Chapter 10 - Visual Imagery

1/43

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

44 Terms

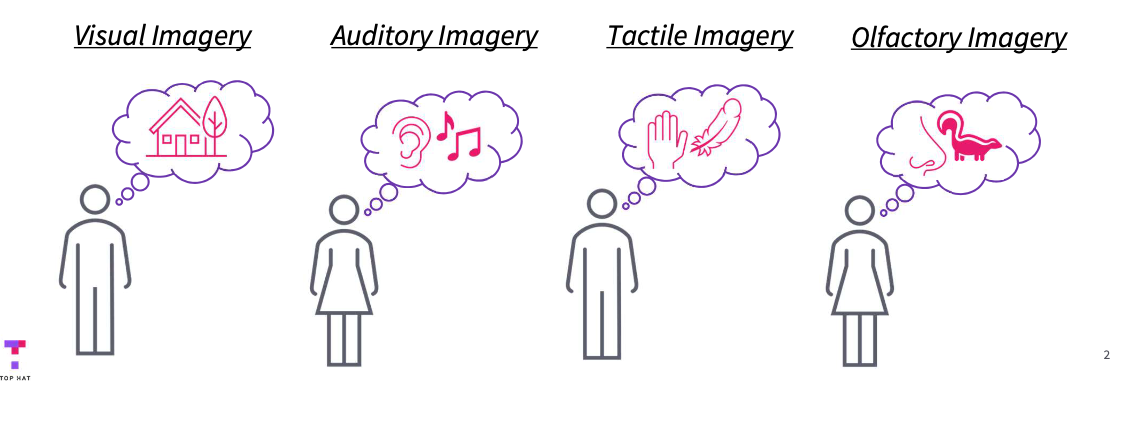

Mental imagery

Our ability to mentally recreate perceptual experience in the absence of a sensory stimulus.”

You can also create mental images of stimuli that you have never experienced.

e.g “‘Imagine a sidewalk covered in chocolate sauce.

Dual-Coding Theory (Paivio, 1971)

Human knowledge is stored in two systems:

• Verbal system: abstract, symbolic, language-based

• Non-verbal system: modality-specific, sensory-motor basedImages function as analog codes, meaning they resemble the things they represent.

Because images preserve perceptual features, they provide a second code that supports memory.

The Imagery Debate Overview

We know that imagery clearly exists and influences cognition (memory, language, decision making).

The debate focuses on how mental images are represented. What format/code does imagery take in our minds?

Kosslyn (1994): Images are depictive—they preserve spatial and perceptual properties.

Pylyshyn (1973): Images are descriptive—symbolic, conceptual codes that do not resemble the real object.

The question: Does the mind store images like pictures, or like statements?

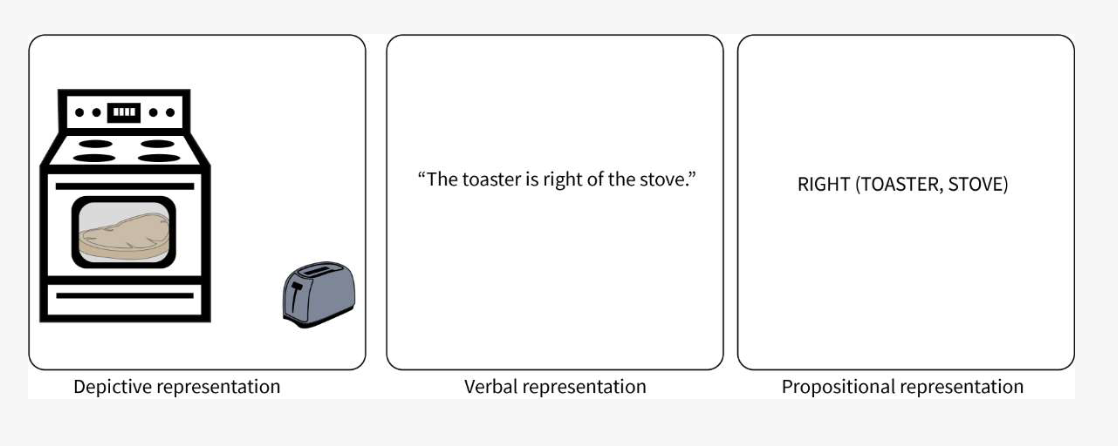

Depictive vs Descriptive Representations (Details)

Depictive representations preserve spatial layout and perceptual information.

