The Economics of Regulation L5

1/22

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

23 Terms

What are social concerns that regulation might confronted with?

Policy makers and regulators try to balance the policy goals of regulation (financial viability, externalities, environmental goals), and the social goals, and such balance is often case-specific.

In particular, the practice of regulation is mostly about:

• Financial viability

• The desire to protect the poor

→ trade off is not easy to solve in practice

Explain the californian experience in regulating the electricity market

• Goal: design a tariff that guarantees financial viability of the regulated operators but also meets social concerns → through block pricing

• Problem: how to design it correctly

A first iteration lasted until the 2000-2001

• the tariff was intended to guarantee low price to the low-income households, however, more than 1/3 of users was actually in this block and very few in the top

• the tariff lacked much of the (price) incentive to discourage overconsumption which led to systemic fragility and the 2000-01 electricity crisis

→ The crisis led to a change of the tariff: different prices (then reduced to 4), but without really achieving the goals of reducing overconsumption and redistributing the weight of the financing between social groups

Problem: it is difficult to design the tariff & facing a complex menu, consumers tend to respond more to the average that to the marginal price

From 2016 to 2019, many new versions were introduced and replaced, including a super-user surcharge

• First, the block structure was simplified to 2 tiers

• In 2017 the super-user surcharge was introduced

• In 2019, the system moved to time-of-use rates, with discounts for poor households

Lessons:

• Price discrimination is not easy to implement (think about the design of Proximus’ tariff)

• For PD to be effective, it has to be internalized by users

• Targeting is self-identification makes things easier for redistribution purposes

How can Block-pricing meet social concerns?

Price discrimination can be the way to both ensure the financial viability of a service, and to redistribute its burden in favor of poorer households

The idea is simple: charge relatively more richer users to lower the price to poorer users

Increasing block pricing is widely adopted, for instance in water supply, electricity etc. especially in low- and middle-income countries

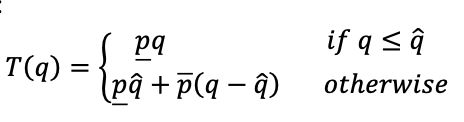

how does the block pricing theory work?

Suppose that in the community there are two categories of consumers, whose types are H (high WTP) and L (low WTP)

Instead of charging a (uniform) price p, which would damage the poor, a regulator could implement an increasing block pricing scheme:

This scheme (if designed carefully):

• Discourages overconsumption thanks to the high marginal price for high consumption

• Reduces the price for the weak users

• In principle, it does not pose a legal or ethical problem of equal treatment of citizens in accessing a fundamental good, as the first amount of units 𝑞

µ is paid the same by everyone (see later example)

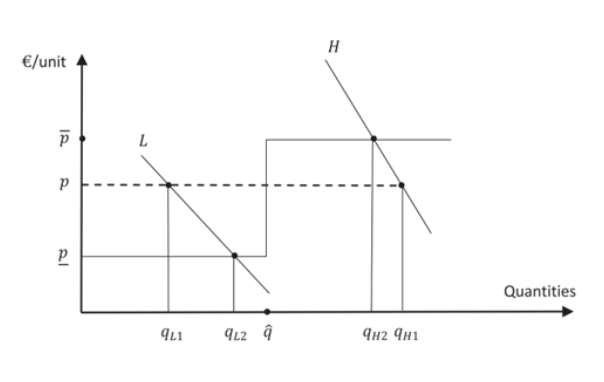

comparison uniform price vs block pricing

Compared to the outcome under uniform price, the block pricing makes

• Type L to increase consumption from 𝑞L1 to 𝑞L2

• Type H to reduce consumption from 𝑞H1 to 𝑞H2

→ The problem for the regulator is to have enough information on the demand for the service of different groups, so that it can figure out the right low_𝑝, 𝑞^

& high_𝑝, which together with 𝑛L and 𝑛H , will determine:

• The total consumption of the product or service 𝑛L𝑞L2 + 𝑛H𝑞H1

• The revenues 𝑛LT(𝑞L2) + 𝑛HT(𝑞H1)

→ If H is indeed typically a rich household, and L is typically a poor household, this is an attractive scheme to redistribute the burden of service provision

What can be the risks of block pricing?

