ELTAD - (Lightbrown and Spada) - How Languages Are Learned

1/56

Earn XP

Description and Tags

ELTAD reading list

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

57 Terms

Definition of First Language Acquisition

The process by which infants acquire their native language(s) naturally.

Involves understanding and producing words, sentences, and meaning.

Occurs without formal instruction, driven by exposure and interaction.

Early Milestones in First Language Acquisition

Birth–12 months: crying, cooing, babbling; recognise caregiver’s voice; first words.

Around 2 years: 50+ words, two‑word combinations (“Mommy juice”), telegraphic speech.

Development linked to cognitive growth and social interaction.

Stages of Negation in First Language Acquisition

Stage 1: “No” at the start (“No cookie”).

Stage 2: Negative before verb (“Daddy no comb hair”).

Stage 3: More complex forms (“I can’t do it”).

Stage 4: Correct auxiliary + negation (“She doesn’t want it”).

Stages of Question Formation in First Language Acquisition

Stage 1: Single words or short phrases with rising intonation (“Cookie?”).

Stage 2: “Wh‑” words as chunks (“Whassat?”), then “Where/Who.”

Later: “Why,” “How,” “When” as grammar develops.

The Behaviourist Perspective on First Language Acquisition

Language learned through imitation, practice, reinforcement.

Errors seen as bad habits to be avoided.

Criticised for not explaining novel utterances children produce.

The Innatist Perspective on First Language Acquisition

Humans are biologically programmed for language (Chomsky’s LAD).

Universal Grammar underlies all languages.

Input triggers innate mechanisms to develop grammar.

The Interactionist Perspective on First Language Acquisition

Language develops through social interaction and cognitive development.

Caregiver speech (simplified, repetitive) supports learning.

Emphasises negotiation of meaning and shared attention.

Role of Caregiver Input in First Language Acquisition

Child‑directed speech: slower, higher pitch, exaggerated intonation.

Provides clear models and feedback.

Encourages turn‑taking and interaction.

Definition of Second Language Learning

The process of learning a language after the first language (L1) is already acquired.

Can occur in naturalistic settings (immersion) or formal classroom contexts.

Involves both similarities to and differences from first language acquisition.

Learner Characteristics in Second Language Learning

Older learners have greater cognitive maturity and metalinguistic awareness.

Younger learners may achieve more native‑like pronunciation.

Motivation, aptitude, and prior language knowledge influence outcomes.

Learning Conditions in Second Language Learning

Naturalistic settings: rich, varied input; more opportunities for interaction.

Classroom settings: structured input, explicit instruction, limited exposure.

Modified input (teacher talk, foreigner talk) supports comprehension.

Approaches to Studying Learner Language

Contrastive Analysis: predicts errors from L1–L2 differences.

Error Analysis: examines actual learner errors to understand development.

Interlanguage: evolving learner system combining L1, L2, and unique forms.

Developmental Sequences in Second Language Learning

Learners acquire certain grammatical features in predictable orders.

Examples: stages of negation, question formation, possessive determiners.

Similar patterns found across learners regardless of L1.

Influence of First Language Transfer

Positive transfer: L1 structures help L2 learning when similar.

Negative transfer: L1 differences cause errors in L2.

Transfer effects vary by structure, context, and learner awareness.

Other Influences on Second Language Learning

Pragmatic competence: using language appropriately in context.

Phonological development: accent influenced by age and exposure.

Vocabulary growth: depends on input quality, quantity, and strategies.

Teacher Implications from Second Language Learning Research

Expect developmental errors as part of learning.

Provide rich, comprehensible input and opportunities for output.

Balance focus on meaning with attention to form.

Definition of Individual Differences in SLA

Variations among learners that influence second language acquisition (SLA) outcomes.

Include cognitive, affective, and social factors.

No single factor guarantees success; factors interact in complex ways.

Age as an Individual Difference in SLA

Younger learners often achieve more native‑like pronunciation in naturalistic settings.

Older learners may progress faster initially in grammar and vocabulary in classroom contexts.

Critical Period Hypothesis suggests a biological window for optimal language learning.

Motivation in SLA

Integrative motivation: desire to connect with the target language (TL) community.

Instrumental motivation: learning for practical goals (e.g., job, exam).

Motivation can change over time and is influenced by learning context.

Personality in SLA

Traits like extroversion, introversion, risk‑taking, and empathy may affect participation and fluency.

Extroverts may seek more interaction; introverts may excel in accuracy.

Research shows mixed results; personality interacts with other factors.

Learning Styles and Cognitive Styles in SLA

Preferences for processing information: visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, analytic, holistic.

Matching instruction to styles can support engagement, but flexibility is important.

Overemphasis on “style matching” is debated in research.

Language Learning Strategies in SLA

Specific actions learners take to improve language learning (e.g., note‑taking, repetition, inferencing).

Can be cognitive, metacognitive, or socio‑affective.

Strategy training can enhance learner autonomy.

Aptitude in SLA

Inborn ability to learn languages, measured by tests like MLAT.

Components: phonemic coding ability, grammatical sensitivity, memory capacity.

High aptitude can aid learning, but motivation and effort are also crucial.

Other Factors in SLA

Anxiety: can hinder performance if too high, but mild tension may help focus.

Self‑confidence: linked to willingness to communicate.

Attitudes toward TL and culture: influence persistence and success.

Teacher Implications from Individual Differences Research

Recognise and accommodate diverse learner profiles.

Provide varied activities to engage different strengths.

Support motivation, confidence, and strategy use.

Behaviourist Perspective on SLA

Language learning = habit formation through imitation, practice, reinforcement.

Errors seen as bad habits to be avoided.

Linked to Audiolingual Method and Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis.

