PYB203 Exam Revision

1/171

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

172 Terms

Developmental psychology

The field of study that explores patterns of stability, continuity, growth and change that occur throughout a person’s life.

Domains of development

Physical - The growth of the body and its organs, the functioning of physiological systems including the brain, physical signs of ageing, changes in motor abilities etc.

Cognitive - Changes and continuities in perception, language, learning, memory, problem solving and other mental processes.

Psychosocial - Changes and continuities in personal and interpersonal aspects such as motives, emotion, personality traits, interpersonal skills, relationships and roles played in the family and in society.

Nature vs nurture

Nature: biogenetic and hereditary influences

Nurture: environment influences (relationships, culture)

Maturation vs experience

Maturation: developmental changes that occur over time (due to biology) regardless of experiences

Experience: developmental changes related to specific experiences

Continuity vs discontinuity

Continuity: gradual development, with change happening in increments over time.

E.g., at age 2 years a child cries when their mother leaves a room, but by age 25 years they can go a week without a phone call.

Discontinuity: development occurs in distinct stages or steps, with each stage bringing different behaviours and qualities than previous stages.

E.g., butterfly to a caterpillar.

Active vs passive

Active: individuals are active agents in their own development, seeking out opportunities to grow, learn, and master increasingly difficult tasks.

Passive: development occurs through events in the environment that require individuals to respond, leading to changes in behaviour.

Universal vs specific - development experiences

Universal: a general trend/pattern of development that is applicable to all individuals and groups.

Specific: patterns of development are specific to a particular context or setting (e.g., individual experiences or cultural circumstances)

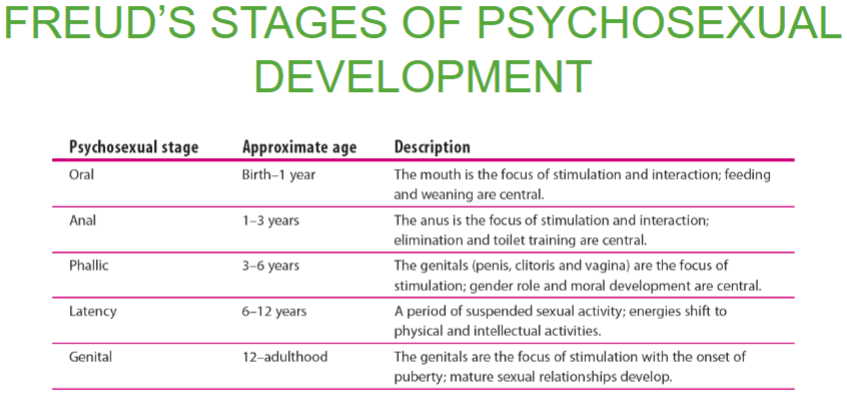

Frued’s personality structures

People are driven by motives and emotional conflicts of which they are largely unaware

People’s lives are shaped by their earliest experiences

Three personality structures:

Id: unconscious, selfish instincts and biological needs and desires (pleasure principle)

Ego: reality and problem solving, learning how to redirect desire for instant satisfaction to realistic pursuits (reality principle)

