PSCL 357 Cognitive Psyc

1/80

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

81 Terms

Cognition

The collection of mental processes and activities used in perceiving, remembering, thinking, and understanding – pattern recognition, attention, memory, knowledge, language, comprehension, reasoning, problem-solving

Criticisms of cognitive psychology

1. Reductionism

Definition (from slide):

Cognitive psychology attempts to explain complex mental processes by reducing them to overly simple components.

Clarification:

Breaking thinking into tiny parts can ignore how the whole mind actually works together. Lab tasks may not reflect how thinking works in everyday life.

Memory hook:

Too much breaking down, not enough seeing the whole.

2. Ecological Validity

Definition:

The extent to which findings from laboratory tasks generalize to real-world situations.

Why it’s a criticism:

Many cognitive psychology studies use artificial lab tasks, so results may not generalize well to everyday behavior.

One-line MCQ memory trick

Cognitive psychology is criticized for breaking things down too much (reductionism) and not always reflecting real life (low ecological validity).

Where did Cognitive Psychology Come From? (Philosophical Sources)

Context (why this slide matters):

Cognitive psychology did not appear suddenly. It grew out of philosophical debates about where knowledge comes from and how the mind works. These ideas shaped how psychologists think about learning, reasoning, and mental representation.

Nativism

Definition:

The idea that some knowledge and mental structures are innate (inborn) rather than learned from experience.

Empiricism

Definition:

The view that knowledge comes primarily from sensory experience and learning. Concept of “tabula rasa” (a blank slate) of the human mind at

birth upon which experience writes

Rationalism

Definition:

The belief that reasoning and mental processes are the main sources of knowledge.

Associationism

Definition:

The idea that complex thoughts are formed by associations between simpler ideas.

MCQ Memory Anchor

Cognitive psychology came from debates about innate knowledge (nativism) vs. learned knowledge (empiricism), with an emphasis on mental processes (rationalism) and associations between ideas.

Where Did Cognitive Psychology Come From? (Psychological Sources)

Context (why this slide matters):

Cognitive psychology developed in response to earlier psychological approaches. Each one influenced cognitive psychology, either by contributing ideas or by showing what was missing.

Structuralism (Wundt, Titchener)

Definition:

An early approach that tried to understand the mind by breaking conscious experience into basic components (sensations, feelings) using introspection.

Example:

A person describing exactly how a sound or color feels in their mind.

Why it matters:

It showed early interest in mental processes, but introspection was too subjective, so cognitive psychology adopted more objective methods.

Functionalism (James)

Definition:

An approach that focused on what mental processes do and how they help individuals adapt to their environment.

Example:

Studying memory in terms of how it helps us learn and survive, not just what it is made of.

Why it matters:

Cognitive psychology shares this goal of understanding how thinking helps us function.

Behaviorism (first Watson, then Skinner)

Definition:

An approach that defined psychology as the study of observable behavior only, rejecting the study of mental processes.

Example:

Studying learning by measuring rewards and punishments, not thoughts or intentions.

Why it matters:

Cognitive psychology emerged as a reaction against behaviorism, arguing that mental processes must be studied.

MCQ Memory Anchor

Structuralism = what is the mind made of

Functionalism = what does the mind do

Behaviorism = ignore the mind → cognitive psychology studies mental processes

Logic Theorist

Definition:

An early artificial intelligence program that could solve logical and mathematical problems.

Key idea:

It showed that human problem-solving could be modeled as a series of mental steps.

Example:

Proving mathematical theorems using rules, similar to human reasoning.

Channel Capacity

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Channel capacity, the concept that any system processing information has a limited capacity”

“Miller: Magical Number 7 +/- 2”

Explanation (mine):

Miller’s “Magical Number 7 ± 2” means: when people have to hold information briefly in mind (like repeating digits, letters, or simple chunks), most can keep about 5–9 items at once. That range (7 plus or minus 2) is evidence that your information-processing system has a capacity limit—once you go beyond it, accuracy drops or you need strategies (like chunking) to fit more into the same limited space.

Measuring Information Processes

Context (why this slide matters):

Cognitive psychology needs ways to measure mental processes that can’t be seen directly. These methods use accuracy and response time to infer what’s happening in the mind.

Donders’ Subtraction Method

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Time needed for simple mental processes can be determined by subtracting the time needed for a task from the time needed for a more complex version of the task.”

Examples from the slide:

Simple reaction task: press a button when a light appears.

Choice reaction task: press one button if the light is red and another if it is green.

Explanation (mine):

The extra time in the choice task represents the time required for the additional mental decision. This was the first method used to measure how long thinking takes.

Signal Detection Theory

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“An approach to measuring accuracy which emphasizes that it must be separated from response bias”

Examples / parts from the slide:

Hit – signal present, person says “yes”

Miss – signal present, person says “no”

False Alarm – signal absent, person says “yes”

Correct Rejection – signal absent, person says “no”

d′ (d-prime) – sensitivity

β (beta) – response bias / criterion

Explanation (mine):

This theory shows that performance depends on both the ability to detect the signal (sensitivity) and the person’s tendency to say “yes” or “no” (bias).

Diffusion Model

Definition:

A model that explains decision-making as a process where evidence accumulates over time until a decision threshold is reached.

Key idea:

Decisions are not instantaneous — information builds up gradually.

Example:

Choosing whether a word is real or not as evidence slowly pushes you toward a “yes” or “no” response.

MCQ Memory Anchor

Donders → subtract to find mental stages

Signal Detection → sensitivity vs bias

Diffusion Model → evidence builds up over time

Lexical Processing & Word Recognition

Context (why this slide matters):

These terms explain how we recognize words and what factors make word recognition faster or slower. They’re commonly tested with reaction-time MCQs.

Lexical Decision Task

Definition:

A task where participants decide as quickly as possible whether a string of letters is a real word or not.

Key idea:

Reaction time reveals how words are represented and accessed in memory.

Example:

Deciding that “table” is a word but “blate” is not.

Word Frequency Effect

Definition:

Words that are used more frequently are recognized faster than rare words.

Key idea:

Common words have stronger mental representations.

Example:

“House” is recognized faster than “bungalow.”

Orthographic Neighborhood Size

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Words with many neighbors are recognized faster”

Explanation of the slide example (mine)

An orthographic neighbor is a word that looks very similar to another word (changes by one letter).

For example:

cat → neighbors: cap, can, cut, cot

When a word has many neighbors, the brain already has similar letter patterns activated, which makes recognition faster.

This shows that word recognition depends on how similar a word is to other words you already know.

Donders’ Subtraction Method

Definition:

A method for estimating the time required for individual mental processes by subtracting response times of simpler tasks from more complex ones.

Key idea:

Complex thinking is made up of separate stages.

