Classification of voice problems

1/7

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

8 Terms

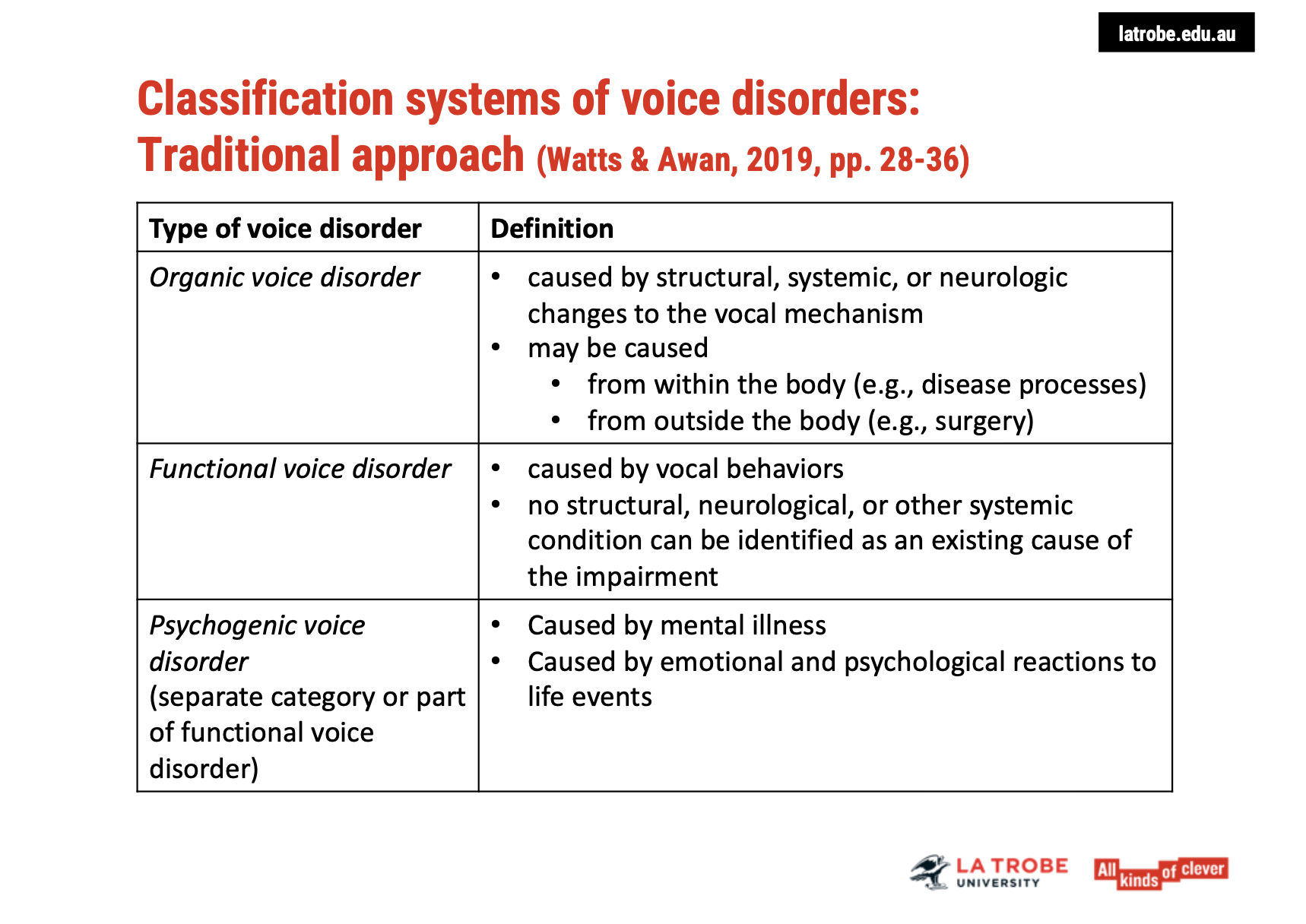

Classification Systems of Voice Disorders

Categories of Voice Disorders:

Organic Voice Disorders:

Definition: Caused by structural, systemic, or neurological changes to the vocal mechanism.

Causes: These changes may result from disease processes within the body (e.g., cancer, infection) or from external factors like surgery.

Functional Voice Disorders:

Definition: Caused by vocal behaviours without any identifiable structural, neurological, or systemic condition.

Nature: These are considered non-organic voice disorders, often linked to the way the vocal system is used or misused (e.g., overuse, improper technique).

Psychogenic Voice Disorders:

Definition: Commonly linked to mental illness, but also seen as arising from emotional and psychological reactions to life events.

