Critical thinking terminology

1/129

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

130 Terms

Practical Person

• when someone’s view on Fing is dismissed as irrelevant because they have no practical experience of Fing.

• The mistake is to think that you can’t have any insight at all into something in which you have no practical experience

ex: Lizzo saying if you don’t make music you can’t review it

Raising the Bar

when someone tries to undermine someone’s else’s argument by unjustifiably raising the the evidential threshold for their conclusion.

• The fact that someone’s evidence doesn’t make their conclusion absolutely certain doesn’t mean that their evidence is not strong.

• Evidence can be (very) strong but not conclusive

ex: climate scepticism “we can’t be certain!!”

What Can We Do about raising the bar fallacy?

• Remember that whilst questioning the strength of evidence is good, the fact that the strength of some evidence can be questioned does not make it weak.

• Even very strong evidence can be questioned!

• The right question is not: “Could this evidence be true whilst the conclusion is false?”

• It is: “How much more likely are we to see this evidence if the conclusion is true than if it is false?”

Insisting on Definitions

Most everyday words and concepts lack precise (or even imprecise) definitions (‘person’, ‘tree’, ‘car’, ‘mountain’, ‘planet’…).

• Just because a word or concept does not have a precise definition does not mean that it cannot be successfully used to state truths and make

arguments.

• ‘What do you mean by “good”?’

Extensional

By listing some or all the things to which the terms applies.

• “A province of Ireland is either Munster, Leinster, Connacht, or Ulster

Ostensive

By drawing attention to exemplars.

• “This is a T-square”

Strict Intensional

The precise meaning of the term: “A vixen is a female fox”

Informal Intensional

The informal meaning of the term: “An apple is the fruit

of an apple tree”

Practical Intensional

The meaning of the term in the context of some

practical goal: “For our purposes, ”adult” means “over 18”.

Appeal to the Majority

• An Appeal to the Majority fallacy occurs when the mere fact that many people

believe something is treated as evidence for its truth.

• Majority belief fails the Evidence Test:

• The likelihood something is true given that many people believe it is not greater

than the likelihood it is true given that few people believe it.

Certain forms of collective belief can indeed be epistemically valuabl

• Condorcet’s “Jury Theorem” shows that if each member of a group has a better-than-chance probability of being right, and votes independently, the majority’s belief is more likely to be true than any individual’s.

• The “wisdom of crowds” phenomenon (Galton, Surowiecki) illustrates how aggregated judgments (e.g., estimating an ox’s weight or market prices) can converge surprisingly close to truth.

• However, these models rely on independence and diversity of belief-

formation.

• When those are lost (e.g. through echo chambers, herding, or shared misinformation sources), popularity ceases to be evidential and becomes epistemically dangerous

• At a 1906 country fair in Plymouth, 800 people participated in a contest to estimate the weight of a slaughtered and dressed ox.

• Francis Galton (cousin of Charles Darwin) observed that the median guess of 1207 pounds was accurate within 1% of the true weight of 1198 pounds.

Appeal to Popularity

when the mere fact that something is

popular is treated as evidence for its being desirable.

• Popularity fails the Evidence Test:

• The likelihood something is desirable given that it is popular is not greater than

the likelihood that it is desirable given that it is not popular

What Can We Do about appeal to majority and popularity?

• Appeals to the majority and popularity are motivated by the groupthink bias

that encourages us to conform to the opinions/behaviour of those around us.

• Due to this bias, views or things that are popular are typically automatically

assumed to have evidential weight or positive value.

• Counteracting the groupthink bias requiring having the ability to consider the

strength of the evidence for a claim on its own merits, independent of its

popularity or rate of acceptance.

• Note that groupthink can also affect the prior probabilities we assign to

various claims, i.e. how likely we consider them to be before we have

received any evidence at all

Appeal to Exclusivity

• An Appeal to the Exclusivity fallacy occurs when the mere fact that something

is exclusive is treated as evidence for its being desirable.

• Exclusivity fails the Evidence Test:

• The likelihood something is desirable given that it is exclusive is not greater

than the likelihood that it is desirable given that it is not exclusive

What Can We Do about appeal to exclusivity?