Example:

If Task A takes 200 ms and Task B takes 300 ms, the extra 100 ms is attributed to an added mental step.

Signal Detection Theory

Definition:

A framework for measuring decision-making that separates sensitivity from response bias.

Key idea:

Performance depends not just on ability, but also on a person’s willingness to say “yes” or “no.”

Example:

In a memory test, someone may say “yes” often (many hits but also many false alarms).

Diffusion Model

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“A model that describes how decisions are made by accumulating evidence over time until a boundary is reached”

Examples / parts from the slide

Evidence accumulates gradually (random walk)

Two decision boundaries

When the evidence hits a boundary → a response is made

Explanation of the slide examples (mine)

Imagine you’re trying to decide whether a blurry picture is a cat or a dog.

Your brain does not instantly know.

Instead:

Evidence slowly builds in your mind:

“I see whiskers…” (leans cat)

“I see pointy ears…” (leans cat)

“I see fur…” (could be either)

This back-and-forth is the random walk.

At the same time, there are two mental “decision lines”:

One boundary = CAT

One boundary = DOG

As evidence builds, it drifts toward one of those boundaries.

The moment it hits one, you make the decision.

What this explains

If the picture is clear → evidence hits a boundary quickly → fast decision

If the picture is unclear → takes longer → slower reaction time

If the evidence is weak → you might hit the wrong boundary → mistakes

So this model explains both:

reaction time

accuracy

with one process.

Lexical Decision Task

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“A task in which participants decide as quickly as possible whether a string of letters is a word or not”

Explanation of the slide examples (mine)

In this task, people see letter strings like:

TABLE → real word → fast response

TIBLE → not a word → slower response

The slide explains that several things affect how quickly people can make this decision:

Word frequency: words you see often (like house) are recognized faster than rare words.

Orthographic neighborhood size: words that look like many other words (like cat, cap, can) are recognized faster because similar patterns are already activated.

Age of acquisition: words learned early in life are recognized faster than words learned later.

Familiarity: familiar words are processed faster than unfamiliar ones.

Pseudowords / pseudohomophones: fake words that look or sound real take longer to reject because they partially activate real word patterns.

This task is used to understand how the brain recognizes words and how different factors influence that process.

Word Frequency Effect

Definition:

Words that are used more frequently are recognized faster than rare words.

Key idea:

Common words have stronger mental representations.

Example:

“House” is recognized faster than “bungalow.”

Orthographic Neighborhood Size

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Words with many neighbors are recognized faster”

Explanation of the slide example (mine)

An orthographic neighbor is a word that looks very similar to another word (changes by one letter).

For example:

cat → neighbors: cap, can, cut, cot

When a word has many neighbors, the brain already has similar letter patterns activated, which makes recognition faster.

This shows that word recognition depends on how similar a word is to other words you already know.

Global vs. Local Processing

The tendency to process either the overall shape (global) or the small details (local) of a stimulus first.

Global precedence: Big picture first

Local precedence: Details first

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Global features of a stimulus are processed before local features”

Explanation (mine):

When you look at something, you first see the overall shape (the big picture) before noticing the small details.

Example from the slide:

A large H made up of many small X’s.

People report seeing the big H before noticing the small X’s.

MCQ Memory Anchor

Global = whole first

Local = details first

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Definition (from slide):

The science of getting computers to do tasks that would require intelligence if done by humans.

Explanation (from slide context):

AI emerged as an early way to model human cognition by treating the mind as a digital computer.

MCQ Memory Anchor

AI = machines doing intelligent tasks

Turing Test = indistinguishable human vs computer responses

LOGIC THEORIST = first AI program; theorem proving

Turing Test

Person: Alan Turing

Definition (from slide):

A proposed test to determine whether computers can think: can an observer distinguish between the responses of a human and a computer?

Explanation:

If the observer cannot reliably tell them apart, the computer is said to pass the test.

MCQ Memory Anchor

AI = machines doing intelligent tasks

Turing Test = indistinguishable human vs computer responses

LOGIC THEORIST = first AI program; theorem proving

LOGIC THEORIST

People: Allen Newell & Herbert Simon

Definition (from slide):

Often considered the first true AI program, capable of generating proofs of mathematical theorems.

Explanation:

It supported the idea that human problem-solving could be modeled computationally.

MCQ Memory Anchor

AI = machines doing intelligent tasks

Turing Test = indistinguishable human vs computer responses

LOGIC THEORIST = first AI program; theorem proving

Problems for the Computer Metaphor of Mind - Searle’s Chinese Room

Person: John Searle

Definition (from slide):

A thought experiment arguing that even if a system passes the Turing Test, it may still not truly think if it lacks intentionality (understanding or meaning).

What Searle thought (core claim):

Following rules to produce correct outputs (syntax) is not the same as understanding meaning (semantics).

Example (from the slide’s description):

A person in a room uses a rule book to respond correctly to Chinese symbols without understanding Chinese.

Why it matters:

Challenges the idea that human thought = computation alone, raising doubts about the computer metaphor of mind.

MCQ Memory Anchor

Chinese Room = syntax ≠ understanding

Pass Turing Test ≠ genuine thinking

Dissociation

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“When one cognitive function is impaired while another remains intact”

Explanation of the slide example (mine)

If a brain injury causes someone to lose one ability (like recognizing faces) but leaves another ability untouched (like recognizing objects), this suggests the two functions rely on different brain systems.

This is evidence that different mental processes are handled separately in the brain.

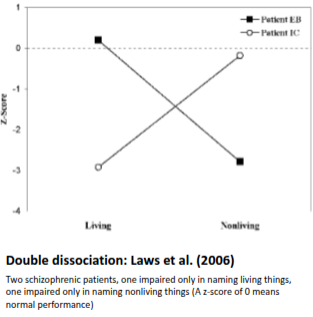

Double dissociation

Definition (formal):

When two patients show opposite patterns of impairment.

What this actually means (step by step):

You need TWO patients and TWO tasks.

Patient 1:

Impaired on Task A

Normal on Task B

Patient 2:

Impaired on Task B

Normal on Task A

➡ This is powerful because:

It shows the two tasks rely on different brain systems, not just different difficulty levels.

The graph slide (this is where it clicks)What the graph is showing:

Y-axis: performance (z-score)

0 = normal performance

Bars below 0 = impairment

The example on the slide (Laws et al., 2006):

Two schizophrenic patients were tested on:

Naming living things

Naming nonliving things

Patient A

Poor at living things

Normal at nonliving things

Patient B

Poor at nonliving things

Normal at living things

➡ When you see crossing bars (one low here, the other low there), that’s a double dissociation.

Why the graph matters:

The graph visually proves:

It’s not just “one task is harder”

Each task can be selectively damaged

Why it matters:

Provides strong evidence that two cognitive functions rely on different neural systems.

