7 minute Presentation History

1/11

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

12 Terms

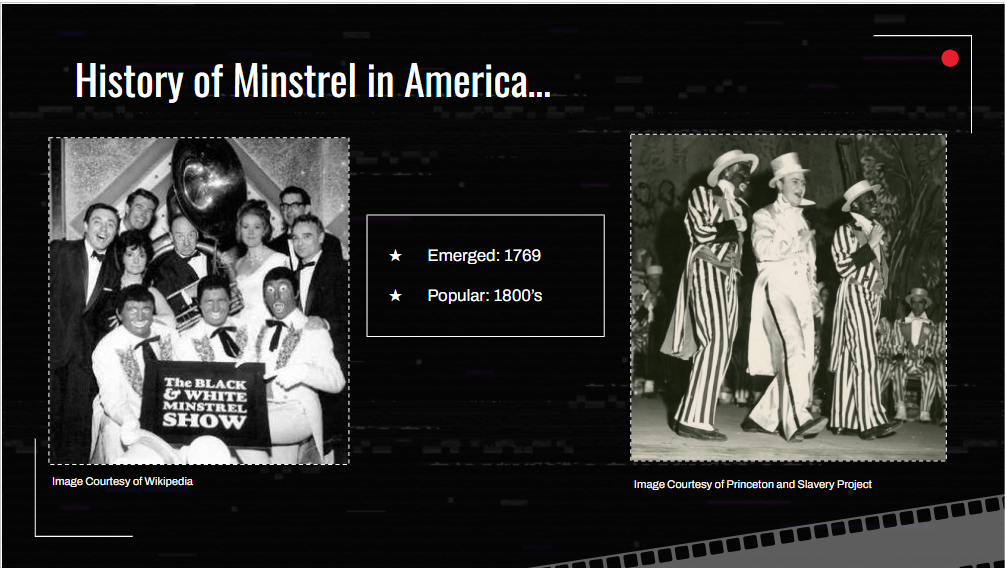

Representation of Black people in early American entertainment began with minstrel shows, which emerged around 1769 and became extremely popular in the 1830s. This form of entertainment dominated the nation and in these shows, white performers in blackface with exaggerated Black features and behavior, created distorted and racist portrayals.