• People tend to assume that rare or difficult-to-obtain things are more

valuable, even when scarcity is artificial or irrelevant to intrinsic quality.

• This is called the scarcity heuristic (def): when access to an item, belief, or

group is limited, our brains interpret that as a cue to value: “If it’s rare, it must

be good or desirable”.

• Robert Cialdini’s Influence (1984) identified scarcity as one of the six

universal principles of persuasion; experiments show that people rate items

as more attractive when told they’re scarce or exclusive.

• Counteracting the scarcity heuristic requires considering the desirability of

something on its own merits, independent of its exclusivity.

• “How desirable would this be if I found it in TKMaxx?”

Appeal to Ancient Wisdom

when the mere fact that

something was believed/considered desirable by an ancient people or

culture is treated as evidence for its truth/desirability.

• Ancient Wisdom fails the Evidence Test:

• The likelihood something is true/desirable given that it was

believed/considered desirable by an ancient people or culture is not greater

than the likelihood that it is is true/desirable given that it was not

believed/considered desirable by an ancient people or culture

ex: garlic doesn’t destroy magnets

Ad Hominem

when the fact that someone has a certain

negative character/history is treated as evidence against their

beliefs/conclusions.

• Ad Hominem fails the Evidence Test:

• It’s not true that someone having a negative character/history lowers the

probability of their beliefs/conclusions.

tu quoque

sub area of ad hominem

• Suppose your GP, who smokes, advises you strongly to give up smoking: does

that make any difference as to whether you should give up smoking

What Can We Do about ad hominem?

• When we care about a subject, we should try to distinguish the arguments

from their sources.

• We will not make an error of rationality if we always assess arguments on

their own merits: the premises are either true or not, and the arguments are

either strong or not

• Similarly, someone’s character can be relevant to whether they ought to

hold a certain position

Ad Hominem Circumstantial

• A version of the ad hominem fallacy that involves rejecting someone’s

conclusion on the basis that they benefit from the truth of the conclusion.

• ‘Oh you would say that!’

• ‘Businesses have argued for lower corporation tax, but clearly they have an

interest in paying less tax!’

cant dismiss an argument judt because they may benefit from the argument

Lie

It s a lie when:

S states P

S believes P is false

S tells another person and intends to convince other person that P is true

Frankfurt Bullshit

Bullshit (def) is content that is presented with no regard for the truth but

instead with the intention to impress, overwhelm, persuade, convince, etc.

• Is all bullshitting bad?

• What about e.g. poetry, or banter?

• Isn’t some bullshit presented with regard for the truth?

we are in a bad environment :(

Bullshitter vs lier

the truth value doesn't matter to bullshitter

Intentionally wrong matters for lier

Gerry Cohen Bullshit

unclarifiable discourse, that is, that is not only obscure, but which cannot be rendered unobscure

where any apparent success in rendering it unobscured creates something that isn’t recognizable as a version of what is said

Detox

• 1. A medically administered procedure used to treat e.g. patients with severe

drug or alcohol addictions or patients who have accidentally ingested certain

poisons.

• 2. Eating well, sleeping well, exercising, not smoking, and drinking in

moderation.

• 3. Bullshit designed to sell things/promote personalities/virtue signal

How do we fix bullshit?

we are being hacked (particular interest in danger, gaining attention social media = bullshit, ragebait) - it's a systemic issue

Reason

the ability or capacity to make

inferences

Inference

to judge that some proposition (the conclusion) is rationally supported by some other proposition(s) (the premise(s)).

Reasoning

the process of making inferences

Good inference

he premises provide rational support for the conclusion

Bad Inference

the premises do not provide rational support for the conclusion

Rational Support

if all the premises were true, the conclusion would more likely true than false

Inferential Strength

the premises provide rational support for the conclusion.

Independence

The strength of an inference is completely independent from the question of whether the premises of that inference are true

motivated reasoning

the well-confirmed tendency for our reasoning and assessment of

evidence to be unconsciously driven by our emotions, desires, or

pre-existing beliefs.

type of cognitive pitfall

cognitive pitfall

A systematic, unconscious pattern of thought that negatively effects our ability to reason well.

