Behavioral Neuroscience Exam 3

1/133

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

134 Terms

Gender

The behaviors and attitudes that a given culture considers to be masculine, feminine, or an alternative

Sex

A trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing organism produces male or female gametes

Gonadal hormones (e.g., testosterone and estradiol)

Mediate early changes in the developing brain to assure that activation of the same circuits by the same hormones in adulthood will produce the appropriate reproductive behaviors

Reproductive behavior

Behaviors for attracting and finding a mate, copulation for exchange of gametes (i.e., sperm, ovum), care and nurturing of offspring on the brain during development

Most of these functions are differentiated in males and females, and due to genetic and hormonal effects on the brain during development

Rehash of sex ed

23 chromosomes pairs in humans; 22 autosomes and 1 sex chromosome – X or Y

a. XY pair = male

b. XX pair = female

Sex hormones are secreted by gonads (testes, ovaries), and they have a steroid structure, hence they are called gonadal steroids or gonadal hormones

Androgens

Gonadal steroids synthesized in testes

Testosterone: An important androgen

Estrogens

Gonadal steroids in females synthesized in ovaries

Estradiol: An important androgen

Sex determination

Process by which the decision is made for a fetus to develop as a male or a female – if the sperm that enters the egg has a Y chromosome, the offspring is male; if an X chromosome, the offspring is female

There is a single gene on the Y chromosome called SRY (sex-determining region of the Y chromosome)

SRY (sex-determining region of the Y)

Directs the formation of testes from the “bipotential” gonad (gonadal precursor to either testes or ovaries), everything else follows from this initial step!

In the absence of SRY (or if there is a loss-of-function mutation in SRY), the default developmental program is toward the female, which means an XY female may occur in rare instances

Sexual differentiation

Process by which individuals develop either male or female bodies and behaviors

After sex determination, hormones secreted by gonads, mainly the testes, direct sexual differentiation (remember if no testes form, then one becomes female)

Embryos have early tissues for both male and female structures

The wolffian and the müllerian ducts connect the indifferent gonads to the body wall

Müllerian ducts

Develop into the female reproductive organs (oviducts, uterus, vagina), most of the wolffian system degenerates

Wolffian ducts

Develop into the male reproductive organs (epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicles), and the müllerian system shrinks

Sexual differentiation of the brain occurs during a sensitive period

Steroids have an organizational effect only when present during a sensitive period in early development

Depending on the species and the behavior, it may be before birth or just afterwards, in the neonatal period

In mammals, puberty can be viewed as a second sensitive period

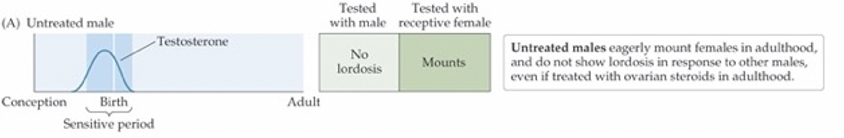

Organizational/activational hypothesis (OAH) — William Young

A framework used to describe the two sensitive periods for gonadal steroid influences in sexual differentiation

“Organizational”

During gestation, the onset of testosterone secretion in males defines the sensitive period for sexual differentiation in the brain – start of masculinization

The end of this first sensitive period is defined as when females are no longer sensitive to the effects of androgens

“Activational”

Later surge of gonadal hormones in puberty and beyond serves to activate the previously organized brain networks

Note that this stage may be constrained by previous events

Rodent sex

In rats, females ovulate, or release eggs, every 4-5 days

The female displays proceptive behaviors, and adopts an arched-based posture called lordosis, allowing the male to mount the female and to engage in intromission (i.e., active process of inserting the penis into the vagina)

The male and female then orchestrate seven to nine intromissions

Only after repeated intromissions will the female’s brain cause release of hormones to support pregnancy

OAH — W.C. Young’s famous experiments in 1950s

One steroid signal—testosterone—masculinizes the body, the brain, and behavior, all during gestation

If androgen isn’t present, the nervous system will organize itself in a feminine fashion

Full masculine behavior requires testosterone during development and adulthood

Sexual dimorphism

Males and females have marked sex differences in appearance (sexual dimorphism also occurs in the brain)

In rats, a subregion in the pre-optic area (POA) of the hypothalamus is larger in many males relative to females

Sexually dimorphic nucleus of the POA (SDN-POA)

Lesions in this area disrupt ovulatory and copulatory behaviors in females and males, respectively

4 key CNS structures altered by organizing effects of gonadal steroids

1. Sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (SDN-POA)

2. Anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the preoptic area (AVPV-POA)

3. Principal nucleus of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis (pBST)

4. Spinal cord, nucleus bulbocavernosus (SNB)

These brain regions are generally larger in the male rather than female brain, and results from hormonal effects on cell death/survival during brain development

