BIOC 303 unit 2: Membrane biogenesis and protein trafficking

1/73

Earn XP

Description and Tags

2.1, 2.2, 2.3

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

74 Terms

signal sequences were discovered in the 1970s

The mRNA encoding a secreted protein was translated by ribosomes in vitro

Without microsomes, the protein synthesized was slightly larger than the secreted protein.

With microsomes, the protein synthesized was slightly shorter

This observation led to the signal hypothesis: there is a signal sequence that directs a protein to the ER membrane. When the protein is transported, the signal sequence is then cleaved off.

signal sequence=signal peptide=leader sequence=leader peptide

“Necessary and sufficient”: placing an ER signal sequence on a cytosolic protein redirects the protein to the ER

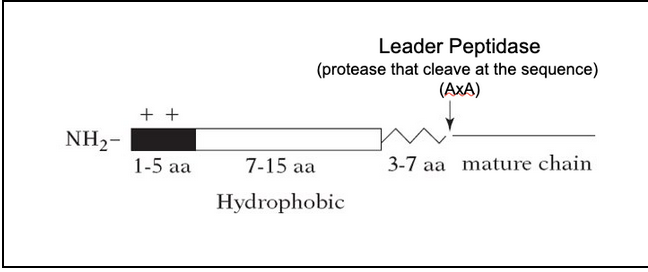

The signal sequence is a short N-terminal amino acid sequence, typically 20-25 residues

The sequences vary greatly in amino acid, but each has 7-15 nonpolar amino acids at its center, a positively charged N-terminal, a peptidase cleavage site located 3-7 aa after the hydrophobic sequence

There is no consensus sequence

The physical properties matter more than the exact amino acid sequence

Placing the N-terminal ER signal on a cytosolic protein redirects the protein to the ER

The signal sequences of all proteins having the same destination are interchangeable

Signal sequences are recognized by complementary receptors, called the translocon

Signal peptidases remove the signal sequence during or soon after the transport process is complete

Signal peptidases are located on the trans side of the membrane

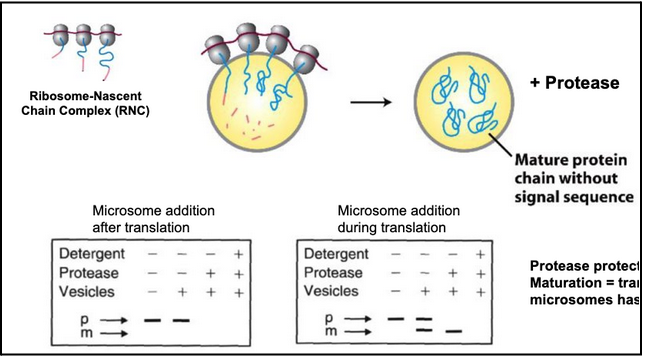

What did Blobel’s microsome experiment show, and how was the conclusion about co-translational translocation reached?

ER fragments reseal into microsomes, which retain ER functions (translocation, glycosylation, Ca²⁺ handling).

Radiolabeled precursor proteins (with signal sequences) were synthesized in vitro using ³⁵S-Met.

Protease protection assay used to test whether proteins enter microsomes:

Protein outside → digested by protease

Protein inside → protected unless detergent is added

Key result: Adding microsomes after translation → no protection, no signal peptide cleavage, no mature protein = no translocation.

Adding microsomes during translation → signal peptide is cleaved, mature protein appears, protease protection occurs = successful transport.

Conclusion: ER protein import requires microsomes to be present while the protein is being synthesized → transport is co-translational, not post-translational.

the signal recognition particle (SRP)

The SRP is an elongated particle made by six different polypeptides bound to a small RNS molecule (called ribonucleoprotein)

The elongated RNA acts like a scaffold to organize SRP proteins

One end interacts with the ribosome amino acid entry door. The other end interacts with the emerging signal sequence.

The signal-sequence-binding site is a hydrophobic pocket lined by methionine residues (Met have flexible side chains, plasticity allows recognition of various signal sequences)

One SRP can recognize many different signal sequences because the binding site is adaptable

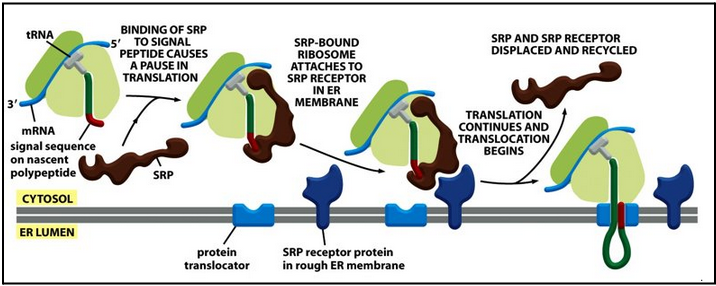

The signal recognition particle (SRP) stops protein synthesis

SRP binds to the emerging signal sequence and blocks entry of amino acids (with their tRNA) into the ribosome

Therefore, SRP blocks the translation of the protein (until the ribosome binds to the ER membrane)

SRP coordinates protein translation to protein translocation

SRP gives spatial and temporal resolution to the mechanism of translocation

SRP brings the RNC complex to the membrane (spatial effect)

SRP coordinates protein translation to protein translocation (temporal effect)

Note: tRNA allows the incorporation of amino acids into proteins

SRP directs nascent protein carrying a signal sequence to the SRP membrane receptor

The RNC complex is guided to the ER membrane by the signal-recognition particle (SRP)

The transient pause gives the ribosome enough time to bind to the ER membrane

The SRP-ribosome complex binds to the SRP receptor

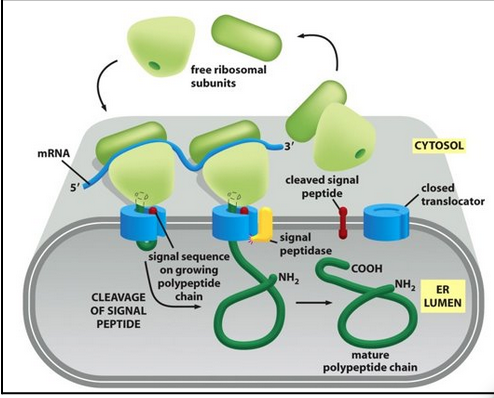

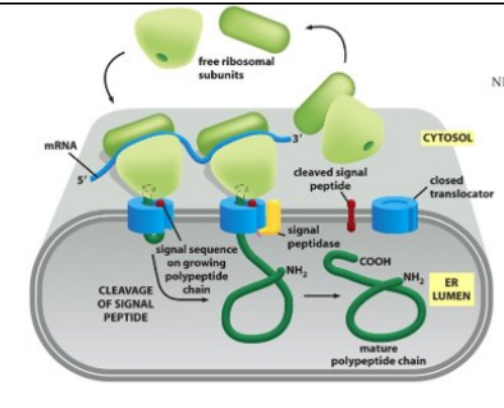

early model for co-translational translocation

The ribosome docks onto the ER membrane surface and “injects” the nascent polypeptide into the ER lumen. During or soon after transport, the ER signal sequence is cleaved off by a signal peptidase. The protein is then released in the ER lumen.