Approach: This view is more holistic, focusing on the mind-body connection and the role of stress or trauma, and avoids pathologizing the individual.

Considerations:

The classification system separates voice disorders based on etiology—whether the cause is structural, related to vocal behaviours, or linked to psychological factors.

Psychogenic disorders might be seen separately or within the broader category of functional disorders, depending on the clinical approach.

📝 Key Takeaway:

Understanding voice disorders requires considering a range of factors—from physical changes to behavioural patternsto mental health influences. A comprehensive approach avoids limiting diagnosis and treatment to one narrow category, instead integrating all potential causes.

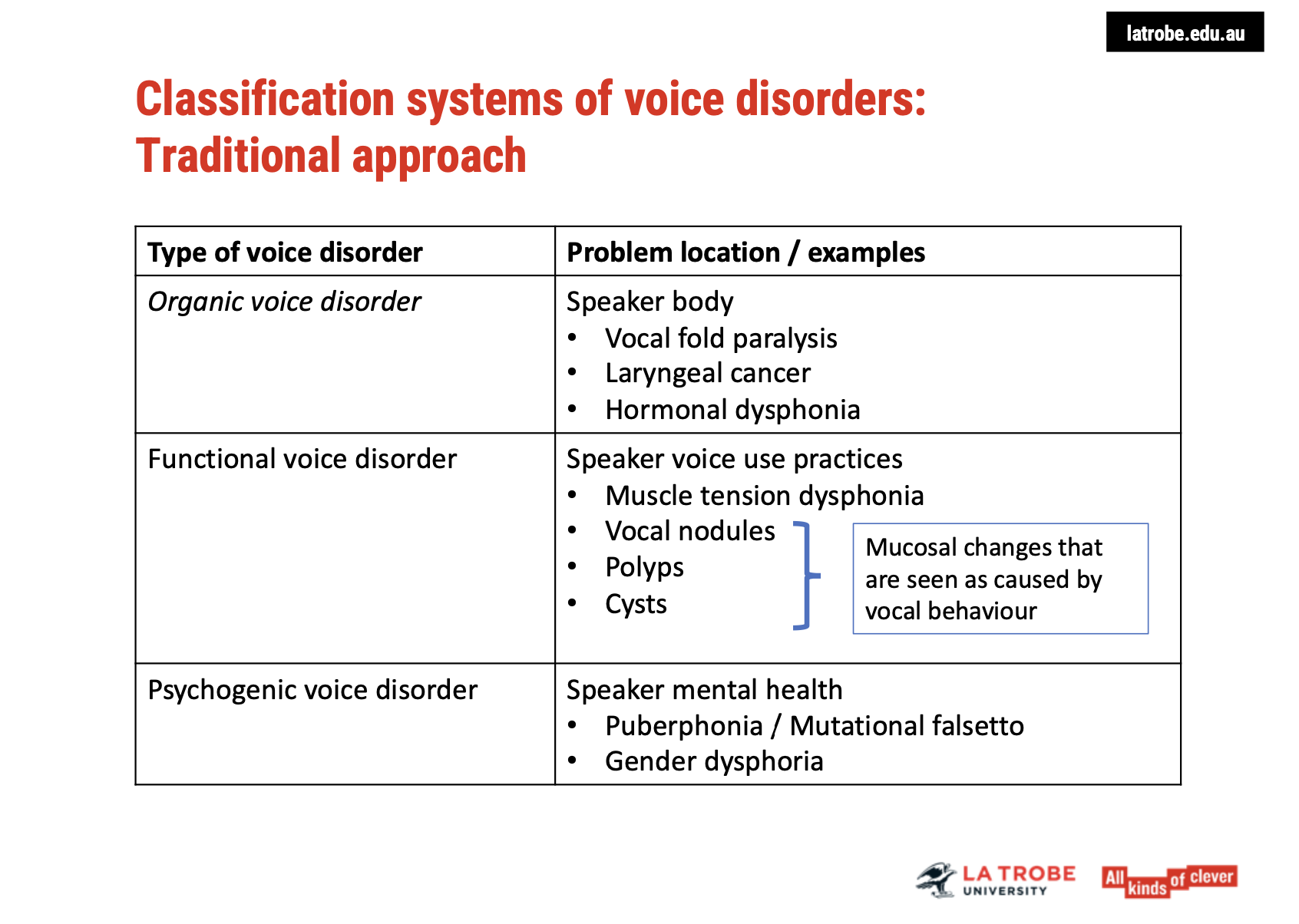

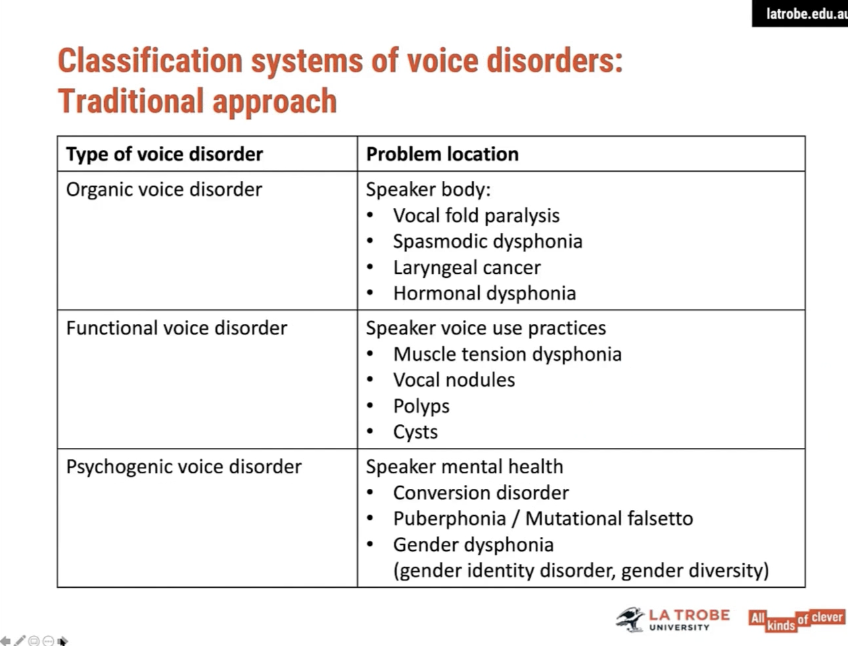

Examples and Locations of Voice Disorders

Organic Voice Disorders:

Location: The speaker's body (i.e., structural or physiological changes to the vocal mechanism).

Examples:

Vocal Fold Paralysis: Loss of motor function in the vocal cords.

Laryngeal Cancer: Cancer affecting the larynx and vocal folds.

Hormonal Dysphonia: Voice issues caused by hormonal changes, such as those from hormone therapy.

Functional Voice Disorders:

Location: Voice use practices (linked to how the voice is used, not a structural issue).

Examples:

Muscle Tension Dysphonia: Caused by excessive tension in the vocal muscles.

Vocal Nodules, Polyps, and Cysts: These appear as mucosal changes on the vocal folds, but are caused by vocal misuse, not internal disease processes.

It's important to note that vocal nodules, polyps, and cysts are viewed as resulting from vocal behaviour rather than internal diseases or conditions.

Psychogenic Voice Disorders:

Location: Within the speaker's mental health (linked to emotional or psychological factors).

Examples:

Puberphonia or Mutational Falsetto: The persistence of a high-pitched voice post-puberty, often linked to psychological or emotional factors.