Descriptive representations store only conceptual relationships, not perceptual features.

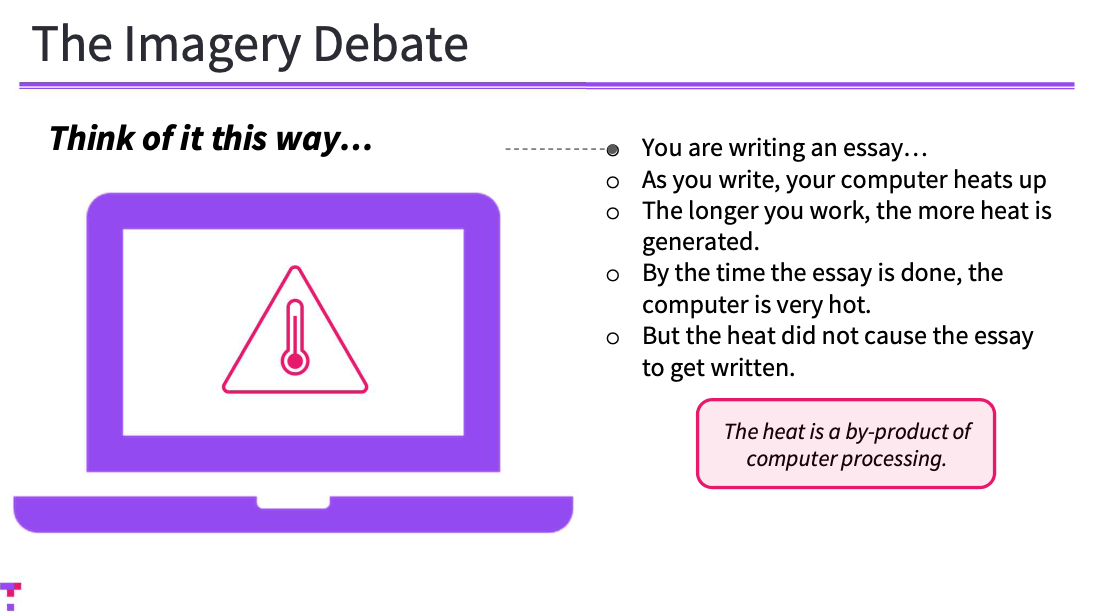

Some argue images are epiphenomena: by-products of deeper cognitive processes, not functional representations.

Propositional Codes (Pylyshyn)

Pylyshyn argued cognitive processing relies on propositions, not pictures.

Propositions are statements that express relationships and can be judged as true or false.

Example: “The lamp is to the left of the books” is a proposition.

According to him, propositional codes are sufficient to explain imagery, so picture-like representations are unnecessary.

Evidence used in the Imagery debate

Researchers have conducted experiments to resolve the imagery debate.

Do people press mental images in the same way they process real stimuli?

If images are depictive (maintain perceptual and spatial characteristics) then people should process images and physical stimuli similarly.

If images are descriptive, then mental processing would depend on the number of propositions instead of perceptual and spatial characteristics of stimuli.

Mental Scanning (Kosslyn, 1973 & 1978)

Asked the question, do mental images keep the same spatial characteristics of physical stimuli?

Kosslyn predicted that if imagery works like a real picture, scanning across a longer mental distance should take longer than a short one.

Participants memorized simple line drawings with clear structure (top/bottom or left/right).

During the task they imagined the picture, focused on one part (for example the roots of a flower), then mentally moved to another part and pressed a button when they “reached” it.

Reaction time increased when the target feature was farther away in the image.

This pattern supports the idea that mental images preserve spatial relationships.