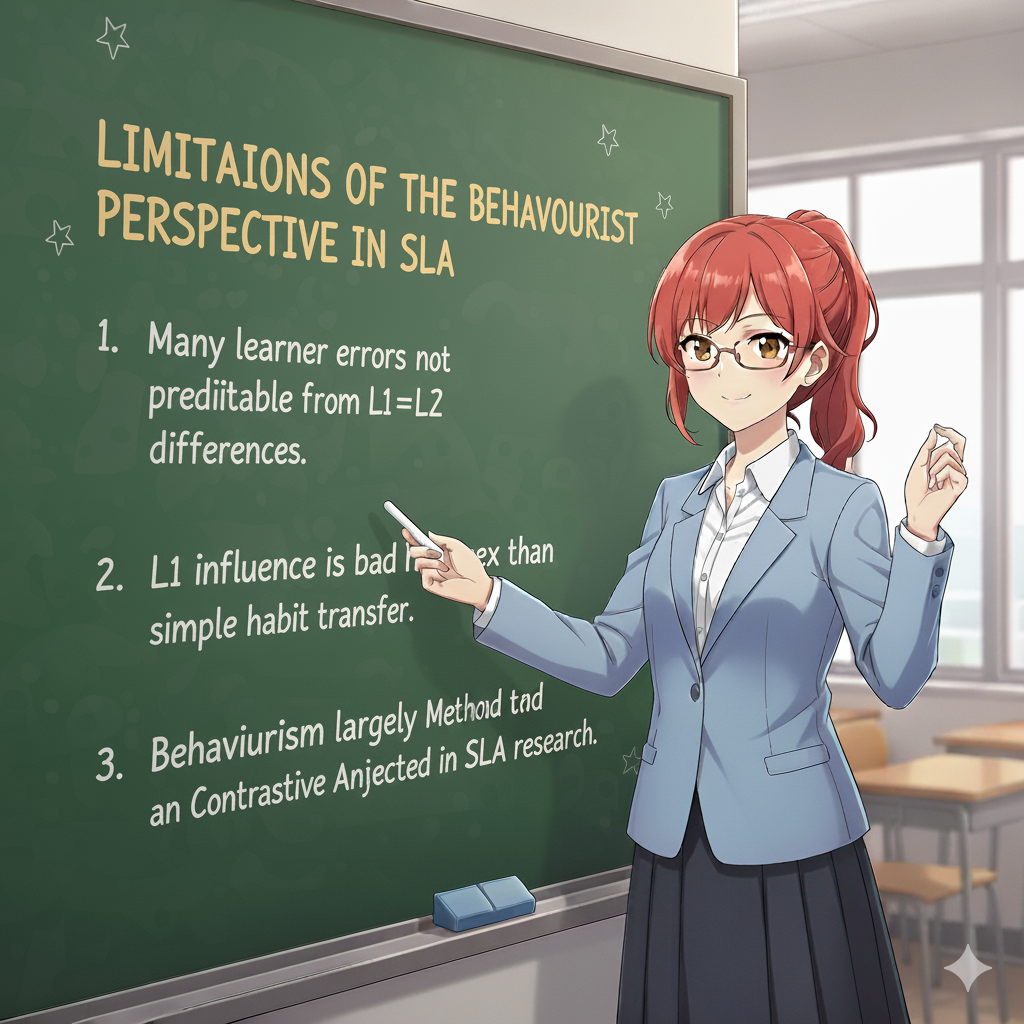

Limitations of the Behaviourist Perspective in SLA

Many learner errors not predictable from L1–L2 differences.

L1 influence is more complex than simple habit transfer.

Behaviourism largely rejected in SLA research.

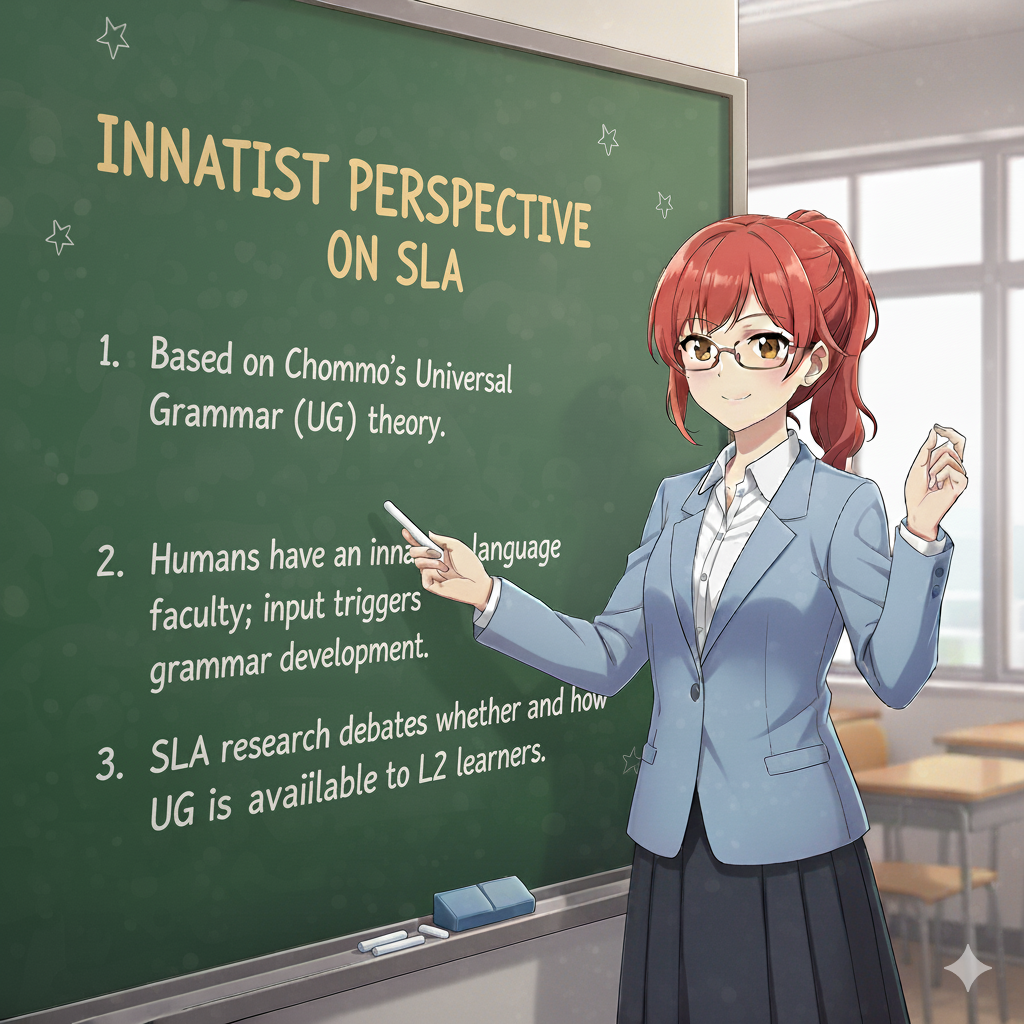

Innatist Perspective on SLA

Based on Chomsky’s Universal Grammar (UG) theory.

