Animal Behavior 3436 Final

1/190

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

191 Terms

Caribou vs Salmon vs Arctic tern Migration

Caribou - social, memory

Sockeye salmon - olfacation, geomagnetic, in group

Arctic tern - celestial, geomagnetic, olfacation, memory

Not every animal uses same information to move through its environment

All have multiple ways, not just one clear mechanism

Navigational systems often have redundancy, one fails another kicks in

Planet Earth – Christmas Island Crabs (Migration & Reproduction)

Christmas Island red crabs are terrestrial (land) crabs that live in forest habitats most of the year.

Once a year, strong seasonal and environmental cues (e.g., rainfall, lunar cycle, tides) trigger a highly synchronized migration from the forest to the sea.

Males migrate first, reach the coast, and dig burrows where mating occurs.

After mating, males return to the forest, while females remain to develop eggs.

Each female carries ~100,000 eggs and times release around midnight to reduce predation.

Females cannot swim, but briefly enter the ocean to shed eggs into the water, then return to land.

This is an example of migration at a small spatial scale, but with extreme coordination and synchrony across the population.

Demonstrates how reproductive success depends on precise timing, environmental cues, and collective behavior.

Avian Migration - Arctic tern & Bar tailed godwit

Avian migration is the regular, seasonal movement of birds between breeding and non-breeding areas.

The Arctic tern performs the longest migration of any animal, traveling from Arctic breeding grounds to Antarctic waters and back each year.

Birds nesting in places like the Netherlands travel ~90,000 km annually, following summer and optimal food availability.

Arctic terns use stopover sites to rest and refuel before continuing migration.

The bar-tailed godwit holds the record for the longest non-stop flight: ~11,026 km in ~9 days.

Godwits migrate from the subarctic directly to Australia and New Zealand without stopping.

During this journey, they are continuously flapping (not soaring), relying on extreme energy efficiency and fat reserves.

These species demonstrate remarkable navigation abilities, endurance, and physiological adaptation to long-distance travel.

Forms of orientation and navigation (6)

Landmark use

Vector navigation

Path integration

The cognitive map

Celestial navigation

Earth’s magnetic field

European Beewolf

The European beewolf is a solitary predatory wasp that specializes in hunting honeybees.

Females dig underground burrows and stock each chamber with paralyzed (but still alive) bees, then lay an egg on the prey.

The prey is kept alive but immobile, which prevents decomposition and provides fresh food for the developing larva.

When the egg hatches, the larva feeds on the stored honeybee.

Honeybees are similar in size to the wasp, showing the beewolf’s strength and specialization.

A key behavioral mystery: after hunting, the female covers and conceals the burrow entrance, making it invisible to predators or competitors.

Despite this, she can return and locate the exact spot immediately, showing precise spatial memory and navigation.

This example highlights parasitoid behavior, prey preservation, and remarkable homing/navigation ability at a very small spatial scale.

Charles Henry Turner (1908)

Looking at wasp behavior, coming up with hypothesis and questions

Hes saying if everything stays the same ground nesting bees/wasps, they go out and come back = no searching

But if anything in topography or surround of the burrow is changed, then the bees are disoriented and struggle to find burrows, and inspect the environment upon leaving

Tinbergen

Tinbergen did almost exactly same thing

Ground nesting bee/wasp, place a bunch of pinecones around burrow (black dot)

Wasp comes out, sees change in topography and does little flights, exploration or orientation flights, taking in info about environment in relation to its burrow

Comes out, something different, zoom around see whats going on, now go back to forage

What happens if I move the pinecones? Induce bee/wasp to visit a false nest?

Circle of pinecones moved adjacent

wasp/bee searched in center of pinecone circle in new location, not burrow

How are landmarks used?

Get direction and distance information from knowing the landmarks that surround location looking for

Combine direction and distance to create vector

Vector Navigation

Vector navigation - using landmark to create vectors, integrating vectors to give you location

Triangulation finds the location of a goal using only directions (or bearings) from landmarks.

Bearings from two landmarks can fix the location and bearings from three landmarks reduce possible error

vector navigation vs true navigation

Vector navigation means an animal follows a fixed direction and distance (a compass direction) without knowing its actual geographic position.

True navigation means the animal knows where it is relative to its destination and can correct its route if displaced, using a map-like system.

Vector navigation in migration

European starlings normally migrate from Norway to Spain in a fairly straight line.

Researchers allowed birds to migrate partway (to the Netherlands) and then artificially displaced them further east into Europe.

This tested whether migration is driven only by a simple vector, or by multiple integrated navigational cues.

Juvenile (first-year) starlings continued flying along their original vector after displacement and ended up in Italy.

→ Evidence for vector navigation.

Experienced adult starlings corrected their route after displacement and still reached Spain.

→ Evidence for true navigation.

Key conclusions

Vector navigation is used by young, inexperienced birds, but it cannot fully explain migration.

True navigation depends on experience and memory.

True navigation requires both a compass (direction) and a map (position).

Migration relies on multiple mechanisms, with vector navigation being an important early-life component, but not sufficient on its own.

Path integration - R Wehner and the desert ant

R. Wehner found that the desert ant Cataglyphus uses path integration to return to its nest

Researchers thought that this was some sort of path integration, keeping record of outward journey, integrate info, and find way home

In effort to discover whether ants were using internal pedometer as path integration mechanism, researchers experimentally modified length of legs

Found exactly what described

Took ants at end of outward journey, when turning for home, and modified the length of legs

Those that had lengthened legs, went past nest site, like expected, internal pedometer count steps out, going back

When shortened legs they came up and searched shorter

Effective in showing internal mechanism keeping track of steps and movements

Path integration

is a method of orientation that uses only self-generated, or “idiothetic” (internally generated) information:

vestibular information from rotation and motion

Tells if turning, up vs down hill

proprioceptive feedback from limbs and muscles

As move through the space, all of sensory systems feed back and give information on how limbs moving

Ex. on treadmill, blindfolded, if added incline cant see, but feel in body (proprioceptive feedback)

motor output to limbs and muscles

How many steps taking

By maintaining a record of distances and changes in direction during an outward journey, an animal can calculate a homeward vector at all points on the outward path.

Returning home requires only following this vector (direction and distance) back to the start of the outward path

What is a cognitive map?