Gender Dysphoria: A psychiatric condition where a person’s gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth, which historically contributed to voice problems being classified as psychogenic disorders.

Key Points:

Organic disorders relate to structural or systemic issues in the vocal mechanism.

Functional disorders are caused by poor vocal habits or misuse, even if there are observable changes on the vocal folds.

Psychogenic disorders stem from psychological or emotional factors, affecting the way the voice is produced or perceived.

Limitations of Traditional Classification Systems for Voice Disorders

Pathologizing the Speaker

Issue: Traditional classification systems focus primarily on locating the problem solely within the speaker's body or mind, which can lead to pathologizing the speaker.

Risk: This approach doesn’t account for external influences or broader factors that contribute to the voice disorder.

Missed Influences on Voice Production

Other Factors: There are several influences on voice production that go beyond the individual, such as:

Conversation Partners: How the interaction affects voice use.

Professionals' Impact: The role of health professionals and their practices.

Supra-individual Forces: Social, environmental, and cultural factors that shape voice use and health.

Iatrogenic Voice Disorders:

Definition: Voice disorders that result from medical practices.

Examples:

Thyroid surgery

Intubation during surgeries

Issue: Medical professionals may contribute to voice disorders but are often not acknowledged in the classification system.

External Traumas and Environmental Factors:

Examples:

Exposure to smoke, poisonous gases, or asbestos can negatively affect the voice.

Classification Problem: How do we classify external trauma as a cause for voice disorders?

Minority Stress:

Impact: Minority stress (discrimination, societal exclusion, etc.) can affect voice health, but it's often overlooked.

Traditional Classification: The stressors affecting minority groups are often attributed to psychological instability, rather than recognizing external societal pressures.