Superego: conscience, and sense of right and wrong

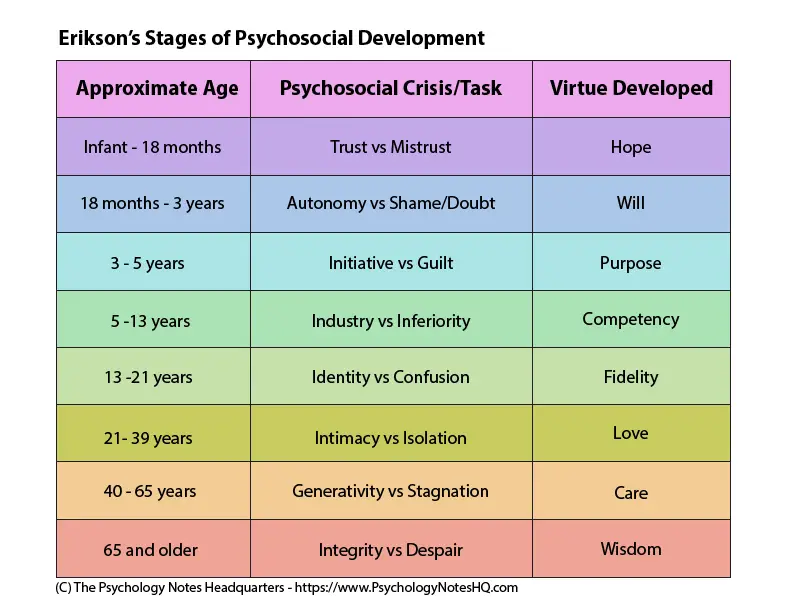

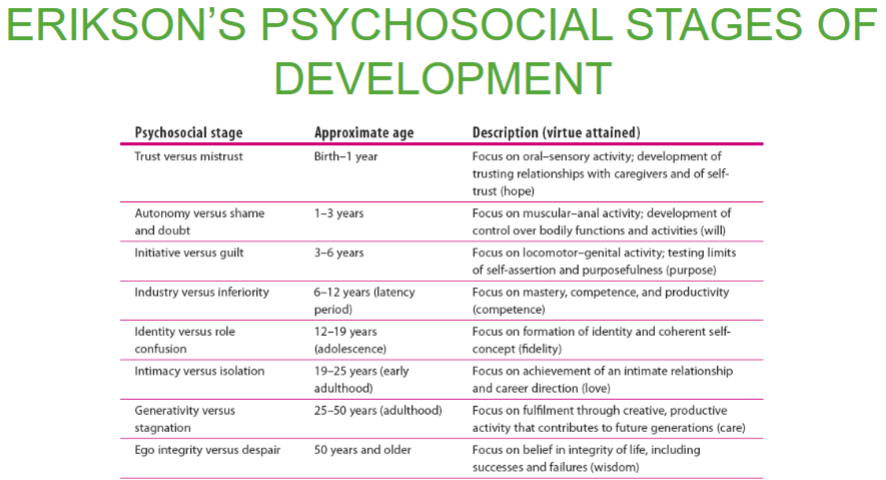

Erikson's psychological stages of development

Proposes that dialectical conflicts are the mechanisms for growth

Emphasis on social influences, such as peers, family, school etc.

Emphasis on rational and active resolution of conflicts

People emerge from each crisis/conflict “with an increased sense of inner unity, with an increase of good judgement, and an increase in the capacity to do well”

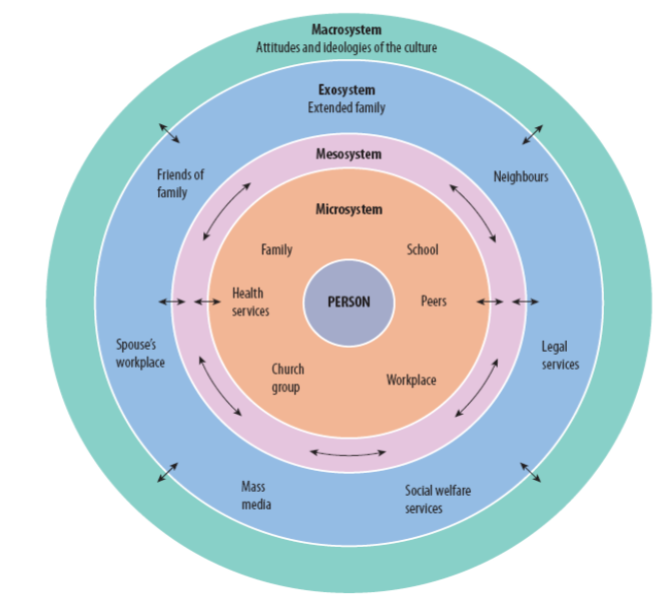

Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005)

Views development as a process of reciprocal, patterned interactions between the individual and their physical and social environment.

Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological systems theory proposed four interacting and overlapping contextual levels:

Microsystem: Face-to-face interactions

Mesosystem: Connections between microsystems

Exosystem: Indirect influences

Macrosystem: General aspects of society

Chronosystem – encompasses time and the critical life and historical events that also influence development.

This model was later amended to the bioecological systems theory to encompass the individual and their biology and physical growth.

Classical conditioning - Ivan Pavlov (1849 -1936)

Unconditioned stimulus/unconditioned response

Neutral stimulus paired with unconditioned stimulus

Neutral stimulus --> Conditioned stimulus

Conditioned stimulus/unconditioned response

Reflex learning

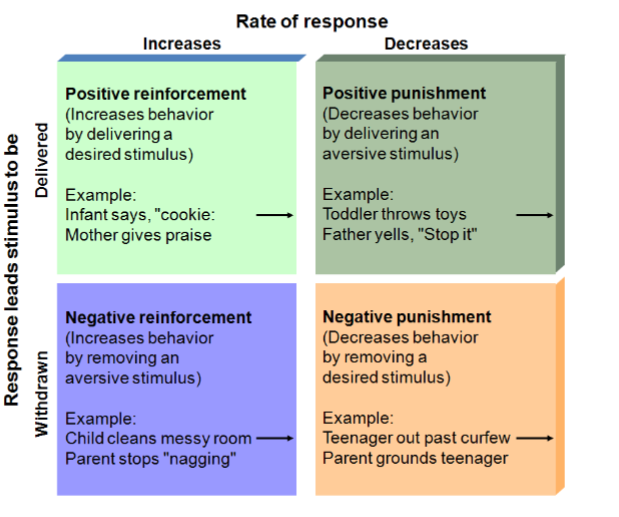

Operant Conditioning - B. F. Skinner (1904 - 1991)

Reinforcement strengthens response

Punishment weakens response

Positive: addition

Negative: withdrawal

Social Learning Theory - Albert Bandura (1925- 2021)

Learn through modelling: observing others doing something

Then imitate the modelled behaviour

Can observe the rewards or consequences associated with behaviours

Can also learn not to do something (e.g., child watching others falling in the playground might deter them from doing the same thing)

Cognitive Development - Jean Piaget (1896 - 1980)

Children actively construct new understandings of the world based on their experiences

Four discrete stages of thought

Sensorimotor operation stage

Pre-operational stage

Concrete operational stage

Formal operational stage

Assimilation: fitting new information into existing cognitive structures or schema.