Humans have an innate language faculty; input triggers grammar development.

SLA research debates whether and how UG is available to L2 learners.

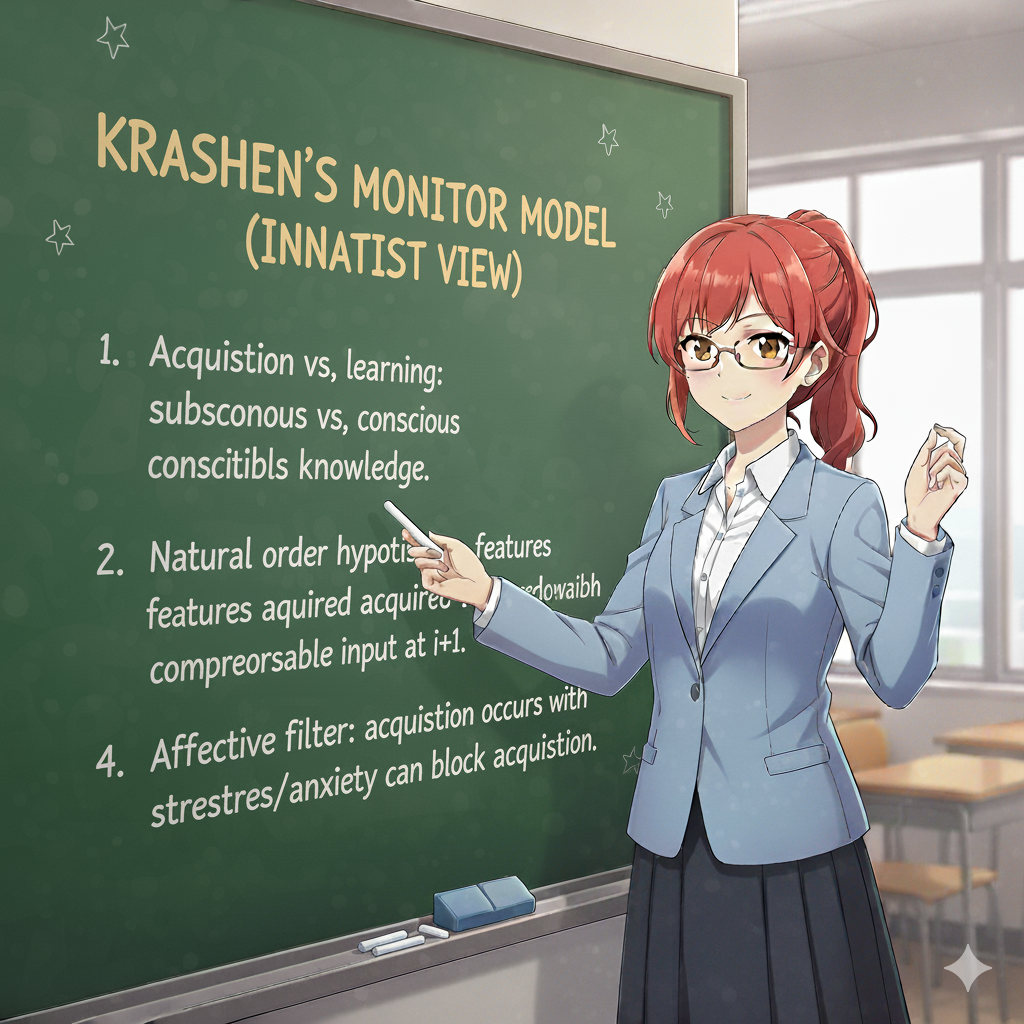

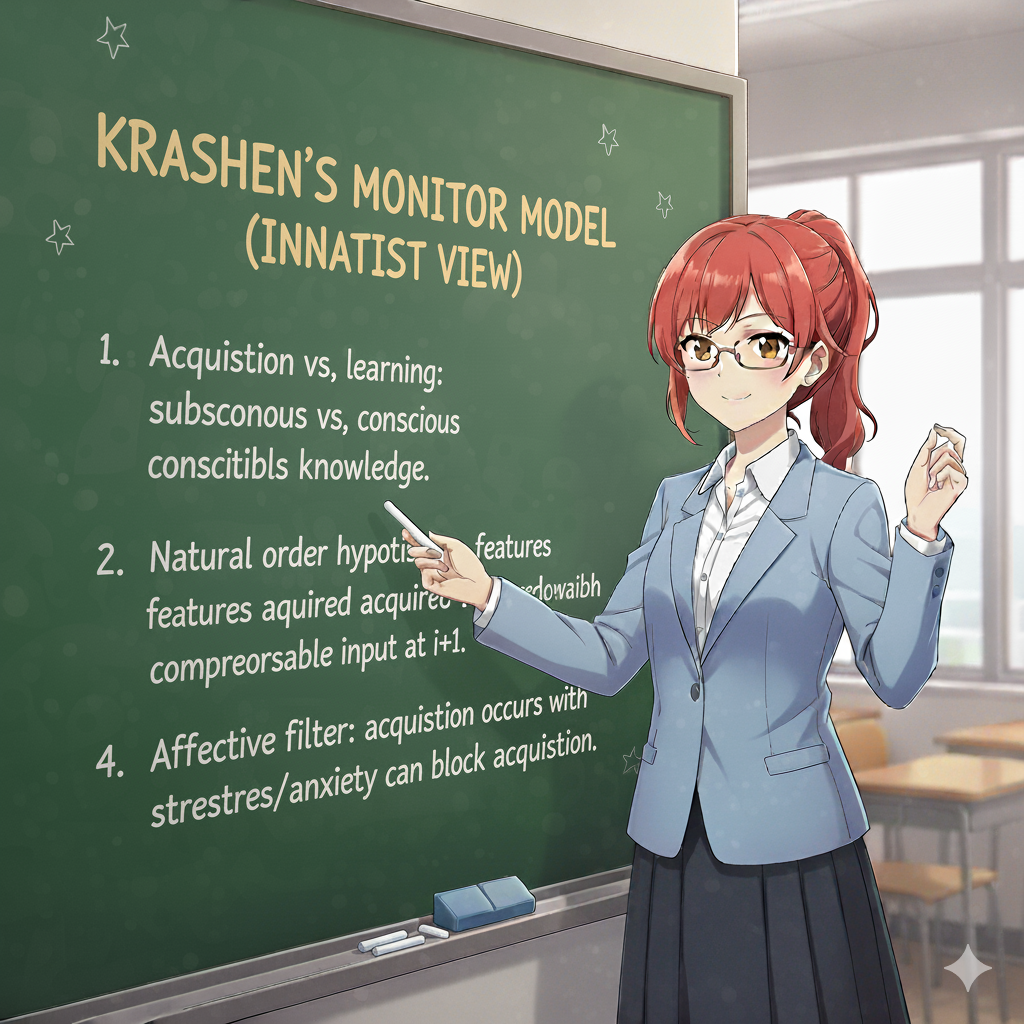

Krashen’s Monitor Model (Innatist View)

Acquisition vs. learning: subconscious vs. conscious knowledge.

Natural order hypothesis: features acquired in predictable sequences.

