Roman Art History Exam 2

1/47

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

48 Terms

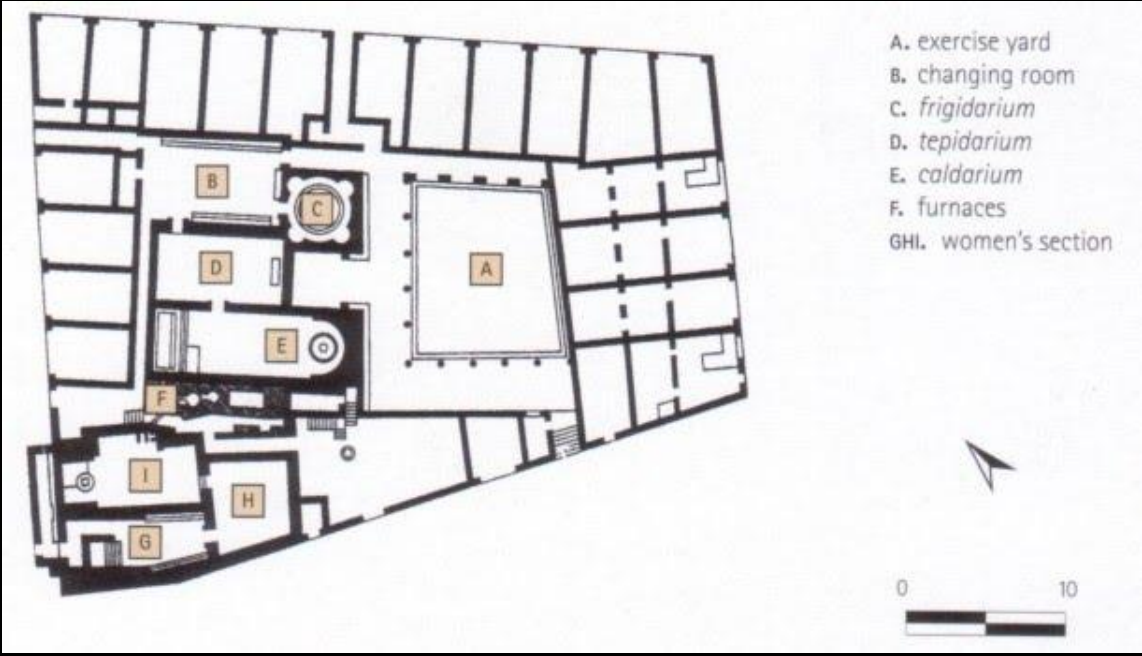

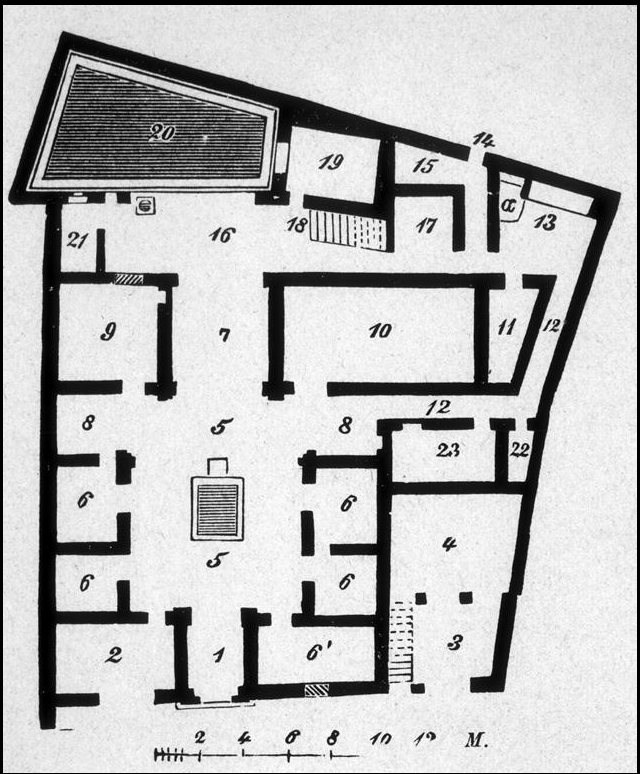

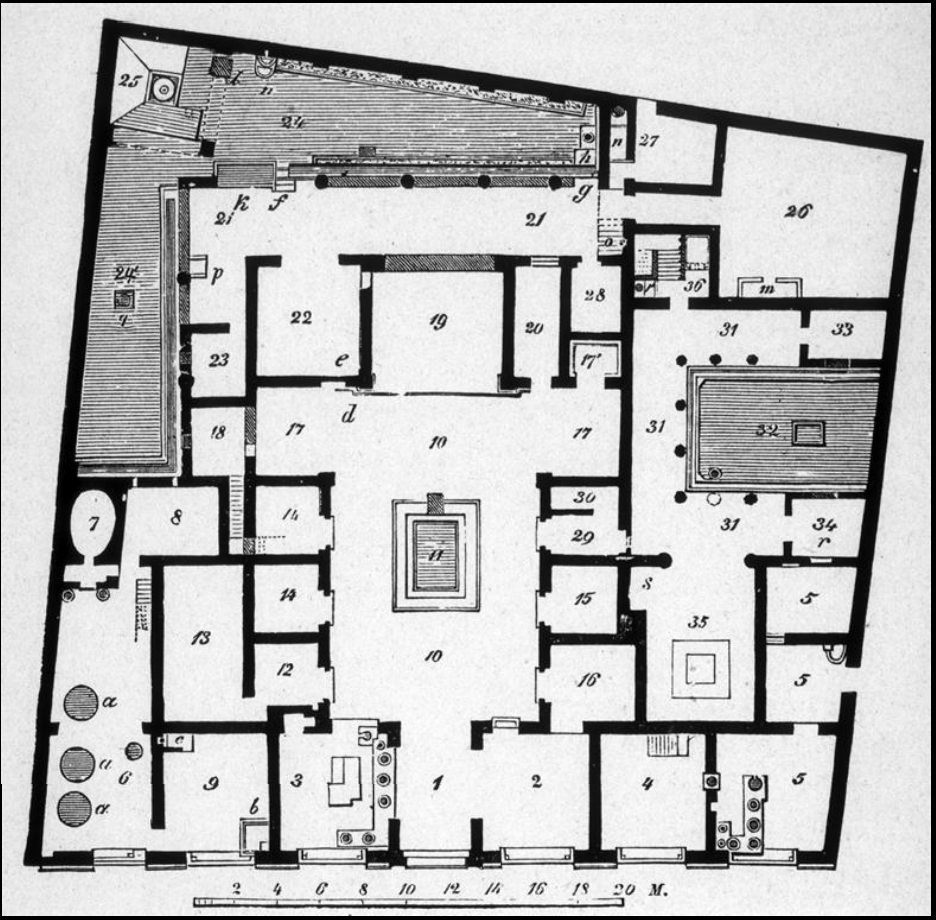

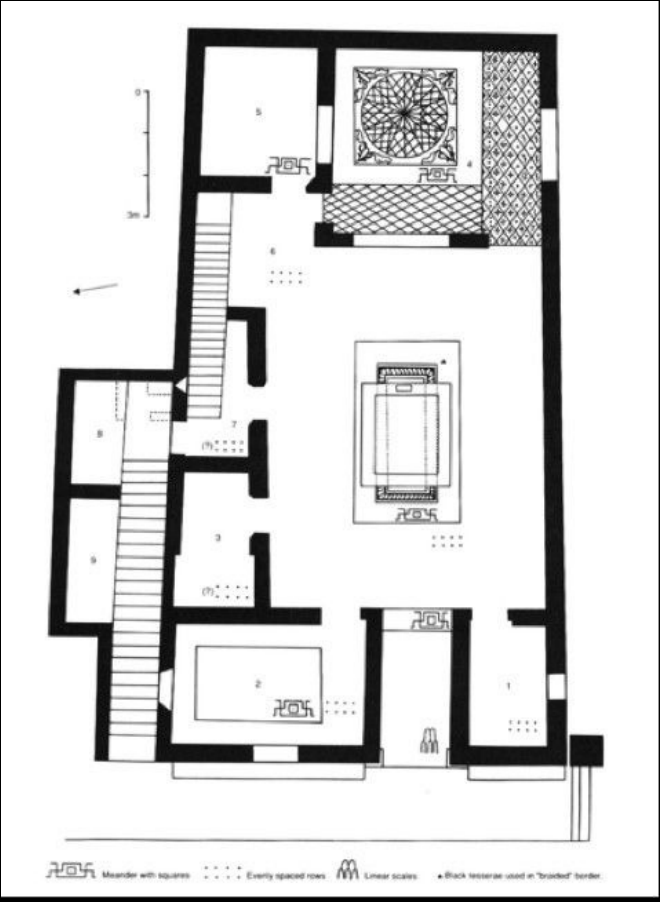

Forum Baths, Pompeii: Plan, Ca. 80 BCE - 79 CE.

Head of the goddess Sulis Minerva, Bath, England, gilt bronze, c. 75 C.E. The bath was built upon an ancient natural hot water spring. The statue depicts the syncresis of Minerva and the Celtic diety Sulis, a fusion made by the Romans. Defixiones (curse tablets) were found at the bath made out to Sulis Minerva.

Bronze statue of Lucius Marcius Grabillo, early 1st. c. CE. Found at a hot spring in San Casciano dei Begni. Striking posture and thinness (prominent ribs), arms in prayer position. Example of a votive statue––asking for healing of the objects which the state depicts (such as ears, legs, breasts, polyviscera); statues are of varying scales. Dedication of the statue to the dieties of the spring, either in thanks or supplication for healing. Lucius Marcius Grabillo offered this statue and six other statues and six legs (inscription).

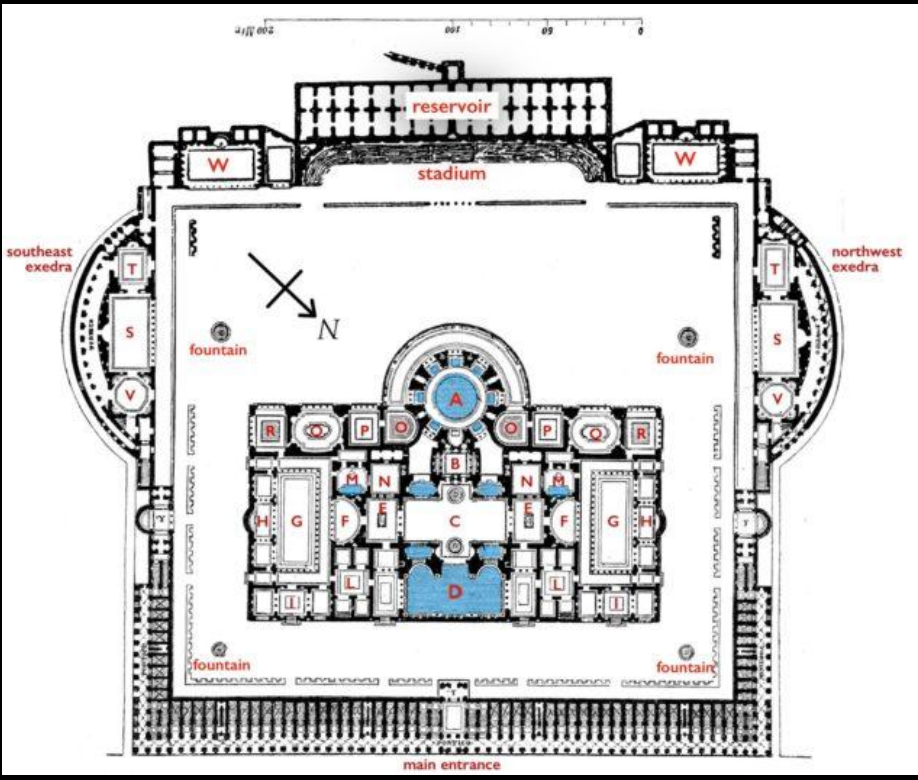

The Baths of Caracalla, marble and granite, 211-216 CE. 2nd biggest bath after Trajan (took up 60 acres of space). Axiality and symmetry of the Roman house is reflected in the baths.

