Topic 14: Redox II

1/33

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

34 Terms

Redox reactions of s-block elements

s-block elements are usually oxidised, losing electrons, increasing in oxidation number, and forming 1+ or 2+ ions.

Redox reactions of p-block elements

p-block non-metals are usually reduced, gaining electrons, decreasing in oxidation number, and forming negative ions.

p-block metals are usually oxidised, losing electrons, increasing in oxidation number, and forming positive ions.

Redox reactions of d-block elements

d-block elements can be reduced or oxidised due to having variable oxidation states.

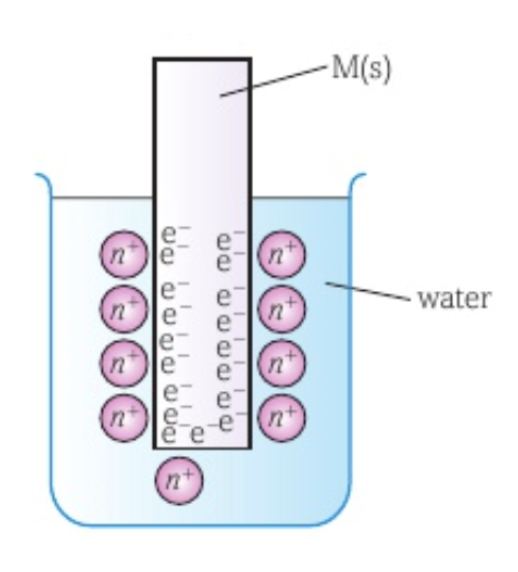

How an electrode works

When a metal is placed in water, some metal atoms lose an electron to form positive ions that are released into the solution.

The electrons remain on the surface of the metal.

The negative charge from the electrons on the surface of the metal attracts the positive ions in the solution, causing a layer of positive ions to form around the metal.

Some of the positive ions regain their electrons and return to form part of the metal’s surface again.

An equilibrium is formed in which the rate that ions leave the metal to go into solution and the rate at which the ions join the metal back are equal: Mn+ (aq) + ne- ⇌ M (s)

A potential difference between the metal and the solution is produced, known as the absolute potential.

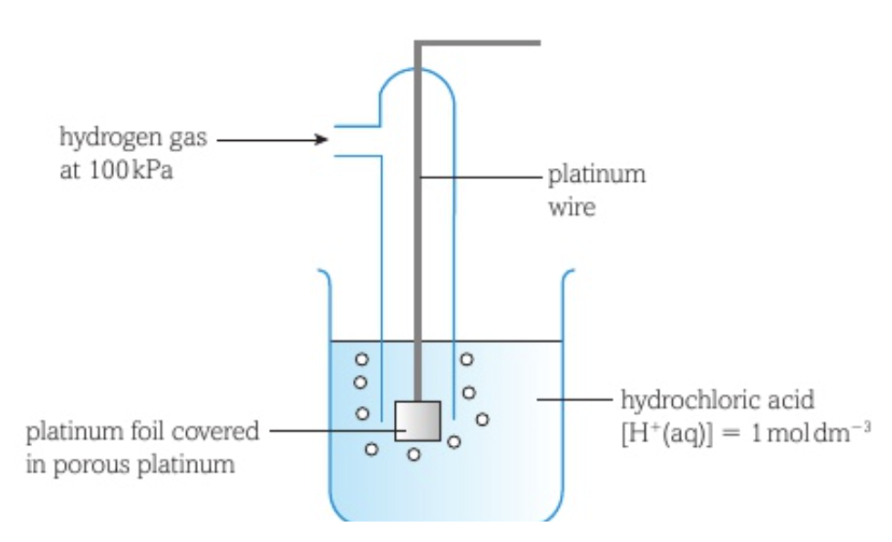

Standard hydrogen electrode

The standard hydrogen electrode is used as a reference electrode.

It consists of hydrogen gas at a pressure of 100kPa bubbling over a piece of platinum foil dipped into a solution of hydrochloric acid with a hydrogen ion concentration of 1 mol dm-3 at a temperature of 298K.

