Cognitive Approach

1/16

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Topics & Studies

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

17 Terms

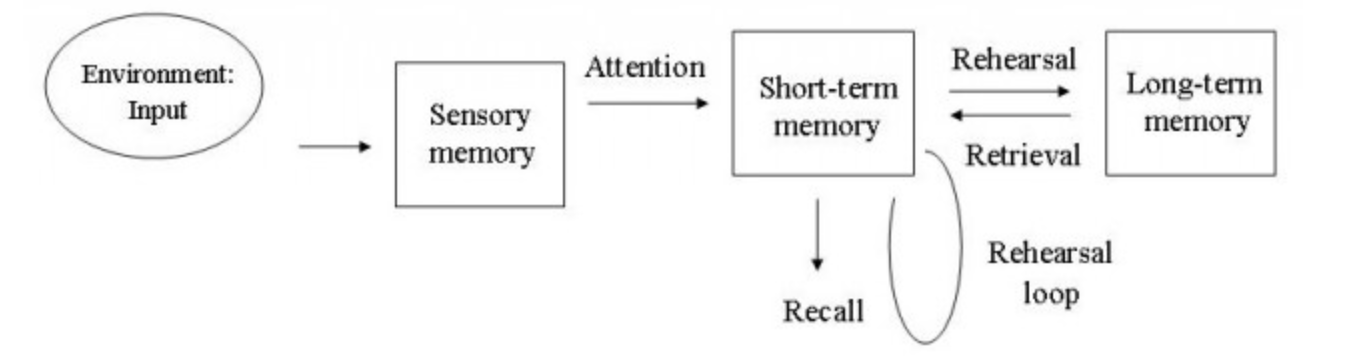

Multi-store Model (Atkinson and Shiffrin, 1968)

model which assumes there are three unitary (separate) memory stores, and that information is transferred between these stores in a linear sequence

Sensory memory - constantly receiving information but most of this receives no attention and remains in the sensory register for a very brief period

Short-term memory (STM) - duration of up to 30 seconds, has a capacity of 7+/-2 chunks and mainly encodes information acoustically. Information is lost through displacement or decay

Long-term memory (LTM) - unlimited capacity and duration and encodes information semantically. Information can be recalled from LTM back into the STM when it is needed

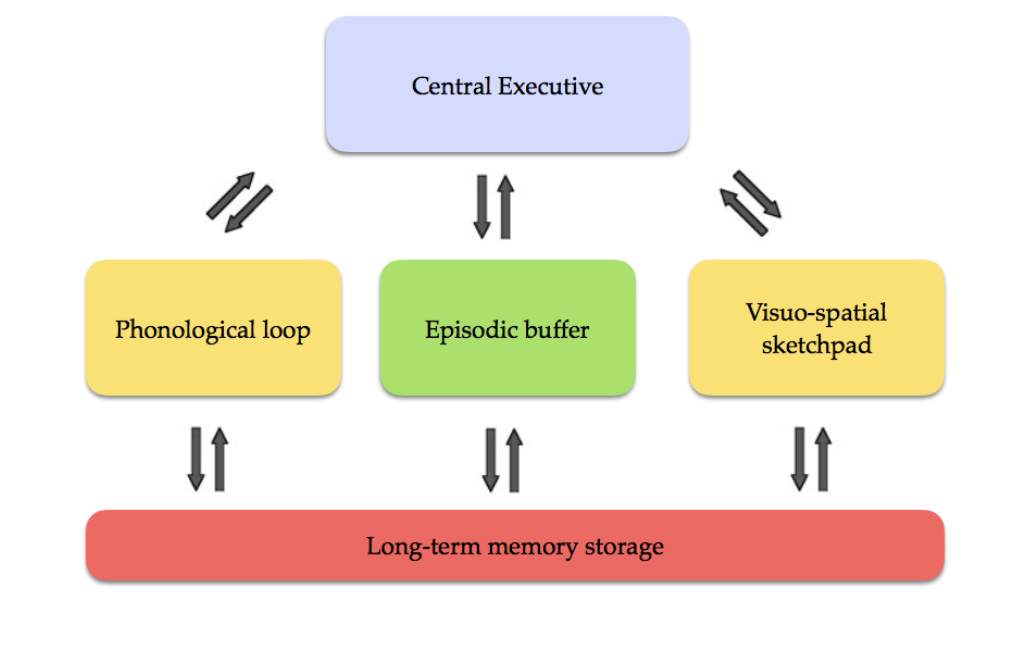

Working Memory Model (Baddely & Hitch, 1974)

expands on the multi-store memory model by replacing STM with working memory; divided into 4 parts

Central Executive: Directs attention

Episodic Buffer: Stores visual stimuli

Phonological Loop:

Articulatory control system (inner voice, rehearsing sounds)

Phonological store (inner ear, holding speech sounds)

Visuospatial Sketch Pad: inner eye

Schema Theory

the framework of preconceived ideas our brains use to organize the world; used to process new information, given already know information

Thinking & Decision Making

a mental process that involves knowing, understanding, remembering, and communicating.