Hercules Farnese “Weary Hercules,” from the Baths of Caracalla, early 3rd c. CE, copy of Greek original. Located in the entryway to the Frigidarium; Colossal; idealized muscles that “defy belief.” Depicted with attributes of older men/philosophers: beard, downward, thoughtful gaze, wrinkles in forehead, hand posed as if poised for philosophical rhetoric; shown as both an athlete and a thinker. Leaning against the skin of the Nemean lion and his iconic club; holding three apples from the Hesperides (tree of life) in the Underworld, in some traditions his last labor––physical exercise of his labors has taken a mental/emotional toll. Front: impression of weary Hercules; back: explanation of why he’s weary.

The Farnese Bull “The Punishment of Dirce,” 3rd c. BC(?). Violent punishment scene in the poleastra, probably commissinoed specifically for this space; two brothers tying a female figure to a crazed bull as a punishment for intending to murder their mother. Display of heroic, physical prowess; depicting the idea the that everyday activity of working out is akin to mythological heroes.

Achilles and Troilos Group, from the Baths of Caracalla, marble. Achilles has a killed Troilos slung over his shoulder, about to throw him over a cliff––a crime against gods and man in Roman/Greek cultures. Plays of the idea of front and back (like the Hercules statue); a theatrical approach to the spectator. Even though extremely brutal/violent, the statue still depicts Achilles in his athletic prime, and displays the physical feat of holding someone over his shoulder.