Why professors LOVE double dissociation (exam logic)

A double dissociation lets researchers say:

“These two cognitive functions are independent, not just different versions of the same process.”

If Patient A can do task 1 but not task 2, and Patient B can do task 2 but not task 1, this is strong evidence the tasks use different brain areas.

MCQ Memory Anchor (use this)

Dissociation = one ability impaired, another spared

Double dissociation = two patients, opposite impairments

Graph = crossing impairment patterns = separate systems

Neocortex

Definition:

The outermost layer of the brain responsible for higher-level cognitive functions.

Explanation:

This is where complex thinking happens — reasoning, planning, perception, language, and decision-making.

Example:

Reading a sentence, understanding its meaning, and deciding how to respond all rely on the neocortex.

Background:

Cognitive psychology focuses heavily on the neocortex because it supports conscious, complex mental processes.

Memory hook:

Neo = new → newest brain layer → higher thinking

Corpus Callosum

Definition:

A thick band of nerve fibers that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

Explanation:

It allows the two hemispheres to share information and work together.

Example:

Seeing an object with one side of the visual field and naming it requires communication across hemispheres.

Background:

Research on split-brain patients (where the corpus callosum was cut) showed how specialized each hemisphere can be.

Memory hook:

Callosum = call across → connects sides

Cerebral Lateralization

Definition:

The idea that different cognitive functions rely more on one hemisphere than the other.

Explanation:

Both hemispheres are involved in most tasks, but one side may be more specialized.

Example:

Language is often more left-hemisphere dominant, while spatial processing is often more right-hemisphere dominant.

Background:

Lateralization became clear through split-brain and brain-damage studies.

Memory hook:

Lateral = side → functions favor one side

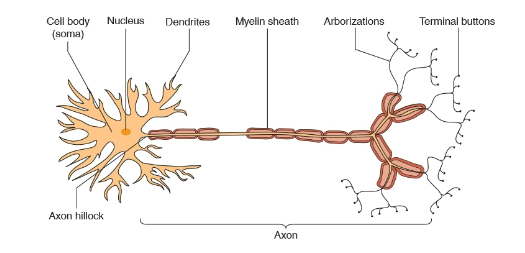

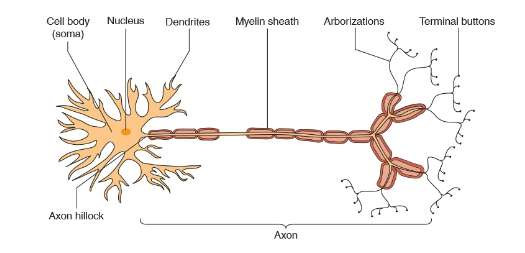

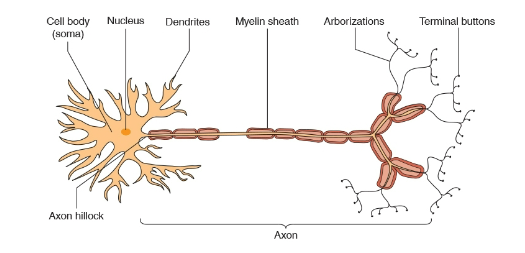

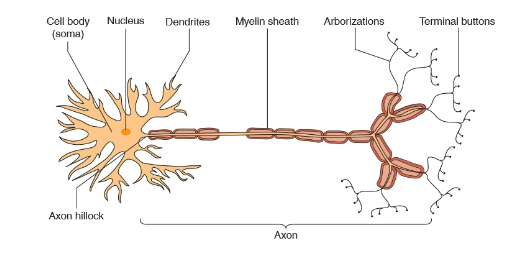

Neuron

Definition:

A specialized cell that transmits information in the nervous system using electrical and chemical signals.

Explanation:

Neurons are the basic units of the brain. All cognitive processes (thinking, memory, perception) ultimately depend on how neurons communicate.

Example:

When you recognize a word, neurons in visual and language areas fire in coordinated patterns.

Background:

The “mind as brain” metaphor assumes that mental processes can be understood by studying how neurons work.

Memory hook:

Neuron = brain’s information messenger

Dendrites

Definition:

The input structures of a neuron; many small branches that gather impulses into the neuron.

Explanation:

Dendrites receive signals from other neurons and bring that information toward the cell body.

Example:

A neuron may receive thousands of incoming signals on its dendrites before it fires.

Memory hook:

Dendrites = data in

Soma (Cell Body)

Definition:

The part of the neuron where biological activity is regulated and where incoming impulses from dendrites are integrated.

Explanation:

The soma acts like a decision center — it adds up all the incoming signals and determines whether the neuron should fire.

Example:

If enough excitatory signals arrive at the soma, it triggers an action potential.

Memory hook:

Soma = sum of inputs

Axon

Definition:

The output structure of a neuron; branchlike fibers that send signals to the next neuron.

Explanation:

Once the neuron fires, the electrical signal travels down the axon to communicate with other neurons.

Example:

A motor neuron sends a signal down its axon to cause a muscle to move.

Memory hook:

Axon = action out

Action Potential

Definition:

A brief change in the electrical charge of a neuron that travels down the axon and is followed by a refractory period.

Explanation:

After a neuron fires, it enters a refractory period where it cannot fire again immediately. This controls the timing of neural signals.

Example:

A neuron firing repeatedly in response to a stimulus must pause briefly between firings because of the refractory period.

Memory hook:

Action potential → fire → pause (refractory)

All-or-None Principle

Definition:

All action potentials are the same size; a neuron either fires completely or does not fire at all.

Explanation:

The strength of a stimulus does not change how big the action potential is — it only changes how often the neuron fires.

Example:

A brighter light doesn’t create a “bigger” signal, it causes neurons to fire more frequently.

Memory hook:

All-or-none = on or off, never half

Synapse

Definition:

The gap between neurons where neurotransmitters are released from one neuron to influence another.

Explanation:

When the action potential reaches the end of the axon, the signal changes from electrical to chemical so it can cross the synapse.

Example:

One neuron releases neurotransmitters into the synapse that either excite or inhibit the next neuron.

Memory hook:

Synapse = signal crossing the gap

Neocortex

Definition:

The outermost layer of the brain responsible for higher mental processes like thinking, reasoning, perception, and language.

Explanation:

This is where most conscious cognitive processing happens.

Example:

Understanding a sentence or solving a problem relies on the neocortex.

Memory hook:

Neo = new → newest, smartest brain layer

Corpus Callosum

Definition:

A thick band of nerve fibers that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

Explanation:

It allows both sides of the brain to communicate and share information.

Example:

Information seen in one visual field can be named because the hemispheres share it through the corpus callosum.