Accommodation: when assimilation doesn’t work, new schemas are formed.

Adaptation: when existing schemas are deepened or strengthened through processes of assimilation or accommodation.

Vygotsky's zone of proximal development

Cultural nature of human development

Culture as a tool ‘within’ a person

Social interaction drives cognitive development

Scaffolding: the framework of support and assistance provided by others (e.g., teachers,

parents, peers)With this scaffolding, support can be gradually reduced

Bronfrenbrenners bioecological systems theory

Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development

Frueds stages of psychosexual development

Operant conditioning

Theory vs research

Theory

A ‘theoretical’ framework aiming to explain human development

Incorporates many ‘assumptions’

Help guide research and practice.

Micro-theory: narrow scope

Macro-theory: encompass large fields of development.

Research

• Collect data to test and refine theories and hypotheses (predictions)

• Derive concrete observations/findings.

• Help guide future research, practice, and policy.

Methods of developmental research

Case study, naturalist observation, experiments, self-report assessments

Case study

In-depth focus on one individual, group, or event

Aim is to fully understand that experience by compiling a complete picture

Naturalistic Observations

Observing the normal habits of an individual/group in a natural setting

Goal is to limit the researcher intrusion

Increases the real-life validity, but is open to subjectivity and interpretation

Often require two observers to check the accuracy and objectivity of the collected data

Experiments

• Aim is to test causal hypotheses by systematically manipulating one variable at a time

• Impose a tight level of control over the testing environment and any factors that could influence behaviour

• However, these controls could mean findings aren’t generalisable (applicable) to the real world

Self-report Assessment

Individuals report on their own experience or perspectives

Often via interviews or surveys

Allows us to get an insight into functioning or experiences that are difficult to observe (e.g., personality)

Open to reporting bias; requires a level of insight into behaviours; relies on recall

For self-report data in particular, a multi-informant approach is often the best, including from child, caregivers, teachers etc.

Assessments

Assessment with examples

Include a standardised assessment of functioning or performance

Establishes a standardised and objective approach

Quality of test relies on the quality of the items and whether they work equally well for all individuals (diverse backgrounds)

Examples

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC)

• National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN)

• Birth weight

• Mental State Examination

Correlation studies

Looks at the relationship between two or more variables, but doesn’t manipulate these variables, doesn’t permit causal inferences but sometimes is the only way to research something. Cross-sectional, longitudinal & cross-sequential.

Cross-sectional study

Studies a group of participants at one point in time.

Advantages:

Can examine differences between participants

Can examine differences according to age OR explore one particular age/stage in-depth

Cost-effective and time efficient

Disadvantages:

Can’t distinguish between age effects (variation in experiences due to chronological age) and cohort effects (social and historical changes affecting a specific group with a shared event)

Can explore associations between variables (e.g., personality and mental health) but only at one time.

Difficult to infer cause and effect

Longitudinal study

Studies the same group of participants over multiple time-points.

Advantages:Study developmental trajectories over time

Can explore how early experiences (predictors) relate to later development (outcomes)

Disadvantages:

Expensive (time and resource intensive)

Attrition (drop-out over time)

Cross-sequential study

Combines cross-sectional and longitudinal research. Multiple groups followed across multiple time points.

Allows investigation of development among individuals over time.

Allows investigation of differences in development between groups of different ages.

What is Infancy

A period of rapid growth and development in a range of areas:

Physical, Perceptual, Cognitive, Language, Social and Emotional

Infant Motor Development- Newborn Reflexes

Reflexes are unlearned, involuntary responses to stimuli

Survival reflexes are adaptive. E.g. breathing, eye-blink, sucking

Primitive reflexes are less adaptive and typically disappear in early infancy. E.g. Babinski reflex, grasping reflex

Motor skill types & how they’re developed

Motor development follows two trends:

Cephalocaudal - pattern of development in humans that occurs from the head down to the feet.

Proximodistal - growth pattern in which development radiates from the center of the body outward.

Gross motor skills - Movement of large muscles of arms, legs, and torso

Fine motor skills - Movement of small muscles such as fingers, toes

Habituation

The process of learning to be bored with a stimulus

After repeated presentation with the same visual stimulus, the infant becomes bored and looks away

If a different stimulus is presented and the infant regains interest, researchers conclude that the infant has discriminated between the two stimuli

Preferential looking

A method used to assess infant perception by presenting two visual stimuli and measuring which one the infant looks at longer. If an infant consistently looks at one stimulus more, it suggests they can perceive a difference and have a preference.

