Japanese Art History Midterm #1 Review

1/76

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

77 Terms

Conical pots, Early Jōmon, ca. 3000 BCE

For utilitarian use

Flame-style vessels, Middle Jōmon, ca. 1500 BCE

Middle Jomon sees more developments with scalloped lips, writhing coils forming spirals, S-shapes and meanders

Most vessels of the period are elaborate urns or jars and were probably used for making ritual offerings

Female dogū figurine—“insect-eyed type“ Late Jōmon, ca. 1000-500 BCE

Tomb of Emperor Nintoku, Kofun Period, 5th century

consists of a rounded, keyhole-shaped mound with trapezoidal elevations in front

Haniwa female figurine, Kofun period, ca. 500

Female dogū figurine, Late Jōmon, ca. 1000-500 BCE

Haniwa warrior, ca. 500, Kofun period

Ise Shrine, ca. 4th century, Early Shinto period, last rebuilt 2013, shinmei-zukuri architecture

Clean in lines, simple in proportions, organziation of space, built of pure and natural materials

Materials are left fresh and unpainted

Rebuilt every 20yrs to maintain a sense of freshness and newness

While using ancient techniques and tools for construction as a sense of permanence and renewal

Hōryū-ji Temple, Nara, 7th century—Originally built by Prince Shōtoku and rebuilt after the 670 fire

Kondo (Golden Hall/Main Hall), Hōryūji, Asuka period (7th century)

Details of the bracketing system of kondo (Golden Hall/Main Hall), Hōryūji, Asuka period (7th century)

Hokkiji Pagoda (685-706, Japan) Asuka Period

The pagoda is a five-storied tower (sanju no to) on a square ground plan of three-by-three bays

In its center, a mighty octagonal mast runs upwards through the entire structure

The “heart pillar” (shinbashira) stands for the world axis, rising from the tomb of the Buddha, which is represented by a cavity for relics in the central foundation stone

The central mast is almost freestanding

Three primary systems of components

Outer structure

Core post

Locking bracket and tie beam system

Five-level bracketing system

dougong 斗拱 = dou (bearing block) + gong (bracket arm)

ang 昂 (slanting cantilever arm)

dougong + ang = bracketing cluster (known as the “Chinese Order”)

Tori Busshi, Shaka Triad kondō, Hōryūji, Asuka Period, 623, in the tori style

the angular, severe, and archaistic sculptural style of Shiba Tori’s actual sculptures

The Tori style was the official style of the Suiko reign

These Tori works derive their regal stiffness from 6th century Koguryo bronze statuettes

The Tori hallmark: twin points rising at a prominent angle

Bronze, Buddha as central figure, Bodhisattva on both sides (historical Buddha)

Hierarchy of scale: bigger one is more important

Slanted, almond eyes

Dimple

narrow/elongated head shape

Lot’s of attention to detail on the surface: very japanese

Halo

Almond shape called mandola

Meditating Miroku, Hōryūji, Asuka period, 7th century

tender, dreamlike expression and gentle manner in which the hand is raised to the face

Archaic smile

Amida Triad, Lady Tachibana Shrine Gilt bronze, Nara Period, 8th century

They have the fuller proportions, characteristic chins, and sloping necks of the Yakushiji figures

The facial modeling is rather restrained, with angular lines along the brows, nose, and lips (which rise in twin points and bear the Tori cylindrical dimple beneath)

These pieces exude a full, quiet aristocratic confidence, and may be the work of a small group of conservative craftsmen who maintained Tori traditions in the face of imported Chinese styles and techniques

head shapes are more rounded which reflects the Tang style from China

dynamic decoration in the background, floral pattern, naturalistic, lot’s of variety, many figures (Buddha + other deities)

Archaic smile

Tamamushi Shrine with the Prince Sattva Jataka panel, Asuka period, 7th century

Jataka panel depicting the Prince Sattva’s sacrifice, Tamamushi Shrine, Asuka period, 7th century

Amida Triad, wall painting from Kondō (Golden Hall or Main Hall), Hōryūji. Nara period, ca. 710 (destroyed by fire in 1949)

Rounded face, no archaic smile just a resting face

Kannon: bodhisattva of compassion

Downcast eyes looking to the side

Slanted eyes, thick lips

Todaiji , first established by Emperor Shomu in 745, Nara period

most important imperial temple

Rebuilt two times, each time it was rebuilt, it became less chinese and more japanese in style

Supposed to house the biggest Buddha ever built

The monumental size shows the type of Buddhism that the Chinese and eventually the Japanese practiced