The Flavian Amphitheater / Colosseum, 70-80 CE, Rome, marble. Started by Vespasian and finished by his son, Titus; paid for by the spoils from the Jewish War. Used for entertainment/performances, and also executions. Elliptical plan, stacked seating (rank descends as seats ascend), three tiers: doric columns, ionic columns, and corinthian columns at the top.

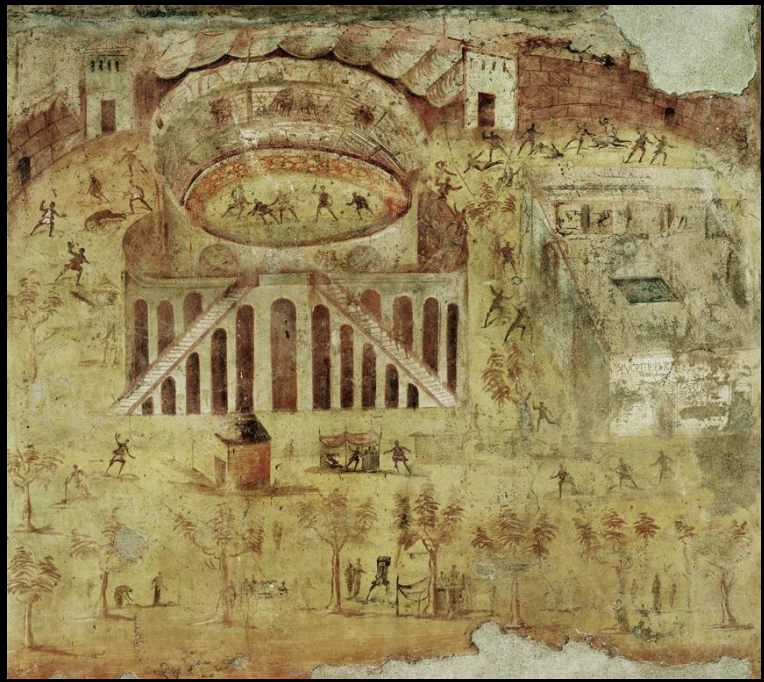

Riot in the Amphitheater, fresco fragment from garden wall, Pompeii. 59-79 CE. Depicts a fight between the inhabitants of two Roman settlements, Nuceria and Pompeii. Combination of a frontal/facade view which gives a sense of the building, combined with a bird’s eye perspective which shows the action of the scene. Less glamorous than the imperially-produced image of the bronze sestertius, focusing on the people rather than the building; a celebration of disorder, chaos, and the individual, particular memories of that day. (Amphitheater of Naples)

Flavian Amphitheater (Colosseum), Bronze Sestertius, 81-90 CE., from the reign of Titus. Bird’s eye view as well as view of the facade; emphasis on the amount of people in the Colosseum––in response to Nero’s domus Aurea, “Nero built that building for himself, and we (the Flavians) built this building for all of you,” emphasis on the collective, shared experience. Depicts a figure seated on the spoils of the Jewish War, which funded the Colosseum, asserting Roman dominance over foreign enemies. Imperial image of collective order.

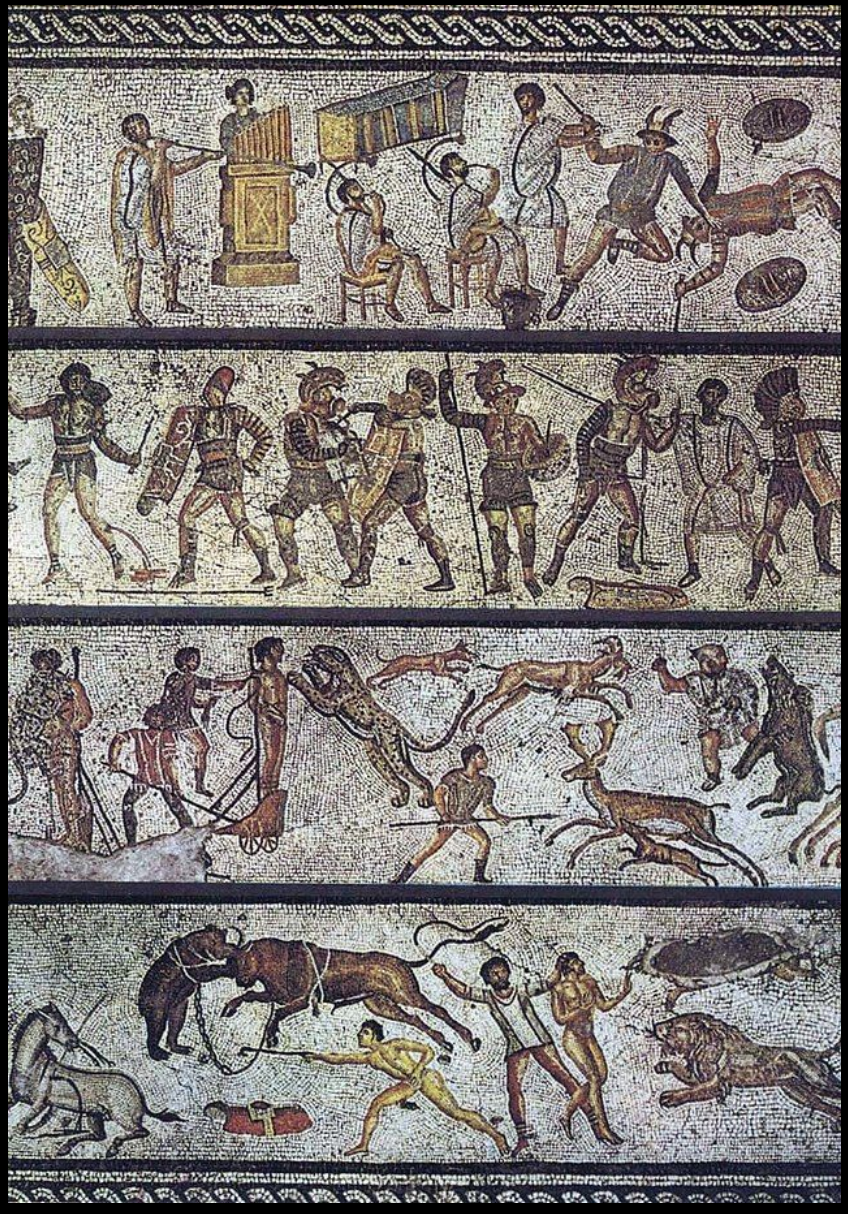

Gladiator mosaic from Roman villa, Zliten (Libya), 2nd c. CE. Depicts gladiatorial contests, animal hunts, and scenes from everyday life. The imagery of the gladiatorial games draws on military representations, i.e. the tomb of Quintus Fabius.