A cognitive map is an internal representation of the environment that encodes routes, spatial relationships, and locations, allowing animals to make novel navigation decisions.

Classic definition (Tolman, 1948): a representation that animals use to decide where to move, not just how to follow a learned path.

Cognitive maps - Tolman (1886 - 1959)

proposed that rats form cognitive maps rather than simple stimulus–response habits.

In maze experiments, rats could take novel shortcuts to reach a reward when familiar paths were blocked.

This suggested rats “knew” the layout of the maze and could flexibly choose new routes.

This idea aligns well with how humans think about navigation.

Gould (1986) claims …

Suggested bees form cognitive maps and may even communicate spatial information via the waggle dance.

Based on experiments where bees appeared to take novel routes between food sources.

Bee shortcut experiment

Hive located at the bottom of a V-shaped landscape.

Bees trained to visit Feeder A, then return to hive.

When Feeder A was blocked, bees flew directly to Feeder B.

Researchers argued this novel A → B route indicated a cognitive map.

Bennett’s critique (pushback)

Andrew Bennett argued this evidence does not require a cognitive map.

The landscape had large, visible landmarks (mountains, tall features) visible from both A and B.

The novel shortcut method is test for use of a cognitive map

The novel shortcut method tests whether an animal that has experience traveling from A to B and from A to C can infer the spatial relation between B and C

To be convincing the novel shortcut method requires proof that:

1. The shortcut is novel

Problem with rat maze work, rats go explore in maze, when explore sometimes take different routes, settle on favorite route

Different route isn't novel, just not favorite

2. There are no landmarks at one site that are visible from the other

Against honeybee work, if you can see a landmark or a number of them can get to location and don't need cognitive map

3. Path integration is not involved

See how path integration can develop a novel vector, allows create direct route home, generating novel vector to get you home, but not with use of cognitive map

A.T.D. Bennett concluded, in a review of previous research, there have been no tests of the cognitive map theory that rule out all three alternatives.

Celestial Cues

Animals generally use the azimuth of the sun to orient, but may also use the altitude

Honeybees Example of Celestial Cues

Angle of waggle run to vertical (α) is equal to Angle between sun and food

Sun is what honeybees use to indicate direction

Sun hits horizon is azymuth = vertical in honeybee hive

Indicate location of food by dancing at num degrees of vertical in hive

Angle dancing off of vertical is equivalent to angle from azimuth of sun

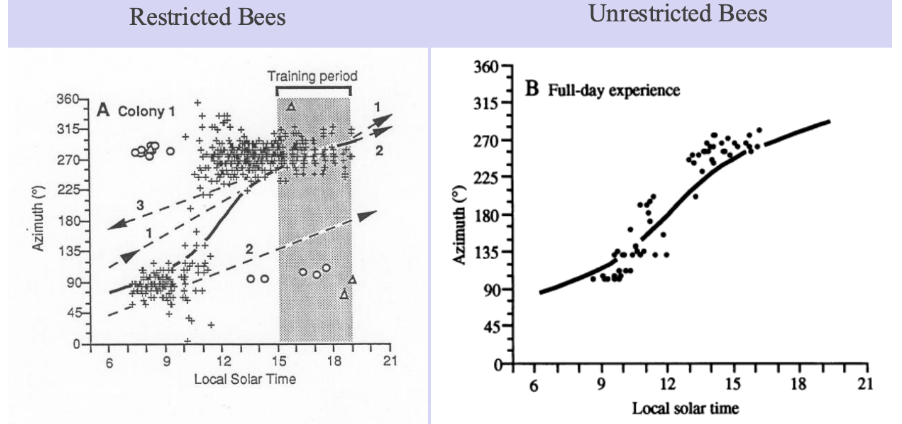

Honeybees confined to the hive compensate for the movement of the sun

As dance, change dance to match where sun has changed in the sky

At time found food, 20 degrees east of sun, at point where sun had moved westward, food now 40 degrees from azimuth of sun, honeybees change angle of sun

Change dance to match sun moving through sky

Doing based on “internal representation”, internal track of sun moving throughout the sky

Ephemeris

Ephemeris – calculated position of a celestial object at regular intervals. (Greek ephemeros ‘lasting only one day’)

Movement of sun through sky is ephemeris

Honeybees are tracking ephemeris function of the sun

Bees & Ephemeris

Allow naïve honey bees to forage only from 3 – 7 PM on sunny days

Test honey bees in overcast conditions when sun is not visible

Use orientation of dance to determine bees’ estimate of sun’s position

Tells the default assumption of the honeybee ephemeris tracking is that sun is in one place in morning vs afternoon, can do that with very little experience

But can also see they can accurately track the whole solar ephemeris function including middle space, but need experience to do so

Learn there is an innate component to ephemeris tracking honeybees doing, but also some experience component as well

Earth’s magnetic field has a variety of characteristics: name 2

Inclination, intensity

Intensity vs Inclination

Intensity

Intensity of earth's magnetic field highest at poles, weaker at equator

It is varying depending on an organisms location on the globe

Can be used to indicate where an organism is in a N/S close to poles vs equator sense

Inclination

The angle of the magnetic field relative to the earth

See at poles, directly vertical

As magnetic field curves from pole to pole the angle of these arrows changes

Magnetoreceptors difficult to identify because:

Magnetic fields pass through tissue so receptors may be anywhere in the body.

Detectors could be anywhere, cant pinpoint where to look

Receptors may be small and dispersed, or purely chemical with no associated receptor organ

Because we don't know how animals sensing fields or what representation, can't figure out what receptor would look like (vs figure out organ take in and process light like eye)

Humans lack, or are unaware of, magnetoreception

We can’t perceive the magnetic field, hard to figure out how animals do it

How do birds perceive Earth’s magnetic field? - Beaks (Wiltschko & Wiltschko, 2013)

Iron rich structures found in dendrites of homing pigeons, chickens and migratory birds’ upper beaks

Acts as a magnetometer to give intensity and inclination

Proved by: Fixed position can be disrupted in Robins with local anesthetic to upper beak

Tells us that without ability to perceive through beak, ability to orient is disrupted

How do birds perceive Earth’s magnetic field? - Eye

At different inclinations cryptochromes produce different molecular spin chemical reactions

High concentrations of Cryptochromes freely in retina, in photoreceptor cells, and in the ganglion cells

