Lecture 4: The Shock of the Old: New Histories of Art in Renaissance Europe

1/8

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

9 Terms

Historical context of the Renaissance (4)

Time period: 14th to 17th Century (1300s-1600s)

Successive popes sought to renew Rome’s status as the centre of papal power after a long period of papal absence in the 14th century (1300s)

During this period, Rome had become largely uninhabited & overgrown

1490s-1500s: popes began to engage in a deliberate programme of renewal

E.g. excavations & construction works for new streets & infrastructure

= rediscovery of many ancient buildings & long-buried statues

Increasing education in classical texts

E.g. Pliny & Cicero

(1) Gave rise to new ways of talking about the arts

(2) Helped canonise key exemplars of ancient art (e.g. the Laocoön, the Apollo Belvedere)

Excitement NOT ONLY about discovering statues, but statues that seemed to match those most praised & recorded by ancients

At the start, there was no adequate lexicon available with which to engage ancient art critically

(Male) beholders gravitated towards words found in their schoolbooks (classical education)

Language of comparison that was favoured by ancient Roman writers

Competition between one art form and another

E.g. Leonardo da Vinci: ‘If the poet claims that he can inflame men to love, the painter has the power to do the same, and indeed more so, for he places before the lover’s eyes the very image of the beloved object’ — The painter can make the beholder feel that there is a real living presence behind/underneath the painting

Competition between one artistic medium and another (the ‘paragone’)

3 models for Art History that arose in the Renaissance

Nature model: The best Art perfects, or even surpasses, Nature

Evolutionary model: Artists should strive to add something new & innovative to the art of their predecessors

Platonic model: Art should capture the perfection of forms & ideas that exist only in the mind, NOT in Nature

Key Renaissance texts that have shaped the way we talk about Art today (3)

Francesco da Holanda’s Da Pintura Antigua (Of Ancient Painting) (1548)

Platonic model

A great work of art should NOT just convey the superficial outer appearance of reality, BUT convey an idea/concept/spiritual insight

Art as transhistorical, existing outside of time & place itself

Artists as visionaries who can make us see beyond mere surface reality, and can instead provide more profound insights into ourselves & others

A great artist ‘[shows] outside with the work of his hand [...] what he can see and sees inside his intellect’

Vasari’s The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550)

Vasari is writing almost 50 years after the discovery of ancient statues in the 1490s-early 1500s

Nature model

Not only offers technical descriptions of how to achieve particular visual effects, BUT adopts a language that evokes poetry

E.g. not just ‘natural’ but ‘gracious’: going beyond nature to find the poetic essence of nature itself, through one’s imagination

E.g. words like ‘grace’, ‘divine’ have spiritual/moral connotations — artists were beginning to be compared to God (the 1st artist)

Evolutionary model

Derived from Aristotle’s scheme for the progress of tragic theatre: developing from simple origins —> increasingly sophisticated

E.g. Preface to the 2nd part: ‘I judge, that is, the peculiar and particular nature of these arts to go on improving little by little from a humble beginning, and finally to arrive at the height of perfection.’

Lodovico Dolce’s Aretin (a Dialogue on Painting) (1557)

Claims to recall what Pietro Aretino had said

A poet & public intellectual

Is cast as one of a pair of interlocutors in a dialogue about art

Nature model

E.g. ‘One’s imitation of Nature should be only partial’ — cites Pliny’s recount of Apelles doing this when painting the Birth of Venus

1 way in which artists can ‘correct the many defects in Nature itself’ is by studying ancient art

‘Antique objects embody complete artistic perfection and may serve as exemplars for the whole beauty’

Evolutionary model

Ancient art NOT just as a perfect exemplar but a challenge to be surpassed

This comparative model was already found in Pliny

E.g. ‘Apelles’s naturalism reaches levels unseen in any earlier artist’

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni (1488), Doemnico Ghirlandaio

Historical context

Tornabuoni was a famous beauty of 15th century Florence

Died in childbirth

Her distraught husband commissioned this painting

Description

Fictive piece of parchment pasted on the right side

A slightly-reworked epigram in Latin

From the 1st century CE Roman poet Martial

‘Art, would that you could represent character and mind! There would be no more beautiful painting on earth.’

Suggests that only poets could represent the inner soul of a person

BUT one could argue that the painting itself serves as a visual rebuke to such claims

Interpretation

Commemorates NOT ONLY her & her outer beauty, but also her inner virtues

Platonic model

Jupiter (early 1540s), reduced-scale version of lost silver Jupiter cast for François I’s palace of Fontainebleau, Benvenuto Cellini

Historical context

Cellini:

A hot-headed Florentine sculptor

Left Florence for Paris, frustrated by a lack of patronage

Felt threatened by the arrival of the bronze casts from Rome

Installation in a special room = intention for the bronze casts to eclipse all other artworks (& artists of the day)

Cellini’s counter-strategy: Jupiter (early 1540s, lost today)

Description

Cast in silver + gilded pedestal

Even more precious than bronze

Lifesize

Gilded pedestal was placed on a wooden plinth, under which there were 4 small balls of hard wood more than half-hidden in their sockets

Allowed the statue to be pushed & turned effortlessly

When King François I arrived at Fontainebleau, Cellini had the sculpture pushed towards him

The King was very impressed

‘Benvenuto Cellini deserves to be made much of, for his performance does not merely rival but surpasses the antique’