Gladiator mosaic from Wadi Lebda, Leptis Magna, Libya, 2nd c. CE (?). Painterly representation of mosaic: gleam of skin, detail of hair, foreshortening. Shows imagery of the arena even in the most lavish residences.

The Circus Maximus, Rome. Not until Julius Caesar that the space gets any formalized architectural elements, finished by Augustus––enclosed with stone architectural form, stone seating. Destroyed and rebuilt in 2nd c. under Emperor Trajan.

The Circus Maximus, Rome. Not until Julius Caesar that the space gets any formalized architectural elements, finished by Augustus––enclosed with stone architectural form, stone seating. Destroyed and rebuilt in 2nd c. under Emperor Trajan.

Bronze sestertius, with image of the Circus Maximus, 103-111 CE. Facade view with row of arches and upper tiers of seating, obelisk on central barrier is a prominent monument. No people represented. Distortions in the attempt to render the elongated space on the small surface of a coin. Imperial depiction of Trajan’s architectural accomplishment.

Circus Floor Mosaic, from small room/vestibule in house in Carthage, 2nd-4th c. CE. Bird’s eye view/flattened architecture to depict the action of the race. Emphasizes the importance of the spina (central barrier).

Circus Floor Mosaic, from Lyon (Roman Gaul), early 3rd c. CE.

Clay Lamp showing a chariot race, 175-225 CE. Physicality of the lamp enables the viewer to turn it around in their hands, mimicking the circular movement of the race. Portrays the action of the race, the architecture, and the crowds of people. Distorted perspective to fit as much visual information on the small surface as possible.

Funerary Relief with Circus races, from Ostia, 98-117 CE. Depicts the action of a chariot race. Honoring the couple on the left of the relief.

The Arch of Titus, Rome, ~81 CE. Originally made of Greek marble, but reconstructed with a brighter white travertine to differentiate conservation. Associated with Titus, but built by his younger brother Domitian. Located on the outside edge of the Forum Romanum, right where the triumphal procession would pass through––high visibility from elsewhere in the city, dominating the landscape. Example of a victory monument––means of inscribing victories into the landscape.

Triumph Relief (Arch of Titus), Rome, ~81 CE. Processional scene facing towards the Forum; the viewer is a part of this eternally repeating procession. Titus in the chariot, elevated above the rest (imperial art singles out the most important figure). The figure below him with bare torso is a god/non-human figure, possibly a personification of the spirit of Titus; Victory is behind the procession with outstretched wings, extending a crown of victory over the emperor’s head; personification of Rome (Roma) leads the horses, still looking back and upward at the emperor. The viewer, looking up, is assimilated into the position of Roma herself, who is subordinated to the emperor.

Spoils Relief (Arch of Titus), Rome, ~81 CE. Soldiers carrying various spoils of the Jewish War (prominent menorah, taken from the destroyed temple in Jerusalem, table with sacred implements), emphasizing the material success of the victory. They are passing through an arch themselves––probably the one that Titus built in the Circus Maximus.

Deification of Titus (Arch of Titus), Rome, ~81 CE. Central portrait of Titus in his toga riding on the back of an eagle, which is sacred to Jupiter––showing how the Flavians can even triumph over death. Demonstrates how the visual language of the triumph is now being mapped onto the language of deification––the emperor inhabits a different sphere than us, the viewers down on earth, and can make another triumph in the heavens.

Unswept Floor / Asarotos oikos (ἀσάρωτος οἶκος) mosaics, 2nd c. CE. Remnants of a feast.

House of the Vettii, Room p, (Punishment of Ixion) late 1st c. CE, Pompeian 4th style. Ixion is punished (for wanting to have sex with Hera) by being tied to a burning wheel on which he will be eternally tortured. The Vettii brothers, who were liberati, must have witnessed corporal punishment themselves––why choose to depict it in their home? The painting also celebrates their knowledge of Greek myth, and engages with questions of social hierarchies/norms.

House of the Chaste Lovers, Room g (East wall, central picture), Pompeii, 40 CE. Evoking the distant past of the Greek symposium––thinking about the Roman banquet as a version of the symposium, and celebrating this excessive behavior.

House of the Triclinium, Room r (East wall, central picture), Pompeii, 1st c. CE. Commemorates a real, specific party, rather than a mythological scene––figures seem to have recognizable, portrait-like features. Specific, possibly emotional, connection between the master of the house and the enslaved child by his side, perhaps a favorite slave of his.

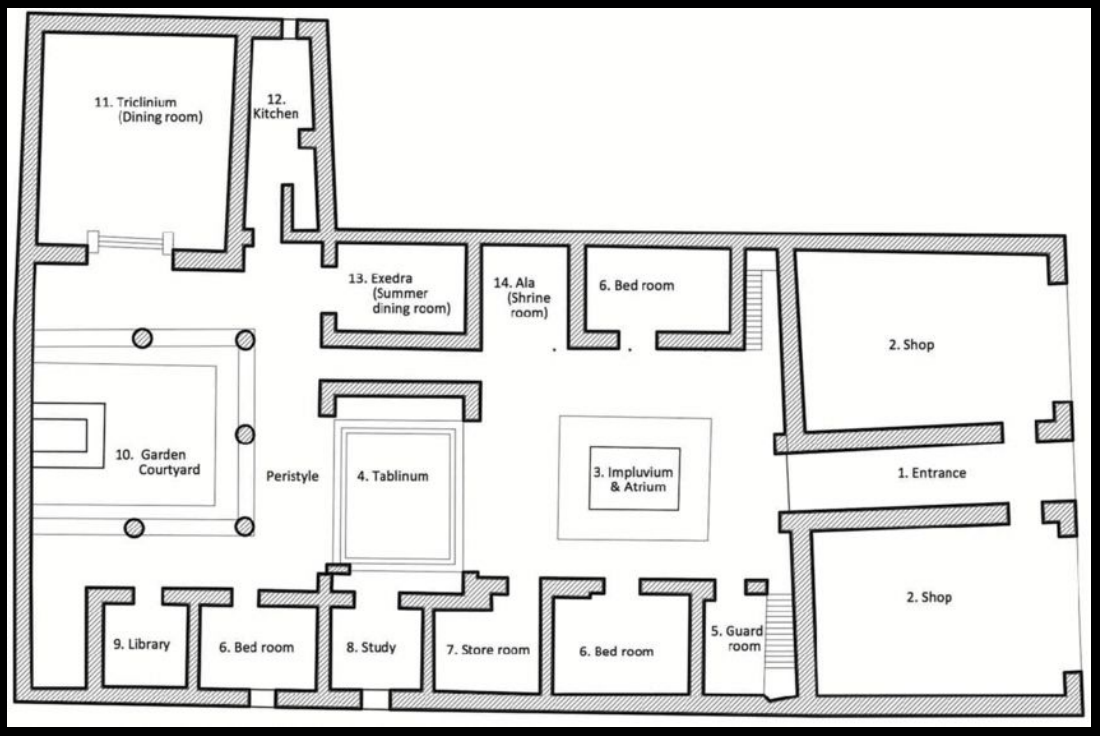

House of the Surgeon, Pompeii, 3rd c. BCE. Typical domus Italica with some irregularities.

