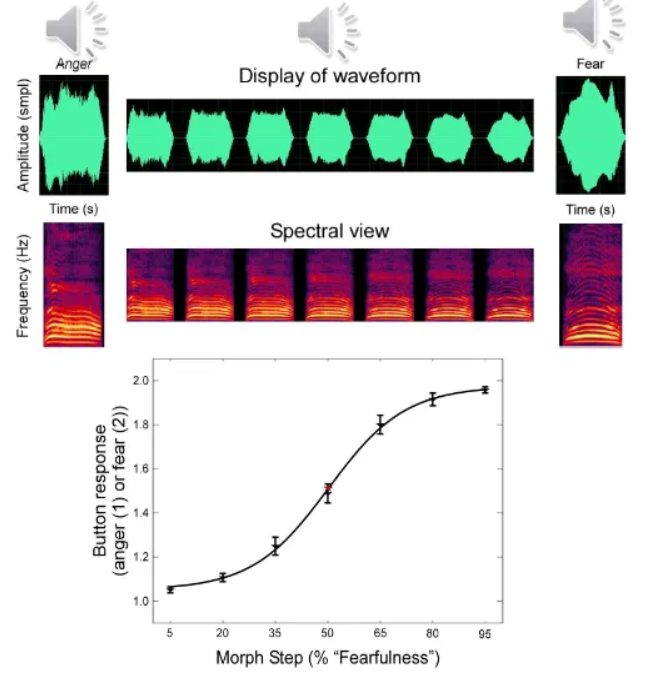

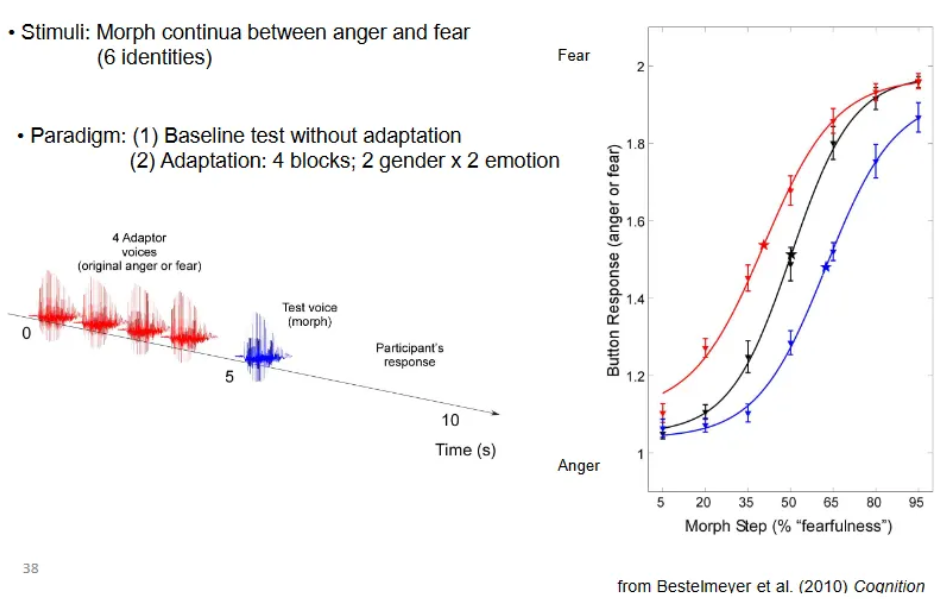

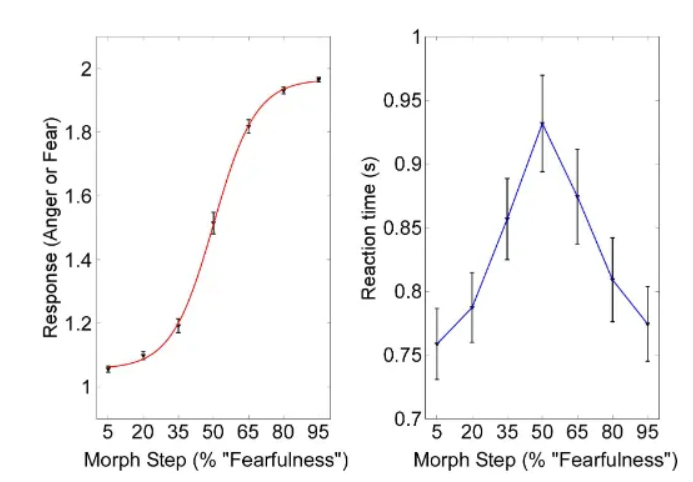

What did Kawahara et al. do with sound morphing?