System 1 processes are

Automatic:

• Unconscious:

• Intuitive:

• Associative:

• Fast:

• Low effort:

• Prone to biases:

• Context-dependent:

• Our default mode:

System 2 processes are

• Deliberate:

• Conscious:

• Analytical:

• Sequential:

• Slow:

• High effort:

• Less biased:

• Rule-based:

• Engaged when stakes are high:

Ego Depletion

When our (limited) store of mental energy is low, or directed elsewhere, we’re likely to struggle to maintain self-control, stay focused, and reason well.

Fast Answer Bias

The tendency to respond to a question with the answer that seems

most obvious, fits a pattern or story, meets our expectations, or

makes us happy

Wishful Thinking Bias

The tendency to believe something primarily because we want it to

be true, rather than because evidence supports it

Confirmation Bias

The tendency to notice, focus on, and give more weight to

potential evidence for our pre-existing beliefs, and to neglect or

discount contrary evidence

Leo Tolstoy, 1894

The most difficult subjects canbe explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already;

but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him

Status Quo Bias

The tendency to notice, focus on, and give more weight to

potential evidence for views that are already widely accepted or

reflect how things actually are

The Framing Effect

The tendency to let the way information is presented to us (its

frame) shape our decisions and judgments, even when the

underlying facts are identical

The Evidence Primacy Effect

The tendency to let the order in which information is presented to

us (its frame) shape our decisions and judgments, even when the

underlying facts are identical

The Anchoring Effect

The tendency for our judgements to be affected by

previous experiences, even when those experiences are

irrelevant to the rationality of the judgement

soldier mindset

our thinking is guided by the question

“Can I believe it?” about things we want to accept, and “Must I

believe it?” about things we want to reject

Reasoning is like combat.

• Current beliefs must be defended

at all costs.

• Will use any means necessary.

• Driven by fear of embarrassment

(System 1).

• Main Character Energy.

• Comforting. High self-esteem. Good morale. Persuasive. Good image. Sense of belonging

scout mindset

our thinking is guided by the question “Is it true?

• Reasoning is like map-making.

• Current beliefs are always open to

revision.

• Will only use quality tools.

• Driven by desire for knowledge.

• Very System 2.

Making good judgments about which

problems are worth fixing, which

risks are worth taking, how to pursue

their goals, who to trust, what kind of

life they want to live, and how to

improve their judgment over time.

• Has a more accurate picture of the

world.

Argument

A set of propositions, exactly one of which is the

conclusion, and the rest of which are premises intended to

provide inferential support for the conclusion

Propositions

• The meanings of (assertive) sentences.

• The contents of beliefs and desires.

• The primary bearers of truth and falsity.

Fact

A true proposition.

Premise

A proposition that is intended to inferentially

support the conclusion of an argument

Conclusion

The proposition that the premises of an

argument are intended to inferentially support

Inferentially Strong Argument

An argument is inferentially

strong just in case if the premises were true, the conclusion would

be more likely true than false

Deductively valid argument

if it is impossible for both the premises to be true

and the conclusion to be false

Inductively strong argument

An argument is inductively strong just in case it is inferentially strong, but not deductively valid.

Focus

The inferential strength of an argument depends only on

the stated premises of that argument

defeater

is extra information which, when added to the

premises of an inductively strong argument, generates an

argument that is inferentially weaker than the original argument

Sound argument

An argument is sound just in case it is

inferentially strong and all its premises are true

Independence

The inferential strength of an argument is

completely independent from the question of whether the

premises of that argument are true

Truth

A proposition p is true just in case p

Truth Relativism

Propositions are true/false relative to

people, cultures, times etc., but nothing is true full stop

Persuasive argument

An argument is persuasive just in

case (roughly) people who are presented with the premises and

don’t already accept the conclusion are likely to accept the

conclusion.

Explanations

A set of propositions, exactly one of which is

the thing to be explained (the explicandum), and the rest of which

(the explanans) are intended to explain why the thing to be

explained is true

Arguments are (or could be) intended to provide reasons for

someone to believe something.