Plan: House of Sallust, Pompeii, 4-2nd c. BCE. Central axis with many extensions; thermopolia facing the street (where one could purchase ready-made hot food; large terracotta pots set within countertops).

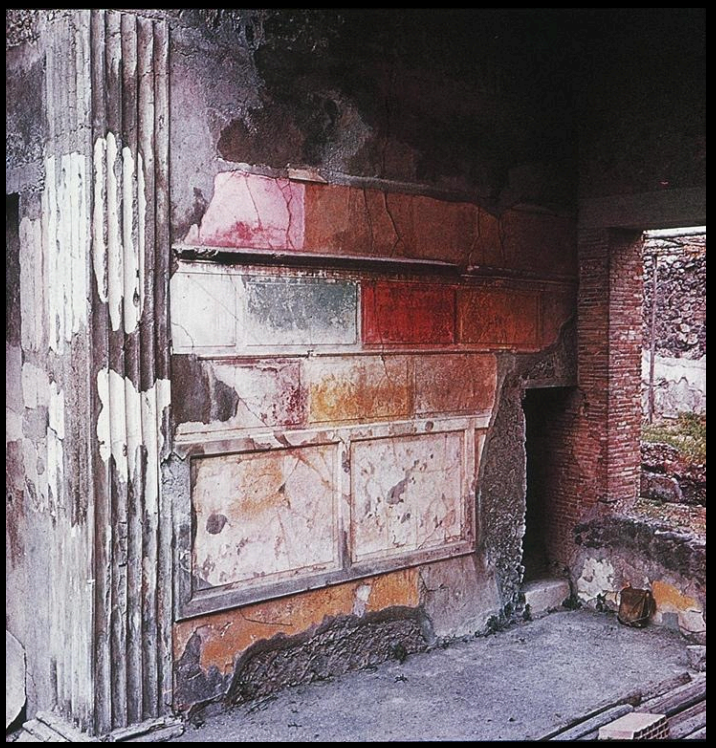

Wall Painting: House of Sallust, Pompeii, 4-2nd c. BCE. First style / Masonry/Incrustation Style. Wall divided into different registers, limestone plaster layered to look like stone masonry.

Plan: House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii, 2nd c. BCE and later. Hellenized domus––tablinium leads to a three-sided peristyle (didn’t have room for a quadriporticus). Different dining rooms for different seasons. Emphasis on axiality; the house as a stage; certain spaces are prioritized above others (i.e. the peristyle, dining rooms, atrium, rather than bedrooms). Gardens and shops are fundamental to the house.

Plan: House of the Samnite, Herculaneum, 2nd c. BCE

Painting: House of the Samnite, Herculaneum, 2nd c. BCE. 1st/Masonry style: Used stucco to build an illusion of a lattice balcony and columns in the upper level––tricking the eye into thinking the space is more grand than it is.

Plan: House of the Faun, Pompeii, 2nd c. BC. Hellenized domus that takes up an entire city block. Emphasis on the peristyles, which were spaces for otium/cultivated leisure and erudite conversations (invoking the Greek philosophers). Corinthian columns in the entryway draw on Greek temple architecture. Named after a bronze statue of a faun in the impluvium.

Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale, 50-40 BCE. Example of the Second or Architectural Style. The wall paintings depict “fantastical” architecture/cityscape; sense of receding landscape. Looking out onto prospect.

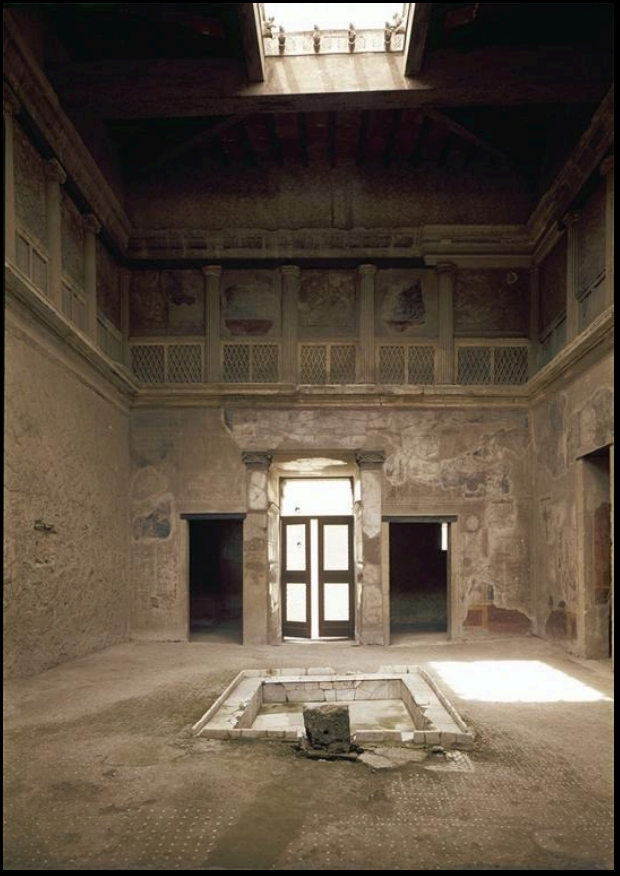

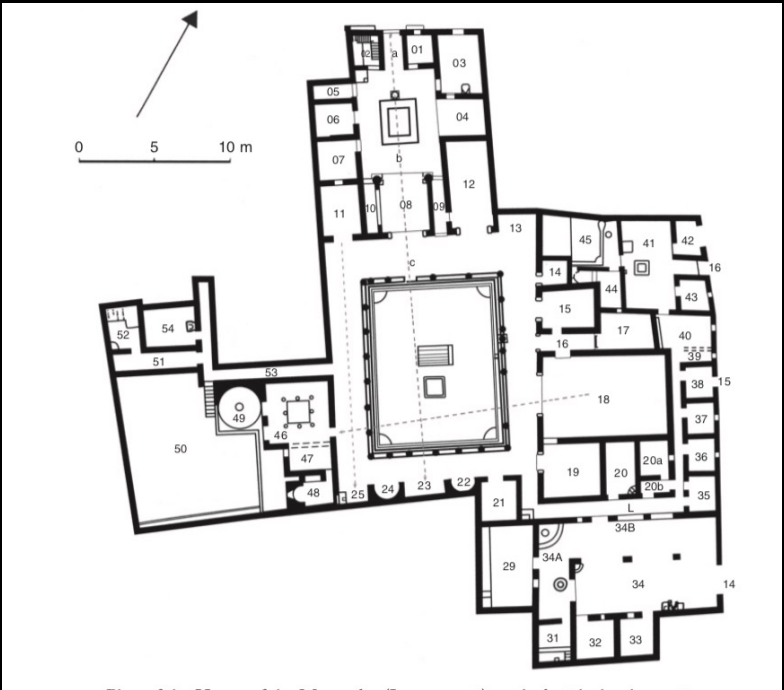

House of the Menander, Pompeii, 2nd c. BCE(?). Three primary sight lines throughout the house. Enslaved people would have navigated the space to avoid surveillance of the master/paterfamilias or because the dominos didn’t always want them in their spaces.