Tôshôdai-ji, kondô (golden hall), originally built by Ganjin in 759 in the Tang Chinese style architecture, under the auspice of Emperor Shomu, Nara, 8th century

The Kondo shows Chinese solidity, symmetry, and grandeur

more chinese in style, more grandeur, large/monumental proportions

Tôshôdai-ji, kodô (lecture hall), originally an imperial office building and relocated to Toshodaiji as a gift to Ganjin by Emperor Shomu, Nara period, 8th century

whose simplicity and horizontality, stressed by the slender pillars, are typical examples of Japanization

more japanese in style, more simple, more long and horizontal that reflects domestic use, human-sized proportions

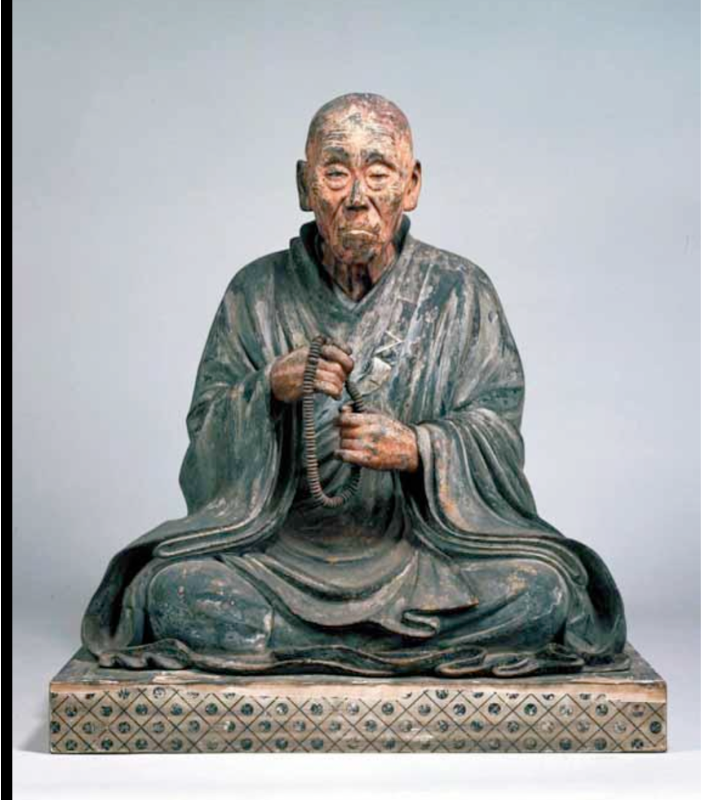

Master Ganjin, wood-cord dry-lacquer sculpture, Toshodai-ji, Nara, 758

The naturalistic depiction of such physical features as the blind eyes, the mouth resolute yet kind and aged but firm cheeks and chin, is matched by an extraordinary expression of emotion and spirituality

This combination of realism and expressiveness in sculpture was to become one of Japan’s major contributions to world art

Extraordinarily lifelike and shows the priest in an attitude of intense concentration

Emotionally moving realism

idealistic type of realism

Shōsōin, Tōdaiji, 756

Displays court life in the first half of the 8th century containing imperial clothing, prayer beads, ornaments, swords, musical instruments, textiles, mirrors, screens, writing tools, baskets, cabinets, flower vases, etc

Many of these objects are of native manufacture and their motifs and materials reflect the assimilation of diverse influences

Built after the death of Emporer Shomu for his wife’s donations of his treasures to the Todaiji temple

Simple structure and style

Raised platform, granary style, protection from moisture

Intentional that they used a native Japanese style instead of a Chinese style of architecture for imperial use -> necessity of a Japanese identity in the architecture

Azekura-zukuri (storehouse style)

Triangular-shaped beams/blocks

Special for an imperial storehouse

Detail of the azekura-zukuri (storehouse-style) technique

Bronze mirror with heidatsu decoration (gold and silver inlays in lacquer background)

Shosoin Textile with flower patterns from Tang China, 8th century

Glass cup and bowl, Shosoin collection, 8th century, Nara

koto (7-string zither) with heidatsu decoration (gold inlay in lacquer background)

Biwa (Chinese: pipa), Shosoin collection, 8th century, Nara

Genkan, Shosoin Collection, 8th century, Nara

Ladies under trees, 6 panels Ink and color on paper (originally with feathers) Before 756, Shosoin, Nara period

Ladies under trees, screen painting Ink and color on paper (originally with bird feathers) Before 756, Shosoin, Nara period