Voice Use Settings:

Context: The settings in which a person uses their voice (e.g., professional, social) can affect its health, but this isn't always considered in the traditional models.

Key Takeaway:

Traditional models need to expand to include factors beyond the individual, such as external trauma, iatrogenic influences, minority stress, and environmental settings, to avoid pathologizing and better understand the root causes of voice disorders.

The Mind-Body Connection in Voice Production

Interplay Between Body, Behaviour, and Mind

Holistic Influence: Voice production is a result of a continuous interaction between:

Biophysiological Forces (e.g., vocal fold movement, respiration)

Voice Use Behaviours (e.g., speaking habits, vocal intensity)

Cognitive and Emotional Factors (e.g., stress, mood, mental state)

No Separation: The idea of separating body, behaviour, and mind is problematic, as recent research highlights that these aspects are inseparable in the production of voice.

Biophysiological Forces Alone Are Not Enough

Focusing solely on biophysiological forces in voice assessment and treatment does not capture the full complexityof voice production.

Recent Research: Mind-body systems are interconnected, meaning mental and emotional states directly influence physical voice production and vice versa.

Implications for Voice Assessment and Treatment

We must consider all contributing factors—including cognitive, emotional, and physical elements—in understanding and addressing voice disorders.

Assumptions about which factor is most important may vary, but a comprehensive approach acknowledges that the mind-body system works together, not separately.

Key Takeaway:

Rather than separating the body, behaviour, and mind, voice practitioners should embrace a holistic understandingof how these forces interact and affect voice production, ensuring more effective and integrated treatment approaches.

