Session 7 - How does knowledge become legitimate in policy?

1/42

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Who produces it, who interprets it, and who decides which evidence counts?

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

43 Terms

What is knowledge?

Knowledge ≠ data: “justified-true-belief” idea, evidence is always constructed and interpreted through context

Under what does policymaking operate?

Under bounded rationality: decisions are “good enough” (shaped by limited information, persuasion, and framing)

What is the “deficit model”?

=what scientists provide and what policymakers receive —> fails

Policy systems feature multiple actors with different cognitive and institutional limits

Glyphosate regulation —> what does it reveal?

Reveals how EU decision-making oscillates between technocracy and politicisation; scientific assessment interacts with reputation, public opinion, and member-state politics

The Commission’s behaviour demonstrates the tension between expertise and responsiveness: evidence is necessary but never sufficient

Evidence co-production

Evidence 1.0 → 3.0: from linear rationality to networks of interaction, trust, and co-creation

Facts are uncertain, values in dispute, decisions urgent (Funtowicz & Ravetz)

Boundary organisations bridge science and policy, acting as “lighthouses” in a sea of information

In a post-fact, post-trust society, communication, framing, and emotional intelligence are part of evidence work

The real challenge is not data scarcity but sense-making: turning data into knowledge, and knowledge into wisdom

Stakeholder analysis

Systematically mapping who benefits, who bears costs, who influences, and who is forgotten

Distinguish stakeholders by power and interest, linking engagement method to their position

Engage early, especially in problem definition; late consultation = tokenism

Even “voiceless” stakeholders (e.g. future generations, the environment) must be represented

EU Risk Regulation and Judicial Review of Science-Based Measures

In the risk society (Beck), governance faces unknown unknowns

The precautionary principle allows action under uncertainty, prioritising health and safety over economic interest

EU agencies (EFSA etc.) embody the institutionalisation of expertise

Comitology shows the hybrid of technocracy and politics in executive rule-making

Courts as informational catalysts: judges ensure that decisions rely on adequate, transparent evidence, enhancing procedural integrity without usurping expert judgment.

Knowledge in Policy Making: Gender Mainstreaming

Knowledge is never neutral (gendered and intersectional perspectives reveal whose experiences count as “evidence.”)

Gender mainstreaming embedding equality across the policy cycle (define–plan–act–check)

Intersectionality exposes the partiality of “universal” knowledge

Gender budgeting translates abstract equality into operational criteria

Ignoring difference produces poor policy

“What counts as knowledge” —> the politics of expertise

There isn’t one truth waiting to be ‘used’

Policy always starts with contestation over what knowledge is legitimate

EBPM:

is aspirational

must be understood through policy theory (not technocratic illusion)

Politics of evidence part II

Evidence 3.0 —> institutional systems and translation

Evidence lives inside institutions—think of how ministries, agencies, and think tanks filter it

Being critical means seeing how “bounded rationality” and routines shape what gets through

Participation —> legitimacy and power

Participation is not decorative: it’s the social negotiation of legitimacy

We study it to see whose voices are amplified/silenced when “the evidence” is built

Part III

The production and governance of data: the National Statistics case

What counts as knowledge when decisions must be made fast and uncertainty is extreme?

A live example of regulating under uncertainty:

NSIs had to reinvent their institutional routines to stay relevant (e.g. Italy’s Istat using Twitter data, France’s Insee using mobile data)

The case illustrates Evidence 3.0: the blending of public, private, and experimental data streams in institutional settings

But this adaptation is uneven, innovation clashed with legal, ethical, and procedural limits showing that institutional capacity defines what kind of evidence can be used

Risk regulation and judicial review

Uncertainty and risk regulation —> the limits of rational control

Cairney reminds us: policy is made under uncertainty and ambiguity, not just lack of data

That’s why regulation is also about values, not only models

Inclusion and equality —> the normative turn

Evidence that ignores equity isn’t neutral…it reproduces bias

Our last session closes the circle: “good” evidence must serve inclusive, anticipatory governance

What did we learn in this course?