This model has a few major implications:

There must be a system that brings the RNC complex to the ER membrane → SRP

There must be a translocation channel that allows protein to traverse the membrane lipid bilayer → Sec61

The signal sequence must be inserted as a hairpin loop into the channel (signal peptidase on the other side of the membrane)

The signal peptidase is located on the trans side of the ER membrane

Protein must traverse the membrane in an unfolded state (no tertiary structure)

The SecY/Sec61 translocon

Prokaryotes: the SecY complex (SecY, SecE, SecG)

Eukaryotes: the Sec61 complex (Sec61𝛼, Sec61𝛽, Sec61𝛾)

The polypeptide chain is transferred through a membrane channel (called the translocon)

The translocon, also called the Sec61 complex, is made of 3 subunits

protein structure can be determined using x-ray diffraction

X-ray crystallography is the main technique to determine protein structure

X-rays are electromagnetic radiation with a short wavelength

If a beam of X-rays is directed across a pure protein, most of the X-rays pass through it

A small fraction, however, is scattered by the atoms in the sample

If the protein is well-ordered into a crystal, the scattered waves are well defined

Each spot in the diffraction pattern contains information about the locations of the atoms

Analysis of the diffraction pattern produces a complex 3D electron-density map

The sequence and the density map are fitted together by computer

The 3D structures of about 20,000 different proteins have been determined by X-ray crystallography

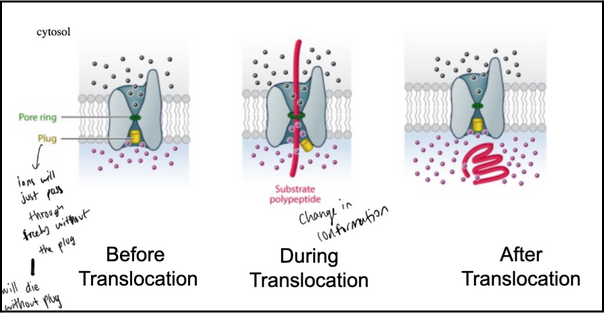

What structural features of the SecY/Sec61 translocon maintain membrane integrity during protein translocation?

The translocon contains a “plug” that seals the channel when no protein is entering; removing this plug is lethal, because the membrane becomes permeable to ions and loses its barrier function.

A pore ring made of hydrophobic amino acids forms a tight gasket around the translocating polypeptide, preventing ion leakage even while the chain passes through.

Together, the plug and the hydrophobic pore ring ensure the channel is ion-tight both at rest and during protein translocation.

type I membrane protein

Insertion of a single-pass membrane protein

The hydrophobic sequence following the signal sequence is called the stop-transfer sequence

The stop-transfer sequence remains in the lipid bilayer as a membrane-spanning alpha-helix (i.e. to become a transmembrane segment).

Glycophorin A is a typical example of this type of membrane protein topology

Human GH receptor is another example

Biogenesis of membrane protein type I

20 hydrophobic amino acids = TMS = “Stop-transfer sequence”

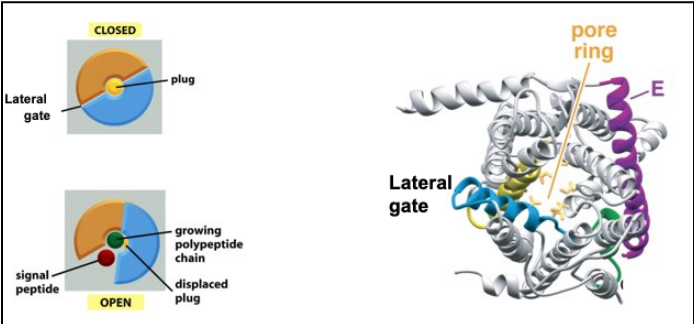

How does the lateral gate of the SecY/Sec61 translocon function, and what structural features enable its role in membrane protein insertion?

The lateral gate lies at the interface between TM2 (N-terminal half, blue) and TM7 (C-terminal half, yellow) of the SecY/Sec61α subunit.

SecY/Sec61 has two-fold symmetry, with N-terminal and C-terminal halves that can separate; Secβ/SecG and SecE stabilize the complex.

The main pore (for translocating polypeptides) is formed by the central Sec61α/SecY subunit, and is normally blocked by a plug helix.

During translocation, the channel can open laterally toward the lipid bilayer — a seam between TM2 and TM7 forms the gate.

Signal peptides insert into this lateral gate above the plug, while transmembrane segments (TMSs) of nascent membrane proteins exit through this opening into the bilayer.

Lateral release requires the two halves of SecY to swing open around a hinge in loop 5/6, creating a slit that allows hydrophobic segments to partition into the membrane.

This mechanism ensures that hydrophobic domains are inserted into the lipid bilayer while the rest of the chain continues through the pore, enabling co-translational membrane protein integration.

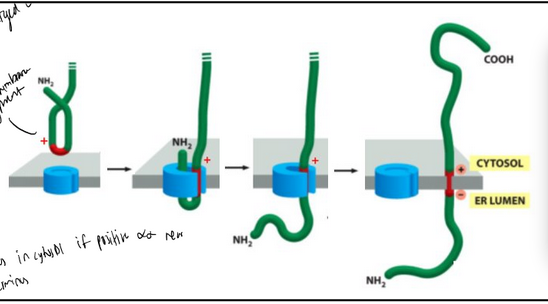

Membrane proteins are not always made with a signal sequence. Then how do they get into the membrane?

There is a signal-anchor sequence near the N-ter of the protein, also called the start-transfer sequence. It is actually a TMS that is recognized by SRP.

membrane protein type II

N-terminus stays in the cytosol

The “start-transfer” sequence (which is actually the TMS) is recognized by SRP

The sequence is inserted into the channel as a hairpin loop

Orientation depends on the location of the + charged residues near the TMS

membrane protein type III

C-terminus stays in the cytosol

Two modes of insertion are possible:

“NH2 in” (Type II)

“NH2 out” (Type III)

Orientation depends on positive/negative amino-acid charge distribution around the signal anchor sequence. Positive charges tend to remain on the cytosolic side of the membrane (it is proposed that negatively charged lipids are present around the translocation channel).

membrane protein topology follows the “positive-inside rule”

The positive amino acids located before the TMS are controlling the hairpin orientation

“Positve” means positively charged amino acids

“Inside” means inside the cell ie. cytosol

“Rule” means a consistent principle

How does a single-pass membrane protein insert into the ER membrane, and what determines its final orientation (topology)?

A single-pass membrane protein inserts through an internal signal sequence (signal-anchor) that both initiates translocation and becomes the membrane-spanning α-helix. Key features:

Internal signal sequence (hydrophobic, ~20–25 aa) is recognized twice:

→ by SRP during translation

→ by the Sec61 translocon, which engages both the pore and the lipid bilayerLateral gate of Sec61 opens to allow the hydrophobic helix to exit sideways into the membrane; the translocator is gated across the membrane and into the membrane.

Biogenesis requires dual gating: part of the protein may translocate into the lumen while the TMS embeds in the bilayer.

Final orientation (Type II vs. Type III) is determined by the positive-inside rule:

→ Regions with more positive charges remain on the cytosolic side.

→ Charge distribution around the TM segment dictates whether the N-terminus or C-terminus faces the lumen.Location of signal(s) and proximity to additional hydrophobic segments (e.g., stop-transfer sequences) also determine topology.

model for co-translational translocation

The ribosome docks onto the ER membrane surface and “injects” the nascent polypeptide into the ER lumen. During or soon after transport, the ER signal sequence is cleaved off by a signal peptidase. The protein is then released in the ER lumen.