The hydrogen molecules lose electrons to form H+ ions that are released into the solution.

The electrons stay on the surface of the platinum, attracting the H+ ions so they form a layer around the platinum foil.

Some H+ ions regain an electron and form hydrogen gas again.

An equilibrium is formed in which the rate that hydrogen molecules lose electrons and the rate at which H+ ions gain an electron and form hydrogen are equal: H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ 1/2 H2 (g)

The platinum is a catalyst for this reaction and is porous to increase its surface area so an equilibrium between hydrogen gas and hydrogen ions is established quickly.

The standard electrode potential of the standard hydrogen electrode is 0.00.

Standard electrode potential

The standard electrode potential of a half-cell is the emf of a cell containing the half-cell connected to the standard hydrogen electrode under standard conditions of 298K temperature, 100kPa pressure of gases, and 1.00 mol dm-3 concentration of ions.

Symbol is E⦵

Why a reference electrode is necessary

It is impossible to measure the absolute potential of a single electrode, so the standard hydrogen electrode is used as a universal ‘zero’ point other electrodes can be compared to.

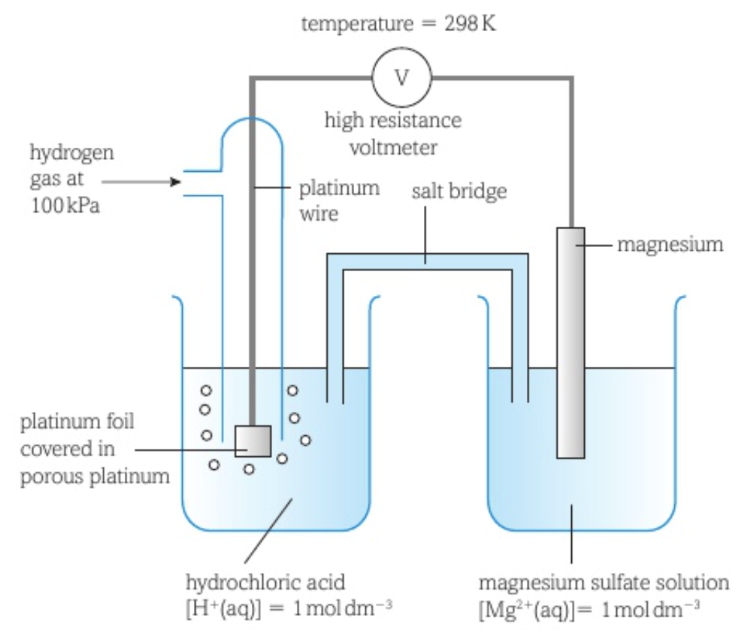

Measuring the standard electrode potential of a metal in contact with its ion in aqueous solution

The standard hydrogen electrode is connected to the metal electrode by a circuit including a high resistance voltmeter, with the standard hydrogen electrode on the left and standard conditions applying to both half-cells.

A high resistance voltmeter is used to minimise the flow of electrons around the external circuit.

The metal half-cell includes a piece of the metal in a solution containing the metal’s ions.

The combination of the hydrogen half-cell and the metal half-cell is called a cell.

The salt bridge completes the circuit by allowing the movement of ions and usually consists of an inert gel of a solution of potassium nitrate. The ions present should not react with the contents of either half-cell.

Two equilibria are set up at the two electrodes: H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ 1/2 H2 (g) and Mn+ (aq) + ne- ⇌ M (s)

These reactions proceed until they are both in equilibrium.

The species that has a greater tendency to lose electrons and produce a positive ion will have more electrons building up on the electrode and so will be the negative electrode. The other electrode becomes the positive electrode.

The voltmeter measures the potential difference between the two electrodes.

A positive reading on the voltmeter means that the hydrogen electrode is the negative electrode and the metal electrode is the positive electrode, so electrons are being pulled from the hydrogen electrode towards the metal electrode.

A negative reading on the voltmeter means that the metal electrode is the negative electrode and the hydrogen electrode is the positive electrode, so electrons are being pulled from the metal electrode towards the hydrogen electrode.