Input hypothesis: acquisition occurs with comprehensible input at i+1.

Affective filter: stress/anxiety can block acquisition.

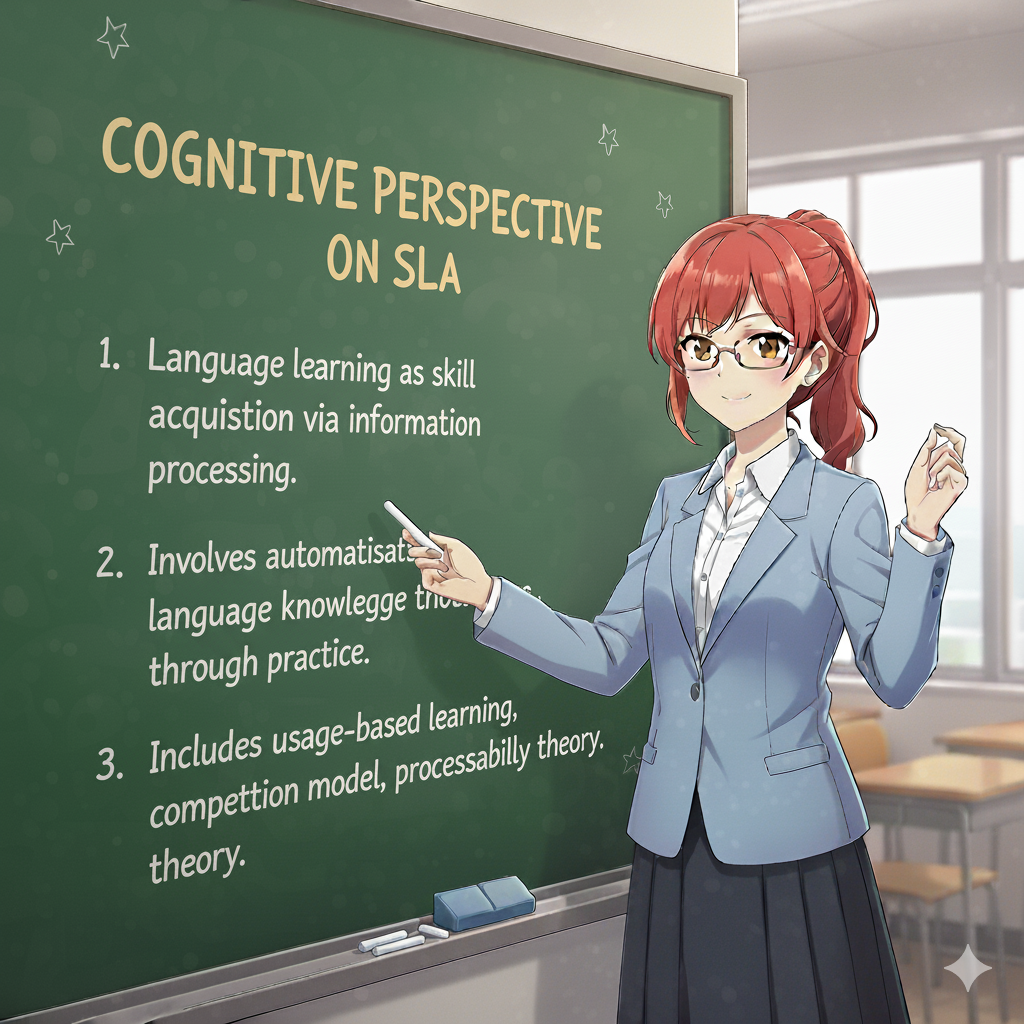

Cognitive Perspective on SLA

Language learning as skill acquisition via information processing.

Involves automatisation of language knowledge through practice.

Includes usage‑based learning, competition model, processability theory.