The signal peptidase active site is facing the ER lumen

The cleaved signal peptide is not stable (too small) and is rapidly degraded

The “crack” located sideways on the translocon is the lateral gate

Multi-pass membrane proteins (Type IV)

The biogenesis of multi-pass membrane proteins depends on start-transfer and stop-transfer sequences

Multi-spanning membrane proteins pass back and forth through the lipid bilayer. The internal signal sequence serves as a start-transfer signal to initiate translocation. Translocation continues reaching a stop-transfer sequence.

In complex multipass proteins, a second start-transfer sequence initiates translocation, and so on for subsequent start-transfer and stop-transfer sequences

SRP scans for the first hydrophobic segment that emerges from the ribosome. A similar scanning process continues until all of the hydrophobic regions are inserted

Ex. GLUT1

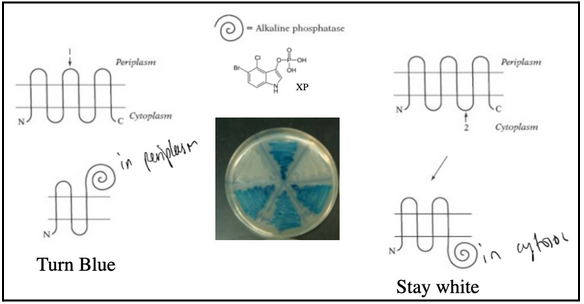

use of a reporter enzyme

Alkaline phosphatase hydrolyzes a substrate called XP. Substrate XP is membrane impermeable. When alkaline phosphatase is transported to the periplasm, the substrate XP is hydrolyzed, and it turns blue.

When alkaline phosphatase is fused at the end of TM3, bacteria are blue

When alkaline phosphatase is fused at the end of TM4, bacteria are white

Bacterial colonies are blue when alkaline phosphatase is exposed to the periplasm and are white when alkaline phosphatase remains in the cytosol.

Note: negative results do not provide evidence; need to verify results with complementary techniques

Possible explanation for the “positive-inside” rule

Effect of negatively charged phospholipids located in the inner leaflet (asymmetric bilayer)

In bacteria, the effect of the proton gradient (charge separation creating dipole across the membrane)

Charge differences occurring around the membrane can explain the “positive-inside rule” for signal peptide translocation and topology

The cytoplasmic half of the phospholipid bilayer contains negatively charged phospholipids that may interact with the positively charged N-region of a signal peptide

The proton gradient across the bilayer creates a positively charged, acidic environment at the outside and a negatively charged, basic environment at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane

The charge gradient is unfavourable for the translocation of positively charged residues in the N-region

Membrane protein insertion in bacteria

Like in the ER, the insertion of membrane proteins in the IM of bacteria depends on the SRP and Sec complex.

can a beta strand act as a stop-transfer sequence?

The 𝛽-strand is not acting as a stop-transfer sequence

It is not hydrophobic enough to be a stop-transfer

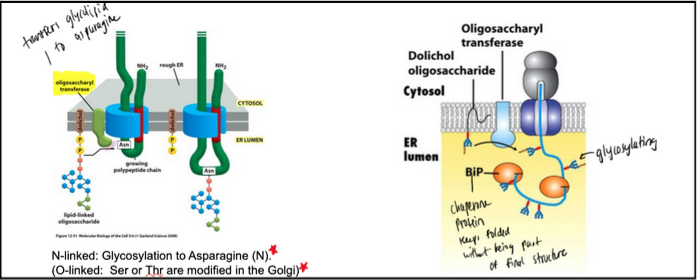

What is the role of the oligosaccharyl transferase (OST) complex in the ER, and how does N-linked glycosylation occur?

As nascent proteins enter the ER lumen (mostly unfolded), chaperones like BiP (an ATPase) assist in folding and stabilizing them; BiP also helps pull proteins during post-translational translocation.

The OST complex, embedded in the ER membrane, transfers a pre-assembled 14-sugar oligosaccharide onto specific asparagine residues in the sequence N-X-S/T → this is N-linked glycosylation.

The oligosaccharide is held by dolichol phosphate, a membrane lipid that carries the sugar tree via a high-energy pyrophosphate bond.

Because OST is in the ER lumen, glycosylation occurs only on the non-cytosolic side of membranes; thus, about 50% of eukaryotic proteins become glycosylated.

Glycosylation helps form a protective carbohydrate layer on secreted and membrane proteins, shielding cells from mechanical and chemical stress.

A minority (~10%) of glycosylation events involve O-linkage to serine or threonine → these O-linked sugars are added in the Golgi, not the ER.

Summary:

N-linked: Asn (ER, via OST)

O-linked: Ser/Thr (Golgi)

What is BiP and what roles does it play in the ER?

BiP is an Hsp70-family ATP-dependent chaperone located in the ER lumen.

It binds to exposed hydrophobic regions on nascent or misfolded proteins, preventing aggregation and assisting proper folding and assembly.

During post-translational translocation, BiP acts as a molecular ratchet: it hydrolyzes ATP to pull newly synthesized polypeptides into the ER lumen.

BiP helps maintain quality control, interacting with unfolded proteins and participating in the unfolded protein response (UPR) when misfolded proteins accumulate.

It ensures proteins achieve correct conformation without becoming part of the final structure.

What does PDI do, and why is it active only in the ER?

protein disulfide isomerase

PDI catalyzes the formation, breakage, and rearrangement of disulfide (S–S) bonds in newly made proteins.

Disulfide bonds provide structural stability, especially for secreted and membrane proteins.

The cytosol is a reducing environment, so S–S bonds rarely form there; the ER lumen is oxidizing, which allows PDI to function.

Disulfide bonds occur only on the non-cytosolic side of membranes because PDI and the oxidizing environment are found there.

Why are sugar chains found only on the extracellular / luminal side of membrane proteins?

Glycosylation enzymes (OST in the ER, and other glycosyltransferases in the Golgi) are located in the lumen, never in the cytosol.

Because the luminal side becomes the extracellular side after vesicle fusion, sugars always end up facing outward.

As a result, most membrane proteins in animal cells are glycosylated only on their non-cytosolic regions.

What roles do oligosaccharides on glycoproteins play?

Form a protective carbohydrate coat against mechanical and chemical damage.

Contribute to protein stability and proper folding.

Their enormous structural diversity makes them essential for cell–cell recognition processes like:

sperm–egg interactions

blood clotting

lymphocyte homing

inflammation

Oligosaccharides also act as folding tags that reflect the maturation state of the protein.

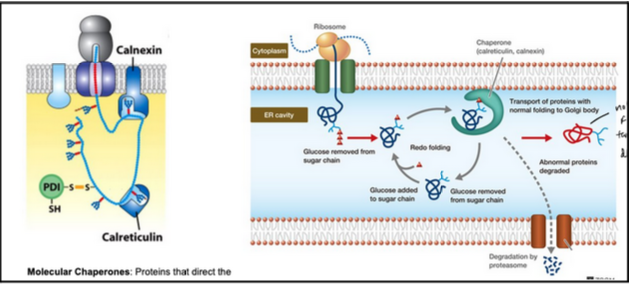

the chaperones calnexin/calreticulin (folding quality control)

Molecular chaperones: proteins that direct the correct folding and assembly of polypeptides without being components of the final structure. Chaperones can maintain protein into an unfolded state.