• Getting the parameters wrong

• Even when the parameters are right, the relative proportions of 𝑛L and 𝑛H can have important implications (depending on the elasticity of demand), on final consumption

→cutting too much and too quick the price can lead to a demand beyond capacity (problem relevant in developing countries)

Other possible problems

The discussion so far relies on some underlying concepts

• The good or service is normal, meaning that consumption increases with income

• The correlation between WTP and income is strong

In practice, this is not necessarily the case

• Section 9.3: poorer households tend to have a relatively high demand for water or energy (more children or dependent relatives, less efficient buildings) → scientific studies pointing at a low, if not zero, correlation between consumption and income and not only the previous factors, also behavioral biases, awareness of the price scheme etc.

• In practice, it is difficult to design schemes that do not require explicit self-selection or targeting, which however, come with bureaucratic costs of data collection, screening etc.

Explain failed reform of the energy tariff in France

Before we mentioned the possible legal implications of PD

• Note: for long time, after the beginning of antitrust, even the US jurisprudence considered PD illegal

Example: 2013 attempt to reform the regulated energy prices in France with new tariff based on a progressive scheme:

• An yearly volume benchmark v would be determined for each household based on geographical location, type of heating, number of people in the household etc.

• The first block v of volume would be priced with a rebate up to 20% (depending on parameters) of the standard price

• The second block, until 3v of volume would be priced with a small surcharge (approx 5%) of the standard price

• Above 3v, the surcharge could be up to 50% of the standard price

→ The reform was deemed unconstitutional by the French Constitutional Court on the ground that it would violate citizens’ equal claim to public service obligations

who needs help?

In practice, the first step to meet social concerns is to correctly target the recipients of lower rates, subsidies etc.

This might not be as easy as it seems and two errors can happen:

• Exclusion error: to miss a part of the target population

• Inclusion error: to favour people who in principle do not need it

The risk that the policy maker is willing to take depends on the service and on the policy maker’s preferences (often political)

When assessing who need help, is there a difference btw developed & developing countries?

Thinking both of developed and developing countries, two main distinct issues emerge:

• the problem of access

• the problem of affordability

While access is relatively straightforward, affordability is less so

Typical patterns that we observe are:

• Low income households spend relatively more in basic services such as water and electricity

• High income households spend relatively more in services like transportation (including own car) and ICT

when is affordability a problem?

• A social group has an affordability problem when it is forced to ration, i.e., despite a relatively high WTP the financial resources inhibit the household from purchasing the product or service

No general rule but many context specific thresholds developed by regulators:

• WHO has a 5% rule water and sanitation in developed countries (3.5% for water alone)

• In developed countries, spending more than 4-5% on energy is a signal of affordability problems

what is trade off concerning the delivery of quality?

The quality of a service is often of high importance for end-users

• Health care

• Reliability of transportation

• Reliability of energy supply

• Safety of drinkable water

On the supply-side, the cost driver is relevant, but not always easy to monitor

• It is often multi-dimensional

• Both efforts to deliver high quality and the quality itself can be hard to verify, both ex-ante and ex-

post

→ The combination of the two can make quality regulation challenging

Give me an example on regulating quality

Regulating Motorways

Regulating quality can be challenging because it is multi-dimensional:

• Type of asphalt used determine the performance in different condition (e.g., draining water fast during heavy rainfall, moisture resistance, cracking resistance)

• Congestion during rush hours (related to the availability of lanes)

• Frequency and size of potholes and average time to repair

→ Higher quality level implies higher costs, which have to be passed to the users through tolls and/or circulation tax, and/or to the taxpayer

Can it be monitored? Mostly so in this case!