Likely made by Chinese immigrants

The cherry mouth, beauty mark (from central asia), figures look plump/have rounded faces, painted eyebrows that are bold (moth brow), patterned and transparent silk to display wealth

The Tang beauty standard for women

the Womb (phenomenal) World Mandala, early Heian, 9th century

The Womb World is represented by a series of concentric squares, the innermost of which contains an eight-petalled red lotus with a Buddha seated on each petal

Japanization: the faces of the deities exhibit a variety of expressions and gaze in different directions showing an interest in individual particularities that persists in subsequent Japanese art involving diverse groups present at any common situation

The Mandala of the Diamond (noumenal) world, early Heian, 9th century

Hachiman triad single-block wood (ichiboku) sculpture early Heian, 9th century

The three images in the Yasumigaoka Shrine perhaps therefore represent Emperor Ojin as the monk-garbed Hachiman, flanked by his mother, Empress Jingu, and a second female figure who is either Himegami or Ojin’s wife, Nakatsu

Shinto God Hachiman as a monk from the Hachiman Triad, early Heian, late 9th century, single-block wood technique

Hachiman is traditionally the god of war, and is considered to be the deification of Emperor Ojin (r. 270-313), the father of Emperor Nintoku (313-400) and a great unifier of the early Yamato state

In the Heian period, the Hachiman cult came to be closely associated with Shingon Buddhism, in which he was regarded as a bodhisattva and a protector of Buddhism, as well as a protector of the nation

In sculptures, Hachiman can also therefore be dressed as a monk

Shinto goddesses personifying Empress Jingū and Princess Nakatsu, Hachiman Triad, early Heian, 9th century, single-block wood technique

Phoenix Hall, Byōdōin, Uji, Kyoto, Inaugurated by Fujiwara Yorimichi in 1053, 11th century, Late Heian period

A light, elegantly designed structure that was apparently given its name in later times because it is shaped like a phoenix with wings extended in flight

Inside the hall is a sculptural representation of the raigo

built on a small island in the middle of an artificial lake

At the top of the roof is a chinese bronze phoenixes to give it status

The structure also resembles a bird in flight (w/ wings and a tail)

Heian shinden-zukuri (literally, residential mansion-style) architecture

Amida Buddha by Jōchō, joint-block wood (yosegi) sculpture, Phoenix Hall, late Heian, 1053

It is Jocho’s masterpiece, with proportions of the perfect human ideal: the rounded head, poised on a graceful neck, is balanced by gently sloping shoulders and softly articulated knees

The deity is approachable; the chapel envelopes one in a feeling of intimacy, of earthly aspiration raised to sublime and lyrical heights

Celestial bodhisattvas of the raigo sculpture program by Jōchō and his workshop, joint-block wood sculpture, Pheonix Hall, 1053, late Heian period, 11th century

attached to the upper parts of the walls, small gracefully shaped figures, adorned with halos and riding wisps of clouds

Celestial bodhisattvas of the raigo sculpture program by Jōchō and his workshop, joint-block wood sculpture, Phoenix Hall, 1053, Late Heian Period, 11th century

Attention to detail

Lost in their own music/dance: a sense of ecstasy b/c it’s a paradise

More approachable due to the relaxed facial expressions

Downcast eyes

Mono-no-aware

A delightful sadness

raigō wall painting on wooden panels (left), Phoenix Hall, 1053, late heian period, 11th century

Amida raigō triptych, Late Heian, late 11th century

It shows Amida gazing down at an unseen soul in the lower right of the painting

His hands are in the mudra of welcome

The mural depicts not only a host of celestial beings playing musical instruments and monks absorbed in prayer but also a new element emerging; that of Japan’s rural landscape

the serene, low-lying hillocks and meandering streams of Yamato

In Japan, more connected to the people with the Amida coming down to the people

In China, the bodhisattva would guide one to the Amida

Raigo painting with Yamato-e landscape setting, Phoenix Hall, 1053

“Early Spring” of Yamato-e landscape in the raigō painting, Phoenix Hall, 1053

“Yamato” refers to native Japan

“-e” refers to anything indigenous

Exemplifies mono-no-aware, the pathos of things

Rolling hills, blue and green for color

Not exactly decorative, but more so evocative, emotional

Characteristic of Heian art

Inspired by poetry of the time

Focus on nature and emotion evoked by nature

Tale of Genji Emaki (picture scrolls) as onna-e and the use of the “blown-off the roofs” (fukinuki-yatai) technique, late Heian, early 12th century

