Week 9 - Social Interaction

1/30

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

31 Terms

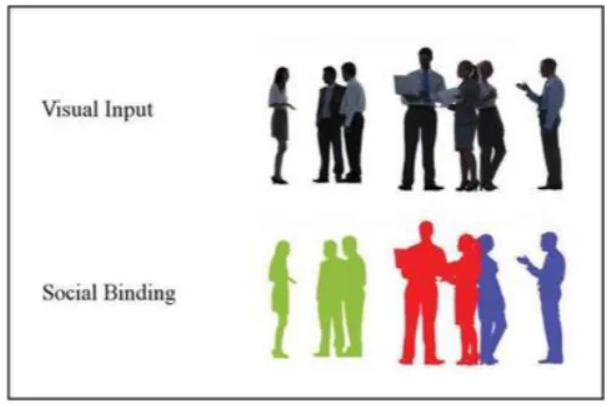

What is social binding versus visual input?

Refer to different levels of processing in human perception, particularly in how we understand social scenarios.

Visual input refers to the raw, low-level sensory information received by the eyes (e.g., colors, shapes, movements, and spatial arrangements of objects and people). The brain's visual system processes this information rapidly to identify basic features and patterns.

Social binding is a proposed mechanism for a faster, more efficient way the brain interprets this visual input in a social context. It is the process by which the visual system automatically groups individual people into meaningful social units or events, based on cues like proximity or mutual gaze.

Why are social interactions prioritised?

Because of their critical evolutionary and social significance for human survival and functioning.

The visual system has evolved specialized, automatic mechanisms to rapidly detect, attend to, and process social information, even over non-social stimuli or when attention is directed elsewhere.

Survival Advantage: Rapidly identifying social interactions (e.g., potential threats, allies, or mates) provided a significant evolutionary advantage. The ability to quickly understand others' actions, goals, and intentions is fundamental for navigating a complex social world effectively.

Automatic Processing: The brain processes socially relevant stimuli (like faces, eyes, and body movements) in dedicated visual regions, often automatically and without conscious effort. This allows for the efficient gating of vital social cues to conscious awareness, even when visual inputs are ambiguous or competing for attention.

Facilitating Social Cognition: Prioritizing social cues, such as joint attention (following someone's gaze to a shared object), acts as a fundamental building block for higher-level social cognitive processes like empathy, communication, and "theory of mind" (inferring mental states in others).

Coordination and Learning: Visual social cues are essential for coordinating behavior with others (e.g., during joint tasks or conversations) and are vital for social learning and skill development, particularly in childhood.

Behavioral Benefits: Strong social connections fostered through these interactions are linked to improved mental well-being, better physical health outcomes, and cognitive benefits such as enhanced memory and attention.

How did Vestner et al. (2019) test spatial distortion (facing vs. facing away) using a visual search task?

This task measured how quickly participants could find a target pair among distractors, suggesting how efficiently the stimuli were processed.

Procedure:

Participants initiated a trial by holding down the spacebar, which presented four stimulus pairings (dyads of people or objects like arrows/cameras) in the four quadrants of the screen.

Most quadrants contained distractor pairs, and one contained the target pair.

The target could be a "front-to-front" (facing) dyad or a "back-to-back" (non-facing) dyad. The distractors typically consisted of pairs all facing the same direction (e.g., both left or both right).

Participants were instructed to release the spacebar as soon as they found the target.

Releasing the spacebar caused the stimuli to disappear, and participants then indicated the target's location by pressing a corresponding keyboard key.

Measurement: The primary measure was the reaction time (RT) from stimulus onset until the spacebar was released. Faster RTs indicated easier detection.

Key Finding: Participants found facing (front-to-front) target pairs faster than back-to-back target pairs when hidden amongst distractors that faced the same direction.

How can perceived distance between people be affected by psychosocial factors?

Psychosocial factors significantly influence the perceived distance between individuals, which differs from actual physical proximity. This phenomenon, known as proxemics, involves several key factors:

Cultural Background: Cultural norms heavily dictate appropriate personal space. People from "contact cultures" (e.g., in Latin America or the Middle East) typically feel comfortable standing closer to others than people from "non-contact cultures" (e.g., in North America or Northern Europe), and these differences can lead to misinterpretations of distance.

Relationship Type: The perceived distance is largely dependent on the nature of the relationship. We naturally perceive less distance between ourselves and close friends, family members, or romantic partners compared to strangers or authority figures.

Emotional State: Current emotions can alter perceived distance. Feelings of anxiety, fear, or discomfort often increase the perceived distance as individuals seek more space, while positive emotions like happiness or excitement may decrease it.