They hold and fold glycoproteins by recognizing an “inspection tag” → a monoglucose at the end of a glycan

Removal of the terminal glucose by a 𝛽-glucosidase releases the protein from calnexin

If still incompletely folded, the glycosyl-transferse adds new glucose to the oligosaccharide

The new glucose increases protein affinity for calnexin

The cycle repeats until the protein has folded completely

Only when the glucose is removed, the protein leaves the ER

Clanexin and calreituclin belong to the family of lectins (sugar binding proteins)

Improperly folded proteins are exported from the ER and degraded in the cytosol

More than 80% translocated proteins into the ER fail to achieve a properly folded state

Such proteins are exported back into the cytosol, where they are degraded

How to select proteins from the ER for degradation?

N-linked oligosaccharides serve as timers for how long a protein has spent in the ER

Summary: protein modifications during transport

Glycosylation

Disulphide bond formation

Folding and oligomerization

hemagglutinin

Influenza hemagglutinin (HA) is a type of hemagglutinin found on the surface of influenza viruses. It is an antigenic glycoprotein. It is responsible for binding the virus to the cell that is being infected. The name "hemagglutinin" comes from the protein's ability to cause red blood cells to clump together ("agglutinate") in vitro.

The GPI-anchor (glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol)

Some membrane proteins acquire glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor

An ER (GPI-transamidase) attaches a GPI anchor to the C-terminus of some membrane proteins that exit the translocon

This linkage occurs in the ER when the C-terminal transmembrane segment is cleaved off

Some plasma membrane proteins are modified in this way

Advantages:

Release of the protein from the membrane is easy

Example: in response to signals that activate a membrane phospholipase

Faster diffusion on the lipid bilayer than TM segments

Preferential localization of plasma membrane proteins into lipid rafts, along with other proteins

Example: trypanosomes shed their coat of GPI-anchored surface proteins when attacked by the immune system.

Example of GPI protein: The VSG protein (variable surface glycoprotein: antigenic variation)

The VSG protein forms a coating layer at the surface of the parasite

The parasite escapes the immune system by rapidly changing the VSG coat

How? A phosphtifylinositol-phospholipase C (PI-PLC) rapidly removed the VSG coat from the cell surface (hydrolyze the P-bond of the GPI anchor) → surface shedding for antigenic variation

Trypanosoma Brucei, responsible for the “sleeping sickness”

The parasite is able to cross the blood-brain barrier

The surface of the trypanosome is covered by a coat of Variable Surfacce Glycoprotein (VSG)

The VSG coat prevents the immune system from accessing the plasma membrane surface epitopes (such as ion channels, transporters, receptors etc.) of the parasite. Therefore, the immune system can only “see” the N-terminal loops of the VSG. This coat enables the parasite to persistently evade the host’s immune system, allowing chronic infection.

In addition there is periodic antigenic variation: The VSG coat undergoes frequent genetic modification - 'switching' – allowing the expression of a new VSG coat to escape the specific immune response raised against the previous coat. This is possible because of the rapid cleavage of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor by a phosphatidylinositol-phospholipase C (PI-PLC).

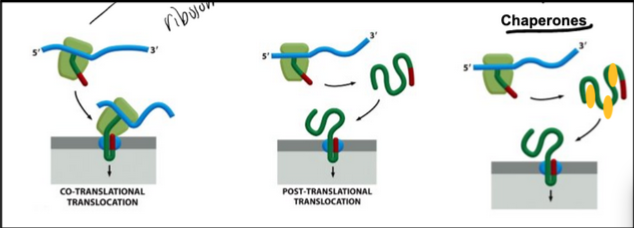

Two modes of protein translocation

Co-translational translocation

Post-translational translocation

Very common in yeast and in bacteria

Diverse chaperone proteins are involved in post-translational translocation. Their role is to maintain the target proteins in a loosely folded state (fully folded structures cannot cross the translocation pore!)

BiP; the driving force in post-translational translocation → eukaryotes (yeast)

Translocation across the ER membrane does not always require ongoing polypepitde chain elongation

Translocation across the ER membrane occurs during translation (co-translationally)

Explains why ribosomes are bound to the ER but usually not to other organelles

Post-translational translocation is very common in yeast and in bacteria

The translocator needs accessory proteins that feed the polypepitde chain into the pore

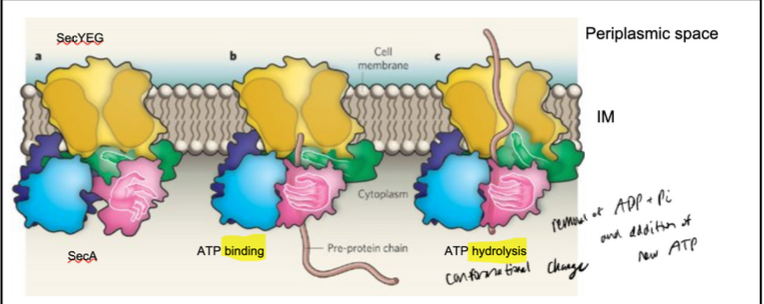

In bacteria, the SecA ATPase push the protein across the SecY complex (ratchet)

In yeast, chaperone BiP binds the polypeptide chain as it emerges from the pore (pull)

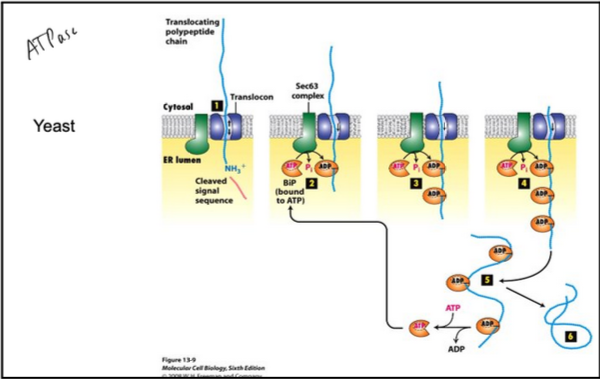

How does BiP mediate post-translational translocation of proteins into the ER lumen? (steps)

Polypeptide Binding to Sec Complex:

Completed polypeptide binds Sec complex (Sec61 + Sec62/Sec63).

Chaperones previously bound to the polypeptide are released.

BiP Engagement:

ATP-bound BiP interacts with the J-domain of Sec63.

ATP hydrolysis converts BiP to its ADP-bound form, tightly binding the polypeptide.

This prevents backward movement of the polypeptide into the cytosol.

Stepwise Translocation:

As the polypeptide moves further into the ER lumen, additional BiP molecules bind sequentially.

This ratchet-like process continues until the entire chain enters the ER.

Release of BiP:

Nucleotide exchange (ADP → ATP) releases BiP from the fully translocated polypeptide.

ATP: the driving force in post-translational translocation → bacteria

SecA is a processive enzyme: it catalyzes multiple consecutive reactions on a single substrate molecule without releasing it after each catalytic cycle (e.g. DNA/RNA polymerase)

Pink hand: preprotein-binding domain

Green finger: alpha-helix domain

Blue: ATP binding domain

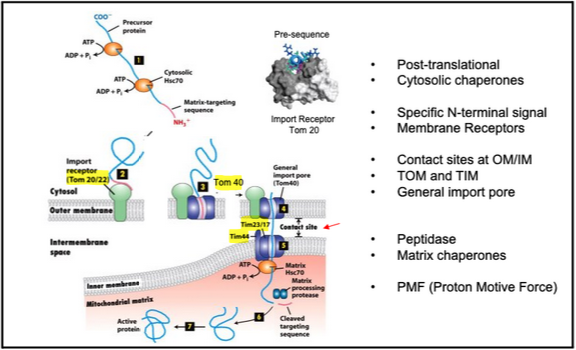

mitochondria have TIM and TOM

Precursor proteins synthesized on cytosolic ribosomes are maintained in an unfolded state by chaperones, such as Hsc70

After binding to the import receptor, the precursor is transferred into the general import pore (TOM for Translocator of Outer Membrane Mitochondria)

Note that translocation occurs at “contact sites” at the inner and outer membranes (Tom and Tim). The matrix chaperone Hsc70 and subsequent ATP hydrolysis help drive import into the matrix.