To think systematically: what anticipatory governance calls for (=the capacity to explore and shape futures through inclusive, reflexive, evidence-informed processes)

Introduction to Anticipatory Governance

Anticipatory governance: rather than simply reacting to problems once they arrive, governments are setting up strategies to make policies that are forward-looking

—> institutions actively explore, shape, and respond to emerging futures

Anticipatory Governance

Three key dimensions:

Foresight and weak-signal detection —> being alert to changes in technology, society, environment and values before they become full-blown issues

Institutional capacity and innovation —> building the mechanisms, governance structures, and experimental labs that allow action in the present to influence those futures

Inclusion, reflexivity and legitimacy —> ensuring that multiple voices are involved, that assumptions are challenged, that policy is adapted as new data come in

Strategic Foresight —> what is it?

=a structured way to explore possible futures

What is the purpose of foresight?

To anticipate change, shape strategy, improve resilience

Foresight is different from prediction

It’s about preparing today for different futures that might or might not materialise

What are some types of foresight tools?

Horizon scanning

Scenario planning

Deplhi

What two types of futures can be considered?

Exploratory approach

Normative approach

Exploratory approach

Aims to analyse areas of uncertainty and possible developments

Expands the range of future factors or circumstances considered

Builds awareness of uncertainty and long-term trends

Answers the question: “What could happen?”

Helps identify potential risks and opportunities

Stakeholders contribute to collective intelligence, signal uncertainties, and stimulate open dialogue

Normative approach

Helps identify desirable futures and outline strategic paths to reach them

Answers the question: “What future do we want to build?”

Stakeholder involvement focuses on building consensus on goals and trajectories

Are these two approaches mutually exclusive?

No, they can be used in sequence (e.g. exploration and then norm-setting)

Caution about these two approaches

The exploratory approach may lead to decision paralysis if it generates too many alternatives

The normative approach may limit exploration by prematurely narrowing choices

—> it is crucial to be transparent about the nature of the exercise at every stage

What are the three challenges for embedding foresight in public administration?

Futures Literacy

Legitimacy

Capacity and Resources

Futures Literacy

Difficulty translating foresight outputs (scenarios, horizon scanning, megatrends) into actionable policy inputs

Difficulty communicating not only the outputs but also the role of foresight

Risk of focusing too narrowly on technical tools and methods

Legitimacy

Administrative cultures are not used to managing uncertainty/inter/transdisciplinary approaches

Difficulty positioning foresight within established evidence hierarchies/evaluating the robustness of its data.

Limited involvement of political representatives

Capacity Resources

Shortage of time and resources

Foresight often disconnected from actual decision-making processes

What is the overarching challenge?

To make foresight a rooted, legitimate, and widespread institutional practice — in other words, institutionalised — that supports an anticipatory governance culture

Institutionalisation of Strategic Foresight in Public Administrations

Institutionalisation = A process of innovation through which an initially novel or “foreign” tool gains stability and intrinsic value (Lippi, 2025)

To understand institutionalisation paths, we must distinguish between:

the application of foresight methods/techniques

the institutionalisation of foresight as an embedded administrative practice within the policy cycle

In this second sense, attention shifts from individual tools to organisational configurations that carry and embed foresight as usable knowledge within institutions

Possible Organisational Configurations

Strategic Foresight Units

Dedicated and recognisable foresight units within ministries or government departments

Tasks: conduct foresight exercises (megatrends, horizon scanning), liaise with parliaments, and provide training

Embedded or Diffused Foresight

Foresight integrated across the policy cycle as an administrative capacity

Used to test interventions, identify risks/opportunities, and design anticipatory policies

Reinforces the adaptive capacity of the entire governance system

—> These models are not mutually exclusive — hybrid forms often coexist within the same context (De Vito 2025)

Mechanisms Supporting Institutionalisation

To institutionalise foresight, administrations need to activate enabling mechanisms:

Establishing foresight units or focal points

Promoting collaboration, knowledge sharing, and incentives (behavioural change)

Training and competence development

Linking foresight to existing governance functions and mechanisms

Overcoming scepticism through foresight champions

Developing futures literacy via “learning by doing”