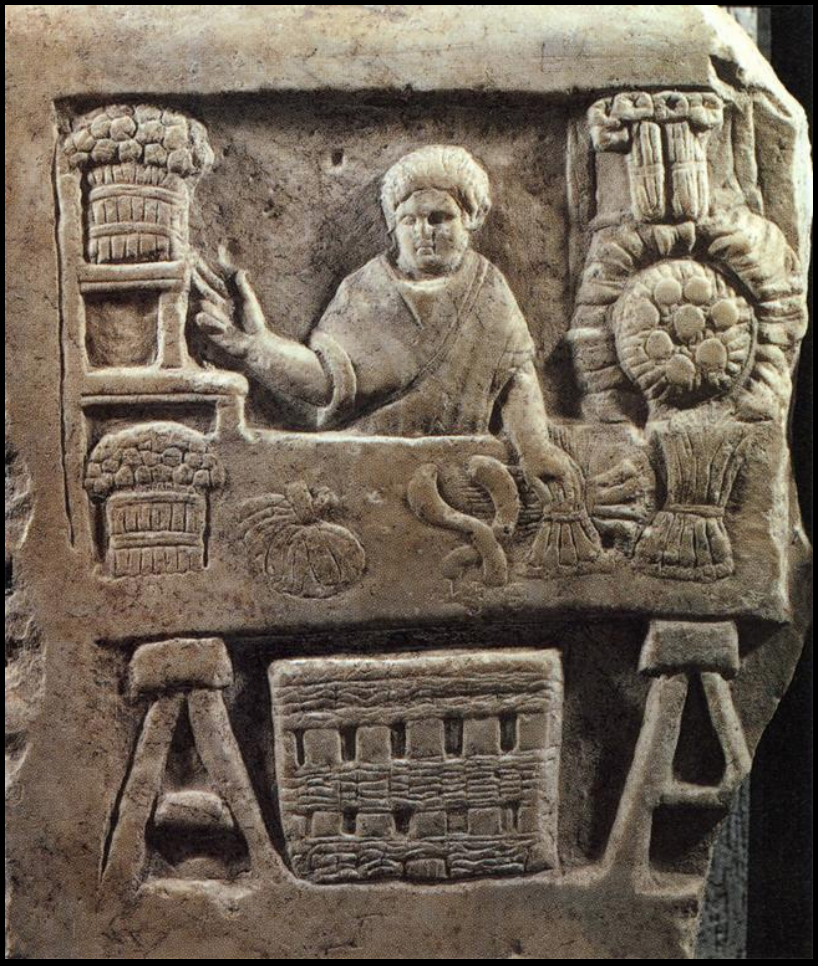

Vegetable seller relief, late 2nd or 3rd c. CE, Ostia. Rejects naturalism in order to communicate as much info as possible; spatial distortion of the table to display the food upon it. Version of appendage aesthetic––gesturing to the sale. Example of non-elites showcasing their importance/pride in their work through art.

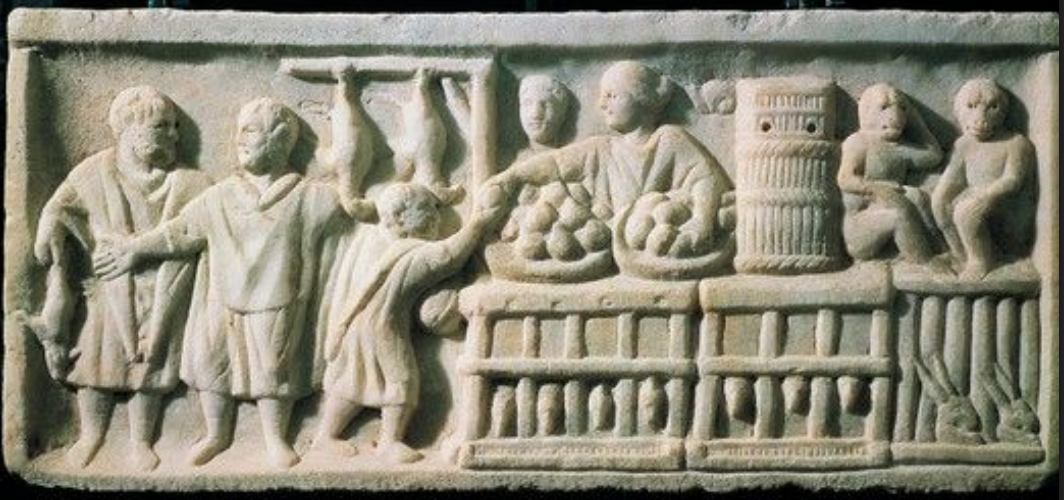

Relief with woman selling food, Ostia, 150-200 CE. Rejects naturalism in order to communicate as much info as possible. Version of appendage aesthetic––gesturing to the sale. Man and woman perhaps a couple working together to sell food. Example of non-elites showcasing their importance/pride in their work through art.