Personality and Comfort Levels: Introverted individuals or those with a higher need for personal space generally perceive a greater distance as necessary for comfort than extroverts or those comfortable with close proximity.

Power Dynamics/Status: Hierarchical relationships affect perceived distance. Individuals in positions of authority or of higher social status often maintain more space from subordinates, which emphasizes the power differential.

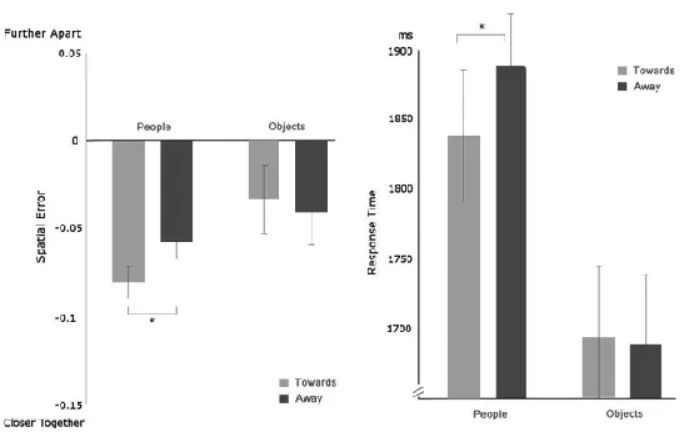

What has been found about people facing vs. facing away and perceived distance?

Studies have found that people generally perceive individuals (or avatars) who are facing toward them as physically closer than those who are facing away, even when the actual distance is the same.

This effect has been observed in both real-life and virtual reality settings, and several potential explanations for it have been explored:

Action Tendencies: People maintain a larger actual distance from a person's front than their back in social interactions. This perception bias (seeing a facing person as closer) may serve an adaptive, self-preservation function by enhancing the apparent danger or potential for interaction, thus promoting quicker reactions or appropriate social distance behavior.

Attention Guidance: Observers tend to focus their attention on the front of a person or object. This closer focus of attention may result in shorter distance estimates compared to when their attention is directed to the back of a person facing away.

Social vs. Lower-level Processing: The effect seems to be driven by general body orientation (front vs. back) rather than specific social cues like eye gaze, which might suggest lower-level visual processing is involved. However, some research suggests the "social interaction hypothesis," where face-to-face dyads are processed as a single social unit, compressing the perceived distance between them.

Emotional/Anxiety Factors: Subjective factors influence distance perception. For instance, people with high social anxiety tend to perceive strangers as being closer than they actually are, which in turn predicts their preference for a greater physical distance.