The targeting signal is VERY different from a signal sequence: it is moderately amphipathic and is recognized by a specific receptor that binds to the TOM complex. What matters is the specific recognition of the signal by this receptor (i.e. protein-protein interaction)

How are β-barrel proteins (porins) inserted into the mitochondrial outer membrane?

TOM Complex (Translocase of the Outer Membrane):

Imports porins into the intermembrane space but cannot insert them into the membrane directly.

Chaperone Binding:

In the intermembrane space, porins bind specialized chaperones to remain unfolded and prevent aggregation.

SAM Complex (Sorting and Assembly Machinery):

Receives porins from chaperones.

Inserts them into the outer membrane as β-barrel proteins.

Evolutionary Note:

Central SAM subunits are homologous to bacterial BAM complex, supporting the endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria.

Key Concept: Mitochondrial outer membrane β-barrel proteins require sequential import (TOM → chaperones → SAM) for proper insertion.

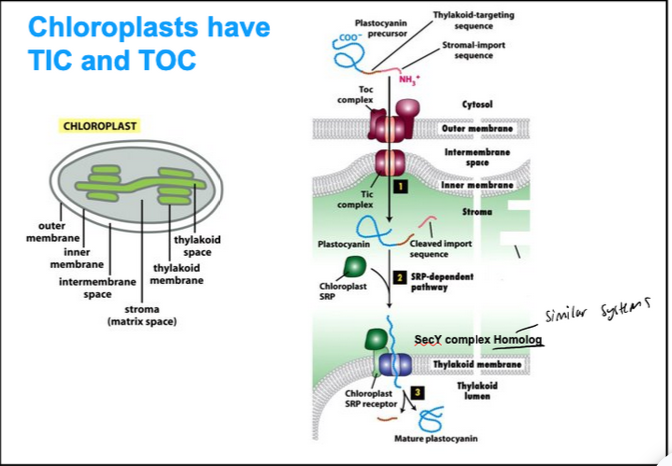

Chloroplasts have TIC and TOC

Two signal sequences direct proteins to the Thylakoid membrane in chloroplasts

Protein transport into chloroplasts resembles transport into mitochondria

Post-translational mode of translocation

Signal sequences for import into chloroplasts resemble those for mitochondria

The import receptors and transporters are TIC and TOC, homologous to TIM and TOM

Chloroplasts have an extra membrane-enclosed compartment, the thylakoid

The photosynthetic system is located in the thylakoid membrane

Precursors have a thylakoid signal sequence followed by a chloroplast signal sequence

Transport of these precursor proteins occurs in two steps:

First, they pass across the double membrane at special contact sites

Second, they translocate into the thylakoid membrane or into the thylakoid space (via a system similar to SRP and SecYEG of bacteria)

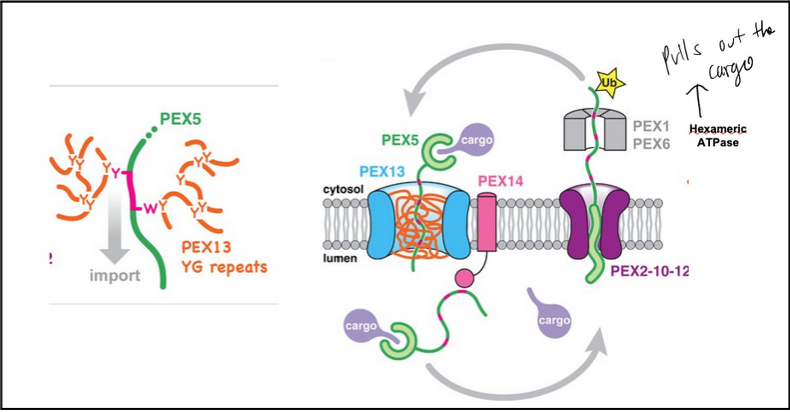

What are the key properties of peroxisomes, their targeting signals, import machinery, and major metabolic functions?

General Features

Present in all eukaryotic cells

Surrounded by a single membrane

Site of long-chain fatty acid oxidation (β-oxidation → acetyl-CoA)

Major site of oxygen utilization

Contains a limited but concentrated set of enzymes (e.g., catalase, urate oxidase)

Ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde here

Proteins are imported post-translationally from the cytosol

Targeting & Import Machinery

Peroxisomal Targeting Signal (PTS1):

C-terminal tripeptide SKL (Ser-Lys-Leu)

Major import signal for peroxisomal matrix proteins

Peroxins (PEX proteins):

~23 distinct PEX proteins involved

Mediate recognition, docking, and translocation

Pex5 receptor:

Recognizes PTS1 signal

Accompanies cargo into the peroxisome

Cycles back to the cytosol after delivery

Import mechanism is poorly understood, but uniquely:

Polypeptides enter fully folded, unlike mitochondria/ER

What disease results from defective peroxisomal protein import?

Zellweger syndrome

Caused by defective peroxisomal protein import

Results in “empty peroxisomes”

Leads to severe neurological defects

Typically fatal shortly after birth

Hyper-oxaluria: mistargeting aminotransferase

Oxalate stones in kidneys

In some inherited diseases, proteins are mislocalized in the cell due to erriors in targeting signals and transport. One example is “primary hyperoxaluria,” a rare disease which results in kindey stones at an early age.

A signal in the enzyme alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase normally directs it to the peroxisome. In patients, this signal is altered and the protein is mislocalized to the mitochondrion, where it is unable to perform its normal function.

How does PEX13 form a pore in the peroxisomal membrane?

PEX13 forms a dodecameric ring (12 subunits) using its long amphipathic helix (AH).

Helices are tilted and arranged in alternating orientations.

Hydrophobic sides face outward into membrane lipids; hydrophilic sides face the internal channel.

The ring embeds into the membrane to create an aqueous pore.

What is the function of the PEX13 YG domain?

The Tyr/Gly-rich YG domain extends from each PEX13 subunit into the pore, forming a dense hydrogel meshwork similar to nuclear pore FG domains.

WT YG domain gels due to cohesive tyrosine–tyrosine interactions.

Mutating Tyr → Ser abolishes gelation, proving tyrosine-based cohesion is essential.

How does PEX5 (with cargo) move through the PEX13 pore?

PEX5 contains WxxxF/Y motifs that allow it to transiently disrupt the tyrosine-based interactions inside the YG hydrogel.

By breaking and reforming these interactions, PEX5 can partition into and traverse the hydrogel, enabling cargo import into the peroxisome.

How does PEX5 interact with and permeate the PEX13 YG-hydrogel?

PEX5 is the cytosolic receptor that binds peroxisomal cargo containing the SKL (PTS1) signal. Its N-terminal region contains multiple WxxxF/Y aromatic motifs, which are essential for moving through the PEX13 YG-domain hydrogel.

YG-hydrogel droplets (40 mg/mL) are permeated selectively by PEX5: fluorescent PEX5-GFP fusion proteins rapidly accumulate inside the gel, whereas GFP alone does not.