Dual Processing Model

Theorizes that the process of thinking has 2 parts:

System 1: intuitive, uses heuristics, relying on schemas and past experiences (AUTOMATIC)

System 2: rations, meaning it uses algorithms and requires concentration and effort (CONTROLLED)

Reconstructive Memory

a process in which memories are influenced by the context and subsequent information, often leading to distortions or inaccuracies

Anchoring Effect

the cognitive bias that relies heavily on the first piece of information encountered when making decisions

Flashbulb Memory

a highly detailed and vivid recollection of a significant event, often retained for a long time

Miller (1956)

MULTI-STORE MODEL

Aim: to investigate the capacity of short term memory

Method: experiment

Procedure: Participants were tested with lists of words to determine how many they can remember. Once shown the list they were asked to recall as many as possible right after the learning phase.

Results: Short-term memory capacity is limited to about seven (plus or minus two or 7 +/- 2) chunks of information

Conclusion: This showed that our short term memory is limited in capacity

Landry and Bartling (2011)

WORKING MEMORY MODEL

Aim: to investigate if articulatory suppression would influence recall of a written list of phonologically dissimilar letters in serial recall.

Method: true experiment; independent groups design

Procedure: In one group participants had to recite the numbers "1" and "2" while trying to memorize a list of 7 letters. The control group saw the letters but did not carry out the articulatory suppression task.

Results: The results showed that the control group recalled an average of 76% of the list accurately and the articulatory suppression condition only 45%.

Conclusion: In line with the WMM, articulatory suppression is preventing rehearsal in the Phonological Loop because of overload. The data supports the prediction of the WMM that disruption of the Phonological Loop results in less accurate working memory as it has a limited capacity.

Bartlett (1932)

SCHEMA THEORY

Aim: to investigate how the memory of a story is affected by previous knowledge.

Method: quasi experiment

Procedure: Bartlett told participants a Native American legend called The War of the Ghosts. The participants in the study were British; for them, the story was filled with unknown names and concepts, and the manner in which the story was developed was also foreign to them. The story was therefore ideal to study how memory was reconstructed based on schema processing.

Bartlett allocated the participants to one of two conditions:

First Group: use repeated reproduction, where participants heard the story and were told to reproduce it after a short time and then to do so again repeatedly over a period of days, weeks, months or years.

Second Group was told to use serial reproduction, in which they had to recall the story and repeat it to another person.

Results: Bartlett found that participants in both conditions changed the story as they tried to remember it (distortion). Three patterns of distortion:

Assimilation: The story became more consistent with the participants' own cultural expectations - that is, details were unconsciously changed to fit the norms of British culture.

Levelling: The story also became shorter with each retelling as participants omitted information which was seen as not important.

Sharpening: Participants also tended to change the order of the story in order to make sense of it using terms more familiar to the culture of the participants.

Conclusion: Indicates that remembering is not a passive but rather an active process, where information is retrieved and changed to fit into existing schemas.

Loftus & Palmer (1974)

SCHEMA THEORY

Aim: to test their hypothesis that the language used in eyewitness testimony can alter memory.

Method: independent measures experiment

Procedure: Forty-five American students from the University of Washington formed an opportunity sample.

Had five conditions, only one of which was experienced by each participant

Seven films of traffic accidents, ranging in duration from 5 to 30 seconds, were presented to each group in random order.

After watching the film, participants were asked to describe what had happened as if they were eyewitnesses.

They were then asked specific questions, including the question “About how fast were the cars going when they (smashed / collided / bumped / hit / contacted) each other?”

Thus, the IV was the verb of the question, and the DV was the speed reported by the participants.

Results: The estimated speed was affected by the verb used. The verb implied information about the speed, which systematically affected the participants’ memory of the accident. Participants who were asked the “smashed” question thought the cars were going faster than those who were asked the “hit” question.

Conclusion: The results show that the verb conveyed an impression of the speed the car was traveling and this altered the participants” perceptions.

Atler & Oppenheimer (2007)

THINKING/DECISION MAKING

Aim: to investigate how font affects thinking

Method:

Procedure: 40 Princeton students completed the Cognitive Reflections Test (CRT). This test is made up of 3 questions, and measures whether people use fast thinking to answer the question (and get it wrong) or use slow thinking (and get it right). Half the students were given the CRT in an easy-to-read font, while the other half were given the CRT in a difficult-to-read font

Results: Among students given the CRT in easy font, only 10% of participants answered all three questions correctly, while among the students given the CRT in difficult font, 65% of participants were fully correct

Conclusion:

When a question is written in a difficult-to-read font, this causes participants to slow down, and engage in more deliberate, effortful System 2 thinking, resulting in answering the question correctly

On the other hand, when the question is written in an easy-to-read font, participants use quick, unconscious and automatic System 1 thinking to come up with the obvious (but incorrect) answer

Wason (1968)

THINKING/DECISION MAKING

Aim: to investigate the heuristic of confirmation bias and the errors people make in logical tasks based on heuristics.