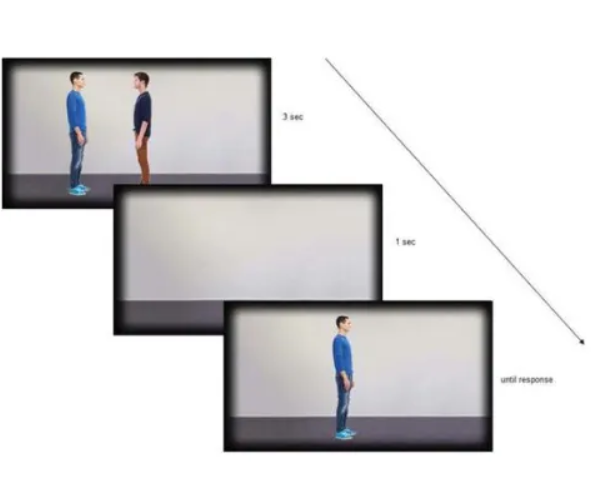

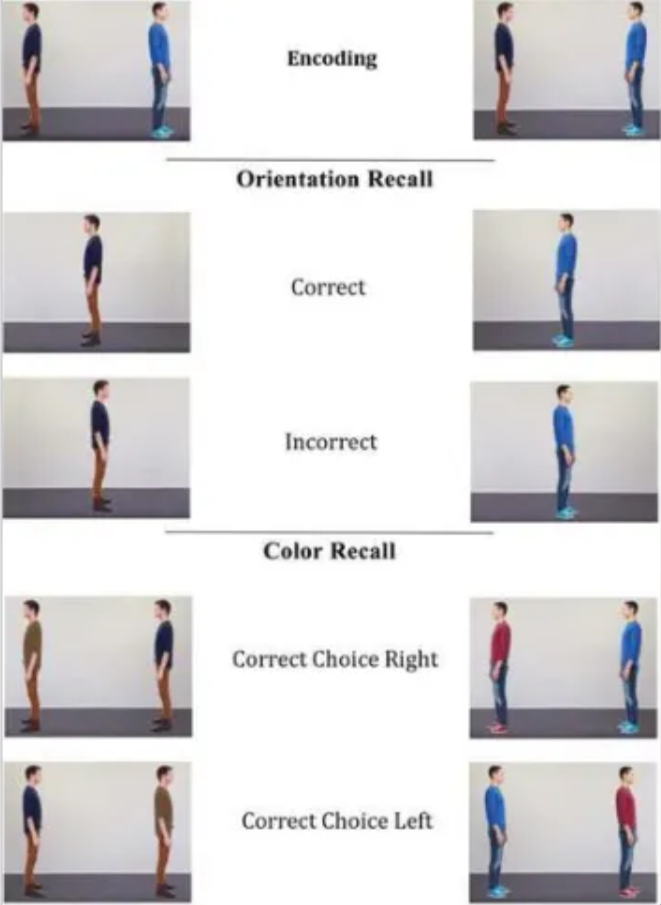

How did Vestner et al. (2019) test spatial distortion (facing vs. facing away) using a spatial memory task?

The primary task involved participants judging or remembering the interpersonal distance between two individuals (dyads).

Stimuli: Participants were shown pairs of human silhouettes, arranged either face-to-face (facing) or back-to-back (facing away/non-facing).

Procedure: In one version, participants were shown a dyad, followed by a blank interval, and then the same dyad again at a different location. They were asked to judge whether the inter-individual distance had changed from the initial presentation.

Spatial Distortion Measure: The researchers found that facing dyads were remembered as being physically closer together than back-to-back dyads, consistent with a spatial memory distortion or "distance compression effect". This effect suggests that facing dyads are processed as an integrated social unit, compressing the perceived spatial representation between them.

The inclusion of colour, which was irrelevant to the main distance judgment task, came in a surprise memory task following the main experiment. This surprise test was used to see if participants had enhanced memory for various features (including color) when they had previously processed the individuals as an "interacting" (facing) social unit.

Memory Retention: The results showed that memory retention of both group-relevant and group-irrelevant features (like color) was enhanced when recalling interacting partners. This indicates that processing a dyad as a social interaction leads to better overall feature binding and memory for the elements that form that social unit.

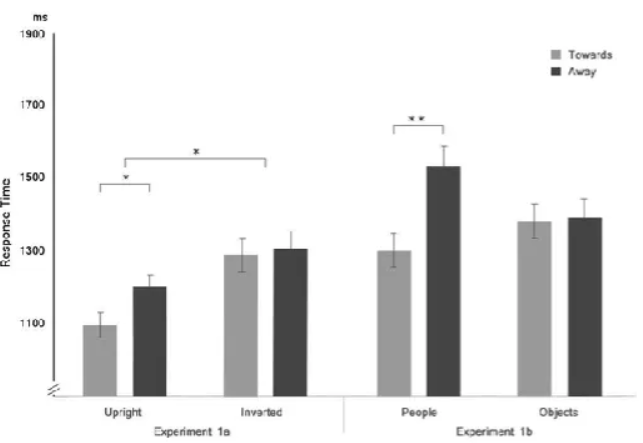

What did Vestner et al. (2019)’s results tell us about people in pairs?

Indicates that pairs of people facing each other are detected faster in visual search tasks compared to pairs arranged back-to-back.

This "search advantage" stems from a general attention orienting mechanism guided by low-level directional cues, rather than a specialized system for processing social interactions.

Participants were better at remembering all details in interacting dyads than non-facing.

BUT they were better at discriminating correct from incorrect when foils were from a different pair only for facing pairs.

Suggests pairs are remembered together when they’re seen as interacting.

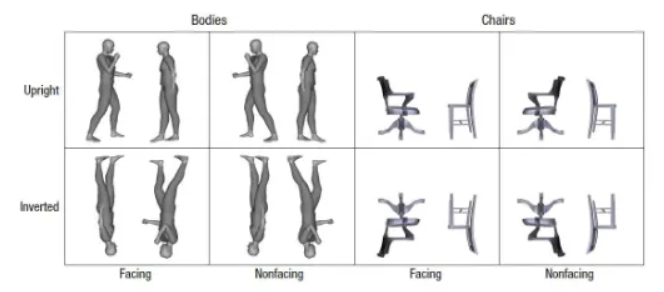

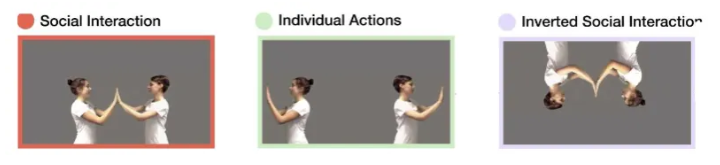

What is the two-body inversion effect?