Molecule in the eye responding to changes in inclination of magnetic field

What is the neural basis of retinal magnetic field detection?

cluster N

Cluster N (Mouritsen 2005)

a forebrain region thought to control the geomagnetic compass, and is active at night when captive nocturnal migrants are in migratory condition.

defined through activation, if bird not using cluster N you can’t find it, nothing morphologically in brain indicating where that region is)

When birds are in migratory condition, and at night time for nocturnal migrants, active and ready migrate

Non-migrants have little to no activation in the Cluster N region

Nocturnal migrants do not show this activation in the day

European robins with lesions to Cluster N could not correctly orient using Earth’s magnetic field (Zapka et al., 2009)

Tells that Cluster N seems to be important for detecting magnetic fields that allow control birds to orient

Cluster N important structure for migratory birds while migrating, and for detecting magnetic fields

There’s a lot more we don’t know about Cluster N

Cluster N is a forebrain region thought to control the geomagnetic compass, and is active at night when captive nocturnal migrants are in migratory condition

Suggests migratory condition is one thing, no variability within birds

Not true

What about migratory restlessness (Zugunruhe)?

Not true due to migratory restlessness, indicating they want to fly

In emlin funnel, zipping around, want to fly and migrate

Don’t do that all the time

Even if in migratory condition, not engaging in migratory restlessness every night

We know birds have stopovers as migrate, some nights they rest, sometimes restless

Migratory restlessness

A behaviour exhibited at night when nocturnally migrating birds are in captivity

Birds aren’t restless every night

Does Cluster N have a circadian cycle during migration season, regardless of behaviour, or is it facultatively regulated on a night to night basis?

Off during day on at night as a rule? OR when animal restless and ready to fly = active vs at rest = inactive

tested in white throated sparrows that may use a night to sleep at stop over sites

Results:

Restless birds show higher levels of activation than day birds

Cluster N is regulated on a night-to-night basis

resting group same activation as bay group

Tells us that it's only when they need it, only when actively migrating (migratory restlessness)

Not actively migrating, even migratory condition even if at night, they don’t process magnetic field in Cluster N region

The defining feature of sexual reproduction

The defining feature is syngamy: fusion of cells from different individuals to produce offspring

Sex reproduction consists of meiosis - a cell division that reduces the genetic material in cells by half - followed by fusion of cells from different individuals

meiosis produces BLANK

Meiosis produces variation among gametes

Crossing over produces variation in the reproduction process

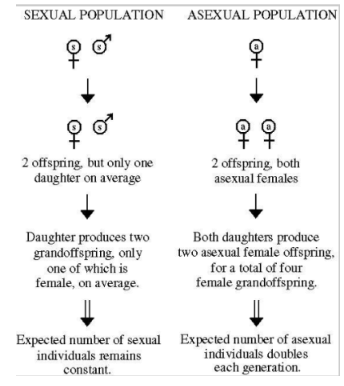

The Paradox of Sexual Reproduction

Evolutionary cost: sexually-reproducing females produce half as many daughters as asexual females

Asexual right, female makes two offspring, those two because asexual and clones, they can also produce 2 offspring

See with each generation the population is growing

Direct descendants of original

Sexual, female makes 2 offspring, one female one male, only female then goes on to produce 2 offspring, one of those male

If sexually reproducing population with fixed offspring number of 2, population number does not grow

Asexual can grow rapidly, all offspring produced can produce offspring

Question of why sexual reproduction, comes at cost but yes variation

Other costs of sexual reproduction

Finding a mate - Competition, travel, predation risk

Cost of social strategies is that you have to go out and find conspecifics to get benefit, same thing sexual, go out find mate is costly, have to travel, expose to predation risk, competition with other individuals, mating can be dangerous, some species have cannibalism in mating

Sexually transmitted pathogens and parasites - Exploit sexual contact to move from host to host

Recombination breaks up favourable genotypes - Combining genes with another individual breaks up g

Not only are you not producing as many offspring, but also due to all of the recombination component of meiosis, potential breaking up valuable combinations of genes

Yes adding variation, but if its breaking up some combination of genes that's super effective, because it's not controlled variation

Asexual Reproduction an Evolutionary Dead End

Not an absolute rule

Very few large taxonomic groups are asexual

asexual species are evolutionarily young

Asexual species typically have a restricted range

Lots of costs, maybe asexual?

Asexual is thought to be evolutionary dead end, don't get branching trees with large taxonomic groups

No variation = not as much speciation, rely on mutation to introduce variation

Usually small taxa because not same level speciation

Also restricted range

Physical range, because their really good at the particular environment where they evolved

If something changes in environment, no way to adapt because no variation to give greater range of behavior or adaptations

Benefits of sexual reproduction:

Combines advantageous alleles from different individuals into the same individual

Prevents accumulation of disadvantageous mutations (slows the action of Muller’s ratchet)

If asexual, mullers ratchet, once you get mutation, always with you because no variation

But when have selective pressure and recombination and mixing genetic information, it's possible to get rid of something bad in sexual population

Sexual/asexual options liver fluke

Liver flukes (Trematode parasites) reproduce asexually in snail host and sexually in cattle host

Asexual, see as being beneficial if nothing in environment changing, don't need variation, perfectly set for where you are, have greatest population growth (snail)

If environment changing alot, want variability in population so that if something changes you have group that can be successful (cattle moves around a lot)

The evolution of males and females

Isogamy is unstable

There is a selective advantage to reducing investment in each gamete.

Producing many small gametes (carrying only DNA) may lead to greater reproductive success

There is a selective advantage to increasing investment in each gamete.

Producing fewer, larger, nutrient-rich gametes may lead to greater reproductive success.

These differences in gamete strategies lead eventually to differences in phenotype and behaviour

Females invest in really large nutrient rich gametes, males invest in large number of smaller gametes

Why Choose? Sequential hermaphroditism in coral reef fish

Example of sort of pressure to result in changes in reproductive strategy happen in coral reef fish wrasse

In this fish it starts out female, in environment with dominant male, fish grow in lifetime

Dominant male dies, largest female switches to male and takes on that reproductive strategy to fill gap of dominant male

Making change in reproductive strategy based on what strategy in the current circumstances gie greatest reproductive output

Male and female as reproductive strategies

protandry vs protogyny

Protandry: beginning life male and changing to female

Protogyny: beginning life female and changing to male

Sexual Selection

. . . the advantage which certain individuals have over others of the same sex and species in exclusive relation to reproduction.