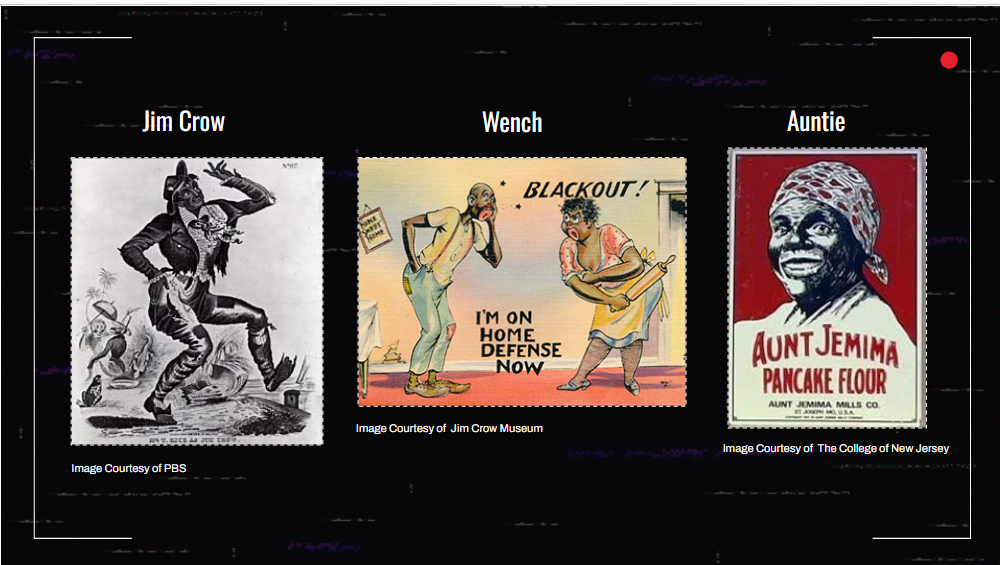

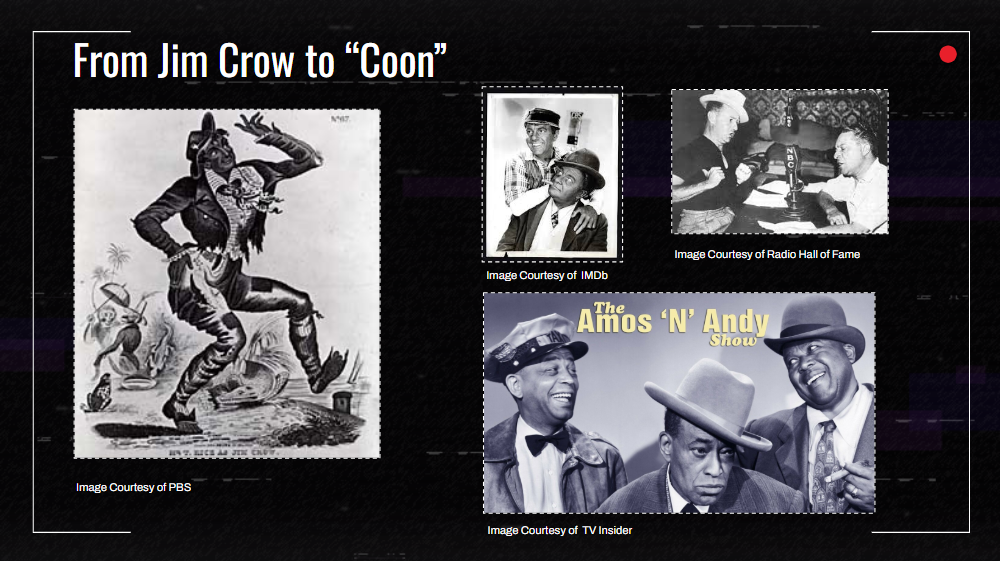

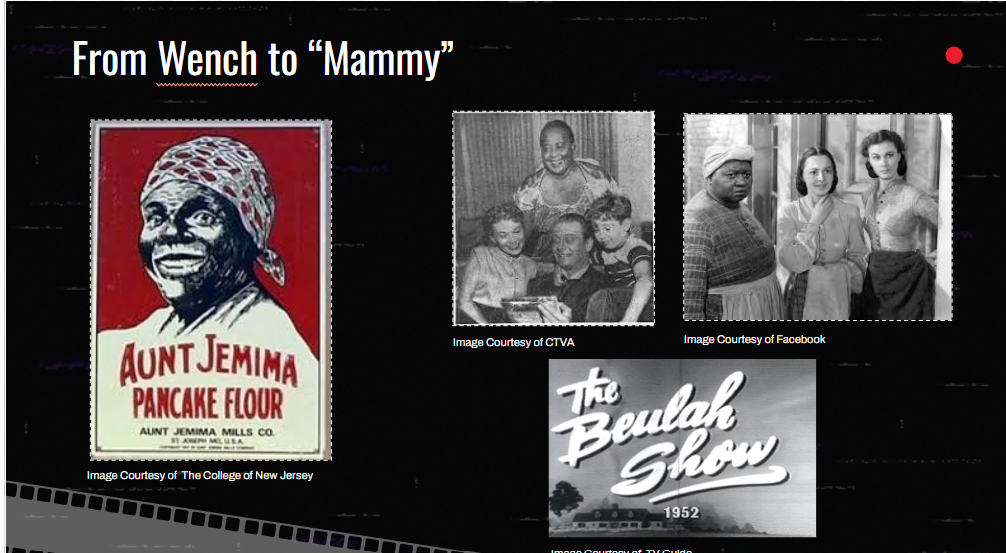

One of the most prominent minstrel characters was Jim Crow, created by Thomas Rice in 1820 after he claimed to imitate the dance and mannerisms of an enslaved Black man. Jim Crow was portrayed as ignorant, foolish, lazy, and unintelligent. Minstrels also featured the “wench,” a caricature of a Black woman depicted as loud, bossy, angry, and argumentative. Another common figure was the “Auntie,” a dark-skinned, deeply subservient Black woman who happily served solely white families and their children.