Method: lab experiment

Procedure: Participants were asked to complete a test of logical reasoning now called the Wason Selection Task. In this task they are shown cards, such as the ones below, and asked the following question: "Which card(s) must be turned over to test the idea that if a card shows an even number on one face, then its opposite face is red?". The cards shown were 3, 8, red, and brown.

Results: Most participants give the incorrect answer, which is to turn over the cards with number 8 and the red card. Less than 10% of participants give the correct answer, which is to turn over the number 8 card and brown card.

Conclusion: Wason argues that participants made the incorrect choice based on heuristics, such as matching bias (in an abstract problem, we tend to be overly influenced by the wording (or context) of the question; in this case, the words "even number" and "red"). This task required System 2 thinking

Brewer & Treyens (1981)

SCHEMA THEORY & RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORY

Aim: to investigate whether people's memory of objects in a room is influenced by their of schema of what should be in an office

Method: lab experiment

Procedure: Participants were told to wait in a room for the experimenter. They were told this was the experimenters office. They did not realise the study had already began. After 35-60 seconds the participant was taken to a nearby room and allocated one of 3 conditions:

Recall: participants were asked to write down as many objects as they could remember from the office. They were then given a booklet containing a list of 131 objects which they had to rate how sure they were that the object was in the room. (70 of them were not in the room)

Drawing: participants were given an outline of the room and asked to draw the object they could remember

Verbal Recognition: participants were read a list of objects and asked whether they though the object was in the room or not.

Results: In the writing and drawing condition participants were more likely to remember items that were congruent with their schema of an office. For example, in the written recall condition 29 participants remembered there was a desk and chair but only 8 remembered there was a skull. Reconstruction errors also occurred where 9 participants remembered there were books when there were no books.

Conclusion: Brewer and Treyens demonstrate how schemas influence memory recall. For example, more participants remembered objects congruent with what their schema expected them to find in an office (e.g desk and chair) than objects that are not usually found in an office (e.g skull).

Brown & Kulik (1977)

FLASHBULB MEMORY

Aim: to investigate the validity of flashbulb memory compared to recall of other events, and the effect of racial identity on it

Method: questionnaire and interview

Procedure: 80 participants interviewed in the study (40 African Americans, 40 Caucasians). Participants were asked to recall circumstances where they had learned of shocking events. They were asked to recall memory on 10 events. 9/10 were assassinations or attempted assassinations of American public figures (JFK). They were also asked how much they rehearsed the events (overtly or covertly)

Overtly: rehearsal through discussion with other people

Covertly: private rehearsal or ruminating

Results: Participants remembered where they were, what they were doing and how they felt when learning about shocking public events

Researchers found that the 1963 JFK assassination led to the most flashbulb memories (90% of people remembered this in context with vivid detail)

African Americans also recalled more FM of civil rights leaders (MLK) more than Caucasian participants

For the self-selected events, most participants had FM of deaths of family (ex. parents)

Conclusion: Researchers concluded that results of the study supported the theory of flashbulb memory. Brown and Kulik (1977) indicated that flashbulb memory is more likely for spontaneous and personal events, and suggested the "photographic model of flashbulb memory". They also suggested that FM is caused by physiological emotional arousal (ex. activity in the amygdala).

Sharot et al (2007)

FLASHBULB MEMORY

Aim: to determine the role of biological factors on flashbulb memories

Method: case study

Procedure: The study was conducted three years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in Manhattan. Participants were put in an fMRI machine and whilst in the scanner they were presented with word cues on the screen alongside the words:

summer

September

to get the participant to link the words to either the summer holidays or the 9/11 attack. Participants brains were scanned and recorded while they were recalling events. The memories of personal events from the summer were used as a baseline of brain activity for evaluating the nature of the 9/11 attacks. Afterwards, participants were asked to rate their memories for vividness, detail, confidence in accuracy and arousal. They were also asked to write down their personal memories.

Results: The activation of the amygdala for the participants who were downtown was higher when they recalled memories of the terrorist attack than when they recalled events from the preceding summer, whereas those participants who were further away from the event had equal levels of response in the amygdala when recalling both events.

Conclusion: The strength of amygdala activation at retrieval was shown to correlate with flashbulb memories. These results suggest that close personal experience may be critical in engaging the neural mechanisms that produce the vivid memories characteristic of flashbulb memory.