Topic 9: Strengthening Mechanisms in Steel

1/8

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

9 Terms

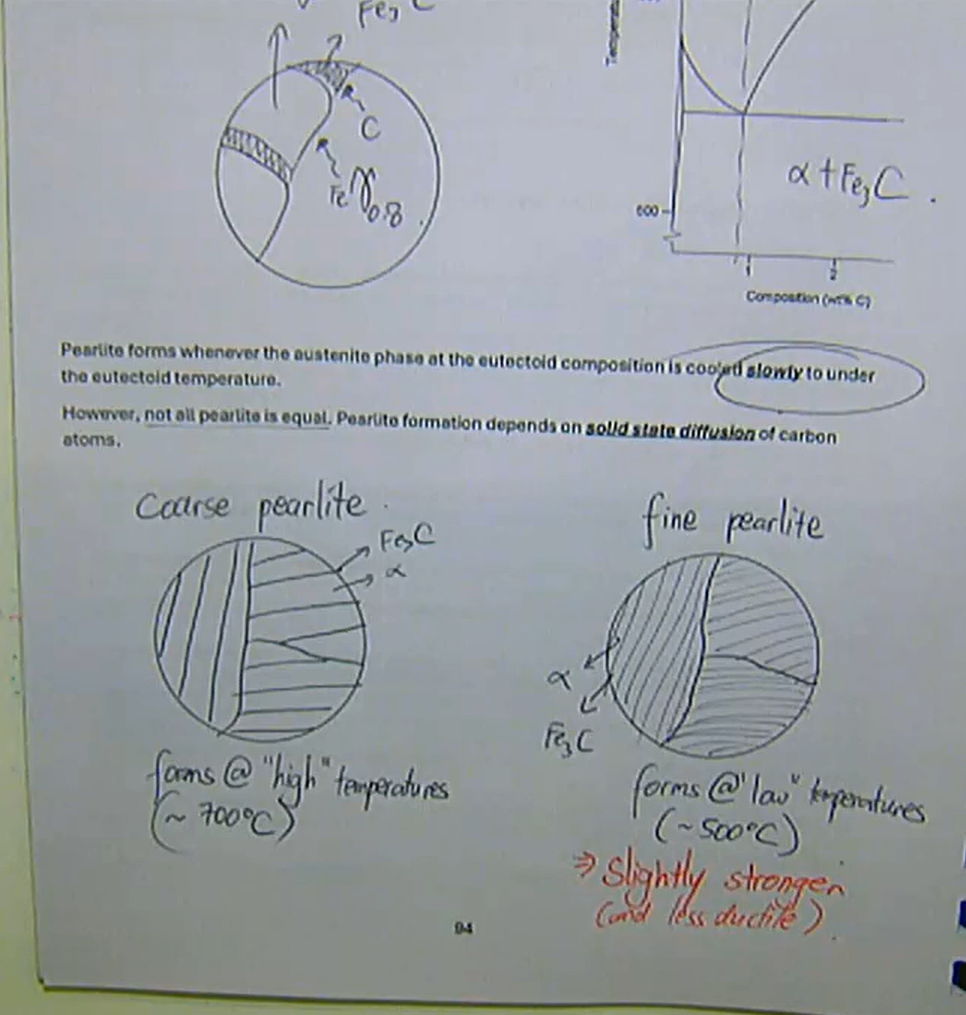

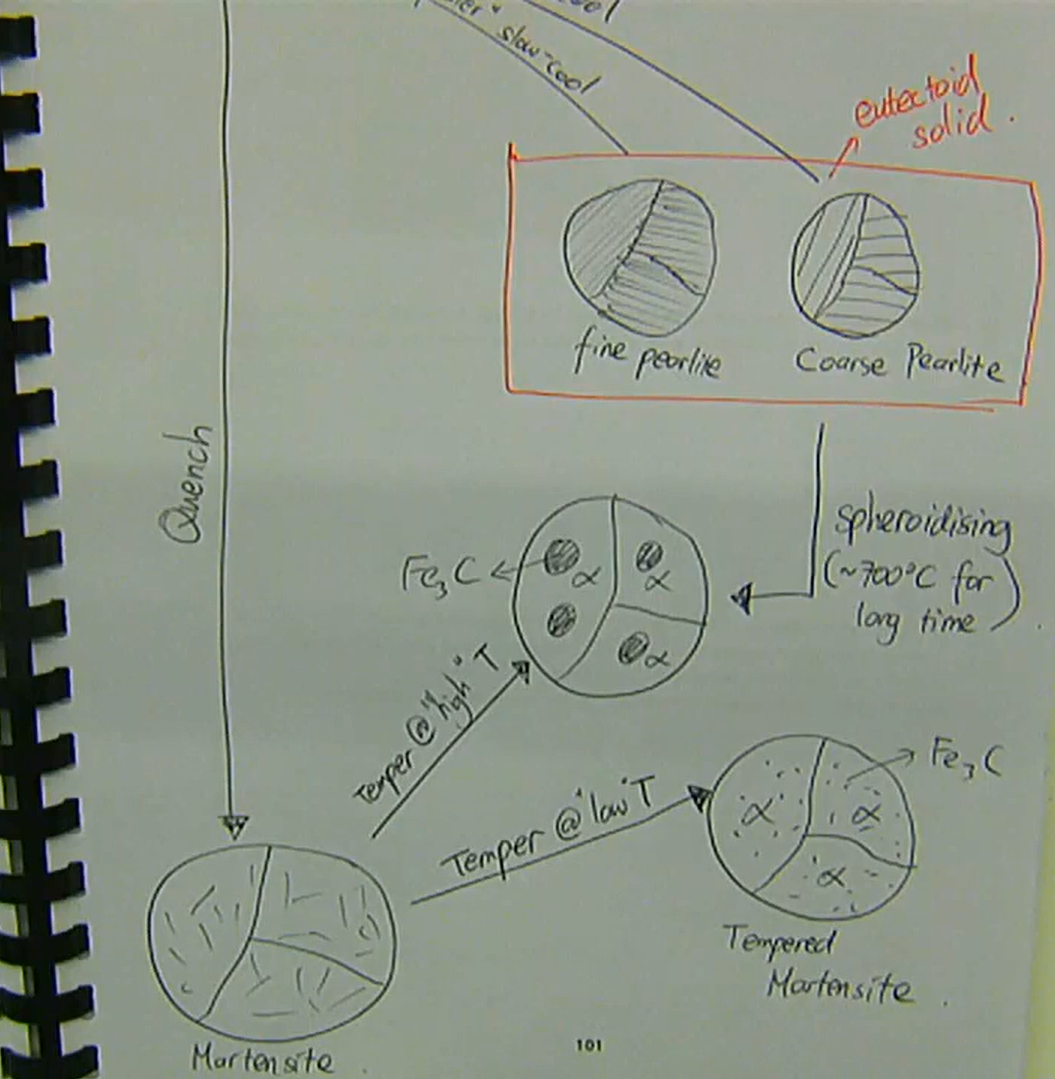

to get the layered structure required for effective multiphase strengthening in steels, recall the eutectoid transformation:

γ0.8 = α + Fe3Cpearlite forms whenever the austenite phase at the eutectoid composition is cooled slowly to under the eutectoid temperature

however, not all pearlite is equal pearlite formation depends on solid-state diffusion of carbon atoms

coarse pearlite:

forms at ‘high’ temperatures: ~700 degrees

fine pearlite:

slightly stronger (and less ductile)

forms at ‘low’ temperatures: ~500 degrees

Pearlite

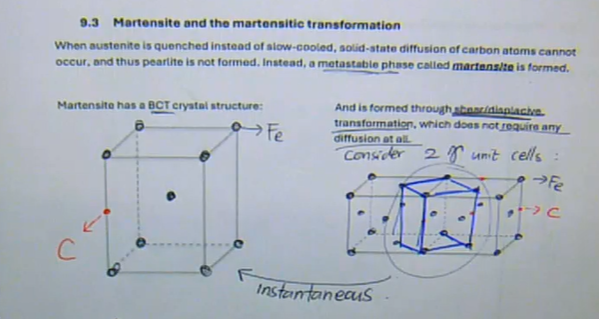

when austenite is quenched instead of slow-cooled, solid-state diffusion of carbon atoms cannot occur, and thus pearlite is not formed. Instead, a metastable phase called martensite is formed