Developed the STRAIGHT algorithm, a powerful voice manipulation and morphing tool that allows researchers to systematically and parametrically control acoustic features of sounds (like fundamental frequency, spectral envelope, and amplitude) to study the perception of emotion in voices.

What is adaptation to vocal effect?

A perceptual phenomenon where prolonged exposure to a specific vocal emotion (like anger or fear) biases our perception, making subsequent ambiguous voices seem more like the opposite emotion (e.g., angry-adapted voices sound more fearful), demonstrating how our brains adjust to emotional cues to better interpret new or unclear vocal expressions.

This process reveals a multi-stage model of emotion perception, involving low-level acoustic analysis and higher-level cognitive interpretation, with adaptation occurring at different neural levels.

What did Aguirre et al. (2007) do in relation to adaptation to vocal effect?

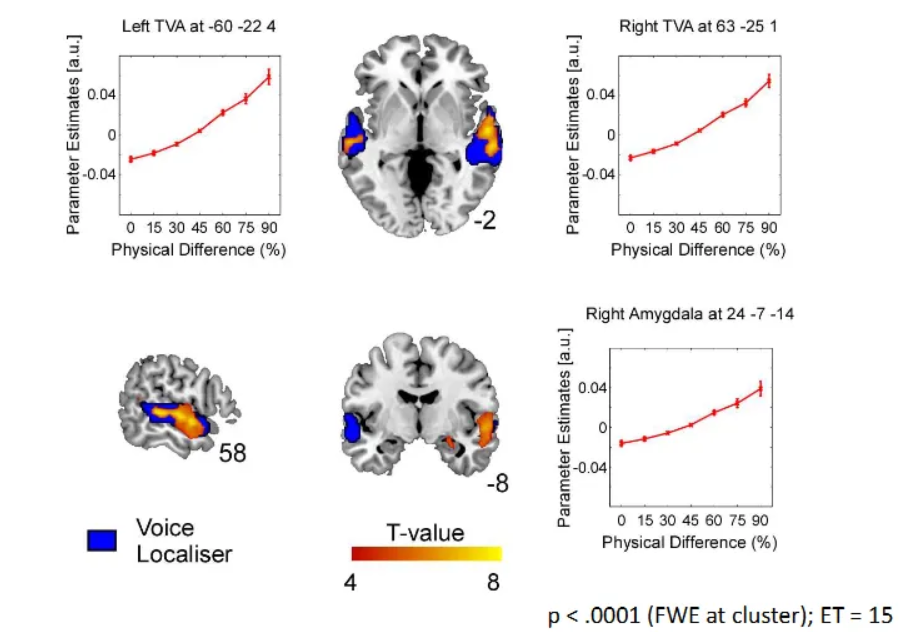

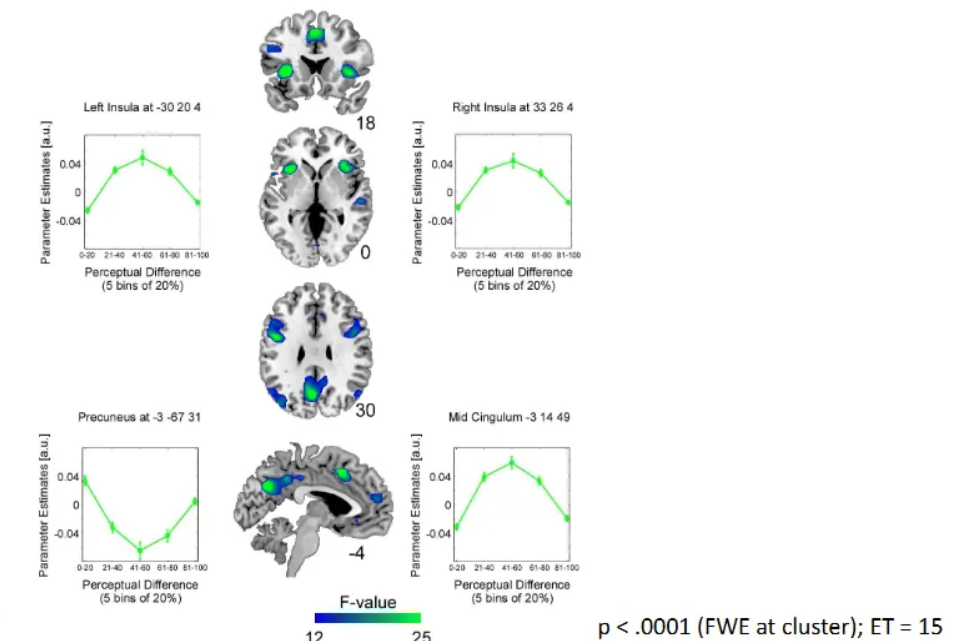

Used a "continuous carry-over design" (Aguirre, 2007) with functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to examine how the brain adapts to changes in vocal emotion (anger/fear morphs).