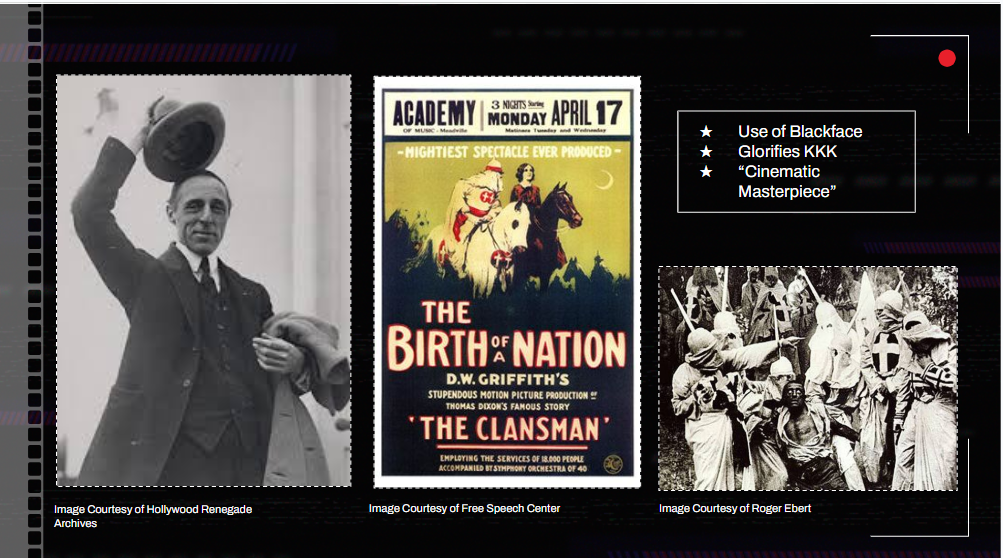

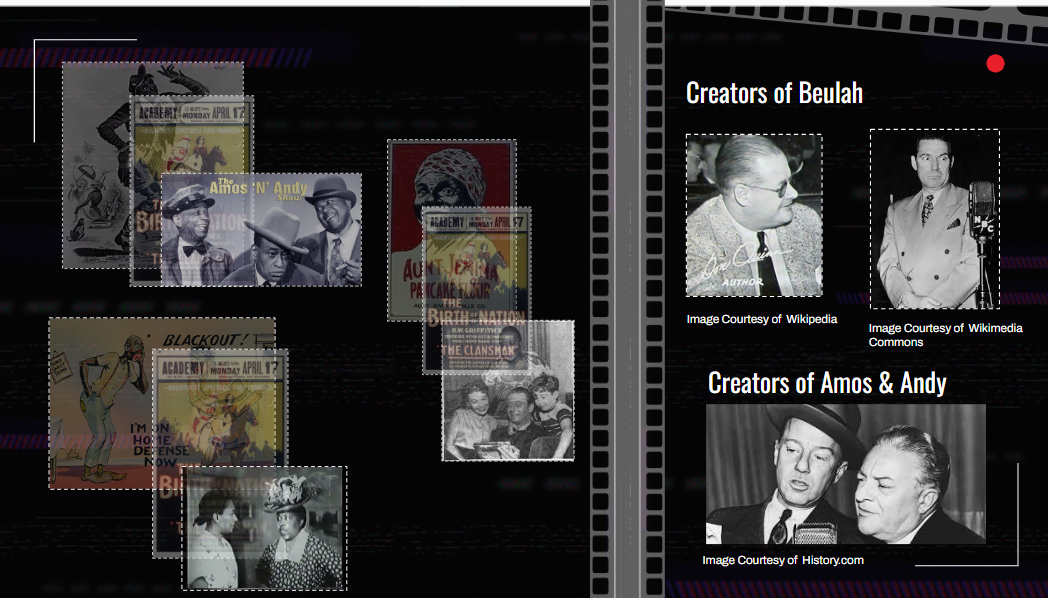

All three of these caricatures appeared in the first major motion picture to use blackface and glorify the KKK: The Birth of a Nation by D.W Griffith. Made in 1915. It was the first film screened at the White House and was celebrated by white Americans as a cinematic masterpiece, setting the stage for many films and television portrayals that followed.

Racist imagery rooted in minstrel shows and early film evolved into TV stereotypes like the coon, mammy, and angry Black woman. Yet the increasing presence of Black writers, directors, actors, and producers began to challenge and dismantle these portrayals.

As time passed, Black people became slightly more integrated into the entertainment industry. Although physical blackface declined, the stereotypes from the minstrel era persisted.

This is evident in Amos and Andy, where before when it was on radio it was voiced by white men using exaggerated dialect, while the TV version featured Black actors in 1947.

The show centered on characters who relied on white authority figures to solve simple problems, avoided work, and spoke in heavily caricatured dialect. Amos and Andy clearly descended from the Jim Crow caricature, reinforcing stereotypes that Black people were incompetent, unintelligent, and lazy, otherwise summed up as the coon stereotype.

Another major character, Sapphire Stevens, was always angry and constantly yelled at husband. Her character lacked emotional depth due to her exaggerated aggression. Her portrayal created and popularized the “Sapphire” stereotype—what we now recognize as the “Angry Black Woman.” This trope suggested that Black women were inherently hostile and aggressive. This can be directly traced back to the “wench” stereotype from minstrel shows.