UK case (see section 10.1):

• Creation of the Office of Rail and Road (ORR) overseeing the governmental agency for highways (separated entity of the Ministry of Transportation)

• Mandate this agency to:

a) Produce performance indicators;

b) To produce plans for improvements;

c) To inform negotiations

• Performance is then benchmarked nationally and internationally

Main indicators:

• Lane availability

• Share of accidents cleared within 1 hour

• Users’ satisfaction

• Effort done to minimize average delays

• Share of pavement not requiring further investigations

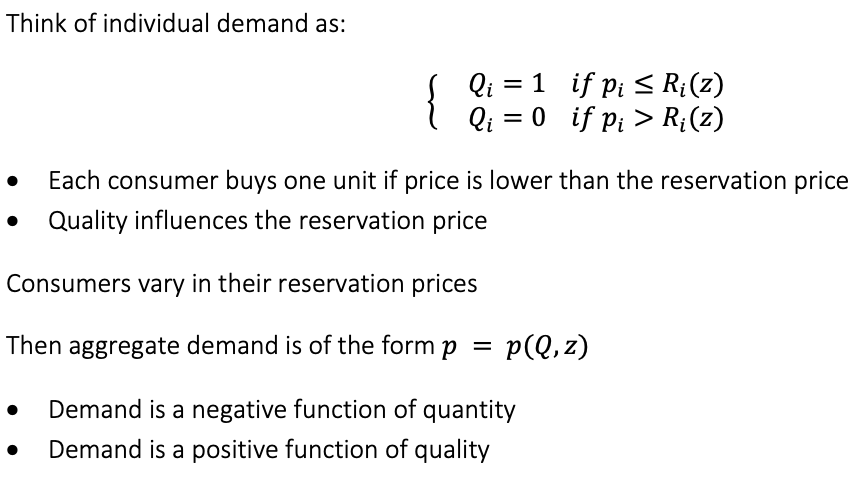

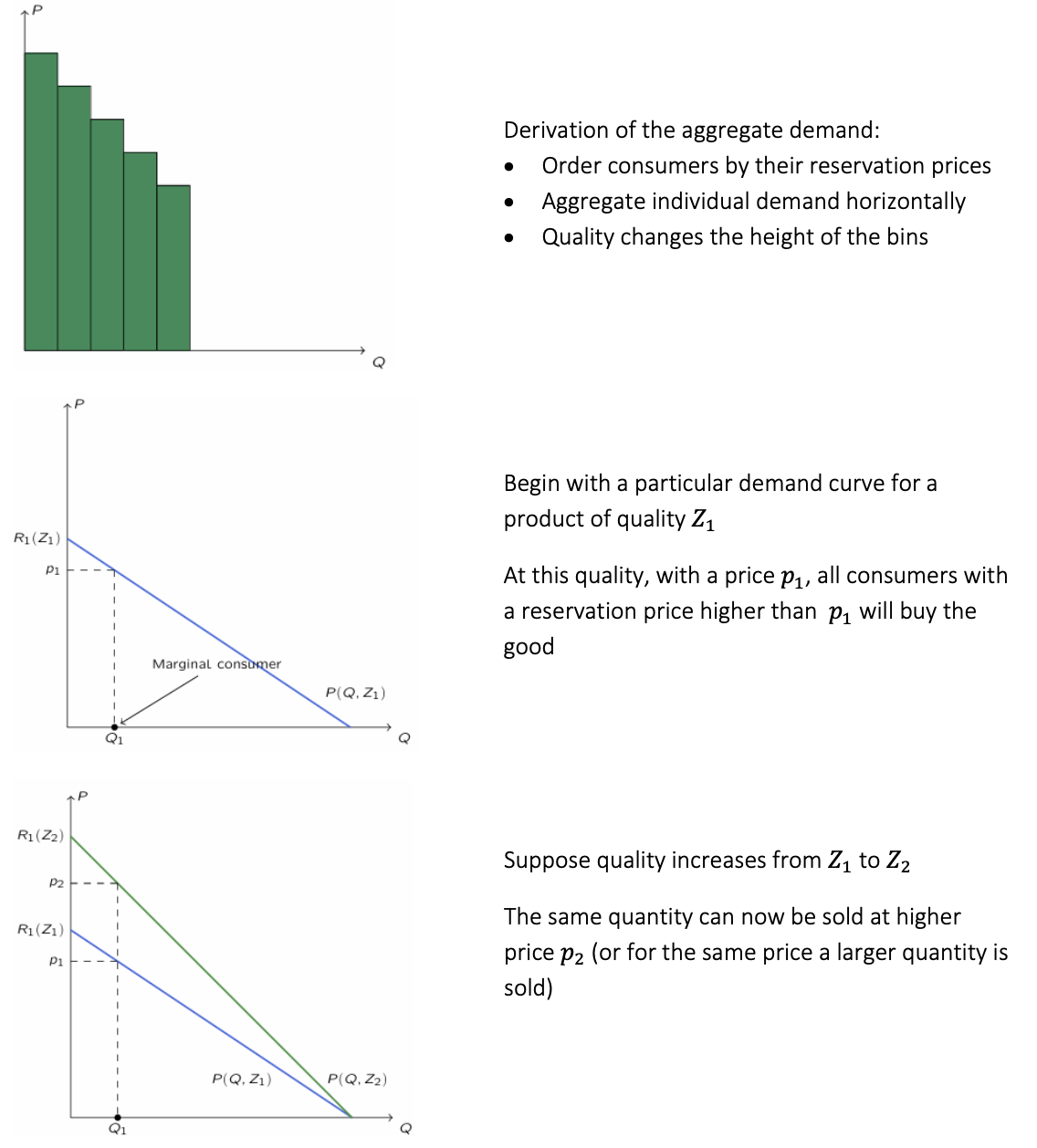

How do we adapt demand for it to be affected by quality?

How would this adapted version of D look graphically?

how can we apply this quality framework to the previous agency problem?

In line with the previous framework, consider the problem of an agency when:

Demand for a product/service is 𝑝(𝑞, 𝑧̃), where 𝑧̃ is the perceived quality

Firm (say a monopolist), can produce at cost C(q,z) where z is the actual quality

then, if the mismatch between 𝑧̃ and 𝑧 is large, the difference between what is optimal for society and what is done by an unregulated monopoly is also large

When quality is difficult to observe by the regulator and difficult to perceive by the users, but it is of great importance to society (e.g., health care), agencies tend to:

Invest resources in monitoring quality of service (i.e., learn about 𝑧)

Require minimum standards to avoid under-investments in quality by the regulated suppliers

how does quality affect the price?