Kosslyn: Addressing alternative explanations

The results could also be explained if participants memorized a list of features instead of a spatial image.

In that case, longer reaction times might reflect searching through a list, not scanning across space.

This alternative supports the descriptive/propositional view of imagery rather than the depictive view.

Mental Scanning Map Study (Kosslyn, 1978)

To respond to the “feature list” criticism, Kosslyn used a map with several landmarks.

Participants memorized the map, then imagined it and mentally traveled from one landmark to another.

Travel time increased as the real distance between landmarks increased.

The number of “features” between landmarks was kept constant, so list-searching could not explain the results.

This provided stronger evidence that mental images preserve spatial distance, supporting depictive imagery.

Mental Rotation (Shepard & Metzler, 1971)

Shepard & Metzler tested whether people mentally rotate images the same way they rotate real objects.

Participants saw two 3-D block shapes and decided whether they were the same shape or different.

When the shapes were the same, one was rotated to different angles before being shown.

Reaction time increased as the rotation angle increased.

This produced a linear relationship: the more rotation needed, the slower the response.

People mentally rotated images at about 60° per second, supporting the idea that imagery uses spatial, depictive processing.

Mental Scaling (Kosslyn, 1975/1978): Size Affects What You “See”

How much detail you can access in a mental image depends on the imagined object’s size.

Example: imagine a cat next to an elephant vs a cat next to a butterfly.

When the cat is imagined beside an elephant (making the cat “small”), participants took longer to answer questions like “Does a cat have claws?”

They needed to mentally zoom in on the smaller image.

This shows mental images behave like real perceptual objects — smaller images contain less accessible detail.

Mental Scaling (continued): Kosslyn 1975, 1978

Participants imagined:

an elephant-sized butterfly,

a butterfly-sized elephant.

When the “target animal” was imagined as smaller, reaction times increased.

This effect depended on the relative size of the objects, not their real size.

Again, this supports depictive imagery because image size affects how quickly features can be accessed.

Imagery & Perception: Interaction (Perky, 1910)

If mental images function like internal pictures, imagery and perception should rely on similar mechanisms.

Perky asked participants to imagine a lemon while a dim, faint image of a lemon was projected on the screen without their awareness.

Participants described their mental images in ways that matched the projected image.

This suggests imagery and perception can interfere with each other because they draw on shared processes.

