OB First: Exam 3

1/213

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

214 Terms

Pediatric Hematologic Considerations

Production of blood cells begins at 8 weeks in utero.

The fetus receives iron (Fe) through the placenta from the mother.

Erythropoietin is primarily delivered from the liver in the fetus; the kidneys take over after birth.

Three types of normal hemoglobin are present at birth:

Adult hemoglobin (Hgb A and A2): Present in utero and predominates around 2 months after birth.

Hemoglobin F: Predominates at 8 weeks of gestational age, decreases to 70% by birth, and disappears by 6–12 months of age.

Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Etiology & Risk Factors

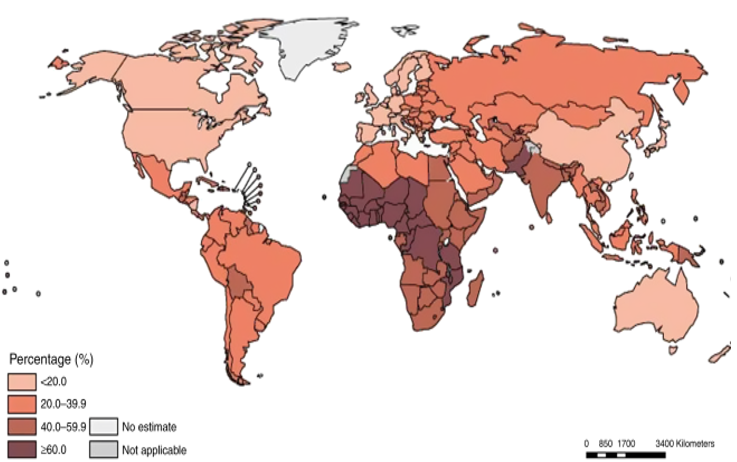

It is the most common nutritional disorder in the world, with its prevalence being higher in developing countries.

Occurs when the body does not have enough iron to produce hemoglobin.

Risk Factors:

Prematurity or low birth weight

Exposure to lead

Exclusive breastfeeding beyond 4 months of age without iron supplementation

Cow’s milk consumption without adequate iron intake

Low socioeconomic status

Recent immigration from a developing country

Use of medications that interfere with iron absorption (e.g., antacids)

Etiology:

Dietary deficiency

Impaired absorption

Increased requirement

Chronic blood loss

Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Diagnostic Criteria

For children 6 months to < 5 years:

Ferritin < 15 micrograms/L and

Hemoglobin < 11 g/dL

For children 5 to < 12 years:

Ferritin < 15 micrograms/L and

Hemoglobin < 11.5 g/dL

Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Clinical Manifestations & Assessment

Usually has no symptoms in mild cases; can cause growth retardation in prolonged (chronic) cases.

Reported Symptoms May Include:

Irritability

Headaches

Weakness

Shortness of breath

Dizziness

Pallor

Fatigue

Less Common Symptoms Include:

Pica

Muscle weakness

Unsteady gait

Difficulty feeding

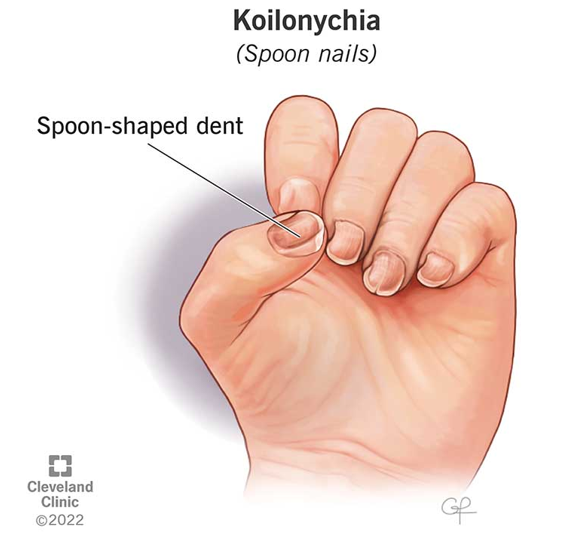

Nursing Assessment Should Include Obtaining a Good History in Addition to the Following:

Inspect mucous membranes and skin for pallor.

Assess for spooning of the nails.

Auscultate for a flow murmur.

Assess the spleen for splenomegaly.

Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Nursing Interventions

The goal is to determine and treat the underlying cause.

Encourage breastfeeding mothers to increase their daily intake of iron; if formula-fed, encourage fortified formula.

Cow’s milk intake for children > 1 year of age should be limited to less than 24 oz/day.

Effects of Cow’s Milk on Iron Absorption:

Cow’s milk makes it harder for the body to absorb iron.

It prevents the digestive tract from absorbing iron from foods.

Consuming too much can interfere with their intake of iron-rich foods, potentially leading to iron deficiency anemia, as milk is not a significant source of iron while providing a large volume of liquid that can displace other important nutrients in their diet.

It is crucial to ensure toddlers are eating a balanced diet with enough iron-rich foods alongside their milk intake.

Education & Collaborative Care:

Educate, educate, educate! Collaborative care with caregivers.

Medication Considerations:

Avoid NSAIDs; treat aches/pain with Tylenol.

NSAIDs can cause GI bleeding, irritation, and iron loss.

NSAIDs are not given before the age of 6 months due to platelet dysfunction, immature kidney function, and increased risk of GI complications.

Iron Supplementation:

Recommend iron supplementation for infants beginning at 4 months of age.

3-6 mg/kg/day, best taken 1 hour before meals to enhance absorption.

Stool Changes: Warn caregivers that stools may appear black in color.

Constipation: May occur—encourage increased fluid and fiber intake; a stool softener may be needed.

Administration: Place drops behind teeth (use a straw for older children) to prevent teeth staining.

Sources of Iron

Heme Sources:

Beef/chicken liver

Beef

Chicken

Turkey

Tuna

Crab

Halibut

Pork

Shrimp

Non-Heme Sources:

Iron-fortified cereals

Iron-fortified oatmeal

Soybeans

Lentils

Kidney beans

Lima beans

Black-eyed peas

Navy, black, and pinto beans

Spinach

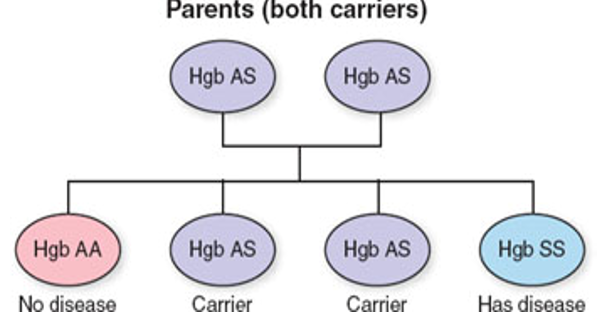

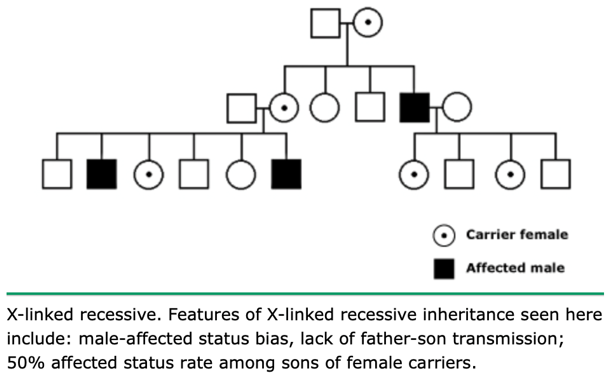

Sickle Cell Disease: Etiology

Inherited hemoglobinopathy (autosomal recessive)

Vaso-occlusive phenomena and hemolytic anemia are the clinical hallmarks of this disease.

Three Most Common Types:

HbSS (homozygous)—symptoms are the most severe

HbSC—another specific defect causing deficiency and structural variation but with milder features.

HbS beta thalassemia

_____________________________________________________________________

Both carriers—25% chance of offspring with the disease.

Hemolytic anemia—RBCs are destroyed faster than they are made (hemolysis).