Give the 4 categories of quality

1) Objective vs. subjective attributes:

Quality is more objective when it is easier to measure.

Subjective quality attributes can be measured with noise due to idiosyncratic differences in valuations, differences in the experiences with the service, which are hard to capture with an objective measurement.

2) Vertical quality vs. horizontal quality:

Attributes such that they can be unanimously ranked from low to high quality are vertical differentiated.

If an attribute cannot be unanimously ranked by different individuals, then quality is horizontal

3) Verifiable vs. non-verifiable:

Verifiable attributes are easily measured by the regulator and/or by the users and so they can be included in the contractual agreements with the regulated supplier.

Non-verifiable attributes pose problems of potential under-investments in quality and moral hazard (similar to those discussed in Lecture 2).

4) Ex-ante vs. ex-post verifiability:

Quality attributes that can be verified ex-ante are those that the consumer/authority can check before purchase/consumption. These are the attributes that generally do not pose problems as they can be targeted by the regulator and verified by consumers even before obtaining the service.

Quality attributes that can be verified ex-post are verifiable, but only after purchase/consumption (e.g., actual quality of communication, actual service quality in transportation). There is scope for effective regulation, in particular when they can be objectively measured.

→When attributes’ quality cannot be verified, neither ex-ante nor ex-post, we talk about credence attributes.