The reading on the voltmeter is equal to the standard electrode potential of the metal half-cell.

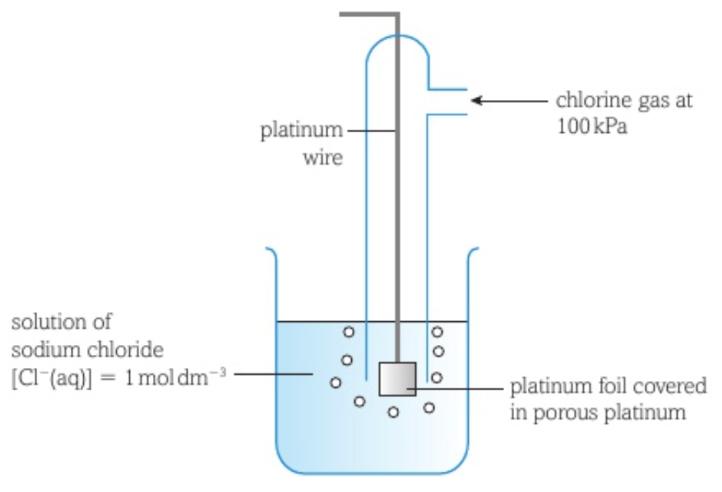

Measuring the standard electrode potential of a gaseous non-metal bubbling through a solution of its ion (chlorine)

The chlorine half-cell consists of a piece of platinum foil with porous platinum on the surface dipped in a solution containing chloride ions with chlorine gas bubbling over the foil.

The standard hydrogen electrode is connected to the non-metal electrode by a circuit including a high resistance voltmeter, with the standard hydrogen electrode on the left and standard conditions applying to both half-cells.

Two equilibria are set up at the two electrodes: H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ 1/2 H2 (g) and 1/2 Cl2 (g) + e- ⇌ Cl- (aq).

Chlorine gains electrons through the circuit from the hydrogen that loses electrons.

These reactions proceed until they are both in equilibrium.

Hydrogen is the species that has a greater tendency to lose electrons and produce a positive ion, so has more electrons building up on the electrode and so the hydrogen electrode will be the negative electrode. The chlorine electrode becomes the positive electrode.

The electrons are being pulled from the negative hydrogen electrode to the positive chlorine electrode, so the reading on the voltmeter is positive.

The reading on the voltmeter is equal to the standard electrode potential of the chlorine half-cell.

Measuring the standard electrode potential of a liquid non-metal mixed with a solution containing its ions (bromine)

The bromine half-cell consists of a piece of platinum foil with porous platinum on the surface dipped in a solution containing bromide ions with pure liquid bromine added to it.

The standard hydrogen electrode is connected to the bromide electrode by a circuit including a high resistance voltmeter, with the standard hydrogen electrode on the left and standard conditions applying to both half-cells.

Two equilibria are set up at the two electrodes: H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ 1/2 H2 (g) and 1/2 Br2 (aq) + e- ⇌ Br- (aq)

Bromine gains electrons through the circuit from the hydrogen that loses electrons.

These reactions proceed until they are both in equilibrium.

Hydrogen is the species that has a greater tendency to lose electrons and produce a positive ion, so has more electrons building up on the electrode and so the hydrogen electrode will be the negative electrode. The bromine electrode becomes the positive electrode.

The electrons are being pulled from the negative hydrogen electrode to the positive bromine electrode, so the reading on the voltmeter is positive.

The reading on the voltmeter is equal to the standard electrode potential of the bromine half-cell.

Measuring the standard electrode potential of a mixture of solutions of ions of the same element with different oxidation numbers (Fe2+ and Fe3+)

The iron ion half-cell consists of a piece of platinum foil with porous platinum on the surface dipped in a solution containing the Fe2+ ions mixed with a solution containing the Fe3+ ions.

The standard hydrogen electrode is connected to the iron ion electrode by a circuit including a high resistance voltmeter, with the standard hydrogen electrode on the left and standard conditions applying to both half-cells.