Charles Darwin, 1871 The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex

Intra-sexual selection vs inter-sexual selection

Competition between members of the same sex. Intra-sexual selection, usually between males.

ex. stag beetle fighting with antlers to defend territory

Competition to be chosen as a mate by the opposite sex. Inter-sexual, usually males competing to be chosen by females

ex. birds of paradise, choosy females driven by evolution of displays

Why choose a mate on the basis of appearance or display? 3 reasons

Runaway sexual selection

Sensory bias

Appearance indicates mate “quality”

Runaway Sexual Selection

Definition: Runaway sexual selection occurs when a female preference for a male trait and the male trait itself become genetically correlated, causing both to increase together across generations, leading to exaggerated traits.

Core idea (Fisher):

Females prefer a particular male trait (e.g., longer eye stalks).

Females that choose those males produce offspring that inherit both the preference (in daughters) and the trait (in sons).

This creates genetic covariance between preference and trait.

How covariance forms (step-by-step):

A female with preference P mates with a male with trait T.

Their offspring tend to carry both P and T.

Females without the preference mate randomly, producing a mix of offspring.

Over generations, P and T become correlated in the population.

Population consequence:

The trait (T) increases in frequency because preferred males reproduce more.

The preference (P) increases because it is passed on by successful females.

Preference and trait “snowball” together, while p (no preference) and t (no trait) decline.

Result over time:

Eventually, most or all males express the exaggerated trait.

Most or all females share the preference and carry genes for the trait.

The trait can become extreme, even if it has survival costs.

key requirements for runaway selection

A mating preference in at least one sex (often females).

A reproductive advantage for males that express the preferred trait.

Sensory Bias

Definition: Sensory bias occurs when a male trait is attractive because it exploits a pre-existing bias in the female’s sensory or perceptual system, rather than evolving alongside the preference.

Key idea:

Females already have a bias in how they perceive or respond to stimuli (e.g., shape, color, movement).

A male trait evolves that matches or exaggerates this bias, making males more attractive.

Swordtail example (classic case):

In swordtail fish, males have an elongated “sword” on the tail; females do not.

The sword is a sexually selected trait.

Closely related species lack swords, but females in those species still prefer males with artificial swords.

Why this matters:

Phylogenetic evidence shows the female preference existed before the male sword evolved.

This means the preference did not arise because of the sword—it was already present.

Experimental evidence:

Females from non-sworded species spend more time with males (or images) that have longer swords, even though their own males never evolved swords.

Preference strength increases with sword length.

Conclusion:

The female sensory system was biased toward sword-like shapes before the trait existed.

Male swords evolved later by exploiting this sensory bias.

sensory bias vs runaway selection

Runaway selection: preference and trait evolve together via genetic covariance.

Sensory bias: preference comes first, trait evolves afterward to exploit it.

Mate Quality

Sexually selected traits may act as indicators of genetic or non-genetic quality of a potential mate:

current health and nutrition

parasite or disease resistance

competitive ability

developmental history

resources

Traits that indicate male quality have to be “BLANK” (or females should ignore them).

Traits that indicate male quality have to be “honest” (or females should ignore them).

What kind of traits are honest?

Body size

Parasite and pathogen resistance

Resistance to developmental stress

Hamilton & Zuk Hypothesis

Question: Do females use secondary sexual characteristics (e.g., bright plumage) to assess a male’s resistance to parasites?

Core idea: Sexually selected traits are honest signals of parasite resistance, not just general “quality.”

Prediction:

If plumage brightness signals resistance, brighter males should have fewer parasites.

This relationship should appear in males (the choosy sex’s targets), not females.

Evidence (birds, esp. small perching species):

Studies show a negative correlation between plumage brightness and blood parasite load in males.

As male plumage brightness increases, parasite load decreases.

This pattern holds across regions (e.g., North America and Europe) and when data are pooled.

Sex difference:

No similar relationship in females: female plumage brightness does not predict parasite load.

This matches expectations if female choice is driving selection on males.

Interpretation:

Bright plumage is costly to produce and maintain, especially under parasite pressure.

Only males with effective immune defenses can afford bright displays → honest signaling.

Conclusion:

Strong support for the Hamilton & Zuk hypothesis: females prefer males whose displays reliably indicate low parasite burden / high resistance.

The absence of the pattern in females strengthens the case that this is about mate choice, not general coloration.

Developmental Stress Hypothesis

Stress during early development affects brain development, and these effects are later revealed in sexually selected traits, especially bird song

Implication for mate choice: Male song quality in adulthood reflects how well a male withstood developmental stress, providing females with information about male quality and potential genetic benefits.

Developmental Stress Hypothesis - Zebra Finch Bird Song

Key result:

Despite similar adult size, plumage, and appearance, males exposed to early stress produced simpler songs as adults.

Measures affected included fewer total syllables, fewer unique syllables, and reduced song complexity.

Conclusion:

Adult song quality honestly reflects early developmental stress, even when no visible differences remain.

Song is therefore an honest signal of developmental history and neural quality.

Evolutionary significance:

Females choosing males with complex songs may gain genetic or developmental advantages for offspring.

Supports the idea that sexual signals can reveal hidden costs of early stress.

Exam takeaway:

Developmental stress → altered brain development → reduced adult song complexity → honest indicator of male quality used in mate choice.

monnogamy, polygyny, polyandry, promiscuity/polygamy

Monogamy - male and female pair

Polygyny - male with multiple females

Polyandry - female with multiple males

Promiscuity/Polygamy - males and females have multiple mates

Parental Care Affects Mating System - with vs without male care

When males provide little or no parental care

Selection favors polygyny (one male mates with multiple females).

Females invest heavily in offspring (eggs, gestation, care), so they are choosier.

Males compete with each other for access to females.

Male reproductive success is limited by number of mates, not offspring survival.

Ecological effects matter:

If resources are patchy and defensible, males can control high-quality territories.

Females cluster in those territories → resource-defense polygyny.

Common outcomes:

Strong male–male competition

Pronounced sexual dimorphism

Elaborate male displays or weapons

When males provide substantial parental care

Selection favors monogamy.