“A line for the eye, a hook for the nose” (hikime-kagihana) used to depict both man and woman in the Tale of Genj Emaki

Chapter 15 The Wormwood Path: Genji paying a visit to Lady Safflower, Tale of Genji Emaki, 12th century, late Heian period

Emotional

Simplicity

Large negative space important for the composition

Nothing is wasted, every detail is intentional and serves a purpose

Chapter 36 The Oak Tree (1): Third Princess Nyosan, retired emperor Suzaku, and Genji, Tale of Genji Emaki, 12th century, late Heian period

The intersecting diagonal lines of the composition represent the intense emotions of the characters

Each psychologically isolated from each other

The psychological isolation of the characters is symbolized by the silk room-dividers which are here placed to form cells of separate emotion

The tension is further heightened by the sharply tilted ground-plane

screens/curtains divide characters physically and emotionally

All characters look sad: heads lowers, no eye contact/not looking at each other

Heian period was an era of beauty

Importance of layers and taste

Pattern of the clothes display beauty

Chapter 36 The Oak Tree: 50th Day Celebration with Nyosan, Genji holding the baby, Tale of Genji Emaki, 12th century, late Heian period

He cradles the baby for all to see

The princess is depicted on the left by the hem of her robes under the curtain

Genji is seen holding the baby that is not his

Pretending he’s happy and holding is real son

Strong diagonals

Characters pushed way to the left

Characters not communicating with each other

Chapter 38 The Bell Cricket (1): Nyosan and Genji (half-hidden at the lower left corner), onna-e style, Tale of Genji Emaki, 12th century, late Heian period

Use of the tsukuri-e painting technique

Tsukuri-e: a technique with an underdrawing for color to be added later

Lot’s of diagonals,

Genji and Nyosan separated by a diagonal wall

Genji’s presence is indicated by the hem of his robe under the curtain

Chapter 38 The Bell Cricket (2): Genji meeting with (his son) Emperor Reizei, Tale of Genji Emaki, 12th century, late Heian period

The strong diagonal lines of architecture show that they can’t speak aloud their thoughts

The hikime kagihana technique allows the suggestion of extremely subtle emotional nuances

Ex: Reizei’s pupil is placed towards the center of his face, to indicate warmth and humility

Both characters are grouped to the left of the painting

Very private and intimate: they are facing each other

The painter changes the story by adding attendants with one playing the flute

The sound of the flute displays the high and tense emotions of the characters

Very cinematic, kinda like a montage

Chapter 40 The Rites, Genji’s final meeting with the dying Murasaki, early 12th century, late Heian period

The artist has dedicated half the space of the painting to the garden

Multiple lines of dew-drenched plants evokes feelings of farewell and the impermanence of human relationships

The decorated paper of the text has delicate motifs of butterflies and mist that show the delicate beauty of his wife as her health fails

This section of the painting with the figures is full of a sense of nostalgia and the melancholy awareness of the transitory nature of human existence

The calligrapher brushed on purpose in a hasty and emotion-filled manner where the words run together

Digital restoration of the original decorative paper and patterns, 12th century, late heian period

Beginning section of the text

Decorative paper for the calligraphy

Everything is highly skilled, with special attention to details

Emphasis on beauty in Heian period

Motifs

Butterfly represents both death and rebirth

Comparison of the beginning text (right) and the later text (left): How calligraphy is used to express different human emotions in the narrative scroll?

Compared to later text: the writing is more continous and blended together (looks more sloppy) at the end of the chapter whereas the beginning of the chapter’s characters are much more organized, and separated

Expression of the miyabi and mono no aware aesthetic ideals

Lady Kii (?), Ch. 44 Bamboo River (Takekawa), Tale of Genji Emaki, late Heian, 12th century (Akiyama, fig. 7)

argued that it’s by Lady Kii because the figures are too doll-like and stiff

Lady Kii(?), Ch. 45 Lady at the Bridge (Hashihime), from Tale of Genji, Heian, 12th century (Akiyama, pl. 3)

argued that it’s by Lady Kii because the figures are too stiff

Anonymous onna-de calligraphy of a waka poem from the Masu-shikishi set, ca. 1100, Late Heian period

The use of onna-de calligraphy of poems to express human emotions through the images of nature

The use of the warihagi technique to create space for the Buddhist inscription inside the hollowed-out sculpture, kamakura period, 13th century

Todaiji, first established in 745, rebuilt by the Buddhist monk Chogen in 1180s-90s