Evoked potentials

Researchers can assess how an infant’s brain responds to stimulation by measuring its electrical conductivity

Infant - Operant conditioning

Infants can learn to respond to a stimulus (to suck faster or slower or to turn the head) if they are reinforced for the response

Infants: Vision

At birth, infants have vision, but lack acuity

Can see more clearly about 20 – 25cm

Objects at 6 metres as distinct as objects at 180 metres for adults

Improves steadily during infancy

Attracted to patterns that have light-dark transitions, or contour

Attracted to displays that are dynamic rather than static

Young infants prefer to look at whatever they can see well

Around 2 or 3 months, a breakthrough begins to occur in the perception of forms

Depth perception in infants

Gibson and Walk (1960): Classic study to examine depth perception in infants using the visual cliff

Infants can perceive the cliff by 2 months (tend to be curious rather than fearful)

Hearing

Basic capacities are present at birth

Can hear better than they can see

Can localise sounds

Can be startled by loud noises

Can turn toward soft sounds

Prefer relatively complex auditory stimuli

Can discriminate among sounds that differ in loudness, duration, direction, and frequency/pitch

Early development

Sensory experience is vital in determining the organisation of the developing brain

The visual system requires stimulation early in life to develop normally

Early visual deficits (i.e., congenital cataracts) can affect later visual perception

Exposure to auditory stimulation early in life affects the architecture of the developing brain and influences auditory perception skills

Infant Cognition- Piaget’s Sensorimotor Stage

The world is understood through the senses and actions

The dominant cognitive structures are the behavioural schemes that develop through coordination of sensory information and motor responses

Substages of the Sensorimotor Stage

Reflexes: (first month)

Reflexive reaction to internal and external stimulation

Primary circular reactions: (1-4 months)

Infants repeat actions relating to their own bodies

Secondary circular reactions: (4-8 months)

Repetitive actions involving something in the infant’s external environment

Coordination of secondary schemes: (8-12 months)

Secondary actions are coordinated in order to achieve simple goals (i.e., pushing or grasping)

Tertiary circular reactions: (12-18 months)

Experimentation; actions are repeated with variations

Beginning of thought : (18 months)

Symbolic thought permits mental representation, imitation, and recall

The Development of Object Permanence

Object permanence develops during the sensorimotor period

From 4-8 months, “out of sight, out of mind”

By 8-12 months, make the A-not-B error

By 1 year, A-not-B error is overcome, but continued trouble with invisible displacement

By 18 months, object permanence is mastered

Research suggests that infants may develop at least some understanding of object permanence far earlier than Piaget believed.

By 3 months, infants appear to understand that objects have qualities that should permit them to be visible when nothing obstructs them

Emotions

Earliest emotion – crying

Hunger, anger, pain, fussiness

Other emotions

Joy and laughter, 3 - 4 months

Wariness, 3 - 4 months

Surprise, 4 months

Fear, 5 - 8 months

More complex emotions in toddlerhood

Infants: Self

Infants develop an implicit sense of self through their perceptions of their bodies and actions

In the first 2 or 3 months, infants discover they can cause things to happen

After 6 months, infants realise they and other people are separate beings with different perspectives, ones that can be shared

Around 18 months, infants recognise themselves visually as distinct individuals - Lewis and Brooks-Gunn (1979): Mirror test

Attachment

A strong and enduring emotional bond that develops between an infant and a caregiver during the infant’s first years of life

Characterised by reciprocal affection and a shared desire to maintain physical and emotional closeness

Psychoanalytic - I love you because you feed me

Learning - I love you because you are reinforcing

Cognitive - I love you because I know you

Ethological - I love you because I was born to love

Key figures in attachment theory:

John Bowlby (1907-1990)

Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999)

Piaget’s Theory & Core Concepts

Children actively construct new understandings of the world based on their experiences

Schemes are mental structures or frameworks that help children organize and interpret information (e.g., a baby’s grasping scheme for holding objects).

Assimilation is when a child fits new information into existing schemes (e.g., calling all four-legged animals "dog").

Accommodation is when a child changes or creates new schemes to fit new information (e.g., learning that a cat is different from a dog and adjusting their understanding).

Piaget’s Sensorimotor Stage

Infant - 2

The world is understood through the senses and actions

The dominant cognitive structures are the behavioural schemes that develop through coordination of sensory information and motor responses

Goal-directed behaviour/intentionality

Symbolic thought/representations

Infants move from understanding the world through senses and actions toward understanding through symbolic thought

Become capable of mental representations

Mental imagery - Internal representation of an external event

Language - Not just a communication system, but a means of representing objects and events in an abstract way

Symbolic play – Pretending

Play

The first pretend play emerges early in the second year – Play in which one actor, object, or action symbolises or stands for another

In the earliest pretend play, the infant performs actions that symbolise familiar activities such as eating, sleeping, and washing

Between the ages of 2 and 5, pretend play increases in frequency and in sophistication

Inverted U shape: nonexistent around 15 months, peaks around 5-7 years before decreasing

Social pretend play is universal - The content of play is influenced by culture

Social pretend play emerges around 3 – 4 years, or earlier in the context of a more proficient partner such as an older sibling, mother, or father.