Offspring survival depends on care from both parents.

A male that deserts to seek new mates risks lower offspring survival.

Male reproductive success is limited by parental investment, not mating opportunities.

Leads to:

Pair bonds

Reduced sexual dimorphism

Mutual mate choice

Polyandry

is a mating system in which the variance in female reproductive success is greater than the variance in male reproductive success

andros = man or husband

Polygyny - define

is a mating system in which the variance in male reproductive success is greater than the variance in female reproductive success.

gyn – woman or wife (Greek)

Females are offspring-limited; males are mate-limited

Occurs via mate defense or resource defense, depending on ecology.

Polygyny is best described by …

Polygyny is best described by variance in reproductive success, not just number of mates.

In a population of 10 males and 10 females, where each female produces one offspring:

Females: all have the same reproductive success (variance ≈ 0).

Males: some have many offspring, others have zero → high variance.

Why variance differs between sexes:

Female reproductive success is limited by physiology (eggs, pregnancy, gestation, care).

Mating with more males usually does not increase number of offspring.

Male reproductive success is limited by number of mates.

More mates → more offspring.

Why do some males get more mates than others?

Because they can control access to females or to resources females need.

Types of Polygyny

1. Mate-defense polygyny

Males directly defend and monopolize groups of females.

Males compete aggressively; only the strongest succeed.

Leads to extreme variance in male reproductive success.

Example: Elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris)

Dominant males defend harems of females on beaches.

Subordinate males often get no matings at all.

2. Resource-defense polygyny

Males defend valuable resources, not females directly.

Females cluster where resources are best, giving territory-holding males greater mating access.

Works best when resources are clumped and defensible.

Example: Side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana)

Males defend warm rock territories.

Females move into these areas for thermoregulation, and males gain mating opportunities.

Polygyny Threshold Model

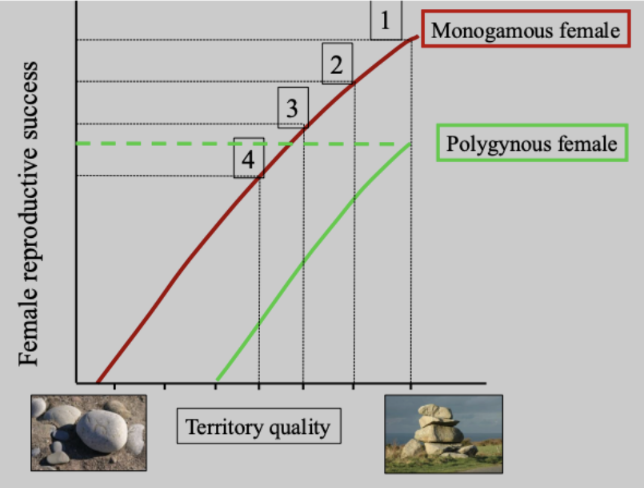

Core idea: Female mating decisions depend on a trade-off between territory quality and sharing a male.

Females choose the option that maximizes their reproductive success.

Axes of the model:

Y-axis: Female reproductive success

X-axis: Territory quality (resources, nesting sites, food)

Step-by-step logic:

First female: Chooses the highest-quality territory and mates monogamously → highest reproductive success.

Second female: Chooses the next-best territory and mates monogamously → still higher success than sharing.

Third female: Same logic—monogamy on a slightly lower-quality territory still pays off.

Fourth female: Now faces a choice:

Monogamy on a low-quality territory, or

Polygyny with a male on a very high-quality territory.

If sharing the top territory yields higher reproductive success, she chooses polygyny.

The “polygyny threshold”:

The minimum difference in territory quality needed to offset the costs of sharing a male.

Below this threshold → monogamy favored.

Above this threshold → polygyny favored.

Key assumptions:

Territory quality varies and is defensible by males.

High-quality territories can support multiple females.

Females are free to choose and can assess territory quality.

Big takeaway:

Females do not mate polygynously by default.

Polygyny occurs when a high-quality territory provides enough benefits to outweigh reduced male attention.

Female reproductive success does increase with number of mates in a polyandrous breeding system because…

In birds, males can incubate.

Happens in birds because males can incubate eggs, critical component in birds

Clutch size may be limited but females can lay more than one clutch of eggs.

Females still have to produce and lay eggs, still limit on reproductive output, but can lay multiple clutches, which are cared for by the males

If food is plentiful, and young are precocial, a single male may be able to raise off

Only happens when lots of food available, and young can take care of themselves quite early on in life

Reduces parental care needs

In a polyandrous breeding system

Females may have conspicuous appearance and display

Females compete for territories and males

Males are choosy

Covert Polyandry (Extra-Pair Copulation, EPC)

Definition: Covert polyandry occurs when a female is socially monogamous (pair-bonded) but mates with multiple males, resulting in offspring with different genetic and social parents.

Key distinction:

Social parent: The individual providing care (behavioral mate).

Genetic parent: The individual that actually fertilized the egg.

These can be different males.

Why females engage in EPCs (potential benefits):

“Good genes”: mating with a high-quality male (e.g., better song, health).

Compatible genes: increased genetic compatibility or heterozygosity.

Material benefits: retain parental care from the social mate while gaining genetic benefits from another male.

Example strategy: care from social mate + genes from extra-pair male.

Chickadee example:

Chickadees are socially monogamous, yet ~37% of offspring show extra-pair paternity.

DNA banding (genetic fingerprinting) compares shared bands between offspring and parents.

Result:

Offspring often share fewer bands with the social father and show unique bands, indicating another male contributed genetically.

No such pattern with the mother → maternity is consistent, paternity is not.

Interpretation:

Females remain socially paired but genetically mate with multiple males.

Confirms covert polyandry: social monogamy does not equal genetic monogamy.

Lek Mating System

Definition (lek): A mating system where males aggregate in a display area (lek), defend small display territories, and females visit only to choose mates.

Males provide no parental care.

Leks = female choice + intense male competition, no male care.

Lek Mating System Ruff example

Ruff example:

Male ruffs show extreme plumage variation, especially in collar (“ruff”) color and pattern.

Females lack these exaggerated traits.

Lek structure:

A focal female moves through the lek.

Males surround her, each performing courtship displays from tiny territories.