Bridging the technical–political divide

Using foresight as a knowledge exchange and learning mechanism

Ensuring multi-level governance interactions (across national, regional, and local levels)

Foresight in Policymaking

With strategic foresight, Governments identify strategic dependencies well before realising, i.e, that Europe lacks the necessary components to produce vaccines/chips for car manufacturing/batteries for EVs —> However, there are risks involved; it's important to avoid speculation and risky bets regarding potential future scenarios

Including specific foresight exercises in every impact assessment, evaluation, or consultation could mitigate the risk of diverging directions and ensure greater consistency. (Simonelli, Iacob 2021)

Foresight in IA is beneficial in broadening the perspectives in policy development, assessing options against scenarios, and dealing with key uncertainties by modeling the causality behind them (Radaelli, Taffoni 2022)

The paradox

Everyone is calling for more foresight in governments, but few ask how it should be used, particularly as a source of evidence

—> Can foresight be recognised as a legitimate form of evidence?

—> What conditions increase its credibility and usability?

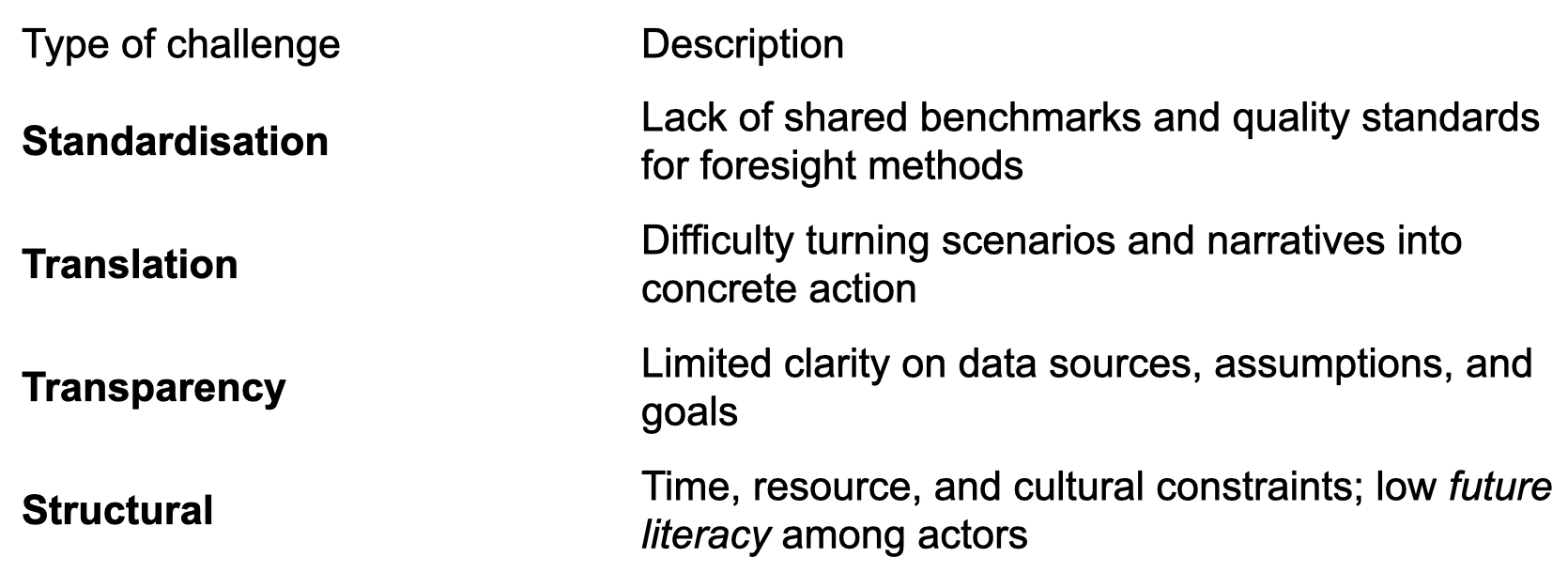

The four “classic” challenges of using evidence

Standard challenge – the hierarchy of evidence

Translation challenge – adapting knowledge to context

Transparency challenge – recognising the social construction of evidence

Structural challenge – organisational and institutional barriers

So, to recap, what makes good evidence?