Gonadal steroids modulate brain regions not directly involved in reproduction

There are a variety of small but consistent brain differences in males and females

Hippocampus and amygdala show some differences that affect: a) emotionally, b) aspects or learning and memory, c) stress responsiveness, d) affiliative behaviors

Yet these are minor as compared to effects seen in POA and BST regions that drive sex-specific reproductive behaviors

These additional non-reproductive sex differences in brain function are also more subject to modification by experience and environmental factors

Homosexual behavior

The third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH-3), is in the POA

INAH-3 was larger in men than in women, and larger in heterosexual men than in homosexual men

It is not clear if the size difference is a result or a cause of becoming gay

And it is important to highlight that these differences are not thought to be due to any clear organizing effects of androgens during gestation

Homeostasis

Regulation of biological processes that keep certain body variables within a fixed range

Note that this concept is more broadly evident in nervous system than just autonomic

Set point

Refers to a single value that the body works to maintain

E.g., levels of water, oxygen, glucose, sodium chloride, protein, fat and acidity in the body

Negative feedback

Processes that reduce discrepancies from the set point

Food and energy regulation

All the energy we need to move, think, breathe, and maintain body temperature is through breaking of chemical bonds in complex molecules down to smaller ones

33% of energy in food is lost to digestion

55% of energy is consumed by basal metabolism

12% is used for active behavioral processes

Food and energy regulation — steps

First step: Digestive system breaks down food for energy utilization/storage and nutrient absorption

2 pancreatic hormones

a. Insulin: Promotes glucose uptake into cells; promotes conversion of glucose to glycogen – a more storage-friendly carbohydrate — released in anticipation of and after a meal to promote glucose utilization

b. Glucagon: Increases blood levels of glucose; mediates breakdown of glycogen back to glucose

Without insulin, cells in the body (except in the brain, which actively transport glucose across the BBB) are not able to bring glucose into cells

Glycogen is a stored form of glucose (sugar) in your liver and muscles, while insulin is a hormone that tells your cells to use or store this glucose

Diabetes mellitus

Insulin levels remain constantly low, so blood glucose levels stay elevated

a. People eat more than normal, but excrete the glucose unused and lose weight

Type 1: Juveniles onset diabetes; pancreas stops producing insulin

Type 2: Adult onset; associated with obesity; consequence of reduced sensitivity to insulin

Classic lesion studies

Classic lesion studies first implicated the hypothalamus in control of appetite

Bilateral lesions of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) could cause obesity in rats (i.e., hyperphagia)

Bilateral lesions in the lateral hypothalamus (LH) had the opposite effect (i.e., aphagia)