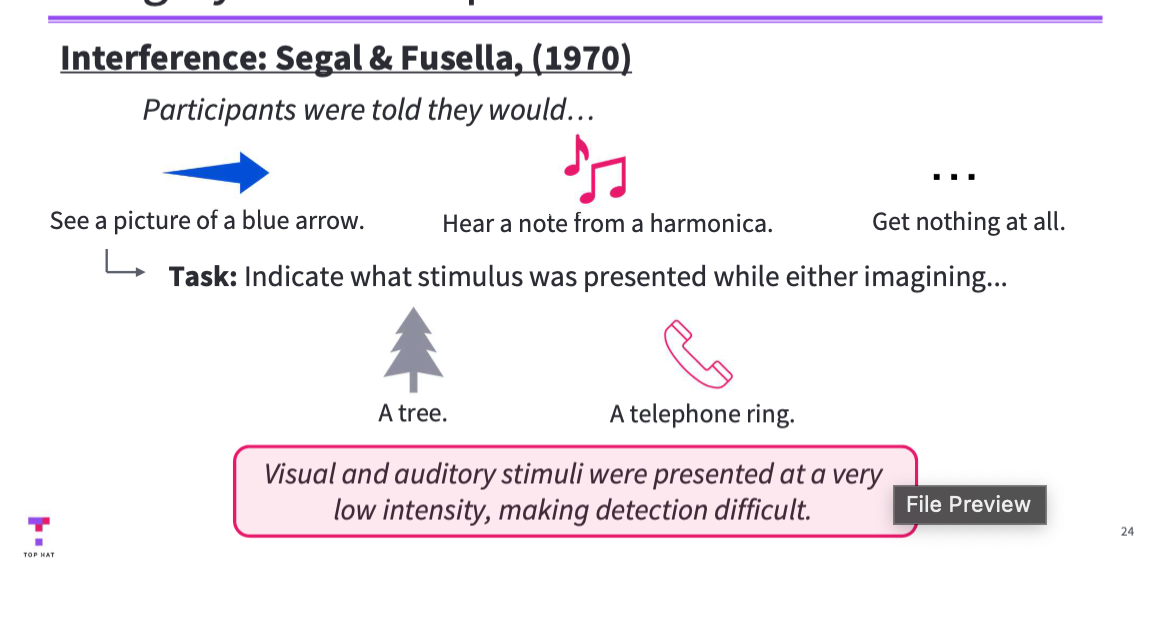

Imagery Interferes With Perception (Segal & Fusella, 1970)

Participants either imagined a visual stimulus (a tree) or an auditory one (a phone ringing).

While imagining, they tried to detect a very faint real visual or auditory signal.

Detection of the visual signal dropped when participants were imagining a visual image.

Detection of the auditory signal dropped when imagining an auditory image.

This selective interference suggests imagery uses the same resources as perception in that modality.

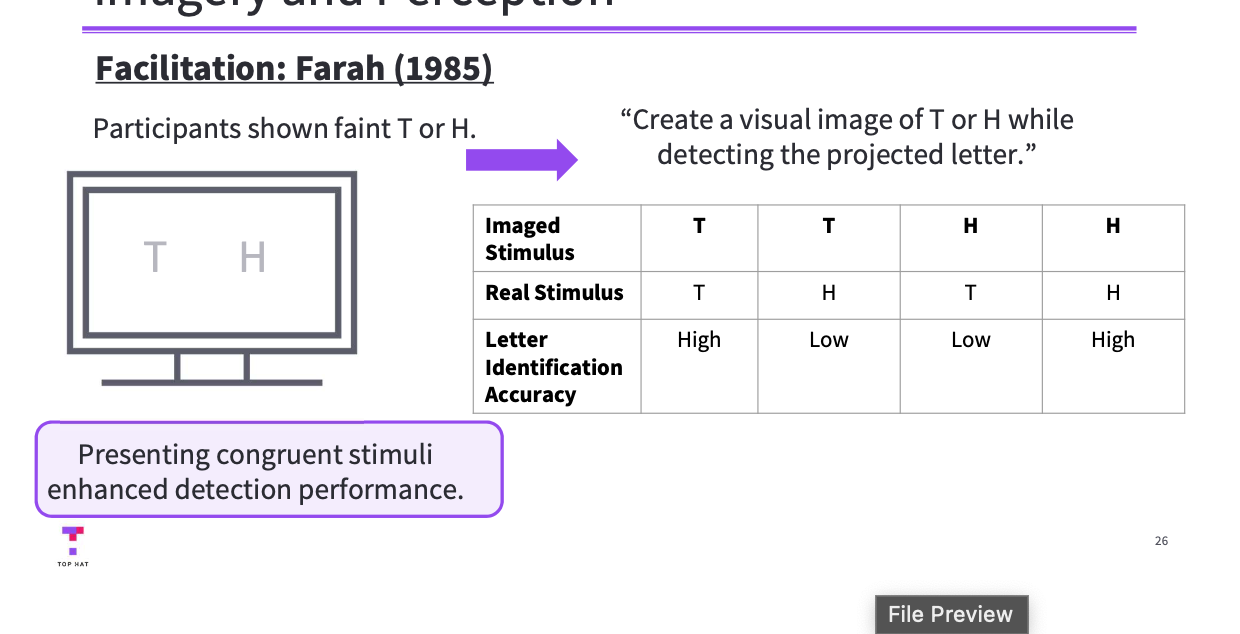

Imagery Facilitates Perception (Farah, 1985)

Imagery and Motion Aftereffects (Winawer et al., 2010)

Normally, staring at motion in one direction causes a motion aftereffect in the opposite direction.

Winawer showed that simply imagining motion for 60 seconds could bias later motion perception.