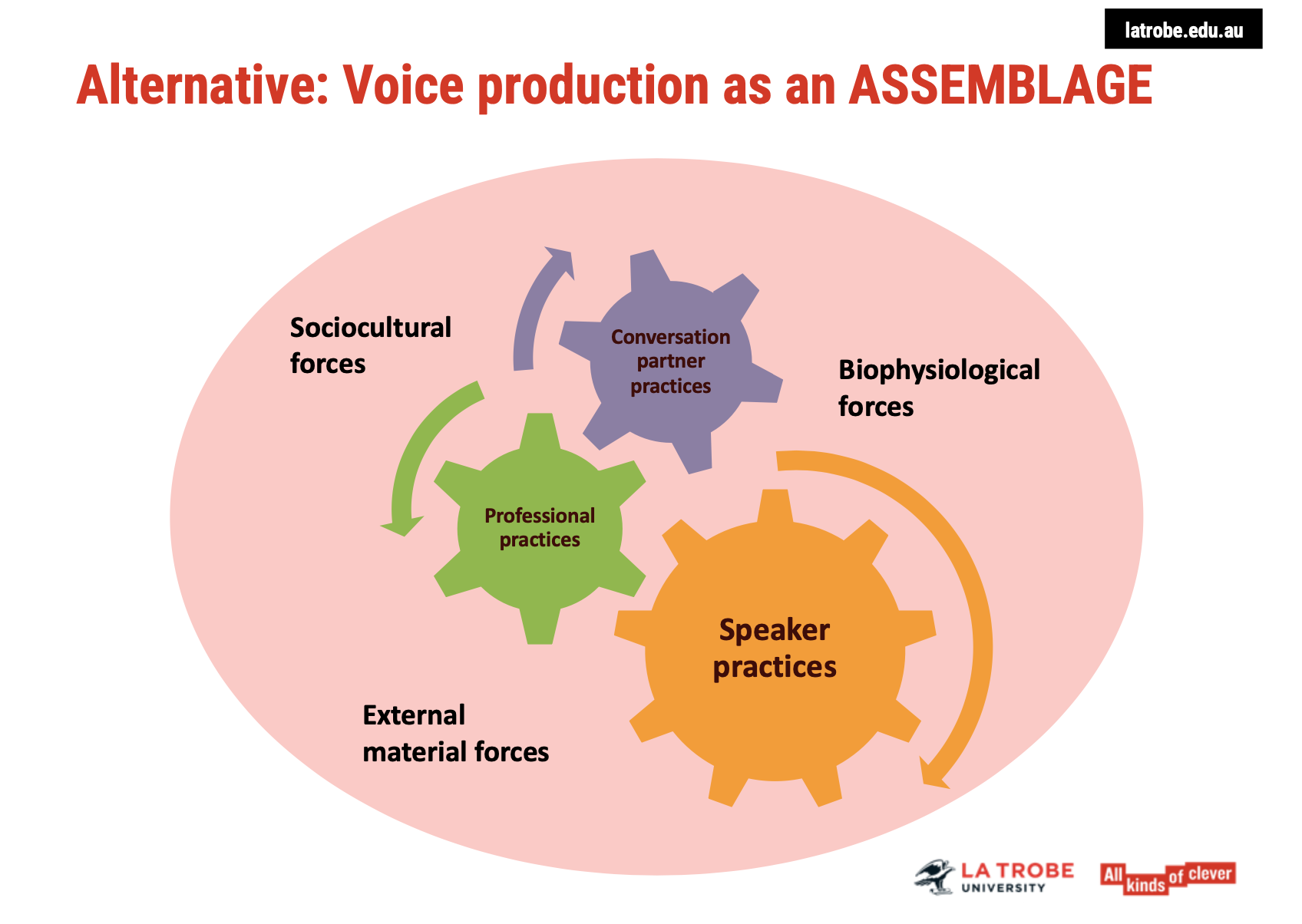

Alternative Approach to Voice Disorder Classification

Voice Production as an Assemblage

Holistic Perspective: Instead of isolating specific factors, this approach views voice production as a dynamic assemblage of various interacting forces:

Biophysiological factors (e.g., vocal fold function, respiratory patterns)

Voice use behaviours (e.g., speech patterns, vocal intensity)

Cognitive and emotional influences (e.g., stress, mental health)

External factors (e.g., environmental stressors, societal influences)

Voice Problems as Multifaceted

Influence of Multiple Forces: Voice issues are seen as arising from the interaction of all these forces, rather than being located in one isolated area (e.g., physical or mental).

Inclusive: This framework acknowledges all contributors—biological, psychological, and environmental—in the manifestation of voice disorders.

Implications for Practice

Practitioners are encouraged to move beyond strict categories (like organic, functional, and psychogenic) and adopt a more integrated approach.

Treatment: A more personalised and holistic treatment plan that considers the full spectrum of influencing factors can lead to better outcomes for the individual.

Key Takeaway:

Viewing voice production as an assemblage of interconnected forces allows for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of voice disorders, promoting effective and personalised care.