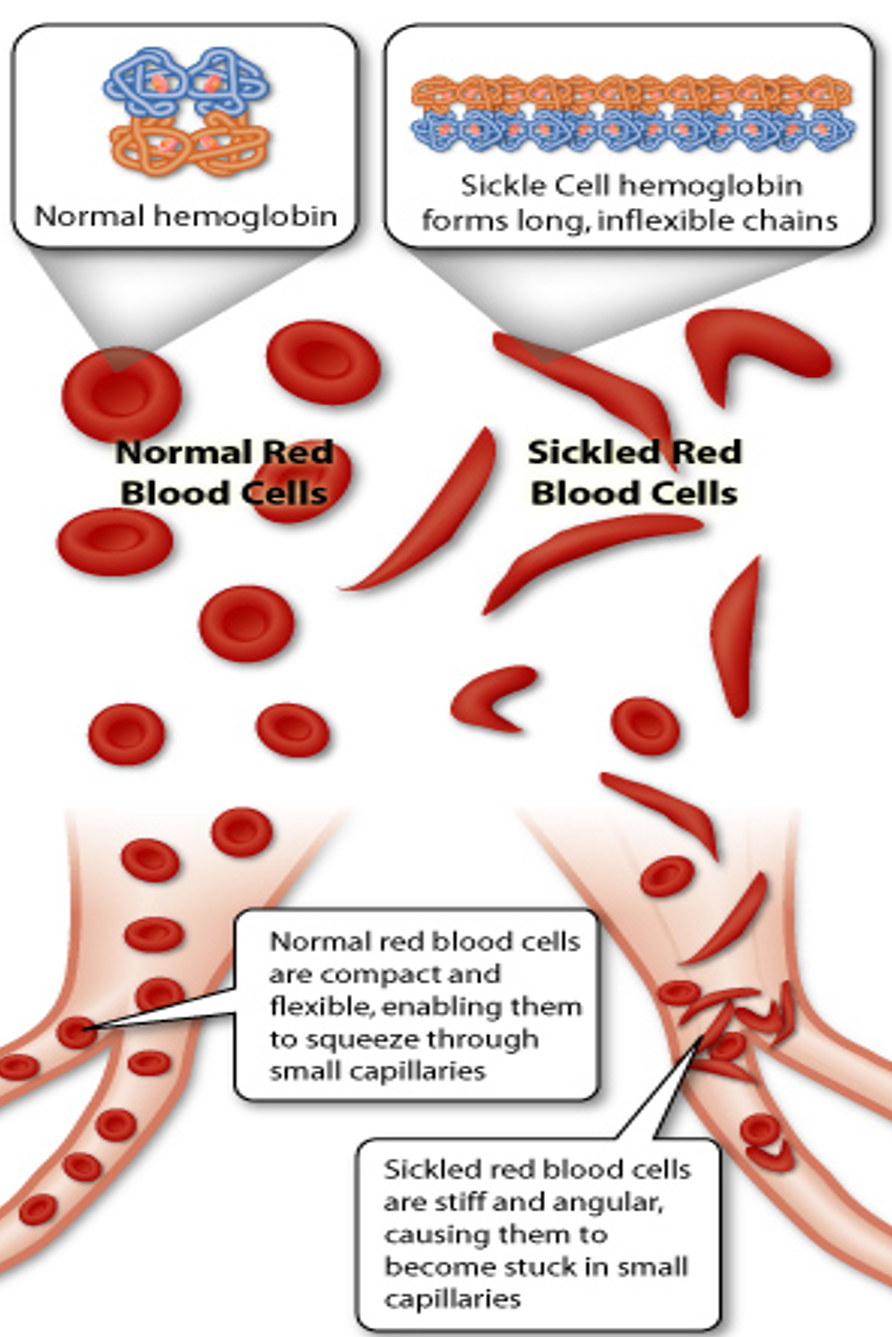

Normal RBC vs. Sickled RBC

Normal RBC:

Round shape

Soft/flexible—to allow laminar flow of blood

Average lifespan of 120 days

Sickled RBC:

Crescent shape

Sticky/rigid—inhibits laminar blood flow

Average lifespan of 20 days

Mechanism of Vaso-Occlusion

Stress/trauma (triggering event) → sickling of RBCs → increased blood viscosity → RBCs cannot pass through capillaries/venules → local tissue hypoxia → ischemia → infarction.

Assessment and early intervention are key to preventing ischemia and infarction.

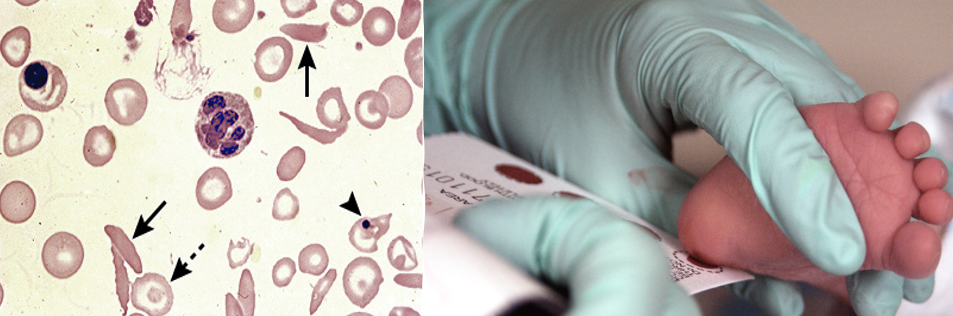

Sickle Cell Disease: Diagnostics

Electrophoresis confirms the diagnosis of SCD.

Assessed on newborn screening in all 50 states.

Does not distinguish between SCD and SCT.

Sickle Cell Disease: Nursing Assessment

Skin: Pallor, breakdown, lesions, ulceration, and jaundice (due to breakdown of RBCs—hemolysis)

Oral Mucosa: Pallor, dry/cracked

Auscultation: Murmur, adventitious breath sounds

Palpation: Warmth/tenderness/ROM joints, abdominal tenderness, organomegaly

Vital Signs: Fever present, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension

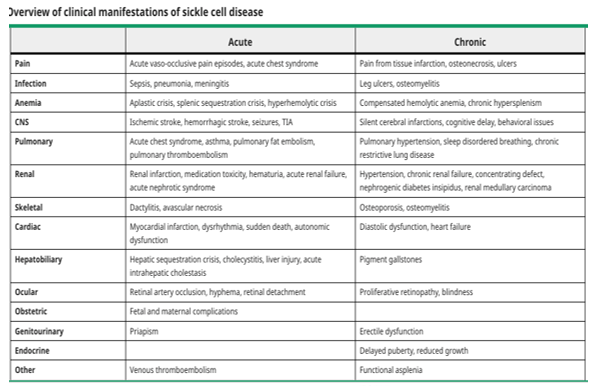

Sickle Cell Disease: Complications & Clinical Manifestations

Sickle Cell Disease: Dactylitis

Severe swelling that affects the fingers and toes—called sausage fingers.

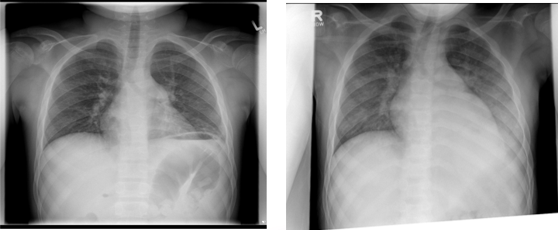

Sickle Cell Disease: Acute Chest Syndrome

A severe lung complication of Sickle Cell Disease.

Creates a pneumonia-like illness and is one of the leading causes of morbidity, hospitalization, and death in children and adults living with Sickle Cell Disease.

Sickle Cell Disease: Splenic Sequestration

Red blood cells get trapped and block the blood vessels leading out of the spleen, causing severe anemia.

This causes the spleen to get larger and blood counts to drop extremely low due to trapped cells in the spleen; painful and life-threatening.

Crisis: death can occur within hours—high mortality rate.

The spleen can hold up to 1/5 of the body’s blood supply at one time, so this can lead to CV collapse.

Anemia → hypovolemia → shock.

Usually occurs between 4 months and 3 years.

Educate on trauma prevention and non-contact sports.

Treatment:

Blood transfusions

Emergency splenectomy.

Sickle Cell Disease: Nursing Care

Prevention:

Vaso-occlusive crises

Infection

Hydroxyurea:

Helps with making RBCs bigger, rounder, and more flexible (less likely to become sickle-shaped).

It does this by increasing a certain type of hemoglobin (Hgb F), also called fetal hemoglobin, because it is found in newborn babies.

Managing Sequelae:

Pain management

Treat underlying condition

Increase fluid requirements (1.5-2x MIVFs)

No ice packs! (may use heat!)

Education & Support:

Signs and symptoms of vaso-occlusive events

Health maintenance with PCP and specialist

Medication administration

Genetic testing

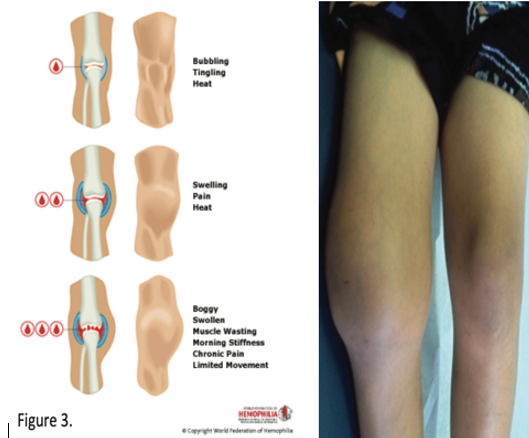

Hemophilia: Pathophysiology

A disorder of "secondary hemostasis," where fibrin clot formation is too unstable to adequately stop bleeding.

Factor VIII (8) and Factor IX (9) both play key roles by assisting in the formation of a fibrin clot.

A defect in either of these factors prevents secondary hemostasis by causing the fibrin clot to be "jelly-like" and unstable → delayed clotting → spontaneous bleeding.

Hemophilia: Etiology & Epidemiology

Hemophilia A:

X-linked recessive disorder.

Inherited deficiency of factor VIII.

Most common hereditary disease associated with life-threatening bleeding.

Occurs in 1 in 4,000 to 1 in 5,000 live male births.

½ to 2/3 of people have a severe form of this disease.

Hemophilia B:

X-linked recessive disorder.

Inherited deficiency of factor IX.

Also called Christmas Disease.

Occurs in 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 30,000 live male births.

1/3 to ½ of people have a severe form of the disease.

_______________________________________________________________________

Females may rarely be affected (affected father + carrier mother; genetic mutation) and usually have milder forms.

There is no racial or ethnic predilection for the disease.

Higher incidence in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life (likely due to having a milder diagnosis, so delayed onset of bleeding).

Hemophilia: Clinical Manifestations

Patients with a severe form of this disease are more likely to have spontaneous bleeding, severe bleeding, and an earlier age for bleeding episodes to occur.

Patients with a mild to moderate form of the disease may only have bleeding in response to injury/trauma or surgery.

Immediate or delayed bleeding after trauma is common:

This has decreased with prophylactic use of factor replacement.

Bleeding can be severe acute blood loss or oozing over several days.

Infants: Common bleeding sites include—extracranial sites (cephalohematoma), heel stick, venipuncture, and circumcision sites.

Children: Bruising and joint bleeds are more frequent when ambulation begins, forehead hematomas.

Older Children/Adults: Common bleeding sites include—joints, muscles, GI tract, CNS, mouth, and nares.

Hemophilia: Nursing Care

Prevent & Educate:

Provide prophylactic factor when ordered.

Protect toddling children with helmets/kneepads, soften/cover corners.

Regular exercise and activity to strengthen joints and muscles.

Avoid activities with a high likelihood of injury.