Male mating strategies (polymorphism):

Dominant (territorial) males

Often have dark or colored ruffs.

Defend small territories aggressively.

Fight other dominant males to maintain space and access to females.

Satellite males

Often have white collars.

Do not defend territories and avoid fights.

Sneak matings by exploiting moments when dominant males are distracted by conflicts.

Key dynamics:

Dominant males gain matings through territorial control and display.

Satellite males gain matings through alternative tactics (sneaking).

Both strategies persist because each can yield reproductive success under different conditions.

Evolutionarily Stable Strategy

The strategy that when adopted by most members of the population cannot be beaten by any other strategy (John Maynard Smith) because both yeild equal fitness payoffs at equilibrium

A balance of the strategies in the population

Not beaten by any other strategy

Payoffs for each strategy equal

Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS): Hawk–Dove Model

Hawk = aggressive/dominant strategy

Fights for the resource (e.g., mating opportunity).

Risk of injury.

Dove = non-aggressive/satellite strategy

Avoids fighting, uses display or sneaking.

Pays a small display cost.

Interaction Payoffs (conceptual)

Hawk vs Hawk:

Both fight → high injury risk.

Payoff = (V−W)/2 (costly, can be negative).

Hawk vs Dove:

Dove retreats → Hawk gets V, no injury.

Dove vs Hawk:

Dove gets 0.

Dove vs Dove:

No fighting, display only.

Each has ~50/50 chance of winning → small positive payoff (V/2−T)

Stable Mixture (ESS)

There is a specific proportion of hawks and doves where:

Average payoff of Hawk = Average payoff of Dove.

At this point, neither strategy has a fitness advantage.

If proportions shift away from this balance, selection pushes them back.

The success of a strategy depends on how common the other strategy is.

Hawk in a dove-heavy population → does very well.

Hawk in a hawk-heavy population → does poorly (injury costs).

Dove in a hawk-heavy population → poor.

Dove in a dove-heavy population → does okay.

Great Golden Digger Wasp (Sphex ichneumoneus): 2 strategies and outcomes

Key idea: Females (foundresses) can choose between two alternative strategies, and the payoff of each depends on how common the other strategy is (frequency-dependent selection), similar to ESS models.

The Two Strategies

Dig strategy

Female digs a new burrow, provisions it, and lays an egg.

Enter strategy

Female enters an existing burrow that she finds.

Dig strategy (three outcomes):

Best payoff:

Female founds a nest and remains alone → full reproductive success.

Intermediate payoff:

Female founds a nest but is later joined by another female → only one female reproduces.

Worst payoff:

Burrow is abandoned or disrupted → no reproductive success.

Enter strategy (three outcomes):

Best payoff:

Female enters an abandoned burrow, is alone → full reproductive success.

Intermediate payoff:

Female enters a burrow, later another female joins → only one reproduces.

Worst payoff:

Female enters a burrow already occupied → competition, only one lays an egg.

Great Golden Digger Wasp (Sphex ichneumoneus): frequency dependence

The success of each strategy depends on how many females use the other strategy:

If few females dig, there are few burrows → entering becomes less profitable.

If many females dig, more burrows are available → entering becomes more profitable.

If too many enter, competition increases and payoffs drop.

Neither strategy is universally best; each does better when it is rare.

Why both strategies persist

Just like alternative mating strategies, no single strategy always dominates.

Stable proportions of diggers and enterers emerge because average payoffs equalize.

This maintains behavioral polymorphism in the population.

Side-Blotched Lizard (Uta stansburiana): Alternative Mating Strategies (Rock–Paper–Scissors)

Key idea: Male side-blotched lizards have three genetically determined throat colors, each linked to a distinct mating strategy.

The success of each strategy depends on the frequency of the other strategies → negative frequency-dependent selection.

The Three Strategies

Orange (Rock)

Highly aggressive, defend large territories with multiple females (polygyny).

Weakness: cannot guard all females at once.

Yellow (Paper)

Sneaker strategy; mimics females and steals matings from orange males when they are distracted.

Paper beats Rock.

Blue (Scissors)

Monogamous and vigilant; closely guards one female.

Resistant to sneakers because of constant mate guarding.

Scissors beat Paper.

Orange beats Blue → extreme aggression overwhelms blue males.

Blue beats Yellow → vigilance prevents sneaky matings.

Yellow beats Orange → sneaks matings when orange males can’t defend everything.

No single strategy is best in all contexts.

When one strategy becomes common, another gains an advantage.

This cycling maintains all three strategies in stable proportions.

How does courtship work in a species without vision (e.g., blind cavefish)?

In blind cavefish, courtship behavior is nearly identical to that of surface-dwelling fish with eyes.

Both perform the same sequence: chase → paired swimming → upward loop → release of sperm and eggs.

This shows that vision is not the primary sensory system guiding courtship in these fish.

Instead, cavefish rely more on chemical cues (pheromones).

Experiments show blind cavefish males increase mating behaviors (chase, quiver) when exposed to female pheromones, while surface fish do not respond as strongly.

Conclusion: Courtship structure is conserved, but sensory mechanisms differ—cavefish depend more on chemical signaling.

How/why do female or dueting displays evolve? - 3 main reason

Male parental care (investment shifts choosiness to males).

Pair bonding needs in high-care systems (duetting maintains bonds).

Access to resources provided by males (e.g., nuptial gifts), especially under scarcity.

How / Why Female or Duetting Displays Evolve (Parental Care, Pair Bonding, & Resources)

Parental care drives sex-role reversal:

Typically, females are choosier because they invest more per offspring (large gametes).

When males provide substantial parental care, their investment increases and males become the choosier sex, shifting courtship toward females or mutual displays.

Pair bonding and duetting:

In species with high parental care and social monogamy, mutual (duet) displays evolve to establish and maintain pair bonds.

Example: Blue-footed booby—both sexes coordinate displays (e.g., foot displays), similar to grebes.

Stronger, longer-lasting pair bonds are associated with higher reproductive success across years.

Resource-based role reversal (nuptial gifts):

When males provide valuable resources (e.g., nuptial gifts), females may compete for access.

Example: Butterflies with seasonal forms:

Dry season females (low resources) develop more elaborate UV eye spots and engage in active courtship.

Increased mating yields nuptial gifts, boosting female longevity in resource-poor conditions.