Memory hook:

Callosum = call across

Cerebral Lateralization

Definition:

The idea that some cognitive functions rely more heavily on one hemisphere than the other.

Explanation:

The brain is specialized — certain tasks are more dominant on one side.

Example:

Language is often more left-hemisphere dominant; spatial skills more right-hemisphere dominant.

Memory hook:

Lateral = side

Contralaterality

Definition:

The organization of the brain such that each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body.

Explanation:

Left brain → right body

Right brain → left body

Example:

Damage to the left motor cortex affects movement on the right side.

Memory hook:

Contra = opposite

Hippocampus

Definition:

A brain structure critical for forming new conscious long-term memories.

Explanation:

It helps turn experiences into memories you can later recall.

Example:

Patient H.M. could not form new memories after hippocampal damage.

Memory hook:

Hippocampus = memory maker

Amygdala

Definition:

A brain structure involved in emotional processing, especially fear and emotional learning.

Explanation:

It attaches emotional meaning to experiences.

Example:

Learning to fear something after a bad experience depends on the amygdala.

Memory hook:

Amygdala = emotional alarm

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Applying repeated magnetic stimulation at the surface of the skull to temporarily disable a brain region”

Explanation (mine):

This allows researchers to briefly interrupt activity in a specific brain area and observe how behavior changes, helping determine what that region is responsible for.

Event-Related Potential (ERP)

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Momentary changes in electrical activity in the brain when a particular stimulus is presented, measured by EEG. This allows great temporal precision.”

Explanation (mine)

To understand ERP, you must know EEG.

EEG (electroencephalography) is a method where electrodes are placed on the scalp to record the brain’s overall electrical activity.

An ERP is not the whole EEG signal.

It is a tiny change in that electrical activity that happens right after a specific event (like seeing a word, hearing a sound, or reading a sentence).

Researchers:

Present the same stimulus many times

Average the EEG signals

The consistent change that appears at the same time after the stimulus is the ERP

This is why ERP has great temporal precision — it shows exactly when the brain reacts to something, often within milliseconds.

fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

Definition:

A method that measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood oxygen levels.

Explanation:

Shows where in the brain activity is occurring during a task.

Example:

Identifying which brain regions activate during memory recall.

Memory hook:

fMRI = where brain activity happens

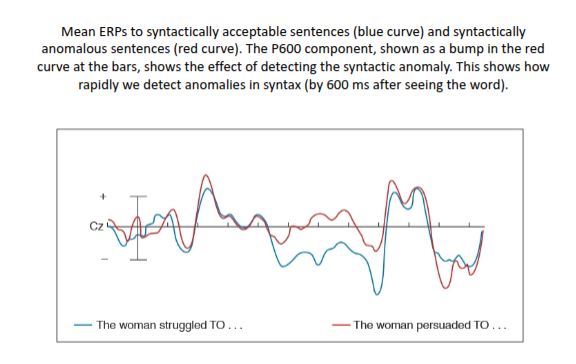

P600 Component

Definition:

An ERP component that appears about 600 ms after a word when the brain detects a syntactic (grammar) anomaly. “A positive wave that occurs about 600 ms after detecting a syntactic anomaly

Explanation:

Researchers showed people two types of sentences while recording EEG:

A syntactically acceptable sentence (blue curve)

A syntactically anomalous sentence (red curve)

When participants read the grammatically incorrect sentence, their brain produced a noticeable electrical “bump” at about 600 ms — the P600 — revealing how quickly we detect syntax errors during reading.

What the graph shows:

The red curve rises at the bars around 600 ms, while the blue curve does not. This difference is the P600 effect.

Connected term — ERP / EEG:

ERPs come from EEG recordings and show when the brain reacts during language processing.

Memory hook:

P600 = brain catches grammar mistake at 600 ms

Perceptrons

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“System learns to make correct responses to particular inputs (stimuli)”

What the slide says (included in the card)

Two layers of simple interconnected units (input, output)

Each unit may be active or inactive

The response the system makes depends on strengths of connections

Limited: Can’t learn some things humans learn (e.g., XOR problem)

Explanation (mine)

A perceptron is like the simplest “brain-like” learning system:

The input layer represents the stimulus features

The output layer represents the decision/response

Learning happens by changing connection strengths (weights) so the correct output becomes active for a given input

Why it’s limited (XOR):

Some patterns (like XOR) require combining inputs in a way that can’t be captured with only an input→output layer. That’s why later models added hidden units (extra layers) to learn more complex human-like patterns.

Connectionism

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Connectionism is a computer-based technique for modeling complex systems that is inspired by the structure of the nervous system.”

(a.k.a. Parallel distributed processing, neural networks)

Slide bullets (included):

Large number of simple but highly interconnected units

Three levels: input, hidden [internal, between input and output], output

Each unit can receive excitatory or inhibitory activity through connections with other units

Units simply sum activity. If sum is greater than a threshold, unit becomes active

Some connections are stronger than others

Learning consists of changes in the weights (strengths) of connections

Explanation (mine):

Connectionism models cognition as a network: lots of simple units interact, and intelligence comes from the pattern of activation and learned connection weights—not a single rule. The “hidden” layer is what allows the system to learn more complex patterns than a simple perceptron.

Interactive Activation Model (McClelland & Rumelhart, 1981)

Definition:

A model of perception showing that the brain recognizes things by building from small parts to a whole, while the whole also influences how the parts are interpreted.

Recognition happens because parts and wholes constantly influence each other.

The Three Layers (in the diagram)

1⃣ Feature layer – simple visual pieces (lines, angles, curves)

2⃣ Part layer – combinations of features that form parts (wings, fins, gills, fuselage)

3⃣ Category layer – the overall object (Jet or Shark)

How recognition happens

Your eyes detect features

Features combine into parts

Parts activate a possible whole object

At the same time:

The whole object you think it might be sends feedback down

That feedback changes how you interpret the parts and features

The brain goes back and forth between parts and whole until one interpretation “wins.”

Bottom-Up vs Top-Down

Bottom-Up: Parts build into the whole

Top-Down: The whole changes how you see the parts

Both happen at the same time.

Jets vs Sharks Experiment

Participants were told they would see either Jets or Sharks before seeing the drawings.

They were shown the same ambiguous picture made of simple features.

Jets group saw wings and fuselage

Sharks group saw fins and gills

Because the whole (Jet or Shark) was already active in their mind, it changed how they interpreted the parts.

What this proves

We do not passively see the world.

We constantly interpret parts based on the whole we expect.

This is connectionism applied to perception.

Memory hook

Parts build the whole, and the whole reshapes the parts

Embodied Cognition

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“The way that we think about and represent information reflects the fact that we need to interact with the world.”