Two equilibria are set up at the two electrodes: H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ 1/2 H2 (g) and Fe3+ (aq) + e- ⇌ Fe2+ (aq)

Fe3+ gains electrons through the circuit from the hydrogen that loses electrons.

These reactions proceed until they are both in equilibrium.

Hydrogen is the species that has a greater tendency to lose electrons and produce a positive ion, so has more electrons building up on the electrode and so the hydrogen electrode will be the negative electrode. The iron ion electrode becomes the positive electrode.

The electrons are being pulled from the negative hydrogen electrode to the positive iron ion electrode, so the reading on the voltmeter is positive.

The reading on the voltmeter is equal to the standard electrode potential of the iron ion half-cell.

Significance of E⦵ values

The standard electrode potential value for an element provides a comparison of the positions of equilibriums of the two reactions occurring in the half-cells.

A negative value of E⦵ of a half-cell, for example with magnesium: Mg2+ (aq) + 2e- ⇌ Mg (s), means that the position of equilibrium of its reaction at the electrode is further to the left than the reaction occurring at the hydrogen electrode, so the species on the right releases electrons more readily than hydrogen and is therefore a better reducing agent, and the species on the left accepts electrons less readily than hydrogen and is therefore a worse oxidising agent.

A positive value of E⦵ of a half-cell, for example with chlorine: 1/2 Cl2 (g) + e- ⇌ Cl- (aq), means that the position of equilibrium of its reaction at the electrode is further to the right than the reaction occurring at the hydrogen electrode, so the species on the right releases electrons less readily than hydrogen and is therefore a worse reducing agent, and the species on the left accepts electrons more readily than hydrogen and is therefore a better oxidising agent.

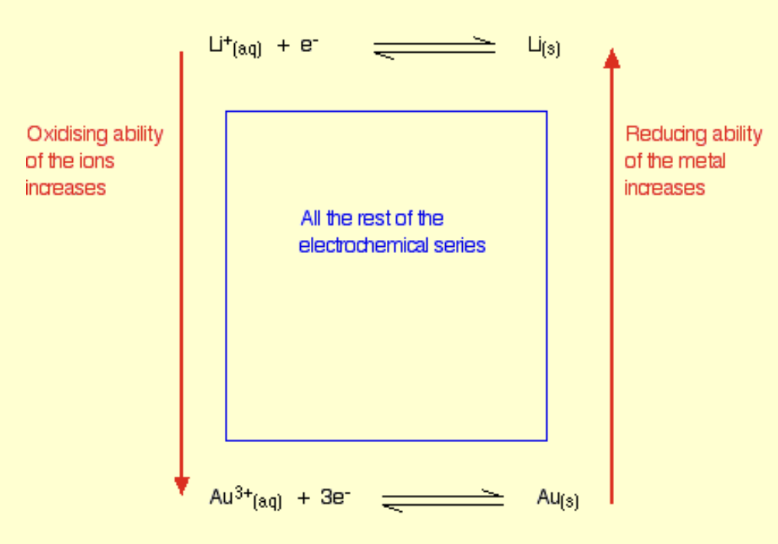

Electrochemical series

The electrochemical series lists redox equilibria in order of their standard electrode potentials, with the most negative being at the top, so in increasing order.

The redox equilibrium at the top has the most negative standard electrode potential, so the species on the right of the equilibrium loses electrons most readily and is the best reducing agent, and the species on the left gains electrons least readily and is the worst oxidising agent.

The redox equilibrium at the bottom has the most positive standard electrode potential, so the species on the right of the equilibrium loses electrons least readily and is the worst reducing agent, and the species on the left gains electrons most readily and is the best oxidising agent.

Cell with zinc and copper half-cells

A galvanic cell is a device that generates an electric current from redox reactions by causing electrons to move from one half-cell to the other through a wire.

The zinc half-cell has the lower standard electrode potential so will have the negative electrode, and the copper half-cell has the higher standard electrode potential so will have the positive electrode.