The Beulah Show reinforced the mammy stereotype. Beulah was a cheerful, devoted Black maid who served a white family. She acted as their emotional backbone, existed only to solve their problems, and she had no life beyond the household, making her a direct continuation of the "auntie" caricature from minstrel shows.

Even though more Black characters began appearing on TV, representation alone didn’t guarantee progress. Behind the scenes we have directors of these shows and writers of these Black characters (who were bymajority white).

These directors and writers were using their creative freedom to keep their Black characters in this rigid box of these stereotypes inherited from minstrel shows. Those harmful stereotypes made Hollywood a lot of money because this is what people enjoyed to see.

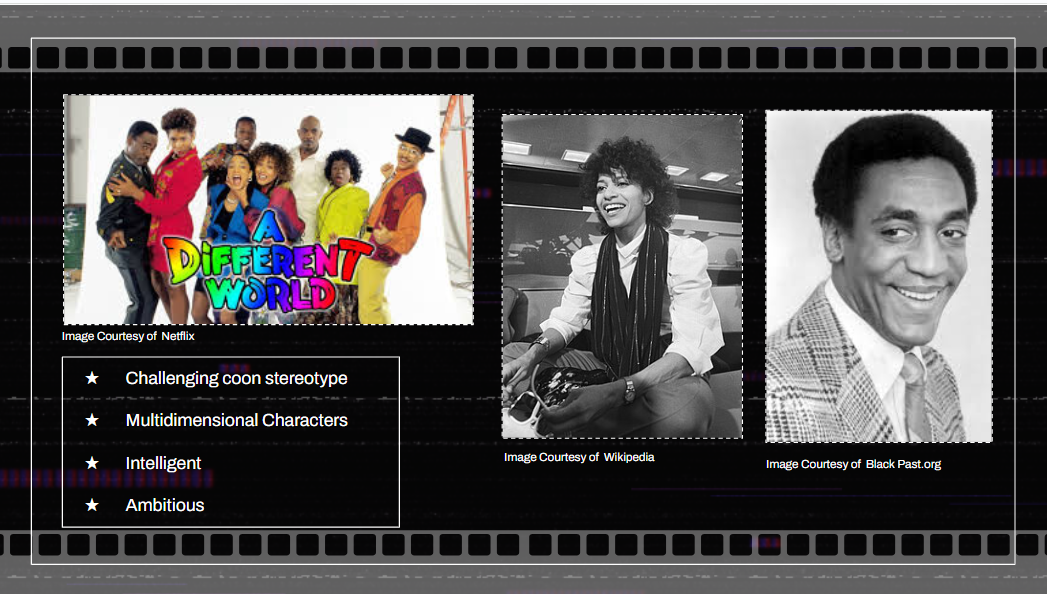

The constant misrepresentation of Black people on TV meant that more Black writers and directors were needed to control the narrative. This became possible in the 80s and 90s, thanks to breakthroughs by Black high-visibility film makers like Bill Cosby with the Bill Cosby show. Which showed an upper-middle class family and also displayed Black cultural pride without stereotypes.

This also became possible due to independent film networks that made it easier for Black directors and writers to get their films produced and viewed outside old studio gatekeepers. Which led to 7 films directed by AA directors in 1990 and that number rising to 12 by 1992. There was also a “Black sitcom explosion” where there were 15 primetime Black sitcoms by 1997.

Networks began producing more Black-led shows such as A Different World directed by Debbie Allan and created by Bill Cosby ( since it was a spin off of the Bill cosby show). A different world is a sitcom from 1987 and it challenged the coon stereotype by portraying Black college students who were intelligent, ambitious, and multidimensional. Instead of lazy or foolish caricatures, especially with the show being set in an HBCU.

As more Black creatives gained influence in TV during the late 20th century, their impact eventually extended into film, leading to groundbreaking works like Black Panther in 2018 directed by Ryan Coogler.

Black Panther challenges the “angry Black woman” stereotype by portraying Black women as strong, and purposeful rather than irrationally hostile. Their power is grounded in discipline, justice, and leadership not caricatured anger.

The film overturns the mammy stereotype by depicting Black women as leaders, innovators, and warriors with their own agency and identities—not as self-sacrificing caretakers that only exist to serve white families.

This evolution proves that authentic Black voices are essential to changing how Black stories are told, especially beyond the coon, mammy, and angry black woman stereotypes.