They found distinct neural networks: some areas (amygdala, auditory cortex) adapted to physical acoustic differences, while others (anterior insula, prefrontal cortex) adapted more to perceptual emotional differences, suggesting a multi-step processing of vocal affect.

Continuous Carry-over Design: Aguirre (2007) developed this design to present unbroken, serially balanced sequences of stimuli (e.g., vocal continua morphed between anger and fear).

Measuring Adaptation: By analyzing the neural response to a stimulus based on the one preceding it, they measured adaptation (reduced response) for similar stimuli, distinguishing it from physical vs. perceptual changes.

Multistep Perception of Vocal Emotion: Their work showed that processing vocal affect isn't a single step but involves separate brain regions:

Auditory/Amygdala: Respond to physical acoustic differences.

Insula/Prefrontal Cortex: Respond to abstract, perceived emotional differences, indicating a higher-level cognitive process.

Analysed fMRI data using correlations (between BOLD and other measurement of interest).

fMRI adaptation design: “Continuous carry-over” (Aguirre et al., 2007).

Sequentially presented; serially balanced presentation of stimuli

Analysed using correlations b/w BOLD and behaviour or acoustics.

Software orthogonalises regressors (i.e. variables of interest).

i.e. can remove variance explained by regressor 1 and see what is “left”