Wet season females (high resources) show less elaborate traits and less courtship.

Are Courtship Displays Learned? (Manakins example)

In multi-male courtship systems (leks), many males display together, but only high-ranking adult males mate; younger males usually do not.

This pattern suggests courtship displays have a developmental and learned component, not just genetic control.

In manakins, juveniles spend time near displaying adult males, observing and associating with them before they ever mate.

Juveniles that are more socially connected to skilled adult males learn displays better.

Studies show a positive relationship between juvenile social connectivity and adult mating success.

Males with stronger juvenile social networks rise faster in rank and perform more effective courtship displays as adults.

Conclusion: Courtship displays involve both motor learning and social learning, and learning opportunities during youth strongly affect adult success.

How Do Complex Courtship Displays Evolve? How Do We Study Them?

Comparative method: Compare distantly related species with similar displays and closely related species with different display complexity to infer evolutionary drivers.

Convergence in the tropics:

Manakins (South America) and birds-of-paradise (Indonesia) both show extremely complex displays.

Shared factor: tropical environments with high productivity.

Role of diet and energy:

Tropics provide abundant fruit, a quick and reliable energy source.

When males spend less time foraging, they can invest more time and energy in elaborate courtship displays.

Comparative analyses show a link between fruit-eating ability and display complexity.

Innovation builds on anatomy:

Example: Club-winged manakin produces sound by rubbing specialized wing feathers over ridged bones (violin-like).

Small anatomical changes enable new display components.

Stepwise evolution within lineages:

Not all manakins are equally elaborate.

Comparing closely related species reveals a gradual addition of components:

Flycatchers (ancestral relatives): simple wing flicks.

Basal tyrant-manakins: more frequent wing flicks, small hops, added color.

Derived manakins: jumps, flips, sounds, coordinated movements.

Even “simple” displays can be surprisingly complex when analyzed closely.

Putting it together:

Researchers map display traits onto phylogenies, alongside ecology (diet, habitat).

This reveals transition points where new elements are added, explaining how spectacular displays evolved from simpler behaviors.

Bottom line:

Complex displays evolve incrementally, fueled by ecology (fruit-based energy) and shaped by female choice, and are best understood using the comparative method rather than studying only the final, extreme forms.

Not All “Simple” Displays Are Simple - flicker fusion frequency

Some displays that look simple to us are actually highly complex, just too fast for human vision to resolve.

Example: a black bird that appears to “just hop” is actually performing a rapid backflip, which we cannot see clearly.

Under Tinbergen’s framework, the display only makes sense if females can perceive it, even if humans cannot.

This difference comes from critical flicker–fusion frequency (CFF): the rate at which flickering light appears continuous.

Birds have much higher CFFs than humans, meaning they process visual information faster and see rapid movements in more detail.

Human vision fuses around 60–80 Hz, while many birds can process much higher rates, especially under bright light.

Higher CFF allows birds to detect fast movements, making rapid displays meaningful signals.

Just as birds can track fast-flying insects that appear like blurs to us, they can perceive courtship movements that look simple or invisible to human observers.

Species with vs without parental care for young

In many species, parents provide no care for the young:

Most insects, amphibians and reptiles (e.g. sea turtles)

Instances where parent lays the egg and leaves, no incubation, nothing

Ex. digger wasps, bee wasps, catch a bee, put in burrow, lay egg and leave (yes nourishment prior to laying egg, but once lay egg they’re out)

In some species, parental care is the rule:

Some insects, amphibians and reptiles (e.g. crocodiles)

Lots in bumblebees

Many fish

All mammals, almost all birds

Mammary gland = milk = parental care

Avoiding Parental Care in Birds - specific term

Some birds avoid providing parental care altogether.

Brood parasites do this by laying their eggs in the nests of other species, which then raise their young.

The offspring still require care—it’s just provided by other birds, not the parents.

Avoiding parental care does not only occur via brood parasitism

Avoiding Parental Care in Birds - malleefowl

Malleefowl (SW Australia) avoid parental care by using an incubation mound.

The male builds and maintains a mound of sand and organic material that generates heat.

The female lays ~10–20 eggs, the clutch is buried, and the adults leave.

The male may regulate mound temperature (e.g., digging, adding/removing material), but does not care for chicks.

Chicks hatch underground, dig their way out, and are fully independent—no adult–chick interaction.

Key point: Birds can avoid parental care through brood parasitism or through environmental incubation systems like mounds, while offspring still develop successfully.

Animals provide parental care in many ways:

Food

Feeding young that can't forage, mammals providing milk

Heat for young unable to thermoregulate

Heat for developing eggs in birds and some reptiles

Protection from predators

Information (about food, predators, etc)

Juveniles developing courtship displays, lots of learning going on

Learning included in foraging, all foods parents bring back provides them with information on what they can eat

Care by female, male or both?

Uniparental female - Many mammals

Uniparental male - Many fish

Biparental care - Most birds

Why do females care? Specific hypothesis

Core idea: Females provide parental care because they have certainty of parentage—they lay the eggs and know the offspring are theirs.

Because care directly increases offspring survival, female investment always contributes to fitness.

Problem for males:

Males may invest in offspring that are not genetically theirs due to extra-pair matings.

Certainty of paternity varies, making care a potential fitness risk for males.

Prediction:

Males with higher certainty of paternity should invest more parental care.

Dunnock (Prunella modularis) example:

Mating systems vary:

Monogamous males → high paternity certainty.

Co-breeding (polyandrous) males → lower paternity certainty.

Result: Monogamous males make more visits to the nest (greater parental care) than co-breeding males.

Care and offspring success:

As male investment increases, the proportion of offspring that fledge increases.

This positive effect of care occurs regardless of mating system.

Key distinction:

Paternity certainty affects whether males invest, not whether care is effective.

When males do invest, it improves offspring success; when paternity is uncertain, males reduce investment.

Conclusion:

The paternity assurance hypothesis explains why females reliably provide care and why male care is conditional.

Females benefit more from care because their parentage is guaranteed, while males must weigh costs against uncertain genetic returns.

Why do males care?

General expectation: male reproduction is usually limited by number of mates, while female reproduction is limited by offspring production (eggs, gestation). This predicts low male parental care.

Why males might still care: in some species, males can care for many more offspring at once than any one female can produce. Caring does not strongly limit their mating opportunities.