Shows our visual system processes pairs of facing bodies as single, structured units, much like individual bodies, making them harder to recognize when inverted compared to bodies facing away, which are processed piece-by-piece.

This effect reveals that spatial relationships between bodies (specifically facing each other) trigger specialized configural processing, treating the dyad as a whole, thus showing sensitivity to upright, interacting body configurations.

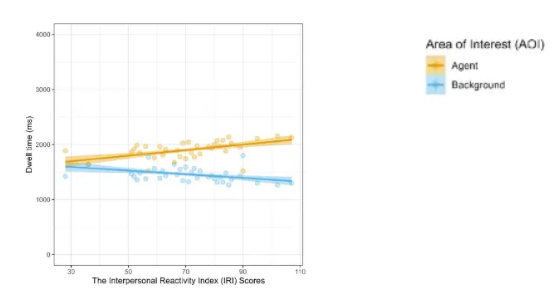

How does empathy increase focus on people in dynamic scenes?

By triggering an automatic and sustained redirection of attention toward social and emotional cues, which is driven by a shared neural representation of others' experiences.

This enhances a person's ability to interpret and respond to the social environment.

Activation of Shared Neural Circuits: When observing others, particularly in emotionally charged or dynamic situations, the same brain networks responsible for experiencing those actions or emotions firsthand (e.g., the anterior insula and frontal operculum) are activated in the observer. This "mirroring" mechanism makes the observed person's experience personally relevant, which in turn captures attention.

Prioritized Social Attention: Individuals with a high trait of empathy (as measured by the empathy quotient or Interpersonal Reactivity Index) show an attentional bias toward human figures and emotional faces compared to non-social stimuli. This suggests that social cues are given priority in visual processing.

Sustained Processing: High-empathy individuals not only initially fixate on social and emotional information but also maintain their attention for a longer duration. They are less likely to quickly disengage their gaze from an emotional face or a painful scene, allowing for more elaborate and sustained processing of the social information over time.

Information Integration: Arriving at a full empathic response in a complex, dynamic scene may require gathering multiple relevant cues (facial expressions, body posture, context) and integrating this information over time. This need for deeper social understanding motivates increased and sustained focus.

Motivational Significance: Empathy helps to assign motivational significance to social stimuli. Cues that predict an important social outcome (e.g., a partner's pain) elicit a stronger brain response related to attentive processing, effectively guiding attention according to perceived social needs and goals.

Why are interacting humans considered “special objects”?

Due to their social salience and the rich, complex information their interactions convey.

Visual attention is a limited resource, and the brain prioritizes stimuli that are most relevant for survival and social functioning.

Interactions may be viewed and processed differently than independent agents:

Facing dyads are:

Recognized as human more quickly and

Show a greater inversion effect (Papeo et al, 2017, Papeo & Abassi, 2019).

Are processed faster and remembered better (Vestner et al., 2019).

Are found and processed more quickly in visual search (Papeo et al., 2019), though this may not be specific to human dyads (e.g., Vestner et al., 2020, 2022).

Draw more visual attention (Stagg et al., 2014; Skripkauskaite et al., 2022; Daughters et al, 2025)

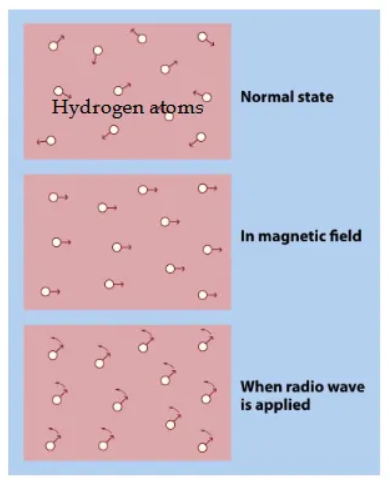

Very briefly, how does MRI work? (recap)

MRI machine applies powerful magnetic field.

Protons become oriented parallel to field.

Radio frequency (RF) pulse perturbs them.

MRI measures how long it takes protons to return to “normal state” (by detecting energy released).

Takes longer in some tissues than others

So they look different in the images

Very briefly, how does fMRI work? (recap)

Differences for functional imaging:

Focus on oxygenated vs deoxygenated blood.