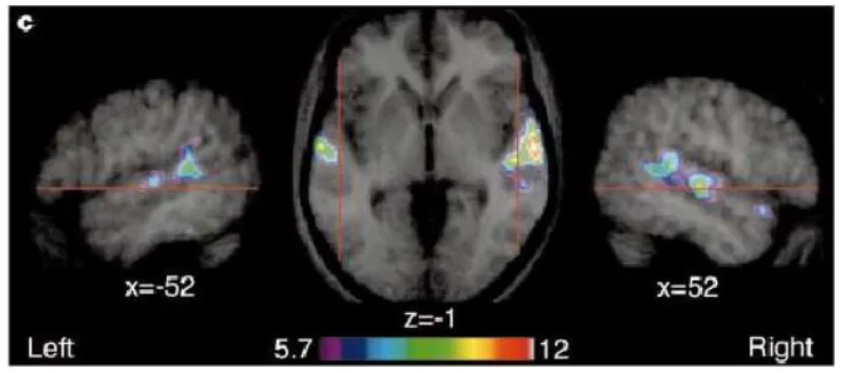

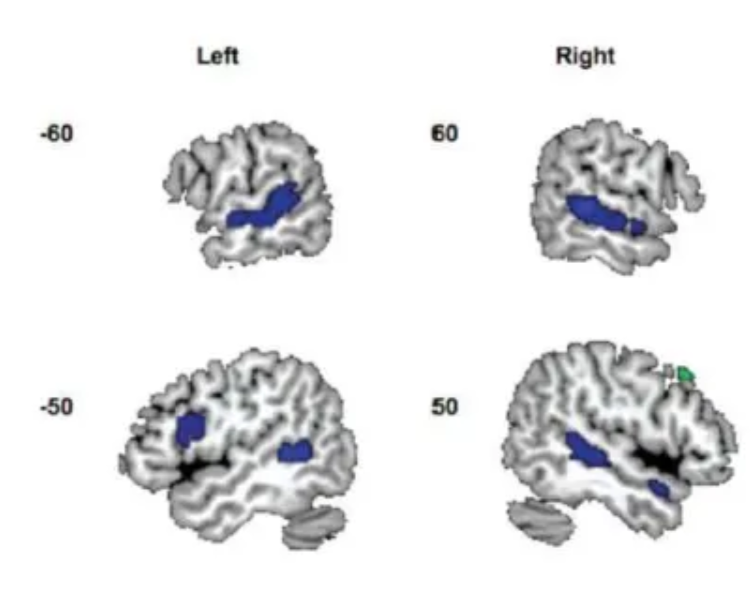

What physical differences did Aguirre et al. (2007) find?

What perceptual differences did Aguirre et al. (2007) find?

Give an overview of processing vocal effects.

Processing of vocal affect expressed in the absence of language seems to involve several stages:

Physical, acoustic differences processed in TVA and amygdala.

Perceptual differences processed in bilateral insulae, bilateral mid-frontal cortex and precuneus.

Schirmer & Kotz’s (2006) model is sort of true but:

Integration of emotionally relevant cues may involve subcortical structures.

Cognition involves more than just frontal lobe (i.e. insula, posterior cingulate).

Give a summary of vocal emotion perception.

Most of the research that has been done related to vocal emotion perception is confounded with speech.

Very little research on emotional paralanguage which plays an important role in social communication.

Vocal emotion perception is a hierarchical process involving multiple steps.

Context must (intuitively) affect how we process vocal emotions (and emotions in general) but this is still only theory and so far remains empirically untested.

What is accent perception?

How listeners subconsciously interpret a speaker's background, personality, and abilities (like intelligence or trustworthiness) based on their accent, often leading to social judgments and categorization that can be positive or negative, influencing social status and even cognitive processes like memory.

It's a complex process where accents act as cues, revealing geographical origin, social class, and ethnicity, and these perceptions are shaped by societal biases and media.

Accent - variations of the same language.

Manner of pronunciation particular to a specific nation or location (or individual).

Some research in phonetics and linguistics but hardly any research in sociology or psychology.

Neuroscientifically we know very little about how accents are processed.

What are the temporal voice areas?

Specific regions in the superior temporal sulcus and gyrus (STS/STG) of the brain that show a stronger response to human voices and vocal sounds compared to other environmental noises, playing a crucial role in voice perception, recognition, and processing vocal cues like identity, emotion, and gender, with distinct subregions involved in different aspects of voice analysis, particularly in the right hemisphere.

Bilateral but often larger on the right

Along the upper banks of the superior temporal gyri (i.e. just above the ears).

Very robust

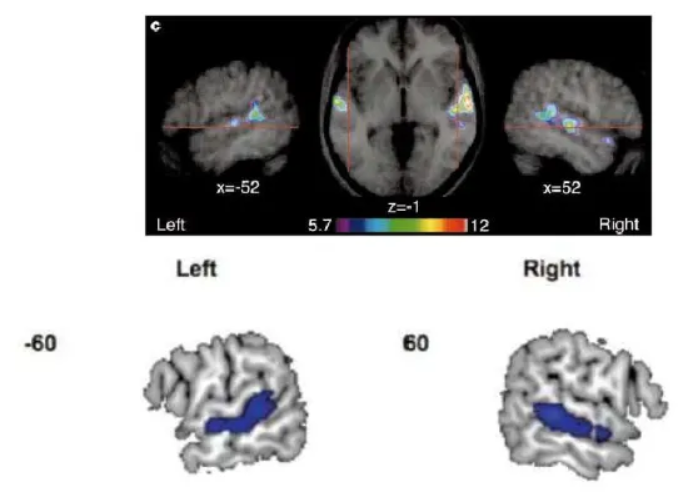

What was the first neuroimaging study on accents?