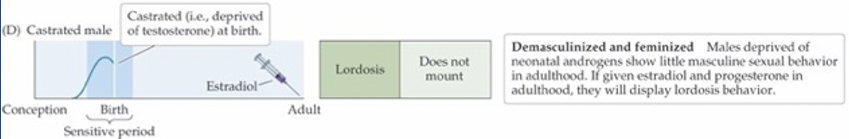

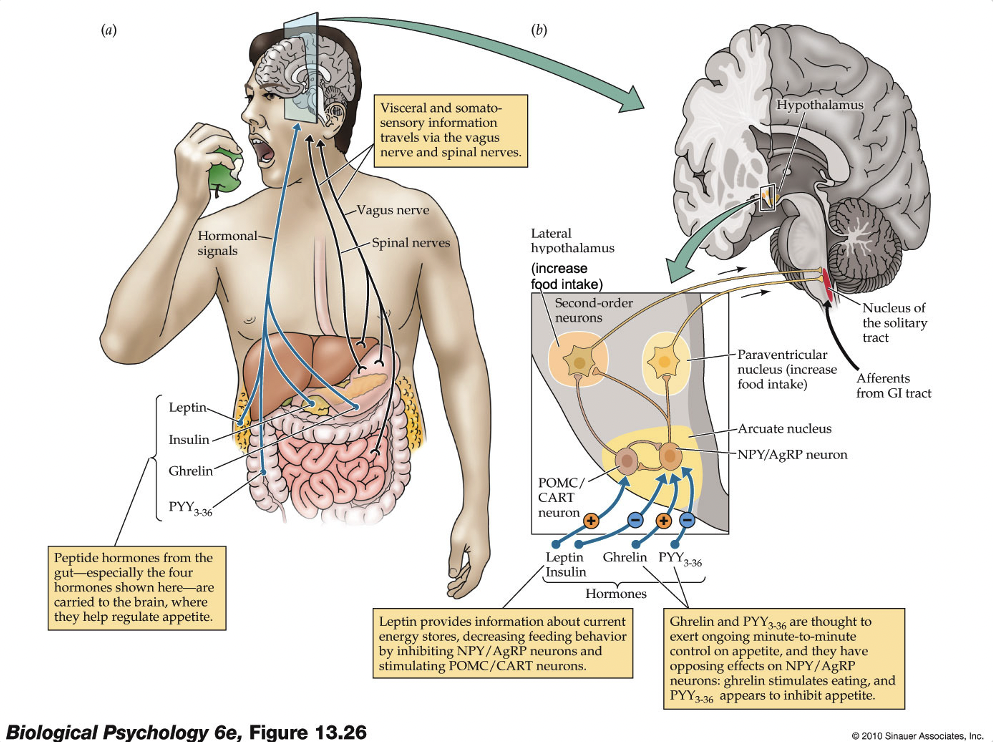

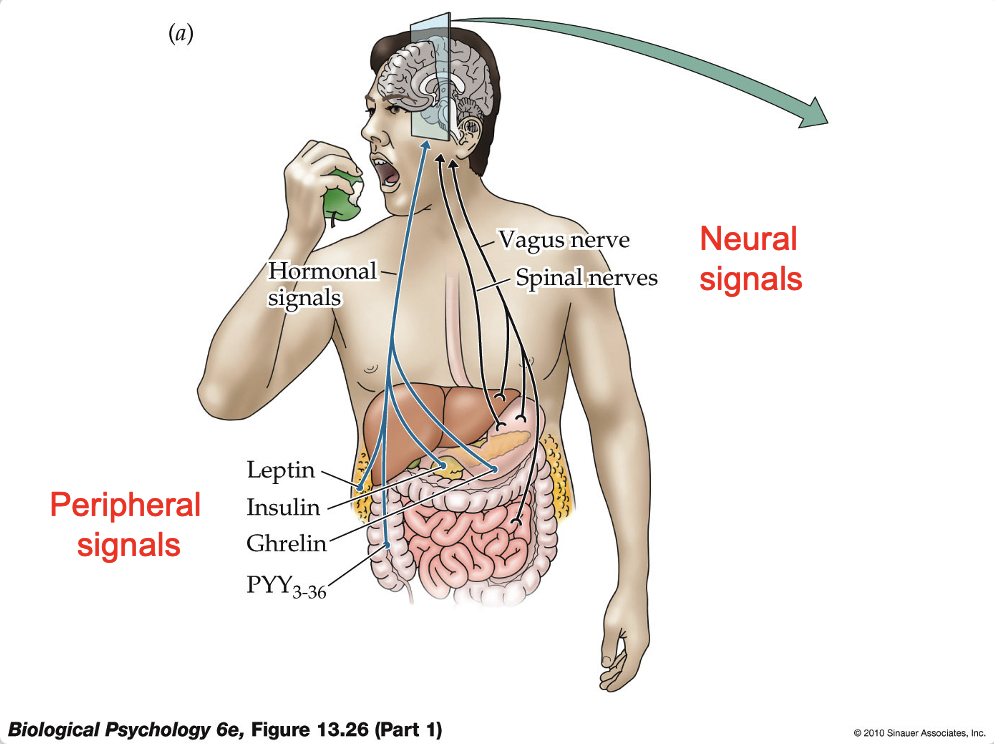

Arcuate nucleus (of the hypothalamus)

Appetite control center that is governed by a variety of circulating hormones in the periphery (e.g., insulin, leptin, ghrelin, cholecystokinin)

Information from all parts of the body regarding hunger impinge onto two kinds of cells in the Arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus

1. Neurons sensitive to hunger signals (i.e., appetite-enhancing) -- NPY/AgRP (neuropeptide Y/Agouti-related protein) neurons

2. Neurons sensitive to satiety signals (i.e., appetite-suppressing) -- POMC/CART (pro-opiomelanocortin/cocaine- and amphetamine-related transcript) neurons

Leptin

Produced by the body’s fat cells when amount of fat stored reaches a certain level – when levels are low it signals to the Arcuate to increase appetite

Leptin was discovered from transgenic mice with defect in gene encoding leptin

Low levels increase hunger, although high levels do not necessarily decrease hunger

Some obese individuals show evidence of reduced leptin sensitivity, and leptin treatment reduces obesity in these folks

Ghrelin

Released into the bloodstream by endocrine cells in the stomach

Circulating levels of ghrelin rise during fasting and immediately drop upon eating

Treating rats/humans with ghrelin produces a rapid increase in appetite

PYY3-36

Released into the bloodstream from the gut

Its effects are opposite of ghrelin: levels are low during fasting, and rise right after eating

PYY3-36 is associated with feelings of satiety – effects of PYY are somewhat like leptin (i.e., satiety-related, hunger inhibiting)