This selectivity occurs because π–π stacking interactions between PEX5’s aromatic residues and the YG-domain’s Tyr-rich meshwork allow PEX5 to transiently disrupt and re-form the cohesive network, enabling its passage through the pore during peroxisomal import.

the PEX transport cycle steps

Cargo Binding: PEX5 in the cytosol binds PTS1-containing cargo via its TPR domain.

Docking: Cargo-bound PEX5 is recruited to the peroxisomal membrane docking complex (PEX13/PEX14) using WxxxF/Y motifs.

Translocation: PEX5 and cargo move into the peroxisomal lumen. Diffusion back is prevented by high-affinity interactions with the lumenal PEX14 and the YG hydrogel of PEX13.

Export Initiation: PEX5’s amphipathic N-terminal helix inserts into the PEX2/PEX10/PEX12 ligase pore.

Monoubiquitination: Conserved cysteine in PEX5 is ubiquitinated.

Extraction & Cargo Release: PEX1/PEX6 AAA ATPase pulls PEX5 out of the lumen, unfolding the TPR domain and releasing cargo.

Refolding & Reset: In the cytosol, PEX5 refolds and ubiquitin is removed by deubiquitinases, resetting it for another import cycle.

What are the key features of transport across the nuclear envelope, and how does this relate to the structure and functions of the ER?

Nuclear Envelope Structure:

Encloses DNA with two membranes: an inner membrane (binds chromatin + nuclear lamina) and an outer membrane (continuous with ER).

Perforated by nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) that allow massive bidirectional traffic.

Nuclear Transport:

Proteins made in the cytosol (histones, polymerases, gene regulators, RNA-processing proteins) imported into nucleus.

RNAs made in nucleus (tRNA, mRNA) exported to cytosol.

Transport is continuous and highly regulated.

ER Structure:

Network of tubules + sacs; outer nuclear membrane transitions into ER membrane.

Rough ER: ribosome-studded; major site of protein synthesis, including all secreted proteins and all transmembrane proteins.

Smooth ER: lacks ribosomes; abundant in lipid-metabolizing cells; stores drugs-metabolizing enzymes (cytochrome P450); major site of lipid synthesis and Ca²⁺ storage.

Transitional ER: smooth regions where transport vesicles bud off toward the Golgi.

Functional Summary:

ER produces proteins, lipids, and Ca²⁺ stores for the whole cell.

Sends cargo to the Golgi for further processing.

In hepatocytes, ER surface area can be 25× larger than plasma membrane.

What structural features of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) create selective permeability, and how do FG fibrils form the gate?

Eukaryotic cells have 3000–4000 NPCs, each built from ~30 nucleoporins.

NPC spans two membranes but is suspended outside the bilayer rather than embedded (unlike PEX pores).

Central channel filled with disordered FG-nucleoporins containing Phe-Gly repeats.

FG repeats form a hydrophobic meshwork (hydrogel) primarily held together by phenylalanine interactions.

This mesh creates a size barrier: proteins >60 kDa cannot passively diffuse; ribosomes (~30 nm) cannot diffuse at all.

Acts as a filter—non-specific proteins are blocked, while transport receptors can penetrate the FG mesh.

How do NLS signals and nuclear transport receptors (importins) mediate movement through the FG-gated NPC?

Proteins must contain a Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS):

Typically rich in positively charged Lys/Arg residues.

Can appear anywhere in the protein (loop or exposed patch).

Works in fully folded proteins—NPC does not require unfolding.

Importins (NTRs) recognize specific classes of cargo and bind:

The NLS on cargo

FG fibrils inside the NPC

Importins move through the pore by transient hydrophobic interactions with FG residues (mainly phenylalanines), “hopping” from one FG repeat to the next.

Directionality is controlled by Ran-GTP system (Ran-GEF in nucleus, Ran-GAP in cytosol).

Some proteins continually shuttle, and their steady-state location depends on relative import vs. export rates.

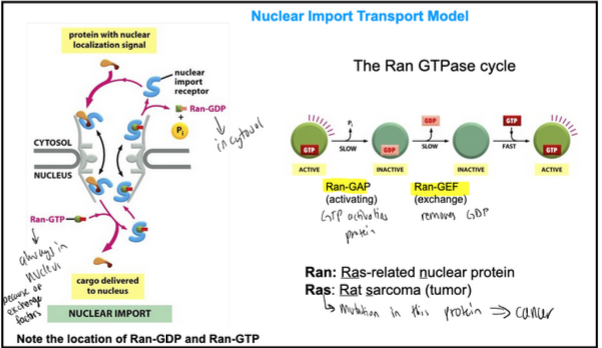

Nuclear import transport model

Ran stands for Ras-related nuclear protein

Ras stands for rat sarcoma

Ras is a small GTPase. Mutations that permanently activate Ras are found in 20-25% of all human tumours.

Ran-GDP is in cytosol and Ran-GTP is in the nucleus

Ran-GAP is the GTP activating protein

Ran-GEF is the exchange protein that removes GDP

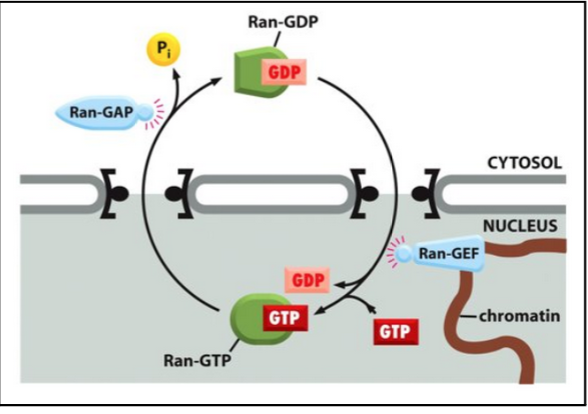

The Ran cycling mechanism

Translocation through the pore is not energy-dependent. The cargo passes through the pore with the assistance of importings. However, the whole import cycle needs the hydrolysis of GTP (but this is not to produce energy per se).

The driving force for transport depends on the gradient of Ran-GTP

The gradient of Ran-GTP is made because of the preferential location of Ran-GEF and Ran-GAP

These two regulatory proteins trigger the conversion between the 2 states:

A GTPase-activating protein (Ran-GAP) triggers GTP hydrolysis

A GTP exchange factor (Ran-GEF) promotes the exchange of GDP to GTP

Ran-GAP is preferentially located in the cytosol, and Ran-GEF is located in the nucleus.