Published in 2011 (!!) by Adank et al. and replicated this year by the same group.

Interested in neural processing differences of two acoustic variations of Dutch pronounced by same speakers (standard accent and novel, invented accent of Dutch).

Adaptation study – examining an “accent switch”.

The main finding was that the neural bases for processing these two types of distortions dissociated:

Processing speech in background noise resulted in greater activity in the bilateral inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and frontal operculum.

Processing speech in an unfamiliar accent recruited an area in the left superior temporal gyrus/sulcus (STG/STS).

How do voice and accent areas overlap?

Overlap in a network of brain regions, primarily within the superior temporal cortex and the inferior frontal gyrus across both the left and right hemispheres.

Key Overlapping Regions:

Superior Temporal Sulcus/Gyrus (STS/STG): These regions in the temporal lobes are crucial for the initial auditory analysis of sound. They are specialized for processing human voices as a class of auditory objects and are also involved in the early sensory analysis of vocal features that contribute to accent perception.

Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG): This area, which includes Broca's area on the left side, is involved in speech production and motor planning. It is also recruited during the perception of accents, particularly unfamiliar ones, suggesting the brain uses motor regions to help interpret challenging or unfamiliar speech sounds.

Insula and Rolandic Operculum: The left anterior insula and the operculum (the part of the frontal lobe covering the insula) are involved when individuals deliberately change their voice or process variations in speech articulation, which is central to an accent.

Supplementary Motor Area (SMA) and Cerebellum: These areas, part of the brain's speech motor control network, also show overlap. The cerebellum, in particular, is involved in the precise timing and coordination of speech movements (phonation and articulation) that characterize an accent. The SMA is also involved in the initiation and control of speech.

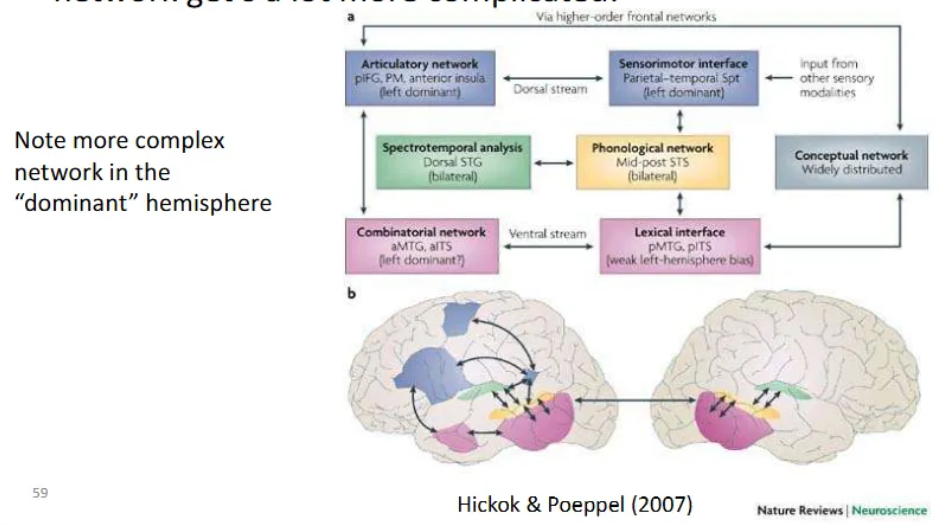

What is Hickok & Poeppel (2007)’s dual-stream model?

A framework for the functional neuroanatomy of speech processing. It proposes that early auditory analysis in the superior temporal gyrus (STG) and superior temporal sulcus (STS) diverges into two distinct processing pathways:

Ventral Stream (The "What" Pathway): Processes speech signals for comprehension. It maps acoustic representations onto conceptual-semantic systems to understand word meanings. This stream is largely bilaterally organized, meaning it utilizes both hemispheres of the brain.