Pair of Niō (Gate Guardians) by Unkei and Kaikei, painted Joined-block sculpture, Great South Gate, installed in 1203, kamakura period

Very dynamic, lot’s of movement

Contrapposto pose: shifted weight to one leg

Very prominent musculature

Almost like a warrior

Realistic positions of hands and feet

Very warrior-like to drive off the demons

Samurai aesthetic

Unkei, Muchaku (renowned Indian monk Asanga) painted Joined-block sculpture with crystal inlaid eyes, kei school, 1212, kamakura period

Kei school

Inlaid crystal eyes -> characteristic of the Kei School

More realistic depiction of human eyes -> more believable -> more powerful

Happy middle between a sense of idealization and realism

A subtly peaceful and caring facial expression

Kaikei, Jizō Bosatsu (Bodhisattva of the Earth Matrix), 1202, Kei school, Joined-block sculpture with crystal inlaid eyes, kamakura period

The sensitive rendering of the bosatsu’s face gives the impression of youthfulness, with its full, vibrant cheeks, chin and neck

Adding to the impression of a living being are the inlaid crystal eyes

The sculpture has also imbued Jizo’s body with a sense of realism, the shoulders gently rounded and the belly seeming to swell slightly beneath the folds of the robe

The feet and toes are also carved to simulate the appearance of healthy, youthful flesh

Koen, Jizo Bosatsu, 1249, Buddhist sculpture serves as a reliquary through the warihagi technique to hide Buddhist images and texts (hibutsu), kamakura period

Typically hides gold images and texts inside the sculpture

Gives power to the sculpture itself

Usually put in by a priest or monk

Kôshun, Shintō Deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist Monk, kei school, 1328, muromachi period

Sesshū Spring, from a set of fourseason landscape hanging scrolls, c. 1470s, muromachi period

Sesshu mastered the Chinese style

Pagoda at top of the mountain

Running water coming down

Travelers going up the mountain

Temples scattered around the mountain

Clarity between foreground and background

Very detailed

Sesshū, Landscape of four season: Winter, 1470s, muromachi period

No clarity between foreground and background

Ambiguity of space

Heavy contour line in the middle

Faster and more ambiguous

Much less detailed

A move away from the chinese style

Sesshū, Landscape of Four Seasons: Autumn hanging scroll, Muromachi period, c. 1470s

Sesshū, Haboku (splashed ink) landscape, shigajiku hanging scroll, Muromachi, 1495

Asymmetry, Simplicity, Unadorned loftiness, Spontaneity, Spiritual depth, Unworldliness, Inner serenity

It is an abstract representation of trees on a small island or jut of land with great mountains just faintly visible in the background

It is an extremely abbreviated, impressionistic paintings of this sort that one perceives most directly the intense feeling for nature that motivated artists like Sesshu

Splashed ink style (haboku)

Very eccentric

Gives effect of not trying to depict anything

But can still see some things like a fishing boat, and mountain, and bamboo

Very sketchy, very ambiguous

Sesshū, Garden of Joei-ji, muromachi period, kare-sansui, 13th century

Ties to his paintings

Certain kinds of rocks in both the paintings and garden

Dry Landscape (Kare-sansui) Garden, Ryoan-ji, Kyoto, Muramachi, wabi-sabi aesthetic, ca. 1480s-1500

A representation of the ocean with islands protruding above its surface

Consisting solely of rocks and sand, so extremely severe in layout that it seems to be an ultimate visual depiction of the medieval aesthetics of the withered, cold, and lonely

15 rocks in five groups

Raking to create patterns

Island in the sea: circular raking around rocks

Daisenin Garden, kare-sansui technique, wabi sabi aesthetic, 1513

We see in the background several large rocks representing towering mountains

In the middle there is a flat, bridgelike rockand flowing beneath it is a “river” of white sand

Josetsu, Catching a Catfish with a Gourd, shigajiku (painting with poetic inscriptions by Zen monks), commissioned by Ashikaga shōgun Yoshimochi (1380-1428) in 1413

The theme of the painting was the Zen riddle on catching the slippery catfish with the smooth-skinned gourd

The work is largely in monochrome, with a touch of red to accent the gourd

Faint echoes of the Liang Kai manner can be seen in the angular lines and hooks of the drapery

The gentle curves of bank, bamboo, catfish, gourd, and flowing water are offset by the bristling intensity of the reeds on the rights, and by the extraordinary absorption of the aspirant

An impossible task, irrational

Kind of similar to koan, very Zen

Priest Chōgen, by a Kei School master? joined/multi-block technique, early 13th century, Kamakura period