martensite has a BCT crystal structure and is formed through shear/displacive transformation, which does not require any diffusion at all → this transformation is instantaneous

three facts about martensite:

it is a supersaturated solid solution of carbon in atom

at RT → α should have 0%

BCT → no slip systems → hard and brittle

it is a metastable structure

not on the Fe-C phase diagram

will transform into α + Fe3C IF solid state diffusion is allowed

the hardness of martensite increases with the carbon content of the steel

solid solution strengthening

more C → more lattice distortion

Martensite and the martensitic transformation

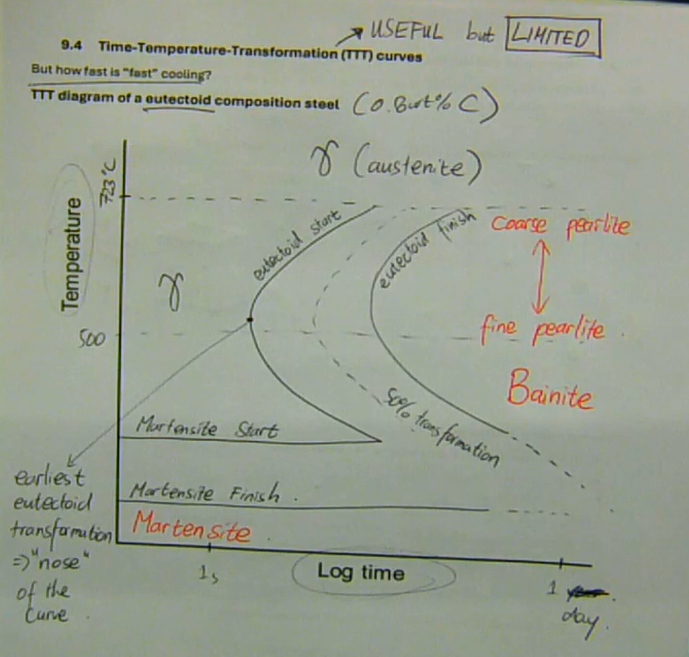

TTT diagrams are useful, but limited, because they only make sense for isothermal (constant temperature) heat treatments