Slide examples/bullets (included):

Perception: We can identify pictures of tools faster if our hands are positioned in the shape needed to use the tool.

Memory — Enactment Effect: We remember actions better than words; the best way to memorize a series of actions is to physically carry out the actions.

Comprehension — Mental Model: The deepest understanding of text is not abstract language, but forming a mental model of the world described, like a physical model.

Explanation (mine):

Embodied cognition argues that thinking is grounded in action: because our minds evolved to guide a body in the world, our concepts and understanding are shaped by perception, movement, and physical interaction—not just “brain computations” in isolation.

Data-Driven Processing

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Processing that is driven by the stimulus”

Explanation (mine):

Your perception begins with the actual sensory input you receive. You build understanding from the details of what you see or hear. This is also called bottom-up processing.

Conceptually-Driven Processing

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Processing that is driven by pre-existing knowledge and expectations”

Explanation (mine):

What you already know influences how you interpret incoming information. Your expectations and prior knowledge shape perception. This is also called top-down processing.

Word Frequency Effect

Definition (PROF’s exact slide words):

“Common words are recognized faster than rare words”

Explanation of the slide example (mine)

In a lexical decision task, people respond faster to words they see often in everyday life (like house) than to words they rarely see.

This happens because common words have been activated so many times before that the brain can recognize them quickly with less effort.

This effect shows how experience and exposure shape how quickly we process language.

Psychophysics

Definition (from slide): the study of the relationship between physical stimuli and the psychological experiences caused by them.

Examples from the slide

Research on just-noticeable difference (jnd): the minimal change needed for people to detect it.

Weber’s Law: jnd depends on proportional change, not absolute change.

Explanation (mine)

Proportional change means you notice a difference based on percentage change, not how much something changes.

Example:

Adding 1 pound to a 5-pound object is noticeable (20% change).

Adding 1 pound to a 50-pound object is not (2% change).

Your brain detects changes relative to what is already there, not by fixed amounts.

Distance Effect

Definition (from slide): The greater the distance or difference between the stimuli being compared, the faster the decision that they differ.

Examples from the slide

When comparing two dots, people decide faster which one is higher when the vertical distance between them is large.

When comparing numbers, people decide faster which is larger for 2 vs 9 than for 3 vs 4.

When comparing animals, people decide faster which is larger for rabbit vs elephant than for rabbit vs goat.

Explanation (mine)

Your brain is faster when the difference between two things is large.

Small differences require more mental comparison and take longer.

Symbolic Distance Effect

Definition (from slide)

Speed of judgments of differences between symbols is affected by distance on some symbolic dimension.

Examples from the slide

Pick larger number: (2 vs 5) faster than (3 vs 4)

Pick larger animal: (rabbit vs elephant) faster than (rabbit vs goat)

Explanation (mine)

Even when there is no physical distance, your brain treats symbols as if they lie on a mental scale. The farther apart they are on that mental scale, the faster the decision.

Definition (from slide)

Decisions are faster when the judged dimension matches the implied semantic dimension.

Semantic Congruity Effect

Definition (from slide)

Decisions are faster when the judged dimension matches the implied semantic dimension.

Examples from the slide

When judging digits:

Pick smaller faster with low numbers (3 vs 1)

Pick larger faster with high numbers (9 vs 7)

With animals:

“Pick smaller” faster with rabbit, mouse

“Pick larger” faster with hippo, elephant

Circles example (Banks et al., 1975):

Pick lower circle faster when told they are yo-yos

Pick higher circle faster when told they are balloons

Explanation (mine)

Your brain is faster when the question matches the natural meaning of the items. You process information more quickly when the judgment fits the implied concept (small things with “smaller,” large things with “larger,” balloons with “higher,” yo-yos with “lower”).

Sensation

Definition (from slide)

The reception of stimulation from the environment and the encoding of it into the nervous system.

All sensation is indirect.

Explanation (mine)

Your senses never receive objects directly. They receive energy (light, sound waves, chemicals, pressure) and convert it into neural signals.

Perception

Definition (from slide)

Perception: The process of interpreting and understanding sensory information.

Examples from the slide

Filling in the blind spot

There are no receptors where the optic nerve leaves the eye, yet we do not see a hole.Depth perception problem

The size of the image on the retina depends on both distance and actual size. The brain must determine which is responsible.

Depth cues listed on the slide

Binocular disparity — differences in perspective between the eyes

Accommodation — changes in the lens to bring an object into focus

Interposition — objects in front block objects behind

Motion parallax — near objects appear to move faster than far objects

Explanation (mine)

This slide shows what it means for perception to be interpretation. The brain fills in missing information and uses depth cues to figure out the world from ambiguous retinal images.

Retina

Definition (from slide content)

The retina contains receptor cells that convert light into neural signals.

Examples from the slide

Rods: 120 million, black & white vision, low light, periphery

Cones: 7 million, color vision (red, green, blue), bright light, concentrated in the fovea (most precise vision)

Bipolar cells: receive information from rods and cones

Ganglion cells: receive from bipolar cells; their axons form the optic nerve

Explanation (mine)

Light hits the retina → rods and cones detect it → signals pass to bipolar cells → then ganglion cells → then travel to the brain through the optic nerve.

Rods and Cones

Definition (from slide content)

Receptor cells in the retina responsible for detecting light.

Examples from the slide

Rods: black and white vision, low light, periphery

Cones: color vision, bright light, fovea

Explanation (mine)

Rods help you see in the dark and in your side vision. Cones help you see color and fine detail.

Fovea

Definition (from slide content)

Small area of the retina that provides the most precise vision.

Explanation (mine)

This is where cones are concentrated. When you look directly at something, you are placing it on your fovea for the sharpest detail.

Fixation

Definition (from slide)

Periods where the eyes remain relatively still and visual information is taken in.

Explanation (mine)

This is when actual visual processing happens. You only see clearly during fixations.

Saccade

Definition (from slide)

Jumps or jerks of the eye between fixations.

Can take 25–100 ms to execute (longer in reading: 150–175 ms).

Examples from the slide

Saccadic suppression: visual processing is suppressed during a saccade (even involving images)

Change blindness: failure to notice changes in stimuli that occur during a saccade

Explanation (mine)

During saccades, you are effectively blind. Your brain does not process visual input, which is why changes can happen without you noticing.

Trans-saccadic Memory

Definition (from slide)

The memory used across a series of eye movements to build an understanding of the visual world.

Object files (visual representations of individual objects) are used to track what is going on.

Explanation (mine)

Because vision shuts off during saccades, your brain uses memory to stitch together what you saw before and after each eye movement, creating the illusion of a continuous visual scene.

Partial Report Task

Partial Report Task

Definition (from slide)

A method used to measure sensory memory by asking subjects to report only part of a briefly presented display.