Good oral hygiene to prevent gum/dental disease.

Teach the caregiver how to administer factor replacement.

Educate the patient and family on when to seek expert care.

Manage Bleeds:

Administer factor replacement and/or desmopressin as ordered (slow push).

Apply pressure to areas of external bleeding.

If bleeding is inside a joint → ice/cold compress and elevate the injured extremity—may need a splint.

AVOID NSAIDs—can give Tylenol for pain if needed.

Provide Support:

This is a lifelong illness.

Should wear a medical alert bracelet/necklace.

Refer to support groups—National Hemophilia Foundation.

Help provide resources for the financial strain of the diagnosis.

Pediatric Immunologic Considerations

Immature immune systems cannot communicate well.

Decreased exposure to antigens.

T-cells may become sensitized to antigens that cross the placenta.

Produces only trace amounts of immunoglobulins:

IgG is acquired transplacentally from the mother.

IgG reaches adult levels around 7 years of age

Breast-fed infants acquire maternal immunity via passive transfer in breast milk.

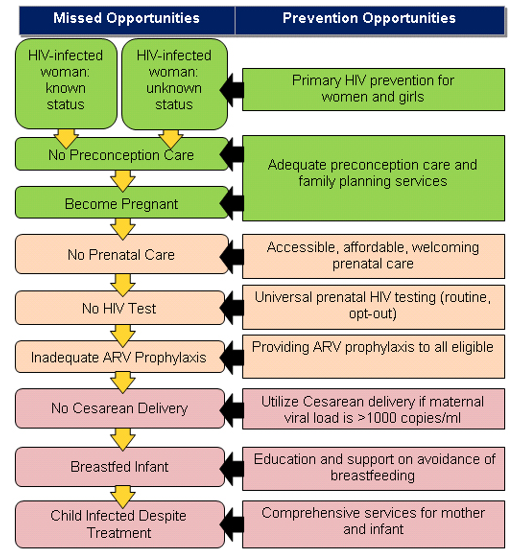

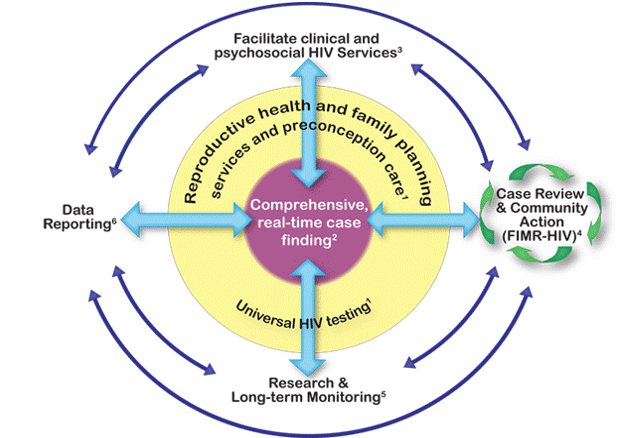

HIV: Epidemiology

The number of developing countries has dramatically decreased due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) prevention.

It remains a challenge in developing countries.

In 2018, 1.7 million children were living with HIV or AIDS:

90% in sub-Saharan Africa

Of the 770,000 people who died of AIDS-related illnesses worldwide in 2018, approximately 15% were under the age of 20 years.

Exposure Occurs Through:

Sexual contact

IV drug use

Infected blood products

Vertical transmission

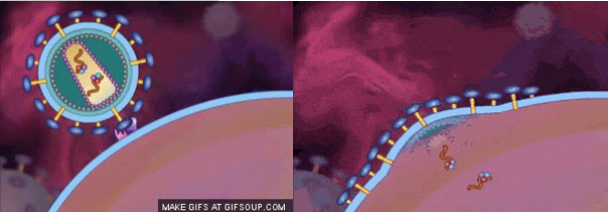

HIV: Pathophysiology

Exposure → virus infects CD4 (T helper) cells → rapid replication → cell dysfunction occurs.

It is detectable in regional lymph nodes two days after exposure and in the plasma within 3 days. Once the virus enters the blood, widespread dissemination to the organs occurs.

Immune suppression increases susceptibility to pathogens, both ordinary and opportunistic.

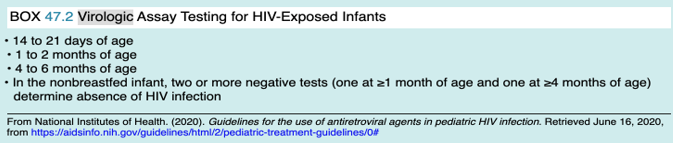

HIV: Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis should be prompt, as infants infected with HIV have a high morbidity and mortality if treatment with antiretroviral therapy is delayed.

Enzyme-linked immunoassay & Western Blot:

Detect transplacentally transferred maternal HIV antibodies until 18 months of age.

Virologic Testing for Infants <18 Months:

Utilizes assays (nucleic acid amplification) that detect HIV DNA/RNA.

Repeat testing is routinely needed, as sensitivity increases with time.

HIV: Clinical Manifestations

Acute (Early) Phase:

Fever

Lymphadenopathy

Sore throat

Rash

Myalgia/Arthralgia

Diarrhea

Headache

Chronic Infection (without AIDS):

Fatigue

Night sweats

Generalized lymphadenopathy

Persistent oropharyngeal or vulvular candidiasis

HSV, HPV, Varicella

Oral hairy leukoplakia

HIV: Nursing Care

Prevention & Education:

Provide antiretroviral (ART) to infants born to mothers until 6 weeks of age.

Prophylactic Care Following Diagnosis:

Infection prevention

Immunizations

Regular PCP and specialist visits

Health Promotion & Support:

ART compliance

Nutrition supplementation as needed

Support groups, counseling

[HEME LECTURE] Kawasaki Disease: Etiology & Epidemiology

Etiology is unknown:

Immunologic response, infectious etiology, genetic susceptibility.

Boys are affected more commonly than girls.

80% to 90% of cases occur in children < 5 years of age.

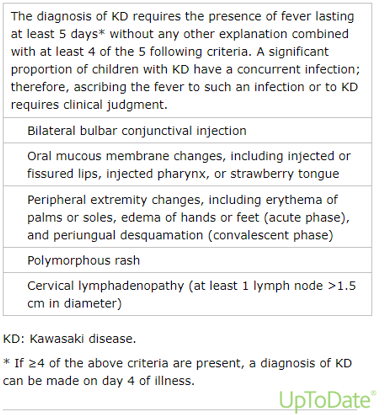

[HEME LECTURE] Kawasaki Disease: Diagnosis & Clinical Manifestations

Signs and symptoms reflect widespread inflammation of medium-sized muscular arteries that carry blood throughout the body.

Commonly leads to inflammation of the coronary arteries, which supply oxygen to the heart.

Often do not present at the same time; randomized order of appearance.

Fever in association with mucocutaneous inflammation.

Usually self-limited, treatable, and resolves in 2 weeks.

Complications:

Coronary artery abnormalities

Long-term: heart failure, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias

[HEME LECTURE] Kawasaki Disease: Signs & Symptoms

A child usually will have a fever greater than 102.2°F (39°C) for 5 or more days and at least 4 of the following signs and symptoms:

A rash on the main part of the body or in the genital area.

An enlarged lymph node in the neck.

Extremely red eyes with a thick discharge.

Red, dry, cracked lips and an extremely red, swollen tongue.

Swollen, red skin on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, with later peeling of skin on fingers and toes.

The symptoms might not occur at the same time, so it's important to let your child’s healthcare provider know about any signs or symptoms that have gone away.

Other signs and symptoms that might develop include:

Abdominal pain

Diarrhea

Irritability

Joint pain

Vomiting

[HEME LECTURE] Kawasaki Disease: Nursing Care

Administer IVIG:

Most effective when given in the first 7-10 days.

Single infusion over 8 to 12 hours.

Administer Aspirin:

Usually, we do not give aspirin due to Reye Syndrome, but in this disease, it is one of the rare occasions when we do have to give it to children.

High doses of aspirin might help treat inflammation.

Aspirin can also decrease pain and joint inflammation.

The aspirin dose will likely be lowered once the fever has been gone for 48 hours.

Clinical Monitoring:

Will be on a cardiac monitor.

Signs and symptoms of cardiac dysfunction:

Tachycardia

Gallop

Muffled heart sounds

Arrhythmias

Comfort Measures:

Control fevers

Moisturize lips

Cool liquids/popsicles

Caregiver Education:

Monitor fevers at home

Follow up with PCP and cardiology

No live vaccines until at least 11 months after IVIG

Flu vaccine (due to risk from Reye syndrome from aspirin intake)

Malignancy in an Adult Patient

Epithelial tissue; carcinoma.

Environmental exposures are a primary component of carcinogenesis in adults.

Involves organs.

Screening mechanisms may detect early cancer development (mammograms, Pap smears, colonoscopies, low-dose CT scans, etc.).

Development is strongly influenced by environmental and lifestyle factors (80% preventable).

May have a long latency period (>20 years).

Metastasis is less often present at diagnosis.

Malignancy in a Pediatric Patient

92% of childhood cancers (sarcomas, leukemia, and lymphoma) develop from primitive embryonal tissue.

Cellular growth and development are central to the mechanism of cancer in children.

Involves tissues.

Most often discovered incidentally.

Development is not significantly influenced by environmental and lifestyle factors.

Relatively short latency period.

Metastasis is often present at diagnosis.

More responsive to treatment than adult cancers.

Detecting Pediatric Cancer

Difficult to detect early on, as most pediatric cancers have signs and symptoms with an insidious onset and are non-specific, resembling symptoms of more common pathologies.

85% of pediatric cancers have associated signs and symptoms at presentation, while the remainder are cancers with unusual presentations (certain tumors) and are more difficult to diagnose at presentation.

It is vital to obtain a thorough history in any child suspected of having cancer, ask pointed questions surrounding the chief complaint/HPI, and capture a complete ROS.