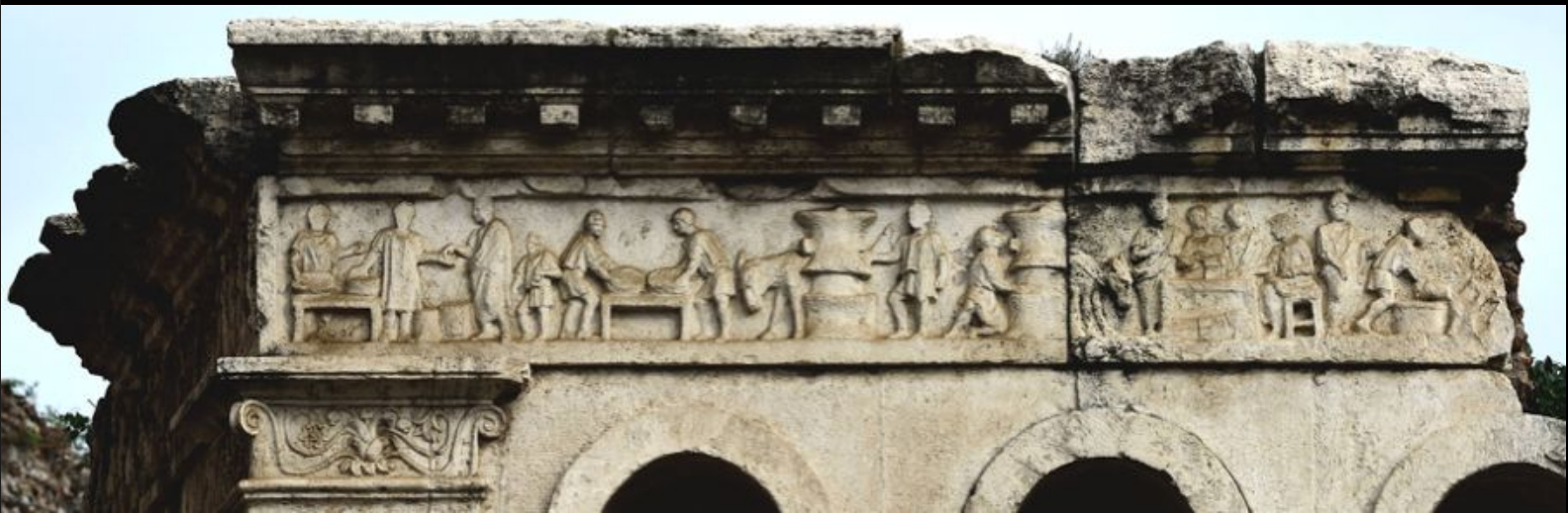

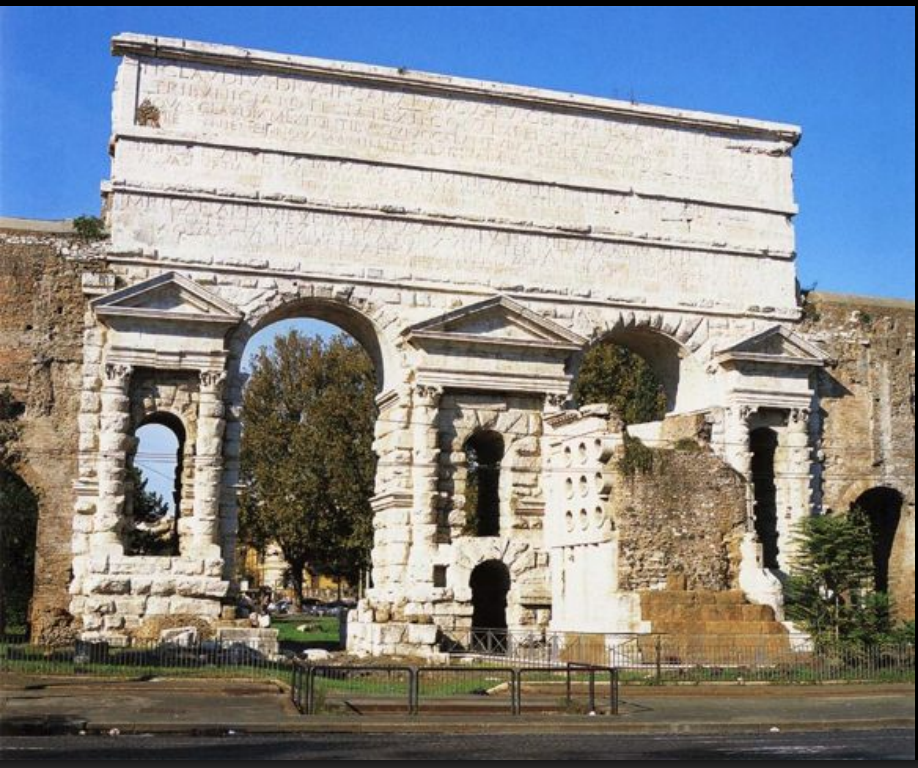

Tomb of the Baker M. Vergileus Eurysaces, Rome, 30-20 BCE, marble. Displays scenes from his industry of baking in a frieze that wraps continuously around the top of the monument, establishing longevity and commemorating all that he has supervision over. Contrast between citizen and slaves (who are doing the actual labor). Non-elites are not afraid to celebrate the dignity of their professions––putting themselves on the level of state/imperial business.

Porta Maggiore / Tomb of the Baker M. Vergileus Eurysaces, Rome, 30-20 BCE, marble. Displays scenes from his industry of baking in a frieze that wraps continuously around the top of the monument, establishing longevity and commemorating all that he has supervision over. Contrast between citizen and slaves (who are doing the actual labor). Non-elites are not afraid to celebrate the dignity of their professions––putting themselves on the level of state/imperial business.

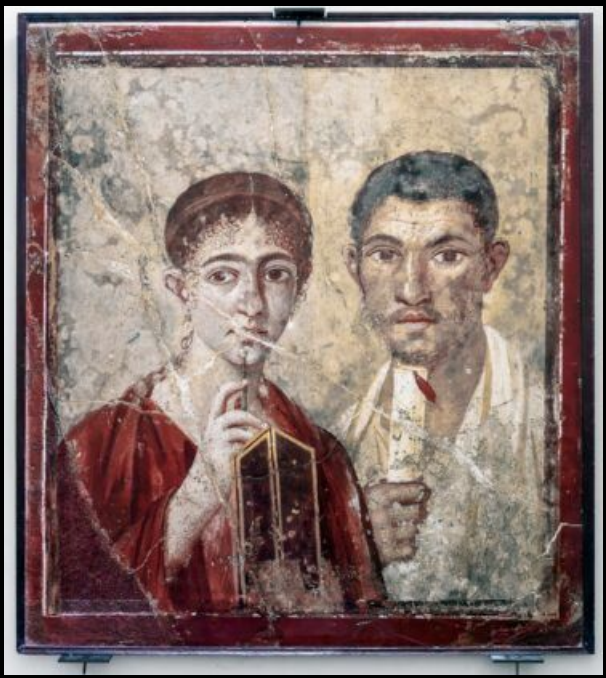

Portrait of Couple (Terentius Neo and his wife), Pompeii, 60-70 CE. The couple presents themselves as partners, holding writing utensils and possibly accounting materials, celebrating their literacy and business––they are proud of their economic enterprise. The painting is located in the tablinium, under a painting of Amor and Psyche, demonstrating that myths are things to have and think about in the home/ways to reflect yourself.

Mosaic floor, from the Hall of the Grain Measurers, Ostia, 230-250 CE. Commissioned by the grain measurers themselves; gives insight into how the workers view/present themselves. Figures are clustered around a measuring barrel for the grain, which is reflective of figures clustered around an altar in state-sanctioned art.