NPY/AgRP neurons

Have appetite stimulating effects

Inhibit POMC/CART cells

Activate paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH)

Activate lateral hypothalamus (LH)

POMC/CART neurons

Have appetite suppressing effects

Inhibit MPY/AgRP neurons

Inhibit LH

Nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS)

Part of a central pathway for feeding behavior

Appetite-stimulating effects of PVH and LH are relayed to, and integrated in, the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS)

NTS receives signals, such as stomach distention, change in glucose levels in the liver, etc., from the periphery via incoming vagus nerve

Cholecystokinin (CCK)

Another peripheral signal that is released by the gut after ingestion of food high in protein or fat

CCK release is associated with feelings of satiety

CCK activates receptors in the vagus nerve, that ascends to the NTS, to signal satiety by inhibiting NPY/AgRP and exciting POMC/CART neurons

(Drugs like Ozempic act on this NTS system)

Biological rhythms

Ultradian rhythms: Frequency > once/day (e.g., rest-activity cycle in humans is 90 min

Infradian rhythms: Frequency < once/day (e.g., menstrual cycle (primates) or estrous cycle (other mammals)

Some animals generate endogenous circannual rhythms, internal mechanisms that operate on an annual or yearly cycle

E.g., bird migratory patterns, animals storing food for the winter, hibernation

Why do we need a circadian rhythm?

The purpose of the circadian rhythm is to keep our internal working in phase with the outside world

Human circadian clock generates a rhythm slightly longer than 24 hours when it has no external cue to set it

**ALL LIFE ON EARTH HAS A BIOLOGICAL MECHANISM FOR TIME KEEPING

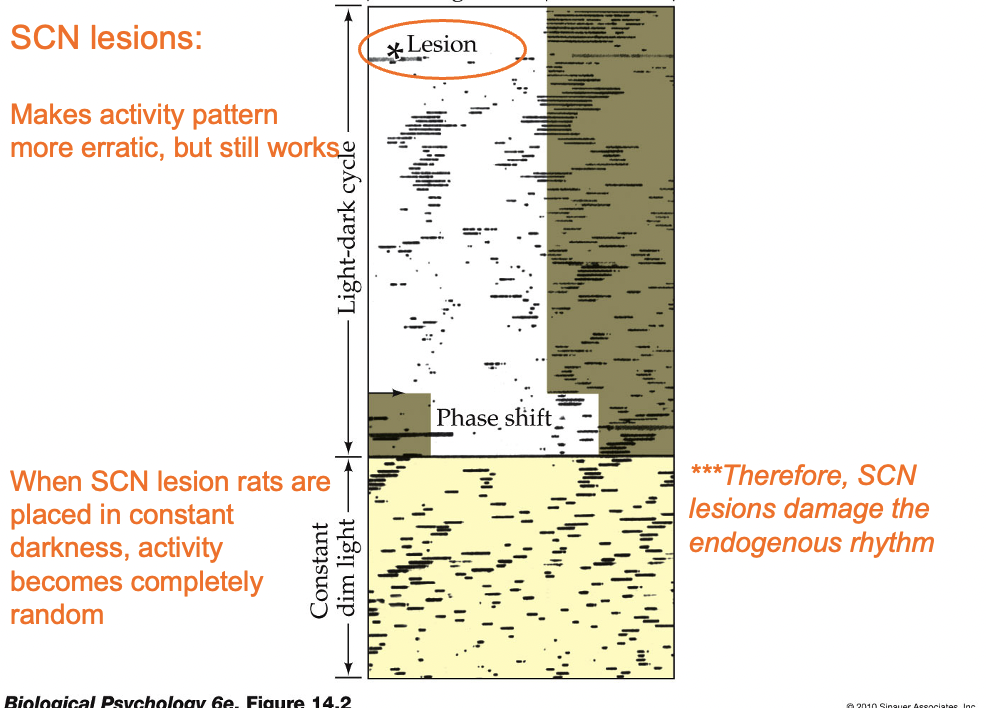

Free-running rhythm

A rhythm that occurs when no stimulus resets it; it is still rhythmic, but not phase-locked with day length

Phase shift

Shift of activity due to a shift in a synchronizing stimulus (e.g., changing time zones during airline travel)

Zeitgeber

Term used to describe any stimulus that entrains the circadian rhythm to the earth’s 24 light/dark cycle, light is the main one

Exercise, noise, meals, and temperature have been speculated to also act as zeitgebers

Suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)

Part of the hypothalamus and the main control center of the circadian rhythm

a. Located dorsal to the optic chiasm

b. Damage to the SCN results in less consistent body rhythms that are no longer synchronized to environmental patterns of light and dark

SCN sends information to hypothalamic nuclei (and indirectly, to the pineal gland) to modulate body temperature and production of hormones

Resetting the SCN

Light resets the SCN via a small branch of the optic nerve known as the retinohypothalamic tract, that travels directly from the retina to the SCN

The retinohypothalamic tract comes from a special population of ganglion cells that have their own photopigment called melanopsin – these cells respond directly to light and do not require any input from rods or cones

How does a cell “know” how to generate such a rhythm?