Ex: Different cancers have signs and symptoms that make them easier to detect early on versus later:

The average time to diagnosis is 2 to 5 weeks for neuroblastoma, 3 to 5 weeks for acute leukemias, 7 to 10 weeks for lymphomas, 8 to 15 weeks for bone tumors, and 8 to >20 weeks for brain tumors.

Detecting Pediatric Cancer: Early Warning Signs

Unexplained pallor and loss of energy.

Unusual lump, mass, or swelling.

Sudden, unexplained weight loss.

Unexplained fever or illness that doesn’t go away.

Easy bruising or bleeding.

Prolonged or ongoing pain in one or more areas of the body.

Limping or refusal to bear weight.

Frequent headaches, particularly in the morning and associated with vomiting.

Sudden eye or vision changes.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

Blood Cancer

Most common childhood malignancy.

Five times more common in children than acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Non-familial; children with Trisomy 21 are at increased risk for developing this cancer.

Cause:

Immature lymphoblasts replace normal cells in the bone marrow → bone marrow cannot maintain RBCs, WBCs, and PLTs → Pancytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia).

Signs & Symptoms:

60% of patients present with hepatomegaly/splenomegaly.

50% of patients present with fever.

50% of patients present with lymphadenopathy.

Petechiae.

Musculoskeletal pain.

Fatigue.

Weight loss.

Diagnostic Tests:

Peripheral blood smear.

Bone marrow biopsy.

Flow cytometry.

LP to rule out CNS involvement.

Management:

Chemotherapy.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in higher-risk patients, preferably with an HLA-matched sibling donor.

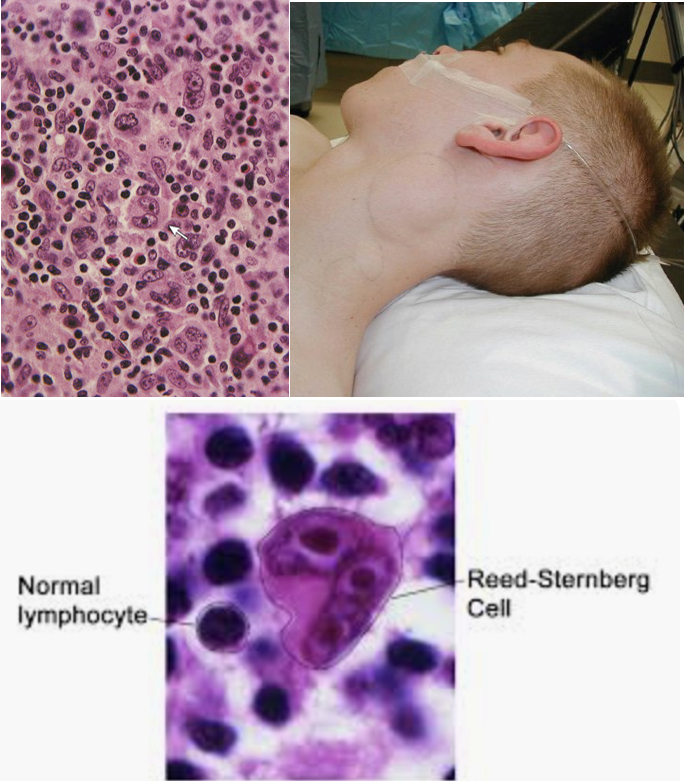

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Blood/Lymph Cancer

Most common in teens and young adults.

Hallmark sign = presence of Reed-Sternberg B cells.

These are malignant cells that proliferate in lymph tissues → lymphadenopathy, which compresses nearby structures, kills healthy cells, and invades surrounding lymph tissue, then non-adjacent lymph tissue.

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) infection is associated with many cases of this cancer; 10% of malignancies in patients with primary immunodeficiency.

Signs & Symptoms:

Weight loss.

Fever.

Night sweats.

Anorexia.

Enlarged, matted lymph nodes (supraclavicular and cervical are the most common!).

Mediastinal mass may be present.

Diagnostic Tests:

Lymph node biopsy (may need a CT or PET-CT to identify the site for biopsy).

Management:

Chemotherapy.

Radiation.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) for relapse or lymphoma unresponsive to treatment.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Blood/Lymph Cancer

Includes all lymphomas except Hodgkin’s.

Accounts for about 48% of malignancies in patients with primary immunodeficiency.

Progression is quick, and signs and symptoms appear early in the disease process.

Cause:

B and T lymphocytes mutate → proliferate rapidly, affecting deeper lymph nodes with dissemination into the bloodstream.

Signs & Symptoms:

Pain.

Lymphadenopathy (may occur anywhere in lymph tissues).

Abdominal mass (if a mediastinal mass is present, the patient may develop Superior Vena Cava (SVC) syndrome).

Diagnostic Tests:

Lymph node biopsy.

Bone marrow biopsy.

Chest X-ray.

CT scan for evaluation of the extent of the disease.

Management:

Chemotherapy with maintenance for 2 years.

CNS prophylaxis.

May need autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT).

Hodgkin’s vs. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma typically begins in the upper body, such as the neck, chest, or armpits.

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma may arise in lymph nodes anywhere in the body.

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma tends to progress in a more predictable way than Non-Hodgkin’s, making it easier to recognize and treat.

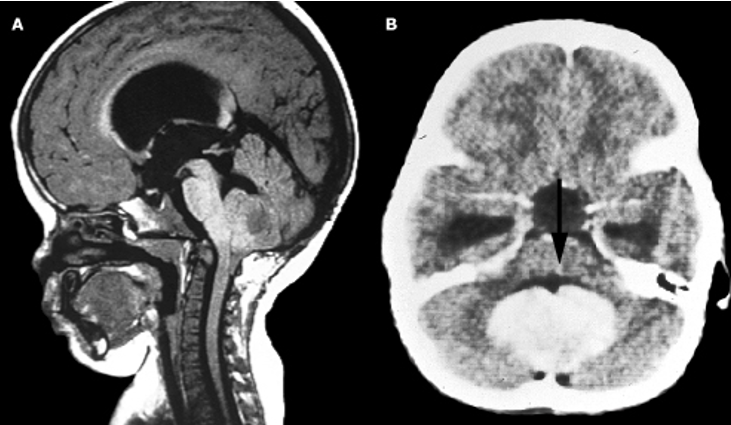

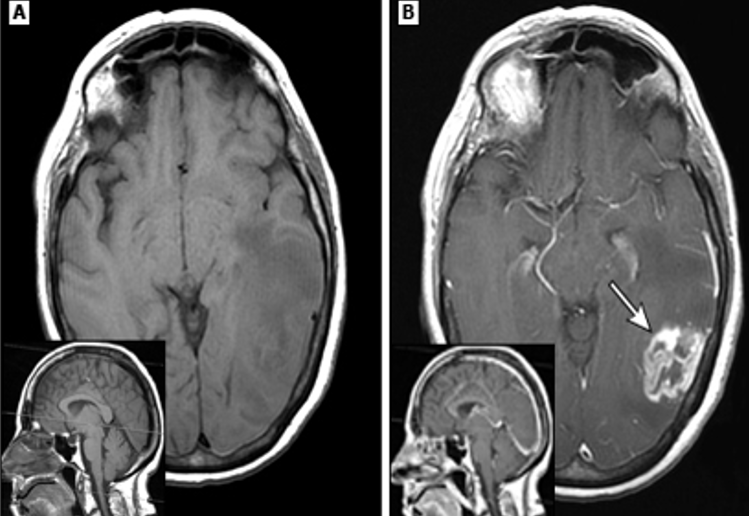

Medulloblastoma

Brain Cancer

Most common malignant tumor of childhood.

Primarily occurs in the cerebellum.

Signs & Symptoms:

Increased ICP (headaches, vomiting, dizziness, double/blurred vision, ataxia).

Seizures.

Weakness.

Behavioral or developmental issues.

Diagnostic Tests:

Head CT.

Brain MRI.

PET scan.

Final pathology from surgical resection.

Management:

Corticosteroids initially for ICP.

Surgical resection of the tumor.

Multimodal treatment plan consisting of radiation therapy (RT) for the remaining disease following resection and chemotherapy.

High-Grade Gliomas

Brain Cancer

Gliomas found in the brainstem make up 10% to 20% of all CNS tumors in children, with one-third being this cancer.

Rapidly progressive tumors, diffuse within the brainstem.

Signs & Symptoms:

Similar to medulloblastoma.

Headache (50% to 60% of patients).

Memory loss (20% to 50% of patients).

Language deficits.

Changes in cognition and behavior.

Management:

Resistant to chemotherapy.

Difficult to resect.

The goal of resection is to excise the maximum safe amount of the tumor while preserving neurologic function.

Osteosarcoma

Bone Cancer

Most common primary malignancy of bone in children and adolescents (60%).

Metastasis occurs in the lungs and other bones.

Often occurs in the long bones—distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus.

Signs & Symptoms:

Intermittent pain localized to the tumor site.

Tends to develop following an injury.

Limping.

Changes in gait.

Soft tissue mass on examination that is tender to palpation.

Diagnostic Tests:

MRI of the affected bone (sunburst sign present in many patients).

Bone biopsy.

Staging workup, including:

Chest CT to assess for metastasis.

Radionuclide bone scan to assess for other areas of malignancy.

Management:

Tumor resection (amputation vs. limb-sparing).

Chemotherapy.

Radiation in some cases.

Image:

(A) Sunburst appearance.

(B) Bone scintigraphy—left tibia shows tracer accumulation.