More active brain area → more oxygen flowing through blood.

Oxygenated blood is less magnetic → bigger MR signal.

Measure time-course

Take image of brain every 1 -3 sec

Look at changes over time

Collect entire scan of the brain (in slices) every ~2 seconds

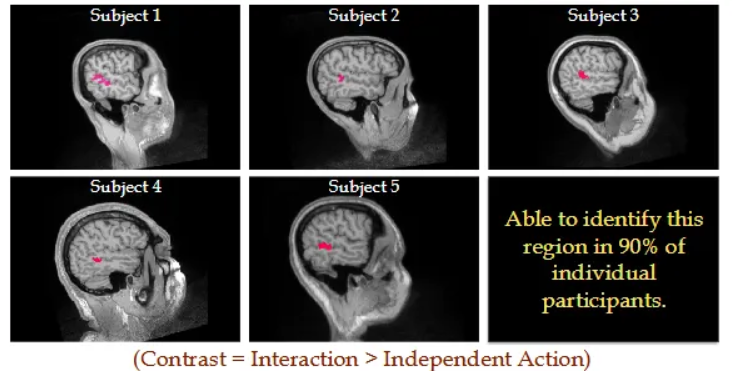

What is a brain region of interest selective for social interaction?

The posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) is a key brain region that shows robust and unique selectivity specifically for processing social interactions.

This selectivity is distinct from other social functions like face perception or theory of mind.

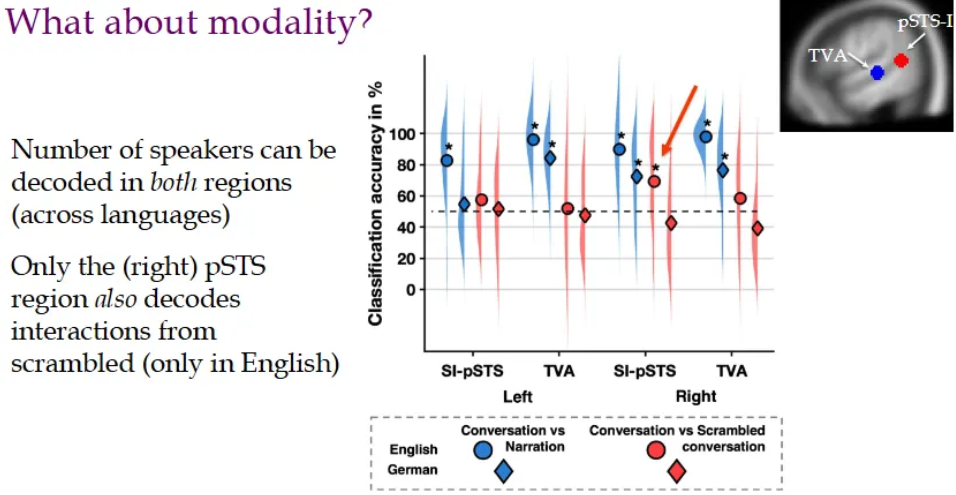

Does modality impact the responsiveness of the pSTS?

Any region that is sensitive to auditory interactions (the pSTS?) should respond more to conversations than narrations (across languages?).

Should also be sensitive to the coherence of the conversation (at least in the understood language).

pSTS is:

Sensitive to number of speaker (our big contrast)

Sensitive to coherence of interactions (our tighter contrast)

Not unequivocal evidence, but

Suggests visually defined ”interaction” pSTS area is also sensitive to interactive cues in the auditory modality.

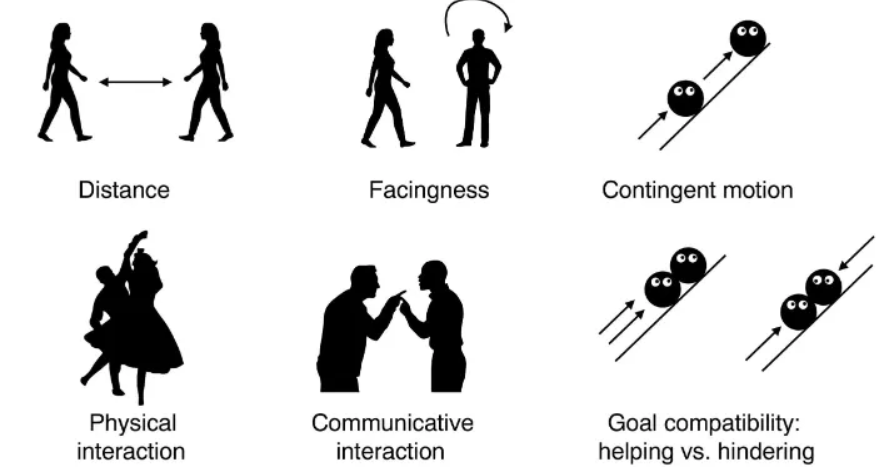

What are some key components of interactions?