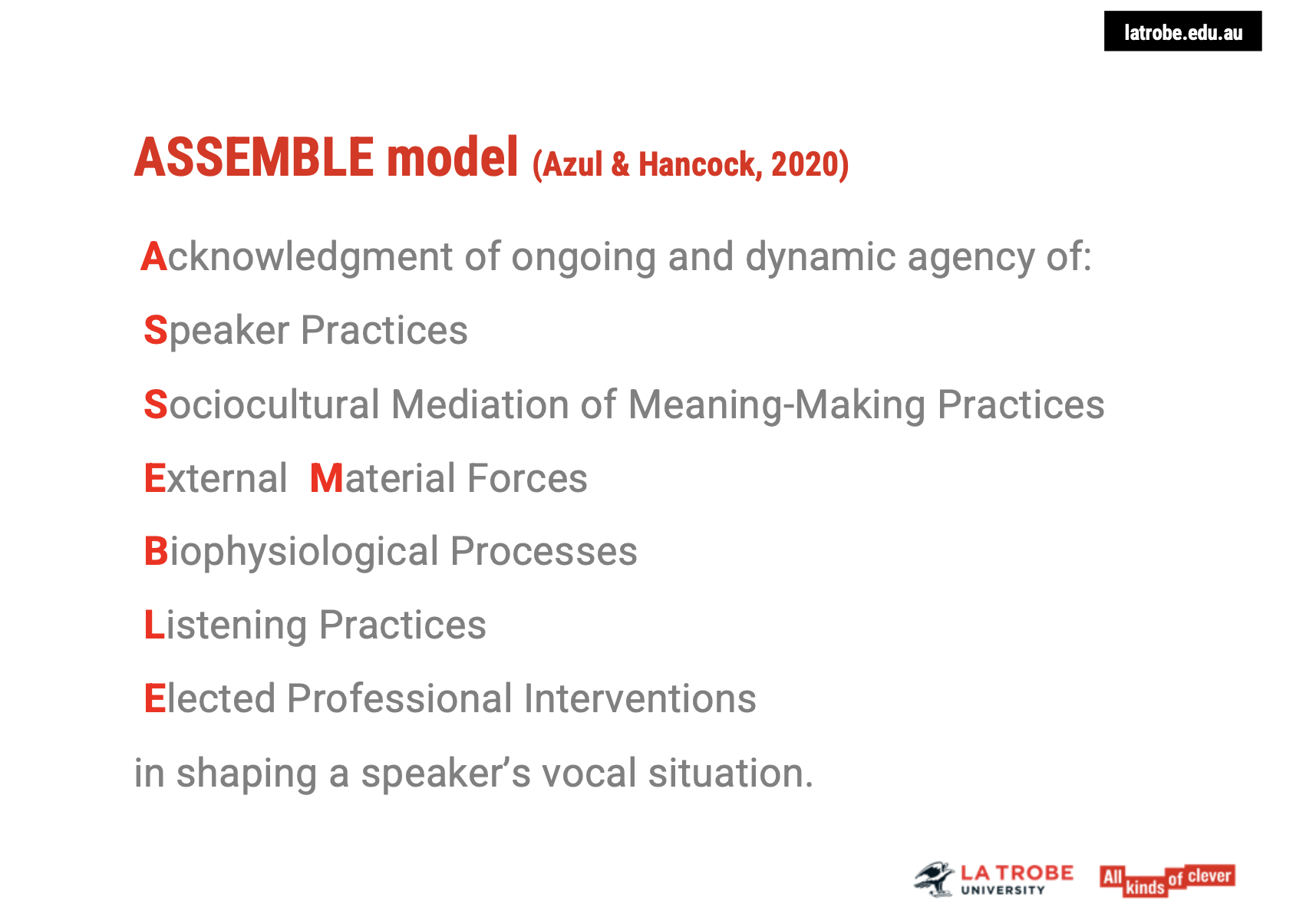

The Assemblage Model: Azul & Hancock (2020)

Overview of the Assemblage Model

Key Concept: The Assemblage Model, as explored by Azul and Hancock (2020), presents an alternative perspective on voice production and disorders.

Interconnected Forces: This model highlights how biophysiological, psychological, and environmentalfactors interact and contribute to voice problems.

Holistic View: It emphasizes that voice issues should not be confined to just one category (e.g., functional, organic, psychogenic) but rather viewed as influenced by multiple dynamic forces.

Key Focus in Azul & Hancock's Article

Interaction of Forces: The article delves into how different forces, such as mental health, social stressors, and physical changes, come together to influence voice production.

Impact on Voice Problems: The model explores how these interacting factors can lead to voice disorders and provides insights into managing and addressing them.

Relevance for Practitioners

Integrated Treatment: By understanding these complex interactions, health professionals can develop more comprehensive and individualized treatment plans.

Broadening Perspectives: The Assemblage Model encourages a shift from traditional, isolated classifications to a more multifaceted understanding of voice disorders.

Takeaway:

Azul and Hancock (2020) offer a significant contribution to understanding voice production and disorders by proposing an interconnected model that moves away from narrow categorizations, aligning more with a holistic, multidimensional view.