This demonstrates that imagery can activate motion-sensitive visual areas strongly enough to alter perception, reinforcing overlap between imagery and perceptual neural mechanisms.

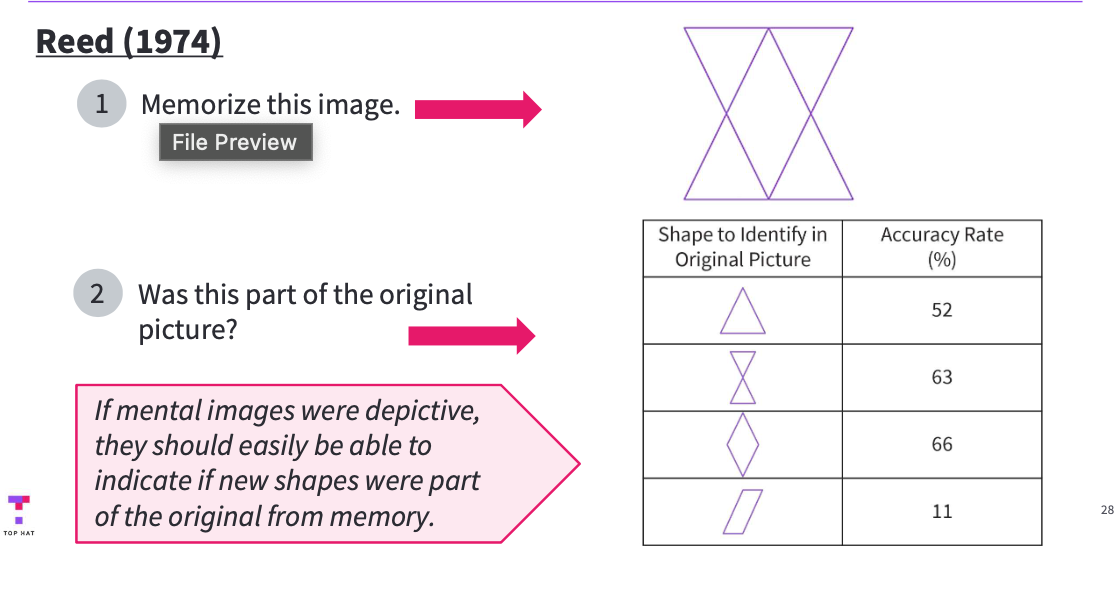

Challenges to Depictive Imagery: Shape Identification (Reed, 1974)

Reed tested whether people can easily extract new shapes from a mental image.

Participants memorized a complex figure, then judged whether new shapes were part of the original picture.

In some cases they were accurate, but in many cases accuracy was low.

Reed argued this is because people were not storing a detailed spatial image.

Instead, they may have stored verbal labels or descriptions of the picture’s components, which do not support detailed shape extraction.

Challenges to Depiction: Demand Characteristics & Expectancy Effects

Research on imagery may be influenced by experimenter expectancy.

Subtle cues from the researcher can unintentionally signal the “expected” pattern of results to participants.

Demand characteristics can also affect performance when participants form an idea of the experiment’s purpose and adjust behavior accordingly.

Pylyshyn argued that some support for depictive imagery may come from these effects rather than from true picture-like mental representations.

arguments against depictive representations continued

Studies show that experimenter expectations can influence participant behavior in imagery experiments (e.g., Intons-Peterson, 1983).

These issues do not invalidate all of Kosslyn’s findings.

Instead, they highlight that both depictive and descriptive theories still have valid arguments.

Advances in neuroscience allow researchers to study imagery using brain activity, which may help clarify how imagery is represented.

Studying Imagery in the Brain: Patients & Neuroimaging

Early imagery research examined patients with localized brain damage to infer which brain areas were involved in imagery.

New imaging techniques (PET, fMRI) allow researchers to directly compare brain activity during imagery and perception in healthy individuals.

These tools help reveal the structure and function of mental imagery processes.

Patient TC: Loss of Perception and Imagery

Patient TC suffered cardiac arrest and had damage in the occipital and temporal lobes, resulting in cortical blindness.