Dorsal Stream (The "How/Where" Pathway): Facilitates auditory-motor integration. it maps acoustic speech signals onto frontal-lobe articulatory networks to support speech production and reproduction (e.g., repeating a word). Unlike the ventral stream, it is strongly left-hemisphere dominant.

Early Stages: Spectrotemporal analysis occurs bilaterally in the dorsal STG, and phonological access/representation occurs in the STS.

Ventral Pathway Structures: Extends from the superior and middle portions of the temporal lobe (Middle Temporal Gyrus/ITS) to distributed conceptual networks.

Dorsal Pathway Structures: Involves the Sylvian parietal-temporal (Spt) junction, which acts as a sensorimotor interface, and projects to the posterior frontal lobe (Inferior Frontal Gyrus/Premotor cortex).

What is foreign accent syndrome?

A small lesion in one of the motor areas is enough to cause a “bizarre” syndrome aka Foreign Accent Syndrome (FAS).

(Stroke-) Patient may “suddenly” speak with a foreign accent often in the absence of any other cognitive or motor abnormalities.

Usually affects dominant hemisphere somewhere along the brain’s cortical-subcortical circuitry.

Lesion can be so small that it goes unnoticed by scans!

It’s extremely rare (~100 documented cases in last century - worldwide).

Lesion can be so tiny that it only affects speech production a tiny bit and sometimes neuroimaging wont even pick it up.

Why are foreign accents found to be “bad” (bias)?

The perception as "bad" in the brain is not due to any inherent flaw in the accent itself, but rather a combination of cognitive processing difficulty (reduced processing fluency) and deeply ingrained social biases and stereotypes.

The primary cognitive factor is the increased mental effort required to understand an unfamiliar speech pattern:

Increased Neural Effort: Listening to an unfamiliar foreign accent makes the listener's brain work harder to map the incoming sounds to known words and meanings. Brain regions associated with auditory processing and speech production show greater activity when processing foreign-accented speech compared to native speech.

Misattribution of Difficulty: The brain generally prefers stimuli that are easy to process (high cognitive fluency). When speech is harder to understand, this difficulty is often unconsciously misattributed to negative qualities of the speaker or the information being conveyed, rather than the accent's unfamiliarity.

Reduced Credibility: Studies show that information presented with a foreign accent is often judged as less truthful or credible than the same information presented in a native accent, simply because it is harder to process.

These cognitive difficulties are amplified by social and cultural factors, which are often unconscious:

In-Group vs. Out-Group Bias: People tend to favor their own social group (in-group) and view others (out-group members, often signaled by a foreign accent) less favorably. This is a learned behavior that starts in infancy.

Stereotype Activation: Accents can trigger stereotypes associated with the speaker's nationality, social class, or education level. For example, a "working-class" accent may be associated with a higher likelihood of committing crimes, while other accents might be seen as less educated.

Learned Associations: These biases are not inherent but are learned through exposure to media and societal attitudes, where foreign-accented individuals may be portrayed negatively or associated with lower social status.

Does this bias apply to accent differences of the same language (e.g. northern vs. southern)?

Generally preference for our own accent over others (e.g. Coupland & Bishop, 2007).

Impacts many situations:

Education: Students remember more info from speakers who speak with the student’s accent.

“Ear-witness” memory.

Personality judgments (e.g. trustworthiness).

What is the halo effect for our own accents?

“It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him.” (Shaw, 1913).

Easy and fast recognition of own accents.

Preference for own accents compared to other English accents.