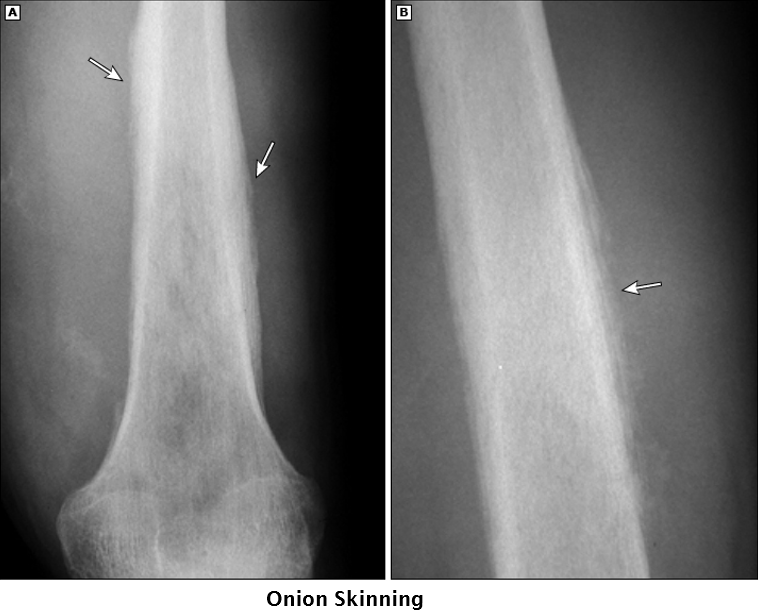

Ewing Sarcoma

Bone Cancer

Most often arises in the long bones of the extremities (predominantly the femur, but also the tibia, fibula, and humerus) and the bones of the pelvis.

Second most common primary bone malignancy in children (30%).

Due to this cancer’s prolonged time period from symptom onset to diagnosis, about 25% of patients present with metastasis (lungs and bone marrow are the most common sites).

Signs & Symptoms:

Trauma may incite symptoms.

Intermittent pain that transitions to constant pain over weeks to months.

Pain worsens with activity and at night.

Edema and erythema over the mass are common.

Diagnostic Tests:

X-rays.

MRI or CT of the affected bone.

Bone biopsy.

Chest CT to assess for metastasis.

PET-CT for staging, response to treatment, and surveillance.

Management:

4-6 chemotherapy cycles prior to local therapy.

Surgical resection is preferred over radiation in most cases due to the risk of radiation-induced sarcomas.

14-17 chemotherapy cycles post-local therapy.

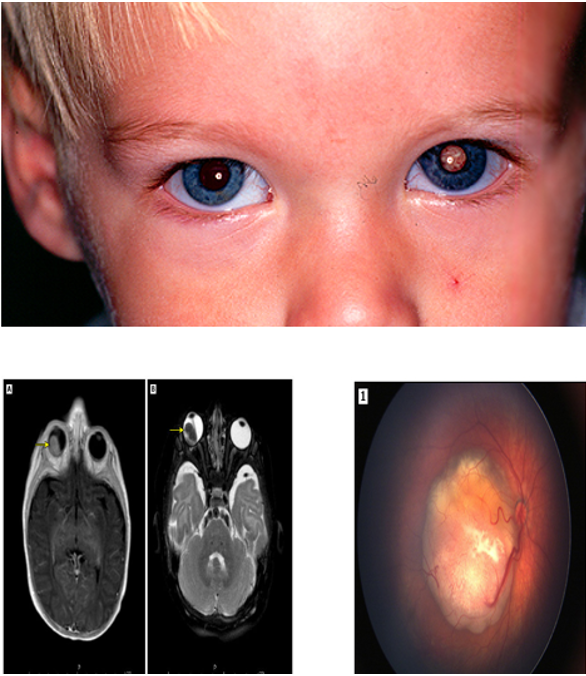

Retinoblastoma

Other Cancer

Most common primary intraocular malignancy in children.

10% to 15% of cancers occur in children < 1 year of age.

Has heritable and non-heritable types.

Can metastasize into the CNS through the optic nerve.

Signs & Symptoms:

Leukocoria.

Strabismus.

Nystagmus.

Diagnostic Tests:

Dilated ophthalmoscopic examination.

Does not require biopsy (risk of tumor bleeding).

Imaging studies.

Management:

Chemotherapy (for more severe cases).

Ophthalmic artery chemosurgery (OAC).

Focal techniques like cryotherapy and laser photoablation (for low-risk patients).

Enucleation (if a large tumor is present or there is progression into the optic nerve).

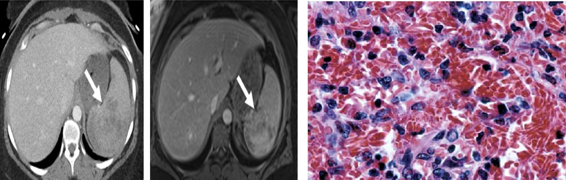

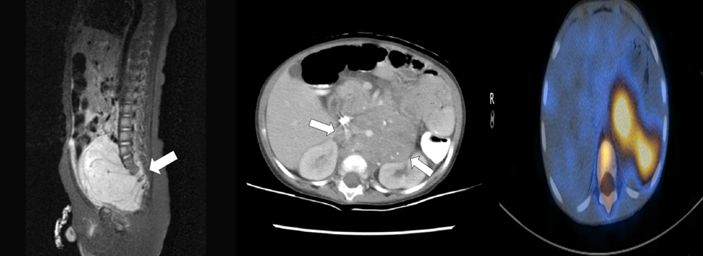

Neuroblastoma

Other Cancer

Tumor originates from neural crest cells during fetal development.

Can arise anywhere throughout the sympathetic nervous system (adrenal glands are the most common, followed by the abdomen).

Signs & Symptoms:

Non-tender abdominal mass and/or asymmetry.

Abdominal pain.

Constipation.

Back pain/weakness from spinal cord compression.

Fever.

Weight loss.

Anemia.

Bone pain.

Bowel/bladder dysfunction.

If metastasis to the skull occurs, the patient may present with facial edema and ecchymosis above the eyes.

Diagnostic Tests:

Biopsy of primary tumor.

Bone marrow biopsy.

Urine catecholamines.

CT.

MRI.

PET-CT.

Management:

Low-risk patients: Surgical resection with observation is sufficient.

Moderate-risk patients: Surgical resection and chemotherapy.

High-risk patients: Resection, chemotherapy, radiation, and tandem autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT).

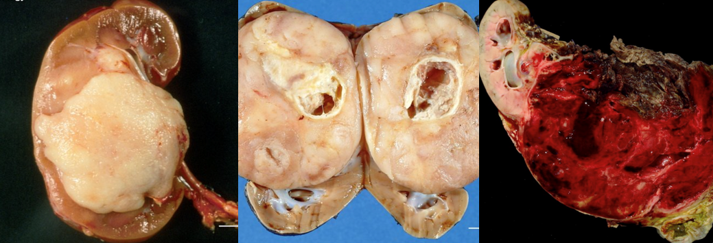

Image: (Left to Right)

MRI of a large pelvic neuroblastoma with extension into the spine

Neuroblastoma from adrenal gland

PET/CT imaging of the abdominal neuroblastoma with metastasis.

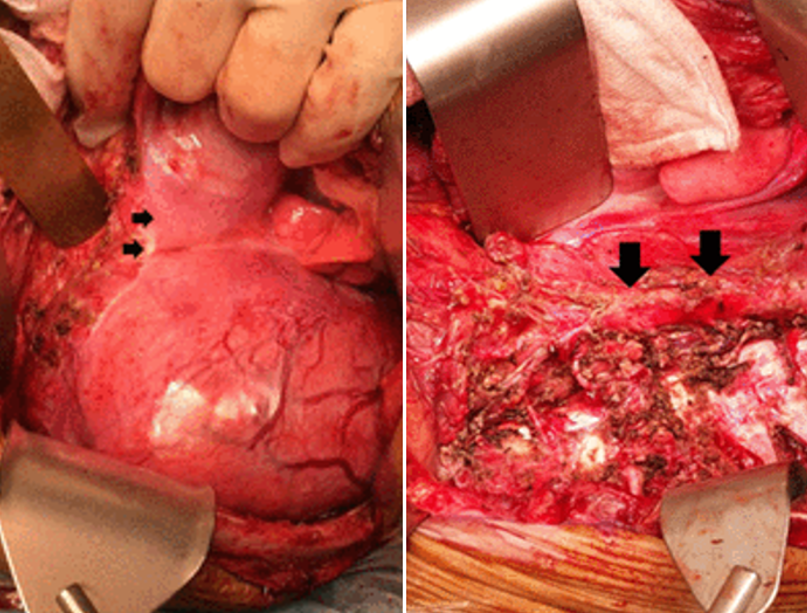

Wilms Tumor (Nephroblastoma)

Other Cancer

Most common renal malignancy in children (5% of all childhood malignancies).

95% of patients are diagnosed before 10 years of age.

The lung is the primary site of metastasis.

Most are solitary tumors, typically surrounded by a pseudocapsule (5% to 7% are bilateral).

Signs & Symptoms:

Firm, smooth abdominal mass that does not cross the midline.

Abdominal distension.

Abdominal pain.

Hematuria.

Fever.

Hypertension.

Note: Once this cancer is suspected, abdominal palpation should be limited as the capsule could rupture → tumor spreads → ascites likely present if the capsule ruptures.

Diagnostic Tests:

Abdominal ultrasound initially.

Abdominal CT and MRI.

Chest X-ray or chest CT to rule out lung metastasis.

Histology from biopsy or surgical excision of the tumor.

Renal function tests.

Management:

Stage I & II: Resection and chemotherapy.

Stage III & IV: Also receive radiation therapy.

Diagnosing Pediatric Cancer

Complete history and physical assessment.

May initiate some diagnostic screenings.

Consult with or refer to a pediatric oncologist (provider).

Complete diagnostic workup.

Confirm diagnosis.