Cognitive skills developed from pretend play

Social referencing

Using another person’s response to an ambiguous situation as a guide for one’s own response

Decentration

Reading intentionality in others

The Development of Intentionality

Seeing oneself (and others) as intentional agents is one of the most basic elements of cognition in social contexts

Intentionality underpins more complex social cognition such as Theory of Mind

Piaget’s Pre-operational Stage

2-7

Symbolic representations and capacity:

Language

Pretend play

• Can include imaginary companions

Can refer to the past and future

Object permanence

A focus on perceptual salience – the most obvious features of an object or a situation – means that preschoolers can be fooled by appearance

They may also have difficulty with tasks that require logic

Reliance on perceptions and lack of logical thought means that children have difficulty with conservation - the idea that certain properties of an object or substance do not change when its appearance is altered in a superficial way

Cognitive limitations of pre-operational stage

Centration -Focusing on one aspect of a problem or object

Irreversible thought - Cannot mentally undo an action

Static thought - Focusing on the end state rather than the changes that transform one state into another

Difficulty with classification - Using criteria to sort objects on the basis of characteristics such as shape, color, function

Lack class inclusion, the ability to relate the whole class (furry animals) to its subclasses (dogs, cats)

Egocentrism

Theory of Mind

The ability to attribute mental states— beliefs, intents, desires, pretending, knowledge—to oneself and others and to understand that others have beliefs, desires and intentions that are different from one's own.

Develops around age 4–5 in children

Crucial for empathy, social interaction, and predicting others’ behavior

Early development of social cognition in infants

Intentionality: Infants recognize that others act with purpose (e.g., reaching for a toy on purpose, not by accident).

Perspective-taking: Begins in infancy and develops over time; understanding that others can have different views or knowledge.

Joint attention: Around 9 months, infants share focus with others by following gaze or pointing.

By 12 months: Infants point to inform others (not just to request).

By 18 months: Infants distinguish between intentional and accidental actions.

Piaget’s Concrete Operations Stage

7-11

In middle childhood, children move from preoperational to concrete operational stage

Non-conserving, transitional, conserving

Demonstrate the ability to perform operations

Mental actions on concrete situations/objects

Decentration

Can focus on two or more dimensions of a problem at once

Reversibility of thought

Can mentally reverse or undo an action

Transformational thought

Can understand the process of change from one state to another

In this stage we see a shift from understanding being driven by perceptual salience to logical reasoning

Seriation

The ability to arrange items mentally along a quantifiable dimension such as weight or height

Transitivity

The understanding of relationships among elements in a series

Less egocentrism

Classification abilities improve

Can classify objects by multiple dimensions and can grasp class inclusion

Piaget’s Formal Operations Stage: Adolescents

This takes place gradually over years

Formal operations are mental actions on ideas

They permit systematic and scientific thinking about problems, hypothetical ideas, and abstract concepts

Piaget’s pendulum task

The postformal stage

Some researchers have postulated a fifth stage of cognitive development- the postformal stage (e.g., Commons and Bresette, 2006)

In postformal thinking, decisions are made based on situations and circumstances, and logic is integrated with emotion as adults develop principles that depend on contexts.

Limitations of Piaget’s Theory

The timing of stage progressions is more variable than Piaget proposed.

Piaget was more likely describing children’s performance (what a child usually does) rather than their competence (the limits of their abilities).

Piaget may have over-estimated some abilities:

Adults frequently fail to use formal operations in daily life.

Formal operations can be domain-specific (successfully applied in some contexts but not to others).

Cognitive-developmental approach: Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934)

Key Idea: Cognitive development is shaped by social interaction and cultural tools (e.g. language).

Learning happens first socially, then individually (internalised).

Introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Morality

Morality is a sense of behavioural conduct that differentiates intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good (or right) and bad (or wrong).

Three Components of Morality

Affective (Emotional)

Feelings around right/wrong (guilt, concern for others).

Emotions motivate moral thoughts/actions = moral affect.

Negative emotions (e.g., shame, guilt) deter bad behaviour.

Positive emotions (e.g., pride) reinforce doing good.

Empathy (feeling others' emotions) is key to moral dev.

Empathy motivates prosocial behaviour (helping, sharing, concern for others' welfare).

Cognitive

How we understand right/wrong and decide how to act = moral reasoning.

Behavioural

What we actually do in moral situations (e.g., resisting cheating, helping others) = moral behaviour.

Moral Reasoning

Cognitive developmental theorists study morality by looking at the development of moral reasoning – the thinking process involved in deciding whether an act is right or wrong

Moral reasoning is believed to progress through an invariant sequence – a fixed and universal order of stages, each of which represents a consistent way of thinking about moral issues that is different from the stage preceding or following it (Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development)

Piaget’s theory of moral development

Includes three aspects:

Premoral period

During the preschool years, children show little awareness or understanding of rules and cannot be considered moral beings

Heteronomous morality

Children 6 to 10 years old take rules seriously, believing that they are handed down by parents and other authority figures and are sacred and unalterable

They judge rule violations as wrong based on the extent of damage done, not paying much attention to whether the violator had good or bad intentions

Autonomous morality

At age 10 or 11, most children enter a final stage of moral development in which they begin to appreciate that rules are agreements between individuals – agreements that can be changed through a consensus of those individuals

In judging actions, they pay more attention to whether the person’s intentions were good or bad than to the consequences of the act

Moral Reasoning- Kohlberg

Kohlberg proposed that moral reasoning develops through a series of stages, grouped into three levels. He believed that people progress through these stages as they mature and gain life experience.