Time-Temperature-Transformation (TTT) curves

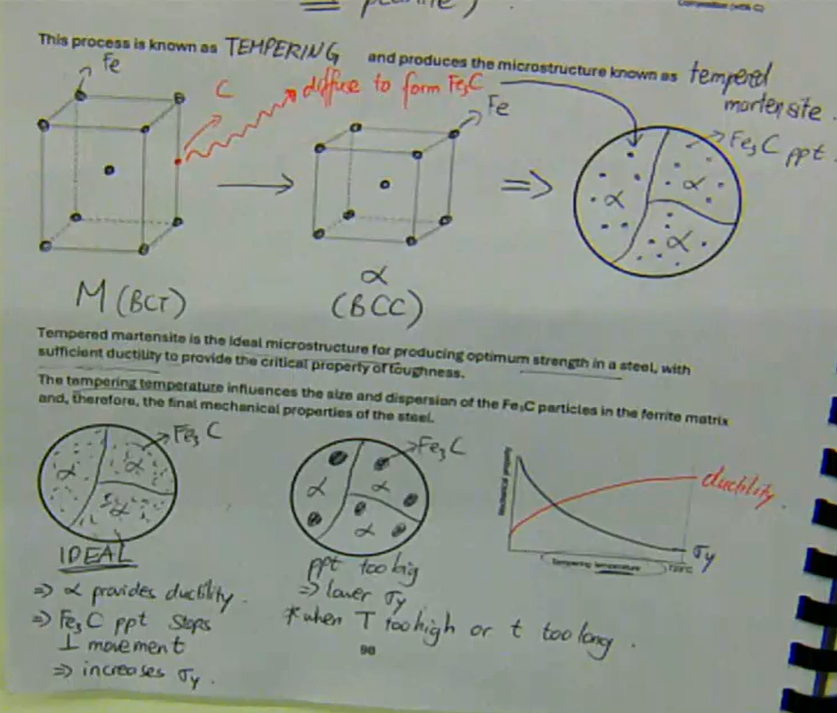

martensite has a BCT structure with no slip systems, which means it is very hard and strong, but extremely brittle

however, martensite is also a metastable phase, it does not appear on the Fe-C phase diagram

will form α + Fe3C if solid state diffusion is allowed

what equilibrium phase should there be under eutectoid temperature:

M (BCT) → α + Fe3C (not pearlite)

this process is known as tempering and produces the microstructure known as tempered martensite

tempered martensite is the ideal microstructure for producing optimum strength in a steel, with sufficient ductility to provide the critical property of toughness

the tempering temperature influences the size and dispersion of the Fe3C particles in the ferrite matrix and, therefore, the final mechanical properties of the steel

Tempered martensite

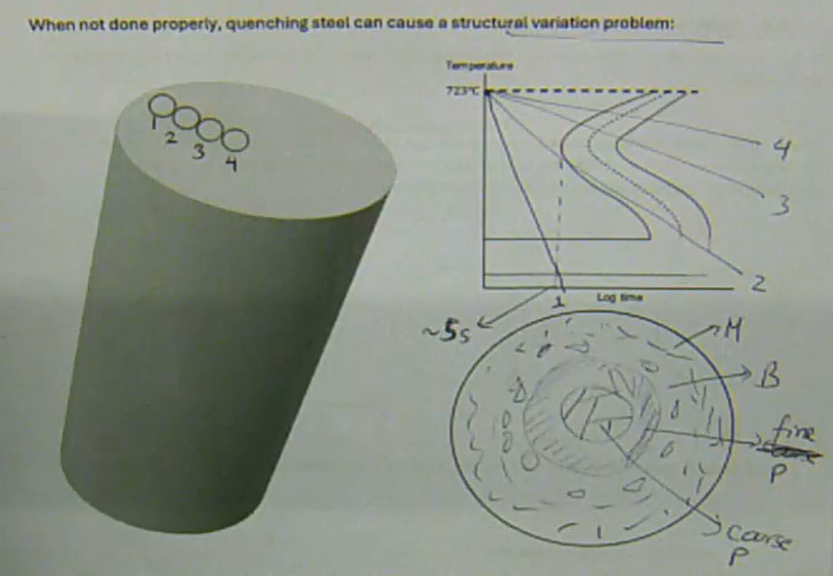

when tempering is not done properly, quenching steel can cause a structural variation problem

certain areas get cooled faster than others → leads to non-uniform microstructures and mechanical properties, as well as the formation of highly stressed and brittle martensite, which can cause cracking and distortion. Improper quenching can also result in quenching defects such as oxidation, decarburization, and insufficient or uneven hardness across the material