Diagnosing Pediatric Cancer: H&P (History and Physical Examination)

Child’s PMHx:

Allergies

Immunization status

Current medications

Birth history

History of diseases, hospitalizations, or surgeries

Family History:

Hematology/oncologic conditions

Social History:

Home and school environment

Extracurricular activities

Drug/alcohol/tobacco use

Sexual activity

History of Present Illness (HPI) with Review of Systems (ROS):

Fatigue

Weight loss

Night sweats

Bruising

Pain

Pallor

Dyspnea

Excessive bleeding

Headaches

Nausea/vomiting or changes in bowel habits

Visual disturbances

Recurrent fevers

Changes in behavior

Physical Examination:

Head-to-toe fashion

Vital Signs

Diagnosing Pediatric Cancer: Initial Screening Tests

Provider may order screening tests based on information gathered from H&P:

CBC with differential

Coagulopathies

Complete metabolic panel (CMP)

Blood cultures

Lumbar puncture

Imaging: X-ray, Ultrasound (US), CT scan, MRI

If results are suspicious → referral to pediatric oncologist.

Management of the Pediatric Patient with Cancer

Therapeutic plan includes initial and ongoing treatment as well as supportive care:

Multidisciplinary

Individualized

Multimodal

Clinical Trials

Treatment Modalities for Pediatric Cancers

Surgery:

Tumor debulking

Tumor resection

Central venous line (CVL) placement

Chemotherapy

Radiation

Biotherapy

Bone Marrow Transplant (BMT)/Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT)

Supportive therapy

Surgery: Post-Op Nursing Care

Administer pain/nausea medication and antibiotics as ordered.

May have an epidural (site checks) and/or PCA.

Assess surgical site:

Bleeding

Signs and symptoms of infection

Frequent physical assessments and monitor vital signs closely.

Assess for signs and symptoms of increased ICP following brain tumor resection.

Strict I & Os:

NG tube, emesis, urinary output, drain (EVD, JD, Hemovac, etc.), chest tube(s), IV fluids, PO intake.

Follow labs if ordered:

CBC, CMP, pathology, etc.

Incentive spirometry

PT consult and early ambulation when possible.

Radiation Therapy (RT)

Damages or kills cancer via radiant gamma or particle form.

May be used as a curative, adjunct, or palliative approach to care.

Sometimes utilized to shrink tumors prior to surgical resection.

Provide comfort during radiation as children are often fearful of machinery.

Shield must be used to protect healthy tissues from damage.

Do not attempt to remove skin markings from radiologist.

Adverse Effects:

Fatigue

Nausea/vomiting

Mucositis

Myelosuppression

Damage to skin

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutic agents may work to alter the cancer cell during a specific point in the cell cycle or act on the cancer cell at any point during its cell cycle.

Cancer drugs also alter normal cells, causing the adverse effects seen with chemotherapy.

Targeted therapies (monoclonal antibodies, tyrosine kinase inhibitors) attack specific cancer cells and are less harmful to normal cells.

Chemotherapy protocols "pathways" exist among several different types of cancer.

Most created by the Children’s Oncology Group.

Combination of drugs given during phases of the cell cycle to maximize the destruction of cancer cells.

Usually has three phases:

Remission induction

Intensification (consolidation)

Maintenance

Chemotherapy: Administration

Several types that must be prepared and given by a nurse specialized in chemotherapy administration.

Dosing is based on body surface area (BSA) or weight.

Should be prepared in a quiet, low-traffic room dedicated to chemotherapy.

PPE should be worn when preparing and administering chemotherapy:

Double chemotherapy gloves

Protective chemotherapy gowns

Eye protection, possibly a face shield (in case of splash)

Respiratory protection against potential inhalation

Shoe and hair covers

PPE should also be worn for 48 hours following administration when handling a patient’s body fluids and linen:

Double chemotherapy gloves

Face shield

Chemotherapy: PPE

Do not handle phone or other personal objects with double gloves on.

Do not reuse disposable PPE.

Change gloves after 30 minutes or if torn or contaminated.

Change gowns when leaving the handling area, after a spill or splash, or after two to three hours of continuous use.

Remove shoe covers when leaving the compounding area or after cleaning a spill.

Do not use eyeglasses as your sole means of eye protection; use goggles with side shields or a face shield when splashing is a possibility.

Dispose of all disposable PPE in a hazardous waste container after use.

For non-disposable PPE (i.e., respirators, eye, and face protection), decontaminate and clean after use and take care to properly dispose of the materials used to decontaminate this equipment.

Treatment Modalities for Pediatric Cancers: Common Side Effects

Monitor for and Prevent Common Side Effects of Therapies:

Infection

Pain

Anemia or blood loss

GI symptoms:

Anorexia

N/V/D

Diarrhea

Constipation

Damage to oral mucosa

Damage to skin

Alopecia

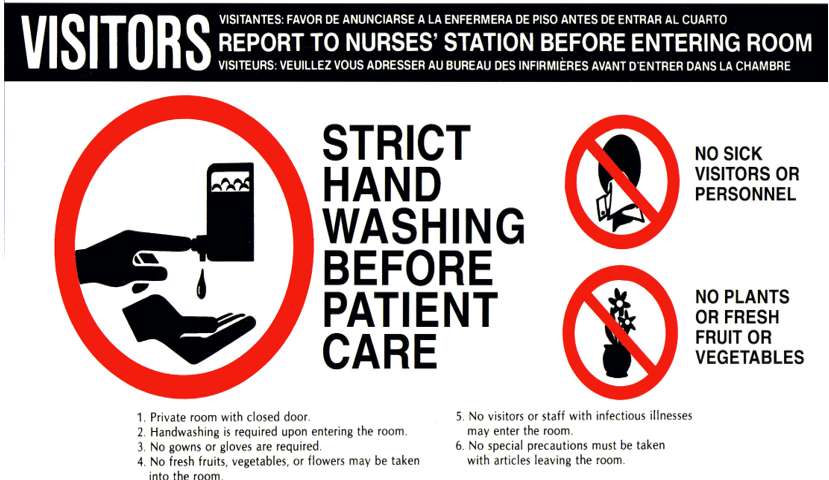

Neutropenic Precautions

Absolute neutrophil count (<1000 = neutropenia)

WBC x total neutrophils

Private room, closed door.

Frequent hand hygiene.

Avoid rectal temperatures, enemas, and invasive procedures like catheterization.

No fresh fruits/vegetables, flowers, or plants in the room.

Visitor restrictions.

Vital signs per protocol.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Infection Prevention

Regular assessments for potential infection(s).

Administer prophylactic antibiotics as ordered.

Promote and enforce proper hand hygiene.

Promote caregivers' understanding of steps to prevent infection:

Limit visitors.

Avoid sick contacts and crowds.

Encourage vaccination (no live vaccines) once approved by the provider.

Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection (no rectal temperatures) — Notify oncologist or bring the child to the ED if febrile.

Neutropenic precautions if indicated.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Preventing Anemia & Hemorrhage

Assess for signs and symptoms of bleeding (bruising, pallor, lightheadedness, changes in vital signs).

Avoid rectal temperatures and examinations (damage to rectal mucosa → bleeding).

Apply pressure to potential sites of bleeding (injection sites, bone marrow biopsy site).

Limit blood draws/injections.

Encourage intake of iron-rich foods.

Administer platelets (PLT) and erythropoietin (EPO) as ordered.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Managing GI Symptoms (N/V/D, Constipation, Anorexia)

Administer antiemetics (before onset of nausea and as needed) and antidiarrheals as needed.

Hydration therapy (oral and/or IV); parenteral nutrition (TPN/lipids) as ordered.

Strict I & Os.

Monitor weight frequently.

Protect the perineum from skin breakdown.

Determine the child’s preferred foods, provide high-calorie meals when the child is most hungry, and offer supplemental shakes.

Offer small meals more frequently.

For constipation—increase fluid and fiber intake; administer stool softeners or laxatives as ordered.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Skin Protection

Avoid adhesives.

Use gentle soaps/cleansers and pat the skin dry following baths/showers; avoid fragrant deodorants/soaps.

Moisturize skin frequently.

Administer Benadryl and/or hydrocortisone cream as ordered for itching.

Apply Silvadene cream to areas of desquamation from radiation.

Avoid direct sun and wear loose-fitting clothes following radiation.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Protection of Oral Mucosa

Frequent assessments, keep mucosa moist (oral hydration, ice chips if NPO, petroleum jelly to lips).

Saltwater rinses or mouthwash (without alcohol) every 1-2 hours for hygiene.

Use a soft toothbrush (prevents gum irritation/bleeding).

If mucositis is present: administer magic mouthwash as ordered, avoid spicy/acidic foods, and provide pain medications as ordered.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Promote Mobility & ADLs

Encourage ambulation and activity, monitor for signs and symptoms of intolerance (dizziness, lightheadedness, pallor, orthostatic hypotension).

Cluster nursing care and offer periods of rest.

ROM exercises and position changes if limited mobility or on bedrest.

PT/OT consult, follow recommendations.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Promote Self-Esteem & Body Image

Explore strengths and weaknesses, provide honest feedback.

Encourage the child to perform activities of daily living when able, schoolteacher consult.

Offer self-care activities and emotional support groups.

Encourage participation in support groups.

Allow the child to make decisions about appearance and spend time with peers who have or are undergoing similar experiences.

Discuss counseling referral with the child, caregivers, and provider.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Promote Coping Mechanisms & Sense of Control

Consult child life specialist (CLS) prior to invasive exams/procedures.

Educate and allow the child to make decisions about care when appropriate.

Encourage the child to spend time with friends, support/teen groups.

Open communication, allow the child to express emotions, acknowledge feelings.

Pediatric Cancer: Nursing Care—Deliver Patient & Family-Centered Care

Provide emotional support.

Educate surrounding infection prevention measures, management of pain and other treatment side effects, preparing for home health needs (medication administration, CVL care, equipment needs, etc.).

Child life specialist (CLS) for siblings, chaplaincy consult.

Inform about community resources (support groups, grief counseling).