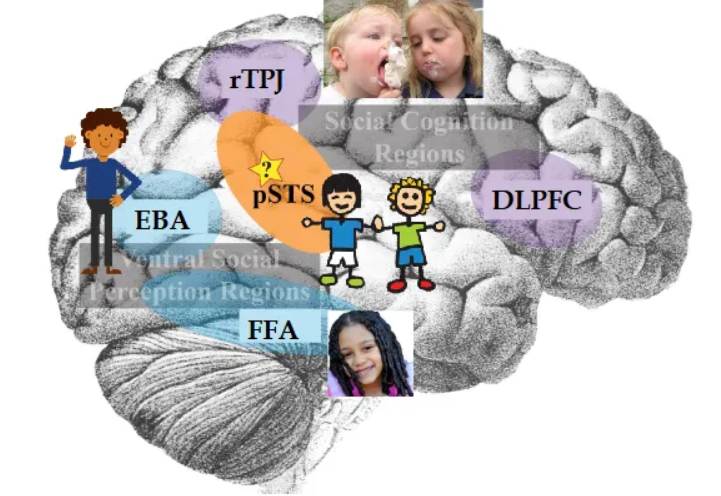

Describe the ‘visual social brain’.

Refers to specialized brain networks, particularly in the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) and occipitotemporal cortex (EBA), that process the visual cues of social interactions, like body movements, facial expressions, and eye gaze, to understand others' intentions, emotions, and mental states (Theory of Mind).

It's a key part of the broader "social brain," integrating visual perception with complex social cognition to make sense of dynamic social scenes and predict behavior, forming a unique pathway for social perception distinct from object recognition.

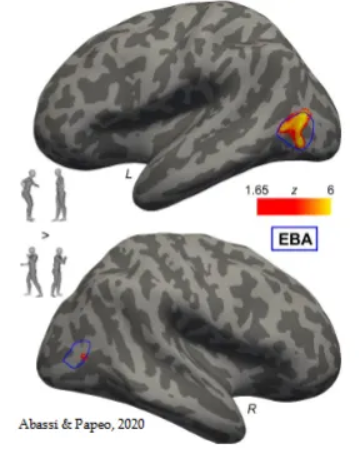

What did Abassi and Papeo (2020, 2021) find about the EBA?

Found the Extrastriate Body Area (EBA) is more uniquely engaged by static, face-to-face human interactions than the Posterior Superior Temporal Sulcus (pSTS), suggesting EBA plays a crucial role in the initial visual detection of social cues, while the pSTS is also involved but might be more sensitive to dynamic social interactions, with both regions working together in processing social scenes, with EBA often showing stronger sensitivity to body-specific interaction cues.

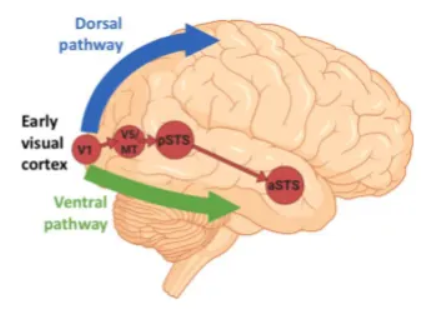

What has multivariate regression analysis revealed about the pSTS and EBA?

Revealed that the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), extrastriate body area (EBA), and middle temporal visual area (MT) are highly interconnected and collectively contribute to specialized visual processing, such as body and motion perception.

Specialized Roles in Perception:

The pSTS is strongly associated with processing human actions and social cues, such as the direction a person is walking or their intentions, and maintains representations invariant to size or viewpoint changes.

The EBA primarily encodes the facing direction of a body (e.g., whether a person in a point-light display is facing towards or away from the viewer).

The MT (or MT+) is critically involved in general motion processing and encodes the direction of movement (e.g., walking direction in point-light displays).

What is the recent proposal of a 3rd visual stream?

A recent proposal by David Pitcher and the late Leslie Ungerleider introduces a third visual stream in the primate brain, specialized for dynamic social perception.

This stream runs from early visual cortex into the superior temporal sulcus (STS) via motion-selective areas (V5/MT), complementing the two established "what" and "where" (or "how") pathways.