Pre-conventional (kids):

Stage 1: Avoid punishment

Stage 2: Self-interest

Conventional (teens/adults):

Stage 3: Gain approval

Stage 4: Follow rules/laws

Post-conventional (some adults):

Stage 5: Social contract/fairness

Stage 6: Universal ethics/conscience

Criticisms of Kohlberg’s theory

Scoring procedures not sufficiently objective or consistent

Content of dilemmas too narrow

Dilemmas not aligned with real-life

No distinction between moral knowledge and social conventions

Gender and culture bias

Moral behaviour according to social-learning theory

Moral behaviour is learned in the same way that other social behaviours are learned: through observational learning and reinforcement and punishment principles

Social-learning theorists believe moral behaviour is believed to be strongly influenced by the situation

Due to situational influences, what we do (moral performance) is not always reflective of our internalised values and standards (moral competence)

Attachment Theory

Foundation of the Theory:

Attachment theory is based on the idea that humans have a biological predisposition to form emotional bonds, particularly with caregivers, for survival and well-being.

John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who developed the foundational concepts of attachment theory.

Bowlby's theory draws on evolutionary psychology, suggesting that attachment behaviors, like crying for comfort or seeking proximity, are adaptive mechanisms that ensure the survival of infants.

Early Relationships Matter:

The quality of these early relationships, characterized by responsiveness, consistency, and sensitivity, significantly impacts a child's development and their ability to form healthy

relationships later in life.

Attachment Styles & influence on adult relationships

Attachment theory identifies different attachment styles, including secure, anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant, and fearful-avoidant, which are thought to emerge from early experiences with caregivers.

Mary Ainsworth is a developmental psychologist who collaborated with Bowlby and developed the "Strange Situation" method, a tool for assessing attachment styles in infants.

Influence on Adult Relationships:

Attachment styles formed in childhood can influence patterns of relating in romantic relationships, friendships, and other significant connections throughout adulthood.

The Impact of Historical Trauma on Attachment

The Stolen Generations and its impact on familial bonds and attachment.

Intergenerational trauma and its effects on attachment behaviours.

Parental trauma is linked to detachment in the next generation, where individuals tend to distance themselves from close relationships (Spiel & Bornstein, 2023)

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in parents, particularly maltreatment, are associated with behavioral problems in children, emphasising the need for interventions that address parental trauma to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma (Wang et al., 2022).

Maladaptive Coping Mechanism

Misdiagnosis weaponised against Aboriginal peoples

Mistrust in systems and services resulting in disengagement

Cultural Limitations of Attachment Theory

Attachment theory in Australian child welfare systems misrepresents Aboriginal families and children's needs, perpetuating inequities.

use of non-Indigenous constructs in child protection interventions reflects dominant cultural perceptions, causing harm to Aboriginal communities.

the mother-infant dyad, does not fully capture the communal and extended family structures prevalent in Aboriginal communities.

This theory often misrepresents Aboriginal parenting practices, leading to inappropriate child welfare interventions

The reliance on attachment theory in legal decisions concerning Indigenous children often overlooks the importance of cultural continuity and community-based caregiving systems

Protective Factors for Aboriginal Attachment

Kinship = extended family + community

➤ Core to identity and protective care for childrenCultural attachment is protective

➤ Strong community ties reduce stigma, support healthy choicesTraditional practices support development

➤ Collective child-rearing and Elders strengthen family function and resiliencePlace attachment matters

➤ Connection to land (e.g., Cherbourg) supports identity, social & cognitive growth

The Promotion of Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB)

A holistic concept that recognises connection to land, culture, spirituality, ancestry, family and community are as important for wellbeing as physical health. This concept also acknowledges the impact of past events and policies on the SEWB of individuals today.

Psychosocial development

the development of the personality, and the acquisition of social attitudes and skills, from infancy through maturity.

Key points of Mary Ainsworth Attachment Theory

It is the reunion behaviour that is the most telling

Lack of observable distress does not mean lack of underlying anxiety e.g. avoidant attachment

Formation of Internal Working Models (IWMs)

Internal Working Models are mental representations of ourselves, others, and relationships, formed through early attachment experiences (Bowlby, 1969).

Based on interactions with primary caregivers (especially in infancy). Eg, If a caregiver is responsive and consistent, the child forms a positive IWM (e.g., "I am lovable, others are trustworthy").

IWMs guide future relationships, emotional regulation, and expectations.

They’re mostly unconscious but can affect how we relate to others throughout life.