At the negative electrode, the zinc atoms lose electrons and enter the solution as zinc ions: Zn (s) → Zn2+ (aq) + 2e-. The electrode loses mass.

The electrons move around the external circuit to the positive electrode where copper ions from the solution gain them, causing copper atoms to deposit on the surface of the copper electrode: Cu2+ (aq) + 2e- → Cu (s). The electrode gains mass.

The overall cell reaction is Zn (s) + Cu2+ (aq) → Zn2+ (aq) + Cu (s)

Cell diagrams with example for zinc and copper half-cells

The negative electrode half-cell is described first, then the positive electrode half-cell.

Within a half-cell, the reactants are specified first then the products. A vertical line is used as a phase boundary to separate a solid from other phases. A comma is used if the species are in the same phase, or in aqueous, liquid, or gaseous phases.

A double vertical dotted line represents the salt bridge and is between the two half-cells.

If platinum foil is used, Pt (s) will be on the outside of the half-cell with a phase boundary between the species if they have different state symbols.

Cell diagrams are therefore written in the direction of electron flow.

An exception to these rules is when measuring the standard electrode potential, the standard hydrogen electrode is always written first.

The cell diagram for zinc and copper half-cells is Zn (s) | Zn2+ (aq) || Cu2+ (aq) | Cu (s)

Standard emf of a cell

The standard emf of a cell is the maximum potential difference between the two electrodes of a cell when standard conditions apply.

Symbol is E⦵cell

E⦵cell = E⦵(right / positive electrode) - E⦵(left / negative electrode), so the standard electrode potential of the left half-cell is subtracted from the standard electrode potential of the right half-cell when looking at a cell diagram.

Thermodynamic feasibility of a reaction

The overall reaction occurring in a cell is feasible when the standard emf of the cell, E⦵cell, is positive.

The overall reaction occurring in a cell is not feasible when the standard emf of the cell, E⦵cell, is negative.

Feasibility of the reaction of copper with dilute hydrochloric acid: E⦵ (copper) = +0.34 V and E⦵ (hydrogen) = 0.00 V

Cu (s) + 2HCl (aq) → CuCl2 (aq) + H2 (g)

The reactions in the two half-cells: Cu (s) → Cu2+ (aq) + 2e- and 2H+ (aq) + 2e- → H2 (g)

For the reaction to occur, the copper electrode must be negative and the hydrogen electrode must be positive.

E⦵cell = 0.00 - 0.34 = -0.34 V

Therefore, the standard emf of the cell is negative and the reaction is not feasible.

Importance of conditions when when measuring the standard electrode potential of a half-cell with copper as an example: E⦵ (copper) = +0.34 V and E⦵ (hydrogen) = 0.00 V

When a copper half-cell is connected to a standard hydrogen electrode, the standard emf of the cell is 0.34 - 0.00 = +0.34

The reactions in the two half-cells: Cu2+ (aq) + 2e- ⇌ Cu (s) and H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ 1/2 H2 (g)

If the concentration of Cu2+ ions increases, the equilibrium position shifts to the right, making the electrode better at gaining electrons and making the E⦵ value more positive than +0.34 V.

If the concentration of Cu2+ ions decreases, the equilibrium position shifts to the left, making the electrode worse at gaining electrons and making the E⦵ value less positive than +0.34 V.

Feasibility of the reaction manganese (IV) oxide with hydrochloric acid and the effect of increasing the hydrochloric acid concentration: E⦵ (chlorine) = +1.36 V and E⦵ (manganese (IV) oxide) = +1.23 V

MnO2 (s) + 4HCl (aq) → MnCl2 (aq) + 2H2O (l) + Cl2 (g)

The reactions in the two half-cells: MnO2 (s) + 4H+ (aq) + 2e- → Mn2+ (aq) + 2H2O (l) and 2Cl- (aq) → Cl2 (g) + 2e-

For the reaction to occur, the manganese (IV) oxide electrode must be positive and the chlorine electrode must be negative.

E⦵cell = 1.23 - 1.36 = -0.13 V

Therefore, the standard emf of the cell is negative and the reaction is not feasible.