Positive traits are attributed to own accents

e.g. greater friendliness or credibility

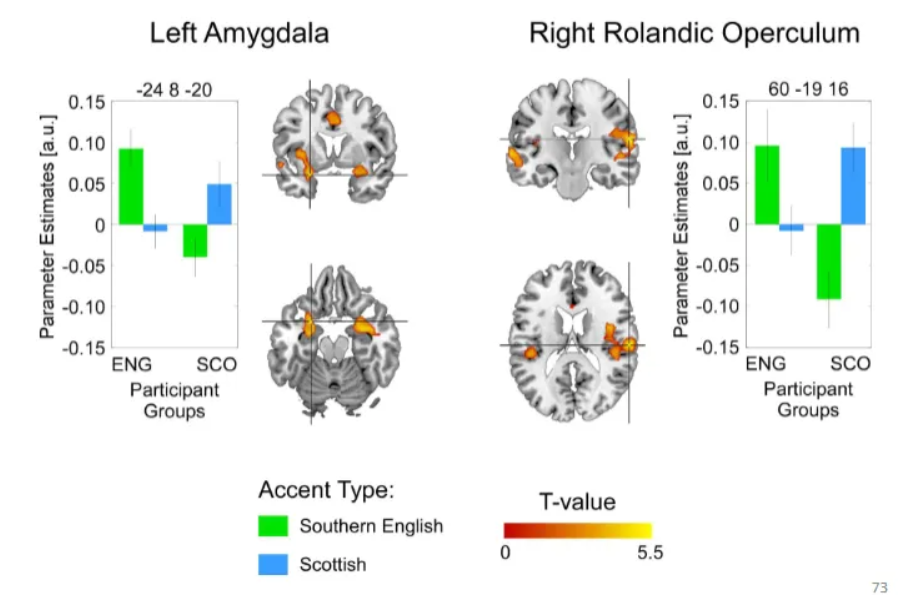

What are the neural mechanisms of the halo effect for our own accent?

Primarily driven by brain regions associated with social relevance detection and emotional processing, rather than basic auditory processing. When hearing an in-group (one's own) accent, individuals show activation in areas that process emotion and social information, suggesting the accent is perceived as more relevant and valuable.

Key brain regions and processes involved include:

Amygdala (bilateral): This region, historically linked to emotion processing, is now understood to be a "relevance detector". Studies show enhanced neural responses (specifically, repetition enhancement) to one's own accent in the amygdala, indicating that in-group accents are processed as more socially or emotionally significant than out-group accents.

Superior Temporal Gyrus/Sulcus (STG/STS) & Middle Temporal Gyrus (MTG): These areas are involved in general auditory processing and voice-sensitive functions. Activity in these regions also increases for in-group accents, suggesting they are sensitive to behaviorally relevant or affectively pleasant voices.

Right Rolandic Operculum and Anterior Cingulum: These regions also exhibit increased activity for in-group accents compared to out-group accents, further supporting an emotional or social-relevance account of the bias.

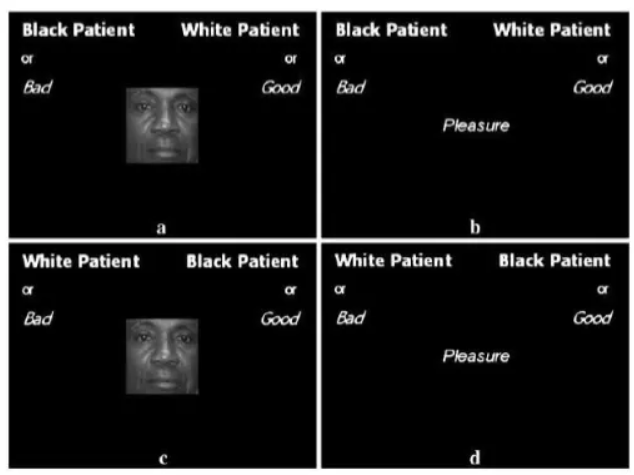

What is the implicit association test for racial bias?

A computer-based psychological tool measuring unconscious biases by assessing how quickly people pair Black or White faces with positive or negative words, revealing automatic associations people might not consciously admit or even know they have.

It works by comparing response times; faster sorting when related concepts (e.g., White faces and good words) share a key indicates a stronger implicit association, suggesting hidden bias, though the test's predictive power for behavior is debated.

Give a summary of accents.

Regional accents as group membership cue

Stronger positive associations with own-accent groups.

Despite “familiarity” with either group

The perception and production of language involves a huge and complex neural network.

Unsurprising that only a small lesion can have an effect – one example leading to a disturbance in production is called “Foreign Accent Syndrome”.

Accents are a part of our identity, they convey where we are from geographically as well as socially.

May be indicator of group membership which we can measure neurally!