It is valid for its context and policy goal, draws on mixed methods, and is:

Usable —> translatable into policy choices

Reliable —> methodologically sound and transparent

Foresight inherits these challenges — but reframes them

Foresight evidence is future-oriented —> It doesn’t measure what has happened, but explores what might happen

What are foresight’s distinctive features?

Uncertainty

Participation

Methodological plurality

Reflexive value

—> It creates anticipatory, not predictive evidence

The uniqueness of foresight-generated evidence

Through participatory methods (e.g. horizon scanning), foresight creates a distinctive type of evidence

Public officials and stakeholders become co-creators of knowledge, not just end users

Participation itself becomes a source of new knowledge

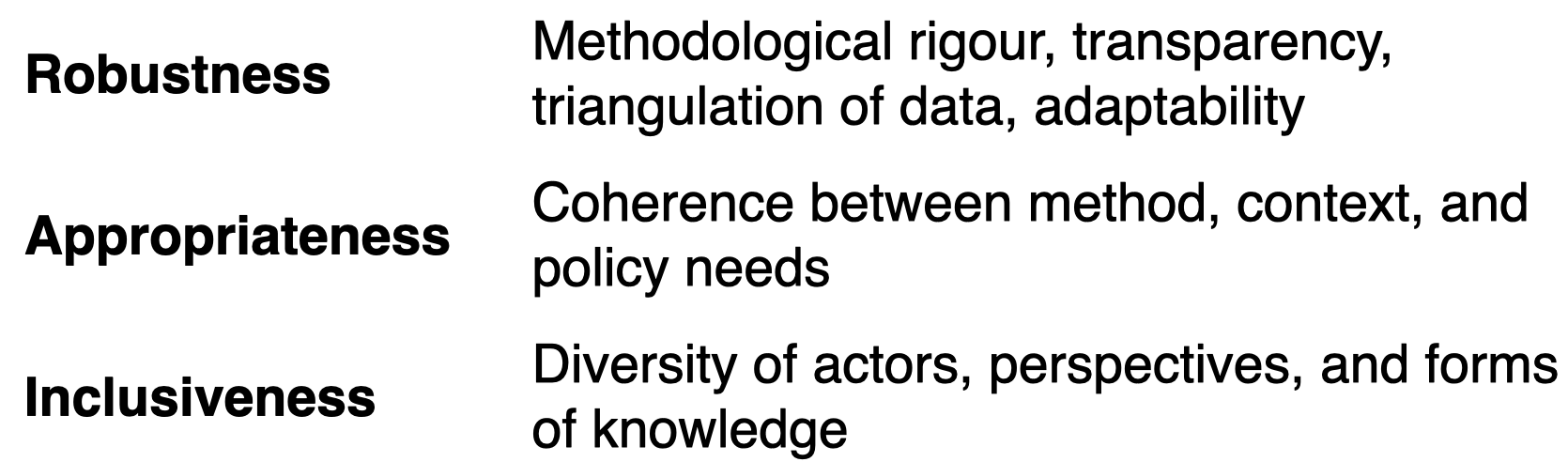

Enabling factors and their meaning

Two Cases

UK GO-Science “Net Zero Society” (2023)

Robustness: detailed methodological description, mixed modelling, iterative public dialogues

Appropriateness: practical instructions for use, stress-testing, concrete tools

Inclusiveness: limited but transparent representation of participants

EU Policy Lab & ESPAS Horizon Scanning

Robustness: iterative exercises, peer review, open “Futurium” archive

Appropriateness: unclear guidance on use and target audience

Inclusiveness: procedural, with variable composition and ongoing interaction with policy officials

Implications for policymaking

Strategic foresight does not replace other evidence forms — it complements them

—> It generates valuable knowledge when:

There is transparency about limits and intended use

It builds future literacy among policymakers

It is embedded in a wider ecosystem of knowledge, not as a one-off exercise

What is foresight not about?

Foresight is not about predicting the future… it’s about expanding the cognitive and temporal horizon of public decisions