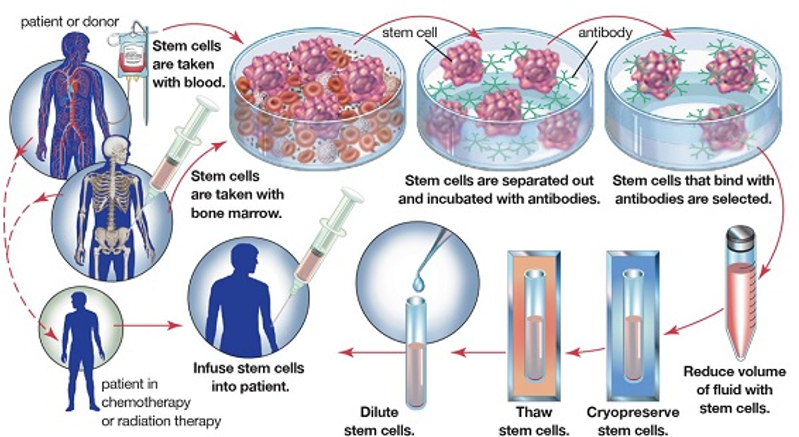

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT)

Also known as bone marrow transplant (BMT).

Autologous: uses the child's own stem cells; stem cells are removed and frozen, then chemotherapy or radiation occurs, and finally, the cells are thawed and reinfused.

Allogeneic: uses a matched donor's stem cells.

The child undergoes extensive evaluation and preparation:

Evaluation from the transplant team

Family planning (prolonged hospitalization)

CVL placement

HLA matching (allo)

Stem cell harvest (auto or allo)

Myeloablative therapy

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT): Pre-Transplant Care

Prevention of Infection:

Isolation in a negative pressure room.

Limit visitors (caregivers).

Administer prophylactic antibiotics (ABX), antifungals, antivirals (acyclovir, flu shot).

Frequent hand hygiene.

Provide CVL site care.

Regular CHG bathing.

Administer blood products as needed (PRN).

Administer granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) if ordered.

Provide child and family education and support.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT): Post-Transplant Care

Prevention and Monitoring of Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD):

Administer prophylactics (cyclosporine and methotrexate are most common).

Maculopapular rash → skin desquamation, diarrhea.

May require systemic steroids if development of GVHD occurs.

Manage GI symptoms.

Infection prevention.

Monitor for bleeding and pancytopenia.

Administer blood products as needed (PRN).

Administer G-CSF as ordered for autologous HSCT recipients.

Filgrastim may be given via injection or IV.

Tumor Lysis Syndrome

Pathogenesis:

Initiation of therapy (chemo, radiation, glucocorticoids) → rapid lysis of tumor cells → intracellular contents (K+, PO4, uric acid) release into systemic circulation → metabolic consequences.

Metabolic consequences include hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, secondary hypocalcemia, hyperuricemia, and AKI.

Excess phosphate binds to calcium in the blood. This is a result of rapid cell breakdown from cancer treatments, which releases phosphates into the blood.

Clinical Manifestations:

N/V/D, anorexia, lethargy, muscle cramps, dysrhythmias, heart failure, seizures, tetany, syncope, hematuria.

Prevention of TLS:

Administer hypouricemic agent (Allopurinol) prophylactically and during treatment.

IVFs at 2x maintenance.

Frequent monitoring of serum electrolytes, urine output, and serum acid.

Management:

Electrolyte Correction:

Hyperkalemia: Limit K+ intake, cardiac monitoring, frequent serum K+ levels, administer glucose with insulin or calcium gluconate as ordered to decrease risk for dysrhythmias.

Hypocalcemia: If symptomatic, treat with the lowest dose of Ca.

Hyperphosphatemia: Aggressive hydration, phosphate binders.

Renal Replacement Therapy, Hemodialysis:

Indicated for patients with persistent hyperkalemia, symptomatic hypocalcemia from hyperphosphatemia, severe oliguria, anuria, or fluid overload.

Pediatric Cancer Survivorship

Survivors often experience stress, anxiety, and depression due to living with heightened awareness of health uncertainties.

The Institute of Medicine describes the essentials of cancer survivorship (below):

Prevention of cancer recurrence or new cancers and late effects.

Surveillance for cancer spread or development of a secondary cancer.

Intervention for the effects of cancer and its treatment.

Coordination of care between primary care provider and specialists.

Transition to adult follow-up when age-appropriate.

All patients should be given a survivorship care plan (SCP), which summarizes cancer treatment provided and follow-up recommendations (short and long-term).

Patients and families should be given information about support groups. Many survivors benefit from discussing concerns with peers who have similar experience(s).

Supportive Care for End of Life

End-of-life care is focused on the comfort of the child and minimizing suffering for both the child and family. Keep family routines as much as possible.

Symptom Management:

Symptoms experienced during the dying process may include pain, fatigue, depression, anxiety, dyspnea, sleep disruption, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, etc.

Therapies to manage symptoms may be pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, or a combination of both.

Nurses, along with other interdisciplinary team members, provide physical, emotional, spiritual, and psychosocial support:

Palliative care, oncology, chaplain, child life specialists, social worker, hospice (if involved), grief counselors.

Preparation for the Death of the Child:

The family should decide on the preferred location of death.

Discuss changes that will occur during the dying process (fatigue, delirium, mottling/cool skin, breathing changes—pattern and noise, inability to close eyes) with the family.

Assist the family in obtaining locks of hair, handprint molds, photographs, and other keepsakes.

Allow and encourage cultural practices.

Bereavement Follow-Up:

Check in with the family as appropriate, especially during difficult occasions (birthdays, holidays, anniversary of death).

Provide information about support groups for caregivers and siblings.

Grief counseling.

Primary Immunodeficiencies

Mostly hereditary or congenital.

Types:

Humoral deficiencies

Cellular immunity deficiencies

Combination of humoral and cellular immunity deficiencies

Phagocytic system defects

Complement deficiencies

Immunodeficiency Disorders in Children

Hypogammaglobulinemia:

Low immunoglobulin or antibody levels.

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome (X-linked genetic disorder):

T-cells and B-cells are present but not functioning appropriately.

White blood cells (WBCs) do not properly reach sites of infection.

The body does not properly produce platelets.

Severe Combined Immune Deficiency (SCID) or (Rare X-linked or autosomal recessive disorder):

Absence of both T-cell and B-cell function.

Potentially fatal disorder requiring emergency intervention at the time of diagnosis.

_________________________________________________________________

Management for all primary immunodeficiencies:

No live vaccines

Avoid contact with sick individuals

Take prescribed immunoglobulin therapy

Report signs and symptoms of infection or illness immediately

Nursing Assessment of Primary Immunodeficiencies

Chronic diarrhea

Failure to thrive

History of severe infection early in infancy

Persistent thrush

Adventitious sounds related to pneumonia

Very low lab levels of immunoglobulins

Bleeding and low platelet levels

Ten Warning Signs of Primary Immunodeficiency

Four or more new episodes of acute otitis media in one year.

Two or more episodes of severe sinusitis.

Treatment with antibiotics for two months or longer with little effect.

Two or more episodes of pneumonia in one year.

Failure to thrive in an infant.

Recurrent deep skin or organ abscesses.

Persistent oral thrush or skin candidiasis after one year of age.

History of infections requiring IV antibiotics to clear.

Two or more serious infections such as sepsis.

Family history of primary immunodeficiency.

Primary Immunodeficiencies: Nursing Management

Good handwashing

Prevent outside exposures

Should NOT receive live vaccines

Encourage good nutrition

IVIG infusions

Bone marrow transplants

Genetic counseling referral

Lifelong support

Secondary Immunodeficiencies

Causes:

Chronic illness

Severe burns

Malignancy and chemotherapy

Use of immunosuppressive medication (lowers the immune response)

Malnutrition or protein-losing state

Prematurity

HIV infection

Autoimmune Disorders

Malfunction of the immune system

Body manufactures T-cells and antibodies against its own cells and organs

Multifactorial in nature (heredity, hormones, environment)

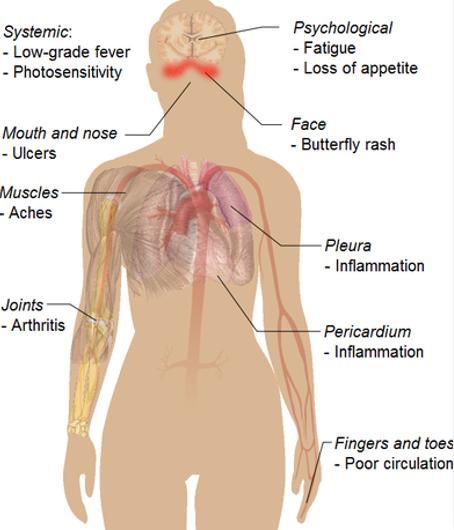

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

A multisystem autoimmune disorder affecting both humoral and cellular immunity.

Onset and course of the disease are variable (rarely diagnosed before 9 years of age).

Chronic with periods of remission and exacerbation (flares).

SLE: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostics, Management

Common Symptoms:

Affects any organ system

Hematologic, cutaneous, and musculoskeletal

Fatigue, fever, weight changes, pain/swelling/edema of joints, numbness, prolonged bleeding, malar rash/butterfly rash, changes in pigmentation, hypertension, abdominal tenderness (more common in children)

Complications:

Ocular or visual changes

CVA

Pericarditis

Heart disease

Seizures

Psychosis

Diagnostic Tests:

CBC (low Hgb/Hct, PLT, WBC counts)

Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) — usually positive in children

Management:

Medications:

NSAIDs, corticosteroids, antimalarial (mild to moderate)

High-dose pulse corticosteroids (severe)

Promote sleep, rest, healthy diet, and exercise

Prevention:

Sunscreen (photosensitivity), layering (winter)

Monitor:

BP, serum BUN and CRT levels, decreased urine output, vision screenings

**Image shows a malar/butterfly rash**

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is a…

Autoimmune inflammatory disorder where antibodies primarily target the joints.

It can range from mild to systemic.