Subterranean Garden Room: Livia’s Villa ad Gallinas Albas at Prima Porta, 25 BCE. Underground triclinium with garden paintings. Example of the 2nd Style: the painting gives the illusion of a garden landscape through techniques such as atmospheric perspective (the elements of nature recede into the distance) and realism (movement of leaves, diff. colors on diff. sides). Bold claim of making nature artificially as good as real nature––fictionalizing the depiction: all kinds of species of plants blooming at the same time, more kinds of birds than you would see in one place (hyper nature = more diversity than real life). One caged bird retains an element of control/order in the painting.

Landscape Painting from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, 50-40 BCE. Second Style. Combination of real nature and painted nature––grotto and nature depictions on the wall with a window looking out to the landscape outside.

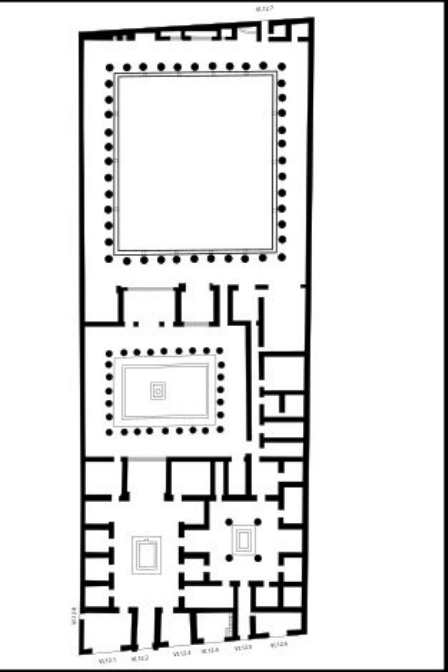

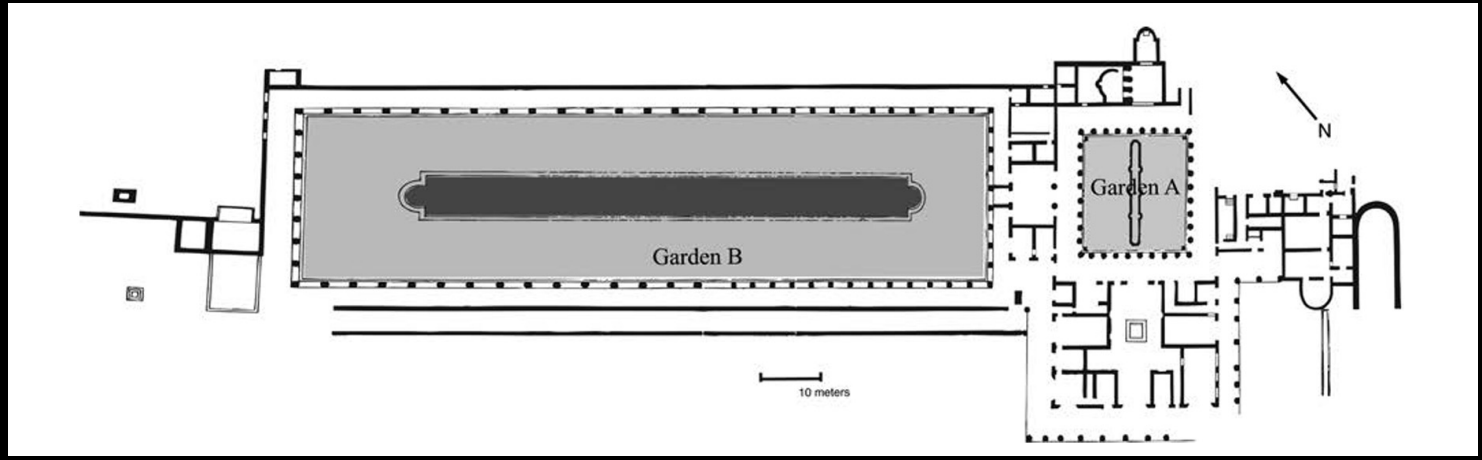

Plan: Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum, Bay of Naples, 1st c. CE. Named after its library of papyrus scrolls. Villas built to suit the wants of the owners. Incorporates different types of spaces/activities from the Greek world (intellectual discussions, religious/athletic architecture, but not political statues––the villa as an escape). Garden A = old fashioned pieces; Garden B = statues of philosophers.

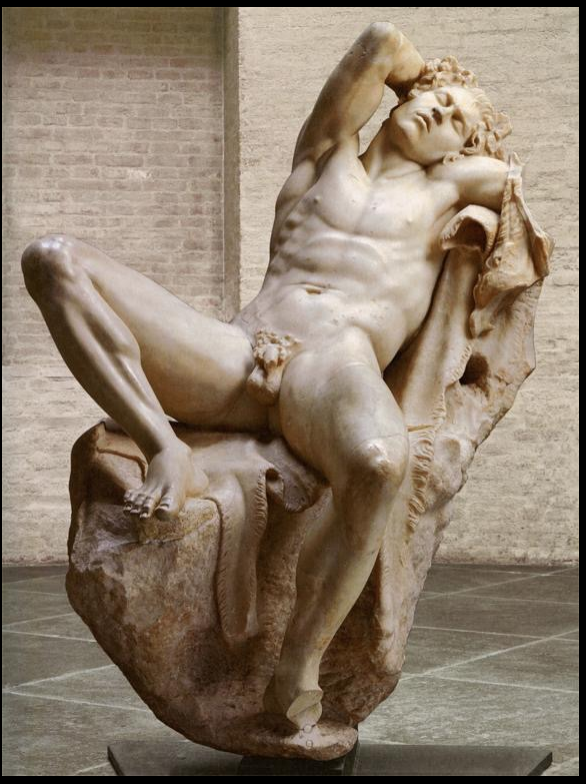

Barberini Faun (Sleeping Satyr), 3rd-2nd c. BCE, marble. Depicts a sleeping satyr (identifiable by tail, ears, leopard skin) after partying/drinking with Dionysus. Satyrs are subhuman, half-civilized and half-wild, expressing the uncultivated/barbaric qualities of human nature. Attention to detail and human anatomy; Hellenistic emotion and eroticism. A bronze copy (1st c. BCE) of the greek original was in the Villa of the Papyri.

Sleeping Eros, 3rd-2nd c. BCE. From the front, the statue appears as a sleeping toddler; from the back, the viewer gets the real sense of who it is––you never know the dangers that you could encounter in nature.

Blinding of Polyphemus, from the Villa of Tiberius at Superlonga, 1st c. CE, Hellenistic style, located in the grotto. Depicts Odysseus and his men blinding the cyclops, Polyphemus, to escape his cave. Extreme version of the Sleeping Satyr. Fitting subject to location; immersive––a lot to talk about while eating.