Early work with drosophila pointed to a gene called per (for “period”)

From there, the mechanisms underlying SCN circadian rhythms in mammals were eventually discovered

Melatonin and pineal gland

The SCN regulates waking and sleeping by controlling activity levels in other areas of the brain

The SCN regulates the pineal gland, an endocrine gland located posterior to the thalamus

The pineal gland secretes melatonin in the evening, which has mild sleep-evoking effects

Jet lag

Refers to the disruption of the circadian rhythms due to crossing time zones – stems from a mismatch of the internal circadian clock and external time

Characterized by sleepiness during the day, sleeplessness at night, and impaired concentration

Traveling west “phase-delays” our circadian rhythm

Traveling east “phase-advances” our circadian rhythms

Electroencephalograph (EEG)

Measures brain activity from noninvasive electrodes placed on the scalp

Allowed researchers to discover that there are various stages of sleep

The general trend of EEG changes from wake to sleep involve a shift from low amplitude, high frequency toward high amplitude, low frequency pattern

Alpha waves

Present when one begins a state of relaxation

Stage 1 sleep

When sleep has just begun – the EEG is dominated by irregular, jagged, low voltage waves, brain activity begins to decline

Stage 2 sleep

Sleep spindles: 12-14 Hz during a burst that lasts at least half a second

K-complex: A sharp high-amplitude negative wave followed by a smaller, slower positive wave

Stage 3 and stage 4

Constitute slow wave sleep (SWS) and are characterized by:

EEG recording of slow, large amplitude delta waves

Slowing of heart rate, breathing rate, and brain activity

Highly synchronized neuronal activity

Rapid eye movement (REM)

Also known as paradoxical sleep

EEG waves are irregular, low-voltage and fast (i.e., like waking)

Postural muscles of the body are more relaxed than other stages

Non-REM sleep (NREM)

Stages other than REM

When one falls asleep, they progress through stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 in sequential order

After about an hour, the person begins to cycle back through the stages from stage 4 to stages 3 and 2 and then REM

The sequence repeats with each cycle lasting approximately 90 minutes

Cerveau isolé (“isolated cerebrum”)

Transection through the mesencephalon; animal shows constant unresponsiveness and signs of continuous SWS

Encéphale isolé ("isolated brain")

Animal with transection at level of medulla; shows normal responsiveness and sleep-wake patterns

Classic studies suggested that SWS is produced by the forebrain (Bremer, 1935)

Bremer interpreted these observations to mean that the cortex must receive sensory afferent information (i.e., via the cranial nerves) for wakefulness

Morruzi and Magoun (1952) later showed that this was wrong, and that an “activating system” in the midbrain actively drives wakefulness

This became known as the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS)

ARAS (ascending reticular activating system)

A collection of anatomical structures with different functions, but there are “wake-maintaining” circuits in this region

We no longer think of the ARAS as driving wakefulness, our modern conceptions is of 4 major systems that interact to mediate states of arousal

Forebrain system

That can display slow wave sleep (SWS) by itself (a la Bremer)

A region called the basal forebrain promotes SWS by releasing GABA into the tuberomammillary nucleus in the hypothalamus. Electrical stimulation of the basal forebrain makes animals sleepy, while lesions of this region induce insomnia. Transections that create an isolated forebrain result in constant SWS.

Stimulation of the preoptic area (POA) produces sleepiness, whereas lesions produce insomnia

Basal forebrain POA neurons become active at onset of sleep and release GABA at a key hypothalamic structure – tuberomammillary nucleus – that is important for increasing arousal

Brainstem system

That activates forebrain into wakefulness (a la Moruzzi and Magoun) — consists of several structures that are AChergic and NEergic

Reticular formation: Collection of cells throughout brain stem; many of which are cholinergic (ACh)

ACh neurons project to variety of structures in brain to promote wakefulness

Locus coeruleus: Major source of NE for entire forebrain; this also has stimulatory effects on alertness

Pontine system

That triggers REM sleep

Small group of cells in pons, just ventral to locus coeruleus, trigger REM sleep

Some cells project to motoneurons in the spinal cord and strongly inhibit them

This system makes muscles flaccid (i.e., not just relaxed) during REM sleep

YET, pontine neurons also project to forebrain and produce widespread activation...hence paradoxical EEG pattern during this stage of sleep

Hypothalamic system

That affects other three brain systems to determine sleep/wake

A region in the hypothalamus, including neurons that use hypocretin as a neurotransmitter, sends axons to the other three sleep centers and seems to coordinate them, enforcing the patterns of sleep.