JIA: Clinical Manifestations & Diagnostics

Onset before 16 years of age

Manifestations persist for at least six weeks

Etiology is unknown.

Infant/Nonverbal Child:

Irritability/Fussiness

Withdrawal from play

Difficulty getting up in the morning

Prolonged, high fevers (>39°C)

Red, macular rash in the systemic type of this disease

Limping; may guard the affected joint/extremity

Joint Symptoms:

Edema

Redness

Warmth

Tenderness

Stiffness

JIA: Nursing Management & Care

Promote and Maintain Mobility:

Splinting

Exercise (swimming)

Heat therapy, warm packs, warm baths

Medication Administration:

NSAIDs

Corticosteroids

Antirheumatic drugs:

Etanercept

Methotrexate

Goals of Nursing Care of the Child with Immune Disorders

Avoiding infection

Promoting compliance with the medication regimen

Promoting nutrition

Providing pain management and comfort measures

Educating the child and caregivers

Providing ongoing psychosocial support

Communicable Diseases in Childhood

Illness passed by direct or indirect contact.

Most can be prevented with immunizations.

Risk Factors:

Immature immune system

Limited prior exposure to communicable diseases

Increased risk due to poor health and immunodeficiency

Communicable Diseases in Childhood: Routes & Prevention

Route:

Fecal-oral

Respiratory

Prevention:

Handwashing

Standard precautions

Avoid exposure to infected individuals

Promote immunizations

Decrease/eliminate pathogens

Principles of Immunization

Active Immunity:

Antibody production is stimulated by vaccine antigens without causing clinical disease.

Natural or vaccine-induced—takes time but is long-lasting.

Passive Immunity:

Antibodies produced in another host (human or animal) are given when the child needs antibodies faster than the body can make them.

Includes immunoglobulins (IVIG).

Does not confer lasting immunity; the child will need a vaccine in the future.

Immediate but temporary.

Immunization Schedule: Pediatrics

Birth:

Hep B

2 Months:

DTaP

RV

IPV

Hib

PCV

Hep B

4 Months:

DTaP

RV

IPV

Hib

PCV

6 Months:

DTaP

RV

IPV (third dose given between 6 to 18 months)

Hib

PCV

Hep B (6 to 18 months)

12 to 18 Months:

DTaP

IPV (third dose between 6 to 18 months)

Hib

PCV

MMR

Varicella

Hep A (given in two doses at least 6 months apart)

4 Years:

DTaP

IPV

MMR

Varicella

Vaccines:

Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids and Pertussis (DTaP)

Rotavirus Vaccine (RV)

Inactivated Poliovirus (IPV)

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B (Hib)

Pneumococcal Vaccine (PCV)

Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR)

Contraindications in Immunization Administration

History of anaphylactic reaction to the vaccine or one of its components.

History of encephalitis within 7 days of DTaP.

Delay if there is moderate to severe acute illness.

Live virus vaccines (MMR, intranasal flu, varicella) are NOT to be given to children who are immunocompromised or receiving chemotherapy.

Ex: MMR is not given during pregnancy or in cases of immunodeficiency.

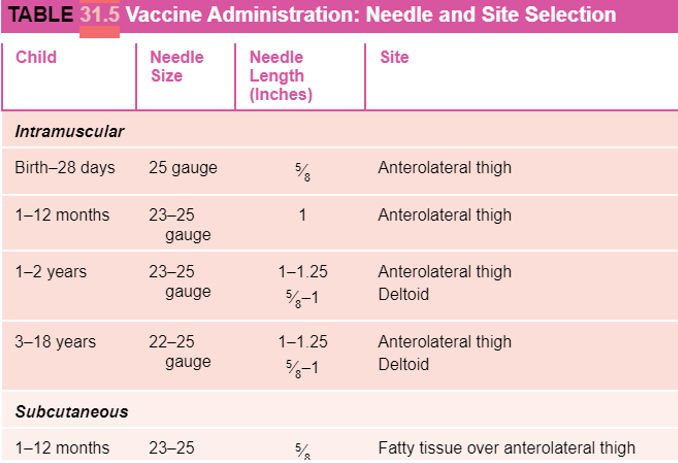

Immunization Administration: Needle & Site Selection

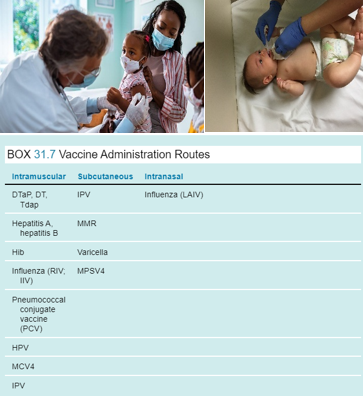

Immunization Administration in Children: Strategies & Routes

Strategies to Minimize Pain During Administration:

Provide a local anesthetic.

Give the child as much control as possible.

Be honest with the child.

Provide sucrose drink and pacifier.

Routes to Administer Vaccines:

IM is the most common and frequent route in childhood.

Some vaccines are administered SQ, intranasally, or orally (e.g., Rotavirus).

Administering Medications Prior to Immunizations

Used for any procedure in which the skin will be punctured (IV insertion, biopsy, immunization):

Apply lidocaine and prilocaine topical ointment (available as a cream or a gel).

Place an occlusive dressing over the cream after application.

Prior to the procedure, remove the dressing and clean the skin.

Indication of an adequate response is reddened or blanched skin.

Demonstrate to the child that the skin is not sensitive by tapping or scratching lightly.

Change the needle after puncturing a rubber stopper.

Use the smallest gauge of needle possible.

Use therapeutic hugging.

Secure the child firmly to decrease movement of the needle while injecting.

Provide atraumatic care:

Use distraction.

Encourage guardians to hold the child afterward.

Offer praise.

Use play therapy.

Offer sucrose pacifiers to infants.

Barriers to Immunization Compliance

Economic factors

Limited access to healthcare

Lack of convenient primary care

Parental knowledge deficit

Religious/cultural prohibitions

Current trends

Pediatric Kidneys

Kidneys are large and not well-protected from trauma.

Shorter urethra in girls increases the risk of infection.

Slower glomerular filtration rate → kidneys are less efficient at regulating fluid, electrolyte, and acid/base balance.

Smaller bladder capacity:

Infants: 20 cc to 50 cc

Adults: 700 cc

Urine Output:

Infants: 2 mL/kg/hr

Older Children: 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/hr

The renal system reaches maturity at 2 years of age.

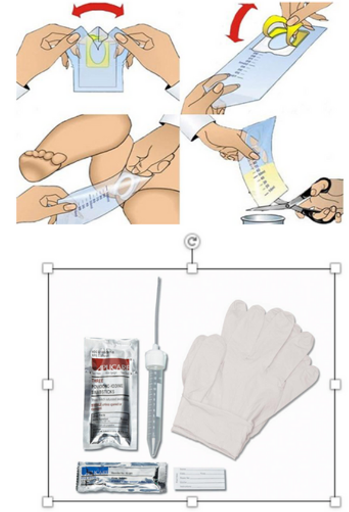

Urine Collection in Pediatric Patients

Always discuss and obtain permission for the procedure with a caregiver before catheterization.

Involve Child Life Services (CLS) for older children before invasive urine collection techniques.

Urine Bag:

Appropriate for infants and toddlers.

May be sterile or clear for urinalysis (UA).

Straight Catheterization:

Used for urinalysis (UA).

In most cases of retention or obstruction, this technique is the same as in adult patients but may be difficult due to smaller anatomy and patient cooperation.

Urinary Tract Infection

An infection of the urinary tract, most commonly the bladder, caused by bacterial transmission via the urethra.

Females are at an increased risk due to their shorter urethra length and the proximity of the urethra to the vagina and anus.

Infant Symptoms:

Irritability

Fever

Poor feeding

Vomiting

Jaundice

Children Symptoms:

Fever

Vomiting

Dysuria

Incontinence

Urinary hesitancy and urgency

Hematuria

Abdominal pain

Flank pain

Foul-smelling urine

If left untreated → pyelonephritis, urosepsis, renal scarring, and hydronephrosis.

Diagnostic Tests: Urinalysis (UA) with reflux to culture.

UA: Positive for blood, nitrates, leukocyte esterase, white blood cells, or bacteria.

Culture: Will reveal the infecting organism.

UTI: Nursing Care

Most patients will manage this at home; care surrounds education for prevention and treatment:

Ensure adequate hydration.

Avoid:

Urinary retention

Frequent bathroom breaks (*note for school-aged child).

Females:

No bubble baths or soap application to the vulva.

Wipe front to back.

Cotton underwear.

Change pads/tampons frequently during menstruation.

Void after intercourse.

Complete full course of antibiotics and return to PCP for re-check.

Pain Management:

Acetaminophen.

Ibuprofen.

Small children may void in a warm bath or with a heating pad.

Hospital Admission Criteria & Care:

Criteria: Infant <2 months—s/sx: urosepsis, immunocompromised patient, inability to tolerate oral medications.

Care: Administer antibiotic therapy, hydrate via oral or IV fluids, pain management, and antipyretic PRN.

What are Some Structural Urinary Disorders?

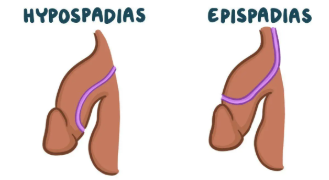

Hypospadias/Epispadias

Vesicoureteral Reflux

Hypospadias/Epispadias

Hypospadias:

A congenital anomaly of the male urethra, foreskin, and penis leading to the abnormal ventral placement of the urethral opening.

Epispadias:

A defect in which the urethral opening is on the dorsal surface of the penis.

Abnormal displacement has the potential to cause developmental or functional issues:

Deflection of the urinary stream.

Inability to urinate standing.

Erectile dysfunction causing intercourse difficulties.

Problems with fertility due to improper deposition of sperm.

Circumcision is contraindicated before surgical repair.