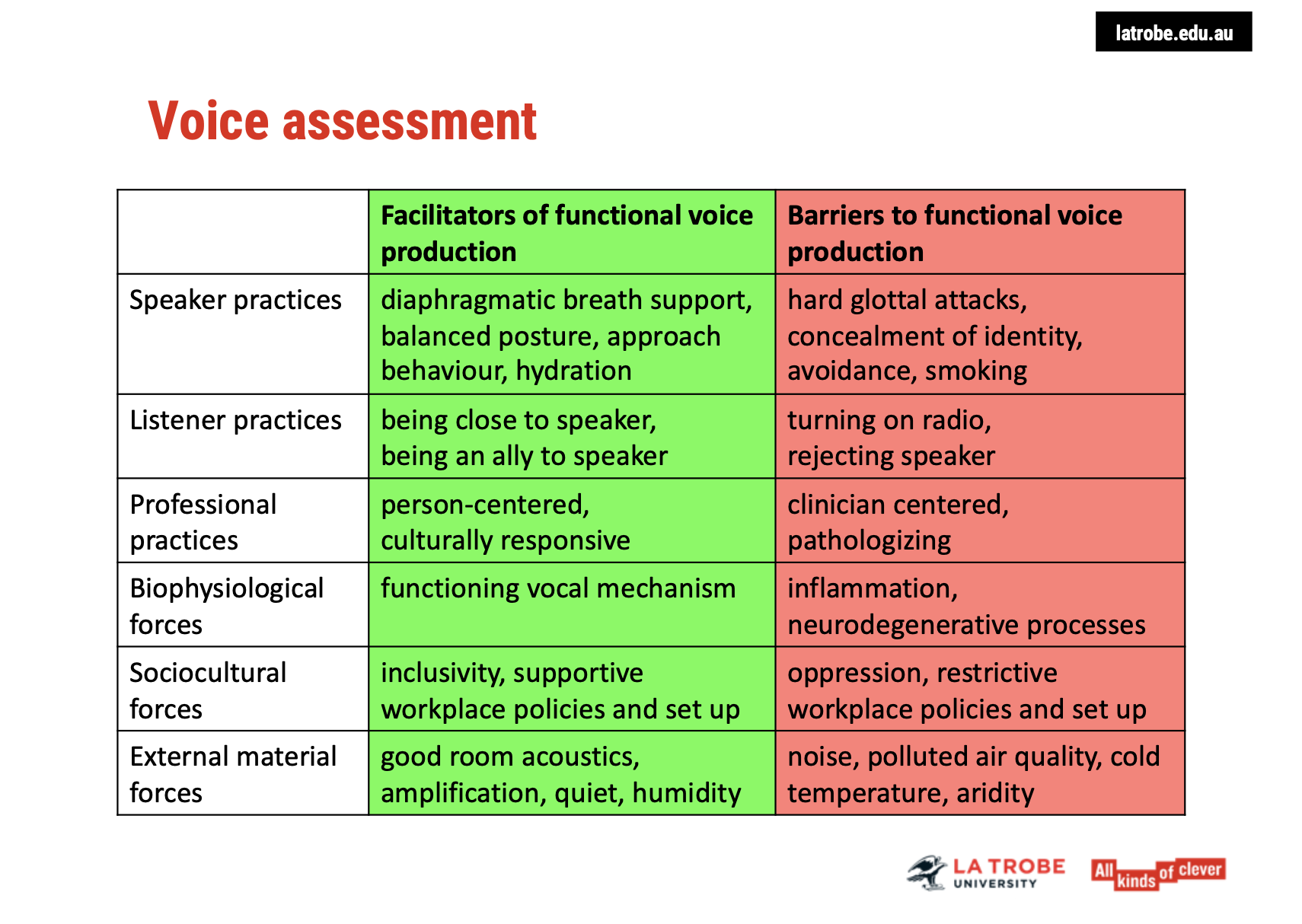

Voice Assessment: Focus on Facilitators and Barriers

Approach to Voice Assessment

Person-Centered Approach: The aim is to identify what supports or hinders functional voice production for the individual, rather than pathologising the client.

Facilitators: Positive aspects that aid the voice, such as diaphragmatic breathing or good posture.

Barriers: Factors that may interfere with voice production, like vocal strain or stress-related behaviours(e.g., hard clotted attacks, smoking, social avoidance, identity concealment).

Collaborating with Clients and Support Systems

Identifying Strengths: Acknowledge what the client is already doing well to support their voice.

Addressing Barriers: Discuss the negative behaviours or factors affecting voice quality, including stress, physical strain, and social influences.

Engaging Others: Involve family or significant others to help the client improve their voice by supporting them emotionally or making practical changes, like reducing background noise during conversations.

Biophysiological Forces: Facilitators & Barriers

Facilitators: A well-functioning vocal mechanism.

Barriers: Inflammation or neurodegenerative processes affecting the voice.

Intervention: Recommend medical consultation if necessary (e.g., for inflammation or chronic conditions).

Sociocultural Forces: Facilitators & Barriers

Facilitators:

Inclusive environments that celebrate diversity.

Workplace policies that provide support for voice health (e.g., amplification, air quality management).

Barriers:

Oppressive societal forces, such as discrimination or lack of support in the workplace for individuals with diverse voices.

External Material Forces: Facilitators & Barriers

Facilitators: Good room acoustics, amplification systems, quiet spaces, and optimal humidity.

Barriers: Poor air quality, noise, polluted environments, or extreme temperatures (cold/arid conditions).

Key Takeaways

A holistic voice assessment should not only identify biological issues but also address social and environmentalfactors.

Supportive environments are essential for functional voice production, and working with other professionals and significant others can enhance outcomes.

Person-centered, culturally responsive approaches are critical to avoid pathologising and to foster a more supportive, inclusive framework for voice health.