Visual example —

Letters flashed briefly, then disappear

A bar appears below one letter position

Subjects report which letter was there

Works well if bar appears within 250 ms

Auditory example —

Three sets of letters played at once

A tone indicates which set to report

Sensory memory lasts longer than visual

Touch example —

24 regions on fingers mapped to letters

Airpuffs delivered to regions

Subjects report which were stimulated

Explanation (mine)

These experiments show that sensory memory holds a large amount of information, but only for a very short time. People fail at whole report not because they didn’t see everything, but because the memory fades before they can report it. The cue proves the information was briefly stored.

What this shows (slide point)

The information from the entire letter display is still available in sensory memory for a very brief time, even though subjects cannot report all of it at once.

Explanation (mine)

People cannot report all the letters because sensory memory fades quickly, but the bar proves that the letters were briefly stored. This is evidence for a short-lived, high-capacity sensory memory.

Backward Masking

Definition (from slide)

The presentation of a later stimulus can interfere with the perception of an earlier stimulus if it is presented where the earlier stimulus had been.

From the slide

Analogous to an “erasure” process

Examples from the slide

Beta movement: Viewing multiple pictures in succession creates the illusion of movement (movies, cartoons)

Phi phenomenon: Two stimuli in different locations can appear to move toward each other

Explanation (mine)

The second image overwrites what was briefly stored in sensory memory from the first image. This interaction between sensory memory and masking is what allows the brain to create illusions of motion.

Sensory Memory

Definition (from slide)

A temporary buffer that holds sensory information for brief periods of time.

From the slides

First demonstrated in George Sperling partial-report task

Shown in visual, auditory, and tactile modalities

Auditory sensory memory may last longer than visual

Also called:

Icon / Iconic memory (visual)

Echo / Echoic memory (auditory)

Sensory register

Explanation (mine)

This is the very first stage of memory. It briefly stores raw sensory information before it disappears.

Modality Effect

Definition (from slide)

Advantage for auditory presentation over visual presentation at the end of a list in immediate serial recall.

Professor’s example —

Subjects hear or see a list of digits

Must recall them in order

The last items are remembered better when heard than when seen

From the slide

Attributed to longer-lasting auditory sensory memory

The last item is still “echoing” while recall begins

Explanation (mine)

Because echoic memory lasts longer than iconic memory, the final sounds are still present in sensory memory when you start recalling the list. That gives hearing an advantage over seeing at the end of a list.

Suffix Effect

Definition (exact slide wording)

“A speech sound presented after the end of list will selectively hurt recall of last items.”

Seen as example of backward masking.

This means the later sound is interfering with the memory trace of what came just before it, almost like erasing it.Visual suffixes have no effect.

If you flash something on a screen after the list, it does not hurt recall. This tells us the effect is not visual — it is tied to sound/speech processing.Meaning of auditory suffixes is irrelevant. Physical similarity of suffix to list items determines magnitude of suffix effect.

The suffix does not have to be meaningful. It just has to sound like speech. That is what disrupts memory.

Crowder & Morton (1969) — Modality Effect

Auditory presentation of digits → better recall of last items than visual presentation.

When digits are heard instead of seen, people remember the last one or two much better.Why? The last items are still “echoing” in echoic sensory memory.

This shows that auditory sensory memory lasts long enough to help recall the end of a list.

What happens when the suffix is added

A spoken sound is played immediately after the list.

This new sound replaces the echo of the last digits in sensory memory.Recall of the last items suddenly becomes poor.

This is evidence that those last items were relying on echoic memory, and the suffix destroyed it.

Greene & Crowder (1984) — Lipreading experiment

Subjects watched a person silently mouth the digits (no sound).

They had to lipread the list instead of hearing it.The suffix effect STILL occurred.

This proves the memory is not just for sound — it is for speech information.

Why lipreading works like hearing (next slide)

Auditory sensory memory includes any information used to identify speech, not just sound waves.

The brain treats lip movements as part of the same speech-processing system.Supported by the McGurk Effect.

What we see the lips do can change what we think we hear. Vision and hearing work together for speech.

What this shows about the process

The last items in a list are stored in echoic sensory memory.

That is why they are easy to recall when heard.That memory is speech-coded, not just sound-coded.

It stores information in a format related to speech processing.A speech-like suffix overwrites that memory.

Because it uses the same system, it replaces the previous trace.A visual suffix does nothing.

It does not match the speech code, so it cannot interfere.

Explanation (why this matters)

The suffix effect proves that sensory memory for hearing is really a speech-processing memory system.

Anything that resembles speech — even silent lip movements — can overwrite what is being held there.

Gestalt Principles of Grouping

Gestalt Principles of Grouping

Definition (from slide content)

How the visual system organizes incoming patterns into meaningful wholes using built-in grouping rules.

Figure–Ground Principle: Parts of the image are segregated into a figure (object of focus) and a background.

You automatically see a vase or two faces in the classic image because the visual system decides what is figure and what is ground.Proximity: Nearness is used to group.

Dots that are close together are seen as belonging to the same group, even if they are identical to other dots farther away.Similarity: Similar objects are grouped together.

Circles among squares will be grouped as one set even if spacing is equal.Closure: Completion of images with missing parts.

You see a full triangle even when the edges are not actually drawn.Good Continuation: Edges are seen as continuing smoothly along a path.

Crossing lines are perceived as two continuous lines, not four short segments.

Explanation (mine)

These principles are examples of data-driven processing.

The grouping happens automatically from the stimulus pattern itself, without needing prior knowledge.

Data-Driven Processing

Professor’s definition (exact from slide)

Processing is driven by the stimulus pattern, the incoming data.

What EACH slide example is showing (with explanation)

Template approach

You would recognize objects by matching them to exact stored patterns.

This fails in real life because objects change size, angle, lighting, and orientation.

This is why the slide says it has limited use.

Feature-detection approach

Instead of matching whole patterns, the visual system breaks the stimulus into parts (lines, curves, angles).

Recognition happens after these features are detected and combined.

This is the foundation for the rest of the examples on the slide.

Visual search — Neisser (1964): “Find the Z”

When you scan a messy string of letters, you don’t read every letter.

Your visual system looks for the features that make a Z (two diagonals + one horizontal).

You find it faster when those features stand out.

This shows perception begins with feature detection, not meaning.

Selfridge’s Pandemonium (1959)

This model literally maps how feature detection works:

Data demons = record the raw visual input

Computational demons = detect specific features (lines, angles)

Cognitive demons = recognize whole letters from those features

Decision demon = decides which letter it is

This proves two things written on the slide:

Pattern recognition depends on features

It happens with parallel processing (many demons working at once)

Biederman’s Recognition by Components (1990)

Objects are recognized by breaking them into geons (basic 3D shapes like cones, cylinders, bricks).