Fish are key examples:

Males can attract multiple females and then care for all their eggs simultaneously.

Example: if each female produces ~50 eggs, a male may successfully care for 200+ eggs from several females.

Male stickleback:

Males provide extensive care (nest building, egg aeration, defense, retrieving fry).

Females invest mainly in egg production and can mate again quickly.

Parental care results in weight loss - St.Peter’s fish

Energetic costs differ between sexes:

Parental care causes weight loss and delays return to reproductive condition.

Females must maintain body condition to produce eggs, so care is more costly for them.

Mouth-brooding cichlid (St. Peter’s fish):

Either sex may brood eggs in the mouth.

Brooding parents lose weight and delay reproduction.

Key comparison (inter-spawn interval):

Females that provide care have a much longer delay before producing the next clutch.

Males that provide care also slow down, but far less than females.

Conclusion:

When parental care reduces female reproduction much more than male reproduction, selection favors male parental care.

This increases overall reproductive output of the population.

Big idea: males care when caring does not strongly limit mating and allows them to maximize total offspring produced.

Why would a host care for a brood parasite egg/hatchling? specific term

Evolutionary Arms Race:

Hosts and parasites are in an evolutionary battle between adaptations for parasitic birds to avoid the detection of parasitism and for hosts to increase detection

Egg Detection - Parasitic Cuckoo Finch vs African tawny-flanked Prinia

Prinia have evolved such that each female lays eggs of a particular colour, which allows for the identification and removal of foreign eggs

Arms race because parasite is also changing color of eggs through selective pressures, which successfully hatch out, sometimes good match, their eggs would be missed by host, but sometimes poor match

Nestling Behavior

Young cuckoo hatches, warbler feeds it, young cuckoo needs to throw other eggs out because if not the warbler won’t be able to feed all nestlings

Cuckoo much bigger than warbler, but still treated as a nestling, even after left the nest will still feed it

High rates of this parasitism = can be damaging to host populations

Who is benefiting from siblicide

There is a benefit to the successful offspring who then gain access to more resources after outcompeting their siblings.

Is there a benefit to the parents?

Is there a fitness benefit by having the siblings compete?

Or is this a source of parent-offspring conflict?

Is this something the offspring are doing that the parents would prefer not to happen?

How does brood timing impact parent fitness?

Great egrets lay eggs approx. 1.5 days apart

This results in siblings hatching at different times and gives the older siblings an advantage in sibling conflict

The egg laying timing seems to enhance the likelihood of siblicide…

Normal asynchronous incubation brooding/incubation/laying time is creating the most efficient situation for parents

Big factor is food brought in to survivors, lots species where when resources are abundant, dot see siblicide, and high competition can lead to this conflict

The efficiency seems to be a key feature here

The offspring successful benefit from that conflict, get parental resources, parents benefit in terms of overall efficiency

Parental investment - definition

Anything done for the offspring that benefits offspring while decreasing parental fitness (e.g. other existing offspring, future reproduction, aid to kin).

To qualify as “parental investment”, the behaviour must have a cost.

Robert Trivers developed the idea of parental investment

This can help to explain some parent-offspring conflict

Conflict over how much investment parents should provide

Conflict over when investment should end

Key idea: As offspring grow, the benefits of parental care decrease, while the costs increase because continued care delays future reproduction.

Benefits curve:

Early in development, parental care has huge benefits (offspring survival depends on it).

As offspring become more independent, additional care yields smaller gains.

Costs curve:

Early on, costs to parents can be low or near zero (they may not be able to reproduce yet anyway).

Over time, costs increase because continued care delays investment in future offspring.

Different perspectives:

Parents are equally related to current and future offspring → they bear the full cost of delaying reproduction.

Offspring are fully related to themselves but only half-related to future siblings → they experience only half the cost of continued care (inclusive fitness).

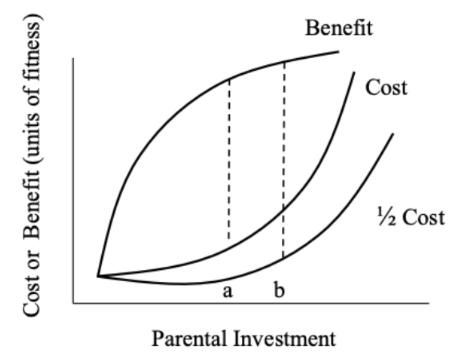

conflict over amount of parental investment

Conflict point:

Parents maximize fitness by stopping care at point A, where the difference between benefit and cost is greatest for them.

Offspring prefer care to continue until point B, where the benefit–cost difference is greatest for them.

The region between A and B is where parent–offspring conflict occurs.

What the conflict is about:

Can be about how much care is provided or how long care continues.

Important note:

If there is no chance of future reproduction, the cost of continued care disappears, and parent–offspring conflict is reduced or absent.

Bottom line:

Parents are selected to invest less than offspring are selected to demand, creating family conflict over parental investment.

recognition failure

Host birds fail to recognize that their young are a different species despite glaringly obvious differences between them and their own young

ex. wreed warbler feeding giant cuckoo

Colony nesting Mexican free-tailed bats can identify their own young from the huge numbers of seemingly identical begging young

Why can’t host birds recognize their young?

The bats need to be able to identify their young in a large group of similar individuals, but typically birds only find their own young in their nest

There typically isn’t pressure to evolve an individual recognition mechanism in solitary species

Mistakenly rejecting young can be very costly

Cuckoo offspring are more hidden that it may initially seem

Call mimicking

We look at wreed warbler and cuckoo, depends on what recognition mechanisms are

Bats recognize offspring using olfaction and vocalization

Many brood parasites are good at mimicking things like nestling calls

Birds recognizing vocally

Why would a host care for a brood parasite egg/hatchling?

Evolutionary Arms Race:

Hosts and parasites are in an evolutionary battle between adaptations for parasitic birds to avoid the detection of parasitism and for hosts to increase detection

parasitic cucko finch vs prinia

prinia lays identifiable eggs,m can kick out cuckoo’s

How does the cuckoo finch fight back against the egg identification of the prinia?

Try to match egg colouration as closely as possible

Repeatedly parasitize the same bird to disrupt the mechanism through which it identifies its own eggs?

Changing how similar they looked and ratio of host egg to foreign egg