Loss of hypocretin can lead to disorganized sleep, such as REM-like muscle atonia while still awake (in narcolepsy).

Narcolepsy: Person (or animal) has sudden, intense bouts of sleep during day – sleep lasts 5-30 minutes

Cataplexy: Sudden loss of muscle tone without loss of consciousness (probably due to aberrant activity in pontine/REM system)

In some cases can be caused by strong emotions (positive or negative)

Narcolepsy — orexin/hypocretin

Narcoleptics typically enter REM immediately upon falling asleep rather than SWS at night

Narcoleptic dogs also show immediate entry into REM sleep

In narcoleptic dogs, a mutant gene was isolated by de Lecea and Kilduff encoding for a receptor of hypocretin in 1998; at the same time Yanagisawa’s group discovered the same thing, and called it orexin

Why do we sleep?

Energy conservation

Nice adaptation

Body restoration

Memory consolidation

Energy conservation

Reduced body temperature, slower respiration, slower heart rate > reduced metabolic activity – YET, sleep reduces metabolic rate by only 5-10%

Niche adaptation

Sleep enforces adaptation to a particular ecological niche (e.g., if the animal is better at gathering food during day/night, or may avoid predators day/night, then selective pressure may have favored sleeping in the other part of day)

Body restoration

Sleep helps rebuild/restore body materials and functions

Prolonged deprivation – weakened immune system

Work at night vs. day – increased risk of cancer

Does not refer to simple wear and tear (e.g., exercise does not cause people to sleep longer)

Memory consolidation

Evidence in recent years indicates that sleep promotes memory consolidation

SWS helps in the consolidation of declarative memories (i.e., memory of factual information)

Involvement of REM sleep in consolidation of procedural memories (i.e., skill- or rule-based learning)

Treating sleep disorders

Narcolepsy and cataplexy – different medications can treat this...

Traditionally amphetamines have been used; more recently modafinil (effects of this are not well understood) is used and seems to be very effective

Sleep disorders — very young people

Two common ones in young children; night terrors and sleep enuresis (i.e., bed-wetting)

Both occur during SWS

Can be treated with drugs to decrease stage 3-4 SWS sleep or with an antidiuretic

Somnambulism (sleepwalking): More common among children but can persist into adulthood

Also occurs during SWS; patients are NOT acting out a dream

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

May be due to abnormalities in brainstem circuits that regulate respiration; especially those involving serotonin

Solution? Leave infant sleeping on back, not stomach

REM behavior disorder

Patients appear to be acting out a dream, of somewhat organized-seeming behavior

Begins around age 50 and more common among men

Onset often followed by Parkinsons or dementia

Insomnia

2 categories

1. Sleep-onset insomnia: Often caused by situational factors (shift work, time zone shifts, etc.)

2. Sleep-maintenance insomnia: More due to drugs, psychiatric, neurological problems

Sleep apnea

Respiration becomes unreliable and person may stop breathing for a minute – common cause of insomnia

Sleep apnea may lead to a variety of cardiovascular problems and even neuron death

Continuous positive airwave pressure (CPAP) machine solves sleep apnea

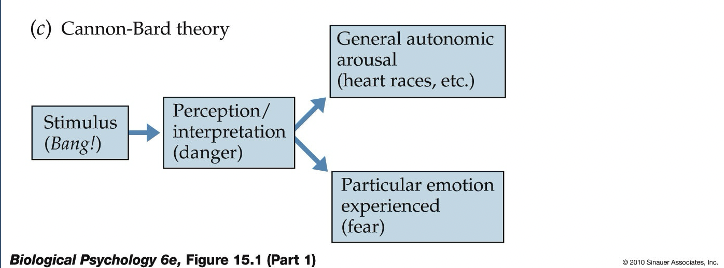

4 dimensions of emotion

1. Physiological: Autonomic, endocrine responses

2. Actions: E.g., laughing; attacking/fleeing in response to threat

3. Motivation: Approach or avoidance behaviors

4. Feelings: Subjective experience

Walter Cannon

First to observe that emotional excitement was associated with the following changes:

a. Increase of adrenaline (epinephrine) in bloodstream

b. Redirection of blood flow from the viscera (internal organs) to skeletal muscles and brain

c. Increased blood pressure and glucose levels

d. Less movement of the muscles in the digestive organs

Cannon coined the term “fight-or-flight" or sympathetic response

Other investigators verified that the posterior hypothalamus played an important role in the expression of emotions