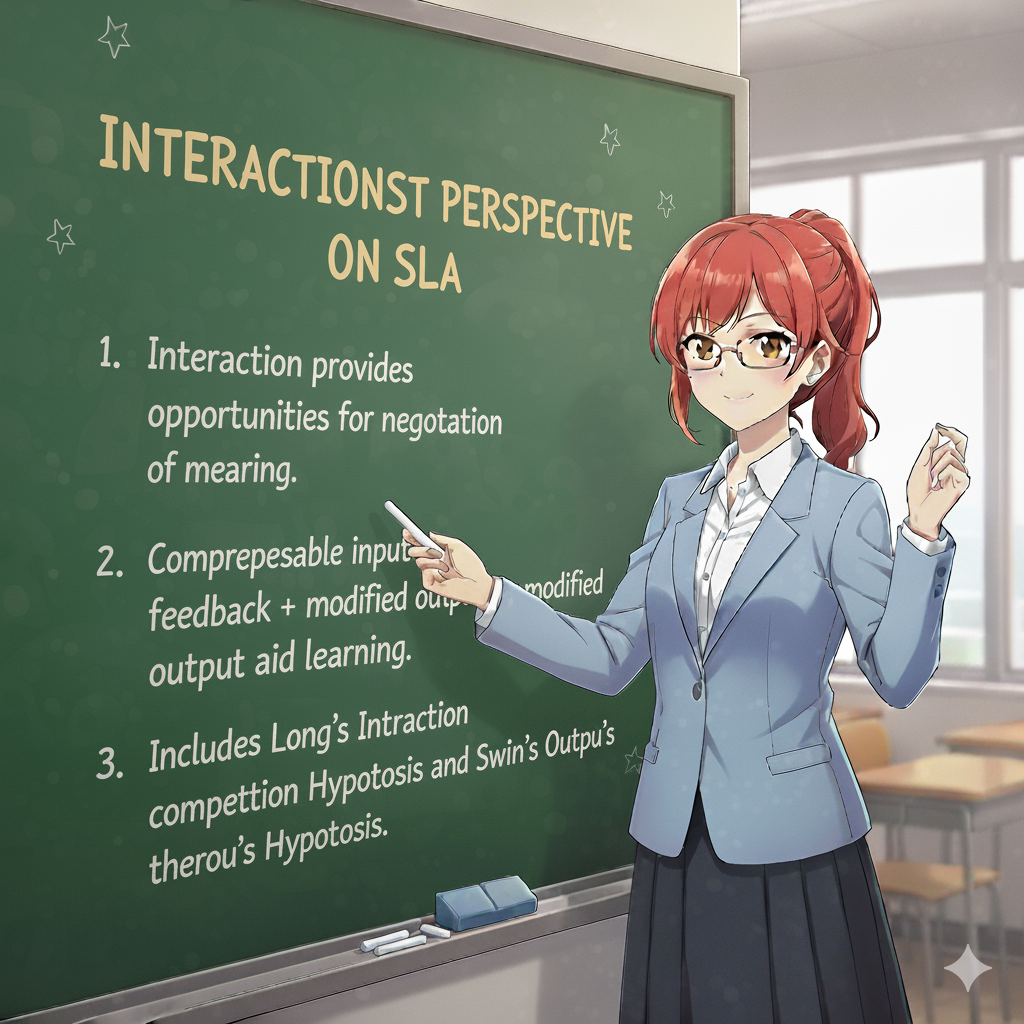

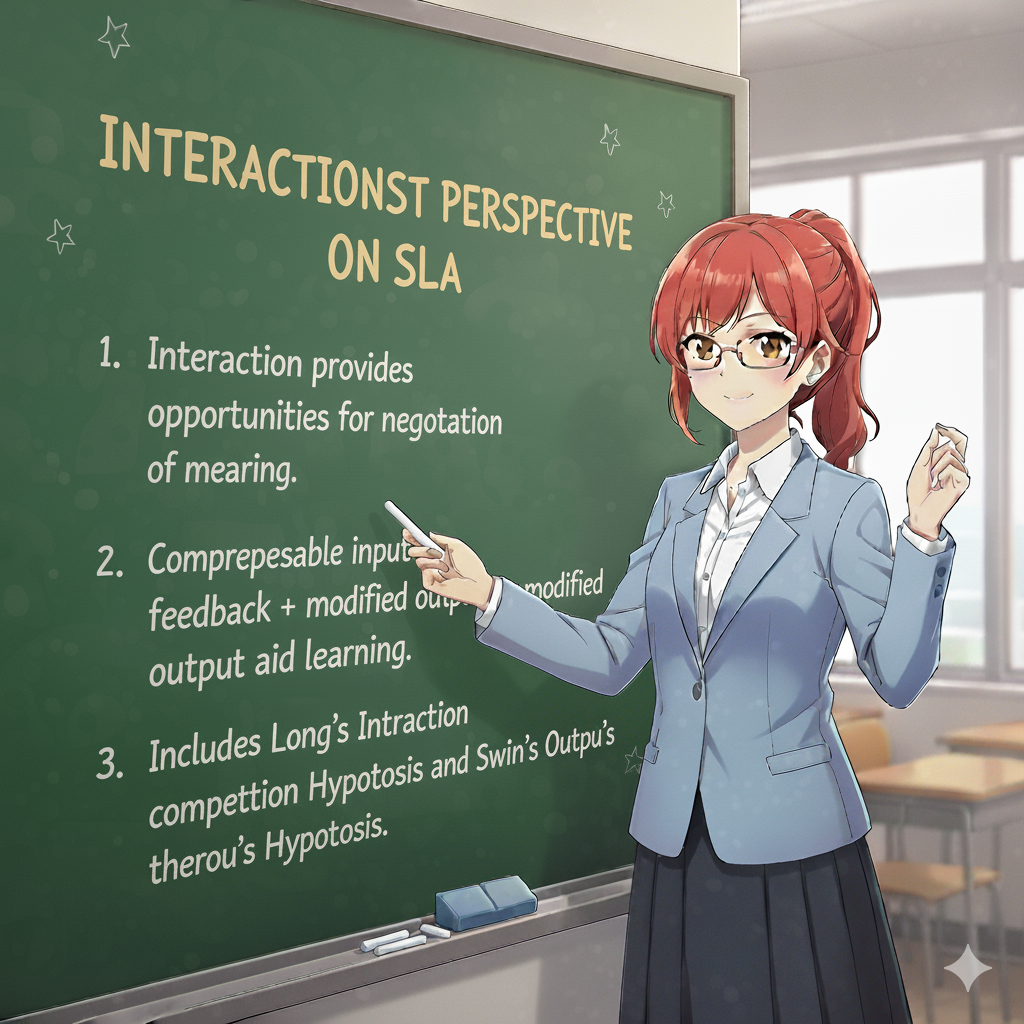

Interactionist Perspective on SLA

Interaction provides opportunities for negotiation of meaning.

Comprehensible input + feedback + modified output aid learning.

Includes Long’s Interaction Hypothesis and Swain’s Output Hypothesis.