TC was unable to distinguish light from dark, did not blink or move the head in response to moving objects, and had lost conscious vision.

TC also showed a loss of mental imagery ability, unable to describe familiar objects, places, or tasks from memory.

This case suggests that imagery and perception share neural systems, because damage affected both abilities.

Patient PB: Loss of Vision but Preserved Imagery (Zago et al)

Patient PB experienced a stroke that caused occipital lobe damage and cortical blindness, similar to TC.

However, unlike TC, PB could still perform visual imagery tasks.

This shows that imagery and perception can sometimes dissociate, meaning they rely on overlapping but not identical neural systems.

Madame D: Impaired Perception but Preserved Imagery. Bartolomeo et al

Madame D had multiple strokes affecting the area between the occipital and temporal lobes.

She had partial visual ability but suffered color blindness and struggled to recognize faces, objects, or read.

She could copy drawings (basic perception intact) but not identify what she copied.

Despite this, she retained mental imagery and used it to help identify objects at home.

Her case shows imagery can sometimes support perception, and again suggests partial overlap but not full equivalence between the two systems.

Imagery Lost but Perception Intact

Some patients with closed-head injuries lost the ability to form mental images while keeping normal performance on tests of visual perception, memory, and language.

They could not draw animals or objects from memory even though they could see normally.

These cases show the reverse dissociation: perception without imagery.

Taken together, patient studies reveal that imagery and perception rely on related but not identical brain systems.

Neuroimaging Supports Shared Mechanisms (Kosslyn, 1999)

Neuroimaging studies generally show that imagery and perception use overlapping brain systems, though not perfectly identical.

Kosslyn used PET to measure brain activity while people viewed and imagined black-and-white stripes.

Both viewing and imagining the stripes activated primary visual cortex (V1).

Using TMS to disrupt V1 made people less accurate during imagery tasks.

This provides causal evidence that V1 contributes to visual imagery, not just perception.

Specialized Brain Areas Activate in Both Imagery and Perception (O’Craven & Kanwisher, 2000)

Researchers tested whether imagery activates the same specialized regions that perception activates.

When participants viewed or imagined faces, the fusiform face area (FFA) showed higher activity.

When participants viewed or imagined buildings, the parahippocampal place area (PPA) showed higher activity.

Brain activity patterns were strong enough to classify what category a person was imagining.