Interpretation

Evolutionary model

The Triumphs of Caesar (1484-92), Andrea Mantegna

Historical context

Series of 9 paintings

Reused visuals of ancient Roman fragments & reliefs found in northern Italy

Recombined them in his own imagination to make new & even more perfect examples of the ancient past

Description

Displayed in frieze-like compositional style

Mimics many Roman reliefs

Procession with Julius Caesar in his triumphal chariot

Portrayed in accurate archaeological detail

BUT gives colour to it

Nothing like this would have survived/been described in Roman times

More immersive & lifelike

Interpretation

History, through its representation in the fragmentary remains of antiquity, is turned into something even more perfect

Evolutionary model

E.H. Gombrich, ‘The Renaissance concept of artistic progress and its consequences’

Changing historical contexts (Middle Ages —> Renaissance)

Key texts encouraging a focus on artistic progress (3)

Changing historical contexts

Middle ages: the artist as tradesman; artworks made to order; artistic standards were those of his trade-organisations (e.g. the guild)

The Renaissance:

Art for Art’s sake

The artist’s personal invention > the commission

‘The artist who believes that the arts progress is automatically taken out of the social nexus of buying and selling.’

Leonardo da Vinci: the artist creates NOT to satisfy his customers BUT 'to please the first painters' who are the only ones capable of judging his work

The artist works like a scientist

Displays of virtuosity > adding to the narrative

Artists created works for fellow artists and connoisseurs who can appreciate the ingenuity of the solution put forward

The stronger the admixture of science in art, the more justifiable was the claim to status & progress (liberal arts vs. crafts)

Key texts encouraging a focus on artistic progress

Classical treatises e.g. Pliny: set a precedent for later conceptions of artistic progress

Evolutionary model

Ghiberti’s Commentaries (1447)

Influenced by Pliny

E.g. Pliny’s recounting of Lysippus (ancient Greek sculptor)

Paved the way for a new form of expression by making his figures look taller: heads smaller & bodies slimmer

E.g. Pliny’s recounting of Apelles & Protogenes’ competition to draw a finer line

Ghiberti proposed an emendation

'Speaking as an artist, I consider this a poor test.'

Thought what probably happened was that the two had competed in demonstrating solutions for a difficult problem of perspective

= notion that the artist works like a scientist

Alamanno Rinuccini’s dedicatory epistle (letter) (1473)

Florentine humanist

‘I sometimes like to glory in the fact that I was born in this age, which produced countless numbers of men who so excelled in several arts and pursuits that they may well bear comparison with the ancients.’

Sees ‘canonical’ ancient artists as part of a movement which continues into his own time

Vasari’s Lives (1550)

Idea of Art’s progress through time

Greater skill = better art

Classical antiquity —> gothic disaster —> pinnacle of Michelangelo’s art

E.H. Gombrich, ‘The Renaissance concept of artistic progress and its consequences’

Rebuttals to the focus on artistic progress (2)

Consequences of the focus on artistic progress (2)

Rebuttals to the focus on artistic progress

Alois Riegl: do we have the right to speak of an advance in skill where intention itself is subject to change?

Not all artists through time have aimed for greater skill

The Croceans questioned whether art can be said to have a 'history' at all

Benedetto Croce (1866–1952), an Italian philosopher, historian, and politician

Insisted on the ‘insularity' & uniqueness of each genuine work of art

Individual works of art should NOT be degraded into a mere link in a chain of 'development’

Consequences of the focus on artistic progress

Polarisation

You are either for progress or against it; in contact w/ this main stream of progress or 'out of touch' altogether

Those against it = became provincial, paying for their refusal by being unhitched from the train of progress

Artists are forced to fit into a prescribed means of art-making (have to work towards progress in realistic representation)

The same model can be applied in various contexts

Location might shift from Florence to Rome, from Rome to Paris, from Paris to New York

Areas of interest might change from realism to expression or the articulation of the unconscious

BUT the momentum of progress remains unchanged

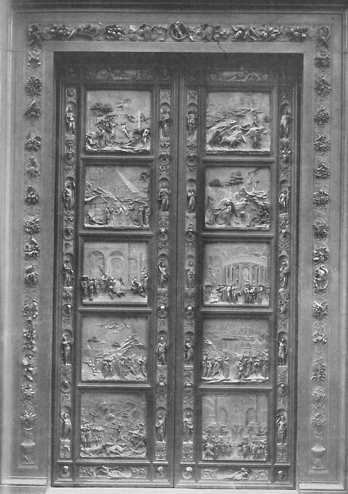

Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Baptistery doors

Ghiberti was commissioned to make 2 different doors @ 2 different times

Door 1 (1403-24)

Saw himself as merely a craftsman who had received an important commission

Originality and progress were NOT values he felt called upon to satisfy

Rather, main aim was to live up to the high standard set by his famous predecessor, Andrea Pisano

Relied on traditional formulas for individual biblical scenes

Stressed his ‘love & diligence’

Door 2 (1425-52)

Ghiberti's contact w/ the new humanist idea of artistic progress

Strived not only to reach the high standard of the past but to make progress, even beyond his own earlier work

Saw himself in the stream of history

Deliberately trying to emulate the role of Lysippus and to change the canon

E.g. strangely elongated human figures

Deliberately re-evoking & reliving the past while striking out towards a new future

NO longer just replicating earlier models

‘It was finished with every skill, harmony and invention at my command’