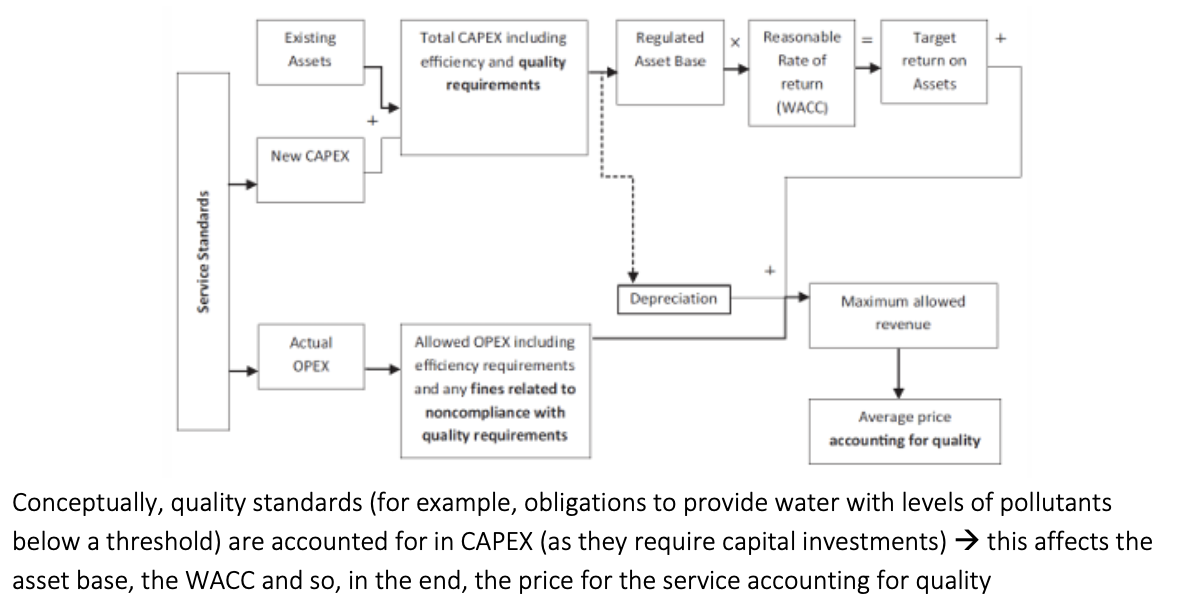

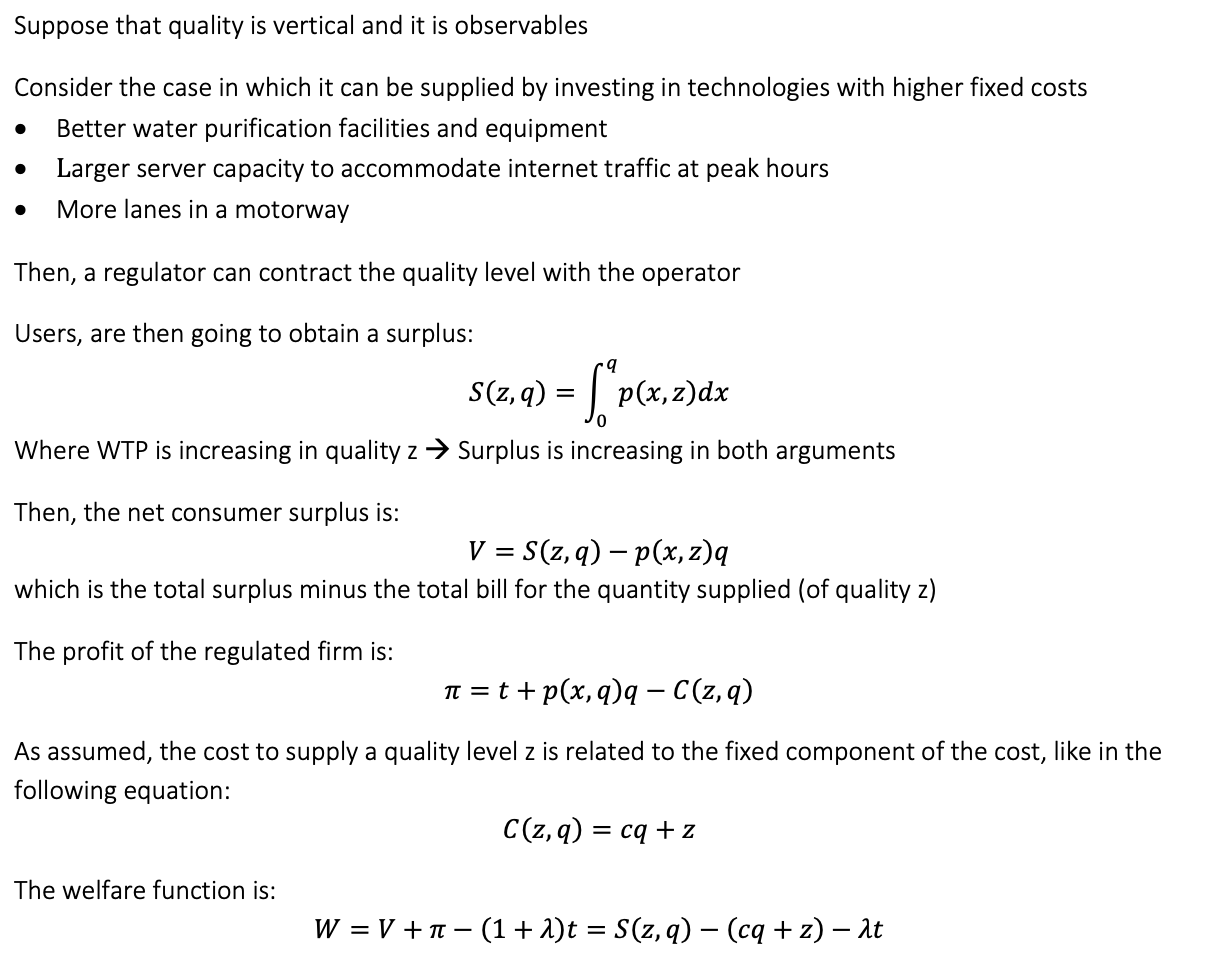

Regulating quality under complete information PT.1

Regulating quality under complete information PT.2

Regulating quality under incomplete information PT.1

Regulating quality under incomplete information PT.2

The results discussed rely on the assumption on the cost structure (separability between quantity and quality in the cost function), and the perfect observability of the quality delivered, which makes the rent only coming from the private information of the firms on the cost to produce the quantity.

→ In other words, in this case quality is lower with less efficient providers not because they are less efficient in providing quality (things would be even worse in this case), but just because they are less efficient in production for given quality when quality and quantity are complementary

Implication for the practice of regulation

Think back at the two main approaches in the practice of regulation, what are the main concerns related to quality in the case of asymmetric information?

Cost-plus: the possibility to inflate costs, potentially leading (in the best scenario of verifiability of quality ex-post) to over-investing in quality, and thus higher prices and potential problems of affordability for some groups of users

Price-cap: the incentive to cut on costs to increase profitability, and so under-investing in quality. Given that caps are very popular among regulators, the typical solution adopted is to adjust the formulas for (observable) investments in quality: 𝑝t = 𝑝t-1(1 + 𝑅𝑃𝐼 − 𝑋 + 𝑍)

where z is a service quality adjustment factor

are there other solution to enforce/account for meeting quality standards?

Fines for non-compliance of quality standards are often included in the regulatory provisions with a service provider

Leaving aside the issues related to the incentives provided through fines (probability that quality under-provision is detected and litigation costs), one important dimension of fines is the amount, which can be:

• Just set to compensate the damage to users or the excess profits associated with quality under-provision (this possibility highly depends on the complexity of the quantification of such amount)

• More morally oriented

→ Importantly, fines and prosecutions should be set to induce the maximum deterrence at the lowest cost