Your visual system finds edges and vertices, then checks memory for an object with that geon arrangement.

This is exactly like recognizing letters from features.

Recoverable vs Non-recoverable objects images

When the geons are still visible → you can recognize the object.

When the geons are destroyed → recognition becomes very hard.

This visually proves that perception depends on parts first, whole second.

What all of this is proving (your understanding)

You perceive by building from parts → to whole.

You do not start with meaning, memory, or context.

You start with what hits your eyes, detect features, combine them, and only then recognize what the object is.

That’s why every example on this slide starts with features: letters → lines, objects → geons, search → shapes, pandemonium → feature demons.

This is bottom-up perception.

Selfridge’s Pandemonium Model

Definition from slide context

A model of pattern recognition showing how letters are identified through layers of feature detection and parallel processing.

What the slide lists (Pandemonium system)

Data demons — encode the visual pattern

Computational demons — detect features (lines, angles)

Cognitive demons — match features to whole letters

Decision demons — decide which letter is present

Slide emphasis

Importance of feature detection in pattern recognition

Pattern recognition requires PARALLEL PROCESSING

Pattern recognition is a problem-solving process

Explanation (mine)

This model shows pure data-driven (bottom-up) perception. Your system does not “see a letter.” It detects lines and angles first, processes many options at once, and then decides what the letter must be.

Recognition by Components Theory (Biederman, 1990)

Definition from slide

We recognize objects by breaking them down into their components and then look up this combination in memory to see which object matches it.

What the slide lists

Objects have a small number of basic primitives: geons

(cylinders, bricks, wedges, cones)Objects are stored in memory in terms of:

the geons they contain and the arrangement of the geons

(like words stored as letters and their arrangement)We parse objects into geons by:

finding edges and scanning where lines intersect (vertices)

Images on the slide (Primitives / Recoverable vs Non-recoverable)

Recoverable objects: even when partially blocked, you can still identify the object because the geons are visible.

Non-recoverable objects: when vertices are hidden, you cannot identify the object because you cannot detect the geons.

Criticism listed on slide

Model relies too heavily on bottom-up processing. In real perception, top-down processing (context, overall shape) also matters.

Explanation (mine)

This theory explains why you can recognize a chair even if part of it is covered — as long as you can still detect the basic shapes. But if the key intersections (vertices) are hidden, recognition fails because the brain cannot recover the geons.

Agnosia

Professor’s definition (exact from slide)

Injury (especially to left occipital or temporal lobes) may lead to agnosia (a failure or deficit in recognizing objects, even though basic sensory ability is unimpaired). These people cannot put features together to form whole objects.

Agnosia (general)

Vision is working. The eyes and early sensory system are fine.

The problem is pattern recognition — the person cannot combine detected features into a meaningful whole.

This is direct evidence for the feature-detection approach you just studied: If you can’t combine features → you can’t recognize objects.

Associative agnosia

Identification of the object seems unimpaired, but the patient seems to have lost the pathway to the name and meaning of the object.

What this means:

They can copy the drawing perfectly.

They can describe the features.

But they cannot tell you what it is.

So: Feature detection works.

Putting features together works.

Meaning is disconnected.

Prosopagnosia

A disruption of face recognition while object recognition remains intact.

What this shows:

The brain has specialized mechanisms for faces separate from objects.

You can recognize a chair but not your mother’s face.

What this slide is proving for you

This is neurological proof that:

Pattern recognition depends on:

Detecting features

Combining features into wholes

Connecting wholes to meaning

When brain damage breaks one step, recognition fails in a very specific way.

That’s why this slide comes right after Pandemonium and geons.

Geons

Professor’s definition (from the slide)

Objects tend to have a small number of basic primitives, simple three-dimensional forms (geons: e.g., cylinders, bricks, wedges, and cones).

Common objects are stored in terms of the geons they contain and the arrangement of the geons (just like words are stored in terms of letters and their arrangement).

We break (parse) objects into geons by finding the edges of objects and scanning where lines intersect (vertices).

What this means (clear explanation)

__ are the building blocks of objects.

Just like:

Letters → make words

Geons → make objects

Your brain does not store a picture of every object you’ve ever seen.

It stores a recipe:

“This object = cylinder + brick + wedge in this arrangement”

So when you see a mug, you don’t recognize “mug.”

You recognize:

Cylinder (body)

Curved handle shape

Their spatial arrangement

That combination = mug.

Why the slide shows recoverable vs non-recoverable objects

If enough geons and vertices are visible → object is recoverable (easy to recognize).

If the edges/vertices are hidden → object becomes non-recoverable (hard to recognize).

Because you can’t parse it into geons.

Why this is on the critical terms list

This is the core of Biederman’s Recognition-by-Components theory and is evidence for:

Data-driven (bottom-up) processing in pattern recognition.

Conceptually-Driven Processing

Definition (exact from slide)

Context and expectations can play a role in our perception of the world.

Tulving & Gold (1963) — Main experiment from the slide

They measured how long (in milliseconds) a word had to be flashed before people could identify it.

The key manipulation:

How many context words were shown before the target word.

The graph on the slide shows:

As the number of context words increases from 0 → 1 → 2 → 4 → 8,

the time required to name the word drops.

This drop is much stronger when the context is appropriate than when it is inappropriate.

So when the sentence makes sense, people can recognize the word much faster.

What this experiment is proving

Perception is not just driven by what hits the eyes.

Your brain is using context and expectations to help interpret the stimulus.

You need less visual information to recognize something when you can predict it.

This is top-down processing in action.

Word-Superiority Effect (Reicher, 1969)

People can perceive words faster than nonwords or individual letters.

Examples from the slide:

J vs JNIO vs JOIN

J vs C

Performance is best for words, then letters, then nonwords.

What underlies the Word-Superiority Effect (from slide)

Familiarity with the stimulus matters:

Common words are read faster than rare words

Words in normal case are read faster than mixed case (e.g., wORd)

Pseudowords (e.g., MAPE) are easier than illegal nonwords (e.g., MPEA)

Explanation (mine)

All of these examples show the same thing:

Your brain does not wait to build perception from pieces. It uses knowledge, language rules, expectations, and context to recognize things quickly.

This is why words, context, and familiarity speed up perception.

Word-Superiority Effect

Definition (from slide)

People can perceive words faster than nonwords or individual letters.

Reicher (1969) — exact example from slide

Subjects briefly see one of these and must report a letter:

JOIN

JNIO

J

Or:

J vs C

Result from slide:

Performance is best for words → then letters → then nonwords

Explanation (mine)

When the letter is inside a real word (JOIN), people identify it more accurately than when it is alone (J) or inside a scrambled nonword (JNIO).