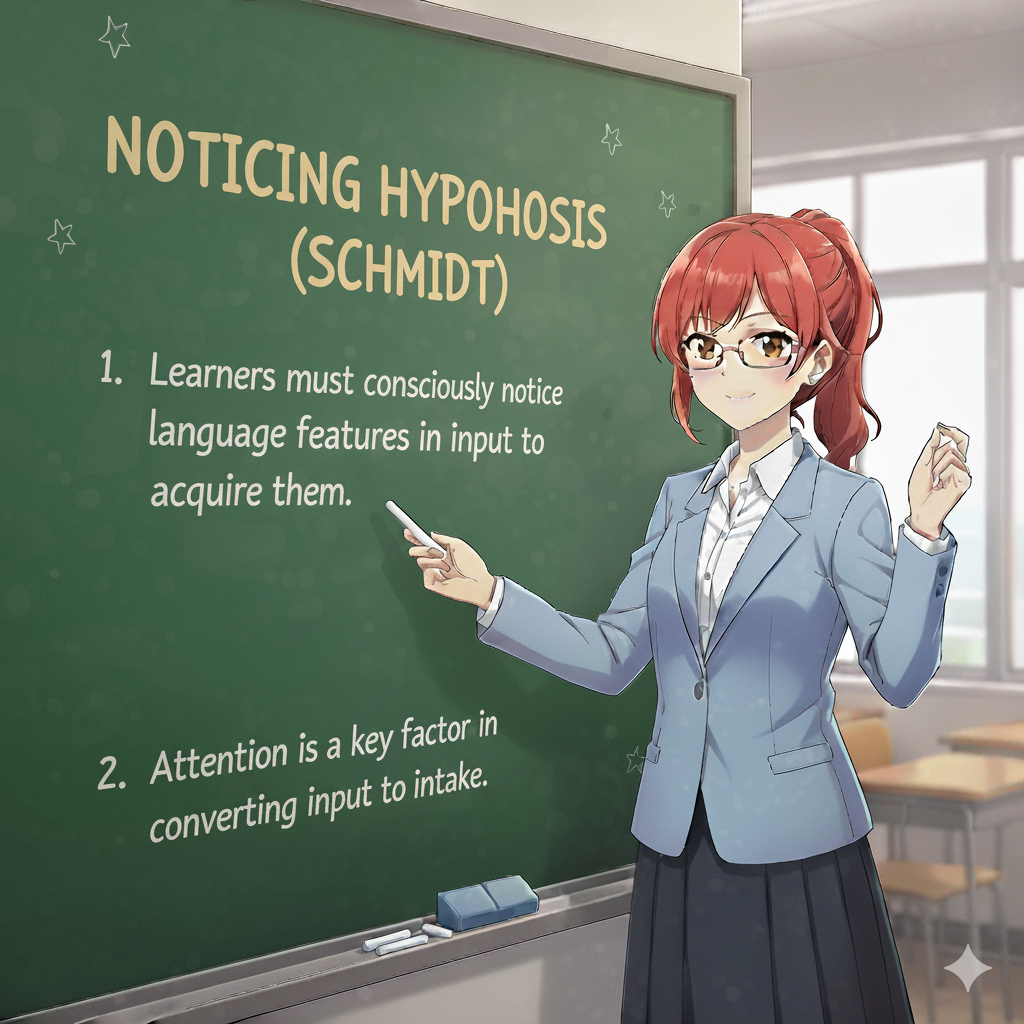

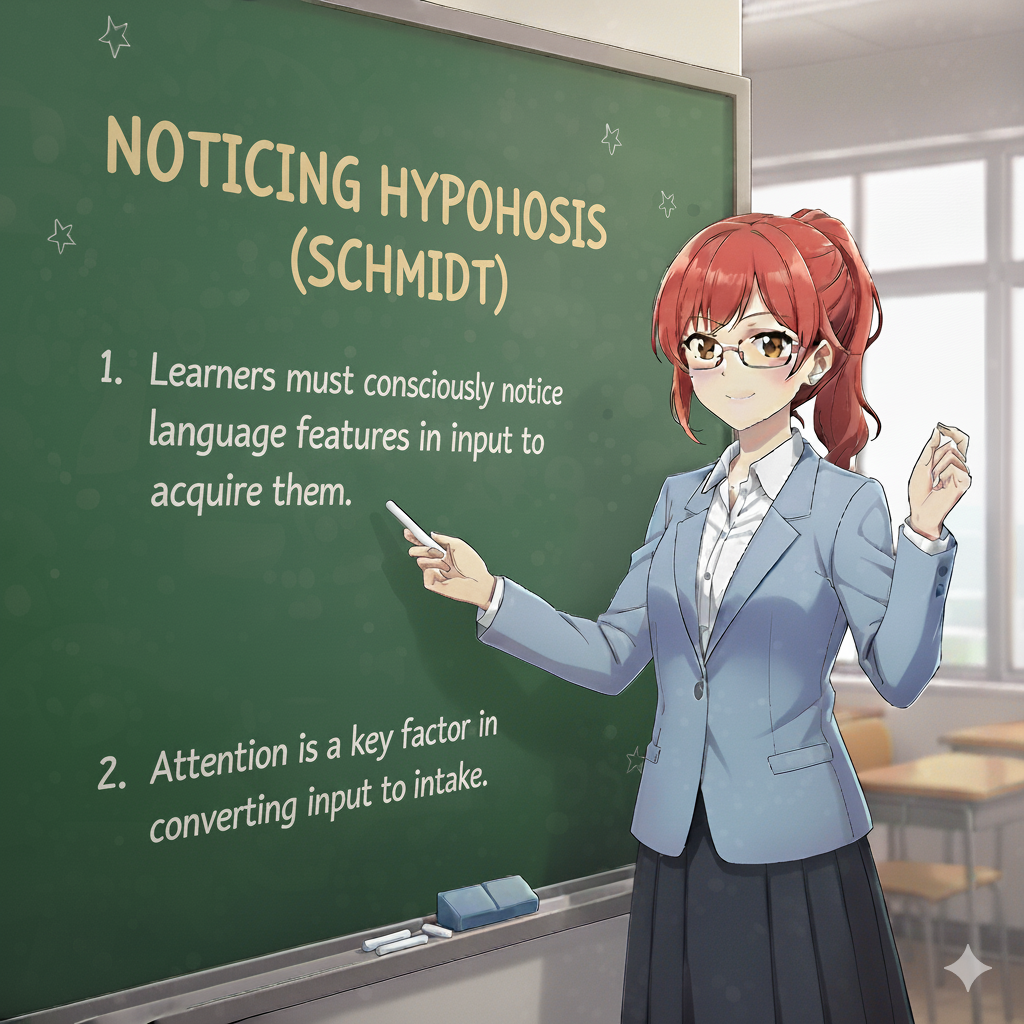

Noticing Hypothesis (Schmidt)

Learners must consciously notice language features in input to acquire them.