Sham rage

Resulted in a 5-fold increase in blood glucose levels and increased secretions of the adrenal gland (i.e., release of adrenaline)

Cannon showed that stimulation of the diencephalon could produce vocalizations, changes in respiration, circulation, piloerection (hair standing up on back), and coordinated movements in cats

The general idea that emerged from this work is that the diencephalon produces emotional responses but that it is normally inhibited by the cortex

Fear conditioning requires the amygdala

Sensory information related to the threat is then conveyed to the lateral nucleus of the amygdala

Information is processed through the amygdala, and then to the central amygdala for output to structures controlling different aspects of fear responses:

a. Defensive behaviors (periaqueductal gray, PAG; “central gray” on diagram)

b. Autonomic activation (through lat. hyp.)

c. Stress hormone responses (through the anteroventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and paraventricular hypothalamus; avBST and PVH)

Brain system of “approach” behaviors

The common feature to all these manipulation is that the ascending pathway, the medial forebrain bundle, is activated

This pathway contains dopamine neurons, arising from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) that innervate the nucleus accumbens (recall mesolimbic system)

Pleasurable experiences, or emotions pertaining to joy, happiness, all involve activation of the dopamine-nucleus accumbens pathway

VTA-DA neurons

Encode reward prediction error

More recently, evidence suggests that VTA-DA neurons play a role in predicting reward- and aversive-related cues

VTA-DA neurons show reward prediction error – they fire APs more when a reward is larger than expected, and decreased activity when no or less than predicted reward occurs

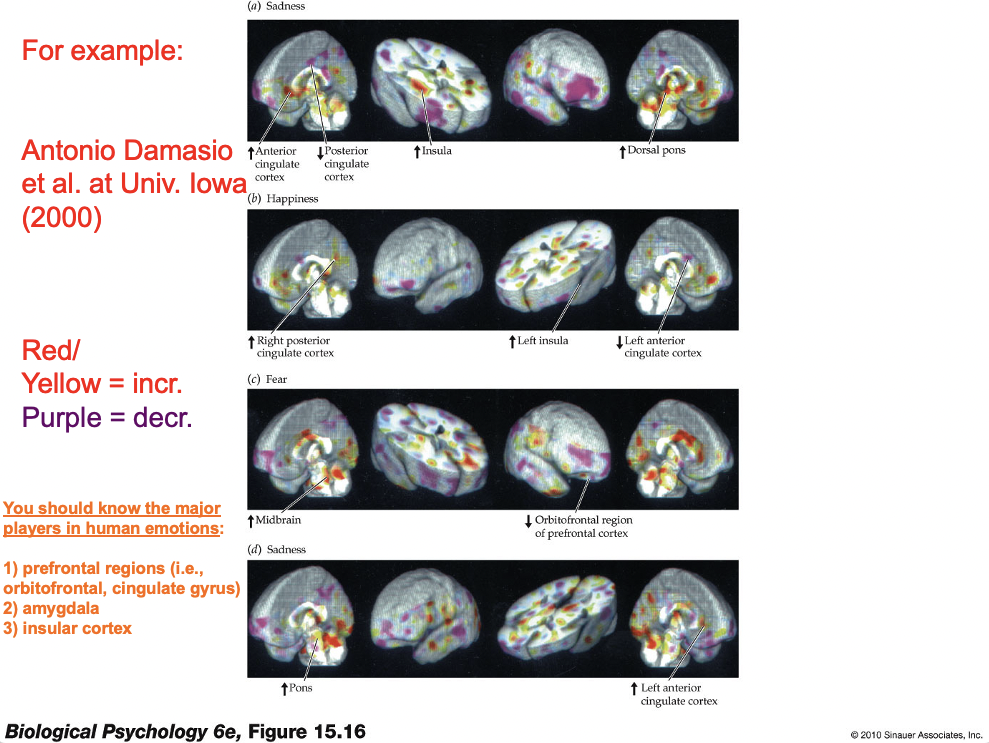

Subjective experiences of emotion

Emotions tend not to be localized in distinct parts of the cortex

A single type of emotion increases activity in various parts of the brain – but not in one single region

Insular cortex

Strongly activated during exposure to stimuli perceived as “disgusting” -- this part of cortex is also responsible for processing taste information (analogous to A1, V1, and S1) so this may tie in to Darwin’s ideas about emotion

Stress

Hans Selye (1907-1982): The first to popularize the use of this term

Selye (1956): Defined stress as “the rate of all wear and tear caused by life”; negative emotions were hypothesized to be one source of “wear and tear”

Selye proposed that the connection between stress and disease is highlighted by the general adaptation syndrome

Selye’s idea of stress

General adaptation syndrome has 3 phases:

1. Alarm reaction: Initial response to stress

2. Adaptation stage: Includes activation of appropriate response systems and re-establishment of homeostatic balance

3. Exhaustion stage: Occurs when stress is prolonged or severe; characterized by increases susceptibility to disease

Two important factors for stress appraisal

1. Predictability: Do you know it is coming

2. Controllability: Can you change the outcome

Both of these can reduce stress

Negative effects of chronic stress

Short Term Adaptation | Long Term Pathology |

Mobilization of energy reserves | Myopathy, fatigue, type 2 diabetes |

Increased cardiovascular output | Hypertension |

Suppression of digestions | Ulcers, irritable bowel disorder |

Suppression of growth | Psychosocial dwarfism |

Suppression of reproduction | Amennorrhea, impotency, loss of libido |

Altered immune function | Immunosuppression, risk of infection |

Heightened awareness, cognition | Synaptic pruning (i.e., cortex, hippocampus) |

ALL ARE MEDIATED BY INCREASED CORTISOL

Psychological dwarfism

Growth failure that results from psychological and social factors is mediated through the CNS and its control over hormone system (Green et al., 1984)

When such children are removed from stressful circumstances, many begin to grow rapidly (asterisks)

Prolonged cortisol secretion from HPA hyperactivity may inhibit growth hormone (GH) release, which is necessary for physical development and growth in children

Effects of early life stress

More recent research showed that these early maternal experiences produce epigenetic changes that mediate alterations in stress reactivity during adulthood

Early life trauma in humans is also associated with a greater risk of major depressive disorder later in life – and is now thought to have an epigenetic basis

Prolonged elevations in CORT in rats cause atrophy in pyramidal neurons and destroy excitatory synapses in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex

Cushings disease

Endocrine syndrome where cortisol levels are chronically elevated; these patients show massive hippocampal shrinkage and cell loss

(Prefrontal cortex has never been examined in Cushings disease patient, but probably this too is affected)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Occurs in some people after certain crises or terrifying experiences

Symptoms: a) frequent distressing recollections, b) nightmares, c) avoidance of reminders of the event, d) exaggerated arousal in response to noises and other stimuli

Stress-related mental illnesses

Main categories: a) major depressive illness, b) reactive depression, c) anxiety disorders, d) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

There is a substantial degree of comorbidity (i.e., overlap) between the occurrence of these disorders

Mental illness — historical origins

1930s: Experiments on frontal lobe lesions performed in chimps inspired Egas Moniz to attempt similar operations in humans

Moniz was intruiged by the calming influence that such lesions were reported to produce

Thus began the era of psychosurgery – the use of surgical manipulation to treat severe mental illness

1970s-present: Occasional examples where surgeries (usually discrete lesions) were performed in attempts to relieve certain mental illnesses; these have had relatively limited value

Although epilepsy is not a mental illness, focal lesions have proven more successful in alleviating frequently occurring seizures

Lobotomy

Frontal lobe lesions

During its heyday, 10-50K patients in US were estimated to have had this surgery

Surgery was supposed to induce relaxation and calm individuals with severe or intractable mental disorders

Side effects were not so good – among many, mood swings, change in personality

Initially, there was much enthusiasm for this procedure, although as side effects became more noteworthy and controlled assessment were made, the procedure was eradicated

Walter Freeman

American psychiatrist that performed and aggressively advocated the prefrontal lobotomy; he probably deserves much of the blame for its overuse

Lobotomies are no longer done, but other lesion-life procedures are still used in rare cases

Characteristics of schizophrenia — positive symptoms

Loose association, tangential thinking

Trouble with making abstractions – no intuition on how to get to the right level of abstraction; usually too concrete in thinking

Delusions – thinking things that can not be true, e.g., as being involved in historical events or interacting with famous people

Paranoia

Structured hallucinations – usually auditory; these have a well-defined structure and content, such as voices

Characteristics of schizophrenia — negative symptoms

Social withdrawal: Abnormal social associations

Absence of affect: Dampened emotionality

Violent tendencies? Not really, but if anything, SZ sometimes involves self-injurious behaviors; upward of half of SZ patient will attempt suicide at some point

Biological/brain differences in SZ — genes

Highly heritable, but hard to link with mechanism – variations genes for MHC, DISC1, and COMT genes have been identified

Biological/brain differences in SZ — brain abnormalities

Live imaging – decreased frontal cortex activity during memory tasks, ventricular enlargement; some postmortem studies show synapse loss in frontal cortex

Biological/brain differences in SZ — developmental

As noted – may aggravate symptoms, but not ultimate cause (e.g., viral infection, poor nutrition of mother during pregnancy, nutritional premature birth, low birth weight, complications during delivery, adolescent marijuana use)