Ran-GAP: GTP hydrolysis activating protein

Ran-GEF: GTP exchange factor protein

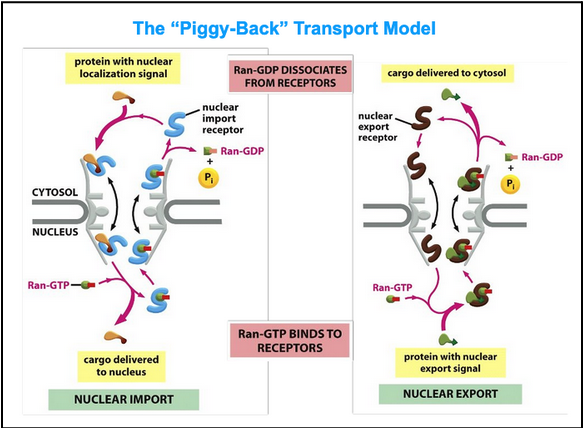

the “piggy-back” transport model

Import

Ran-GTP binds to the importin on the nuclear side of the pore

Ran-GTP binding causes the receptors to release their cargo

The importin with Ran-GTP is transported back to the cytosol

Ran-GAP in the cytosol triggers the hydrolysis of GTP, thereby converting it to Ran-GDP

The import receptor is then ready for another cycle of nuclear import

Export

Ran-GTP in the nucleus promotes cargo binding to the export receptor

In the cyotol, Ran-GTP hydrolyzes GTP

The export receptor releases both its cargo and Ran-GDP in the cytosol

Free export receptors are then returned to the nucleus to complete the cycle

In fact, the import cycle is powered by a Ran-GTP gradient across the pore

This gradient arises because of the exclusive nuclear localization of proteins called Ran GEFs

These proteins exchange GDP for GTP on Ran molecules

There is an elevated RanGTP concentration in the nucleus compared to the cytoplasm

secretion of insulin in pancreatic beta-cells

High glucose content in the cell (hence the ratio ATP/ADP) triggers insulin release

Secretory and membrane proteins become concentrated because of an extensive retrograde retrieval process. The final mature secretory vesicles are so densely filled with contents, the secretory cell can disgorge large amounts of material promptly by exocytosis

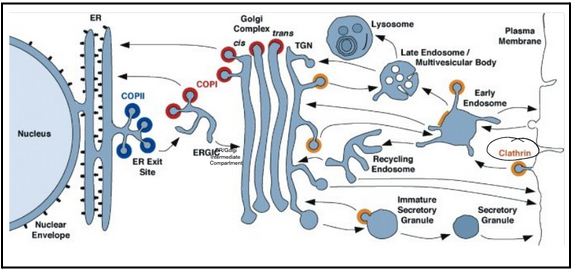

three types of membrane vesicles

Clathrin vesicles mediate transport from the Golgi apparatus and from the plasma membrane

COPI-coated vesicles bud from Golgi compartments

COPII-coated vesicles bud from the ER

Anterograde pathway (COPII vesicles)

Retrograde pathway (COPI vesicles)

Endocytosis (Clathrin vesicles)

All compartments are interconnected via vesicle trafficking

Proteins are successively modified as they pass through a series of compartments

Some vesicles select cargo molecules and move them to the next compartment

Some vesicles retrieve escaped proteins and return them to a previous compartment

The biosynthetic secretory pathway is a continuous flow of material

The clathrin triskelion (3 legs)

The major protein component of clathrin-coated vesicles is clathrin

Clathrin form a three-legged structure called triskelion

Isolated triskelions spontaneously self-assemble into typically polyhedral cage

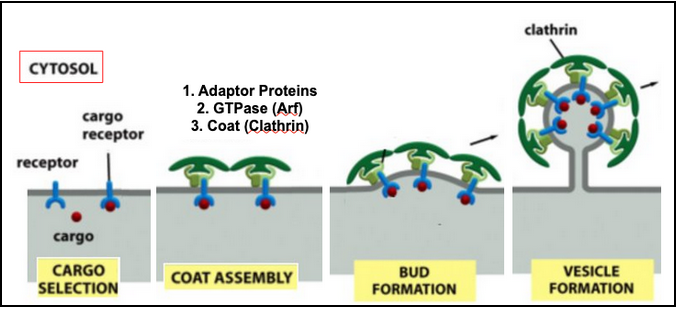

Stage I - Vesicle Formation

Adaptor proteins (AP) form a discrete second layer between the clathrin cage and the membrane

AP trap transmembrane receptors that capture soluble cargo molecules

There are several types of adaptor proteins, each specific for a subset of receptors

Arf belongs to the family of small monomeric GTPase

Stage II - fission and uncoating

Soluble proteins, including dynamin, assemble as a ring around the neck of the bud

Dynamin contains a GTPase domain, which regulates the rate of pinching off

Dynamin forces the noncytosolic leaflets of the membrane to fuse

Dynamic recruits other proteins at the budding vesicle, which help to bend the patch of membrane (distort the bilayer structure, change its lipid composition, including phospholipases)

Once released from the membrane, the vesicle rapidly loses its clathrin coat under the action of ARF GTPase

The clathrin monomers and AP proteins are recycled

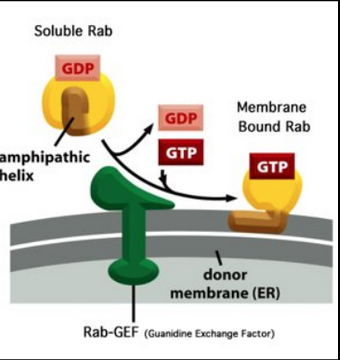

Stage III - Recruitment of Rab GTPase; Stage IV: Targeting and Fusion

Membrane-bound Rab proteins bind to Rab effectors on the target membrane

Some Rab effectors are tethering proteins wth threadlike domains that serve as “fishing lines” extending 200nm above the membrane surface

Stage III continued

Rab proteins are the largest subfamily of small GTPase (60 members) → PIPs control the binding specificity to the vesicle

The selective distribution of Rab proteins at the surface of the vesicles guides vesicular traffic

Target membranes have complementary receptors (termed Rab effector)

PIP (inositol lipids) are important for the selective distribution of Rab at the membrane

PIPs lipids + Rab GEF control Rab binding specificity

The subcellular localization of various forms of PIs is governed by the presence of lipid kinases and phosphatases. This reflects the fact that different organelles have different levels/forms of kinases and phosphatases. Almost all of the kinases and phosphatases are on the cytosolic side of the organelle. Some of these proteins are integral, while some are peripheral membrane proteins.

Rab-GEF present in the “donor” membrane

Phosphatases and kinases are organelle specific

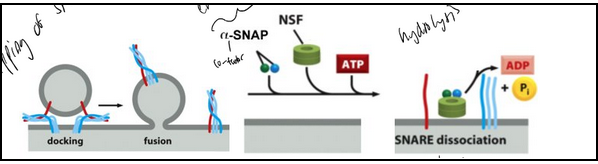

Forces applied by the SNAREs

SNARE motif: 60-70 amino acids with heptad repeats that can form coiled-coil structures (alpha-helices wind around each other like the strands of a rope). The “zipper model.”

Stage V: Recycling SNAREs

Key Players:

SNAREs (SNAP receptors): mediate membrane fusion.

NSF (N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor): AAA ATPase that hydrolyzes ATP to dissociate SNAREs.

α-SNAP (Soluble NSF Attachment Protein): binds SNAREs and recruits NSF.

NEM: inhibits NSF by modifying cysteine residues.

Mechanism (“Socket and Wrench”):

α-SNAP binds assembled SNAREs (the “socket”).

NSF (the “wrench”) hydrolyzes ATP repeatedly, pulling apart SNARE complexes.

NSF Structure: Hexamer of identical subunits.

Key Concept: ATP-driven disassembly by NSF/α-SNAP resets SNAREs for another round of membrane fusion.

Botullinic toxin from clostridium botulinum

Tetanus and botulism are neurotoxins that cleave SNARE proteins in the nerve terminals. These toxins block synaptic transmissions.

The LD50 of tetanus toxin (produced by the bacteria clostridium) has been measured to be approximately 1 ng/kg, making it one of the deadliest toxins in the world. The toxin blocks specifically the SNAREs found in the inhibitory neurons.