Two dimensions of PARENTING STYLES

Acceptance-responsiveness

refers to the extent to which parents are supportive, sensitive to their children’s needs, and willing to provide affection and praise when their children meet their expectations

Demandingness-control (sometimes called permissiveness- restrictiveness)

refers to how much control over decisions lies with the parent rather than with the child

Authoritarian parenting and outcomes

High demandingness-control and low acceptance-responsiveness

Parents impose many rules, expect strict obedience, rarely explain why the child should comply with rules, and often rely on power tactics such as physical punishment to gain compliance

Children of authoritarian parents tended to be moody and seemingly unhappy, easily annoyed, relatively aimless, and unpleasant to be around

Authoritative parenting and outcomes

high demandingness-control and high acceptance- responsiveness

parents set clear rules and consistently enforce them, but they also explain the rationales for their rules and restrictions, are responsive to their children’s needs and points of view, and involve their children in family decision-making

Children of authoritative parents were the best adjusted – cheerful, socially responsible, self-reliant, achievement oriented, and cooperative with adults and peers

Permissive parenting and outcomes

High in acceptance-responsiveness but low in demandingness-control

Permissive parents are indulgent with few rules and few demands

They encourage children to express their feelings and impulses and rarely exert control over their behavior

Children of permissive parents were often impulsive, aggressive, self-centered, rebellious, aimless, and low in independence and achievement

Uninvolved (Neglectful) parenting and outcomes

Low demandingness-control and low acceptance-responsiveness

They seem not to care much about their children and may even reject them

Uninvolved parents may be so overwhelmed by their own problems that they cannot devote sufficient energy to expressing love and setting and enforcing rules

Children of neglectful parents display behavioral problems such as aggression and frequent temper tantrums as early as age 3

They tend to become hostile and antisocial adolescents who abuse alcohol and drugs and get in trouble

Benefits of Only Children

Sometimes stereotyped as self-centred or spoilt, however, this is not borne out in research.

Research suggests higher in:

Self-esteem

Positive personality

Achievement motivation

Academic success

Saracho & Spodek (1998) definition of play

Intrinsically, not extrinsically motivated

Process-, not product- oriented

Creative and non-literal

Having implicit rules

Spontaneous and self-initiated

Free from major emotional distress

RELATIONSHIPS WITH PEERS

A peer is a social equal, someone who functions at a similar level of behavioral complexity, often someone of similar age

Peer relationships have developmental value

Peers help children learn that relationships are reciprocal

Peers force children to hone their social perspective-taking skills

Peers contribute to social-cognitive and moral development in ways that parents cannot

Contact with peers comes simultaneously with cognitive development including:

Major advances in language development

Major advances in perspective-taking abilities, and hence capacity for cooperative play, prosocial behaviour (and antisocial behaviour!) increases

Advances in problem-solving ability means improved capacity to tackle conflict

Sociometric measures & social status categories

Researchers study peer-group acceptance through sociometric techniques

Methods for determining who is liked and who is disliked in a group

Using sociometric techniques, children may be classified into the following categories of social status (Coie & Dodge, 1988):

Popular – well liked by most and rarely disliked

Rejected – rarely liked and often disliked

Neglected – neither liked nor disliked (isolated children who seem to be invisible to their classmates)

Controversial – liked by many but also disliked by many (the fun-loving child with leadership skills who also bullies peers and starts fights)

Average – in the middle on both the liked and disliked scales

GENDER-ROLE DEVELOPMENT

Process of learning gender-consistent behaviours.

By age 2, children recognize typical gender behaviours and start gender labelling themselves and others but don’t yet understand gender stability.

Preschoolers (4-7 years) show strong rigidity about gender stereotypes.

Rigidity decreases in primary school as gender identity firms up and thinking becomes more flexible.

Children may exaggerate gender roles to understand them better (Maccoby, 1998).

Non-conforming children may face social consequences.

The nervous system

Not a static network of interconnected elements; rather, it is a plastic (changeable), living organ that grows and changes continuously in response to its genetic programs and its interactions with the environment.