However, if the hydrochloric acid concentration is increased, the equilibrium position of MnO2 (s) + 4H+ (aq) + 2e- ⇌ Mn2+ (aq) + 2H2O (l) shifts to the right, and the equilibrium position of 2Cl- (aq) ⇌ Cl2 (g) + 2e- shifts to the right.

The electrode potential of the manganese (IV) oxide half-cell becomes more positive, as the electrode is a better electron acceptor.

The electrode potential of the chlorine half-cell becomes less positive, as the electrode is a better electron releaser.

E⦵cell therefore becomes positive because 1.23 increases and 1.36 decreases.

Feasibility of the disproportionation reaction of 2Cu+ (aq) → Cu2+ (aq) + Cu (s): E⦵(Cu+ + e- ⇌ Cu) = +0.52 V and E⦵(Cu2+ + e- ⇌ Cu+) = +0.15 V

The reactions in the two half-cells: Cu+ (aq) → Cu2+ (aq) + e- and Cu+ (aq) + e- → Cu (s)

For the reaction to occur, the Cu2+ + e- ⇌ Cu+ half-cell must be negative and the Cu+ + e- ⇌ Cu half-cell must be positive.

E⦵cell = 0.52 - 0.15 = +0.37 V

Therefore, the standard emf of the cell is positive and the reaction is feasible.

Relationship between the standard emf of a cell and total entropy change

If E⦵cell is positive, the overall reaction in a cell is feasible and the total entropy change will be positive.

Thus, ΔS⦵total ∝ E⦵cell: the standard emf of a cell is directly proportional to the total entropy change of the overall reaction occurring in the cell.

Relationship between the standard emf of a cell and the equilibrium constant, K

ΔG = ΔH - TΔSsystem

ΔSsurroundings = -ΔH / T can be rearranged to ΔH = -TΔSsurroundings

Substituting into the first equation obtains ΔG = -TΔSsurroundings - TΔSsystem

Factorising this obtains ΔG = -T(ΔSsurroundings + ΔSsystem), which can be simplified to ΔG = -TΔStotal

ΔG = -RTInK

Therefore, -TΔStotal = -RTInK, which is ΔStotal = RInK

Therefore, ΔStotal is directly proportional to lnK.

Since ΔStotal is also directly proportional to E⦵cell, E⦵cell is directly proportional to InK, with K being the equilibrium constant of the cell reaction.

Limitations of predictions made using standard electrode potentials

The standard emf of a cell will tell you if the overall reaction taking place is thermodynamically feasible, but will not take into account the kinetic feasibility of the reaction: it may take place too slowly or the activation energy may be too high.

The standard emf of a cell is calculated from the standard electrode potentials of half-cells, which are only accurate when the conditions are standard throughout. In reality, the conditions may deviate from being standard.

Storage cells

A storage cell is a cell that can be recharged.

The voltage of a storage cell is determined by the difference between the standard electrode potentials of the two half-cells used, so a higher difference produces a higher voltage storage cell.

During recharging, an external voltage greater than the cell’s own emf is applied with the current in the opposite direction to the flow of current generated by the cell, forcing electrons to move in the opposite direction and reversing the reactions that occurred when the cell is discharging.

Fuel cell

A fuel cell produces a voltage from the energy released from the chemical reaction of a fuel with oxygen.

Methanol and other hydrogen-rich fuels are used in fuel cells.

Hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell with acidic electrolyte

Hydrogen gas at one electrode passes over a platinum catalyst where it is oxidised, releasing electrons, making this electrode the negative electrode: H2 (g) → 2H+ (aq) + 2e-

The H+ ions move through the acidic electrolyte to the positive electrode, and the electrons pass through the external circuit to the positive electrode.

Oxygen gas at the other electrode passes over a platinum catalyst where it is reduced, reacting with the arriving protons and electrons to form water: 1/2 O2 (g) + 2H+ (aq) + 2e- → H2O (l)

The overall cell reaction is 1/2 O2 (g) + H2 (g) → H2O (l)

The flow of electrons through the external circuit creates an electric current and a voltage.

Hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell with alkaline electrolyte

Oxygen gas at one electrode passes over a platinum catalyst where it is reduced, reacting with water from the electrolyte and electrons from the external circuit, making this electrode the positive electrode: 1/2 O2 (g) + H2O (l) + 2e- → 2OH- (aq)

The OH- ions move through the alkaline electrolyte to the other electrode.

Hydrogen gas at the other electrode passes over a platinum catalyst where it is oxidised, reacting with the arriving OH- ions to release electrons, making this the negative electrode: H2 (g) + 2OH- (aq) → 2H2O (l) + 2e-.

The electrons pass through the external circuit to the positive electrode.

The overall cell reaction is 1/2 O2 (g) + H2 (g) → H2O (l)

The flow of electrons through the external circuit creates an electric current and a voltage.

Redox titration of potassium manganate (VII) with iron (II) ions

The iron (II) ion solution is titrated with the potassium manganate (VII) solution as titrant.

The potassium manganate (VII) solution is acidified by dilute sulfuric acid to provide the H+ ions required for the reduction.

The manganate (VII) ion is the oxidising agent and is therefore reduced. The oxidation number of manganese goes from +7 to +2.

The iron (II) ion is the reducing agent and is therefore oxidised. The oxidation number of iron goes from +2 to +3.

Reduction half-equation: MnO4- (aq) + 8H+ (aq) + 5e- → Mn2+ (aq) + 4H2O (l)

Oxidation half-equation: Fe2+ (aq) → Fe3+ (aq) + e-

Overall equation: MnO4- (aq) + 5Fe2+ (aq) + 8H+ (aq) → Mn2+ (aq) + 5Fe3+ (aq) + 4H2O (l)

The end-point of the titration will be when the solution turns pink, as potassium manganate is in excess.

Choice of acid to acidify potassium manganate (VII)

Dilute sulfuric acid is used as it will not oxidise the analyte and will not react with the manganate (VII) ions.

Hydrochloric acid is not used, as it will be oxidised by the manganate (VII) ions.

Nitric acid is not used, as it may oxidise the analyte.

Concentrated sulfuric acid is not used, as it may oxidise the analyte.

25.0 cm3 of iron (II) sulfate solution reacts with 22.40 cm3 of 0.0200 mol dm-3 potassium manganate (VII) solution. Calculate the concentration of the iron (II) sulfate

MnO4- (aq) + 5Fe2+ (aq) + 8H+ (aq) → Mn2+ (aq) + 5Fe3+ (aq) + 4H2O (l)

1 mole of MnO4- reacts with 5 moles of Fe2+

Amount of MnO4- = 4.48 x 10-4 mol

Amount of Fe2+ = (4.48)(10-4)(5) = 2.24 x 10-3 mol

Concentration of iron (II) sulfate: (2.24)(10-3) / 0.025 = 0.0896 mol dm-3

Redox titration of iodine and sodium thiosulfate

The iodine solution is titrated with the sodium thiosulfate solution as titrant.

The iodine is the oxidising agent and is therefore reduced. The oxidation number of iodine goes from 0 to -1.

The thiosulfate ion is the reducing agent and is therefore oxidised. The oxidation number of sulfur goes from +2 to +2.5.

Reduction half-equation: I2 (aq) + 2e- → 2I- (aq)

Oxidation half-equation: 2S2O32- (aq) → S4O62- (aq) + 2e-

Overall equation: 2S2O32- (aq) + I2 (aq) → S4O62- (aq) + 2I-

The solution goes from the brown colour of iodine to a pale-yellow, as the iodine is reacted with.

When the solution is pale-yellow, add starch solution, causing the solution to go blue-black due to the presence of iodine.

Continue titrating until the blue-black colour disappears and becomes colourless, meaning that the iodine has been completely reacted with.

Ensure the iodine is not added too early, as it will adsorb some iodine.

How a salt bridge is made

Filter paper soaked in saturated potassium nitrate solution connecting the two beakers.

Dichromate (VI) ion

Cr2O72-