Calcium binding to synaptotagmin triggers fusion

Molecular machinery driving exocytosis in neurotransmitter release: the core SNARE complex (formed by four 𝛼-helices contributed by synaptobrevin, syntaxin and SNAP-25) and the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin.

Synaptotagmin binding to the SNARE complex causes the fusion clamp to tighten further and also creates additional disturbances in the lipid blayer. This terminates the vesicle fusion process upon binding calcium. Synaptotagmin therefore acts like a Ca sensor.

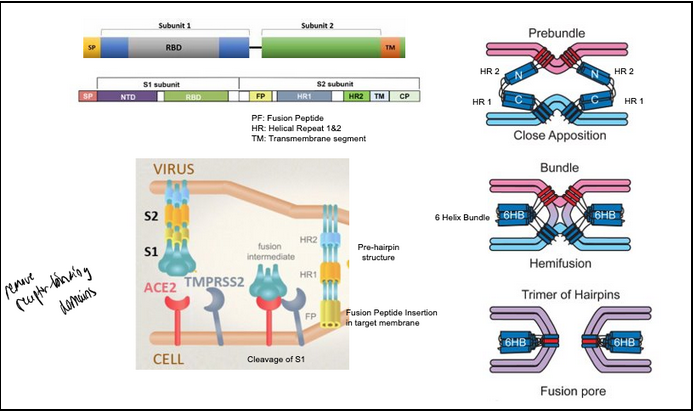

How does the spike protein work?

SARS-CoV spike protein schematic.

The spike protein ectodomain consists of the S1 and S2 domains. The S1 domain contains the receptor-binding domain and is responsible for recognition and binding to the host cell receptor (Ace-2). The S2 domain, responsible for fusion, contains the putative fusion peptide (FP, yellow) and the heptad repeats HR1 and HR2. The transmembrane domain is represented in blue.

TMPRSS2: Transmembrane Protease from Host Cell

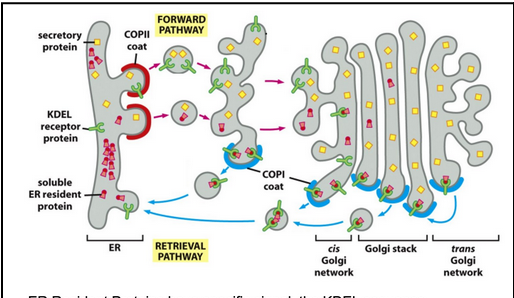

How do COPI vesicles and the KDEL signal ensure ER-resident proteins are retrieved from the Golgi back to the ER?

Vesicle entry of cargo is selective, guided by cargo receptors recognized by COPII components.

Some ER-resident proteins (e.g., BiP, Sec61) accidentally leave the ER due to random incorporation into COPII vesicles.

Cells use a retrieval pathway to return these proteins to the ER.

Membrane ER-resident proteins carry C-terminal KKXX-like motifs that bind directly to COPI coats for retrograde transport.

Soluble ER-resident proteins contain the KDEL sequence (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu).

These proteins bind the KDEL receptor, which captures them in the Golgi.

The KDEL receptor’s affinity for KDEL is pH-dependent:

High affinity in the acidic Golgi → binds KDEL proteins.

Low affinity in the neutral ER → releases them once returned.

COPI vesicles mediate the Golgi → ER transport step, recycling both receptors and escaped ER proteins.

The golgi apparatus allows for post-translational modifications

Glycosylation, phosphorylation, sulfation

Each golgi stack has two distinct faces: a cis face (entry) and a trans face (exit)

Each stack (called a cisterna) contains a characteristic set of processing enzymes

Complex oligosaccharides are added to proteins in the golgi apparatus

The golgi apparatus generates heterogenous oligosaccharide structures

The human genome encodes hundreds of different golgi glycosyl transferases

The resident proteins in the golgi apparatus (glycosidases and glcosyl transferases) are all membrane-bound. This way, the retrieval is facilitated via the COPI mechanism

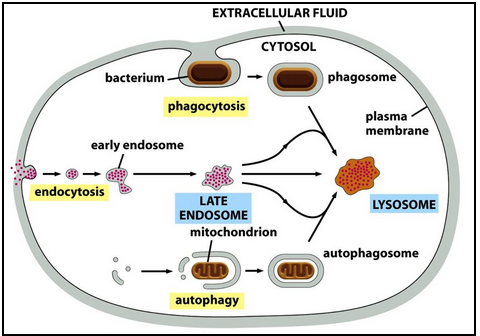

What are the three major roles of the lysosome, and what key steps define each pathway?

1. Intracellular Traffic

Digestive enzymes arrive from the Golgi.

Material from outside the cell enters via endocytosis → early endosome.

Early endosomes acidify to late endosomes (pH ~6) and mature into lysosomes.

Endosomal membrane proteins are recycled back to endosomes or the TGN.

2. Autophagy

Lysosomal degradation of cell’s own organelles/parts.

Example: liver mitochondria lifespan ~10 days.

Targeted material is enclosed by a double membrane → autophagosome.

Autophagosome fuses with lysosome (or late endosome).

Starvation increases autophagy—digested metabolites help maintain energy.

3. Phagocytosis

Used for large particles or microbes.

Macrophages/neutrophils engulf to form a phagosome.

Phagosome is converted into a lysosome through the same maturation/fusion steps as autophagy.

What are the key structural and functional features of lysosomes?

Site of intracellular digestion

– Break down internal and external macromolecules.Contain ~40 hydrolytic enzymes

– Proteases, nucleases, glycosidases, lipases, phosphatases, sulfatases.Digest macromolecules + microorganisms

– Produces amino acids, sugars, nucleotides, etc.Enzymes synthesized as inactive proenzymes

– Require acidic pH (4.5–5.0) for activation.Acidification

– Vacuolar H⁺-ATPase pumps protons into the lysosome using ATP.Proton gradient

– Drives export of metabolites from the lysosome.Lysosomal membrane is highly glycosylated

– Protects membrane proteins from proteases and lipases inside.

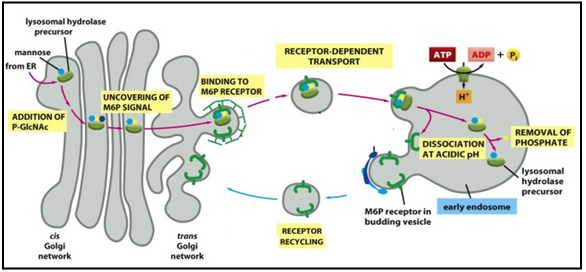

The M6P signal binds to the M6P-receptor in the golgi

Lysosome resident proteins

The M6P signal (mannose-6 phosphate)

The M6P-tagged hydrolase binds to the receptor in the Golgi

Release of hydrolase from the receptor occurs at low pH in the lysosome.

An acid phosphatase destroys M6P, so that hydrolase remains in the lysosome.

M6P receptors are retrieved into coated transport vesicles.

Lysosomal storage disease (I-cell disease)

Autosomal recessive disorder

Abnormal build-up of carbohydrates and fatty materials in cells (called inclusion bodies)

GlcNAc-phosphotransferase in the CGN is defective.

Therefore, Hydrolases are not tagged in the CGN.

Therefore, the hydrolases are not recognized by M6P receptors

Hydrolases are secreted at the cell surface rather than transported to the lysosomes.

Undigested substrates accumulate in lysosomes, resulting in the characteristic “I cells” or “inclusion cells”

Without the proper targeting signal (M6P), lysosomal proteins are secreted (the default pathway for proteins moving through the golgi apparatus)