This new model updates the influential "two visual pathways" model (ventral "what" stream for object recognition and dorsal "where"/"how" stream for spatial processing and action) that has dominated neuroscience for decades.

While some researchers view it as a distinct pathway within the broader ventral stream, the body of evidence points towards it being a functionally and anatomically independent visual stream in its own right.

Can we confirm the role of the EBA?

Current research confirms that the Extrastriate Body Area (EBA) plays a key role in coding the spatial relationships of body parts.

It primarily focuses on processing the visual perception of the human body and its parts, as well as integrating this information with motor actions and proprioception.

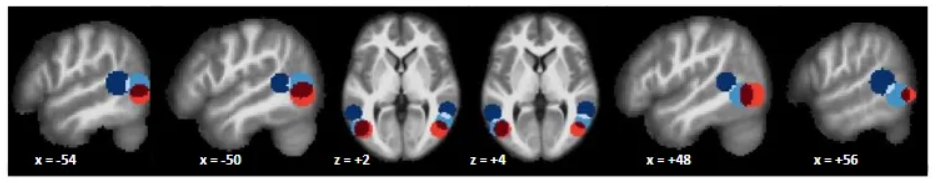

What has fMRI found about hemispheric differences between the left and right EBA?

Found that while the extrastriate body area (EBA) is present in both hemispheres, there are functional specializations, with the right EBA showing a general dominance in overall activation and processing of self-other identity, and the left EBA showing greater sensitivity to cues related to social interactions and potential action understanding.

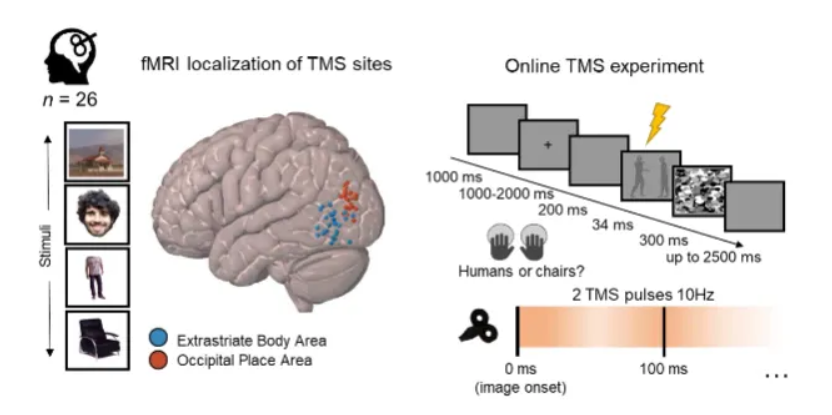

What is fMRI guided TMS?

An advanced, personalized brain therapy that uses functional MRI (fMRI) to pinpoint exact brain regions or networks involved in a patient's symptoms, then uses TMS magnetic pulses to modulate activity in those specific areas, improving balance and function for conditions like depression, anxiety, or TBI, unlike traditional TMS which uses more general landmarks.

It's a powerful tool for research and treatment, allowing scientists to see how stimulating one area affects the whole brain network in real-time.

What did TMS to the left EBA show?

Showed it causally supports processing social interactions by eliminating the two-body inversion effect (2BIE) for face-to-face dyads, demonstrating the left EBA isn't just for individual bodies but for detecting the 'unit' of interacting people, disrupting this specific social perception cue.

This confirms the left EBA is crucial for holistic processing of social configurations, beyond just body parts.

TMS effects are site specific

TMS effects are category specific

Left EBA is causally necessary for encoding facing human dyads.

How are social interactions perceived in early childhood?

Infants differentiate facing vs non-facing dyads very early (at least by 6 months).

By 14 months, selectively attend to interactions.

fNIRS evidence that dmPFC (and STC and vmPFC) preferentially process social interactions in infants (6 – 13 months).

Suggests sensitivity to interactive information develops early

Do children and adults attend to social interactions differently?