Attention is a key factor in converting input to intake.

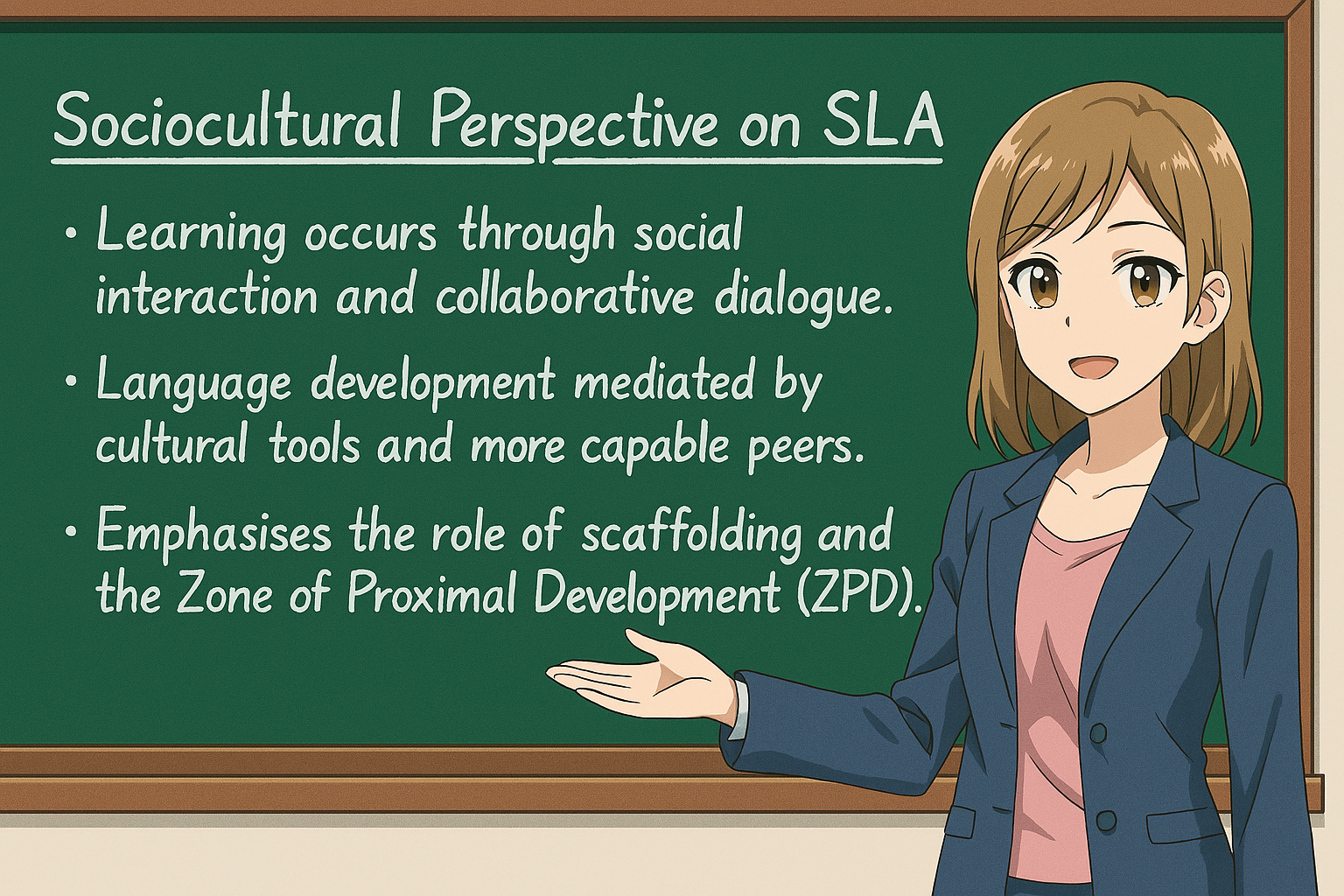

Sociocultural Perspective on SLA

Learning occurs through social interaction and collaborative dialogue.

Language development mediated by cultural tools and more capable peers.

Emphasises the role of scaffolding and the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

Teacher Implications from SLA Theories

Provide rich, comprehensible input and meaningful interaction.

Create low‑anxiety environments to lower affective filter.

Balance focus on meaning with attention to form and feedback.

Definition of Classroom Second Language Learning

SLA that takes place in a structured, instructional setting.

Teacher‑led lessons with planned objectives and materials.

Often limited exposure to the target language (TL) outside class.

Characteristics of Classroom SLA

Input is often simplified, graded, and sequenced.

Opportunities for output may be limited compared to naturalistic settings.

Feedback is more frequent and explicit.

Focus on Form vs. Focus on Forms

Focus on forms: teaching discrete grammar/vocabulary items in isolation.

Focus on form: drawing attention to language features within meaningful communication.

Research supports integrating form into communicative activities.

Corrective Feedback in Classroom SLA

Explicit correction: directly providing the correct form.

Recasts: reformulating learner errors without overt correction.

Elicitation/clarification requests: prompting learner self‑correction.

Interaction in Classroom SLA

Pair/group work increases opportunities for negotiation of meaning.

Teacher‑fronted interaction can limit learner talk time.

Collaborative tasks promote both fluency and accuracy.

Task‑Based and Content‑Based Instruction in Classrooms

Task‑based: learners complete meaningful tasks using TL.

Content‑based: TL used to learn subject matter (e.g., CLIL, immersion).

Both approaches provide rich, contextualised input.

Role of the Teacher in Classroom SLA

Facilitator of interaction and provider of comprehensible input.

Balances communicative practice with attention to form.

Creates a supportive, low‑anxiety environment.

Teacher Implications from Classroom SLA Research

Provide varied interaction patterns (pair, group, whole class).

Use feedback strategically to promote noticing and self‑repair.

Integrate grammar and vocabulary into meaningful communication.

Proposal 1: “Get it Right from the Beginning”

Structure‑based approaches (e.g., Grammar‑Translation, Audiolingual).

Emphasis on accuracy, explicit grammar, and error prevention.

Research: Does not guarantee communicative ability; developmental errors still occur.

Proposal 2: “Just Listen … and Read”

Comprehension‑based instruction (Krashen’s Input Hypothesis).