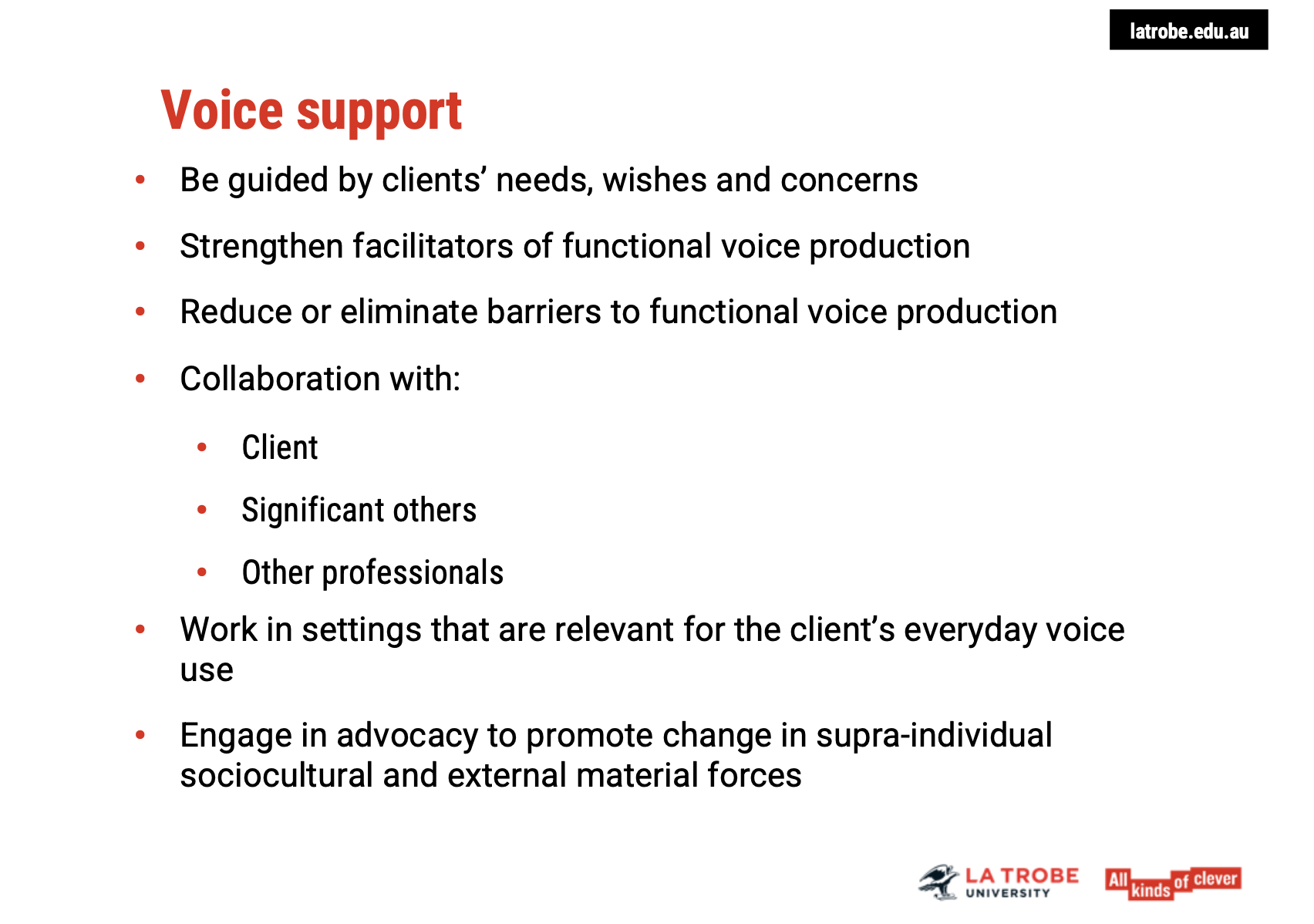

Voice Support: Person-Centered and Culturally Responsive Care

Principles of Effective Voice Support

Client-Centered Care: The voice support plan should be guided by the client's individual needs, wishes, and concerns.

Focus on strengthening facilitators of voice production and reducing/eliminating barriers where possible.

Collaboration with Professionals: Recognising that not all factors influencing voice production are within the scope of a speech pathologist’s work.

For uncontrollable barriers, collaboration with mental health practitioners, ENT specialists, medical doctors, and peer support groups is essential.

Advocacy: Commitment to social change and advocacy projects, which might take time but can have long-term benefits for the client’s voice health.

Influencing Change: What Can and Cannot Be Controlled

Influencable Factors: Identify what aspects of voice production can be positively impacted through therapy or environmental adjustments.

Non-Influencable Factors: Recognise when other professionals or external support structures (e.g., medical treatment or social support) might be needed.

Generalising Voice Support Across Settings

Relevance to Real-World Settings: Voice therapy should be provided in settings that reflect the client's real-life voice use.

Different vocal situations (e.g., home, work, social environments) introduce varying challenges to voice production, so therapy needs to be adaptable.

Long-Term Goal: Ensure the client can effectively use their voice in all areas of life, not just within therapy sessions.

Key Takeaways

Comprehensive Approach: Successful voice support requires a collaborative, holistic approach, integrating the work of different professionals and the client's personal context.

Sustained Impact: The aim is to enable clients to use their voice optimally in a variety of contexts, ensuring their needs are met beyond just the therapy room.

Advocacy and Social Change: Committing to broader advocacy projects can support long-term improvements in voice health and societal support for individuals with voice disorders.