For both Children (aged 8 – 11) and Adults

Humans capture attention before other scene elements

Interactors capture attention faster

And hold attention for longer

Interaction understanding develops across childhood

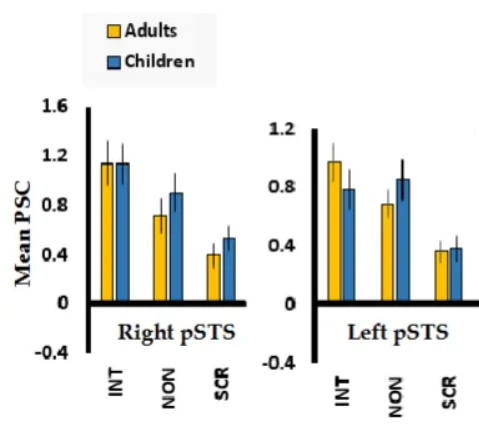

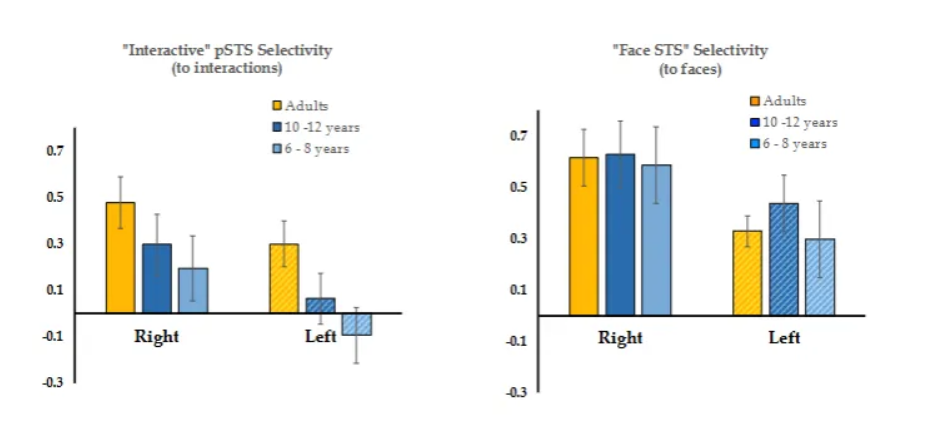

How is social interaction perception developed in the brain?

Through a network of regions, primarily the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), which selectively processes dynamic social cues like body movement, alongside areas for faces (fusiform gyrus), bodies (EBA), motion (MT+), and higher-level understanding (temporoparietal junction - TPJ).

This processing starts early in life, with the pSTS becoming increasingly specialized to interpret complex interactions (like cooperation vs. conflict) as we develop, integrating visual input to form a rich understanding of others' intentions and relationships.

Right pSTS is more selective than left.

Adults are more selective to interactions in the pSTS than children.

This difference is more pronounced in the left hemisphere.

Children show no interaction selectivity in the left hemisphere pSTS

Explain how STS selectivity changes across development.

Demonstrates early face-selective responses in infancy that become more focal, bilateral, and strongly tuned to complex social information (like social interaction and dynamic expressions) throughout childhood and adolescence.

Do adults process interactions differently?

Interactions are processed “automatically”/perceptually in adulthood

Children need a network that involves social cognitive regions

Understanding interactions becomes more “perceptual” and “automatic” across development

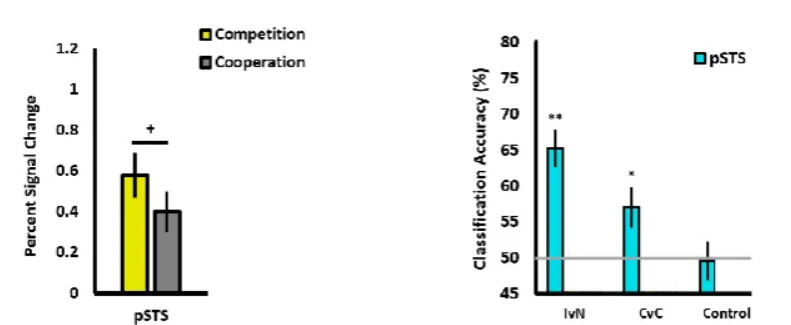

Is the pSTS sensitive to the content of interactions?

Highly sensitive to the content of interactions, representing information about intentions, emotional tone (cooperating/competing), and the goals of social exchanges, not just basic body movement.

It helps differentiate helping vs. hindering actions, processes emotional context, and integrates visual and auditory cues to understand the "what" and "why" of social interactions, making it crucial for navigating our social world.

The pSTS responds differently to competitive vs. cooperative interactions

Interaction type can been decoded in the pSTS

Give an overall summary.

Interactive information is present as early as 3

The pSTS becomes more ”tuned” and more selective across early development

One mechanism of “tuning” may include network changes

Interaction responses in STS are supported by connectivity to perceptual areas in adults and mentalising regions in children

May reflect different strategies for understanding interactions

Near ‘automatic’ inference from visual information in adults?

Children may need to use social reasoning to understand (many) observed interactions