Learners exposed to rich, comprehensible input via listening/reading.

Research: Sustained input boosts comprehension and vocabulary; best as supplement, not sole method.

Proposal 3: “Let’s Talk”

Interaction‑focused learning; negotiation of meaning central.

Pair/group work, information‑gap tasks, role‑plays.

Research: Interaction promotes fluency and noticing of language forms.

Proposal 4: “Get Two for One”

Content‑Based Instruction (CBI) / CLIL: learn subject matter through TL.

Integrates language and content objectives.

Research: Supports both language growth and subject learning when input is comprehensible.

Proposal 5: “Teach What Is Teachable”

Based on developmental sequences in SLA.

Some structures can only be learned when learner is developmentally ready.

Research: Instruction most effective when timed to readiness.

Proposal 6: “Get it Right in the End”

Focus on form after meaning‑focused communication.

Corrective feedback and form‑focused episodes target persistent errors.

Research: Combining meaning‑focused interaction with timely form‑focus improves accuracy.

Research Approaches in Evaluating Proposals

Quantitative: large‑scale, experimental/descriptive studies to find general patterns.

Qualitative: case studies, ethnographies for in‑depth understanding.

Action research: teacher‑led, classroom‑specific investigations.

Teacher Implications from Chapter 6

No single proposal works best in all contexts.

Effective teaching blends meaning‑focused and form‑focused instruction.

Instruction should be responsive to learner needs, readiness, and context.

Overall Understanding of Language Learning

SLA is influenced by a complex interplay of cognitive, social, and affective factors.

No single theory fully explains all aspects of language learning.

Effective teaching draws on multiple perspectives and research findings.

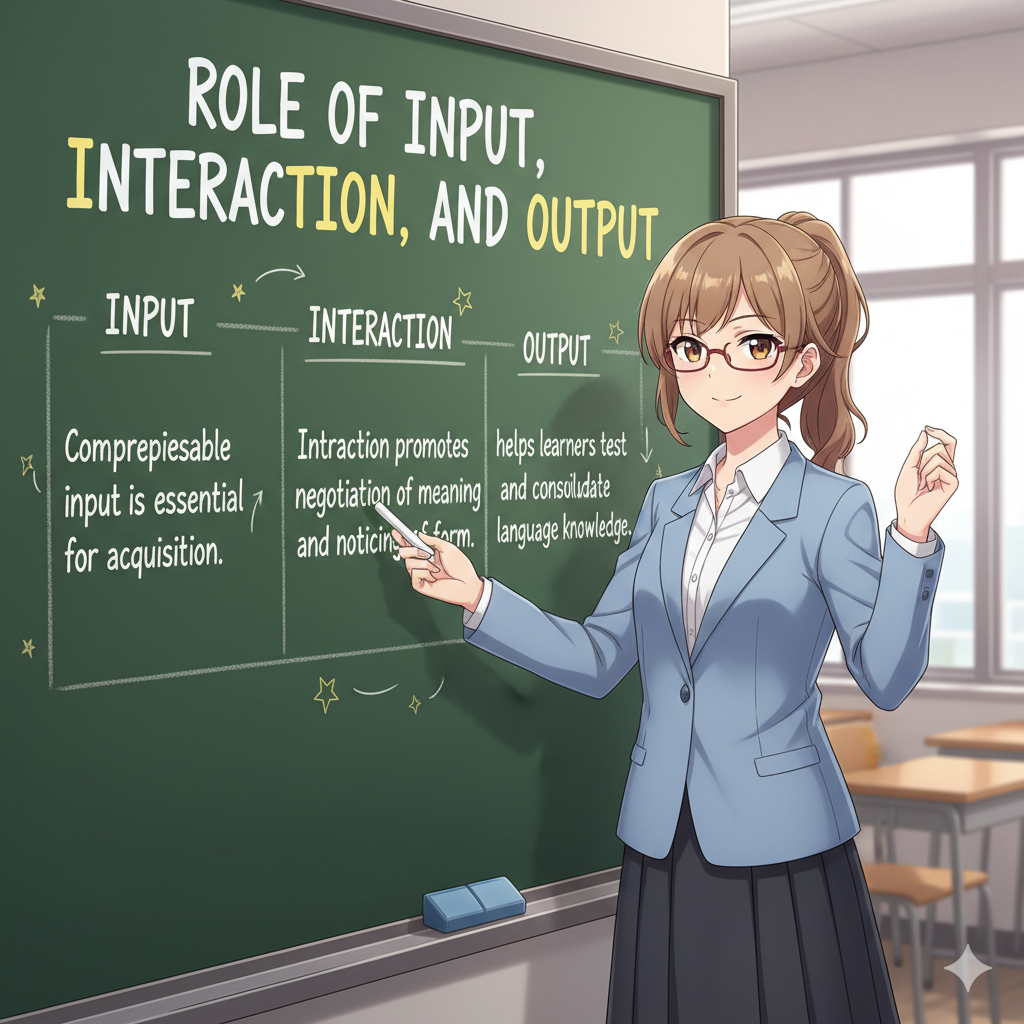

Role of Input, Interaction, and Output

Comprehensible input is essential for acquisition.

Interaction promotes negotiation of meaning and noticing of form.

Output helps learners test hypotheses and consolidate language knowledge.

Importance of Individual Differences

Age, aptitude, motivation, personality, and learning strategies all affect outcomes.

Teachers should accommodate diverse learner profiles.

Learner differences interact with context and instructional approach.

Classroom Instruction Insights

Both meaning‑focused and form‑focused instruction are valuable.

Corrective feedback, when timely and appropriate, supports accuracy.

Task‑based and content‑based approaches provide authentic contexts for learning.

Revisiting Popular Ideas

Purely accuracy‑focused or purely input‑only approaches are insufficient.

Blended approaches that integrate communication and attention to form are most effective.

Instruction should be responsive to learners’ developmental readiness.

Teacher’s Roles in SLA

Create rich, engaging, and supportive learning environments.

Provide varied opportunities for input, interaction, and output.

Encourage learner autonomy and strategy use.

Final Takeaway from the Book

SLA is a dynamic, lifelong process shaped by many factors.

Research offers guidance, but teaching must adapt to specific contexts.

Reflective, informed practice leads to better learning outcomes.