suggests shared areas of perception and imagery

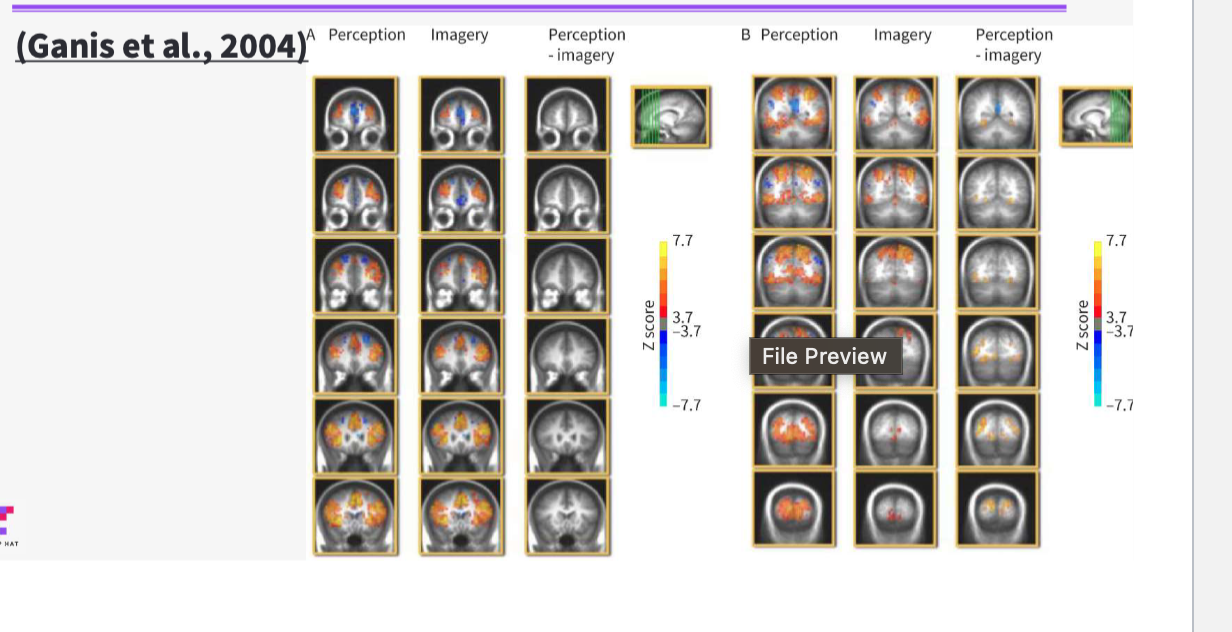

Imagery vs Perception: Overlap and Differences (Ganis et al., 2004)

Used newer neuroimaging techniques to re-examine brain activity in imagery vs perception.

Front of brain (planning, cognitive control, attention, memory) showed strong similarity for both imagery and perception tasks.

There was limited similarity in V1 because imagery happens with no actual visual stimulus.

Perception: stimulus hits receptor cells and travels up to early visual areas.

Imagery: a re-enacted perceptual experience where the same neurons are driven from frontal brain areas, not from input at the eyes.

Amedi et al., 2005 (Imagery is fragile)

During visual imagery, other nonvisual sensory areas (like auditory cortex) are deactivated.

During perception, these other sensory areas are not turned down.

Interpretation: imagery is more fragile than perception, so the brain “turns down” other senses to reduce interference with visual imagery.

Hub-and-Spoke Model: Neural Representation of Knowledge

Neuroimaging research shows that knowledge is represented through both general and modality-specific systems.

The anterior temporal lobe (ATL) acts as a semantic memory hub that stores generalized, abstract knowledge.

Modality-specific “spokes” store context-dependent sensory and motor details across the cortex.

This model helps explain why imagery studies sometimes show overlap and sometimes differences between imagery and perception.

MVPA (Multivoxel Pattern Analysis): Mind-Reading Imagery. Ragni et al. (2020)

Ragni et al. (2020) tested whether brain activity patterns during imagery can reveal what a person is imagining.

Participants viewed line drawings of lowercase letters, simple shapes, and objects.

Later, they imagined these same stimuli.

MVPA successfully identified which object people were imagining based on patterns of brain activity from both imagery and perception trials.

Shows that imagery produces distinctive and decodable neural patterns.

GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks)

GANs are a type of artificial neural network consisting of two competing parts:

Generator: trained to create new images that match presented examples.

Discriminator: trained to distinguish between real images and generated ones.

The two networks improve by competing with each other, leading the generator to create highly realistic images.

Goal: produce images that are indistinguishable from real ones to the point that they can fool human observers

“Deepfakes” use GAN-based systems to impersonate people in videos.

These videos can depict people doing or saying things they never actually did, raising ethical and social concerns.

Imagery Impacts Cognition and Behavior

The imagery debate is not fully resolved, but most researchers agree imagery is not stored only as propositions.

Imagery arises from brain mechanisms that overlap with perception.

Regardless of format, imagery influences cognitive functions and behaviors.

Examples include memory improvements such as the Picture Superiority Effect.

Picture Superiority Effect & Imagery Benefits for Memory

Imagery improves memory compared to verbal processing alone.

People remember pictures better than words.

This effect is especially strong when images are interactive, as shown by Bower (1970).

In Paivio & Csapo (1973), participants either:

read words or named pictures (verbal condition), or

formed visual images of words and pictures (imagery condition).

After a surprise memory test, performance was higher in the imagery condition than the verbal condition.

This demonstrates that imagery enhances encoding and recall.

Dual-Coding Explanation for Picture Superiority

Pictures automatically generate both an image code and a verbal label, giving two memory traces.

Words usually create only a verbal code, giving just one trace.