• Explanations are (or could be) intended to help someone

understand why something is true

Implicit premises

are intended but not stated premises of

an argument.

proof

is a deductively valid argument with premises that

are known for certain.

prior probability

Before we get any evidence for a hypothesis H, we have some

sense of how likely H is to be true

P (H)

posterior probability

In light of this evidence E, you might revise your confidence in the

belief.

P(H|E)

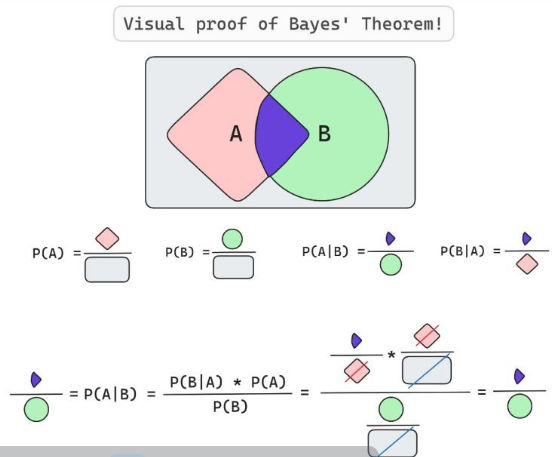

Bayes’ Theorem

Think of the probability of the hypothesis given the evidence— P(H|E)—as the overlap between the evidence and hypothesis divided by the evidence

Improving Priors

A good way to gain a more accurate picture of the prior

probabilities of our hypotheses is to actively consider multiple

relevant hypotheses

This helps to mitigate confirmation bias, which causes us to focus

on hypotheses that fit with what we already believe

Evidence

A proposition A is evidence for a hypothesis H just in case the

probability of H given A is higher than the prior probability of H, i.e.

of H in general.

• Formally: E(A, H) =(def) P(H|A) > P(H)

Sometimes, a proposition is not evidence for a hypothesis

• Then we can say that A is independent of H.

• Formally: I(A, H) iff P(H|A) = P(H).

Sometimes, a proposition is evidence against a hypothesis

• In that case, the probability of H given A is lower than the prior

probability of H.

• Formally: E(A, NOT-H) iff P(H|A) < P(H)

Finding Evidence

• When we learn some new fact A, and we want to know whether it

is evidence for some hypothesis H, we can ask ourselves:

• Is P(H|A) > P(A)?

The Evidence Test

Is A more likely to be true if H is true, or if H is

false?

• Is P(A|H) > P(A|NOT-H)?

The First Rule of Evidence

If we receive evidence for H, we

should become proportionally more confident that H is true.

• But just because we have some evidence for a hypothesis H

doesn’t mean we should believe that H is true.

• That depends on the prior probabilities of H and of A

General Lessons

1. The less likely something is in general, the more evidence is

required to make it likely.

• Having accurate priors for your hypothesis is extremely important.

• 2. The more likely something is in general, the weaker it is as

evidence for a hypothesis.

• Having an accurate priors for your evidence is extremely

important.

The Strength Test

How many times more likely is A to be true if H

is true than if H is false?

• In other words: How many times greater is P(A|H) than P(A|NOT-

H)?