This means the brain is using knowledge of words to help identify the letter. You are not reading one letter at a time — the word context helps you.

What underlies this effect (from slide)

Common words are read faster than rare words

Words in normal case are easier than mixed case (wORd)

Pseudowords (MAPE) are easier than illegal nonwords (MPEA)

Explanation (mine)

All of these show that familiarity with spelling patterns and word shapes helps perception.

Your brain uses what it already knows about language to recognize what it is seeing faster.

What this proves:

This is strong evidence of conceptually-driven (top-down) processing.

Perception is influenced by knowledge, experience, and context — not just the visual stimulus.

Depth Perception — Cues

Definition (from slide)

We use a number of cues to distinguish between depth (distance) and actual size of objects.

From slide

Binocular disparity — differences in perspective between the eyes

Accommodation — changes in the lens to bring an object into focus

Interposition — relative positions of objects in front of or behind others

Motion parallax — rate of apparent motion of near and far objects

Explanation (mine)

The image on your retina cannot tell you if something is small and close or large and far because both produce the same image size.

Your brain solves this using these cues:

With binocular disparity, each eye sees a slightly different image. The brain compares them to calculate depth.

With accommodation, your eye muscles change the lens shape. The brain senses this muscle effort to estimate distance.

With interposition, if one object blocks another, the blocking object must be closer.

With motion parallax, when you move your head, nearby objects appear to move quickly, while distant objects move slowly.

These cues allow the brain to reconstruct 3D space from a 2D retinal image.

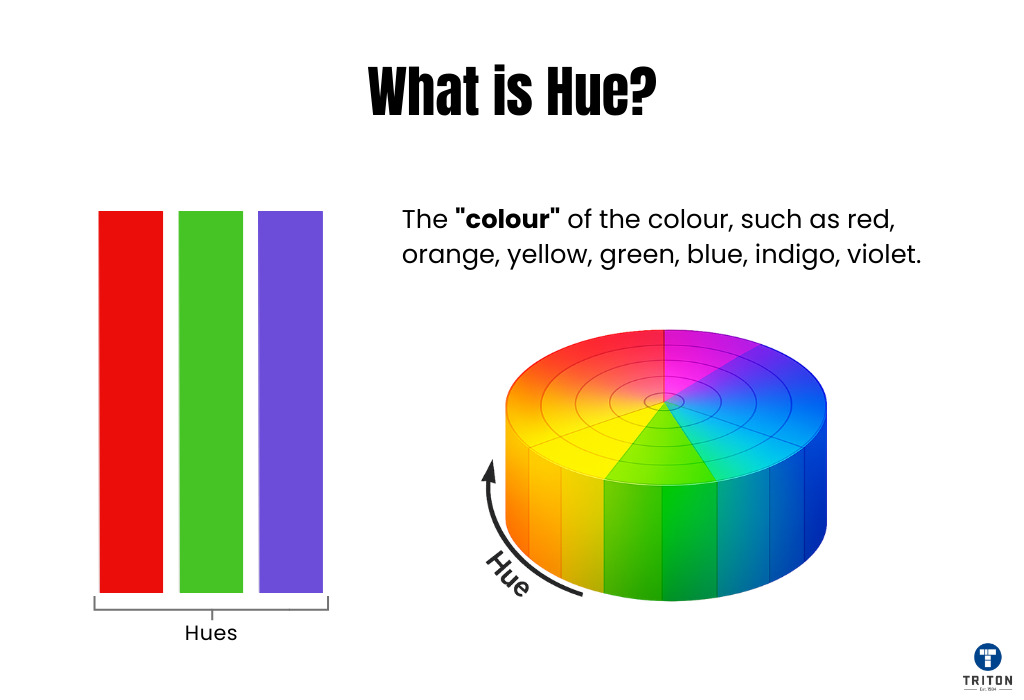

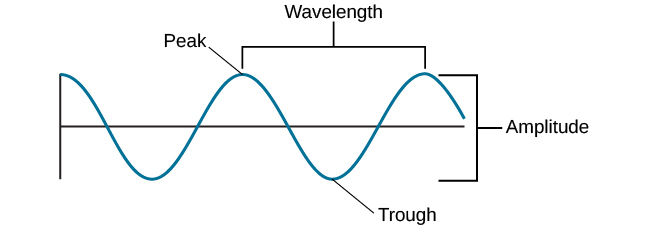

Hue

Definition (from slide context)

Wavelength (360–750 nm visible spectrum) is the primary determinant of hue.

Explanation (mine)

Hue is what we call “color.”

Short wavelengths are seen as blues/violets, medium as greens/yellows, long as reds.

Your visual system is decoding wavelength and turning it into the experience of color.

Brightness

Definition (from slide context)

Amplitude is the primary determinant of brightness.

Explanation (mine)

Brightness is how intense or strong the light appears.

Larger amplitude waves carry more energy and are perceived as brighter light.

Change Blindness

Definition (from slide)

Failure to notice changes in stimuli that occur during a saccade.

From slide

Occurs because of saccadic suppression

Visual processing is suppressed during eye movements

Explanation (mine)

When your eyes jump (saccade), your brain briefly shuts off vision so you don’t see blur.

If something changes during that split second, you often miss it.

This shows perception is not continuous — it’s stitched together from snapshots.

Lipread Lists, Recall of

Definition (from slide context — Greene & Crowder, 1984)

Lipreading produces the same modality and suffix effects as hearing.

From slide

Subjects watched video of a person reading digit lists

Sound removed → subjects lipread

Lipreading showed same recall pattern as auditory presentation

Explanation (mine)

This proves auditory sensory memory is not strictly about sound.

Visual information from lip movements feeds into the same memory system used for hearing.

Your brain uses multiple sensory inputs to build what feels like “auditory” memory.

Template Approach

Definition (from slide)

Classification is done by stored models of all categorizable patterns; this is of limited use.

Explanation (mine)

This theory says you recognize objects by comparing what you see to exact mental pictures (templates) stored in memory.

So to recognize the letter A, you would need a stored template for:

A in different fonts

A in different sizes

A in different orientations

A handwritten, typed, bold, italic, etc.

This becomes unrealistic because the world is too variable.

You would need thousands of templates for every object.

That’s why the slide says this approach is of limited use.

Feature Detection Approach

Definition (from slide)

Classification is done by breaking patterns down into features.

Examples from slide

Neisser (1964) visual search for Z

Selfridge’s Pandemonium model

Explanation (mine)

Instead of matching entire pictures, the brain looks for basic parts:

Lines

Angles

Curves

Edges

For example, to recognize A, you don’t match a full template.

You detect:

Two diagonal lines

One horizontal line

Then your brain assembles those features into the letter.

This works because features stay the same even when size, font, or style changes.

This is why feature detection explains perception much better than templates.