how can quenching steel cause a structural variation problem

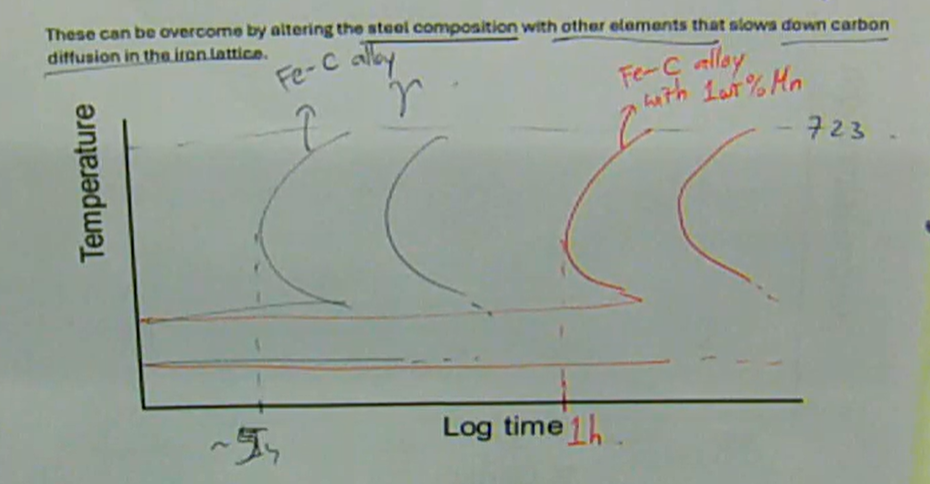

these can be overcome by altering the steel composition with other elements that slows down carbon diffusion in the iron lattice

how can the quenching of steel be avoided when tempering

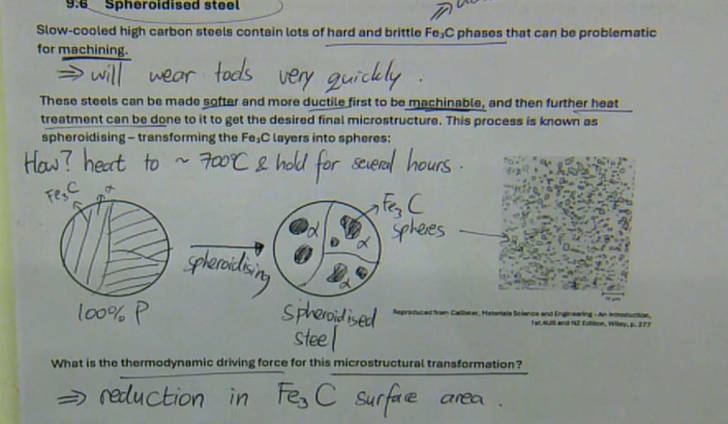

slow-cooled high carbon steel contains lots of hard and brittle Fe3C phases that can be problematic for machining

will wear tools very quickly

these steels can be made softer and more ductile first to be machinable, and then further heat treatment can be done to it to get the desired final microstructure

this process is known as spheroidising - transforming the Fe3C layers into spheres:

heat to ~700 degrees and hold for several hours

100% P → spheroidised steel (made up of Fe3C within α)

the thermodynamic driving force for this microstructural transformation is a reduction in Fe3C surface area

spheroidised steel

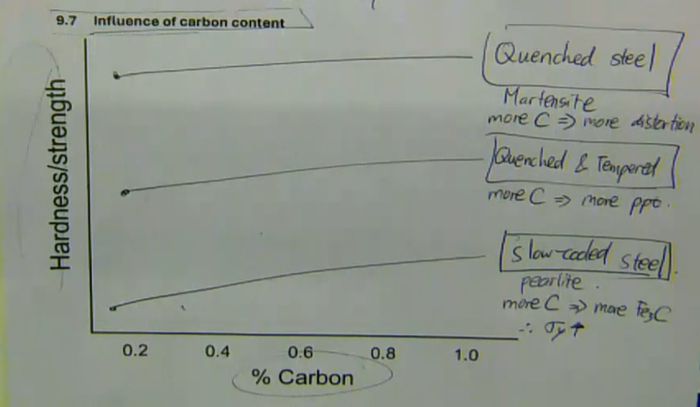

quenched steel:

Martensite

more C → more distortion

quenched and tempered:

more C → more ppt

slow-cooled steel:

pearlite

more C → more Fe3C therefore σy

influence of carbon content

γ → austenite → FCC → weak and ductile

slow-cooling γ:

→ coarse pearlite (eutectic solid)‘faster’ slow-cool:

→ fine pearlitequenching γ:

→ martensite → very hard and brittletempering martensite at low temperature:

→ tempered martensite (α + Fe3C)tempering martensite at high temperature:

→ α + Fe3C with larger Fe3C → also formed from spheroidising pearlite at ~700 degrees for a long time

summary of transformations in steel