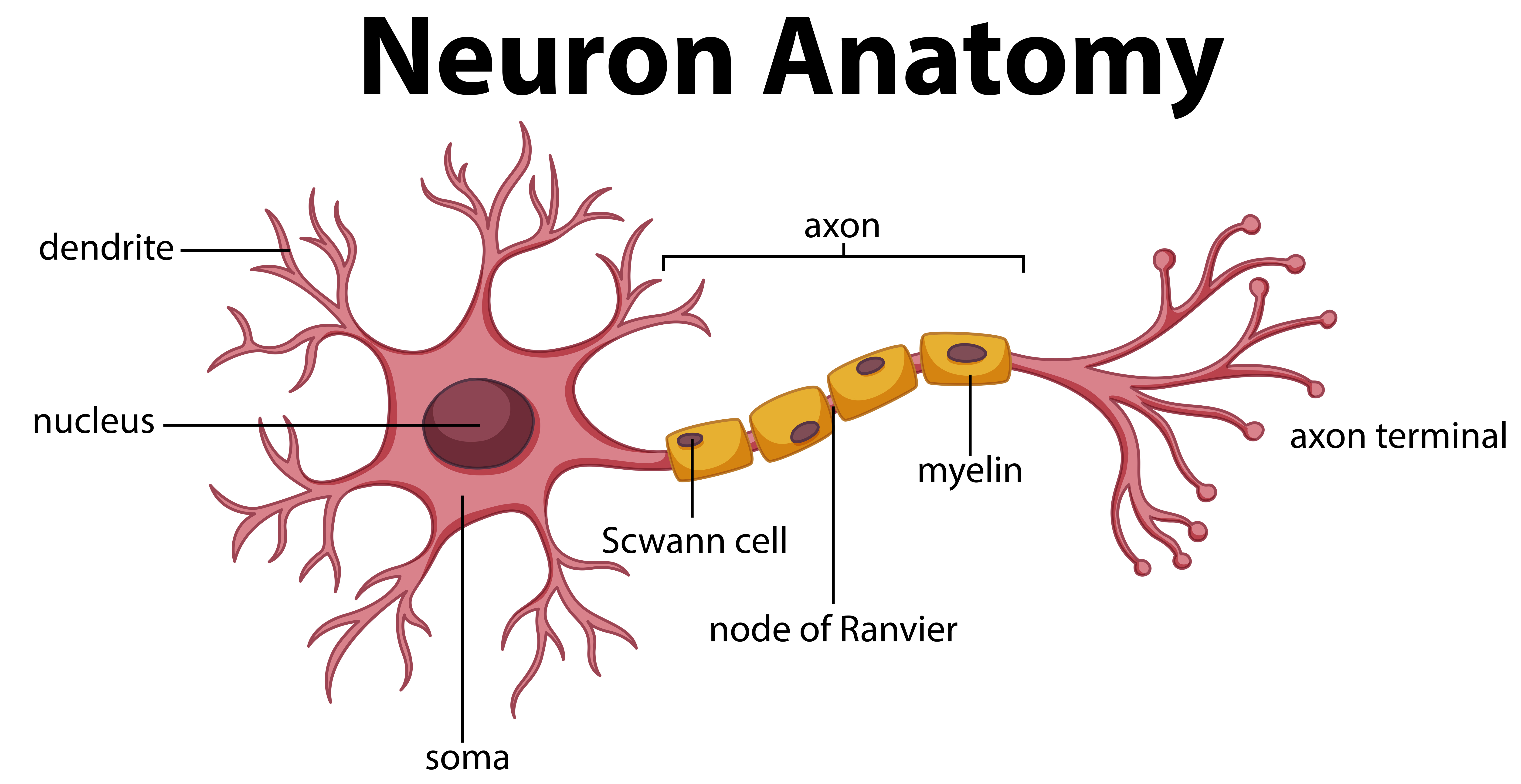

Neurons

The basic functional units of the nervous system. They take in information from other neurons (reception), integrate those signals (conduction), and pass signals to other neurons (transmission).

Glial cells

Nourish, protect, and physically support neurons and are thought to be particularly critical in brain development. One type of glial cell, the oligodendrocyte, covers the axons of neurons with myelin, a substance critical to the effective functioning of the brain.

Speed of propagation of the action potential is determined by?

diameter of axon (bigger = faster)

presence or absence of a myelin sheath

Cortical changes

Infancy and early childhood is characterised by a dramatic period of synaptogenesis, following by an adaptive process of cell death and pruning. There is another notable surge of synapse growth just before puberty.

The strengthening or elimination of synapses is dependent on environmental demands or experience; those that are more often used are strengthened and those that are rarely used are eliminated.

Overall, grey matter (neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and glial cells) development follows an inverted-U pattern of growth, first thickening in volume, peaking, and then thinning

White matter changes

White matter increases in a roughly linear pattern throughout childhood, adolescence, and into early adulthood

However, different brain structures myelinate at different times: myelogenetic cycles

Sensory/motor pathways myelinate early

Regions mediating higher-order functions myelinate late (e.g. the prefrontal cortex)

Development of the Prefrontal Cortex

Grey matter volume: inverted U (early increases followed by gradual decreases starting in late childhood and continuing into adulthood)

White matter volume: Myelination- thought to be complete in the early 20s

Therefore, there is relatively ‘late’ maturation of the prefrontal cortex

Functions of the Prefrontal Cortex

‘Executive’ functions

Working memory

Cognitive flexibility

Inhibitory control

Reasoning

Problem solving

Planning

Executive attention

Executive Functions in children

EF includes:

Working memory: paying attention, remembering facts, using info to complete tasks.

Inhibitory control: following rules, managing emotions, delaying gratification.

Cognitive flexibility: planning, judging, self-correcting.

EF helps children regulate behaviour and develop social, emotional, and cognitive skills over time.

Moffitt et al. (2011): Poor inhibitory control in childhood predicts worse adult outcomes (health, income, crime, happiness).

Explicit Memory

involves intentional recollection of previous experiences (conscious, accessed directly)

Four conclusions about development of explicit memory:

Older children are faster information processors; maturation of nervous system leads to improved short-term memory capacity and efficiency but age does not impact sensory register or long-term memory capacity

Older children use more effective memory strategies in encoding and retrieving information

Older children know more about memory

Older children know more in general and larger knowledge base improves ability to learn and remember

Implicit Memory

apparent when retention is exhibited on a task that does not require intentional remembering. (unconscious, accessed indirectly)

From a developmental point of view, a variety of studies show that explicit memory is significantly increasing throughout infancy and childhood, where implicit doesn’t change as much

STM capacity (Dempster, 1981)

2 years old: 2 items

5 years old: 4 items

7 years old: 5 items

9 years old: 6 items

Metamemory

your awareness and understanding of your own memory processes. It's a key part of metacognition (thinking about thinking).