More memory codes → better recall.

Example from the slide: seeing a picture of mountains, clouds, and a hot air balloon produces both imagery and verbal labeling.

Concreteness Effect: Concrete Words Are Remembered Better

Concrete words (e.g., “apple”) are easier to remember than abstract words (e.g., “justice”).

Concrete words naturally elicit mental images, providing both image and verbal codes.

Abstract words are harder to visualize, so memory relies mostly on verbal encoding.

Parker & Dagnall (2009): participants heard lists of abstract and concrete words and were told they would later be tested on them.

Memory performance showed the concreteness effect under normal conditions.

Dynamic Visual Noise (DVN) Disrupts Imagery

Parker & Dagnall also tested memory while participants viewed either:

static visual noise, or

dynamic visual noise (DVN), which disrupts mental image formation.

DVN interfered with participants’ ability to create mental images.

Under DVN, the concreteness effect disappeared → concrete and abstract words were remembered equally well.

This supports the idea that imagery contributes to the memory advantage for concrete words.

Imagery and Mental Health (Holmes et al., 2005–2008)

Participants listened to short descriptions of events with either positive or negative outcomes.

Two groups:

Imagery group: created vivid visual images of the scenario.

Meaning group: focused on the meaning of the words only.

The imagery group reported stronger emotional reactions, including both higher anxiety for negative events and more positive emotion for positive events.

This shows imagery intensifies emotional experience because imagining an event engages perceptual-like systems.

Imagery and PTSD: Intrusive Negative Images

People with PTSD often experience involuntary, intrusive mental imagery of traumatic events.

Flashbacks include vivid visual and auditory imagery and can feel like the event is happening again.

These episodes trigger changes in the autonomic nervous system (e.g., heart rate increases, sweating).

Individuals with more vivid mental imagery are more likely to experience intrusive images after negative events.

Anxiety Disorders and Imagery

Anxiety disorders involve persistent and intense worrying that interferes with daily functioning.

People with anxiety often experience increased negative imagery of future events.

They believe these feared events are more likely to occur, which increases anxiety.

Excessive worrying is sometimes used as a coping strategy to reduce unwanted intrusive images.

Depression and Imagery

Depression includes persistent sadness and loss of interest.

Depressed individuals experience more negative imagery, especially imagery linked to suicidal thoughts.

They also experience reduced positive imagery, which may contribute to low mood.

Imagery Rescripting: Treating PTSD, Anxiety, and Depression

Imagery rescripting is a therapeutic technique for disorders involving harmful or intrusive mental imagery.

Patients revisit distressing memories and imagine acting differently, such as protecting their younger selves or changing the outcome.

The goal is to replace negative emotional responses with more adaptive ones.

Imagery-focused treatments have some of the highest success rates for PTSD and also help with anxiety and depression.

Individual Differences: Imagery Ability Varies Widely

People differ greatly in how vivid or detailed their mental images are.

Galton (1880) showed that some individuals describe vivid imagery while others report almost none.

Imagery ability can be measured using:

Self-report questionnaires (e.g., VVIQ),

Objective tasks like the Paper Folding Test (PFT), which tests spatial imagery.

The PFT requires mentally unfolding paper with holes punched in it to determine hole placement.

Aphantasia: Little or No Visual Imagery

Some individuals, such as patient MX, report no mental imagery at all following brain injury.

MX scored at the lowest level on imagery vividness tests, and fMRI showed inhibited activity in visual cortex regions.

After MX’s case was publicized, others reported lifelong absence of imagery, known as congenital aphantasia.

Aphantasia affects about 1–3% of the population.

Despite low imagery vividness, individuals with aphantasia often perform normally on spatial tasks, suggesting imagery vividness and spatial reasoning rely on different processes.

Hyperphantasia: Extremely Vivid Imagery

Hyperphantasia refers to extremely vivid and intense visual imagery.

It is likely much rarer than aphantasia.

Occupational trends:

Individuals with aphantasia are more likely to enter fields like mathematics or science.

Individuals with hyperphantasia are more likely to pursue creative professions.