The Counterfactual Test

How would things look if H were false

and some alternative hypothesis were true

radical scepticism

the view that we we can’t know anything about

external reality

Conclusive Evidence

S’s evidence E for a hypothesis H is

conclusive just in case it is impossible for S to have E and for H to

be false

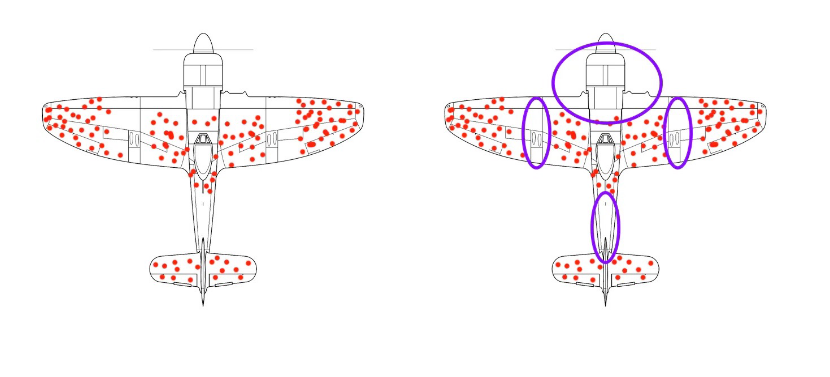

Selections Effects

is a factor that selects which

observations are available to us in a way that can make our

evidence unreliable if we are unaware of it

Survivor Bias

Selective Noticing

We tend to notice the confirming instances (top-left) and

ignore/fail to notice the other instances (which includes all the

disconfirming instances)

Media Selection Bias

Our brains are suited to life in small tribes, so our intuitive heuristic for scary

stories is simple: if something very bad happened to someone else, I should

worry that it might happen to me

Brandolini’s Bullshit Asymmetry Principle

The amount of energy necessary to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude greater than to produce it

Education bullshit

Have to learn bs from, orgs, companies, jobs, etc for work

There is no substance in text. It's giving chatGPT!

Evidence

S’s evidence for a hypothesis H is anything S knows that should increase S’s confidence in H

inductive premise

is a proposition that, if true, makes the conclusion probable (>50% likely) in light of the evidence

Types of Inductive Arguments

• Statistical Syllogism.

• Inductive Generalisation.

• Argument from Analogy (Analogical Inference)

• Abduction (Inference to the Best Explanation)

Statistical Syllogism

take evidence about a particular individual

and combine it with an inductive premise about a wider group,

such as “most As are Bs” or “n% of As are Bs”.

• Basic Form:

• 1. x is A.

• 2. Most/n% of As are B.

• C. A is B.

• (n will be greater than 50% and lower than 100%)

ex:

• 1. Alex is a musician.

• 2. Most musicians can read music.

• C. Alex can read music.

• Lyons & Ward: The key requirement is to use the “narrowest

reference class” for which statistical information is available. avoid defeaters basically

Inductive Generalisation

• Inductive Generalisations take evidence about an observed group

(the sample) and draw a more general conclusion about a wider,

unobserved group (the population).

• The evidence can be drawn from e.g. personal experience,

experimental data, or polling data

ex:

• 1. Denmark have never won the World Cup before.

• C. Denmark will not win the next World Cup.

Risks

Anecdotal evidence

Argument from counterexamples: This is the fallacy of trying to reject a statistical claim by citing one or a handful of notable individual counterexamples

defeaters

samples and Representativeness

The Law of Large Numbers

The larger the sample, the more likely

it is that its proportions closely reflect those of the population as a

whole.

The Law of Small Samples

Smaller samples tend to generate unrepresentative results

Uniformity Principle

• All inductive generalisations rely on the premise that the

unobserved sample resembles/will resemble the observed

sample: the Uniformity Principle (UP).

• UP is usually implicit and should not be included even in formal

statements in inductive arguments

David Hume (1711-1776) and the problem of induction

• 1. The justification for believing UP must be either a proof or an inductive argument.

• 2. It can’t be a proof, since we can coherently imagine UP being false.

• 3. It can’t be an inductive generalisation, since they rely on UP, and circular arguments can’t provide justification.

• C. There is no justification for believing UP.

• This is called ‘the problem of induction’

Argument from Analogy

• This kind of argument moves "sideways," drawing conclusions

about one individual based on premises about another individual

• Basic Form:

• 1. x and y are similar in certain respects.

• 2. x has feature F.

• C. y also has feature F

Risks

we may be impressed by certain similarities whilst

overlooking crucial differences that actually determine whether

the analogy holds.

Abduction (Inference to the Best Explanation

• Abduction involves inferring something unobserved because it

provides the best explanation for the things that have been

observed.

• 1. Smith has symptoms X, Y and Z.

• 2. The best overall explanation for (1) is that Smith has Disease A.

• C. Smith has disease A.

Risks

Confirmation bias

he simplest theory is not always the best

Three standard measures of central tendency

• Mean (def): The sum of the values divided by the number of

values.

• Median (def): The centrally ranked value.

• Mode (def): The most common value.